ABSTRACT

In response to declining results in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) surveys, the then governing Swedish coalition in 2010–2014 introduced earlier grading, more extensive national testing and a new standards-based curriculum. These reforms coincided with a greater emphasis on inclusive’ education understood in the ‘narrow’ sense of placement in mainstream schools. The combination of these two sets of reforms presents an interesting national case where traditional conservative demands for a core curriculum, testing and accountability were combined with calls to increase educational opportunity. Combining different methods and analysis of five separate waves of PISA data, we show that the reforms coincided with a decline in the sense of school belonging among pupils that was exceptional compared to other high-income countries, and especially among marginalised pupils. The study adds to the cumulative work of previous studies on policy effects on wellbeing, concluding that the Swedish compulsory school went from undergoing a mediatised results crisis to a mental health crisis among pupils.

摘要

为应对国际学生评估项目(PISA)测试结果的下滑,2010至2014年期间,当时的瑞典联合政府出台了更早期的学校分级、更广泛的国家测试和基于标准的新课程。这些改革举措恰逢当时对特殊学生回归主流学校的 “狭义” 全纳教育的政策关注。这两套改革方案的结合呈现了一个有趣的国家案例,即传统保守主义对核心课程、测试和问责的诉求与对增加教育机会的呼吁相互结合。综合不同的研究方法以及对五次独立 PISA 数据的分析,我们发现这些改革与学生学校归属感的下降表现相关。与其他高收入国家相比,这种下降较为罕见,尤以边缘化的学生体验为甚。本研究补充了以往研究关于政策对福祉影响的累积成果,得出的结论是:瑞典义务教育阶段学校经历了从媒介参与下的结果危机向学生出现心理健康危机的转变。

Introduction

‘We are changing Swedish education policy in its entirety: earlier grading, more national tests, higher standards … We are implementing the greatest changes of Swedish education policy since 1842’ (Lindqvist Citation2013). Jan Björklund, the Swedish Minister of Education, certainly set the bar high when describing the reform agenda of the centre-right coalition of which he was a part. Declining results for Swedish pupils in the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) surveys had contributed to a mediatised ‘crisis discourse’ surrounding the country’s education system (Grey and Morris Citation2018; Nordin Citation2014). As a direct response to the ‘crisis’, the coalition government introduced earlier grading, more extensive national testing, stricter criteria for eligibility to enter upper secondary school and a new standards-based and performance-oriented curriculum in the years 2010–2014 (Lundahl, Hultén, and Tveit Citation2017; Wahlström and Sundberg Citation2015). These far-reaching reforms, with their emphasis on outputs and results, marked a break with previous modes of organising core activities in Swedish schools (Wahlström Citation2014).

The education policies of the governing coalition also included another, less discussed, set of reforms that sought to improve the democratic and participatory dimensions of education. For example, the Education Act of 2010 inculcated ideals on inclusive education with the goal of increasing the number of pupils in difficulties – i.e. pupils who have difficulties reaching stated learning goals, including pupils with special education needs – attending mainstream schools and classrooms.

Today, roughly ten years after these ‘greatest changes of Swedish education policy since 1842’, we are beginning to compile the empirical evidence on their consequences for pupils’ social and emotional wellbeing. This much we know thus far: the new grading system increased school-related stress and reduced academic self-esteem and wellbeing (Högberg et al. Citation2021a), with the negative effects being larger for pupils with low cognitive ability (Klapp, Klapp, and Gustafsson Citation2021). The stricter eligibility criteria led to higher rates of school failure, and in the long term to an increased take-up of disability benefits among youth with poor grades (Halapuu Citation2021). The reforms also coincided with a decline in the reported feeling of school belonging among pupils (Högberg et al. Citation2021b). In a sense, one may say that education in Sweden simply lurched from crisis to crisis – swapping a results crisis for a mental health crisis among pupils.

These negative consequences, and the fact that they have been felt most strongly by marginalised pupils, are noteworthy when set against the background of the strong democratic ideals that have long underpinned and characterised the Swedish education system and society as a whole (Grek et al. Citation2009; Wiborg Citation2013). Indeed the early PISA reports themselves hailed Sweden as a country that combined high learning outcomes with equity and high wellbeing (OECD Citation2004).

In this article, we present a unique national case study that contributes to our knowledge about the impact of education policy – and especially policy change – on pupils’ sense of belonging at school. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first comprehensive study to analyse such effects and relationships using an international comparative design. Inspired by Ball (Citation1993, 10), we use ‘a toolbox of diverse concepts and theories’. Our starting point is empirical work within the Swedish curriculum theory tradition that provides us with in-depth analyses of policy texts, teacher surveys and interview data (Wahlström and Sundberg Citation2015). We draw special attention to the two sets of reforms mentioned above, arguing that they have particular explanatory value in relation to reduced school belonging, especially among marginalised pupils. Hence, our focus is on performance orientation and inclusive education. Our efforts to get a grip of the above changes in policy reminded us about the complexity, inconsistency and ‘messiness’ of policymaking and governing (Clarke et al. Citation2015). We thus acknowledge that policy may be the result of negotiation and struggle among different actors. The ways that seemingly contradictory ideals of performance orientation and inclusive education found their way into the same reform package is an example of ‘hybridisation’, i.e. ‘the cross-breeding of different logics, language and practice in policy definition and action, which reinforces their ambiguous and composite character’ (Maroy Citation2009, 80; see also Anderson-Levitt and Gardinier Citation2021).

We combine these resources with large-scale survey data from PISA and recent methods for quantitative comparative case studies (Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller Citation2015). While the focus is on Swedish education, our study takes a comprehensive view of trends in school belonging between 2000 and 2018 through a comparative analysis of 40 high-income countries.

Background

Social belonging and the message system of education

Various theories and different strands of research have incorporated the concept of ‘belonging’ to school. It is a central component within the field of inclusive education, especially in research that draws on the ‘broad definition’ of inclusion that concerns all pupils and marginalised groups, i.e. not only those with disabilities (Haug Citation2017). In different ways, such research takes as a point of departure the international policy agenda of Education for All (UNESCO Citation1990) and the Salamanca statement (UNESCO Citation1994), that stress the need to address all forms of exclusion regarding access, participation and outcomes. Numerous studies have critically examined policies on inclusion in different contexts (see e.g. Ainscow, Slee, and Best Citation2019).

There is also a rich sociological and philosophical tradition that explores the concept of belonging, often with a focus on the symbolic dimension of social relations and interactions (Durkheim Citation1912; Honneth Citation1995; Mead Citation1934; Weber Citation1921). For instance, Durkheim emphasised the role of education in instilling a sense of belonging to wider society, but also described the precarious nature of social solidarity. Sudden transformations in the social structure may gave rise to a mismatch between idealised social goals and what individuals are actually able to achieve. Such changes, argued Durkheim, produce anomie, i.e. feelings of disconnection, frustration, anxiety and non-belonging (Durkheim Citation2005). These ideas have gained renewed topicality in recent debates on the crisis – or dark side – of meritocracy (Sandel Citation2020; see also Beach Citation2021; Markovits Citation2019). The promise of meritocracy, which underpins much of contemporary Western culture, is that anyone, regardless of background, can succeed through merit, hard work and, not least, educational attainment. In a situation characterised by stalled social mobility and growing social inequality, however, the market-driven meritocratic ideal of education as the ‘great equaliser’ falls short and has given rise to growing differences between winners and losers. Pupils who fail in the meritocratic testing culture fall by the wayside and are left to face the reality of their failure without any consolation that they are not personally to blame; the demoralising effects on their sense of human worth and belonging can be devastating (Sandel Citation2020).

This broad body of literature calls attention to the importance of belonging not only for individualś subjective experiences, feelings and social relations – it also points to urgent political problems that societies face as social divisions continue to deepen. At the centre of this is the relationship between belonging and education policy. Bernstein, for example, has stressed inclusion in school as a condition for communitas – ‘the right to be included, socially, intellectually, culturally and personally’ – within a model ‘to compare what happens in various education systems’ (Bernstein Citation2000, pp. xx–xxi). On the same note, Slee (Citation2019, 917) has concluded that ‘[b]elonging is the anchor from which fundamental reforms to organisational life and the message system of education: curriculum, instruction and assessment proceed’.

We argue that international PISA data on young peoples’ sense of belonging – their responses to statements on ‘outsiderdom’, feelings of awkwardness, friendships and loneliness in school over time – has the potential to provide important comparative insights on the effects of such reforms.

The Swedish education reforms

In this study, we focus on two specific dimensions of the reform agenda for education in the period 2010–2014.

We begin with policies regarding performance orientation. Several intertwined reforms over this period changed the meaning and consequences of pupils’ school performance. One major reform was the new standards-based curriculum for the compulsory school (Lgr 11), which was introduced in 2011–2012. The curriculum marked a shift from a competence-oriented to a performance-oriented pedagogical model and introduced clearer prescriptions regarding standards: that is, the detailed descriptions of what is required to obtain a certain grade (Bernstein Citation2000; Wahlström and Sundberg Citation2015). With the stronger focus on standards, moreover, came an emphasis on evaluation and an assessment discourse that was oriented towards what was missing or absent in pupilś work and thus made deviations visible. The result was a greater ‘formalism and instrumentalism’ (Wahlström and Sundberg Citation2015, 75) in relation to teaching and learning, as pupils became more focused on what was being evaluated, and what they had to do in order to meet the requirements. As teaching oriented pupils towards assessment in core subjects, their personal interests and knowledge development were relegated to the background (Wahlström and Sundberg Citation2015).

The change towards performance orientation was included in a discourse of equivalence and equity (Wahlström and Sundberg Citation2015). Summarising these developments, Wahlström (Citation2014, 735) concluded that ‘a strong Swedish tradition of a compensatory understanding of equivalence has been redefined and fused as a right to reach the same objectives at the same time (in terms of standards)’. Drawing on the work of Lingard and Keddie (Citation2013), she identified a shift from ‘from “pedagogies of difference” and the former compensatory view of equivalence, where pupils who needed most support were also allocated most resources, to “pedagogies of the same”’ (Wahlström Citation2014, 735).

Another set of reforms concerned grading (with teacher-assigned grades), national testing and eligibility criteria for upper secondary school. Grades are the key instrument used to sort pupils in the Swedish education system, and therefore the stakes they carry for pupils are high indeed (Lundahl, Hultén, and Tveit Citation2017). In this study, we look at pupils in the last year of compulsory school (9th school year), for whom access to upper secondary school depends on their 9th-year grades.

Major changes in policies regarding grading, testing and eligibility criteria were implemented between 2010 and 2013. First, a new grading system was introduced, one which implied a more fine-grained ranking and differentiation of pupils, including a new grade level for pupils not up to a standard to pass. A notable aspect was that the new grading system disproportionally punished failures, as pupils’ weakest performance in relation to the specified standards for a subject determined their overall grade in that subject. The resulting incentive structure meant that pupils had to perform at top level throughout the school year to avoid failure (Swedish Government Official Reports Citation2020). Second, in order to anchor the new grading system, national tests were given a more dominant role in determining course grades (Wahlström Citation2014), and new national tests were introduced in several subjects. Third, stricter eligibility criteria for entry to upper secondary school were introduced, with ineligible pupils being placed in introductory programmes that are often dead-ends, meaning that many fail to transfer to a regular programme and instead leave upper secondary school without a diploma.

A second set of reforms concerned inclusive education with regard to pupils in difficulties (e.g. pupils with special education needs, but not only those with disabilities). ‘Inclusion’ can here be understood both in the narrow sense of placement in mainstream schools and in the broader sense of adequate support for all pupils in mainstream schools (Nilholm and Göransson Citation2017). In Sweden, pupils experiencing difficulties can either attend a mainstream compulsory school or attend special schools for pupils with learning disabilities. Pupils must display significant intellectual disability in order to attend special schools, while other pupils who face difficulties in schools are entitled to special support within the mainstream compulsory school system. They can then either be given this support in the mainstream classroom, in separate special teaching groups, or (in rare cases) in special resource schools. Although comparisons are difficult due to varying definitions across countries, Sweden stands out as having among the lowest proportion of pupils in special classes or schools among all European countries in the period 2012–2016 (no comparative data are available before 2012; European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education Citation2021).

Two reforms implemented over the period 2011–2014 had particular implications concerning how inclusive education was practised in Sweden. First, the requirements regarding placement of pupils in special schools or in special teaching groups became stricter, especially for pupils with autism-related conditions. The new Education Act prescribed that special support should be given to pupils within the mainstream classroom, and only if specific reasons existed could pupils be given support in separate groups (Education Act Citation2010:Citation800). Second, new regulations came into effect that limited access to more extensive forms of special support. The first line of support came to be known as ‘additional adjustment’, which was to be given in mainstream classrooms and as part of ordinary teaching. An evaluation by the Swedish School Inspectorate concluded that these additional adjustments were inadequate, partly because the adjustment was left to the teachers with insufficient support from special educators (Swedish Schools Inspectorate Citation2016).

From a Bernsteinian perspective the co-existence of the two dimensions within the same reform package constitutes a incongruity. According to Bernstein (Citation2000), the performance model typically takes as a starting point differences between children’s abilities, while the spatial organisation is characterised by regulatory boundaries that limit access. Such modes of stratification displace and render less visible differences between pupils. The combined consequence of these reforms was instead that more pupils in difficulties attended an increasingly performance-oriented and competitive mainstream compulsory school, organised through a message system where the promotion of inclusion and the maintenance of belonging as a social disposition were not centre stage. At the same time, fewer of these pupils were given support to deal with this new environment.

Education reforms and school belonging

There are reasons to expect that the aforementioned reforms impacted school belonging negatively, particularly among marginalised pupils such as those in difficulties (e.g. low-achieving pupils) or pupils with a working-class or migration background. Research on school belonging stresses that practices which emphasise frequent evaluation and that incentivise pupils to compare and compete with each other through external rewards such as grades, can lead to heightened self-focus, anxiety and fear of failure in relation to schoolwork, and to weaker school belonging (Eccles and Midgley Citation1989; Yoon and Järvinen Citation2016). American and British studies have also shown that intense and high-stakes testing can have negative effects on other dimensions of school-related wellbeing, such as internalising and externalising behaviours and school engagement (Holbein and Ladd Citation2017; Markowitz Citation2018; West and Sweeting Citation2003). Since practices that value pupils based on their performance imply that pupils with poorer grades or test results will be valued lower, such negative effects may be particularly pronounced for them (Eccles and Midgley Citation1989), especially if they are not given adequate support to perform on equal terms. Moreover, increased instrumentalism in relation to teaching and learning can undermine pupils’ intrinsic motivation and opportunities to find meaning in the educational content, and in turn reduce their school belonging (Elliott et al. Citation2019; Yoon and Järvinen Citation2016).

Materials and methods

In line with Elliott et al. (Citation2019), we argue that large-scale survey data has the potential to offer valuable insights if integrated in more comprehensive analyses of particular contexts. We therefore use survey data from PISA, which allow for comparative analyses of school belonging across countries and time. Sampling methods and questionnaires are harmonised across countries and survey waves, and identical items on school belonging have been included in all countries and in most survey waves since 2000.

Managed by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), PISA is the largest and arguably most influential ongoing international school survey (Grek et al. Citation2009; Grey and Morris Citation2018). It has a repeated cross-sectional design, with data collected in high- and middle-income countries every three years since 2000. Data are collected in two stages. In the first stage, at least 150 schools are sampled, with sampling probability based on the number of pupils. In the second stage, 35–42 pupils aged 15 from the sampled schools are selected with equal probability (OECD Citation2018).

We include all countries that are members of the OECD or EU (European Union) in the analysis, and all survey waves with data on school belonging, namely: 2000, 2003, 2012, 2015 and 2018 (the items on school belonging were not included in the 2006 and 2009 surveys). The total sample size with complete data on covariates is more than 800,000 pupils in 40 countries, among which 18,500 are Swedish.

Outcome variable: School belonging

PISA contains a set of items that aims to measure pupils’ sense of belonging at school, and which has been used in previous comparative studies on the topic (Elliott et al. Citation2019; Yoon and Järvinen Citation2016). Pupils are given six statements to consider, as follows: (a) ‘I feel like an outsider (or left out of things) at school’; (b) ‘I make friends easily at school’; (c) ‘I feel like I belong at school’; (d) ‘I feel awkward or out of place in my school’; (e) ‘Other students seem to like me’; and (f) ‘I feel lonely at school’. Response options are: (0) Strongly agree, (1) Agree, (2) Disagree and (3) Strongly disagree. We follow the approach recommended by PISA, and use a generalised partial credit model to combine the items into a scale, with higher values indicating higher school belonging (mean 0.086; standard deviation 0.895; range −3.009–1.854).

The theoretical underpinning of the PISA index of school belonging is derived from psychology (OECD Citation2017). However, the analytical focus of the items – do pupils feel included in the school community and do they have a sense of connection to the school as an institution? – clearly has a bearing on inclusive education as well as the broader sociological and philosophical tradition of belonging. These items are thus relevant if we are to understand the effects of particular message systems in education – such as high-stakes testing – on social identities and school-related feelings of wellbeing.

Indicators of marginalisation

We operationalise marginalisation as poor academic achievement, disadvantaged social background and migration background. Achievement is measured through a pupil’s reading and mathematics scores in PISA. Since we are specifically interested in marginalised pupils at risk of experiencing exclusion, we dichotomise the scores at the 10% percentile for each country and survey year. That is, we investigate if the bottom 10% of pupils in terms of achievement scores were affected differently by the reforms compared with the top 90%. We measure social background by parental occupational class. The reported occupations of parental occupations are mapped onto the international socio-economic index of occupational status, and pupils are assigned the highest-ranked occupation of either parent. We dichotomise this at the 10% percentile. As for migration background, we distinguish between pupils born in Sweden and foreign-born pupils (7.4% of the Swedish sample and 5.4% of the OECD/EU sample).

PISA also collects information about pupils classified as having special education needs. Although these data are not publicly available for all countries, we managed to get access to individual-level data for Sweden in 2018. These data show that pupils with special education needs are heavily over-represented among low-achieving pupils, pupils from working-class backgrounds and foreign-born pupils. Thus, while we cannot directly estimate the effects for pupils with special education needs, it seems reasonable to assume that we will effectively capture this group through our indicators of marginalisation.

Covariates

In the regression models (see below), we control for gender, age, achievement in reading and mathematics, parental occupational class and migration background, and for the classroom disciplinary climate, with all of these measured at the individual level. Moreover, the Swedish education reforms under consideration here coincided with an explosive global growth in the use of smartphones and social media platforms, which, according to Twenge et al. (Citation2021), harms school belonging. To account for this, we control for pupils’ use of digital technology and social media, specifically their access to computers and the Internet (available from 2000) and how often they use social media (available from 2012). We measure these both at the individual level and at the country level, by aggregating the individual responses to the level of countries. The country averages account for the fact that pupils who do not themselves use social networks may be excluded from important social arenas if their peers use them frequently. Additional country-level control variables include GDP per capita, the share of the population aged 25–34 with tertiary degrees, total social expenditure and the unemployment rate.

Analytical procedures

We combine three analytical methods. The first stage of the analysis is descriptive. We show how school belonging has evolved over time in Sweden compared with other OECD or EU countries, with a specific focus on changes stemming from the Swedish education reforms.

In the second and third stages, we use synthetic control and difference-in-difference designs to more formally test the role of the Swedish education reforms. The synthetic control design is a statistical technique adapted to comparative case studies (Abadie, Diamond, and Hainmueller Citation2015). In this study, the case is Sweden, while the potential comparison countries are any member countries of the OECD or EU. The idea is to find one or more comparison country that is as similar to Sweden as possible in all respects of relevance for the outcome of school belonging. Sweden is then compared with these comparison countries before and after the reforms that were implemented in Sweden. If Sweden and the comparison countries differ with regard to school belonging after but not before the reforms, it is likely that the reforms that were implemented only in Sweden are responsible for the different outcomes.

Unlike qualitative comparative case studies, which typically use theory and previous research to guide the selection of comparison countries, the synthetic control design is a data-driven technique that matches the case (i.e. Sweden here) with relevant comparison countries based on their quantitative similarities. Similarity is here defined as being similar in terms of different statistical variables, where the variables can be predictors of the outcome as well the outcome itself. Based on their similarities to Sweden, all potential comparison countries are assigned a weight such that the weighted average of control units best matches the characteristics of Sweden before the reforms. This weighted average of comparison countries is called ‘synthetic Sweden’, and constitutes the counterfactual scenario to which the development in Sweden is compared. To anticipate the results, we show that Sweden before the reforms was most similar to Norway and Austria – two other Western European high-income countries with high levels of school belonging. Synthetic Sweden then expresses a weighted average of school belonging in Norway and Austria. The effect of the reforms is defined as the difference in school belonging between Sweden and synthetic Sweden after the reforms. The underlying idea is here that (1) a weighted average of all potentially relevant comparison countries provides a more valid counterfactual for Sweden than any single country alone, and (2) that this average can account for measured (i.e. variables that are in the data) but also unmeasured determinants of levels of school belonging. Only if Norway and Austria were similar to Sweden before the Swedish reforms in terms of both measured factors and unmeasured factors (factors that are not available in the data, but that apparently generated similarly high levels of school belonging in these countries) would they provide a good match.

To implement this, we first create a dataset with the average score on the school belonging index for all countries and years with complete data on school belonging. We then match Sweden with potential comparison countries based on average school belonging in the years prior to the reforms. The 2012 survey was conducted in the middle of the reform period, and it is not obvious if it is to be regarded as taking place prior to or after the reforms. Since some of the reforms were not implemented until later (e.g. the new grading system and cutbacks in special support), and since the reforms that had been implemented by then may not have had an immediate effect on school belonging, we choose to regard the 2012 survey as occurring prior to the reform in our main analyses.

In the third and last stage of the analysis, we use a difference-in-difference design to test for inequalities in the effects of the reforms. In the basic setting, a difference-in-difference design compares two groups before and after an event, such as a reform, that only affects one of the groups. The effect of the reform is defined as the difference between the change over time in the outcome in the group that is affected by the reform and the equivalent change in the other group. This design controls for differences between the groups that do not vary over time, as well as for time trends that are common to both (Imbens and Wooldridge Citation2009). A numerical example may clarify this further. Say that we dichotomise school belonging into low vs. high belonging, and a reform is implemented in Sweden but not in Norway. If the share of pupils with high belonging is 70% in Sweden and 40% in Norway before the reform, and 50% in Sweden and 40% in Norway after the reform, the estimated effect of the reform is −20%. This is because the difference between Sweden and Norway before the reform was 30% (70–40 = 30), the corresponding difference after the reform was 10% (50–40 = 10), and the difference between 30 and 10% is 20%.

We extend this basic setting using multiple groups (countries) and periods (survey years), including all OECD or EU countries and all surveys with data on school belonging. We measure the Swedish education reforms by a variable that takes the value 1 in Sweden in the years 2015 and 2018, and 0 otherwise. We estimate the difference-in-difference design through a two-way fixed effects regression model, with fixed effects for countries and survey years (Imbens and Wooldridge Citation2009). The country fixed effects hold constant all differences across countries that do not vary over time, such as stable aspects of the education systems or linguistic differences. The year fixed effects hold constant all differences over time that do not vary across countries, such as technological innovations that appear simultaneously across the included countries. In order to investigate inequalities in the effects of the reforms, we interact our focal reform variable with our indicators of marginalisation.

The triangulation of three comparative methods has some important advantages. The descriptive analyses are transparent, as they visualise how the Swedish developments compare to all other OECD or EU countries. They can thereby provide prima facie evidence of a reform effect, in that they make clear if the Swedish developments after the reforms in question diverge from other countries. The synthetic control design tests this more formally, by generating an explicit counterfactual for Sweden. The synthetic design derives strength and credibility from both qualitative and quantitative traditions in comparative research. From the qualitative, case-oriented tradition, it takes the in-depth focus on the particularities of a specific case. From the quantitative tradition, it takes the capacity to compare this case with a large number of countries in a systematic way. In this sense, the synthetic control method is a hybrid between the small-N case-oriented and large-N variable-oriented traditions in comparative research. The difference-in-difference design complements this by enabling the use of standard tools for statistical inference and more flexibility in analyses of inequalities in effects.

Results

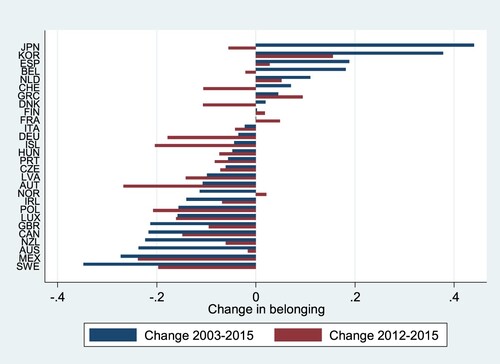

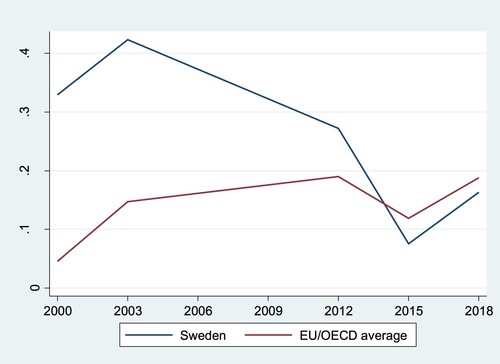

We begin with descriptive results. shows the changes in average levels of school belonging between 2003 and 2015, and between 2012 and 2015, in all included countries that have data in all years. We see that the decline in Sweden between 2003 and 2015 is the greatest among all countries, and the decline between 2012 and 2015 is, alongside Iceland and Poland, the third largest; only Mexico and Austria have greater declines. shows the change over the full period 2000–2018 in Sweden compared with the average for all OECD/EU countries. School belonging in Sweden declined between 2003 and 2012, and then fell dramatically between 2012 and 2015, in stark contrast to the average levels in OECD/EU countries. Sweden went from having, alongside Austria and Germany, the highest average levels of school belonging in 2000 and 2003, to having a score below the OECD/EU average in 2015. Another way to express the magnitute of the Swedish decline is to note that the median (50th percentile) Swedish pupil in 2015 would, with the same score on the school belonging scale, have been at the 35th pecentile, or close to the bottom third of the distribution, in 2003.

Figure 1. Changes in school belonging 2003–2015 across EU and OECD countries. Data from PISA (waves 2000, 2003, 2012, 2015, 2018). Only countries with complete data on school belonging from all survey waves (2000–2018) included.

Figure 2. Trends in school belonging 2000–2018. Data from PISA (waves 2000, 2003, 2012, 2015, 2018). Only countries with complete data on school belonging from all survey waves (2000–2018) included.

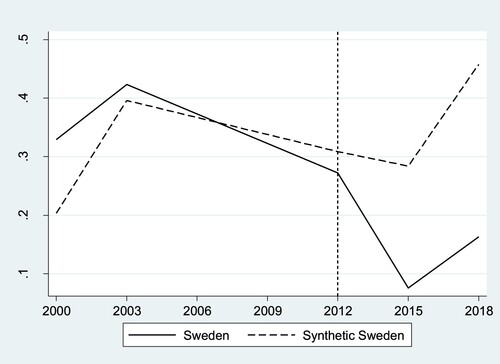

shows the development in Sweden compared with a more limited but relevant comparison group: the countries that before 2012 were most similar to Sweden in terms of school belonging, or ‘synthetic’ Sweden. Synthetic Sweden is here a weighted average of Austria and Norway – two other countries with high school belonging in 2000–2012. We see that the fit between Sweden and synthetic Sweden before 2012 is rather poor, with Sweden having slightly higher school belonging in 2000–2003, and slightly lower in 2012. This indicates that synthetic Sweden does not completely capture the peculiarities of the Swedish case, and does not form an ideal counterfactual to Sweden. The results of the synthetic control analysis should therefore be considered as suggestive but best taken with a grain of salt. Nevertheless, the clear divergence between Sweden and synthetic Sweden after 2012 indicates that something extraordinary did occur in Sweden around 2012 that did not occur in the countries that prior to that point most resembled Sweden.

Figure 3. School belonging in Sweden compared to synthetic Sweden. Data from PISA (waves 2000, 2003, 2012, 2015, 2018). Only countries with complete data on school belonging from all survey waves (2000–2018) included.

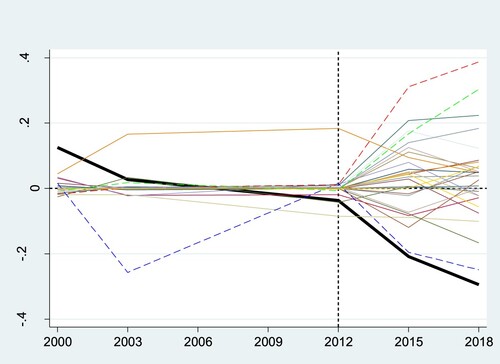

As a further way to analyse whether the Swedish development is exceptional, we estimated equivalent synthetic control analyses for all OECD/EU countries with data on school belonging in all years. That is, all countries are matched with a weighted set of comparison countries based on their similarities before 2012. We then calculated the gap in school belonging between that country and its synthetic counterpart before and after 2012. shows the results of this analysis. The thick black line shows the gap between Sweden and synthetic Sweden, while the other lines (coloured) show the corresponding lines for all other countries. We see that most of the lines are close to 0 before 2012, indicating that a relevant weighted set of comparison countries (synthetic counterparts) are available for most countries in the data. We also see that the gap between Sweden and synthetic Sweden after 2012 is among the largest of all gaps, and the single largest negative gap (i.e. indicating a decline in school belonging compared with its synthetic counterpart). The only countries with similarly sized gaps are Korea (red-dashed line), Norway (green-dashed line) and Japan (blue-dashed line). Unlike Sweden, both Korea and Norway have positive gaps, meaning that school belonging increased in these countries relative to their synthetic counterparts. In the case of Norway, this is explained by the fact that synthetic Norway largely consists of Sweden, in which school belonging strongly declined. Japan, like Sweden, has a negative gap. However, Japan and its synthetic counterpart (which largely consists of Korea) show a very poor fit before 2012, which indicates that synthetic Japan does not provide a relevant comparison. All in all, the results presented in again suggest that the Swedish decline after 2012 is rather exceptional from a comparative perspective.

Figure 4. Gap in school belonging between each country and its synthetic counterpart. Data from PISA (waves 2000, 2003, 2012, 2015, 2018). Only countries with complete data on school belonging from all survey waves (2000–2018) included.

In the last stage of the analysis, we used two-way fixed effects models to test inequalities in the effects of the reforms, with results presented in . The first two columns can be seen as further robustness tests of the results already presented. Column 1 shows that the variable indicating the education reform has a negative and statistically significant effect on school belonging. Column 2 shows that this negative effect is robust to controlling for pupils’ use of social media. Since these data are only available from 2012 onwards, we present the results with these controls in a separate column. The estimated effects of the reform are −0.171 (column 1) and −0.165 (column 2) scale points. In sum, the Swedish decline after 2012 cannot be explained by a greater use of digital technology or social media, nor by any other variable included in the models.

Table 1. Two-way fixed effects regression models with school belonging as the outcome.

Columns 3–6 show results for inequalities in school belonging. The columns show the estimated effects of the reforms separately for pupils depending on their achievement in reading and mathematics, and socio-economic class and migration background. Beginning with column 3, we see that the decline for the top 90% of pupils in terms of reading achievement was −0.168, while the corresponding decline for the bottom 10% was −0.210, or 25% (0.042 scale points) larger. The difference between the two groups is, however, not statistically significant at the standard 5% level. Column 4 shows that the decline for the top 90% in terms of mathematics achievement was −0.219 and for the bottom 10% −0.355. The decline for low-achieving pupils was thus 62% (0.136 scale points) larger, a statistically significant difference. Note that the average decline for both groups combined differs from that in column 3; this is because data on mathematics achievement are available only from 2003. Columns 5 and 6 show that the decline for the top 90% in terms of class background and for Swedish-born pupils was, respectively, −0.159 and −0.166 scale points, while the corresponding decline for the bottom 10% in terms of class background and for foreign-born pupils was, respectively, −0.262 and −0.254 scale points. The decline for pupils from a working-class background and foreign-born pupils was thus around 60% (around 0.1 scale point) larger than for their respective reference groups. In sum, the reform increased the inequalities in school belonging based on achievement, parental class and migration background by between 25 and 60%.

Discussion and conclusions

The point of departure for this study was a set of major reforms of the Swedish education system introduced between 2010 and 2014. The reforms were implemented against the background of a mediatised ‘crisis discourse’ related to declining results in PISA surveys, and marked a shift towards stronger performance-orientation but also a greater emphasis on the placement of pupils in difficulties in mainstream classrooms and less extensive special support for these pupils. Using data from PISA, and combining different analytical methods, we show that the reforms coincided with a substantial decline in the sense of school belonging among Swedish pupils, that this decline was almost exceptional in comparison with other high-income countries and that the decline was largest among marginalised pupils, specifically low-achieving pupils, pupils from working-class backgrounds and foreign-born pupils.

Although quantitative research on the role of education policy in influencing school belonging is scarce, our conclusions regarding the role of performance orientation and inclusion are broadly in line with the literature to date. For instance, studies have found that intense and high-stakes testing can have negative effects on school-related wellbeing (Markowitz Citation2018; West and Sweeting Citation2003), especially among marginalised pupils (Holbein and Ladd Citation2017). Also of relevance is the work of Yoon and Järvinen (Citation2016) and Elliott et al. (Citation2019), who all show that East Asian pupils generally report the lowest levels of school belonging among countries participating in PISA. These authors interpret the low school belonging in East Asia with reference to the intense competitiveness, test-driven meritocratic ideals and instrumental view of education that characterises these education systems. In the context of this study, it is also noteworthy that the two countries with highest school belonging – Austria and Germany – are also characterised by a low use of accountability tools such as high-stakes testing (Högberg and Lindgren Citation2021). Our results are, moreover, consistent with the psychological literature on school belonging, not least with the potentially negative effects of intense evaluation, social comparison and competition emphasised by stage-environment fit-theory (Eccles and Midgley Citation1989).

We argue that the results of this study provide a vital piece of information that helps us understand the puzzle of declining wellbeing among Swedish adolescents and youth (Ågren and Bremberg Citation2022). Alongside previous studies that have demonstrated the negative effects of the more intense grading and national testing (Högberg et al. Citation2021a; Klapp, Klapp, and Gustafsson Citation2021) and stricter eligibility criteria (Halapuu Citation2021), the results of this study suggest that ‘the greatest changes of Swedish education policy since 1842’ may not have been so ‘great’ after all, at least not from the perspective of pupils’ wellbeing. Against this background, it is noteworthy that the discourse surrounding the reforms – especially regarding the curricula, grading system and national testing – was characterised by a strong emphasis on output and results, while issues concerning the wellbeing of pupils were rarely highlighted, if at all (e.g. Proposition Citation2008/Citation09:Citation87). By and large, the architects behind the reforms overlooked the potential (and indeed likely) effects of increased performance orientation on pupilś wellbeing. On the contrary, more testing was introduced with the argument that children struggling in school should be identified and given special support at an earlier stage (Bagger Citation2015). In fact, Jan Björklund’s emphasis on ‘knowledge’, on traditional values, high claims and expectations were often articulated as an attempt to restore the particular school – a school for all – that made his own journey possible: that of a boy from an ordinary working-class background all the way to being Minister of Education.

However, our ambition was not to analyse discrepancies between policy intentions and effects in terms of unintended effects. Hence, we have not tried to identify any of the actual intentions behind the policies, and nor have we assumed any coherence of intentions or that the true character of political intentions are always openly displayed. For example, Jan Björklund made a u-turn in 2018 over inclusive education, criticising ‘the social democratic idea on equality’ and claiming that ‘the idea of inclusion, that all children, regardless of preconditions, shall attend the same school class, has gone too far’ (Björklund Citation2018). Such swift changes in political manoeuvres among stakeholders underscore the inherent futility of attempts to identify any fixed and essential character or original intentions behind policies (Clarke et al. Citation2015; Dahler-Larsen Citation2014).

Instead, we have identified the hybridisation effects (Maroy Citation2009) of performance culture and a narrow version of inclusion. We conclude that although these reforms may appear incongruous, they do merge into a successful political strategy that combines traditional small-c conservative demands for a core curriculum for all pupils, testing and accountability and calls to reduce social inequality by increasing educational opportunity (Labaree Citation2010). Swedish education policy in the early 2010s succinctly captures this rhetorical blend, incorporating both a shift towards stronger performance-orientation – including more intense grading and testing – and a discourse of equivalence and equity where all pupils should have the right – or ‘the same opportunities’ – to reach certain knowledge goals (Wahlström and Sundberg Citation2015, 34). As noted by Haug (Citation2017), education policy often combines inclusive-driven initiatives with policies that may actually disrupt inclusive ambitions and practices. This specific mode of hybridisation is indicative of education policy in Sweden and can be seen as an augmentation of meritocratic ideals involving a doublespeak that embraces ambiguous ideas such as raised standards, credentialism, inclusion and equality of opportunity. The results presented in this study can thus be seen as a national case study on the dark side of meritocracy, where profound changes in the message system of schools produce increasing differences between winners and losers, and feelings of non-belonging among the latter (cf. Sandel Citation2020; see also Elliott et al. Citation2019). Overall, the results corroborate Haug’s conclusion that:

accountability, neo-liberal market orientation and individualization, as well as school competition and demands for higher academic standards, all produce effects that could be obstructive to inclusive ideas in education, and that do not promote inclusive schools. (Haug Citation2017, 211)

These caveats notwithstanding, the timing, character and size of the decline in school belonging in Sweden indicate that the focal reforms in this study did play a dominant role. First, with regard to timing, school belonging was stable between 2000 and 2003, declined noticeably after 2003 and then dramatically after 2012, and then again stabilised in relation to other EU and OECD countries after 2015.Footnote1 It is difficult to square this pattern with slow and gradual changes, such as greater segregation, being the dominant cause(s). Second, the character of the decline in school belonging – with the decline being particularly strong for low-achieving pupils, pupils from working-class backgrounds and foreign-born pupils – suggests that we must find an explanation that can account for why these pupils were hit harder. We believe that the combination of increased performance orientation and inclusion following a narrow definition as placement provides just such an explanation. Third, the fact that the Swedish decline was almost exceptional in a comparative perspective suggests that it cannot be reduced to a manifestation of a broader global trends, and that the explanatory focus ought to be on the particularities of the Swedish case.

In conclusion, this study has contributed to the evidence about an intense period of educational reform in Sweden. The study confirms the initial and somewhat blunt thesis that Swedish schools went from a mediatised results crisis to an anomic health crisis among pupils, especially for those who already faced high risks of marginalisation. According to a recent study that points to relations between the peculiarities of the Swedish education system and declining wellbeing, mortality due to alcohol, drugs and suicides has increased in young Swedes during the last few decades in a way that is unique in Western Europe but similar to developments in the USA (Ågren and Bremberg Citation2022). While we of course can make no inferences regarding mortality based on this study, this does remind us of Durkheim’s thesis that anomic suicide – or what is currently described as ‘deaths of despair’ – is the ultimate consequence of a declining sense of belonging.Footnote2

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

This work was supported by VR; the Swedish Research Council (grant number 2018–03870_3).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Björn Högberg

Björn Högberg is Associate Professor at the Department of Social Work, Umeå University. The present study is part of a research project investigating consequences of education reforms for the wellbeing of pupils.

Joakim Lindgren

Joakim Lindgren is Associate Professor at the Department of Applied Educational Science, Umeå University. His scholarly interests are education policy, marketisation, evaluation, school inspection and problems of socialisation and juridification in education.

Notes

1 displays a general increase in social belonging in EU and OECD countries after 2015. As for Sweden, one possible explanation could be the high exclusion rate. The overall exclusion rate within a country could not exceed 5% of the target population. In Sweden 11.1% of the students were excluded from the 2018 PISA test, largely due to a high influx of refugee students. Hence, a significant group of students with low school belonging is absent in the data after 2015.

2 Additional information of relevance to the study is supplied in the online supplemental materials, available through the journal website. This includes descriptive statistics, a technical appendix and results from of a range of supplementary and sensitivity analyses.

References

- Abadie, A., A. Diamond, and J. Hainmueller. 2015. “Comparative Politics and the Synthetic Control Method.” American Journal of Political Science 59 (2): 495–510. doi:10.1111/ajps.12116

- Ainscow, M., R. Slee, and M. Best. 2019. “Editorial: The Salamanca Statement: 25 Years on.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (7-8): 671–676. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1622800

- Anderson-Levitt, K., and M. Gardinier. 2021. “Introduction Contextualising Global Flows of Competency-Based Education: Polysemy, Hybridity and Silences.” Comparative Education 57 (1): 1–18. doi:10.1080/03050068.2020.1852719

- Ågren, G., and S. Bremberg. 2022. “Mortality Rends for Young Adults in Sweden in the Years 2000–2017.” Scandinavian Journal of Public Health 50 (4): 448–453.

- Bagger, A. 2015. “Prövningen av en skola för alla. Nationella provet i matematik i det tredje skolåret.” (Dissertation). Umeå University.

- Ball, S. J. 1993. “What is Policy? Texts, Trajectories and Toolboxes.” The Australian Journal of Education Studies 13 (2): 10–17.

- Beach, J. M. 2021. The Myths of Measurement and Meritocracy: Why Accountability Metrics in Higher Education Are Unfair and Increase Inequality. New York: Rowman Littlefield.

- Bernstein, B. 2000. Pedagogy, Symbolic Control and Identity: Theory, Research, Critique. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishers.

- Björklund, J. 2018. “DN Debatt. “Skrota idén om lika för alla - ge fler extra skolår”.” Dagens Nyheter, April 20. https://www.dn.se/debatt/skrota-iden-om-lika-for-alla-ge-fler-extra-skolar/.

- Clarke, J., D. Bainton, N. Lendvai, and P. Stubbs. 2015. Making Policy Move: Towards a Politics of Translation and Assemblage. Bristol: Policy Press.

- Dahler-Larsen, P. 2014. “Constitutive Effects of Performance Indicators: Getting Beyond Unintended Consequences.” Public Management Review 16 (7): 969–986. doi:10.1080/14719037.2013.770058

- Durkheim, E. 1912. The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. London: Allen & Unwin.

- Durkheim, E. 2005. On Suicide. London: Routledge.

- Eccles, J. S., and C. Midgley. 1989. “Stage/Environment Fit: Developmentally Appropriate Classrooms for Early Adolescents.” In Research on Motivation in Education, edited by R. E. Ames, and C. Ames, 139–186. San Diego, CA: Academic Press.

- Education Act. 2010:800. Stockholm: Utbildningsdepartementet.

- Elliott, J., L. Stankov, J. Lee, and J. Beckmann. 2019. “What Did PISA and TIMSS ever do for us?: The Potential of Large Scale Datasets for Understanding and Improving Educational Practice.” Comparative Education 55 (1): 133–155. doi:10.1080/03050068.2018.1545386

- European Agency Statistics on Inclusive Education. 2021. https://www.european-agency.org/data/cross-country-reports. Accessed 2021.01.05.

- Grek, S., M. Lawn, B. Lingard, J. Ozga, R. Rinne, C. Segerholm, and H. Simola. 2009. “National Policy Brokering and the Construction of the European Education Space in England, Sweden, Finland and Scotland.” Comparative Education 45 (1): 5–21. doi:10.1080/03050060802661378

- Grey, S., and P. Morris. 2018. “PISA: Multiple ‘Truths’ and Mediatised Global Governance.” Comparative Education 54 (2): 109–131. doi:10.1080/03050068.2018.1425243

- Halapuu, V. 2021. “Access to Education and Disability Insurance Claims.” IFAU Working Paper 17: 1–51.

- Haug, P. 2017. “Understanding Inclusive Education: Ideals and Reality.” Scandinavian Journal of Disability Research 19: 206–217. doi:10.1080/15017419.2016.1224778

- Holbein, J. B., and H. Ladd. 2017. “Accountability Pressure: Regression Discontinuity Estimates of How No Child Left Behind Influenced Student Behavior.” Economics of Education Review 58: 55–67. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2017.03.005

- Honneth, A. 1995. The Struggle for Recognition: The Moral Grammar of Social Conflicts. Cambridge: Polity Press.

- Högberg, B., and J. Lindgren. 2021. “Outcome-Based Accountability Regimes in OECD Countries: A Global Policy Model?” Comparative Education 57 (3): 301–321. doi:10.1080/03050068.2020.1849614

- Högberg, B., J. Lindgren, K. Johansson, M. Strandh, and S. Petersen. 2021a. “Consequences of School Grading Systems on Adolescent Health: Evidence from A Swedish School Reform.” Journal of Education Policy 36 (1): 84–106. doi:10.1080/02680939.2019.1686540

- Högberg, B., S. Petersen, M. Strandh, and K. Johansson. 2021b. “Determinants of Declining School Belonging 2000–2018: The Case of Sweden.” Social Indicators Research 157 (2): 783–802. doi:10.1007/s11205-021-02662-2

- Imbens, G. W., and J. Wooldridge. 2009. “Recent Developments in the Econometrics of Program Evaluation.” Journal of Economic Literature 47 (1): 5–86. doi:10.1257/jel.47.1.5

- Klapp, T., A. Klapp, and J. E. Gustafsson. 2021. “The Impact of Assessment System on Students’ Psychological, Cognitive, and Social Well-Being.” American Educational Research Association (AERA), Annual Meeting 2021.

- Labaree, D. 2010. Someone Has to Fail: The Zero-Sum Game of Public Schooling. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Lindgren, J., S. Carlbaum, A. Hult, and C. Segerholm. 2020. Skolans arbete mot kränkningar: juridifieringens konsekvenser. Malmö: Gleerups.

- Lindqvist, M. 2013. “Riskkapitalister stängde hans skola.” Hufvudstadsbladet. 2013.10.26

- Lingard, B., and A. Keddie. 2013. “Redistribution, Recognition and Representation: Working Against Pedagogies of Indifference.” Pedagogy, Culture & Society 21 (3): 427–447. doi:10.1080/14681366.2013.809373

- Lundahl, C., M. Hultén, and S. Tveit. 2017. “The Power of Teacher-Assigned Grades in Outcome-Based Education.” Nordic Journal of Studies in Educational Policy 3 (1): 56–66. doi:10.1080/20020317.2017.1317229

- Markovits, D. 2019. The Meritocracy Trap: How America’s Foundational Myth Feeds Inequality, Dismantles the Middle Class, and Devours the Elite. New York: Penguin Press.

- Markowitz, A. J. 2018. “Changes in School Engagement as a Function of No Child Left Behind: A Comparative Interrupted Time Series Analysis.” American Educational Research Journal 55 (4): 721–760. doi:10.3102/0002831218755668

- Maroy, C. 2009. “Convergences and Hybridization of Educational Policies Around ‘Post-Bureaucratic’ Models of Regulation.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 39 (1): 71–84. doi:10.1080/03057920801903472

- Mead, G. H. 1934. Mind, Self and Society: From the Standpoint of a Social Behaviorist. Chicago, IL: University of Chicago Press.

- Nilholm, C., and K. Göransson. 2017. “What is Meant by Inclusion? An Analysis of European and North American Journal Articles with High Impact.” European Journal of Special Needs Education 32 (3): 437–451. doi:10.1080/08856257.2017.1295638

- Nordin, A. 2014. “Crisis as A Discursive Legitimation Strategy in Educational Reforms: A Critical Policy Analysis.” Education Inquiry 5 (1): 24047. doi:10.3402/edui.v5.24047

- OECD. 2004. What Makes School Systems Perform? Paris: OECD publishing.

- OECD. 2017. PISA 2015 Results (Volume III): Students’ Well-Being. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD. 2018. PISA 2018 Technical Report – Chapter 4 Sample Design. Paris: OECD publishing.

- Proposition. 2008/09:87. “Tydligare mål och kunskapskrav – nya läroplaner för skolan”.

- Sandel, M. J. 2020. The Tyranny of Merit: What’s Become of the Common Good? New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

- Slee, R. 2019. “Belonging in an age of Exclusion.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (9): 909–922. doi:10.1080/13603116.2019.1602366

- Swedish Government Official Reports. 2020. Bygga, bedöma, betygssätta – betyg som bättre motsvarar elevernas kunskaper. SOU 2020:43.

- Swedish Schools Inspectorate. 2016. Skolans arbete med extra anpassningar –Kvalitetsgranskningsrapport. Stockholm: Skolinspektionen.

- Twenge, J. M., J. Haidt, A. B. Blake, C. McAllister, H. Lemon, and A. Le Roy. 2021. “Worldwide Increases in Adolescent Loneliness.” Journal of Adolescence 93: 257–269. doi:10.1016/j.adolescence.2021.06.006

- UNESCO. 1990. World Declaration on Education for All and Framework for Action to Meet Basic Learning Needs. Paris: UNESCO.

- UNESCO. 1994. Final Report: World Conference on Special Needs Education: Access and Quality. Paris: UNESCO.

- Wahlström, N. 2014. “Equity: Policy Rhetoric or a Matter of Meaning of Knowledge? Towards a Framework for Tracing the ‘Efficiency-Equity’ Doctrine in Curriculum Documents.” European Educational Research Journal 13 (6): 731–743. doi:10.2304/eerj.2014.13.6.731

- Wahlström, N., and D. Sundberg. 2015. “Theory-based Evaluation of the Curriculum Lgr 11.” IFAU Working Paper 2015: 11.

- Weber, M. 1921. The City. New York: Free Press.

- West, P., and H. Sweeting. 2003. “Fifteen, Female and Stressed: Changing Patterns of Psychological Distress Over Time.” Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry 44 (3): 399–411. doi:10.1111/1469-7610.00130

- Wiborg, S. 2013. “Neo-Liberalism and Universal State Education: The Cases of Denmark, Norway and Sweden 1980–2011.” Comparative Education 49 (4): 407–423. doi:10.1080/03050068.2012.700436

- Yoon, J., and T. Järvinen. 2016. “Are Model PISA Pupils Happy at School? Quality of School Life of Adolescents in Finland and Korea.” Comparative Education 52 (4): 427–448. doi:10.1080/03050068.2016.1220128