?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Often considered dumping grounds for those who cannot function in mainstream schools, alternative education providers are seen as outliers in the provision of schooling. With schools as relatively stable workplaces, alternative education provision makes for a rich laboratory to further our understanding of the causal impact of schooling on a range of outcomes. They are naturally occurring experiments in schooling through interventions in instruction, curriculum and student cohort. Montessori school-based education in Australia is one such case. Experiencing a 31% growth in enrolments since 2009, they offer useful insights for different measures of education. A pre-requisite to such insights is a situational analysis of current provision. Drawing on an interview-based study with 20 Montessori school leaders, this investigation identified three problems and possibilities for schools working on the margins: i) clarity about what is their distinctive form of education; ii) building the collective; and iii) evidencing quality of provision.

Introduction

Australia has one of the most inequitable provisions of schooling in the OECD (Chzhen et al., Citation2018; Varadharajan et al., Citation2022). Creating a more equitable and inclusive provision of schooling at scale has been an enduring issue for governments and systems. The stakes are high. Considerable public investment is dedicated to education. In the 2019–2020 financial year, government recurrent expenditure on school education was $70.6B,Footnote1 the largest in the country’s history. At the same time, a downward or at best stable trend in student scores in national (e.g. NAPLAN) and international (e.g. PISA, TIMSS) assessments has caused concern among policymakers, systems, communities and the media. Throughout Australia, as globally, questions of where to invest (Busemeyer et al., Citation2018), what to measure (Ladwig, Citation2010) and re-imagining what education can be (UNESCO, Citation2021), has led to diversity in school offerings. In many cases, there is hope that alternative models of schooling and potential innovations can be incubated and then replicated to help create system-wide conditions allowing for improved outcomes to emerge (Hatch et al., Citation2021).

In the last two decades Australia has been one of the most enthusiastic embracers of school choice, making it an ideal site for studying alternative provision. Based on 2020 national profiles, 30% of schools (n = 2867) are non-public schools and they educate 34% (n = 1,377,831) of students. Additionally, in 2011 the Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority (ACARA) assessed three curriculum frameworks as equivalent to the National Curriculum: the Montessori National Curriculum Framework; the Australian Steiner Curriculum Framework; and the International Baccalaureate Primary Years Program (PYP) and Middle Years Program (MYP). Of those three, Montessori and Steiner have schools established with the specific purpose of delivering on that curriculum. In doing so, they are more coherent than many larger (e.g. public or Catholic) systems (D. K. Cohen et al., Citation2018), granting them greater ecological validity. Therefore, while Montessori and Steiner schools have been of minimal significance to those interested in school reform (Whitescarver & Cossentino, Citation2008), they hold great potential for researchers and policymakers.

Montessori (as with Steiner) schools in Australia make a rich laboratory to further our understanding of the causal impact of variation within a system and its impact on outcomes. They offer a distinctive culture with a well-developed instructional approach, professional associations and discrete preparation programmes guaranteeing a degree of quality control rare in alternative provision (D. K. Cohen et al., Citation2018). However, a pre-requisite to testing variance of impact is a situational analysis of current provision and the state of Montessori schools as a collective throughout Australia. Drawing on an interview-based study with 20 school leaders, this initial investigation identifies three problems and possibilities for schools working on the margins of provision: i) clarity about what constitutes their distinctive form of education; ii) building the collective; and iii) evidencing the quality of provision.

Background and context

News of Maria Montessori’s work at Casa dei Bambini (Children’s House) in Rome, Italy reached Sydney, Australia in the early 1900s. Peter Board (Director of Education), A.C. Carmichael (Minister for Education) and Alexander Mackie (Founder of the first teachers’ college in New South Wales) saw potential application in the New South Wales context and wanted to know more. To further investigate, they dispatched Martha Simpson to study with Maria Montessori at her first international training in 1912 (O’Donnell, Citation1996). Upon her return, in 1915, Simpson founded Blackfriars Practising School – one of the first schools in the world to adopt the Montessori approach (Powell, Citation2022).

The Montessori method is a nonconventional teaching method based on Maria Montessori’s four planes of development: birth to six years, the ‘absorbent mind’; six to 12 years, the ‘reasoning mind’; 12–18 years, the ‘humanistic mind’; and 18–24 years, the ‘specialist mind’. Classrooms, or ‘the prepared environment’, are characterised by mixed-aged groups (matching the developmental planes), allowing students their personal choice of activities, respecting freedom and teaching responsibility, facilitating the manipulation and understanding of materials, the uninterrupted work block, and a less observable role of the teacher (D. L. Cohen, Citation1989; Debs et al., Citation2022; Gasco-Txabarri & Zuazagoitia, Citation2022). Montessori is credited with the development of open classrooms, individualised education, manipulative learning materials and programmed instruction. Her approach balances a strict adherence to curriculum and order in the classroom while recognising and valuing the individual child and their development, making it attractive to progressives and often critiqued by traditionalists.

The early parts of the twentieth century saw the establishment of many Montessori classrooms by middle-class philanthropists and social reformers throughout New South Wales and across Australia. A number of these supporters were already involved in the free kindergarten and infant school movements of the time. The purpose, or vision, of these early reformers was to ‘provide disadvantaged children with an environment in which they could thrive physically and intellectually in an atmosphere of freedom’ (Feez, Citation2013, p. 182). There was an embedded reform agenda built on equity and inclusion, catering for those on the margins. This period was, however, short lived. Following the Great Depression and the Second World War, there was less funding available for progressive education or alternative provision (Kass, Citation2021). As a result, there was a decline in interest and opportunities for Montessori education in Australia.

Globally, there was a re-emergence (mindful that it never fully went away) of Montessori education in the 1970s and 1980s propelled by calls for greater child-centred approaches (D. L. Cohen, Citation1989; Debs, Citation2019). This was particularly so in the United States, where Montessori’s approach was a common theme in the magnet programme and subsequently became a significant presence in provision of public and private schooling; it is now the most common alternative pedagogy in public schools (Debs & Brown, Citation2017). While not to the same scale as the United States, Australia too experienced a resurgence of Montessori education in the 1980s onwards.

Analysis of ACARA school profile dataFootnote2 shows that in 2020 there were 37 schools across 46 sites (multi-campus schools are common) identifying as Montessori. Cross checking with membership of the two national bodies, Montessori Australia (MA) and Montessori Schools and Centres Australia (MSCA), identifies a further nine (at least) government or independent schools with Montessori streams or classes. The 37 schools employ 482 teachers and 479 non-teaching staff. To place this scale in the context of Australian education, Montessori schools only constitute 0.48% of schools (3.93% of all independent schools), educate 0.10% of students and employ 0.16% of staff (0.60% students and 0.81% of staff in independent schools) within Australian school-based education. This keeps Montessori schools – both individually and as a collective – on the margins.

However, trend data reflects a positive engagement from stakeholders. When compared with 2009 profiles, enrolment in Montessori schools is up 31.0% (2953 to 3867), well above the national growth (15%) and government (14.6%), Catholic (10.5%) and independent (23.5%) sectors over the same period. As a direct comparator, Steiner schools are up 23.8% (7560 to 9358) between 2009 and 2020. The actual growth for Montessori, as with Steiner, is hidden in the streams of government and other independent schools which are impossible to parse in publicly available data sets. What we are seeing is an increasing market share for alternative education – but where this share comes from is a point of contention – especially given the equity and inclusion agenda embedded in the genesis of Montessori schools in Australia.

Montessori schools are primarily clustered in capital cities (e.g. Sydney). Using the Australian Statistical Geographic Standard (ASGS) categories, 91% (n = 42) of the schools are in major cities, 7% (n = 3) inner regional and 2% (n = 1) in outer regional. There are no Montessori schools in remote or very remote locations. This contrasts with other alternative education providers such as Steiner schools which are more common outside of major cities. Recent analysis has shown that 43% of Steiner schools are in major cities (n = 20), with 34% (n = 16) inner regional, 21% (n = 10) outer regional and 2% (n = 1) in a remote location (Eacott & Munoz Rivera, Citation2021). More than just geography, it is whom these schools serve that is important for equitable and inclusive education. ACARA school profiles show that across Montessori schools an average of 1.0% of students identify as Indigenous (n = 37, ̅ = 1.0, σ = 1.6, min = 0, max = 5, ̃ = 0) and 26.6% have a Language Background Other Than English (LBOTE, n = 35, ̅ = 26.6, σ = 20.0, min = 0, max = 91, ̃ = 24). Nationally, the average percentage of students identifying as Indigenous is 10.3% (n = 7994, σ = 17.7, min = 0, max = 100, ̃ = 4) and LBOTE is 23.2% (n = 8720, σ = 25.9, min = 0, max = 100, ̃ = 12). Montessori schools are less likely to have students who identify as Indigenous and close to the average for students with a LBOTE when compared with the average Australian school.

There is research literature indicating that Montessori schools are more exclusive than accessible (Burbank et al., Citation2020; Debs & Brown, Citation2017), with a key indicator being the location of the school in an advantaged area (Burbank et al., Citation2020). To test this idea in the Australian context we drew on the Index of Community Socio-Economic Advantage (ICSEA) developed by ACARA. The ICSEA is designed to allow for meaningful comparison between school students’ performance in national assessment exercises (e.g. National Assessment Program – Literacy and Numeracy [NAPLAN]).Footnote3 ICSEA values typically range from approximately 500 (representing schools with extreme disadvantaged student backgrounds) to about 1300 (representing schools with extreme advantaged student backgrounds). It is calculated for all schools with sufficient aggregate-level data (e.g. excluding special schools, juvenile justice centres).

displays the data for aggregate ICSEA distribution across sectors (government, Catholic, independent) and nationally in comparison with Montessori schools. Based on 2020 data, the national mean ICSEA is 1002 (N = 9378, μ = 1002, σ = 97, min = 100, max = 1278,

= 1007), with independent (n = 1072,

= 1059, σ = 99, min = 160, max = 1278,

= 1069) and Catholic (n = 1699,

= 1042, σ = 79, min = 100, max = 1203,

= 1,044) schools above that and government (n = 6607,

= 983, σ = 94, min = 100, max = 1240,

= 983) schools below. With the smaller sample size (n = 35), Montessori schools are more tightly clustered (σ = 46, min = 1060, max = 1202). The mean (

= 1120) is above national, independent, Catholic and government schools. This would confirm the perception that Montessori schools are not necessarily accessible to all and are instead a school for the advantaged.

Table 1. ICSEA distribution by school sector compared to Montessori.

The impact of Montessori education has been a point of contention. There is a growing evidence base demonstrating alignment with contemporary neuroscience and the science of learning (Denervaud et al., Citation2019; L’ecuyer et al., Citation2020). Research has also shown the positive effect of Montessori education for refugees (Tobin et al., Citation2015), for Indigenous (First Nations’) children (Holmes, Citation2018), in special education (AuCoin & Berger, Citation2021), in participation in interdisciplinary science, technology, engineering and mathematics (STEM) (Livstrom et al., Citation2019), and on students’ social behaviours (Dereli İ̇man et al., Citation2019).

At the same time, there have been inconsistent results in comparative studies testing whether Montessori is more effective than other approaches (e.g. Lopata et al., Citation2005; Peng & Md-Yunus, Citation2014), as well as discrepancies in the effect across different curriculum areas or equity groups (Ansari & Winsler, Citation2014). There is evidence that while inconsistent across all areas, the positive effect of Montessori (up to one third of a standard deviation) is sustained over time and even when a student transitions into traditional school settings (Dohrmann et al., Citation2007), a particularly relevant finding for the Australian context where few Montessori schools extend into secondary (and especially upper secondary) school.

Montessori education relies more on teacher observation and portfolio-type evidence than traditional test-based approaches to student assessment. This makes large-scale testing a philosophical challenge, with some parents opting their children out of national testing. However, NAPLAN data does provide some insights for assessing the performance of Montessori schools, individually and as a collective (see Eacott et al., Citation2022). Focusing specifically on Year 3 (the first NAPLAN test, followed by Years 5, 7 and 9), in the period 2014–2019, only 24–28 Montessori schools participated at sufficient scale to have publicly available data. Individual school level participation rates averaged 90% (n = 28, = 90, σ = 9, min = 68, max = 100,

= 93), below the national average of 95%. Using weighted means at the school level across all five sub-tests (reading, writing, spelling, grammar and punctuation, and numeracy), Montessori schools score 0.27σ higher than the national average. The same analysis of Year 5, where between 21–27 Montessori schools participated in the period 2014–2019, student scores were 0.28σ higher than national averages. Smaller samples in Year 7 (n = 8–10) and Year 9 (n = 5–8) limit claims, but the difference reduces to 0.14σ and 0.09σ. While not definitive data, there is not exponential growth between Year 3 and Year 5 (and beyond), and the gap that does exist can be explained away as a function of socio-economic advantage. This creates a problem for Montessori education in Australia distinct from elsewhere.

Throughout Australia, 52% (n = 24) of Montessori schools are primary (elementary) schools, 46% (n = 21) are combined primary and secondary, and there is a single standalone secondary school. Significantly, even when secondary schooling is available, very few schools go all the way through to Year 12 (the final year of secondary schooling). In the period 2014–2019, only 83 students completed senior secondary school at Montessori sites. With limited NAPLAN and senior secondary data, it is difficult to make definitive statements on the effectiveness of Montessori schools.

Despite a lengthy history and a global scale of provision, there is scarce research on Montessori education (Lillard, Citation2012; Ruijs, Citation2017). This is not to say there is no research. Rather, as Marshall (Citation2017) points out, there are few longitudinal designs, an absence of randomised control trials, issues of attribution to Montessori approaches as causes of change, treatment fidelity and time of treatment matters, and the scale of most research (e.g. a single school or classroom – often with narrow demographics) make it difficult to generalise or offer robust evidence of effect (see also Culclasure et al., Citation2019).

Analytical approach

This paper draws from a larger research programme entitled Building Alternative Indicators for Schooling being conducted in partnership with Steiner Education Australia (SEA), Montessori Australia (MA) and Montessori Schools and Centres Australia (MSCA). It builds on reports capturing snapshots of provision for Steiner (Eacott & Munoz Rivera, Citation2021) and Montessori (Eacott et al., Citation2022) schools. Specifically, this paper draws on an interview-based study with Montessori school leaders (n = 20). Rather than within school issues, the foci of this paper are the contemporary problems and possibilities of school provision on the margins, with particular attention to the experiences of Montessori school leaders.

Following University ethics approval, a participant information statement and consent form were distributed to the member schools of MA and MSCA inviting school leaders (as the title ‘principal’ is not necessarily shared by all schools) to contribute to the study. A total of 20 school leaders accepted the invitation to contribute. All interviews (due to pandemic restrictions) were conducted using Microsoft Teams (recorded in MSTeams and with a back-up digital recording of audio) and all conducted by the lead investigator. Interviews ranged from 45 to 67 minutes in length.

The 20 interviews generated a 171,294-word corpus. Theoretically informed by Eacott’s (Citation2018) relational approach, an inductive analytical approach was undertaken centring on three key questions: i) what is Montessori education; ii) how does that play out in practice; and iii) what are the problems and possibilities for Montessori school-based education in Australia. Through an initial round of analysis, the 171,294 words were reduced to 78 unique codes. These 78 codes clustered into 9 areas best captured in 3 themes. Expressed differently, this inductive data reduction process can be represented as:

171,294 words → 78 codes → 9 clusters → 3 themes

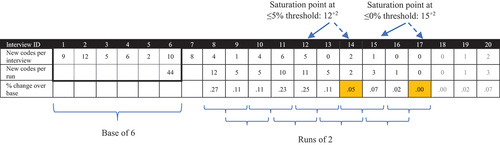

Justifying the sample size of interview-based studies, and qualitative studies in general, has been a contentious issue in many disciplines (Hennink et al., Citation2017; Malterud et al., Citation2016; Vasileiou et al., Citation2018). A priori decisions using power analysis are difficult; instead, post hoc analysis using data saturation is often the conceptual benchmark for assessing sampling adequacy. Drawing on a technique developed by Guest et al. (Citation2020) built on base size, run length and new information threshold, we justify the adequacy of our sample through this method and not simply declaration.

Existing research indicates that novel information is secured in a relatively small number of interviews with a rapid decline in new information thereafter. Assessing data saturation requires weighing incoming new information against a base of initial information obtained. The decision concerns how many interviews should be used to constitute this base size – the denominator for the saturation ratio calculation. Run length is the number of interviews within which we are looking for new information. The number of new codes identified within a run length is used to define the numerator in the saturation ratio. New information threshold is the level of new information we should accept as indicative of saturation.

Building from suggestions from Guest et al. (Citation2020), in our analysis we ran multiple base sizes (4, 5 and 6) and run lengths (2 and 3). Appropriating benchmarks for assessing p-values (<0.05 and<0.01) informed our decisions regarding the new information threshold. displays our chosen model that optimises our data for maximum insight. Given the heterogeneity of the schools (within the parameters of the single Montessori identifier), to allow for maximum variation we decided on a base size of 6, a run length of 2 and report both<0.05 and<0.01 as new information thresholds. Taken together these are within Guest and colleagues’ suggestions (4–6 base size, 2–3 run length, and<0.05 or<0.01 new information threshold). There is no guarantee that data saturation has been met through these thresholds (Guest et al., Citation2020). However, it does provide transparency in our decisions that can be interpreted by other researchers, and we claim sufficient support to justify our claims.

To validate our claim to sample adequacy, we then conducted a bootstrap analysis of the sample. We ran 100 re-samples, randomly ordering the selected transcripts in each re-sample to offset any order effect on how and when unique codes were discovered. Using the same assumptions as the previous analysis (base of 6, run length of 2, and reporting both<0.05 and<0.01) and reporting the 5th and 95th percentile provides a non-parametric 90% confidence interval for the number of transcripts required to reach saturation. The results were a median of 18 (16+2) interviews (above the previously identified 14), with confidence intervals of 8 and 20. Since we had the available number of unique codes in each dataset, we could calculate the degree of saturation (percentage of unique codes). At the median (18), we had 86%, with confidence intervals of 40 (5th percentile) and 98 (95th percentile) per cent. It is possible that the inflated bootstrap results are the outcome of ordering indicating unique codes identified, and changing the order meant repeated codes were not necessarily accurately captured. That said, taken together, we believe the results of the initial and subsequent analysis validates our sample of 20 as adequate for the claims being made.

Results

The coded data was reduced to three substantive themes: what is Montessori education; building the collective; and the quality of schooling. These are outlined below.

What is Montessori education?

Despite more than 100 years of history, Montessori education is not as well known in Australia as it is in Europe and the United States (Participants 01, 02, 04, 06 and 20). As Participant 07 noted, ‘people just do not know about us’. Not only is it less known, but there is considerable misunderstanding of what is, and just as importantly, is not, a Montessori education (Participants 05 and 14). The emergence of public and independent schools with ‘Montessori streams’ or identifying as Montessori schools (Participants 02 and 05) and the proliferation of early childhood centres using Montessori in their name or promotional materials (Participants 03, 06, 07 and 18) is further complicating the issue. But as one participant noted:

One of the key problems Montessori education has always had is that people find it difficult to articulate what it is in a very short snapshot. The elevator pitch is often 20 minutes. (Participant 08)

Contributing to this situation is the perception of Montessori as alternative. Many, if not all, contemporary Montessori schools in Australia were established by a group of passionate parents who wanted a different type of education for their children (Participant 06). This has led to persistent myths such as the schools being ‘the hippies on the hill (or down the valley)’ or that they cater for society’s misfits (Participants 06, 10, 12, 16 and 17). It was, however, pointed out by participants that in many ways a Montessori education was now unaffordable to the stereotypical hippies (Participant 08) and was now more boutique (Participant 19), having shifted ‘from boho to yuppie cool’ (Participant 18). This is, as Participant 06 noted, a very different perception to elsewhere (e.g. Europe and the United States) where Montessori is held in the highest regard and a much sought-after education.

Montessori education is for every child, but not necessarily every parent

Participant 07

Montessori education follows the child (Participant 12). This creates an element of risk for families (Participants 06 and 11) and caution from regulators and government (Participant 06). Amplified by a lack of exit examination data enabling explicit demonstration of achievement (albeit partial), there remains caution as to the effect of Montessori education on student outcomes (Participants 12 and 14). Parents or caregivers, in choosing a Montessori school are required to balance their desire for an alternative to mainstream schooling against the potential disadvantage their child may receive through that alternative (Participants 09 and 11). This is especially the case with so few Montessori schools extending into secondary (and particularly senior secondary), meaning many students need to at some point transition to other schools (Participants 04, 06, 11, 13 and 17). That said, the Montessori curriculum, which is equivalent to the national curriculum and not a ‘free for all’ (Participants 11 and 13), arguably has greater structure than mainstream schooling (Participant 06), and fidelity to the Montessori method means schools do not jump on the latest fads and fashions (Participants 04, 05 and 06).

Participants 19 and 20 point out that growth in enrolments is indicative of a desire for Montessori education within the community. Who gets to decide what is (and is not) Montessori education, speaks on behalf of, and monitors the fidelity and integrity of implementation remains contested (Participants 02 and 14). Therefore, while quality assurance is considered fundamental to advancing Montessori education in Australia, establishing and sustaining a process for it has proven elusive (Participants 07, 08 and 14). Failing to do so has allowed for the label of Montessori to be at best diluted and at worst compromised within the Australian context.

Building the collective

Governments and regulatory authorities such as the New South Wales Education Standards Authority (NESA) do not necessarily understand alternative education provision. Without a single national representative body to advocate and lobby for Montessori education as a collective, it remains on the margins (Participants 06 and 16). Furthermore, perceptions of negativity and in-fighting between the two national bodies (MA and MSCA) have been ‘quite debilitating’ and unhelpful in promoting and advancing Montessori education in Australia (Participants 02 and 18).

Greater than 50% of participants explicitly saw the two bodies as problematic (Participants 02, 03, 04, 06, 08, 10, 13, 14, 17, 18 and 19), with three explicitly seeking to ‘stay out of it’ (Participants 02, 13 and 14). Participant 18 suggested that ‘most schools are fence sitting, as no one wants to put their feet solely in one camp because who knows how this will play out’. Confusion and frustration at the lack of clear demarcation of roles and responsibilities across the two bodies (Participants 06, 10, 14, 17, 18 and 19) means no single body is speaking for the collective.

Advocacy of and for Montessori education is particularly timely in the Australian context. This needs to be more than a marketing campaign (Participant 10), as Montessori schools are up against large and well organised Catholic and independent schools in addition to public schools (Participant 16). However, advocacy efforts need robust evidence, otherwise they rely on emotional pleas. To this point, there is no systematic approach to generating high-quality aggregate data from the collective or independent research on the impact of Montessori school-based education on students, educators and communities (Participants 06 and 16). A greater quantity of high-quality rigorous and robust data and evidence on the impact of Montessori education will make it easier for more people (especially parents, but also regulators) to feel comfortable with Montessori schools (Participant 20).

The lack of a collective identity, voice and activities has implications for educators in schools. Many schools within the Montessori community feel isolated (Participants 05, 06, 13 and 16). Without systemic oversight, and many schools being small operations (2020 enrolment, n = 37, x = 104, σ = 76, min = 5, max = 284, x = 94), the expansion of administrative requirements demanded by contemporary legislation, regulation and accreditation takes a toll on school staff (Participant 11). The potential for reducing duplication and inefficiencies while building capacity and collective voice is currently going unmet. This does create an internal tension for Montessori education. If schools and educators look inward (to themselves or other Montessori schools) they run the risk of re-affirming what they are already doing (Participant 12), but by looking outside there is an issue of appropriateness for Montessori education (Participants 03 and 16). Either way, there is a desire for greater cross pollination of information, ideas and research within and across schools (Participants 05, 07, 13 and 15).

Evidencing the quality of provision

The lack of a collective entity representing Montessori schools means there is no single repository of data and the translation of that data into evidence to promote Montessori education (Participant 04). Paradoxically, the potential of data is not necessarily shared among the Montessori community (Participants 01, 03, 06, 12, 14 and 16). However, as a trained scientist, Maria Montessori was very data driven, primarily through observation (Participant 01). Without recognising it, the quantity and quality of data generated in Montessori primary schools is above and beyond that of many other schools (Participant 12). This is evidenced in the increasing uptake of commercial data products such as Transparent Classroom (Participants 05, 06, 14 and 20) for record keeping. In short, there is substantial data being generated and analysed in contemporary Montessori schools (Participants 03, 06, 08 and 17); it is just not systematised or used for systemic advocacy and decision-making – representing a significant opportunity lost.

Participant 01 noted: ‘A lot of research has been done in the way children learn, and it seems to align with what Montessori has been saying for the last 150 years.’ Montessori principles are consistent with recommendations from the Gonski Report Citation2018) and OECD (Citation2020) and UNESCO (Citation2021) reports calling for twenty-first-century skills, as well as personalised learning approaches where children and youth move through curriculum at their own pace (Participants 02, 03, 05, 06 and 11). The Montessori method, with its three-year cycles, gives staff the time to get to know students (Participants 01, 12 and 14), optimising the facilitation of children to be disciplined and hard working in their learning (Participants 08 and 17). This places a responsibility on staff for ensuring learning is taking place (Participants 02, 08, 14 and 19), but focused on the pace of the child not the teacher (Participant 07). This requires a well prepared, confident and grounded Montessori educator.

Employing Montessori trained educators can be difficult (Participants 08 and 10). To secure full qualification in the Australian context requires a four-year bachelor’s degree plus Montessori training, a duration comparable to medicine (Participant 07). This creates issues of accessibility (Participants 04, 13 and 18), financial and time burdens (Participants 03, 04, 07 and 13), questions regarding the inconsistent quality of provision (Participant 18), snobbery of providers (Participants 01, 04, 08 and 10), and the poaching of staff from other Montessori schools – weakening the collective (Participants 02 and 13). The practice of some schools that require new staff (university qualified but not Montessori trained) to take on assistant roles while completing further training further limits the pool of candidates (Participants 04, 05, 07 and 19). However, any appointment of the ‘Montessori aligned’ rather than necessarily formally trained (which may be for the purpose of having sufficient staff), needs to be balanced against parental pressure to have trained educators in schools and maintaining the integrity of Montessori provision (Participant 20).

Montessori education provides the opportunity for children to ‘really jump ahead and promote their own area of interest’ (Participant 12). The small size of schools is attractive to parents (Participant 16), with no child getting lost in a Montessori school (Participant 01). This is reflected in participants reporting positive outcomes for Indigenous (Participant 07), gifted and talented (Participant 12), and students requiring additional support (Participant 16). However, with small scale comes less resources. Identifying the ideal size that balances the financial realities of growth or survival without compromising the integrity of Montessori education is an enduring challenge (Participants 02 and 03). For several schools, this has meant being split across multiple sites, which brings other challenges of identity and collaboration among staff, students and the community (Participants 02, 11 and 17). To this point, generating robust evidence – not just anecdotal – at the school or the collective level to demonstrate the quality of provision in Montessori education has been unmet.

Discussion

There is no trademark on the label ‘Montessori’ (Whitescarver & Cossentino, Citation2008). This has potentially been exploited by schools and centres the world over to increase market share, and Australia is no exception. The label ‘Montessori’ has become a commodity used by providers to add credibility and attract families without any quality assurance processes or overarching body ensuring fidelity. It has come at the cost of diluting what it means to be a Montessori school, arguably pushing an already marginalised approach – constituting only 0.48% of all Australian schools – further to the margins. Multiple national bodies, which occurs in other countries such as the United States (Edwards, Citation2006), might further cloud the situation, but it is neither the cause or sustainment of the commodification.

Outside of early childhood (birth to eight) degrees, Montessori is rarely mentioned in initial teacher education programmes (Gill, Citation2007). Regulators, through reforms such as professional standards and accreditation, have removed marginalised approaches in favour of standardised expectations and the reduction of variation in programmes. The result is that even among the education community Montessori, as with other peripheral providers (e.g. Steiner), is not necessarily well known.

Internal tensions and contradictions are amplified for schooling on the margins. Montessori education remains filled with contradictions. It encourages independence yet is heavily structured, has a progressive agenda yet has changed little since its genesis (although there is evidence of a changing relationship with technology [Owen & Davies, Citation2020]), and has an equity and inclusion orientation but is somewhat exclusive (Cossentino, Citation2009) to name a few. Existing evidence shows that Australian Montessori schools, as with those elsewhere (Burbank et al., Citation2020), draw from socio-educationally advantaged families. The 2020 ACARA data has the average ICSEA for Montessori schools at 1120 (1.20σ above the national mean of 1002) and 83.0% of students coming from the top two socio-educational advantage quartiles (54.1% from the top quartile). Positive student outcomes data (Denervaud et al., Citation2019; Dereli İ̇man et al., Citation2019; Livstrom et al., Citation2019; L’ecuyer et al., Citation2020; Tobin et al., Citation2015) and particularly for equity groups (Holmes, Citation2018), cannot necessarily be attributed to a Montessori education due to confounding variables (e.g. SES). NAPLAN results in Year 3 and Year 5 (0.27–0.28σ average national means) are a promising sign, but the diminishing returns in existing Year 7 and 9 NAPLAN data and the absence of exit examination outcomes makes it difficult to definitively claim the impact of Montessori education beyond a function of socio-economic advantage.

What the above highlights is a fundamental issue for Montessori, and any alternative education provider, particularly in Australia where non-government schools receive considerable public funding. In claiming to offer something different, there is a requirement to demonstrate delivering on such claims. While this argument may be at odds with the normative position of those claiming the immeasurability of the outcomes of schooling, Montessori schools in Australia receive significant public monies. Based on 2019 financial year figures, approximately 50% of the AU$72 million of income for Montessori schools came from taxpayer funds. In the interests of public accountability, if a provider takes public money and claims to deliver an alternative education, there is an obligation to empirically defend those outcomes. This need not be in standard measures (e.g. test scores), but if you can claim an alternative normative goal of schooling or desired student outcome, that can be translated into instructional programmes, implemented and then evaluated for success against the desired outcomes. In doing so, there would be a more honest opening up of collective endeavours to sincere examination (Ladwig, Citation2010) for those within and beyond Montessori education.

The foundations of such a task already exist. While there is no trademark on Montessori, there is an articulation of the instructional approach and its broad agenda. In the specific Australian context, there is a Montessori curriculum framework assessed as the equivalent of the national curriculum, and we know that students are achieving above the national mean in standardised tests. Montessori schools represent a natural experiment in the provision of education. What remains missing is an articulation of what the distinct outcomes of attending a Montessori school are (as opposed to other forms of schooling) and how they translate into life beyond schooling (see also: Pugh & Bergin, Citation2005). In the absence of such evidence, the alternative nature of the schools is limited to mere declaration and uncritical acceptance. This does little to advance the agenda of those working on the margins and, if anything, pushes them further to the periphery.

Beyond simply evidencing their delivery of espoused outcomes, Montessori education (as with every alternative provider) needs to be located within contemporary schooling. There is a need for an explicit articulation of what is distinctive about the approach, how the outcomes compare to alternatives, and why such an approach is needed now (and into the future). For an approach that is anchored in the teachings of an Italian scientist of the early twentieth century, this can be a challenge. The genesis of the Montessori approach was a perceived social need for a different form of education. Traces of the social need for more equitable and inclusive education built on fostering the inner curiosity of the learner are evident in contemporary calls for soft skills and twenty-first-century learning. Demonstrating the contribution of Montessori education to this contemporary agenda is fundamental to survival in the competitive marketplace of school choice within Australian school-based education. Disparate individual schools, even with the single identifier (Montessori), cannot provide the level of evidence required to make a difference at scale. However, it is the alignment with a specific philosophical and instructional approach, supported by a curriculum framework and educator preparation programmes, that creates the opportunity for Montessori education to articulate, implement and evidence alternative indicators for the impact of schooling.

Limitations

The current study should be interpreted within the constraints of several limitations. First, despite the use of official government data on school profiles, the primary data source was self-reporting interviews with school leaders. Although this is an appropriate means for generating data on what it is like to work at the margins, it will be important to conduct further research from a greater breadth of data sources (e.g. educators, students, community members and professional associations). This is especially important if the goal is to generate a suite of alternative indicators for Montessori schooling that could be in natural experiments to develop empirically defensible claims on the impact of the approach on student outcomes. A practical, or knowledge translation, strength of the present work is that it provides Montessori educators and the broader Montessori community with a basis from which to build a collective and distinctive context-sensitive narrative of their impact.

Conclusion

Montessori education, as with all alternative provision, calls into question the orthodox measures of schooling and success within it. However, two fatal vulnerabilities of school reform are vagueness of outcomes and a neglect of wider political will to hold schools or systems to account. While international statements such as Sustainable Development Goal 4, or national statements such as the Alice Springs (Mparntwe) Declaration of Education Goals for Australians, call for new benchmarks and measures of school success, existing data infrastructure has not kept pace with changes in the contemporary world. Put simply, there is a pressing need for new measures of educational (academic) and social (non-academic) impacts of schooling. Alternative provision provides the possibility for delivering on this agenda, as it critically questions the existing grammar of schooling while simultaneously makes empirical claims around doing something different.

Any shift in the virtue of academic outcomes and the public’s reliance on them will not alter until we know more about non-academic outcomes (Ladwig, Citation2010). If, and it remains an if, Montessori schools (or any alternative provider) could demonstrate the delivery of alternative outcomes without compromising existing outcomes (e.g. reading, writing, numeracy), while also demonstrating stakeholder buy-in and the possibility of scaling, there is great potential in delivering school reform. Our analysis has shown that Montessori education has an articulated (even if vague) philosophical and instructional basis, a recognised curriculum framework, specifically trained educators, and student performance above national averages in standardised tests. Enrolment growth represents stakeholder buy-in, and a trajectory reflective of a shared need for what the Montessori approach offers. The increasing number of schools within Australia, not to mention on a global level, indicates the potential to scale. Put simply, the pieces are aligned. Herein lay the problems and possibilities of alternative school provision. Ladwig (Citation2010), following others, reminds us that in opening more aspects of schooling to measurement we expose more of childrens’ and youth’s lives to surveillance and oversight. For many, this is an undesirable outcome. At the same time, Montessori, as with other alternative providers, stake their claims on being distinctive from orthodox approaches to schooling. At the very least, they should be able to evidence their claims and, in doing so, perpetuate the possibility that schooling can be different to what it is at any distinct point in time.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

References

- Ansari, A., & Winsler, A. (2014). Montessori public school pre-K programs and the school readiness of low-income black and latino children. Journal of Educational Psychology, 106(4), 1066–1079. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0036799

- AuCoin, D., & Berger, B. (2021). An expansion of practice: Special education and Montessori public school. International Journal of Inclusive Education, 1–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2021.1931717

- Burbank, M. D., Goldsmith, M. M., Spikner, J., & Park, K. (2020). Montessori education and a neighborhood school: A case study of two early childhood education classrooms. Journal of Montessori Research, 6(1), 1–18. https://doi.org/10.17161/jomr.v6i1.8539

- Busemeyer, M. R., Garritzmann, J. L., Neimanns, E., & Nezi, R. (2018). Investing in education in Europe: Evidence from a new survey of public opinion. Journal of European Social Policy, 28(1), 34–54. https://doi.org/10.1177/0958928717700562

- Chzhen, Y., Gromada, A., Rees, G., Cuesta, J., & Bruckauf, Z. (2018). An unfair start: Inequality in children’s education in rich countries. Innocenti Report Card, 15.

- Cohen, D. L. (1989, December 13). Public schools embrace Montessori movement. Education Week, 12

- Cohen, D. K., Spillane, J. P., & Peurach, D. J. (2018). The dilemmas of educational reform. Educational Researcher, 47(3), 204–212. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x17743488

- Cossentino, J. (2009). Culture, craft, & coherence: The unexpected vitality of Montessori teacher training. Journal of Teacher Education, 60(5), 520–527. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487109344593

- Culclasure, B. T., Daoust, C. J., Cote, S. M., & Zoll, S. (2019). Designing a logic model to inform Montessori research. Journal of Montessori Research, 5(1), 35–49. https://doi.org/10.17161/jomr.v5i1.9788

- Debs, M. (2019). Diverse families, desirable schools: Public Montessori in the era of school choice. Harvard Education Press.

- Debs, M., & Brown, K. E. (2017). Students of color and public Montessori schools: A review of the literature. Journal of Montessori Research, 3(1), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.17161/jomr.v3i1.5859

- Debs, M., de Brouwer, J., Murray, A. K., Lawrence, L., Tyne, M., & von der Wehl, C. (2022). Global diffusion of Montessori schools: A report from the 2022 global Mnontessori census. Journal of Montessori Research, 8(2), 1–15. https://doi.org/10.17161/jomr.v8i2.18675

- Denervaud, S., Knebel, J. F., Hagmann, P., Gentaz, E., & Gillam, R. B. (2019). Beyond executive functions, creativity skills benefit academic outcomes: Insights from Montessori education. Plos One, 14(11), e0225319. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0225319

- Dereli İ̇man, E., Danişman, Ş., Akin Demircan, Z., & Yaya, D. (2019). The effect of the Montessori education method on pre-school children’s social competence – behaviour and emotion regulation skills. Early Child Development and Care, 189(9), 1494–1508. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004430.2017.1392943

- Dohrmann, K. R., Nishida, T. K., Gartner, A., Lipsky, D. K., & Grimm, K. J. (2007). High school outcomes for students in a public Montessori program. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 22(2), 205–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568540709594622

- Eacott, S. (2018). Beyond leadership: A relational approach to organizational theory in education. Springer.

- Eacott, S., & Munoz Rivera, F. (2021). Steiner 2021: The curation of contemporary education. Retrieved from http://handle.unsw.edu.au/1959.4/unsworks_77171

- Eacott, S., Munoz Rivera, F., Wainer, C., & Raad, A. (2022). Montessori education in Australian schools: charting a path. Retrieved from http://handle.unsw.edu.au/1959.4/unsworks_78686

- Edwards, C. P. (2006). Montessori education and its scientific basis. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 27(2), 183–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.appdev.2005.12.012

- Feez, S. (2013). Montessori: The Australian story of a revolutionary teaching method. UNSW Press.

- Gasco-Txabarri, J., & Zuazagoitia, D. (2022). The sense of patterns and patterns in the senses. an approach to the sensory area of a Montessori preschool classroom. Education, 3, 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2022.2032786

- Gill, M. G. (2007). Establishing Legitimacy for Montessori’s grand, dialectical vision: An essay review of Montessori: The science behind the genius, angeline stoll lillard oxford university press, New York (2005). Teaching and Teacher Education, 23(5), 770–774. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2007.01.008

- Gonski, D., Arcus, T., Boston, K., Gould, V., Johnson, W., O’brien, L., Roberts, M. & Roberts, M. (2018). Through growth to achievement: Report of the review to achieve educational excellence in Australian schools. Commonwealth of Australia.

- Guest, G., Namey, E., Chen, M., & Soundy, A. (2020). A simple method to assess and report thematic saturation in qualitative research. Plos One, 15(5), e0232076. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0232076

- Hatch, T., Corson, J., & den Berg, S. G. V. (2021). New schools in New York City and Singapore. Journal of Educational Change, 23(2), 199–220. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10833-021-09419-1

- Hennink, M. M., Kaiser, B. N., & Marconi, V. C. (2017). Code saturation versus meaning saturation: How many interviews are enough? Qualitative Health Research, 27(4), 591–608. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732316665344

- Holmes, C. (2018). Montessori education in the Ngaanyatjarra lands. Journal of Montessori Research, 4(2), 1–60. https://doi.org/10.17161/jomr.v4i2.6715

- Kass, D. (2021). New education at stanmore public school, Sydney 1919: The progressive image Paedagogica Historica. https://doi.org/10.1080/00309230.2021.1915344

- Ladwig, J. G. (2010). Beyond academic outcomes. Review of Research in Education, 34 113–141. https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X09353062

- L’ecuyer, C., Bernacer, J., & Güell, F. (2020). Four pillars of the Montessori method and their support by current neuroscience. Mind, Brain, and Education, 14(4), 322–334. https://doi.org/10.1111/mbe.12262

- Lillard, A. S. (2012). Preschool children’s development in classic Montessori, supplemented Montessori, and conventional programs. Journal of School Psychology, 50(3), 379–401. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2012.01.001

- Livstrom, I. C., Szostkowski, A. H., & Roehrig, G. H. (2019). Integrated STEM in practice: Learning from Montessori philosophies and practices. School Science and Mathematics, 119(4), 190–202. https://doi.org/10.1111/ssm.12331

- Lopata, C., Wallace, N. V., & Finn, K. V. (2005). Comparison of academic achievement between Montessori and traditional education programs. Journal of Research in Childhood Education, 20(1), 5–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/02568540509594546

- Malterud, K., Siersma, V. D., & Guassora, A. D. (2016). Sample size in qualitative interview studies: Guided by information power. Qualitative Health Research, 26(13), 1753–1760. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732315617444

- Marshall, C. (2017). Montessori education: A review of the evidence base. npj Science of Learning, 2, 11. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41539-017-0012-7 (1)

- O’donnell, D. (1996). Montessori education in Australia and New Zealand. Fast Books.

- OECD. (2020). Back to the Future of Education.

- Of, E., & International Commission on the Futures. (2021). Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education: Executive summary. UNESCO.

- Owen, S., & Davies, S. (2020). Maintaining an empowered school community: Introducing digital technologies by building digital literacies at beehive Montessori school. London Review of Education, 18(3), 356–372. https://doi.org/10.14324/LRE.18.3.03

- Peng, H. -H., & Md-Yunus, S. A. (2014). Do children in Montessori schools perform better in the achievement test? a taiwanese Perspective. International Journal of Early Childhood, 46(2), 299–311. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13158-014-0108-7

- Powell, M. (2022). Afterword. In T. Eissler (Ed.), Montessori madness: Australian edition. TBC.

- Pugh, K. J., & Bergin, D. A. (2005). The effect of schooling on students’ out-of-school experience. Educational Researcher, 34(9), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189x034009015

- Ruijs, N. (2017). The effects of Montessori education: Evidence from admission lotteries. Economics of Education Review, 61, 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2017.09.001

- Tobin, T., Boulmier, P., Zhu, W., Hancock, P., & Muennig, P. (2015). Improving outcomes for refugee children: A case study on the impact of Montessori education along the thai-burma border. The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 14(3), 138–149.

- UNESCO. (2021). Reimagining our futures together: A new social contract for education;executive summary. Paris: UNESCO.

- Varadharajan, M., Noone, J., Weier, M., & Brown, G. (2022). Amplify insights: Education inequity. Centre for Social Impact: UNSW Sydney.

- Vasileiou, K., Barnett, J., Thorpe, S., & Young, T. (2018). Characterising and justifying sample size sufficiency in interview-based studies: Systematic analysis of qualitative health research over a 15-year period. BMC medical research methodology, 18(1), 148. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12874-018-0594-7

- Whitescarver, K., & Cossentino, J. (2008). Montessori and the mainstream: A century of reform on the margins. Teachers College Record, 110(12), 2571–2600. https://doi.org/10.1177/016146810811001202