ABSTRACT

The increasingly dynamic and complex higher education (HE) environment calls for high levels of boundary-spanning skills from leaders. The importance of boundary spanning is raised by the need for leaders to engage across internal and external boundaries to formulate new strategic responses to a complex set of forces and pressures facing the sector. This paper investigates the salience of boundary spanning leadership (BSL) practices through qualitative research on a group of leaders in one UK HE institution. The paper finds varying evidence for the range of boundary-spanning activities proposed in previous literature and concludes in the present case that leadership achieves the ‘managing boundaries’ stage of the BSL nexus, but has more limited achievement at the highest ‘discovering new frontiers’ stage.

Introduction

Higher education (HE) in the UK in the second decade of the twenty-first century faces a ‘perfect storm’ of external challenges and pressures (Lumby Citation2012) This has resulted in increased questioning of the relevance of the traditional understanding of the defining boundaries of a ‘university’, and discussion on appropriate strategic stance (PA Consulting Citation2008; Barnett Citation2011; Brown and Carasso Citation2013). Embedded here are a number of drivers of change, each one with significant ramifications at leadership levels throughout HE organizations. In turn this leads to implications for the salience of new and enhanced leadership skills.

One highly relevant conceptualization is that of the boundary spanning leadership (BSL) ‘nexus’ effect. This has attracted limited attention to date in the literature on HE leadership. We argue for its relevance in addressing current challenges in HE. It merits attention because it resonates with internal and external stakeholder engagement in the strategizing of new responses to complex external challenges (Burkhardt Citation2002). The paper presents a grounding of the BSL approach in the UK HE context. From this we identify two key research questions concerning firstly the nature of those inter-organizational and external stakeholder boundaries which HE leaders perceive to be acting on their leadership practice, and secondly the extent of opportunities for the use of those leadership practices conceptualized in the BSL approach (Ernst and Yip Citation2009; Ernst and Chrobot-Mason Citation2011), as HE leaders navigate their roles in the current challenging HE context.

The analysis in the paper is an initial assessment undertaken though detailed semi-structured interviews with five leaders, working across a range of academic and support functions in a UK HEI, conducted in 2014–2015. At the lower end of the BSL conceptual ‘nexus’ we find good evidence for the use of group identity constructing and intergroup connecting tactics while the higher tactics relating to new group mobilization in pursuit of fresh strategic responses and objectives are much less prevalent. This has implications for higher levels of leadership skill development at intermediate management levels in HE. The remainder of the paper is structured as follows. The next section provides background discussion on current external drivers acting on HE in the UK, the relevance and grounding of BSL to this context and frames the research questions of interest. A further section describes the choice of methodology and the investigation conducted. Findings are then presented, followed by discussion and assessment. The paper ends with a brief conclusion.

Background and overview

The underlying drivers of change and complexity in UK HE are in themselves complex and multifarious. However, they might usefully be summarized under the following five headings.

Changing business models

Key driver: The rapid and significant removal of government block grant funding of student feesFootnote1 which has resulted in reliance on a marketized environment where financial success follows from winning fee income for enrolling students.

Implications for performance: Many HEIs have responded by stimulating and encouraging ‘entrepreneurial’ leadership and strategizing (Clarke Citation2004; Shattock Citation2009; Barnett Citation2011; Gibb et al. Citation2012). This has raised attention on student recruitment, retention and satisfaction targets, and may be further sharpened by the likely implications of UK exit from the EU for student recruitment and research funding.

Changing regulatory environment

Key driver: the impact of current ambiguities about the future configuration of the UK HE quality assurance environment,Footnote2 and specifically a new regulatory framework focused on the Teaching Excellence Framework (TEF) and its attendant performance metrics.

Implications for performance: Decreased reliance on public funding has paradoxically accompanied increased emphasis on monitoring and compliance processes (Universities UK Citation2015). Other regulatory changes could raise further the challenge of competition from entirely private (and often for-profit) HE providers. Future changes are likely to move UK HE further away from the traditional model of peer review of quality assurance processes towards quantitative auditable metrics, with proposed implications for HEI freedom to set fee levels.

Internationalization

Key driver: The desire on the part of HEIs to grow income streams from non UK government-derived sources to fund investment and expansion.

Implications for performance: Levels of fee income derived from international students studying in UK HEIs have increased dramatically over the past two decades (Kelly, McNicoll, and White Citation2014). The UK’s traditionally strong positioning as an international student destination (Gibb et al. Citation2012) is now under threat from widening competition, from tighter regulation of student recruitment, and from implications of the UK’s exit from the European Union. This has raised attention on a range of new strategies including international programme partnering and franchising as well as overseas branch campus establishment, in search of student numbers and fee income.

External engagement, impact and knowledge exchange

Key driver: Developments in research assessment (now including focus on impact), governmental pressure to demonstrate research impact expressed via research funding councils, the potential for ‘entrepreneurial’ opportunities arising from commercial knowledge transfer and exchange, as well as demands to engage with employers-as-stakeholders to improve student employability.

Implications for performance: A growing burden on HEIs is to demonstrate instrumental economic value (McCaffrey Citation2010) measured across various metrics. Within this context, universities and academics may seek to negotiate a framing of their contribution in the wider perspective of ‘public value’ (Brewer Citation2013).

Impact of disruptive technologies in learning and teaching delivery

Key driver: The engagement with and adoption of new forms of learning and teaching delivery, which are in essence a response to competition from non-traditional, often for-profit learning providers. These are reshaping traditional learning delivery models (Kirkwood and Price Citation2005; Christensen and Eyring Citation2011). The arrival of massive open on-line courses (MOOCs) is one example of this (Yuan and Powell Citation2013), although technology-enhanced learning more widely is increasingly molding the student learning experience through market disruption both in terms of the range of providers and the nature of qualifications (McCaffrey Citation2010).

Implications for performance: More agile HEIs have opportunities to exploit competitive advantage through investment in technology to deliver curriculum change to suit market needs, focusing on access for part-time and other non-traditional students; the less agile may be placed at relative disadvantage (Lowendahl Citation2013).

This list is not intended to be exhaustive but illustrative of the range, pace and complexity of change in the sector. This range in turn brings considerable implications for leadership across the sector and at all levels. These implications might be framed in various ways (Bryman Citation2007, Citation2009), for example, the transition from management to leadership (Ramsden Citation1998), the need to embrace complexity (Parry Citation1998; Seale and Cross Citation2015), the increased need for planning activity and skills (Stark, Briggs, and Rowland-Poplawski Citation2002), or the increased salience of ‘soft’ leaderships skills such as consideration, communication and emotional intelligence (Knight and Holen Citation1985; Ambrose, Huston, and Norman Citation2005; Parrish Citation2015).

Addressing each of these drivers requires HE institutions and their leaders to identify and manage across a growing range of boundaries. Boundaries may exist across a number of domains including internally horizontal and vertical, horizontally with external stakeholders, and, cutting across each of these, may reflect geographical, cultural and demographic distance (Lee, Magellen Horth, and Ernst Citation2014). However, perceptions may be as important as realities. One popular explanation states that ‘boundaries that matter today are psychological and emotional in addition to organizational and structural’ (Cross, Ernst, and Pasmore Citation2013, 84). Within HE these boundaries define the distinct interests, objectives and responsibilities of a wide range of stakeholder relationships which includes regulatory bodies, government policy-makers, international partners, public and commercial knowledge exchange and research partners, as well as commercial bodies who may mediate the interface between universities and their students. They also define the internal organizational structures within universities. The imperatives and complexities underlying each of these drivers imply increasing levels of cross-functional negotiation on the part of universities’ own academic and professional service leaders.

Thus the range of leadership skills required in the HE environment might have converged on those found in other sectors, both private and public. On the other hand, some question the appropriateness of models framed in a corporate context for HE (Lumby Citation2012). The value of a range of popular approaches to leadership has been investigated, including situational leadership (McCaffrey Citation2010), transformational leadership (Ramsden Citation1998; Neumann and Neumann Citation1999; Pounder Citation2001), authenticity and credibility (Rantz Citation2002; Kennie Citation2010; Barnett Citation2011), distributed leadership (Gosling, Bolden, and Petrov Citation2009; Floyd and Fung Citation2015) and specific effective leadership traits, competencies and qualities (Bryman Citation2007; Bolden et al. Citation2012; Parrish Citation2015; Seale and Cross Citation2015).

Universities have had to adapt away from their existence as public-funded, but largely self-governing organizations (Brown and Carasso Citation2013), facing the predominant strategic objective of recruiting a target number of UK/EU-domiciled students, while managing their internal affairs within the budget envelope provided by that target. They have rapidly transformed into complex multi-product suppliers operating across a range of liberalized markets (Ollsen and Peters Citation2005), in which the leadership task has become one of negotiating and meeting competing claims for attention and resource to balance a scorecard of interdependent performance indicators (Lynch and Baines Citation2004; Labib et al. Citation2014). The tensions inherent in determining strategic priorities in this new climate present significant management and leadership challenges (Newton Citation2003) with implications for leadership development (Jones and Lewis Citation1991).

Boundary spanning, as developed in the work of the Center for Creative Leadership, provides, we argue, a highly appropriate lens through which to investigate the capacity of leaders in HE to address and engage with the strategic complexity of the current HE environment. It has been defined as ‘the capacity to establish direction, alignment and commitment across boundaries in service of a higher vision or goal’ (Yip, Ernst, and Campbell Citation2016, 3). Boundary spanning includes a range of functional and cognitive activities to bridge relationships with external stakeholders (Weerts and Sandmann Citation2010) as well as with internal partners and co-workers (Bolden et al. Citation2012). This can be further contextualized by considering the extent to which external partners influence or participate in the organization (Corwin and Wagenaar Citation1976). The leadership task therefore involves the bridging of that engagement. Boundary spanning may encompass knowledge transfer and exchange, with attendant challenges of translating knowledge that might be localized and embedded (Carlile Citation2002; Citation2004). Thus those for whom BSL skills are particularly salient might be found working on the periphery or the ‘edge’ (Leifer and Delbecq Citation1978; Weerts and Sandmann Citation2010).

As the requirements for collaboration increases, leadership roles require maintaining influence both internally and beyond the institution by leading and working across institutional, disciplinary and professional boundaries. This implies substantial shift away from the traditional formal and bureaucratic structures prevalent in many HEIs, and presents a major leadership challenge on both an institutional and an individual basis (Faraj and Yan Citation2009). Furthermore, some maintain that contemporary theories remain overly focused on traditional leader–follower relationships within defined structures and groups who share common values, interests and cultures (Yip, Wong, and Ernst Citation2008). In an academic HE context, in particular, this list might also include disciplinary language, ‘taken for granted’ assumptions and professional knowledge and identity. By contrast, newer perspectives such as BSL focus on mobilizing resource and knowledge from across and beyond the organization to promote collective solutions to complex problems (McGuire et al. Citation2009; Weerts and Sandmann Citation2010) with the capacity to bring fresh skills into the HE context (Peach et al. Citation2011).

Previous work has argued that boundary-spanning domains can be categorized in varying ways: organizational, spatial, cultural and attitudinal (individual perceptions of boundary flexibility), internal versus external, personal versus institutional (Miller Citation2008; Yip, Wong, and Ernst Citation2008; Ernst and Chrobot-Mason Citation2011). The skills and tactics required for effective BSL have also been explored in different ways (Lee, Magellen Horth, and Ernst Citation2014). However, in contrast to other popular models of leadership practice, boundary-spanning leaders may not necessarily display a prescribed set of personal characteristics and attributes (Miller Citation2008). By contrast effective leadership may be viewed as the task of engaging multiple, diversely positioned individuals in a common cause. By drawing on diverse expertise and cultural insight, it is argued that successful BSL employs cross-functional collaboration to achieve levels of innovation and change that narrowly focused functional groups might not in isolation (Yip, Ernst, and Campbell Citation2016).

The BSL literature proposes a hierarchy of six boundary-spanning practices: buffering, reflecting, connecting, mobilizing, weaving and transforming (Lee, Magellen Horth, and Ernst Citation2014). These support a conceptual understanding of leadership as a dynamic process or ‘nexus effect’ (Yip, Wong, and Ernst Citation2008) through which leaders establish direction, align others along that direction and build commitment to achieve shared transformational objectives, once established. provides an overview of the BSL nexus and, for each practice, summarizes context, key questions, leadership tactics and outcomes, drawing on the corpus of case study focused work conducted by the Center for Creative Leadership (CCL; Ernst and Chrobot-Mason Citation2011; Cross, Ernst, and Pasmore Citation2013; Lee, Magellen Horth, and Ernst Citation2014). The table also provides some indicative examples of BSL practices in universities. These practices range along a continuum from the creation of safe space in which organizational challenges can be identified and explored (‘buffering’ and ‘reflecting’), through practices which support conflict resolution and establishment of new, expanded group identities (‘connecting and mobilizing’), to practices (‘weaving’ and ‘transforming’) which support the re-imaging of fresh solutions and the achievement of innovation and change. The nexus effect, through which BSL practices cumulate for the achievement of organizational transformation, is illustrated here. This cumulative causation process is not necessarily linear, and engagement in higher order practices may necessitate a return to lower order practices as groups identities are stretched or placed under new strain or further need for re-assessment. therefore provides a conceptual framework for the application of BSL practices in the HE context, and a tool through which institutions can assess their level of boundary spanning maturity.

Table 1. BSL practices in HE.

From this framework two research questions are addressed in the analysis. The first is the question of the kinds of boundaries that HE leaders perceive to be acting on their leadership practice. The second is one of identifying the extent to which particular HE leaders are able to identify and articulate opportunities for the use of BSL leadership practices, as proposed above, when reflecting on current leadership contexts, roles and challenges.

Methods

The approach adopted in this paper is a qualitative one, based on in-depth semi-structured interviews from purposive sampling of a small number of academic and professional service department leaders. This was chosen as appropriate because leadership in HE is not standardized and therefore easily amenable to exploration using a formal survey questionnaire (Bryman Citation2015). Subjects were selected on the basis that their roles ex ante might involve significant levels of internal and external stakeholder engagement, and who might be presumed to have operational responsibilities for implementing institutional strategies. The range and context of the leaders were chosen explicitly to map the range of external drivers described in the previous section. However, any particular leader may face these drivers in varying degrees. Thus it was deemed possible to address the range and significance of the potential drivers through a relatively small number of interviews in the same university, but through the use of a substantial in-depth interviews. The specific organizational contexts included:

Development of organization-wide e-learning delivery and support activities;

Establishment of international branch campus and franchising activity;

Internal reorganization/restructuring to promote interdisciplinary and inter-departmental collaboration;

External engagement and knowledge-exchange activity;

Development of strategic and operational delivery partnering with another UK HEI.

By allowing scope for open-ended interviewing, this approach provided flexibility to explore interpretations and understandings of boundary-spanning and BSL practice, within what might be broadly termed a ‘naturalistic’ approach (Gubrium and Holstein Citation1997). A larger survey approach, while perhaps offering stronger claims for identifying generalizable findings, would by design be based on closed questions, and would have required extensive development and pre-testing work to address potential lack of familiarity with BSL terminology. An appendix to the paper provides details of the questionnaire preamble and semi-structure. Contextual information was collected through common questions about leadership approach, training, barriers and awareness of challenges facing the HE sector. Although subjects were provided with general preamble concerning the salience of BSL, the approach adopted was designed deliberately to avoid a specific steer towards eliciting information about particular practices, and therefore the potential for confirmation bias. In practice this informal approach led to in-depth discussions that revealed detailed information about roles and behaviours, and served to elicit examples of real-life experience. The interview approach provided for flexibility in questioning, with opportunities for question clarification, explanation and deeper probing for relevant data.

In order to control for the potential confounding influence of variation in institutional context and environment, interviews were conducted with subjects all employed at the same HEI, a medium-sized ‘pre-1992’ British university, with a teaching and research mission, and provision at undergraduate and postgraduate levels spread across arts and humanities, social sciences and science subjects. Five interviews were conducted (see ) during the period May 2014 to December 2014, each lasting 45–60 minutes, and were digitally recorded and fully transcribed. As shows, interview subjects were engaged in leadership activity spanning the range of external organizational drivers and self-reported a range of leadership styles, demonstrating a high level of saturation of BSL concepts within the small sample size. Two of the interviewees were female, three male. Transcript analysis was conducted using NVIVO 10 qualitative coding software using descriptive and process coding (Saldaña Citation2013). Descriptive coding was using to categorize respondent identification of boundary types, and process coding to classify respondent use of BSL practices based on the typology above, and sub-coded by tactic and situation, as illustrated in . On many occasions multiple codes were attributed to common sections of narrative.

Table 2. Interview subjects.

Findings

Two main sets of findings are produced from the analysis. The first is information on the prevalence of particular forms of boundaries that the HE leaders identify as prominent. The second is information on the range and extent of the use of particular BSL practices, and the extent to which HE leaders identified opportunities for BSL practices.

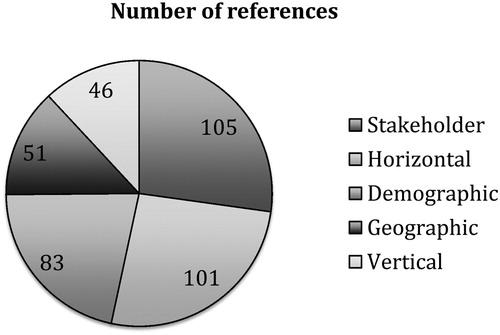

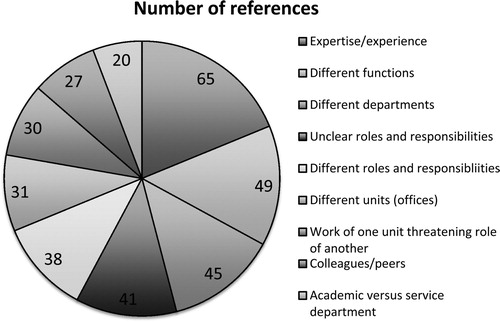

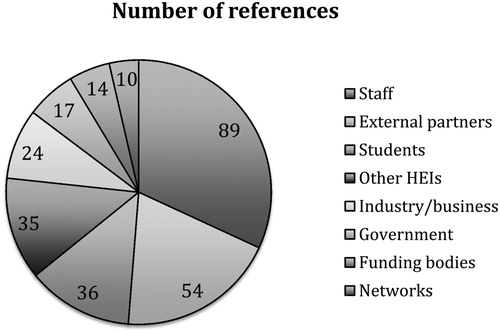

reports summary coding information. The coding analysis suggested that five broad types of boundaries could be identified in the data: demographic, geographic, (internal) horizontal, stakeholder and vertical. Horizontal boundaries (101 instances) and stakeholder boundaries (105 instances) were most commonly referenced by interviewees. On average each interviewee mentioned these boundaries on 20 occasions. Geographic and vertical were less commonly referenced (around 10 occasions per interviewee), suggesting either that these are less commonly encountered or, when encountered, more easily addressed. shows the breakdown of instances of coding of stakeholder boundaries by stakeholder groups. The total of references here is larger than the number reported in because any particular reference to stakeholder boundaries may make mention of two or more different stakeholder groups. The most common stakeholder reference is to other university staff (89 instances). External (non-commercial) partners, such as parents of students, local community interests, media, etc., are also referenced significantly (54 instances). Students, although commonly coded, do not figure as frequently as these first two groups. provides a breakdown of referencing of horizontal boundaries. Here is a more even spread, with cases of boundaries caused by different levels and spread of expertise or experience being most frequently coded (65 instances). Three further horizontal boundaries occurring in at least 40 instances are those caused by difference in function, difference between departments (academic to academic, or service to service), and boundaries arising from lack of clarity about roles and responsibilities. The least frequently coded boundary is that between academic and professional service departments.

Turning now to references to opportunities for the use of particular BSL tactics associated with each practice area, provides a breakdown of the findings. The most commonly coded BSL practice in use is ‘reflecting’. This appears to be in use across all boundary types, but particularly for stakeholder and horizontal boundaries. ‘Mobilizing’ is also a frequently coded practice, with a spread of used across different boundaries. ‘Buffering’, ‘connecting’ and ‘weaving’ are less frequently reported in the data. However, there are a high number of instances of the use of ‘buffering’ across horizontal boundaries. The table reports very few instances of the use of ‘transforming’ as a BSL practice. The final row of data in the table reveals varying evidence for identification of opportunities for BSL skills which are not implemented in practice. The data show unexploited opportunities for ‘reflecting’, ‘mobilizing’ and to a lesser extent ‘weaving’ practices. However, interview transcripts reveal few instances where opportunities for the use of ‘transforming’ and ‘connecting’ practices might have been embraced.

Table 3. Opportunities for use of BSL tactics by boundary type – numbers of references.

Discussion and assessment

The findings here provide abundant evidence that the interviewees perceive significant boundaries constraining their leadership activity, suggesting that contemporary leadership challenges in HE do require extensive engagement across external and internal peer-to-peer boundaries. A large number of instances refer to boundaries between staff or functions within the organization. The boundaries here appear to relate to departmental ‘silos’ (either academic or service), and the challenges of building inter-disciplinary or multi-functional alliances. References to academic to service department boundaries do not appear with particular frequency in the data. Over one-third of references to stakeholder boundaries refer to internal (i.e. other staff or students) boundaries, consistent with findings from other recent research (Floyd and Fung Citation2015).

Whilst we are all working for the same university and in departments that are working in the same broad area, there is definitely a boundary of function. That comes down to ‘you don’t understand what I do’ … we become very focused on our area of expertise and we get the impression that people don’t understand what we do but feel that they have the right to tell us how to do it. (Leader A)

That process of matchmaking groups internally with external partners is a classic example of oil and water not mixing together. There are challenges around staff in the university being ready for those conversations and being ready to communicate what they do to industry … a challenge that is common in a lot of universities. (Leader C)

However, none of the interviewees held executive level appointments in the university concerned, and therefore may have had less cause to engage on a regular basis with government and HE funding agencies. This suggests that, for middle level leaders current HE environmental challenges present themselves more as challenges which require greater internal organizational co-ordination. This raises questions about the appropriateness of traditional hierarchical arrangements for internal university organization, and the importance of effective communication channels for sharing and evaluating knowledge (Carlile Citation2004; Ambrose, Huston, and Norman Citation2005; Bryman Citation2007).

The findings also provide mixed evidence on the extent to which the interviewees describe leadership activity that aligns to CCL-proposed BSL practices (Lee, Magellen Horth, and Ernst Citation2014). These HE leaders appear much better able to identify opportunities for ‘reflecting’ and ‘mobilizing’ practices, in comparison with other practices. ‘Reflecting’ describes leadership practice through which leaders are able to promote respect for difference across boundaries where cross-boundary teams need to be established, in order to facilitate knowledge exchange. This is consistent with recent previous research on the characteristics of successful university heads of department (Kok and McDonald Citation2015), where an ability to reflect knowledge of wider institutional priorities to academic colleagues, is a feature associated with success. These findings appear consistent with previous research on the importance of advocacy as a leadership practice in an HE context (Creswell and Brown Citation1992).

Academic advocates have been really beneficial … they can say ‘look, you know me; I am a respected person in the university; I know what it is like; this is how it worked for me. (Leader A)

It was about bringing the home institution way of doing things to the (overseas university) without being heavy handed and having a kind of imperialist tone of we know better, this is how you do it. Moreover, saying, If you want the profile, brand and reputation of the home institution – have you thought about the consequences of doing things this way. (Leader B)

‘Mobilizing’ ought to presuppose prior trust-building activity through ‘connecting’. However instances of this practice are far fewer. One interpretation of this is that in a knowledge-based organization such as a university trust-building activity is something that academics and other professionals are able to self-initiate without explicit leadership action. This supports previous research findings that collegiality is both an important academic leadership success trait, as well as being highly desired by followers (Ambrose, Huston, and Norman Citation2005).

I have seen people chatting in a corner who probably would not have had anything in common to speak about a few years ago. It’s getting there. (Leader E)

There is more limited evidence for instances of the higher level BSL practices: ‘weaving’ and, in particular, ‘transforming’. This suggests that the HE leaders interviewed were experiencing some difficulties in leading cross-boundary groups into achieving new, common objectives. Leaders appear to articulate fairly high numbers of opportunities for ‘weaving’ to take place. However, the absence of instance of and opportunities for ‘transforming’ practice suggests that within this university long-held group identities make it difficult for groups to implement new agenda for action that require some sacrifice or sharing of identity, and establishment of a new sense of corporate identity and purpose (Barnett Citation2011). It seems reasonable to conclude therefore that the university is predominantly situated at the ‘managing boundaries’ stage of the BSL nexus (). Leaders find the ‘discovering new frontiers’ stage challenging and difficulties here may prevent this university, and potentially others, from addressing more challenging issues in the external environment. Leadership development activity ought therefore to focus on improving self-confidence and ability to identify opportunities and undertake the highest BSL practices.

As stated above, the selection of interviewees from the same institution has the advantage of holding institutional context, and any variation in the impact of the different drivers of change, constant across the interview data. However, that context may vary significantly from university to university, depending on a range of other contextual factors such as the complexity of subject mix and specialization, geographical location (not least because student fee regimes vary across the devolved administrations within the UK), and overall institutional mission and strategy. HEIs in the UK are self-organized into a range of different ‘mission groups’ and are exposed in varying degrees to particular external challenges (Barnett Citation2011). They may also be at different stages and intensity of strategic change in response to these. Qualitative data coding has attempted to provide distinct demarcations of boundary typology and BSL practice. This reveals that boundaries do not exist in isolation; several boundary codes were assigned to the same sections of narrative. This suggests a need to form a deeper understanding of the relationship between boundaries and how they are formed in the HE context, before any attempt to be prescriptive about leadership practice.

Significant further research, beyond the scope of the present paper, will need to address the question of generalizability, and in particular how the emphasis and extent of BSL practice might vary by university type. This is in the context of how different universities with different missions frame the role of leadership in their particular strategic response to the challenges outlined earlier. In the present study interviewees had not typically employed BSL skills as an explicit leadership approach. A significant proportion of their understanding of boundary spanning appears to be latent or tacit. It was therefore sometimes difficult to distinguish precisely between particular BSL practices and tactics within the narratives. Further consideration of these issues would require more detailed analysis at the level of the individual leader.

Conclusion

The findings in the paper point to the significance and scale of boundaries of a range of forms acting on HE leaders, and the varying degrees to which they are able to deploy practices to support boundary-spanning work. Those who write on BSL practice tend to do so from a deliberately prescriptive or practice-based perspective. This intention of this study has been to some extent descriptive rather than prescriptive in terms of policy or practice. Further careful research, with both a deeper and wider reach, would be needed in order to draw sharper conclusions about how HE leaders ought to change leadership practice. It has been previously noted that HE leaders, particular academic ones, are appointed on the basis of current and expected future specialist expertise rather than leadership skill or potential (Bryman Citation2007; Fielden Citation2009). To this extent, the findings here highlight the general importance of leadership development designed around the challenges of boundary spanning, as much as around ‘within team’ leadership, coaching and mentoring skills. This also points to the importance of allowing leaders to identify and articulate latent and tacit knowledge and experience about organizational boundaries and about boundary-spanning behaviour.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. This is most pronounced in England. In the other devolved nations of the UK the extent to which fee income comes via public support for students to pay fees varies. However, current public funding pressures suggest that the current status quo is unlikely to be sustained over the medium term, with pressure to raise fee levels in some, if not in all universities and subject areas, and reduce public ‘subsidy’ where it still remains.

2. In the UK the principal regulatory body, the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education, maintains a comprehensive regulatory code and enforces compliance through periodic reviews of individual institutions. Its role and the residual student focused responsibilities of the Higher Education Funding Councils are due to be replaced by a new Office for Students. Research has for 30 years been assessed in the UK HEIs using periodic peer-reviewed Research Assessment Exercises (since 2014 renamed Research Excellence Framework). A further agency currently regulates access to higher education and monitors HEI performance against social inclusion targets.

References

- Ambrose, S., T. Huston, and M. Norman. 2005. “A Qualitative Method for Assessing Faculty Satisfaction.” Research in Higher Education 46 (7): 803–30. doi: 10.1007/s11162-004-6226-6

- Barnett, R. 2011. Being a University. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Bolden, R., J. Gosling, A. O’Brien, K. Peters, M.K. Ryan, S.A. Haslam, and K. Winklemann. 2012. Academic Leadership: Changing Conceptions, Identities and Experiences in UK Higher Education. London: Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.

- Brewer, J. D. 2013. The Public Value of the Social Sciences: An Interpretative Essay. London: Bloomsbury.

- Brown, R., and H. Carasso. 2013. Everything for Sale? The Marketisation of UK Higher Education. London: Routledge.

- Bryman, A. 2007. “Effective Leadership in Higher Education: A Literature Review.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (6): 693–710. doi: 10.1080/03075070701685114

- Bryman, A. 2009. Effective Leadership in Higher Education. London: Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.

- Bryman, A. 2015. Social Research Methods. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Burkhardt, J.C. 2002. “Boundary Spanning Leadership in Higher Education.” Journal of Leadership and Organizational Studies 8 (2): 145–50. doi: 10.1177/107179190200800312

- Carlile, P. 2002. “A Pragmatic View of Knowledge and Boundaries: Boundary Objects in new Product Development.” Organization Science 13 (4): 442–55. doi: 10.1287/orsc.13.4.442.2953

- Carlile, P. 2004. “Transferring, Translating and Transforming: an Integrative Approach for Managing Knowledge across Boundaries.” Organization Science 15 (5): 555–68. doi: 10.1287/orsc.1040.0094

- Christensen, C.M., and H.J. Eyring. 2011. The Innovative University: Changing the DNA of Higher Education From the Inside Out. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Clarke, B.R. 2004. “Delineating the Character of the Entrepreneurial University.” Higher Education Policy 17 (4): 355–70. doi: 10.1057/palgrave.hep.8300062

- Corwin, R., and T. Wagenaar. 1976. “Boundary Interaction between Service Organizations and Their Publics: A Study in Teacher–Parent Relationships.” Social Forces 55 (2): 471–92. doi: 10.1093/sf/55.2.471

- Creswell, J., and M.L. Brown. 1992. “How Chairpersons Enhance Faculty Research: A Grounded Theory Study.” Review of Higher Education 16 (1): 41–62. doi: 10.1353/rhe.1992.0002

- Cross, R., C. Ernst, and B. Pasmore. 2013. “A Bridge Too Far? How Boundary Spanning Networks Drive Organizational Change and Effectiveness.” Organizational Dynamics 42 (2): 81–91. doi: 10.1016/j.orgdyn.2013.03.001

- Ernst, C., and D. Chrobot-Mason. 2011. “Flat World, Hard Boundaries – How to Lead across Them.” MIT Sloan Management Review 52 (3): 81–88.

- Ernst, C., and J. Yip. 2009. “Boundary Spanning Leadership: Tactics to Bridge Social Identity Groups in Organizations.” In Crossing the Divide: Intergroup Leadership in a World of Difference, edited by T. L. Pittinsky, 89–99. Boston, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Faraj, S., and A. Yan. 2009. “Boundary Work in Knowledge Teams.” Journal of Applied Psychology 94 (3): 604–17. doi: 10.1037/a0014367

- Fielden, J. 2009. Mapping Leadership Development in Higher Education: A Global Study. London: Research and Development Series, Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.

- Floyd, A., and D. Fung. 2015. “Focusing the Kaleidoscope: Exploring Distributed Leadership in an English University.” Studies in Higher Education (in press) doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1110692.

- Gibb, A., G. Haskins, P. Hannon, and I. Robertson. 2012. Leading the Entrepreneurial University. London: National Centre for Entrepreneurship in Education. Accessed 27 March 2017. http://ncee.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/leading_the_entrepreneurial_university.pdf.

- Gosling, J.R., R. Bolden, and G. Petrov. 2009. “Distributed Leadership in Higher Education: What Does it Accomplish?” Leadership 5 (3): 299–310. doi: 10.1177/1742715009337762

- Gubrium, J. F., and J. A. Holstein. 1997. The New Language of Qualitative Method. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Jones, P., and J. Lewis. 1991. “Implementing a Strategy for Collective Change in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 16 (1): 51–61. doi: 10.1080/03075079112331383091

- Kelly, U., I. McNicoll, and J. White. 2014. The Impact of Universities on the UK Economy. London: Universities UK. Accessed 27 March 2017. http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/economic-impact-higher-education-institutions-in-england.aspx.

- Kennie, T. 2010. Academic Leadership: Dimensions, Dysfunctions and Dynamics. London: Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.

- Kirkwood, A., and L. Price. 2005. “Learners and Learning in the 21st Century: What So We Know and Students’ Attitudes towards and Experiences of Information and Communication Technologies That Will Help us Design Courses?” Studies in Higher Education 30 (3): 257–74. doi: 10.1080/03075070500095689

- Knight, W.H., and M.C. Holen. 1985. “Leadership and the Perceived Effectiveness of Department Chairpersons.” Journal of Higher Education 56 (6): 677–90. doi: 10.2307/1981074

- Kok, S.K., and C. McDonald. 2015. “Underpinning Excellence in Higher Education – An Investigation into the Leadership, Governance and Management Behaviours of High-Performing Academic Departments.” Studies in Higher Education (in press) doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1036849.

- Labib, A., M. Read, C. Gladstone-Millar, R. Tonge, and D. Smith. 2014. “Formulation of Higher Education Institutional Strategy Using Operational Research Approaches.” Studies in Higher Education 39 (5): 885–904. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2012.754868

- Lee, L., D. Magellen Horth, and C. Ernst. 2014. Boundary Spanning in Action – Tactics for Transforming Today’s Borders Into Tomorrow’s Frontiers. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

- Leifer, R., and A. Delbecq. 1978. “Organizational/Environmental Interchange: A Model of Boundary Spanning Activity.” The Academy of Management Review 3 (1): 40–50. doi: 10.5465/amr.1978.4296354

- Lowendahl, J.-M. 2013. The Gartner Higher Education Business Model Scenarios: Digitalization Drives Disruptive Innovation and Changes in the Balance. Stamford, CT: Gartner.

- Lumby, J. 2012. What Do We Know about Leadership In Higher Education? The Leadership Foundation for Higher Education’s Research: Review Paper. London: Leadership Foundation for Higher Education.

- Lynch, R., and P. Baines. 2004. “Strategy Development in UK Higher Education: Towards Resource-Based Competitive Advantages.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 26 (2): 171–87. doi: 10.1080/1360080042000218249

- McCaffrey, P. 2010. The Higher Education Manager’s Handbook. 2nd ed. New York: Routledge.

- McGuire, J.B., C.J. Palus, W. Pasmore, and G.B. Rhodes. 2009. Transforming Your Organization. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

- Miller, P.M. 2008. “Examining the Work of Boundary Spanning Leadership in Community Contexts.” International Journal of Leadership in Education: Theory and Practice 11 (4): 353–77. doi: 10.1080/13603120802317875

- Neumann, Y., and E.F. Neumann. 1999. “The President and the College Bottom Line: the Role of Strategic Leadership Styles.” International Journal of Educational Management 13 (9): 73–79.

- Newton, J. 2003. “Implementing an Institution-wide Learning and Teaching Strategy: Lessons in Managing Change.” Studies in Higher Education 28 (4): 427–441.

- Ollsen, M., and M.A. Peters. 2005. “Neoliberalism, Higher Education and the Knowledge Economy: From the Free Market to Knowledge Capitalism.” Journal of Education Policy 20 (3): 313–45. doi: 10.1080/02680930500108718

- PA Consulting. 2008. Keeping Our Universities Special. London: PA Consulting. Accessed 25 April 2016. http://hedbib.iau-aiu.net/pdf/PAConsulting_KeepingUniv_Special.pdf.

- Parrish, D.R. 2015. “The Relevance of Emotional Intelligence for Leadership in a Higher Education Context.” Studies in Higher Education. 40 (5): 821–37. doi: 10.1080/03075079.2013.842225

- Parry, K.W. 1998. “Grounded Theory and Social Process: A New Direction for Leadership Research.” Leadership Quarterly 9 (1): 85–105. doi: 10.1016/S1048-9843(98)90043-1

- Peach, D., C. Cates, J. Jones, H. Lechleiter, and B. Ilg. 2011. “Responding to Rapid Change in Higher Education: Enabling University Departments Responsible for Work-Related Programs Through Boundary Spanning.” Journal of Cooperative Education and Internships 45 (1): 94–106.

- Pounder, J.S. 2001. “New Leadership and University Organizational Effectiveness: Exploring the Relationship.” Leadership and Organization Development Journal 22 (6): 281–90. doi: 10.1108/EUM0000000005827

- Ramsden, P. 1998. “Managing the Effective University.” Higher Education Research and Development 17 (3): 347–70. doi: 10.1080/0729436980170307

- Rantz, R. 2002. “Leading Urban Institutions of Higher Education in the new Millennium.” Leadership and Organization Development Journal 23 (8): 456–66. doi: 10.1108/01437730210449348

- Saldaña, J. 2013. The Coding Manual for Qualitative Researchers. 2nd ed. London: Sage.

- Seale, O., and M. Cross. 2015. “Leading and Managing in Complexity: The Case of South African Deans.” Studies in Higher Education (in press) doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.988705.

- Shattock, M. 2009. Entrepreneurialism in Universities and the Knowledge Economy: Diversification and Organizational Change in European Higher Education. Maidenhead: McGraw Hill/Open University Press.

- Stark, J.S., C.L. Briggs, and J. Rowland-Poplawski. 2002. “Curriculum Leadership Roles of Chairpersons in Continuously Planning Departments.” Research in Higher Education 43 (3): 329–356.

- Thorp, H., and B. Goldstein. 2010. Engines of Innovation - The Entrepreneurial University in the 21st Century. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Universities UK. 2015. Quality, Equity, Sustainability: The Future of Higher Education Regulation. London: Universities UK. Accessed 27 March 2017. http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Pages/quality-equity-sustainability-future-of-he-regulation.aspx.

- Weerts, D.J., and L.R. Sandmann. 2010. “Community Engagement and Boundary Spanning Roles at Research Universities.” The Journal of Higher Education 81 (6): 702–27. doi: 10.1080/00221546.2010.11779075

- Yip, J., C. Ernst, and M. Campbell. 2016. Boundary Spanning Leadership: Mission Critical Perspectives From the Executive Suite. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

- Yip, J., S. Wong, and C. Ernst. 2008. “The Nexus Effect – When Leaders Span Group Boundaries.” Leadership in Action 28 (4): 13–17. doi: 10.1002/lia.1256

- Yuan, L., and S. Powell. 2013. MOOCs and Open Education: Implications for Higher Education. Bolton: Centre for Educational Technology and Interoperability Standards. Accessed 27 March 2017. http://publications.cetis.ac.uk/2013/667.

Appendix: Interview preamble and structure

Introduction

From a comprehensive study of leadership theory and the rapid changes affecting the HE sector, we have concluded that there is a distinct need for HEIs to adopt the culture of learning organisations, necessitating a shift in mind-set towards the development of an open, cross-functional organisation with a global outlook (Yip et al. 2011).

For universities, greater collaboration between functions and solidarity of purpose is the only way to ensure the delivery of high quality teaching and research that would attract the required level of funds (Bolden et al. Citation2012). There is also increasing pressure for the HE sector to solve complex, global issues by working in multi-disciplinary teams made up of internal and external participants (Thorp and Goldstein Citation2010).

This is a profound shift from the traditional formal and bureaucratic structures prevalent in many HEIs and presents a major leadership challenge on both an institutional and individual basis (Faraj and Yan Citation2009). Groups of people, who historically worked apart due to a variety of boundaries, are increasingly finding themselves working together. The principles and practices of Boundary Spanning Leadership present an opportunity to overcome some of these challenges.

The Boundary Spanning approach is aimed at developing, ‘the ability to create direction, alignment and commitment across boundaries in service of a higher vision or goal’ (Ernst and Chrobot-Mason Citation2011, 5). By drawing on diverse expertise and cultural insights, cross-functional collaboration can achieve breakthrough results, innovation and change that single groups could not do on their own (Yip et al. Citation2016). By effectively directing and aligning all involved, spanning boundaries can lead to the ‘Nexus Effect’ – the point at which collaboration enables groups realise transformational outcomes that they could never achieve on their own.

The purpose of these interviews is to identify:

Your unique challenge – a challenge that can only be solved by leading effectively across boundaries

The most appropriate boundary spanning practice to apply to this specific challenge

Tactics that could be developed and applied to the challenge

Main questions

How would you describe your approach to leadership?

With these definitions in mind what are the three to five most pressing leadership challenges you currently face? [Something that is critical to driving individual and organisational success]

As HEIs change their outlook and priorities, the top down managerial approach is often perceived as micro-managing and eroding academic freedom and collegiality? Do you agree with this? Do you think it is important to maintain academic autonomy?

Do you think academics have a tendency to resist being managed?

Do you think that colleagues are aware of the changes? Do you think the implications are taken seriously? Do you think they understand the need for change? What are the effects of not understanding/acknowledging the need for change?

The professionalization of services has also been a major shift in the running of Institutions and is a fundamental source of competitive advantage for many. How do you see professionals and academics working together?

As the government’s modernisation agenda steers universities towards entrepreneurial and corporate models, the focus on commercially-orientated values risks disengaging staff. Do you think the customer-driven, student experience is affecting the academic work?

Generally speaking, governance structures are conservative and do not lend themselves to the challenges of a fast-moving competitive environment, where risk and quick decisions are paramount. How do you think this can be changed (if at all)? Have you any examples of where this has hindered an initiative?

What is your experience of silo’s in HEIS? How do you think this mentality can be changed?

What are the most profound boundaries in HE? What is your experience? How can they be broken down?

Follow-up questions (asked on a case by case basis)

Changing nature and context

What has been your experience of resistance to change? What has been your experience of embracing change?

How do you think senior leaders can best communicate clear direction and engender commitment?

Do you think there are greater demands on academic staff? Is this affecting their academic work?

Do you think colleagues have a clear understanding of their roles, responsibilities and objectives? How could this be improved?

How do you think change can be viewed as a force that requires a response rather than a disruption?

Do you think academics are learning to establish collaborative relationships with students? Instead of the student being the apprentice, the student is now the learning partner?

Do you think that the typical institution promotes career paths that reward individual over collective achievement?

Collaborative projects

Collaborating across boundaries is of extreme importance, yet the shift towards a global and open mind-set is a tough leadership challenge.

How can diversity across subject areas, departments, external relationships be leveraged? How can be bring diverse people together and develop mutual respect?

How do you lead in situations that require collaboration?

How to aim to gain commitment and engagement?

How do you communicate the vision?

How do you nurture internal support?

How do you handle situations where there is resentment about the funding, time and attention required for these projects?

How do you Identify project champions? Who are they? Why are they different?

Many projects now require the involvement and commitment of a wide range of staff working across organisational boundaries – what is your experience of this?

In collaborative activity, leaders must have highly developed interpersonal skills and an ability to nurture connections. Do you agree? Do you think these skills can be learned? 63

External partners

How have you handled differences in bureaucracy/processes when working on projects with external partners?

How have you developed relationships with overseas partners? What were the challenges?

Have you experienced cultural differences? How did you overcome them?

How have you maintained quality outside of the campus?

How have you developed ownership of the home brand?