ABSTRACT

This paper provides a ‘home international’ comparative analysis of education policy on social and emotional wellbeing, drawing on the case of the UK and its four distinct education systems of England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland have developed more holistic policy in this area, which stands in stark contrast to the disparate policies of England. These divergences in policy are likely to account for differences observed in the awareness, perceived value and ‘take up’ of policy by schools – what we refer to here as differences in ‘policy traction’ between the different systems of education. Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland had the highest rates of ‘policy traction’ compared to England where schools appeared adrift about policy in their jurisdiction. We consider these findings in light of challenges and opportunities for policy learning.

摘要

本文提供一个关于社会与情感幸福教育政策的比较分析, 采用的案例是英国英格兰、威尔士、苏格兰和北爱尔兰这四个不同区域的教育体系。威尔士、苏格兰和北爱尔兰已在该领域发展出比较全面的政策, 这与英格兰零散的政策情况形成鲜明对比。这些政策差异很可能解释了所观察到的学校在政策意识、认知价值以及 “采纳” 程度等方面的区别——这里我们指的是不同教育体系之间的“政策牵引”情况的差异。威尔士、苏格兰和北爱尔兰表现了最高程度的 “政策牵引”, 而英格兰的学校则在管辖中呈现出对政策的随波逐流。这些发现为政策学习的机遇与挑战提供思考。

关键词::

Introduction

The shift to promoting and measuring young people’s social and emotional wellbeing has been a major global development. It is now firmly entrenched within the discourse, policies and measurement instruments of international organisations such as the OECD, UNICEF and the World Bank, as well as national Governments and policy institutes. In education, this has been characterised as a move from a pathogenic approach to supporting children’s mental health - where the focus is on identifying target children and signposting them to specialist provision, towards a salutogenic approach (Weare Citation2010) aiming to promote children’s social and emotional wellbeing for the whole student population. We can see this in the way international organisations have broadened their perspective beyond the human capitalist orthodoxy of education for economic development (Xiaomin and Auld Citation2020). The OECD, for example, re-considered its position on the types of skills people will need up to 2030 with social and emotional skills (including empathy, self-efficacy, responsibility and collaboration) placed alongside cognitive and practical skills. On the one hand, this could be interpreted as valuing a broader view of the purpose of education in personal and societal development (beyond a utilitarian view of education for economic development). On the other hand, it might be regarded as a continuation of the status quo given that the need for promoting social and emotional skills is rationalised in terms of nation-building and economic development, for example, promoting normative modes of citizenship and responding to changing skill requirements from employers.

The term social and emotional wellbeing itself somewhat lacks conceptual clarity. In previous work, we have delineated between competing perspectives that place emphasis on building individual skills and universal moral values, from those that emphasise the provision of social resources, such as strengthening learner and student identity, social capital and respect for diverse ethical principles and cultures (Brown and Donnelly Citation2020). The kinds of measures developed by international organisations as indicators of wellbeing almost always come from an individual skills perspective, which privileges the capacities and individual functioning of people within societies and labour markets. For example, the OECD make the point that jobs which cannot so easily be replaced by technology (such as those dealing with complex human emotions, such as care work) often require the development of these social and emotional capacities. The implication here is that these are capacities to be instilled within the individual. Measures of this kind will likely foster normative discourses of social and emotional wellbeing and how this can be achieved through education, which may not ring true across different country contexts.

Recognising these different standpoints, we take a broad perspective on social and emotional wellbeing that includes; competencies, values and resources (see Author). As mentioned in relation to the OECD, by far the most dominant lens is the competency perspective, that hails from psychological theories, in approaching social and emotional wellbeing in developmental terms as social and emotional skills that children can be ‘taught’ in schools (Elias et al. Citation1997). Secondly, social and emotional wellbeing can be approached from a values-based perspective, which in the philosophical literature has taken a character and morals based approach, as reflected, for example, in the work of the Jubilee centre for Character and Virtues, at the University Birmingham (see Kristjánsson Citation2015). On the other side of the spectrum is an ethics-based approach which stems from broader fields of sociological and anthropological studies. This work rejects the universalising moralism of a character and morals-based approach in favour of a relative understanding of ethical values and a focus on the whole child’s development, including their socio-political understanding (see Ladson-Billings Citation2020). Finally, a resource-based approach focuses upon the various resources and capital children require in order to generate social and emotional wellbeing in schools such as a positive sense of learner identity (Becker Citation1952) and the cultural and social capital (Lareau Citation2002) that leads to social and emotional (not to mention economic) wellbeing. These different standpoints are important when examining the way different education systems conceptualise social and emotional wellbeing.

In addressing education policy on social and emotional wellbeing, we draw on comparisons between the four education systems of the UK (England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland) – an example of a ‘home international’ comparative analyses. As is the case globally, schools in these four education systems have become increasingly called upon to support children’s social and emotional wellbeing, due to a range of shared moral panics, including but not limited to; the purported increase in antisocial behaviour and lack of discipline in young people; an increasingly qualified graduate workforce that lack the requisite labour market skills to carry out the ‘people’ part of working (i.e. teamwork, time management, communication skills); a purported atomisation of young people confined to their bedroom in shunning real world socialising for social media ‘friendships’ and online gaming (Twenge Citation2017). A major contribution of this paper is to examine how social and emotional wellbeing is differentially conceptualised by policy when comparing across education systems of the UK, including the role schools are imagined as playing. In considering the distinctive policy-making between education systems of the UK, we examine how they filter down into schools; using the idea of policy traction to delineate system-level variances in how policies are perceived and used by schools across different education systems of the UK. We begin by contextualising our study within broader comparative research that has compared education systems internally within different countries, before introducing the UK context in greater depth.

‘Home international’ comparative analyses

Within the comparative educational research field, there exists a large body of work that has recognised distinctions in education policy that exist internally within nation states; what is referred to as ‘home international’ analyses. Internationally, there are studies of internal differences within countries that address several research topics and policy agendas. A study by Hega (Citation2001) has addressed the distinctive ‘educational cultures’ that exist across the 26 cantonal Governments of Switzerland, illustrating how language and identity are crucial to understanding the kinds of education systems that have emerged over time. In Australia, education policy is devolved to state-level; research has drawn comparisons between these systems across several topics, form example in terms of student retention (Ryan and Watson Citation2006), academic self-concept (Marsh Citation2004) and achievement levels (Rowe 2006) to name but a few. ‘Home international’ studies have been conducted across many other countries with decentralised systems of education, such as India (Asadullah and Yalonetzky Citation2012), Germany (Dedering Citation2009) and America (Logan, Minca, and Adar Citation2012).

It must be acknowledged that ‘home international’ comparisons are not without their difficulties, most pointedly in terms of complexities of comparison arising from contextual differences, such as demographic characteristics (Butler and Hamnett Citation2007). Notwithstanding these challenges, it is generally regarded that these are likely to be less significant than the contextual complexities arising from international comparisons drawn between nations states (Crossley and Watson Citation2009). Whilst important differences often exist internally within countries, not least socio-historically and in terms of national identity, it is likely the case that there are more commonalities than differences, especially around political/legal/economic systems, social relations, as well as the expectations and identifications of young people (Raffe et al. Citation1999). This makes ‘home international’ comparisons compelling; as a ‘window’ to look upon the effects of different policy agendas for comparatively similar groups over time. In terms of the UK, which is the example we draw on here, Raffe et al. (Citation1999) make the argument that research of this kind is significant because it has the potential to make a step change to highly contested theoretical questions as well as provide a bedrock of knowledge for policy learning.

There is a long history to the development of education and training in different parts of the UK; arguably distinctions have been present between the systems right from the outset, though to differing degrees, with Scotland diverging to a far greater extent than other nations (Bell and Grant Citation1978; Stephens Citation1999; Sturt Citation2013). Wales has always been much closer to England, having developed its education system at the same time as its incorporation with England (Sturt Citation2013). Northern Ireland’s schooling system has historically been divided along religious lines, though since separating from the Republic of Ireland (RoI) it has aligned more closely with England and Wales than the RoI (Raffe et al. Citation1999). Therefore, to varying degrees, the four parts of the UK have historically been developing ‘national systems’ (especially Scotland) before the relatively recent devolution of power and emergence of devolved administrations since the 1980s. It was the 1990s when the process of devolution culminated in education and training being the administrative and political responsibility of the four nations; England, Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. Within each province, political responsibility for education and training brought with it the establishment of separate Government agencies for curriculum, teacher training, inspection and other necessary functions.

There exists debate about the extent and nature of divergences between the systems of education that have emerged since devolution. Some have argued that Scotland and Wales have diverged further from England, whilst Northern Ireland and England have converged to some extent (Raffe Citation2005). At the school level, Raffe (Citation2005) makes a distinction between Scottish and Welsh education systems characterised by ‘common content and standardised universal provision’ versus the ‘choice, institutional diversity and collaboration’ observed in England and Northern Ireland. He argues that Wales and Scotland have continued to embrace the values of comprehensive education and strong connections between schools and the local community. This differs markedly from England, where market principles are more firmly entrenched as can be seen in the diversity of school types. Northern Ireland has followed England in adopting school policies orientated around diversity of provision, though this has not had the same impact in an already diverse school system, with faith schools and the Grammar school system.

The majority of comparative research within the UK draws comparisons between 2, or in some instances 3 countries, with many studies comparing England with another single nation. There are far fewer studies comparing all four countries, and those that have been done take the form of either analysis of existing policy (see, for example, Bamber et al. Citation2016; Donnelly and Evans Citation2018) or examining specific measurable outcomes through large-scale data (see, for example, Croxford and Raffe Citation2014). To our knowledge, this paper is the first of its kind to critically compare policy development on children’s social and emotional wellbeing across the UK nations.

Data and methods

Our research aimed to understand the nature of policy-making that exists across the four jurisdictions of the UK as well as how these are received by their respective schools. We draw on analysis of policy documents within each jurisdiction as well as a national-level surveys of schools that are further supplemented by qualitative interviews with teachers and headteachers across the four parts of the UK.

To discern the nature of policy across the four education systems, analysis was carried out on 26 policy documents. The initial selection of these documents was made according to four policy areas aligned with the social and emotional dimensions of schooling; pastoral care, discipline and behaviour, labour market preparation and educational inclusion. These foci informed keyword searches within the government policy databases across each of the four nation. In the countries where a large volume of policies existed (notably England), we selected the most recent, though other nations (especially Northern Ireland) had far fewer policies which meant in these nations relatively older documents were selected. In selecting these documents, we were conscious of the fact that policy is not only found in ‘official’ policy texts issue by Government departments, but is carried through a range of documents, artefacts and instruments that go beyond these official texts. Taking account of this broad view of policy, we also selected satellite documents that were cross referenced within the key documents. This included from across bodies responsible for curriculum development, Government departments of education, professional development bodies and other arms’ length organisations working at the secondary level of education. An inductive thematic analysis was conducted on the selected policy texts, guided by the following questions: how do the different ‘home’ nations conceptualise social and emotional wellbeing? What do they believe are the gaps in schools’ provision? In what ways do they seek to build social and emotional skills in their respective domiciles? What do they believe the school’s role to be? What is the nature of any solutions they propose and how do they envisage they should be delivered?

In order to garner the understandings and take up of policy in each part of the UK, we developed our own survey which was administered to a nationally representative sample of schools in each ‘home’ nation. The questionnaire collected information on teachers’ awareness of policy-making in their jurisdiction, the perceived value and ‘usefulness’ of such policies and their enactment within school. A sample of schools was derived for each ‘home’ nations separately using school-level information published on the websites of each education system. All state schools within each home nation were included in the sampling framework and a systematic random sampling approach was used with probabilities proportional to size (i.e. number of students). The final sample consisted of 156 schools (49 in England, 36 in Northern Ireland, 37 in Wales and 34 in Scotland), resulting in a margin of error for the full sample of +/- 6.5 at the 90% confidence interval. In other words, the statistics reported here are estimated to be within 6.5 percentage points of the real population value 90% of the time. The sampled schools were approach via email with individual links to complete the online-based questionnaire, and was answered by headteachers (60%) and staff members with responsibility for children’s social and emotional wellbeing (40%). Descriptive analysis was carried out on the data, comparing responses proportionally and drawing these comparisons at the country level - this is described more fully in the presentation of findings.

These survey data were supplemented by 8 qualitative interviews with headteachers and teachers from each of the educational jurisdictions. They were selected on the basis of having completed the original survey and voluntarily providing their email address to take part in a subsequent interview. The purpose of these semi-structured interviews was to follow-up on the survey and enable school staff to describe their awareness and enactment of policy in their own terms. In doing so, the interviews help to offer possible explanations for some of the patterns observed from the survey data, although the small interview sample requires care in any interpretations we derive. Interviews were recorded, transcribed verbatim and analysed taking a thematic approach. Analysis involved applying codes to data which were then used to make country-level comparisons to identify commonalities and differences between schools in different education systems of the UK. In what follows, all participants, schools and other organisations are fully anonymised.

Policy convergence and divergence across the ‘home’ nations

The analysis of policy documents across the UK ‘home’ nations revealed both points of convergence and divergence in terms of how social and emotional wellbeing was conceptualised, how the school’s role is imagined, and the envisaged enactment within schools. Whilst there are clearly important convergences, especially in how social and emotional wellbeing is conceptualised, there are also signs that the minority ‘home’ nations (Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales) are diverging substantially from England in their policy-making, which is worthy of critical debate.

There was a marked convergence in the way ‘home’ nations conceptualise social and emotional wellbeing, which was chiefly understood as individual ‘competencies’ to be developed in the child, albeit with important caveats within the minority ‘home’ nations. The minority ‘home’ nations also recognised the importance of resources and values in their conceptualisation, manifest in their attention paid to community relations (in Northern Ireland), the impact of poverty (in Wales) and national identity (in Scotland and Wales). The way that these resources and values are understood can to some extent be linked to the wider political, social and economic landscape of the UK (Donnelly and Gamsu Citation2020).

Alongside this similar framing of social and emotional wellbeing as individual competencies, there are notable points of difference in the nature of how education systems address the policy issue. It is clear from the policy developed in each ‘home’ nations that a marked divergence exists here, between minority home nations which take a holistic view, embedding social and emotional wellbeing more substantively within schools (Wales and Scotland), and England which has relied on a stream of disparate policies that have emerged outside of an over-arching framework. We now compare across the ‘home’ nations to explore these points of convergence and divergence in greater depth.

Scotland

Scotland has approached schools’ role in supporting children’s wellbeing primarily through taking a holistic view of how it should be delivered within schools. This involves the development of an innovative new education curricula Curriculum for Excellence Scottish Government (Citation2009) that integrates the importance of social and emotional wellbeing across all curricular areas. This policy signals the role in relation to four key areas in order to prepare children for ‘learning, life, and work’ (10). Like other UK nations, Scotland approaches wellbeing from a primarily competency perspective in developing skills such as ‘communication, resilience, and an ability to form positive relationships’ in order to be applied to the four different objects; children’s academic achievement, personal health (including mental) preparedness for the labour market as well as participative and responsible citizens, signalling that Scotland sees the role of schooling to extend way beyond children’s academic learning, primarily through developing self-governing behaviours for their employability and wellbeing (for example through the seven ‘skill-sets’ required for the ‘modern labour market’ Scottish Government Citation2009, 18). It also advocates cross ministerial working through the influential Scotland is Getting it Right for Every Child policy (Scottish Government Citation2017) that aims to bring together a range of services, programmes and guidance to support wellbeing. This policy is important in mediating the predominant individualistic focus upon by recognising the importance of children’s varying resources to achieve this. In other policy areas, the emphasis on relationships and connectedness with others trumps individual responsibility however, as the importance of taking a whole-school approach in building ‘positive school culture’ (Scottish Government Citation2018, 5–6) is advocated in their behaviour policy, which avoids an authoritarian approach. Where Scotland stands out as distinctive from other nations, however, it respects to its SEND policy, where it emphasises the influence of contextual factors such as ‘family circumstances’ and social and emotional factors’ (Scottish Government Citation2017, 23–24). In emphasising these barriers Scotland avoids a deficit model in taking an empowerment perspective.

Northern Ireland

Northern Ireland has developed the fewest policies of the four UK nations, and instead they focus on social and emotional wellbeing as a set of skills to be developed in children. In contrast to the stand-alone policies evident in England (and to some extent Wales) Northern Ireland has integrated its focus on wellbeing with a holistic approach to the curriculum. This is most evident in the key stage 4 policy (Council for the Curriculum Examinations & Assessment Citation2020a) which promotes the development of communication skills and ability to work with others across all other skills and they also appear across each other policy areas. To a lesser extent thinking and emotional competencies are also advocated across various wellbeing agendas such as ‘entrepreneurial thinking’ and innovation which feature in PSHE areas and labour market preparation, see Learning for Life and Work (Council for the Curriculum Examinations & Assessment Citation2007) as well as ‘self-control’ which appears in the PSHE and behavioural policy. Relationships (and sex) education has been a long-standing statutory requirement in Northern Ireland (Council for the Curriculum Examinations & Assessment Citation2020b) while in England and Wales this is fairly recent. The importance of community relations is also reflected in their Children and Young People’s Strategy 2017–2027 (Northern Ireland Executive Citation2016) which signals an explicit focus on wellbeing in a broad perspective. Significantly this recognises there are differences in children’s resources in reflecting a capital-based perspective on a sense of fairness and justice over health and resources. In the area of behaviour policy, Northern Ireland identifies a number of competencies and morals-based skills such as good behaviour, respect for authority and for others, these are to be promoted through a whole-school culture. Like Scotland Northern Ireland also promotes an inclusive culture within SEND policy in ensuring that all children have equal access to the curriculum and learning opportunities (see Dept of Education, Northern Ireland Executive Citation2005 p. 41) and as such there is some recognition of the importance of a resources-based understanding of wellbeing.

Wales

While Wales is the most similar to England of the three home nations, there are also parallels between Wales and Scotland in that both see social and emotional wellbeing as central to their new curriculum strategy, see Curriculum for Wales 2022 (Welsh Government Citation2019). As per all UK nations the dominant perspective on social and emotional wellbeing takes a competency perspective through an emphasis on building communication and relationships skills and resilience, similar to England, but there is also evidence of morals and ethics-based approaches such as trust, respect and empathy. A unique aspect within Wales’ approach to social and emotional wellbeing is in promoting the linguistic skills of Welsh and English, signalling an ethical dimension through promoting learners’ understanding of values, rights, cultures and ‘heritage of Modern Wales’. This is in contrast with England who see linguistic skills in purely instrumental terms. Like Northern Ireland, Wales also strongly promotes ‘global citizenship’ as relevant within the objective of schools to ‘develop [learners’] sense of fairness and justice about resources and wealth’ as well as to tackle ‘injustice, prejudice and discrimination’ (Welsh Assembly Government Citation2008, 4). There is also a strong relational dimension to the Welsh behaviour policy approach in promoting ‘an ability to form positive relations’, ‘resilience’ and ‘social skills’ (Welsh Assembly Government Citation2010, 101). It was in the labour market policy domain that the approach of Wales was distinctive in promoting the building of children’s personal, cultural and national identity. This collective emphasis upon social and emotional wellbeing for the purposes of nation-building and social cohesion was in tension with the high value placed upon assertive agentic skills they also promoted such as entrepreneurial skills, critical thinking and motivation also evident in other home nations. The SEND policy in Wales broadly mirrors that of England, for example in relation to the four categories of ‘need’ (Welsh Assembly Government Citation2004). However, while not discussed as expansively as in English policy, the Welsh guidance provided a far greater focus on how schools can support each category, reflecting more of a capital based approach.

England

Reflecting its size and policy machinery, England has developed by far the most extensive policy concerning Social and emotional wellbeing. However, in contrast to the other home nations, this has taken something of a piecemeal fashion in lacking any single overarching policy or in relation to the curriculum. Of all the four UK nations, England also reflects the most narrowly focused competency perspective on social and emotional wellbeing, with an overarching emphasis upon resilience as an individual competency, and one that cross-cuts policy areas. One of the distinctive policies in England is the Character Education policy (Department for Education Citation2019a) adopting an overwhelmingly morals-based approach to what are termed ‘virtues’ (7) including respect, integrity and a ‘habit of service’. These same virtues are also promoted through England’s PSHE curriculum, which now also includes the statutory Relationships and Sex Education and Health Education (Department for Education Citation2019b). This policy introduces a specific focus on children’s ‘mental wellbeing’ which reflects England’s increasing responsibilities in supporting children’s mental health, as underpinned by the influential cross ministerial policy; Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services (DoH/DfE Citation2017).

England’s statutory approach to behaviour policy (Department for Education Citation2016) is the most authoritarian of the four UK nations, with predominately compliant competencies promoted such as ‘self-regulation’ and ‘self-discipline’. England’s approach in terms of labour market preparation reflected a similar competency perspective to that of the other UK nations, in promoting teamwork and entrepreneurial skills. However, it was distinctive as the only one to be truly led by industry guidance; there was particular recognition of the importance of building social capital through community and particularly local employer involvement in raising aspirations, thus reflecting elements of a resource-based perspective. As with other UK nations, the SEND policy area (DfE/DoH Citation2015) is predominantly concerned with building competencies, such as communications and social skills, however, England is unique in placing a new focus on the importance of ‘raising aspirations’ which is identified as a key change in policy direction from the previous SEND code (14). Despite the competency framing, the onus here is upon schools (and other state providers) to ensure these skills and values are developed, therefore demonstrating more recognition than in other areas of a capitals-based perspective.

These points of convergence and divergence in policy across the ‘home’ nations raise questions about how policies are received by their respective schools and what ‘traction’ they carry. Are there differences across the UK in how schools understand policy-making in the area of social and emotional wellbeing? Are these associated with the distinct policy approaches taken across the ‘home’ nations? ‘Home international’ comparative research of this kind offers the chance for policy learning about the relative success and failures of diverse education systems within countries like the UK.

‘Policy traction’ across the UK ‘home’ nations

Our research across the UKs four education systems identified differing rates of ‘policy traction’; evident from country-level differences around the awareness, understanding and enactment of policy. We draw on the idea of ‘policy traction’ to describe the nature of how policies are received by schools across the four UK education systems – with high rates of ‘traction’ evident when the policies of an education system achieve greater impact within their schools, in terms of the ‘hold’ they have, manifest by their awareness and enactment within schools.

Despite being the most prolific in producing education policy in this area, English policy stands out as having significantly less ‘take-up’ by schools compared with Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. This is significant given that our policy analysis suggested these minority ‘home’ nations have been diverging from England in their policy development, which might begin to help explain why they appear more successful influencing their schools. Our survey data show that schools in England were much less aware of policy in this area and said they valued them less than was the case in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. In England, 62% of teachers agreed they were aware of policy in this area compared to 85% in Northern Ireland, 82% in Scotland and 69% in Wales. The differences in how schools within each country perceived the value of policy-making were also pronounced – with England again faring worse than the minority home nations. In England, 60% of teachers said that English policy was helpful or very helpful, compared to over 90% of Scottish and Northern Irish teachers, and 84% of Welsh teachers.

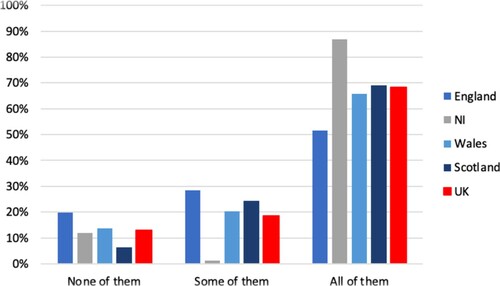

As might be expected, our data also show that the countries whose policies are valued more by schools also reported using them more frequently in developing their school-based provision on social and emotional wellbeing. compares the ‘take up’ within schools of policies developed by each of the home nations. Around 70% of Scottish Schools, and nearly 90% of Northern Irish schools said they used all of the policies developed in their respective home nations. This compares with just half of the English schools saying the same, and a fifth of English schools saying that they don’t use any of the English education policies at all. That said, in England, a third of schools reported using ‘some’ of the English policies, suggesting they draw on policy in a more piece-meal fashion compared to what seems a more universal take-up in other countries. On one level, this could make sense give our analysis of policy within the UK ‘home’ nations revealed more disparate ‘stand-alone’ policies in England speaking to specific agendas. Perhaps schools in England draw on specific policies when they require specific information, for example, knowledge on safeguarding. To understand this more fully, a closer look is needed at which policies schools and teachers are referring to here and what could account for these differing rates of ‘policy traction’.

The specific policies teachers have in their minds when they think of policy-making on social and emotional wellbeing in their country provide a glimpse into what might be driving these differing rates of traction. We asked teachers who took part in the survey to name all the policies they are aware of in their country; these were then tallied, and the most frequently mentioned policies within each home nation are shown for England (), Northern Ireland (), Wales () and Scotland ().

Table 1. Most frequently mentioned policies in England.

Table 2. Most frequently mentioned policies in Northern Ireland.

Table 3. Most frequently mentioned policies in Wales.

Table 4. Most frequently mentioned policies in Scotland.

The policies which are reportedly mentioned (and not mentioned) by teachers here provide some possible explanations about why the policies of countries have achieved different rates of ‘policy traction’ – especially why England appears to have fared less well, and the apparent success of minority ‘home’ nations. Comparing between countries, there appears to be greater assimilation between the key policies advanced by the three minority home nations and what are referred to most by their schools. Schools in Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland all mention first and foremost their countries’ flagship policy – Getting it Right for Every Child/Curriculum for Excellence (Scotland), New Curriculum for Wales (Wales) and Education, Relationships and sex education (Northern Ireland). Schools here are aligned with the key policies developed in their country – from these data, they appear to have a stronger awareness of what is being advocated by their ministries of education.

English schools, on the other hand, name the policies Keeping children safe in education and Social and emotional aspects of learning (SEAL) most frequently. The first of these policies is more about the legal duties of child protection, whilst the second is not a policy at all – SEAL is a programme designed to promote social and emotional skills developed by a third- sector organisation, not the English education ministry. Crucially, English schools do not mention what are arguably some of the flagship education policies in England – for example, Character Education or recent initiatives around extra-curricular activities and building resilience. This omission is striking given their prominence in the context of policy in England. Character Education, for example, has been high on the policy agenda for the last six years, as championed by former Education Secretary Nicky Morgan, and was underpinned by the injunction to schools to instil the ‘drive, grit and optimism’ (Department for Education Citation2015, p. 29) in children to ensure ‘the development of character and [achievement of] mental wellbeing’. Successive Education Secretaries have also rallied behind Character Education including Damien Hinds who planned to revive Morgan’s failed National Character Award schemes – in deference to strong professional criticism – and finally becoming formalised under the current Character Education Framework (DfE Citation2019b).

These differences in ‘policy traction’ were also evident from the way teachers we spoke to across the ‘home’ nations spoke about policies in their jurisdiction. The teachers we spoke to in Scotland and Wales immediately mentioned their new curricular when asked about policies on social and emotional wellbeing in their country – it was at the forefront of their mind when prompted on the topic. They also had a high level of detail about the policies as well as the broader vision and aim for which their Governments are attempting to achieve, for example, in Wales:

… the four core purposes of what we want to achieve in the new curriculum there’s a lot around the subject of health and wellbeing – which perhaps hasn’t had the priority, or that’s what everybody says – it has not had the priority, when it was a very results driven curriculum up until now. And they seemed to be in contradiction to each other. Whereas now you know, I think, and I hope in Wales, we’ve realised that if you haven’t got a healthy, confident individual, then you’re not going to get any sort of learning taking place.

This headteacher was acutely aware of the Government’s recognition of how learning is impacted by broader contextual factors, especially the unequal starting points in life children face and consequential impacts on their health and wellbeing. There is acknowledgement here from the headteacher of the Government’s thinking about how the new curriculum is seeking to improve children’s learning through a holistic approach focussed on the wider self, in illustrating a clear alignment with the Welsh Government’s strong emphasis upon values before achievement and social justice in the New Curriculum for Wales. The headteacher’s recognition for the economic barriers to learning chimes with the key stage three designated curriculum theme of ‘wealth and poverty’ with associated aims to build children’s social and emotional skills on this theme including to; ‘develop a sense of fairness and justice about the access to resources and wealth’; ‘develop opinions about exploitation and poverty’ (7) and ‘Develop skills to challenge injustice, prejudice and discrimination’ (4). The high value placed on Welsh policy and its strong take-up by Welsh schools as indicated by the survey data was evident in the accounts of teachers we spoke with in Wales – for example, another headteacher from Wales reflected on an aspect of health and wellbeing around citizenship and belonging:

So, certainly there’s lots about citizenship that perhaps hasn’t been there before about their social-, their need to socially relate to others … So what does it mean to be belonging? What does it mean to belong? … And I talk a lot about what harmony is. And that means we’re all singing the same song but not necessarily the same part. So that you can be an individual within the context of a whole and I think children are particularly waylaid by their online life and I think we have a responsibility to talk about their life outside of that, now more than ever, really what it means to be their own person.

Similarly, in Scotland, where schools reported the greatest awareness of policy, the teacher we spoke to was very much tuned into the way the Scottish Government defined social and emotional wellbeing.

… we have 8 wellbeing indicators that are taken into consideration across all- so there’s a health and wellbeing policy, that’s the responsibility of all staff and within that there is specific benchmark criteria, that’s an expectation of a school to embed across the curriculum we also have 8 wellbeing indicators SHANARRI, I don’t know if you’ve seen that before so it’s Safe; Healthy; Active; Nurtured; Achieving; Responsible; Respected, and within those components we are developing the individuals pupils across the board, the core mental social and emotional skills.

The traction here is strong - the 8 wellbeing indicators embedded within this school are the same as those advanced by Scottish Government policy-makers – they appear to be enacting the policy in a way advocated by Government. The language contained within policy (e.g. ‘safe, healthy, nurtured, active, achieving, responsible, respected) had seeped into social and pedagogic relations of daily school life, though not without challenges.

I certainly see us as a school driving forward, particularly now more than ever, the importance of the positive relationships, the understanding of a child’s wellbeing and as I said that’s all within the nurture principles. Part of the work that we’ve been doing in professional development for staff is about sharing these nurture principles because really when we go back [after lockdown] it is going to be really important that they are aware of these within their classroom because of the trauma that’s been experienced by pupils and certainly looking out for supporting emotional and social skills within the classroom, it’s going to be vital to the pupils achieving success, in any particular area.

The high rate of traction achieved by policy on social and emotional wellbeing in Scotland and Wales was not present to the same extent in England. Reflecting the same patterns evident in our survey data, when asked about policy of the English ministry of education, there was not the same degree of surety and confidence about what policies exist and what are considered the primary policies advocated by their Government.

Interviewer: So are you aware of- what’s your awareness and perception of government policy, then?

Mr Smith, Teacher (England): It was minimal. I mean, I knew of it, because some of it was-, some of the things I was looking at seemed a bit dated. So I just thought, well, I’ll just double check if there’s anything new out there. I didn’t feel there’s any current or new policy under present circumstances. I don’t know whether that is the case. But I certainly couldn’t readily find things. I even went back on the government website just to double check that I hadn’t missed something … .

… but the thing is that you get so many documents don’t you that you kind of, you’ve just got to focus on the ones that are important to you. Otherwise, you could spend your whole day just reading documents. So you’ve got to kind of focus on what’s important at the time I guess.

Rather than a central policy driving their approach and practice, a teacher in England reflected on how they have established their own school-led approach.

… And because we’ve been doing a lot of social emotional stuff for a very, very long time. I think we just, not purposely, we don’t always think what it is you are supposed to be doing if there’s a statutory thing, or what’s the government guidelines, because we have been doing it for well over 10 years now. It’s just embedded in our practice, but that doesn’t mean it’s the best practice. It’s just what we’ve always done.

A separate question from whether policies gain ‘traction’ in countries is the question of whether such policies are effective in addressing concerns around children’s social and emotional wellbeing. It could be that the kind of school-led approach described here by Mr Smith is more effective at addressing some of the contextually specific problems children in his school face – some could argue that there is a narrower scope to do this in ‘home’ nations where universal approaches have been applied.

Northern Ireland stands out as an education system with strong policy traction, with schools highly aware of policy and placing great store by it in their practice. One of the likely reasons for this could be the existence of their local Education Authorities which appear to be important in translating Government policy for schools.

But I think that that’s mainly where our information comes from, from the EA [Education Authority] so the Education Authority rather than [the Government ministry] necessarily. [The Government ministry] produce the document and then EA carry out the training and whatever else in relation to it. And there’s been a quite a bit of stuff recently about managing critical incidents … there was good stuff around that and there was actually a good training around trauma inspired leadership and anti-bullying this year as well all coming from EA. I know, EA has been, you know, proactive in those areas.

This kind of policy translation by intermediary policy infrastructure was not apparent to the same extent in England, Wales or Scotland. In England, the role of local education authorities have severely diminished in recent times, with the advent of academy chains now forming the majority of schools’ wider systems of support. Schools in other countries would tend to refer directly to their Government’s policies themselves, with little reference to local authority bodies, whereas in Northern Ireland it seemed that these bodies played a pivotal, if not central role. Indeed, the Northern Irish head teacher we spoke to discussed them as if they were the first port of call for education policy. The Education Authorities in Northern Ireland are strongly connected to schools, providing advice and support in the form of training sessions, resources and their own digests of policy. It could be that this kind of policy intermediary is accounting for their high rate of traction.

It is also significant that of all four nations, schools in Northern Ireland placed the greatest focus on the behaviour and discipline domain of social and emotional skills, being the third most cited policy. Given the history of political unrest in Northern Ireland it is understandable why the behavioural dimension is so prominent.

Conclusion: prospects for policy learning?

This paper provides the first UK ‘home international’ comparative analysis of education policy in the area of social and emotional wellbeing – a critical issue education systems around the world are grappling with, especially since the COVID pandemic. We find evidence of some convergence in policy on a conceptual level (in terms of how social and emotional skills are broadly conceived as ‘individual competencies’) but also notable divergences. These divergences are to some extent underpinned by competing conceptualisations of social and emotional wellbeing, beyond a singular focus on individual competencies. This has implications for the measures used to draw comparisons across different country contexts. Any measures which spread normative understandings of social and emotional wellbeing as ‘individual competencies’ (as is the case with PISA) will likely miss these more pluralistic conceptualisations.

The divergences in the development of policy on social and emotional skills across the four education systems corresponded with differences we observed in the awareness, perceived value and ‘take up’ of policy – what we refer to here as the ‘policy traction’ between ‘home’ nations. The apparent success of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland in achieving greater rates of policy traction could be attributed to their development of holistic frameworks which embed social and emotional skills more substantively within schools. Indeed, it was striking how teachers in these minority home nations were aligned with their jurisdiction’s policy, with detailed knowledge and insight that was suggestive of strong ‘take up’. The lower rates of traction in England could suggest that their extensive policy in this area is obfuscating a clear and coherent policy message on the topic. Compared to their neighbouring schools in minority home nations, the survey and interview data suggested English teachers were seemingly adrift about policy in this area within their jurisdiction. The comparatively lower traction of policy in England could suggest suggests schools in this jurisdiction have greater onus to develop practice themselves with less direct shaping through policy. Whereas it is entirely plausible in the minority home nations that school practice is more in line with policy-makers intentions. It is of course only possible to speculate about the enactment of policy within schools without more ethnographic studies of how schools themselves differ across the ‘home’ nations.

In thinking through possible implications for wider policy development, there are clearly challenges to making any case for the relative merits of either England, Wales Scotland or Northern Ireland. On one level, it could be argued that holistic policy frameworks are the kinds of policies countries should adopt to address in addressing the issue of children’s social and emotional wellbeing – given the relative success of Wales, Scotland and Northern Ireland. But on the other hand, without more qualitative information about how Welsh, Scottish and Northern Irish policy is experienced by children themselves, and how this compares to English children’s experiences, it is difficult to be sure on the merits of holistic policy frameworks. The experiences of children themselves are crucial to making any judgement about the relative effectiveness of different policy approaches. In discerning distinctive policy approaches across the home nations, and evidencing the differences in policy traction these garner, our paper makes a strong case for further research comparing children’s experiences across different education systems.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Michael Donnelly

Michael Donnelly is an Associate Professor at University of Bath whose interests lie in the sociology and geographies of education, researching how education is interconnected with broader societal mechanisms, such as the (re)production of inequality and identity formation.

Ceri Brown

Ceri Brown is an Associate Professor at the University of Bath. She is interested in the impacts of education policy on children's schooling experiences, particularly for those who experience educational binds such as living on a low income, irregular school transitions, mental health challenges, and those at risk of early school leaving.

References

- Asadullah, M. N., and G. Yalonetzky. 2012. “Inequality of Educational Opportunity in India: Changes Over Time and Across States.” World Development 40: 1151–1163.

- Bamber, P., A. Bullivant, A. Glover, B. King, and G. Mccann. 2016. “A Comparative Review of Policy and Practice for Education for Sustainable Development/Education for Global Citizenship (ESD/GC) in Teacher Education Across the Four Nations of the UK.” Management in Education 30: 112–120.

- Becker, H. S. 1952. “Social-Class Variations in the Teacher-Pupil Relationship.” The Journal of Educational Sociology 25: 451–465.

- Bell, R., and N. Grant. 1978. Patterns of education in the British Isles.

- Brown, C., and M. Donnelly. 2020. “Theorising Social and Emotional Wellbeing in Schools: A Framework for Analysing Educational Policy.” Journal of Education Policy 1–21. doi:10.1080/02680939.2020.1860258.

- Butler, T., and C. Hamnett. 2007. The Geography of Education: Introduction. London: Sage.

- Council for the Curriculum Examinations & Assessment. 2007. Learning for Life and Work. Belfast: Council for the Curriculum, Examinations & Assessment.

- Council for the Curriculum Examinations & Assessment. 2020a. Key Stage 4. Belfast: Council for the Curriculum Examinations & Assessment.

- Council for the Curriculum Examinations & Assessment. 2020b. “Relationships and Sexuality Education Guidance Council for the Curriculum, Examinations & Assessment”.

- Crossley, M., and K. Watson. 2009. “Comparative and International Education: Policy Transfer, Context Sensitivity and Professional Development.” Oxford Review of Education 35: 633–649.

- Croxford, L., and D. Raffe. 2014. “Social Class, Ethnicity and Access to Higher Education in the Four Countries of the UK: 1996–2010.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 33: 77–95.

- Dedering, K. 2009. “Evidence-Based Education Policy: Lip Service or Common Practice? Empirical Findings from Germany.” European Educational Research Journal 8: 484–496.

- Department for Education. 2015. Character Education Grant Application form and guidance. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education and Department of Health. 2015. Special Educational Needs and Disability Code of Practice: 0 to 25 Years: Statutory Guidance for Organisations Which Work with and Support Children and Young People Who have Special Educational Needs or Disabilities. London: Department for Education and Department of Health.

- Department for Education. 2016. Behaviour and Discipline in Schools: Advice for Headteachers and School Staff. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education. 2019a. Character Education Framework. London: Department for Education.

- Department for Education. 2019b. Relationships Education, Relationships and Sex Education (RSE) and Health Education. London: Department for Education.

- Department of Education, Northern Ireland Executive. 2005. Supplement to the Code of Practice on the Identification and Assessment of Special Educational Needs. Belfast: Northern Ireland Executive.

- Department of Health and Department for Education. 2017. Transforming Children and Young People’s Mental Health Services. London: Department of Health and Department for Education.

- Donnelly, M., and C. Evans. 2018. “A ‘Home-International’ Comparative Analysis of Widening Participation in UK Higher Education.” Higher Education 42: 1–18.

- Donnelly, M., and S. Gamsu. 2020. “Spatial Structures of Student Mobility: Social, Economic and Ethnic ‘Geometries of Power’.” Population, Space and Place 26: e2293.

- Elias, M. J., J. E. Zins, R. P. Weissberg, K. S. Frey, M. T. Greenberg, N. M. Haynes, R. Kessler, M. E. Schwab-Stone, and T. P. Shriver. 1997. Promoting Social and Emotional Learning: Guidelines for Educators. Alexandria, VA: Ascd.

- Hega, G. M. 2001. “Regional Identity, Language and Education Policy in Switzerland.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 31: 205–227.

- Kristjánsson, K. 2015. Aristotelian Character Education. New York: Routledge.

- Ladson-Billings, G. 2014. “Culturally Relevant Pedagogy 2.0: Aka the Remix.” Harvard Educational Review 84 (1): 74–84.

- Lareau, A. 2002. “Invisible Inequality: Social Class and Childrearing in Black Families and White Families.” American Sociological Review 67, 747–776.

- Logan, J. R., E. Minca, and S. Adar. 2012. “The Geography of Inequality: Why Separate Means Unequal in American Public Schools.” Sociology of Education 85: 287–301.

- Marsh, H. W. 2004. “Negative Effects of School-Average Achievement on Academic Self-Concept: A Comparison of the Big-Fish-Little-Pond Effect Across Australian States and Territories.” Australian Journal of Education 48: 5–26.

- Northern Ireland Executive. 2016. Children and Young People’s Strategy 2017-2027: Consultation Document. Belfast: Northern Ireland Executive.

- Raffe, D. 2005. Devolution in Practice II.

- Raffe, D., K. Brannen, L. Croxford, and C. Martin. 1999. “Comparing England, Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland: The Case For ‘home Internationals’ in Comparative Research.” Comparative Education 35: 9–25.

- Ryan, C., and L. Watson. 2006. “Why Does Year Twelve Retention Differ Between Australian States and Territories?” Australian Journal of Education 50: 203–219.

- Scottish Government. 2009. Curriculum for Excellence: Building the Curriculum 4: Skills for Learning, Skills for Life and Skills for Work. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2017. Getting it Right for Every Child (GIRFEC) Edinburgh. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Scottish Government. 2018. Developing a Positive Whole- School Ethos and Culture: Relationships, Learning and Behaviour. Edinburgh: Scottish Government.

- Stephens, W. B. 1999. Education in Britain, 1750–1914. London: Macmillan International Higher Education.

- Sturt, M. 2013. The Education of the People: A History of Primary Education in England and Wales in the Nineteenth Century. London: Routledge.

- Twenge, J. M. 2017. iGen: Why Today’s Super-Connected Kids Are Growing Up Less Rebellious, More Tolerant, Less Happy–and Completely Unprepared for Adulthood – and What That Means for the Rest of Us. New York: Simon and Schuster.

- Weare, K. 2010. “Mental Health and Social and Emotional Learning: Evidence, Principles, Tensions, Balances.” Advances in School Mental Health Promotion 3: 5–17.

- Welsh Assembly, Government. 2004. Special Education Needs Code of Practice for Wales. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government.

- Welsh Assembly Government. 2008. Education for Sustainable Development and Global Citizenship: A Common Understanding for Schools. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government.

- Welsh Assembly Government. 2010. Practical Approaches to Behaviour Management in the Classroom: A Handbook for Classroom Teachers in Secondary Schools. Cardiff: Welsh Assembly Government.

- Welsh Government. 2019. A Guide to Curriculum for Wales 2022. Cardiff: Welsh Government.

- Xiaomin, L., and E. Auld. 2020. “A Historical Perspective on the OECD’s ‘Humanitarian Turn’: PISA for Development and the Learning Framework 2030.” Comparative Education 56: 503–521.