ABSTRACT

The ‘grain hypothesis', postulated by James Scott, suggests that cereals are ‘political crops’ intrinsic to state formation. Drawing the classical agrarian political economy of maize into dialogue with recent more-than-human political ecology, we explore the grain hypothesis with empirical material from present day Malawi and India. The evolution and ecology of the maize plant, we argue, has made it a strong agent of history, one that has enabled resilience, but also facilitated state and capital entanglement in the global agro-food system. This imperial maize assemblage is set on expansion, but it will continue to meet resistance in coevolved peasant-maize alliances.

People and corn depend upon each other in order to subsist and survive as a species. They are members of the same close-knit club, almost a clan. The millions who have domesticated these plants on the new continent have come into a valuable inheritance. In the course of their collective labor, they have accumulated and at the same time diversified genetic materials and knowledge and invented corn, a human offspring, our plant kin. (Warman Citation[1988] 2003, 27)

Maize is a versatile player, which both shapes and takes the shape of the societies that cultivate it. (McCann Citation2005, 1)

1. Introduction

Towards the end of his magisterial study Corn & Capitalism: How a Botanical Bastard Grew to Global Dominance, Mexican anthropologist Arturo Warman (Citation[1988] 2003) allows himself to speculate about the future of maize:

Whatever may have been the course corn followed in its migration abroad and whoever may have introduced and promoted the plant, the role of this American cereal becomes more important in times of accelerated transformation, in circumstances of rupture and disjuncture.

Drawing on empirical material from India and Malawi, this contribution considers the trajectory of maize in the capitalist world economy since Warman’s study and will focus especially on the idea of the crop’s botanical virtues. We argue that a long-overdue revisit of Warman’s classic (but perhaps also somewhat under-acknowledged) study may allow us to bring maize into view of the recent ‘turn’ to more-than-human and interspecies relations in political ecology and related fields (Robbins Citation2007, Citation2019, Tsing Citation2013; Moore Citation2015; Hartigan Citation2017; Guthman Citation2019). Crucial to our purposes, more-than-human perspectives invite us to explore what maize makes human beings do. While Warman and a number of other scholars have established maize as a key crop in empire building – an imperial crop – the implications of thinking about the current trajectory of imperial maize through the prism of the more-than-human remain little explored.

We suggest that a surprisingly apt – and provocative – place for rooting an understanding of maize in the present is found in the archaic past. In his recent work on early state formation, James Scott (Citation2017) presents what he calls ‘the grain hypothesis’ postulating an intrinsic linkage between state formation and grains including maize. ‘Grains make states’, Scott (Citation2017, 128) writes, proceeding to explain how early states constituted multispecies ‘assemblages’ composed of humans, animals and grains. Scott further describes the colonizing – imperialist – expansions of these assemblages across widening portions of the earth, incorporating new sets of multispecies relations through war, slavery and violent appropriation. Is it possible to say that the grain hypothesis holds its significance to this day?

Through our comparative examples from India and Malawi we explore the insights more-than-human perspectives can contribute to understanding the role of maize in current agro-food systems. Following Anna Tsing (Citation2013), we structure our study according to ‘form’ and ‘assemblage’. By assemblage we refer to the entanglement of maize with human and non-human actors and institutions, thus an extension of Scott’s ‘multispecies assemblage’. Bringing form and assemblage together, we seek to foreground the role of the materiality of the maize plant – its ecology, genetics and how this is shaped by plant breeding – to the patterning of agro-food systems. In so doing, we aim to show how engagement with more-than-human theoretical perspectives ‘forces political ecology to consider more seriously the known ecology, mechanics, genetics, engineering and physics of the world in which struggles are enmeshed’ (Robbins Citation2019, 231).

Critical scholars analyzing the political economy of the globalized industrial agro-food system often focus on multinational agribusiness, the flow of capital and changing cropping patterns, yet the materialism in this literature also grants the biology of the maize plant a significant role in shaping the system. The human-maize relationship can be seen as dialectical, as in Moore’s (Citation2015) ‘double internality’ denoting the co-production of human societies and the rest of the ‘web of life’. There is continuity in this view of the relationship and post-humanist perspectives on world-making entanglement (Haraway Citation2015).Footnote1 In this view, people are not only situated, but also formed in ecological networks. Decentering the human in the perspective on current developments reveals that it was not only in pre-history that maize’s ecological properties shaped society, it still does.

In Malawi, maize production has since the early twentieth century steadily increased to complete domination in diet and food culture. In India, maize production has surged as an industrial ‘flex crop’ over the last two decades. Despite differences in configuration, we find striking similarities and interconnections between the maize assemblages in the two countries. Inspired by Warman, Scott and more-than-human theory in our study of the way maize is raising to dominance in agro-food systems around the world, we propose that it is meaningful to speak about an imperial maize assemblage. We find this concept useful not only to understand pre-Columbian empires but also colonial slave-economy, post-independence development states and present day’s agro-food systems. The more-than-human theoretical perspectives thus bring into focus not only the political economy maize is part of but also how the maize plant’s evolution and ecology enables the imperial maize assemblage to pull in land and capital, increasingly transforming populations around the world into ‘maize people’.

This article is structured as follows. We start by spelling out our conceptual approach to the imperial maize assemblage, putting Scott’s ‘grain hypothesis’ into dialogue with recent work in more-than-human political ecology. This section also outlines the form/assemblage analytic structuring of the article. Next, we proceed to revisiting Warman’s classic work in view of this analytic, locating Warman in broader streams of environmental history and agrarian political economy. This revisit allows us to tease out tendencies in Warman to think in terms of form/assemblage. Yet these tendencies can be further consolidated and brought to bear on the present in view of the concept of the imperial maize assemblage, which is what we then attempt in the subsequent section of the article. This section has two parts: first, we explore form and, then, assemblage through empirical material from Malawi and India. Finally, we offer a concluding discussion synthesizing our insights into maize dialectics and reflecting on the prospects for resistance in alternative peasant-maize alliances.

2. The imperial maize assemblage

From farmers’ manifold activities in their fields to states to science to transnational corporations, maize forms part of assemblages that expand across the earth; in other words, what we propose calling the imperial maize assemblage. Exploring early state formation, Scott (Citation2017) presents what he calls the ‘grain hypothesis’ positing an intrinsic link between grains and states. In the early ‘grain states’, particular cereals with their specific traits were necessary but not sufficient preconditions for the appropriation of land, the conquest of populations and the expansion of state space. Cereal grains, Scott argues, were unique among crops in their utility for states, as ‘only the cereal grains can serve as a basis for taxation: visible, divisible, assessable, storable, transportable, and “rationable”’ (Scott Citation2017, 129). Following from this, Scott writes: ‘These qualities are what make wheat, barley, rice, millet, and maize the premier political crops’ (Scott Citation2017, 131 emphasis in original). Drawing populations and cereal grains together into ‘assemblages’, states were thus from the beginning multispecies phenomena.

Scott’s grain hypothesis presents us with the imperial maize assemblage in a ‘rudimentary’ form, embedded in what Scott calls the ‘agro-ecology of early states’. In what follows, we attempt letting Scott’s hypothesis ‘travel’ to the present. As part of thinking assemblages as multi-species phenomena, a common notion is that non-human nature has agency through its interaction with other actors (Robbins Citation2019). Such interactions are often intimate entanglements in which both the human and non-human actors are transformed in the process. Drawing upon a key insight from Moore’s world-ecology, we refrain from thinking of agency as structured by the ‘Cartesian divide’ of Nature and Society, but instead, hold that ‘agency is a relational property of specific bundles of human and extra-human nature’ (Moore Citation2015, 37 emphasis removed). Our approach to ‘form’ and ‘assemblage’, as described below, seeks to capture precisely such ‘bundles’.

Recently, varieties of this view of social life have also found adherents in political ecology and Paul Robbins’ textbook states ‘the central innovation of this way of thinking include the expansion of the polity and the number of parties to a quarrel, struggle, or a collaboration, as well as a continued stress on the dialectical relationship between elements of the world’ (Robbins Citation2019, 226). Robbins himself offers one of the most relevant discussions to our purpose in his book Lawn People (2007) discussing the agency of American lawns in shaping people’s subjectivities and broader political economy, revealing the possibility that humans are made into ‘lawn people’ acting out the needs of the lawn. While the lawn ‘is not the prime mover of such a system’ (Robbins Citation2007, 134), which overall amounts to the capitalist economy, the lawn is ‘an essential part’. In a recent example of more-than-human political ecology focusing on strawberry, Julie Guthman (Citation2019) takes some of these points further, arguing that ‘ecological dynamics’ and ‘political economic limitations’ actually ‘evolve in relation to one another and to human intervention’ (Guthman Citation2019, 25). Guthman’s study hones in on the ‘California strawberry assemblage’ by studying the ‘intra-action’ of three different kinds of actors: the growers and their embeddedness in agrarian political economy; the agricultural scientists and their guiding rationale and the multifarious nonhuman entities, materials, and forces (Guthman Citation2019, 11). The agency of the third group of actors (which includes, inter alia, hybrid strawberry varieties, soils and fumigants) is not understood as intentionality, ‘but rather an object’s capacity to produce an effect on another object’ (Guthman Citation2019, 17). We follow Guthman in her ‘ecumenical’ (18) approach to assemblage thinking, combining attention to ‘the material’ with attention to political and economic forces.

Our approach further draws on Anna Tsing (Citation2013) as a method for studying the social worlds of non-human beings: by paying attention to ‘form’ in addition to ‘assemblage’. While the above has presented our take on assemblage, the notion of ‘form’ entails, in discussing non-human sociality, that ‘form can be materialization of social relations’ and that ‘[t]heir form shows their biography; it is a history of social relations through which they have been shaped’ (Tsing Citation2013, 33). We understand form as encompassing Warman’s ‘botanical virtues’ of maize as a species (see next section), but also the diversity of maize varieties and their different ‘social’ features. In the book Care of the Species, the anthropologist John Hartigan pays in-depth attention to form. He lays out how his research on the place-based dynamics of ‘races of maize’ has made him break with the constructivist approach of ‘following the metaphor’ and rather take a ‘follow the species’ approach (Hartigan Citation2017, xxii). This is also what we do: we follow the maize species, in its diverse varietal forms, into a study of the history and agrarian political economy of the maize assemblage. In the next section, we follow maize into the social science literary landscape. Subsequently, we follow the species into farmers’ fields and the agro-food systems in Malawi and India.

3. The Agrarian political economy of maize revisited

Without maize, the social world of humans would have looked differently. A pioneering contribution to the historical anthropology of the capitalist world-system in the tradition of scholars such as Eric Wolf and Sidney Mintz, Arturo Warman’s Corn & Capitalism results from the author’s deep and encyclopedic research into the maize crop, undertaken with what he describes as a scholar’s ‘uncontrollable passion’ (Warman, x). Warman describes in great detail ‘a series of case studies on corn’s role in the formation of the world system, nothing less than a world history of corn’ (Warman Citation[1988] 2003, x).Footnote2 While heavily influenced by Marxian political economy, Corn & Capitalism is also simultaneously a work of environmental history in its recognition of ecological traits intertwined with social change. The book thus joins ranks with earlier works such as Crosby’s (Citation1972) on the ‘Columbian exchange’ with its socio-ecological implications of crops and diseases; and, also, Braudel’s (Citation1977, 107) notion of maize as one of the three ‘plants of civilization’ together with wheat and rice.

Before elaborating on this world history of maize, however, Warman spends an extended time describing the ‘botanical virtues’ of the crop. In so doing, he highlights the multiple uses of maize as food, feed, fuel and, later, industrial starch (and more), anticipating the recent scholarly attention to ‘flex crops’ (Borras et al. Citation2016). This flexible nature of the crop, Warman writes, means that ‘corn has a special distinction with respect to the other cereals: corn’s full and complete incorporation into the industrial era and into modern capitalism’ (Warman, 26). Combining the ‘form’ of the crop with the ‘assemblage’ of global capitalism, as it were, yet in conceptual terms of his day.

Stressing the role of maize in helping to catalyze the possibilities for the capitalist world-system, Warman proceeds to show the key role of the crop in processes of colonization – both of people and of environments – while simultaneously embedding his descriptions in holistically rich detail about social structures, local histories and ecological conditions. Warman thus provides a grand tour of world-historical change starting with the conquest of the so-called ‘New World’ and the migration of the crop across the ‘Old World’, transforming consumption and agrarian patterns. Moving onwards, Warman elaborates on the key role of maize in slavery, revealing the importance of the crop’s particular traits to the operations of the slave trade and colonialism in Africa, where the crop-fed workers building colonial infrastructures and laboring in colonial extractive industries. This draws Warman to explore continuities into the postcolonial era in Africa by focusing on the role of maize to subsequent dependency relations. The book goes on to describe the role of maize in the agricultural revolution in Europe and its ensuing industrialization and urbanization, stressing the crop’s relation to poverty and exploitation, before it moves back to the ‘New World’ and the key role of maize to the emergence of the United States and its specific agrarian patterns, food habits, slavery and the industrialization of agriculture. This leads, finally, Warman to discuss the emergence of the globalized food system centered on the power of the US in maize trade relations, pushed forward by US agrarian imperialism and, increasingly by the middle of the twentieth century, meat-centered production systems and diets along uneven patterns of development.

Warman’s book thus ends at the onset of patterns of agri-food globalization that we have since then come to know as the ‘corporate food regime’ (McMichael Citation2013) centered on massive agribusiness dominance.Footnote3 In this latest phase of agri-food globalization, maize has multiple uses as a key flex crop, yet it is clear, Winders (Citation2017) emphasizes, that its use as animal feed has been central to its continued expansion – which we will get back to below. As human diets have become increasingly focused on meat over the last few decades, we find that maize has become even more central to global trade and cropping patterns as a key source of feed for livestock in the ‘industrial grain-oilseed-livestock complex’ (Weis Citation2013), which is currently spreading rapidly across the world (see Jakobsen and Hansen Citation2020). Within this ‘complex’, the combined effects of transnational meat corporations’ influence and state policies have facilitated for imperial dynamics in global trade flows in maize as livestock feed (see Howard Citation2019).

While this cursory overview of Warman’s narrative may give the impression of focusing primarily on the effects of maize on society, the book sees this history as one where humans and the maize crop have domesticated each other, mutually, in co-evolutionary ways as illustrated by the opening quote of this article. Although Warman, we may say, did not have conceptual vocabulary for analyzing more-than-human entanglements beyond this point, we find that other work published about the time of his book (but not available at the time of its writing) did take things further in such a direction. This is particularly clear in scholarship on the role played by hybrid breeding in the shaping of the maize seed industry written at the same time as Warman’s book. Warman (185) does of course duly acknowledge the importance of hybrid breeding at the interplay between the plant’s characteristics (‘form’) and crop science, private capital and farmers’ practices (‘assemblage’), yet more sustained investigations are found elsewhere, pushing further into the more-than-human.

Maize features as a central element in Kloppenburg’s (Citation1988) First the Seed. ‘The natural characteristics of the seed’, writes Kloppenburg (Citation[1988] 2004, 71), ‘constitute a biological barrier to its commodification’ due to ‘its natural reproducibility’. A key way for capital to overcome this limitation is through science, which happened first with hybrid breeding of maize. Hybrid breeding, simply explained, is the development of uniform new varieties by crossing genetically homozygotic (inbred) parent lines. Such crosses, which can be done once or followed by several consecutive rounds of backcrossing, result in high yielding and vigorous offspring, an effect known as ‘hybrid vigor’ or ‘heterosis’. The uniformity of the offspring (the F1) breaks down in subsequent generations if seeds are saved from randomly cross-pollinated cobs in the field, leading to loss of the hybrid vigor effect. Thus plant-back of seeds from the first high yielding generation will give considerably lower yield, resulting in a ‘yield penalty’ for a seed saving farmer. Thereby, the rise of hybrid breeding, first in the US and since spreading around the world, enabled a type of control over the new varieties on the side of the breeder that conventional population breeding could not. Kloppenburg’s account proceeds to reveal how this hybrid ‘form’ enrolled in broader ‘assemblages’ also involving legal protection of new varieties through intellectual property rights (IPR) further enabling capital accumulation for the private seed industry. While plant breeding was primarily a public, state driven domain at the initial stage of hybrid breeding in the US in 1935, this assemblage changed into being private capital driven.

What was produced through hybrid breeding was, as Berlan and Lewontin (Citation1986) put it, ‘an extraordinarily profitable commodity’. Lewontin, a merited evolutionary biologist, came to this view of hybrid breeding on scientific grounds; conventional population breeding was also making great yield progress, but hybrid breeding had the added advantage that it provided the breeder with a de-facto biological patent. Hybrid maize eventually became ‘the very lifeblood of the seed industry’ (Kloppenburg Citation1988/2004, 93), expanding even further into the present phase of the corporate food regime and the globalized seed industry where hybrid breeding is combined with transgenesis (popularly known as genetic modification), leading to extended struggles and controversies (see Fitting Citation2011). The trajectory laid out by Warman made Michael Pollan (Citation2009) call maize a ‘protocapitalist’ crop. According to Betty Fussell, the ‘translation’ of maize into ‘corn’ was the beginning of a commodification process resulting in full-fledged corn capitalisms with the establishment of seed companies like Henry A. Wallace’s Pioneer Hi-Bred: ‘By applying the principles of mass production and distribution to the plant world, Wallace turned agriculture into business and the landscape of the Midwest into an endless corn factory’ (Fussell Citation1999, 56). In the same vein, relating to Warman, James McCann (Citation2005) traced maize’s trajectory in Africa, stating that ‘modern genetic alchemy has transformed maize from an obligingly adaptive vegetable crop to a hegemonic leviathan that dominates diets and international grain markets’ (McCann Citation2005, 21). We see in the making of maize into such a ‘hegemonic leviathan’ the notion of the double internality ‘as capital’s internalization of nature, and as nature’s internalization of capital’ (Moore Citation2015, 30).

Agrarian political economy and environmental history, as represented by the scholarship presented so far and conjoined in Warman’s work, thus foreshadow the more-than-human ‘turn’ more recently. Environmental history has, as its trademark, a concern for nature that does not merely approach it as ‘container’ or ‘landscape’ but actively co-constituting social or socioecological worlds (see Moore Citation2015). Similarly, ‘agrarian political economy’s central departure from classical political economy’, writes Guthman, ‘is its attention to the difference nature makes in agricultural production, distinct from in manufacturing, and how those differences create particular challenges for growers’ (Guthman Citation2019, 12). Drawing classical work in this tradition on the role of maize in global capitalism into the ongoing conversation around more-than-human political ecology enables us to see continuity in scholarly interests. The notion of the imperial maize assemblage brings this continuity into view, yet follows recent work in making the recalcitrance and agency of the maize plant more central to our analysis. The next section proceeds to exploring this perspective empirically in Malawi and India.

4. Maize in contemporary agro-food systems

In Latin America, where maize originated, there are several cultural groups that refer to themselves as the ‘people of maize’ (Blake Citation2015).Footnote4 Extending this notion, we would argue that ever more humans are turning into ‘maize people’. From sustaining pre-historic American cultures, maize has today become the world’s most-produced crop, and it is among the crops that have increased the most over the six decades for which international crop production statistics are available (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Citation2021). This massive increase rests on a bifurcated pattern of uses: In the Global North, most of the maize produced is for animal feed or industrial use, whereas most of the maize produced in the Global South is consumed as human food. This trend is visible in all regions and the two regions of our case countries – Southern Africa and South Asia – are among the regions with the largest production increase.

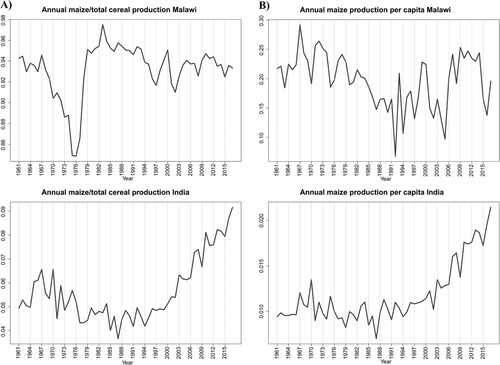

Maize has for decades been the dominant staple in Malawi, representing more than 90% of the cereal production, fluctuating between 100–250 kg produced per capita according to official statistics and FAO estimates (). Maize yields varies from good and bad cropping seasons, but the share of maize in land use and in diets remains largely the same as when Smale and Jayne estimated that 75 percent of the crop cereal area was planted to maize and that more than 50 percent of the calories consumed in Malawi comes from the crop (Smale and Jayne Citation2003). The importance of maize in Malawi today is expressed in the Chewa proverb ‘Chimanga ndi moyo’ – ‘Maize is life’. Malawi thus exemplifies a pattern typical of countries in the South where maize has become tightly integrated with dietary, cultural and economic patterns.

Figure 1. Maize production in Malawi and India 1961-2017. (A) Share of maize production of total cereal production. (B) Per capita maize production in tonnes. Data sources: FAOSTAT and WB.

Source: Crop production data from FAOSTAT http://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#home. Population data from World Bank https://data.worldbank.org/indicator/SP.POP.TOTL

In India, maize is (still) a much less central crop accounting for less than 10% of the total cereal production which in the top year 2017 was a little more than 21 kg per capita (). However, the production of maize is rapidly increasing, far outpacing the increase in other staple grains (Jakobsen Citation2020), and maize is now considered the third most important ‘food grain’ after wheat and rice. From 1990 to 2016, the area harvested for maize in the country increased by more than 70 percent. In the same period, total production of maize increased by more than 190 percent (Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations Citation2021). Reports indicate that 15 million farmers in the country grow maize (FICCI/PWC Citation2018). The designator ‘food crop’ may be misleading, though: 60 percent of the Indian production is grown for feed, 13 percent for food and the rest goes into processed food and starch (Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry Citation2018). As Winders (Citation2017) and Jakobsen (Citation2020) point out, the rise in production and acreage for maize in this period is part of the broader rise of the industrial grain-oilseed-livestock complex in the country, with maize featuring centrally as feed. Indeed, one industry report holds that as much as 47 percent of maize in the country is used for poultry feed, while 13 percent goes to other livestock (FICCI Citation2018). Maize in India in other words exemplifies a pattern more typical of countries in the ‘North’ where maize features as an industrial crop.

4.1. The influence of form

Warman’s account of the botanical virtues of maize follows the ‘six major qualities’ of the crop listed by the Sevillian doctor Juan Cardenas in his 1591 chronicles: (1) Enormous diversity of adaptations and varieties across a wide range of environments; (2) Exceptionally high yields; (3) Easy crop management; (4) High food quality even before the cob matures; (5) Diverse use of the different plant parts; (6) Diversity in food products. These virtues are central properties in our notion of ‘form’. Our exploration of the trajectory of maize in the agro-food systems in Malawi and India thus pays particular attention to these aspects of ‘form’.

It was only a subset of the enormous diversity of maize that reached the Old World, but it did not take long to diversify. The spread of maize is documented in archaeological, historical and genetic research (McCann Citation2005; Westengen et al. Citation2012; Mir et al. Citation2013). The first maize crossed the Atlantic already in 1493 when Columbus returned to Spain from the Caribbean. This tropical lowland maize spread along Arabic trade routes across North Africa and subsequently into East Africa and the Indian sub-continent (McCann Citation2005; Mir et al. Citation2013). Another early maize port in Africa was the Sao Tome island in the Gulf of Guinea where Northern South American maize varieties piggybacked with the Portuguese slave trade as early as 1534 (Mir et al. Citation2013). On top of these early layers of maize genetic traces maize’s diversity virtue has created a complex pattern in the Old World: ‘Repeated introductions, local selection and adaptation, a highly diverse genepool and outcrossing nature, and global trade in maize led to difficulty understanding exactly where the diversity of many of the local maize landraces originated’ (Mir et al. Citation2013, 2671).

4.1.1. Malawi

The role of maize’s form in Malawi can be understood through four binaries: maize vs. sorghum and millet; local maize varieties vs. improved varieties; flint varieties vs. dent varieties; Open Pollinated Varieties (OPVs) vs. hybrid varieties. The first of these binaries can be explained by the botanical virtues of maize as a species whereas the others require a deeper look at the diversity at the intraspecific level.

In Malawi, maize in earnest started to replace the African indigenous grains sorghum and millet in the beginning of the twentieth century, a process that was intertwined with the colonial economic and social system (Bezner Kerr Citation2014; Smale Citation1995). Colonial Malawi, Nyasaland, was not a settler economy like those in Kenya, Zimbabwe and Zambia which had valuable minerals and areas with more benign ecological living conditions for a European population vulnerable to malaria so widespread in the lowlands. Nyasaland was rather known as an exporter of labor to mines in other countries and following the stagnation of the British plantation economy, the colonial economic system shifted to emphasize smallholder production of export crops like coffee, tobacco, tea and cotton (Smale Citation1995). Maize’s botanical virtue of easy crop management made it particularly suited for subsistence crop production in this economy characterized by male migration and cash crop production (Bezner Kerr Citation2013; Smale Citation1995). A concrete example of this virtue is that maize does not require labor for chasing off birds from the fields like sorghum and finger millet does (Bezner Kerr Citation2014).

The role of maize as a subsistence crop for a primarily rural smallholder population in the colonial period is key to understand the importance also of the local vs. improved aspect of maize form in Malawi. While the colonial agricultural research apparatus in many other African countries early on started importing and developing improved varieties to be used in large scale production of cheap calories for the mining and plantation workers, plant science in Nyasaland paid relatively little attention to maize, which remained primarily a crop all smallholders produced for own consumption. As a result, Malawian smallholders continued growing local varieties of flint maize – a type of maize with high hard starch content descending from varieties cultivated by native Americans on the Great Plains (Mir et al. Citation2013). Malawian smallholders developed a milling and processing strategy that was suitable for the hard-seeded flints, producing a white flour with an aroma and texture which up to this day is preferred for making the Malawian staple food nsima – maize porridge (Kydd Citation1989; Smale Citation1995). The flinty varieties preferred for making flour for nsima are commonly referred to as chimanga cha makola – local maize.

When the new Malawian breeding program established in 1954 emulated the breeding programs in other African countries and concentrated on developing dent-hybrids, varieties with high soft starch content ideal for large-scale milling, they found very little interest among smallholders. Not only did the dents taste less, but they were also not as well suited to the local processing methods, a complex process of de-hulling, bran treatment, soaking/fermentation and milling (Kydd Citation1989). An additional benefit with the flint form was the superior storing qualities; while the dents are easily devoured by maize weevil (Sitophilus zeamais), the hard pericarp of the flints provide somewhat better protection. This is up to this day an important character for smallholders who typically store their grain and seed on farm. The failure of formal agricultural research to recognize and address the importance of farmers’ dietary, storage and processing preferences in regard to their key staple, has long been recognized by scholars as a potential explanation for the low uptake and adoption of improved maize that long persisted in Malawi (Ellis Citation1959; Kydd Citation1989; Lunduka, Fisher, and Snapp Citation2012; Smale Citation1995).

The release in 1990 of the first semi-flint hybrid maize varieties by the public breeding programs seems to have been a game-changer (Smale Citation1995). The ‘anti-commodity’ flint form had finally been married with the commercial dent form allowing for a belated hybrid maize based ‘green revolution’ in Malawi (Smale and Jayne Citation2003). The use of hybrid maize in Malawi has indeed increased considerably in the last three decades (Haug and Wold Citation2017), but as we shall see in the assemblage discussion, this success of the hybrid form over the local and improved OPVs is at least as much a result of political control and structural adjustment reform as of the virtue of the form itself. The perhaps most remarkable expression of the importance of form is the persistence of flinty local OPVs up to this date. The explanation for this phenomena which Kydd called the ‘Malawian syndrome’ (Kydd Citation1989, 118) is still at least partly farmers’ preferences and their close ties with chimanga cha makola (Lunduka, Fisher, and Snapp Citation2012). Following Tsing, the flint form is a ‘materialization of social relations’ (Tsing Citation2013).

4.1.2. India

Tracing form in India displays a distinctly dual pattern. First, there are certain hilly, remote and largely tribal (adivasi) inhabited tracts (particularly in the Northeastern Himalayan area) known for their high diversity in flint maize landraces, with maize strongly incorporated in local dietary patterns. This was recognized by researchers in the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), reporting of tribal tracts in the Himalayas, Gujarat and Rajasthan that

exclusively depend on maize as the chief source of energy. In these regions, crops other than maize would probably give better yields; but the local population has a decided preference for maize, probably because of their long association with it. (Singh Citation1977, 6)

Second, there are ‘new’ maize cultivating areas where maize has never been part of traditional dietary or cultural patterns, focused on South India, which presently grow maize as an industrial flex crop in proximity to the country’s major centers of poultry production, including Karnataka, Telangana and Tamil Nadu. These parts – which comprise of highly diverse agro-ecological conditions in accordance with Warman’s first virtue – have become highly dependent on hybrid maize with 90 percent or more of the maize acreage under hybrids (as much as 98 percent hybrid in the highest producing states of Andhra Pradesh/Telangana and Karnataka), whereas the degree of hybrid adoption in the ‘traditional’ regions remains lower, at 30 percent in many of them (Pavithra Citation2018). It is in these new areas that the maize acreage has been increasing rapidly, especially since around the year 2000. The ‘old’ areas, meanwhile, have seen slow or even negative growth rates in area harvested (Kumar, Srinivas, and Sivaramane Citation2013). While maize in India is primarily a summer/monsoon (kharif) crop, improved varieties have also started being grown as a winter (rabi) crop, thus increasing the potential for annual yields substantially.

This dual macro-pattern clearly reveals the centrality of form to the trajectory of maize in India. Descending to the micro-level, ethnographic research in rural Karnataka finds smallholders changing their cropping patterns in semi-arid, drought-prone regions, revealing how proprietary varieties of hybrid maize are integrated in livelihoods (see Jakobsen Citation2020). To summarize, fieldwork reveals several of the botanical virtues of maize assuming central importance: the rapid growth of the crop and the relatively low labor requirements enables smallholders dependent on monetary income from wage labor outside of their fields to ‘free’ themselves from agriculture for much of the year, while maintaining agricultural activity on their marginal lands. Maize, farmers explained, is an ‘easy’ crop – easier than competing crops available to them, a statement that resonates with Braudel’s (Citation1977, 12) emphasis on maize as an especially ‘convenient’ crop for peasants. Not only ‘easy’ in terms of labor and time, but the crop’s lower water requirements were also key to farmers on ecologically fragile soils. Key was also the diverse uses enabling farmers to utilize the entire maize plant in feeding their livestock and, finally, the ability of the maize plant to be intercropped. These qualities, in other words, were instrumental in making humans grow hybrid maize in southern India.

While the maize form is thus actively drawing people in, driving the crop into ever more farmers’ fields, the maize assemblage is also actively shaping this trajectory. It is to this we turn next.

4.2. Tracing the imperial maize assemblage

Maize needs companions and different forms of maize require different types of companionships. The hybrid form of modern maize requires close attention both by breeders and their institutions (public and private) and by farmers: new seeds must be produced under highly controlled conditions, sold and purchased every growing season.Footnote5 In this section we study the history and current make-up of the maize assemblages in our two case study countries.

4.2.1 Malawi

When Malawi gained independence in 1964, the new government prioritized the agricultural sector. That did not, however, mean greater priority to research for smallholder agriculture, but rather priority to large-scale estate-based agriculture of export crops, most notably tobacco (Harrigan Citation2003; Kydd and Christiansen Citation1982). Thus the neglect and ignorance shown towards smallholders’ flint maize during the colonial times prevailed in the post-independence public agricultural research system. This changed in 1987 when plant breeder B.T. Zambezi, aided with access to genetic resources from the newly established International Maize and Wheat Improvement Centre (CIMMYT) research station in Zimbabwe, initiated a breeding program focusing on flint maize. For the first time since early colonial breeding, farmers’ grain texture preference became a breeding objective (Smale Citation1995). The new semi-flint hybrids such as the MH-18 variety were marketed by the National Seed Company of Malawi (NSCM) and the smallholder maize area growing hybrids rose from 7 to 24 per cent between 1988 and 1992. This was not only driven by the popularity of the new varieties but also the more aggressive marketing strategy of a privatized NSCM which the state in 1990 sold to Cargil (Smale Citation1995). Malawi’s post-independence dictator, H. K. Banda, ‘President for life’, further aided the hybrid maize revolution by fixing the grain board Agricultural Development and Marketing Corporation (ADMARC) maize price at a high level and by subsidizing fertilizer inputs (Harrigan Citation2003).

The constellation of hybrid maize, private seed companies and government subsidies was the beginning of a maize assemblage that became even more powerful after transition to democratic elections in 1994. The new government was reliant on donors for foreign exchange and continued the former regime’s liberalization reforms. In agriculture that meant, among other things, restricting ADMARC’s role in both input and output marketing. By 1997, 75% of hybrid seed and 70% of fertilizer was sold by commercial entities (Harrigan Citation2003). In the same period, NCSM had been sold on from Cargil to Monsanto and several multinational companies had established themselves in the Malawian input market (Bezner Kerr Citation2013; Chinsinga Citation2011). According to Harrigan (Citation2003), Malawian food and agriculture policy development in the second half of the 1990s was characterized by a schism between the World Bank and the Malawian government: ‘the Government reverting to a more interventionist stance and the Bank for its part advocating input and credit subsidy removal, food imports and state minimalism’ (Harrigan Citation2003, 860). In 2002, a drought triggered the worst famine in Malawi’s recorded history (Devereux Citation2002). Since the reign of Banda, the legitimacy of the government in Malawi had been closely associated with domestic availability of maize and the famine therefore had much political potency. In the election in 2004, Bingu wa Mutharika won with a manifesto promising maize-based food security and in the 2005/2006 season he delivered on his promise by rolling out an input subsidy program at an unprecedented scale (Dorward and Chirwa Citation2011). The Farming Input Subsidy Program (FISP), which the input subsidy program is known as today, has varied in content and scope from season to season, but the core approach has remained the same; vouchers for a certain volume of fertilizer and improved seeds are distributed to a large proportion of the rural Malawian population. In a typical year the FISP has targeted 50% of the farm households with 50–100 kg of fertilizer and 5–8 kg of improved maize, and in the latter years a smaller amount of legume seeds. The cost of FISP has also varied, but in several seasons the program has accounted for more than 70% of the public budget to agriculture and more than 15% of the total national budget (Dorward and Chirwa Citation2011; Haug and Wold Citation2017).

The magnitude of FISP and the contestations surrounding it has made it a poster child in the international debates over the role of domestic food production for food security in general and the role of subsidies in developing countries in particular. This debate plays out both in the media and in a scholarly literature spanning several disciplines, including agronomy, economy, political science and anthropology (Banik and Chasukwa Citation2019; Chinsinga and Poulton Citation2014; Denning et al. Citation2009; Dorward and Chirwa Citation2011; Haug and Wold Citation2017; Messina, Peter, and Snapp Citation2017; Mzamu Citation2012; Ricker-Gilbert, Jayne, and Shively Citation2013; Smale, Byerlee, and Jayne Citation2013). Unsurprisingly, the views on the programs’ impacts depend on the disciplinary perspective and the outcomes considered, but a fault line in the debate has since the beginning been between those considering FISP a bold political program for social protection and national food security and those considering it as a political tool used by the government and other actors for patronage and power consolidation.

Employing our analytical lens of form and assemblage, FISP is an interesting articulation of the contemporary imperial maize assemblage. The three main groups of actors identified by Guthman (Citation2019) (growers, scientists and non-human actors) all play significant roles in this assemblage in addition to various other political and economic actors. Most research on FISP has focused on understanding the role of politicians, donors and private input suppliers. Malawian politicians, and particularly the vocal Bingu wa Mutharika holding the presidency from 2004 until his death in 2012, are often portrayed as the most central actors in shaping the system. The strong agency displayed by the president when going against the World Bank and other leading donors’ recommendations when establishing FISP and promoting state interventionism earned him fame on the international policy scene as well as political power at home (Dorward and Chirwa Citation2011; Sachs Citation2012). Indeed, the tension between the donors (who play an important role in Malawian economy with as much as 40% of the national budget coming from foreign aid) has continued up to this day and FISP is still implemented in spite of, rather than because of, donor recommendations.

However, the history of FISP is more complex than what is conveyed in narratives about a strong president taking national control. Although the government strengthened ADMARC as a ‘Limited liability company’ under de-facto state control, private sector assumed a larger role in the agri-food system with FISP and the Malawian seed system legislations are today among the most commercially oriented on the African continent (Westengen et al. Citation2019). An international index of seed companies listed 11 companies in Malawi in 2019 (Access to Seeds Foundation Citation2019), but there are also others supplying seeds under FISP. Among companies operating in Malawi there are national companies such as Demeter and Peacock, but the lion’s share of the market is covered by multinational companies including Bayer/Monsanto, Chem China/Syngenta, Pannar, Seed Co and Pioneer Hi-Bred (now part of Corteva Agriscience). These companies embody aspects of both scientists and growers as they both breed new varieties and organize the production of seeds for sale. Their role as scientists varies from doing minor adaptation of breeding lines acquired from CIMMYT before release to having full in-house breeding programs. The trend in the relative contribution of public vs private breeding in Malawi mirrors the development described in Kloppenburg’s analysis of the trend in this relationship in the US seed market in the early twentieth century: Public breeding has been weakened and private actors now dominate. According to Chinsinga (Citation2011) this is partly a result of low funding and poor performance of the public system, but also the power exercised by the seed industry through Seed Traders Association of Malawi (STAM):

The crumbling of the public sector breeding programs has meant that the country has become almost entirely dependent on multinational seed companies for the bulk of improved seed supply, although not necessarily of the ideal quality for the local agronomic conditions. (Chinsinga Citation2011, 62)

The form and assemblage of maize has had an illuminating coevolution under FISP: In the first year of Bingu’s input subsidy program all the improved seeds distributed were OPVs, but this changed the very next year and by 2009/2010 hybrids made out 88% of the maize distributed (Dorward and Chirwa Citation2011). In the 2014/15 season, 94% of the seed voucher redemptions were for hybrids while only 6% were for OPVs (Chirwa et al. Citation2016, 24). This is also reflected in Haug and Wold’s analysis of production data which shows that local maize production has declined while OPVs and hybrids have increased in the period, with hybrids increasing by far the most since FISP started in 2005 (Haug and Wold Citation2017). Interestingly, the hybrid maize use seems to be more precarious and dependent on the other actors in the assemblage than what is conveyed in the use of the term ‘adoption’ in econometric studies. In the 2015/16 season, when international donors who had funded the entire seed component in FISP withdrew their support, farmers had to contribute 1000 MK as a ‘top up’ for the 5 kg bags of hybrid seeds (compared to 100 MK the year before). As a consequence ‘adoption’ immediately fell from 57% to 48% of the households (Chirwa et al. Citation2016). As a director of a national seed company put it in an interview: ‘Adoption is about conviction. You know, we are working against the traditional farming’.Footnote6 He went on to explain that there is a need for extension to teach farmers about the benefits of hybrid varieties, but also that it is a question of affordability and that about 80% of the improved seed use in Malawi is acquired ‘through FISP’. The materialization of social relations seen in the relationship between peasants and chimanga cha makola thus still represents a resistance to peasants’ full enrollment in the imperial maize assemblage in Malawi. It takes massive efforts from the state and capital to ‘make the market work’ for hybrid maize. The informant quoted above was both a seed company owner and a member of the parliament – illustrating the entanglement of hybrid maize with economic and political power in the country. An interesting historical parallel in the US is the mentioned Henry A. Wallace; not only was he the founder of Pioneer Hi-Bred, he was also the 11th Secretary of Agriculture and the 33rd vice president of the USA and played an important role in setting off the Green Revolution (Patel Citation2013).

An account of non-human actors in the Malawian maize assemblage must in addition to maize include fertilizer, herbicide and climate change including extreme weather events. Frequent floods and droughts directly impact domestic maize production, but also indirectly through the governments’ responses. As described, drought and the ensuing failure of the government to prevent famine in 2002 is important to understand Bingu’s victory with a promise to ensure food security in the election that followed. Favorable climatic conditions in the first seasons with the revamped inputs subsidy program are also an important factor for explaining the success in boosting maize production to unprecedented levels in the country. Another non-human actor of great importance is mineral fertilizer. The largest share of the FISP budget is spent towards the fertilizer component, and the yield benefits of hybrid maize can only be exploited when cultivated with the recommended volume of fertilizer (Denning et al. Citation2009; Dorward and Chirwa Citation2011). In later years, climate change has become an important part of the rhetoric – stressing urgency and necessity – for further commercial modernization in Malawian agriculture in general and in seed policy formulation is particular (Chinsinga and Chasukwa Citation2018; Westengen et al. Citation2019). Climate change has thus spurred a business of ‘repair’ – ‘work of maintaining a system in the face of constant change – and sometimes crisis’ (Guthman Citation2019, 16). The paradoxical outcome is that climate change, which is shown to affect maize production more negatively than most other crops, (Challinor et al. Citation2014; Tigchelaar et al. Citation2018) is used as a rationale for intensifying breeding and efforts to boost commercial formal maize seed system development.

4.2.2 India

The development of hybrids in India started in the 1950s under the auspices of the Indian Council of Agricultural Research in collaboration with the Rockefeller Foundation, organized as the All India Coordinated Maize Improvement Project (renamed the Directorate of Maize Research in 1994), with maize as the first released hybrid crop in the country in 1961 (Pandey Citation1994). This early focus on maize happened despite maize only comprising 3 percent of India’s gross cropped area in the 1950s (Lele and Goldsmith Citation1989; Roy Citation2006). However, this initial public concentration on maize was somewhat sidetracked as state priorities came to focus on wheat and, later, rice, in the Green Revolution (Patel Citation2013). Still, the public efforts at maize hybrid breeding – both single and double cross – did continue and advance in the 1960s and 1970s, under a policy regime that protected the domestic seed sector (see Pray and Ramaswami Citation1999), after the establishment of the CIMMYT and a national seed industry spearheaded by the National Seeds Corporation and the States Farms Corporation of India Limited with collaboration with state agricultural universities.Footnote7 These efforts were supported by World Bank loans (Jafri Citation2018) and were clearly tightly linked to the US’ geopolitical project in the Green Revolution (Cullather Citation2010). This was the establishment, in other words, of the formal seed system in the country – and maize was at the forefront.

The subsequent neoliberal transformation of the Indian state and economy starting in the late 1980s reveals the maize actor entering a reconfigured assemblage. While the first hybrids released in India were produced by public sector breeding programs, the Indian seed market was liberalized starting in the late 1980s, leading to massive influx of private companies (both domestic and multinational), while public agencies saw ‘their territories invaded’ as one assessment from the late 1990s held it (Morris, Singh, and Pal Citation1998, 56). The World Bank was involved in these processes as well, providing loans to private sector initiatives in the seed sector (Jafri Citation2018), and like we saw in Malawi above, this turn to private investments was clearly part of a broader discursive shift towards neoliberalism where ‘expediency’ increasingly came to be seen as necessitating the disruption of public dominance in India’s agro-food system (Jakobsen Citation2019). Again, maize was at the forefront of pushing the liberalization of the seed market in the country: ‘Although they applied to all crops, the seed industry reforms introduced during the late 1980s had an especially noticeable impact on maize’ (Morris, Singh, and Pal Citation1998, 57). Opening up for private companies did not, however, mean that the previous public-driven assemblage pulled entirely back, and there remained substantial public investment in maize research, as well as research undertaken in collaboration with CIMMYT, while private companies came to focus research interest in plant-breeding, sometimes drawing on publicly developed germplasms (Morris, Singh, and Pal Citation1998, 59–61). Put differently, the emergence of a strong private sector in the maize sector was only possible by drawing on prior – and continuous – foundation and support from public sector initiatives (Morris, Singh, and Pal Citation1998). Yet, as was observed in the late 1990s, there was a process underway of decreasing importance for public sector agencies in the hybrid seed market, which became increasingly dominated by private companies (Shiva and Tom Citation1998).

Over the last couple of decades, however, it appears clear that the private seed sector has gained prominence. This has entailed that private sector hybrid seeds predominate in the ‘new’ maize growing regions (Pavithra Citation2018), leading a recent assessment to hold that: ‘The results imply that private sector maize varieties are dominating in those states where maize is mainly cultivated varieties and hybrids for commercial purpose such as feed and other industrial uses’ (Pavithra Citation2018, 395). This ‘division of labor’ is clearly based on the drive for capital accumulation: ‘Public sector mainly targets less-endowed environments particularly the rainfed ecology where maize crop encounters more risks, whereas private sector focuses on better-endowed environments having higher productivity potential and assured seed marketing’ (Yadav et al. Citation2015, 328).

In 2013, it was reported that the country housed ‘more than 500 private seed companies operating at different levels’ (Kumar, Srinivas, and Sivaramane Citation2013, 57). The same report held that five companies controlled 58 percent of the market in seeds. These companies include Dupont Pioneer (now Corteva Agriscience), Dekalb (a subsidiary of Monsanto/Bayer) and Syngenta – in other words three of the ‘Big Six’ of world-leading agribusinesses controlling 60 percent of the global seed market (IPES-FOOD Citation2017).Footnote8 Overall, the Indian seed industry grows rapidly, reported to comprise a share of 4 percent of the global seed market, driven especially by Bt cotton hybrids, maize hybrids and vegetable hybrids (Indian Council of Food and Agriculture Citation2015). Although data on private sector seed varieties remains insufficient, it was estimated in 2018 that India has seen the introduction of 369 hybrid maize varieties (Pavithra Citation2018, 395). The drive for using maize as an industrial flex crop comes to the fore, moreover, in choice of plant varieties for improvement; while both yellow flint and dent have been subject of improvement, there has lately been a shift towards the latter ‘because of its amenability in industrial processing’ (Kaul et al. Citation2018, 937).

It is therefore clearly the case that ‘the push is from the private sector’, as one high-ranking agricultural department official said in an interview, before he went on to say that this private sector drive is also complemented by state policies towards crop diversification away from paddy and wheat.Footnote9 ‘Diversification’ indicates that state priorities in maize have come to center on the crop’s usefulness in overcoming the mounting challenges of environmental and soil degradation following heavily chemicalized industrial agriculture in the Green Revolution heartlands and increasingly erratic rain. State agencies thus consider that ‘Developing hybrids of suitable maturity and for marginal lands for unpredictable monsoon are the major challenges in breeding of maize’ (Ministry of Environment and Forests Citation2011, 15).Footnote10 In other words, maize is becoming an increasingly central crop to state attempts at so-called ‘climate smart’ agriculture, frequently entailing a focus on technocratic production-side issues rather than questions of power, inequality and access in agrarian systems (Taylor Citation2018). Yet, the non-human actors in the maize assemblage may be less faithful to these ambitions. Since 2018, the fall armyworm (Spodoptera frugiperda) insect pest has ravaged India’s maize fields, as it has done across the world since its first appearance in West and Central Africa in 2016 (Goergen et al. Citation2016). The pest not only reveals some of the fragility of the maize assemblage, but strikingly exposes the dialectics of maize in the web of life: maize is suddenly not the colonizing agent but, to the contrary, the victim of an uninvited invasive companion species.Footnote11

While this fragility is real, in India the imperial maize assemblage has, as indicated above, expanded in cohort with a seemingly resilient ally: the meat industry or, more precisely, the industrial grain-oilseed-livestock complex. Claims about linking maize to climate concerns remain much less central than its role in the industrial grain-oilseed-livestock complex in the country where, as we have seen, around 60 percent of the maize ends up. This is an industrial usage that not only feeds domestic livestock but is increasingly tied to foreign markets through expansionary feed trade, especially with Southeast Asian countries (Jakobsen and Hansen Citation2020). While we have pointed to the poultry sector as a key recipient of feed flows (see Jakobsen Citation2020), there is also the impact of Indian beef exports that have expanded at a rapid pace for the last decade, making India into one of the world’s largest exporters of meat. The rising acreage of maize as well as soybean – as feedgrains that increasingly displace foodgrains in a country facing strong food insecurity – must first and foremost be seen in the context of these dynamics set within the industrial grain-oilseed-livestock complex (see Winders Citation2017). It is as part of this assemblage, we argue, that maize is currently fronted as a crop of the future for the country. The Federation of Indian Chambers of Commerce and Industry (FICCI) – the country’s leading business organization – for example, holds that maize represents ‘vistas of opportunity’, leading them to support a stated goal of doubling maize production in the country by 2022/25 (FICCI/PWC Citation2018). India’s agriculture minister has similarly talked about the need to double maize production in India (Sen Citation2016), as has CIMMYT (Citation2015), as well as ICAR researchers (Yadav et al. Citation2016). The imperial maize assemblage is in India set on expansion.

5. Maize dialectics

Corn represented a way of life and an organization of production that tolerated exploitation and dispossession well. Corn, however, never necessarily implied or required such burdens. (Warman Citation[1988] 2003, 21)

Yet, we do not see maize dialectics as deterministic with the imperial maize assemblage as the necessary end point for the human-maize relationship. As Warman clearly recognized, maize’s intertwinement with capitalist despoliation is not ‘required’ by the plant itself. Maize, we suggest, have also recruited significant others to form what we may think of as ‘resistance assemblages’. Maize landraces and other OPVs are still governed as commons in peasant economies around the world, in some cases in explicit opposition to commodification but in most cases as continuation of customary practices governed by local institutions. The Mexican social movement Sin Maíz No Hay País (Without Maize There is No Country) is arguably an example of an explicit maize resistance assemblage. This movement has been central in the protests against the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA), using the agreement’s adverse impacts on campesino maize production as a rallying point (Fitting Citation2011; Richard Citation2012). Similar organizations and networks exist in Malawi and India, sharing the ideological platform of food sovereignty. We contend, however, that the imperial maize assemblage meets more profound resistance in the quiet everyday practices of millions of peasants around the world that are cultivating, saving, sharing and selecting maize outside commercial formal seed systems. There is a rich literature on the economic botany of maize, documenting the coevolution, resilience and endurance of this long-standing maize-peasant relationship (e.g. Brush and Perales Citation2007; Hartigan Citation2017; Bellon et al. Citation2018). As we conclude our account of the importance of maize’s more-than-human agency in shaping the current agri-food systems in Malawi and India, it is with the notion that maize dialectics remains an open-ended process.

Through our comparative investigation of Malawi and India, we have demonstrated key dynamics – both differing and overlapping – in terms of how the imperial maize assemblage forms and is driven forwards in the two countries. Comparing the maize assemblages in Malawi and India, the most significant difference relates to its human use: In Malawi, it is a staple crop and also the hybrid varieties must serve that purpose, while the maize surge in India is interlocked with the rise of meat production. Thus in Malawi, the massive state intervention in the maize market represented by the input subsidy program FISP is central for understanding how the imperial maize assemblage could make such inroads there, while in the Indian lowlands the meat industry, facilitated by the liberalized and corporate-dominated seed system, plays a similar role in the assemblage. In spite of these powerfull allies and in spite of hybrids’ higher yield potential, in Malawi and in parts of the highlands of India we see that local flint maize varieties continue to be preferred for their coevolved adaptations to local cuisine and farming practices.

The persistence of local maize cultivation among Malawi’s smallholder and in the highlands of India in spite of the powerfull influence of the imperial maize assemblage indicates that an earlier work by Scott may better equip us to understand the role of maize in these communities. Maize’s dual character as both vegetable and grain, able to grow in areas too steep and dry for rice, earned maize a place among the ‘escape crops’ enabling the type of livelihood activities described in The Art of Not Being Governed (Scott Citation2009, 205). Thus, even if maize is the most commercialized and formalized crop species in the Global South today, the majority of the maize is still sourced outside the formal seed supply system, often saved on farm or sourced through social networks or from informal markets. Sometimes the seeds are of local varieties, but they are also often ‘creolized’; bootlegged improved varieties, mixed with the local genepool (Bellon et al. Citation2018; Westengen et al. Citation2014). Maize’s ability to find powerful human allies testifies to its virtues, but faithfulness has never been one of them.

Acknowledgements

We thank colleagues Desmond McNeill at the Centre for Development and the Environment at the University of Oslo and Katharina Glaab and John Andrew McNeish at the Department of International Environment and Development Studies, Noragric, at the Norwegian University of Life Science for reading earlier versions of this paper and providing important inputs. We also thank the two anonymous reviewers for their helpful and inspiring comments and critique. Special thanks to Kristoffer Ring at the Centre for Development and Environment for assistance with the figure. OTW's work on this paper was supported by the Research Council of Norway funded ACCESS project (RCN-288493).

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Jostein Jakobsen

Jostein Jakobsen is a Researcher at the Centre for Development and the Environment (SUM), University of Oslo. His research interests are broadly within political ecology and critical agrarian studies, with fieldwork experience from southern India. Recent articles have been published in journals such as Globalizations, Journal of Agrarian Change, Canadian Journal of Development Studies and Geografiska Annaler: Series B, Human Geography.

Ola T. Westengen

Ola T. Westengen is an Associate Professor at the Norwegian University of Life Sciences. He works on the intersections of science and policy research on crop diversity and seed systems. Westengen was the first coordinator of the Svalbard Global Seed Vault. His research has appeared in PNAS, Theoretical and Applied Genetics, Nature Plants, Journal of World Intellectual Property and Agriculture and Human Values. He recently co-edited Farmers and Plant Breeding: Current Approaches and Perspectives (Routledge 2020).

Notes

1 In emphasizing this continuity, we agree with Loftus (Citation2020, 986) on the need for distinguishing between the more-than-human cyborgs of Haraway and the ‘decidedly apolitical conception’ found in much other posthuman work (see also Lave Citation2015).

2 Parts of the reason why Corn & Capitalism has remained a somewhat under-appreciated pioneering contribution is the fact that, while published in Spanish in 1988, it was first translated into English in 2003.

3 Drawing on McMichael, Fitting (Citation2011) has argued that Mexico’s food system can be seen as a ‘neoliberal corn regime’.

4 The intimate human-maize relationship is a recurring theme in Latin American cultures. In the Mayan mythology Popol Vuh, maize is ‘both the material from which humans are formed and the material that provides nourishment to that form’ (Huff Citation2006). The Guatemalan Nobel Prize winning author Miguel Ángel Asturias’ novel Men of maize (Citation1949) is a twentieth century variation over the same theme.

5 It is a notable feature of the imperial maize assemblage that it so far does not include GM-maize in neither of the two countries studied here. Consequently we do not discuss GM maize further in this contribution.See the GM Approval Database of the the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications (ISAAA) for the latest overview of approved GM crop varieties around the world. https://www.isaaa.org/gmapprovaldatabase/default.asp

6 Interview, Lilongwe, 7.2.2018

7 See Pionetti (Citation1997).

8 The configuration of top five leading companies appear to differ between Indian states, yet these three companies figure throughout as far as maize seeds are concerned (see Jakobsen Citation2020).

9 Interview, Bangalore, 9.2.2018.

10 Recently, Indian policymakers have also come to perceive hybrid rice as a potential pathway out of environmentally degraded agrarian environments, yet farmers have so far proven reluctant and hybrid rice is, rather, exemplary of how technocratic ‘solutions’ disregard socio-ecological realities (see Taylor Citation2020).

11 In some parts of the world, the fall armyworm attack has led to an emerging business of repair, registered in insecticide development and inventions such as automatized crop spraying drones.

References

- Access to Seeds Foundation. 2019. “Access to Seeds Index 2019 Synthesis Report: Bridging the Gap between the World’s Leading Seed Companies and the Smallholder Farmer.” Access to Seeds Foundation Amsterdam.

- Asturias, M. A. 1949. Men of Maize. Losada.

- Banik, D., and M. Chasukwa. 2019. “The Politics of Hunger in an SDG Era: Food Policy in Malawi.” Journal of Food Ethics 4: 189–206.

- Bellon, M. R., A. Mastretta-Yanes, A. Ponce-Mendoza, D. Ortiz-Santamaría, O. Oliveros-Galindo, H. Perales, F. Acevedo, and J. Sarukhán. 2018. “Evolutionary and Food Supply Implications of Ongoing Maize Domestication by Mexican Campesinos.” Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 285 (1885): 20181049.

- Berlan, J. P., & Lewontin, R. C. 1986. “The Political Economy of Hybrid Corn.” Monthly Review, 38: 35–48.

- Bezner Kerr, R. 2013. “Seed Struggles and Food Sovereignty in Northern Malawi.” Journal of Peasant Studies 40: 867–897.

- Bezner Kerr, R. 2014. “Lost and Found Crops: Agrobiodiversity, Indigenous Knowledge, and a Feminist Political Ecology of Sorghum and Finger Millet in Northern Malawi.” J Annals of the Association of American Geographers 104: 577–593.

- Blake, M. 2015. Maize for the Gods: Unearthing the 9,000-Year History of Corn. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Borras Jr., S. M., J. C. Franco, S. R. Isakson, L. Levidow, and P. Vervest. 2016. “The Rise of Flex Crops and Commodities: Implications for Research.” Journal of Peasant Studies 43 (1): 93–115.

- Braudel, F. 1977. Afterthoughts on Material Civilization and Capitalism. Baltimore: The John Hopkins University Press.

- Brush, S. B., and H. R. Perales. 2007. “A Maize Landscape: Ethnicity and Agro-Biodiversity in Chiapas Mexico.” Agriculture Ecosystems & Environment 121: 211–221.

- Challinor, A., J. Watson, D. Lobell, S. Howden, D. Smith, and N. Chhetri. 2014. “A Meta-Analysis of Crop Yield Under Climate Change and Adaptation.” Nature Climate Change 4: 287–291.

- Chinsinga, B. 2011. “Seeds and Subsidies: The Political Economy of Input Programmes in Malawi.” IDS Bulletin 42: 59–68.

- Chinsinga, B., and M. J. A. R. Chasukwa. 2018. “Narratives, Climate Change and Agricultural Policy Processes in Malawi.” Future Agriculture Working Papers 10: 140–156.

- Chinsinga, B., and C. Poulton. 2014. “Beyond Technocratic Debates: The Significance and Transience of Political Incentives in the Malawi Farm Input Subsidy Programme (FISP).” Development Policy Review 32: s123–s150.

- Chirwa, E., M. Matita, P. Mvula, and W. Mhango. 2016. Evaluation of the 2015/16 Farm Input Subsidy Programme in Malawi: 2015/16 Reforms and their Implications.

- CIMMYT. 2015. “Maize Workshop Sets Stage for Doubling Production in India by 2025.” https://www.cimmyt.org/news/maize-workshop-sets-stage-for-doubling-production-in-india-by-2025/.

- Crosby, A. W. 1972. The Columbian Exchange: Biological and Cultural Consequences of 1492. Westport, Conn: Greenwood Publishing Company.

- Cullather, N. 2010. The Hungry World: America's Cold War Battle against Poverty in Asia. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

- Denning, G., P. Kabambe, P. Sanchez, A. Malik, R. Flor, R. Harawa, P. Nkhoma, et al. 2009. “Input Subsidies to Improve Smallholder Maize Productivity in Malawi: Toward an African Green Revolution.” Plos Biology 7: 2–10.

- Devereux, S. 2002. “The Malawi Famine of 2002.” IDS Bulletin 33: 70–78. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1759-5436.2002.tb00046.x.

- Dorward, A., and E. Chirwa. 2011. “The Malawi Agricultural Input Subsidy Programme: 2005/06 to 2008/09.” International Journal of Agricultural Sustainability 9 (1): 232–247. doi:https://doi.org/10.3763/ijas.2010.0567

- Ellis, R. 1959. “The Food Properties of Flint and Dent Maize.” The East African Agricultural Journal 24: 251–253.

- FICCI/PWC. 2018. “Maize Vision 2022: A Knowledge Report.” New Delhi: FICCI.

- Fitting, E. 2011. The Struggle for Maize: Campesinos, Workers, and Transgenic Corn in the Mexican Countryside. Durham: Durham University Press.

- Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations. 2021. FAOSTAT Statistical Database.

- Fussell, B. 1999. “Translating Maize Into Corn: The Transformation of America's Native Grain.” Social Research 66: 41–65.

- Goergen, G., P. L. Kumar, S. B. Sankung, A. Togola, and M. Tamò. 2016. “First Report of Outbreaks of the Fall Armyworm Spodoptera Frugiperda (J E Smith) (Lepidoptera, Noctuidae), a New Alien Invasive Pest in West and Central Africa.” PLOS ONE 11 (10): e0165632. doi:https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0165632.

- Guthman, J. 2019. Wilted: Pathogens, Chemicals, and the Fragile Future of the Strawberry Industry. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Haraway, D. 2015. “Anthropocene, Capitalocene, Plantationocene, Chthulucene: Making Kin.” Environmental Humanities 6: 159–165.

- Harrigan, J. 2003. “U-turns and Full Circles: Two Decades of Agricultural Reform in Malawi 1981–2000.” World Development 31: 847–863.

- Hartigan, J. Jr. 2017. Care of the Species: Races of Corn and the Science of Plant Biodiversity. Minneapolis: Universiy of Minnesota Press.

- Haug, R., and B. K. Wold. 2017. “Social Protection or Humanitarian Assistance: Contested Input Subsidies and Climate Adaptation in Malawi.” IDS Bulletin 48: 79–92.

- Howard, P. H. 2019. “Corporate Concentration in Global Meat Processing: The Role of Feed and Finance Subsidies.” In Global Meat: Social and Environmental Consequences of the Expanding Meat Industry, 31–55 edited by B. Winders and E. Ransom. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

- Huff, L. A. 2006. “Sacred Sustenance: Maize, Storytelling, and a Maya Sense of Place.” Journal of Latin American Geography 5: 79–96.

- Indian Council of Food and Agriculture. 2015. Indian Seed Market.

- IPES-FOOD. 2017. Too Big to Feed: Exploring the Impacts of Mega-Mergers, Consolidation and Concentration of Power in the Agri-Food Sector.

- Jafri, Afsar. 2018. Politics of Seeds: Common Resource or a Private Property. New Delhi: Focus on the Global South.

- Jakobsen, J. 2019. “Neoliberalising the Food Regime ‘Amongst its Others’: The Right to Food and the State in India.” Journal of Peasant Studies 46 (6): 1219–1239.

- Jakobsen, J. 2020a. “The Maize Frontier in Rural South India: Exploring the Everyday Dynamics of the Contemporary Food Regime.” Journal of Agrarian Change 20 (1): 137–162.

- Jakobsen, J., and A. Hansen. 2020b. “Geographies of Meatification: an Emerging Asian Meat Complex.” Globalizations 17 (1): 93–109.

- Kaul, Jyoti, Ramesh Kumar, Usha Nara, Khushbu Jain, Dhirender Olakh, Tanu Tiwari, Om Prakash Yadav, and Sain Dass. 2018. “An Overview of Registration of Maize Genetic Resources in India.” International Journal of Current Microbiology and Applied Science 7 (2): 933–950.

- Kloppenburg, J. R. 1988. First the Seed. The Political Economy of Plant Biotechnology 1492-2000. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Kumar, R., K. Srinivas, and N. Sivaramane. 2013. “Assessment of the Maize Situation, Outlook and Investment Opportunities in India.” Country Report – Regional Assessment Asia (MAIZE-CRP), National Academy of Agricultural Research Management, Hyderabad, India.

- Kydd, J. 1989. “Maize Research in Malawi: Lessons from Failure.” Journal of International Development 1: 112–144.

- Kydd, J., and R. Christiansen. 1982. “Structural Change in Malawi Since Independence: Consequences of a Development Strategy Based on Large-Scale Agriculture.” World Development 10: 355–375.

- Lave, R. 2015. “Reassembling the Structural: Political Ecology and Actor-Network Theory.” In The Routledge Handbook of Political Ecology, edited by T. Perreault, G. Bridge, and J. McCarthy, 213–223. London: Routledge.

- Lele, U., and A. A. Goldsmith. 1989. “The Development of National Agricultural Research Capacity: India's Experience with the Rockefeller Foundation and Its Significance for Africa.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 37: 305–343.

- Loftus, A. 2020. “Political Ecology III: Who are ‘the People’?” Progress in Human Geography 44 (5): 981–990.

- Lunduka, R., M. Fisher, and S. Snapp. 2012. “Could Farmer Interest in a Diversity of Seed Attributes Explain Adoption Plateaus for Modern Maize Varieties in Malawi?.” Food Policy 37: 504–510.

- McCann, J. 2005. Maize and Grace: Africa's Encounter with a New World Crop, 1500-2000. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- McMichael, P. 2013. Food Regimes and Agrarian Questions. Winnipeg: Rugby, Fernwood Publishing and Practical Action Publishing.

- Messina, J. P., B. G. Peter, and S. S. Snapp. 2017. “Re-evaluating the Malawian Farm Input Subsidy Programme [Published Correction Appears in Nat Plants. 2017 Mar 13;3:17044].” Nature Plants 3: 17013. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nplants.2017.13. Published 2017 Mar 6.

- Ministry of Environment and Forests, Government of India. 2011. Biology of Zea mays (Maize). New Delhi: Government of India.

- Mir, C., T. Zerjal, V. Combes, F. Dumas, D. Madur, C. Bedoya, S. Dreisigacker, J. Franco, P. Grudloyma, and P. Hao. 2013. “Out of America: Tracing the Genetic Footprints of the Global Diffusion of Maize.” Theoretical and Applied Genetics 126: 2671–2682.

- Moore, J. W. 2015. Capitalism in the Web of Life: Ecology and the Accumulation of Capital. London: Verso.

- Morris, M. L., R. P. Singh, and S. Pal. 1998. “India's Maize Seed Industry in Transition: Changing Roles for the Public and Private Sectors.” Food Policy 23 (1): 55–71.

- Mzamu, J. J. 2012. “The Ways of Maize: Food, Poverty, Policy and the Politics of Meaning Among the Chewa of Malawi.” PhD Thesis. University of Bergen.

- Pandey, B. 1994. “Hybrid Seed Controversy in India.” Biotechnology and Development Monitor 19: 9–11.