ABSTRACT

This study investigated the impact of the Dutch family-oriented Collaborative Learning intervention, characterised by a partnership approach and provision of personalised support. We assessed effects on parents’ home-based school involvement, perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship, and parenting skills. Fifty-six families with children in grades 1–4 (aged 4–9) were randomly assigned to an intervention or waiting list condition. Results of two path models, using cluster-robust standard errors to adjust for nesting within our data, and controlling for baseline values of our outcome variables, indicated small improvements in home-based school involvement among families in the intervention group, but no differences in the perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship nor in parenting skills. Our findings provide preliminary evidence for the idea that, under conditions of a partnership approach and provision of personalised support, efforts to support and strengthen the capacities of lower SES parents to promote child development can be fruitful.

Children from different socio-economic and ethnic backgrounds enter school with varying levels of language, reading, and reasoning skills (Azzolini, Schnell, and Palmer Citation2012; Bradley and Corwyn Citation2002; Noble, Norman, and Farah Citation2005) and these differences increase over time (Potter and Roksa Citation2013; Reardon Citation2011). Recent reports show that Dutch children are no exception to this phenomenon of “diverging destinies” (CPB (Dutch Central Planning Agency) Citation2019). Parents with lower socio-economic status (SES) differ from their higher SES counterparts in their approach to parenting and in their approach to supporting their children’s (school) development. Scholars have shown that the behaviour and involvement of lower SES parents is less in line with schools’ expectations of the parental role than those of their higher SES counterparts (e.g. Lareau Citation2002), in terms of their home-based school involvement, their parenting skills, and also with respect to the relationship they have with the teacher of their child. For example, lower SES parents are less likely to create a stimulating home environment using games and educational material, and they are less likely to intervene and advocate to the teacher on their child’s behalf. As studies have shown that home-based school involvement, high quality parenting skills and a high-quality parent-teacher relationship are important in participating in school successfully (Bradley et al. Citation2001b; Cheadle and Amato Citation2011; Henderson and Mapp Citation2002; Lee and Bowen Citation2006; Leventhal et al. Citation2004; Page et al. Citation2009; Park and Holloway Citation2017; Roksa and Potter Citation2011), these patterns contribute to the finding that children from lower SES families are often not optimally prepared for a successful school career, which increases risks of school failure, dropout, and markedly fewer professional career opportunities in adulthood for these children (Forster and van de Werfhorst Citation2020).

In the past decades, numerous educators, policy makers, politicians, and scholars have developed, implemented, and assessed family-oriented interventions to support and strengthen the capacities of lower SES parents to promote child development and thereby reduce the gap in children’s school performances. Although there is consensus that parents play a vital role in promoting children’s school success, there is mixed evidence for the effectiveness of parental involvement interventions (see for overviews Fishel and Ramirez Citation2005; Jeynes, Citation2012; Mattingly et al. Citation2002; See and Gorard Citation2013). Several scholars did not find support for the effectiveness of this type of intervention and suggest this is caused by the fact that programmes have not been developed with, and tailored to, the needs and obstacles of families (e.g. Abdul-Adil and Farmer Citation2006; Applyrs Citation2018; Bower and Griffin Citation2011). The traditional paradigm for parent involvement interventions focuses on knowledge and skill deficiencies of parents and is perceived as insensitive to family members’ time, financial, or educational limitations (e.g. Halgunseth et al. Citation2009). These concerns resonate with the finding that many interventions do not meet two important criteria for effectiveness, namely (1) treating parents as partners in the intervention, and (2) tailoring interventions to the needs of both the parent and the child (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2016).

In the current study, we investigated the effectiveness of the intervention programme “Collaborative Learning” [Samen Leren in Dutch], explicitly designed to meet the above-mentioned criteria (Huyts and Groeneweg Citation2016). Collaborative Learning aims to improve parents’ home-based school involvement, their parenting skills, and the quality of the parent-teacher relationship, in order to ultimately improve children’s school performances and, therefore, more generally, their development opportunities. The intervention targets lower SES families living in deprived neighbourhoods. The intervention provides personalised support to families by means of home visits, during which professionals engage parents in guided practice.

Although there are more home-based intervention programmes implemented in the Netherlands (such as “Opstap Opnieuw”; van Tuijl, Leseman, and Rispens Citation2001 or “De VoorleesExpress”; (De Vries, Moeken, and Kuiken Citation2015)) aiming at improving parenting skills and parental involvement to enhance children’s school performances, these are not characterised by a partnership approach or the provision of personalised support. In general, meta-analyses reveal that that there are currently few programmes that allow for differentiation in programme activities (e.g. within family literacy programs: Fikrat-Wevers, van Steensel, and Arends Citation2021).

Differences in home-based school involvement, the relationship with teachers, parenting skills, and school performances, by parents’ SES

There is consensus among scholars that differences in parenting behaviour fuel the trend of children’s diverging destinies (Conger, Conger, and Martin Citation2010; Ermisch, Jantti, and Smeeding Citation2012; Kalil Citation2014; McLanahan Citation2004; Putnam Citation2015). Using data collected from extensive fieldwork among 88 White and Black children from different social strata, Lareau (Citation2002) argued that families with higher SES engage in concerted cultivation: deliberate efforts to facilitate their children’s development by creating a stimulating home environment using games and educational material (i.e. books). Lower SES families, on the other hand, were shown to rely to a greater extent on natural growth: they perceive children’s development as more spontaneous, and thus create a less orchestrated environment. In line with this, recent studies have shown that home-based parental involvement differs between lower and higher SES parents in several respects: higher SES parents spend more time playfully teaching their children skills and knowledge (e.g. Altintas Citation2016; Keizer et al. Citation2020), they more often help their children with their homework (e.g. Von Otter Citation2014), and they have more books and educational material in their homes (e.g. Bradley et al. Citation2001a; Desforges and Abouchaar Citation2003). Other scholars have shown that the home-based school involvement of higher SES parents is more beneficial for children’s academic outcomes than that of lower SES parents (e.g. Cheadle and Amato Citation2011; Henderson and Mapp Citation2002; Lee and Bowen Citation2006; Roksa and Potter Citation2011).

Besides differences in home-based school involvement, higher and lower SES parents also differ in the relationship they have with the teacher of their child, which is an important element of school-based involvement (Epstein et al. Citation2009). Lareau’s (Citation1996) work showed that higher SES parents take a very active stance towards their child’s school and their child’s teacher; They engage in active parenting that includes intervening and advocating to the teacher on their child’s behalf. Lower SES parents take a much less active stance towards school and perceive the teacher of their child to be most knowledgeable and responsible for their child’s educational progress. Furthermore, parents with lower SES are less likely to sufficiently master the type of language schools typically use to communicate with parents. In line with the above, recent studies have shown that lower SES parents are less likely to initiate (email) contact with the child’s teacher (Thompson Citation2008) and that the relationship with the teacher is of lower quality; characterised by lower levels of trust and agreement, more unclear communication, less agreement about issues affecting the child and lower levels of satisfaction with the interactions (Nzinga-Johnson, Baker, and Aupperlee Citation2009). Although not specifically focused on the relationship with the teacher, scholars have shown that school-based involvement of higher SES parents is more beneficial for children’s academic outcomes than that of lower SES parents (e.g. Park and Holloway Citation2017).

Finally, differences between lower and higher SES parents also exist in terms of parenting skills. Parents with lower SES are more likely to live in deprived neighbourhoods – neighbourhoods that are characterised by low-income households, a poor living environment, and a high crime rate –, and they are more likely to experience financial and social problems. The stress incurred from living under such conditions (Masarik and Conger Citation2017) has been demonstrated to, in turn, affect their parenting skills: the parental skills of lower SES parents are characterised by less warmth, nurturance, and positive stimulation in comparison to those of higher SES parents, and lower SES parents are less likely than higher SES parents to provide arguments when they direct their children’s actions or take decisions (e.g. Mistry et al. Citation2008). Numerous studies have shown that warmth, nurturance, positive stimulation, and reasoning positively influences children’s school performances (Bradley et al. Citation2001b; Leventhal et al. Citation2004; Page et al. Citation2009).

The abovementioned review shows that, on average, higher and lower SES parents differ in terms of their home-based school involvement, the relationship they have with their child’s teacher, and their parenting skills. Family-oriented interventions that focus on strengthening these behaviours and relationships may enhance the capacity of lower SES parents to promote child development and therefore ultimately reduce the gap in children’s school performances between families with higher and lower SES.

Important aspects for effective interventions

As mentioned above, there is consensus in the literature that family interventions should fulfill two important criteria in order to be effective (e.g. National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2016), in particular among families who could benefit from these interventions the most. The first criterion is to treat parents as partners. A critique of many parental involvement interventions is that they are based on school cultures that are formed from middle-class European-American cultural norms (e.g. Freeman Citation2010). These interventions focus primarily on the deficiencies of families and insist parents adapt to the preferences of the school (Tett Citation2001). As such, parental practices that deviate from these preferences but do support children’s education may be overlooked and underappreciated (Halgunseth et al. Citation2009). To be effective, interventions should start from a strengths-based perspective that is built on families’ home cultures and experiences as well as parents’ strong motivation to help their children (Carpentieri Citation2012). As such, strong family-programme partnerships are often those that “are co-constructed and characterized by trust, shared values, ongoing bidirectional communication, mutual respect, and attention to each party’s needs” (Halgunseth et al. Citation2009, 6). Indeed, research shows that treating parents as partners in the intervention enhances the quality of interactions between parents and professionals and increases parents’ trust in professionals (Jago et al. Citation2013). In addition, consistency with families’ values, routines, and resources increases acceptance and implementation of the intervention (Manz et al. Citation2010). Strong and successful parental involvement interventions, such as “Nurse Family Partnership” generally try to forge such collaborations (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2016).

The second criterion is the tailoring of interventions to the needs of both the parent and child. Because the needs of individual parents and children vary greatly and often depend on family context, effective interventions, such as “Early Head Start Home Visiting” or “Parents as Teachers” generally tailor their services to fit individual needs (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine Citation2016). Firstly, children may differ in the school domain in which they need most help and support. Secondly, parents may differ in the knowledge and expertise they have to help and support their child with school. With respect to lower SES parents in specific, an important factor to take into consideration is parents’ diversity in terms of knowledge of the school system (Forster and van de Werfhorst Citation2020) and in terms of language and literacy skills. Parents may thus differ in the type of support and guided practice they themselves need to be able to help and support their child with school. Thirdly, practical circumstances also shape the set-up of the intervention. For example, it may be important to take account of the diversity in employment circumstances, as parents for example may work very long hours in double shifts. Tailoring an intervention to the context of each family decreases the likelihood of families feeling over-questioned (Borra, Van Dijk, and Verboom Citation2016), which increases the likelihood of dropping out of the intervention. Moreover, and importantly, tailoring an intervention to the needs of the participants is associated with higher effectiveness (Noar, Benac, and Harris Citation2007). Co-constructing with the aim of creating an individualised intervention would therefore yield most benefits for each family.

Collaborative learning intervention

The Collaborative Learning intervention was developed by Frontlijn, an organisation constituted by the municipality of Rotterdam, the Netherlands. Frontlijn’s main mission is to develop interventions in the field to overcome issues/challenges present in deprived neighbourhoods. Within the framework of “District-oriented working”, the municipality requested Frontlijn to develop an intervention to increase the development opportunities of children, which resulted in the Collaborative Learning intervention.Collaborative Learning, which is offered free of charge, has been developed and implemented in the field since 2011 in deprived neighbourhoods in Rotterdam South. Deprivation is based on two broad indicators: a weak socio-economic structure and a weak physical living environment and infrastructure (Deetman and Mans Citation2011). In terms of the former, residents in these neighbourhoods have lower levels of household income, lower levels of educational attainment, and a higher chance of being unemployed. In addition, children of these residents have lower standardised school performances (CITO) scores compared to the Rotterdam average. In terms of the latter, these neighbourhoods often deal with housing problems; most residents live in small and old houses, with few opportunities to renovate. In addition, there are mobility problems in these neighbourhoods, with relatively limited options to use public transportation (Deetman and Mans Citation2011).

Collaborative Learning was developed to support lower SES and migrant families in these neighbourhoods by strengthening parents’ home-based school involvement, the relationship between parents and their child’s teacher, and parenting skills. Ultimately, the aim of Collaborative Learning is to increase the educational performance of the children involved in the intervention (grade 1–4, children are between 4 and 9 years old) and as such increase their development opportunities.

Collaborative Learning is unique in that it centralises the above mentioned two key criteria of effective interventions: (1) treat parents as partners and (2) tailor the intervention to the needs of the parent and the child. First, the intervention was developed in close collaboration with families living in deprived neighbourhoods in Rotterdam. Not only during the development of the intervention, but in particular during its implementation, Collaborative Learning follows a partnership approach. This is also explicitly expressed in the wording used throughout the intervention; the professionals who carry out the intervention are referred to as “accompanists” during the trajectory. More importantly, the professionals strive to create a partnership with these parents. In an attempt to decrease any potential power discrepancies between the professionals and parents, a joint exploration is undertaken as to which school domains should be the focus of the intervention (for example language development or maths development). The eventual domains included in the intervention is collaborative decision. Together, the professional and the parent discuss the intervention options and whether and how these fit in the family context. Subsequently, they also jointly decide on the type of support and guided practice that could benefit the parent the most in enabling them to help and support their child with school (for example stimulating the learning attitude of the child in connection with school or having regular contact with the teacher). Using the Collaborative Learning intervention information folder, parent and professional come up with a plan, detailing strategies that will be used to meet the goals that were chosen. Secondly, by taking the skills, educational and language levels and needs of the parents and children as a starting point, Collaborative Learning is able to accommodate the diversity of family contexts. As such, during the intervention each family works on goals and activities that are specifically tailored to, and to a very large extent, tailored by, them. Most of the activities of the intervention are conducted within the abovementioned home visits, but some activities are organised within the school to strengthen parents’ relationship with the teacher (e.g. teacher-parent meeting).

Purpose of the current study

In order to ultimately reduce the gap in children’s school performances, we need to know whether programs such as Collaborative Learning, that approach parents as partners and are tailored to the needs of children and parents, are able to achieve the proximal goals of improving lower SES parents’ involvement with school and their parenting behaviour. After being developed and implemented in the field for five years, in 2016 Collaborative Learning was recognised by the Netherlands Youth Institute as theoretically sound, meaning that, based on theories and existing empirical knowledge, the theoretical underpinning of the intervention makes the effectiveness of the intervention plausible. Following this recognition, in 2017 preparations for investigating the empirical effectiveness of the intervention started. The current study is the culmination of these efforts. In the current study we scrutinised whether and to what extent the Collaborative Learning intervention is effective in improving (a) parents’ home-based school involvement, (b) the perceived quality of the relationship parents have with the teacher of their child and (c) parents’ parenting skills (warmth/involvement and reasoning/induction).

Materials and methods

Design

The current study followed a pre-test-post-test quasi-experimental design; an experimental group of families participating in Collaborative Learning were compared with a waiting list control group of families not yet participating. Within six schools, and within each school grade, children from one class were randomly assigned to the intervention condition, whereas children from the other class were assigned to the control condition (e.g. children from group 4a were assigned to the intervention condition, whereas children from group 4b were assigned to the control condition). By assigning children to both the intervention and the control condition within each school, school effects are minimised as much as possible. The families assigned to the intervention group started the intervention immediately after registration. The families in the control group started the intervention four months after registration, which is the average duration of the intervention. At the start and at the end of the treatment/waiting period, parents (or, in some families, other caregivers) in the two conditions were administered a questionnaire including questions on their home-based school involvement, the relationship with the teacher of their child, and their parenting skills during a personal interview.

Participants

Initially, 69 families participated in our study. During the school year 8 families who were assigned to the intervention condition and 5 families who were assigned to the control condition dropped out of the study. Consequently, 56 families were included in the sample at the time of the immediate post-test (nexperimental = 37; ncontrol = 19). Per school between 4–11 families participated in the intervention condition, and 1–4 in the control condition.

Measures

Home-based school involvement was measured using the 13 items from the Family Involvement Questionnaire – Elementary Version (FIQ-E; Manz, Fantuzzo, and Power Citation2004) that tap into home-based involvement (Fantuzzo, Tighe, and Childs Citation2000). Examples of items are: “I spend time working with my child on number skills”. “I talk to my child about how much I love learning new things”. “I see to it that my child has a place for books and school materials” and “I review my child’s schoolwork”. The 13 items are rated on a 4-point Likert-type scale ranging from 1 (rarely occurs) to 4 (always occurs). Cronbach’s alpha for our sample was.78. Evidence of construct validity for the FIQ-E has been reported (Manz, Fantuzzo, and Power Citation2004).

Perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship was measured with 7 items from the Parent- Teacher Involvement Questionnaire-Parent’s version (PTIQ; Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group Citation1995) that tapped into the quality of the relationship with the child’s teacher. Examples of items are: “I enjoy talking with my child’s teacher”, “I feel the teacher cares about my child”, and “I feel comfortable talking with the teacher about my child”. These items are coded on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Cronbach’s alpha for our sample was.83. The validity of the PTIQ has been demonstrated in previous research (Kohl, Lengua, and McMahon Citation2000).

Parenting skills were measured by using two subscales from the Parenting Styles and Dimensions questionnaire (PSD; Robinson et al. Citation1996). The PSD is a 52-item parent-report measure of parenting practices. The PSD has 11 subscales that measure more specific dimensions of parenting. Of these 11 subscales we selected the subscales Reasoning/Induction and Warmth/Involvement, because these were most in line with the goals of the intervention.

Reasoning/induction was measured with 6 items on which parents responded to on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Examples of scale items are: “I explain the consequences of my child’s behavior”, “I give reasons for why rules should be obeyed”, and “I explain to my child how I feel about his or her behavior”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for our sample was.75. Warmth/involvement was measured with 12 items on which parents responded on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from 1 (never) to 5 (always). Examples of scale items are: “I encourage my child to talk about his/her troubles”, “I give praise when my child is good”, “I give comfort and understanding when my child is upset”, “I tell my child I appreciate what my child tries to accomplish” and “I express affection by hugging, kissing, and holding my child”. The Cronbach’s alpha coefficient for our sample was.86. The validity of the PSD has been demonstrated in previous research (Robinson et al. Citation1996).

Background characteristics

Sex of the child was asked to the parents using the following question “What is the sex of your child? Answering options were 0 = boy and 1 = girl.

Family’s educational background was measured with the question “What is the highest educational level that you (your partner) achieved?” Answering options ranged between 1 = elementary school not completed to 9 = post-academic. The highest level of educational attainment was used as the family’s educational background.

Household income was measured by asking the parent what the net monthly income of their household, without tax/child benefits, was. Respondents could indicate the household income in band widths of 1,000 euro, ranging from “less than 1,000 euro” (1) up to “10,000 euro a month or more” (11).

Dutch spoken in the home was included as a dummy variable indicating whether Dutch was the language that was always/mostly spoken within the household (=1) or not (= 0).

Type of caregiver involved. We included a variable indicating which caregiver was involved in the intervention. “Mother” was coded 1, “Father” was coded 2, “Both” was coded 3, and when “other family members” (grandmothers, aunts, stepmothers) were involved this variable was coded 4.

Language functioning. Children’s language functioning was measured using the Peabody Picture Vocabulary Test-III (PPVT-III-NL; Dunn and Dunn Citation2005). The test was conducted while the child was in school. The test leader (fourth author) showed the child a series of pages with four pictures, read aloud a word, and subsequently asked the child to identify the picture corresponding with the word read. This widely used measure can be used with children across different socio-economic backgrounds (Pan et al. Citation2004). Higher scores indicated higher receptive vocabulary. Standard scores were calculated based on the norm scores in the coding manual.

Intervention

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

Collaborative Learning targets parents who (1) live in deprived neighbourhoods, (2) have a child in the first four years of elementary school (grades 1–4) with lagging school performance, and (3) have limited parenting skills or limited skills in stimulating their child’s school development. Furthermore, parents are targeted who (4) are not yet fully proficient in Dutch/who have low Dutch literacy levels, (5) have a low level of education, and (6) have few financial resources. The inclusion criteria are assessed during the intake interview.

Exclusion criteria include: (1) Parents have too little proficiency of Dutch and have no other means of communicating with the accompanist (e.g. through an interpreter); (2) Parents experience excessive levels of stress, due to for example severe financial, mental or health problems, or domestic violence. In these cases, other support is deployed (via the neighbourhood team) and enrolment in the intervention is delayed until the basic conditions for enrolment have been met; (3) Parents have very low levels of mental abilities. For these families, appropriate alternative support is sought (for example, through the neighbourhood team); (4) Parents are not motivated for counselling at home, for example because they solely would like to receive homework guidance; (5) Practical obstacles (e.g. work schedules) hinder parents’ availability to such an extent that the intervention will most likely not be able to be continued.

Phases of the intervention

The intervention consists of three phases: (1) The coordination-phase, (2) The working on goals-phase, and (3) The completion-phase, and all three phases centralise the two key criteria for effective interventions: treating parents as partners and tailoring the intervention to the needs of the parent and the child. The first phase of the intervention consists of six home visits. In this period, the accompanist becomes acquainted with the family and asks the parent(s) how the child performs at school, about the behaviour of the child and the daily structure of the family, and the involvement of the parent in trying to improve the performance or behaviour of the child. During the last home visit of the coordination phase, the accompanist and the parents jointly formulate goals specific to the issue(s) raised during intake, expressed in concrete home-based school involvement support and parenting skills. They also discuss through which actions (“subgoals”) these goals can be met (see the appendix for an overview of the goals and subgoals), and jointly draw up an action plan. On average, three to five main goals are set per family. The (sub)goals and action plan take the current level of knowledge and expertise of the parent as the starting point: they are formulated in such a way that they are practically and substantively feasible.

When the (sub)goals and action plan have been formulated, the second phase “Working on goals” commences. During the home visits in this phase (which have an average length of one hour), the accompanist provides tailored guidance to parents in working on the goals and subgoals in the action plan. Besides providing parents with information about the importance of the targeted skills for children’s school performance, the accompanist offers parents concrete activities for working on the (sub)goals and stimulates them to practice these outside the home visits. These activities are written down in the “Collaborative Learning information folder for parents”. Parents choose an activity from the folder that is appropriate for a specific (sub)goal. For example, the goal “parent gives the child positive attention” includes the following activities in the folder: a quality game, a compliment box, emotion cards and a reward schedule. The accompanist then explains the relevance of the activity for achieving the (sub)goal and discusses how the activity can be enacted. The activity chosen by the parent in the previous home visit will be carried out by the entire family during the next home visit. During this visit, the accompanist links each activity with information about this topic, enabling the family to connect “being knowledgeable” with “being able”. Furthermore, during one of the home visits, the accompanist also prepares the parent for the meeting that he/she will have with the teacher of their child. Beyond preparing the type of questions parents would like to ask the teacher, in practice the accompanist often informs the parents that they are able to ask questions. As such, the accompanist tries to bridge the spheres of home and school. Home visits take place once or twice a week, depending on the family’s needs. The duration of the working on goals-phase depends on the number of goals formulated and the presence of any obstacles in achieving the goals (e.g. due to poor Dutch language skills).

The intervention ends with the completion phase, which consists of a final home visit, an evaluation interview, and an aftercare period. This aftercare involves a re-evaluation by asking how the family is doing with respect to the main intervention goals. If wanted, another home visit is scheduled. With the consent of the parent, the child’s teacher can also be re-approached to check how the child is performing in class. The average duration of the entire process is four months (minimum 3 and maximum 9 months).

Characteristics of the accompanists involved

All accompanists are professionals, who have minimally a bachelor’s degree in Pedagogy or Social Work and are employed by the municipality of Rotterdam. They must follow an intensive two-day training, in which they learn the key elements of the intervention and how to implement these. In addition, throughout the Collaborative Learning trajectories, they attend follow-up trainings and receive supervision. The complete intervention trajectory of one family is guided by one and the same accompanist, enabling them to develop a bond with the family, and to establish a high level of mutual trust.

Procedure

We selected six state-funded primary schools located in Rotterdam South the Netherlands. These six schools were selected because their student population represented the target population of the intervention. In addition, these schools were selected because they had at least two school classes per grade 1–4, allowing us to randomly assign children from one class to the intervention condition and children from the other class to the control condition, in order to minimise school effects.

Prior to the study, all parents with a child in grade 1 to 4 (children aged 4–8) within these schools were informed about the intervention. The teachers were involved in the recruitment process by assessing families that according to them, could benefit from this intervention as well as fell in the target group of the intervention. Subsequently, teachers invited these families to participate in the intervention study.The instruments administered in the current study were incorporated into the intake and evaluation questions by the accompanists and were administered verbally to the parents/caregivers. The pre-treatment measurement was taken at the time of the intake (T0) and the post-treatment measurement was taken during the final home visit (T1). In addition to these questionnaires, children were asked to perform a language test at T0. This test was conducted at school.

Prior to beginning our research activity, the study was approved by the ethical review board of the Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences of the Erasmus University Rotterdam, the Netherlands. All parents provided informed consent for participating in the study.

Analyses

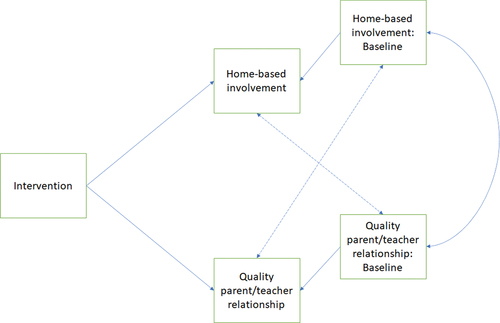

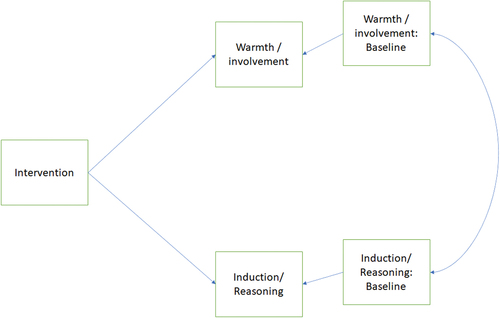

To test the effects of the intervention, two path models were fitted to the data (). We fitted two path models rather than one, as our sample size did not allow us to incorporate all variables into one single path model. The variables were grouped together based on theoretical grounds. In the literature, with respect to children’s school performances, stimulating home environments consist of two dimensions: skills to support one’s child’s school performances (e.g. Leventhal et al. Citation2004; Page et al. Citation2009) and parenting skills (e.g. Bradley et al. Citation2001a; Mistry et al. Citation2008). Our dependent variables home-based school involvement and the perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship fall under the header of “skills to support one’s child school performances”. Our dependent variables warmth/involvement and induction/reasoning fall under the header of “parenting skills”. Model 1 tests the effects of the intervention on parental home-based school involvement and the perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship. Model 2 tests the effect of the intervention on parenting skills, more specifically on parental warmth/involvement, and reasoning/induction. In both models the outcome variables were corrected for their baseline values. To account for the nesting in the data (with families nested in classes, and classes nested in schools) cluster-robust standard errors were calculated. Analyses were run in R using the lavaan package and Full Information Maximum Likelihood (Rosseel Citation2012).

Results

Descriptives on attrition

As mentioned earlier, initially, 69 families participated in our study. During the school year 8 families who were assigned to the intervention condition and 5 families who were assigned to the control condition dropped out of the study. Independent sample t-tests revealed no significant differences between dropouts and those families who remained in our sample on key background characteristics; children’s language scores (t = 0.30; p = .77), gender of the child (t = −0.25; p = .81), educational attainment (t = 0.39; p = .70), household income (t = 0.51; p = .61), language spoken in the home (t = −0.79; p = .43), type of caregiver involved (t = −0.54; p = .59), and parenting stress (t = −0.29; p = .77).

Descriptives on comparability between experimental and control conditions

We checked for significant differences between the experimental and control conditions on key background characteristics, using independent samples t-tests. In addition to the standard socio-demographic and socio-economic background characteristics, we also assessed differences on children’s language scores at enrolment. The rationale for including this variable was to assess whether selection occurred in terms of the type of child that needed the intervention the most. reveals that, regarding relevant background characteristics of children (language test scores: t = −1.13; p = .27; gender: t = −0.28; p = .78, and school grade: t = −0.01, p = .99) and parents (type of caregiver involved: t = −0.67, p = .51; educational attainment: t = −1.31, p = .20, household income: t = 0.94, p = .35; home language: t = 1,69, p = .10), no significant differences between the experimental and control group participants at pre-test were found, suggesting that the two conditions were comparable on relevant background characteristics.

Table 1. Demographic information by condition

Descriptives for our outcome measures

provides an overview of the mean scores and standard deviations on our four effect measures at pre-test. These pre-test scores on the effect measures were similar for the two conditions: in no case were there significant differences between the two groups, implying they were comparable at the start of the experiment.

Table 2. Key outcome variables at pre-test by condition

Parents score an average of 3.08 at T0 on home-based school involvement (theoretically ranging 1–4). Furthermore, the average perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship is relatively high in our sample (4.14 on a theoretical range from 1–5). Finally, parents average scores on their parenting skills are relatively high as well (for warmth and involvement the average score at T0 in our sample is 4.44 on a range of 1–5, whereas for reasoning/induction the average score is a 4.51).

provides an overview of the mean scores and standard deviations on our four effect measures at post-test. Parents score an average of 3.21 at T1 on home-based school involvement, with parents in the intervention group scoring significantly higher than parents in the control group (respectively 3.31 and 3.03). At post-test, the average perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship remains to be relatively high in our sample (4.15), with no significant differences between parents in the intervention versus control group. Finally, parents average scores on their parenting skills at post-test also remain to be relatively high (for warmth and involvement the average score at T1 in our sample is 4.53, whereas for reasoning/induction the average score is a 4.59). No significant differences are found between parents in the intervention versus control group in terms of their parenting skills at post-test.

Table 3. Key outcome variables at post-test by condition

Impact of intervention

The first model to test the impact of the intervention initially did not fit the data sufficiently (Yuan-Bentler corrected χ2(4) = 10.97, p = .27; CFI = .79; RMSEA = .176; SRMR = .096) and modification indices suggested adding covariances between Home-based involvement at T0 and Perceived quality parent/teacher relationship at T1, and between Perceived quality parent-teacher relationship at T0 and Home-based involvement at T1 (see ). After adding these two covariances the model fit the data well (Yuan-Bentler corrected χ2(2) = 1.44, p = .486; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .00; SRMR = .034). The model showed that after correcting for baseline scores on Home-based involvement and Perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship, there was a significant difference between the control and intervention group on Home-based involvement, with the intervention group reporting higher levels of home-based involvement than the control group (b = .25, SE = .12, β = .275, p = .032). The intervention did not have a significant effect on Perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship (b = −.06, SE = .21, β = −.037, p = .781).

The second model (see ) had sufficient fit to the data (Yuan-Bentler corrected χ2(4) = 3.57, p = .468; CFI = 1.00; RMSEA = .000; SRMR = .060), and showed that, after correcting for baseline scores in the outcome variables, there were no significant differences between the control and intervention groups on Warmth/involvement (b = .10, SE = .12, β = .115, p = .408) or Reasoning/induction (b = .08, SE = .14, β = .076, p = .524).

Discussion and conclusion

Although scholars have argued and shown that it is important to adopt a partnership-approach and tailor intervention programmes to the needs and obstacles of involved families, very few programmes actually meet these criteria to achieve sustainable improvements in parental behaviour and child outcomes among lower SES families (see for example the meta-analysis of Fikrat-Wevers, van Steensel, and Arends Citation2021). In the current study, we examined the effectiveness of the Collaborative Learning intervention, which approaches parents as partners and tailors the programme to the family’s needs and context. Specifically, we examined whether Collaborative Learning was successful in achieving the proximal goals of improving parents’ home-based school involvement, their parenting skills, and the perceived relationship with their child’s teacher. Our findings revealed that participation in the intervention was not associated with increases in the perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship nor in parenting skills. However, our results do indicate that participation in the intervention was associated with improvement, albeit small, in home-based school involvement. Increases in home-based school involvement have important implications for children’s school performances. Amongst others, high levels of home-based school involvement have been associated with children’s motivation to learn, their level of attention, task persistence, receptive vocabulary skills (Fantuzzo et al. Citation2004) and grade point averages (Wang and Sheikh‐Khalil Citation2014).

For parents who were involved in the Collaborative Learning intervention no increases were detected in the perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship nor in parenting skills. With respect to the findings for the perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship, it might be the case that no increases were detected because only one home visit was explicitly devoted to the parent-teacher relationship. Our findings may suggest that one home visit is not enough to significantly change the perceived relationship parents have with the teacher of their child. An alternative explanation is that the intervention not only led to improved knowledge about what can be expected from the teacher, but also to a more critical stance towards the school and the teacher in specific. This could explain why the perceived quality of the relationship between parent and teacher did not improve. With respect to the findings for parenting skills, it is important to re-iterate that the families in both the intervention and the control condition scored relatively high on our two measures of parenting skills at our baseline assessment. That the intervention did not improve parenting skills might therefore reflect little room for improvement, which limits our ability to detect intervention effects.

Our findings support the idea that a partnership approach and the provision of personalised support by means of home visits enable achieving improvements in home-based school involvement amongst lower SES families. During the Collaborative Learning intervention, the accompanist and parent jointly formulated goals to be worked on and jointly drew up an action plan. The intervention trajectory was guided by one and the same accompanist, which enabled the accompanist to develop a bond with the family he or she worked with and establish a high level of mutual trust. Furthermore, the (sub)goals and action plan incorporated the current level of knowledge and expertise of the parent as the starting point, making these goals practically and substantively feasible. In line with previous research (e,g., Noar, Benac, and Harris Citation2007), our findings suggest that these strategies facilitate the effectiveness of the intervention – albeit only in terms of small gains on home-based school involvement.

It is important to note that interventions taking a partnership approach and providing personalised support by means of home visits, are relatively costly; tailoring an intervention to the needs and obstacles of the family requires the involvement of skilled professionals. In addition, the trajectory is often quite labour intensive. Nevertheless, the ability to increase home-based school involvement amongst families in deprived neighbourhoods is a key instrument in enhancing lower SES parents’ capacity to promote child development and therefore ultimately reduce the gap in children’s school performances. Such gains might outweigh the financial costs of these interventions (Heckman Citation2008).

Some limitations of the current study should be mentioned here. First of all, the sample size of our study is small. In the years prior to our data collection, in total more than 200 families received the intervention, and in total 22 schools registered families for Collaborative Learning. Based on these numbers, we were confident in collecting a large pool of participating families. However, two changes in the context of the intervention hindered recruitment and led to our more modest sample size: one on a municipality level and one on a methodological level. First, our data collection took place in a newly selected deprived neighbourhood within Rotterdam South, in which there was no “brand awareness” of the intervention yet, which made it relatively more difficult to recruit families. Second, given the aim of investigating the effectiveness of the intervention, schools could only participate if they had at least two school classes per grade, and when we were thus able to randomly assign classes to the intervention or control condition. Consequently, we had to reject some schools that did indicate interest to participate in the intervention but could not meet this criterion. Although our sample size was sufficient to conduct the analyses reported in this study, whether we have enough power to detect an effect depends on the (unknown) true effect size. Given the small size of our sample, there is a chance that the significant finding yielded in our study is an incidental finding. We therefore recommend future studies to replicate our findings with larger sample sizes.

A second limitation of the current study pertains to the reporters for our instruments. The instruments were administered verbally to caregivers by the accompanists who delivered the intervention. Consequently, our study relies on the accuracy with which the accompanists were able to note our respondents’ answers. Under the assumption that the accompanists accurately reported the answers of our respondents, it might be the case that the answers provided by the families are biased due to a tendency for socially desirable answers. In this light we recommend future studies to make use of observational measures of parents’ behaviour towards their child (e.g. parental sensitivity) to obtain a more objective understanding of these behaviours, and of any improvements yielded in these behaviours due to the intervention.

Third, our findings are based on one post-test that was conducted immediately after the intervention was completed/the waiting period was over. As such, we do not know how stable the effects we found are and we do not know whether and to what extent sleeper effects exist. It is however, promising to see that in their qualitative study of Family Learning Workers in Scotland, Macleod and Tett (Citation2019) noted how making use of the knowledge and resources available in families and approaching parents as “experts on their own children” (p. 181), resulted in long-term changes in parental behaviour. That said, more research is needed to determine whether the effectiveness of the intervention remains to be visible over a longer period of time.

Finally, our study examined the effectiveness of Collaborative Learning on its proximal variables, namely parents’ home-based school involvement, parents’ perceived relationship with their child’s teacher and their parenting skills. We were not able to assess whether the observed increase in parents’ home-based school involvement was associated with more distal effects, that is, whether stronger home-based school involvement relates to better school performances. The reason for this is that we did not obtain permission from the schools and parents to collect data on children’s school performances beyond the first post-test. We made additional requests after the first post-test, but – with the COVID-19 pandemic in full force and schools being overburdened with the switch to online education, there were no resources available to contact all parents, ask for permission, and collect the data. We recommend future studies to assess whether the proximal effect found in the current study also results in better school performance.

Conclusion

The intervention programme Collaborative Learning was set up to improve parents’ home-based school involvement, their parenting skills, and the perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship, to ultimately improve children’s school performances and, more generally, their development opportunities. Collaborative Learning incorporated two important criteria to be effective: a partnership approach and provision of personalised support by professionals who are extensively trained. In the current study we assessed the effects of Collaborative Learning on its proximal goals. Although no gains were witnessed in terms of the perceived quality of the parent-teacher relationship or in parenting skills, our study did find that participation in the intervention was associated with small gains in home-based school involvement. This outcome is encouraging for practitioners, programme developers, and policymakers, because it implies that, under the conditions of a partnership approach and the provision of personalised support, efforts to support and strengthen the capacities of lower SES parents to promote child development can be fruitful.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Renske Keizer

Renske Keizer, PhD, is a full professor in Family Sociology at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences. She focuses on the role that families play in strengthening, maintaining, or weakening social inequalities. Her research straddles sociology, pedagogical sciences, demography, and developmental psychology.

Roel van Steensel

Roel van Steensel, PhD, is a professor of reading behavior at the Department of Language, Culture, and Communication at the Faculty of Humanities, VU University Amsterdam. He is also an associate professor of educational sciences at the Erasmus School of Social and Behavioral Sciences, Erasmus University Rotterdam. His research focuses on reading development from the preschool period through secondary education, and the role of education and the home.

Joran Jongerling

Joran Jongerling, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in Methodology and Statistics at Tilburg University, The Netherlands. His research is on Intensive Longitudinal Methods and Analysis, Bayesian Statistics, SEM, Psychometrics, and Multilevel Analysis.

Talitha Stam

Talitha Stam, PhD, is a Haitian-Dutch sociologist with over ten years of experiences in ethnography in and around schools. Currently, she works as senior advisor for the Dutch Education Council and co-supervises a PhD Candidate on Syrian-born children with a refugee background.

Brian P. Godor

Brian P. Godor, PhD, is an Assistant Professor in Educational Sciences at Erasmus University Rotterdam, The Netherlands. His teaching emphasizes learning theories, teacher competencies, and assessment. His research focuses on teacher competencies and socioemotional development in adolescents in sport settings.

Nicole Lucassen

Nicole Lucassen, PhD, is endowed professor in Child and Family Studies at the Erasmus University Rotterdam, Erasmus School of Social and Behavioural Sciences. Her expertise includes child poverty, interrelations within family systems, and growing up in diverse contexts.

References

- Abdul-Adil, J. K., and A. D. Farmer Jr. 2006. “Inner-city African American Parental Involvement in Elementary Schools: Getting beyond Urban Legends of Apathy.” School Psychology Quarterly 21 (1): 1.

- Altintas, E. 2016. “The Widening Education Gap in Developmental Childcare Activities in the United States, 1965–2013.” Journal of Marriage and Family 78 (1): 26–42.

- Applyrs, D.-L. M. (2018). “Family Engagement: The Perspectives of Low-Income Families on the Family Engagement Strategies of Urban Schools.” Education Doctoral. Paper 350.

- Azzolini, D., P. Schnell, and J. R. Palmer. 2012. “Educational Achievement Gaps between Immigrant and Native Students in Two “New” Immigration Countries: Italy and Spain in Comparison.” The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 643 (1): 46–77.

- Borra, R., R. Van Dijk, and R. Verboom, Eds. 2016. Cultuur En Psychodiagnostiek: Professioneel Werken Met Psychodiagnostische Instrumenten. Houten: Bohn Stafleu van Loghum.

- Bower, H. A., and D. Griffin. 2011. “Can the Epstein Model of Parental Involvement Work in A High-minority, High-poverty Elementary School? A Case-study.” Professional School Counseling 15 (2): 2156759X1101500201.

- Bradley, R. H., and R. F. Corwyn. 2002. “Socioeconomic Status and Child Development.” Annual Review of Psychology 53: 371–399.

- Bradley, R., R. Corwyn, M. Burchinal, H. McAdoo, and G. Coll. 2001b. “The Home Environments of Children in the United States, Part II: Relations with Behavioral Development through Age Thirteen.” Child Development 72: 1868–1886.

- Bradley, R. H., R. F. Corwyn, H. P. McAdoo, and C. García Coll. 2001a. “The Home Environments of Children in the United States Part I: Variations by Age, Ethnicity, and Poverty Status.” Child Development 72 (6): 1844–1867.

- Carpentieri, J. D. 2012. Family Learning: A Review of the Research Literature. London: NRDC.

- Cheadle, J. E., and P. R. Amato. 2011. “A Quantitative Assessment of Lareau’s Qualitative Conclusions about Class, Race, and Parenting.” Journal of Family Issues 32 (5): 679–706.

- Conduct Problems Prevention Research Group (1995). Technical reports for the construct development for the measures for Year 2 outcome analyses. Unpublished technical report.

- Conger, R. D., K. J. Conger, and M. J. Martin. 2010. “Socioeconomic Status, Family Processes, and Individual Development.” Journal of Marriage and Family 72 (3): 685–704.

- CPB (Dutch Central Planning Agency) (2019). Verschillen in leerresultaten tussen basisscholen. [ Differences in school performances between primary schools]. https://www.cpb.nl/sites/default/files/omnidownload/CPB-Notitie-19feb2019-Verschillen-in-leerresultaten-tussen-basisscholen.pdf

- De Vries, M., N. Moeken, and F. Kuiken. 2015. Effect van de VoorleesExpress: Een Onderzoek Naar de Effecten van de VoorleesExpress op de Taalontwikkeling, de Taalomgeving En het Leesplezier van Drie- tot Achtjarigen. Amsterdam: Universiteit van Amsterdam.

- Deetman, W. J., and J. Mans (2011). “Kwaliteitssprong Zuid: Ontwikkeling Vanuit Kracht: Eindadvies van Team Deetman/Mans over Aanpak Rotterdam-Zuid.” Team Deetman/Mans: Gemeente Rotterdam [Quality Leap South: Development from Strength: Final Advice from Team Deetman/Mans about Approach Rotterdam-South].

- Desforges, C., and A. Abouchaar. 2003. The Impact of Parental Involvement, Parental Support and Family Education on Pupil Achievement and Adjustment: A Literature Review. Vol. 433. London: DfES.

- Dunn, L. M., and L. M. Dunn. 2005. (translation by L. Schlichting) .Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Pearson.

- Epstein, J. L., M. G. Sanders, B. S. Simon, K. C. Salinas, N. R. Jansorn, and F. L. Van Voorhis. 2009. School, Family, and Community Partnerships: Your Handbook for Action. Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

- Ermisch, J., M. Jantti, and T. M. Smeeding. 2012. From Parents to Children: The Intergenerational Transmission of Advantage. New York: Russell Sage.

- Fantuzzo, J., C. McWayne, M. A. Perry, and S. Childs. 2004. “Multiple Dimensions of Family Involvement and Their Relations to Behavioral and Learning Competencies for Urban, Low-income Children.” School Psychology Review 33 (4): 467–480.

- Fantuzzo, J., E. Tighe, and S. Childs. 2000. “Family Involvement Questionnaire: A Multivariate Assessment of Family Participation in Early Childhood Education.” Journal of Educational Psychology 92 (2): 367.

- Fikrat-Wevers, S., R. van Steensel, and L. Arends. 2021. “Effects of Family Literacy Programs on the Emergent Literacy Skills of Children from low-SES Families: A Meta-analysis.” Review of Educational Research 91 (4): 577–613.

- Fishel, M., and L. Ramirez. 2005. “Evidence-based Parent Involvement Interventions with School-aged Children.” School Psychology Quarterly 20 (4): 371.

- Forster, A. G., and H. G. van de Werfhorst. 2020. “Navigating Institutions: Parents’ Knowledge of the Educational System and Students’ Success in Education.” European SociologicalReview 36 (1): 48–64.

- Freeman, M. 2010. “‘Knowledge Is Acting’: Working‐class Parents’ Intentional Acts of Positioning within the Discursive Practice of Involvement.” International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education 23 (2): 181–198.

- Halgunseth, L., A. Peterson, D. R. Stark, and S. Moodie. 2009. Family Engagement, Diverse Families, and Early Childhood Programs: An Integrated Review of the Literature. Washington DC: National Association for the Education of Young Children.

- Heckman, J. J. 2008. “The Case for Investing in Disadvantaged Young Children.” CESifo DICE Report 6 (2): 3–8.

- Henderson, A. T., and K. L. Mapp (2002). A new wave of evidence: The impact of school, family, and community connections on student achievement. Annual synthesis 2002. Texas: National Center for Family and Community Connections with Schools.

- Huyts, P. M., and M. H. Groeneweg. 2016. Samen Leren: Van Huis uit Kansen Creëren. Capelle aan den Ijssel: Bestenzet Printing.

- Jago, R., S. J. Sebire, G. F. Bentley, K. M. Turner, J. K. Goodred, K. R. Fox, S. Stewart-Brown, and P. J. Lucas. 2013. “Process Evaluation of the Teamplay Parenting Intervention pilot: Implications for Recruitment, Retention and Course Refinement.” BMC Public Health 13 (1): 1–12.

- Jeynes, W. 2012. A meta-analysis of the efficacy of different types of parental involvement programs for urban students. Urban Education 47(4): 706–742.

- Kalil, A. 2014. “Inequality Begins at Home: The Role of Parenting in the Diverging Destinies of Rich and Poor Children.” In Diverging Destinies: Families in an Era of Increasing Inequality, edited by A. Ed Paul, S. M. McHale, and A. Booth, 63–82. New York: Springer.

- Keizer, R., C. J. van Lissa, H. Tiemeier, and N. Lucassen. 2020. “The Influence of Fathers and Mothers Equally Sharing Childcare Responsibilities on Children’s Cognitive Development from Early Childhood to School Age: An Overlooked Mechanism in the Intergenerational Transmission of (Dis) Advantages?” European Sociological Review 36 (1): 1–15.

- Kohl, G. O., L. J. Lengua, and R. J. McMahon. 2000. “Parent Involvement in School Conceptualizing Multiple Dimensions and Their Relations with Family and Demographic Risk Factors.” Journal of School Psychology 38 (6): 501–523.

- Lareau, A. 1996. “Assessing Parent Involvement in Schooling: A Critical Analysis.” In Family-school Links: How Do They Affect Educational Outcomes, edited by A. Booth and J. F. Dunn, 57–64. New York and London: Routledge.

- Lareau, A. 2002. “Invisible Inequality: Social Class and Childrearing in Black Families and White Families.” American Sociological Review 67 (5): 747–776.

- Lee, J. S., and N. K. Bowen. 2006. “Parent Involvement, Cultural Capital, and the Achievement Gap among Elementary School Children.” American Educational Research Journal 43 (2): 193–218.

- Leventhal, T., M. Selner-O’Hagan, J. Brooks-Gunn, J. Bingenheimer, and F. Earls. 2004. “The Homelife Interview from the Project on Human Development in Chicago Neighborhoods: Assessment of Parenting and Home Environment for 3- to 15-year-olds.” Parenting: Science and Practice 4 (2–3): 211–241.

- Macleod, G., and L. Tett. 2019. “‘I Had Some Additional Angel Wings’: Parents Positioned as Experts in Their Children’s Education.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 38 (2): 171–183.

- Manz, P. H., J. W. Fantuzzo, and T. J. Power. 2004. “Multidimensional Assessment of Family Involvement among Urban Elementary Students.” Journal of School Psychology 42 (6): 461–475.

- Manz, P. H., C. Hughes, E. Barnabas, C. Bracaliello, and M. Ginsburg-Block. 2010. “A Descriptive Review and Meta-analysis of Family-based Emergent Literacy Interventions: To What Extent Is the Research Applicable to Low-income, Ethnic-minority or Linguistically-diverse Young Children?” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 25: 409–431.

- Masarik, A. S., and R. D. Conger. 2017. “Stress and Child Development: A Review of the Family Stress Model.” Current Opinion in Psychology 13: 85–90.

- Mattingly, D. J., R. Prislin, T. L. McKenzie, J. L. Rodriguez, and B. Kayzar. 2002. “Evaluating Evaluations: The Case of Parent Involvement Programs.” Review of Educational Research 72 (4): 549–576.

- McLanahan, S. 2004. “Diverging Destinies: How Children are Faring under the Second Demographic Transition.” Demography 41 (4): 607–627.

- Mistry, R., J. Biesanz, N. Chien, C. Howes, and A. Benner. 2008. “Socioeconomic Status, Parental Investments, and the Cognitive and Behavioral Outcomes of Low-income Children from Immigrant and Native Households.” Early Childhood Research Quarterly 23 (2): 193–212.

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2016. Parenting Matters: Supporting Parents of Children Ages 0-8. Washington, DC: National Academies Press. doi:https://doi.org/10.17226/21868.

- Noar, S. M., C. N. Benac, and M. S. Harris. 2007. “Does Tailoring Matter? Meta-analytic Review of Tailored Print Health Behavior Change Interventions.” Psychological Bulletin 133 (4): 673.

- Noble, K. G., M. F. Norman, and M. J. Farah. 2005. “Neurocognitive Correlates of Socioeconomic Status in Kindergarten Children.” Developmental Science 8 (1): 74–87.

- Nzinga-Johnson, S., J. A. Baker, and J. Aupperlee. 2009. “Teacher-parent Relationships and School Involvement among Racially and Educationally Diverse Parents of Kindergartners.” The Elementary School Journal 110 (1): 81–91.

- Page, M., M. Wilhelm, W. Gamble, and N. Card. 2009. “A Comparison of Maternal Sensitivity and Verbal Stimulation as Unique Predictors of Infant Social-emotional and Cognitive Development.” Infant Behavior and Development 33 (1): 101–110.

- Pan, B. A., M. L. Rowe, E. Spier, and C. Tamis-Lemonda. 2004. “Measuring Productive Vocabulary of Toddlers in Low-income Families: Concurrent and Predictive Validity of Three Sources of Data.” Journal of Child Language 31 (3): 587–608.

- Park, S., and S. D. Holloway. 2017. “The Effects of School-based Parental Involvement on Academic Achievement at the Child and Elementary School Level: A Longitudinal Study.” The Journal of Educational Research 110 (1): 1–16.

- Potter, D., and J. Roksa. 2013. “Accumulating Advantages over Time: Family Experiences and Social Class Inequality in Academic Achievement.” Social Science Research 42 (4): 1018–1032.

- Putnam, R. D. 2015. Our Kids. The American Dream in Crisis. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Reardon, S. F. 2011. “The Widening Academic Achievement Gap between the Rich and the Poor: New Evidence and Possible Explanations.” Whither Opportunity 1 (1): 91–116.

- Robinson, C. C., C. H. Hart, B. L. Mandleco, and S. Frost Olsen. 1996. “Psychometric Support for A New Measure of Authoritative, Authoritarian, and Permissive Parenting Practices: A Cross-cultural Perspective XIVth Biennial International Society for the Study of Behavioral Development.“ August 1996, Quebec, Canada.

- Roksa, J., and D. Potter. 2011. “Parenting and Academic Achievement: Intergenerational Transmission of Educational Advantage.” Sociology of Education 84 (4): 299–321.

- Rosseel, Y. 2012. “Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling and More. Version 0.5–12 (BETA).” Journal of Statistical Software 48 (2): 1–36.

- See, B. H., and S. Gorard. 2013. What Do Rigorous Evaluations Tell Us about the Most Promising Parental Involvement Interventions? A Critical Review of What Works for Disadvantaged Children in Different Age Groups. London: Nuffield Foundation.

- Tett, L. 2001. “Parents as Problems or Parents as People? Parental Involvement Programmes, Schools and Adult Educators.” International Journal of Lifelong Education 20 (3): 188–198.

- Thompson, B. 2008. “Characteristics of Parent–teacher E-mail Communication.” Communication Education 57 (2): 201–223.

- van Tuijl, C., P. P. M. Leseman, and J. Rispens. 2001. “Efficacy of an Intensive Home-based Educational Intervention Programme for 4- to 6-year-old Ethnic Minority Children in the Netherlands.” International Journal of Behavioural Development 25: 148–159.

- Von Otter, C. 2014. “Family Resources and Mid‐life Level of Education: A Longitudinal Study of the Mediating Influence of Childhood Parental Involvement.” British Educational Research Journal 40 (3): 555–574.

- Wang, M. T., and S. Sheikh‐Khalil. 2014. “Does Parental Involvement Matter for Student achievement and Mental Health in High School?” Child Development 85 (2): 610–625.