ABSTRACT

This paper reports on an international collaborative project working with deaf learners of English literacy (19–28 years old) in five locations in India: Indore; Vadadora; Comibatore; Pattambi; and Thrissur. Indian Sign Language (ISL) was the language of instruction. The project drew on a social practices view of literacy. Deaf peer tutors were trained in creating lessons using authentic materials: texts collected from students’ everyday lives. Tutors and students shared content via an online teaching resource. In the paper, the authors draw on notes from the training, tutor and student data, to clarify the strengths and challenges of this approach. Real literacies were used fruitfully, but authentic texts could be complex and grammar lessons were often unrelated to these texts. This challenged our assumptions about the applicability of the real literacies concept to pedagogy. Nevertheless, the study confirms the value of an approach that privileges ISL, peer tuition and online materials.

Introduction

India has one of the largest deaf communities in the world: about 63 million people, 6.3% of the population in India, have ‘significant auditory loss’ (Naik, Mahendra, and Sharma Citation2013, 1). Access to education for deaf children, however, is limited: there is a shortage of specialised schools for deaf people and teachers trained in ISL (Naik, Mahendra, and Sharma Citation2013; Gillen et al. Citation2016a). While the use of ISL has been recognised as crucial for the educational advancement of deaf students (Rehabilitation Council of India Citation2011), English literacy is also increasingly needed not only for education, but to access employment and for lifelong learning. As digital technologies are widely used, by deaf and hearing people, and provide access to a broad range of knowledge, information and entertainment, access to English is desirable for reasons beyond education and employment.

This paper discusses findings from an international collaborative project that developed an innovative approach to English literacy education for young deaf people in India. The project was entitled ‘Literacy Development with Deaf Communities using Sign Language, Peer Tuition and Learner-Generated Online Content: Sustainable Education Innovation’ (henceforth ‘Peer2Peer deaf literacy’ or ‘Peer2Peer project’).Footnote1 The main aim of the project was to develop and implement a peer led English literacy programme for young deaf people in India, Ghana and Uganda. The project team included academics working in the UK, amongst these the authors of this paper, an Indian researcher of sign language and deaf education, and a group of deaf research assistants and peer tutors in India, Ghana and Uganda.Footnote2

In this paper, we examine the approach to curriculum and materials development that we adopted in this project, which implemented a ‘real literacies’ pedagogy rooted in the theory of literacy as a social practice. We drew on ethnographic methods to create a learner-centred curriculum using ‘real’ or ‘authentic texts’ (Hewagodage and O’Neill Citation2010) (e.g. a shopping receipt) and ‘real life’ uses of English, taught through a deaf-led method, which aimed to value students’ everyday literacy practices and use them as the basis for language teaching. We ask how and to what extent this focus on ‘real literacies’, an idea that was brought to the project by its UK based collaborators, was taken up by the learners, tutors and research assistants in India. We identify both the value and the challenges of adopting this social approach to literacy and deaf education. Our paper sits at the intersection between theory and educational practice. The contribution we make is that we probe into the relevance of a specific understanding of literacy for teaching and learning, specifically with regards to curricula. Put differently, we contribute to the development of a pedagogy based on a social practices model of literacy. Specifically, we offer new insights into the underlying assumptions of a ‘real literacies’ approach.

The Peer2Peer project

The Peer2Peer project ran from June 2015 to June 2016. The aim of the project was to design, implement and evaluate an English literacy programme for young deaf people in India. Additional scoping research around English literacy education for deaf people was done in Ghana and Uganda, but we do not comment on this part of the project here (Gillen et al. Citationforthcoming).

The project had four distinctive features. Firstly, it used Indian Sign Language as the medium of communication between tutors and learners. A working proficiency in ISL was one of the criteria for recruiting students to the programme. Secondly, peer tutors from the deaf community, trained at the beginning of the project, led the sessions with deaf learners, thereby promoting a deaf-led approach which allows people from within the community to develop their abilities as tutors and to support others (Gillen et al. Citation2016b). Thirdly, the curriculum was developed on the basis of learners’ ‘real life’ uses and needs for English literacy (see later in this article). And, finally, face-to-face learning in class was combined with the use of multimedia online learning materials, created by the groups of learners themselves as part of their classroom activities, building up a bank of shared materials over the course of the year.

Teaching interventions were implemented in collaboration with five non-governmental organisation (NGO) partnersFootnote3 located in Indore, Vadadora, Comibatore, Pattambi and Thrissur, with 43 deaf learners, the majority in their early 20s, attending lessons from September 2015 until March 2016. Most of our students had attended high school up to year 10 or 12 and many were pursuing or had obtained an undergraduate degree. Of the 43 students, 17 were female. The project employed three deaf research assistants (RAs) and five deaf peer tutors (PTs) in India, all of whom had BA degrees, most of them in applied sign language studies. The fact that all tutors and research assistants were deaf was a deliberate choice, in line with the project’s wider aim to develop teaching and research capacity amongst deaf people (the importance of which is highlighted, for instance, by Kusters et al. [Citation2017]).

Two-hourly lessons in class took place every weekday morning. In the afternoons, students could use each site’s computer facilities to work independently with the project’s online learning platform. This was a Moodle-hosted interactive online learning environment developed by e-learning specialists in the UK (called ‘Sign Language to English by the Deaf’, SLEND). The Peer2Peer project’s aim was to carefully research how, in the five sites in India, the suggested approach was taken up. The project’s long term goal was to further develop the approach, so that it could be used in India and beyond, and to contribute to the development of inclusive and flexible ways to support English literacy education for young deaf people in different circumstances.

The project team gathered a variety of data, both quantitative and qualitative. This included pre-, post- and delayed post-English tests, as well as statistics tracking engagement in the project’s online learning platform over time. In this paper, we rely primarily on the qualitative data. This includes one of the author’s observation notes and photographs from the initial training, videos of parts of the training, tutors’ weekly reports of their teaching, classroom observations by RAs, teaching materials used for the training, and materials developed and used by the five classes available via the SLEND. We also draw on focus groups with all the learners, held at the end of the project, to allow the students to share their experiences of the lessons.

In the following sections, we first introduce the theoretical approach the Peer2Peer project draws on and highlight relevant prior research that has informed our work. This is followed by a brief description of the initial training of peer tutors and research assistants, carried out in India in 2015. We then offer examples of teaching materials and lessons from the classes and discuss these in light of how the approach introduced during the training was taken up by the tutors and learners and what insights this offers for research (and practice) in education for young deaf people.

‘Real literacies’ and an ethnographic approach to curriculum development

The Peer2Peer project started from the assumption that for deaf students to improve their ability to use English literacy, the lessons had to build on their existing literacy practices and their prior knowledge and life experiences. Accordingly, the project was designed to document how deaf people use English literacy in their daily lives and for what purposes they would aim to improve their literacy. These insights were then to inform the choice of learning materials and the content of lessons. The methodology for designing curricula and lessons in this way is grounded in an understanding of literacy as social practice.

The social practices concept of literacy is a well-established theory, providing the basis for ethnographic-style research into the uses and meanings of literacy in everyday life, institutional and work-related contexts (Street Citation1993; Prinsloo and Breier Citation1996; Barton and Hamilton Citation2012). A social practices view of literacy understands reading and writing not primarily as measurable skills, but as purposeful activities embedded in social practices and informed by both personal and more widely shared meanings and values. This understanding of literacy has become known as New Literacy Studies (NLS) (Gee Citation2011).

While the NLS originally derived from an interest in understanding the uses and meaning of reading and writing (i.e. ‘literacy practices’) in everyday contexts (Street Citation1993), researchers in this area have always been interested in questions of learning and teaching. A social practices approach to literacy recognises that reading and writing are learned in many contexts and in informal ways, through participation in literacy practices (Barton and Hamilton Citation2012; Papen Citation2012). This means that people acquire literacy-related abilities outside their participation in formal education. While these may not be easily measurable, it is important for any learning intervention to begin with what the learners know and do already (Street, Baker, and Rogers Citation2006).

Literacy education that is inspired by an NLS perspective seeks to avoid a deficit approach, that is, an approach focusing on what people cannot do. In the Peer2Peer project, we started from the position that all the learners bring with them to the classes experiences of using English in their everyday lives. To be able to develop meaningful curricula and lessons for these young deaf people, we therefore had to understand what they were already doing with English literacy. This is what we mean when we refer to real literacies (Rogers Citation1999): the literacy practices our learners were engaging with in daily life. Included in these are vernacular practices which would not be recognised by standardised assessments (Corbett Citation2015). For example, the young deaf people in the Peer2Peer project, tutors and students, were regular users of written English, but the English they used, often on social media, had its own distinctive features (influenced by ISL). It could be described as non-standard, characterised, for instance, by telegraphic phrases, inconsistent grammatical agreement between subject and verb, abbreviations like ‘n’ for ‘and’, and very frequent use of images and videos integrated with written communication.

The Peer2Peer project’s approach to curriculum development was also inspired by the LETTER – ‘Learning for Empowerment Through Training in Ethnographic-style Research’ – project first developed in India in 2001 (Street, Baker, and Rogers Citation2006; Street Citation2012; Nirantar Citation2007). Bringing together NLS theory with the concept of ‘real literacies’ (Rogers Citation1999), LETTER is based on the idea that ethnographic-style research can be used by non-academics to investigate the literacy practices of learner communities. In LETTER projects, adult literacy trainers and coordinators are introduced to principles of ethnography, which they then use to research the literacy practices of learners in their communities. Based on these findings they develop curricula and learning materials. In the Peer2Peer project we followed a similar approach, but included the learners themselves in researching their own literacy practices, inviting them to bring these to the classes to form the basis for new learning. More broadly, our approach is informed by research on sociocultural approaches to teaching English as a second language which emphasise learning from real life communicative experiences, including using authentic texts rather than set textbooks (Hewagodage and O’Neill Citation2010).

There is little published research on deaf education programmes for young adults, in particular young adults who live outside Europe and North America, and whose situation is comparable to the students in our project. There are, however, similarities between our approach to curriculum development and initiatives that have sought to create new ways to link (hearing) students’ ‘out-of-school literacies’ (Dickie Citation2011; Smith and Moore Citation2012) with school curricula. Much of this research addresses the situation of adolescents – in countries such as the US, Canada or Australia – who are alienated from school and whose literacy practices may not be valued by formal literacy assessments. Like the P2P approach, studies of out-of-school literacies seek to bring young people’s everyday literacy practices, their adolescent literacies (Elkins and Luke Citation1999), into education. Some of these studies explicitly consider the context of young people who are bilingual and/or who come from disadvantaged or marginal backgrounds (Stewart Citation2014; Pyo Citation2016), but there appears to be no overlap between this area of research and the field of deaf education. Nevertheless, we share with this body of research a desire to examine how a social practices perspective on literacy, with its focus on students’ everyday literacy practices, can be drawn on to develop ways of teaching and learning that make lessons relevant to students, build on what they know already and also allow them to acquire skills they need (cf. Bailey [Citation2009]).

Research on deaf education tends to focus on younger children, who, unlike the young people in our project, are still learning to read and write (see, for example, Mayer and Leigh [Citation2010]; Swanwick [Citation2016]). These studies debate the advantages and limitations of sign bilingual education, an approach that has some similarities with our work (i.e. in the use of a sign language), but which also includes speech and hearing as modes of communication and ways of accessing literacy, supported by the use of assistive technologies such as cochlear implants and hearing aids. There is, however, a point of connection between this research and our own. The development by researchers of deaf education of a social model of deafness (Swanwick Citation2010), which values sign languages and the communicative competencies and preferences of deaf people, resonates with a social practice perspective on literacies which values the existing practices people draw on to communicate rather than positioning them as being deficient.

A collaborative action research project

The Peer2Peer project sought to empower deaf people and to create opportunities for members of the deaf community to develop their skills and expertise. The training our tutors received (see later in this article) was designed to introduce them to the idea of working with others as facilitators of learning, not as instructors. That is to say, the aim of the classes was for tutors and students to work together pooling their understanding, with the assumption that everyone in the classroom has valuable knowledge, rather than positioning the tutor as the sole source of expertise. Thus, collaboration in our project operated at various levels, beginning with the lessons themselves, which tutors and students developed together.

At a second level, the India-based research assistants collaborated with each other and with the five tutors to help with curriculum and materials development and use of the SLEND. The research assistants were able to travel to the classes and they received support from the wider team, including the UK-based partners. Tutors, students and research assistants maintained regular contact using WhatsApp groups.

A third level of collaboration involved the international partners, based in England for most periods of the project. We came to define our role as ‘gap fillers’ (Zeshan, personal communication). We meant by this that we had specific expertise in research design, data analysis, and the real literacies approach which we brought in as and when required, but the overall development of the project was driven by the deaf researchers and peer tutors, in a collaborative or participatory approach (Chevalier Citation2013). Once classes were operating, we supported tutors primarily via the RAs who were in regular contact with the Indian-based Co-I. Our other role was to oversee the data collection, both the quantitative and qualitative elements.

Research ethics were an integral part of our collaborative approach. The project obtained ethics approval from the two UK universities involved in it. All participants, including the students, were briefed in detail (using written information sheets and consent forms as well as video-recorded explanations in ISL and via personal communication) about the data we wanted to collect, their role in it and what would be done with this data. This included discussing the question of anonymity with participants. Because the project used ISL videos, full anonymity is not possible, and all participants agreed to this.

The training

In June 2015, the five peer tutors, three Indian research assistants and two research assistants from Ghana and Uganda attended a two-week intensive training course. The training was held at NISH (National Institute of Speech and Hearing), one of our project partners, in Thiruvananthapuram (Trivandrum), Kerala. The main purpose of the training was to introduce tutors and research assistants to the ethnographic approach to curriculum and materials development and to the peer-to-peer teaching methodology. The first week of the training focused on introducing tutors and RAs to the idea of literacy as social practice and, concomitantly, the ethnographic approach to investigating real literacies and creating lessons. This part of the training was delivered by one of the co-authors together with the project leader (PI) and the India-based Co-I. In the following, we describe the main features of the training, from the perspective of the co-author who delivered it. The account we present here is based on her fieldnotes as well as on the training materials we used.

The training was delivered over five days through a combination of lecture-style inputs, group discussions and practical exercises. These exercises included work in class as well as the trainees walking through the city, visiting the railway station and shopping malls, taking photographs of signs and collecting real texts. A key component of the training consisted of jointly analysing these texts and creating grammar and vocabulary exercises around them. The working languages of the training were English and Indian Sign Language; an ISL interpreter worked with us throughout.

During the first two days of the training, I introduced two key ideas: literacy as an activity or practice; and real literacies or literacies as used in everyday life. The aim was to share my understanding of literacy not as abstract skills but as something people do, as activities that people take part in every day (Barton and Hamilton Citation2012). I focused this introduction on the role of English literacy in the trainees’ lives. For example, I showed them photographs of signs in Trivandrum, explaining how these could be used to teach vocabulary or grammar. A sign, saying ‘Building for Rent’, I suggested, could be the starting point for discussing the use of prepositions in English. I also shared examples from my own research (e.g. an invoice from a furniture store; see Papen Citation2012) and explained that reading signs in the streets, consulting rail timetables or completing forms are literacy practices.

From the beginning of the training, I emphasised that the young people the trainees were to work with are already regularly engaging in English literacy practices. The focus of the teaching was to identify such everyday literacy practices and to use these as the basis for lessons, teaching new vocabulary and grammar, but at the same time supporting the students’ ability to engage with these practices. In line with our peer-to-peer approach, tutors and students together were to engage in the search for relevant texts and in the creation of exercises and lesson activities. Unlike in the LETTER project, where ethnographic research and curriculum development took place before teaching started, in the P2P project, the research was to be part of the lessons and the curriculum was to be co-created and evolving. Texts and materials would be shared among the five groups of learners using the SLEND.

On the second day, I introduced the trainees to the idea that in our project students and tutors would become researchers, researching students’ needs and interests to make lessons meaningful to them and to start ‘where the learners are’ (Street Citation2012). Research, I explained, is a process of searching for and looking closely. I introduced ethnography as a type of research carried out in ‘real’ life, where people live and do things that involve reading and writing. The evening before, during a walk through the neighbourhood, I took photos of the signs filling the streets. They were in several languages, with English prominent among them. The next morning, I shared these images with the trainees. I used a photo of a signboard advertising electrical goods repairs to show that a text like this could form the basis both for introducing new vocabulary, and to teach grammar, using the phrase ‘We are servicing …’ to teach the present continuous.

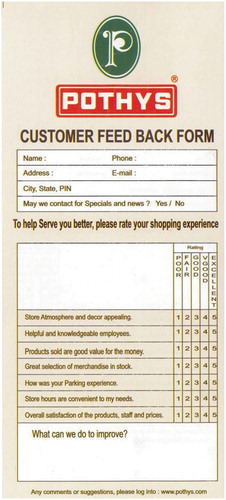

In the afternoon, we sent the trainees out to be ethnographers of literacy themselves. In small groups, they went into the centre of Trivandrum, equipped with their mobile phones, tasked with finding ‘real’ texts in English. They found advertising signs, food bills and many official notices and posters, for example around the railway station. The next day we looked at these examples, thinking about how we could use these to create lessons. One example is the customer feedback form in . (Pothys is a large company, with shops across Southern India, selling sarees, kurtas and other clothing.)

The trainees worked in groups to discuss this form. A crucial part of our discussion was to think about how new words could best be explained in ISL. The trainees developed a lesson plan on the basis of the form, including first visiting the shop, then completing the customer feedback form in groups and sharing their responses, explaining the meaning of difficult vocabulary such as ‘appealing’ and ‘merchandise’, video-recording explanations of this new vocabulary and uploading these explanations to the SLEND.

On days four and five we looked at digital literacy practices and the trainees were introduced to the SLEND, our online learning platform. The trainees worked in groups to identify their own digital literacies, listing the hardware they had access to and writing down the digital practices they engaged in regularly. Together, we created a list of these practices and displayed them on the lab’s big screen. The idea was to develop lessons based on the digital literacy practices students engage in already. As an example, our list included the item ‘sending videos of jokes to friends using WhatsApp’. The trainees explained that they used WhatsApp a lot for this purpose and that they expected their students to do so too. One of them suggested a lesson based on this, where the students would bring in and show videos of jokes they had shared with their friends, and then write the jokes in English. The trainees felt this short, fun writing exercise might be accessible to students who were likely to find more extended writing tasks challenging. In these sessions, the trainees also learned how to shoot short videos explaining English words and how to upload these to the SLEND.

Peer-to-peer teaching: examples of lessons and students’ reactions to the real literacies approach

The five groups began their lessons in September 2015. Students sat a pre-test, developed by the research team and adapted from the CEFR (Common European Framework of Reference for Languages). At the end of the five months, all students took a post-test. The results of the assessment are discussed in more detail elsewhere (Zeshan et al. Citation2016), but comparing pre- and post-tests reveals that significant gains were evident in the students’ scores, indicating that substantial learning had taken place. Student responses in the focus groups that we ran at the end of the teaching corroborate this. Many students spoke about skills gained and commented on their growing ease in dealing with everyday contexts such as following directions at a railway station or understanding the information displayed inside the station.

Below, we discuss examples of lesson activities from the five classes. The aim is to examine how the students and tutors engaged with our approach – the focus on everyday English and real literacies – and what challenges it posed for them. The data we use here includes the tutors’ weekly reports, complemented by the RAs’ observation reports, material from the SLEND and transcripts (translated by the research assistants) of the student focus groups. The research assistants visited all classes twice throughout the duration of the project, in September 2015 and April 2016. They supported the peer tutors throughout the teaching period remotely, mostly via WhatsApp, and the transcripts of these conversations are part of our data. All this data was regularly transferred to the team in the UK.

A small subgroup of the research team, led by the second author, coded the weekly tutor reports, RA reports, focus group and WhatsApp transcripts using the software ATLAS.ti. Documents were uploaded to a shared ATLAS.ti hermeneutic unit and assigned to individuals for coding each month. We began with a simple coding scheme reflecting the research aims of the project, with overarching codes for ‘Activities’ (a code that we used to identify different kinds of lesson activities); ‘Evaluation from Tutors’; ‘Problems’; ‘StudentResponses’; ‘ToolsClassroom’; ‘TutorExperiences’; and ‘RealLifeUses English’. Sub-codes for each of these sections were then generated in response to the data, for instance, sub-codes labelling each activity (‘Discussion’, ‘Exercises’), each tool used (‘Whiteboard’, ‘Projector’) and so on. We used the ‘comment’ function on ATLAS.ti to clarify meanings of different codes. The coding process was kept under discussion, both by email and during the regular project meetings, to ensure that different coders used codes in similar ways and to address any ambiguities. Each time the unit was updated – on a monthly basis – all coders could see each others’ coding. As the research continued and the use of the SLEND in the classroom increased, we added new codes. These included ‘Comments on the SLEND’; ‘Direction’ (of tutors by research associates, particularly through regular discussions on WhatsApp); ‘Pedagogic Philosophy’; ‘Sign Language’; ‘SLEND Activities’; and ‘Suggestions for SLEND’, finishing with a complex structure of 487 codes allowing us to map in detail the content of the data.

Of all the data coded, the weekly tutor reports in particular offer crucial insights into the lessons and thus allow us to compare what we had suggested in the training with how lessons were conducted. The tutor report form covered ‘topics’, ‘activities’, ‘self-assessment of peer tutors’ and ‘feedback from students’. In their reports, the tutors included photographs of the real texts they had used.

Each week, the tutors reported on what students enjoyed and how they felt about progress with their English. We coded all these instances, in the tutor reports and the student focus groups, under ‘StudentResponse’. The first thing to report from this is the overwhelmingly positive response overall. Of the 502 items coded under ‘StudentResponse’, 472 can be interpreted as positive responses. The most commonly used codes in this section of the data were ‘StudentResponse_Understanding’ (124 instances), ‘StudentResponse_Interest’ (97 instances), ‘StudentResponse_Enjoyment’ (94 instances), and ‘StudentResponse_Learning’ (79 instances). The next most commonly used code and the first negative one, ‘StudentResponse_LackOfUnderstanding’, was only coded for 27 times. But what did the students enjoy most, and to what extent were real texts key to the students’ enjoyment?

To answer these questions, we looked at the codes that co-occurred with the 472 instances of students’ positive responses. The first finding here is that highest on the list were the codes ‘Activities_GroupDiscussion’, co-occurring with positive responses 37 times; ‘Activities_PeerTutorExplaining’, co-occurring with positive responses 28 times; and ‘SignLanguage’, co-occurring with positive responses 27 times. These data support our argument about the value of the peer approach and suggest that students enjoyed being actively involved in lessons and using ISL to engage in discussions and to help them understand the English texts that they worked with. While teaching ISL was not an aim of the lessons, students liked that it was the medium of instruction and they reported making incidental improvements in their ISL, learning new signs.

The activities that the students liked frequently used real life English materials. Of 170 total instances of ‘Activities_GroupDiscussion’, 60, i.e. over one-third, co-occurred with one of the ‘Uses’ codes representing real life English. ‘Activities_PeerTutorExplaining’ was coded 169 times overall; forty of these occasions co-occurred with one of the ‘Uses’ codes. The quite frequent co-occurrence of group discussions and tutor explanations with uses of English in real life indicates that, as we had envisaged, a fair amount of curriculum time was spent on tutors and students together working with real texts.

The tutors’ weekly reports show that they used a variety of real life materials. These reports also indicate that while each of the five groups developed their own programme of learning, there was overlap between them. While there was little material available on the SLEND in the initial weeks of teaching, as each group began to work with real texts, they uploaded these materials to the SLEND (including filmed explanations of English words and exercises produced by the group). These were then available on the SLEND for the other groups to use.

Probing further into the place of real literacies in the teaching, the code ‘Uses of Language’ allowed us to identify many everyday life materials used in the lessons. ‘NoticeboardsAndSigns’ was mentioned 62 times. ‘Railtravel’ (33), ‘ApplicationForms’ (24), ‘BankingRelated’ (24), ‘News’ (20) and ‘WeightsAndMeasures’ (15) were also common. ‘SchoolOrCollege’ items were second most common (34) but some of these were ‘real life’ school items such as noticeboards located around the school rather than pedagogic texts. Other items mentioned here were ‘IdentityCards’, ‘SickLeave’ and ‘Sports’ (cricket and swimming). We can see from this analysis that the classes did indeed draw extensively on real life materials, as we had hoped.

However, our data also shows many grammar activities, and students commenting positively on these. After group discussion and peer tutor explanations, the next most common ‘Activities’ code co-occurring with positive student responses was ‘Grammar’ (20 co-occurrences). ‘ExplainingGrammar’ (15 co-occurrences) and ‘GrammarExercises’ (12 co-occurrences) also came high on the list of activities co-occurring with positive responses. Students tended to like grammar being part of their lessons. There is a need then to look in more detail at what topics were covered and what role real life English played in relation to grammar. As explained earlier, in the training we had suggested that authentic texts should inform what grammar to teach. Grammar lessons were to be ‘embedded’, helping students to develop grammar needed to function in everyday life and to avoid teaching about grammar independent of its use in real contexts of communication. Our data show that this was not always achieved. When looking at the data under ‘Activities’, codes indicating grammar work were very frequent. Seventy-five different activities were identified by the coding. While the two most common were ‘group discussion’ and ‘peer tutor explaining’, of the following eight most frequent activities, four were about grammar – explaining grammar, learning grammar, grammar exercises and simply grammarFootnote4 – indicating that grammar lessons took place frequently.

Looking at which codes co-occurred with grammar produced an important finding: less than 10% of the activities coded ‘grammar’ co-occurred with the ‘uses’ codes. These included ‘noticeboards and signs’, ‘invoice’ and ‘banking related’. This suggests that contrary to our expectations, grammar teaching was not always embedded in the discussion of real life uses of English. One tutor report (September 2015) illustrates this. The class worked with an ATM customer advice slip. This was in response to two students’ interest in this type of text. So here, the lesson followed the approach that we had introduced in the training: students identifying real literacies and bringing them to class, where together with the tutor they develop a lesson around these. However, the tutor report also mentions a second topic: an exercise about tenses. The added comment by the tutor is important: the students wanted to learn more grammar. Looking at the ATM receipt, there is no obvious way in which discussing this text could have led to the students being interested in past or future tense. The tutor attached a copy of a table showing three verbs and their present, past and future forms to show the materials drawn on in the lesson. Another tutor (October 2015) explains that an invoice for an internet connection had ‘complex sentences’ and did not ‘match [their] grammar level’, making it hard for her to find other ‘topics’ related to this bill. She came up with the idea of teaching students about ‘to be’, which, she added, the students enjoyed.

While the above examples reveal the difficulties and ambivalences around teaching grammar using real texts, other data illustrate that materials could indeed lead to a need for a specific aspect of grammar to be explained, as we had practised in the training. An example is a lesson based on a street sign saying ‘Parking at Owner’s Risk’ (). The tutor reports the students asking him about the apostrophe, so he used this sign for a lesson about possessives. After the class had looked at the signboard together and discussed its meaning, the tutor explained the rules for using the apostrophe and asked students to complete a grammar exercise on apostrophes at home.

Another example from a tutor report (October 2015) shows the students working with a bank deposit slip. According to the tutor, they discussed the slip and how to complete it, focusing on any words the students did not know. This matches what many other reports show: using real texts, collected by the students or the teacher, offered many opportunities to develop the students’ vocabulary and a lot of class time was spent talking about the text and its meaning and use (see also Hewagodage and O’Neill [Citation2010]). There were challenges though, as indicated by the tutor’s comments on this lesson: she found it difficult to explain ‘complex words’ and ‘sentences which match real life topics’. Commenting on the students’ responses to the lesson, she added that they were bored ‘with new words again because they do not like them’.

The fact that authentic texts can prove to be difficult teaching material is also indicated by the tutor in Kerala who reports spending an entire week working with an e-ticket for railway travel. In groups, students looked for unfamiliar words on the ticket as well as for any grammatical elements they did not understand. Students’ responses to this topic were mixed. The tutor reports that students were interested in the topic but were ‘bored’ with the many new words. He adds that the students struggled to find the meanings for specific words online. Particularly difficult were the ‘Terms and Conditions’ at the bottom of the ticket.

Other tutor reports indicate that students requested specific topics, different from the kinds of mostly practical topics suggested at the training. One group for example worked with a map of India and a map of the world. They uploaded this lesson to the SLEND and it was used by the other groups. It included vocabulary such as ‘country’ and ‘state’. The related exercise included learning about countries across the world. However, the lesson also covered the pronouns ‘his’ and ‘her’, which were not directly related to the map. This lesson is another indication of the learners’ strong interest in grammar and the use of decontextualised grammar activities in the lessons. The tutor reports and the material uploaded to the SLEND indicate that it was quite rare to see explicit connections between the grammar being taught in class and the real texts which were drawn on.

Discussion: real literacies in literacy education for young deaf people

Looking at the examples of lessons and materials discussed in the previous section, a number of issues emerge that reveal differences between what we had envisaged and how lessons were conducted. These differences point to the challenges the chosen approach posed for tutors and students, but also invite us to raise questions about the theory of literacy we drew on.

As highlighted earlier, the students found that the focus on real texts supported their learning. In the focus group discussions at the end of the project, several students commented on notices and other texts that they could now understand.

Looking at the examples of real literacies introduced in the training and comparing these with the topics that were covered in the five classes, a difference between the text genres that dominated the training and the types of materials used in the classes is noticeable. What we had used during the training certainly influenced the tutors’ and students’ choices in the initial weeks of the classes. The SLEND shows texts such as signboards, invoices, application forms and railway tickets, similar to the examples used in the training. But they also worked on topics that had not been mentioned in the training. They learned about the states of India, looked at crosswords, and talked about food and drink, hobbies, politics and religion. The real literacies we had chosen for the training tended to be of a practical nature, dealing with things that need to be done rather than those one might want to do or would enjoy. In other words, there was a lot of ‘useful literacy’ in our design and this is similar to the materials used in the LETTER project. This may explain why there were aspects of some of the lessons that the students did not enjoy. Another issue was the complexity and length of some of these real texts, such as the e-ticket, that included much small print, not all of which a traveller needs to read to buy a ticket. The students’ interest in getting to grips with such long texts was, understandably, limited. This was reiterated by one of the students’ comments at the focus groups: the SLEND included many texts of similar kinds, relating to travelling by train and bus or banking. These, she said, over time ‘got boring’. Another student, in the same focus group, explained that the sentences in these texts were very ‘advanced’ so she found these difficult to understand and her learning was ‘slow’.

So, probing further into the question of real literacies as a basis for the curriculum, it seems that we had inadvertently disregarded leisure and interests beyond practical topics. This is likely to have happened because the project had been intended to support young deaf people in coping with the literacy demands of everyday life. Accordingly, in the training Papen focused on practical topics and she paid less attention to wider aspects of the students’ lives.

The peer-led approach and evolving curriculum had been intended to give students the flexibility to bring into the lessons any topics they wanted to learn about. To a certain extent, this is what happened and in that sense the collaborative approach we had designed was a success. Although real texts of a functional nature had a prominent place in the lessons, the students brought in their own ideas and made it clear when they did not like the examples on the SLEND which were all about similar genres and practices. This suggests that pedagogical approaches drawing on ‘real’ literacies need to ensure that such literacies are conceptualised more broadly, and should include activities related to leisure, personal interests or any other topics students are enthusiastic about. This would be in line with the broad conceptualisation fundamental to a social practice theory of literacy, which understands reading and writing in terms of ‘social’ uses and meanings, not just practical tasks. One example is sport, mentioned by the trainees when they discussed their own digital literacy practices.

It is important to try to understand why de-contextualised grammar exercises played an important role in the lessons, despite their absence from our initial plans. Based on the training and the communications we had with tutors and research assistants throughout the project, we know that to create grammar lessons linked to real life topics was difficult and that the tutors could not always find appropriate materials. Tutors involved the students in collecting real texts, but then they, the tutors, had to create adjunct materials and lesson activities around these. Most of the grammar exercises included in the tutor reports appear to have been found on the internet. Informal discussions during the training and in WhatsApp conversations also indicated that tutors and students believed that knowledge of grammar was essential for improving their English. Our attempts to avoid a deficit perspective were met with the tutors’ and students’ belief that their grammar knowledge was lacking and that they would benefit from explicit grammar teaching. In the second half of the period in which classes were running, the RAs and tutors in India asked us, UK-based project members, to help with the development of grammar exercises in relation to real texts. While we had practised this in the training, there is no doubt that this was a complex task.

The above suggests that the collaborative approach had both advantages and disadvantages. At the training, the voices of the academics in the project were strongest, with Papen for example being positioned as the ‘expert’ on real literacies. This echoes the experiences of other academics engaging in collaborative action research (Call-Cummings Citation2016). The tutors’ reports from the initial months of teaching show that the texts they used were of the same type as those in the training. But tutors and learners made it clear when real texts were not appealing or when they wanted to learn about other things. This was empowering for the peer tutors and students, and so provided significant opportunities for the project team to learn and to reconsider some of our assumptions and expectations. The young learners and tutors in the Peer2Peer project invited us to rethink what ‘real literacies’ are about. They brought to the programme aspects of deaf and youth culture that we, the hearing academics, were not familiar with. At the same time, though, it is important to acknowledge that while empowering local tutors and RAs was a laudable aim, such empowerment requires communication and support involving all project partners, which, given the structure of the project, was not always feasible to the extent needed. This is an important lesson to learn, not just for us but for other collaborative initiatives. Despite these limitations, the Peer2Peer project confirms what studies on adolescent literacies (see earlier) have found too: drawing on real literacies from students’ everyday lives enables learning and makes the curriculum relevant to students’ everyday contexts.

The Peer2Peer project demonstrates the relevance of the real literacies approach for a group of learners disadvantaged in ways both similar to and distinct from other young people who have been the subject of similar research. Like other groups of young people, our learners came to the classes with relevant experiences of language and literacy, including their sign language and their knowledge of digital literacies. Affirming what students know already, bringing this into the classroom as we did, allowed us to counter the deficit approach that is prevalent in much schooling and that our learners had experienced too.

It is important, though, to avoid romanticising the experiences and knowledge our students brought to the classes. Unlike the young people in the studies from the US and other countries referred to earlier in this paper, our students’ knowledge of English was limited. For example, they knew little about grammar and their assumption that they needed better grammatical knowledge in order to be able to use English in the way they wanted had some justification. In that sense, our project was more akin to work done in Australia to support adult migrants’ English literacy (Hewagodage and O’Neill Citation2010). Both this project and ours show that, although challenging, authentic texts can be fruitfully used even with students whose English language skills are limited. However, for such a curriculum to work, it is important that the links between focusing on real life communication and more formal skills development are carefully designed. Looking at the theory that underpins the approach, this is where the biggest challenge to the social practices view of literacy arises and which was reflected in the students’ desire for grammar and the difficulties tutors experienced when using real texts.

Developing a curriculum on the basis of students’ everyday practices is challenging for the tutor, as Skerret and Bomer (Citation2011) have found, too. That the curriculum is not ‘given’ but to be developed with the students creates unpredictability and requires constant reflection and decision-making by the tutor. It is thus no surprise that some of the projects of this kind were the result of a close collaboration between academics and teachers, where the latter had regular opportunities to draw on discussions with the academics as resources for reflection and discussion. In our project, as explained earlier, this was more difficult to do.

With regards to deaf education, the Peer2Peer project illustrates a form of sign bilingual education (Swanwick Citation2016) that is suitable for learners with a good sign language competence and where the language that is taught (English literacy in our case) needs to be conceived of as a second language, sign language being the students’ first language. Our project contributes to the research base on deaf education by adding insights from an initiative that is highly inclusive, addressed to a group of learners who have not yet received much attention (but whose learning needs are without doubt) and which can be drawn on in resource-scarce contexts.

A final point to make concerns the nature of the literacy practices the young people in our study engaged with and wanted to learn more about. Looking at the examples of English used in our project it is evident that students’ everyday practices are not just multilingual (involving English, ISL and the written forms of other Indian languages), but are also multimodal and frequently digital. The most revealing illustration of this is the tutors’, RAs’ and students’ use of WhatsApp to communicate with each other beyond the lessons and across the five groups. On WhatsApp they communicated in writing (English) but also used images, videos and links to websites (that in themselves are multimodal). As Bartlett et al. (Citation2011) – referring to Latin America and the Caribbean – suggest, the role of technology in relation to young people’s literacies is crucial, even in contexts where access to that technology is limited. Such technology enables communication via a variety of modes, combined in different ways. Deaf adolescents, like hearing youth, access and make use of digital technologies. This suggests that any education programme for young deaf people should respond to the multimodal and digital nature of their communication and should thus best be conceived as multimodal not bimodal.

This study has shown, therefore, the value of a collaborative peer-to-peer pedagogy using authentic real-life materials, whilst also illuminating some of the challenges inherent in this approach and in the theory that underpins it. Systematic analysis of a rich qualitative dataset has shown that students particularly appreciated the possibility for group discussion and interaction with the tutor using sign language. Curriculum development using meaningful texts from everyday life was evident, and a rich online resource was built up based on these materials. At the same time, students’ desire for grammar tuition and the difficulty of generating grammar exercises using real texts indicates a challenge to the hoped-for application of a social practices view of literacy to this specific educational context. While other studies (Bailey Citation2009), in different contexts, have found that a social practices approach can be used to create lessons that teach more formal skills within a broader conceptualisation of literacy and related lesson activities, in our context this was challenging. Further research is required to tease out how a social practices based pedagogy can be made to work with different groups of learners and to ensure skills teaching is integrated and delivering what students need (in our case, for example, knowledge of grammar such as tenses).

In a follow-up project (which started in July 2017) we have reconceptualised our approach using the concept of multiliteracies (Cope and Kalantzis Citation2009), in line with the findings from the study reported here. This allows us to take better account of the way deaf people communicate via a variety of modes and channels. While we developed this new approach having in mind the situation of deaf people, there is no doubt that understanding literacy as multiple, multimodal and digital (ie. multiliteracies) and, concomitantly, rethinking the nature of real and social literacies is both required and valuable for the development of similar educational initiatives working with disadvantaged groups of learners.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank our funders, the ESRC and DfID, for making this project possible. Our particular thanks go to our local project partners, the students, tutors and research assistants who worked with us in the project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. We would like to thank our funders, the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and the UK Department for International Development (DfID), for supporting this project.

2. The team was made up of Ulrike Zeshan (PI), Julia Gillen, Sibaji Panda, Uta Papen, Karin Tusting and Daniel Waller (Co-Is), research assistants Deepu Manavalamamuni, Mahanmadaejaz Parasara, Tushar Viradiya, Noah Ahereza and Marco Stanley Nyarko, and peer tutors Ankit Vishwakarma, Brijesh Barot, Anu Nair, Nirav Pal, and Dagdu Jogdand.

3. The project partners were the National Institute of Speech and Hearing (NISH) in Trivandrum, Kerala; the Uganda National Association of the Deaf in Kampala; and the Lancaster University Ghana campus in Accra. The local partner institutions were Indore Deaf Bilingual Academy; Silent Global Foundation, Thrissur; Deaf Leaders Foundation, Coimbatore; National Deaf Family Care, Pattambi; Ishara Foundation and Mook Badhir Mandal, Vadodara.

4. Used when the tutor report indicated that the content of the activity was grammar, without specifying the specific form of the activity engaged in during the lesson.

References

- Bailey, N. M. 2009. ““It Makes It More Real”: Teaching New Literacies in a Secondary English Classroom.” English Education 41: 207–234.

- Bartlett, L., D. Lopez, E. Mein, and L. A. Valdiviezo. 2011. “Adolescent Literacies in Latin America and the Caribbean.” Review of Research in Education 35: 174–207. doi:10.3102/0091732X10383210.

- Barton, D., and M. Hamilton. 2012. Local Literacies: Reading and Writing in One Community. London, New York: Routledge.

- Call-Cummings, M. 2016. “Establishing Communicative Validity: Discovering Theory Through Practice.” Qualitative Inquiry 23: 192–200. doi:10.1177/1077800416657101.

- Chevalier, J. M. 2013. Participatory Action Research [Electronic Resource]: Theory and Methods for Engaged Inquiry. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Cope, B., and M. Kalantzis. 2009. ““Multiliteracies”: New Literacies, New Learning.” Pedagogies: An International Journal 4: 164–195. doi:10.1080/15544800903076044.

- Corbett, M. 2015. “Rural Literacies: Text and Context beyond the Metropolis.” In The Routledge Handbook of Literacy Studies, edited by J. Rowsell and K. Pahl, 124–139. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Dickie, J. 2011. “Samoan Students Documenting Their Out-Of-School Literacies: An Insider View of Conflicting Values.” Australian Journal of Language and Literacy 34 (3): 247–259.

- Elkins, J., and A. Luke. 1999. “Redefining Adolescent Literacies. (Editorial).” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 43: 212.

- Gee, J. P. 2011. Social Linguistics and Literacies: Ideology in Discourses. London: Routledge.

- Gillen, J., N. Ahereza, and M. Nyarko. forthcoming. “An Exploration of Language Ideologies across English Literacy and Sign Languages in Multiple Modes in Uganda and Ghana.” In Sign Language Ideologies in Practice,edited by A. Kusters, M. Green, E. Moriarty and K. Snoddon. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter/Ishara Press.

- Gillen, J., S. Panda, U. Papen, and U. Zeshan. 2016a. “Peer to Peer Deaf Literacy: Working with Young Deaf People and Peer Tutors in India.” Language and Language Teaching 10: 1–7.

- Gillen, J., S. Panda, U. Papen, and U. Zeshan. 2016b. “Peer to Peer Deaf Literacy: Working with Young Deaf People and Peer Tutors in India.” Language and Language Teaching 5: 7.

- Hewagodage, V., and S. O’neill. 2010. “A Case Study of Isolated NESB Adult Migrant Women’s Experience Learning English: A Sociocultural Approach to Decoding Household Texts.” Internation Journal of Pedagogies and Learning 6: 23–40. doi:10.5172/ijpl.6.1.23.

- Kusters, A., M. Josef, M. D. Meulder, and D. O’brien. 2017. Innovations in Deaf Studies: The Role of Deaf Scholars. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Mayer, C., and G. Leigh. 2010. “The Changing Context for Sign Bilingual Education Programs: Issues in Language and the Development of Literacy.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 13: 175–186. doi:10.1080/13670050903474085.

- Naik, S. M., N. S. Mahendra, and A. Sharma. 2013. “Rehabilitation of Hearing Impaired Children in India - an Update.” Otolaryngology Online Journal 3 (1).

- Nirantar. 2007. Exploring the Everyday: Ethnographic Approaches to Literacy and Numeracy. Delhi: Nirantar.

- Papen, U. 2012. Literacy and Globalization: Reading and Writing in Times of Social Change. London: Routledge.

- Prinsloo, M., and M. Breier, eds. 1996. The Social Uses of Literacy. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Pyo, J. 2016. “Bridging In-School and Out-Of-School Literacies: An Adolescent EL’s Composition of a Multimodal Project.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 59: 421–430. doi:10.1002/jaal.467.

- Rehabilitation Council of India. 2011. Manual of Communication Options and Students with Deafness. New Delhi: Government of India.

- Rogers, A. 1999. “Improving the Quality of Adult Literacy Programmes in Developing Countries: The ‘Real Literacies’ Approach.” International Journal of Educational Development 19: 219–234. doi:10.1016/S0738-0593(99)00015-2.

- Skerrett, A., and R. Bomer. 2011. “Borderzones in Adolescents’ Literacy Practices: Connecting Out-of-School Literacies to the Reading Curriculum.” Urban Education 46: 1256–1279. doi:10.1177/0042085911398920.

- Smith, M. W., and D. W. Moore. 2012. “What We Know about Adolescents’ Out-of-School Literacies, What We Need to Learn, and Why Studying Them Is Important: An Interview with Michael W. Smith.” Journal of Adolescent & Adult Literacy 55: 745–747. doi:10.1002/JAAL.00089.

- Stewart, M. A. M. 2014. “Social Networking, Workplace, and Entertainment Literacies: The Out of School Literate Lives of Newcomer Latina/O Adolescents.” Reading Research Quarterly 49: 365–369. doi:10.1002/rrq.2014.49.issue-4.

- Street, B. 2012. “Letter: Learning for Empowerment through Training in Ethnographic-Style Research.” In Language, Ethnography, and Education: Bridging New Literacy Studies and Bourdieu,73–88. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Street, B., D. Baker, and A. Rogers. 2006. “Adult Teachers as Researchers: Ethnographic Approaches to Numeracy and Literacy as Social Practices in South Asia.” Convergence 39: 31–44.

- Street, B. V. 1993. “Introduction: The New Literacy Studies.” In Cross-Cultural Approaches to Literacy, edited by B. V. Street, 1–23. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Swanwick, R. 2010. “Policy and Practice in Sign Bilingual Education: Development, Challenges and Directions.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 13: 147–158. doi:10.1080/13670050903474069.

- Swanwick, R. 2016. “Deaf Children’s Bimodal Bilingualism and Education.” Language Teaching 49: 1–34. doi:10.1017/S0261444815000348.

- Zeshan, U., R. Huhua Fan, J. Gillen, S. Panda, U. Papen, K. Tusting, D. Waller, and J. Webster 2016. Summary Report on “Literacy development with deaf communities using sign language, peer tuition, and learner-generated online content: sustainable educational innovation”. Preston: University of Central Lancashire.