ABSTRACT

Early years education is offered free to all three-year-olds in Northern Ireland, prior to starting primary school, and most parents take advantage of this offer for their children. An experience of early years education has been shown to considerably improve life chances and to be important in starting the process of building a shared society, particularly important in a divided society emerging from conflict such as Northern Ireland. This paper will examine the degree to which that provision is segregated using GIS analysis and explore the factors which influence those divisions within the wider context of a deeply segregated system of education. Pre-school education in Northern Ireland is found to be highly segregated by community background, and there is a tendency for pre-schools to be more segregated than the areas in which they are located. This may exacerbate existing divisions within education and adding a further year of segregated education may provide a further impediment to building a shared future for communities in Northern Ireland.

Ireland was ‘Britain’s oldest and longest-held colony’ (Clayton, Citation1998, p. 48) until the island was partitioned following armed insurrection in 1916 and a violent War of Independence. While 26 of the 32 counties of the island became an independent republic, the remainder of the island maintained its link with the United Kingdom (UK) becoming instituted as Northern Ireland in 1921. Since its inception, society in Northern Ireland (NI) has been divided. Explicitly ‘ … a Protestant Government and a Protestant People’ (Craig, Citation1934), the political structures in the fledgling state were established by Protestants, largely descendants of those who had colonised Ireland from the Plantation of Ulster from the late 1500s (Darby, Citation1995). However, a sizeable minority of Catholic nationalists remained within NI, many of whom resented remaining in the UK, bolstered by disenfranchisement and marginalisation (Kovalcheck, Citation1987). Sporadic unrest eventually erupted into ethno-political conflict in 1969, leading to a 30-year period of violence, known colloquially as ‘The Troubles’. Meanwhile, inexorable demographic changes continued to reduce the dominance of a majority who generally identified as British, Protestant and Unionist while the Irish, Catholic and Nationalist proportion continued to grow.

The conflict has largely ceased but NI society remains heavily segregated along ethno-sectarian lines, with communities so profoundly divided that many effectively live separate lives (Roulston et al., Citation2017), often with little knowledge of the ‘other’. Hewstone et al. (Citation2004) suggested that up to 40% of the population live in completely segregated residential areas, and segregation also exists in terms of work and leisure (Niens et al., Citation2003). As Hughes et al. (Citation2007) note, ‘ … segregation, which is often essentially a response to out-group fear and anxiety, in turn, ensures the long-term prevalence of such negative emotions by reinforcing mutual ignorance’ (Citation2007, p. 36).

Schools too are divided along ethno-sectarian lines, effectively meaning that most Catholics and most Protestants are educated with co-religionists; over 90% of children are taught in schools overwhelmingly with others of the same religion (Gardner, Citation2016). Attempts were made to educate all children together from the inception of universal education in Ireland in the 1830s with a nationwide network of National Schools (Akenson, Citation2012). Most of those schools eventually took on the character of the surrounding population, becoming effectively Catholic or Protestant in nature (Farren, Citation1994). On the establishment of the new NI state, Lord Londonderry, the first Education Minister, attempted to build an integrated education system, but the churches, fearful of a loss of control over ‘their’ pupils, were strongly opposed, and eventually that initiative perished (Gardner, Citation2016). Those schools owned and run by the Protestant churches eventually agreed to come under government control, becoming the Controlled Sector. While these are now ‘State’ schools, in most cases they are de facto Protestant in governance, staffing and enrolment. On the other hand, the Catholic Church, understandably reluctant to cede control to a Protestant/Unionist-dominated government, retained their schools, and a Catholic Maintained Sector was formed. In parallel, for pupils aged 11–18, there is a selective school system consisting of Grammar schools, some with a Catholic ethos and others which are effectively Protestant. Gallagher (Citation2019) notes that, ‘ … the role of the Churches remains strong in school level education, as does the level of religious separation’ (Citation2019, p. 3).

Two additional sectors have emerged in recent years. A small but slowly growing Integrated sector with the aim of educating the two communities together was established by parents with the first school opening in 1981; 7% of pupils now attend such schools. More recently an Irish Medium school sector has developed although this accounts for only around 2% of school provision and is largely, at least at present, attended by Catholics. While written over two decades ago, there remains resonance in the Hargie et al.'s (Citation2001) comment that ‘ … in many parts of the country, children of one religion never meet or talk with children of the other denomination’ (Citation2001, p. 666).

Schools remain largely divided along ethno-sectarian lines and ‘communal polarisation remains undiminished’ (Office for First Minister and Deputy First Minister [OFMDFM], Citation2005, p. 8). Borooah and Knox (Citation2017) note that just 6.7% of Catholics attend controlled primary schools and 1.1% of Protestants attend maintained primary schools (Citation2017). Of the 844 schools in 2018/19 whose annual census returns provided information for any one of the three main religion categories of pupils (Protestant, Catholic and Other), 26% recorded either no Catholic or no Protestant pupils. Another 38% had less than 10 pupils from their minority religion (calculated from DENI, Citation2019a). It has been reported that only 143 out of all the schools in NI have at least 10% of pupils from the minority background, whether Protestant or Catholic (Meredith, Citation2021).

Educational and residential segregation can help to perpetuate stereotypes and deep-seated misconceptions. Hughes (Citation2011) reports the perception of some Protestant 11- to 12-year-olds that Catholics wear veils or have squints in their eyes; some Catholic young people have similarly uninformed views of Protestants thus emphasising ‘the formative influence of the separate environment on the establishment of negative stereotypes’ (Hughes, Citation2011, p. 838). These extreme stereotypes may be becoming less prevalent; there is evidence that some of the traditional identities in NI are losing their grip on some young people in Integrated school settings, as they begin to display ‘emotional detatchment from traditional identity patterns’ (Furey et al., Citation2017, p. 145). This evidence of shifting attitudes may be partly behind the recent success of a Bill supporting Integrated Education, a movement which encourages the education of all children together. It was enacted despite considerable political opposition from some parties (Meridith, Citation2022). Nonetheless, despite evidence of some change, research shows continued division by residence (Shuttleworth et al., Citation2021) and in terms of mobility patterns (Roulston et al., Citation2017). There remains a need for education to help learners to ‘understand conflict, sectarianism and prejudices’ (Worden & Smith, Citation2017, p. 392). As Borooah and Knox (Citation2017) note, ‘many young people in Northern Ireland never experience cross-community education until they attend university’ (Citation2017, p. 320) and, unless there is considerable change designed to bring young people together, there is evidence that ‘segregation in education will sustain division in society’ (Hewstone & Hughes, Citation2015, p. 67). NI has become a more diverse society through immigration (Martynowicz & Jarman, Citation2009) and declining religiosity (McCartney & Glass, Citation2014), giving rise to social divisions relatively novel to that area. Nonetheless, the fundamental division there remains between two main communities (Jarman & Bell, Citation2018). While NI society has become more nuanced than the simple binary suggested by the labels ‘Protestant’ and ‘Catholic’, these divisions are still deeply rooted in NI.

Early years education for three- to four-year-olds in NI aims to be an exception within a divided educational system. A Department of Education (DENI) commissioned report noted that early years provision: ‘ … is not defined according to sectors (e.g. integrated, Roman Catholic maintained, Controlled), meaning all pre-school settings, regardless of location, are considered accessible to children from all backgrounds’ (RSM McClure Watters, Citation2016, p. 10).

Indeed, the early years sector has been held up as an example of mixed education (Magennis & Richardson, Citation2020; McMillan & McConnell, Citation2015), unlike education in most other sectors in NI, and that is the focus of this paper.

Early years education

There is considerable evidence that investment in high-quality educational and care experiences in early childhood can result in much improved educational outcomes. Early Childhood Education and Care (ECEC) can take many forms. One example of that provision is Sure Start, rolled out across the UK in 1999. Targeted at children under 4 years and their families in areas of need, the programme aims to provide better and more coordinated support for these families, promoting the physical, intellectual, social and emotional development of their children and ensuring that they will get the most out of starting school the following year (Glass, Citation1999). Sure Start, especially when combined with integrated Children’s Centres bringing together health, child care, education and parent-support services, has been credited with changing the life chances for young people (Melhuish, Citation2016). The initiative seems to be faltering in England following cuts to local authority funding which led to closures of Children’s Centres and limits to nursery provision for families not in employment, the very families with most to gain. However, Sure Start still seems to be thriving in NI, providing considerable benefits to young children and their families (DENI, Citation2019b).

While Sure Start is targeted at families in need, the benefits of ECEC for all young children stem from the improvement it brings to their social, emotional, cognitive and language development. The levels of skill and knowledge of the staff would appear to be crucial to the success of this intervention (see Burchinal et al., Citation2011) and, when skilled staff adapt these components to cater for the needs of individual children, the benefits when those children start primary school are maximised. As with much early years provision, teachers in pre-schools and nurseries use play in sophisticated ways to promote learning, requiring high levels of staff expertise (Walsh, Citation2007).

Pre-school provision in Northern Ireland

In NI, early years attendance is not compulsory but it is seen as offering a smooth transition into primary school and has been incorporated into the Foundation Stage of the NI Curriculum. The NI government is committed to providing a free pre-school year to every child whose family wants it, and 91% of all three-year-olds were in early years education in 2019–20 (NISRA, Citation2020). Provision is through a complex network of statutory, voluntary and private providers across NI (). It includes voluntary pre-schools and private early years part-time provision comprising playgroups in a school, nursery units within a school and separate nursery schools, all of which are centrally funded. Much of this provision involves different systems of governance and, in common with much education provision in NI, early years provision is highly fragmented (Hansson & Roulston, Citation2021), despite claims that it is not defined by sectoral divisions (RSM McClure Watters, Citation2016, p. 10). The voluntary pre-school sector includes settings run by community groups and charities and these, alongside private providers, comprise almost half of the 766 early years units. Some children attend specialist nursery schools, while others attend nursery units attached to primary schools. Reception classes are effectively the first year of primary school but can take younger children. Considered to be a less effective form of pre-school provision (DENI, Citation2013, p. 8), these are being phased out, and just 45 primary schools had a reception class in 2019–20.

Table 1. Funded early years enrolments 2018/2019. Source: DENI (Citation2019b).

Currently, the responsibility for ECEC is fragmented across a number of government departments and arm’s length bodies in NI, despite recommendations that it be brought together within one government department which could deliver ‘greater coherence and consistency in regulation, funding and staffing, enhanced continuity for children … and improved management’ (Perry, Citation2013, p. 15). All funded early years settings are inspected by the Education and Training Inspectorate, exactly as schools are inspected, but voluntary and private providers are further scrutinised by Health and Social Care Trust Inspectors. Provision therefore comprises a mixture of complex governance arrangements and that complexity carries over into the bodies who are responsible for them. However, as indicates, the complexity does not end there.

One of the main aims for ECEC in NI, as elsewhere across the world, is to improve enduring educational outcomes by facilitating improvements in children’s personal learning and wellbeing at an early age. However, in a divided society such as NI, a supplementary aim is to help children ‘acknowledge and respect diversity, promoting positive cooperation between children regardless of their gender, religious community background, nationality or ethnicity, and regardless of whether they have a disability’ (Northern Ireland Executive, Citation2015, p. 15). The NI Executive overtly advocates ‘ … accessible, affordable and universal childcare [as] a contributory step towards consolidating a united, post-conflict society’ (Northern Ireland Executive, Citation2015, p. 35). It is, however, conceded that diversity in intake and staffing is a longer-term aspiration, and that the promotion of sharing and diversity is what is required as a minimum (Northern Ireland Executive, Citation2015, p. 36). Magennis and Richardson (Citation2020) agree that ‘early years educators are a vital part of the process of fostering respect for diversity and building peaceful communities’ but acknowledge that ‘inclusion is difficult to achieve in a society that has been historically divided’ (Citation2020, p. 366).

There are other difficulties in trying to achieve inclusion. suggests that there are some divisions along ethno-sectarian lines. Catholic Maintained nursery schools and nursery units in Catholic Maintained primary schools, for instance, have a high proportion of pupils who identify as Catholic. Similarly, the category ‘Other Maintained’ is largely Irish Medium Education, which is attended mainly by Catholics at present. On the other hand, Controlled nurseries and many other sectors are apparently much more mixed, insofar as these aggregate data show.

Religious composition

While educational provision in NI is deeply segregated along ethno-sectarian lines (Gardner, Citation2016), some research maintains that ‘pre-school provision tends to be religiously and ethnically inclusive’ (McMillan & McConnell, Citation2015, p. 246). Magennis and Richardson (Citation2020) agree, arguing that ‘ … early years settings in Northern Ireland are not normally attended solely by one community or other, unlike most schools, although this is impacted by location’ (Citation2020, p. 367). In the final clause, Magennis and Richardson acknowledge that the degree to which pre-school provision is mixed depends on where the unit is located. Presumably, in places where populations are overwhelmingly from one community – and NI’s residential spaces tend to be highly segregated (Hewstone et al., Citation2004) – there is much less chance of having mixed early years provision. However, there are hints in other sources that, even in mixed areas, these schools may be segregated. In a review of pre-school education, a concern was voiced that, ‘ in small communities, viability is an issue when a group [which] is provided by the majority community of the area … will not be attended by the local minority community’ (Department of Education Northern Ireland [DENI], Citation2006, p. 91).

Where one community dominates early years provision in an area, perhaps co-locating that pre-school with a school reflecting that community, the minority community of that area may choose not to send their children there, effectively increasing segregation at pre-school level. As an explicit objective of early years provision is that it is ‘ … shared across all communities [to] enable us to build and consolidate peace’ (Northern Ireland Executive, Citation2015, p. 35), widespread segregation in early years settings makes achieving this more challenging.

Before the end of March in each academic year, all schools, including all nursery and all voluntary and private providers with funded pre-school pupils, must complete and return to the Department of Education an annual school census which records, inter alia, the religion of the pupils, allocating them to one of 13 categories such as Jewish, Jehovah Witness, Baha'i or No Religion Recorded/Religion Unknown in addition to Catholic and Protestant. When summary data are published at school level, only Protestant and Catholic numbers are provided as separate categories; all other religions, and none, are collapsed into a single category: Other Christian/non-Christian/no religion/unknown. The focus of this paper is on the Protestant and Catholic components, and to what degree those communities are educated together or apart.

Noticing differences

As one of the stated aims of pre-school provision is to help to build a united community, some sense of when young people start to notice difference would be useful. Awareness of difference in race and ability has been widely observed in pre-school children (Perlman et al., Citation2010) and, as more parents work and children are cared for away from their homes, there is a particular need for early years provision to help to develop positive attitudes to diversity. Changes in attitudes to minorities have been noted in very young children. Pioneering research from the 1940s, using dolls, showed response to racial differences by three-year-olds (Clark & Clark, Citation1947). More recent work reports that children as young as two are able to recognise racial differences and, from three years, to show ethnic prejudices based on that recognition (Keenan et al., Citation2016). Studies have found that knowledge about certain cultural stereotypes around gender and preference for peers of their own gender appears between the ages of two and three (Nesdale, Citation2001). A study of two- to three-year-old children indicated that ‘this early period of childhood is critical in the development of intergroup attitudes’ (Rutland et al., Citation2005, p. 700). Research with Jewish children in Israel found that they are able to distinguish themselves from ‘an Arab’ when two and a half to three years of age. From that age, the term ‘Arab’ starts to produce a negative connotation, even though they are too young to know much about Arabs (Bar-Tal, Citation1996). This would suggest that ‘ … the basis for the social institution of prejudice is in place early in social development’ (Perlman et al., Citation2010, p. 754).

In NI, some research suggests that, in general, prejudiced statements about the other community only start to emerge in five-year-old children and, after that, awareness increases ‘exponentially’. In one study with six-year-olds, 15% made prejudiced statements about the other community without prompting (Connolly et al., Citation2006). However, other research has suggested that Catholic and Protestant children are starting to understand the ethnic divisions around them from the age of three, with children of that age beginning to display negative attitudes to the other community (Connolly et al., Citation2009). A preference for particular cultural events and symbols which pertain to their community has been shown from the age of three, with an awareness of their significance displayed by 51% of three-year-olds (Connolly et al., Citation2002). Another study, looking at three- to 11-year-olds, concluded that cultural events and displays helped to instil an awareness of division and of ‘otherness’ (Connolly & Healy, Citation2004). Other scholars emphasise the need in NI to address

… issues of diversity and inclusion within the early years due to the fact that children begin to show awareness from a very young age … [and] … the role of early years practitioners is pivotal in supporting children and families and ultimately building a brighter future to live in a peaceful society (Magennis & Richardson, Citation2020, p. 376).

One innovative programme undertaken to help to increase awareness of diversity and difference in three–four-year-olds employed short cartoon media messages during the year. An evaluation of that work reported positive outcomes for children, and for practitioners and parents (Connolly et al., Citation2010). While the high levels of awareness of staff within pre-school settings and the positive steps taken to embrace diversity and encourage inclusion in NI have been praised, alongside the commitment of early years’ practitioners, it is emphasised that ‘due to the complex nature of this divided society … children require a wider range of opportunities to engage with those that are different’ (Magennis & Richardson, Citation2020, p. 376). These authors report some success in developing inclusive environments for early years pupils in NI. The feedback from early years professionals in that study ‘largely portrays a positive story in terms of peace-building’ (Citation2020, p. 11), although the need for more resources to support inclusion and diversity is highlighted. Additionally, Magennis and Richardson accept that problems persist in a society with segregated schooling, as ‘early years practitioner perceptions towards inclusion and sectarianism in the context of Northern Ireland are multifaceted due to the complex nature of this divided society’ (Citation2020, p. 12).

There remains a challenge for practitioners in providing opportunities for early years children to encounter diversity. Much research concludes that racial intergroup bias can be reduced through contact with other groups (McGlothlin & Killen, Citation2006; Rutland et al., Citation2005). A study with young children concluded that their reaction to racial differences reflects ‘ … the attitudes of individuals who populate their social environment’ (Castelli et al., Citation2008, p. 1512) which may be a further challenge in a society segregated by residence as well as in educational settings.

Methodology

Data on the number and religion of children enrolled in pre-schools and nursery schools (2018–19) were obtained from the Department of Education (DENI, Citation2019a) and linked to location data provided by the Northern Ireland Statistics and Research Agency (NISRA, Citationn.d.) within the Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service (NINIS, Citationn.d.). Data on religion are not available for nursery units or reception classes within primary schools, so these were excluded from the analysis. For simplicity, the term ‘pre-school’ is used to refer to the types of provision included in the analysis, namely playgroups, day nurseries and nursery schools independent of a primary school. Also excluded from the analysis was the category ‘Other’, as the focus of this study was the extent to which children from the two main communities in NI have the opportunity to mix in the pre-school setting. The 14% of pre-schools which recorded no Catholic or Protestant children on their annual census returns in 2018/19 (i.e. 100% of children are recorded as ‘Other’) are therefore not included in the analysis. This ranges from 1% of nursery schools to 31% of day nurseries, and is most prevalent among pre-schools that are privately managed.

A simple score was calculated for each pre-school to indicate the degree of segregation or mixing of children recorded as Catholic and Protestant. The score is calculated as (M-N)/(M+N), where M and N are the numbers of children identified as Catholic and Protestant. Scores range from 0 (indicating a pre-school that has an equal representation of both communities) to ±1 (attended by children of just one of the two communities). Scores between these two extremes indicate the extent of mixing or segregation; so, for example, a score of 0.8 indicates a pre-school with very uneven representation, in which one of the two communities dominates (9:1 ratio), while a pre-school with 60% of children from one community and 40% from the other would have a score of 0.2. While the score can be positive or negative (indicating which community has larger numbers), for most forms of analysis the ‘absolute’ value is used with all values treated as positive, indicating the degree of segregation without specifying the dominant community.

In the enrolment statistics published annually by the Department of Education NI, religion data is withheld where counts are so low as to be considered sensitive – less than 5 individuals – and under rules of disclosure. As a consequence, a high proportion of data is incomplete (affecting 45% of pre-schools for the year analysed). The data suppression is most likely to affect schools that are strongly segregated, rather than those that are entirely segregated or more evenly mixed, potentially producing a biased dataset. Rather than excluding these pre-schools from analysis, values were estimated to replace withheld ones, substituting a value of three for counts between one and four, and estimating other suppressed values according to total enrolment numbers. At school-level, this inevitably means a degree of error; where data have been suppressed, estimated segregation for the average-sized pre-school (mean enrolment of 30, excluding those with 100% ‘Other’) would be 0.80, yet the true figure may lie between 0.93 and 0.73. However, since the analysis focuses primarily on average segregation values, the impact of the error will be minor. To explore this further, a pre-school dataset from 2014 to 2015 which has no values withheld was used to model the impact of replacing values in the range 1–4 with 3 and modifying other values accordingly. Comparison of segregation scores for the original and modelled datasets for 2014–15 showed the method resulted in a minor reduction in average segregation score (from 0.74 to 0.70), while statistical tests comparing the distributions (Mann-Whitney and Kolmogorov-Smirnov) confirmed there was no significant difference in the original and the modelled distributions (p > 0.05). This validates the method used, which enabled a geographically complete dataset.

Using 2011 Census data on religion (from NINIS) for NI’s 4,537 ‘Small Areas’ (mean population 399), the degree of mixing or separation of Catholic and Protestant residents was calculated using the same formula. Digital maps of settlements and census Small Areas (from NISRA’s website) and Ordnance Survey NI maps of local government districts were used as the spatial frameworks for analysis. Esri’s ArcGIS Pro was used to combine spatial datasets (table joins and spatial joins) and quantitative analysis was undertaken using Excel, SPSS and ArcGIS Pro.

Results and discussion

Segregation in pre-schools and primaries

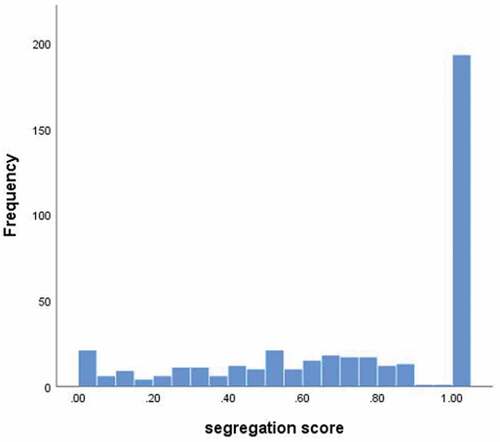

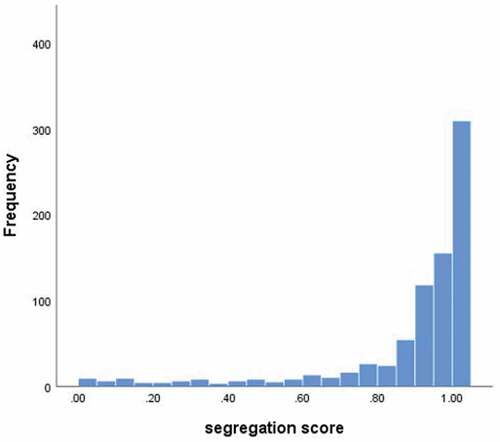

Despite research suggesting that pre-school provision was generally mixed, this study indicates a high degree of segregation, shown by the frequency graph () and average scores (). Excluding the pre-schools recorded as 100% ‘Other’, only 16% have scores indicating relatively low segregation of Protestants and Catholics (up to 0.33, meaning that the number of children in a pre-school from the larger community is no more than twice that of the smaller one); in a further 15%, the larger community is between two and four times the size of the smaller (scores from 0.34 to 0.6), and the remainder are more strongly segregated, with 47% attended only by children of one of the two communities (score of 1.0, shown as the strong peak to the right of ). For comparison, and show the equivalent scores for primary schools in NI, a sector known to be highly segregated (Roulston & Cook, Citation2021). While a smaller proportion of primary schools has scores indicating low to moderate segregation (with only 10% having scores of 0.6 or below), they also have a smaller proportion that is completely segregated (39%). These results appear to contradict the perception of some that pre-school provision tends not to be segregated (Magennis & Richardson, Citation2020; McMillan & McConnell, Citation2015).

Table 2. Average segregation scores for pre-schools (and sub-sets), primary schools and census small areas.

It had been surmised that early years provision located within the grounds of an existing Maintained or Controlled primary would be likely to have higher levels of segregation, as they may be perceived as having the same ethos as the primary school. Many are exactly co-located (89 of 481) and another 13 are within 15 metres of the centre point of a primary school. GIS distance analysis found that pre-schools exactly co-located with a primary school have slightly higher mean and median segregation scores compared with those located at least 150 metres from a primary (), and that a greater proportion are entirely segregated (65% of those that are co-located compared to 42% of those more than 150 metres away). Comparing pre-schools categorised as ‘playgroups within a school’ and ‘playgroups not in a school’ produces very similar findings. Average scores for primary schools were the same regardless of whether they were co-located with a pre-school, so the difference in pre-school scores is not likely to be due to other geographical factors. These findings suggest that early years provision within a school does tend to be a little more segregated than that which is not co-located.

Residential segregation and pre-schools

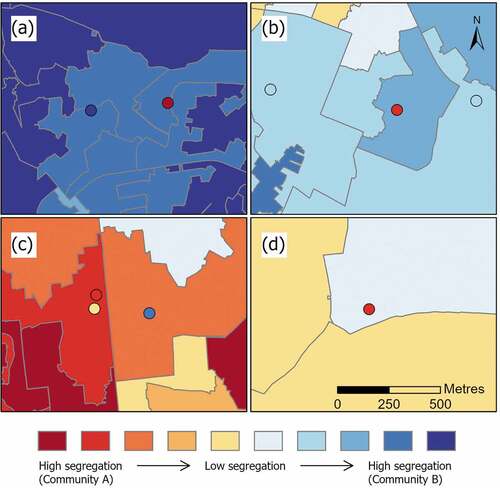

To a large extent, the degree of separation of children in early years settings reflects the fact that many people in NI live in areas that are relatively homogeneous in terms of religious and community affiliation (see for average segregation in census Small Areas), and 42% of the population lives in areas where the ratio of the two main communities is at least 9:1 (based on 2011 Census data). Mapping shows that, in many cases, pre-schools with high segregation scores lie within areas in which most of the population identifies as belonging to the same community. However, it also highlights many apparent anomalies, a few examples of which are illustrated in (which avoids explicit mention of locations and names of specific pre-schools due to possible sensitivity). This uses segregation scores in the form that differentiates the two communities. shows (a) a large cluster of areas with high population segregation (≥0.7) containing two pre-schools a few hundred metres apart, one of which is attended by Protestant pre-schoolers and no Catholics, the other with Catholics and no Protestants; (b) an area of relatively low population segregation (scores around 0.2–0.4) with two pre-schools reflecting this mix and a third with the majority of enrolments from the minority community; (c) three pre-schools within 300 metres of each other, one of which is mainly Protestant, another mainly Catholic, the third evenly mixed; and (d) a Cross-Community playgroup with over 80% of the children from one community, located in a relatively mixed area.

It is possible that some of these individual anomalies may be explained by patterns of religious segregation that are too micro-scale to be identified using census data, by circumstances unrelated to the local population (e.g. children from elsewhere being enrolled due to parental employment nearby), by the methodology used to substitute values for withheld data, or by random variations in that year’s enrolments. However, further analysis combining pre-school and census data suggests they are indicative of a general tendency rather than exceptions.

Geographical variation

Populations across NI vary from evenly mixed in terms of religious background to strongly divided (segregation scores for Small Areas range between 0 and 1). Quantitative analysis of geographical variation therefore focused not only on pre-school segregation, but also on how it compares to segregation in the surrounding population.

Across NI, nearly two- thirds of pre-schools are more segregated than the Small Areas within which they are located, and even in locations that are relatively mixed (score ≤ 0.2, ratio up to 1.5:1), more than 40% of pre-schools are highly segregated (≥ 0.6, 4:1 or higher). Spatial analysis by local government district and by settlement category indicated, not surprisingly, that the places which have the highest average segregation (including the cities of Belfast and Derry) contain the most segregated pre-schools, and that less urbanised districts and smaller settlements tend to have lower segregation. It also showed that the tendency for pre-schools to have higher average segregation than the nearby population is consistent across almost all districts and settlement types. Notable exceptions are found among smaller settlements (population 1,000–4,999), although, in contrast, Small Areas located in open countryside and smaller villages have relatively low average residential segregation but the highest pre-school segregation outside the cities. Scores by settlement size are shown in .

Table 3. Segregation by settlement category: average scores and percentage of pre-schools with higher or unrepresentative segregation (more segregated than the Small Area population, or majority of pupils from the ‘minority’ community for that location).

The segregation score of each pre-school was also compared to that of the Small Area in which it was located to evaluate whether its religious composition was representative of the nearby population. shows, for each settlement category, the percentage of pre-schools that are either more segregated, or else have a higher proportion of children from the community that is in the minority locally – in either case, suggesting those pre-schools tend to attract enrolments that are not representative of the local population. This again particularly highlights pre-schools in larger settlements, as well as those in the countryside.

What’s in a name/management type?

There are differences in average segregation depending on the management type, with Catholic Maintained pre-school provision being the most highly segregated at > 0.9, followed by Voluntary, then Controlled, with Private the lowest at < 0.6. Many of the most segregated pre-schools that are Catholic Maintained (and some Voluntary) have names that signal a religious affiliation, although more research would be required to ascertain whether that indicator of community affiliation was a component in parents’ choice of a pre-school.

Including the term ‘Community’ in the name of a pre-school is not uncommon for some voluntary and private providers, with 17% doing so, although it is notable that no pre-schools in Belfast have chosen to do this. It is not clear whether that term is intended to signify the community local to the provider or the NI community as a whole. While there is no consistency in the use of ‘Community’ as part of a pre-school’s name in relation to whether it is more or less segregated than the population, the term ‘Community’ is less commonly used in highly segregated pre-schools.

A smaller proportion (just over 4%) of pre-school providers explicitly declare their ambition to be Cross Community by incorporating that in their name. Of the 17 Voluntary and Private pre-school providers which employed ‘Cross Community’ in their title in 2018–19, five show evidence of having achieved that to some degree; two of those have very mixed enrolments. On the other hand, two providers listed 100% of their enrolment as ‘Other Christian/non-Christian/no religion/unknown’, and another two have 100% enrolment from just one community. The term ‘Cross Community’ is more common in pre-schools with segregation levels which are similar to, or lower than, that of the surrounding population, although it also appears in the name of a small number of highly segregated pre-schools.

Conclusion

A significant proportion of pre-school enrolments could not be included in this analysis, as religion data is not available for nursery units in primary schools. However, based on the findings relating to pre-schools co-located with a primary school, and in view of the strong segregation within the primary sector, there is little reason to expect these would be more mixed than the data analysed. Excluding them from the analysis will not have exaggerated the degree of pre-school segregation. Similarly, estimating suppressed values does not artificially increase segregation scores.

The GIS analysis shows a general tendency for pre-schools to be more segregated than the surrounding population; while pre-school catchments will not coincide well with the census area within which it is located, the findings are too consistent to be due to chance alone. Some spatial variation does exist and the difference in segregation between pre-school enrolments and the local population is lower in some of the smaller settlements, though the greater disparity in the open countryside category (consisting of dispersed housing, farming communities and small villages) runs counter to this. On the other hand, there are encouraging examples of pre-schools with mixed enrolments located within areas that are relatively segregated, and around one fifth are less segregated than the surrounding population. Further analysis of patterns of segregation in relation to socio-economic and demographic factors, as well as research on parental choice of pre-school, would help explain the patterns and anomalies observed.

The finding in this study that some units are consistently reporting 100% ‘Other’ in the annual census would suggest that the requirements of the Department’s Statistical Returns are being interpreted rather broadly, especially considering that some of the same providers recorded high levels of enrolment from one of the main communities in NI in previous returns. While aggregation of data may be required to protect anonymity in some instances, having incomplete or misleading data may limit policy-making and interventions that otherwise could be made.

The governance of pre-school provision reflects the unnecessary complexity of NI’s divided education system, but structural issues with regard to governance and staffing can be addressed. It may be more difficult to tackle segregation in pre-school provision. The widespread segregation of schools in NI is well attested. This has been known as affecting children and young people from four years of age (NI has the lowest age of entry to primary education in Europe) to 16/18 years. Challenging such community divisions is difficult, even where there is a political will to do so (Hansson & Roulston, Citation2021). The wider point is that, while it is clear pre-school provision can offer considerable advantages in terms of long-term educational outcomes, if modelled on an already flawed system, this may exacerbate existing divisions within education. In the case of NI, in most instances it seems to have the effect of merely adding another year of segregation of communities, and at a very formative time for children. Pre-school provision in NI was seen as an opportunity to address division, in a new and thus unsegregated sector. Instead, whether through the new sector reflecting what was already there or through a lack of will to make it different, it seems merely to replicate and add to existing social divisions.

There is an explicit recognition that early years enrolments may reflect the community in which they are found but, over time, it was hoped that this provision would have an increasing role in embracing diversity and building peaceful communities. The degree of segregation in early years highlighted in this research would suggest that such a process has not happened thus far, and there seems little likelihood of that changing in the future. Providing opportunities for an additional year’s education, even if not statutory, will mean, for most pupils, educational segregation by religious affiliation starting from three years of age, and potentially continuing for 15 years. While there is evidence that noticing the differences between communities is not fully developed in three-year-olds, research suggests that it is important to develop inclusion at that age and to ensure that diversity is something to be welcomed and not feared by pre-school aged children. With a largely segregated pre-school sector, it will be challenging for staff in those units to achieve that.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Stephen Roulston

Stephen Roulston is a Research Fellow in the UNESCO Centre in the School of Education at Ulster University, formerly Course Director for PGCE Geography. After 20 years teaching, largely Geography and Geology, in a range of schools in Northern Ireland, he was an Educational Consultant in eLearning, joining Ulster University as a Lecturer in 2009. His research interests include ICTs used in supporting learning and teaching as well as the challenges of education in a divided society emerging from conflict.

Sally Cook

Sally Cook has been a Lecturer and Reader in GIS in the School of Geography and Environmental Sciences at Ulster University for more than 20 years, following four years as a postdoctoral researcher in the same school. Her teaching and research interests focus on the science, technology, and application of GIS and geographic methodologies, with emphasis on the use of GIS for spatial and statistical analysis of social, environmental, and health impacts.

References

- Akenson, D. (2012). The Irish education experiment: The national system of education in the nineteenth century. Routledge.

- Bar-Tal, D. (1996). Development of social categories and stereotypes in early childhood: The case of “the Arab” concept formation, stereotype and attitudes by Jewish children in Israel. International Journal of Intercultural Relations, 20(3–4), 341–370. https://doi.org/10.1016/0147-1767(96)00023-5

- Borooah, V. K., & Knox, C. (2017). Inequality, segregation and poor performance: The education system in Northern Ireland. Educational Review, 69(3), 318–336. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2016.1213225

- Burchinal, M., Kainz, K., & Cai, Y. (2011). How well do our measures of quality predict child outcomes? A meta-analysis and coordinated analysis of data from large-scale studies of early childhood settings. In M. Zaslow (Ed.), Reasons to take stock and strengthen our measures of quality (pp. 11–31). Brookes Publishing.

- Castelli, L., De Dea, C., & Nesdale, D. (2008). Learning social attitudes: Children’s sensitivity to the nonverbal behaviors of adult models during interracial interactions. Personality & Social Psychology Bulletin, 34(11), 1504–1513. https://doi.org/10.1177/0146167208322769

- Clark, K. B., & Clark, M. P. (1947). Racial identification and preference in Negro children. In T. M. Newcomb & E. L. Hartley (Eds.), Readings in social psychology. Henry Holt.

- Clayton, P. (1998). Religion, ethnicity and colonialism as explanations of the Northern Ireland conflict. In D. Miller (Ed.), Rethinking Northern Ireland: Culture, ideology and colonialism (pp. 40–54). Longman.

- Connolly, P., Fitzpatrick, S., Gallagher, T., & Harris, P. (2006). Addressing diversity and inclusion in the early years in conflict‐affected societies: A case study of the media initiative for children—Northern Ireland. International Journal of Early Years Education, 14(3), 263–278. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760600880027

- Connolly, P., & Healy, J. (2004). Children and the conflict in Northern Ireland: The experiences and perspectives of 3–11 year olds. OFMDFM.

- Connolly, P., Kelly, B., & Smith, A. (2009). Ethnic habitus and young children: A case study of Northern Ireland. European Early Childhood Education Research Journal, 17(2), 217–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13502930902951460

- Connolly, P., Miller, S., & Eakin, A. (2010). A cluster randomised trial evaluation of the media initiative for children: respecting difference programme. Centre for Effective Education, Queen’s University Belfast.

- Connolly, P., Smith, A., & Kelly, B. (2002). Too young to notice? The cultural and political awareness of 3-6 year olds in Northern Ireland. Community Relations Council. http://www.paulconnolly.net/publications/too_young_to_notice.pdf

- Craig, J. (1934). The Stormont Papers 35:73. https://stormontpapers.ahds.ac.uk/

- Darby, J. (1995). Conflict in Northern Ireland: A background essay. In S. Dunn (Ed.), Facets of the conflict in Northern Ireland (pp. 15–26). Macmillan.

- DENI. (2013). Learning to learn: A framework for early years education and learning. https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/de/a-framework-for-ey-education-and-learning-2013.pdf

- DENI. (2019a). School enrolment data for 2018/19. https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/articles/school-enrolments-school-level-data

- DENI. (2019b). Second sure start evaluation report. https://www.etini.gov.uk/publications/second-sure-start-evaluation-report

- Department of Education Northern Ireland. (2006). Outcomes from the review of pre-school education in Northern Ireland. https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/de/final-outcomes-of-the-review-of-pre-school-education-in-northern-ireland.pdf

- Farren, S. (1994). A divided and divisive legacy: Education in Ireland 1900‐20. History of Education, 23(2), 207–224. https://doi.org/10.1080/0046760940230205

- Furey, A., Donnelly, C., Hughes, J., & Blaylock, D. (2017). Interpretations of national identity in post-conflict Northern Ireland: A comparison of different school settings. Research Papers in Education, 32(2), 137–150. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2016.1158855

- Gallagher, T. (2019). Education, equality and the economy. Queen’s University Belfast, https://www.qub.ac.uk/home/Filestore/Filetoupload,925382,en.pdf.

- Gardner, J. (2016). Education in Northern Ireland since the good friday agreement: Kabuki theatre meets danse macabre. Oxford Review of Education, 42(3), 346–361. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2016.1184869

- Glass, N. (1999). Sure start: The Development of an early intervention programme for young children in the United Kingdom. Children & Society, 13(4), 257–264. https://doi.org/10.1002/CHI569

- Hansson, U., & Roulston, S. (2021). Integrated and shared education: Sinn Féin, the democratic unionist party and educational change in Northern Ireland. Policy Futures in Education, 19(6), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1177/1478210320965060

- Hargie, O. D., Tourish, D., & Curtis, L. (2001). Gender, religion, and adolescent patterns of self-disclosure in the divided society of Northern Ireland. Adolescence, 36(144), 665–679.

- Hewstone, M., Cairns, E., Voci, A., Paolini, S., Mclernon, A., Crisp, R., Niens, U., & Craig, J. (2004) Intergroup contact in a divided society: Challenging segregation in Northern Ireland, In D. Abrams, J. M. Marques & M. A. Hogg (Eds.), The social psychology of inclusion and exclusion (pp. 265–92). Psychology Press.

- Hewstone, M., & Hughes, J. (2015). Reconciliation in Northern Ireland: The value of inter-group contact. British Journal of Psychology International, 12(3), 65–67. https://doi.org/10.1192/S2056474000000453

- Hughes, J. (2011). Are separate schools divisive? A case study from Northern Ireland. British Educational Research Journal, 37(5), 829–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/01411926.2010.506943

- Hughes, J., Campbell, A., Hewstone, M., & Cairns, E. (2007). Segregation in Northern Ireland. Policy Studies, 28(1), 33–53. https://doi.org/10.1080/01442870601121429

- Jarman, N., & Bell, J. (2018). Routine divisions: Segregation and daily life in Northern Ireland. Manchester University Press.

- Keenan, C., Connolly, P., & Stevenson, C. (2016). Universal preschool-and school-based education programmes for reducing ethnic prejudice and promoting respect for diversity among children aged 3-11: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Campbell Collaboration.

- Kovalcheck, K. A. (1987). Catholic Grievances in Northern Ireland. Appraisal and Judgment the British Journal of Sociology, 38(1), 77–87. https://doi.org/10.2307/590580

- Magennis, J., & Richardson, N. (2020). A ‘peace’ of the jigsaw: The perspectives of early years professionals in inclusion and diversity within the context of Northern Ireland. Education 3-13, 48(4), 365–378. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2019.1610023

- Martynowicz, A., & Jarman, N. (2009). New Migration, Equality and Integration. Issues and Challenges for Northern Ireland, Equality Commission for.

- McCartney, M., & Glass, D. (2014). The decline of religious belief in post-World War II Northern Ireland. University of Ulster. https://docplayer.net/22475448-The-decline-of-religious-belief-in-post-world-war-ii-northern-ireland.html

- McGlothlin, H., & Killen, M. (2006). Intergroup attitudes of European American children attending ethnically homogeneous schools. Child Development, 77(5), 1375–1386. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8624.2006.00941.x

- McMillan, D. J., & McConnell, B. (2015). Strategies, systems and services: A Northern Ireland early years policy perspective. International Journal of Early Years Education, 23(3), 245–257. https://doi.org/10.1080/09669760.2015.1074555

- Melhuish, E. (2016). Longitudinal research and early years policy development in the UK. International Journal of Child Care and Education Policy, 10(3), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40723-016-0019-1

- Meredith, R. (2021). NI education: No religious mix in ‘nearly a third of schools’. BBC News. Retrieved November 11, 2021, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-59242226

- Meridith, R. (2022) Integrated education: Stormont passes bill despite DUP opposition. BBC News. Retrieved March 9, 2022, from https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-northern-ireland-60682540

- Nesdale, D. (2001). Development of prejudice in children. In M. Augoustinos & K. J. Reynolds (Eds.), Understanding prejudice, racism and social conflict (pp. 57–72). Sage.

- Niens, U., Cairns, E., & Hewstone, M. (2003). Contact and conflict in Northern Ireland. Palgrave.

- NISRA. (2020). Annual enrolments at schools and in funded pre-school education in Northern Ireland 2019-2020. https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/education/revised%203rd%20March%202020%20-%20Annual%20enrolments%20at%20schools%20and%20in%20pre-school%20.pdf

- NISRA. (n.d.) https://www.nisra.gov.uk/support/geography/urban-rural-classification

- Northern Ireland Executive. (2015). Delivering social care through childcare. A ten year strategy for affordable and integrated childcare 2015-2025. https://www.executiveoffice-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/consultations/ofmdfm/draft-childcare-strategy.pdf

- Northern Ireland Neighbourhood Information Service. (n.d.). https://www.ninis2.nisra.gov.uk

- Office for First Minister and Deputy First Minister. (2005). A shared future: Policy and strategic framework for good relations in Northern Ireland. Community Relations Unit.

- Perlman, M., Kankesan, T., & Zhang, J. (2010). Promoting diversity in early child care education. Early Child Development and Care, 180(6), 753–766. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430802287606

- Perry, C. (2013). Early years provision. NIAR 68-13. http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/publications/2013/education/6313.pdf

- Roulston, S., & Cook, S. (2021). Isolated together: Proximal pairs of primary schools duplicating provision in Northern Ireland. British Journal of Educational Studies, 69(2), 155–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2020.1799933

- Roulston, S., Hansson, U., Cook, S., & McKenzie, P. (2017). If you are not one of them you feel out of place: Understanding divisions in a Northern Irish town. Children’s Geographies, 5(4), 452–465. https://doi.org/10.1080/14733285.2016.1271943

- RSM McClure Watters. (2016). Research on the educational outcomes of pre-school Irish medium education finalreport – March 2016. https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/articles/irish-medium-pre-school-research

- Rutland, A., Cameron, L., Bennett, L., & Ferrell, J. (2005). Interracial contact and racial constancy: A multi-site study of racial intergroup bias in 3–5 year old Anglo-British children. Applied Developmental Psychology, 26(6), 699–713. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2005.08.005

- Shuttleworth, I., Foley, B., Gould, M., & Champion, T. (2021). Residential mobility in divided societies: How individual religion and geographical context influenced housing moves in Northern Ireland 2001–2011. Population, Space and Place, 27(2), e2387. https://doi.org/10.1002/psp.2387

- Walsh, G. (2007). Early Childhood education and care in Northern Ireland. In M. M. Clarke & T. Waller (Eds.), Early childhood education and care: Policy and Practice (pp. 51–82). Sage.

- Worden, E. A., & Smith, A. (2017). Teaching for democracy in the absence of transitional justice: The case of Northern Ireland. Comparative Education, 53(3), 379–395. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050068.2017.1334426