ABSTRACT

In recent decades there has been an increasing number of parents opting for alternative forms of education worldwide. However, most studies on this phenomenon are conducted within Western contexts, while little is known about alternative education in China. This paper addresses this gap by providing an overview of alternative education in China over the past 20 years. This paper consists of four parts. First, we review the definition, categories, and development of alternative education in China. Second, we discuss three critical questions, namely (1) who is practising alternative education, (2) why do they choose alternative education, and (3) what is the legal status of alternative education in China? Subsequently, we develop a framework that enables us to situate different types of alternative education. Finally, we consider the phenomenon within a broader context and discuss the theoretical potential of further research into alternative education in China.

摘要

近几十年来,世界范围内有越来越多的家长选择另类教育。然而大部分针对这一现象的研究都是基于西方背景,对中国的另类教育知之甚少。本文通过回顾过去二十年中国另类教育的情况来填补这一空白。本文包含四个部分。第一部分概述另类教育在中国语境下的定义、类别和发展。第二部分讨论三个关键问题:(一)谁在践行另类教育?(二)他们为何选择另类教育?以及(三)另类教育在中国具有怎样的法律地位?接下来,我们搭建一个框架,使我们能够定位不同类型的另类教育。最后,我们从更宏观的背景下思考这一现象,并探讨进一步开展中国另类教育研究的潜在理论意义。

1. Introduction

In recent decades, there has been an increase in the types of education that parents choose for their children around the world (Plank and Sykes Citation2003). Besides various school choices within the public education system, alternative education that falls outside of state-provided mainstream education has become increasingly popular and has attracted more academic attention (Nagata Citation2007; Woods and Woods Citation2009; Kraftl Citation2013). According to Sliwka (Citation2008), alternative education refers to approaches of teaching and learning that are different from state-provided mainstream education. With a genealogical analysis, Nagata (Citation2007) traced the origin of alternative education to the new (progressive) educational movement that flourished in Europe and America during the 1920s, which was influenced and initiated by educational theorists and practitioners such as John Dewey, Rudolf Steiner, Maria Montessori, and A.S. Neill. According to Miller (Citation2002), such progressive educational claims regained their attractiveness in the 1960s and 1970s, which also contributed to the free school movement in the US. Different types of alternative education have been established in many Western contexts now, either by developing into informally organised learning centres, organic community-based private schools, or merging into mainstream educational systems and becoming public alternative schools (Miller Citation2002; Nagata Citation2007; Kraftl Citation2013). In recent years, alternative education has also gradually become a global phenomenon, gaining increasing popularity in non-Western countries, such as Japan, Korea, Thailand, and Sri Lanka (Nagata Citation2007).

More than forty years ago, Duke (Citation1978) made a sincere plea to pay more attention to the valuable insights that could be generated by studying ‘the unanticipated, the unusual, the atypical and the transient’ (68) with regards to the phenomena. He believed that alternative education is a good example of this. As the word ‘alternative’ connotes a separation from what is considered ‘mainstream’ (Kraftl Citation2013), a close examination of alternative education could help us to reflect on what exactly constitutes mainstream education, thus engaging in a ‘reflective practice’ (Woods and Woods Citation2009). Here, the dominant discourse and practices could be examined, and the future could be envisioned differently and creatively (Moss Citation2019). Compared with the plethora of studies in English-speaking countries, such as the US and the UK, scholarly investigation on alternative education in other contexts remains rather scarce. Recently, academic research has paid attention to alternative education in countries such as Poland (Starnawski and Gawlicz Citation2021), Chile (Leihy et al. Citation2017), Israel (Gofen and Blomqvist Citation2014), and Japan (Nagata Citation2016). However, little is known about the alternative forms of education in China, a country with one of the largest populations of school-aged children and the biggest educational markets in the world.

Against this background, this paper provides an overview of the development of alternative education in China and tries to situate the phenomenon in both global and domestic contexts. From the beginning of twenty-first century, different types of alternative education began to develop in China and several factors contributed to this. First, since the 1980s, the government began to promote the privatisation of education and private actors have been allowed to provide educational services to the public, which also encouraged people's enthusiasm to choose and even establish schools (Hannum, Park, and Cheng Citation2007). Meanwhile, accompanied by rapid economic development in China, there is an emerging middle-class group, which also has a growing demand for high-quality education (Crabb Citation2010). With the existence of high-stakes exams and entrenched meritocratic beliefs, education is always regarded as one of the fiercest battlefields for middle-class families in China (Willis Citation2020; Howlett Citation2021) and parents are always willing to spend a large amount of money on their children’s education (Lin Citation2019). At the same time, dissatisfaction with mainstream education also spread among the public. More and more parents started to reflect on how mainstream education was run and they regarded mainstream education as rigid and exam-oriented, which was harmful to children's well-being and the development of their creativity (Naftali Citation2010). All these factors gave rise to the diversified educational choices and development of alternative education in China in the past decades. However, currently, most alternative education still operates under an ambiguous legal status. As the emergence of multiple options outside of state-provided education may contradict the need for uniform education in an authoritarian country (Schulte Citation2018), the authorities are generally wary of educational practices that are developed outside of the mainstream educational system. Even within registered private schools, the curriculum, teaching, texts, and evaluation are still tightly controlled by the government (Wang and Chan Citation2015). Since most alternative education has not been registered and gained official recognition from the authorities, they still operate in the grey zone of the law. It is precisely this apparent paradox, whereby the middle class which is highly dependent on education in a country where state-sponsored education remains the most convenient way to success (Crabb Citation2010) opts for (expensive) alternative education, that renders it interesting to examine the development of alternative education and its potential social implications.

As alternative education in China is a relatively new and understudied phenomenon, this paper provides an overview and develops a typology of alternative education in China that can stimulate further studies in the area. The paper consists of four parts. Firstly, we review the definition, categories, and development of alternative education in China. Secondly, we discuss three critical questions, namely (1) who is practising alternative education, (2) why do they choose alternative education, and (3) what is the legal status of alternative education in China? Subsequently, we develop a framework that enables researchers to classify different types of alternative education in China. In a final step, we discuss both the similarities and differences of alternative education in China compared to the Western counterparts and also explore the theoretical potential of this phenomenon to deepen our understanding of social reproduction theories. We combine a variety of (data) sources. First, we searched for relevant studies (in both English and Chinese) on alternative education in China, including empirical studies, review articles and dissertations. Then, we collected relevant media coverage, books, interviews, and online lectures of the practitioners of alternative education in China. In addition, information from websites and promotional materials of some alternative schools are also used in the analyses. The first author conducted the data collection from September 2020 to June 2021.

2. ‘The road less travelled’: definition and typology

2.1. Defining alternative education

Currently, there is still no uniform definition of ‘alternative education’ in China (Wang Citation2020). Although the term ‘alternative education’(另类教育) is widely used in Taiwan (Feng Citation2006), it is often referred to as ‘outside of the system education’ (体制外教育) by practitioners in mainland China. The latter term is contrasted with state-regulated ‘within-system education’ (体制内教育), which includes public schools and registered private schools. Scholars also use ‘non-school experimental education’ (非学校型态实验教育) (Yuan and Liu Citation2014), and ‘innovative education’(创新教育) (Ma Citation2016; Hans Citation2021) to refer to this phenomenon. In 2013, a national seminar on ‘Home-schooling and Diversified Education’, hosted by the twenty-first Century Education Research Institute (an independent educational think tank in China), took place in Beijing and led to the ‘Beijing Consensus on Home-schooling’ (Citation2014). According to this consensus, educational initiatives outside of mainstream education are classified as ‘Chinese-styled home-schooling’, including ‘self-study at home’ (在家自学), ‘instruction by parents or recruited teachers at home’ (家长自行教授或者延师施教), ‘parent-organised micro-schools’(家长组织的微型学校) and ‘private academies’ (私塾) (Beijing Consensus Citation2014). Since then, researchers have also used ‘home-schooling’ to refer to various alternative educational practices across China (Ren Citation2015; Sheng Citation2018b, Citation2018c; Shao and Wang Citation2019).

These days, many alternative educational initiatives in China are simply not provided ‘at home’ but have become more public and adopted a well-organised form, which also renders it confusing to still refer to them as ‘home-schooling’. Thus, in this paper, we prefer to use the concept of ‘alternative education’ rather than ‘home-schooling’, referring to various educational initiatives that ‘fall outside of the traditional system’ (Sliwka Citation2008, 93). More specifically, these educational initiatives typically share three features. First, in contrast to government-led public schools, they are usually developed in a bottom-up manner and are promoted and subsidised by enthusiastic educators, individuals, and parents. Second, contrary to profit-oriented tutoring companies, which are typically utilised in tandem with standard educational trajectories, these ‘outside of the system’ initiatives provide full-time schooling for school-aged children, thus becoming a full-fledged alternative to state-run schools. Third, these schools usually adopt special types of curriculum, pedagogy, or evaluation, which are believed to satisfy children’s needs better than regular schools (Sliwka Citation2008; Nagata Citation2007). Considering the high heterogeneity within alternative education, we are fully aware of the difficulty in covering every detail of its development in China. Instead, in this paper, our discussion mainly focuses on home-schools (在家上学), Classics Reading schools (读经学校), Waldorf schools (华德福学校), Christian schools (教会学校), and Innovative schools (创新学校). These types of alternative education have reached a certain scale and have been previously covered in the media and prior research. This renders it possible to review them. In the next section, we describe the history and development of these five types of alternative education in China over the past 20 years.

2.2. History and development

During the past decades, a growing number of Chinese parents have sought alternative pathways for their children. Five types of alternative education can be distinguished.

2.2.1. Home-schooling (在家上学)

Home-schooling, defined here as education that is effectively provided at home, began to emerge in China during the turn of the century (Sheng Citation2018b, Citation2018c). In recent years, this phenomenon has become more well-known among the public due to increased media attention of famous home-school cases. Two of such cases are Yuan Honglin (Chen Citation2008) and Zhang Qiaofeng (Zhou Citation2014). Both fathers have a strong academic background and decided to teach their children at home. They shared their experiences online, garnering much public attention (Chen Citation2008; Zhou Citation2014). Alongside these well-known cases, there are more families practising home-schooling discreetly. Researchers estimate that there were approximately 6,000 families who practised home-schooling in China in 2018 and that this group grows at an annual rate of 30% (Wang, Wang, and Wu Citation2018). In home-schooling families, children are either taught by their parents or study by themselves (which are usually older students), thus they have great flexibility and autonomy over the curriculum, teaching content, learning speed, and evaluation format (Sheng Citation2018b, Citation2018c). While some still follow the official school curriculum, others may follow alternative curricula that satisfy their educational needs.

2.2.2. Waldorf school (华德福学校)

The development of Waldorf education reflects the growing influence of Western pedagogies in China. Fed up with mainstream schools, some Chinese parents began to opt for Western-style education such as Waldorf, Montessori, and Regio (Walker Citation2015). Among these, Waldorf education is the most influential (Wu Citation2013). As a worldwide phenomenon, Waldorf education is based on the anthroposophy theory founded by Rudolf Steiner which originated in Germany (Ashley Citation2009). Following its special understanding of children’s development and education, Waldorf education emphasises ‘spirituality’ through the balanced development of body and mind and promotes the holistic development of children (Ashley Citation2009). The first Waldorf school in China was established in Chengdu, a southwest city, by a couple, Li, and his wife Zhang (Bai Citation2015). After receiving training on Waldorf education in the UK, they established the school in 2004 (Bai Citation2015). Since then, this school has grown into a big community with more than 500 families and provides education from kindergarten to high school (Sun Citation2020). Meanwhile, Waldorf schools have also been established in many other cities, such as Beijing, Shanghai, and Shenzhen, becoming increasingly popular among Chinese parents. Chinese practitioners keep in close contact with their international counterparts in terms of the educational philosophies and curriculum. At the same time, however, some schools incorporate elements of (traditional) Chinese culture into their curriculum, such as traditional lunar ceremonies and Chinese calligraphy. By the end of 2019, there were more than 70 primary Waldorf schools, 400 kindergartens, and 5 teacher training centres across China (Ma Citation2020).

2.2.3. Classics Reading school (读经学校)

Different from Waldorf schools, the development of Classics Reading schools is shaped by mixed influences of indigenous culture. Since the end of the last century, the Chinese government has issued a series of policies to promote the recovery and inheritance of traditional Chinese culture, as an integral part of the national project to reclaim cultural confidence and national rejuvenation (Yu Citation2008; Wang Citation2022). At the same time, a massive ‘popular Confucianism movement’ was initiated by individuals who had regained interest in the spiritual and healing dimensions of traditional culture (Billioud and Thoraval Citation2015). Despite the seeming synchronicity, the establishment of Classics Reading Schools is ‘never a top-down policy’ (74), but rather an important embodiment of the ‘popular Confucianism movement’, thus carrying some bottom-up features (Billioud and Thoraval Citation2015). Inspired by a Taiwanese scholar Wang Caigui, an enthusiastic advocator of the Classics Reading Movement (读经运动), hundreds of Classics Reading schools have been established by enthusiastic individuals across mainland China and some parents also regard it as a better alternative to mainstream public schools (Bao Citation2019). Instead of learning the official curriculum issued by the Chinese Ministry of Education, students in Classics Reading schools spend a large amount of time reading and memorising ancient Chinese Classics. The inherent tensions and divisions between Classics Reading Schools and the official agenda became apparent in the later stage of the movement, which sometimes lead to conflict. The Mengmu Tang case happened in 2006 is an example (Li Citation2010; Sheng Citation2015). As an unauthorised Confucian Classics Reading school started by local parents in Shanghai, this school was finally ordered to close after several rounds of negotiations between the participants and the local authorities. Estimates indicate that approximately 10 million children attended Confucian kindergartens, classes, and schools in 2014 (Pang Citation2015). A recent survey demonstrated that, by 2018, there were more than 2,000 Classics Reading schools across China (Bao Citation2019). Recently, because of the more severe policies issued by authorities, many Classics Reading schools have been banned and closed, while others have gone underground and operated secretly.

2.2.4. Christian school (教会学校)

Recently, Christian education in China has also attracted scholarly attention (De Silva, Woods, and Kong Citation2020; Yuan Citation2021). Since the 2000s, some devout Christian parents have withdrawn their children from public schools due to dissatisfaction with state-sponsored ‘atheistic’ education and a desire to transfer religious beliefs onto their children (Sheng Citation2018b; Yuan Citation2021). While some parents chose to practise Christian home-schooling (Sheng Citation2018b), others sent their children to unlicensed Christian K-12 schools (De Silva, Woods, and Kong Citation2020; Yuan Citation2021). The development of Christian schools is closely related to the spread of unregistered ‘urban house churches’ (城市家庭教会) (Yuan Citation2021). In China, religious activities are strictly restricted to registered religious institutions (Sun Citation2017). However, initiated by individual Christian believers, these ‘urban house churches’ have no affiliations to officially approved institutions and thus operate under an uncertain legal status (Koesel Citation2013). Some unlicensed Christian schools are organised by and operate within these ‘urban house churches’ (De Silva, Woods, and Kong Citation2020; Yuan Citation2021). Teaching in Christian schools usually combines Bible studies with regular courses, such as mathematics, English, science, and social studies (Chen Citation2012). Due to the underground nature of these schools, it is difficult to arrive at a reliable estimate of the number of Christian schools in China. According to Sheng’s estimation (Citation2018b), there are around 5,000 home-educated Christian children in mainland China. Meanwhile, based on a regional media report, there are dozens of Christian schools located in big cities, such as Beijing and Guangzhou (Chen Citation2012).

2.2.5. Innovative school (创新学校)

In contrast to the former types of alternative education, ‘Innovative schools’ appear to be more heterogeneous. Emerging over the last decade, the Innovative schools pertain to bottom-up educational initiatives that are typically small-scale, with a high teacher-student ratio, and the aim to facilitate individualised learning (Ma Citation2016; Yang Citation2018; Hans Citation2021). Most Innovative schools adopt humanistic educational beliefs that contrast with the utilitarian and competitive educational environment encouraged in mainstream education. While some schools are inspired by old educational philosophies, others find their educational models in state-of-the-art international educational innovations. For example, the Cangshan School, established by a former journalist in 2011, follows the philosophies of the Summerhill School (Li Citation2012). The school was originally located in Dali, a tourist city in the southwest of China. Instead of emphasising a traditional curriculum as taught in mainstream schools, teaching in the Cangshan School is more life- and nature-orientated. Students are expected to learn in a natural environment and spend much of their time on international and domestic tours rather than in classroom learning (Li Citation2012). The Etu school is another famous example. Following the prototype of the AltSchool (Horn Citation2015, Citation2016), it was established in 2016 by a middle-class mother, Li Yinuo, who failed to find a satisfactory school in Beijing for her children (Yuan Citation2016). Since its establishment, the school professes to promote individualised teaching that satisfies children’s needs (Yuan Citation2016). In a national survey in 2017, Yang (Citation2018) identified 27 Innovative schools in China. Although we have no accurate number at present, according to media reports, this type of school seems to be becoming increasingly attractive in urban areas, such as Beijing and Chengdu, especially among upper-middle class parents (Hans Citation2021).

3. ‘Disembarking from the Titanic’: stories behind alternative choices

3.1. Profile of practitioners in alternative education

After having discussed different forms of alternative education in China, a key question concerns exactly who is practising alternative education. According to recent studies, practitioners of alternative education are usually urban citizens, holding bachelor’s degrees and above, with a stable household income (Wang, Wang, and Wu Citation2018; Yang Citation2018; Sun Citation2020). An indication of the social background of participant families can also be derived from the amount of money parents pay for their children’s education. shows the estimated tuition fees of types of alternative schools in China that has been collated from previous research or media reports.

Table 1. The Estimated Tuition Fee of Different Types of Alternative Schools.

China is a large country with large disparities in economic development, so some caution is warranted when interpreting these numbers, but two observations stand out. First, as expected, varying from a few thousand to hundreds of thousands RMB per year, the tuition fees for alternative schools seem rather high when compared with state-run public schools, which are almost free during the Compulsory Education phase (Grades 1-9). According to data from the NBS (Citation2021), the national disposable income per capita in China was only 32,000 RMB in 2020. Seen from this perspective, attending alternative education only seems to be an option for the wealthier segments of the Chinese population. Second, there is great variation in the tuition fees of different types of alternative schools. For example, the tuition fees for Innovative schools are nearly six times (100 thousand RMB) higher than that of Christian schools (15-17 thousand RMB). This difference can be partly explained by the geographical distribution of different types of alternative schools, but it may also indicate heterogeneity across the distinct types of alternative education.

3.2. Reasons for choosing alternative education

Heterogeneity can also be found in the parents’ motivations for choosing alternative education. Most parents choose alternative education due to dissatisfaction with mainstream schools. In general, parents’ complaints about mainstream education include (1) the rigid and exam-orientated teaching method (Ren Citation2015; Yang Citation2018); (2) unhealthy competition and the heavy burden on students (Ren Citation2015; Sun Citation2020); (3) the impersonal relationship between teacher and parents (Ren Citation2015; Yang Citation2018); and (4) the utilitarian and instrumental educational beliefs (Sun Citation2020). In contrast, alternative education is considered to create a healthy environment for children’s growth and to promote their holistic development (Ren Citation2015; Yang Citation2018; Sun Citation2020). Interestingly, some alternative schools were initially established by parents for the sake of their own children’s education. The Ririxin school, for example, was established by a couple in Beijing. Heartbroken over the struggles their eldest daughter experienced in a mainstream school, they decided to teach their younger daughter in an alternative way and finally developed a school to achieve this in 2006 (Li Citation2012). Similar stories exist for other initiatives, such as the Etu School (Yuan Citation2016) and the Cangshan School (Li Citation2012).

Meanwhile, Bao (Citation2019) observed that some parents regard Classics Reading schools as an option for their children who did not adapt to or felt marginalised at mainstream school. Li (Citation2021) also found that the self-organised alternative schools provided a sense of community to parents who were distressed by their children’s ‘problematic performance’ (Li Citation2021). In such cases, choosing alternative schools becomes a journey to ‘heal trauma’ and ‘reclaim control over their lives’ for marginalised parents and children, which can sometimes also suggest an alternative view of education and life (De Silva, Woods, and Kong Citation2020). In addition, ideological/religious reasons also contribute to parents’ alternative education choices. Bao (Citation2019) found that some parents send their children to Classics Reading schools out of their own beliefs on the value of traditional culture and their willingness to instil traditional culture in their children. Similar cases are also found for Christian education. Choosing underground Christian schools serves as a reaction against the ‘atheistic’ education prominent in mainstream schools by parents who want to pass on their religious beliefs and cultivate their children into devout believers (Yuan Citation2021).

3.3. Ambiguous legal status: negotiation and survival

Although alternative education seems to attract increasing attention from the public in China, questions still remain regarding their current legal status. In China, compulsory education covers primary school to junior school (G1-G9). According to China’s Compulsory Education Law, parents are obliged to send their school-aged children (6-15 years old) to school (Sheng Citation2018a). Thus, teaching school-aged children at home appears to violate the law (Sheng Citation2018a). As alternative schools receive no funding from the government, they are generally considered to be private schools. According to the current educational legislation, private schools in China should apply for a school license (办学许可证) (a certificate issued by the local educational authority), which ensures their legal status for operation. However, currently most alternative schools find it challenging to attain legal status for two reasons. First, although the policy varies according to region, the criteria for applying for a school license, such as the number of students (e.g. at least 500) and campus facilities (e.g. with standard sports field and science laboratories), are usually difficult to meet. Most alternative educational initiatives are small-scale and housed within temporary residential locations, thus making it difficult for them to meet all these criteria. Second, and more importantly, registering as a private school implies allowing regular evaluation and inspection by the local government. This would undermine the autonomy of alternative schools in terms of their curriculum and daily operations (Wang and Chan Citation2015). For this reason, some alternative schools are registered as educational companies or non-profit social organisations (Wang Citation2020), while others give up seeking recognition from the government and operate underground.

Interestingly, although most alternative schools have not gained legal status, they still manage to survive and even grow in this grey zone of operation. Some schools even have their own websites that facilitate the public recruitment of prospective students. Indeed, sometimes, the local government shows an acquiescent attitude towards alternative education (Luo, Wang, and Fu Citation2016). Also, the context of educational governance plays a role. With the decentralisation of educational governance since the 1980s, the supervision and controlling of private schools has become strongly context-dependent (Schulte Citation2017). Hence, authorities in different regions may show varying degrees of tolerance to alternative education, thus leaving them a way to survive. The great irony of this is that these local differences further enhance the already ambiguous status of alternative education in China.

4. Towards a new typology of alternative education in China

In the analysis above, we have illustrated different types of alternative education in China. Instead of providing a unified picture, we have shed light on the heterogeneity within these categories and the particularities of the Chinese context. To grasp the dynamics within each type and the variations among them, in this section we develop a typology of alternative education in China based on a discussion of their main features.

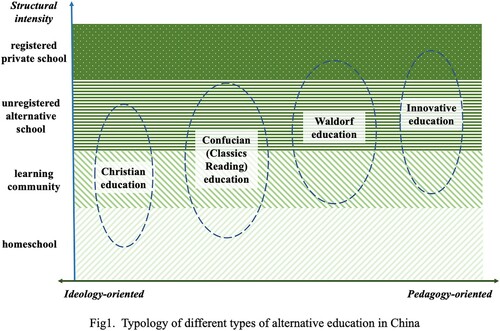

Within the overarching category of alternative education, the types of education that we have discussed so far vary a lot in terms of their scale, organisational form, and modalities. This is further complicated by the fact that, in reality, some schools combine multiple forms. Christian education, for example, could either be operated as Christian home-schooling (Sheng Citation2018b) or as unlicensed Christian schools (De Silva, Woods, and Kong Citation2020; Yuan Citation2021). Moreover, the same organisation may also evolve over time. For example, some alternative schools may start as home-schooling or small-scale initiatives with only a few families but undergo substantial development when more families join in and even grow into a registered private school upon attaining a school license from the government. By studying the history of the home-schooling movement in the US, Gaither (Citation2008) found a ‘hybridizing’ process during which ‘home-schoolers are increasingly creating hybrids that blend elements of formal schooling into the usual pattern of a mother teaching her own biological children at home’ (264). In this way, different types of hybrids have emerged that vary in terms of scale, structural intensity, and formality, which include ‘mom school’, ‘home-school cooperative’, ‘self-directed learning centres’ and even ‘cybercharter schools’ (Gaither Citation2008, 211). Interestingly, similar dynamics can also be found in the development of alternative education in China. Inspired by this, we can also situate different forms of alternative education in China on a spectrum according to their structural intensity, ranging from home-schools, learning communities, and unlicensed alternative schools, to licensed private schools.

Although parents’ motivations for choosing alternative education vary, some basic categories can be identified. For example, while Classics Reading schools and Christian schools seem to be organised around particular ideological/religious beliefs (i.e. Confucianism or Christian beliefs) (Bao Citation2019; Yuan Citation2021), Innovative schools usually pay more attention to daily teaching and pedagogies (Ren Citation2015; Yang Citation2018). Such differences are reminiscent of what Van Galen (Citation1988, Citation1991) classed as ‘ideologues’ and ‘pedagogues’ during an analysis of parents’ motivations for home-schooling. According to Van Galen (Citation1991), while ‘ideologues’ refers to parents who ‘have specific values, beliefs and skills that they want to their children to learn’ during home-schooling (67), ‘pedagogues’ decide to teach their children at home because they think that ‘schools teach whatever they teach ineptly’ (71). This classification is further confirmed and expanded by Stevens (Citation2002) who found two distinct groups in the American home-schooling movement and thus named them as ‘the believers’ and ‘the inclusives’. The categories represent two forces in the home-schooling movement with quite different understandings about childhood, attitudes towards to the educational authorities and different organisational models as well as final outcomes (Stevens Citation2002). It is possible to situate different types of alternative education in China along this classification. However, in practice, the two categories may intertwine as some parents have reported being driven by both ideological and pedagogic reasons (Sheng Citation2018b; Bao Citation2019). Thus, instead of taking them as clearly distinct categories, we consider the two categories as being positioned at opposite ends of a continuum. In this way, while Classics Reading schools and Christian schools are located further along the side of ‘ideology-orientation’, in contrast, Innovative education is located further to the side reflecting pedagogic enthusiasm (Van Galen Citation1991). As Waldorf education is based on a fixed educational ideology (Steiner education) and develops its own curriculum and pedagogy (Ashley Citation2009), we situate it in the middle of this continuum.

Based on the preceding arguments, we have developed a typology and re-organised the different types of alternative education in China as shown in .

The horizontal axis represents their orientation, and the vertical axis indicates the structural intensity of educational initiatives. In terms of educational orientation, we rely on the categories varying from ‘ideologues’ to ‘pedagogues’ (Van Galen Citation1988, Citation1991). For structural intensity, we situate different types of alternative education on the spectrum varying from home-school, learning community, unregistered alternative schools, and registered private schools. We draw the boundary for each alternative education with dashed lines to reflect potential empirical variations within each type and possible overlaps among them. Combining different elements and situating different types of alternative education in this typology can help us to get a better understanding of the differences and similarities between the various types of alternative education in China and lay a foundation for further comparison.

5. Discussion and conclusion

The preceding arguments provide an overview of the development of alternative education in China over the past 20 years. In this section, we try to use these descriptive elements to develop a deeper analytical discussion of alternative education in China and, more specifically, explain how studying this phenomenon can advance existing theoretical debates. We organise this discussion around two topics.

5.1. Situating Chinese alternative education in a broader context

As mentioned before, the alternative education movement finds its origins in Western countries, such as the US and the UK, where many alternative educational philosophies and models have been established. The development of alternative education in China is clearly influenced by these Western trends. For example, Waldorf education originated in Europe, but it has become one of the important alternative school choices for Chinese parents (Walker Citation2015). However, as pointed out by Nagata (Citation2007), the development of alternative education in Asia cannot be understood as an influence from the West to the non-West as indigenous culture also plays an important role (Nagata Citation2007). For example, in our study we also identified one type of alternative education that is quite indigenous to China, i.e. Classics Reading schools, which are heavily rooted in traditional Chinese culture. Meanwhile, the local context also plays an important role in shaping the development of alternative education. For example, while Christian schools are legally allowed in most Western contexts, it is an underground option in this context due to the strict governance of religious education in China.

More interestingly, we have detected a type of alternative education in China that seems, in a number of ways, distinctive to China, namely (parent-initiated) Innovative schools. This type of alternative education is intriguing for several reasons. First, as a school type related to ‘pedagogues’, they do not attach themselves to particular ideologies or creeds but pay more attention to innovations in teaching and learning. Instead of isolating themselves from mainstream schools, they try to connect with mainstream education in many ways (e.g. actively applying for school licenses from local authorities, combining official curriculums into their teaching). As the mission statement of one Innovative school expresses in their promotional materials: ‘we want to be the mainstream in the nonmainstream education’ (Agilearning Centre Citation2019). Further, although most alternative education has an ambiguous legal status, a number of Innovative schools have been reported and praised by official media (e.g. see Liu Citation2017) and several schools have even gained school licenses from the government (e.g. the Ririxin school).

Thus, we believe that further investigation of Innovative schools can generate valuable insights. Our findings also lead to three crucial questions that provide the starting point for further research. First, by maintaining a ‘pragmatic relationship with the mainstream education and the government’ (Woods and Woods Citation2009, 229), Innovative schools seem to adopt an ‘engagement’ strategy, which may also sometimes indicate a compromise. At the same time, as a form of parental entrepreneurship (Gofen and Blomqvist Citation2014), which is heavily dependent on the parents’ sponsorship, these schools have to emphasise their uniqueness and superiority in order to attract potential families. This raises the question as to how Innovative schools negotiate their ‘alternativity’ and attract prospective families while dealing with pressure from authorities. Second, according to Woods and Woods (Citation2009), there is a fluid boundary between ‘being alternative’ and ‘being oppositional’. This draws attention to the potential social implications of this phenomenon: will it grow and even reform the education system, or only act as an ‘alleviating measure with an expiration date (Schulte Citation2018)? Our third question concerns the consistency between ideals and practices. Bearing in mind their highly promoted humanistic educational claims, we could examine the extent to which it is possible to put it in to practice and create such educational environments in a society that places such a strong emphasis on tests, competition, and standardisation (Shuter Citation1973).

5.2. Revisiting social reproduction theories for alternative education in China

Currently, it is still debated whether alternative education contributes to potential social inequality. From an optimistic perspective, alternative education is sometimes depicted as a type of practice with democratic participation and even the potential to transform education and society. For example, according to Woods and Woods (Citation2009), alternative education ‘challenges visions of humankind’s potentiality and how society can and should be changed’ (228), whilst embodying the types of social action that is oriented towards ultimate values rather than instrumental rationality. Moss (Citation2019) also holds that alternative education may provide a new paradigm that helps to transcend the dominant neoliberal discourses and shatter the ‘dictatorship of no alternative’ (Unger Citation2005). But such optimism sometimes is met with criticism for their alleged ignorance of the specific historical and social context where these alternative types of education are rooted. For example, Bowles and Gintis (Citation2011) have criticised how the free school movement failed to contribute to a more free and equal society, as it ignores the oppressive factors outside of the educational system. Furthermore, some empirical studies also revealed how alternative education instils students with neoliberal discourses of self-motivation, entrepreneurship and individualistic notions of success and contribute to social inequality (Starnawski and Gawlicz Citation2021; Wilson Citation2016). Considering the relevantly expensive tuition fees, access to alternative education is only limited to a segment of people in China. Like their Western counterparts, Chinese middle-class parents have the capacity to mobilise multiple sources of capital to provide their children with a safety net even when they do not gain academic success as expected (Chiang Citation2018). This may be the case with parents who choose alternative education.

However, caution is still warranted when we try to explain alternative education in China from a social reproduction perspective. Considering the apparent separation from the mainstream education and the ambiguous legal status, opting for alternative education in China seems to be risky at least in two senses. Most alternative education adopts a quite different curriculum from mainstream education and rather laid-back learning styles. This implies that students from alternative schools may have few advantages in a competitive exam-oriented educational system, especially compared with their peers in mainstream schools. Moreover, by enrolling their children in a type of alternative education with an ambiguous legal status, they may also indicate a noncompliance and even engage in a resistant activity against the authority, leading to potential political risks. This also involves the ‘politics of refusal’ put forward by Ball (Citation2015), which may implant in them a deep feeling of uncertainty, unsettledness, and even expose them to censure, ridicule, and marginalisation. Thus, these potential tensions and contradictions render it difficult to take alternative educational choices only as a new strategy that enables advantaged groups to transmit their social position (and hence reproduce existing social inequalities). More explanations are needed to reveal what motivate these Chinese middle-class parents to take such against-the-grain initiatives and what types of capital or advantages they are gaining from engaging into such activities.

In addition, an eager embrace of the social reproduction model may also blur the difference between social reproduction as a type of ‘calculated pursuit’ or as a ‘unintended outcome’. While social reproduction might be a plausible explanation here, it provides us little clue about how and why these middle-class parents make such choices. Privileges and social reproduction are not only a social outcome, but also a dynamic process that requires continuous negotiation (Minarik Citation2017). Thus, it is more important to know how these Chinese middle-class parents account for the logic lying behind their alternative practices and how their reasoning fits into the narratives about their life stories. To achieve this, it may be better for us to loosen our tight grip on the dominant educational discourses that are centred around calculation, economic returns, investment, and rather seek for new and possible cultural frameworks for interpretation. In this case, educational choices may also be understood as an alternative perspective on learning and love (Kraftl Citation2013), a moral vision focusing on the authenticity and meaning of life (Miller Citation2002), and a pursuit of better life that go beyond cultural accumulation strategies (Kardaszewicz Citation2019). Along this way, it may provide us a new lens to understand how these Chinese individuals develop and negotiate their desire, hope and self-identity in a highly-speed modernised context (Willis Citation2020).

As one father put it, ‘if the current educational system is a Titanic, we are the people who choose to disembark in advance’ (Wu Citation2012). However, the destiny of the small boat they have chosen depends not only on where they anchor their enterprise, but also on how calm the waters are. Considering the current social context in China, what will happen after their departure is still surrounded by uncertainty. Thus, further academic efforts are needed to reveal the dynamics underlying these practices and their social implications.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Wanru Xu

Wanru Xu is a PhD student at the Sociology Department of Vrije Universiteit Brussel. Her research interest is alternative education, middle-class involvement in education, and educational development in China. E-mail: [email protected]

Bram Spruyt

Bram Spruyt is associate professor of Sociology at Vrije Universiteit Brussel. His main research interests include public opinion research, youth research, sociology of education and cultural sociology. E-mail: [email protected]

References

- Agilearning Centre. 2019. “招生说明会| 爱哲学校中心招募30个家庭,为未来而学 [Admissions Briefing | Agilearning Centre Recruits 30 Families to Learn for the Future].” July 11. Accessed 27 August 2021. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/vj1cpiyd7NIebK4pO_o60w.

- Ashley, M. 2009. “Education for Freedom: The Goal of Steiner/Waldorf Schools.” In Alternative Education for the 21st Century: Philosophies, Approaches, Visions, edited by P. Woods, and G. Woods, 227–248. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Bai, Y. J. 2015. “华德福七年光与影 [Light and Shadow of Waldorf Education in China in Seven Years].” Baijuan. July 17. Accessed 27 August 2021. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/80LZKZyYfl4kmsDkSh6gVA.

- Ball, S. J. 2015. “Subjectivity as A Site of Struggle: Refusing Neoliberalism.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 37 (8): 1129–1146.

- Bao, L. G. 2019. “民间教育机构的传统文化教育探索[Exploration of Traditional Culture Education in Non-governmental Education Institutions].” In 中国传统文化教育发展报告 [Report on the Development of Traditional Culture Education in Contemporary China], edited by D. P. Yang, H. Q. Liu, and L. G. Bao, 120–150. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press.

- “Beijing Consensus on ‘Homeschooling’ [中国‘在家上学’北京共识].”. 2014. “ 中国教育发展报告2014 [Annual Report on China's Education in 2014].” In edited by D. P. Yang, 295–296. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press.

- Billioud, S., and J. Thoraval. 2015. The Sage and the People: The Confucian Revival in China. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Bowles, S., and H. Gintis. 2011. Schooling in Capitalist America: Educational Reform and the Contradictions of Economic Life. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

- Chen, S. Y. 2008. “博士父亲自家开私塾 九岁女儿当老师讲古文 [A Father with PhD Degree Opened His Own Private School and His Nine-year-old Daughter Taught Ancient Chinese as a Teacher].” 今日早报 [Morning Express]. August 11. Accessed 28 July 2021. http://news.sohu.com/20080811/n258745722.shtml

- Chen, L. 2012. “Underground Godly Education.” Global Times. April 25, Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.globaltimes.cn/content/706670.shtml

- Chiang, Y. L. 2018. “When Things Don’t Go as Planned: Contingencies, Cultural Capital, and Parental Involvement for Elite University Admission in China.” Comparative Education Review 62 (4): 503–521.

- Crabb, M. W. 2010. “Governing the Middle-class Family in Urban China: Educational Reform and Questions of Choice.” Economy and Society 39 (3): 385–402.

- De Silva, M., O. Woods, and L. Kong. 2020. “Alternative Education Spaces and Pathways: Insights from an International Christian School in China.” Area 52 (4): 750–757.

- Duke, D. L. 1978. “Investigating Unanticipated Educational Phenomena: A Special Plea for More Research on Alternative Education.” Interchange 10 (1): 67–81.

- Feng, Z. L. 2006. “另類教育與二(十)一世紀教育改革趨勢 [Alternative Education and the Trend of Educational Reform in the 21st century].” 研習資訊 23 (3): 5–12.

- Gaither, M. 2008. Homeschool: An American History. New York: Palgrave.

- Gofen, A., and P. Blomqvist. 2014. “Parental Entrepreneurship in Public Education: a Social Force or a Policy Problem?” Journal of Education Policy 29 (4): 546–569.

- Hannum, E., A. Park, and K.-M. Cheng. 2007. “Market Reforms and Educational Opportunity in China.” In Education and Reform in China, edited by E. Hannum, and A. Park, 1–25. London: Routledge.

- Hans. 2021. “关停、争议、新建,中国创新学校的不同命运曲线 [Shutdown, Controversy, New Establishment, the Curves of Different Fate of China's Innovative Schools].” 新学说 [NewSchool Insight]. February 5. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/GUK7dPSpnK_8FcnpnGmeIg.

- Horn, M. B. 2015. “The Rise of Micro-schools: Combinations of Private, Blended, and at-home Schooling Meet the Needs of Individual Students.” Education Next 15 (3): 77–79.

- Horn, M. B. 2016. “The Rise of AltSchools and Other Micro-Schools.” The Education Digest 81 (6): 28.

- Howlett, Z. M. 2021. Meritocracy and Its Discontents: Anxiety and the National College Entrance Exam in China. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Kardaszewicz, K. 2019. “New Rules of the Game? Education and Governmentality in Chinese Migration to Poland.” Asian and Pacific Migration Journal 28 (3): 353–376.

- Koesel, K. J. 2013. “The Rise of a Chinese House Church: The Organizational Weapon.” The China Quarterly 215: 572–589.

- Kraftl, P. 2013. Geographies of Alternative Education: Diverse Learning Spaces for Children and Young People. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Leihy, P., H. A. Martini, P. C. Armijo, and J. S. Fernandez. 2017. “Evolution in Freedom? The Meanings of ‘Free School’ in Chile.” British Journal of Educational Studies 65 (3): 369–384.

- Li, Y. G. 2010. “私塾这些年 [The Development of Confucian Schools].” 儒家网 [Confucianism Website]. March 7. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.rujiazg.com/article/523.

- Li, X. L. 2012. 在家上学: 叛离学校的教育 [Homeschooling: Education Away from School]. Beijing: China Open University Press.

- Li, X. S. 2021. “How Old-school Parenting is Holding Back Alternative Education.” Sixth Tone. April 9. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.sixthtone.com/news/1007116/how-old-school-parenting-is-holding-back-alternative-education.

- Lin, X. S. 2019. “‘Purchasing hope’: the Consumption of Children’s Education in Urban China.” The Journal of Chinese Sociology 6 (1): 1–26.

- Liu, W. 2017. “小微学校:尝试“玩”的教育[Micro-school: Education Centred on ‘Playing’].” Xinhua News Agency. May 13. Accessed 27 March 2021. https://mp.weixin.qq.com/s/W5rbH6K1b2NPPaeSVt146A.

- Luo, T., T. T. Wang, and Z. Y. Fu. 2016. “读经少年圣贤梦碎:反体制教育的残酷试验与读经教主王财贵的产业链条 [The Broken Dreams of Becoming Sages: The Cruel Experiment of Anti-system Education and the Industrial Chain of the Wang Caigui].” 新京报 [The Beijing News]. August 29. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.sohu.com/a/112607130_362353.

- Ma, Z. J. 2016. “民间教育创新的实践探索及分析 [Analysis on the Exploration of Innovative Practice of Private Education].” In 中国教育发展报告2016 [Annual Report on China's Education 2016], edited by D. P. Yang, 142–155. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press.

- Ma, Q. P. 2020. “对话张俐:华德福教育中国本土化15年 [Dialogue with Zhang Li: Localization of Waldorf education in China Over the Past 15 Years].” J Media. January 13. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.jiemian.com/article/3869734.html.

- Miller, R. 2002. Free Schools, Free People: Education and Democracy after the 1960s. Albany: State University of New York Press.

- Minarik, J. D. 2017. “Privilege as Privileging: Making the Dynamic and Complex Nature of Privilege and Marginalization Accessible.” Journal of Social Work Education 53 (1): 52–65.

- Moss, P. 2019. Alternative Narratives in Early Childhood: An Introduction for Students and Practitioners. New York: Routledge.

- Naftali, O. 2010. “Recovering Childhood: Play, Pedagogy, and the Rise of Psychological Knowledge in Contemporary Urban China.” Modern China 36 (6): 589–616.

- Nagata, Y. 2007. Alternative Education: Global Perspectives Relevant to the Asia-Pacific Region. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Nagata, Y. 2016. “Fostering Alternative Education in Society: The Caring Communities of “Children’s Dream Park” and “Free Space En” in Japan.” In The Palgrave International Handbook of Alternative Education, edited by H. E. Lees, and N. Noddings, 241–256. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- NBS [National Bureau of Statistics of China]. 2021. “2020年居民收入和消费支出情况 [National Residents' Income and Consumption Expenditures in 2020].” January 18. Accessed 28 July 2021. http://www.stats.gov.cn/tjsj/zxfb/202101/t20210118_1812425.html.

- Pang, E. 2015. “Learning Curves: Alternative Education in China.” eChinacities.com. March 25. Accessed 28 July. http://www.echinacities.com/expat-corner/Learning-Curves-Alternative-Education-in-China.

- Plank, D. N., and G. Sykes. eds. 2003. Choosing Choice: School Choice in International Perspective. New York: Teachers College Press.

- Ren, J. H. 2015. “体制外守望:中国式‘在家上学’的教育困境——基于北京R学堂的个案研究[Keeping Watching Outside the System: the Educational Predicament of Chinese-styled Homeschooling: a Case Study of R School in Beijing].” 民族教育研究 [Journal of Research on Education for Ethnic Minorities] 05: 110–117.

- Schulte, B. 2017. “Private Schools in the People's Republic of China: Development, Modalities, and Contradictions.” In Private Schools and School Choice in Compulsory Education: Global Change and National Challenge, edited by T. Koinzer, R. Nikolai, and F. Waldow, 115–131. Wiesbaden: Springer.

- Schulte, B. 2018. “Allies and competitors: Private Schools and the State in China.” In The State, Business and Education: Public-private Partnerships Revisited, edited by G. Steiner-Khamsi, and A. Draxler, 68–84. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing.

- Shao, Y., and X. Y. Wang. 2019. “峥峥为何会去悦习园?——基于Y市华德福家长的个案研究 [Why Did Zhengzheng Go to Yuexiyuan? Case Study of a Waldorf Mother in the City Y].” 全球教育展望 [Global Education] 048 (011): 42–58.

- Sheng, X. M. 2015. “Confucian Work and Homeschooling: A Case Study of Homeschooling in Shanghai.” Education and Urban Society 47 (3): 344–360.

- Sheng, X. M. 2018a. “Home Education and Law in China.” Education and Urban Society 50 (6): 575–592.

- Sheng, X. M. 2018b. “Christian Homeschooling in China.” British Journal of Religious Education 41 (2): 218–231.

- Sheng, X. M. 2018c. “Confucian Home Education in China.” Educational Review 71 (6): 712–729.

- Shuter, R. 1973. “Free-school norms: A case study in external influence on internal group development.” The Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 9 (2-3): 281–293.

- Sliwka, A. 2008. “The Contribution of Alternative Education.” In Innovating to Learn, Learning to Innovate, edited by OECD, 93–112. Paris: OECD Publishing. Accessed August 27, 2021. https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/innovatingtolearnlearningtoinnovate.htm.

- Starnawski, M., and K. Gawlicz. 2021. “Parental Choice, Collective Identity and Neoliberalism in Alternative Education: New Free Democratic Schools in Poland.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 42 (8): 1172–1191.

- Stevens, M. 2002. Kingdom of children: Culture and Controversy in the Homeschooling Movement. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Sun, Y. 2017. “The Rise of Protestantism in Post-Mao China: State and Religion in Historical Perspective.” American Journal of Sociology 122 (6): 1664–1725.

- Sun, Y. F. 2020. “An Ethnographic Study of ‘Steiner Fever’ in China: Why are Chinese Parents Turning away from Mainstream Education towards the Holistic ‘Way’ of Steiner Education?” (Doctoral Thesis). University of Cambridge.

- Unger, R. M. 2005. What Should the Left Propose? London: Verso.

- Van Galen, J. A. 1988. “Ideology, Curriculum, and Pedagogy in Home Education.” Education and Urban Society 21 (1): 52–68.

- Van Galen, J. 1991. “Ideologues and Pedagogues: Parents who Teach their Children at Home.” In Home Schooling: Political, Historical and Pedagogical Perspectives, edited by J. Van Galen, and M. A. Pitman, 63–76. Norwood: Ablex Publishing.

- Walker, J. 2015. “Waldorf, Montessori, Unschooling: Alternative Education Comes to China.” Reason. February 11. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://reason.com/blog/2015/02/11/waldorf-montessori-unschooling-alternati.

- Wang, N. 2020. “一所中國大陸另類學校發展之研究:理念與實踐的落差 [A Study on the Development of an Alternative School in Mainland China: The Gap Between Idea and Practice].” (Master Thesis). Taiwan Normal University.

- Wang, C. 2022. “Resurgence of Confucian Education in Contemporary China: Parental Involvement, Moral Anxiety, and the Pedagogy of Memorisation.” Journal of Moral Education, 1–18. Doi:10.1080/03057240.2022.2066639 .

- Wang, Y., and R. K. Chan. 2015. “Autonomy and Control: The Struggle of Minban Schools in China.” International Journal of Educational Development 45: 89–97.

- Wang, J. J., B. Wang, and C. H. Wu. 2018. “中国‘在家上学’发展的新动向 [New Trends in the Development of ‘Homeschooling’ in China].” In 中国教育发展报告2018 [Annual Report on China's Education 2018], edited by D. P. Yang, 291–305. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press.

- Willis, P. 2020. Being modern in China: A Western Cultural Analysis of Modernity, Tradition and Schooling in China Today. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Wilson, M. A. F. 2016. “The Traces of a Radical Education: Neoliberal Rationality in Sudbury Student Imaginings of Educational Opportunities.” Critical Education 7 (6): 1–19.

- Woods, P. A., and G. J. Woods. eds. 2009. Alternative Education for the 21st Century: Philosophies, Approaches, Visions. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Wu, S. 2012. “大理, 新式教育乌托邦 [Dali, a New Education Utopia. Southern Metropolis Daily].” 南方都市报 [Southern Metropolis Daily]. December 12. Accessed 28 July 2021. http://news.sina.com.cn/c/2012-12-12/042025788398.shtml.

- Wu, S. 2013. “华德福高烧下的教育自救 [Waldorf School in China: Educational Self-salvation under Waldorf Fever].” Goethe Institut in China. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://www.goethe.de/ins/cn/zh/kul/mag/20628795.html.

- Xiong, J. N., and Y. G. Li. 2011. “北京‘现代私塾’的现状与出路 [The Current Situation and Outlet of ‘Modern Private School’ in Beijing].” 北京社会科学 [Social Science of Beijing] 5: 57–61.

- Yang, J. 2018. “中国创新小微学校调查报告 [China's Innovation School Development Report].” In 中国教育发展报告2018 [Annual Report on China's Education 2018], edited by D. P. Yang, 272–290. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press.

- Yu, T. 2008. “The Revival of Confucianism in Chinese Schools: A Historical-Political Review.” Asia Pacific Journal of Education 28 (2): 113–129.

- Yuan, Y. C. 2016. “120平方米的教育试验田 [An Educational Experiment Field of 120 Square Meters].” Chinese Youth Daily. November 2. Accessed 28 July 2021. http://zqb.cyol.com/html/2016-11/02/nw.D110000zgqnb_20161102_1-12.htm.

- Yuan, X. 2021. “Refusing Educational Desire: Negotiating Faith and Precarity at an Underground Chinese Christian School.” Asian Anthropology 20 (3): 1–20.

- Yuan, F. Y., and H. Q. Liu. 2014. “从‘在家上学’到非学校型态实验教育 [From ‘Homeschooling’ to Non-school Experimental Education].” In 中国教育发展报告2014 [Annual Report on China's Education 2014], edited by D. P. Yang, 201–212. Beijing: Social Science Academic Press.

- Zhou, Y. Y. 2014. “一个北大爸爸的‘中国式在家上学’的探索 [Exploration of Chinese-styled Homeschooling of a Father Graduated from Peking University].” 腾讯教育[Tencent Education]. May 12. Accessed 28 July 2021. https://edu.qq.com/a/20140512/021934.htm.