ABSTRACT

This study focuses on the quality of teacher–student interactions and feedback in teaching English as a foreign language (EFL). Data consisted of 65 video-recorded lessons from 13 classrooms in two lower-secondary schools, and were coded with Classroom Assessment Scoring System–Secondary. Four cases were selected and analysed for feedback practice based on teachers’ use of first language (L1: here, Norwegian) and target language (L2: here, English) in EFL lessons. Teacher–student interactions were characterised by mid quality of emotional support and high quality of classroom organisation, but relatively low quality of instructional support. The results revealed an interdependence between quality of feedback and instructional dialogue, yet there appeared to be difficulties in supporting students’ internal feedback and self-regulation. Engaging in extended feedback dialogues in the L2 seemed to be a central challenge facing the EFL teachers. The results provide knowledge for teacher education and teachers’ facilitation of student learning.

Introduction

Real-time interactions are fundamental to the formation of teacher–student relationships (Hafen et al., Citation2015; Pennings et al., Citation2014). As such, interactions lie at the heart of understanding potentials and impediments to student learning. For more than a century, classroom interactions have been analysed by using systematic observation, and important contributions to the research-based knowledge of educational and pedagogical practices have been made (Hardman & Hardman, Citation2017). Observation systems are suitable for identifying quality dimensions of teaching but vary to the degree all aspects of a dimension are captured (Bell, Dobbelaer, Klette, & Visscher, Citation2019), for example, classroom feedback. Although feedback has been identified as a core component in formative assessment (Black & Wiliam, Citation1998; Sadler, Citation1989), an explicit focus has been devoted to dialogic feedback for the benefit of the regulation of students’ learning processes (Adie, van der Kleij, & Cumming, Citation2018; Black & Wiliam, Citation2009; Steen-Utheim & Wittek, Citation2017). In this article, feedback is defined as ‘information provided by an agent (e.g., teacher, peer, book, parent, self, experience) regarding aspects of one’s performance or understanding’ (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007, p. 81) with the aim to support further learning and development (Sadler, Citation1989).

For assessment to be formative, information about a gap between the actual level and the target level should be used to alter the gap (Black & Wiliam, Citation1998; Ramaprasad, Citation1983; Sadler, Citation1989). An integrated understanding of the relationship between formative and summative aspects for assessment is important, and formative assessment has been suggested to be meaningfully embedded in pedagogy (Black & Wiliam, Citation2018). Whilst summative assessment involves summarising the achievement status of a student, formative assessment is related to how judgements about the quality of a student’s performance or work are used to shape and improve student learning (Sadler, Citation1989).

When examining feedback and teacher–student interactions in English as a foreign language (EFL) classrooms, teachers’ use of target language is relevant. Foreign language teachers have the opportunity of alternating between languages, especially if there is a shared first language, which has the potential to reduce anxiety (Bruen & Kelly, Citation2017) and foster learning (Then & Ting, Citation2011). Foreign language teaching is characterised by the presence of two (or more) languages (Ellis, Citation2012), namely, L1 (first language; in this study: Norwegian) and L2 (target language; in this study: English). EFL teachers provide feedback to students in both the L1 and L2 (Burner, Citation2015). However, the second language acquisition literature has mainly researched the role of corrective feedback (Li, Citation2010). Second language acquisition research has also been conducted with focus on the relationship between explicit and implicit corrective feedback and found benefits of metalinguistic explanation (Ellis, Loewen, & Erlam, Citation2006). However, recent research has found that the absence of a shared L1 could pose challenges as well as create opportunities in multilingual classrooms (Illman & Pietilä, Citation2018).

Standardised measurement tools for coding interaction quality are hypothesised to benefit from being analysed in combination with time sampling of L1 and L2 use when studying foreign language teaching interactions and feedback practice. The present study uses a systematic observation tool to study the quality of teacher–student interactions and feedback in teaching EFL. The tool, Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS), is a framework that describes levels of quality in classroom interactions to enhance student learning across subjects from early childhood education to secondary education (Pianta, Hamre, & Mintz, Citation2012; Pianta, La Paro, & Hamre, Citation2008). The CLASS Secondary (CLASS-S) was originally developed for educational contexts in the US (e.g. Casabianca et al., Citation2013; Hafen et al., Citation2015), but usage has extended internationally (e.g. Gamlem, Citation2019; Gamlem & Munthe, Citation2014; Malmberg, Hagger, Burn, Mutton, & Colls, Citation2010). Validation studies of the CLASS-S have been conducted in Finland (Virtanen et al., Citation2018) and Norway (Westergård, Ertesvåg, & Rafaelsen, Citation2019).

Previous CLASS-S studies have identified a need to study the quality of interactions between teachers and students during lessons and what teachers do with the material they have (Allen et al., Citation2013). Interactions that foster autonomy and cognitive stimulation have been identified as central when measuring interaction quality (Malmberg et al., Citation2010). This has led researchers to develop observation systems for different purposes and with varying degrees of subject specificity (Bell et al., Citation2019; Hardman & Hardman, Citation2017). Former CLASS-S studies have typically included emphasis on mathematics and science (Allen et al., Citation2013; Casabianca, Lockwood, & McCaffrey, Citation2015; Culp, Martin, Clements, & Lewis Presser, Citation2015; Gamlem, Citation2019; Malmberg et al., Citation2010), and a mix of a variety of subjects (Gamlem & Munthe, Citation2014; Virtanen et al., Citation2018). Nevertheless, a few studies have an explicit focus on a subject discipline or sub-discipline, for example, algebra (Bell et al., Citation2012; Casabianca et al., Citation2013). A few studies have included EFL lessons (Gamlem & Munthe, Citation2014; Virtanen et al., Citation2018) and emphasised feedback quality (Gamlem & Munthe, Citation2014). Yet, there seems to be a gap in knowledge about the quality of teacher–student interactions to support learning combined with time sampling of L1 and L2 to understand foreign language interactions and feedback in lessons. Thus, this study examines the quality of teacher–student interactions in EFL lessons with focus on feedback practice, analysed with the CLASS-S and cases of L2 use:

What characterises teacher–student interactions and feedback practice in EFL lessons in lower-secondary school?

Teacher–student interactions and feedback in EFL classrooms

In past decades, feedback in educational research has been discussed predominantly in the field of assessment (Black & Wiliam, Citation1998; Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007; Sadler, Citation1989; Shute, Citation2008). More recently, however, scholars have called for a fusion between formative assessment and self-regulated learning (Andrade & Brookhart, Citation2016; Panadero, Andrade, & Brookhart, Citation2018). The marriage between these two traditions evokes the centrality of self-regulatory processes of feedback. Self-regulated learning is defined as ‘a self-directive process by which learners transform their mental abilities into academic skills’ (Zimmerman, Citation2002, p. 65). This is particularly pertinent in responsive pedagogy, defined as ‘the recursive dialogue between the learner’s internal feedback and external feedback provided by significant others’ (Smith, Gamlem, Sandal, & Engelsen, Citation2016, p. 1). The concept of responsive pedagogy encompasses a feedback practice that is concerned with activating students as active agents of their own learning processes (Smith et al., Citation2016; Vattøy & Smith, Citation2019). Teachers (and peers) are identified as significant others in responsive pedagogy, as they are important facilitators of learning processes (Gamlem, Citation2019).

Much of the literature on feedback in foreign language and second language literature has been concerned with corrective feedback in which a learner is informed by positive and negative input regarding what is acceptable in the L2 (Li, Citation2010), although more recent studies have a focus on formative assessment. The implementation of feedback practices informed by assessment for learning has been found challenging in an examination-driven system in Hong Kong (Lee & Coniam, Citation2013). In a Chinese context, prospective EFL teachers’ perceptions of an assessment for learning experience have been connected to their tendency to adopt a deep approach to learning (Gan, Liu, & Yang, Citation2017). In Norwegian lower-secondary schools, a gap has been identified between EFL teachers’ intentions and students’ experiences of assessment for learning. A shared language of assessment for learning and opportunities for teachers and students to interact during feedback processes have been suggested as possible bridges (Burner, Citation2015).

The impact of feedback can be both positive and negative for student learning, which makes it important to identify the criteria for feedback with positive effects on students’ learning. Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007) proposed a model of feedback to enhance learning on the claim that effective feedback answers three questions: ‘Where am I going? How am I going? Where to next?’ These questions work at four levels (task, process, self-regulation, self). Hattie and Timperley argued that feedback about the processing of the task and self-regulation appears to be the most effective in terms of deep processing and mastery of tasks. As feedback interactions are often realised in moments of contingency (Black & Wiliam, Citation2009), they can be difficult to measure. The web of classroom interactions and communications is an inherently complex one. Therefore, observing and interpreting classroom interactions with accuracy poses a considerable challenge (Archer, Kerr, & Pianta, Citation2015). Yet, the use of observation systems provides scholars with an approach to measure teacher–student interactions and teaching as basis for further improvement (Bell et al., Citation2019; Hardman & Hardman, Citation2017).

The moments in which feedback occurs are critical moments where students’ self-beliefs are formed. In teaching EFL, self-efficacy beliefs can be connected to capabilities related to academic success or failure in the face of subject-specific tasks, for example, speaking in the L2 in lessons. Self-efficacy refers to personal judgements of one’s capabilities to exercise influence and execute actions to reach desired goals (Bandura, Citation1997). The domain-specific level opens to the notion that students’ cognitive, affective and behavioural patterns might differ in a specific subject or discipline because of its nature or characteristics. Furthermore, students’ capacities for self-regulation and self-efficacy are interconnected because the cognitive aspects of self-regulation cannot be separated from motivational aspects of self-efficacy (Bandura, Citation1997). Students’ beliefs in their capabilities to exercise influence over events that affect their lives are central to their sense of agency (Bandura, Citation1989). Teachers, as significant others, thus play a crucial role in providing students with feedback and support (Smith et al., Citation2016).

The study

Sample

The sample consisted of nine EFL teachers (aged 30–59 years; Mage = 40.2; SD = 8.7) and their classes (n = 13). Eight of the nine teachers were female. The average teaching experience was 9.3 years (Min: 3.5 years – Max: 20 years), and the average amount of credits in higher education English for teachers was 44 credits (Min: 0 credits – Max: 65 credits). The teachers were recruited from two lower secondary schools (i.e. Year 8–10; 13–15-year-olds) in Norway.

Initial contact was made with the head teachers, and an invitation was passed on to the teachers and the students. Further, a letter of invitation with an informed consent form was sent to the teachers, students and parents/caregivers. In total, 13 classes (represented by the nine teachers) voluntarily agreed to participate in the study. Observations of five EFL lessons from each classroom (n = 65 lessons) were made. All observations were video recorded. The length of recorded lessons ranged from 39 minutes to 62 minutes (M = 50.06, SD = 5.53, SE = .69). On average, the class sizes consisted of 24 students (ranging from 23 to 26 students). One student withdrew from the study and was seated outside the frame of the cameras.

Procedure

An ethical approval from the Norwegian Centre for Research Data was obtained before the start of data collection. Data were collected using two video cameras. The primary camera of analysis was a handheld wide-angled lens camera with high resolution and balanced-optical stabilising functions, which secured high-quality footage. The second video camera was placed on a tripod, facing the students and capturing the whole class. The handheld camera was operated by the researcher and followed the teacher with close attention to teacher–student interactions, whilst simultaneously paying attention to the classroom context. The researcher moved in the back of the classroom, following the teacher’s movement by zooming and carefully moving around. The handheld camera was connected to a wireless audio receiver from a collar-clip microphone, which was connected to the teacher. The collar-clip microphone allowed high-quality audio recordings of the teacher’s speech (teacher–student interactions) during lessons. Thus, the collar-clip microphone allowed teacher–student conversations to be collected. Use of two video cameras strengthened the reliability of the audio-visual material, because the researchers accessed the full class context as well as interactions at individual levels.

The teachers were asked to carry out their teaching as normal, ensuring that lessons were authentic in terms of the teachers’ daily practice and to minimise additional workload. The data collection included a wide range of EFL lessons in terms of curriculum, content, learning aims, contexts, seating plans and activities. The rationale behind the minimal-interference model was based on considerations that classroom feedback interactions occur in a multitude of situations and require no planning or means of facilitation. However, observations (both live and video-recorded) might cause changes in teacher behaviour, reducing the validity of the ratings (Curby, Johnson, Mashburn, & Carlis, Citation2016).

Measure

The CLASS-S manual (Pianta et al., Citation2012) was used to score the quality of teacher–student interactions in the EFL classrooms (n = 65 lessons). The CLASS-S operationalises teacher–student interactions to enhance student learning into three broad domains: emotional support; classroom organisation; and instructional support. The domains are divided into 11 dimensions (Pianta et al., Citation2012), explained in .

Table 1. Descriptions of Classroom Assessment Scoring System Secondary domains and dimensions (Pianta et al., Citation2012)

In addition, a global measure, student engagement, measures students’ overall activity level in lessons. The CLASS-S dimensions have indicators with behavioural markers that make the basis for scoring on a 7-point Likert scale. Score 1–2 express low quality, 3–5 express mid quality and 6–7 express high quality. The 65 video-recorded lessons were scored for three cycles for each lesson (approx. 15 minutes each), resulting in 195 score cycles for each of the 11 dimensions of the CLASS-S (). The mean values for the time range of the three cycles were: Cycle 1, Mtime = 16.77 minutes (SD = 1.77); Cycle 2, Mtime = 16.68 minutes (SD = 1.80); and Cycle 3, Mtime = 16.63 minutes (SD = 2.13).

One of the researchers was CLASS-S certified and the other researcher became certified during the coding process. A random selection (10%) of the videos were double scored. Double scoring strengthens inter-rater reliability, and inter-rater score was above 80% in accordance with the CLASS-S manual.

Cronbach’s α was calculated to determine reliability of the CLASS-S dimensions. Cronbach’s α estimates for all CLASS-S dimensions was calculated to be: α = .85. This shows overall strong inter-item consistency.

The CLASS-S dimensions, quality of feedback and instructional dialogue were examined to analyse feedback practice in the four cases of the present study. Quality of feedback is in CLASS-S defined as ‘the degree to which feedback expands and extends learning and understanding and encourages participation’ (Pianta et al., Citation2012, p. 93). Further, quality of feedback is based on the following indicators: feedback loops; scaffolding; building on student responses; and encouragement and affirmation. For example, the indicator, building on student responses, has the behavioural marker ‘expansion’, in which the teacher expands on students’ responses. An example of such an interaction in the mid-range is provided here:

So, there are both freshwater and saltwater crocodiles in Australia?

Yes, and did you know saltwater crocodiles can reduce their heartrate to two or three beats a minute and stay underwater for more than an hour?

You mean they can’t breathe underwater?

No, they breathe air just like people.

Feedback loops that lack persistence and follow-ups are scored in the low range. An Initiation–Response–Evaluation (IRE) loop typically asks for known information and has the function of testing students’ knowledge (Mehan, Citation1979). By contrast, an Initiation–Response–Follow up (IRF) pattern will be more formative, as it will push the conversation forward (Sinclair & Coulthard, Citation1975).

Instructional dialogue is defined as ‘the purposeful use of content-focused discussion among teachers and students that is cumulative, with the teacher supporting students to chain ideas together in ways that lead to a deeper understanding of the content’ (Pianta et al., Citation2012, p. 101). The indicators are cumulative content-driven exchanges, distributed talk and facilitation strategies.

Data analysis

The data analysis consisted of descriptive analyses with emphasis on mean, minimum and maximum scores, standard deviation, standard error, and skewness and kurtosis values. Subsequently, Pearson’s r product-moment correlations were performed to check for significant relationships between the dimensions of CLASS-S (Pianta et al., Citation2012).

The time sampling procedure for language use (L1 and L2) was conducted using two digital timers: one for first language use (L1) and one for target language use (L2). The distribution of minutes and seconds was calculated in percentages. First, the mean values of all the cycles were calculated. Second, the mean values of the individual teacher’s language use across the three cycles was calculated. None of the teachers spoke an L3 or L4 during the recorded lessons.

Further, four cases were selected based on the amount of L2 use in lessons. These cases were selected based on minimum and maximum mean values of L2 use and further analysed for feedback practice. In addition, the CLASS-S dimensions and the model of feedback to enhance learning by Hattie and Timperley (Citation2007) were used to analyse teacher–student interactions and feedback levels in the four cases.

Results

The descriptive statistics of the CLASS-S dimensions for the 65 lessons are presented in . The mean scores ranged from 1.06 (negative climate) to 5.85 (productivity). A low score for the negative climate dimension indicated low levels of negativity (e.g. sarcasm, anger, irritability) in the lessons. All the dimensions, except from productivity and negative climate, had acceptable skewness and kurtosis values. The mean scores for each of the three domains, emotional support (M = 4.12, SD = .68), classroom organisation (M = 6.18, SD = .55) and instructional support (M = 2.81, SD = .63), were in the mid, high and low range, respectively. High scores for behaviour management and productivity, as well as a low score for negative climate, showed that teacher–student interactions were characterised by good behaviour and where learning time was maximised with little down time and little negative behaviour. Two of the dimensions for emotional support, positive climate and teacher sensitivity, were scored in the mid-range, yet the regard for adolescent perspectives dimension was scored lower. For the instructional support dimensions, the analysis and inquiry dimension had the lowest score. Instructional dialogue and content understanding were scored in the low range, whilst quality of feedback and instructional learning formats scored in the low end of mid. The low scores for the instructional support domain indicated a struggle to engage in teacher–student interactions that facilitate and activate clear learning goals, deep understanding of the content, opportunities for self-regulation and higher-order thinking, as well as feedback dialogues that expand student comprehension.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for CLASS-S dimensions

presents the bivariate correlations between the dimensions of the CLASS-S, as well as the global measure of student functioning: student engagement (Pianta et al., Citation2012). The results showed a range of significant correlations at p < .01 from r = .33 to .78. The strongest significant correlations among the 12 dimensions were between: quality of feedback and instructional dialogue (r = .78, p < .01); behaviour management and productivity (r = .74, p < .01); content understanding and instructional dialogue (r = .73, p < .01); and positive climate and teacher sensitivity (r = .70, p < .01). The empirical data supported a strong interdependence between quality of feedback and instructional dialogue. Moreover, the strong correlation between content understanding and instructional dialogue identified the relevance of cumulative content-driven exchanges to encourage deep conceptual understanding. The correlation between positive climate and teacher sensitivity suggested that teachers’ social and academic responsiveness and sensitivity thrived from a positive climate characterised by close rapport between teachers and students. Regard for adolescent perspectives, which was the outsider of the emotional support domain, had strongest correlation with instructional dialogue, which supported the idea of student perspectives in dialogues.

Table 3. Correlations among CLASS-S dimensions

Cases representing L2 use and feedback practice

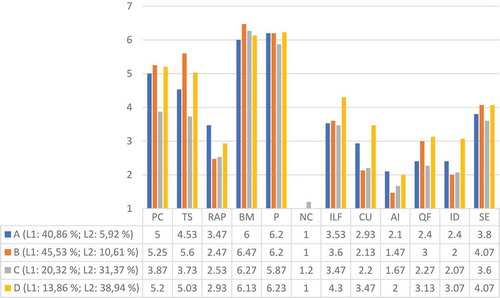

Four teachers were selected as cases and further analysed in terms of feedback practice. Teachers A and B had the lowest use of L2, whilst Teachers C and D had the highest uses of L2, which means that Teachers C and D spoke significantly more English in their EFL lessons. The cases were analysed specifically regarding the two dimensions of quality of feedback and instructional dialogue, which were the dimensions with the highest correlation. The data material showed that the teacher with the highest percentage of L2 had the lowest percentage of L1 (Teacher D), whereas, conversely, the teacher with the lowest percentage of L2 had the highest percentage of L1 (Teacher A). illustrates the language use of the four teachers combined with the quality score in the CLASS-S dimensions.

Figure 1. Comparison of CLASS-S dimensions and cases of L1 and L2 use (n = 4 cases, 25 lessons)

From , the two teachers with lowest use of L2 also had the highest use of L1: Teacher A (L1: 40.86%; L2: 5.92%) and Teacher B (L1: 45.53%; L2: 10.61%). The percentages only accounted for teachers’ language use during lessons (e.g. Teacher A was silent or produced non-speech sounds 53.22% of the mean of lessons). Quality of feedback and instructional dialogue scores are discussed later.

Til dømes så er inuittane dei einaste som bur i igloar. [For example, the Inuit people are the only ones living in igloos.]

Gjer dei det? [Do they?] (Student looks surprised)

Men det er ikkje sikkert dei bur i igloar heile tida. [But they probably don’t live in igloos all the time.]

Er det kaldt inne i den? [Is it cold in there?] (Student looks up at teacher)

Går det an å finne ut det. Korleis det går an å bu inne i ein iglo? [It’s something you could find out. How is it possible to live inside of an igloo?]

Ja. [Yes.]

Kvifor bur du inne i iglo da? [Why would you live inside of an igloo?]

Fordi det liksom er i le mot vinden? [Because it’s like sheltered from the wind?]

Ja, og kva finst mest av på Grønland? [Yes, and what is in very large quantities in Greenland?]

Igloar. [Igloos.]

Snø. [Snow.]

Ja, is og snø som er hardpakka. Så dei tek i bruk av ein av ressursane fordi det er ikkje så frykteleg mykje tre der. [Yes, hard-packed ice and snow. So, they utilise one of their resources, because there isn’t an awful amount of trees there.]

Men bur dei – Finst det Eskimoar framleis då? [But do they live – Does there still exist any Eskimos?]

Det – det kan du søkje om, veit du. Sjå om du klarar å finne ut. Men det bur nok – Men folketalet på Grønland. [That – that is something you could search for, you know. See if you can figure it out – But the population of Greenland –]

– går ned. [– is declining.]

– er nok ikkje – er nok ikkje så kjempestort i forhold til kor stort landet er i størrelse. Og det er fordi det er dekka av is. [ – is probably not – probably not vast compared with how large the country is in size. And it’s because it’s covered by ice.]

Men er der nokon som bur der i igloar? [But is there anyone living there in igloos?]

Her har dei vindauge og alt. [Here they have windows and everything.] (Student looks at a picture of an igloo)

Ja, mhm. Altså korleis du skal bygge ein iglo. For den er ganske stor. Kan du stå oppreist i den eller ligg du i den som i ei snøhole? Lagar du mat i den? [Yes, mhm. So how do you build an igloo. Because it’s quite big. Can you stand upright inside of it or do you lay down in it like a snow cave? Do you cook in it?]

Analyses highlighted that Teacher A (TA) was below the average mean score of the 65 lessons in terms of quality of feedback (M = 2.4) and instructional dialogue (M = 2.4). The excerpt, however, was scored in the mid-range and was collected from a lesson where the aim was to find facts about an indigenous people and later present one fact for two minutes. Student 1 and Student 2 were working on the topic of the Inuit people. Teacher A visited the group who were working on their computers and immediately started with an example, referring to a picture of an igloo on Student 1’s screen. Feedback was predominantly provided at the task level (correctness, and control that work is completed), whilst feedback about the processing of the task (process level) remained unclear and generic although the teacher asked the students to search for information online and asked scaffolding questions. However, the teacher provided extended opportunities for dialogue and both students joined in the conversation. The excerpt showed evidence that feedback was provided at the self-regulation level in terms of the questions being posed by the teacher and the students. The teacher also asked supportive questions for extended opportunities for reflection. The extract exemplified a formative assessment practice in teacher–student feedback interactions in the L1. However, the whole dialogue was entirely in the L1, which provided students with little exposure to L2 use and opportunities for talking.

Og ein tur til Stockholm der hovudkvarteret til Nobelprisen er. [And a trip to Stockholm where the headquarters of the Nobel Prize are located.]

Ja, flott. [Yes, great.]

Han er – er – kva heiter det? [He is – is – what is it called?]

Eh, spent? [Er, excited?]

Spent etter å ha besøkt det. [Excited after the visit.]

Veldig fint at de kan spørje kvarandre. Det er veldig bra. For då kan de bruke – [Very nice that you can ask each other. That’s very good. Because then you can use –]

(Teacher abruptly terminates conversation, and goes on to next group)

Ferdig? [Done?]

(Student 3 and 4 nod)

Og det var greitt? Det var ikkje nokon ord som var vanskelege? De forstod innhaldet og det var greitt? [And it was okay? No words you found difficult? You understood the content and it was okay?]

(Students 3 and 4 nod)

Ja. De kan starte med å skrive ned glosene i arbeidsboka dykkar. [Yes. You can start writing down the glossary in your rough books.]

(Teacher quickly moves on to a new group)

De er også ferdige? [You too are done?]

Mhm.

Og det gjekk heilt fint? Det var ikkje nokon ord som gjorde at de ikkje forstod innhaldet og – ? Det var greitt? [And it was fine? There wasn’t any words that made you not understand the content and – ? It was okay?]

(Student has his eyebrows raised, looks at Student 5 before answering:) Ja. [Yes.]

Bra. Då kan de også byrje å skrive ned glosene i arbeidsboka dykkar. [Good. Then you can also start by writing down the glossary in your rough books.]

(Teacher moves on to next group)

Teacher B (TB) had the highest percentage of L1 use (45.53%) and scored in the lower mid-low range for quality of feedback (M = 3) and in the low range for instructional dialogue (M = 2). Teacher B occasionally monitored the learning of students and provided encouragement, but the dialogues were not cumulative or content-driven with frequent follow-ups. The feedback interactions were rarely in the L2, which was the language to be learnt in the lesson. In the excerpt, which scored in the low range, Teacher B encouraged peer scaffolding, but the feedback patterns were characterised by IRE loops. The aim of the lesson was to translate texts before continuing with writing down glossary. Teacher B walked up to Student 1 and Student 2, who were translating a text from L2 to L1 in pairs. The feedback provided was at the task level and with the aim to control. The feedback was generally more controlling and approving/disapproving rather than fostering learning, and the students were passive in teacher–student interactions. This exemplified a summative assessment practice which was more concerned with summing up the achievement status of students in the L1. The conversation was also entirely in the L1.

The two teachers with the highest L2 were Teacher C (L1: 20.32%; L2: 31.37%) and Teacher D (L1: 13.86%; L2: 38.94%), and they were the teachers with the lowest use of L1 of the four cases.

(Student 1 rolls the dice and looks puzzled at the verb [to be]) Okay. Erm – Ah! To be, was, been.

I would like you to make a sentence, [Student 1].

I was on a road trip yesterday. (Student does not look at teacher)

She was, yes.

Okay, ein, to, tre. [one, two, three] (rolls dice again and counts the squares). Build. Build, built, built. Var det rett? [Is that correct?] (Student 1 asks Student 2, ignoring the teacher who stands behind her)

Ja. [Yes.]

In a sentence, please.

Arg! (Student slaps her own head)

You hurry too much!

I built my sentence correct.

Yes, you did. You’re a kind girl. A kind girl.

(Teacher moves on to next group)

(Student rolls the dice) Keep, kept, kept. Er det ikkje? [Is it not?] (Student looks at teacher)

Do you agree with her? (Teacher looks at other students in the group) I do. Mm. In a sentence?

Erm, I keep –

– keep all the secrets to myself. (Teacher interrupts Student 3)

I keep my letters –

You keep your letters – Where do you keep your letters?

I keep my letters on my shelf.

Yes. Good.

Teacher C had a high use of L2, but quality of feedback (M = 2.27) and instructional dialogue (M = 2.07) were both scored in the low range. Both dimensions were below the average value of the nine teachers in the 65 lessons. The quality of feedback dimension requires follow-up exchanges that drive learning forward. Teacher C had many IRE-sequences when engaging in conversational exchanges with students. The content of these exchanges was typically on the surface. The students were working in groups of four on an irregular verb game. The game consisted of conjugating irregular verbs and providing a sentence. This activity came at the end of the lesson as a reward from the teacher to the students for their efforts, but the students seemed bored and uninterested. Student 1 rolled the dice and looked puzzled at the verb. Teacher C’s response, ‘You’re a kind girl’, is an example of feedback about the self as a person instead of feedback about the task, and Student 1 slapping her own head indicated irritability in teacher–student interactions. Feedback was mostly approving/disapproving and controlling, and very little information was provided as to how students could process the task, despite that the full conversation was in the L2. Overall, the extract exemplified a summative assessment practice for teacher–student interactions occurring in the L2.

Okay, S1, you can start telling about Romeo and Juliet.

Erm, okay, it was a gunfight at the start of the film at the gas station. Romeo’s friends were there, and they were going to fill the tank on the car.

Mm.

And then Tybalt and his friends came and start a gunfight with them.

Okay, why did they start a gunfight with them?

Er – Okay, eg veit ikkje. [I don’t know.](Student 1 looks frustrated)

Well, were they – Why do you start shooting at someone?

Their family names *wasn’t friends – ?

No, they were –

– enemies.

Enemies. Yes, they were actually lifelong enemies. [Tells the other student Student 2]: So, [Student 2], what I’m doing now to [Student 1], I want you to continue doing. You are going to continue asking questions.

(Note. The asterisk * marks the structure as ungrammatical)

Teacher D had the highest average mean value of quality of feedback (M = 3.13) and instructional dialogue (M = 3.07) of the four cases and scored in the lower part of the mid-range. Teacher D also had the highest amount of L2 use (38.94%). Teacher D was persistent in the attempts at engaging students in L2 peer dialogues, and often encouraged with ‘In English, please’ when students talked in the L1. At one point, Student 1 switched to L1, but Teacher D continued in the L2 with follow-up questions. The students were retelling the plot from the 1996 film, Romeo + Juliet, to each other in pairs. There were some cumulative content-driven exchanges as follow-ups in the L2, and the teacher monitored the groups. The teacher scaffolded the dialogues and had high expectations of use of L2 for the students. The final utterance showed that feedback was not only given about the task but also about the process. Engaging students in peer dialogues in this manner showed that Teacher D acknowledged and supported the students as active participants. The excerpt illustrated characteristics of a formative assessment practice in teacher–student interactions in the L2.

Discussion

This study examined the quality of teacher–student interactions and feedback in EFL lessons and suggests that teachers’ L2 use in lessons is vital for understanding feedback interactions to support learning in teaching EFL. The interdependence between feedback and dialogue found in this study supports the relevance of extended feedback dialogues to enhance student learning (Gamlem & Smith, Citation2013; Steen-Utheim & Wittek, Citation2017). However, the results showed that analysis and inquiry, the dimension for higher-order questions, problem-solving and metacognition, was the dimension with lowest score in the instructional support domain, consistent with previous studies (e.g. Gamlem, Citation2019; Westergård et al., Citation2019). This points to difficulties in facilitating opportunities for self-regulation by attention to students’ internal feedback through classroom dialogues as conceptualised in responsive pedagogy (Smith et al., Citation2016). The low overall score for instructional support of the present study also indicates a struggle to facilitate clear learning goals, deep understanding of content, and feedback dialogues that expand on student learning. Teachers’ involvement in the facilitation of students’ goal setting might be critical for students’ self-regulated learning processes, in which students set goals and systematically carry out the actions needed to attain them (Andrade & Brookhart, Citation2016; Zimmerman, Citation2002).

There are indications of challenges concerning teachers’ regard for adolescent perspectives. As such, the teacher–student interactions seem to be of less relevance to students’ current lives and perspectives. This finding suggests that teachers might not sufficiently capitalise on students’ EFL competence, background and interests, in keeping with other EFL studies (e.g. Burner, Citation2015; Illman & Pietilä, Citation2018; Vattøy & Smith, Citation2019). The association between analysis and inquiry and regard for adolescent perspectives found in this study also relates to previous research that has connected teachers’ sensitivity to adolescent perspectives and facilitation of higher-order thinking skills to student achievement (Allen et al., Citation2013). Learning goal orientation and opportunities for self-regulation have further been identified as critical aspects for students’ self-efficacy and perceptions of teachers’ feedback practice in EFL teaching (Vattøy & Smith, Citation2019).

This study found that EFL teachers were to varying degrees role models for L2 use. Responsive pedagogy in EFL teaching consists of bolstering students’ self-confidence by using the L2 actively in feedback interactions. Whilst multilingualism and codeswitching have been identified as resources in foreign language teaching (e.g. Illman & Pietilä, Citation2018; Then & Ting, Citation2011), the results of the present study suggest that an overreliance on L1 might inhibit student learning, consistent with previous EFL studies (e.g. Burner, Citation2015). In EFL feedback interactions, the teacher’s L2 use might indicate the teacher’s belief in students’ capabilities to comprehend and respond in the L2. Use of L2 also signals students’ possibilities or lack of possibilities to practise the language central to the foreign language learning. However, this study indicates that some of the teachers struggle to facilitate the learning process in English and provide feedback in a way that positively affects students’ learning. Although some of the excerpts from the cases show feedback at the process and self-regulation level, the overall tendency in the descriptive statistics indicates low scores for feedback quality and opportunities for self-regulation. Nevertheless, teachers’ L2 use in feedback interactions as identified in this study appears to add to the relevance of a shared language of feedback between teachers and students (Jónsson, Smith, & Geirsdóttir, Citation2018).

The feedback quality of teacher–student interactions in the present study was often characterised by IRE interactions and feedback about tasks (Mehan, Citation1979). Nonetheless, the analyses of the cases show that traces of summative and formative assessment practices are carried out in both the L1 and L2. For example, the excerpt of Teacher A shows examples of a formative assessment practice in the L1, whilst Teacher D exemplifies some formative assessment practices in the L2. By contrast, Teachers B and C show that summative assessments are made in both the L1 and L2. These patterns seem to indicate some challenges for teachers in providing high-quality feedback that stimulates regulation of learning processes in the L2. Additionally, the feedback provided by the nine teachers (n = 65 lessons), is frequently provided to control that students are completing tasks. This accords with findings from Gamlem and Munthe (Citation2014) that feedback is often more encouraging and affirming, rather than promoting information about learning in lower-secondary classrooms (Gamlem & Munthe, Citation2014; Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007). In such situations, students do not receive feedback on how to strengthen their learning processes, nor the regulatory processes needed to achieve set learning goals. The dimension, quality of feedback, has also been scored in the low-mid range in previous studies (e.g. Gamlem, Citation2019; Virtanen et al., Citation2018; Westergård et al., Citation2019), which points to a greater tendency and challenge for quality in teacher-student interactions in lower-secondary schools.

The present study found that the teachers provide feedback mostly as ‘approving–controlling–disapproving’ (Gamlem & Smith, Citation2013), which makes students passive recipients rather than active participants. The challenge lies in supporting feedback as ‘constructing achievement–dialogic feedback interaction–constructing a way forward’ (Gamlem & Smith, Citation2013), which could support students’ self-regulatory capacities as well as building self-efficacy beliefs (Gamlem, Citation2019; Vattøy & Smith, Citation2019). Further, feedback to the self as a person with little task-related information was found in one of the cases of the present study. Such personal feedback is often ineffective and may even be counterproductive for student learning (Hattie & Timperley, Citation2007).

There is great variation in terms of the amount of L2 exposure for the students in the EFL classrooms of the current study, and L2 use seems to be a predictor for L1 use. In teaching EFL, one of the aims is to learn the language by using it, which makes exposure to L2 and opportunity for practice crucial. Although a shared L1 has been connected to a reduction of the cognitive load and anxiety levels among students (Bruen & Kelly, Citation2017), the teacher as a role model for L2 use in EFL teaching is important for communicating teacher expectations. Teacher expectations are powerful, and research emphasises that expectations influence students’ confidence and achievement (Rubie-Davies, Hattie, & Hamilton, Citation2006). Teachers with high expectations provide a framework for students’ learning, give more feedback and ask higher-order questions (Rubie-Davies, Citation2007).

In responsive pedagogy, dialogues are realised as instructional encounters between teachers and students where teachers follow up students recursively (Smith et al., Citation2016). Follow-up interaction patterns (IRF) foster students’ internal feedback dialogues and self-regulatory processes through multiple exchanges. Thus, self-regulation entails more than merely an inert mental ability, but a dynamic transformational process (Zimmerman, Citation2002). Responsive pedagogy is concerned with the capitalisation on unplanned pedagogical moments to utilise students’ internal feedback processes through external feedback dialogues in teacher–student interactions. However, this study indicates that several chances of utilising pedagogical moments are squandered.

Implications, limitations and future research

The language of feedback seems to be an important characteristic of teacher–student interactions in teaching EFL. Feedback practice in EFL classrooms, understood as responsive pedagogy, manifests itself through learning dialogues with an emphasis on student learning and L2 use. The results of the present study are comparable with research studies that have used the CLASS-S (e.g. Gamlem, Citation2019; Virtanen et al., Citation2018; Westergård et al., Citation2019), but extend the discussion of what characterises quality in foreign language teacher–student interactions with its added focus on the language of feedback in language teaching classes. The findings of the present study have implications for teacher education programmes. Teacher candidates might need training in developing their responsive pedagogy in foreign and second language contexts with focus on using the L2 and providing feedback to enhance students’ self-regulated learning. Teachers also need to revisit their practices both in terms of L2 use and feedback practices as these have implications for student learning in EFL classrooms.

The main implication of responsive pedagogy for the teacher is to tap into and capitalise on the learner’s internal dialogue with appropriate teaching approaches and external feedback (Smith et al., Citation2016). Focus on higher-order thinking and metacognition in teacher–student interactions seems to represent an aspect of struggle, as it was frequently neglected in the teacher–student interactions of the present study. The results also indicate that the quality of the dialogue and questions asked are important indicators to achieve a feedback practice that make students believe in their own foreign language abilities.

A few limitations in the study need to be addressed. The video-recorded material consisted of EFL lessons of various teaching situations, across different content, and teaching contexts. Teachers respond differently in terms of L1 and L2 use depending on context and situations (Then & Ting, Citation2011). A teacher who spends a lot of time tutoring students (e.g. low-achieving students) one to one will be prone to more L1 use than a teacher who teaches traditionally in a lecturing form. Such behaviours are consistent with the ones found by Burner (Citation2015) where teachers adapted their teaching by using the L1 to low-performing students, particularly at the start of lower-secondary school. Furthermore, dialogic schemes for studying classroom dialogue across educational contexts, such as the Scheme for Educational Dialogue Analysis (SEDA), have been developed (Hennessy et al., Citation2016). The choice of the CLASS-S as observation manual was made due to its explicit focus on students’ age, quality in teacher–student interactions, and relevant dimensions to understanding feedback to support the regulation of students’ learning processes.

The present study suggests that feedback practice in EFL lessons are characterised by both quality dimensions of teacher–student interactions as well as L2 use. However, more research is needed to map teachers’ L2 use in foreign language teaching as related to the specific teaching contexts, as well as how teachers can aid students’ self-regulatory processes through feedback dialogues in EFL teaching. Further research is also needed to understand teachers’ aims and beliefs about their own feedback practice and choice of language in foreign language teaching lessons, as well as how this could support students’ learning and wellbeing.

Acknowledgments

We are grateful to Professor Kari Smith (Norwegian University of Science and Technology) for valuable feedback and comments on drafts of this article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Adie, L., van der Kleij, F., & Cumming, J. (2018). The development and application of coding frameworks to explore dialogic feedback interactions and self-regulated learning. British Educational Research Journal, 44(4), 704–723.

- Allen, J., Gregory, A., Mikami, A., Lun, J., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2013). Observations of effective teacher-student interactions in secondary school classrooms: Predicting student achievement with the Classroom Assessment Scoring System–Secondary. School Psychology Review, 42(1), 76–98.

- Andrade, H., & Brookhart, S. M. (2016). The role of classroom assessment in supporting self-regulated learning. In L. Allal & D. Laveault (Eds.), Assessment for learning: Meeting the challenge of implementation (pp. 293–309). Heidelberg: Springer.

- Archer, K., Kerr, K. A., & Pianta, R. C. (2015). Why measure effective teaching? In T. J. Kane, K. A. Kerr, & R. C. Pianta (Eds.), Designing teacher evaluation systems: New guidance from the Measures of Effective Teaching Project (pp. 1–9). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Bandura, A. (1989). Human agency in social cognitive theory. American Psychologist, 44(9), 1175–1184.

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. New York, NY: Freeman.

- Bell, C. A., Dobbelaer, M. J., Klette, K., & Visscher, A. (2019). Qualities of classroom observation systems. School Effectiveness and School Improvement, 30(1), 3–29.

- Bell, C. A., Gitomer, D. H., McCaffrey, D. F., Hamre, B. K., Pianta, R. C., & Qi, Y. (2012). An argument approach to observation protocol validity. Educational Assessment, 17(2–3), 62–87.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (1998). Assessment and classroom learning. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 5(1), 7–74.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2009). Developing the theory of formative assessment. Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability, 21(1), 5–31.

- Black, P., & Wiliam, D. (2018). Classroom assessment and pedagogy. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 25(6), 551–575.

- Bruen, J., & Kelly, N. (2017). Using a shared L1 to reduce cognitive overload and anxiety levels in the L2 classroom. The Language Learning Journal, 45(3), 368–381.

- Burner, T. (2015). Formative assessment of writing in English as a foreign language. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 60(6), 626–648.

- Casabianca, J. M., Lockwood, J. R., & McCaffrey, D. F. (2015). Trends in classroom observation scores. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 75(2), 311–337.

- Casabianca, J. M., McCaffrey, D. F., Gitomer, D. H., Bell, C. A., Hamre, B. K., & Pianta, R. C. (2013). Effect of observation mode on measures of secondary mathematics teaching. Educational and Psychological Measurement, 73(5), 757–783.

- Culp, K. M., Martin, W., Clements, M., & Lewis Presser, A. (2015). Testing the impact of a pre-instructional digital game on middle-grade students’ understanding of photosynthesis. Technology, Knowledge and Learning, 20(1), 5–26.

- Curby, T. W., Johnson, P., Mashburn, A. J., & Carlis, L. (2016). Live versus video observations: Comparing the reliability and validity of two methods of assessing classroom quality. Journal of Psychoeducational Assessment, 34(8), 765–781.

- Ellis, R. (2012). Language teaching research and language pedagogy. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Ellis, R., Loewen, S., & Erlam, R. (2006). Implicit and explicit corrective feedback and the acquisition of L2 grammar. Studies in Second Language Acquisition, 28(02), 339–368.

- Gamlem, S. M. (2019). Mapping Teaching Through Interactions and pupils’ learning in mathematics. SAGE Open, 9(3), 2158244019861485.

- Gamlem, S. M., & Munthe, E. (2014). Mapping the quality of feedback to support students’ learning in lower secondary classrooms. Cambridge Journal of Education, 44(1), 75–92.

- Gamlem, S. M., & Smith, K. (2013). Student perceptions of classroom feedback. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 20(2), 150–169.

- Gan, Z., Liu, F., & Yang, C. C. R. (2017). Assessment for learning in the Chinese context: Prospective EFL teachers’ perceptions and their relations to learning approach. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 8(6), 1126–1134.

- Hafen, C. A., Hamre, B. K., Allen, J. P., Bell, C. A., Gitomer, D. H., & Pianta, R. C. (2015). Teaching Through Interactions in secondary school classrooms: Revisiting the factor structure and practical application of the Classroom Assessment Scoring System – Secondary. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 35(5–6), 651–680.

- Hardman, F., & Hardman, J. (2017). Systematic observation: Changes and continuities over time. In R. Maclean (Ed.), Life in schools and classrooms (pp. 123–137). Singapore: Springer.

- Hattie, J., & Timperley, H. (2007). The power of feedback. Review of Educational Research, 77(1), 81–112.

- Hennessy, S., Rojas-Drummond, S., Higham, R., Márquez, A. M., Maine, F., Ríos, R. M., … Barrera, M. J. (2016). Developing a coding scheme for analysing classroom dialogue across educational contexts. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 9, 16–44.

- Illman, V., & Pietilä, P. (2018). Multilingualism as a resource in the foreign language classroom. ELT Journal, 72(3), 237–248.

- Jónsson, Í. R., Smith, K., & Geirsdóttir, G. (2018). Shared language of feedback and assessment. Perception of teachers and students in three Icelandic secondary schools. Studies in Educational Evaluation, 56, 52–58.

- Lee, I., & Coniam, D. (2013). Introducing assessment for learning for EFL writing in an assessment of learning examination-driven system in Hong Kong. Journal of Second Language Writing, 22(1), 34–50.

- Li, S. (2010). The effectiveness of corrective feedback in SLA: A meta-analysis. Language Learning, 60(2), 309–365.

- Malmberg, L.-E., Hagger, H., Burn, K., Mutton, T., & Colls, H. (2010). Observed classroom quality during teacher education and two years of professional practice. Journal of Educational Psychology, 102(4), 916–932.

- Mehan, H. (1979). ‘What time is it, Denise?’: Asking known information questions in classroom discourse. Theory Into Practice, 18(4), 285–294.

- Panadero, E., Andrade, H., & Brookhart, S. (2018). Fusing self-regulated learning and formative assessment: A roadmap of where we are, how we got here, and where we are going. The Australian Educational Researcher, 45(1), 13–31.

- Pennings, H. J. M., van Tartwijk, J., Wubbels, T., Claessens, L. C. A., van der Want, A. C., & Brekelmans, M. (2014). Real-time teacher–Student interactions: A dynamic systems approach. Teaching and Teacher Education, 37, 183–193.

- Pianta, R. C., Hamre, B. K., & Mintz, S. (2012). Classroom Assessment Scoring System (CLASS): Secondary manual. Charlottesville, VA: Teachstone.

- Pianta, R. C., La Paro, K. M., & Hamre, B. K. (2008). The Classroom Assessment Scoring System: Pre-K manual. Baltimore, MD: Brookes.

- Ramaprasad, A. (1983). On the definition of feedback. Behavioral Science, 28(1), 4–13.

- Rubie-Davies, C. (2007). Classroom interactions: Exploring the practices of high- and low-expectation teachers. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 77(2), 289–306.

- Rubie-Davies, C., Hattie, J., & Hamilton, R. (2006). Expecting the best for students: Teacher expectations and academic outcomes. British Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(3), 429–444.

- Sadler, D. R. (1989). Formative assessment and the design of instructional systems. Instructional Science, 18(2), 119–144.

- Shute, V. J. (2008). Focus on formative feedback. Review of Educational Research, 78(1), 153–189.

- Sinclair, J. M., & Coulthard, R. M. (1975). Towards an analysis of discourse: The English used by teachers and pupils. London: Oxford University Press.

- Smith, K., Gamlem, S. M., Sandal, A. K., & Engelsen, K. S. (2016). Educating for the future: A conceptual framework of responsive pedagogy. Cogent Education, 3(1).

- Steen-Utheim, A., & Wittek, A. L. (2017). Dialogic feedback and potentialities for student learning. Learning, Culture and Social Interaction, 15, 18–30.

- Then, D. C.-O., & Ting, S.-H. (2011). Code-switching in English and science classrooms: More than translation. International Journal of Multilingualism, 8(4), 299–323.

- Vattøy, K.-D., & Smith, K. (2019). Students’ perceptions of teachers’ feedback practice in teaching English as a foreign language. Teaching and Teacher Education, 85, 260–268.

- Virtanen, T. E., Pakarinen, E., Lerkkanen, M.-K., Poikkeus, A.-M., Siekkinen, M., & Nurmi, J.-E. (2018). A validation study of Classroom Assessment Scoring System–Secondary in the Finnish school context. The Journal of Early Adolescence, 38(6), 849–880.

- Westergård, E., Ertesvåg, S. K., & Rafaelsen, F. (2019). A preliminary validity of the Classroom Assessment Scoring System in Norwegian lower-secondary schools. Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research, 63(4), 566–584.

- Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory Into Practice, 41(2), 64–70.