ABSTRACT

Higher education in the Netherlands has expanded rapidly in the last two decades, giving rise to concerns about possible negative effects on educational quality and the labour market value of a higher education degree. In this paper, we use data from national graduate surveys and adult literacy surveys to explore this. While no evidence was found for a negative effect of the HE expansion on graduate skill levels or unemployment risk, real graduate earnings have decreased over the past two decades relative to those of post-secondary non-tertiary graduates. This does not seem to have been driven by a shift of HE graduates into non-graduate occupations, but rather by a general decline in relative earnings in jobs at all levels. Finally, the more adverse effects of the expansion were particularly apparent for graduates with lower grades, women and graduates with a non-western migration background. These findings indicate that, despite relatively low unemployment, the HE labour market is increasingly becoming a buyers’ market. In this market, graduates with attributes that buyers want – males, native Dutch graduates, high-performers – emerge as relative winners of the educational expansion.

Introduction

As in most industrialised countries, having a higher education (HE) degree in the Netherlands has gone from being a rarity to being quite unremarkable. Whereas HE was only accessible to privileged white males a century ago, it became an institution for the masses during the second half of the twentieth century (Batenburg & de Witte, Citation2001; Van der Ploeg, Citation1994; Wolbers, De Graaf, & Ultee, Citation2001). Most see the expansion of HE as a positive development that has improved human life, through private and social-economic returns, and by making work less physically demanding (Horowitz, Citation2018; Levy & Murnane, Citation1992).

There may however be a downside to the educational expansion. Many authors have pointed to the potential problems that may ensue when HE changes from an elite system to a mass form of education, including pressure on educational quality and the potential devaluation of an HE degree in the labour market (Battu, Belfield, & Sloane, Citation2000; Bol, Citation2015; Figueiredo, Teixeira, & Rubery, Citation2013; Green & Zhu, Citation2010; Mayhew, Citation2016; Mok & Neubauer, Citation2016). Already in the 1970s, the economist Fred Hirsch pointed out that, like many of the trappings of social and economic progress, an HE degree is largely a positional good: the more people who have one, the less it is worth (Hirsch, Citation2015).Footnote1 There is a longstanding debate as to whether HE supply is actually outpacing demand (Brown, Lauder, & Ashton, Citation2011; Figueiredo, Biscaia, Rocha, & Teixeira, Citation2017; Schomburg & Teichler, Citation2006). If so, this could lead to rising graduate unemployment, decreasing earnings returns, and a virtual job queue for the best positions (Thurow, Citation1975). In this type of situation, one could imagine that some categories of graduates – for example those with lower grades, females, or immigrants – might get pushed towards the back of the queue (Horowitz, Citation2018).

The present study investigates how the HE expansion in the Netherlands has affected the average skill levels and labour market outcomes of HE graduates during the past two decades, and how such changes have varied by type of HE programme, grade point average (GPA), gender, and migration background. As such, we add to the current literature on educational expansion in at least three ways. Firstly, since the last Dutch overview studies on this topic stem from the early 2000s (e.g. Batenburg & de Witte, Citation2001; Wolbers et al., Citation2001), our study provides more current insights into how the ongoing expansion in the last two decades has affected graduates’ early careers. Secondly, by focussing on multiple outcomes (i.e. graduate skill levels, unemployment, earnings, and job levels) we provide a more balanced picture of the impact of educational expansion than most existing studies offer. Finally, while most overview studies on educational expansion have focussed on general effects only, we also analyse possible differential effects by GPA, gender and migration background.

Theoretical background

Changes in the value of an HE degree in recent decades

Many recent studies provide evidence that HE degrees are losing their value over time. For example, it has been found that HE jobs are rewarded less today in monetary terms (Bol, Citation2015; Figueiredo et al., Citation2013), that HE graduates’ skills are being utilised less (Battu et al., Citation2000; Green & Zhu, Citation2010), and that HE graduates are increasingly crowding out secondary school leavers by entering non-graduate jobs (Boylan, Citation1993; Gesthuizen & Wolbers, Citation2010; Horowitz, Citation2018).

However, other studies have offered evidence that the monetary returns to HE degrees are increasing rather than decreasing, due to the so-called ‘skill-biased technological change’ (SBTC). The SBTC refers to the major technological improvements and productivity gains that have taken place in the late twentieth century and that have supposedly led to a greater demand for high-skilled HE graduates (Krueger, Citation1993; Levy & Murnane, Citation1992). Goldin and Katz (Citation2008), Autor, Katz, and Kearney (Citation2008) and others found evidence for such a change, showing increasing returns to education for recent birth cohorts of HE graduates compared to older cohorts.

There is however, some discussion as to how general these changes are. Some studies have found that such technology-driven gains were only available to a relatively small subpopulation of HE graduates such as managers and IT analysts (Mouw & Kalleberg, Citation2010), and others doing work requiring high analytical skills (Liu & Grusky, Citation2013). However, the observed returns could also have been the result of other changes that have taken place in the past century, such as a more general economic growth, improved fiscal policies, and stronger labour unions. In addition, since SBTC is often associated with polarisation between low- and high-skilled jobs, HE graduates could be at risk of sliding down the occupational hierarchy, if the pool of HE graduate jobs lagged behind demand (Autor, Citation2014; Kalleberg, Citation2011).

Changes in the value of an HE degree for specific societal groups

As HE credentials have become increasingly common, employers may turn to additional productivity signals to decide which graduates get to stand at the head of the labour queue such as grades, social networks, personality traits and study and work preferences (Goldthorpe, Citation2014; Horowitz, Citation2018; Keep & Mayhew, Citation2014; Tomlinson, Citation2008). This is simple market economics, and is often rational and legitimate. However, it becomes problematic when a choosy attitude on the part of employers systematically puts particular societal groups at a disadvantage. The potential for such discrimination, statistical or otherwise, may be more acute for groups who until recently were underrepresented in HE, such as females and people with a migration background. In addition to a possible preference by employers for the ‘devil they know’ (i.e. white males), female and minority HE graduates may face the same hurdles as females and minorities do in the labour market in general (Mooi-Reci & Muñoz-Comet, Citation2016; Stier & Herzberg-Druker, Citation2017). For women, these include statistical discrimination based on anticipated productivity loss related to childbearing (Bütikofer, Jensen, & Salvanes, Citation2018), problems with breaking into the high paying high-tech industries dominated by men (Jacobs, Citation1995), and the lower value placed on typical female professions (e.g. nurses, teachers, etc.) (Marini & Fan, Citation1997). For minorities, problems include lack of familiarity with the host country language and customs, less valuable social networks, and problems with integrating into the host country (Kislev, Citation2016). In both cases, there is also the possibility that employers simply indulge what Becker (Citation1957) called a ‘taste for discrimination’. Quasi-experimental research has shown that many employers indeed prefer males above females and native above migrant workers with similar résumés (Liebkind, Larja, & Brylka, Citation2016). This has been found to result in higher unemployment rates of female and non-western HE graduates compared to their male and native counterparts (Brekke, Citation2007; Brekke & Mastekaasa, Citation2008; Laurison & Friedman, Citation2016; Zwysen & Longhi, Citation2018).

The Dutch higher education system and its expansion

General structure, entry rules and student financing

The Netherlands has a binary system of HE, consisting of 13 academic universities (henceforth universities) and 41 universities of applied sciences (henceforth HBO institutions). Both types of HE institution offer studies in a broad and largely overlapping range of fields, but differ quite strongly in focus and entry requirements. Academic universities have a stronger focus on scientific research, while HBO institutions are more practical and vocationally oriented. As Dutch HE is strongly standardised, there are only few quality differences between institutions within each of these HE types.

For the most part, entry to Dutch HE is based on one of the two highest forms of general secondary education available in the Netherlands: pre-university secondary education (voorbereidend wetenschappelijk onderwijs or VWO) and senior general secondary education (hoger algemeen voortgezet onderwijs or HAVO). Selection into these two types of secondary education, as well as into lower types of general secondary education and secondary vocational education (both the classroom-based beroepsopleidende leerweg or BOL and the workplace-based beroepsbegeleidende leerweg or BBL), takes place at age 12. This means that the initial decision to enter HE is taken at a very young age, although there are ample opportunities to change track at later stages. Entry to academic universities is very selective and only eligible for students who completed VWO or at least the first year of an HBO programme. HBO institutions are less selective, and can also be accessed by students who completed HAVO or the highest tier of BOL or BBL (BOL-4/BBL-4).

The introduction of a bachelor-master structure in line with the Bologna Process in 2001 has led to a multiplication of the number of Dutch HE degree types (see Online Appendix Figure A1). At academic universities, the old single-stage four-year doctoral degree was replaced by a three-year academic bachelor’s programme, optionally (and in practice usually) followed by a one- or two-year master’s degree. The pre-Bologna HBO degrees were retained, but formally redesignated as four-year vocational bachelor’s degrees. Bachelor’s graduates from both types of HE may proceed to a master’s programme at either an HBO institution or a university. In practice, relatively few HBO bachelors (around a quarter) choose to do so, and less than one in ten follows a master’s programme at a university. By contrast, most university bachelors (80–85%) continue to a master’s level, almost always at a university (Inspectorate of Education, Citation2013). For this reason, HBO master’s and university bachelor’s programmes are excluded from the analyses presented in this paper, as are the new and numerically small two-year associate degree programmes that were designed to bridge the perceived gap between upper secondary and tertiary education.

Thus, in the present study, we focus on the two most prevalent degrees in Dutch HE, both before and after the Bologna process, namely the HBO bachelor’s degree and the university master’s degree (including their pre-Bologna equivalents). The number of graduates of both degree types has increased sharply in the past four decades. In numerical terms, the increase has been comparable, but in relative terms the expansion in university masters has been more dramatic, representing roughly a quadrupling since the early eighties (Statistics Netherlands, Citation2019). In this study, we will compare the returns of these two HE degree types with those of the BOL-4 degree, as this degree is closest to the educational level of HBO bachelors and therefore provides the best benchmark against which relative value of an HE diploma can be assessed.

Starting in 1986 all Dutch students were eligible for a basic allowance to cover their tuition fees and basic living costs. Initially, this was not dependent on the student’s performance, but starting in 1993, it became a conditional gift to be repaid if the student failed to obtain sufficient credits each study year. As of the academic year 2015/2016, the basic grant was replaced by a ‘social loan’, to be paid back in full at below-market interest rates (Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science, Citation2019). Since the first cohorts falling under this new social loan system have yet to enter the labour market in meaningful numbers, there is little reason to expect this change has affected the results we present. However, the manner in which the new rules were applied in anticipation of the introduction of the social loan system may have slowed down the proportion of HBO graduates continuing on to a university master’s degree.

Changes in composition

The expansion of Dutch HE is not just a matter of ‘the same as before, only more’. The student composition of HE has changed as well. See Online Appendix Table A1 for an overview of some of the most important changes.

In 2016–2017, an increasing proportion of graduates entered HBO bachelor’s programmes via the designated route of HAVO as compared to two decades earlier (+13%-points), while noticeably fewer students entered HBO via the VWO route than before (−12%-points). The proportion entering HBO via senior vocational secondary education decreased a little (−5%-points), while the proportion entering via other routes (largely foreign qualifications) almost doubled (+4%-points). In university master’s programmes, the proportion of graduates who entered via the designated academic track (VWO) roughly decreased in 2016–2017 as compared to the previous two decades (−17%-points), while considerably more graduates entered through HBO bachelor’s programmes than before (+11%-points). As in HBO, also at academic universities the proportion of graduates who entered via other routes almost doubled (+6%-points) between the late nineties and the mid-2010s.

Furthermore, between 1996 and 2017, a stable proportion of around a third of HBO bachelors and half of university masters followed programmes in the fields of economics, society and law. At the HBO bachelor’s level, the share of degrees in science, technology and agriculture dropped by approximately 5%, while that of health and welfare increased by a comparable amount. The distribution of degrees across broad fields at university master’s level changed only very little.

By the mid-nineties, female graduates already outnumbered male graduates at HE institutions. The proportion of females has continued to increase, and comprised almost 60% of HBO bachelors and 56% of university masters in graduation years 2016–2017. Arguably, the greatest change in composition has been in the proportion of graduates with a migration background. We follow the distinction developed by Statistics Netherlands (Citation2019) into western and non-western backgrounds,Footnote2 and draw an additional distinction between first generation (graduates who were born abroad) and second generation (born in the Netherlands to foreign-born parents). The proportions of both groups graduating from HE have increased considerably in the past two decades, especially for first-generation migrants graduating with a university master’s degree. Foreign-born students remain relatively rare at HBO bachelor’s level, although the proportions have increased appreciably. At both HE levels, the proportion of second-generation non-western graduates rose steadily in the first decade and a half of this century before dropping to around 3% of all HBO bachelor’s and university master’s graduates in the last two years. The proportions of graduates with a second-generation western background has declined very slightly at both levels to around 3–4% of all graduates.

These figures are at least a little misleading, because the proportion of young people with a migration background in the Dutch population as a whole has also increased over time (Statistics Netherlands, Citation2019). To see how relative graduation opportunities have changed over time, we therefore look at the trend in attainment of an HE degree among young people with a migration background, as compared to the same trend for young people with a native Dutch background (see Online Appendix Figure A2). As can be seen, at both HE levels, young people with a non-western background continue to lag behind native Dutch and migrants with a western migration background. Particularly at university master’s level, the gap with respect to native Dutch young people is large and widening.

During the past two decades, there have been some significant shifts in the composition of origin countries within these broad categories. As the children of former immigrants are now themselves graduating from HE, large origin countries such as Surinam, Turkey and Morocco figure more and more as second-generation origin countries. Meanwhile, China has emerged as an important first-generation origin country, especially among university masters, signalling the growing importance of the global HE market. Furthermore, Germany has remained the dominant origin country of first-generation western immigrants, while fellow Belgium has become less significant.

Data and methods

The present study uses multiple data sources to analyse how the skills and labour market outcomes of Dutch HE graduates have developed over the past two decades. For the analysis of literacy skills, we use data from the OECD’s Programme for the International Assessment of Adult Competencies (PIAAC, 2012) studies and the earlier comparable International Adult Literacy Survey (IALS, 1994). For the analyses of ICT and field-specific skills and labour market returns, we use the yearly graduate and school-leaver surveys run and/or administered by the Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market (ROA) of Maastricht University. These surveys have been held from the mid-1990s onwards, and make it possible to study trends in graduate labour market returns over time. They provide information on graduates’ first experiences in the labour market, one to two years after graduation, as well as their skill levels and background information such as age, gender and migration background. The HBO graduate survey (the HBO-Monitor) has been held yearly since 1996. The university graduate survey (Nationale Alumni Enquête or NAE) was held yearly from 1998 to 2009, and once every two years since 2011. For comparison, we use data on BOL-4 graduates from the School-leaver Information System (SIS, also held yearly since 1996).

In using these datasets, we consciously focus on recent young graduates of completed initial education. As such, we are aware that we thereby place some limits on the type of conclusions that can be drawn from our results, particularly in terms of longer-term outcomes. However, we believe that the choice is justified, since long-term outcomes are less current and potentially more co-determined by broader labour market processes than the outcomes of recent graduates. With this in mind, and in the interest of eliminating effects of atypical educational careers, we limit the analyses to graduates of full-time study programmes who did not proceed to further education. Furthermore, the analyses are also limited to graduates who at the time of the survey were no more than 10 years older than the median age of graduates at their own level (21 for BOL-4 graduates, 24 for HBO bachelors and 26 for university masters). Analyses on the full dataset (available on request) reveal that these selections do not change the basic pattern of results, although the exact size of the estimates does change. To avoid confounding our results with the effects of different currencies and purchasing powers, we further limited all earnings analyses to graduates working in the Netherlands at the time of the survey.

provides a descriptive overview of the outcomes and control variables included in the labour market and skills analyses. As can be seen, among all three types of graduates, the unemployment rate is the same, namely 4%. Furthermore, HBO bachelors most often have a job that matches their educational level and/or their study field. By contrast, over a third of university masters holds a job below their own educational level. All three graduate types are further characterised by a slightly higher percentage of female than male graduates. Further, most respondents had a Dutch native background (82%-88%) with an average age of between 23 and 27.

Table A1. Descriptives of variables in graduate survey datasets 1996–2017

Dependent on the outcome variable, linear or logistic regression analyses were performed to analyse differences between different cohorts and graduates of different education levels (i.e. BOL-4, HBO bachelor, and university master). General models containing all three types of education were run to assess the returns to HBO bachelors and university masters degrees relative to a BOL-4 degree. In order to investigate the possible differential returns to education by GPA, gender, and ethnic background, separate models were run for HBO bachelors and university masters. All analyses contain controls for gender, age (linear and quadratic) and region of study. Where appropriate and feasible we used additional control variables for some analyses. The precise set of control variables is described when introducing each set of analyses.

Results

We first analyse how the expansion has affected the quality of HE in terms of graduate skill levels. Next, we investigate how the expansion affected the labour market returns of HE degrees in terms of employability, hourly wage, and job level. Finally, we examine whether expansion has differentially affected the skill development and labour market returns of graduates with high versus low grades, men versus women and native graduates versus graduates with a non-western migration background.

Effects of educational expansion on HE graduate skill levels

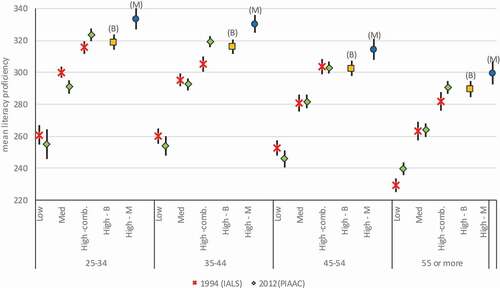

Shifts in general literacy skills

shows the average literacy levels of Dutch adults in the years 1994 and 2012, by age and educational level. Higher education comprises mainly HBO bachelors and university masters, which are shown separately in 2012. Medium education consists mainly of senior secondary vocational (BOL or BBL) graduates, since few people leave initial education with only general senior secondary education.

Figure 1. Adult literacy skill levels in the Netherlands in 1994 and 2012, by age group and highest attained education.

If, as some fear, the expansion and accompanying ‘massification’ of HE has diminished the value of an HE degree in terms of graduate skills, we would expect a narrowing of the skills gap between HE and lower levels of education over time. However, as shows, the skill gap in terms of adult literacy has, if anything, increased from the mid-1990s through the first decade of this century. Particularly for the youngest two age cohorts, who left education relatively recently, the difference in literacy skills between high and medium education has widened, while the gap between medium and low education has remained more or less constant. This is an important result: in a period in which the number of graduates of HBO bachelor’s and university master’s programmes increased by 22% and 31%, respectively, the skill difference between upper secondary and tertiary educated young adults became larger. This result suggests that the expansion has not eroded the relative advantage of HE graduates in terms of skills.

Shifts in field-specific knowledge

Differences in literacy skills are interesting, and may proxy a broader range of skills and abilities, but these are not the main field-specific skills that students are supposed to learn as preparation for the labour market. To get more insight in this, Online Appendix Figure A3 shows changes that have taken place between 2004 and 2017 in self-reported field-specific knowledge of recent HE graduates.Footnote3 Especially for HBO bachelors, both the own level of knowledge and the level required in the job have increased steadily in this period, while for university masters the levels have remained fairly constant. The required level of field-specific knowledge also varies with the economic cycle, with an increased demand of these skills in boom years and a lower demand during recessions. Consequently, graduates are more likely to be under-skilled in boom years and over-skilled during recessions.

Shifts in ICT skills

Online Appendix Figure A4 shows how own and required ICT skills have changed between 2004 and 2017. As can be seen, the required level of ICT skills has increased more rapidly than graduates’ own skill level, suggesting that graduates are being more often challenged to use their ICT skills in their work now than they were 15 years ago. HE graduates still have more ICT skills on average than is needed in their work, probably because these skills are widely used and developed in everyday life. The gap between required and own ICT-skill level is however closing, suggesting that the existing ICT-skills of graduates are being better used in the labour market.

Effects of educational expansion on HE graduates’ labour market returns

Even if the educational expansion in the Netherlands has not eroded the skill levels of the graduate labour force, it could still have diluted the economic value of holding such skills if demand had not kept up with the increasing supply. To investigate this, we examined the evolving patterns of unemployment levels, earnings and job levels of Dutch HE graduates, using BOL-4 graduates as a point of comparison.Footnote4

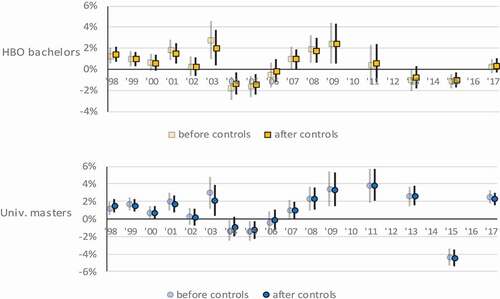

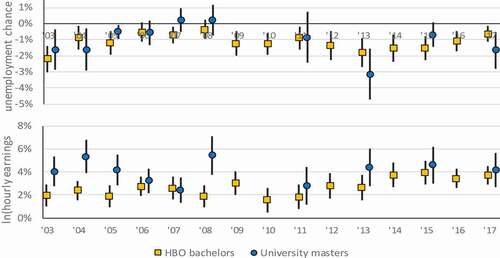

Unemployment

Between 1996 and 2017, unemployment levels of both secondary and tertiary graduates have varied strongly (see Online Appendix Figure A5). BOL-4 graduates especially are strongly affected by the economic cycle, with close to zero unemployment in boom years and much higher unemployment during recessions. Nonetheless, university masters were hardest hit by the 2008 global financial crisis whose effects were felt in the Netherlands until at least 2015. HBO graduates showed the most stable employment levels over time, although they also felt the effects of economic downturns.

further shows that the greater sensitivity of BOL-4 graduates to the economic cycle appears to be the main driver behind the changes in the unemployment risk of HBO bachelors and university masters relative to BOL-4 graduates. Whereas employers seemingly cannot get enough of the vocational skills of BOL4 graduates when the economy is booming, they lose much of their appeal during recessions. Tertiary-educated graduates however generally retain much of their strong labour market position even in a downturn. Despite the fluctuations, HBO bachelors and university masters show higher unemployment levels than BOL-4 graduates in most years, with an advantage over BOL-4 graduates only at the lowest points of economic downturns. As further shows, controls barely have any effect on this.

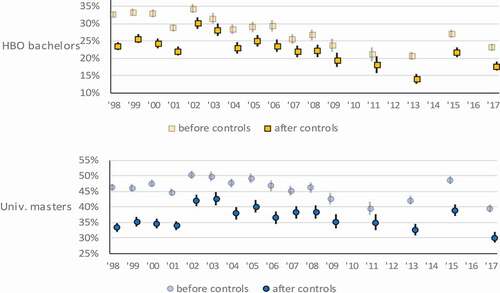

Earnings

A tertiary degree thus acts as a ‘shock absorber’ during economic downturns, but does not otherwise help graduates’ relative employment chances. Average real earnings differences relative to BOL-4 are very substantial (see Online Appendix Figure A6). Strikingly however, little has changed throughout time at all three levels in structural terms. Real (inflation-adjusted) earnings rise and fall over time, but if there is any long-term trend for HBO bachelors and university masters, it is in a downward direction. Only BOL-4 graduates’ earnings show some modest signs of improvement over time.

As shows, this has led to a drop in earnings of recent HBO bachelors and university masters graduates relative to BOL-4 graduates. Furthermore, after accounting for the control variables, the earnings difference compared to BOL-4 is consistently lower than the raw differences would suggest. This adjustment appears to be almost entirely due to the fact that HBO bachelors and university masters are substantially older than BOL-4 graduates. The adjustment is even larger during economic downturns, because the earnings of older workers are less sensitive to the economic cycle than those of younger workers.

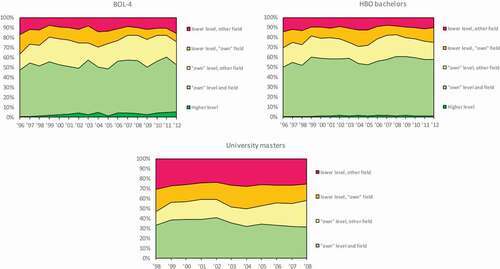

Job levels

Relative to BOL-4 graduates, we thus see a stable or even increasing skills advantage for HE graduates, accompanied by stagnating absolute earnings and a decreasing earnings gap. A plausible explanation for this apparent discrepancy is that the educational expansion has resulted in an oversupply of HE graduates, and that wages have therefore been driven down by market forces. If so, a question that is still unanswered is whether HE graduates have been moving into occupations previously considered to be non-graduate jobs, or whether the changes in relative earnings have taken place mainly within existing graduate occupations. In this section, we address this issue.

first of all shows the trend in the percentage of BOL-4, HBO bachelor and university master graduates working in occupations that are: (1) at a higher level than would normally be designated to their education (only BOL-4 and HBO bachelors); (2) match their ‘own’ level and field; (3) match their own level, but a different field; (4) match their own field but at a lower level; and (5) are at both a lower level and in a different field.

Figure 4. Education-occupation match, by broad level of education, 1996–2017.

Remarkably, there does not seem to be any systematic shift of graduates at any of the three levels into lower level occupations, just some cyclical fluctuations. There does however seem to be a trend towards a decreasing proportion of graduates working in lower level occupations. University masters show the highest proportion of graduates working in occupations that would normally be designated to lower levels of education, although it should be noted that these are almost always HBO bachelor-level jobs, and therefore still classified as graduate jobs.

All in all, the proportion of graduates working in graduate occupations at their own level is fairly stable, with no discernible trends suggestive of an overcapacity of graduates forcing them into lower level jobs. Earnings of HBO bachelors working in jobs matching both the level and field of their education have been relatively stable since climbing to roughly their current level in the late 1990s (see Online Appendix Figure A7). The small number of graduates working in higher level jobs are well rewarded for this, while graduates working in lower level jobs pay a large and – especially for those whose job also fails to match the study field – increasing earnings penalty. Graduates working at their own level but a different field earn roughly the same as those whose job matches both the level and field of their education. University masters working in jobs matching the level and field of their study did experience a solid earnings growth up until the eve of the recent crisis. However, there is a severe and increasing penalty for working at a lower level (see Online Appendix Figure A8).

Differential effects of educational expansion on labour market returns of specific groups of HE graduates

Although an HE degree still confers clear benefits compared to BOL-4, real earnings are stagnating and the earnings gap is closing over time. Despite a dampening effect on the impact of economic downturns, there is also no structural benefit in terms of employment prospects. An important remaining question is whether the growing precariousness affects all graduates equally, or whether some groups are more exposed to the vagaries of the labour market than others. If supply is indeed growing faster than demand, employers might be in a position to be more selective. This could be based on additional indicators of human capital, such as grades, but also on personal or background characteristics such as gender and migration background. In order to determine this, we conducted separate analyses to assess unemployment and earnings trends of HBO bachelors and university masters separately by GPA, gender and migration background.

Differences in employment chances and earnings by GPA

shows the effect of an additional point in the average final grades achieved by graduates (measured on a 10-point scale, with 6 the minimum passing grade and 10 the maximum achievable grade) on the unemployment risk and earnings of graduates. As can be seen, in general, higher grades are associated with a reduced risk of unemployment, as well as a substantial earnings premium. The graph shows that these benefits drop in boom years and increase markedly during economic downturns, suggesting that employers choose the highest performers when they can, but are less able to be choosy when the market tightens.

Figure 5. Effects of average final grades on labour market outcomes 1–2 years after graduation, HBO bachelors and university masters, 2003–2017.

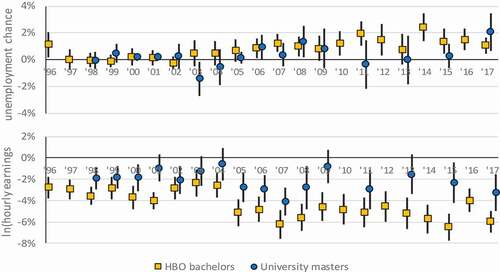

Gender differences in employment chances and earnings

shows how the chance of unemployment and earnings of female HBO and university graduates varies compared to males at the same level of education. As can be seen, especially female HBO graduates are at a considerable disadvantage compared to males, and that this disadvantage is increasing over time. The pattern is similar for female university graduates, but less pronounced. In the late 1990s and the early 2000s, the unemployment levels of female graduates at both HBO bachelor’s and university master’s level were roughly comparable to those of males, but in recent years, the unemployment gap has widened substantially. Gender differences in earnings were relatively modest around the turn of the millennium, but have become much larger in the last decade or so.

Figure 6. Effects of gender (females versus males) on chance of being unemployed and earnings 1–2 years after graduation, 1998–2017.

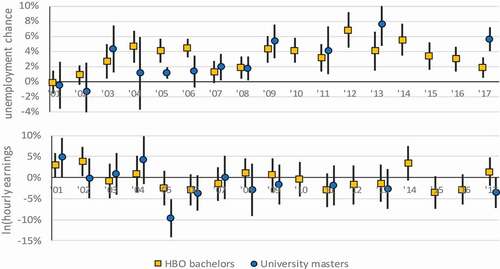

Ethnic differences in employment chances and earningsFootnote5

shows the unemployment risk and earnings of HBO bachelors and university masters graduates with a first-generation non-western migration background (i.e. born outside the Netherlands, in a non-western country), relative to comparably educated native Dutch graduates.Footnote6 As can be seen, especially in terms of unemployment risk, non-western graduates are at a clear and growing disadvantage, especially during economic downturns. In most years, there is no significant difference in terms of earnings, although here as well there appears to be a slight downward trend.

Figure 7. Effects of a first-generation non-western migration background (versus native Dutch) on labour market outcomes 1–2 years after graduation, HBO bachelors and university masters, 2001–2017.

The trend in unemployment risk and earnings of graduates with a second-generation migration background (i.e. born in the Netherlands to parents born in a non-western country) strongly mirror those of immigrants of the first generation (see Online Appendix Figure A9). Earnings of this group seem to be more clearly influenced by the conjunctural cycle, dropping in periods of low conjuncture and rising to levels comparable or even somewhat better than native Dutch graduates in boom years.

Discussion

This study used data from several long-running Dutch graduate surveys, supplemented by data from adult literacy surveys conducted from the 1990s to the 2010s, to assess the effects of the educational expansion that has taken place within the past two decades on the value of an HE degree in the Netherlands. Specifically, we looked at effects on graduate skill levels and labour market returns, and enquired whether specific subpopulations have emerged as ‘winners’ or ‘losers’ as a result of the educational expansion.

Contrary to earlier findings in Britain (Battu et al., Citation2000; Green & Zhu, Citation2010), we could not find any evidence that the expansion of HE has resulted in an erosion of graduate skills in the Netherlands. Quite the reverse: if anything the average literacy skill levels of young Dutch people with HE degrees have increased relative to those educated at upper secondary level. HE graduates’ self-reported field-specific knowledge and ICT skills have also risen in the last decade and a half. We cannot firmly establish the mechanisms for these developments, which are probably the result of both selection – a rising proportion of highly skilled people entering HE – and learning effects – more skills being learned in HE. Either way, these results suggest that Dutch HE has been able to expand while maintaining a high level of quality in terms of graduate skills. Our finding that the required level of ICT skills has been rising quickly in graduate jobs is consistent with the theory that increased supply has enhanced demand through skills-biased technological change. Although we cannot demonstrate a causal link, it is reasonable to assume that such innovations would have been difficult if graduates did not already possess the requisite skills. There is also no evidence of a shift by graduates into non-graduate occupations, suggesting that demand in terms of the number of graduate jobs has grown over time to accommodate increasing supply. Yet, our analysis of graduate earnings do suggest that the expansion has had some negative effects on the labour market value of an HE degree. Although the general earnings stagnation that has affected graduates at all levels is probably a symptom of the decoupling of GDP growth that many industrialised countries have grappled with in recent decades (OECD, Citation2018), the decline in HE graduate earnings relative to those of BOL-4 graduates is consistent with an increasing relative surplus of HE graduates.

Another interesting finding was that the primary effect of an HE degree – as compared to a BOL-4 degree — is that it acts as a ‘shock absorber’ during economic downturns regarding employment chances. When the economy is booming, employers cannot get enough of BOL-4 graduates, but when the economy enters a downturn, the production-level jobs for which these mid-level graduates are trained are the first to be jettisoned. By contrast, the professional and management level jobs that HE graduates are trained for are less vulnerable to economic shocks. Nevertheless, over the longer term, average unemployment is slightly higher among HE graduates than among BOL-4 graduates. As such, these results suggest that HE graduates have been willing to forego earnings gains for the sake of stable employment levels, mainly in graduate-level jobs.

Our results further showed that the more adverse effects of the expansion in terms employment and earnings decreasing were particularly apparent for women and graduates with low final grades or a non-western migration background. This finding suggests that the expansion of HE has given employers more options to choose from and that employers use their increased bargaining space by selecting and rewarding additional human capital in the form of higher grades. They have also used this extra space to favour male graduates increasingly over female graduates, and graduates with a (non-western) migration background over native Dutch graduates. As such, the HE labour market is increasingly becoming a buyers’ market. In this market, graduates with attributes that buyers want – males, native Dutch graduates, high-performers – emerge as relative winners of the educational expansion.

While most of our findings apply to both university masters and HBO bachelors, there are some clear differences between the two types of HE. University masters have higher literacy skills but lower self-reported field-specific knowledge than HBO bachelors, and earn substantially more shortly after graduation. They are also more likely than HBO bachelors to work in occupations below their own designated level, although these are usually still graduate jobs in the broader sense. University masters benefit more from higher grades than HBO bachelors, whereas the gender earnings and employment gap is greater for HBO bachelors.

Overall, our results indicate that the expansion has taken some of the edges off the formerly exclusive position of HE graduates in the Dutch labour market, although it would be very premature to conclude that it has been bad for the Netherlands. Young Dutch people with an HE degree are still clearly better off than those without one, and as a whole, recent cohorts have gained more by entering HE in greater numbers than they have lost in terms of earnings.

Finally, a number of limitations of our study need to be addressed. Although our analyses paint a clear and consistent picture of the changing value of an HE degree at the moment of labour market entry, we are not in a position to draw any conclusions about the effects of the expansion on long-term graduate outcomes. This was a deliberate choice on our part, as we wanted to present results that could be directly linked to recent HE developments, and not contaminated by more general economic and societal developments. However, as such we cannot rule out that some of the patterns we observed may change later in graduates’ lives (see, e.g. Bhuller, Mogstad, & Salvanes, Citation2017; Walker & Zhu, Citation2011).

It is also important to stress that our results should not be interpreted as evidence of an added value of an HE degree compared to a BOL-4 degree. As outlined earlier, the initial decision that determines students’ final educational attainment is for a large part already taken at age 12. Since both this early tracking and possible later switches are strongly dependent upon ability and other background factors, it is effectively impossible to establish any clear counterfactual group that would allow a strict added-value analysis. Hence, our results rather indicate shifts in the current economic value of an HE degree, in which the precise mix of sorting, learning and labour market effects cannot be precisely determined.

Online_Appendix_Table_ORE.docx

Download MS Word (14.9 KB)Online_Appendix_Figures_ORE.docx

Download MS Word (111.6 KB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jim Allen

Jim Allen is a researcher at the Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market at Maastricht University’s School of Business and Economics. His fields of special interest are the connection between (higher) education and labour market outcomes, retraining and underutilisation of knowledge and skills acquired in education and in the workplace. Jim earned a PhD at the Interuniversity Centre for Social Science Theory and Methodology at the University of Groningen and holds a master’s degree in sociology (University of Groningen).

Barbara Belfi

Barbara Belfi is a researcher at the Research Centre for Education and the Labour Market at Maastricht University’s School of Business and Economics. Her research focusses on socio-economic, ethnic, and gender inequalities in education and the labour market, skill development, and group compositional effects. Barbara obtained her PhD in Educational Sciences at the KU Leuven and holds master’s degrees in cognitive psychology (Maastricht University) and Educational Sciences (KU Leuven).

Notes

1. This loss of exclusivity is not necessarily bad from a societal point of view. As long as it increases the net productive potential of the labour force as a whole, society as a whole should benefit even if individual returns decrease.

2. Origin countries in Europe (except Turkey), North America and Oceania, as well as Indonesia and Japan are classed as ‘economically western’. Origin countries in Africa, Latin America and Asia (except Indonesia and Japan), as well as Turkey, are classed as ‘economically non-western’.

3. Graduates were asked to estimate their own level, as well as the level required in their current job, on a range of knowledge and skills, including field-specific knowledge and ICT skills. Both own and required levels were rated on a 5-point scale varying from 1 (‘basic’) to 5 (‘excellent’). Changes and differences in such self-reports should be treated as indicative rather than definitive, but additional analyses (available on request) show that these self-reported skills are strongly, durably, and increasingly related to earnings, suggesting that the differences are meaningful. The skill levels shown in and are controlled for age, age-squared, gender, study province, broad field of study and migration background.

4. The results shown in through 9 are controlled for age, age squared, gender and study province.

5. Due to data restrictions only available from 2001 to 2017.

6. The labour market outcomes of graduates with a western migration background are similar to those of native Dutch graduates, and are in the interests of brevity not shown here, but available on request.

References

- Autor, D. H. (2014). Skills, education, and the rise of earnings inequality among the ‘other 99 percent. Science, 344, 843–851.

- Autor, D. H., Katz, L. F., & Kearney, M. S. (2008). Trends in US wage inequality: Revising the revisionists. The Review of Economics and Statistics, 90(2), 300–323.

- Batenburg, R., & de Witte, M. (2001). Underemployment in the Netherlands: How the Dutch ‘polder model’ failed to close the education–Jobs gap. Work, Employment and Society, 15(1), 073–094.

- Battu, H., Belfield, C. R., & Sloane, P. J. (2000). How well can we measure graduate over-education and its effects? National Institute Economic Review, 171(1), 82–93.

- Becker, G. (1957). The economics of discrimination. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Bhuller, M., Mogstad, M., & Salvanes, K. (2017). Life-cycle earnings, education premiums, and internal rates of return. Journal of Labor Economics, 35(4), 993–1030.

- Bol, T. (2015). Has education become more positional? Educational expansion and labour market outcomes, 1985–2007. Acta Sociologica, 58(2), 105–120.

- Boylan, R. D. (1993). The effect of the number of diplomas on their value. Sociology of Education, 66, 206–221.

- Brekke, I. (2007). Ethnic background and the transition from education to work among university graduates. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 33(8), 1299–1321.

- Brekke, I., & Mastekaasa, A. (2008). Highly educated immigrants in the Norwegian labour market: Permanent disadvantage? Work, Employment and Society, 22(3), 507–526.

- Brown, P., Lauder, H., & Ashton, D. (2011). The global auction: The broken promises of education, jobs and incomes. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 32(2), 293–311.

- Bütikofer, A., Jensen, S., & Salvanes, K. G. (2018). The role of parenthood on the gender gap among top earners. European Economic Review, 109, 103–123.

- Dutch Ministry of Education, Culture and Science. (2019, September 5). Studiefinanciering voor studenten op een hogeschool en universiteit [Student finance for college and university students]. Retrieved from https://www.rijksoverheid.nl/onderwerpen/studiefinanciering/studiefinanciering-hbo-universiteit

- Figueiredo, H., Biscaia, R., Rocha, V., & Teixeira, P. N. (2017). Should we start worrying? Mass higher education, skill demand and the increasingly complex landscape of young graduates’ employment. Studies in Higher Education, 42(8), 1401–1420.

- Figueiredo, H., Teixeira, P., & Rubery, J. (2013). Unequal futures? Mass higher education and graduates’ relative earnings in Portugal, 1995–2009. Applied Economics Letters, 20(10), 991–997.

- Gesthuizen, M., & Wolbers, M. H. (2010). Employment transitions in the Netherlands, 1980–2004: Are low educated men subject to structural or cyclical crowding out? Research in Social Stratification and Mobility, 28(4), 437–451.

- Goldin, C., & Katz, L. (2008). The race between technology and education. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Press.

- Goldthorpe, J. H. (2014). The role of education in intergenerational social mobility: Problems from empirical research in sociology and some theoretical pointers from economics. Rationality and Society, 26(3), 265–289.

- Green, F., & Zhu, Y. (2010). Overqualification, job dissatisfaction, and increasing dispersion in the returns to graduate education. Oxford Economic Papers, 62(4), 740–763.

- Hirsch, F. (2015). Social limits to growth. Revised 2015 Edition. Abingdon, Oxfordshire: Routledge.

- Horowitz, J. (2018). Relative education and the advantage of a college degree. American Sociological Review, 83(4), 771–801.

- Inspectorate of Education. (2013). In- en doorstroommonitor. Toegang van studenten in het hoger onderwijs: wie wel en wie niet? [Inflow and flow-through monitor. Access for students in higher education: Who does and who does not?] Utrecht: Author.

- Jacobs, J. A. (1995). Gender inequality at work. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Kalleberg, A. L. (2011). Good jobs, bad jobs: The rise of polarized and precarious employment systems in the United States, 1970s–2000s. New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Keep, E., & Mayhew, K. (2014). Inequality–‘Wicked problems’, labour market outcomes and the search for silver bullets. Oxford Review of Education, 40(6), 764–781.

- Kislev, E. (2016). Deciphering the ‘ethnic penalty’ of immigrants in Western Europe: A cross-classified multilevel analysis. Social Indicators Research, 134(2), 725–745.

- Krueger, A. B. (1993). How computers have changed the wage structure: Evidence from microdata, 1984–1989. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 108(1), 33–60.

- Laurison, D., & Friedman, S. (2016). The class pay gap in higher professional and managerial occupations. American Sociological Review, 81(4), 668–695.

- Levy, F., & Murnane, R. J. (1992). US earnings levels and earnings inequality: A review of recent trends and proposed explanations. Journal of Economic Literature, 30(3), 1333–1381.

- Liebkind, K., Larja, L., & Brylka, A. (2016). Ethnic and gender discrimination in recruitment. Experimental evidence from Finland. Journal of Social and Political Psychology, 4(1), 403–426.

- Liu, Y., & Grusky, D. B. (2013). The payoff to skill in the third industrial revolution. American Journal of Sociology, 118(5), 1330–1374.

- Marini, M. M., & Fan, P. L. (1997). The gender gap in earnings at career entry. American Sociological Review, 62(4), 589–591.

- Mayhew, K. (2016). Human capital, growth and inequality. Welsh Economic Review, 24, 23–27.

- Mok, K. H., & Neubauer, D. (2016). Higher education governance in crisis: A critical reflection on the massification of higher education, graduate employment and social mobility. Journal of Education and Work, 29(1), 1–12.

- Mooi-Reci, I., & Muñoz-Comet, J. (2016). The great recession and the immigrant–Native gap in job loss in the Spanish labour market. European Sociological Review, 32(6), 730–751.

- Mouw, T., & Kalleberg, A. L. (2010). Occupations and the structure of wage inequality in the United States, 1980s to 2000s. American Sociological Review, 75(3), 402–431.

- OECD. (2018). Decoupling of wages from productivity: What implications for public policies? OECD Economic Outlook, 2018(2),51–65

- Schomburg, H., & Teichler, U. (2006). Higher education and graduate employment in Europe. Results from graduates surveys from twelve countries. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Statistics Netherlands. (2019). Demographic statistics 2019. Voorburg/Heerlen: CBS.

- Stier, H., & Herzberg-Druker, E. (2017). Running ahead or running in place? Educational expansion and gender inequality in the labour market. Social Indicators Research, 130(3), 1187–1206.

- Thurow, L. C. (1975). Generating inequality. London: MacMillan Press.

- Tomlinson, M. (2008). ‘The degree is not enough’: Students’ perceptions of the role of higher education credentials for graduate work and employability. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 29(1), 49–61.

- Van der Ploeg, S. (1994). Educational expansion and returns on credentials. European Sociological Review, 10(1), 63–78.

- Walker, I., & Zhu, Y. (2011). Differences by degree: Evidence of the net financial rates of return to undergraduate study for England and Wales. Economics of Education Review, 30(6), 1177–1186.

- Wolbers, M. H., De Graaf, P. M., & Ultee, W. C. (2001). Trends in the occupational returns to educational credentials in the Dutch labor market: Changes in structures and in the association? Acta Sociologica, 44(1), 5–19.

- Zwysen, W., & Longhi, S. (2018). Employment and earning differences in the early career of ethnic minority British graduates: The importance of university career, parental background and area characteristics. Journal of Ethnic and Migration Studies, 44(1), 154–172.