ABSTRACT

The theoretical literature on the meaning of qualification standards depicts a variety of definitions. Some definitions describe properties of examinees, whilst others rely on cohort-level or system-level characteristics. Different definitions can be compatible or contradictory. In this study, stakeholders’ views of the meaning of qualification standards in Scotland were collected, using focus groups (82 participants) and a questionnaire (918 participants). Almost 60% of questionnaire participants responded that standards tell us about performances on the assessment (criterion-referencing) and approximately 40% responded that they tell you about an underlying ability (construct-referencing). Few participants considered that maintaining statistical grade distributions every year were important. Discrepancies in views raise questions regarding how an examination board manages the political and technical process of maintaining public confidence in standards. Based upon this Scottish case, the authors argue that social settlements regarding qualification standards are a social contract, and a solely technocratic view of standards is conceptually inadequate.

KEYWORDS:

Within a society, there is a general impression that school-leaving qualification standards are understood. Most people who go through a national schooling system have shared experiences of school-leaving qualifications and their standards. In truth, there are likely differences in understandings of standards across settings and assessment cultures within a society. However, we have not identified empirical work that investigates stakeholders’ perceptions of the meaning of standards. To date, the literature on the definition of qualification standards is theoretical. When national assessment systems are compared across countries, distinctive ways of thinking about standards are thrown into sharp relief. During the Covid pandemic, qualification outcomes were hotly contested in Scotland (Hayward et al., Citation2023), leading to this research. In this article, we report stakeholder views about qualification standards obtained by focus groups and a survey. Based on this empirical work, we show multiple understandings of qualification standards co-existing. We outline previous work below, which has shown that different definitions appeal to explanations of standards at different levels of an ecological model. In the current paper, we address how national qualification standards are social contracts between stakeholders, who have varied and contrasting perspectives about what the qualification results mean.

During the pandemic, many countries chose to delay their national assessments (SQA, Citation2022a; UNESCO, Citation2020). As in the other parts of the British Isles, Scotland chose not to delay, but to issue grades based upon teacher judgements in 2020 and 2021 (SQA, Citation2020a, Citation2021a). In 2020, results were initially issued in Scotland based on statistically moderated teacher judgements, but the Scottish Government quickly reverted to unmoderated teacher judgements following a public furore over the results (SQA, Citation2021b, p. 49). Disquiet across society centred on the notion that existing inequalities were compounded by the use of historical outcomes data in the initial process of moderation of teacher judgements, which altered 26% of grades (SQA, Citation2020b). Public commentary in Scotland about standards in the context of disruption to expectations over national qualification standards represents an illustrative case in which to investigate empirically public understanding of curriculum-related qualification standards. From this case, we set out to generalise in terms of theory to other national assessment contexts.

National qualifications vary in terms of their governance and how they function within a country’s educational and labour market practices, history and broader culture. Standards are usually codified in policy. The Scottish Qualifications Authority (SQA) is the exam board responsible for national qualifications at senior-school level in Scotland. This is a nationalised system in which the organisation is government-led. Other national systems involve a commercial market (such as in the US) or quasi-market, with regulation (such as in England or India: Opposs et al., Citation2020). A nationalised system such as that operating in Scotland does not have to contend with multiple examination bodies’ standards for the same qualification and SQA is both exam board and regulator for senior-school and college-level qualifications.

National upper secondary phase qualifications in Scotland

SQA is responsible for National Qualifications (NQs), which are those most often taken in the upper secondary school. They are organised for each subject from Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework (SCQF) levels 1–5 (e.g. National 5) and then at Higher (SCQF level 6) and Advanced Higher (SCQF level 7). This research focused on National 5, Highers and Advanced Highers, which have most importance for accessing further and higher education and employment. Highers and Advanced Highers are often required to progress to university. Until 2019, assessment of most of these qualifications included examinations, aggregated with the results of coursework or practical components which were marked by teachers or lecturers. The latter were quality assured through internal and external moderation procedures. Across these qualifications, in 2019 assessment for most subjects included a final exam that was worth between 51–75% of the marks upon which grades were based (Stobart, Citation2021, p. 11).

In 2020, during the pandemic, instead of the usual assessment process, teachers were asked to provide SQA with estimated grades (A–D) together with a rank-order for learners for each subject at National 5, Higher and Advanced Higher levels. Historical attainment of the school or college was used together with those teacher judgements to moderate outcomes statistically in the first instance. Those results were then issued provisionally but stimulated such a strong, negative public reaction to the perceived unfairness of the moderation process that the Scottish Government and SQA reverted to results based upon the unmoderated teacher judgements.

With more time to develop procedures, an alternative certification model was introduced in 2021. Teachers and lecturers were able to base their judgements on students’ performances in classwork and assignments. Quality assurance was through local moderation with other schools and colleges and a sampling of evidence by SQA. In practice many schools and colleges based their grades mainly on internally marked SQA assessments circulated late in the spring, rather than classwork and assignments.

Baird (Citation2018) distinguished three types of assessment paradigms: psychometric; outcomes-based; and curriculum-based. Psychometric assessments focus on the measurement of a single, latent variable and are usually test-based, often using a multiple-choice format. The US SATs are one example of a psychometric approach to national assessment, comprising assessments of evidence-based reading and writing and maths (College Board, Citation2022). Psychometric assessments often have no associated curriculum, as they are designed to assess an assumed internal characteristic of individuals. Outcomes-based assessments focus on the assessment of competencies, often through practical work or other forms of authentic assessment. Scottish Vocational Qualifications are an example of outcomes-based assessment (SQA, Citation2018). The National 5, Higher and Advanced Higher qualifications are curriculum-based assessments, which set out a curriculum as educational objectives. Learners are assessed in terms of their attainment of these objectives. Assessment formats vary, but often involve a combination of a national examination and coursework or practical performances. These ways of thinking about assessment influence what people think assessment is and how quality and standards should be designed into the assessment process and outcomes.

Defining national qualification standards

The meaning of standards in qualifications has been considered in the academic literature, with a particularly active field in the UK for over 30 years (eg Baird, Citation2007; Baird et al., Citation2000, Citation2018; Cresswell, Citation1996; Newton, Citation1997, Citation2005, Citation2010). However, the US literature dominates the field of education, due to its size and English being the international language of science. The US has a psychometric approach to assessment which is not shared universally across national qualification systems around the world (Baird et al., Citation2018). There is also a body of work on outcomes-based assessment (see Meadows et al., Citation2023) which largely relates to vocational education, but some of the ideas (e.g. explicit assessment criteria) have permeated the thinking on curriculum-related and psychometric assessments.

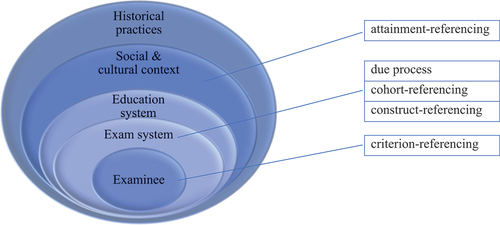

Different definitions of the meaning of assessment standards have been proposed. The most important definitions were organised in an ecological model () by Baird et al. (Citation2018, p. 292). An ecological model is useful here because these definitions coexist at different levels of explanation (), with some referring to psychological aspects of the examinee, whilst others address national concerns. We explain the meaning of these terms below. Our purpose here is not to elaborate the advantages and disadvantages of each approach, nor to proselytise for a particular definition, but to consider the meaning of qualification standards to stakeholders: whether there is consensus or contradiction; what this implies for their utility in society; and the consequences for assessment standards theory.

Beginning at the examinee level, criterion referencing (Glaser, Citation1963; Popham & Husek, Citation1969) is the notion that the attributes of candidates’ knowledge, skills, competencies or psychology can be written as a series of criteria, which can then by applied to assessment evidence by a suitably qualified judge. This approach could be used with a single or a very large group of candidates and does not rely upon statistical information. The nub of this approach is that relevant learners’ characteristics are faithfully represented by grading. Vocational assessments often use this approach to assessment, since meeting the required criteria is important for qualifications, such as those required to become an electrician. Having statistical quotas attached to such a qualification would have obvious disadvantages. As such, statistical pass rates are irrelevant.

Other definitional ways of thinking about standards go beyond the examinee level. A due process approach (Cizek, Citation1993) resides at the exam system level. Under this way of thinking, grading should be transparent. Rules for grading should be set out in advance and be followed. Note that those rules may or may not entail grading criteria, characteristics of the examiners, procedures for quality assurance and so on. The important point of a due process definition is that there is a specified process, which has been followed. Beyond that, speculation or protests about criteria, statistics or other aspects are moot, to this way of thinking. Appeal processes often rely on a due process definition of standards.

Another exam-system level way of thinking about standards is cohort-referencing (Wiliam, Citation1996). In this approach, a proportion of the test-takers is given each of the grades, such as 10% being given the top grade and 50% passing. Strictly speaking, what learners must demonstrate to get those grades is out of the scope of this way of thinking about standards. There is a myth that this system was used for A-level exams in England (Newton, Citation2022), but it has been the basis of grading in national examinations in Georgia, South Korea, South Africa and Victoria in Australia (Baird et al., Citation2018).

Construct-referencing (Wiliam, Citation1996) involves standards that tell us about the levels of learners’ cognitive abilities. These are ‘latent’ traits to this way of thinking, which are not directly observable, but can be identified using statistical (psychometric) techniques which have screened out error in the measurement. A learner’s level on the trait in question is defined in relation to others who took the assessment, as well as in relation to the assessment itself. This approach to defining standards is used in the international test, PISA (OECD, Citation2023). To this way of thinking, difficulty of the items and ability of the population are co-defined (Andrich, Citation2004) and appeals to ways of thinking of ability outside of the test are irrelevant.

We see above that within the assessment literature, standards are defined in terms of cognition (knowledge and skills) and processes (e.g. ranking), with little recourse to the social aspects of standards. A largely separate literature on the sociology of examinations has focused on this to a far larger extent, with authors such as Broadfoot (Citation2021) outlining the ways in which qualification grades are embedded in societies. Their impacts can be felt not only on life chances, but also upon how people perceive their identities (Hanson, Citation1993). Important though this literature is, it does not address how standards are set, nor their definition.

Attainment-referencing (Newton, Citation2011; Baird et al., Citation2000) defines standards in terms of the level of performance learners demonstrate in their assessments, after taking into account the level of difficulty of those assessments. As such, processes to implement this definition involve the amalgamation of a range of information – quantitative and qualitative – about the performances and the difficulties. This is the definition in use in qualifications in Scotland and England (Baird & Gray, Citation2016; Newton, Citation2022). In response to a period of qualification reform, Cresswell (Citation2003) introduced what became known as a comparable outcomes approach to setting standards. Essentially, he argued that it was unreasonable at times of reform to grade students severely since the education system was in a period of adjustment. Instead, the population-level outcomes should stay fairly stable each year. This is an ethical argument, about fairness for a cohort who must compete in the labour market and for entrance to further and higher education with those from earlier and later cohorts. We do not draw upon this definition in the remainder of the paper but mention it here because this is a break from the technocratic ways of thinking about standards, since the justification is not simply to maintain statistical outcomes, such as in norm-referencing or performance outcomes, such as in criterion-referencing. Instead, the rationale concerns what is socially and morally acceptable. The comparable outcomes approach was adopted as the official standard-setting policy for the introduction of national qualifications in England when reformed examinations were introduced (Ofqual, Citation2017), though it has never been the policy in Scotland. Use of comparable outcomes relates to attainment-referencing because in practice, information about students’ performances was also taken into account, where this represented strong evidence (Newton, Citation2022).

Social contract theory

Although it has its roots in political philosophy, social contract theory has increasingly been used to explore and examine a wider range of fields including healthcare (Cruess, Citation2006; Korn et al., Citation2020; Senthil et al., Citation2015), business and economics (Francés-Gómez, Citation2020; Shafik, Citation2021), and education (Sobhy, Citation2021; UNESCO, Citation2021). We believe we are the first to use this theory to examine theories of qualification standards, an area which until now has been dominated by technocratic approaches, ones which tend to see the issues as technical or ‘scientific’ in nature. In this paper, we make a case for the importance of a focus on the social nature of standard setting. We outline briefly some of the key concepts in social contract theory here and return to these in the discussion to illustrate their pertinence to standard setting, using our data on stakeholder perceptions of SQA’s response to the Covid pandemic as an illustrative case.

Social contract theory assumes that individuals give up some portion of their natural freedom or rights by entering into a ‘social contract’ with other members of their community or society. This contract relies on stakeholders performing specific roles for the benefit of the whole, and in many of its original formulations emphasised the role of the state in providing safety and security for its citizens (see, for example, Citation1651, CitationLocke [1823]). For qualifications, we posit that individuals submit themselves to normative, standardised testing on the promise of their results having currency in the labour and education markets. The state has a role in ensuring the currency of qualifications, through maintaining public confidence in their results. Exam boards have specific duties in this regard. When public confidence is punctured, expectations of fulfilment of the social contract are broken, bringing critique and calls for reparation. Part of the social contract relates to the standards of the qualifications, which underpins the currency. If stakeholders’ views of standards are divided, this poses problems for the fulfilment of the contract and management of the system since stakeholders are operating with different understandings of what the contract entails. Issues of power to define and influence the nature of the contract are then highly pertinent.

Research policy context

Findings of this project will have been affected by the public discussions and political debates on national assessments that arose during the pandemic. Issues of trust, dependability and inequality in the national system were high profile. Further, a series of public reviews of the Scottish curriculum and qualifications system reported (Muir, Citation2022; OECD, Citation2021; Stobart, Citation2021) or were announced during the period of data collection (Hayward, Citation2023). Whilst there were conclusions about the highly respected nature of the qualifications system (OECD, Citation2021), there was also critique of the extent of curriculum alignment (OECD, Citation2021; Stobart, Citation2021) and the way in which assessments were operated in 2020 (Priestley et al., Citation2020). It is in this context that the data were collected.

Methods

The qualifications under discussion involve high-stakes assessments, the results of which can lead to rewards or sanctions for students, teachers and institutions (Madaus, Citation1988, p. 29). To examine perceptions of standards, fairness and trust, this study adopted qualitative and quantitative methods covering several stakeholder groups to consider a range of research questions. This paper focuses on one of the project’s research questions:

How do people in different communities understand the term standards in the context of qualifications? What do they believe matters?

This is an exploratory, sequential, mixed-methods study (Tashakkori & Teddlie, Citation1998). Findings from the qualitative stage informed the design and interpretation of the quantitative stage and were integrated thematically. The study aimed to give participants a voice, from their own perspectives, about fairness and standards in NQs. In a time of such disruption and upheaval, when there had seemingly been a sudden change in public perception, collaboration with those experiencing this disruption was crucial to understanding their perspectives. A participatory approach to the research was vital and was incorporated throughout the process. This rebalancing of power dynamics is a goal of participatory models, in contrast to more traditional methods of research (Nind, Citation2021; Reason & Bradbury, Citation2008).

Focus groups

Focus group participants were from key stakeholder groups representing learners, school and college staff and users of qualifications: secondary school Year 5 or Year 6 pupils (aged 17 or 18) and Further Education (FE) college students undertaking Scottish Higher NQs in 2021; parents or carers of those school pupils; school and college senior managers and teaching staff delivering those qualifications in 2021; Scottish university and FE college admissions staff; employers who use SQA qualifications in recruitment; and a journalist ().

Table 1. Focus group participants.

Stakeholder participants from schools were volunteers from possible participant schools identified by Scotland’s six cross-local authority Regional Improvement Collaboratives using deprivation index profiles as a sample stratification variable. Admissions staff were nominated by HE institutions with which the researchers had personal contacts; recruitment of employers was though researchers’ personal contacts; and Scottish media organisations were identified and contacted by researchers and invited to nominate participants.

Focus groups were conducted online due to Covid restrictions in Spring 2021. Nineteen focus groups of approximately one hour duration were held, comprising participants from 27 schools, 14 colleges, three higher education institutions, three employers and one media organisation. Participants were provided with the broad questions for discussion in advance, asking for their response to the 2020 results, their ideas about fairness in qualifications, their understanding of standards and what they thought might be learned from their experiences for the future of qualifications. They were encouraged to share the questions with each other and with colleagues in the wider school or college community before their focus group discussion, to better represent that community’s views.

Focus group discussions were recorded, automatically transcribed and edited for accuracy. All data were anonymised. Transcriptions were coded using CAQDAS software (NVivo 12). A mix of inductive and deductive coding was used, with deductive codes based upon the definitions of standards in the literature (outlined above). Two researchers coded independently; any differences were discussed, the codebook was revised, and coding was repeated until agreement was reached and themes could be identified reliably.

Online survey

An online stakeholder survey was created to allow a larger number of participants to have their voices heard as part of the research process. The questionnaire included five main themes: standards; trust and communication; teacher assessment; the future of assessment in Scotland; and lessons learned from the pandemic. There were two rounds of piloting, with samples of learners, teachers, college lecturers, parents and carers invited to give feedback to be incorporated into the final questionnaire design.

A link to the survey was sent to half of all secondary schools and to all colleges in Scotland and distributed electronically by an SQA co-ordinator present in each institution. It was sent to learners and practitioners engaged in the National 5, Higher and Advanced Higher qualifications, and to parents and carers of those learners. The survey was live for six weeks during November and December 2021 and was fully completed by 918 respondents (). Participants were fairly evenly split between learners (38%), teachers and lecturers (33%) and parents and carers (28%). A small number of respondents identified themselves as ‘other’, including HEI admissions staff. More than half of the respondents were associated with a state secondary school (). There was a higher representation from independent schools (33%) than would be representative of the Scottish education system (4.2% of learners; Scottish Council of Independent Schools, Citation2022), particularly amongst learners.

Table 2. Survey participants.

The survey was created and published using Qualtrics (www.qualtrics.com). Data were then analysed using SPSS. Free-text questions were included, which was particularly important given that the project was designed to allow participants to have their voices heard. These provided rich data, with respondents giving detail on their personal views and experiences on the questionnaire topics, and these were analysed qualitatively. Research ethics approvals were obtained for the study ahead of commencing data collection through the University of Oxford (ED-CIA-21-157) and University of Glasgow (400200142) ethical approval procedures.

Findings

The meaning of standards to stakeholders

Focus group participants were asked what the term ‘standards’ meant to them in relation to the NQs they had experienced as learners, teachers, managers and users of those qualifications, including some vocational qualifications. Responses were coded in relation to definitions outlined in the introduction to this paper (), though the terms themselves were rarely (in some cases never) used directly by participants. Several terms including ‘standards’ and ‘standardised’ were used, though not always in the technical or ‘expert’ sense. Within a focus group, discussions often ranged across various definitions; and the speakers sometimes argued against the use of a particular definition. Some respondents, especially learners, had understandings which did not correspond to any of the definitions. For example, they spoke of standards as a kind of currency (four focus groups). Idealised statements were made, such as:

…Standards probably are a true representation of knowledge gained while studying a subject in a fair and consistent approach, in a way that is equal to everyone else that is doing that examination. (College student)

Table 3. Definitions of standards coded in focus group discussions.

Very few participants discussed standards in a manner that could be classified as attainment-referencing, even though it is the SQA policy definition used in normal years (two focus groups). The following quotation from a school leader is an example, though use of the term ‘intelligence’ does not strictly fit with the term ‘attainment’:

…If there was a particularly nasty paper, they’d lower the percentage … I think the point being made it’s on your group as a whole’s intelligence … but at the end of the day I think it’s just them trying to make papers that are somewhat equal in difficulty … (School leader)

Most of the focus groups featured dialogue consistent with criterion-referencing (15 focus groups). Participants spoke of ‘criteria’, or ‘guidelines’, sometimes at a generic, qualification level and sometimes subject-specific.

The standards are obviously the guidelines that they’re setting out that they want … within the different levels of education there will be different standards. (College student)

I think the standards are about the criteria … that all pupils and staff apply to meet the demand for a course at an SCQF [Scottish Credit and Qualifications Framework] level.(School leader)

My understanding of the standards is the expectations are sort of minimum standard that students have to have achieved to pass the course. Basically, about the range of things they should be able to do and obviously within National 5 and Higher courses and Advanced Higher questions. You get A, B or C which allows for that kind of difference that we have within a range of students in a class. That’s my understanding of the standards for all students in Scotland. (School leader)

Approximately half of the focus groups featured discussions of standards that were consistent with cohort-referencing (nine focus groups). An admissions officer expected broad stability in outcomes at a national level, feeling that stability in outcomes might be expected, even if smaller cohorts of children within schools did not show the same stability year on year:

…You would hope that year on year the population would kind of be similar … . You might have exceptions one year where there’s a particularly good year or a particularly bad year, but all in all you would think that the population, it statistically should even out. (Admissions officer)

A small number of discussions related to due process definitions (four focus groups). For example, the following excerpt discusses criterion-referencing and due process definitions combined and was coded for both:

They’re about … partially setting the rules … on how we conduct assessments, and then about the grade-related criteria. But I think it’s a combination of all of that, so not just agreed criteria for the actual assessments, but for the conduct of them how we apply them. (School leader)

Focus group participants did not use the technical jargon of the assessment field. Problems in delivering idealised versions of standards were sometimes recognised, but often the compromises that must be made in practice were not recognised. For example, concerns about inconsistency in teacher assessments were not always matched by recognition that it can in any case be difficult to produce consistent outcomes at a national level each year. Policymakers must make choices in implementing standards policies and the focus groups raised questions about the decisions stakeholders would make if they had this power.

Six groups noted the social element of standards through discussion of the importance of ‘public confidence’ or trust as underpinning standards:

They need to be reliable. People need to be able to say ‘actually we can trust that’. If you’ve got a pupil with a certificate in a subject at a level and a grade, we should be able to say, ‘OK, we can trust that that pupil wasn’t being let off the hook that year’.(School Teacher)

Discussions in 12 focus groups referred to standards in ways that we have classified as ‘Other’, using phrases that were self-referential, appealed to fairness, questioning whether there were standards and so on:

Qualification standards are basically what can be achieved … (College Student)

…It is something that’s consistent and it should be equal and fair across all sectors.(College Lecturer)

To me it sounds like marketing … to give you a sense that there’s a rigorous thought-out process behind all that decision-making … as a sort of tagline, it’s sort of hollow.(Employer)

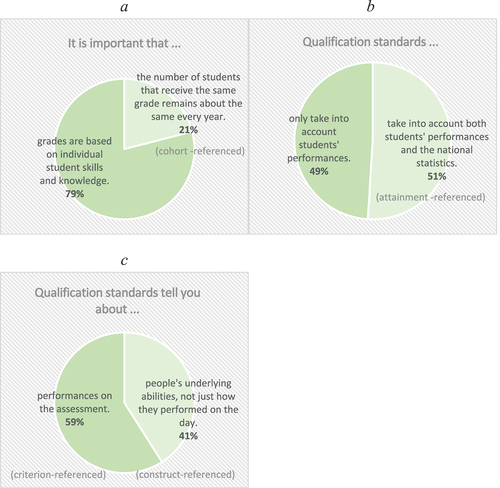

To explore stakeholders’ views further, we included four forced-choice items in the questionnaire study. Four definitions of standards were explored: criterion-referencing; cohort-referencing; attainment-referencing; and construct-referencing. As these terms are not in common parlance, we did not ask about them directly. Instead, we presented statements that aligned with the definitions ().

Most respondents prioritised the importance of grades representing students’ skills and knowledge over maintaining a statistical distribution every year (). This implies a rejection of cohort-referencing, though it seems that half of the respondents recognised that, in practice, qualification standards take into account the national statistics, which would imply an attainment-referencing definition (). Thus, we see a contradiction between stakeholders’ priorities and national policy. Support for standards indicating individual skills and knowledge could align with criterion-referencing or with construct-referencing. Here, we see a divide, with a sizeable minority believing that standards tell us about underlying ability, not just performance on the assessment (). Appeals to underlying ability align with a construct-referenced definition. There was support for criterion-referencing (59%), construct-referencing (41%) and cohort-referencing (21%) – in that order.

Analyses by stakeholder group showed that views were remarkably consistent regarding the use of statistics in standard-setting policy (item in ). However, learners were much less likely to ascribe to construct-referencing (item in ), with only 33% believing that standards indicate underlying abilities. Additionally, support for a cohort-referencing approach to standards from teachers and lecturers was scant (item in ), with only 5% supporting the notion that the statistical distribution should remain stable from year to year.

For those who supported criterion-referencing (n = 537), a minority considered that it was important that the statistics remained stable each year (n = 96; ). This group might have had in mind a standardisation mechanism to bring statistical stability to examiners’ or teachers’ judgements, as the following comment indicated.

Moderation needs to take place between different schools to prevent grade inflation. (Teacher/Lecturer, survey response)

Table 4. Cross-tabulation between views on the importance of statistics and the nature of the construct being assessed.

Equally, a small subset (n = 98) of those who supported construct-referencing (n = 381 in total) considered that stable statistics were important. Construct-referencing and criterion-referencing are both compatible with the notion that grades are based on individual student skills and knowledge, but in the former case those are underlying abilities, and, in the latter, they are performances on the day of the assessment.

Trust in the exam board and support for pandemic assessment policies

Most questionnaire participants trusted SQA to deliver qualifications in 2021 (57%), but a higher proportion indicated that they trusted SQA to deliver prior to the pandemic (83%). Qualitative comments in response to the questionnaire from those who did trust SQA argued that they had made the best decisions in a difficult situation and had been politically scapegoated. The following quotation from a focus group discussion illustrates this:

They have been made a scapegoat by the Government so therefore trust has been eroded which makes it difficult to maintain the status quo. (Teacher/Lecturer, focus group discussion)

Interestingly, whilst three quarters of questionnaire participants thought that use of teacher assessment during the pandemic was the right decision (76%), only half of them (53%) considered that it was fair. Just over a quarter (28%) of participants thought that teachers were not well prepared to make judgements of learners’ work in 2021. Relationships between teachers and learners were thought to influence teachers’ grade judgements by almost half of the participants (45%) and a quarter (26%) considered that parental pressure on teacher assessment was a concern. The absence of examinations during the pandemic resulted in public commentary and debate about their return. Only half of questionnaire respondents (52%) thought that examinations were the best way to assess learners for NQs and a majority considered that teachers (64%) and learners (59%) should have a choice of assessment format in NQs, including online and remote formats. Eighty percent of respondents wanted to see change of some kind in the national qualification system.

Trust between stakeholders

In both the survey and focus group discussions, a major threat to standards was the risk that schools or teachers might game the system for their own advantage or that of their pupils.

Even if teachers say ‘we don’t have favourites’, there are children they like more and they’re getting on better with than with others. I think that will have an effect on the grades that teacher gives that particular child … (Parent, focus group discussion)

Teachers will always give a borderline student the benefit of the doubt. (Pupil, survey response)

Participants also spoke of the importance of schools, colleges, employers and universities proclaiming their trust in the maintenance of standards during the disruptions caused by Covid:

Schools themselves, educational authorities, employers, universities, they’ve got to speak up and say, this was a very serious event for the whole of society. … I think schools and education authorities have got to speak up, against anybody that might say, ‘Oh no, there’s no way that was as good as when I was a pupil’. There’s no way you went through anywhere near what these kids are going through. So, the schools and education authorities have got to let people know that you’re doing the best you can to assess the quality of the pupils that are coming out of the system and going into the colleges and work and all the rest of it. It was exceptional times and the schools should be telling people that, and education authorities should be telling people that, so there’s not any kind of scepticism surrounding any of the Covid generation of pupils that are going to be coming out in the last two or three years, and, well, the next six to seven years actually, because we’re talking about the kids there who are with them right now. So, it’s behoven on their education authorities and their own schools to really get the message out there, you know, these pupils did a sterling job, you know, under exceptional circumstances. We are proud of them. (School parent, focus group discussion)

Underlying these discussions is the implied trust between stakeholders that everyone is following the ‘rules’ of the social contract as best they can. O’Neill (Citation2002, Citation2013) reframed theories of trust to emphasise that accountability mechanisms put in place to increase trust often act instead to undermine it. In the foregoing quotes we see a system in which many of the mechanisms usually put in place to ‘support’ trust in qualification standards were disrupted. Stakeholders were then required to rely more heavily on trust between each other: trust that other people would not abuse the system and trust that grades would ultimately be legitimised by the end users to maintain the system and uphold the social contract.

General discussion

Different interpretations of the very definition of standards abound in the research literature and amongst wider stakeholders, as this research shows. How people conceive of qualification standards has previously not been researched empirically, with most of the literature being concerned with conceptual analysis. The resulting different definitions mean that people interpret the meaning of grades in distinctive ways. There are also a variety of expectations about how the outcomes should be brought about as well as, ultimately, about what the distribution of grades should be at a national level.

Qualifications are important not only as a signal of examinee knowledge and skills. Qualification results articulate with societal processes, influencing people’s life chances. Embedded in society, they require public confidence for their currency. Trust in the exam board to deliver qualifications was seriously dented in Scotland in 2020 because some people did not feel that the results were fair for them as individuals, or for poorer sections of society. The standardisation process initially adopted in 2020 used the results for schools and colleges in previous years as part of the process to allocate grades. Within each subject and qualification in a school or college, the grades were distributed on the basis of teachers’ rank-ordering of pupils. Whilst there is always a strong association between socioeconomic status and grades, stakeholders baulked at the explicit use of schools’ previous results to set standards.

Although based on statistics, cohort-referencing relies on rank-ordering of pupils across schools, through their performances on the assessment. Thus, there can be an appeal to meritocracy. Criterion-referencing relies upon pupils’ performances being judged to have met the criteria and therefore there can also be an appeal to arguments of meritocracy. However, as previously outlined, neither can be a guarantee of meritocracy because stakeholders (variously) would like standards to represent place in rank-order, performance changes over time, consistent statistical outcomes between years and to be independent of the school attended or the examiner who marked the work. This wish list, which involves different ways of seeing meritocracy, cannot be achieved simultaneously.

Our data showed clear divisions within Scottish society regarding what standards do or should represent. The favoured definitions do not operate well in tandem, nor can they be delivered perfectly. Since stakeholders do not agree on their prioritisation, managing a national qualification system requires skilful political nous at times of stability and would be even more daunting at times of change or crisis. Fundamentally, the qualification system remains a social system, and if stakeholders lose faith in the system, the loss can be fatal, regardless of the technical rigour of the approach taken. Upon entering a social contract, power is handed over willingly (although consent is often taken as implicit) and authority is legitimised by society. As such, this authority can be withdrawn if those in power are perceived to no longer be holding to their end of the bargain. Certainly, policymakers can lose their jobs for apparently mishandling standards.

Additionally, our data, and further research (SQA, Citation2022b) showed that stakeholders had strong views on a range of issues that impact on standards. While many learners felt that the grades they received in 2021 (SQA, Citation2022b) and 2022 (SQA, Citation2023) were fair to them as individuals, the proportion who agreed that the grades received by all learners were fair was significantly lower. Learners in 2021 who felt that their grades were unfair mentioned a variety of issues including the volume of assessment, the lack of study leave and learning loss. Some learners were concerned about different approaches across the country. Many of these factors are not directly related to any theoretical understanding of standards. They relate instead to inequalities in access to teaching and technology during lockdown, to information about and support for assessment, and to insufficient impartiality, consistency and validity of assessment, which would impact upon opportunities for individuals to demonstrate that they had met the standards.

Standard-setting represents a social contract with stakeholders, with its justification deriving from the promise of meritocracy. So, an interesting question is what warrants for a claim of meritocracy are accepted in different societies, at different points in time. A pre-pandemic analysis of policy statements by SQA indicated that an attainment-referencing approach was in fact used, though the statements themselves implied criterion-referencing (Baird & Gray, Citation2016). It can be difficult for policymakers to be explicit about how standards are defined because there are political differences of opinion. Policymakers in some countries could not participate in the project which resulted in the book on what standards mean in different countries because the issues were too contentious (Isaacs, Citation2018, p. 340). Political shifts can also lead to differences between the philosophical and theoretical impetus for assessments and policy changes can be made to address these political shifts. For example, in Scotland, staged (unit) assessments were removed from NQs to address the workload burden of assessment, when they had been a foundational principle of the design of those qualifications (SQA, Citation2021b).

Attainment-referencing attempts to handle public confidence issues in a way that engages with the social and cultural dimensions, by utilising a broad range of evidence, including policy. This very feature also allows it to be interpreted differently by those with different perspectives on standards. Additionally, since the weighting given to evidence about standards is not formulaic, there is room for manoeuvre, if necessary, when the policy climate changes. Public confidence in those taking the decisions about standards is therefore very important to maintaining the social contract.

During the pandemic, with equity and inclusion issues coming more to the fore, there was a shift in the demands of the social contract. Bureaucratic organisations such as exam boards are not necessarily equipped or well placed to adapt under such circumstances. As such, political leadership is required. The disruptive context of the pandemic meant that qualification results in Scotland were a lightning rod for wider concerns about equality (Hayward et al., Citation2023), which impact on agreed approaches to standards. Politicians led decisions regarding grading processes and reversed their decision in Scotland in 2020, openly taking both authority and responsibility for them. The social contract that normally prevails for national qualifications was punctured, with the values-based, political infrastructure being laid bare.

Different relationships between political processes and assessment organisations played out in different parts of the British Isles, the details of which cannot be fully discussed here (see for example, Doyle et al., Citation2021; Ozga et al., Citation2023). Though this research focuses on empirical work in Scotland, we pose that the way in which standards are set, and their definitions, are a form of social settlement in all societies and are a social contract, however uneasy that settlement might be. Elucidating how these social contracts are navigated and how this varies across time and contexts will take the literature on qualification standards beyond the industry-insider, technocratic perspective that has previously been critiqued (e.g. Lawn, Citation2008).

Limitations

Although this research included over 1000 participants, there is not a representative sample of Scottish stakeholders. Independent schools were overly represented in the sample. Findings may not, therefore, be accurate reflections of societal views on qualification standards during the pandemic. Results showing that there were different understandings of the term, however, are unaffected by the unrepresentative nature of the sample. Whilst we seek to generalise theoretically from this case in Scotland, further data on how social contracts operate in other countries is needed. Indeed, it is remarkable that no empirical work could be identified on stakeholders’ definitions of qualification standards to date and further work on this important topic is warranted.

Conclusion

This research has shown that there are assorted stakeholder views on what qualification standards mean, some of which may be disregarded as wrong by those managing the system. However, some of the differing perspectives are simply addressing explanations of standards at different levels of the education system. As such, they may be acceptable definitions to a greater or lesser extent, even if they do not explain the entirety of how standards are set and what they mean. For example, assessment standards can be seen as providing information about what test-takers know and can do (criterion-referencing) as part of an attainment-referenced approach, which also takes candidates’ performances into account. But attainment-referencing goes beyond information about candidates’ performances, to take into account a range of information, so standards are not dictated by these performances in attainment-referencing.

Negotiating a strong social contract is a political process, which may encompass concerns that are not traditionally considered to be the business of assessment. Speaking the language of technocracy and approaching these issues as scientific and objective is part of the meritocratic logic of assessment, but political work goes into the management of national qualification systems to bolster the social contract. As a disruptive crisis, the pandemic exposed the criticality of that political work. During the pandemic, there was vocal disquiet about issues relating to fairness and the technocratic nature of the exam board, SQA. However, industry-insiders experience continual contestation over the social contract of standards, and although this was more acute during the pandemic, it is a permanent part of setting policy in high-profile national qualifications.

The focus on inequality by protestors (Hayward et al., Citation2023) threw into sharp relief the inadequacy of technocracy as an exclusive response to stakeholder concerns. However, managing qualification standards also requires the application of this technocratic knowledge, or new procedures for tackling assessment problems must be invented afresh. Qualification standards are a social settlement – a social contract – between stakeholders themselves as well as political leaders of the system. Examination boards mediate and manage this social contract with the aim of maintaining public confidence in the qualifications: a political process, as much as a technical one.

Acknowledgements

We would like to acknowledge the contribution of the following members of the project team to the design of the study and data collection: Professor Louise Hayward and Ernest Spencer (University of Glasgow), Laura Wilson (SQA) and Ashmita Randhawa (University of Newcastle). Additionally, we would like to thank the anonymised participants in this research.

Disclosure statement

This research was funded by SQA and three of the authors have formal relationships with SQA, either as committee member (Baird) or employees (Allan, Macintosh). Positions in this paper are those of the authors and not the funder.

Additional information

Funding

References

- Andrich, D. (2004). Controversy and the Rasch model: A characteristic of incompatible paradigms? Medical care, 42(1), 7–116. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.mlr.0000103528.48582.7c

- Baird, J. (2007). Alternative conceptions of comparability. In P. E. Newton, J. Baird, H. Goldstein, H. Patrick, & P. Tymms (Eds.), Techniques for monitoring the comparability of examination standards (pp. 124–156). Qualifications and Curriculum Authority.

- Baird, J. (2018). On different paradigms of educational assessment: Implications for the relationships with learning and teaching. British Psychological Society Vernon Wall Lecture, 1(37), 4–28. https://doi.org/10.53841/bpsvern.2017.1.37.4

- Baird, J., Cresswell, M. J., & Newton, P. N. (2000). Would the real gold standard please step forward? Research Papers in Education, 15(2), 213–229. https://doi.org/10.1080/026715200402506

- Baird, J., & Gray, L. (2016). The meaning of curriculum-related examination standards in Scotland and England: A home–international comparison. Oxford review of. Oxford Review of Education, 42(3), 266–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2016.1184866

- Baird, J., Isaacs, T., Opposs, D., & Gray, L. (2018). Examination standards: How measures and meanings differ around the world. UCL IOE Press.

- Broadfoot, P. (2021). The sociology of assessment: Comparative and policy perspectives: The selected works of Patricia Broadfoot. Routledge. https://www.routledge.com/The-Sociology-of-Assessment-Comparative-and-Policy-Perspectives-The-Selected/Broadfoot/p/book/9780367616724

- Cizek, G. J. (1993). Reconsidering standards and criteria. Journal of Educational Measurement, 30(2), 93–106.

- College Board. (2022). SAT understanding scores. https://satsuite.collegeboard.org/media/pdf/understanding-sat-scores.pdf

- Cresswell, M. J. (1996). Defining, setting and maintaining standards in curriculum-embedded examinations: Judgemental and statistical approaches. In H. Goldstein & T. Lewis (Eds.), Assessment: Problems, developments and statistical issues (pp. 57–84). John Wiley.

- Cresswell, M. J. (2003). Heaps, prototypes and ethics: The consequences of using judgements of student performance to set examination standards in a time of change. University of London Institute of Education.

- Cruess, S. R. (2006). Professionalism and medicine’s social contract with society. Clinical Orthopaedics & Related Research, 449, 170–176. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.blo.0000229275.66570.97

- Doyle, A., & Lysaght, Z. & O’Leary, M. (2021). High stakes assessment policy implementation in the time of COVID-19: The case of calculated grades in Ireland. Irish Educational Studies, 40(2), 385–398. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1916565

- Francés-Gómez, P. (2020). Social contract theory and business legitimacy. In J. D. Rendtorff (Ed.), Handbook of business legitimacy: Responsibility, ethics and society (pp. 277–295). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-14622-1_29

- Glaser, R. (1963). Instructional technology and the measurement of learing outcomes: Some questions. The American Psychologist, 18(8), 519–521. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0049294

- Hanson. (1993). Testing testing: Social consequences of the examined life. University of California Press.

- Hayward, L. (2023). It’s our future – Independent review of qualifications and assessment (report, 22 June). Scottish Government. https://www.gov.scot/publications/future-report-independent-review-qualifications-assessment/

- Hayward, L., Baird, J., Godfrey-Faussett, T., Rhandawa, A., Allan, S., MacIntosh, E., Hutchinson, C., Spencer, E., & Wiseman-Orr, L. (2023). National qualifications in Scotland: A lightning rod for public concern about equity in the pandemic. European Journal of Education, Research, Development and Policy, 58(1), 83–97. Special Issue: Trust in standardised assessments. https://doi.org/10.1111/ejed.12543

- Hobbes, T. (1651). Leviathan, or, the matter, form, and power of a common-wealth ecclesiastical and civil. Oxford University Press. https://global.oup.com/academic/product/thomas-hobbes-leviathan-9780199602629?cc=gb&lang=en&

- Isaacs, T., & Gorgen, K. (2018). Culture, context and controversy in setting national examination standardsExamination standards: how measures & meanings differ around the world. In J. Baird, T. Isaacs, D. Opposs, & L. Gray (Eds.), Chapter (Vol. 15). London: UCL Press.

- Korn, L., Böhm, R., Meier, N. W., & Betsch, C. (2020). Vaccination as a social contract. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, 117(26), 14890–14899. https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1919666117

- Lawn, M. (2008). An Atlantic crossing? The work of the international examination inquiry, its researchers, methods and influence (comparative histories of education). Symposium Books.

- Locke, J. (1823). Two treatises on civil government. George Routledge and Sons.

- Madaus, G. F. (1988). The influence of testing on the curriculum. In L. N. Tanner (Ed.), Critical issues in curriculum (pp. 83–121). The National Society for the Study of Education.

- Meadows, M., Baird, J., Gray, L., Cadwallader, S., Godfrey-Faussett, T., Saville, L., Debnam, C., & Stobart, G. (2023). Standards in GCSEs in Wales: Approaches to defining standards. OUCEA/23/1. https://www.education.ox.ac.uk/research/research-on-standards-in-gcses-in-wales/

- Muir, K. (2022). Putting learners at the centre: Towards a future vision for Scottish education. Report to Scottish ministers. https://www.gov.scot/publications/putting-learners-centre-towards-future-vision-scottish-education/

- Newton, P. E. (1997). Examining standards over time. Research Papers in Education, 12(3), 227–247. https://doi.org/10.1080/0267152970120302

- Newton, P. E. (2005). Examination standards and the limits of linking. Assessment in Education Principles, Policy & Practice, 12(2), 105–123. https://doi.org/10.1080/09695940500143795

- Newton, P. E. (2010). Contrasting conceptions of comparability. Research Papers in Education, 25(3), 285–292. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2010.498144

- Newton, P. E. (2011). A level pass rates and the enduring myth of norm-referencing. Research Matters, 20–26. Special Issue 2: Comparability, https://doi.org/10.17863/CAM.100441

- Newton, P. E. (2022). Demythologising a level exam standards. Research Papers in Education, 37(6), 875–906. https://doi.org/10.1080/02671522.2020.1870543

- Nind, M. (2021). What is participatory research?. [Video]. SAGE Research Methods. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412995528

- OECD. (2021). Scotland’s curriculum for excellence: Into the future, implementing education policies. OECD Publishing.

- OECD. (2023). PISA 2022 results (volume I): The state of learning and equity in education, PISA. OECD Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1787/53f23881-en

- Ofqual. (2017). Summer 2017 GCSE, AS and A level awards: a summary of our monitoring. Retrieved from https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/639880/Summer_2017_monitoring_summary.pdf.

- O’Neill, O. (2002). A question of trust: The BBC reith lectures. Cambridge University Press.

- O’Neill, O. (2013). Intelligent accountability in education. Oxford Review of Education, 39(1), 4–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2013.764761

- Opposs, D. B., Chankseliani, J., Stobart, M., Kaushik, G., McManus, A., Johnson, D., & Johnson, D. (2020). Governance structure and standard setting in educational assessment. Assessment in Education Principles, Policy & Practice, 27(2), 192–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2020.1730766

- Ozga, J., Baird, J., Saville, L., Arnott, M., & Hell, N. (2023). Knowledge, expertise and policy in the examinations crisis in England. Oxford Review of Education, 49(6), 713–731. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2022.2158071

- Popham, W. J., & Husek, T. R. (1969). IMPLICATIONS of CRITERION-REFERENCED MEASUREMENT 1,2. Journal of Educational Measurement, 6(1), 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-3984.1969.tb00654.x

- Priestley, M., Shapira, M., Priestley, A., Ritchie, M., & Barnett, C. (2020). Rapid review of national qualifications experience 2020 [ Report]. https://www.gov.scot/publications/rapid-review-national-qualifications-experience-2020/

- Reason, P., & Bradbury, H. (2008). The SAGE handbook of action research. SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Scottish Council of Independent Schools. (2022). Annual census. https://www.scis.org.uk/facts-and-figures/#:~:text=Annual%20Census&text=SCIS%20uses%20the%20information%20collected,4.2%25%20of%20pupils%20in%20Scotland

- Senthil, K., Russell, E., & Lantos, H. (2015). Preserving the social contract of HealthCare-A call to action. American Journal of Public Health, 105(12), 2404. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2015.302898

- Shafik, M. (2021). What we owe each other: A new social contract for a better society. Princeton University Press. https://doi.org/10.1515/9780691220277

- Sobhy, H. (2021). The lived social contract in schools: From protection to the production of hegemony. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences Elsevier BV, 137. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2020.104986

- SQA. (2018). Guide to Scottish vocational qualifications (SVQs). https://www.sqa.org.uk/sqa/files_ccc/GuideToSVQs.pdf

- SQA. (2020a). 2020 alternative certification Model: Equality impact assessment. Retrieved April, 2022 from https://www.sqa.org.uk/sqa/files_ccc/2020-sqa-alternative-certification-model-equality-impact-assessment.pdf

- SQA. (2020b). SQA chief examining Officer’s 2020 National qualifications and awards results report. https://www.sqa.org.uk/sqa/files_ccc/SQAChiefExaminingOfficer2020NQReport.pdf

- SQA. (2021a). National qualifications 2021 alternative certification Model (ACM): Methodology report. https://www.sqa.org.uk/sqa/files_ccc/SQAAwardingMethodology2021Report.pdf

- SQA. (2021b). SQA information for OECD independent review of qualifications and assessment. https://www.sqa.org.uk/sqa/files_ccc/20210312-sqa-information-for-oecd.pdf

- SQA. (2022a). Approaches to certification in Scotland and other jurisdictions. Retrieved November, 2023 from https://www.sqa.org.uk/sqa/files_ccc/acm-evaluation-approaches-certification-covid-19.pdf

- SQA. (2022b). Experiences of the 2021 alternative certification Model (ACM). Retrieved November, 2023 from https://www.sqa.org.uk/sqa/files_ccc/acm-evaluation-experiences-2021-acm.pdf

- SQA. (2023). Evaluation of the 2022 approach to the assessment of graded national courses: Learner and practitioner experiences. Retrieved November, 2023 from https://www.sqa.org.uk/sqa/files_ccc/learner-practitioner-experiences-main-report.pdf

- Stobart, G. (2021). Upper-secondary education student assessment in Scotland: A comparative perspective. OECD education working papers 253. https://www.oecd-ilibrary.org/education/upper-secondary-education-student-assessment-in-scotland_d8785ddf-en

- Tashakkori, A., & Teddlie, C. (1998). Mixed methodology: Combining qualitiative and quantitative approaches. Sage.

- UNESCO. (2020, 11). COVID-19. A glance of national coping strategies on high-stakes examinations and assessments. Working Document. https://en.unesco.org/sites/default/files/unesco_review_of_high-stakes_exams_and_assessments_during_covid-19_en.pdf

- UNESCO. (2021). Reimagining our futures together. A new social contract for education. International commission on the futures of education. https://doi.org/10.54675/ASRB4722

- Wiliam, D. (1996). Meanings and consequences in standard setting. Assessment in Education, 3(3), 287–307. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594960030303