?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.Abstract

In the context of the Colombian internal conflict, rural communities engaged in subsistence agriculture and traditional modes of production, most of which are not highly profitable, are significantly affected by displacement. We explain this finding by the use of a game-theoretical model where the government obtains income and provides security for regions while the armed group extorts productive agriculture and chooses the percentage of subsistence farmers to force out from their lands. By displacing population, the armed group reallocates land from subsistence to modern agriculture, increasing the potential gains from extortion. We find that if land productivity is sufficiently high and the proportion of land devoted to modern productive agriculture is small, the government provides low security, and displacement occurs. The government only prevents displacement if the income obtained from the region exceeds the cost of security provision which occurs when the proportion of land devoted to subsistence agriculture is sufficiently small. Predictions from the theoretical model are tested using a panel data set of Colombian municipalities for 2003–2017. Results from the fixed-effects panel estimations indicate that municipalities with collective titles exhibit higher IDPs expulsion rates, in accordance with the theory. Findings from the model could also shed light on other countries where forced displacement is aimed at land reallocation that allows for a more productive use of this resource.

En el contexto del conflicto interno de Colombia, las comunidades rurales que implementan la agricultura de subsistencia y los métodos de producción tradicionales, la mayoría de los cuales no son muy rentables, se ven afectadas por el desplazamiento de manera significativa. Explicamos este descubrimiento mediante un modelo simple de la teoría de juegos, en el que el Gobierno obtiene ingresos y brinda seguridad para las regiones, mientras que el grupo armado extorsiona la agricultura productiva y selecciona el porcentaje de agricultores de subsistencia para expulsar de sus tierras. Mediante el desplazamiento de la población, el grupo armado redistribuye la tierra de la agricultura de subsistencia a la moderna y aumenta las posibles ganancias provenientes de la extorsión. Observamos que, si la productividad de la tierra es lo suficientemente alta y la proporción de tierra dedicada a la agricultura productiva moderna es pequeña, el Gobierno brinda poca seguridad, y tiene lugar el desplazamiento. El Gobierno solo evita el desplazamiento si los ingresos obtenidos de la región superan el costo de la provisión de seguridad, lo cual se produce cuando la proporción de tierra dedicada a la agricultura de subsistencia es lo suficientemente pequeña. Los descubrimientos del modelo teórico se contrastan con el caso de las comunidades que ocupan los territorios ancestrales en la región del Pacífico del país y participaron en un gran programa colectivo de títulos de propiedad. Los descubrimientos del modelo también pudieron clarificar otros casos de migración forzada en las comunidades que implementan los métodos tradicionales de producción en todo el mundo.

Dans le contexte du conflit intérieur colombien, les communautés rurales pratiquant une agriculture de subsistance et des modes de production traditionnels, dont la plupart ne sont pas très rentables, sont fortement touchées par les déplacements de population. Nous expliquons cette conclusion en utilisant un modèle simple de théorie des jeux où le gouvernement obtient des recettes et assure la sécurité des régions tandis que le groupe armé extorque l’agriculture productive et choisit le pourcentage d’agriculteurs de subsistance à expulser de leurs terres. En déplaçant la population, le groupe armé réaffecte les terres d’agriculture de subsistance à l’agriculture moderne, augmentant ainsi les gains potentiels liés à l’extorsion. Nous constatons que si la productivité des terres est suffisamment élevée et que la proportion de terres consacrées à l’agriculture productive moderne est faible, le gouvernement offre une faible sécurité et des déplacements de population ont lieu. Le gouvernement n’empêche ces déplacements que si les recettes obtenues de la région dépassent le coût de la fourniture de la sécurité, ce qui se produit lorsque la proportion de terres consacrées à l’agriculture de subsistance est suffisamment faible. Les conclusions du modèle théorique sont mises en contraste avec le cas des communautés occupant des territoires ancestraux dans la région Pacifique du pays qui ont pris part au vaste programme d’attribution de titres de propriété collective. Les conclusions du modèle pourraient également apporter un éclairage sur d’autres cas de migration forcée intervenant dans des communautés pratiquant des modes traditionnels de production dans le monde entier.

Introduction

Forced migration is one of the many ways in which armed conflicts affect civilian populations. In Colombia, more than eight million people have been forcibly displaced in the last thirty five years of internal conflict. This continues to represent the largest population of Internally Displaced Persons (IDPs) of concern to the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, followed by Siria and the Democratic Republic of Congo (UNHCR [United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees] Citation2021).

Forced displacement in Colombia takes place in the context of a low intensity, protracted internal conflict where three main actors can be identified: left-wing guerrillas, right-wing paramilitaries, and the State. The conflict dynamics have experienced significant transformations such as the demobilization of the AUC, the largest paramilitary structure, in 2004-2005 and the peace agreement signed by the Colombian government and the FARC, the largest guerrilla group, in 2016. Nevertheless, high levels of violence continue to strike the country due to dissident factions that decided not to demobilize, criminal bands that emerged to gain control of the emptied territories or businesses and common delinquency that continues to operate (Maher and Thomson Citation2018).

In some situations, forced migration could be considered the collateral damaged of attacks and clashes between armed forces. In other cases, it is a deliberate strategy used by armed groups to achieve specific economic, strategic or military objectives (Azam and Hoeffler Citation2002; Balcells and Steele Citation2016; Palacios Citation2011; Bandiera Citation2021). This paper aims to explore an alternative explanation for displacement, namely, that armed groups find it profitable to reallocate land from subsistence to commercial agriculture.

A key element of this rationale for forced displacement is that, besides illegal activities such as drug production, illegal armed groups also profit from extortion on legal production (referred to as “vacuna” in Colombia). This type of extortion is akin to an illegal tax where the victim must pay the illegal group to either obtain protection or avoid being harmed. This assumption is appropriate for the Colombian case since illegal taxation, by both left and right-wing illegal groups, is a pervasive practice in this country. Official figures show that starting in 2010, cases of extortion have been increasing with a maximum of 8,200 cases in 2019 (Ministerio de Defensa Citation2021). Nevertheless, this is likely to be an underestimation since only victims of the most serious cases decide to report. The illegal nature of this practice constitutes an obvious barrier to precisely quantify its magnitude but it has been suggested that total extortions in the country amounted to US$1,000 million in 2013.Footnote1 Qualitative studies support the idea that this was, and continues to be, a widespread practice that affects many productive sectors in the country such as agribusiness, cattle ranching and oil (Velez Citation2001; Porch and Rasmussen Citation2008; Ballvé Citation2013; Grajales Citation2013; Defensoria del Pueblo Citation2018; Richani Citation2005).

We propose a game-theoretic model where, in the context of an ongoing civil conflict, both a government and an armed group derive income from, either legally or illegally, taxing the agricultural activities of a region. However, not all agricultural activities are taxable: only a fraction of the productive land is devoted to modern profitable (and taxable) agriculture. The complement is devoted to subsistence agriculture and does not produce enough income to be taxed. An interesting equilibrium arises in regions characterized by (potentially) high land productivity and a large share of subsistence agriculture. In these areas, both players can benefit from reallocating land to the most profitable type of agriculture. Therefore, the government chooses to provide low security for the region and the armed group displaces a fraction of the population engaged in traditional agriculture to free up land for the establishment of agri-business.

The expansion of a large collective titling program in Colombia is used to examine the implications of the theoretical model. The program was specifically targeted at communities of Afro-descendants that had occupied ancestral territories and preserved traditional modes of production. Titles were granted under the condition that property could not be transfer and that land should be used for traditional, rather than modern, production. At the same time, these communities have been disproportionately affected by displacement. Our interpretation is that although the land some of them occupy is potentially very productive, the current institutional arrangement impedes the market mechanism to allocate it to the most productive use. This, in turn, provides an incentive for armed groups, to evict peasants and reallocate the land use. We test predictions from the theoretical model using fixed-effects panel estimations for Colombian municipalities for the 2003–2017 period.

The model proposed in this paper provides one, among many, potential explanation for the forced displacement observed after the first collective titles were granted in 1996. Although the dynamics of the Colombian conflict have evolved over time and several demobilization, disarmament, and reintegration processes have taken place, new and morphed illegal armed structures such as the Black Eagles, Urabeños, Rastrojos, and dissidents factions of the FARC continue to operate. These organizations maintain their capability of extorting productive activities and reallocating land in the less secure areas of the country (Ch et al. Citation2018; Maher and Thomson Citation2018).

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows. Section “Literature Review” presents the literature review while the general background of the collective titling program is described in Section “General Background”. Section “The Model” is devoted to the theoretical model. Section “Empirical Evidence from Collective Titling” presents the empirical evidence and Section “Conclusions” concludes.

Literature review

Forced displacement is a complex phenomenon with multiple causes. The collateral damaged view, also called mass evasion by Steele (Citation2017), interprets displacement as a non-intentional consequence of violent actions perpetrated by combatants. However, the fact that in many cases deliberate threats, as opposed to generalized violence, are the main trigger of displacement contradicts this view (Davenport, Moore, and Poe Citation2003). A growing number of studies challenge this approach and advance the idea that forced displacement is a deliberate strategy of armed groups aimed at achieving specific goals such as reducing enemies’ efficiencies (Azam and Hoeffler Citation2002), gaining control over disputed regions (Balcells and Steele Citation2016) or reducing the tax revenue the government can collect from an area (Palacios Citation2011).

For the specific case of Colombia, the empirical evidence suggests that the presence of public forces, access to social services, the gasoline tax, central government transfers, and rural consumption are associated with fewer IDPs. On the contrary, the presence of illegal armed groups, homicide rates, unsatisfied basic needs, conflict intensity, coca cultivated area, and royalties are positively related to displacement (Engel and Ibáñez Citation2007; Ibañez and Velez Citation2008; Dueñas, Palacios, and Zuluaga Citation2014; Lozano-Gracia et al. Citation2010).

A relatively recent strand of the literature investigates the link between agricultural production and displacement in Colombia. Thomson (Citation2011), for instance, explicitly links forced displacement and land grabbing to the establishment of large agri-business in Colombia. In the same line, Potter (Citation2020) narrates the historical evolution of African oil palm cultivation in Colombia, emphasizing the salient role of violent land grabbing. Specific case studies for this crop argue that the transformation from subsistence to commercial agriculture was largely due to the violence inflicted on peasants that forced them to leave their lands. This reallocation of land use has been documented for different areas across the country such as Meta (Maher Citation2015) and Bolivar (Gómez, Sánchez-Ayala, and Vargas Citation2015). More recently, Bandiera (Citation2021) has empirically established a relationship between the price of bananas and forced displacement that is stronger in areas with less formalization of land ownership.

Starting with Oslender (Citation2007), several studies have documented the link between violence and land reallocation specifically for communities with collective titles. One of the most emblematic cases occurred in the Lower Atrato Valley where the large Jigumiando and Curvado community council received a collective title in December 2000 (Grajales Citation2011, Citation2013; Ballvé Citation2013). Paramilitaries’ attacks against civilians in this area intensified in 2001 causing most of them to forcibly migrate. In the next years, the region saw an expansion of oil palm cultivation. Results from official investigations indicate that twelve oil palm companies had illegally appropriated more than 26,000 hectares. Similar findings have been reported by Sánchez-Ayala and Arango-López (Citation2015) for the San Cristobal community council in Bolivar.

In a related study, Ahmed et al. (Citation2020) find that the incidence of paramilitary violence is indeed higher in municipalities where Afro-descendant communities have organized to request collective titles. They propose that collective titling is an element that empowers Afro-descendant communities, arousing concern among elites that are allied with illegal armed actors. Therefore, an increase in violent actions in such a way that inhabitants are forced to flee is a way to counter these new de jure rights, that are perceived as a threat to the status quo. Although this may be a plausible explanation for the disproportionate incidence of violence for some communities, the fact that the emptied land is (ex-post) exploited for commercial agriculture suggests that, in some cases, there are sizeable economic gains from forced migration. The previous findings suggest the need for a new theory that accounts for forced displacement as a mechanism of land reallocation that allows illegal armed groups to increase their income.

General Background

The 1991 constitution explicitly recognized, for the first time, that Colombia was a multiracial and multicultural country and that ethnic minorities should be granted collectives titles. Law 70 of 1993 regulated the allocation of collective property rights for Afro-Colombians and other ethnic groups with the aim of preserving their identity, culture, and traditional modes of production. To be eligible for a collective title, each community should organize into a “Communal Council” (CC) that acts as the governing body for the management of the land (Velez et al. Citation2020). The process starts with a petition submitted by the CCs to the Agencia Nacional de Tierras (National Land Agency), followed by technical evaluations and hearings with stakeholders. The petitions received, including details such as georeferenced location, as well as the state of the process are public information available on the Agency’s webpage. Once the title is granted, CCs hold land rights of access, withdrawal, management, exclusion but not alienation (i.e. land cannot be sold). Law 70 of 1993 explicitly stated that “Hunting, fishing or gathering for subsistence should prevail over any commercial, semi-industrial, industrial, commercial or sportive exploitation (of land)”.

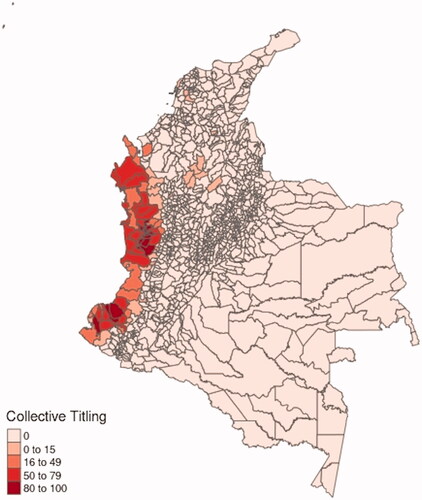

Afro-Colombians have occupied their ancestral territories in the Pacific region of the country since the XVII century. However, before Law 70, these areas were considered natural reserves, and these communities had no formal rights over them. The first collective title was granted in 1996 to six CC located in the Riosucio municipality, department of Chocó. Since then, more than 170 collective titles covering almost six million hectares, approximately 5% of the total area of the country, have been granted. shows that the large majority of the 77 municipalities where these titles have been granted are located in the Pacific area of the country.

The Pacific region is one of the most disadvantaged in terms of socio-economic characteristics. Per capita income is lower compared to the national average and, with very few exceptions, more than 80% of the population is considered poor according to the multidimensional poverty index (Galvis-Aponte, Moyano, and Fajardo Citation2016). Child mortality rates are at least 10% higher compared with the national average and less than 30% of the population actually contributes to the social security system (Urrea Citation2012). The precarious conditions of this population are the result of multiple causes such as high levels of conflict, cultivation of illicit crops, low human capital accumulation, and lack of state presence (Galvis-Aponte, Moyano, and Fajardo Citation2016).

The main economic activities of the Pacific region are subsistence agriculture, fishing, mining (silver and gold mainly), and timber exploitation. Traditional modes of production prevail for most of them as evidence by the fact that more than 40% of the agricultural production in Afro-descendant communities is used for subsistence or barter. Moreover, less than 25% of producers in parcels with collective titles own machinery (DANE [Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística] Citation2015).

There is a growing body of literature concerned with the potential effects of the titling program on several dimensions. Although this new institutional arrangement modified de jure land rights, Velez (Citation2011) report that de facto rights still prevail as reported by community leaders. Peña et al. (Citation2017) provide one of the most rigorous and comprehensive evaluations of the program, using as a control group rural districts without collective titles. They find positive effects on poverty reduction, per capita income residential investment, and an increase in school attendance for primary students. It has been estimated that collective titles caused a 27% reduction in land deforestation in the Pacific region (Velez et al. Citation2020). Nonetheless, negative effects have also been reported. Ahmed et al. (Citation2020) provide empirical evidence of a significant increase in right-wing paramilitary activity in municipalities where CCs were being organized and titles were granted. Lobo and Velez (Citation2020) find that many CCs have turned to coca cultivation as a profitable alternative to overcome economic hardship. The authors suggest that the type of communal leadership and organization are key determinants of the adoption of illegal activities.

The Model

We propose a game-theoretical model to illustrate our main points. We assume that a country has agricultural regions. Each region

(with

to

) has T units of productive land. Regions differ in the following characteristics:

land productivity of region

percentage of land devoted to modern profitable (and taxable) agriculture. The complement,

represents the percentage of land devoted to subsistence agriculture. This subsistence agriculture does not generate enough income to be taxed.

Land productivity and the percentage of land devoted to modern agriculture

will be key parameters in the model. It is likely that these parameters are positively correlated for most regions: a high level of land productivity should be associated with a large fraction of land devoted to modern agriculture. Although we could model

as a function of

we retain two separate parameters to capture the idea that institutional factors (such as collective titling) could create a wedge between them.

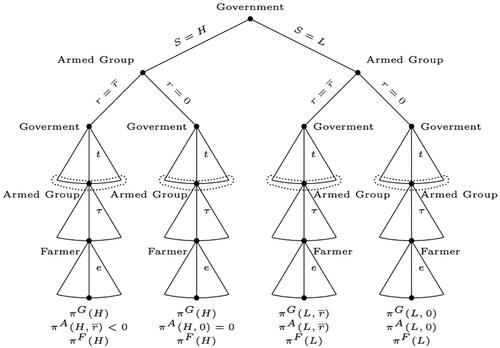

In each region a sequential game takes place between three players: the government (G), the illegal armed group (A), and an agricultural firm (F). The timing of the game can be represented by the game tree presented in .

In the first stage, the government decides the level of security in the region. For simplicity we will assume that the level of security is binary: high (H) or low (L). In the second stage, the armed group decides the proportion of land to reallocate from subsistence to modern agriculture

As we will show below, although r is potentially a continuum variable, the assumptions of the model will imply that the armed group will choose either

. In the reallocation process, peasants in subsistence agriculture are displaced so the land can be assigned to agricultural firms. Although there is anecdotal evidence indicating that both left and right-wing illegal armed groups extort the civilian population to finance their operation, the reallocation of land to modern agriculture has been specifically documented for the paramilitaries. Therefore, we believe that the armed group’s behavior in the model is better suited to explain paramilitary groups. We will assume that the amount of displaced population

is equal to the number of units of land reallocated

In the third stage, the government and the armed group simultaneously impose taxes

and extortion

on the production of modern agriculture, respectively. Extortion will be modeled below as a tax

on agricultural output imposed by the armed group. As usual, this simultaneous decision is depicted in the game tree by its equivalent sequential movement representation where the second mover, the armed group, decides on extortion

without observing the level of taxes

chosen by the government. In other words, for the armed group, all the nodes after the government decision (surrounded by dashed line) are in the same information set. Finally, in the s, the agricultural firm decides the level of effort devoted to production and modern agricultural output is obtained. This output determines the realization of payoff for all the players in the game: government’s tax revenue, armed group’s extortion revenue, and agricultural firm’s net profit. This sequential game is solved using backward induction reasoning. We start with the agricultural firm problem from the last stage.

Stage 4: The Agricultural Firm

As we mentioned before, land in region has two possible uses: subsistence or modern agriculture. The productivity parameter

represents the potential land productivity of the region. This potential productivity can only be realized under modern agriculture. We, therefore, normalize subsistence agricultural production

to 0. In modern agriculture, production in region

is given by

where

is the effort the firm puts into producing the agricultural good. Alternatively,

could be thought of as an investment made by the agricultural firm. The production effort has costs

and the price of the agricultural good is normalized to 1. In stage four the agricultural firm knows the level of taxes

and extortion

defined by the government and the armed group in stage three. Therefore, the agricultural firm chooses

to maximize the following agricultural profit function

Solving the problem above yields the following optimal effort:

(1)

(1)

Replacing on the agricultural production function yields

Stage 3: Taxation and Extortion

In this stage, the government decides on tax and the armed group decides on the extortion

imposed to each agricultural firm in region

The latter assumption can be justified by the fact that extortion is a practice commonly used by illegal armed groups in different countries such as Colombia (see the Introduction), Afghanistan (Justin Citation2012; Byrd and Nooran Citation2017), Burundi (Sabates-Wheeler and Verwimp Citation2014) and Somalia (Shire Citation2021), among others. In this stage, both the level of security and the amount of land reallocated for region

are known to both players.

Following previous literature, we will model the government and the armed group as revenue- maximizing agents (Konrad and Skaperdas Citation1998; Grossman Citation1999; Collier Citation2000; Azam and Hoeffler Citation2002; Garfinkel and Skaperdas Citation2007). We will assume, however, that the capability to collect taxes and extortion is asymmetric: while the government can levy taxes on regions with low or high security the armed group can only enforce extortion on low security regions. This assumption is consistent with anecdotical evidence that connects extortion to regions with reduced state presence.Footnote2 Therefore, in the low-security scenario (s = L), the government chooses

to maximize tax revenue:

and the armed group maximizes extortion revenue:

The first-order conditions of these problems yield the following system of best response functions:

Solving this system of equations for and

we obtain the optimal levels

Hence, the optimal revenues for the government and the armed group are

Conversely, in the high security scenario (s = H), there is no extortion ( =0) and the government solves:

which yields

and a government’s tax revenue of

Comparing results from low and high security, we see that the government’s revenue is larger in the latter: the absence of extortion increases effort and output from the agricultural firm and also allows the government to impose a higher tax rate.

Stage 2: Land Reallocation and Forced Displacement

In this stage, the level of security chosen by the government in stage 1 is known to the armed group. In the same spirit of our assumption regarding extortion in stage 3, the armed group’s capability to reallocate land is limited by two conditions: the level of security in the region and the amount of public attention displacement attracts to the area.

Regarding the first restriction, we assume that land reallocation is only possible under low security. If the government has decided to provide high security in the first stage, then the percentage of land resignation is 0. On the other hand, if security in the first stage is low, the illegal armed group is able to reallocate land (

). Regarding the second restriction, we assume that a low profile is key for the armed group’s illegal activities. In a country such as Colombia, with a long-standing armed struggle, some displacement is expected. However, when the number of IDPs is sufficiently high, it attracts the attention of the public and usually forces the government to provide (at least temporarily) additional security or protection.Footnote3 Therefore, we assume that a level of displacement that becomes noticeable is costly for the armed group since the presence of the government implies that land reallocation is reversed and extortion revenue is lost.Footnote4 In addition, we assume that the armed group faces a cost

for each unit of land resigned.

For simplicity, we assume the following distribution for the probability of attracting attention which depends on the level of land reallocation

The fact that extortion revenue is increasing in and detection probability

remains constant for values below or equal to

, implies that if the armed group decides to reallocate land in region

it will choose

.

If the government chooses low security, the armed group will reallocate land if the profits with reallocation are larger than the profits without it. Under no land reallocation () and with a given level of modern agriculture

the armed group extortion profits are given by:

Since it will not attract attention

and will obtain extortion revenue

from the

fraction of land

devoted to modern agriculture. Under land reallocation (

), the armed group profits are given by:

Since , two scenarios are possible: with probability

the armed group attracts attention and obtains zero extortion revenue or, with probability

they do not attract attention, obtaining extortion revenue

from the

fraction of land

devoted to modern agriculture. The expected revenue generated by an additional unit of land

must be enough to cover the unitary cost

which implies that

θ. We will assume thereafter that the land productivity is sufficiently high so that

θ holds for every region

The armed group will choose if

) is higher than

Increasing from zero to

expands the land devoted to modern agriculture and the income generated by extortion, but it also implies a cost

and the possibility of detection and loss of extortion revenue. Solving for

we obtain:

(2)

(2)

EquationEquation (2)(2)

(2) represents a key relationship of the model. This condition is more likely to hold for higher values of land productivity

and lower values of

In other words, given that the government chooses low security, it is more likely that the armed group decides to reallocate land and displace population in regions with a combination of a low fraction of modern agriculture (

) and a relatively high land productivity (

). Conversely, in a region

with a sufficiently high fraction of land devoted to modern agriculture (

), the armed group will choose

to avoid risking existing extortion revenue by attracting public attention. Land reallocation is also more likely to occur the lower the detection probability

the lower the reallocation costs

and the higher the threshold

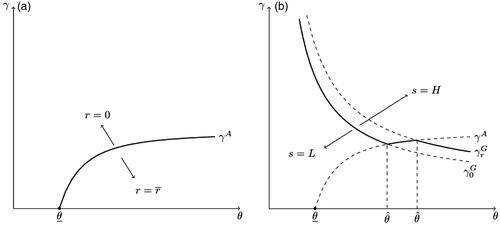

. Panel (a) in depicts the armed group threshold condition

. The armed group will choose land reallocation (

) and displacement for regions with combinations of

and

below the solid curve, and no land reallocation for regions with combinations above the curve.

The armed group best response function can be summarized as:

(3)

(3)

Stage 1: Government Security

In the first stage, the government chooses the (binary) level of security : high or low. As we mentioned before we make the simplifying assumption that the government only cares about the tax revenue and the security costs when choosing the security level

We assume that the cost of high security is

per unit of land while the cost of low security is normalized to 0. High security implies no extortion by the armed group, which in turn implies higher agricultural production and tax revenue. The government’s profits when security is high (

) are given by:

When security is low (

), the government’s profits depend on the best response level

of the armed group. For

the armed group extortion activity is not detected, so the government’s revenue is given by:

Therefore, under the government will prefer low security if

>

:

Solving for we obtain:

(4)

(4)

When

the armed group attracts public attention with probability

in which case land reallocation is reversed and extortion is prevented by the government at a cost

Therefore, with probability

the government’s income is

per unit of land. With probability

however, the armed group’s land reallocation and extortion activities are not detected, and the government revenue remains

per unit of land in modern agriculture. Therefore:

Under the government will prefer low security if

>

:

The government faces the following trade-off: low security implies lower tax revenue per unit of land due to the armed group’s extortion, but it also increases land devoted to modern agriculture (taxable output) and reduces the cost of security.Footnote5 Solving once again for we obtain:

(5)

(5)

Conditions Equation(4)(4)

(4) and Equation(5)

(5)

(5) show that the government will provide low security in regions with a low fraction of modern agriculture (

) and low productivity (

). These conditions, along with the armed group’s best response function in Equation(3)

(3)

(3) and the threshold level

in Equation(2)

(2)

(2) , define the optimal level of security chosen by the government:

where

and

are obtained from conditions

and

respectively, and are given by

The expression for requires that the probability of detection is not too high (

). We will assume that this condition holds for the rest of the analysis. Panel (b) in represents the government’s threshold conditions Equation(4)

(4)

(4) and Equation(5)

(5)

(5) along with the armed group’s threshold Equation(3)

(3)

(3) . The government will choose low security (

) for regions with a combination of

and

below the solid curve, and high security for regions with combinations above the curve.

Equilibria

Threshold conditions

and

define three equilibria in the model. Depending on the fraction of modern agriculture (

) and land productivity (

), each region

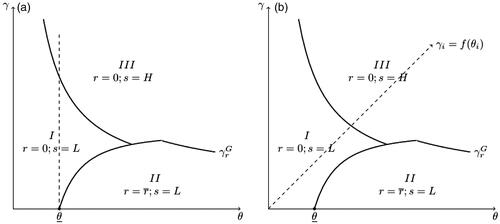

will fall in one of these three equilibria. Panel (a) in presents the intuition of these results. This figure is constructed from the solid curves in panels (a) and (b) in . These solid curves divide the figure into three distinct areas labeled I, II, and III.

Figure 4. Equilibria. Panel (a): equilibria. Panel (b): correlation between productivity and modern agriculture. Note. Area I: low security and no displacement. Area II: low security and displacement. Area III: high security and no displacement.

Area I depicts the combinations of and

that do not generate land reallocation by the armed group with low government security. We will restrict our attention to those combinations that are productive enough to be considered for reallocation by the armed group:

θ. Regions with intermediate levels of land productivity and a moderate fraction of land devoted to modern agriculture are likely to correspond to an equilibrium with low security and no land reallocation. Formally, the equilibrium conditions for

and

are defined by

and

such that

and

Area II depicts the key relationship of and

for this study. Regions with a relatively low fraction of land devoted to modern agriculture paired with medium to high levels of land productivity are more likely to correspond to an equilibrium with displacement and land reallocation. Formally, the equilibrium conditions for

and

are defined by

and

such that

and θ

, or

and

.

Finally, area III depicts combinations of and

with high security and no land reallocation in equilibrium. Regions with both moderate to high levels of land productivity and a significant fraction on land in modern agriculture will have no land reallocation due to the high security provided by the government. Formally, the equilibrium conditions for

and

are defined by

and

such that

and θ

, or

and

.

The following proposition summarizes the above results in a useful way to guide our empirical analysis:

Proposition 1.

For any region with land productivity

θ, a lower level of land devoted to modern agriculture

increases the probability that land reallocation (and therefore forced displacement) occurs.

Changes in parameters

and

will affect the thresholds

and

which in turn affect the equilibrium conditions. Land reallocation and displacement will be less likely for higher values of

and

and lower values of

and

.

Correlation between Land Productivity and Modern Agriculture

Our model does not restrict the relationship between land productivity and the fraction of modern agriculture

In reality, however, it is likely that these variables are positively correlated. Private property of land along with reasonably well-functioning markets will tend to allocate land to its most valuable use, which in this case is modern agriculture. We would therefore expect to see a strong correlation between

and

in a well-functioning market economy

Panel (b) in depicts this idea: regions would tend to be situated along the dashed line Notice that a strong correlation would imply that forced displacement due to land reallocation would be infrequent. Regulations that interfere with the market allocation mechanism would tend to move regions away from the dashed line. In particular, a reduction in

for a given

could increase the probability that a region falls in area II, which implies land reallocation and displacement. In the next section, we empirically study collective titling as a possible deviation in this direction.

Empirical Evidence from Collective Titling

The aim of this paper is to provide an alternative theoretical explanation for forced displacement based on land reallocation. The theoretical model we construct is aligned with the anecdotical evidence presented in the Introduction. In this section, we undertake an empirical exploration to put our model to an additional test. Ideally, to fully test our model we would require information such as the provision of security by the government in each region, extortion revenues and effective land reallocation. Unfortunately, such detailed information is not available. However, we can indirectly test the model using the intuition we gain from Section “Correlation between Land Productivity and Modern Agriculture”. The existence of restrictions to the market allocation mechanism in a region would tend to reduce the fraction of modern agriculture, for a given level of land productivity. Collective titling could be one possible example of this kind of regulation that discourages modern agriculture due to the collective action problem and the existence of credit constraints (Peña et al. Citation2017; Besley and Ghatak Citation2010). Moreover, regulations in Colombia explicitly discourage modern agricultural practices and agribusiness in the collectively titled lands (Law 70 of 1993). Therefore, it is expected that regions with large areas of collective titles and high land productivity are more likely to have land reallocation and forced displacement. The aim of this section is to empirically test this prediction at the municipal level, for the Colombian case.

Data and Variables

To test our hypothesis, we construct a panel data set for the Colombian municipalities. The theoretical model proposes a potential explanation for the forced displacement observed after the first collective titles were granted in 1996. Nonetheless, the information about conflict intensity, a key variable that allows us to control for the collateral damage type of displacement, is only available starting in 2003. Therefore, we restrict our sample to the 2003–2017 period. summarizes the variables, definitions, and sources while presents some descriptive statistics.

Table 1. Description of variables.

Table 2. Dependent and control variables descriptive statistics.

Our empirical approach is to test whether the presence of collective titles at the municipal level is associated with a higher level of IDPs. The dependent variable is the annual IDPs expulsion rate at the municipality level. The source for this variable is the Unit for the Victims’ Assistance and Reparation, the government agency that registers and supports all the victims of the Colombian conflict. To be registered, IDPs must inform a place and date of victimization which are used to calculate the annual number of IDPs expelled from each municipality. It should be clarified that this dataset does not include economic or seasonal migrants. The variable annual IDPs expulsion rate is calculated as the annual number of IDPs expelled from a municipality, divided by the municipality’s population in the same year, multiplied by 1,000.

The main variable of interest is the total area of collective titles granted in each municipality. All the details related to the title such as historical and social background, characteristics of the terrain, location, and limits can be found in the official decrees issued by the National Land Agency. The Observatorio de territorios étnicos y campesinos has georeferenced polygons for each collective title based on legal documentation, as well as the year it was conceded.Footnote6 As mentioned before, the area granted to each CC corresponds to the land traditionally inhabited by the Afro-Colombian communities. Thus, the location of a collective title is not restricted by the political and administrative units in which the country is divided and the unit of observation for our analysis (i.e. municipalities). A two-step procedure is followed to calculate the area under collective titles in each municipality. First, we identify the intersection of all collective title polygons, defined by the Observatorio de territorios étnicos y campesinos, with each municipality for each year. Second, for each municipality, we add up the area of all the intersections with collective titles. Since this variable corresponds to an area, it is measured in squared kilometers. This variable increases over time for some municipalities due to the new titles granted each year.

Most of the available anecdotical evidence that has linked forced displacement to the establishment of modern agriculture has focused on African oil palm and export-type banana crops (Grajales Citation2011, Citation2013; Ballvé Citation2013; Bandiera Citation2021; CNMH [Centro Nacional de Memoria Historica] Citation2015). These crops share two relevant characteristics: they are considered agri-business and have been classified as warm weather permanent intensive crops. Therefore, as a proxy for municipal land productivity, we will use the area deemed suitable for warm weather intensive permanent crops provided by the Agustin Codazzi Geographical Institute (IGAC). The IGAC calculates this land suitability based on time-invariant characteristics such as climate, soil profile and terrain ruggedness. We will also use a binary version of this variable defined as a dummy equal to 1 if there is any land suitable to produce warm weather permanent intensive crops in the municipality.

To account for possible confounding factors, we include control variables at the municipality level. Previous studies have identified economic conditions at origin as a key driver of the level of forced migration (Lozano-Gracia et al. Citation2010; Dueñas, Palacios, and Zuluaga Citation2014). For this reason, we include the per-capita tax revenue as a proxy for legal economic activity. We also control for the coca cultivated area in the municipality since previous literature has also suggested a link between illicit crops cultivation and forced displacement (Acevedo Citation2015; Palacios Citation2012). We also control for municipality population. Finally, to address the confounding effects of violence on displacement, we include a conflict intensity variable measured as the total number of terrorist and subversive actions in the municipality. This is a key control variable that allows us to account for the collateral damaged type of displacement.

The main prediction from the theoretical model indicates that forced displacement is more likely to occur where land productivity is high, but the fraction of land devoted to modern agriculture is low. This hypothesis highlights the role of land use as a trigger of displacement. For this reason, in the cross-sectional robustness check, we use the total area of productive land under collective tenure as the variable of interest. To construct this alternative measure, we use the 2014 Colombian Agricultural Census that contains detailed information about the agricultural production units, including the (self-reported) type of tenure. In contrast to the variable used in the panel estimation that measures the total area of collective titles as registered in the legal documentation (i.e. regardless of land use), the variable used in the cross-section specifically focuses on land that is actually being exploited for any type of production.

In the cross-section estimation, we include additional time-invariant controls at the municipal level such as municipality area, altitude, and a regional dummy. We also control for the municipality area devoted to agricultural activities based on the National Agrarian Census 2014.Footnote7 Although this variable does not distinguish between modern and subsistence agriculture, it is likely to be correlated with modern agriculture.

Estimations and Results

To test the predictions from the theoretical model we run fixed-effects panel estimations using data for the Colombian municipalities for 2003–2017. We exploit the time variation in the concession of the collective titles and the differences in the area granted and land suitability among municipalities, to identify the effect of collective titles on forced displacement. We estimate the following equation:

where

is the IDPs expulsion rate of municipality

in year

is the lagged area of collective titles granted in each municipality,

is the proxy for land suitability and

is a set of control variables at the municipality level that includes per-capita tax revenue, conflict intensity, coca cultivated area, and population.

are municipality fixed effects and

are time fixed effects. Municipality fixed-effects control for omitted time-invariant characteristics of the municipalities that may correlate with collective titling and forced displacement. Time-fixed effects control for time-varying common shocks that may affect all municipalities in the country. The main coefficients of interest are

and

According to the predictions from the theoretical model, collective titles should be positively associated with forced displacement (

Moreover, ceteris paribus, the larger the potential productivity of a region, the more likely it is that land reallocation and forced displacement will occur (

Results for the fixed-effects estimations are presented in . We use the lag of the collective titles variable in each municipality because land reallocation may not occur immediately after the title is granted. Results in column 1 suggest a statistically significant and positive association between collective titles and forced displacement that holds when controls at the municipality level are included, as shown in column 2. In column 3, we include an interaction term between collective titles and the proxy for land suitability defined as the area appropriate for producing warm weather, intensive crops in a municipality. In column 4, this variable is defined as a dummy equal to 1 if there is any land suitable to produce these crops in the municipality. The coefficient for the interaction term in columns 3 and 4 is positive and statistically significant. This result indicates that the effect of collective titling on forced displacement is larger for municipalities with higher land productivity (as proxied by the land suitability variable).

Table 3. Fixed-effects estimations.

We perform three robustness checks to test the validity of our estimations. Results of these additional exercises are presented in . First, the use of contemporaneous control variables may be problematic since these variables may be affected by the level of forced displacement in the same year. To address this concern, we estimate the fixed-effects model using the lags of all the control variables (column 1). Second, although it seems reasonable to assume that the effects of collective titles on land reallocation are not necessarily immediate, it may be the case that some illegal armed groups react swiftly to this institutional change. To rule out the possibility that our results depend on the choice of using the lagged collective titles variable, we run the fixed-effects panel estimation using the contemporary collective titles (column 2). Results from these two robustness checks are in line with the previous findings of a positive and significant association of collective titles and forced displacement.

Table 4. Robustness check.

Third, the fact that most collective titles have been granted in the Pacific region, where most Afro-Colombians live, may act as a confounding factor in our estimations.Footnote8 On the one hand, it may be the case that the observed forced displacement is the result of a racist campaign or an attempt to reverse the institutional changes caused by the collective titling program (Ahmed et al. Citation2020). On the other hand, there is evidence that in the last years the conflict has intensified in this area and forced displacement could be the result of the heightened violence in this region (Defensoria del Pueblo Citation2018). To address these concerns, we estimate the model only for the Pacific region. This allows us to compare municipalities that are relatively homogenous in terms of ethnicity but also in terms of geographical and socio-economic characteristics. Results, shown in column 3, are in line with the previous estimations. Our interpretation is that, even in this more uniform group of municipalities, those with collective titles are more affected by forced displacement.

Finally, reports results from a cross-section analysis using the 2014 agricultural census data. In these estimations, the dependent variable is the IDPs expulsion rate in 2015 and the main dependent variable is the productive land under collective tenure in 2014. As mentioned before, the advantage of this variable is that it allows us to capture what we believe is a crucial aspect for our research question: the proportion of productive land (i.e. land that is actually being exploited for any type of production) that is own collectively. Results in column 1 support the idea that collective titles are associated with higher IDPs expulsion rates. This finding is robust to the inclusion of the controls used in the fixed-effects estimations and time-invariant characteristics of the municipality such as altitude, area, and total area devoted to agriculture (column 2). The main results also hold when dummy variables for regions are included (column 3) and when the dependent variable is the IDPs expulsion rate in 2014 (column 4). Results for the fixed effects panel estimations and the cross-section exercise are aligned with the predictions from the theoretical model.

Table 5. Cross-section estimations.

Conclusions

This paper contributes to the literature on the causes of forced migration by proposing an alternative rationale for this phenomenon, namely, that armed groups find it profitable to reallocate land from subsistence to commercial agriculture by evicting peasants from their lands. The case of a large collective titling program in Colombia targeted at Afro-descendants is used to contrast results from the model. Though the program was successful in raising per-capita income, reducing poverty, and increasing residential investment, we believe that it also created, as an unintended consequence, an inefficiency in the land market. While some of the territories occupied by the CCs are potentially very productive, this particular institutional arrangement, among other factors, prevents the communities from using land in a profitable manner. This latent productivity gap can be rationalized in light of the debate about the efficiency of individual vs collective property rights. Although previous works have suggested that individual property rights are more efficient than collective rights (Ostrom and Hess Citation2010; Besley and Ghatak Citation2010), other studies such as Platteau (Citation1996) and De Janvry et al. (Citation2011) have provided arguments against this view. We emphasize that the explanation we propose is one of many potential causes for displacement. Moreover, they are not necessarily mutually exclusive which complicates, even more, the understanding of this phenomenon.

The literature has shown that collective titles have had positive and significant impacts on the well-being of the Afro-Colombian population. The unintended consequence that they have potentially generated (i.e. increase in violence and forced displacement) could be offset by adopting specific measures. First, the government should guarantee that basic public goods are provided for all citizens regardless of their location. The state presence is still weak in most of these municipalities and the public good provision (including security) is scarce. Second, the government could also facilitate the creation of partnerships with private companies. A few positive experiences of associations between CCs and large-scale oil palm producers in municipalities like Tumaco, Guapi, Riosucio and Acandí have been documented (Urrea Citation2012), but the business model could be improved.

The main prediction of the theoretical model is that, under certain circumstances, a gap between the potential and actual productivity of a region is likely to provide incentives for armed groups to reallocate land by forcibly displacing population. In this paper, we focus on the land use transformation related to collective titles in Colombia, but cases of forced displacement associated with an agricultural production gap have also been reported in the West Kalimantan province in Indonesia (Li Citation2017), Cambodia (Sovachana and Chambers Citation2019), Guatemala (Mingorria et al. Citation2014) and Brazil (Pedlowski Citation2013). We also believe that the findings in this paper could enlighten the understanding of cases beyond land reallocation in agriculture such as the forced displacement associated to the exploitation of gold mines in Darfur (Berman et al. Citation2017) or diamonds in Sierra Leone (Marks Citation2019; Voors et al. Citation2017).

This study has two main limitations related to data availability. First, we are not able to directly control for the level of security provided by the State in each municipality. This is a common shortcoming in this type of study since the information about the presence of the State’s security forces is not publicly available due to strategic reasons. To address this concern, we include two control variables, i.e. per-capita income tax and coca cultivated area, that, in our opinion, are highly though imperfectly correlated with State security. Thus, we believe that this limitation does not pose a serious threat to the validity of our findings. Second, although the first collective titles were granted in 1996, our panel starts in 2003 due to data availability. If we included information for the 1996–2002 period, we believe that our results would likely show a larger effect of collective titles on displacement. The reason is that starting in 2002, a new national policy called Seguridad Democrática (Democratic security) placed a greater emphasis on security and deployed more troops in distant areas. In our view, this structural change in the conflict dynamics could be seen as an increase in the cost of committing violent actions, including land grabbing, and forced displacement, for illegal armed groups.

The theoretical model presented here could be extended in two directions. First, our model focuses on reallocation towards legal agribusiness activities. However, land could also be repurposed towards illegal activities. Thus, the model could be extended to capture the trade-offs faced by the armed group regarding the type of activity. Second, our model considers only one illegal group per region. Although the competition among multiple armed groups to capture regional extortion rents is out of the scope of this paper, we believe this is an interesting extension for future research. As far as the empirical exploration, the evidence of land resignations is mostly anecdotical due to lack of data limitations. The lack of a reliable measure of land use over time prevents us from performing a more direct test of the results from the model. We believe that these are all promising avenues for future research.

Notes

2 See for example: https://verdadabierta.com/radiografia-de-las-extorsiones-de-las-farc/, https://www.las2orillas.co/trabajar-para-pagar-la-vacuna-a-las-farc/; https://www.bbc.com/mundo/noticias/2013/12/131101_colombia_extorsion_negocio_gaula_aw

3 See for example https://www.semana.com/nacion/articulo/frente-a-la-situacion-en-ituango-las-reacciones-y-reclamos-invaden-las-redes/202108/, https://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/medellin/ituango-sigue-la-crisis-por-desplazados-en-antioquia-606051, https://www.eltiempo.com/colombia/medellin/desplazamiento-masivo-de-campesinos-en-ituango-por-amenazas-de-clan-del-golfo-465510. The usual response of the government on these notorious cases was to increase military presence.

4 If the armed group obtains revenue from other illegal activities besides extortion, they would likely be even more cautious with the level of displacement since, by attracting attention, they can also jeopardize this additional revenue source.

5 Although land reallocation towards illegal activities is out of the scope of our model, we could nevertheless gain some intuition on the tradeoffs faced by the government under these circumstances. If land is not reallocated towards taxable activities, the left-hand side of the government’s trade-off equation regarding security is reduced since there is no additional taxable output. Thus, the government has less incentives to choose low security.

7 Notice that the variables constructed from the 2014 National Agricultural Census (total area of productive land under collective titling and the total agricultural land area) are only available for that specific year.

8 We thank an anonymous referee for bringing this point to our attention.

References

- Acevedo, Maria Cecilia. 2015. Climate, Conflict and Labor Markets: Evidence from Colombia’s Illegal Drug Production.

- Ahmed, Ali T., Marcus Johnson, Mateo Vásquez-Cortés, Johana Herrera Arango, Guerrero Lovera, Paula Kamila, Guerrero García, and Elías Helo. 2020. “Land Titling, Race, and Political Violence: Theory and Evidence from Colombia.” Working Paper.

- Azam, Jean-Paul, and Anke Hoeffler. 2002. “Violence against Civilians in Civil Wars: Looting or Terror?” Journal of Peace Research 39 (4): 461–485. doi:10.1177/0022343302039004006.

- Balcells, Laia, and Abbey Steele. 2016. “Warfare, Political Identities, and Displacement in Spain and Colombia.” Political Geography 51 (3): 15–29. doi:10.1016/J.POLGEO.2015.11.007.

- Ballvé, Teo. 2013. “Grassroots Masquerades: Development, Paramilitaries, and Land Laundering in Colombia.” Geoforum 50: 62–75. doi:10.1016/J.GEOFORUM.2013.08.001.

- Bandiera, Antonella. 2021. “Deliberate Displacement during Conflict: Evidence from Colombia.” World Development 146 (11): 105547. doi:10.1016/J.WORLDDEV.2021.105547.

- Berman, Nicolas, Mathieu Couttenier, Dominic Rohner, and Mathias Thoenig. 2017. “This Mine is Mine! How Minerals Fuel Conflicts in Africa.” American Economic Review 107 (6): 1564–1610. doi:10.1257/AER.20150774.

- Besley, Timothy, and Maitreesh Ghatak. 2010. “Property Rights and Economic Development.” Handbook of Development Economics 5 (C): 4525–4595. doi:10.1016/B978-0-444-52944-2.00006-9..

- Byrd, William, and Javed Nooran. 2017. Industrial-Scale Looting of Afghanistan’s Mineral Resources. Washington, DC: United States Institute of Peace.

- CNMH (Centro Nacional de Memoria Historica). 2015. Una Nación Desplazada: informe Nacional Del Desplazamiento Forzado en Colombia. Bogotá: Centro Nacional de Memoria Historica. http://www.centrodememoriahistorica.gov.co/descargas/informes2015/nacion-desplazada/una-nacion-desplazada.pdf

- Ch, Rafael, Jacob N. Shapiro, Abbey Steele, and Juan F. Vargas. 2018. “Endogenous Taxation in Ongoing Internal Conflict: The Case of Colombia.” American Political Science Review 112 (4): 996–1015. doi:10.1017/S0003055418000333.

- Collier, Paul. 2000. “Rebellion as a Quasi-Criminal Activity.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 44 (6): 839–853. doi:10.1177/0022002700044006008.

- Davenport, Christian A., Will H. Moore, and Steven C. Poe. 2003. “Sometimes You Just Have to Leave: Domestic Threats and Forced Migration, 1964-1989.” International Interactions 29 (1): 27–55. doi:10.1080/03050620304597.

- De Janvry, Alain, Jean-Philippe Platteau, Gustavo Gordillo, and Elisabeth Sadoulet. 2011. “Access to Land and Land Policy Reforms.” In Access to Land, Rural Poverty, and Public Action, edited by Alain de Janvry, Gustavo Gordillo, Elisabeth Sadoulet, and Jean-Philippe Platteau, 1–26. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Defensoria del Pueblo. 2018. Economías ilegales, actores armados y nuevos escenarios de riesgo en el posacuerdo. Bogotá: Defensoría del Pueblo. https://www.defensoria.gov.co/public/pdf/economiasilegales.pdf.

- DANE (Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística). 2015. Tercer Censo Nacional Agropecuario: Hay campo para todos- Tomo 2. Resultados. Bogotá: Departamento Administrativo Nacional de Estadística. https://www.dane.gov.co/files/images/foros/foro-de-entrega-de-resultados-y-cierre-3-censo-nacional-agropecuario/CNATomo2-Resultados.pdf

- Dueñas, Ximena, Paola Palacios, and Blanca Zuluaga. 2014. “Forced Displacement in Colombia: What Determines Expulsion and Reception in Municipalities?” Peace Economics.” Peace Economics, Peace Science, and Public Policy 20 (4): 1–13. https://ideas.repec.org/a/bpj/pepspp/v20y2014i4p13n9.html.

- Engel, Stefanie, and Ana María Ibáñez. 2007. “Displacement Due to Violence in Colombia: A Household-Level Analysis.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 55 (2): 335–365. doi:10.1086/508712.

- Galvis-Aponte, Luis Armando, Lina Marcela Moyano, and Carlos Alberto Alba Fajardo. 2016. “La persistencia de la pobreza en el Pacífico colombiano y sus factores asociados.” Working paper, Documentos de Trabajo Sobre Economía Regional y Urbana. No. 238. Centro de Estudios Económicos Regionales. Cartagena: Banco de la Republica de Colombia. doi:10.32468/dtseru.238.

- Garfinkel, Michelle R., and Stergios Skaperdas. 2007. “Economics of Conflict: An Overview.” Chapt. 22 In Handbook of Defense Economics: Defense in a Globalized World. Vol. 2, edited by Todd Sandler and Keith Hartley, 649–709. Amsterdam: North Holland. doi:10.1016/S1574-0013(06)02022-9.

- Gómez, Carlos, Luis Sánchez-Ayala, and Gonzalo Vargas. 2015. “Armed Conflict, Land Grabs and Primitive Accumulation in Colombia: Micro Processes, Macro Trends and the Puzzles in between.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (2): 255–274. doi:10.1080/03066150.2014.990893.

- Grajales, Jacobo. 2011. “The Rifle and the Title: Paramilitary Violence, Land Grab and Land Control in Colombia.” Journal of Peasant Studies 38 (4): 771–792. doi:10.1080/03066150.2011.607701.

- Grajales, Jacobo. 2013. “State Involvement, Land Grabbing and Counter-Insurgency in Colombia.” Development and Change 44 (2): 211–232. doi:10.1111/dech.12019.

- Grossman, Herschel. 1999. “Kleptocracy and Revolutions.” Oxford Economic Papers 51 (2): 267–283. doi:10.1093/oep/51.2.267.

- Ibañez, Ana María, and Carlos Eduardo Velez. 2008. “Civil Conflict and Forced Migration: The Micro Determinants and Welfare Losses of Displacement in Colombia.” World Development 36 (4): 659–676. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2007.04.013.

- Justin, Reese. 2012. “Financing the Taliban.” Chap. 7 in Financing Terrorism: Case Studies, edited by Michael Freeman, 93–110. London: Routledge.

- Konrad, Kai I., and Stergios Skaperdas. 1998. “Extortion.” Economica 65 (260): 461–477. doi:10.1111/1468-0335.00141.

- Li, T. 2017. “Intergenerational Displacement in Indonesia’s Oil Palm Plantation Zone.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 44 (6): 1158–1176. doi:10.1080/03066150.2017.1308353.

- Lobo, Ivan, and Maria Alejandra Velez. 2020. “Del liderazgo fuerte a la participación activa: resistencia efectiva a las economías ilícitas en territorios colectivos de comunidades afrocolombianas [From Strong Leadership to Active Community Engagement: Effective Resistance to Illicit Economies in Afro-Colombian Collective Territories]”, Working paper, Documento CEDE No. 3. Centro de Estudios sobre Desarrollo Economico. Bogotá: Universidad de los Andes. doi:10.2139/ssrn.3545950.

- Lozano-Gracia, Nancy, Gianfranco Piras, Ana Maria Ibáñez, and Geoffrey J. D. Hewings. 2010. “The Journey to Safety: Conflict-Driven Migration Flows in Colombia.” International Regional Science Review 33 (2): 157–180. doi:10.1177/0160017609336998.

- Maher, David, and Andrew Thomson. 2018. “A Precarious Peace? The Threat of Paramilitary Violence to the Peace Process in Colombia.” Third World Quarterly 39 (11): 2142–2172. doi:10.1080/01436597.2018.1508992.

- Maher, David. 2015. “Rooted in Violence: Civil War, International Trade and the Expansion of Palm Oil in Colombia.” New Political Economy 20 (2): 299–330. doi:10.1080/13563467.2014.923825.

- Marks, Zoe. 2019. “Rebel Resource Strategies in Civil War: Revisiting Diamonds in Sierra Leone.” Political Geography 75 (11): 102059. doi:10.1016/J.POLGEO.2019.102059.

- Mingorria, Sara, Gonzalo Gamboa, Berta Martín-López, and Esteve Corbera. 2014. “The Oil Palm Boom: Socio-Economic Implications for Q’eqchi’ Households in the Polochic Valley, Guatemala.” Environment, Development and Sustainability 16 (4): 841–871. doi:10.1007/s10668-014-9530-0.

- Ministerio de Defensa. 2021. Logros de La Política de Defensa Y Seguridad. Bogotá. https://www.mindefensa.gov.co/irj/go/km/docs/Mindefensa/Documentos/descargas/estudios_sectoriales/info_estadistica/Logros_Sector_Defensa.pdf.

- Oslender, Ulrich. 2007. “Violence in Development: The Logic of Forced Displacement on Colombia’s Pacific Coast.” Development in Practice 17 (6): 752–764. doi:10.1080/09614520701628147.

- Ostrom, Elinor, and Charlotte Hess. 2010. “Private and Common Property Rights..” Chapt 4 in Property Law and Economics, edited by Boudewijn Bouckaert. Northampton: Edward Elgar Publishing. doi:10.4337/9781849806510.00008.

- Palacios, Paola. 2011. “Forced Migration as a Deterrence Strategy in Civil Conflict.” In Contributions to Conflict Management, Peace Economics and Development, 17:1–22. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Palacios, Paola. 2012. “Forced Migration as a Deterrence Strategy in Civil Conflict.” In Contributions to Conflict Management, Peace Economics and Development, edited by Raul Caruso, 17:1–22. Bingley: Emerald Group Publishing Limited. doi:10.1108/S1572-8323(2011)0000017005.

- Pedlowski, Marcos A. 2013. “When the State Becomes the Land Grabber: Violence and Dispossession in the Name of ‘Development’ in Brazil.” Journal of Latin American Geography 12 (3): 91–111. doi:10.1353/lag.2013.0045.

- Peña, Ximena, María Alejandra Velez, Juan Camilo Cárdenas, Natalia Perdomo, and Camilo Matajira. 2017. “Collective Property Leads to Household Investments: Lessons from Land Titling in Afro-Colombian Communities.” World Development 97 (11): 27–48. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2017.03.025.

- Platteau, Jean Philippe. 1996. “The Evolutionary Theory of Land Rights as Applied to Sub-Saharan Africa: A Critical Assessment.” Development and Change 27 (1): 29–86. doi:10.1111/j.1467-7660.1996.tb00578.x.

- Porch, Douglas, and María José Rasmussen. 2008. “Demobilization of Paramilitaries in Colombia: Transformation or Transition?” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 31 (6): 520–540. doi:10.1080/10576100802064841.

- Potter, Lesley. 2020. “Colombia’s Oil Palm Development in Times of War and ‘Peace’: Myths, Enablers and the Disparate Realities of Land Control.” Journal of Rural Studies 78 (8): 491–502. doi:10.1016/J.JRURSTUD.2019.10.035.

- Richani, Nazih. 2005. “Multinational Corporations, Rentier Capitalism, and the War System in Colombia.” Latin American Politics and Society 47 (3): 113–144. doi:10.1111/j.1548-2456.2005.tb00321.x.

- Sabates-Wheeler, Rachel, and Philip Verwimp. 2014. “Extortion with Protection: Understanding the Effect of Rebel Taxation on Civilian Welfare in Burundi.” Journal of Conflict Resolution 58 (8): 1474–1499. doi:10.1177/0022002714547885.

- Sánchez-Ayala, Luis, and Cindia Arango-López. 2015. “Against All Odds, I Am Here: Territory and Identity in San Cristobal, Montes de Maria.” Latin American Research Review 50 (3): 203–224. doi:10.1353/lar.2015.0047.

- Shire, Mohammed Ibrahim. 2021. “Protection or Predation? Understanding the Behavior of Community-Created Self-Defense Militias during Civil Wars..” Small Wars & Insurgencies Advance online publication. doi:10.1080/09592318.2021.1937806.

- Sovachana, Pou, and Paul Chambers. 2019. “Human Insecurity Scourge: The Land Grabbing Crisis in Cambodia.” In Human Security and Cross-Border Cooperation in East Asia, edited by Carolina G. Hernandez, Eun Mee Kim, Yoichi Mine and Ren Xiao, 181–203. London: Palgrave Macmillan. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-95240-6_9.

- Steele, Abbey. 2017. Democracy and Displacement in Colombia’s Civil War. New York: Cornell University Press.

- Thomson, Frances. 2011. “The Agrarian Question and Violence in Colombia: Conflict and Development.” Journal of Agrarian Change 11 (3): 321–356. doi:10.1111/j.1471-0366.2011.00314.x.

- UNHCR (United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees). 2021. “Global Trends Forced Displacement in 2020.” https://www.unhcr.org/statistics/unhcrstats/60b638e37/global-trends-forced-displacement-2020.html

- Urrea, Fernando. 2012. Afrocolombianos: Sus Territorios y Condiciones de Vida. Bogotá: PNUD.

- Velez, Maria Alejandra, Juan Robalino, Juan Camilo Cardenas, Andrea Paz, and Eduardo Pacay. 2020. “Is Collective Titling Enough to Protect Forests? Evidence from Afro-Descendant Communities in the Colombian Pacific Region.” World Development 128 (April): 104837. doi:10.1016/j.worlddev.2019.104837.

- Velez, Maria Alejandra. 2011. “Collective Titling and the Process of Institution Building: The New Common Property Regime in the Colombian Pacific.” Human Ecology 39 (2): 117–129. doi:10.1007/s10745-011-9375-1.

- Velez, María Alejandra. 2001. “FARC – ELN: Evolución y Expansión Territorial.” Revista Desarrollo y Sociedad 47 (47): 151–225. doi:10.13043/DYS.47.4.

- Voors, Maarten, Peter Van Der Windt, Kostadis J. Papaioannou, and Erwin Bulte. 2017. “Resources and Governance in Sierra Leone’s Civil War.” The Journal of Development Studies 53 (2): 278–294. doi:10.1080/00220388.2016.1160068.