ABSTRACT

Intercultural group work (IGW), where students from different nationalities work together, is one important way to develop intercultural competence, a key skill for engineering students. This longitudinal, qualitative study of five master’s engineering students follows their individual experiences in IGW and the affordances and challenges this way of working provides. In particular, the study problematises the use of the terms ‘home’ and ‘international’, often used to differentiate student experiences in IGW, by highlighting the range of student backgrounds and experiences which can be encompassed within them. The results show that the students’ self-positioning in their group and their sense of belonging to it are affected by a range of factors including previous experience, the nature of the group work and personal aspects such as openness and adaptability. In addition, belonging to the group can be a transient process influenced in part by critical incidents during the group work process.

Introduction

Improving the global competence of engineers has been of increasing interest within the engineering profession (Handford et al. Citation2019; Johri and Jesiek Citation2014), primarily due to the global nature of engineering (Royal Academy of Engineering Citation2007). This interest has been reflected in criteria from accreditation bodies such as ABET, ENAEE, and FEIAP as well as in technical universities’ mission statements and programme goals. For example, ENAEE raise the fact that engineering graduates should ‘function effectively in a national and international context’ (ENAEE Citation2021, 3.2 Programme Outcomes for Master Degree Programmes). Yet, as underscored by Handford and colleagues (Citation2019), the research on intercultural communication in engineering is still insufficient.

In the existing literature, different strategies for achieving global competence within engineering education have been presented (see Johri and Jesiek Citation2014 for an overview). Examples are student mobility, globally networked learning environments (May, Wold, and Moore Citation2015; Starke-Meyerring and Wilson Citation2008; Zaugg and Davies Citation2013), and internationally oriented projects or courses (Downey et al. Citation2006; Hazelton, Malone, and Gardner Citation2009; Lohmann, Rollins, and Joseph Hoey Citation2006). All of these interventions have merits, but present limitations when it comes to meeting the goals of intercultural competence for all students, since often only a minority of students participate in them.

Limitations concern not only the educational provision, but also the way intercultural communication is presented and discussed in engineering research. Many studies adopt a ‘culture-as-given’ perspective (Handford et al. Citation2019) where a person’s national culture is seen as a key indicator of their behaviour and the differences between national cultures are emphasised (e.g. Arzberger et al. Citation2010; Downey et al. Citation2006; Jesiek, Shen, and Haller Citation2012). This approach has been widely criticised for being overly simplified. The ‘culture-as-construct approach’, on the other hand, interprets national culture as one variable amongst others in a person’s identity (Handford et al. Citation2019; Holliday Citation2010; Lomer and Mittelmeier Citation2021). Other variables might include a person’s academic background, discipline, or international experience. In addition to problems of conceptualisation of intercultural communication, few longitudinal studies have been carried out, even though time is a significant factor of development in the exposure to an international environment (Poort, Jansen, and Hofman Citation2018). Studies are therefore needed that go beyond simplified categorizations of culture and investigate individual students’ experience of intercultural encounters in engineering education over time.

This study thus adopts a longitudinal, qualitative, culture-as-construct approach where five individual ‘home’ and ‘international’ engineering students were interviewed about their intercultural group work (IGW) over a year. The definition of ‘home students’ used in this article refers to students with citizenship in the country they are studying in, which can cover a range of backgrounds from those who have been based there for generations to recent immigrants. ‘International students’ are defined as ‘those who left their country of origin and moved to another country for the purpose of study’ (OECD Citation2020, 235) which can refer to students from all continents and include both speakers of English as a first language and as another language. However, the terms ‘home’ and ‘international’ mask the complexity of the students’ identity (see Bond Citation2019 for further discussion), and the usefulness of this distinction in explaining individual students’ experiences needs further examination.

Engineering programmes are the second most internationalised area of higher education, after business studies (OECD Citation2020), and as such, these programs often adopt collaborative educational practices such as intercultural group work (IGW). IGW is defined as ‘a collaborative approach to learning in which three or more students from different cultural or national backgrounds work together on set tasks, in or outside the classroom’ (Poort, Jansen, and Hofman Citation2018). Despite this, IGW has received relatively little attention in engineering education research (the most-cited studies on IGW have focused on business studies). IGW research in general has often used the distinction between ‘home’ and ‘international’ students in order to highlight these groups’ differences in IGW settings (Denson and Zhang Citation2010; Kimmel and Volet Citation2012; Montgomery Citation2009; Moore and Hampton Citation2015; Peacock and Harrison Citation2009; Strauss, U, and Young Citation2011). A closer examination of students’ individual experiences of IGW, adopting a culture-as construct approach, can shed new light on the variety of dynamics that lie behind the ‘home’ and ‘international’ identity labels. This problematization is critical for achieving the aim of fostering the global competence of future engineers.

Through following five ‘home’ and ‘international’ engineering students working in IGW over a year, this study aims to highlight their individual experiences from a culture-as-construct perspective. Their experiences highlight the affordances and challenges of IGW and at the same time, problematise the dualistic categorisation used in previous research.

The following questions guided the study:

What are the individual students’ experiences in intercultural group work?

Which factors affect the individual students’ experiences of intercultural group work?

How do these experiences change over time?

Student cultural identity – a theoretical framework

In order to capture students’ cultural identity, this study refers to theories that have at their core a conceptualization of culture-as-construct (Handford et al. Citation2019). Rather than defining the students solely in terms of nationality, this approach instead strives to provide a richer description of student identities based on their own personal narratives. Holliday (Citation2010), for example, recommends that rather than dividing the world into mutually exclusive groups where one group is seen as essentially different to another, cultures should be recognised as having blurred boundaries where people belong to and make use of a variety of cultural forms. Similarly, in exploring the complexity of cultural identity, Chao and Moon (Citation2005) propose a cultural mosaic model which expands cultural identity from nation states to other factors such as demographic, associative, and geographic. Demographic features include aspects that are generally physical in nature such as age, gender, race, and ethnicity. Geographic features involve the region that a person is from, for example, urban or rural. Associative features involve the formal and informal groups that a person belongs to, for example, a person’s profession.

This culture-as-construct approach can aid group dynamics. Amadasi and Holliday (Citation2017) suggest that ‘threads’ or connections between the members of the group are needed, to overcome the differences and create feelings of ‘insideness’. These threads are described as ‘diverse aspects of our pasts that mingle with the experiences that we find and the threads of the people that we meet’ (259). In other words, threads are areas that people have in common such as interests, family, or hobbies. It is through finding threads that individuals can come together.

In order to capture the fluidity of students’ cultural identities, this study adopts the conceptual metaphors proposed by Fougère (Citation2008). He argues that spatial metaphors can be useful ‘in analysing the identity construction processes of individuals involved in intercultural interactions, in order to understand these processes better’ (188). Posing that identity can be conceived as sensemaking – i.e. individuals’ making sense of their own experiences – he emphasises the importance of eliciting people’s narratives to understand identity construction in three key aspects: (1) the need for a sense of belonging (2) the opportunity to question and learn about one’s identity (3) the possibility of development and change (Fougère Citation2008, 187).

As part of a sense of belonging, Fougère uses the metaphors of space and place to frame how individuals may narrate their own identities in intercultural situations. In their own stories, individuals may choose to present themselves at varying degrees of ‘insideness’ and ‘outsideness’ (Fougère Citation2008, 192) to describe their sense of belonging to different situations and places, and how this belonging may change over time. In this sense, being ‘inside’ a place means identifying with it: while the place can be both physical and metaphorical, it is typically associated with a sense of ‘being at home’ in that situation.

In terms of identity, Fougère (Citation2008) distinguishes between the ‘place’ the students work in and the ‘space’, where the former represents ‘fixity and a familiarity’ (196) and the latter represents ‘something that one can explore’ (196). The ‘place’ can be a physical location or more metaphysical, connected to a person, social group, or a process (Scannell and Gifford Citation2010). Fougère (Citation2008, 193) comments: ‘people will typically experience varying degrees of identification to the place; whether they feel ‘at home’ or ‘foreign’, for instance, will have a critical impact on their identity construction in this context’.

Finally, in terms of development and change, Fougère lifts the possibility of third spaces defined as spaces where individuals can ‘redefine themselves in relation to the new, other meanings they encounter’ (Citation2008, 198). In connection with this, he mentions ‘in-between spaces’ where a person finds ways to be both the same as and different to the others they interact with and that this is the way to ‘intercultural personhood’.

Therefore, in studying students from different backgrounds working together in IGW, concepts of belonging, identity, and development can be useful to understand the participants’ own experiences and perceptions in IGW.

Intercultural group work (IGW)

As mentioned earlier, project-related group work is a popular pedagogical model within engineering education, and students are often expected to complete group assignments as part of the course grade. Although there are sound pedagogical reasons for group work, it can provide challenges for all students, but even more so, the more diverse the groups become (Distefano and Maznevski Citation2000; Poort, Jansen, and Hofman Citation2018). Many studies, predominantly from the UK, USA, and Australia, have outlined the advantages and disadvantages of IGW in higher education (see Spencer-Oatey and Dauber Citation2017 for an overview), with a general consensus that though it provides students with valuable real-life skills and experiences, there are a number of issues that can arise.

One key advantage of IGW is the skills and cognitive benefits that students with diverse backgrounds bring (Poort, Jansen, and Hofman Citation2018) which can be helpful in problem solving (Denson and Zhang Citation2010). Another key advantage is that of developing as a global citizen including learning about and respecting diversity and getting an international outlook (Denson and Zhang Citation2010; Montgomery Citation2009; Poort, Jansen, and Hofman Citation2018). Some students also pointed out IGW as enjoyable and valuable to them, particularly in preparation for their future working lives (Montgomery Citation2009; Peacock and Harrison Citation2009; Poort, Jansen, and Hofman Citation2018). It is also claimed that IGW has in general a positive rather than a negative effect on the individual average mark of all students (De Vita Citation2002; Kimmel and Volet Citation2012). Overall, IGW can provide both home and international students with crucial personal, academic and professional experience.

However, IGW can also pose notable challenges. One key challenge is that it entails more time and effort and a need to compromise, although, according to Poort, Jansen, and Hofman (Citation2018), perceived problems seem to disappear over time. Another aspect is that of selecting group partners. More home than international students stated that they preferred working with students from a similar background (Moore and Hampton Citation2015) and even after students have had positive experiences in diverse groups, they still tend to self-select into homogenous groups. One reason for this selection can be language proficiency factors and awareness of academic requirements (Moore and Hampton Citation2015). Communication is described as the largest challenge (Spencer-Oatey and Dauber Citation2017) including issues such as unequal language skills, communication styles, different accents, quietness, and use of other first languages than English though it is unclear whether this is as great a challenge in environments where English is the second or other language of most students.

Spencer-Oatey and Dauber (Citation2017, 222) underscore that the majority of studies have compared ‘home’ and ‘international’ students ‘with little or no recognition that there could be considerable variation within each of these categories’ and criticise this ‘simplistic bi-polar distinction’. In their study, they further divide the category of ‘international’ into EEA, China, and other overseas, but comment that their own groupings are still very general and disguise ‘the large amount of variation that inevitably exists within both regional and national groups’ (232). By questioning the use of binary labels of ‘international’ and ‘home’ in IGW, this study aims to highlight this variation.

Few IGW studies have included engineering students, despite this being such a prevalent and important way of working within engineering. This study focuses on the most common form of IGW in engineering education- group work within the same course and university- though the term could also encompass virtual teams. These groups are often teacher-selected since studies have shown that students tend to keep to their nationality groups where possible (Kimmel and Volet Citation2012; Peacock and Harrison Citation2009). Requiring students to work in intercultural groups in courses provides natural interaction between home and international students which in turn builds intercultural competence (Bergman et al. Citation2017; Lafave, Kang, and Kaiser Citation2015). This brings us full circle to the study at hand and the questions of the individual students’ own accounts of their IGW experiences over time and the factors affecting them.

Methods

This qualitative study has aimed at a reflexive, constructivist, longitudinal approach to capture the complexity and richness of the data (Lomer and Mittelmeier Citation2021). The participants, based at a technical university in Sweden, were following a project course over a period of five months within a two-year master programme broadly within the area of computer science and engineering. This course took place in the second term of the first year, so the students had already had six months at the university.

The class was equally divided in terms of nationality between Swedish (home) and students from six other nationalities, predominantly Indian and Chinese. The students worked in groups of five to six (there were six groups in total) and the groups were created by the course examiner partly according to preferences the students had given. These preferences included project choice, their own technical background knowledge, their schedule and their nationality. The lecturer deliberately mixed groups such that both Swedish and international students were represented in each group, since one of the main aims of the course was for students to work in international teams on an industry project. She also considered students who were likely to take initiative (she had met all these students in previous courses on the program) and ensured that each group had one or two of these students in order to move the project forward at the start. The students worked on one of two projects, three groups worked on one and three on the other, where the projects were connected to a company and the result was open-ended to replicate an authentic situation. As input for their project work, the students had several sessions on group dynamics, intercultural communication and a step-by-step guide to Scrum methodology, used extensively within computer engineering, which they were expected to use in their projects. The groups had weekly meetings with their supervisor to follow up issues with both the group and the project.

Participants

The students were selected using purposive sampling (Bernard and Bernard Citation2013) in order to achieve the purpose of capturing both home and international students’ experiences in IGW, and the course examiner asked for volunteers from both the home and international students. All five volunteers were interviewed, two from Sweden (1 male and 1 female) and three international (1 female from India, 1 female from China and 1 male from South America) (shown in ). Thus, the main nationality groups in the class were represented (Swedish, Chinese and Indian).

Table 1. Background details for the students interviewed.

The students worked in different groups apart from Julio and Yu Yang (see ), who were in the same project group. All names are pseudonyms. The country is given unless it might reveal the identity of the student, in which case the continent is given. The students signed a consent form for each of the interviews in accordance with Swedish research ethical protocol, where they agreed to the interview being recorded and the interviews being used as research data.

To get a sense of the students’ cultural mosaic (Chao and Moon Citation2005), demographic factors other than nationality were taken into account including previous work experience, travel experience and other (see ) to see whether these factors affected the IGW. As shown in , only two of the students had had experience abroad for a longer period of time. Julio had relatives in the US and had spent a year there. He had also had an internship in Northern Ireland as part of his bachelor’s, so he had lived in Belfast for a couple of months and travelled around Europe. David had taken time out from his engineering studies for two years to study Chinese where he met his Chinese girlfriend. He now returns to China every year. Though Yu Yang had not travelled a great deal, she had worked for an international company for a few years in China where she had worked in groups and with people from other countries.

The remaining two students, Sara and Pari, had little previous experience with other nationalities from studies or travel. Sara commented however that as part of her student union engagement, she had been involved in recruitment activities and had been on a leadership/group dynamics course in connection with those. All the students had studied their bachelor’s degree in their home countries.

Procedure

The interviews were semi-structured, lasted about one hour and were conducted face to face by the main author and another colleague. The author and colleague were both involved with the group dynamics input on the course but were not examiners. The three interviews contained open questions with different foci. The students were interviewed three times: at the start and end of the course, and one year later when the students were working on their master thesis. Interview 1 was focused mainly on ascertaining their previous experience of group work and their attitudes to it. It was also used to elicit attitudes to working in a diverse group in general and their initial response to their own group in this course. Interview 2 investigated how the project had functioned with their group on the course. Interview 3 involved a reflection on the programme as a whole and their experiences and reflections on the group work they had been involved in over the whole of the programme.

The interview data were processed in four steps, using Yin’s (Citation2016) analytic process of compiling, dissembling, reassembling and interpreting. At the compiling stage, the interviews were transcribed and compiled in NVivo 12 Pro. The dissembling stage followed, and initial coding was based both on the interview questions and on topics that seemed to emerge from the interviewees’ comments. For example, a particular focus was their discussion of positive aspects and challenges of working in diverse teams, both in general and their own group. In order to move forward towards the reassembling stage, and to ensure trustworthiness in the interpretation (Miles, Huberman, and Saldana Citation2014), this initial coding was verified in the interview transcripts through co-authors’ interpretations and discussions in debriefing sessions. This verification and discussion led to the final step, that of interpretation, where the broader themes of ‘insideness’ and ‘outsideness’ emerged. At this stage, in order to better contextualise the above themes, students’ experiences were connected abductively to theory drawing on Fougère’s (Citation2008) spatial metaphors for identity construction, to lift the students’ own perceptions of their identities across different situations and over time. The three metaphors are a sense of belonging; questioning and learning about one’s identity; and development and change. Consistently with our efforts to ensure trustworthiness and reflexivity, further comparisons of the theory with the interviews were done, entailing discussions about how best to present the data to bring out the students’ voices.

Results/findings

Sense of belonging: positioning in and attitudes to the group

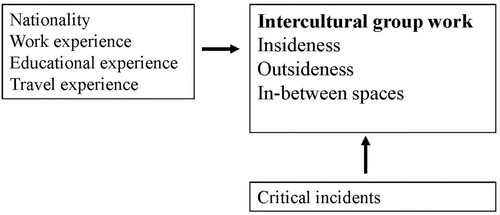

This section provides a brief description of each of the students through their accounts of their own belonging and positioning in the group, with a focus on the start of the group work. The main focus is the first two research questions, i.e. the individual students’ experiences in IGW and the factors that affected these experiences. The possible factors affecting the individual experience in IGW are summarised in :

These factors can lead to a feeling of insideness/outsideness which is interpreted on a continuum. Over time, these positions can change, in part caused by critical incidents during the process.

Sara

I'm one of those born and raised and stayed. (interview 1)

Group work was a familiar way of working for her ‘We’ve always had group works from when we were kids’ (interview 1) but at the same time, she described herself as having a different attitude to group work to her fellow engineering students where ‘they’re typical engineers [… .] they only care about the technical parts of that’ (interview 1).

As mentioned earlier, this was the first time she had worked in a group with other nationalities, and she was very positive. In the second interview, she used the words ‘different’ and ‘interesting’ a lot to highlight her experiences:

It was interesting to work with different people. Yeah, cause it’s just always the same kind of people, the same kind of Swedes, the same kind of engineers (interview 2).

Pari

It was good working in an international environment because it was my first time in going abroad so I really got to know what's the goods and what's the bad and how I can deal with things. (interview 2)

For Pari, the IGW seemed to provide a learning space to become more familiar with the international environment, not only academically but also culturally. For example, she commented that her group wrapped up the meetings by talking about ‘different kinds of stuff’ (interview 1) such as films and hobbies like skiing which helped her not only to find a place inside the group but also inside the university and society cultures.

Julio

I think I can learn a lot from it, not just in the academic way, but also as a person, as a person that likes to work and likes to learn from other people and from other cultures so I cannot be mistaken. Maybe I can be better for another future international group. (interview 1)

Despite being open and interested in IGW, mixed feelings about the group he was working in affected his sense of belonging. Initially, this was due to an absent team member and later, this was due to another group member going her own way in the project and not following the team decisions. Julio put a lot of time and effort into the project – he described the project as more time consuming than anything he had done before – and he spent long hours in the lab with one other student in the group to try to make the project work. He reflected:

this project was like a roller coaster feeling for me (interview 2)

His desire to be a part of the group and learn from it and them were challenged by group dynamic issues of students not participating and not communicating what they were doing. This affected his positioning within the group and the project. However, his comment above suggested that he was also looking beyond this project for lessons to apply to future projects.

David

And actually every group I've been in pretty much has been kind of that group where the work gets done, and then the chatty nice part is optional. (interview 1)

I know there are some differences between us that hasn't come to the surface, because I know I had this experience in China (interview 1)

In the group work, he selected a task early on in the project which isolated him from the rest of the group, and though he tried to return to the group towards the end, he felt that it was too late. He uses the word ‘outside’ several times to describe his position in the group: ‘I was already at the outside, and I couldn’t really pull it in to something’ (interview 2).

David expected differences from the start, from his previous travels, but the nature of his work and his pragmatic attitude to the project as a whole meant that he ended up moving away from the group.

Yu Yang

Because once we have a clear organization and everyone has their own roles and responsibilities, then no matter what nationality you are, you need to follow this procedure. So I didn’t see any big problem due to the different nationalities. (interview 1)

Like David, she took a role in the group which set her apart from them. She worked on a task alone despite the fact that ‘I didn’t have a strong technical background’ (interview 2) and spent long hours in the lab.

Development and change through critical incidents

The sense of belonging (or lack of) as expressed by the students is not a static state, but one influenced by events and actions over time during the group work (research question 3). The students brought up critical incidents, defined as ‘an interpretation of the significance of an event’ (Tripp Citation1993), which made them reassess their position in the group and in some cases pushed the group apart. The critical incidents highlighted in the interviews broadly covered the areas of communication and can be divided into two areas: communicating the project through writing a report and communicating about the project.

Communicating the project through writing

In the cases of Sara and Pari, the critical incidents concerned the group report which was handed in at the end of the course and was a key part of the final grade. The course examiner had emphasized the expectations on quality in this report, that it was preparation for the master thesis and would be marked accordingly. The students had handed in first drafts and had lectures concerning the requirements for the report.

Sara’s group experienced issues with putting the report together in that they were at different levels in terms of writing skills and experience in writing reports. She felt, however, that this worked itself out over time, partly due to improved English proficiency over the five months and partly due to finding ways of working together in the group. She described a flexible way of working with the group: ‘we laughed about it and fixed the things that we can and just hand it in’. (interview 2)

In her case, the experience illustrated the differences she had noted from the start and found interesting. She seemed to prioritise the goal of a functioning group over the academic goal of achieving a high grade for the course and the report writing experience brought them closer together.

In Pari’s group, it was a different situation. In the report writing process, the Swedish students in the group rewrote sections that another Indian student had written without asking and discussed this in Swedish in the document thus excluding the international members of the group. This caused a separation in the group between the Swedish and international students. Despite this, Pari contrasted this situation with her other course where she was working in a group of Indian students, and commented that the IGW was more successful, both in terms of efficiency (‘the Indian way of thinking about stuff and not doing them on time’ interview 2) and communication where she felt it was more difficult to voice her opinion in the Indian group.

Both Sara and Pari conclude in the third interview, a year after the course, that their IGW experience was beneficial, maybe surprisingly so in Pari’s case. Sara commented: ‘Engineering is surprisingly creative [… .] And diverse teams often lead to diverse solutions’ (interview 3) and Pari similarly brings up ‘a different thought process’ with a diverse group ‘which you would probably never think of if you always follow that straight line’ (interview 3). Both focused on the creativity offered by IGW and the possibilities of this in-between space although it caused challenges along the way.

Communicating about the project

For Julio, Yu Yang, and David, the critical incidents concerned communicating about the project. Julio and Yu Yang were in the same group and experienced a crisis of communication around the final group presentation which was also graded in the course. Unknown to the group, Yu Yang added slides at the last minute, suggesting a technical solution which the rest of the group were unaware of. For Julio, who had invested a lot of time and energy in the project and group, this was an act of betrayal to the rest of the group and upset him deeply. He felt that it made the group look unprofessional and felt that she was putting her own interests before the group’s. Yu Yang, on the other hand, who had struggled with the technical side of the project throughout the course, was proud that she had managed to solve a technical problem that no other group had managed to solve, and that she was able to present this on behalf of the group. In the final group meeting, she was surprised that the group did not appreciate her contribution and that they reacted negatively. This incident led both Julio and Yu Yang to critical insights about their participation in IGW.

For Yu Yang, it opened her eyes to the complexity of working with different cultures. She stated the importance of open communication with the team:

Even I thought from my point of view I thought is good for team, but if all the team members they didn't think so then must be something wrong with my understanding. At least I will try to understand why they think so. (interview 2)

Julio claimed that he embraced and was deeply transformed by his experience of other cultures. This process of change confused him, yet he clearly valued this process of personal growth. He felt that during the process of his master’s degree, he changed fundamentally, saying:

The other day I was having this thought that if I look myself at the mirror … I think that I have changed in so many ways, I wouldn't be able to recognize myself. (interview 3)

I felt that this opportunity in my life was the fact of me as a little bird just jumping out of the nest and learning to fly by myself. (interview 3)

I think that when you're living in other country, you are mixing yourself. I think that I have grabbed what I think that is really good, but I always remind myself of the things that I should not forget about my culture itself. I want to have a mix. (interview 3)

And, everyone else was totally the opposite to assertive … just going with the flow, or never saying anything at meetings and stuff like that. I guess it's okay in the beginning, but after a while it's very frustrating. (interview 2)

Discussion and conclusion

This study has followed the experiences of five engineering students in IGW over time in order to collect a rich account of their experiences with intercultural group work, and identify where these experiences diverge or overlap, independently from their classification as home or international. Their experiences highlight their insights into intercultural group work, their own role, their identities, the expectations of the group and the course and the role of an engineer. These insights change as time goes by and go beyond the current group and project.

By giving voice to these students, this article underscores that by only taking ‘home’ and ‘international’ labels into account, we oversimplify their personal experiences of IGW. This challenges existing research which has categorised students in this way, ignoring the vast differences that lie between members within these two very disparate groups. Through eliciting individual narratives about how students make sense of their own identity construction, we can capture students’ sense of belonging to new situations, their perceptions of their role in these situations, as well as how intercultural encounters such as those provided by IGW may allow them to question their identity and, at times, be a space for the exploration of new identities.

On an individual level, while culture and ethnicity naturally play a key role, there are also other aspects of the students’ cultural mosaic (Chao and Moon Citation2005) which affect their approach to and experiences of IGW. ‘Insideness’ in the group is affected by tangible elements such as previous education and work experience. Over time though, less tangible elements such as openness and adaptability created a space for exploring new identities. Fougère (Citation2008) argues that exploration is part of the journey and that this journey varies widely between individuals – some tying themselves more tightly to home in the process and others developing an intercultural personhood.

On a group level, findings in this study partly replicate previous studies in IGW. Communication in different forms has been lifted as a key challenge in this environment, (Spencer-Oatey and Dauber Citation2017) and this was similarly the case in the critical incidents highlighted above. However, in an environment when none of the students spoke English as their first language, the communication challenges focused less on English proficiency as such and more on aspects such as speaking time in the group, dealing with group writing and presentation tasks and in general, openness in sharing both task and personal information.

In the increasingly international higher education environment, preparing students to work in IGW is crucial, both for their academic careers and their professional ones. Universities can ‘offer a hybrid cultural space that enables people from different cultural groups to work together in a good atmosphere’ (Fougère Citation2008, 198). As previous research and this article have highlighted, IGW gives students the opportunity not only to exchange technical skills and knowledge but to develop as global citizens.

However, this article also highlights the challenges of IGW including students feeling a sense of belonging with the group. Whether a student feels ‘at home’ in a group is not necessarily about being a ‘home’ or ‘international’ student but how much of an insider they feel in the space, both physically, emotionally and existentially. ‘Insideness’ and ‘outsideness’ lie on a continuum and are affected by a range of factors which vary through time. Spencer-Oatey and Dauber (Citation2021) encourage teachers to provide ‘guided learning and support in order to facilitate students’ engagement, reflection and learning from these opportunities’ (13). These are key to supporting this complex and rich environment. But the first step is looking beyond the labels.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Becky Bergman

Becky Bergman is a senior lecturer at Chalmers University of Technology, Department of Communication and Learning in Science, Gothenburg, Sweden, where she works with communication with both students and staff, in particular intercultural communication. She is also a PhD candidate at the same university where her main research interest is intercultural communication in engineering education.

Raffaella Negretti

Raffaella Negretti is Associate Professor in academic and scientific writing at Chalmers University of Technology, Department of Communication and Learning in Science, in Gothenburg, Sweden. Her research focuses on academic and scientific writing, genre pedagogy, the development of writing expertise in higher education, and how writing stimulates cognitive development, critical thinking, and creativity. Her work has appeared in the Journal of Second Language Writing, Written Communication, Applied Linguistics, English for Specific Purposes, and Higher Education.

Britt-Marie Apelgren

Britt-Marie Apelgren is Professor in Language Education at the Department of Education and Special Education, University of Gothenburg in Sweden. She earned her PhD from Reading University, UK. She has participated in several large-scale empirical research projects involving studies of teaching and assessment, content and language integrated learning as well as the Swedish national assessment of English. Her main research fields concern teacher cognition and language teaching and learning, in particular students’ language proficiency in English.

Notes

1 A type of facilitator role in the Scrum model

References

- Amadasi, S., and A. Holliday. 2017. “Block and Thread Intercultural Narratives and Positioning: Conversations with Newly Arrived Postgraduate Students.” Language and Intercultural Communication 17 (3): 254–269. doi:10.1080/14708477.2016.1276583.

- Arzberger, P., G. Wienhausen, D. Abramson, J. Galvin, S. Date, F.-P. Lin, K. Nan, et al. 2010. “Prime: An Integrated and Sustainable Undergraduate International Research Program.” Advances in Engineering Education 2: 1–34.

- Bergman, B., A. Norman, C. J. Carlsson, D. Nåfors, and A. Skoogh. 2017. “Forming Effective Culturally Diverse Work Teams in Project Courses.” Proceedings of the 13th International CDIO Conference, Calgary, Canada, June 18–22.

- Bernard, H. R., and H. R. Bernard. 2013. Social Research Methods: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Bond, B. 2019. “International Students: Language, Culture and the ‘Performance of Identity’.” Teaching in Higher Education 24 (5): 649–665. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1593129.

- Chao, G. T., and H. Moon. 2005. “The Cultural Mosaic: A Metatheory for Understanding the Complexity of Culture.” Journal of Applied Psychology 90 (6): 1128–1140. doi:10.1037/0021-9010.90.6.1128.

- Denson, N., and S. Zhang. 2010. “The Impact of Student Experiences with Diversity on Developing Graduate Attributes.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (5): 529–543. doi:10.1080/03075070903222658.

- De Vita, G. 2002. “Does Assessed Multicultural Group Work Really Pull UK Students’ Average Down?” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 27 (2): 153–161. doi:10.1080/02602930220128724.

- Distefano, J. J., and M. L. Maznevski. 2000. “Creating Value with Diverse Teams in Global Management.” Organizational Dynamics 29 (1): 45–63. doi:10.1016/S0090-2616(00)00012-7.

- Downey, G. L., J. C. Lucena, B. M. Moskal, R. Parkhurst, T. Bigley, C. Hays, B. K. Jesiek, et al. 2006. “The Globally Competent Engineer: Working Effectively with People Who Define Problems Differently.” Journal of Engineering Education 95 (2): 107–122. doi:10.1002/j.2168-9830.2006.tb00883.x.

- ENAEE. 2021. “EUR-ACE Framework Standards and Guidelines.” Accessed August 8, 2021. https://www.enaee.eu/eur-ace-system/standards-and-guidelines/#standards-and-guidelines-for-accreditation-of-engineering-programmes

- Fougère, M. 2008. “Adaptation and Identity.” In Culturally Speaking: Culture, Communication and Politeness Theory Second Edition, edited by H. Spencer-Oatey, 187–203. London: Continuum International Publishing Group.

- Handford, M., J. Van Maele, P. Matous, and Y. Maemura. 2019. “Which “Culture”? A Critical Analysis of Intercultural Communication in Engineering Education.” Journal of Engineering Education 108 (2): 161–177. doi:10.1002/jee.20254.

- Hazelton, P., M. Malone, and A. Gardner. 2009. “A Multicultural, Multidisciplinary Short Course to Introduce Recently Graduated Engineers to the Global Nature of Professional Practice.” European Journal of Engineering Education 34 (3): 281–290. doi:10.1080/03043790903047503.

- Holliday, A. 2010. Intercultural Communication & Ideology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Jesiek, B. K., Y. Shen, and Y. Haller. 2012. “Cross-Cultural Competence: A Comparative Assessment of Engineering Students.” International Journal of Engineering Education 28 (1): 144–155.

- Johri, A., and B. K. Jesiek. 2014. “Global and International Issues in Engineering Education.” In Cambridge Handbook of Engineering Education Research, edited by A.Johri and B.Olds, 655–672. New York: Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/CBO9781139013451.040.

- Kimmel, K., and S. Volet. 2012. “University Students’ Perceptions of and Attitudes Towards Culturally Diverse Group Work: Does Context Matter?” Journal of Studies in International Education 16 (2): 157–181. doi:10.1177/1028315310373833.

- Lafave, J. M., H.-S. Kang, and J. D. Kaiser. 2015. “Cultivating Intercultural Competencies for Civil Engineering Students in the Era of Globalization: Case Study.” Journal of Professional Issues in Engineering Education and Practice 141: 3. doi:10.1061/(ASCE)EI.1943-5541.0000234.

- Lohmann, J. R., H. A. Rollins, and J. Joseph Hoey. 2006. “Defining, Developing and Assessing Global Competence in Engineers.” European Journal of Engineering Education 31 (1): 119–131. doi:10.1080/03043790500429906.

- Lomer, S., and J. Mittelmeier. 2021. “Mapping the Research on Pedagogies with International Students in the UK: A Systematic Literature Review.” Teaching in Higher Education, doi:10.1080/13562517.2021.1872532.

- May, D., K. Wold, and S. Moore. 2015. “Using Interactive Online Role-Playing Simulations to Develop Global Competency and to Prepare Engineering Students for a Globalised World.” European Journal of Engineering Education 40 (5): 522–545. doi:10.1080/03043797.2014.960511.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldana. 2014. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. Thousand Oaks: SAGE.

- Montgomery, C. 2009. “A Decade of Internationalisation: Has it Influenced Students’ Views of Cross-Cultural Group Work at University?” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (2): 256–270. doi:10.1177/1028315308329790.

- Moore, P., and G. Hampton. 2015. “‘It’s a Bit of a Generalisation, but … ’: Participant Perspectives on Intercultural Group Assessment in Higher Education.” Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education 40 (3): 390–406. doi:10.1080/02602938.2014.919437.

- OECD. 2020. Education at a Glance 2020: OECD Indicators. Paris: OECD Publishing. doi:10.1787/69096873-en.

- Peacock, N., and N. Harrison. 2009. “‘It’s So Much Easier to Go with What’s Easy’ ‘Mindfulness’ and the Discourse Between Home and International Students in the United Kingdom.” Journal of Studies in International Education 13 (4): 487–508. doi:10.1177/1028315308319508.

- Poort, I., E. Jansen, and A. Hofman. 2018. “Intercultural Group Work in Higher Education: Costs and Benefits from an Expectancy-Value Theory Perspective.” International Journal of Educational Research 93: 218–231. doi:10.1016/j.ijer.2018.11.010.

- Royal Academy of Engineering. 2007. “Educating Engineers for the 21st Century.” Accessed August 8, 2021. http://www.raeng.org.uk/publications/reports/educating-engineers-21st-century.

- Scannell, L., and R. Gifford. 2010. “Defining Place Attachment: A Tripartite Organizing Framework.” Journal of Environmental Psychology 30 (1): 1–10. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2009.09.006.

- Spencer-Oatey, H., and D. Dauber. 2017. “The Gains and Pains of Mixed National Group Work at University.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 38 (3): 219–236. doi:10.1080/01434632.2015.1134549.

- Spencer-Oatey, H., and D. Dauber. 2021. “Global Competencies and Classroom Interaction: Implications for Student and Staff Training.” In Meaningful Teaching Interaction at the Internationalised University, edited by D. Dippold and M. Heron, 55–68. London: Routledge.

- Starke-Meyerring, D., and M. Wilson. 2008. Designing Globally Networked Learning Environments: Visionary Partnerships, Policies, and Pedagogies. Rotterdam: Sense.

- Strauss, P., A. A. U, and S. Young. 2011. “'I Know the Type of People I Work Well With': Student Anxiety in Multicultural Group Projects.” Studies in Higher Education 36 (7): 815–829. doi:10.1080/03075079.2010.488720.

- Tripp, D. 1993. Critical Incidents in Teaching. Developing Professional Judgement. London: Routledge.

- Yin, R. K. 2016. Qualitative Research from Start to Finish. New York: Guilford Press.

- Zaugg, H., and R. S. Davies. 2013. “Communication Skills to Develop Trusting Relationships on Global Virtual Engineering Capstone Teams.” European Journal of Engineering Education 38 (2): 228–233. doi:10.1080/03043797.2013.766678.