ABSTRACT

Numerous studies highlight the benefits of incorporating creativity in teaching, but practical experience shows that putting these theories and policies into practice often lacks the necessary resources. The current study focuses on three aspects of creativity in teaching: (a) Theoretical – how do policy documents and educational researchers refer to creativity in teaching and what are their recommendations regarding its implementation in the education system? (b) Attitudes – what do teachers know and what are their positions regarding the integration of creativity in teaching? (c) Practical – whether and how teachers use creativity-based practices in their teaching. We conducted a descriptive analysis of 36 teachers’ lesson plan performances and 11 interviews to answer the research questions. Findings revealed a gap between theory and practice: despite the teachers’ positive attitudes about integrating creativity in teaching, many of them did not apply these contents. Ways to minimize this gap between theory and practice are discussed.

Introduction

The 21st century is described as a technological age, leading to dramatic changes in various areas of society, including political, social, educational, and economic changes (Chalkiadaki Citation2018). The changes occur rapidly, and the individual is often faced with unknown and unexpected challenges. Key policy reports from the Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD), in OECD (Citation2018), the National Science Teachers Association (NSTA) in conjunction with the Partnership for 21st Century Skills (Donovan, Green, and Mason Citation2014), along with educational research projects (e.g. Anderson-Patton Citation2009; Wang and Kokotsaki Citation2018; Yu and Subramaniam Citation2017), have argued that the education system needs to develop students’ 21st-century skills, such as: creativity, problem solving, critical thinking, communication, collaboration, and meta-cognition. This paper deals with creative thinking, which is one of the important 21st-century skills (Lucas, Claxton, and Spencer Citation2013).

Creativity in education is at the forefront of education policy in the world. The importance of preparing learners for creative thinking is expressed in international documents such as OECD Education 2030 and UN 2030 (de Vries Citation2021). While policymakers and educators acknowledge the significance of creativity, certain obstacles can create a disparity between its perceived importance and its actual implementation within educational institutions (Makel Citation2009). The current study aims to examine whether and in what way there is a gap between theory, teachers’ attitudes, and practices regarding implementing creativity in teaching. We will refer to these three aspects of creativity among primary school teachers as follow:

(a) Theoretical – how do policy documents and educational researchers throughout the world refer to creativity in teaching and what are their recommendations regarding its implementation in the education system? (b) Attitudes – what do teachers know and what are their positions regarding the integration of creativity in teaching? (c) Practical – whether teachers use creativity-based practices in their teaching as reflected from their lesson plan performances, and how do they actually do it? We will refer to the theoretical aspect of creativity in teaching in our literature review and address the attitudes and practical aspects using empirical research that integrates qualitative and descriptive analysis.

Literature review

Theoretical aspect: creativity in education

Guilford (Citation1950) defined creative thinking as divergent thinking that focuses on providing multiple solutions to a given task, in contrast to convergent thinking that focuses on one solution to a problem. Divergent thinking is characterised by multiple associations in different directions and by original solutions to a given problem. Torrance (Citation1963) suggested three components of creativity: (a) Fluency – the variety of ideas generated about a particular subject in response to stimulus, measured by the number of suggested responses. (b) Flexibility – related to different types of ideas, or the approach to a problem in different ways. Flexibility is measured by the number of different categories of answers or ideas raised. Those with cognitive flexibility are able to transfer from idea to idea. (c) Originality – refers to thinking in a unique way and creating unique actions. Originality is measured by statistical rarity (Silver Citation1997).

In the field of education, it is common to refer to two types of creativity: teaching creatively and teaching for creativity (Brinkman Citation2010; Yu and Subramaniam Citation2017). Teaching creatively refers to the use of different approaches that can arouse curiosity and make learning more interesting and effective by using various instructional methods, such as video, animation, and graphics to achieve teaching goals (Brinkman Citation2010; Wood and Ashfield Citation2008; Yu and Subramaniam Citation2017). Teaching for creativity is a teaching method that aims to develop students’ creative thinking or behaviour (Cremin Citation2009). It requires openness to unconventional and original ideas and dedication of time during class to open-ended questions that allow students to express creative ideas (Brinkman Citation2010).

Educational policies worldwide recognise creativity as a paramount 21st-century skill. Grey and Morris (Citation2022) and numerous previous studies and policy documents have consistently emphasised the integration and implementation of 21st-century skills in teaching (e.g. NACCCE Citation1999; OECD Citation2018; Pellegrino and Hilton Citation2012). Below we discuss some of these documents with a focus on the implementation of creative thinking.

The first document discussed is the OECD (Citation2018) position paper, which offers a vision and some underpinning principles for the future of education systems. According to the OECD position paper, the uncertain future will require today’s students to apply their knowledge in unknown and evolving circumstances. For this, the education system needs to equip them with a broad range of skills, including cognitive and meta-cognitive skills (e.g. creative thinking); social and emotional skills (e.g. self-efficacy), and practical and physical skills (e.g. using new information). This position paper postulates that in order to implement creative thinking in school, teachers should offer students a diverse range of topic and project options. Additionally, teachers need to provide students with the opportunity to suggest their own topics and projects and to support their students’ decision-making process.

Another document that promotes the integration of 21st-century skills into K-12 education is the 21st-century Skills Map (Donovan, Green, and Mason Citation2014). The goals of this map are to illustrate the intersection between 21st-century skills and science and to enable educators, administrators, and policymakers to consider concrete examples of how 21st-century skills can be integrated into core subjects. According to this map, in order to develop creativity in 4th-grade students, teachers should provide tasks in which students examine the ways they use scientific thinking and experimental problem-solving processes in their day-to-day activities such as cooking, gardening, playing strategy games, fixing a bike, or taking care of a pet. For example, as part of a class gardening project, students produce an ongoing podcast to illustrate their processes for determining the ideal conditions for growth, nutrition, and maintenance.

Yu and Subramaniam (Citation2017) have argued that in order to implement creative teaching successfully, a parallel emphasis on teaching creatively and teaching for creativity is necessary because teaching creatively can serve as a stepping stone towards cultivating creativity among students. In other words, teaching for creativity must involve creative teaching. If teachers’ creativity abilities are poor, they will not be able to develop these abilities among their students.

Practical aspect: implementing creativity in teaching

In OCED countries worldwide, such as the US, Australia, Israel, and many European countries, extensive work is being done on the implementation of 21st-century skills in schools; several policy documents have been published on this topic. One of these documents is Future-Oriented Pedagogy (Morgenshtern et al. Citation2018), which is based on an innovative OECD pedagogy model (Citation2013). According to Future-Oriented Pedagogy, schools should focus on developing the skills required for professional life in the 21st-century and integrate them broadly into the curriculum. The document also emphasises that 21st-century skills, such as creativity, must be imparted to teachers.

Although the importance of creativity has been recognised in policy and by teachers, some challenges can lead to a gap between the perceived value of creativity and its presence in schools (Makel Citation2009). Creative teaching is often viewed as valuable but not as a mandatory responsibility of teachers (Beghetto Citation2007). When teachers feel pressured by the system, by standards, and by unmanageable class sizes, it is difficult to integrate creative content into their lessons (Kim Citation2008; Rinkevich Citation2011). Studies have found a lack of training and knowledge of teachers at universities and in teacher education programmes (Kožuh Citation2018); these also constrain the integration of creativity in education (D. Newton Citation2012; Rinkevich Citation2011). A supportive environment is required in order to implement creative thinking in schools and encourage creativity in teaching (L. Newton and Newton Citation2014; Wang and Kokotsaki Citation2018). Teacher preparation programmes should equip teachers with knowledge and skills for creative teaching, and schools should provide professional development opportunities for teachers’ understanding of creative teaching (Anderson-Patton Citation2009). An effective implementation of creative thinking in education also requires examination of teachers’ attitudes about creativity in education (Rinkevich Citation2011).

Summary and research goals

The theory regarding creative thinking in education refers to both teaching creatively and teaching for creativity (Brinkman Citation2010; Yu and Subramaniam Citation2017). These two types of creativity are related and in fact, without teaching creatively, the development of creativity among students is not possible. As discussed above, while researchers and policy documents worldwide encourage teaching creatively and teaching for creativity, experience repeatedly shows that implementation of theory and policy in the field of education is not a simple process and requires an investment of resources that are often lacking (Kožuh Citation2018; Wang and Kokotsaki Citation2018). The current study aims to examine whether and in what way there is a gap between theory, teachers’ attitudes, and teachers’ practices regarding implementing creativity in teaching. We will utilise descriptive analyses of teachers’ lesson plan performances and qualitative analysis of interview responses to examine two research questions: (1) what teachers think about creativity in teaching and (2) if and how they apply creativity-based practices in the lessons they design. These questions will be explored in light of the theory and the policy documents referring to creativity in teaching.

Method

Participants and data collection

Thirty-six elementary teachers (all of whom were female) from five Israeli schools participated in the study. All participants were home-room teachers who teach various subjects (e.g. language, maths, or science) following the Israel National Curriculum. Their seniority was between two and thirty-five years.

The research was approved by the ethics committee of the Israel Ministry of Education. To recruit participants for the study, we used a convenience sampling method that enabled us to reach out to teachers through email messages and social networks and include them as study participants. This sampling method is considered acceptable in qualitative studies that focus on gaining insight into perceptions regarding a particular phenomenon. Teachers who volunteered to participate in the research project signed a consent form and were promised anonymity; names used in this article are pseudonyms. The data collection took place in February 2020.

Teachers were requested to describe a plan for one lesson they recently taught in any subject. Among them, 11 teachers agreed to be interviewed. We performed one semi-structured interview with each teacher, enabling the participants to describe and reflect on how they experienced the phenomenon (Prosser Citation2000). Questions were directly related to each teacher’s perspectives about integrating creativity in teaching and their creativity-based practices. For instance, “Describe the creative teacher in your eyes”. Direct questioning enabled us to understand the reasons for teachers’ perspectives. All interviews were researcher-conducted, recorded in their entirety, and lasted between a half-hour and an hour.

Data analysis

The data analysis contains both descriptive and qualitative analysis as follows: Using descriptive analysis and examining the occurrence or absence of creative content in their papers, we analysed 36 lesson plan performances of teachers. We conducted a descriptive analysis of the teachers’ lesson plans to gather additional insights into creativity-based practices. This approach is considered less biased than relying solely on the information provided by teachers when directly asked. The frequency of papers that included at least one of the components of creative teaching (teaching creatively and teaching for creativity) and a full example of the analysis of one lesson plan performance will be detailed in the results section.

The 11 interviews were analysed qualitatively using the constant comparative method (Strauss and Corbin Citation1997). The study involved three stages of analysis that were conducted as follows:

We read the interview responses several times, both longitudinally for each respondent’s complete interview, and transversely, question by question, to compare the answers given by all respondents to specific questions. These processes were followed so we could obtain an overall picture of the data before breaking it down into categories. This multi-directional analysis enabled us to identify quotations that refer to the teachers’ different experiences about the phenomenon. During this stage of data analysis, we also identified primary categories based on the theoretical literature, along with categories we had developed before the interviews (e.g. the attitudes about developing the creativity of students). We maintained an open mind to find common elements without imposing predetermined categories, as suggested by Marton (Citation1986).

We used a continuous inductive process of content analysis to identify subcategories by spotting words and topics found repeatedly in the interviews. During this stage, we constructed subcategories for each primary category. Construction of the subcategories entailed a process of going back and forth and repeatedly reading the transcripts of the interviews.

We created associations between categories. This stage was characterised by revisiting the categories and subcategories and adjusting the connections between them after further scrutiny.

Results

We present findings about the first research question, dealing with what teachers know and their opinions about integrating creativity into teaching. We then present findings about the second research question, dealing with whether and how teachers use creativity-based practices in their teaching, based on their perception and as reflected from their lesson plan performances. Finally, we draw a model representing the three aspects of creativity in teaching that were surveyed in this study: the theoretical, teachers’ attitudes, and the practical.

First research question: Attitudes about integrating creativity in teaching

This section discusses attitudes about integrating creativity in teaching, identifying two types of creativity: teaching creatively, namely being creative with the range of teaching methods; and teaching for creativity, which refers to devising assignments that teach students to be creative.

Attitudes – teaching creativity

Teachers said that a creative teacher is a teacher that applies a diverse range of methods. For example, Vered mentioned that: “a creative teacher goes beyond frontal teaching, applies a lot of experiential means. It could be videos, images, games. There are many ways for a teacher to be creative”. Vered referred to two components of creativity: fluency and flexibility. That is, using numerous teaching methods borrowed from several categories.

With regard to another interesting finding that came up when the subjects described their picture of a creative teacher, was the contrast between what they described a creative teacher did, which appeared to be unlike the standard methods that most teachers applied. For instance, Ema described a gap between the methods teachers should use in their classrooms and the methods they actually use: “how we teach today – it is simply criminal. Teaching has to change – to become more creative, to introduce a significant upgrade that would keep up with this generation because we are stuck somewhere behind with our books and our conservative ways”’. In the third part of the paper, where we look at the application of creativity in teaching, we shall return to Ema and examine whether the perceptions she expressed are present in her classroom practice.

Attitudes – teaching for creativity

Most teachers believe that it is both possible and essential to develop students’ creativity. Ema is one of the believers, telling us that “it is certainly possible to develop creativity among students. I think it is very important, especially in this generation, that they have everything available at their fingertips and never have to think outside the box or reach beyond the immediate”. Another issue raised is that teachers should be trained and learn new methods to be capable of developing students’ creativity: “of course, you can develop creativity. Maybe you need to learn some techniques, some methods of being creative” (Ema). Some teachers even explicitly mentioned that teachers need to be creative themselves to develop students’ creativity: “you have to be creative about teaching creativity” (Ayelet).

In contrast to the perception that creativity is a trait that can be developed among students, some teachers doubted the possibility of developing creative thinking in the classroom. Tal, for instance, said that she did not “believe that creativity can be developed. It’s a way of thinking. Some people are creative – artists, inventors. Some are more realistic, some are good at acquiring languages, some are inclined toward the humanities, and some are creative. I think you are just born with it”.

Second research question: Creativity-based practices

This section discusses creativity-based practices referring to two types of creativity: teaching creativity, meaning being creative with the range of teaching methods; and teaching for creativity, that is, devising assignments that teach students to be creative. We begin by presenting teachers’ perceptions about creativity-based practices in their teaching, as they told us during the interviews. We then provide a descriptive analysis of lesson plan performances devised by the same teachers and examine whether their perceptions are expressed in these plans.

Creativity-based practices as reflected from the interviews

Teaching creatively

Most of the teachers claimed that they apply a diverse range of methods in the classroom. Alma, for instance, described that she liked to see her students “turn to the computers or to their smartphones, in searching for information … preparing an animal ID, identifying a plant, making observations, taking videos”. Alma’s description exhibits two components of creativity: fluency and flexibility. She applies several methods of teaching from different categories (for instance, observation and online search).

While teachers realised the importance of applying a creative range of methods in their lessons, they also repeatedly mentioned the gap between the ideal and the real, referring to system constraints inhibiting them from teaching creatively. As Einat told us, “You cannot always diversify. It is as if the system won’t let you; it wears you down over time. The need to meet external exam requirements of the Ministry of Education and everything – it is hard to do things differently”. Similarly, Vered said that she tries to integrate creative content in her lessons, but the hard reality of pedagogical standards does not help. She observed that she really tries “to diversify (in teaching methods), but the system, the focusing on students’ achievements, it paralyzes teachers. I feel it personally, too, and it’s a shame. There is a gap between the ideal and the real”. This gap may be the reason that even teachers who perceive themselves to be creative people admit that they cannot express this trait in the classroom. “I am quite open to new ideas; I can find solutions; I can always see more than one path; do I bring this creativity to the lesson? No”, was one of Inbar’s biggest concerns. This gap can also be noticed in the words of Ema, who, when asked to describe a creative teacher, chose a description that was in contrast to standard teaching methods: “how we teach today – it is simply criminal … ”. However, when Ema was asked if she applies a broader range of methods in her own lessons, she replied that “it is so easy to go for the familiar, to walk into class, put everything up on the board and have them write it down. Sometimes you try and diversify, but it’s hard”. Even though Ema believes in teaching creatively, she admits that she often fails to do so. Another factor inhibiting creative teaching methods is the disposition of some teachers who seem reluctant toward change. As Inbar puts it, “some teachers are fixated on their own familiar way of doing things – “if it works, why fix it”’?

Teaching for creativity

An analysis of most teachers’ responses indicates that their lessons include content that can encourage creativity. An example of a lesson that has the potential to encourage students’ creativity by devising assignments that teach students to be creative is reflected in Dorit’s words: “I assigned a team of students to research and examine an issue that they would later teach to the rest of the class. However, not just as a PowerPoint presentation – they had to stage it, to put together a video made up of images that tell the entire story and reconstructs their journey, and they were free to apply any other means they could think of”.

Despite the positive attitudes that teachers hold regarding creativity in teaching and the fact that most of them claimed to be integrating creativity-encouraging content into their lessons, many expressed the complexity surrounding the issue. For instance: Ema graded herself “three out of five in teaching for creativity. I come up with an assignment and I ask them to think outside the box … but I also have a certain notion of what results I expect from them. I should work on my own fixation, consider a wider range of results to expect”. Some teachers simply said their lessons do not help in developing creativity, as reflected in Inbar’s words: “my lessons, at the moment, do not really do much for creativity”, a condition that she associates with the system’s constraints: “I suppose that in order to encourage student creativity, the system has to go through practical changes … you have to build a different learning environment. It could still be a classroom, but how they learn has got to change”.

Creativity-based practices as reflected in lesson plan performances of the teachers

As mentioned above, in addition to the interviews, creativity-based practices were examined in the current study by descriptive analysis of the teachers’ lesson plans. In a similar vein to the analysis of interviews, the descriptive analysis focused on two aspects of teaching creativity: teaching creatively and teaching for creativity. A lesson plan performance illustrating how the analysis was conducted is detailed below:

The teachers’ assignment was to plan a lesson about sites in Jerusalem. Examining the teaching creatively angle in this case, the teacher planned first to have the students complete tasks set out in a worksheet and then engage them in two different kinds of games. The teacher’s lesson, therefore, contains the fluency component, as it consists of three different methods. It also contains the element of flexibility because the methods belong to two categories – worksheet and play. However, the originality component was missing, as the methods applied here were commonly spotted elsewhere in the 36 lesson plan performances that the study examined. When we focused on teaching for creativity, we observed that every student team was tasked with finding an online image of some notable site in Jerusalem and then creatively describing it to another team member. The teacher did not limit the students in their approach – they were free to choose a pictorial, verbal, or any other form of description that came to mind. This invitation to diversify can be considered a creativity-encouraging component. A task that requires finding an image and offering ways to describe it came up only once in all of the lesson plan performances examined, so this lesson can be positively labelled for originality.

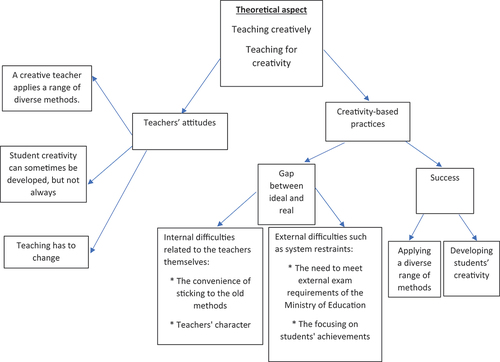

lists the most frequently applied methods used by the teachers. For the sake of brevity, less frequent creativity-related content was not detailed but still counted in the quantified sum. The table indicates that a significant percentage of the lesson plan performances teach creatively (64%) and teach for creativity (61%); they also contained the creativity components of fluency and flexibility. Some of the teachers’ outcomes contained rare creative content, showing up in only one or two cases, and were also labelled for the originality component. We can see that approximately half of the lesson plan performances examined contained the two types of creativity in teaching: teaching creatively and teaching for creativity. shows that while many teachers apply creative content in their teaching, a significant portion does not. This inability (or unwillingness) to apply creative content in teaching can be partially explained by difficulties implementing the recommendations listed in policy documents that promote creativity in teaching – an explanation that was supported by the interviews that we conducted. The three aspects of creativity in teaching that this study has examined – the theoretical aspect, teachers’ knowledge and opinions, and integration of creativity in teaching – are summarised in . As reflected in the figure, theory refers to two types of creativity in education: teaching creatively and teaching for creativity. It can also be seen that teachers think that creativity should be integrated into teaching, and it is possible to develop students’ creativity. Indeed, some succeed in doing so, but others encounter various difficulties related to internal or external factors.

Figure 1. Diagram of the three aspects of creativity in teaching: theoretical, attitudes, practical.

Table 1. Summary of teaching methods and approaches for developing student creativity as spotted in lesson plans (N = 36).

Discussion

The purpose of the current study was to examine teachers’ attitudes regarding the integration of creativity in teaching. The research also examined whether and how teachers use creativity-based practices in their teaching. To determine this, we looked to the teachers’ perceptions as reflected in their lesson plan performances. Finally, we aimed to examine the association between the three aspects of creativity in teaching that we examined in this study: theoretical, attitudes and practice.

As for attitudes regarding the integration of creativity in teaching, the teachers themselves defined a creative teacher as someone who applies diverse methods in order to make learning more interesting, exciting, and effective. This definition is in line with the literature (Brinkman Citation2010; Wood and Ashfield Citation2008; Yu and Subramaniam Citation2017). However, the interviews did not reflect the originality component of creativity, as teachers did not refer to novel teaching practices. Additionally, while most teachers believed that creativity is a feature that can be developed, some disagreed with this conception and argued a contrary position. Research suggests that this concept of the inability of teachers to develop creativity in their students is common among teachers, who tend to believe that only select students can be creative, due to their inborn traits (Aljughaiman and Mowrer-Reynolds Citation2005; Bereczki and Kárpáti Citation2018). For instance, teachers misperceive creativity to be mainly related to intellectual characteristics and artistic properties (Mullet et al. Citation2016; Paek and Sumners Citation2019). However, studies have found that high intelligence and artistic ability do not necessarily characterise a creative person (Kim Citation2008; Runco and Albert Citation1986). This misconception is one of the most significant barriers to fostering creativity in the classroom (Paek and Sumners Citation2019).

Some teachers argued that today’s teaching methods must become more creative and must be updated for today’s students. This perception was previously discussed in other studies indicating that creativity is valued in policy and by teachers (Rinkevich Citation2011). Despite the positive attitudes about integrating creativity in teaching, there are numerous challenges that accompany the implementation of creativity in teaching (Ahmadi and Besançon Citation2017; Huang, Lee, and Yang Citation2019; Kim Citation2008; Kožuh Citation2018). These challenges can result in a discrepancy between the perceived value of creativity and its absence from schools (Makel Citation2009). This discrepancy was also revealed in the present study. Here, teachers indicated that “there is a gap between the ideal and the real”. According to the participants who were interviewed, this gap is a result of both external factors, such as system constraints (focusing on students’ achievements and the need to meet external exam requirements of the Ministry of Education) and internal factors, such as the convenience of sticking to the old methods.

Difficulties in implementing creativity-based practices in teaching were also reflected in the descriptive analysis of the teaching products. Only about half the lesson plan performances integrated the two types of creativity in teaching – teaching creatively and teaching for creativity – and only a small proportion of them contained novel content. In spite of the challenges to practicing creativity in teaching, as stated above, it should be noted that over sixty percent of the lesson plan performances included at least one type of creativity in teaching and most interviewees noted that they use creative content in their lessons. It can be said that most teachers use creativity-based practices in teaching. However, for some teachers, the challenges accompanying these practices prevent them from applying creativity in their teaching.

To conclude, the current study’s innovation focuses on the relationships between the three aspects of creativity in teaching: theoretical, attitudes, and practice. Similar to previous research (e.g. Wang and Kokotsaki Citation2018), the current study found that teachers’ attitudes towards integrating creativity in teaching are generally positive. However, examining creativity-based practices revealed a gap between the practical aspect of creativity and the other two aspects examined in this study (theoretical and teachers’ attitudes). While some teachers went on to apply creative content to their teaching, based on their perceptions of creativity and as reflected from their lesson plan performances, a significant portion of the teachers did not apply this content for various reasons mentioned herein. This failure to apply creativity content matches similar findings in previous studies (e.g. Anderson-Patton Citation2009; D. Newton Citation2012).

Limitations and future directions

The limitations of this study related to its focus only on primary school teachers. However, teachers working with different age groups or in different regions in Israel may have different views on creativity in teaching. Therefore, future studies should include teachers from all levels of education. Furthermore, considering the qualitative nature of the current study, future studies are recommended to examine the emphases highlighted in this study using a quantitative approach. This quantitative approach enables the generalisation of results to a wider population. The study is also limited because it does not examine the impact of creativity-based teaching on students’ outcomes. We recommend that future studies investigate these outcomes to gain more insight into the effectiveness of these practices. Finally, it is worthwhile to include more objective measures, such as classroom observations, in future studies to assess creativity in teaching, in addition to self-report measures.

Pedagogical implications

The gap between theory and practice found in this study should draw attention to teachers’ misconceptions regarding the development of creativity in students. If teachers believe that creativity is a feature that cannot be developed among students, then while they may be creative in their teaching, they will not likely teach for creativity. As teachers’ attitudes regarding creativity are similar worldwide (D. Newton Citation2012), these findings are important to understanding the relationships between teachers’ attitudes and practices regarding creativity in teaching.

The study also found that the originality component of creativity was absent from the interviews and hardly reflected in the lesson plan performances. This finding points to the difficulty of integrating originality in teaching. Because innovation is so crucial in facing 21st-century challenges, organisers and facilitators of creativity training programmes must consider the complexity of applying originality in teaching so they can further encourage teachers’ originality. By investing teachers with the freedom to investigate and adapt lessons to meet their students’ distinct needs and preferences, will help cultivate a supportive atmosphere that values teacher autonomy, one that can encourage a stronger willingness to embrace innovative ideas.

Additionally, the study shows that internal and external factors make it difficult for teachers to apply creative content in their lessons. To contribute to a broader application of creativity-based practices in teaching, it is worthwhile to adopt different methods of dealing with some of the internal and external difficulties this study has identified. For instance, in coping with the internal difficulty of the convenience of sticking to the old methods, training programmes can focus on the personal benefits teachers stand to gain from using creative content in teaching. Among these benefits are a more exciting teaching experience and personal and professional growth. An enabling environment in schools is required to deal with external difficulties, such as system constraints. This recommendation aligns with previous studies (e.g. Wang and Kokotsaki Citation2018).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Rotem Maor

Rotem Maor has a Ph.D. in education and is a Lecturer at David Yellin College of Edu-cation in Israel. Rotem’s research areas include 21st century skills, teaching, and learning.

Nurit Paz-Baruch

Nurit Paz-Baruch is a lecturer at the science and technology education program at the School of Education, Bar-Ilan University, Israel. Nurit’s principal research areas include individual differences in mathematics, 21st century skills, self-regulated learning, creativity, and cognitive abilities.

Zemira Mevarech

Zemira Mevarech is Full Professor of Education at the School of Education, Bar Ilan University, Israel. She served as Head of the School of Education, Dean of the Social Sciences faculty, Vice Rector of Bar Ilan University, and Chief Scientist of the Israeli Ministry of Education. Zemira’s research deals with metacognitive and creativity methods of teaching. Prof. Mevarech was the principal investigator and research director for PISA 2000, 2006 in Israel.

Niv Grinshpan

Niv Grinshpan is a research assistant at the School of Education, Bar Ilan University, Israel. Niv is engaged in the implementation of 21st century skills in teaching and learning.

Rotem Levi

Rotem Levi is a research student at the School of Education, Bar Ilan University, Israel. Rotem is engaged in the implementation of 21st century skills in teaching and learning.

Alex Milman

Alex Milman is a research student at the School of Education, Bar Ilan University, Israel. Alex is engaged in the implementation of 21st century skills in teaching and learning.

Sarit Shlomo

Sarit Shlomo is a research assistant at the School of Education, Bar Ilan University, Israel. Sarit is engaged in the implementation of 21st century skills in teaching and learning.

Michal Zion

Michal Zion is Full Professor of Education and the Head of the Science Education Center, the School of Education, Bar-Ilan University, Israel. Michal’s main research areas include: 21st century skills, teaching and learning in inquiry-based learning environments, and teachers’ professional development.

References

- Ahmadi, N., and M. Besançon. 2017. “Creativity As a Stepping Stone Towards Developing Other Competencies in Classrooms.” Education Research International (1). https://doi.org/10.1155/2017/1357456.

- Aljughaiman, A., and E. Mowrer-Reynolds. 2005. “Teachers’ Conceptions of Creativity and Creative Students.” Journal of Creative Behavior 39 (1): 17–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.2162-6057.2005.tb01247.x.

- Anderson-Patton, V. 2009. “Re-Educating Creativity in Students: Building Creativity Skills and Confidence in Pre-Service and Practicing Elementary School Teachers.” In Creativity and the Child: Interdisciplinary Perspectives, edited by W. C. Turgeon, 83–97. Oxford: Inter-Disciplinary Press.

- Beghetto, R. A. 2007. “‘Does Creativity Have a Place in Classroom Discussions? Prospective teachers’ Response Preferences.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 2 (1): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2006.09.002.

- Bereczki, E. O., and A. Kárpáti. 2018. “Teachers’ Beliefs About Creativity and Its Nurture: A Systematic Review of the Recent Research Literature.” Educational Research Review 23:25–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2017.10.003.

- Brinkman, D. J. 2010. “Teaching Creatively and Teaching for Creativity.” Arts Education Policy Review 111 (2): 48–50. https://doi.org/10.1080/10632910903455785.

- Chalkiadaki, A. 2018. “A Systematic Literature Review of 21st Century Skills and Competencies in Primary Education.” International Journal of Instruction 11 (3): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.12973/iji.2018.1131a.

- Cremin, T. 2009. “Creative Teachers and Creative Teaching.” Creativity in Primary Education 11 (1): 36–46..

- de Vries, H. 2021. “Space for STEAM: New Creativity Challenge in Education.” Frontiers in Psychology 12:586318.. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.586318.

- Donovan, L., T. D. Green, and C. Mason. 2014. “Examining the 21st Century Classroom: Developing an Innovation Configuration Map.” Journal of Educational Computing Research 50 (2): 161–178. https://doi.org/10.2190/EC.50.2.a.

- Grey, S., and P. Morris. 2022. “Capturing the Spark: PISA, Twenty-First Century Skills and the Reconstruction of Creativity.” Globalisation, Societies & Education 22 (2): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/14767724.2022.2100981.

- Guilford, J. P. 1950. “Creativity.” American Psychologist 5 (9): 444–454. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0063487.

- Huang, X., J. C. K. Lee, and X. Yang. 2019. “What Really Counts? Investigating the Effects of Creative Role Identity and Self-Efficacy on teachers’ Attitudes Towards the Implementation of Teaching for Creativity.” Teaching and Teacher Education 84:57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2019.04.017.

- Kim, K. 2008. “Underachievement and Creativity: Are Gifted Underachievers Highly Creative?” Creativity Research Journal 20 (2): 234–242. https://doi.org/10.1080/10400410802060232.

- Kožuh, A. 2018. “Creativity: Didactic Challenge of a Modern Teacher.” Sodobna Pedagogika 69 (3): 156–169.

- Lucas, B., G. Claxton, and E. Spencer. 2013. “Student Creativity in School: First Steps Towards New Forms of Formative Assessment.” OECD Education Working Papers 86:1–46. https://doi.org/10.1787/5k4dp59msdwk-en.

- Makel, M. 2009. “Help Us Creativity Researchers, you’re Our Only Hope.” Psychology of Aesthetics, Creativity, and the Arts 3 (1): 38–42. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0014919.

- Marton, F. 1986. “Phenomenography: A Research Approach to Investigate Different Understandings of Reality.” Journal of Thought 21 (3): 28–49.

- Morgenshtern, O., I. Pinto, A. Vegerhof, T. Hoffman, and S. Loutaty. 2018. “Future-Oriented Pedagogy 2 Trends, Principles, Implications and Applications: A Summary and Applications Map.” Jerusalem: Ministry of Education. https://meyda.education.gov.il/files/Nisuyim/eng_fop2summary.pdf.

- Mullet, D. R., A. Willerson, K. N. Lamb, and T. Kettler. 2016. “Examining Teacher Perceptions of Creativity: A Systematic Review of the Literature.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 21:9–30. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2016.05.001.

- NACCCE (National Advisory Committee on Creative and Cultural Education). 1999. “All Our Futures: Creativity, Culture and Education”. London: DfEE.

- Newton, D. 2012. “Recognizing Creativity.” In Creativity for a New Curriculum, edited by L. Newton, 108–119. London: Routledge.

- Newton, L., and D. Newton. 2014. “Creativity in 21st Century Education.” Prospects 44 (4): 575–589. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11125-014-9322-1.

- OECD. 2013. “Trends Shaping Education”. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- OECD (Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development). 2018. “The Future of Education and Skills: Education 2030”. Paris: OECD Publishing.

- Paek, S. H., and S. E. Sumners. 2019. “The Indirect Effect of teachers’ Creative Mindsets on Teaching Creativity.” The Journal of Creative Behavior 53 (3): 298–311. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.180.

- Pellegrino, J. W., and M. L. Hilton. 2012. “Education for Life and Work: Developing Transferable Knowledge and Skills in the 21st Century”. Washington, DC: National Academy of Sciences.

- Prosser, M. 2000. “Using Phenomenographic Research Methodology in the Context of Research in Teaching and Learning.” In Phenomenography, edited by J. Bowden and E. Walsh, 34–46. Melbourne: RMIT University Press.

- Rinkevich, J. L. 2011. “Creative Teaching: Why it Matters and Where to Begin.” The Clearing House: A Journal of Educational Strategies, Issues & Ideas 84 (5): 219–223.. https://doi.org/10.1080/00098655.2011.575416.

- Runco, M. A., and R. S. Albert. 1986. “The Threshold Theory Regarding Creativity and Intelligence: An Empirical Test with Gifted and Nongifted Children.” Creative Child & Adult Quarterly 11 (4): 212–218.

- Silver, E. A. 1997. “Fostering Creativity Through Instruction Rich in Mathematical Problem Solving and Problem Posing.” International Journal on Mathematics Education 29 (3): 75–80. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11858-997-0003-x.

- Strauss, A., and J. M. Corbin. 1997. “Grounded Theory in Practice”. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Torrance, E. P. 1963. “The Creative Personality and the Ideal Pupil.” Teachers College Record 65 (3): 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146816306500309.

- Wang, L., and D. Kokotsaki. 2018. “Primary School teachers’ Conceptions of Creativity in Teaching English as a Foreign Language (EFL) in China.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 29:115–130. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2018.06.002.

- Wood, R., and J. Ashfield. 2008. “The Use of the Interactive Whiteboard for Creative Teaching and Learning in Literacy and Mathematics: A Case Study.” British Journal of Educational Technology 39 (1): 84–96. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8535.2007.00699.x.

- Yu, C. X., and G. Subramaniam. 2017. “A Mentoring Approach for Developing Creativity in Teaching.” Malaysian Journal of ELT Research 14 (2): 1–19.