ABSTRACT

In 2014, the OECD-PISA’s Governing Board approved the addition of a set of global competence measures to its Programme of Student Assessment. In our paper, we explore whether and how there are discursive shifts between the two framing papers (2016/2018) and what the outcomes are for policy-shaping. To this end, we employ Network Text Analysis to map shifting semantic configurations. We show that (i) the concept of ‘global competence’ is radically redefined through the simplification and polarisation of the semantic universe surrounding it, (ii) that the concept ‘global’ becomes a shifting signifier which enables the establishment of an equivalence between the two studied documents, and that (iii) in this process, concepts such as ‘culture’ are now erased in the 2018 text. Our findings show the dramatic change of approach between the two documents reinforces a narrative that is familiar to the OECD around knowledge economy proxies.

Introduction

In 2014, the OECD-PISA’s Governing Board approved the addition of a set of global competence measures to its well-known Programme of Student Assessment (PISA) that was first launched in 2000. Two policy texts were released to frame the idea of global competences and the problems that they were to solve: Global Competency for an Inclusive World (OECD Citation2016) (hereafter GCIW) and Preparing Our Youth for a Sustainable and Inclusive World (OECD Citation2018) (hereafter PYSIW). Both policy documents argued that students need to acquire ‘global competences’ to meet the challenges offered by an increasingly connected, culturally diverse but unequal world.

Interestingly, though, the 2016 GCIW policy document had been removed from the OECD’s website when the 2018 PYSIW was launched, making it now unavailable for public readership. The seeming ‘erasure’ of the first policy document from public scrutiny seems to hint at the fact that the two documents were not meant to be complementary and suggests that the first text had become something of liability to the OECD. This made us particularly curious about the similarities and differences between the two texts and what this might signal around discursively driven political struggles. Fortunately for us, we had kept a hard copy of 2016 GCIW and managed to source an electronic version from an obscure blog in Poland. This digital version was important to enable us to undertake a systemic comparison of the two policy texts and to explain how, if at all, these alter meaning formation and policy shaping. In other words, we asked: what are the semantic clusters in each of these texts, and what work are these semantics clusters asked to do for policymaking?

To answer this question, our analysis proceeds on three levels. First, we undertake a broad qualitative reading of the two policy texts. Second, we employ an innovative methodology to critical discourse analysis – that of networked text analysis – to trace the semantic configurations, reconfigurations, and recalibrations of meaning of the two documents. Third, we identify and describe transformations in the use of the term ‘global’.

Our findings reveal a drastic change of approach between the two documents, portrayed by (a) the simplification and polarisation of the semantic universe surrounding global competences and (b) the disappearance of culture in favour of knowledge economy proxies. Accordingly, we show how the tacit substitution between the two documents highlights a central friction in the OECD definition of global competences centred around the concept of culture. We contend that the plurality of perspective required by a cultural approach hardly fits the view of culture implicitly assumed by the PISA, i.e. a culture tied to economic development.

We conclude with two reflections, one substantive, and the other methodological. Substantively, we show that controversies emerge for the OECD when it tries to navigate the politics of cultures, and that it deploys discursive strategies of erasure and equivalencing to create new articulations of meaning. In terms of methodology, we argue that Network Text Analysis (NTA) can reveal the ways in which particular configurations of semantic networks, and their relations within and to other networks, recalibrates meanings. This approach, by highlighting proximal and relational dimensions of clusters of concepts, moves us beyond the limitations of frequency and collocation approaches to the quantitative analysis of texts.

Setting the scene – the emergence of the PISA global competences framework

We begin with some scene setting to locate the OECD’s project on global competences contextually, and GCIW (OECD Citation2016) and PYSIW (OECD Citation2018) as policy responses and offer a first broad qualitative reading of them. Following the 2008 fiscal crisis, the OECD has become concerned over rising social inequalities, and the negative impact this is having on social cohesion and thus economic development. In 2011, the OECD presented an overview of growing income inequalities across the OECD countries and reflected on the dynamics driving such changes. Developing global competences and becoming a global citizen were also viewed by International Organizations (IO), Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs), and selected governments as a way of promoting a more open and inclusive world through education, and a means of realising the Sustainable Development Goal (SDG) 4.7 – global citizenship – by 2030 (Auld and Morris Citation2019).

In 2013, Harvard University’s Fernando Reimers was invited to submit a proposal to the OECD-PISA Governing Board on the value of developing a measure of global competence in the 2018 round of PISA data gathering (Reimers Citation2020). Work got underway as early as 2014 when Expert Panels were formed to take forward the initiative (Robertson, Citation2021a). Two key policy framing documents were produced by the OECD: Global Competency for an Inclusive World (Citation2016) setting out the rationale and indicative test items; and Preparing Our Youth for an Inclusive and Sustainable World: the OECD PISA Global Competence Framework (OECD Citation2018), which restates the rationale, introduces the underpinning model, and outlines the assessment strategy.

In the Introduction to its 2016 Report, the OECD (uncharacteristically, in our view) observes:

Globalization brings innovation, new experiences, higher living standards; but it equally contributes to economic inequality and social division. Automation and internet business models may have encouraged entrepreneurship, but they may have also weakened job security and benefits. For some, cross border migration means the ability to commute across continents; for others it means escaping poverty and war – and the long struggle to adapt to a new country. Around the world, in the face of widening income gaps, there is a need to dissolve tensions and rebuild social capital (OECD Citation2016, 1).

Given the central involvement of the OECD in driving forward three decades of neoliberalism, their admission that neoliberal globalisation had delivered growing social differences and inequalities is significant. For the OECD, the solution was the development of a set of competences in students that is added to their focus on literacy, science, and mathematics. It also takes the OECD into unfamiliar territory regarding culture, values, and attitudes – an issue we explore later in this paper.

The 2016 GCIW document defines global competences as:

… the acquisition of in-depth knowledge and understanding of global and intercultural issues; the ability to learn from and live with people from diverse backgrounds; and theattitudes and values necessary to interact respectfully with others (p.1).

In its 2018 PYISW document, the OECD defines global competence as:

… the capacity to examine local, global, and intercultural issues, to understand and appreciate the perspectives and world views of others, to engage in open, appropriate, and effective interactions with people from distinct cultures, and to act for collective well-being and sustainable development (p.7).

Whilst these broad definitions are similar, aside from the addition of sustainable development, a quick scan of 2016 GCIW suggests it is more wide-ranging than the 2018 PYISW document, and is more explicit in linking the diagnosis of the problem (social inequalities, income gaps social tensions (p. 1) with outcomes – such a subjective well-being and quality jobs, and ‘the benefits of growth are fairly shared across society’. More importantly, the 2016 GCIW promises to emphasise values which it points out:

… is novel in comparative assessment. Respect and a belief in human dignity place a stake in the ground for the importance of right and wrong and offer a counterweight to the risk that sensitivity to other viewpoints descends into cultural relativism. The dilemma at the heart of a globalised world is how we strike the balance between strengthening common values, that cannot be compromised, and appreciating the diversity of ‘proprietary’ values (p.2).

The OECD has come to dominate large-scale assessments in education in part because it has avoided an explicit engagement with culture (unlike UNESCO) by using more technical instruments such as statistical rankings to hide values (Robertson, Citation2021b). The turn to global competences thus represents a significant shift for the OECD in its assessment regime, and raises questions for us as to how it navigates the many challenges that then arise regarding whose culture, which values, and what counts as ‘right’?

Measuring the global competences of 15-year-olds is argued by the OECD to be important for governments to provide system-level data to countries. This would enable a country’s education system to develop interventions that ‘… invite young people to understand the world beyond their immediate environment, interact with others with respect and dignity, and take actions toward building sustainable and thriving communities’ (OECD Citation2018, 5–6). In 2018, PYISW the assessment strategy is also outlined: a cognitive test to measure knowledge and skills, and a student questionnaire to measure knowledge, cognitive skills, social skills, and attitudes. However now measuring values is argued is beyond the scope of the PISA 2018 study (OECD Citation2018), though clearly values underpin our capacity to understand others as they are shaped by their cultures.

The research literature so far

Research on the OECD’s PISA global competence framework is still emerging. Ledger et al. (Citation2019) undertake a network analysis of the bibliography of the OECD’s 2016 Report, focusing on the epistemic communities informing the OECD’s work on global competence. They find a limited range of epistemic influence, whilst highlighting the significant role of Darla Deardorff – an expert on intercultural competences – as a knowledge broker. Engel, Rutkowski, and Thompson (Citation2019) focus specifically on the 2018 report to examine the challenges of defining global competence. They argue that the idea of global competence can vary across countries, including the US versus Europe (see also Simpson and Dervin Citation2019). Grotluschen (Citation2018) points out that the OECD-PISA rationale takes globalisation as a given, draws attention to the Eurocentrism of the expert groups working on the development of the global competences, and outlines the dangers of stigmatising those in the ‘south’ who fail to measure up to a northern set of ideas. None of these authors so far engage in a comparison between the two policy documents. Idrissi, Engel, and Pashby (Citation2020) focus specifically on the OECD’s 2018 PYISW policy using Critical Discourse Analysis to examine whether there is evidence of individualisation, and whether multiculturalism and global competence is conflated. They show in their analysis that this conflation is taking place whilst at the same time focusing on mutual positivity and processes of othering, as opposed to the ethical tensions and structural issues that might lead to conflict in the first place (Idrissi, Engel, and Pashby Citation2020).

Cobb and Couch (Citation2021) do compare the 2016 GCIW and 2018 PYISW reports, along with a third; the PISA 2018 Assessment and Analytical Framework (OECD Citation2019) using a thematic analysis approach. Yet their focus is specifically on ‘inclusion’ as a concept and argue that over these three policy documents, inclusion is progressively narrowed so that there is a shift from understanding the self as a basis for understanding others, to understanding, and then finally interacting with others, drawing similar conclusions to Idrissi, Engel, and Pashby (Citation2020). Vaccari and Gardinier (Citation2019) also compare the OECD’s focus on global competences, however they limit their systematic analysis to the OECD’s 2016 GCIW and UNESCO’s 2014 report on Global Citizenship Education. Their main interest is in what key ideas are privileged by each of these global agencies. They show that whilst UNESCO focuses on dignity and rights, the OECD focuses on employment and dignity. This is likely to emerge as an issue in time given that the OECD (Citation2019) has tried to position itself as the agency to do the data collection for SDG4.7 which UNESCO oversights: the Global Citizenship Framework. Indeed, Auld and Morris (Citation2019, 677) suggest that ‘… the official conception finally adopted was strongly influenced by the organisations quest to position itself as the agency responsible for monitoring progress on the Sustainable Development Goal, and then amended to match what could be easily monitored’. They challenge the OECD’s claim that there is a global consensus on global competence and warn of the dangers of such an assessment existing.

In our first-cut qualitative reading of the two texts, we note that in the 2018 PYISW report, the problematising of GDP-growth models of economic development have disappeared, as does degrowth as a solution to climate change. In the 2018 PYISW, the main challenges are now seen to be the movement of populations across national boundaries, challenges of social integration, religious tensions, and new hazards arising from digital technologies. Now global competences are needed to ensure the employability of young people in changing global labour markets. The question of ‘how’, discursively, the OECD has shifted focus and thus its policy frame is particularly intriguing, and in doing so, what new meanings are now made visible and possible. We turn to this in the following section.

Discourse analysis and NTA

The relationship between power and language is a central focus of critical theory, as these elements are investigated as tightly intertwined and interdependent (Habermas Citation1981; Fairclough Citation2003). This theoretical stance has recently enjoyed growing popularity in both academia and society at large, sometimes leading towards a fetishisation of the power of texts, i.e. treating texts as symbolic substitutes of actual power on the ground. Before proceeding, then, it is worth stressing that, in our view, the link between power and language is not implied by but established through the analysis of its functioning (Robertson Citation2008). As the actual power of text ‘can only be described by reference to broader social theoretic models of the world’ (Luke Citation2002), we rely on Critical Realism to set our analysis of texts within society, as part of a continuous interaction between strategies, structures, and social relations.

Following Fairclough, Jessop, and Sayer (Citation2004), this can be described as a double movement. On the one hand, we investigate the semiotic conditions that make social events possible. That is, how discourses enable or inhibit the emergence of specific semantic constructs, such as identities and values, as well as their mutual relationships. On the other hand, we endeavour to identify the non-semiotic conditions that underpin the creation of discourses. Accordingly, we argue that discourses are an integral part of the functioning of social groups and, therefore, both result in and are an expression of socially established power structures. In contrast to a strict linguistic approach, Critical Discourse Analysis claims for itself the objective of investigating discourse as a social fact, thus recognising that ‘naturalized implicit propositions of an ideological character are pervasive in discourse’ (Fairclough Citation2010, 26) and play a key role in (re)producing relations of domination. In arguing this, Fairclough is reminding us that texts, such as the ones that we examine in this paper, as elements of social events have the potential for causal effects. Viewed as construals, under a particular set of conditions, these texts have the power to constitute social worlds (Fairclough Citation2003, 8). For this reason, analysing the OECD’s policy texts on global competences is important as they have to potential to shape social worlds.

Given this theoretical approach, a critical comparison between two documents cannot be limited to the enumeration of linguistic similarities and differences. Instead, it demands that we consider texts, with their lexical and structural peculiarities, as signifying wholes. In these terms, and crucially important for our analysis, the conceptual tools employed for the comparison of discursive traits is not a neutral analytical device. This is because the ways in which data are organised constructs a new object of study which is, among other things, a reflection of a given theoretical paradigm made coherent by its ideational underpinnings.

The conceptual toolbox we employ is composed of four basic processes that can be combined to describe complex semantic transformations and their underlying power dynamics. Since they define processes, these terms do not indicate immanent changes but always describe the passage between two different conditions.

Expression: this process identifies the passage between a situation in which a term is not present to a situation in which the term has been uttered. An expression implies a communicative action, an individual carrying it out, a medium, a language, a context, and a target audience (Jakobson Citation1960). Accordingly, the appearance of a given term should be considered as the result of the interaction between all these elements and the underlying power relations. Similarly, the absence of certain terms can potentially indicate meaningful changes in one or more of the abovementioned variables (Derrida Citation1980).

Erasure: this process identifies the passage between a situation in which a term is present to a situation in which the term has been removed. While absence define a status, and even a space for possibility, erasure identifies a process which negate the existence of a previously expressed term. Accordingly, an act of erasure indicates a power shift, to the point that elements previously included in the discourse are now identified and eliminated based on their congruence with the new paradigm. Moreover, a process of erasure poses the problem of the empty slot left by the erased term, which usually triggers a series of additional practices (e.g. substitution or rephrasing) aimed at neutralising the erasure process itself.

Differentiation: this process identifies the passage between a situation in which one element is present to a situation in which that element has been separated in two or more elements according to a series of discriminant traits. Approaching difference as the result of a process of differentiation, rather than a pre-set condition, is fundamental to understand its function in meaning-making processes (Currie Citation2004; Deleuze Citation1994). In a nutshell, a difference is established when a set of discriminating traits is applied by a subject to an object otherwise perceived as a unity. This set of discriminating traits pre-exists the differentiated elements and is already valorised as significant. Accordingly, it is in the emergence (or non-emergence) of discriminating traits that the functioning of ideologies can be identified.

Equivalence: this process identifies transformation of two or more elements into a cluster identified by a common trait. As in the case of difference, the establishment of an equivalence follows a triadic structure (Peirce Citation1902, 101), i.e. two elements can be connected only through a third element which act as a semantic joint. In these terms, then, the emergence of an equivalence implies the establishment of a trait, sometimes articulated in form of scale, that acts as a unifier or, in a way, as a translator. As stressed by Laclau and Mouffe (Dabirimehr and Fatmi Citation2014), the establishment of chains of equivalence is often employed to homogenise discourses, thus preventing the emergence of differentiations.

Note on method: Tracking morphic incongruence through NTA

Our study aims at describing ‘how’ the concept of ‘global competences’ underwent significant redefinition in the process of being included as a subject of evaluation in the PISA. To this end we are interested in what discursive concepts are expressed and which are erased, as well as how semantic meanings are established through discursive strategies, such as equivalences or differentiation. Examining the discursive shifts occurring between the two policy reports poses a series of methodological challenges arising not only from the complexity of the case under scrutiny, but also from the risks inherent in discourse and data analysis. Accordingly, this section will provide an overview of how NTA has been employed so to optimise meaning mapping and to enable comparison between the two texts.

The first peculiarity of the present study is that it focuses on the smallest comparative case study possible, i.e. two texts. Accordingly, these texts can be compared in relation to each other, but such comparison does not allow the abstraction of endogenous categories and patterns, as this would require tracing such patterns on a larger scale. To address this problem, we drew on NLP tools and tailored them to extract large volumes of information from single texts, thus moving the analysis from a wide-ranging to an intensive approach (Sayer Citation1992). The obtained information was then reorganised as a network, thus enabling datasets to be explored as single semantic structures.

The use of NTA represents the second peculiarity of this study and raises the issue of the organisation and operationalisation of datasets. Data were initially extracted using AntConc (Anthony Citation2020), a freeware corpus analysis software. In each document, the 20 most frequent terms were detected and, for each term, correlates were identified in a range of 10 items. A stop-list was employed to prevent non-significant terms form being included in the results. This led to the identification of 671 unique terms and 2086 relationships for the first document (2016) and 969 unique terms and 2804 relationships for the second document (2018). Data were then combined to produce a set of nodes and edges that could be imported into Gephi, a network analysis software. Through this process, each document was mapped as a single network. Network analysis functions, such as modularity (Louvain method) and in-betweenness, were employed to isolate and visualise what we refer to as ‘semantic galaxies’ (Hunter Citation2014).

The possibility of translating documents into semantic networks yields a double advantage. Firstly, the semantic morphology of each document is translated into a distinctive semantic network, thus avoiding the risk of a biased comparison between unprocessed texts. It should be noted that, as a further precaution, the researcher in charge of processing the texts did not read them before completing the task. Secondly, it allows the identification of deductive categories and their investigation. Accordingly, the second stage of the analysis consisted in comparing the semantic universes unfolding around the term ‘global’. To this end, the first 30 correlates in a range of 10 items have been collected in both documents and organised by frequency on a spreadsheet for comparison. As we show below, the data highlight a deep change in the perception of the global and suggest a larger transformation taking place between the two texts. In our view this also hints at the motivations that led to the disappearance and thus erasure of GCIW from the OECD’s official website.

Comparing the two PISA-Global competence framework documents

In this section, we compare the two documents on different dimensions: (a) network structure; (b) semantic clusters and meanings; (c) betweenness-centrality network, and (d) the semantic galaxy that orbits around the global. In these comparisons, we can see ongoing processes of expression, erasure, differentiation, and equivalences, because of re/articulations of discourses on global competences for 15-year-old learners by the OECD.

Comparing networks

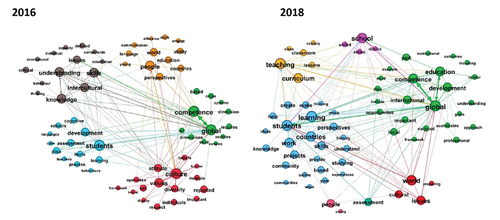

Our attention is on whether and how semantic galaxies alter in shape, thus reshaping the reader’s understandings of global competences. As shows, an expanded document does not mean a more complex set of discursive expressions. Indeed, it is quite the opposite. The analysis of the 2016 GCIW reveals five, relatively balanced universes with their own set of semantic clusters: (I) global competence [green]; (ii) students [blue]; (iii) people [orange]; (iv) knowledge [grey]; and culture [red].

The 2018 PYISW, however, shows considerable discursive polarising and narrowing. There are two macro-semantic universes: (i) global competences [green] and (ii) students [blue], with a few minor satellites – teaching [orange], school [pink] and world [red] on the periphery. The discursive plurality of 2016 GCIW, that might have opened the space for more diverse associations and thus interpretations regarding the state of the world, have been erased and is now dominated by two ideas: global competences and students, their learning and work. Remarkably, the culture galaxy – highly visible in 2016 GCIW – has now almost disappeared in 2018 PYISW. This begs the question: was the idea of culture too challenging for the OECD to retain with that degree of visibility, and in this form? Historically, the OECD has avoided the concept of culture and the controversies that inevitably surround it when the matter of whose social ontology will underpin assessment questions around which beliefs, values and practices are drawn into a one-size fits all large-scale assessment.

Equally as remarkable is that ‘culture’ as noun (the quality of a person, place thing, event) in 2016 GCIW is now expressed as ‘cultural’ which is an adjective (a description of a society) in 2018 PYISW. With ‘culture’ now replaced by ‘cultural’ we see a shift in the object/subject of attention from the self to society/world. Put differently – we note that the focus of culture is a rich set of qualities of a person (attitudes, openness, values, diversity and so on) to be acquired as a specific capability or way of looking at the world. In contrast, the concept ‘cultural’ snow shifts out attention to understanding the milieu of a society which young people need to prepare for. This is an onto-political move which shifts attention away from the attitudes, values, and skills that students might acquire to be globally competent, towards the qualities of any society or world order which a student should be prepared for.

Comparing the semantic clusters and their meanings

Another way of presenting the different morphologies of the 2016 GCIW and the 2018 PYISW is to compare the discursive expressions in each, and to observe which are erased, whether new terms are added, and what new meanings emerge when expressions are bought into new semantic patterns. As shown in , semantic clustering based on modularity enables us to observe how: (i) there is little lexical overlapping between the main semantic galaxies and (ii) there are two different processes through which such difference is constructed. In relation to the overlap only the broadest of associations survives; OECD, future, learning and young. The nature of the problem that is articulated in 2016 GCIW to be resolved through global competences for students involving others (people), knowledge about them, and a valuing of them and their culture, has been erased. More than this, knowledge and culture are also erased completely so that they are not expressed in new articulations (see – right hand column). This is a double erasure.

Table 1. Comparison of semantic difference and overlap between OECD’s 2016 and 2018 global competence reports. The table includes only terms with a minimum in-degree of 5.

While the semantic galaxies surrounding ‘people’, ‘knowledge’ and ‘culture’ are erased, those orbiting around ‘global competence’ and ‘student’ are completely rearticulated (Snir Citation2017). Accordingly, it can be noted how an implicit equivalence is drawn between the definition of global competence in 2016 GCIW compared with that in 2018 PYISW; an equivalence that creates an implied, yet non-existent, homogeneity between the two discourses (Dabirimehr and Fatmi Citation2014). Indeed, we can see that the concepts of ‘global competences’ and ‘students’ have many more and different qualifiers associated with them. Regarding ‘global competences’, ‘complexity’ and ‘society’ are now replaced with ‘development’, ‘opportunity’, ‘professional’ and ‘outcomes.’ Regarding ‘students’ – the terms ‘development’, ‘assessment’ and ‘learning’ are now replaced with ‘work’, ‘skills’, ‘project’, ‘knowledge’, ‘studying’ and ‘community’. Effectively, we see a narrowing down in the 2018 PYISW, away from societal and cultural issues which global competences are needed to help resolve, to those associated with global workplaces, such as ‘skills’ and ‘learning’.

A comparison of betweenness-centrality nodes in the network

Betweenness-centrality (BC) is a measure that quantifies the centrality of each node in a network. In other words, it indicates how much a given node is connected to all the others. Accordingly, in NTA BC enables the identification of those words that most commonly act as what can be called ‘bridges’ between different semantic galaxies.

The detection of these terms which becomes possible when approaching texts as networks represents a step beyond the frequency-based measures offered by traditional corpus linguistics tools. For example, if a word has a high frequency but appears only in specific contexts it is likely to have a lower BC degree than less frequent but more evenly spread words. Accordingly, the measurement of BC is useful to further expand, both qualitatively and quantitatively, the observations proposed in the previous section.

lists the terms with the highest BC degree in the two studied documents. Before going into details, a general observation confirms a morphological incongruence already suggested by the visualisation of the semantic networks. The average BC difference in PYISW is more than double than that of GCIW (see bottom of the table). This means that in PYISW the various sematic galaxies are connected by a few specific terms, while in GCIW that function is more evenly distributed. This is also visualised by the blue graph positioned beside the lists. As it can be noted, in GCIW BC values decrease in an approximatively linear manner whilst in PYISW they follow a hyperbolic trend, with the top terms having a significantly higher BC degree than all the others.

Table 2. Comparison of betweenness-centrality.

From a qualitative perspective, the analysis of BC highlights two main transformations: (i) the erasure of certain terms and the expression of new ones; and (ii) the different relevance given to the terms shared by the two documents through new articulations of equivalence. In relation to the first transformation, it can be observed how certain words that are significant in terms of BC appear uniquely in one of the two documents (in white). The appearance or disappearance of certain terms can indicate important semantic shifts. More specifically, in the passage from GCIW to PYISW terms such as ‘values’, ‘knowledge’, ‘attitude’, ‘skills’, ‘intercultural’, ‘diversity’ and ‘communication’ completely lose their bridging role.

Conversely, terms such as ‘teaching’, ‘school’, ‘issues’, ‘work’, ‘curriculum’ and ‘project’ are introduced. By comparing these data in with those presented in , we can see how the disappearing terms belong mostly to the semantic universes centred around Culture and Knowledge, while the appearing ones are almost standalone terms that develop a limited sematic network around them. Accordingly, the polarisation of the semantic network corresponds in this case to the substitution of some connecting concepts. In the first document these concepts were integrated into larger semantic galaxies, that is, they were part of a discourse, while in the second one they play mostly a functional and independent role.

The second transformation concerns the different relevance attributed to those terms whose BC remains significant in both documents (in colours). While the reader is here invited to independently navigate the presented data, we will focus only on some traits of interest. Firstly, the term ‘student’ assumes a remarkable centrality in 2018 PYISW. Indeed, its BC value is approximatively double of that of any other term in both documents. This peculiarity underscores how students become a trait d’union of PYISW in an almost monopolistic manner; a sharp difference from GCIW, where ‘culture’, ‘global’, ‘student’ and ‘values’ have comparable levels of BC. Secondly, the term ‘culture’ passes from being the main bridging term in 2016 GCIW to almost disappearing in 2018 PYISW.

This transformation, especially if considered in relation to the disappearance of terms such as ‘values’ or ‘diversity’, suggests a significant anti-cultural shift in the OECD discourse. As previously noted, while in 2016 GCIW culture is seen as part of a conceptual prism which act as a joint between the various semantic galaxies, in 2018 PYISW it appears mostly as an adjective (‘cultural’). Moreover, it is often related to concepts such as ‘world’ and ‘issues’, a trait which might imply a problematic, if not slightly negative, connotation. Finally, it can be observed how educational terms (for example, ‘education’ and ‘learning’) become central in 2018 PYISW. This is coherent with the simultaneous appearance of new words which mostly belong to the same lexicon, as discussed above, and reinforces the performance-oriented and assertive nature of this document.

Comparing the ‘global’ semantic galaxy

In this section, we focus specifically on the global, its changing relationship to culture and other discursive ideas over the two reports. In , we represent the semantic galaxy orbiting around the term ‘global’ in the two documents and the systems of meanings which underpin different conceptions of globality. This dataset displays the main correlates (10LR) of the term global and is composed of two sections within .

Table 3. Comparing the global semantic galaxy.

The first section in the black frame at the top of spotlights a significant quantitative difference between the analysed texts; that is, the seeming disappearance of a culture-related lexicon in the second document and its association with globalisation. Therefore, unlike the word ‘global’ whose presence in the two texts remains comparable, ‘culture’ cannot be taken as a focus of comparison. Indeed, culture is more frequent and visible than global in 2016 GCIW whilst in 2018 PYISW the global grows and culture shrinks.

The second and larger section of lists the correlates of the term ‘global’ in order of frequency, reporting both the total number of occurrences and their frequency weighted on the total number of times the word ‘global’ appears. For example, in 2016 GCIW, the term ‘competence’ is related to ‘global’ in 68.5% of the cases.

Competences and students are magnified while ‘understanding’, ‘knowledge’, ‘intercultural’ and ‘issues’, are replaced by ‘education’, ‘school’, ‘teachers’, ‘development’, ‘world’ and ‘learning’.

The politics of in the OECD’s PISA-Global competence assessment

What conclusions might we draw regarding the OECD’s Global Competence assessment from the evidence we have presented in the previous section? The first thing to say is that the dramatic discursive differences between the two documents suggests the underpinning ideational base is in flux registered through (I) dramatic erasures, (ii) new differences and equivalences being established, and (iii) a transformation in the meaning of the text and instrument. Drawing on Networked Text Analysis, we have shown that in 2016 GCIW is composed of a plurality of discursive elements whose overall expression acts as a chain of equivalences. In this case, that the problem of deepening social inequalities, social divisions, tensions, and conflict in communities is seen to be potentially resolved by students developing an understanding of the other via cultural knowledge including their differences, values, respect, and open-mindedness. The focus here is on the student acquiring an understanding of themselves as a basis for understanding the other.

In this regard, we agree with Cobb and Couch’s (Citation2021) conclusion; that the underpinning ideas shaping a cultural politics of the other (in their paper through inclusion) rotates around transformations in the attitudes and values of the self to effect relational changes leading to transformations in social orders. In Nancy Fraser’s conceptual framing, this is a politics of recognition (Fraser et al. Citation2004). Whilst recognition is important, structural inequalities tied to what Fraser calls the politics of ‘redistribution’ are ignored. In our view this matters and is a major limitation in the possibilities of 2016 GCIW to resolve the social inequalities that have caused conflict and resentment in societies (see Cohen Citation2019) that the OECD identifies.

Second, through a comparison of the two documents weighted in terms of their size, we were able to demonstrate a different set of ideational underpinnings had emerged in the OECD’s 2018 PYISW giving rise to new meanings. Our NTA reveals semantic galaxies and their universes now reduced to two main ones (with some disconnected satellites) composed of a new set of expressions generating a new chain of meaning. The discursive expressions now rotate around students and competences much more closely tied to school-based learning about others in countries separate from one’s own, with the view that these are useful for a global workplace. The 2016 socio-cultural justification is replaced with an economic justification, bringing the assessment much closer to values that the OECD is familiar with (Vaccari and Gardinier, Citation2019; Robertson, Citation2021a). This dramatic erasure of the socio-cultural, and its re-expression as economic, shifts the focus of the problem-solution away from recognition politics to a more instrumental understanding of others for the purpose of flexibility operating in global capitalist labour markets. This is also an orientalist approach to the other in that it reduces the other to outward exotic features now parsed as cultural.

Third, Engels et al. (Citation2019) put the case that the OECD has pursued a strategy of dynamic nominalism; that is, that the essence and thus identity of a category (in this case the ‘globally competent student’) shifts over time. This is clearly the case here, but we note that in policymaking, typically policy takes the form of incremental adjustments to categories in what are called first- and second-order changes (Hall Citation1993, 279). Yet between the two iterations of the OECD’s PISA-Global Competence assessment framework we do not see incremental adjustments. We see a radical movement in the underpinning ideational base in what policy-makers call ‘third order’ change. First- and second-order changes do not disturb the overall understanding of purpose too much, whilst third-order changes make visible competing ideological frames and purposes. We argue that this radical reworking suggests an evasive nominalism. The OECD is clearly having considerable difficulty landing the core idea at the heart of being global competent for students which participating countries/economies can buy into. This calls into question the OECD’s capacity to generate solutions to the structural problems that it has identified.

Fourth, evidence reported elsewhere suggests that the OECD’s linking of culture to global competences has been highly controversial because globalisation and culture are both highly contested concepts. Sälzer writes candidly about the OECD’s PISA 2018 German National Project team, and their concerns over the lack of robustness of the core concept – global competence, the stereotypical assumptions of some items, and lack of clarity around what were right and wrong answers (cf. Sälzer and Roczen Citation2018). This is hardly surprising given that there are diverse views amongst the international teams regarding what it might mean to be globally competent, and how to measure it in a global cross-national assessment programme. In any event, values were dropped from the 2018 OECD-PISA Global Competence assessment. The effect of this was to reorient the focus away from the values held by individuals and what this tells us about the community and society they function in, to knowledge about others in the world and how this is useful for the world of work as it is mediated by global capitalism.

Fifth, the engagement of countries/economies with the PISA 2018 Global Competence assessment has been notably poor. Only 27 countries/economies, (from a total number of 79 countries/economies collecting PISA data in 2018), agreed to run the global competence cognitive test and complete the self-report survey (by students, school leaders, teachers, and parents), whilst 66 countries/economies completed the self-report survey only. There are also notable absences in country participation in the cognitive and self-assessment tests making up the global competence measure, including the United States, Japan, Germany, France, Finland, Denmark, and Sweden (OECD Citation2020).

The OECD’s PISA 2018 Global Competence results make for very mixed reading (OECD Citation2020). Across the four areas of competence making up the model adopted by the OECD (Citation2018) there is almost no overlap between those countries/economies scoring highly on the cognitive test (for example, Canada, Hong Kong and Scotland, UK) compared with those scoring highly on the student self-report (for example, Albania, Greece, and Korea) (OECD Citation2020). This suggests students from different countries/economies hold quite different self-understandings compared with the countries/economies being scored right or wrong on the cognitive test. It is also not clear what participating countries might make of the results for themselves, or what educators might learn from the results for classroom teaching. The fact that the OECD did not release the results until October 2020, and when it did it was via an obscure conference run by American Field Services, indicates the OECD’s global competence assessment tool, its take-up, and findings, is very problematic. We make this point as it is too easy to claim too much regarding the effects of the assessment on shaping national education systems.

Conclusions

This paper has sought to serve two purposes, one methodological and the other substantive. On a methodological note, we stress the potential of NTA for the study of policy texts. As this study has shown, the analysis of policy documents cannot be limited to the enumeration of linguistic elements, as this form of quantification pulverises texts into ‘atomic particles’. From a critical realist perspective, NTA enables us to make a step forward in the direction of describing semiosis as a socially situated event; an event that both ‘proceeds from’ and ‘has the potential for’ causal effects (Fairclough Citation2003). By mapping the semantic morphology of texts, NTA treats policy documents as signifying wholes, whose integrity and articulation represent the very object of interest. This allows researchers to avoid different forms of reductionism. Indeed, texts are neither approached as semiotic manifestations from which social structures can be induced in an almost deterministic manner and nor are they mere symptoms of otherwise independent social dynamics. We have shown that through NTA, texts can be investigated as semiotic objects whose morphology is causally integrated in the society that shaped them and themselves contribute to shape. It is their relationality that we seek to make visible and thus what readings are either made possible through forms of equivalence and differentiation, and what are erased.

Substantively, we provide evidence that the OECD’s Global Competence Framework and assessment tool is both controversial and unstable. It is controversial because of the presence of the concept of culture; it is unstable in that it is evident from the quite different morphologies of the two OECD documents, that 2016 GCIW and the 2018 PYISW have little in common with each other. Our hunch is that 2016 GCIW was too difficult to operationalise for the OECD, politically and culturally. Its one-size-fits-all approach to large-scale assessment via PISA tools, attempts to create equivalences between sub/national systems of education. Unlike UNESCO, historically the OECD has steered clear of the thorny ‘culture‘ matter, as it begs the question – ‘whose culture’ is being privileged in this one-size fits all model of assessment? 2018 PYISW can understood as an effort to discursively recalibrate its policy solution to bring it more into line with its longer standing programme of policy intervention work tied to human capital, economic development, individualism and liberalism. And whilst we see a move away from a cultural project of recognition to an economic project, this latter specification would appear to have embraced the very politics that led to the problems that the OECD has identified which need resolving; social inequalities arising from distributional issues, structural violence, and so on. We make this point strongly to highlight the challenges facing the OECD’s global competence assessment tool and to underscore its nominal fragility. In Engel et al’s (Citation2019) terms, we can see dynamic nominalism at work, but in a schizophrenic manner. How the OECD moves forwards with this project will be closely watched by those of us interested in international organisations, how they seek to govern in the absence of sovereignty, and their limits.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Anthony, L. 2020. “AntConc (Version 3.5.9) [Computer Software].” Tokyo, Japan: Waseda University. https://www.laurenceanthony.net/software

- Auld, E., and P. Morris. 2019. “Science by Streetlight and the OECD’s Measure of Global Competence: A New Yardstick for Internationalisation?” Policy Futures in Education 17 (6): 677–698. doi:10.1177/1478210318819246.

- Cobb, D., and D. Couch. 2021. “Locating Inclusion within the OECD’s Assessment of Global Competence: An Inclusive Future through PISA 2018.” Policy Futures in Education 1–7. doi:10.1177/14782103211006636.

- Cohen, J. L. 2019. “Populism and the Politics of Resentment.” Jus Cogens 1 (1): 5–39. doi:10.1007/s42439-019-00009-7.

- Currie, M. 2004. Difference. Hove, East Sussex: Psychology Press.

- Dabirimehr, A., and M. T. Fatmi. 2014. “Laclau and Mouffe’s Theory of Discourse.” Journal of Novel Applied Sciences 3 (11): 1283–1287.

- Deleuze, G. 1994. Difference and Repetition. New York: Columbia University Press.

- Derrida, J. 1980. Writing and Difference. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

- Engel, L., D. Rutkowski, and G. Thompson. 2019. “Toward an International Measure of Global Competence? A Critical Look at the PISA 2018 Framework.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 17 (2): 117–131. doi:10.1080/14767724.2019.1642183.

- Fairclough, N. 2003. Analysing Discourse: Textual Analysis for Social Research. London and New York: Routledge.

- Fairclough, N., B. Jessop, and A. Sayer. 2004. “Critical Realism and Semiosis.” Realism, Discourse and Deconstruction 23: 42.

- Fairclough, N. 2010. Critical Discourse Analysis: The Critical Study of Language. 2nd ed. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Taylor & Francis.

- Fraser, N., H. Dahl, P. Stoltz, and W. Rasmus. 2004. “Recognition, Redistribution and Representation in Global Capitalist Society.” Acta Sociologica 47 (3): 374–382. doi:10.1177/0001699304048671.

- Grotlüschen, A. 2018. “Global Competence – Does the New OECD Competence Domain Ignore the Global South?” Studies in the Education of Adults 50 (2): 185–202. doi:10.1080/02660830.2018.1523100.

- Habermas, J. 1981. “The Theory of Communicative Action.” In Reason and the Rationalization of Society, edited by T. McCarthy. Vol. 1. Boston, MA: Beacon.

- Hall, P. 1993. “Policy Paradigms, Social Learning, and the State: The Case of Economic Policymaking in Britain.” Comparative Politics 25 (3, April): 275–296. doi:10.2307/422246.

- Hunter, S. 2014. “A Novel Method of NTA.” Open Journal of Modern Linguistics 4 (2): 350. doi:10.4236/ojml.2014.42028.

- Idrissi, H., L. Engel, and K. Pashby. 2020. “The Diversity Conflation and Action Ruse: A Critical Discourse Analysis of the OECD’s Framework for Global Competence.” Comparative and International Education 49 (1): 1–19. doi:10.5206/cie-eci.v49i1.13435.

- Jakobson, R. 1960. “Linguistics and Poetics.” In Style in Language, edited by T. A. Sebeok, 350–377. MA: MIT Press.

- Ledger, L., M. Their, L. Bailey, and C. Pitts. 2019. “OECD’s Approach to Measuring Global Competency: Powerful Voices Shaping Education.” Teachers College Record: The Voice of Scholarship in Education 121 (August): 1–40. doi:10.1177/016146811912100802.

- Luke, A. 2002. “5. Beyond Science and Ideology Critique: Developments in Critical Discourse Analysis.” Ann Rev Appl Linguist 22: 96–110. doi:10.1017/S0267190502000053.

- OECD. 2016. Global Competency for an Inclusive World. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2018. Preparing Our Youth for an Inclusive and Sustainable World. The OECD PISA Global Competence Framework. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2019. PISA 2018 assessment and analytical framework. Paris: OECD.

- OECD. 2020. PISA 2018 Results (Volume VI) are Students Ready to Thrive in an Interconnected World. Paris: OECD.

- Peirce, C. S. 1902. “Logic as Semiotic: The Theory of Signs.” In Philosophical Writings of Peirce, edited by J. Buchler, 98–120. New York: Dover Publications.

- Reimers, F. 2020. “Curriculum Vitae.” https://fernando-reimers.gse.harvard.edu/files/fernandoreimers/files/cv_fernando_m_reimers_short_may_2020.pdf

- Robertson, S. (2008). “Approaching Critical Discourse Analysis (CDA) for Education Policy Analysis: Theory and Analytical Categories.” Working Paper, Centre for Globalization, Education and Societies, University of Bristol, UK.

- Robertson, S. L. 2021a. “Provincializing the OECD-PISA Global Competences Project.” Globalisation, Societies and Education 19 (2): 167–182. doi:10.1080/14767724.2021.1887725.

- Robertson, S. L. 2021b. “Guardians of the Future: Anticipatory Global Governance in Education.” Global Society 36 (2): 188–205.

- Sälzer, C., and N. Roczen. 2018. “Assessing Global Competence in PISA 2018: Challenges and Approaches to Capturing a Complex Knowledge Construct.” International Journal of Development Education and Global Learning 10 (1): 5–20. doi:10.18546/IJDEGL.10.1.02.

- Sayer, A. 1992. Method in Social Science. London and New York: Routledge.

- Simpson, A., and F. Dervin. 2019. “Global and Intercultural Competences for Whom? By Whom? For What Purpose? An Example from the Asia Society and the OECD.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 49 (4): 672–677.

- Snir, I. 2017. “Education and Articulation: Laclau and Mouffe’s Radical Democracy in School.” Ethics and Education 12 (3): 351–363. doi:10.1080/17449642.2017.1356680.

- Vaccari, V., and M. P. Gardinier. 2019. “Toward One World or Many? a Comparative Analysis of OECD and UNESCO Global Education Policy Documents.” Int J Develop Educ Gobal Learn 11 (1): 68–86. doi:10.18546/IJDEGL.11.1.05.