ABSTRACT

This article examines the corn-driven boom of Ukraine’s agriculture, the damage wrought by Russia’s war, and the adaptation strategies by Ukrainian corporate agribusinesses. It thereby contributes to debates on the resilience of the global food system: we confirm extant concerns that the neoliberal agricultural model is highly sensitive to external shocks. We show that export-oriented agribusinesses initially sustained significant losses, but learned to adapt to the dramatically changing economies of corn-growing. Finally, despite this remarkable resilience, we argue that military force, wielded by a state explicitly challenging Western hegemony, can significantly disrupt corporate power in the contemporary food regime.

1. Introduction

Russia’s war in Ukraine has severely disrupted global agricultural trade, causing food crises across many countries. Many scholars have argued that the war demonstrated the fragility and unsustainability of the globalized neoliberal agricultural model, which was unable to respond and adapt quickly to war-related disruptions in the agrifood value chain (Clapp Citation2022; Mamonova Citation2022). Other voices stress resilience in the global food system and point to adaptation in response to global shocks, such as Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine (Reardon and Swinnen Citation2020; Wood et al. Citation2023). Our study contributes to this debate and examines the war-related damages and adaptations of Ukrainian export-oriented agriculture during the first year following Russia’s invasion of the country on 24 February 2022. We focus on one agricultural commodity – corn (or zea mays), which in Ukraine bears a proud name of the ‘queen of the fields’ (tsarytsya poliv).

Ukraine is one of the four largest exporters of corn in the world, accounting for 16% of global corn exports. Over the last two decades, prompted by the ever-increasing global demand for this flex-crop and attracted to Ukraine’s cheap and fertile land, large agribusinesses – both Ukrainian and multinational – have invested heavily in Ukrainian corn production and related sectors. This led to a remarkable corn boom in Ukraine. Between 2001 and 2021, corn production increased nearly tenfold and about 90% of this corn (depending on the year) is exported. The ‘queen of the fields’ has become the ‘cash cow’ of Ukrainian agribusiness, since it required relatively low investment and generated stable and sizable profits (Lotysh Citation2021).

Corn’s viability as Ukraine’s dominant and most profitable crop was fundamentally challenged by the war. Our study shows that the conditions for corn’s peacetime success started working against it, and that corn became a major burden for Ukrainian agribusinesses during the first six months of the war. The destruction of agriculture-related infrastructure, limited domestic demand for corn, and the Black Sea blockade have led to a domestic glut of corn. Corn producers had to contend with plummeting farm-gate prices along with soaring production costs, as fuel, fertilizer, transport, and storage became more expensive due to the war. They had to find ways to store and process the 2021 corn harvests, a costly challenge during the war. Suffering severe losses, farmers reduced corn cultivation in favor of other crops. The Black Sea Grain Initiative – signed by the UN, Ukraine, Russia and Türkiye almost six months later – has restored most grain exports from Ukrainian ports. Since then, corn holds the promise of earning much needed export revenue to help rebuild Ukraine in years to come.

These findings make three key contributions to the debates on resilience of the global food system. First, most broadly, our research confirms that globalized neoliberal agriculture – with its overreliance on the export of one monocrop as an agricultural raw material – is highly sensitive to external shocks. Second, evidence from Ukraine suggests that even though corporate agribusinesses sustained significant losses during the first months of the war, they have been able to adapt and transform in the face of existential threats.Footnote1 This finding counters the argument that highly-globalized industrial agriculture ceases to function effectively due to recurring crises and instabilities (Weis Citation2010). Third, our study speaks to the changing nature of the contemporary food regime (Friedmann Citation2004; McMichael Citation2009a; Citation2009b; Citation2012). While most scholars assume that virtually all power rests with multinational corporate actors in the corporate food regime, the war-related disruptions to Ukrainian agriculture show how military force – in this case, wielded by an authoritarian anti-liberal state – is effectively challenging and disrupting the neoliberal agrifood system, even if corporate actors are relatively resilient. It may therefore be necessary to refocus attention on the ways geopolitical conflict and military might – liberal and anti-liberal – underpin and transform the global food system.

Our analysis is based on semi-structured in-depth interviews conducted in Ukraine in the fall of 2022 with Ukrainian agricultural experts, agronomists, and representatives of large agribusiness. We also use primary data from our previous fieldwork in Ukraine and available online interviews with farmers and representatives of agribusiness. We also utilize original data obtained from the State Statistics Committee of Ukraine, the Ukrainian platform for grain trade – Zernotorg, FAO and other national and international sources.

The remainder of the paper is structured as follows: Section 2 introduces the key features of the contemporary globalized agrifood system and a set of urgent questions regarding its resilience to external shocks and disturbances. Section 3 places the current situation in Ukraine in historical perspective, providing background on the role of corn in making Ukraine the breadbasket of Europe and the world. Section 4 gives an account of Ukrainian agriculture under siege, detailing the impact of the war on corn production, storage, transport, and export infrastructure. Section 5 provides insights into how Ukrainian farmers are responding to the war and what the current challenges may mean for the future of corn in the country. The final section draws theoretical conclusions for broader questions related to the fragility of the contemporary food system.

2. Globalized agrifood system and its ability to withstand external shocks

The continued industrialization, financialization, and globalization of agriculture are defining features of twenty-first century transnational food systems (Clapp Citation2014; McMichael Citation2012). They have gone hand in hand with the steady transition from traditional farming to production for agro-exports and the increasingly dominant role of multinational corporations that exert monopolistic power over entire agrifood chains and undermine other agricultural models, especially small-scale subsistence farming (Van der Ploeg Citation2010; Citation2012). Many elements of the globalized industrial agricultural order, rooted in the twentieth century’s ‘corporate food regime’ (Friedman and McMichael Citation1989), have become more pronounced in the twenty-first century, with mounting competitive pressures and expanding international agrifood trade. Corn plays an exceedingly important role in the contemporary corporate food regime (McMichael Citation2009b).

In much of the development policy world, the export-oriented model of agriculture is seen as the most efficient and promising way to guarantee rural prosperity and food security for a growing world population (Deininger and Byerlee Citation2011). Large transnational corporations have indeed brought new technologies and financial resources to many rural areas across the world, which has increased productivity of industrial farm enterprises. In general, this has brought down the price of agricultural commodities, making food more accessible to the growing ranks of urban poor (World Bank Citation2008). However, there were several food price crises over the past few decades, and food prices have been increasingly volatile and have risen even before the COVID-19 pandemic and the war in Ukraine.

A large and diverse set of voices has been reassessing this global food order, drawing attention to the growing environmental, social and economic costs of the hyper-globalized, corporate food regime, and also highlighting the merits of alternative models of food production (see e.g. Edelman et al. Citation2014; Rosset Citation2011 on food sovereignty as an alternative development paradigm).

One of the most salient and widely shared concerns is that contemporary globalized agriculture is highly sensitive to exogenous shocks and disturbances (Clapp and Moseley Citation2020 Reardon and Swinnen Citation2020; Van der Ploeg Citation2010;). Jennifer Clapp (Citation2022) attributes the vulnerability of the global industrial food system to extreme concentrations at the field, country, and global market levels:

At field level, there is a concentration of crops, seed varieties, and industrial inputs. At the country level, there is a concentration of countries producing staple grains for export. And at the global level, there is a concentration of firms and financial actors that dominate global grain and inputs markets. (Clapp Citation2022, 2)

The evidence from Ukraine allows us to address a central question in these debates, namely the resilience of neoliberal industrial agriculture. Resilience is understood here as the capacity of the agrifood system to deliver desired outcomes when exposed to financial pressure and shocks. It consists of robustness (the ability of the system to resist disruptions), recovery (the ability to return to prior outcomes following disruption), and re-orientation (the ability to deliver acceptable alternative outcomes) (Tendall et al. Citation2015).

Covid-related disruptions of complex value chains and migrant labor flows demonstrated that they could paralyze some actors and hike inflationary pressures. Clapp and Moseley (Citation2020) have argued that COVID-19 exposed the ‘fragility of the neoliberal food security order,’ and Saad-Filho (Citation2020) saw this as the potential ‘end of neoliberalism.’

Reardon and Swinnen (Citation2020), and others, though, argue that the global food system is quite resilient and able to withstand global shocks due to ‘a range of innovations that capitalize on knowledge, data, and mechanization have been deployed to keep supply chains running.’ Frederick Buttel, in ‘Sustaining the unsustainable’ (Citation2006), similarly holds that modern industrial agriculture – even if it is socio-economically unsustainable, unfair and environmentally unstable – has significant staying power through agricultural subsidies, market dominance, access to technology, external finance, and by influencing global trade rules.

A related long-standing question concerns the ability of small peasant farms to compete with large, corporate agribusiness. The recent global disruptions, interestingly, revisits the classic ‘agrarian question’ (see Akram-Lodhi et al. Citation2021), but this time it concentrates on the viability of large actors: will globalized corporate agriculture persist in the face of major systemic crises, or will the system’s protagonists (i.e. large corporate agricultural producers) need to diversify and adjust its practices in order to survive? Therefore, the struggles and adaptations of Ukrainian agribusinesses during the war may provide valuable insights for broader conclusions about the resilience of the globalized neoliberal agricultural order and, therefore, global food security.

3. Ukrainian farms feed the world; Russia imperial vs. global corporate episodes of globalization

Ukrainian grain has long fed hungry urban workers in cities across Europe (Nelson Citation2022). Indeed, much of the Russian Empire’s grain originated on the soil of what is modern-day Ukraine. In 1768, Tsaritsa Catherine II sent imperial troops to seize Ukrainian territory as part of her plan to expand the borders of the Russian Empire. Ukraine’s fertile soil and established transport routes, the ‘black trails’ (chorni shlyakhi) which crossed Ukraine’s plains and connected fields to Black Sea ports, presented opportunities to bring large quantities of grain from the southern reaches of the Russian Empire to Europe via the Mediterranean Sea (Nelson Citation2022).

After the October Revolution in 1905, the Bolshevik government used foreign grain sales to finance the rapid industrialization of the Soviet Union, to feed industrial workers and the Red Army. Yet, after Lenin’s nationalization of land in 1917, the government faced an uphill battle to obtain grain from peasants, who preferred to produce for subsistence or for the black market, rather than sell to the state-procurement agents at low prices. Stalin’s collectivization campaign, initiated in late 1929, aimed to solve the ‘grain problem’ by integrating peasant landholdings and labor into collective and state farms (kolkhozy and sovkhozy). As agents of the state forced peasants to join collectives, they caused widespread misery, famine and death, known as the Holomodor – a top-down campaign marked by the deaths of millions of peasants (Applebaum Citation2018; Heinzen Citation2004; Wengle Citation2022).

Nikita Khrushchev’s agricultural reforms were in many ways a continuation of the Bolshevik project to exert political and economic control over peasants and rural production. One of the main thrusts of agricultural reform was Khrushchev’s promotion of corn, which he called the ‘queen of the fields’ for its high yields, caloric value, and ability to boost livestock production (Hale-Dorrell Citation2018). With rich soils, ample rainfall and long growing seasons, the Ukrainian Soviet Republic was the most appropriate area for corn cultivation. After some initial success – production of corn in the Soviet Union increased from 4.4 million hectares in 1952 to 5.9 million by 1965 (Morgunov Citation1992) – corn production faltered. By 1975, the area under cultivation with corn contracted to 2.6 million hectares, and it shrunk further to only 1.2 million in 1990 (Karpenko Citation2019; Morgunov Citation1992). Prior to Ukraine’s independence in 1991, Russia’s imperial, and later Soviet authorities, had always been deeply involved in implementing ambitious plans for what to sow and reap on Ukrainian soil, occasionally with the backing of the armed forces and against the will of a reluctant local population.

The collapse of the Soviet state and the planned economy in 1991 spelled the collapse of the Soviet corn dream, and more broadly, halted Ukrainian farms’ ability to produce grain beyond domestic demand for a decade. Ukraine’s first post-independence land reforms aimed to distribute the land of kolkhozy and sovkhozy to the rural population, thereby creating incentives for private farming. These reforms initially failed because other key factors of production (i.e. capital, machinery, knowledge) and connections to input suppliers and markets vanished with the collective farm structure, while institutions that underpin capitalist markets – such as the rule of law, cadaster systems and crop insurance – were absent (Csaki and Lerman Citation1997; Mamonova Citation2015). The former collective farm structure remained largely in place and Ukrainian farms struggled to adjust to new market conditions during the post-Soviet decade. Production yields plummeted, and much fertile land was left fallow (Lerman et al. Citation2003). Corn production declined along with the entire grain sector; corn yields were exceptionally low as agricultural inputs such as high-yielding seeds, synthetic fertilizers and herbicides were no longer available (Lerman et al. Citation2003).

3.1. Agricultural recovery in the age of global corporate food system

Starting in 1999 and the early 2000s, Ukrainian agriculture began to show signs of recovery and, for the first time in recent Ukrainian history without the overt involvement of an imperial state, started to thrive. In the first few decades of the twenty-first century, global food prices were high, spurring demand for rural assets in the Eurasian grain belt by a wide range of global financial investors (Visser and Spoor Citation2011). Ukrainian farms integrated into financial and agricultural commodity markets. While foreign and financial investors have been unable to buy farmland due to the 2001 moratorium on land sales, they were able to lease land from the rural residents through long-term contracts (Von Cramon-Taubadel, Demyanenko, and Kuhn Citation2004). For most of this period, the Ukrainian government was largely a passive observer of the ensuing influx of foreign capital, though relative stabilization of macro-economic conditions contributed to making Ukraine an attractive target for global financial investors, and changing governments all viewed the capital influx as a beneficial trend. The most important change in the political and legal framework for Ukrainian agriculture was enacted only very recently: in March 2020, the Verkhovna Rada amended the Land Code, setting the stage for a gradual transition to private ownership of land between 2021 and 2024, phasing out the moratorium on land sale that had been in place since Ukrainian independence (Verkhovna Rada Citation2020).Footnote2

Very large and vertically integrated corporate agribusinesses, known as ‘agroholdings,’ had already gained control of increasing shares of Ukrainian farmland for nearly two decades prior to this legislative change, largely through long-term leases (Mamonova Citation2015). Funding mainly originated from domestic oligarchic groups, financial connections to Russian agroholdings, and foreign capital (Kuns and Visser Citation2016). Over the course of a decade, agroholdings that specialized in export-oriented monocrops – predominantly wheat, corn, and oilseeds – came to dominate the agricultural value chain in Ukraine from seed supply, to machinery, to the export terminal. Transnational agrifood and agrichemical corporations – such as Monsanto/Bayer, Cargill, and DuPont – invested heavily in operations in Ukraine, bringing new technologies, management techniques and linkages to global markets.

Today Ukrainian agriculture has a bimodal structure. Large agricultural enterprises, mainly specializing in the production of grain for export, cultivate 53.9% of arable land and provide 54.5% of Ukraine's gross domestic agricultural product. The remaining share, 46.1% of agricultural product, comes from a diverse set of small and medium-sized family farms and rural households that cultivate 45.5% of the land, producing potatoes, vegetables, fruits, dairy and meat products, and occasionally grain, for the domestic market. While both types of producers are important to the Ukrainian economy and food security, the Ukrainian government largely prioritizes big business in its vision of economic development and post-war recovery, often ignoring the contributions and interests of smallholders (Mamonova Citation2022).

3.2. Ukraine’s neoliberal ‘corn miracle’ and export-led growth

The scramble for land and other rural assets in Ukraine was the result of a confluence of factors. As noted above, financial investors had become interested in agriculture due to the fertile, but under-valued farmland and high commodity prices. The global demand for corn was one of the main drivers of rapidly rising investments in the Ukrainian rural sector and its integration into global agricultural markets (Sarna Citation2014). Ukraine’s 2008 accession to the World Trade Organization (WTO), reduced trade-associated risks, further encouraged investment, and contributed to establishing Ukraine as a key agricultural exporter (Bessonova, Merschenko, and Gridchina Citation2015). The Ukrainian corn boom is reflected in virtually all agricultural indicators of this period, summarized in . Production rose from 4747 thousand metric tons in 1991 to a record 42,126 thousand metric tons in 2021.

Table 1. Main indicators of Ukraine’s corn boom, 1991–2021.

The climatic conditions of Ukraine’s grain belt have long been widely recognized as suitable for corn. Under the present climate conditions, the north, central, and central-west parts of Ukraine are all suitable for growing corn, and with climate change and new hybrid varieties, the country’s Corn Belt is shifting north (Karpenko Citation2019). In the Chernihiv region alone, for example, the area cultivated with corn increased by about 18 times during 2010–2019.

With these climate conditions and the influx of capital, the area under corn cultivation in Ukraine increased from 1.2 million ha in 1990 to 2.7 million ha in 2009, and it reached 5.4 million ha in 2021 (). The corn expansion increasingly replaced other crops. Barley was the biggest loser: its acreage shrank by about 40% (more than 100,000 hectares) over the last decade, although yield growth has kept barley production largely stable (Braun Citation2022). The other crops, replaced by corn, were: rye (decreased by 59% during the last 10 seasons), Sugar beet (by 49%) and oat crops (by 44%) (Superagronom Citation2020). Corn yields, meanwhile, more than doubled between 1991 and 2021. In 1991 agricultural producers harvested about 3.9 metric ton per hectare, while in 2021 the yields were 7.8 metric ton per hectare (). Yield gains resulted from the reliance on high-tech hybrid seeds, the use of other cutting-edge agricultural technologies and agrichemicals, and investments in ailing irrigation systems (Dankevych et al. Citation2021; Matvienko and Sonko Citation2016; Skydan et al. Citation2022). An estimated 5% to 30% of corn grown in Ukraine are genetically modified (Latifundist Citation2021; Ukragroconsult Citation2013), because it can improve drought tolerance and yield potential. Although the production and distribution of GM seeds are prohibited in Ukraine, the state does little to enforce the GMO ban (Grigorenko Citation2023).

As much as 75–85% of Ukraine’s annual harvest is exported (Latifundist Citation2021, ). Domestic demand did not grow as much as production, as the population of Ukraine was declining and the livestock operations (aside from poultry), did not grow as fast as the field crops (Braun Citation2022). Of the amount that remains for domestic consumption, 90% is used in feed production, mainly for poultry and livestock (Elevatorist Citation2021).

Not only did the volume of corn exports increase dramatically, but the destination of Ukrainian corn exports also changed. By 2021, Ukraine was one of the four largest world exporters of corn on a par with the USA, Brazil and Argentina, accounting for 16% of global corn exports. The year before the war, the main destinations of corn exports from Ukraine were: China (7 926 million tons; 32% of corn export), Spain (2 466 million tons; 10%), the Netherlands (2 284 million tons; 9.3%), Egypt (2.144 million tons; 8.7%), Iran (2 023 million tons; 8.2%) and Türkiye (1 024 million tons; 4.1%).

Such robust trade was facilitated by various trade agreements. The so-called Deep and Comprehensive Free Trade Agreement (DCFTA) between Ukraine and the EU signed in 2014 significantly reduced tariff for corn export from Ukraine to the EU, 0% for the first 400,000 tonnes and more (Hellyer and Pyatnitsky Citation2013). In 2012, Ukraine signed a trade deal with China to export corn to the country for the first time with increasing scale as China diversified from its reliance on the USA’s corn (Reuters Citation2012). Globally 60% of corn is used for livestock feed, 12% for food, and the rest is used for biofuel production and other purposes (Latifundist Citation2021).

An important aspect of Ukraine’s corn export is that corn is predominantly exported by ship: before the war, 98% of total grain exports was exported through the Black Sea ports. In 2021, most of the corn was shipped from four ports: Chornomorsk (9.2 million tons), Mykolaiv (7 million tons), Yuzhnoye (5.7 million tons) and Odesa (3.1 million tons) (Stark Shipping Citation2022).

3.3. Winners of the corn bonanza

The major actors in Ukraine’s corn boom are large corporate agroholdings along with the transnational companies involved in supplying inputs, financing rural production and commodity trading. Large corporate farms have gained significantly from narrow specialization in corn production. The cost of leasing Ukrainian land is low and by introducing labor-saving technologies, they are able to operate profitably (Graubner and Ostapchuk Citation2018). Input suppliers have significant market power because these industries are concentrated. In corn seed breeding, for example, the 10 largest agricultural enterprises cultivate 71% of the total sown area used for seed cultivation in 2020 (30,237.5 ha). The top three – Stasi Nasinnia (a Ukrainian-American joint venture), Monsanto/Bayer (Germany) and Syngenta (Switzerland) control the largest share of the seed market. One of Monsanto’s largest and newest facilities was constructed in Zhytomyr in 2018 (Bayer Citation2018). These breeding companies sell to Ukrainian corn producers, but also operate their own large-scale corn production, oriented towards exports (Superagronom Citation2020).

Transnational grain trading companies, such as Toepfer, Cargill, Serna (Glencore) have also been heavily involved and have profited from the globalization of Ukrainian corn, while Ukrainian trading companies act as intermediaries between local farms and these global actors (Zhyhadlo and Sikachyna Citation2008). The presence of these companies incentivized Ukrainian agroholdings to invest in agricultural production and transportation. Nibulon, Kernel, Serna (Glencore) and Myronivsky Hliboprodukt have all invested in and built new facilities, such as grain elevators, grain receiving points, and transshipment terminals to increase port capacity for storage and transshipment of grain (Lapa et al. Citation2007).

The rise of agroholdings and grain trading companies has been facilitated by the policies of the Ukrainian government that has supported the development of grain exports in general, and corn in particular. Mykhailo Kliuchevych, a Ukrainian agricultural economist, declared that ‘cultivating and processing of corn is the Ukrainian pathway’.Footnote3 Though the Ukrainian government’s budgetary support for rural producers is quite modest in comparison with the EU and Russia (as indicated by the OECD’s PSE data), trade agreements and other efforts to connect producers and grain traders have been helpful. The Cabinet of Ministers of Ukraine established the ‘State Agrarian Exchange’ in 2005, which was to provide assistance to agricultural enterprises in concluding forward contracts, organize grain auctions, establish cooperation with international financial organizations, and control the market price for traded agricultural commodities (AgroFund Citation2022). In 2013, the functions of the exchange were transferred to the state-owned PJSC ‘Agrarian Fund.’ The government also reduced taxes on agricultural producers. Finally, a 2021 law reduced the valued-added tax (VAT) on key export commodities, primarily grains and oilseeds, from 20% to 14% – a tax stipulation that has been seen to mostly benefit the large export-oriented agroholdings (Zanuda Citation2021).

The rise of agroholdings and the corn boom in Ukraine took place in the context of the hyper-globalization and financialization of the contemporary global food regime. Land concentration in Ukraine is conceptualized by some scholars as part of global land grabbing (Plank Citation2013; Visser and Spoor Citation2011). While these trends have raised concerns in other areas of the world, they have not, on the whole, been perceived as negative trends in Ukraine. A number of factors have contributed to this: first, land concentration involved land that belonged to Soviet era collective farms and so did not entail direct dispossession of Ukrainian landowners (Mamonova Citation2015). Secondly, many agroholdings are pursuing corporate social responsibility programs, which has helped to sway rural residents’ opinions in their favorFootnote4 (Gagalyuk, Valentinov, and Schaft Citation2018). Third, many of these rural residents, along with national policy makers and the Ukrainian public at large, continue to view large-scale operations as inherently more beneficial, adhering to a ‘big is beautiful’ logic that underpinned Soviet-era agricultural production. Finally, many actors see the growth in agricultural exports – accounting for 45% of all Ukrainian exports in 2021 – as a sufficient justification for the concentration of land under the control of agroholdings (Kvitka Citation2021).

3.4. Concerns about monocrop industrial production of corn in Ukraine

While the globalization of agriculture is thus largely welcome, there are also voices that have raised concerns. Ukrainian scholars are critical of how land concentration exacerbates socio-economic stratification and unemployment in rural communities (Karpyshin Citation2019) and leads to a reduction in landscape and biodiversity (Maruniak et al. Citation2021). Environmental concerns are the most salient and widely shared. Mykhailo Kliuchevych notes that corn monocrops and the absence of spatial diversification of crops may lead to ‘soil fatigue, causes the accumulation of pathogens and specific pests.’ He also points out, though that corn is less harmful than sunflower seeds, because ‘sunflower cultivation technology puts [even] higher burden on the soil and creates a number of risks for the future.’Footnote5

One of the most salient concerns related to the increase in commodity corn production is the high and mounting dependence on inorganic fertilizer. Soviet-era agricultural production relied on an extensive system of irrigation canals, and used fewer agrichemicals compared to agriculture in the capitalist West. This infrastructure, however, has suffered from under-investment and deferred maintenance since the collapse of the Soviet Union. There are, however, few collective incentives to maintain irrigation canals, as there are no private and direct returns on investments of shared infrastructure (Leshchenko Citation2021). Instead, ‘many agricultural companies are increasingly using fertilizer to improve corn yields instead of implementing irrigation schemes,’ according to Mykola Kosolap, professor at National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine.Footnote6

Indeed, we see this turn towards fertilizer in Ukrainian government statistics: in 2001 the use of inorganic fertilizers was at the level of 14 kg/ha of a corn field, then in 2021 it amounted to 171 kg/ha ().

While agroholdings justify fertilizer use as a necessary input, some Ukrainian stakeholders, including scientists and small-scale farmers, see it as excessive and unsustainable in the long run (Galperina Citation2014). An owner of a family farm expressed this concern as early as 2012:

I do not grow corn because it depletes the soil. After [growing] it, the soil is not fertile. I specialize in buckwheat. When you grow corn, you apply a lot of nitrogen fertilizers, i.e. herbicides, pesticides, then the next year you cannot sow buckwheat there. The bee will not come to such a field. The bee knows that this field is poisoned. The soil is dead. […] Large companies deluge the soil with a lot of chemicals. They do not care about the soil. They use so many chemicals that they pollute the groundwater.Footnote7

Overall, though, despite these concerns about environmental risks, corn was generally seen as a key agricultural commodity that helped Ukraine become the world’s leading grain exporter and provided resources for domestic agricultural development.

4. Agriculture under siege

Since the onset of the war, the harm inflicted by the Russian occupying forces on Ukrainian farms and facilities related to agricultural production and export has been extensive and targeted (Wengle and Dankevych Citation2022a). There are at least four types of critical damage to Ukrainian agriculture. The first type is theft. Russian troops are reported to have stolen various types of grain and agricultural machinery from occupied territories. The second type of damage involves the disruption of the current growing season due to the lack of access to agricultural inputs and diverted farm labor. Since the ripening of crops this fall, intentional burning of crops is also part of this category. A third type of harm is the destruction of agricultural infrastructure. This includes damage to farmland, due to bombings and mines, and the destruction of machinery, irrigation systems, grain storage elevators and silos, transport infrastructure, and other assets. This category, damage to infrastructure, is likely to be the most significant in terms of their long-term costs. A fourth type of damage is related to Russia’s blockade of the Black Sea and the Sea of Azov, the export routes for the bulk of Ukrainian food commodity crops. Russia has used the blockade of Ukraine’s sea trade routes as an effective tool not only to limit and control Ukraine’s ability to export agricultural commodities to global markets, but also to extract concessions to the sanctions regimes in negotiations with the West (Wengle and Dankevych Citation2022b).

4.1. Trade and storage disruptions due to the war

The effects of the war on Ukrainian export-oriented agriculture in fact should be divided into two separate periods: first, the period from late February through late July, when the Russian naval blockade entirely cut off all inbound and outbound cargo from Ukrainian ports created mounting and dire challenges; and second, the period from July 22 through the end of the year when a partial easing of the blockade led to a gradual resumption of grain exports.

The blockade of Ukraine’s Black Sea ports created enormous logistical challenges for agribusinesses during the first half of 2022, as already contracted grain languished in silos, putting pressure on storage facilities. Before the war, the total capacity of elevators and silos in Ukraine was about 57 million tons (Mucha and Vorobyova Citation2022). Storage needs for grain and oilseeds in the early months of 2022 doubled, amounting to 107.38 million tons (Khvorostyanyi Citation2022). Russian troops also deliberately targeted and destroyed grain elevators throughout Ukraine, including grain storage facilities in the Sumy region, parts of Kharkiv, Chernihiv, Zaporozhye, Donetsk and Luhansk. An estimated 22 million tons of storage capacity was destroyed or is inaccessible due to their location in the combat zones (Mucha and Vorobyova Citation2022).

Corn is particularly affected by the challenges related to grain storage. A voluminous and heavy grain, it is costly to transport and store. Before long-term storage, corn needs to be pre-dried to a standard 14–15% moisture content (Fedorchuk Citation2014). The Ukrainian government, together with private sector stakeholders and several international donors tried to find ways to address the storage-related problems. With the help of the FAO and Japanese foreign aid, polyethylene storage sleeves and mobile warehouses were placed in fields to temporarily protect grain (Forbes Citation2022). Some of the wheat, sunflower and other oil seeds originally destined for export could be sold on the domestic market, but there was very little domestic demand for corn, which in turn led to plummeting prices for the commodity (Khvorostyanyi Citation2022). Although reliable estimates of the extent of damage are not available, blocked export routes and storage difficulties resulted in damaged or spoiled corn.

Against the background of mounting grain surplus and in anticipation of the fall harvest, Ukraine and Russia reached an agreement that allowed the partial easing of the naval blockade. The Black Sea Grain Initiative (BSGI) – signed by Ukraine, Russia, and Türkiye on 22 July 2022, and supported by the UN – established the parameters of a so-called grain corridor, a partial easing of the naval blockade that created a way for Ukrainian food crops to reach world markets. The first grain shipment that left the port of Odessa in July 2022, a Sierra Leone-flagged grain cargo vessel named Razoni carried 26,000 tons of corn. In the summer and fall, Ukrainian corn exports resumed, which in turn brought down global prices for corn. In September 2022, corn was the most exported agricultural product from Ukraine: a record 2 million 149 thousand tons were sold, which is the highest volume since the beginning of the year (Sereda Citation2022). China, Spain and Turkey are the main export destinations for grain exports under the BSGI, with 7.6, 5.9 and 3.2 million metric tons respectively, as of June 2023. Corn (51%) and wheat (27%) make up the main cargo (UN Citation2023).

While the BSGI is not perfect, as it is politically tenuous and allows for only limited tons of grain to be exported, it is also a better-than-nothing solution as it is currently almost impossible for Ukraine to export a significant amount of grain via rail and road (Wengle and Dankevych Citation2022b). Rail and road exports of corn via Western Ukraine were limited to about 200 thousand tons per week, and these land routes were not feasible for shipments to Ukraine’s major buyers in China and Egypt (Agronews Citation2022). The first BSGI agreement expired on November 19; it was renewed for 120 days in November 2022, and again for 60 days each in March and May of 2023.

4.2. Dramatically changing corn economies

The war, blockade and the negotiated agreement that opened the grain corridor have had far-reaching effects on corn prices, both on the Ukrainian domestic market and on global markets. Global food commodity prices in general, including corn, were at a historic high even before Russia’s invasion, due to COVID and climate related disruptions. Global market prices remained high until July 2022, when the BSGI eased pressures on supply, which precipitated a drop in global commodity prices.

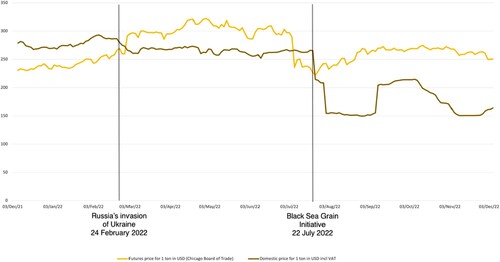

demonstrates the discrepancy between global prices and domestic prices of corn. It compares the price of corn on the Chicago Board of Trade (CboT), and the price of Ukrainian corn as reported by Zernotorg – an agricultural marketplace which connects farmers and traders in Ukraine.

Figure 1. Global and Ukrainian domestic prices for corn, 2022 ($USD/ton).

Sources: Global prices are based on data from the Chicago Board of Trade (www.markets.businessinsider.com); Ukrainian domestic prices are based on data from Zernotorg (www.zernotorg.ua).

Before the war, Ukrainian corn producers were able to obtain prices above the global market prices, as measured by the CBoT futures prices. This reflected global traders’ expectations of the price effects of a smaller than average Ukrainian harvest for 2021 that followed from a severe drought in the summer of 2021. The blockade of the Black Sea ports flipped the price curves: world prices for corn began to grow exponentially due to war’s effects on the global grain trade, while the blockade led to an oversupply of corn in Ukraine and brought down domestic corn prices. There was practically no domestic demand for corn during this period. Ukrainian grain traders did not buy corn because of the high and mounting risks associated with its storage and export. Domestic consumers of corn – mainly livestock companies – have stockpiled corn for feed since the previous year (APK-Inform Citation2022). Moreover, many livestock and poultry producers were unable to function normally and donated their animals and birds to local residents and the Ukrainian army or slaughtered them, which also contributed to lower domestic demand for corn (APK-Inform Citation2022). Consequently, Ukrainian corn producers were forced to sell their products well below world market prices or look for alternative ways to use unsold corn.

The BSGI has flipped the price curves once more, but just for less than one month.Footnote8 Since the beginning of August 2022, the CBoT futures prices for corn have been significantly higher than the Ukrainian prices, indicated by Zernotorg. In some periods, the discrepancies were as high as 40% ().

4.3. Spring sowing and demand for seeds

The challenging harvest, the changing prices and the ongoing blockade has profoundly affected spring 2022 corn sowing. In the most general terms, farmers opted for other, less risky crops. The Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine (Citation2022) provides the following figures: the area sown with corn has declined from 5140 thousand hectares in April-May 2021, to 4405 thousand hectares of corn for the same period in 2022. Experts estimate that about a third of corn has been replaced by other crops (Forbes Citation2022).

When adjusting their sowing plans, agricultural producers are guided by cost–benefit calculations. According to Yuriy Kernasyuk, an agricultural expert, agribusiness decisions to reduce the sown area of corn are adaptations to new economic realities:

Reducing the area under corn by more than 1 million tons is economically justified and does not pose a threat to food security. Farmers will save at least UAH 22 billion on corn, or approximately UAH 22,000 per 1 ha.Footnote9 Thanks to this, it will be possible to sow 1.5 hectares of buckwheat or millet, the demand for which will be increased this and next year.Footnote10

With war-related disruptions, Monsanto/Bayer and other seed companies were faced with significant surplus seeds and some of the plants started distributing seeds to local farmers as part of their charitable initiatives. Monsanto Seeds has reportedly donated 140 tons of corn seeds to about 150 farms in the Zhytomyr region (Gavriluk Citation2022), as well as a significant amount to farmers in the Mykolaiv region , and in the Odessa region, to name but a few. Mykhailo Kliuchevych, a leading agronomist, explained this trend as follows (Gavriluk Citation2022):

[T]he Monsanto plant was built to produce up to 875,000 sowing units of DEKALB corn seeds annually for about 2.5 thousand of the company’s customers in Ukraine. With the outbreak of the war, Monsanto was unable to stop its production, could not store seeds for a long time, and was unable to export seeds in such quantities. Free distribution of its seeds was the only solution. However, it was not only charity, but also a way to advertise their products to potential new customers. There have also been instances when Monsanto provided its seeds on an interest-free loan: […] Monsanto gave seeds and then bought finished products – grain – from farmers at certain prices.Footnote11

On the one hand, this is due to the loss of logistical channels for the supply of seeds from abroad due to the large-scale aggression of Russia […]. [O]n the other hand, [it is related to the] increase in production at our own capacities of domestic seed plants. In addition, the recognition by the European Parliament of the Ukrainian seed certification system allowed Ukraine for the second year in a row to increase the export of seeds, primarily to the EU countries.Footnote12

4.4. Fall harvest

The changing economies of corn production has profoundly impacted the 2022 harvest and sowing cycle. The 2022 harvest season was extremely challenging for all Ukrainian farmers, but corn producers likely are experiencing the most significant losses. Several factors contributed to the increase in the costs of harvesting corn, which meant that approximately a third of the corn was left in the fields for the winter, a practice known as zymivlya (wintering). Although wintering of corn is not an uncommon practice, the share of corn left in the fields was the largest in decades (Yarmolenko and Lebid Citation2022). The reasons for the corn wintering are the combination of the following weather and war-related trends: (1) a rainy fall, which drenched fields and crop and did not allow timely harvest and also necessitated the drying of corn; (2) high fuel and energy costs and interruptions in the power supply of elevators and dryers due to the war-caused destruction of Ukraine’s power system; (3) shelling from Russia in some regions of Ukraine. The combination of high harvesting and drying costs and low market prices for corn led farmers to re-consider whether to harvest corn before the winter or wait until spring.Footnote13

One farmer, Viktor Galich, owner of the large farm enterprise that operates on 200 hectares and cultivates soybeans, sunflowers, corn, and vegetables, describes the challenging fall harvest and the losses he anticipates as follows:

We started harvesting 10 days ago, the weather did not allow [it] earlier, the humidity was 19–20%. On the 14th of December, 15 cm of snow fell, so the harvesting was over for us. Now we have to wait until spring. […] We are facing serious losses. Last year we sold corn for 5.5–6 thousand hryvnias per ton, and now the price is 2.7 thousand hryvnias per ton, but even at this price we cannot sell. Electricity is cut off constantly, sometimes it is on only for 2–4 h a day. There is no way to properly winnow and dry the corn. Consequently, due to humidity, every third or fourth wagon leaves the elevator with mold and fungus on corn. […] No one will pay more than 650–700 hryvnia per ton for such corn. Our rent is higher than this, and we still have to pay back [the credit] for a [recently bought] combiner. […] We will start harvesting in April, but it is difficult to say what condition the corn will be at that time. Perhaps it can only be sold to the [neighboring] distillery, which buys corn for alcohol at about 10 hryvnia per ton.Footnote14

5. Coping strategies; domestic processing and the future of Ukrainian corn

With the changing economies of corn, agribusinesses are adjusting their practices and considering new strategies to meet changing market dynamics and political threats. We see both temporary coping strategies that seek to reduce the staggering losses, and attempts to formulate future-oriented strategies that rethink Ukraine’s role in the global food system. For the latter, agribusinesses are considering alternative export routes and new ways to build long-term capacity for domestic processing and for alternative domestic use of corn. Some food producers are also shifting to barley and high-margin niche crops, although by most accounts these commodities will not displace corn as the ‘queen of the fields’.

5.1. Alternative and domestic uses for corn

As the Black Sea blockade imperiled exports, Ukrainian farmers sought alternative export routes. Svitlana Lytvyn, agricultural expert from the Ukrainian Agribusiness Club, noted that ‘with the outbreak of war, due to the blocking of sea routes, significant logistical difficulties arose. Ukraine had to build alternative export routes almost from scratch.’Footnote17 Transporting corn by train and road is costly and limited, which meant that other farmers sought ways to process corn domestically. These alternatives initially involved local and small-scale solutions. Some Ukrainian enterprises have used parts of harvested corn as biofuel. In response to the widespread damage to Ukraine’s energy infrastructure, farmers in the Sumy regions use corn in heat generators (Latifundist Citation2022). Ivan Chaykivsky, a representative of the Agrarian Party of Ukraine in the Sumy region, is in favor of practice and has argued that the war will encourage farmers to look for new, more sustainable ways of production and processing:

The current situation motivates agribusiness to develop corn processing. Today, when logistics costs 2.5 thousand [hryvnias] per ton, and farmers could sell their corn for only 10 hryvnias per ton, it becomes unprofitable to sell raw materials. Thus, processing corn into the final product is the only way out. Therefore, many agricultural producers are interested, studying and looking for ways to create added value.Footnote18

5.2. Shift to other commodities and other ways of growing corn

The difficulties with marketing corn have also led some Ukrainian farmers to shift away from corn and plant high-margin niche crops. Ukrainian farmers opted for barley, buckwheat, and peas, which are currently in high demand in the domestic market, as they are edible crops, unlike corn, which is a commodity crop and animal feed (Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine Citation2022). The amount of land under buckwheat has increased since the beginning of the war: in 2021, about 51 thousand hectares of buckwheat were sown in April-May, it was nearly 58 thousand hectares for the same period in 2022 (Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine Citation2022). Farmers are also shifting to high-margin niche crops, such as chickpeas, peas, berries, mustard, medicinal herbs. At the same time, it is not clear whether these shifts to other commodities will help solve the problems created by the war. Not only do they require different inputs, they may also be sensitive to the agrochemicals that have been applied to corn fields.

It is generally expected that wheat, corn and sunflower will remain the leading crops of Ukrainian agriculture and that corn will remain the dominant export commodity (Kravchenko Citation2022). Andrii Dankevych argues that though many agricultural producers are considering alternatives to corn, they are not easy to implement:

[Replacing corn with other crops] is not an easy choice for many agribusinesses because the technology was developed for corn, equipment was bought for corn, corn is an easy-to-grow crop, and is paired with sunflower in crop rotation. Therefore, next year, a significant part of farmers will continue growing corn, despite the war, unprofitable logistics and high energy prices, although in smaller quantities. On the other hand, Europe is not able to grow enough corn for its own needs. This is a favorable situation for Ukraine to export its harvest [to Europe].Footnote21

Ukrainian corn is still viewed by Ukrainian and multinational businesses as a ‘cash cow,’ bringing high profits even in times of uncertainty. In April 2023, Monsanto/Bayer announced a major investment in Ukraine, to extend the capacity of a corn seed production facility Pochuiky, despite the risks of an ongoing war and trade disruptions (Bayer Citation2023). According to our interviews with agribusiness representatives, experts, and policy makers, most of them believe that corn would be a source of funds to support the ruined domestic economy, help restore Ukrainian agribusiness and repair damaged infrastructure. Corn exports will likely also play an important role in Ukraine’s post-war recovery, something that the Ukrainian government will encourage. Mykola Stryzhak, the former president of the Association of Farmers and Private Landowners of Ukraine, also believes that large agribusiness will continue to dominate Ukrainian agriculture, since these businesses have a strong lobby in government and many governmental authorities have tight connections with large-scale industrial agribusiness.Footnote22 As global demand and prices for corn will remain high, profits and foreign currency that are generated from exports will strongly encourage Ukrainian farmers to cultivate corn on large parts of the country’s fertile farmland.

5.3. Ukrainian farms and the EU

Ukraine’s integration into the EU will have tremendously important consequences for the country’s agriculture, and corn production in particular. Should Ukraine follow a traditional path of full membership, the EU will likely require stricter control of GMO use, which in turn will likely reduce the reliance on these seeds. EU integration may also have more profound, structural implications for the Ukrainian farm system. It is possible that the EU’s farmer-centric model will impose restrictions on the unchecked expansion of large agribusiness, and it is possible that the EU will limit the participation of agroholdings in post-War rural recovery programs (Kravchenko Citation2022). The entry of Ukrainian agribusiness to the European Common Agricultural Market will certainly require that they implement European requirements for balanced nature management, sustainable land use and the reduced reliance on monoculture. This means that Ukrainian authorities will likely seek to regulate methods of growing corn, enhance crop rotations, reduce the use of chemical fertilizers and pesticides, and also encourage a move away from the production of monocultures.

As these changes may reduce corn yields and profitability, they will confront Ukrainian policy makers and agroholding companies with a dilemma: continue large-scale export-oriented industrial production of corn to generate money for the domestic economy and business recovery, or follow EU standards for full integration into the EU system and market.

6. What does the Ukraine story tell us about the resilience of the globalized neoliberal agricultural model?

Ukrainian corn production and exports before and during the first year of the war with Russia demonstrate the vulnerability of globalized neoliberal agrarian structures to exogenous shocks and disturbances. Indeed, Ukrainian corn provides an excellent example of how war-related disruptions have affected the global food system at the three levels of concentration that Jennifer Clapp highlights – on fields, at the national and global levels (Clapp Citation2022).

On fields, the war showed how over-reliance on the export of one monoculture as an agricultural raw material can be detrimental to farmers. While corn was a ‘cash cow’ for Ukrainian agribusiness over the last decade, it became a major burden during the first months of the war. Destroyed infrastructure and storage facilities and the Black Sea naval blockade resulted in a glut of corn in the domestic market, serious storage problems, crop damages, and an oversupply of corn seeds.

At the national level, the war-related damages exposed the dependence of the Ukrainian economy on grain exports. War-related price disruptions also exposed discrepancies between world corn prices and domestic Ukrainian corn prices, demonstrating that agricultural commodity prices are largely untethered from production costs, instead fluctuating in response to a myriad of global forces.

Finally, at the global level, the war demonstrated the world’s dependence on Ukraine as a key grain exporter. In Ukraine and across the globalized agrifood value chain, actors were forced to adjust to disruptions in the global food trade. Our research documents the adaptation strategies of Ukrainian and multinational corn producers. These involved seeking new ways to store corn, discovering new trade routes, initiating processing of corn into the final product, diversifying production, and replacing corn with other crops. All this allowed Ukrainian agribusinesses and global actors based in Ukraine to survive and persist during the first year of the war.

The recent major disturbances in the global food system caused by Covid-19 and the war in Ukraine has revived the ‘classic agrarian question’ but in reverse, interrogating whether capitalist agriculture (rather than the peasant mode of production) will survive and persist in the current turbulent times, or will it need to be converted to (or replaced by) localized agriculture with the peasant logic of production? Recent studies have shown that localized food systems are more resilient to global shocks and disturbances as they do not depend on external resources and international trade (see Mamonova Citation2022, also see Béné Citation2020 on resilience of local food systems in times of Covid-19).

Although it is still too early to draw definite conclusions, our findings to date suggest agribusiness resilience. We see that Ukrainian agroholdings have so far been able to adapt to the extremely serious disruptions caused by the war: they winterize corn, experiment with other crops, and devise plans to invest in domestic processing and new ways to integrate into European markets. This confirms Frederick Buttel’s (Citation2006) assertion about the ability of industrial ‘unsustainable’ agriculture to remain viable for a long period despite environmental challenges, risks, and disasters. Corporate farms have used their advantages in size, scale, market domination, and access to finance and technology, along with proximity to policymaking, to deliver desired outcomes without changing their market-capitalist logic of production. Indeed, one global actor, Monsanto/Bayer, has used the crisis to deepen its relationship to Ukrainian farms: distributing free corn seeds will likely expand its customer base in the future.

While we thus see considerable adaptation and resilience, corporate forces are not alone in setting the rules of the game, but rather react to external shocks generated by a belligerent state. This trend suggests that renewed attention to the role of military power in the corporate food regime is called for. Friedman and McMichael (Citation1989) noted the role of military power in the establishment of the ‘first food regime’ that accompanied the rise of European colonial empires in the eighteenth and nineteenth century. Either administered by the bureaucracies of the metropolitan states, or ‘outsourced’ to private actors, as in the case of chartered trading companies. Physical force, wielded by states and empires, was an integral part of hegemonic power in the colonial era (Friedman and McMichael Citation1989, 97). In the era of the transnational restructuring in the post-WWII period, Friedman and McMichael no longer explicitly discuss these features of the US-dominated hegemonic order, though they are in many ways implied in the discussion of the Cold War-era global trade regime.

The emphasis on corporate power in the theories of transnational food systems and the apparent weakening of states in enacting protectionist policies have obscured the exceedingly important role of geopolitical considerations have consistently shaped food and agricultural policies of hegemonic states. This is the case for the Soviet Union and the US, most obviously, but China and many other countries have conducted foreign policies that seek to guarantee food security, help farmers at home, or pursue other aims. While it is beyond the scope of this article to review these histories and the theoretical debates surrounding geopolitics and food, we want to end with a call for renewed attention to such questions, particularly in light of the globalization of Ukrainian corn and the ongoing Russian aggression.

What are the implications of the war damage and the Black Sea blockade for how we think about the vulnerabilities of food systems? We hope that our research can serve as a starting point for answers to this question: Russia’s military intervention and the harm it has wrought on Ukrainian farms shows the need to examine how military action can destroy productive capacity and how naval power can disrupt trade. We can no longer afford to take for granted that regional and global hegemons will support the increasing globalization of agricultural trade. Instead, they may strategically use food-related dependencies as a way to enlist loyal partners in global politics. While corporate actors are indeed powerful actors, it would be a mistake to assume that all states are subservient in the contemporary corporate food regime.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank and express their gratitude to Ukrainian farmers and agribusiness representatives, who continue to produce food for Ukraine and the world, despite the risks and hardships of war. We would like to thank Mykola Stryzhak, Andrii Dankevych, Svitlana Lytvyn, Mykhailo Kliuchevych and other informants for taking the time and opportunity during the war to answer our questions and provide valuable feedback on our findings. We would also like to thank two anonymous reviewers for comments on earlier drafts, and Marko Gural and Jing Li for research assistance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s ).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Natalia Mamonova

Natalia Mamonova is a senior researcher at RURALIS The Institute for Rural and Regional Research, Norway. Her research focuses on rural politics, agrarian transformation, social movements, food sovereignty and right-wing populism in post-socialist rural Europe. She received her PhD degree from Erasmus University, the Netherlands in 2016. Since then, she was a researcher/lecturer at the University of Oxford, the New Europe College in Bucharest, the University of Helsinki, and the Stockholm Centre for Eastern European Studies. Her current research at RURALIS is primarily focused on the impact of the war in Ukraine on the Ukrainian and global food systems.

Susanne Wengle

Susanne A. Wengle is NR Dreux Associate Professor of Political Science at the University of Notre Dame, with a Ph.D. from the University of California Berkeley. Her research examines Russia’s post-Soviet political and economic transformation and engages with questions how we study market creation in this context and beyond. She is the author of Post-Soviet Power: State-led Development and Russia’s Marketization (Cambridge University Press, 2015), Black Earth, White Bread; a technopolitical history of Russian Agriculture and Food (University of Wisconsin Press, 2022) and the editor of Russian Politics Today: Stability and Fragility (Cambridge University Press, 2022), as well as numerous articles on the social, political and economic dynamics of the post-Soviet transformations.

Vitalii Dankevych

Vitalii Dankevych is Dean of the Faculty of Law, Public Administration and National Security at Polissia National University in Zhytomyr, Ukraine, where he is also a professor at the Department of International Economic Relations and European Integration. He worked as a consultant of the project ‘Capacity Development for Evidence-Based Land and Agricultural Policy Making’, World Bank (2018) and in the project ‘Supporting Transparent Land Governance in Ukraine’, World Bank, EU (2019). He is a member of Global Learning in Agriculture community. His research investigates agrarian economies and land relations in Ukraine, as well as the impact of the Russian war against Ukraine on global food security.

Notes

1 The research for this article was conducted in 2022 and concluded in February 2023, and should therefore be understood as an early and preliminary assessment. We have not been able to conduct research on the consequences of the explosion of the Kakhova dam on 6 June 2023. The floods, the draining of the Kakhovka reservoir, and the destruction of agricultural infrastructure that resulted from it will have long-lasting consequences for Ukrainian agriculture that will need to be assessed by future research.

2 In a first, transitional stage, starting on 1 July 2021, individuals, but not legal entities, could buy up to 100 hectares of farmland. The transitional period was designed to allow small local farmers to buy the land first and give access to the market for larger companies afterwards. After 2024, both individuals and legal entities will be allowed to purchase up to 10,000 hectares of land (Verkhovna Rada Citation2020).

3 Interview with Mykhailo Kliuchevych, December 9, 2022, Zhytomyr, Ukraine, conducted by Vitalii Dankevych.

4 In the Soviet period, kolkhozy and sovkhozy were largely responsible for the economic and social development of rural areas. Their successors – large agricultural businesses – have taken over the lands of the former state-owned farms, and with them some of the socio-economic and cultural functions. For example, big businesses often patronize rural schools and cultural centers, eventually repair rural infrastructure, or offer lower prices for their products to the local population as part of their corporate social responsibility programs.

5 Interview with Mykhailo Kliuchevych, professor at Polissia National University, December 9, 2022, Zhytomyr, conducted by Vitalii Dankevych.

6 Interview with Mykola Kosolap, professor at National University of Life and Environmental Sciences of Ukraine, quoted in Karpenko (Citation2019).

7 Interview with Mykola Aparin, June 2012, village Hreblya, Pereyaslav-Khmelnitsky district, conducted by Natalia Mamonova.

8 The benchmark wheat price on the Chicago Stock Exchange rose 5% after Russia threatened to block ports again in October 2022. Prices will rise even more if Ukrainian grain falls out of the world market again. In the spring, this caused the price of wheat to rise by 50% (Miroshnochenko and Gopdijchuk Citation2022).

9 UAH 22,000 equaled approximately USD 595 in early 2023.

10 Interview with Yuriy Kernasyuk, published in Dzyabyak and Kravets (Citation2022).

11 Interview with Mykhailo Kliuchevych, professor at Polissia National University, December 9, 2022, Zhytomyr, conducted by Vitalii Dankevych.

12 Interview with Oleksandr Zakharchuk, Institute of Agrarian Economics of the National Academy of Sciences of Ukraine, published in Dzyabyak and Kravets (Citation2022).

13 Interview with Andrii Dankevych, a financial director of an agricultural enterprise which is part of a large agricultural holding; December 16, 2022 conducted by Vitalii Dankevych.

14 Interview Viktor Galich, the owner of the farm enterprise ‘Hospodar,’ published in Yarmolenko and Lebid (Citation2022).

15 Interview with Andrei Dankevych, December 16, 2022, conducted by Vitalii Dankevych.

16 Email exchange with Svitlana Lytvyn, agricultural expert, UCAB, Ukrainian Agribusiness Club, December 22, 2022, conducted by Susanne Wengle.

17 Svitlana Lytvyn, ibid.

18 Interview with Ivan Chaykivsky, a representative of the Agrarian Party of Ukraine in the Sumy region, published in Latifundist (Citation2022).

19 Interview with Roman Leshchenko, the former Minister of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine, published in Latifundist (Citation2021).

20 Interview with Serhiy Krolovets, a Ukrainian agricultural expert, quoted in Landlord (Citation2022).

21 Interview with Andrii Dankevych, financial director of an agricultural enterprise, December 16, 2022, conducted by Vitalii Dankevych.

22 Mykola Stryzhak, the former president of the Association of Farmers and Private Landowners of Ukraine, January 9, 2023, conducted by Natalia Mamonova.

References

- AgroFund. 2022. Accessed December 2, 2022. http://agrofond.gov.ua.

- Agronews. 2022. “Війна в Україні впливає на світовий ринок кукурудзи” [The war in Ukraine affects the global corn market]. Accessed November 16, 2022. https://agronews.ua/news/vijna-v-ukrayini-vplyvaye-na-svitovyj-rynok-kukurudzy/.

- Akram-Lodhi, A. H., K. Dietz, B. Engels, and B. M. McKay, eds. 2021. Handbook of Critical Agrarian Studies. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- APK-Inform. 2022. “В Україні стрімко дешевшає кукурудза” [In Ukraine, the price of corn is falling rapidly]. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://www.apk-inform.com/uk/news/1527996.

- Applebaum, A. 2018. Red Famine: Stalin’s War on Ukraine. New York: Anchor Books.

- Bayer. 2018. “Bayer Opens State-of-the-Art Seed Processing Facility in Ukraine.” Accessed 30 January 30, 2023. https://latifundist.com/en/novosti/41443-bayer-otkryl-semennoj-zavod-v-zhitomirskoj-oblasti.

- Bayer. 2023. “Bayer to Invest a Total of 60 Million Euros in Its Ukrainian Seed Production Site.” Accessed June 19, 2023. https://www.bayer.com/media/en-us/bayer-to-invest-a-total-of-60-million-euros-in-its-ukrainian-seed-production-site/.

- Béné, C. 2020. “Resilience of Local Food Systems and Links to Food Security – a Review of Some Important Concepts in the Context of COVID-19 and Other Shocks.” Food Security 12 (4): 805–822. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12571-020-01076-1.

- Bessonova, E., O. Merschenko, and N. Gridchina. 2015. “Ukraine in the WTO: Effects and Prospects.” Romanian Journal of European Affairs 15 (3): 66–83.

- Braun, K. 2022. “Ukraine’s Unmatched Corn Crop Gains Encroach on Rival Exporters.” Reuters. Accessed November 3, 2022. https://www.reuters.com/markets/commodities/ukraines-unmatched-corn-crop-gains-encroach-rival-exporters-2022-02-17/.

- Buttel, F. H. 2006. “Sustaining the Unsustainable: Agro-Food Systems and Environment in the Modern World.” In The Handbook of Rural Studies, edited by P. Cloke, T. Marsden, and P. H. Mooney, 213–229. London: Sage.

- Clapp, J. 2014. “Financialization, Distance and Global Food Politics.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (5): 797–814. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2013.875536.

- Clapp, J. 2022. “Concentration and Crises: Exploring the Deep Roots of Vulnerability in the Global Industrial Food System.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 50 (1): 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2022.2129013.

- Clapp, J., and W. G. Moseley. 2020. “This Food Crisis is Different: COVID-19 and the Fragility of the Neoliberal Food Security Order.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 47 (7): 1393–1417. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2020.1823838.

- Csaki, C., and Z. Lerman. 1997. “Land Reform and Farm Restructuring in East Central Europe and CIS in the 1990s: Expectations and Achievements After the First Five Years.” European Review of Agricultural Economics 24 (3–4): 428–452. https://doi.org/10.1093/erae/24.3-4.428.

- Dankevych, V., Ye Dankevych, V. Naumchuk, and A. Dankevych. 2021. “Approaches to Modeling of Land Use Development Scenarios in Order to Diversify Agricultural Production [in the Context of Land Reform].” Zeszyty Naukove 2:97–122.

- Deininger, K., and D. Byerlee. 2011. “Rising Global Interest in Farmland: Can It Yield Sustainable and Equitable Benefits?” World Bank Publications. Accessed August 8, 2023. https://documents1.worldbank.org/curated/en/998581468184149953/pdf/594630PUB0ID1810Box358282B01PUBLIC1.pdf.

- Dzyabyak, G., and V. Kravets. 2022. Посівна в умовах війни: чому аграрії замість кукурудзи посіяли соняшник, сою та гречку [Sowing during the war: why farmers sowed sunflowers, soybeans and buckwheat instead of corn]. Accessed September 4, 2023. https://www.growhow.in.ua/posivna-v-umovakh-viyny-chomu-ahrarii-zamist-kukurudzy-posiialy-soniashnyk-soiu-ta-hrechku/.

- Edelman, M., T. Weis, A. Baviskar, S. M. Borras Jr, E. Holt-Giménez, D. Kandiyoti, and W. Wolford. 2014. “Introduction: Critical Perspectives on Food Sovereignty.” Journal of Peasant Studies 41 (6): 911–931. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.963568.

- Elevatorist. 2021. “Глобальна кукурудза: тримати чи продавати царицю полів” [Global corn: Keep or sell the queen of the fields]. Accessed December 15, 2022. https://elevatorist.com/blog/read/743-globalnaya-kukuruza-derjat-ili-prodavat-tsaritsu-poley.

- Fedorchuk, A. 2014. “Кладіть вологе зерно в мішки” [Put wet grain in bags]. AgroTimes. Accessed November 26, 2022. https://agrotimes.ua/article/kladit-vologe-zerno-v-mishki/.

- Forbes. 2022. “Величезні пакети, мобільні склади та заміна кукурудзи. Як Україна зберігатиме своє зерно, яке не може вивезти” [Huge bags, mobile warehouses and corn replacement. How Ukraine will store its grain, which it cannot export]. Accessed January 5, 2023. https://forbes.ua/inside/de-ukraina-zberigatime-svoe-zerno-rozvidka-the-economist-28062022-6860.

- Friedman, H., and P. McMichael. 1989. “The Rise and Decline of National Agricultures, 1870 to the Present.” Sociologia Ruralis 29 (2): 93–117. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9523.1989.tb00360.x.

- Friedmann, H. 2004. “Feeding the Empire: The Pathologies of Globalized Agriculture.” In Socialist Register 2005: The Empire Reloaded, edited by L. Panitch and C. Leys, 124–143. London: Merlin Press.

- Gagalyuk, T., V. Valentinov, and F. Schaft. 2018. “The Corporate Social Responsibility of Ukrainian Agroholdings: The Stakeholder Approach Revisited.” Systemic Practice and Action Research 31 (6): 675–698. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11213-018-9448-9.

- Galperina, L. 2014. “Main Challenges of Agriculture of Ukraine in Globalization.” European Researcher 87 (11-2): 1996–2004. https://doi.org/10.13187/er.2014.87.1996.

- Gavriluk, A. 2022. “Аграрії Житомирщини отримають безкоштовно 140 тонн насіння кукурудзи” [Agrarians of Zhytomyr region will receive 140 tons of corn seeds for free]. AgroTimes. Accessed December 28, 2022. https://agrotimes.ua/agronomiya/agrariyi-zhytomyrshhyny-otrymayut-bezkoshtovno-140-tonn-nasinnya-kukurudzy/.

- Graubner, M., and I. Ostapchuk. 2018. Efficiency and Profitability of Ukrainian Crop Production. Agricultural Policy Report. Kyiv: The Institute for Economic Research and Policy Consulting. Accessed December 14, 2022. https://www.apd-ukraine.de/images/APD_APR_01_2018_Efficiency_and_Profitability_of_Ukrainian_Crop_Production.pdf.

- Grigorenko, S. 2023. “Законопроєкт про ГМО ставить під загрозу аграрний експорт до ЄС” [The draft law on GMOs endangers agricultural exports to the EU]. Accessed June 16, 2023 https://www.epravda.com.ua/columns/2023/02/8/696813/.

- Hale-Dorrell, A. T. 2018. Corn Crusade: Khrushchev's Farming Revolution in the Post-Stalin Soviet Union. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Heinzen, J. W. 2004. Inventing a Soviet Countryside State Power and the Transformation of Rural Russia, 1917–1929. Pittsburgh, PA: University of Pittsburgh Press.

- Hellyer, M., and V. Pyatnitsky. 2013. “Selling to the EU under the DCFTA.” CTA Economic & Export Analysts.

- Karpenko, A. 2019. “Географія, врожайність, площі: як змінилося вирощення топових культур за роки Незалежності?” [Geography, productivity, areas: how has the cultivation of top crops changed during the years of Independence?]. Agravery. Accessed December 10, 2022. https://agravery.com/uk/posts/show/geografia-vrozajnist-plosi-ak-zminilos-virosuvanna-topovih-kultur-za-roki-nezaleznosti.

- Karpyshin, Y. A. 2019. State regulation of agricultural holdings in Ukraine. Zhytomyr: Zhytomyr National Agroecological University of the Ministry of Education and Science of Ukraine.

- Khvorostyanyi, V. 2022. “Ринок зерна 2022 — прогнози: кукурудза, пшениця, соняшник, ячмінь” [Grain market 2022 – forecasts: corn, wheat, sunflower, barley]. AgroPolit. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://agropolit.com/spetsproekty/946-rinok-zerna-2022–prognozi-kukurudza-pshenitsya-sonyashnik-yachmin.

- Kravchenko, V. 2022. “Сутінки агрохолдингів: як війна змінить сільське господарство України” [The twilight of agricultural holdings: How the war will change the agriculture of Ukraine]. Mind. Accessed November 28, 2022. https://mind.ua/publications/20245288-sutinki-agroholdingiv-yak-vijna-zminit-silske-gospodarstvo-ukrayini.

- Kuns, B., and O. Visser. 2016. “Towards an Agroholding Typology: Differentiating Large Farm Companies in Russia and Ukraine.” Paper Presented at the 90th Annual Conference of the Agricultural Economics Society, University of Warwick, Coventry, England, 4–6 April.

- Kvitka, H. 2021. “Науковці: ми справді велика аграрна держава” [Scientists: We are really a great agrarian state]. Voice of Ukraine. Accessed January 5, 2023. http://www.golos.com.ua/article/346504.

- Landlord. 2022. “Переробка кукурудзи може приносити 14% чистого доходу” [Corn processing can generate 14% of net income]. Accessed December 7, 2022. https://landlord.ua/news/pererobka-kukurudzi-mozhe-prinositi-14-chistogo-dohodu/.

- Lapa, V., A. Lyssitsa, A. Polyvodsky, and M. Fedorchenko. 2007. “Украина: Агрохолдинги и перспективы рынка земли” [Ukraine: Agroholdings and Prospects for the Land Market]. Ukrainian Agrarian Confederation, Ukragroconsult.

- Latifundist. 2021. “Світовий ринок кукурудзи 2021 і українські реалії: від глобального до локального” [World corn market 2021 and Ukrainian realities: from global to local]. Accessed December 2, 2022. https://latifundist.com/analytics/27-svtovij-rinok-kukurudzi-2021–ukransk-real-vd-globalnogo-do-lokalnogo.

- Latifundist. 2022. “Експерти розповіли про доцільність використання зерна кукурудзи в якості палива” [Experts spoke about the feasibility of using corn grain as fuel]. Accessed December 3, 2022. https://latifundist.com/novosti/60026-eksperti-rozpovili-pro-dotsilnist-vikoristannya-zerna-kukurudzi-v-yakosti-paliva.

- Lerman, Z., Y. Kislev, D. Biton, and A. Kriss. 2003. “Agricultural Output and Productivity in the Former Soviet Republics.” Economic Development and Cultural Change 51 (4): 999–1018. https://doi.org/10.1086/376884.

- Leshchenko, R. 2021. “Монокультура кукурудзи – розуміння ризиків та перспектива прибутків” [Corn monoculture – understanding the risks and the prospect of profits]. Agropolit. Accessed December 16, 2022. https://uga.ua/meanings/monokultura-kukurudzi-rozuminnya-rizikiv-ta-perspektiva-pributkiv/.

- Lotysh, O. Ya. 2021. “The Use of Matrix Methods in the Strategic Analysis of the Grain Industry of Ukraine.” Business-Navigator Scientific and Industrial Magazine on Economics 2 (63): 36–44.

- Mamonova, N. 2015. “Resistance or Adaptation? Ukrainian Peasants’ Responses to Large-Scale Land Acquisitions.” Journal of Peasant Studies 42 (3–4): 607–634. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2014.993320.

- Mamonova, N. 2022. “Food Sovereignty and Solidarity Initiatives in Rural Ukraine During the War.” Journal of Peasant Studies 50 (1): 47–66. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2022.2143351.

- Maruniak, E., S. Lisovskyi, O. Holubtsov, V. Chekhnii, Y. Farion, and M. Amosov. 2021. “Research into Impacts of Agricultural Land Concentration on Ukrainian Environment and Society.” Ekodia. Accessed November 29, 2022. https://en.ecoaction.org.ua/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/zemlia_en2021_06.pdf.

- Matvienko, V. M., and Ya. V. Sonko. 2016. “History of the Development of the Grain Economy of Ukraine.” Journal of Cartography 14:279–290.

- McMichael, P. 2009a. “A Food Regime Genealogy.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 36 (1): 139–169. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150902820354.

- McMichael, P. 2009b. “A Food Regime Analysis of the ‘World Food Crisis’.” Agriculture and Human Values 26:281–295. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10460-009-9218-5.

- McMichael, P. 2012. “The Land Grab and Corporate Food Regime Restructuring.” The Journal of Peasant Studies 39 (3–4): 681–701. https://doi.org/10.1080/03066150.2012.661369.

- Ministry of Agrarian Policy and Food of Ukraine. 2022. “Через воєнне вторгнення посівні площі зменшилися на 25%” [Due to the military invasion, the cultivated area decreased by 25%]. Accessed January 30, 2023. https://minagro.gov.ua/news/cherez-voyenne-vtorgnennya-posivni-ploshchi-zmenshilisya-na-25.