ABSTRACT

This research provides insight into current te reo Māori (the Indigenous language of Aotearoa, New Zealand) use in English-medium ECE settings. We videoed naturalistic conversations between kaiako (educators) and tamariki (aged 15–28 months) at 24 English-medium BestStart ECE centres. Te reo Māori was quantitatively assessed across five routines: kai (food) time, book time, group time, free play, and nappy change. The highest rates of te reo Māori use per minute were observed during the kai time, book time, and group time routines, respectively, and lowest during free play and nappy change. Although scripted/prepared te reo Māori use (e.g. karakia and waiata; prayer and song) were well used, opportunities for more complex and elaborate te reo Māori use remain. This research provides insight into the current use of te reo Māori in English-medium ECE settings, an enhanced understanding of kaiako contributions to te reo Māori revitalisation goals, and applications for practice.

Introduction

History and decline of te reo Māori

The use of te reo Māori (the Māori language), the Indigenous language of Aotearoa New Zealand, has experienced shifts in usage and history throughout its existence. At the beginning of the eighteenth century, te reo Māori was the dominant language in Aotearoa and was considered a taonga (treasure) widely spoken by tangata whenua (people of the land; De Bres Citation2015; Arahanga-Doyle Citation2021; Skerrett and Ritchie Citation2021). The signing of New Zealand’s founding document, Te Tiriti o Waitangi, in 1840 marked the beginning of the British/Crown government in New Zealand, which led to the suppression of the Māori language through various policies and acts (Higgins Citation2005). The Māori version of the Treaty document outlined the expectation of maintaining the Māori language and culture; however, the lack of clarity in the English version of the Treaty allowed for a range of interpretations that disregarded important aspects of Māori identity, including language (Ritchie Citation2008; Reese et al. Citation2018; Skerrett and Ritchie Citation2021). The Treaty's complexities and translational inaccuracies have caused several long-lasting challenges for Māori communities, including the loss of cultural identity, land loss, and subsequent poverty for Māori (Reese et al. Citation2018; Moewaka Barnes and McCreanor Citation2019).

By the 1860s, with the increased European settler population, in combination with the subsequent influence of colonisation and cultural assimilation, there was a considerable decline in the number of people speaking te reo Māori, and English became the dominant language in Aotearoa (Taani Citation2019). This was largely due to the dominant influence of Pākehā, a term used to describe people of European descent in New Zealand. It is important to acknowledge that the term Pākehā is not intended to be derogatory, but rather a taonga given to Pākehā by the Indigenous people of Aotearoa that signifies the relationship with Māori and the whenua (land; Amundsen Citation2018).

Early mission schools that aimed to spread Christianity and European knowledge among Māori initially utilised a bilingual approach, using both te reo Māori and English mediums of instruction (Walker Citation2016). However, over time, English gradually became the primary language of instruction, with English-medium education incentivised through higher funding, leading to the decline of te reo Māori (Seals et al. Citation2020). Facilitating this decline were suppression acts that suppressed both te reo Māori and Māori culture by punishing all those speaking te reo Māori and ensuring tamariki (children) were only taught the English language (Benton Citation1989; Reedy Citation2000; Arahanga-Doyle Citation2021). The intergenerational transmission of the culture, language, and worldviews of Māori was therefore prevented, which saw the Indigenous language and culture principally replaced with British customs, values, and language, assimilating Māori into European ways (Spolsky Citation2003; Walker Citation2016). Moreover, many Māori discouraged their children from learning te reo Māori because they worried about the social repercussions of using te reo Māori, and many also had the perception that the ability to speak English proficiently opened up opportunities for their children to thrive in an environment where Pākehā ways were highly valued (Matthews Citation2018). In 1903, te reo Māori was banned as a medium of instruction within schools in Aotearoa and was actively discouraged by educational authorities (Ka'ai-Mahuta Citation2011). By 1979, te reo Māori was undeniably endangered and at serious risk of extinction, with many believing it would disappear completely (Ka'ai-Mahuta Citation2011; Walker Citation2016; Ka'ai et al. Citation2019; Barrett-Walker et al. Citation2020).

Despite these historical challenges, there is growing acknowledgement of the importance of te reo Māori; current revitalisation efforts aim to incorporate te reo Māori as an additional medium of instruction within English-medium schools to ensure the revival and continuity of the language (Brouwer and Daly Citation2022). However, despite being an official language of New Zealand, there are still various challenges at present that hinder its inclusion in the teaching of the national curriculum in English-medium schools (Ministry of Education Citation2013; Simmonds et al. Citation2020).

Globally, Indigenous languages have been subjected to similar colonial fates (Karidakis and Kelly Citation2018; McIvor and Ball Citation2019; Barrett-Walker et al. Citation2020). Following European invasion, both Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander cultural groups, who make up Australia's Indigenous peoples, experienced significant language loss (Karidakis and Kelly Citation2018). Currently, less than half of their 250 Indigenous languages are still spoken, and many more are now classified as endangered (McConvell and Thieberger Citation2001; Karidakis and Kelly Citation2018). As highlighted, many minority languages have also been on a trajectory toward language extinction for some time (Barrett-Walker et al. Citation2020). Moreover, often highlighted in the Indigenous language literature is the harmful impact of language suppression on the physical, social and emotional well-being, sense of belonging, and identity of Indigenous peoples (Rameka Citation2018; Fatima et al. Citation2022). Therefore, not only is the risk of losing te reo Māori a genuine threat to mātauranga Māori (Māori knowledge) and tikanga Māori (Māori customs) but also the entire mauri (life force) and existence of Māori people (Moon Citation2016). Given that the survival of the Māori language is far from secure, the longevity and well-being of te reo Māori are reliant on the success of language revitalisation efforts and prioritisation of the Māori language to ensure the Indigenous language is not only spoken but transmitted to new generations (Ratima and May Citation2011; Simmonds et al. Citation2020; Skerrett and Ritchie Citation2021).

Kia kaua te reo e rite ki te moa, ka ngaro

Do not let the language suffer the same fate as the moa

(Barrett-Walker et al. Citation2020)

Te reo Māori revitalisation efforts

Language revitalisation refers to the practice of restoring a language’s vitality and reviving a language that is in danger of disappearing (Romaine Citation2007; Reyhner and Lockard Citation2009). Following the movement to revitalise te reo Māori in the 1970s, many initiatives have since been launched, including the establishment of Kōhanga Reo (Māori language immersion ECE), the foundation of independent organisations specifically promoting te reo Māori use, increased funding for te reo Māori education, and the development of government strategies for Māori language revitalisation (Ministry of Education Citation2013; Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori Citation2018; Simmonds et al. Citation2020).

Despite these innovative campaigns, few had specifically targeted the implementation of te reo Māori within English-medium settings in New Zealand until the development of the national early childhood education curriculum framework Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa Early childhood curriculum (Ministry of Education Citation1996). Te Whāriki, first published in 1996 and revised in 2017 and 2019, is internationally recognised for its bicultural approach to early years education and childcare (Ministry of Education Citation1996; Ritchie Citation2002; Smith Citation2005; Lee et al. Citation2013). Specifically, the framework recognises te reo Māori as a taonga and encourages educators to support the learning and use of te reo Māori by young children and promote ngā tikanga Māori (Māori cultural practices; Ritchie Citation2008; Ministry of Education Citation2017; Brouwer and Daly Citation2022). Additionally, the curriculum provides specific examples of how educators may be able to authentically incorporate te reo Māori into their practice, such as using karakia (prayers), waiata (songs), and simple conversation (Ministry of Education Citation2017). Although these examples were detailed, a majority of leaders and educators in early learning services (51%) indicated in 2019 that they were not ready and did not feel able to effectively implement Te Whāriki (Education Review Office; ERO Citation2019). Therefore, there is a need for ongoing efforts to build knowledge, skills, and confidence among educators to effectively incorporate the elements of Te Whāriki into their teaching practices, including aspects related to language (Broadley et al. Citation2015).

Amongst wider New Zealand, there has been recent appreciation for the importance of te reo Māori and an awakened interest in the protection and revitalisation of the Indigenous language (Ka'ai et al. Citation2019; Calude et al. Citation2020; Oh et al. Citation2023). The latest data collected in 2021 from the General Social Survey (GSS) showed that reports of te reo Māori proficiency among New Zealanders (aged 15 years and over) had improved over time; with the proportion of people reporting being able to speak more than a few words or phrases in te reo Māori increasing from 24% to 30%, between 2018 and 2021 (Statistics New Zealand Citation2022). Additionally, the proportion of the total population in New Zealand reporting being able to speak te reo Māori fairly well increased from 6.1% to 7.9% between 2018 and 2021 (Statistics New Zealand Citation2022).

Despite this increase in the number and proficiency of te reo Māori speakers, the growth should be interpreted with caution (Barrett-Walker et al. Citation2020; Skerrett and Ritchie Citation2021). Recent modelling suggests that te reo Māori use may not be sufficient to reach current revitalisation goals and the recent increase may be too small to justify optimism about the overall health of the language (Benton Citation2007; Bauer Citation2008; Ka'ai et al. Citation2019; Barrett-Walker et al. Citation2020). Moreover, these trends are largely based on reported use, not observed use of te reo Māori. Findings from a recent study exploring non-Māori-speakers’ active Māori lexicon showed that while non-Māori-speaking New Zealanders exhibit a greater ability to recognise Māori words, their capability to provide accurate definitions for these words is limited (Oh et al. Citation2023). Specifically, non-Māori-speaking New Zealanders were able to recognise more than 1000 te reo Māori words but only understood the meaning of about 70 (Oh et al. Citation2023). This disparity highlights the need for proactive efforts to not only promote word recognition but also to ensure a comprehensive understanding of te reo Māori. Such efforts are essential for the accurate transmission and acquisition of the language (Smith Citation2012; Skerrett and Ritchie Citation2021). Early childhood education and care settings have therefore been identified as one of the key areas able to actively promote the transmission of Indigenous languages among young children and infants, as they provide opportunities for language exposure and engagement from a young age (Huttenlocher et al. Citation2002; Karidakis and Kelly Citation2018; Wyman and McCarty Citation2019; Skerrett and Ritchie Citation2021). In New Zealand, early learning settings also provide an essential, protected space for regular exposure to and exploration of te reo Māori (Barr and Seals Citation2018).In their toddler years, children are typically in the early stages of language development. Although there are individual differences in language development among children, research indicates that toddlers typically start using their first words around 12–18 months of age (Huttenlocher et al. Citation2002). In the early stages of language acquisition, children typically start using single words that are communicative and gradually progress to using more complex language (Ninio Citation1992). Literacy develops from early oral language proficiency (Suggate et al. Citation2018) and is widely recognised for its important contribution to life-long positive educational outcomes (Derby et al. Citation2022; Derby Citation2023). Furthermore, it is well established that successful language acquisition during early childhood is dependent on access to rich and abundant linguistic interactions and high-frequency language input from adults, such as interactions that typically occur within early learning services (Lust Citation2006). Adults not only provide language input as a conversational partner, but also offer constructive feedback, and role model effective speech and communication for children (Snow Citation1977; Hoff Citation2006). This approach to children’s language development has its theoretical basis in the bioecological model of development which highlights the role of the contexts in which children develop, including early childhood education settings (Bronfenbrenner Citation1979; Huttenlocher et al. Citation2002; Hoff Citation2006). According to recent data from the Ministry of Education’s annual ECE Census in 2022, a total of 181,045 children (aged 0–4 years) were enrolled in licensed early learning services, with 4% of those children attending Kōhanga Reo (Māori language preschools; Ministry of Education Citation2022). Additionally, a study of over 6,000 New Zealand toddlers highlighted that the acquisition of te reo Māori primarily occurred within the context of English being their dominant language (Reese et al. Citation2018). Moreover, data from the 2022 Ministry of Education’s report on Māori participation in early learning highlighted that the majority of Māori children attending early learning services are enrolled in English-medium education. Thus, although schools in Aotearoa were historically responsible for preventing the use and learning of te reo Māori, English-medium education settings now play an important role in the revitalisation of the Māori language (Simmonds et al. Citation2020).

Unlike first language acquisition, acquiring a second language during early childhood in the context of a pre-existing dominant language requires more active support and meaningful engagement from educators (Bracefield Citation2018). Beginning in 2009, the longitudinal Growing Up in New Zealand (GUinNZ) cohort study aimed to understand the development of over 6000 children from before birth to adulthood including the use of te reo Māori among children (Simmonds et al. Citation2020). According to findings from the GUinNZ study, parent–child interactions including reading books, telling stories, singing waiata, and engaging in structured counting routines were all significant predictors of te reo Māori acquisition among children (Simmonds et al. Citation2020). This data may be unsurprising given the large body of research showing that shared book reading is one of the best ways to foster children’s language development (Bleses et al. Citation2020; Dowdall et al. Citation2020). Moreover, storytelling, singing songs, and reciting chants have been found to specifically foster bilingual Māori preschool children’s early literacy development (Derby Citation2023). Mothers of the children in the GUiNZ study also reported on their children’s te reo Māori proficiency at age 2 using a translated version of the MacArthur-Bates Communicative Development Inventory (CDI): Short form (based on Fenson et al. Citation2000; adapted for New Zealand by Reese et al. Citation2018), as well as a further assessment of Māori words and phrases at age 4.5 years (Simmonds et al. Citation2020). At 2 years of age, 763 of 6327 children (12%) from the cohort were reported by their mother to understand te reo Māori, and at age 4.5 years, 4634 of 6052 children (77%) from the cohort were reported by their mother to know at least some te reo Māori (Simmonds et al. Citation2020). This suggests that a large number of both Māori and non-Māori children in Aotearoa have some understanding of te reo Māori by the age of 4.5 years (Simmonds et al. Citation2020). However, these previous assessments relied on parental reports, and few studies had collected observational data on te reo Māori use in ECE settings.

Established in 2016, the Wellington Translanguaging Project in New Zealand has undeniably contributed to a better understanding of the communication of multilingual children (Seals Citation2021). The first of its kind, the project’s ground-breaking research involved the collection and analysis of over 600 hours of observational data from two multilingual preschools (one Samoan early childhood centre and one Māori early childhood centre) in the Wellington area (Seals Citation2021). It was found that translanguaging, the practice of using multiple languages interchangeably within a conversation, was a normal occurrence for both educators and students within the centres (Seals Citation2021). The findings of the study were also used to produce translingual teaching resources to help educators build children’s vocabulary across languages as part of an initiative called Translanguaging Aotearoa (Seals et al. Citation2020).

There is still limited research at present which has quantified the current use and implementation of te reo Māori within English-medium early childhood education and care (ECE) centres in Aotearoa New Zealand. We expand on the innovative work of Seals and colleagues in the current study by collecting observational data from several English-medium-only BestStart education centres across Aotearoa. To our knowledge, only two previous studies from the 1990s have utilised naturalistic observations to gain an understanding of te reo Māori use in English-medium ECE settings. Ritchie (Citation1999), as cited in Ritchie (Citation2008) observed 13 ECEs in the Waikato area for visible signs of biculturalism, including te reo Māori use. It was found that te reo Māori use was limited to simple commands, counting, and naming colours and that educators tended to use single Māori words nested within English sentences (Ritchie Citation1999, as cited in Ritchie et al. Citation2008). In a similar vein, Cubey (Citation1992) conducted observations of eight ECE centres in the Wellington area and observed minimal te reo Māori use during the observation period (Ritchie Citation1999, as cited in Ritchie et al. Citation2008). Following on from these studies, questions about the current observed usage of te reo Māori within English-medium ECEs across Aotearoa remain.

The current research aims to fill this research gap by providing an enhanced understanding of the current frequency and function of te reo Māori use across multiple English-medium ECEC centres in Aotearoa. We examine how kaiako (educators) can contribute to the revitalisation of te reo Māori in their early childhood education settings and discuss the potential impact on educational success for both Māori and non-Māori learners. Naturalistic conversations between kaiako and tamariki were video recorded across 24 ECE centres in Auckland, Christchurch, and some rural regions of the South Island. All ECE centres were part of the BestStart provider of early childhood education and care. The video footage was transcribed verbatim, and each verbal utterance of te reo Māori was then coded to analyse current use. We aimed to provide an exploratory assessment of the current use of te reo Māori in English-medium ECE, so we did not have specific hypotheses.Method

Participants

A total of 138 English-medium BestStart early childhood education centres across New Zealand are participating in a nationwide randomised control trial (RCT) Kia Tīmata Pai (KTP; The Best Start), which comprises 1481 children aged 13–30 months at the outset, their whānau (family), and their early childhood educators (Reese et al. Citation2023a). Recruitment of participants was carried out with the support of BestStart centres, which promoted the study to parents. From these, a subset of 24 BestStart centres (12 in Auckland; 8 in Christchurch; and 4 in Southland) were selected to participate in the KTP Video Project sub-study, with centres in those regions randomly selected from each of the four conditions in the larger trial. At baseline (pre-intervention), a total of 94 children aged 15–28 months and 64 kaiako across the centres were taking part in the Video Project. The ethnicity of the child participants according to parent reports, using the total response method, included New Zealand European (61.7%), Asian (31.9%), New Zealand Māori (19.1%), Pacific Peoples (9.6%), and Middle Eastern, Latin American and African (MELAA; 1.1%); the ethnicity of the participating kaiako, also using the total response method, comprised New Zealand European (60.42%), Asian (39.58%), New Zealand Māori (8.33%), and Pacific Peoples (4.17%). Overall, 74.1% of educators had a university degree or higher qualification, while the remaining 25.9% had qualifications ranging from School Certificate 5th form/NCEA Level 1 to a Polytechnic qualification. Of the 64 participating kaiako, 22 provided self-reported proficiency scores using te reo Māori using a sliding bar scale which ranged from beginner (0) to intermediate (50) and advanced (100). The mean proficiency score of the kaiako was 18.5, with individual scores ranging from 0 to 50, suggesting advanced beginner levels on average.

Procedure

Ethical approval for the KTP Video Project was obtained by the University of Otago Health Ethics Committee (reference: H20/116). Māori consultation occurred at two levels: consultation with the Ngāi Tahu Research Consultation Committee and also an internal body of the study called the Cultural Advisory Group comprised of academics, Māori researchers, community members, and members from the BestStart organisation (Reese et al. Citation2023a). As noted by Smith et al. (Citation2012), we recognise the importance of prioritising positive change for Māori communities and acknowledge the Māori perspectives that have guided the research design, informed on the appropriateness of self-report assessments and intervention materials, data analysis methods, and interpretation of findings across all aspects of this rangahau (research). All participating teachers provided informed consent, and parents consented on behalf of their children. Before the observations took place, parents of non-study children were sent a letter seeking their consent for their child to be included in the video frame during filming, with the understanding that their child’s inclusion in the video footage would not be analysed. Consent determined the inclusion of non-study children in video data collection, with no video data being collected if consent was not obtained. Prior to the observation period, participating centres received a verbal reminder.

To help identify study participants at the time of filming, stickers or high-visibility vests were provided for children and teachers to wear. Teachers were also requested to maintain their regular teaching activities during the observational filming period. In each early childhood centre, naturalistic language interactions were captured by a trained researcher using a small, hand-held video camera across five routines (Kai Time [food time], Book Time, Group Time, Free Play Time, and Nappy Change). Overall, the researcher aimed to film an average of 5 min per routine, for a total of 25 min at each centre, across the routines. Of note, in some instances, filming of some routines was not possible, such as when no children needed their nappy changed, or in the case when no books were read during the observation period. Researchers stayed a maximum of 90 min at each centre. Therefore, video data for each of the five routines was not collected for every centre. Overall, the total filming length of videos varied across the routines, with videos during Kai Time ranging in length between 01:34 and 12:12; Book Time videos between 2:46 and 07:53; Group Time videos between 1:09 and 15:14, Free Play videos between 0:54 and 6:34, and Nappy Change videos between 02:00 and 03:00, in minutes and seconds. To account for these differences in total time filmed in each routine, analyses focused on the rate of te reo Māori use per minute and total talk in te reo Māori.

As a general rule, the filming of Kai Time began when food was being prepared and children were sitting down at the table in preparation to eat. In addition, the filming of Book Time commenced when either a teacher or child began reading a book or started narrating alongside an audiobook. Group Time was defined as a teacher-directed opportunity, where the teacher had the intention of engaging at least two children in a conversation or activity (e.g. a structured mat-time with the teacher using blocks to demonstrate counting to a group of listening children). In contrast, Free Play Time was defined as any child-directed play. Nappy Change was filmed when teachers needed to change a child’s nappy. The teacher was asked for verbal consent once again before filming any nappy changes. For obvious privacy reasons, Nappy Change filming never included the child in the video frame and only featured the teacher’s face. All teachers were reminded of their ability to withdraw consent from the Video Project study at any time without any consequences for them, their children, or their centre. Teachers were also given the option to change their consent to audio-recording only during the nappy changes and were provided an opportunity to review the Nappy Change video footage, to double-check that the child was out of frame.

Data analysis

All video recordings were transcribed verbatim by the same researchers who did the filming and were double-checked. Transcripts containing te reo Māori were identified (45 transcripts out of 86), and two Māori researchers who had a basic understanding of te reo Māori (defined as being able to recognise, understand, and spell it correctly) completed an additional check of the language using the Te Aka Māori Dictionary (Moorfield Citation2005). All transcripts were then organised and analysed using qualitative analysis software (NVivo 12 Plus) and quantitative analysis software (SPSS Statistics 27). Nvivo 12 Plus was also used to create the te reo Māori word frequency list and word frequency clouds. Each utterance (any verbalisation of te reo Māori) was identified and coded according to five main codes: including routine type (e.g. Kai Time, Book Time), quantity of words (e.g. one-, two-, and three-or-more words in te reo Māori), function of speech (e.g. conversation, karakia, waiata), type of speech (e.g. scripted or unscripted), and initiating speaker (e.g. teacher or child) (See Appendix A). The intercoder reliability was calculated by comparing the same 25% of transcripts (12 transcripts) independently coded by a second researcher. A Cohen’s kappa value of 0.80 was observed, indicating very good agreement (Landis and Koch Citation1977; Hallgren Citation2012). Following this, the two researchers then coded a randomly allocated 50% of each of the remaining transcripts, and double data entry was then completed. Qualitative output data from NVivo representing the number of coding references for each utterance of te reo Māori was imported into SPSS Statistics to generate descriptive statistics.

Results

As shown in , the use of te reo Māori occurred most frequently during Kai Time, with 95.65% of centres using te reo Māori at least once during this routine. In contrast, te reo Māori was used least often during Nappy Change, with just 18.75% of centres using te reo Māori throughout this routine. Moreover, the percentage of centres using te reo Māori varied during the Free Play (45.45%), Book Time (40.00%), and Group Time (37.50%) routines. Fewer than half of the centres held a book reading session during the observation period.

Table 1. Percentage of ECE centres that used any te reo Māori, categorised by routine.

To account for differences in total time filmed in each routine, further analyses focused on the rate of te reo Māori use per minute as well as total talk in te reo Māori. As depicted in , the mean number of utterances in te reo Māori during the observation period was the highest during the Group and Book Time routines (7.30 and 6.25 utterances, respectively). The most frequently used te reo Māori words during Group Time were ‘Pakipaki’ (clap) and ‘Well done, tamariki mā (children)’, and ‘E noho (sit)’ during Book Time. A more comprehensive word frequency list of the 20 most frequently used te reo Māori words is presented in Appendix B. The total number of utterances in te reo Māori was lower during Kai Time (with an average of 4.77 utterances) and was even lower during Nappy Change and Free Play (with an average of 2.00 and 1.67 utterances per routine, respectively).

Table 2. Mean number of utterances (per Routine, and per Minute) including te reo Māori, in centres using te reo Māori.

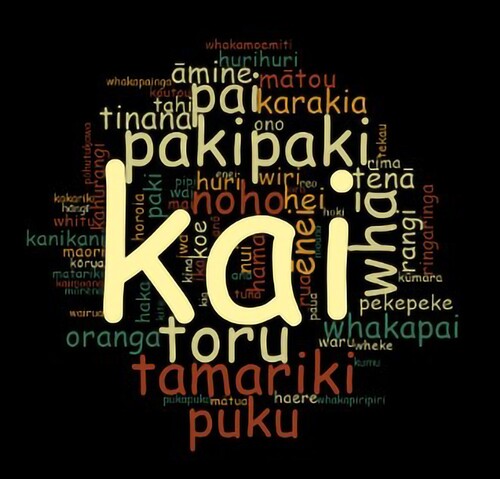

The highest rates of te reo Māori use per minute were observed during the Kai Time, Book Time, and Group Time routines (4.56, 1.16, and 1.35 words per minute, respectively). The lowest rates of te reo Māori use per minute were observed during the Free Play and Nappy Change routines (0.39 and 0.78 words per minute, respectively). The most frequently used words during Kai Time were ‘Make sure you blow on your kai’, and ‘Shall we do karakia now?’, which are words highlighted in the word frequency cloud shown in (Word frequency cloud as a visual representation of te reo Māori words used). During Nappy Change, the most frequently used word was ‘Ready for kai?’ and during Free Play, it was ‘Ka pai! (good!)’.

Figure 1. Word frequency cloud as a visual representation of te reo Māori words used.

Note. This figure illustrates a word frequency cloud as a visual representation of te reo Māori words used, with words arranged by size depending on their frequency. The more frequently a word in te reo Māori was used within the ECE centres, the larger and more prominently it appears in the word cloud.

demonstrates that single-word utterances in te reo Māori were consistently used more frequently than both two-word and three or more-word utterances in te reo Māori across all five routine types. Overall, single-word utterances in te reo Māori such as ‘You want to sing a karakia?’, ‘Ooh they’re having a hāngi (food cooked in an earth oven)’ and ‘We could have another pukapuka (book)’ were highest during Group Time (3.50) and Book Time (3.25), followed by Kai Time, Nappy Change, and Free Play (2.81, 1.67, and 1.17, respectively). Two-word utterances in te reo Māori such as ‘It’s mat-time, hello, kia ora’ (hello), ‘Toru, whā’ (counting: three, four) and ‘Well done tamariki mā’ were most common during Group Time (2.00) and Book Time (2.00), compared to during Kai Time, Free Play, and Nappy Change routines (0.91, 0.50, and 0.33, respectively). In the word count, it should be noted that utterances such as ‘E tū’ (to stand) and ‘E noho’ were categorised as containing two reo Māori words because the particle ‘e’ is considered a distinct grammatical marker in Māori language; therefore, the utterances were deemed more complex than singular words. Three or more-word utterances in te reo Māori such as ‘Ka pai tamariki mā!’ (good children!) and ‘Horoia ō ringaringa, horoia ō ringaringa, horoia ō ringaringa, tamariki mā!’ (wash your hands, wash your hands, wash your hands, children) were used most frequently during Group Time (1.80), followed by Kai Time (1.05), and Book Time (1.00). Three or more-word utterances in te reo Māori did not occur during the Free Play or Nappy Change routines.

Table 3. Mean number of utterances including te reo Māori words and phrases across routines.

As shown in , utterances in te reo Māori were categorised according to speech function, or the reason for the speech, and are displayed in . During Kai Time, utterances in te reo Māori were predominantly categorised as Conversation (3.7), followed by Waiata (0.4), Greetings/farewells (0.4), Counting (0.4), and Karakia (0.3). Book reading utterances in te reo Māori occurred during the Book Time routine only (2.8), alongside Conversational utterances (2.8), and some Counting (0.8). During the Group Time routine, most utterances in te reo Māori were Conversational (4.0), with some Waiata (1.6), Counting (1.2), Karakia (0.3), and Greetings/ farewells (0.2). Utterances in te reo Māori during the Free Play and Nappy Change routines were solely Conversational (1.67 and 2.00, respectively).

Table 4. Mean number of utterances that include te reo Māori in each function category across routines.

As shown in , the majority of utterances in te reo Māori were Unscripted, spontaneous verbalisations rather than Scripted, prepared te reo Māori use that had been rehearsed or planned. More specifically, during Kai Time the mean number of utterances in te reo Māori were more likely to be Unscripted (3.68) compared to Scripted (1.09). Similarly, utterances in te reo Māori which occurred during Group Time were also more likely to be Unscripted (4.60) rather than Scripted (2.70). Utterances in te reo Māori were solely Unscripted during both the Free Play and Nappy Change routines (1.67 and 2.00, respectively).

Table 5. Mean number of utterances that include te reo Māori by type (scripted or unscripted).

As shown in , all utterances in te reo Māori were consistently initiated by the ECE educators and were never initiated by children. Educator-initiated utterances in te reo Māori were the highest during Group Time (6.60) and Book Time (6.25), followed by Kai Time (4.77). Utterances in te reo Māori that were initiated by educators were less frequent during the Nappy Change (2.00) and Free Play (1.67) routines.

Table 6. Mean number of utterances that include te reo Māori initiated by each type of speaker.

Discussion

Overall, educators were consistently using te reo Māori in their practice, in line with Te Whāriki. Much of this use was high-frequency te reo Māori words and phrases commonly used in New Zealand society (Ministry of Education Citation2010; Reese et al. Citation2018). Although every centre visited used at least some te reo Māori during the observation period, some centres used very little, whereasother centres used a great deal. Te reo Māori use also varied across routines.Kai Time was the most common routine that incorporated te reo Māori, and had the highest rate per minute, whereas Nappy Change had the lowest te reo Māori use. When Group Time and Book Time occurred during the observational period, however, these routines also afforded relatively high rates of te reo Māori use, with over one utterance per minute. In contrast, Free Play Time returned the lowest rate of te reo Māori use per minute. The findings also showed that across routines, single-word utterances in te reo Māori were more common than two-word and three or more-word utterances, and that te reo Māori use was predominantly conversational, with unscripted and spontaneous utterances in te reo Māori being more common than scripted and rehearsed te reo Māori use. In combination, these findings provide an enhanced understanding of the patterns of te reo Māori use within English-medium ECE settings.

Educators consistently initiated all utterances of te reo Māori, and educator-led te reo Māori always preceded children’s te reo Māori use, as shown in . Additionally, te reo Māori was invariably used most often during conversational interactions between children and their educators. This pattern emphasises the importance of educators and the role they have in implementing te reo Māori into English-medium ECE settings, and how they are providing children an opportunity to respond to and return te reo Māori use. It is important to recognise that this is an immense responsibility for educators; without adequate support, it may be unrealistic for some kaiako to suitably implement te reo Māori across the day. Indeed, educators may benefit from additional support and supplementary teaching before they can more fully incorporate te reo Māori into their English-medium ECE settings.

Given that the educators’ mean self-reported proficiency using te reo Māori was so varied, ranging from beginner through to intermediate, it is possible that some of the variation in te reo Māori use within the centres was due to differences in the linguistic proficiency of the educators. Indeed, future studies should specifically account for educator language skills. Despite this variation in educators’ confidence and skill, te reo Māori was used by nearly every ECE centre observed during Kai Time, which suggests that educators may feel most able to incorporate te reo Māori into their practice when they have structured implementation strategies such as those outlined in Te Whariki (e.g. using karakia and waiata when children are at mealtimes or in preparation to eat). The most common utterances in te reo Māori during Kai Time were phrases related to food and drink, such as ‘Let's get our wai, our water’ and ‘Make sure you blow on your kai’. Taken together, providing kaiako with structured implementation strategies would be most beneficial for supporting the effective incorporation of te reo Māori into their teaching and interactions with tamariki.

Fewer than half of the centres held a book reading session during the observation period. Despite this limitation, when educators did read a book during the observation period, the rate of te reo Māori was relatively high. This increased use may be because of the interactive nature of reading, where educators successfully used books to scaffold te reo Māori use and language comprehension by asking questions and repeating written words and phrases. Shared book reading is beneficial for children’s language development (Bleses et al. Citation2020; Dowdall et al. Citation2020). This finding suggests that a scheduled and structured book reading time could be utilised more frequently to foster te reo Māori use within ECE settings. Although book reading was less common during the 90-minute observation period than the other routines, it is an important routine for young children of all ages and in diverse language environments.

Overall, the intentional, teacher-led Group Time routine supported the use of te reo Māori. This finding is consistent with those of Bleses et al. (Citation2020) in a Danish setting showing that a low-cost teacher-implemented intervention was one of the most beneficial for children’s oral language development. Combined, these findings suggest that conscious and intentional language interactions initiated by educators are key opportunities for te reo Māori use, and language development more generally. The lowest rate of te reo Māori use per minute was observed during the Free Play routine, which is an unsurprising outcome given that Free Play is a child-led setting and teachers always initiated te reo Māori use. Educators often do not like to interfere with child-led play, which means it may be best to concentrate on the other routines that are likely to afford more opportunities for te reo Māori use.

Unlike other ECE routines, Nappy Change provides educators with a unique opportunity to engage in face-to-face interactions with one child only. Given that te reo Māori use was most limited during the Nappy Change routine (although not in terms of words per minute), this finding highlights the unique opportunity for meaningful one-on-one interaction between an educator and child that is currently being missed. Providing educators with more structured and organised support throughout other ECE settings, such as te reo Māori conversation facilitators during educator-led group times and nappy changes with individual children, may increase te reo Māori use during these settings where current use is limited.

Positively, across all five routines, the use of te reo Māori was more likely to be spontaneous and unscripted, compared to learned and rehearsed utterances. However, this finding should be considered in relation to the quantity of words; single reo Māori words were used more frequently in comparison to two reo Māori words and three or more reo Māori words. For instance, during Kai Time, ‘There we go, yummy kai’ was a common, spontaneous, conversational utterance, which highlights thatte reo Māori use was often restricted to singular words in te reo Māori in the context of an English sentence. However, this should not be cause for concern, as New Zealand linguists have highlighted that learners of te reo Māori are more likely to memorise and insert te reo Māori words into English sentences (Macalister Citation2008; Citation2009). These loan words from te reo Māori have been successfully integrated into the English language (Calude et al. Citation2020). Indeed, embracing and using even singular te reo Māori words holds value, and without doubt, contributes to revitalisation efforts and promotes translanguaging within educational spaces (Seals et al. Citation2020). Moreover, further support may still be needed to encourage educators to move from this important first step of learning to using more complex and elaborate language structures.

Our findings are therefore consistent with Ritchie’s (Citation2008) findings 15 years ago in that te reo Māori use within 13 Waikato ECE centres was largely restricted to the insertion of singular Māori words into complete English sentences. Our findings are also consistent with Simmonds et al. (Citation2020), who reported that greetings/ farewells and simple words were the most commonly used utterances in te reo Māori among the full GUiNZ cohort (6052 children) at age 4.5 years. These simple words are a positive first step, as they provide a foundation for more complex language use. Second language acquisition involves the gradual progression from basic vocabulary and simple sentence structures toward more complex language use (Ratima and May Citation2011). Therefore, the opportunity for more elaborate te reo Māori use in ECE settings remains, and language efforts should focus on how to shift speakers from simple phrases to the next level of language proficiency. As Ritchie noted in 2008, educators may require additional support to integrate more complex use of te reo Māori into ECE settings. The current study also supports this finding, and highlights the need for ongoing professional development in te reo Māori for educators in ECE (Smith Citation2005). Offering educators additional support will not only facilitate the integration of te reo Māori but will likely enhance their comprehension and understanding of the language, as emphasised by Oh et al. (Citation2023).

We acknowledge that the data presented from the current study reflect only the interactions that occurred during one 30-minute observation period. Unlike the Wellington Translanguaging Project, where over 600 hours of observational data were collected within two ECE centres, the timeframe of the current study may not have fully captured the complete te reo Māori use within the centres. Although our observational period did allow for valuable insights about the current te reo Māori use as a function of routines within the ECE setting (Kai Time, Book Time, Group Time, Free Play Time, Nappy Change), future studies could conduct longer observation durations to gain a more comprehensive and representative understanding of te reo Māori interactions between kaiako and tamariki. Another limitation concerns the recruitment of centres in the Video Project sub-study, which lacked complete randomisation, as the randomly selected sample included centres from three main regions only: Auckland, Christchurch, and Otago/Southland. To strengthen the ability to make generalisations about the findings of the current study, future research should address this limitation by using a more randomised recruitment process to ensure centres are included from diverse regions.

In future research with this specific sample, kaiako will be introduced to an innovative oral language intervention which aims to enhance rich interactions between educators and children to improve their oral language (Reese et al. Citation2023a). The oral language intervention also aims to specifically target and increase the use of te reo Māori and bilingual books within classrooms. The intervention has been informed by a wide range of evidence-based literature that highlights the benefits of using pukapuka pikitia (picture books) to support children’s oral language learning and literacy (Bland Citation2013; Dowdall et al. Citation2020; Brouwer and Daly Citation2022; Derby et al. Citation2022; Riordan et al. Citation2022; Derby Citation2023; Schaughency et al. Citation2023; Reese et al. Citation2023b). Moreover, bilingual children’s books have been recognised as an important facilitator in language revitalisation efforts (Hadaway and Young Citation2013). Therefore, as part of the intervention techniques, participating kaiako will receive new bilingual books written in both te reo Māori and English, alongside instructional videos to assist with pronunciation (Reese et al. Citation2023a).

Conclusion

Within the last decade, there has been growing appreciation for the importance of te reo Māori in Aotearoa New Zealand and increasing interest in the protection and revitalisation of the Indigenous Māori language. Although ECE settings have been recognised as integral for te reo Māori transmission, there has been limited knowledge about the implementation of te reo Māori within English-medium ECE centres. Our research contributes to a greater understanding of the current use of te reo Māori in English-medium ECE centres throughout Aotearoa and recognises the vital contribution of educators toward the revitalisation of te reo Māori. Educators consistently used te reo Māori in their practice, often using some of the most heard and commonly used te reo Māori words and phrases in New Zealand society, which highlights that normalising common utterances in te reo Māori will undoubtedly increase its overall use. There were relatively high rates of te reo Māori used during Kai Time, Group Time, and Book Time in comparison to during Free Play and Nappy Change, which highlights the variation in te reo Māori use across different ECE routines and provides insight into areas in ECE classrooms where more integration of te reo Māori could be possible. Although some centres integrated te reo Māori frequently in their daily interactions with tamariki, centres that used te reo Māori infrequently may benefit most from increased support.

Educators play a critical role in preserving and promoting the Indigenous language, and their knowledge and skills are invaluable in ensuring te reo Māori remains alive. For this reason, it is important to recognise that educators themselves need to be nurtured and supported in their language revitalisation efforts. For some educators, accessing resources, training, structured support and ongoing professional development opportunities may enable them to develop their language skills and better incorporate te reo Māori into their early learning settings.Supplementary materials baseline

Download MS Word (25.4 KB)Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the Wright Family Foundation and Methodist Mission Southern for their generous support and investment in this project, which will undoubtedly make a positive impact on the lives of young learners across Aotearoa. Professor Richie Poulton from the University of Otago secured the funding for this project; Jimmy McLauchlan and Julia Errington-Scott at Methodist Mission Southern led the implementation; and Tugce Bakir-Demir, Isabelle Swearingen, and Yuxin Zhang from the Video Project organised and collected the observations. We would also like to extend a special appreciation to BestStart Education Leaders Clair Edgeler and Natasha Maruariki, to Cultural Advisory Group members Barbara Backshall, Pip Laufiso, and Waveney Lord, and Science Advisory members Dr Libby Schaughency, A/Prof Mele Taumoepeau, Professor Karen Salmon, Professor Dorthe Bleses, and Emeritus Professor David Dickinson for their invaluable input and support. We also express our heartfelt thanks to all BestStart children, whānau, and kaiako participating in Kia Tīmata Pai.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Amundsen DL. 2018. Decolonisation through reconciliation: the role of Pākehā identity. MAI Journal. 7(2):140–146. doi:10.20507/MAIJournal.2018.7.2.3.

- Arahanga-Doyle HG. 2021. Blending whanaungatanga and belonging: a wise intervention integrating Māori values and contemporary social psychology [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Otago.

- Barr S, Seals CA. 2018. He reo for our future: te reo Māori and teacher identities, attitudes, and micro-policies in mainstream New Zealand schools. Journal of Language, Identity & Education. 17(6):434–447. doi:10.1080/15348458.2018.1505517.

- Barrett-Walker T, Plank MJ, Ka'ai-Mahuta R, Hikuroa D, James A. 2020. Kia kaua te reo e rite ki te moa, ka ngaro: do not let the language suffer the same fate as the moa. Journal of the Royal Society Interface. 17(162):20190526. doi:10.1098/rsif.2019.0526.

- Bauer W. 2008. Is the health of te reo Māori improving? Te Reo. 51:33–73.

- Benton N. 1989. Education, language decline and language revitalisation: the case of Māori in New Zealand. Language and Education. 3(2):65–82. doi:10.1080/09500788909541252.

- Benton RA. 2007. Mauri or mirage? The status of the Māori language in Aotearoa New Zealand in the third millennium. In: Tsui ABM, Tollefson JW, editors. Language policy, culture, and identity in Asian contexts. Mahwah (NJ): Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers; p. 163–181. doi:10.4324/9781315092034-9.

- Bland J. 2013. Introduction. In: Bland J, Lutge C, editors. Introduction to children's literature in second language education. London: Bloomsbury; p. 1–12.

- Bleses D, Jensen P, Slot P, Justice L. 2020. Low-cost teacher-implemented intervention improves toddlers’ language and math skills. Early Childhood Research Quarterly. 53:64–76. doi:10.1016/j.ecresq.2020.03.001.

- Bracefield G. 2018. Bilingual children’s acquisition of English and the influence of the home environment. TESOL Journal. 9(1):5–16.

- Broadley ME, Jenkin C, Burgess J. 2015. Mahia ngā mahi: action for bicultural curriculum implementation. Early Education. 58:6–11.

- Bronfenbrenner U. 1979. The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Harvard University Press. doi:10.1126/science.207.4431.634.

- Brougham AE, Reed AW, Kāretu TS. 2012. The Raupō book of Māori proverbs. Auckland: Raupo.

- Brouwer J, Daly N. 2022. Te puna pukapuka pikitia: picturebooks as a medium for supporting development of te reo rangatira with kindergarten whānau. Early Childhood Folio. 26(1):10–15. doi:10.18296/ecf.1103.

- Calude AS, Miller S, Pagel M. 2020. Modelling loanword success–a sociolinguistic quantitative study of Māori loanwords in New Zealand English. Corpus Linguistics and Linguistic Theory. 16(1):29–66. doi:10.1515/cllt-2017-0010.

- Cubey P. 1992. Responses to the Treaty of Waitangi in early childhood care and education [Unpublished M.Ed. thesis]. Wellington: Victoria University of Wellington.

- De Bres J. 2015. The hierarchy of minority languages in New Zealand. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 36(7):677–693. doi:10.1080/01434632.2015.1009465.

- Derby M. 2023. Talking together: the effects of traditional Māori pedagogy on children’s early literacy development. Education Sciences. 13(2):207. doi:10.3390/educsci13020207.

- Derby M, Macfarlane A, Gillon G. 2022. Early literacy and child wellbeing: exploring the efficacy of a home-based literacy intervention on children’s foundational literacy skills. Journal of Early Childhood Literacy. 22(2):254–278. doi:10.1177/1468798420955222.

- Dowdall N, Melendez-Torres GJ, Murray L, Gardner F, Hartford L, Cooper PJ. 2020. Shared picture book reading interventions for child language development: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Child Development. 91(2):e383–e399. doi:10.1111/cdev.13225.

- Education Review Office. 2019. Education Review Office (ERO) report: preparedness to implement Te Whāriki (2017) June 2019. https://ero.govt.nz/sites/default/files/media-documents/2021-04/M19-17-signed-by-minister-ERO-e-Whariki-2017-June-2019-4.PDF.

- Elder H. 2020. Aroha: Māori wisdom for a contented life lived in harmony with our planet. Auckland: Random House.

- Fatima Y, Cleary A, King S, Solomon S, McDaid L, Hasan MM, Mamun AA, Baxter J. 2022. Cultural identity and social and emotional wellbeing in Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander children. In: Family dynamics over the life course: foundations, turning points and outcomes. Cham: Springer International Publishing; p. 57–70. doi:10.1007/978-3-031-12224-8_4.

- Fenson L, Pethick S, Renda C, Cox JL, Dale PS, Reznick JS. 2000. Short-form versions of the MacArthur communicative development inventories. Applied Psycholinguistics. 21(1):95–116. doi:10.1017/S0142716400001053.

- Hadaway NL, Young TA. 2013. Celebrating and revitalizing language: indigenous bilingual children's books. Bookbird: A Journal of International Children's Literature. 51(3):56–68. doi:10.1353/bkb.2013.0062.

- Hallgren KA. 2012. Computing inter-rater reliability for observational data: an overview and tutorial. Tutorials in Quantitative Methods for Psychology. 8(1):23–34. doi:10.20982/tqmp.08.1.p023.

- Higgins R. 2005. The Treaty of Waitangi and the control of language in Aotearoa/New Zealand. International Journal of the Sociology of Language. 173(1):23–40.

- Hoff E. 2006. How social contexts support and shape language development. Developmental Review. 26(1):55–88. doi:10.1016/j.dr.2005.11.002.

- Huttenlocher J, Vasilyeva M, Cymerman E, Levine S. 2002. Language input and child syntax. Cognitive Psychology. 45(3):337–374. doi:10.1016/S0010-0285(02)00500-5.

- Ka'ai T, Smith T, Haar J, Ravenswood K. 2019. Ki te tahatū o te rangi: normalising te reo Māori across non-traditional Māori language domains. Auckland: Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori. https://workresearch.aut.ac.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0007/378898/Ki-te-tahatu-o-te-rangi.pdf.

- Ka'ai-Mahuta R. 2011. The impact of colonisation on te reo Māori: a critical review of the state education system. Te Kaharoa. 4(1). doi:10.24135/tekaharoa.v4i1.117.

- Karidakis M, Kelly B. 2018. Trends in Indigenous language usage. Australian Journal of Linguistics. 38(1):105–126. doi:10.1080/07268602.2018.1393861.

- Landis JR, Koch GG. 1977. The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics. 33:159–174. doi:10.2307/2529310.

- Lee W, Carr M, Soutar B, Mitchell L. 2013. Understanding the Te Whāriki approach: early years education in practice. Routledge. doi:10.4324/9780203075340.

- Lust B. 2006. Child language: acquisition and growth. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/s0272263108080510.

- Macalister J. 2008. Tracking changes in familiarity with borrowings from te reo Māori. Te Reo. 51:75–97.

- Macalister J. 2009. Investigating the changing use of te reo. NZ Words. 13:3–4.

- Matthews C. 2018. Approaches to Pākehā identity in Aotearoa/New Zealand. Journal of Policy and Culture (JJPC). 26:45–56.

- McConvell P, Thieberger N. 2001. State of Indigenous languages in Australia-2001. Canberra: Department of the Environment and Heritage.

- McIvor O, Ball J. 2019. Language-in-education policies and Indigenous language revitalization efforts in Canada: considerations for non-dominant language education in the Global South. FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education. 5(3). doi:10.32865/fire201953174.

- Ministry of Education. 1996. Te Whāriki. He Whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa: early childhood curriculum. Wellington: Ministry of Education. https://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Early-Childhood/Te-Whariki-1996.pdf.

- Ministry of Education. 2010. High frequency word lists: 1000 frequent words of Māori in frequency order. https://tereomaori.tki.org.nz/Teacher-tools/Te-Whakaipurangi-Rauemi/High-frequency-word-lists.

- Ministry of Education. 2013. Tau mai reo: the Māori language in education strategy 2019–2025. Ministry of Education. https://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Ministry/Strategies-and-policies/Ka-Hikitia/TauMaiTeReoFullStrategyEnglish.pdf.

- Ministry of Education. 2017. Te Whāriki: He whāriki mātauranga mō ngā mokopuna o Aotearoa. Wellington (NZ): Ministry of Education. https://www.education.govt.nz/assets/Documents/Early-Childhood/ELS-Te-Whariki-Early-Childhood-Curriculum-ENG-Web.pdf.

- Ministry of Education. 2022. Māori participation in early learning. Ministry of Education. https://www.educationcounts.govt.nz/__data/assets/pdf_file/0020/213176/Maori-participation-in-early-learning-report-RS-Changesc.pdf.

- Moewaka Barnes H, McCreanor T. 2019. Colonisation, hauora and whenua in Aotearoa. Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. 49(Suppl. 1):19–33. doi:10.1080/03036758.2019.1668439.

- Moon P. 2016. Ka ngaro te reo Māori language under siege in the 19th century. Dunedin: Otago University Press.

- Moorfield JC. 2005. Te aka: Māori-English, English-Māori dictionary and index. Auckland: Pearson Longman.

- Ninio A. 1992. The relation of children's single word utterances to single word utterances in the input. Journal of Child Language. 19(1):87–110. doi:10.1017/S0305000900013647.

- Oh YM, Todd S, Beckner C, Hay J, King J. 2023. Assessing the size of non-Māori-speakers’ active Māori lexicon. PloS One. 18(8):e0289669. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0289669.

- Rameka L. 2018. A Māori perspective of being and belonging. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. 19(4):367–378. doi:10.1177/1463949118808099.

- Ratima M, May S. 2011. A review of indigenous second language acquisition: factors leading to proficiency in te reo Māori (the Māori language). MAI Review. 1:1–26.

- Reedy T. 2000. Te Reo Māori: The past 20 years and looking forward. Oceanic Linguistics. 39:157–169. doi:10.1353/ol.2000.0009.

- Reese E, Barrett-Young A, Gilkison L, Carroll J, Das S, Riordan J, Schaughency E. 2023b. Tender shoots: a parent book-reading and reminiscing program to enhance children’s oral narrative skills. Reading and Writing. 36(3):541–564. doi:10.1007/s11145-022-10282-6.

- Reese E, Keegan P, McNaughton S, Kingi TK, Carr PA, Schmidt J, Mohal J, Grant C, Morton S. 2018. Te reo Māori: Indigenous language acquisition in the context of New Zealand English. Journal of Child Language. 45(2):340–367. doi:10.1017/S0305000917000241.

- Reese E, Kokaua J, Guiney H, Bakir-Demir T, McLauchlan J, Edgeler C, Schaughency E, Taumoepeau M, Salmon K, Clifford A, et al. (2023a). The Best Start (Kia Tīmata Pai): a study protocol for a cluster randomized trial with early childhood teachers to support children’s oral language and self-regulation development. BMJ Open. e073361. http://dx.doi.org/10.1136/bmjopen-2023-073361.

- Reyhner JA, Lockard L, editors. 2009. Indigenous language revitalization: encouragement, guidance & lessons learned. Flagstaff: Northern Arizona University Press.

- Riordan J, Reese E, Das S, Carroll J, Schaughency E. 2022. Tender shoots: a randomized controlled trial of two shared-reading approaches for enhancing parent-child interactions and children’s oral language and literacy skills. Scientific Studies of Reading. 26(3):183–203. doi:10.1080/10888438.2021.1926464.

- Ritchie J. 1999. The use of te reo Māori in early childhood centres. Early Education. 20:13–21.

- Ritchie J. 2002. Bicultural development: innovation in implementation of Te Whāriki. Australasian Journal of Early Childhood. 27(2):32–37. doi:10.1177/183693910202700207.

- Ritchie J. 2008. Honouring Māori subjectivities within early childhood education in Aotearoa. Contemporary Issues in Early Childhood. 9(3):202–210. doi:10.2304/ciec.2008.9.3.202.

- Romaine S. 2007. Preserving endangered languages. Language and Linguistics Compass. 1(1–2):115–132. doi:10.1111/j.1749-818X.2007.00004.x.

- Schaughency E, Linney K, Carroll J, Das S, Riordan J, Reese E. 2023. Tender shoots: a parent-mediated randomized controlled trial with preschool children benefits beginning reading 1 year later. Reading Research Quarterly. 58(3):450–470. doi:10.1002/rrq.500.

- Seals CA. 2021. Benefits of translanguaging pedagogy and practice. Scottish Languages Review. 36:1–8.

- Seals CA, Olsen-Reeder V, Pine R, Ash M, Wallace C. 2020. Creating translingual teaching resources based on translanguaging grammar rules and pedagogical practices. Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics. 3(1):115–132. doi:10.29140/ajal.v3n1.303.

- Simmonds H, Reese E, Atatoa-Carr P, Berry S, Kingi TK. 2020. Pathways to retention and revitalisation of te reo Māori: Report to the Ministry of Social Development. https://www.msd.govt.nz/documents/about-msd-and-our-work/publications-resources/research/children-and-families-research-fund/he-ara-ki-nga-rautaki-e-ora-tonu-ai-te-reo-maori.pdf.

- Skerrett M, Ritchie J. 2021. Te rangatiratanga o te reo: sovereignty in Indigenous languages in early childhood education in Aotearoa. Kōtuitui: New Zealand Journal of Social Sciences Online. 16(2):250–264. doi:10.1080/1177083X.2021.1947329.

- Smith AB. 2005. The bicultural curriculum: embracing indigenous frameworks. Albany (NY): State University of New York Press.

- Smith G, Hoskins TK, Jones A. 2012. Interview: kaupapa Māori: the dangers of domestication. New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies. 47(2):10–20.

- Smith LT. 2012. Decolonizing methodologies: research and Indigenous peoples. London: Zed Books.

- Snow CE. 1977. The development of conversation between mothers and babies. Journal of Child Language. 4(1):1–22. doi:10.1017/S0305000900000453.

- Spolsky B. 2003. Reassessing Māori regeneration. Language in Society. 32(4):553–578. doi:10.1017/S0047404503324042.

- Statistics New Zealand. 2022. Wellbeing statistics: 2021. https://www.stats.govt.nz/information-releases/wellbeing-statistics-2021/.

- Suggate S, Schaughency E, McAnally H, Reese E. 2018. From infancy to adolescence: the longitudinal links between vocabulary, early literacy skills, oral narrative, and reading comprehension. Cognitive Development. 47:82–95. doi:10.1016/j.cogdev.2018.04.005.

- Taani PM. 2019. Whakaritea te pārekereke: how prepared are teachers to teach te reo Māori speaking tamariki in mainstream primary schools? [Doctoral dissertation]. University of Otago.

- Te Taura Whiri i te Reo Māori. 2018. Te Maihi Karauna – crown strategy for Māori Language revitalisation 2018–2023. https://tetaurawhiri.govt.nz/te-reo-maori/maori-language-strategy/.

- Walker R. 2016. Reclaiming Māori education. In: Hutchings J, Lee-Morgan J, editors. Decolonisation in Aotearoa: education, research and practice. 19–38.

- Wyman LT, McCarty TL, Nicholas SE, editors. 2019. Indigenous youth and multilingualism: language identity, ideology, and practice in dynamic cultural worlds. Oxfordshire: Routledge.