ABSTRACT

The purpose of this study is to outline a new approach to the comparative analysis of student finance systems based on social rights, an approach widely applied in other areas of social policy. It focuses on rights codified in national legislation and financed by central governments, and the collection of indicators measuring formal eligibility and entitlements using model family analyses techniques. We illustrate the usefulness of the approach by exploring the relationship between the generosity and the degree of low-income targeting of student support in 21 OECD countries. The results show that student support is less generous in countries that concentrate benefits on students from low-income families.

1. Introduction

Interest in the comparative analysis of educational systems has grown in recent years (Pfeffer Citation2015; Garritzmann Citation2017), largely due to greater availability of cross-national data on student performance at the compulsory and upper secondary levels. Tertiary education has received less scholarly attention, despite a general interest in increasing participation in higher education, and improving learning.

The purpose of this study is to present a novel approach to the comparative analysis of student finance in higher educational systems. The approach focuses on social rights codified in national legislation and financed by the state, and the development of indicators measuring formal eligibility and entitlements. Using new and unique institutional data from 21 OECD countries in the year 2010, it is an original attempt to compare jointly the level of student support (including loans, grants, and family support arrangements) and tuition fees as expressed in legal frameworks and regulations.

Cost-sharing arrangements in higher education are becoming a central policy issue as there is a growing concern about youth poverty and student indebtedness (Barr et al. Citation2018). The extent to which the state, families or students should be responsible for covering study costs is particularly debated (Johnstone et al. Citation2006; Orr, Wespel, and Usher Citation2014). Public measures targeting study costs are often subsumed under the label of student support, and typically include a combination of (1) direct repayable support, (2) direct non-repayable support as well as (3) indirect support. Examples of the first category are student loans, of the second need- and/or merit-based grants, and of the third tax allowances and tax credits provided to the student’s parents as well as any extensions of family allowances in the case of children continuing into tertiary education. Student support is sometimes means- or income-tested, thus targeting students from low-income families, but flat-rate universal provisions do also exist. Adding (4) tuition fees to the discussion yields an analysis of student finance, or if considered with financial aid in a joint measure – net student support.Footnote1

The distinction between the three different types of support captures the core dimension of cost-sharing. First, while non-repayable support implies that the state takes responsibility for partly covering study costs, repayable support assumes responsibility to be shared between the state (as most student loans are subsidized) and students through their future income streams (from employment in case of income-contingent loans). Second, indirect support reflects the willingness of the state to support families in covering the study costs.

The amount and the structure of economic support provided to students in higher education are important for many reasons, including how countries can organize their student finance systems to better respond to the needs of students from low-income households. Student finance policy can thus influence both enrolment rates and study outcomes (Dynarski and Scott-Clayton Citation2013, Marcucci Citation2013), where the latter issue is linked to students’ involvement in paid work. Studying combined with employment is in itself not negative, but can be detrimental for study outcomes if excessive (Baert et al. Citation2018). Thus, providing adequate financial incentives to students from disadvantaged social backgrounds can have a positive impact not only on equity (by providing equal chances for higher education and breaking the link to family status) but also on efficiency (by providing better opportunities for learning). Examining different cost-sharing arrangements and their implications for inequality is therefore of paramount interest.

To illustrate the usefulness of our approach in addressing new questions in relation to student finance, we structure the paper around the so-called paradox of redistribution stating that there may be a negative relationship between the degree of low-income targeting and the generosity of the welfare system (Korpi and Palme Citation1998). Applied to student finance, we should thus expect a negative relationship between the skewness of net student support towards low-income families (targeting) and the size of net student support in relation to family income (generosity). The basic idea of a paradox of redistribution is linked to various discussions in political economy, and the ways in which the welfare state encourages (or discourages) broader popular support for redistributive policies that cuts across social class.

The second section of the paper reviews the literature and adapts a political economy perspective on student finance in higher education. In Section 3, we discuss different types of social policy data, and in Section 4, we devote extensive space to the description of our data and principles behind the collection and operationalization of our indicators. Notably, this is the first time social rights indicators on the generosity and low-income targeting of student support are used in comparative research. The fifth section presents the results, which are discussed in the last section. Here, we also indicate the limitations of our data and suggest avenues for future research.

2. Student social rights in comparative perspective

Despite higher education being increasingly recognized as an important component of equitable and sustainable societies (Morel, Palier, and Palme Citation2012; Willemse and de Beer Citation2012), student support and tuition fees have been largely absent in the comparative welfare state literature. Few studies have thus explicitly analysed, not to mention explained, cross-country differences in cost-sharing arrangements.Footnote2 This includes their potential political economy determinants. Although Johnstone (Citation2004) and Johnstone and Marcucci (Citation2010) analysed changes in student finance, in terms of drivers of change their focus was mostly on structural factors, such as fiscal austerity and cohort size. Hence, the role of interest formation and how student finance may help to strengthen cross-class alliances in favour of an expansion of the welfare state were not discussed.

The dominance of structural perspectives in analyses on student finance is now slowly changing in favour of key aspects of the political economy (Garritzmann, Citation2016; Ansell Citation2010; Garritzmann Citation2017), which for long inspired sociological studies on welfare states, redistribution, and social inequality (Korpi Citation1989; Esping-Andersen, Citation1990). The starting point for these early large-scale comparative analyses on the welfare state was the concept of social citizenship introduced by Marshall (Citation1950), and the distinction between civil rights (e.g. freedom of speech), political rights (e.g. universal suffrage) and social rights. In Marshall’s iconic definition of social rights, they encompass a

whole range from the right to a modicum of economic welfare and security to the right to share to the full in the social heritage and to live the life of a civilized being according to the standards prevailing in the society. (11)

According to Marshall, social rights were intimately linked to the educational system. He writes:

The right to education is a genuine social right of citizenship, because the aim of education during childhood is to shape the future adult. Fundamentally it should be regarded, not as the right of the child to go to school, but as the right of the adult citizen to have been educated. (25)

But not any education would do; elementary schooling, for instance, ‘increased the value of the worker without educating him above his station’ (35). Free public elementary education was, therefore, an incomplete move towards the establishment of social citizenship. Further expansion would be required – an expansion that not necessarily had to imply free higher education. For Marshall, fees were acceptable as long as there was some compensatory mechanism alleviating the inequality consequences of the fees – and an example were state scholarships to university education.Footnote3

Against this background, it may seem slightly surprising that social policy analyses in the tradition of Marshall have paid relatively little attention to education in general, and student finance in particular. Social rights have in practice often been operationalized by social insurance programmes, as these are believed to guarantee citizens ‘a modicum of economic welfare and security’ at different stages of the life course (e.g. Korpi Citation1989, Ferrarini et al. Citation2013). The extent to which individual differences in the risk of economic loss are expressed in class-based politics is consequently seen as a fundamental factor in explaining the emergence and continued development of welfare states.

Our cross-sectional data makes it difficult to examine the political determinants of student finance in closer detail and to explore how interest formation and class-based politics is causally linked to student finance. Our ambition is rather to explore how analytical perspectives in the comparative welfare state literature may facilitate tackling new questions in student finance research. Such new questions relate to the joint effect of fees and support (here labelled net student support) on students’ financial situation. Another is how to best maximize net student support to students from low-income households, who, partly due to financial difficulties, have lower probability of enrolment (Dearden, Fitzsimons, and Wyness Citation2014) and higher risks of dropout (Agasisti and Murtinu Citation2016).Footnote4

Both issues relate to a wider discussion in the comparative welfare state literature on a paradox of redistribution. Following the seminal study of redistribution and income inequality by Korpi and Palme (Citation1998), it was long assumed that an increased low-income targeting of state budgets is harmful for low-income households. The reason is simply that low-income targeting will receive less support among the politically powerful middle-classes, who may obstruct tax increases to finance programmes that exclude the non-poor. Without middle-class support, governments will thus have difficulties establishing generous transfer programmes that actually can lift people out of poverty.

While there are indications that the political economy of redistribution has become increasingly complex (Brady and Bostic Citation2015) and the link between low-income targeting and redistribution may have weakened (Kenworthy Citation2011; Marx and Nelson Citation2013; Marx, Salanauskaite, and Verbist Citation2016), the political economy of student finance needs further analysis. Although data limitations prevent us from conducting a proper test of the paradox, the analyses below nonetheless show the fruitfulness of our analytical approach.

3. Student finance policy data for comparative analysis

A main field of discussion in comparative welfare state research concerns the conceptualization and measurement of social policy (Clasen and Siegel Citation2007), and parts of this discussion have clear implication also for the comparative analysis of student finance. Expenditures are probably the most utilized source of information on social policy, and it is a common source of data also in educational research (Willemse and de Beer Citation2012). Its use, however, is often based more on convenience than on theoretical reasoning. Being relatively easy to operationalize on the basis of data from the national accounts, indicators based on social expenditures are illustrative measures of how policy intentions translate into real costs. However, they are only rough proxies of policy design, as expenditures depend also on factors unrelated to the ways in which policy is defined in legal frameworks. For example, unemployment benefit expenditures typically increase in economic downturns when unemployment rates go up, even if policy remains the same. As the number of pensioners increase, so does old-age benefit expenditure, and so forth.

It is reasonable to expect that expenditure data on student finance are also heavily affected by such changes in welfare needs. Both the size and composition of the study-age population changes over time, as do the demand for tertiary qualifications in society. These factors are likely to affect expenditures on student finance, albeit the policies as such remain the same. To account for such extrinsic processes, social expenditures are often expressed per capita in relevant target populations, a strategy that is common also in analyses of educational policy (Heller and Callender Citation2013; Ertl and Dupuy Citation2014; Garritzmann Citation2016). Although per capita spending provides important new information, we still only have a vague idea about the actual design of policies and how generous various types of benefit programmes are. Only in a few exceptional cases (i.e. a universal flat-rate benefit) is it reasonable to assume that each person in the target population receives an equal share of the expenditure. Also, the distribution of public student funding between the different budget items is often obscured in public expenditure data.

Case-load statistics are a second type of data used in comparative social policy research. Indicators of this type show the number of citizens (or any target population for that matter) who are recipients of a public transfer. Although data on recipients come closer to policy intentions and the reality experienced by individuals (Van Oorschot Citation2013), lack of comparative data is an ongoing problem for research. Although the establishment of comparative socio-economic datasets such as the European Union Statistics on Income and Living Conditions (EU-SILC) and the Luxembourg Income Study (LIS) have improved our possibilities of analysing recipients of various types of benefits, and users of core public services, data usage is often plagued with difficulties.

One problem is inconsistencies in administrative categories between countries and years. In areas of social policy, there is often an incomplete separation of contributory or non-contributory (tax-financed) benefits (De Deken and Clasen Citation2013). Also for student finance, the separation between different types of financial instruments is often muddled. EU-SILC collapses all education-related programmes into one single income category, and the LIS variable template does not distinguish between student support and other types of benefits and transfers. None of the databases contain any data on student loans.

Social rights data were originally introduced in welfare state research to overcome the problems of making policy inference based on expenditure data (Korpi Citation1989). Its use in research is closely connected to Marshall’s (Citation1950) ideas of social citizenship as being manifested in de jure rights. Focus is thus on legal frameworks, out of which relevant indicators are extracted based on formal eligibility (access for whom) and entitlements (access to what). Compared to social expenditures, data on the institutional structures of social policy more accurately capture the role and intentions of the state in providing welfare to its citizens, something that we believe is of relevance in analyses of student finance policies. Moreover, without legal frameworks establishing social rights, there would be no beneficiaries and hence no expenditures.

4. Measuring social rights of students

We have collected new, social rights data on student finance in 21 OECD countries: Australia, Austria, Canada, the Czech Republic, Denmark, England, Estonia, Finland, France, Germany, Iceland, Ireland, the Netherlands, New Zealand, Norway, Poland, Portugal, Slovakia, Slovenia, Spain and Sweden.Footnote5 We aimed for an adequate coverage of each standard welfare state regime as well as of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE), while also taking data accessibility and quality into consideration. It should be emphasized that the dataset used in the analyses below is of an interim character and that collection (both with regard to countries and time points) will continue.

The data has been collected based on model family analyses techniques, which is a powerful method of rendering indicators comparable across countries and over time (Bradshaw et al. Citation1993). The model family consisted of two parents, both 50 years of age and legally married, and two children aged 16 and 20.Footnote6 None of the family members belong to any ethnic minority group, or have any mental or physical disabilities.Footnote7 The 20-year-old child is assumed to be a full-time undergraduate student at a public university, studying first, second or third year (each year has been coded separately and then an average has been used), having no work income, living away from the family home, and less than 10 km from an academic campus. The model families have no financial assets, and they differ only in terms of family income. The very low-income case is a male breadwinner model family relying on a single wage corresponding to 50 per cent of the wage of an average production worker (APWW).Footnote8 The low-income case is also a male breadwinner model family, but here, we assume a wage level equal to 100 per cent of an APWW. The middle-income case is a dual-earner family, where both spouses have a wage level of 100 per cent of an APWW.Footnote9 All incomes are measured after tax and social security contributions.

We use two variables calculated from our data: generosity and degree of targeting of net student support (i.e. after tuition fees). The generosity of net student support is simply the sum of entitlements to repayable, non-repayable, and indirect student support less tuition fees, expressed as percentage of the net APWW of our three different model families.

The degree of targeting shows the extent to which the generosity of net student support varies across our model families. It is calculated using the concentration coefficient when model families are ranked starting from very low disposable income (Kakwani Citation1986). To improve interpretations of our results, the degree of targeting is measured by multiplying the concentration coefficient of net student support by a factor of −1.0. The degree of targeting may vary between values of −1 and + 1. The higher the value, the more net student support concentrates among the model families having lower incomes. Values close to zero suggest that the generosity of net student support is similar across the model families, despite their different income levels.

In model family analyses of this kind, there is always a potential trade-off between representativeness and cross-country comparability as entitlements and tuition fees are calculated for model families that not necessarily capture the whole target population. However, the key characteristics of the model families are in most countries typical for the student populations – at least in Europe as evidenced in Eurostudent reports (Hauschildt et al. Citation2015) – while being diverse enough for us to isolate some of the effects of family income on net student support.

We calculated the size of available student support and tuition fees as expressed in legal frameworks in the academic year 2010/2011. In countries where student support and tuition fees differ between academic disciplines, we used the average of sociology, engineering and medicine. For countries showing regional or inter-university differences in student support and tuition fees, we used information from all the universities in the capital. Similar procedures in coding principles are extensively used in research on social assistance, which in some countries show regional or even local variation (Nelson and Fritzell Citation2014).

We included only student support that is established as a social right in national legislation and financed by the state (i.e. entitlements to grants and loans that are legally guaranteed for every student fulfilling eligibility criteria, and entitlements to indirect support for the families of students). Thus, we disregarded benefits that are typically competitive and only available to a few, which is the case of most merit-based scholarships or student housing (Hauschildt et al. Citation2015). Moreover, merit-based grants often depend on discretionary decisions by universities. Neither do we include other in-kind benefits like those for food or transport, which are often set on a local, or university, level. Benefits (in cash or in-kind) that are not conditioned on student enrolment (i.e. child benefits or housing allowances) are excluded from the analysis.

Our treatment of student loans as social rights deserves special attention. One can claim that expecting students to pay back disqualifies loans as rights – especially since we know that loans and grants may have different impacts on students’ behaviour, not least those from unprivileged backgrounds (Dynarski and Scott-Clayton Citation2013). However, we are interested primarily in the way that student finance policy enables education by guaranteeing students’ incomes at present, preventing poverty and facilitating family independence, and focusing on studies instead of work. It should be emphasized that in the vast majority of cases, student loans are state-subsidized and organized at the national level to better enable consumption smoothing and provide adequate responses to possible market failures (Barr et al. Citation2018). Even students from middle-income families can be supported in deferring part of their study cost to the after-study period, hence reducing their ongoing reliance on family support or incomes from work. This would typically not be possible without state intervention establishing a social right to student loans.

In some, mostly European, countries higher education is free of tuition or associated with very low costs of entry. In other countries, tuition fees can impose a significant financial burden on students and their families. There might also exist a correspondence between tuition fees and the support system in place (e.g. the payment is deferred to the post-study period through a loan mechanism). Thus, we analyse student support net of tuition fees. We only consider tuition fees of public universities, and we do not include other fees (enrolment or administrative fees, etc.) since they are typically very low, and used as a way of financing in-kind benefits (e.g. student union fees). Sometimes, such fees are not even mandatory.

5. Results

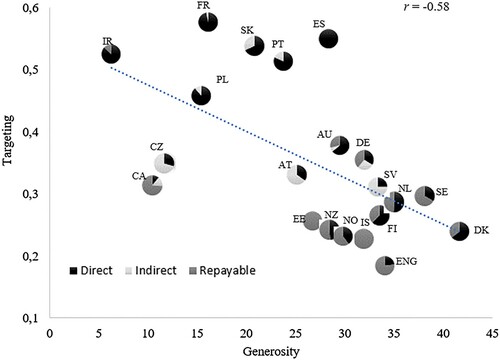

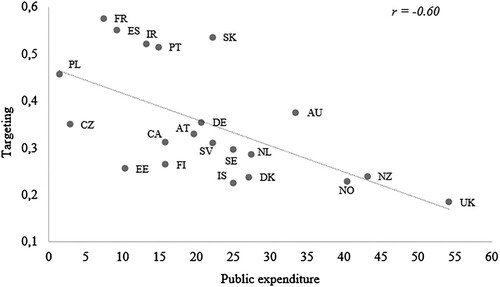

To investigate the relationship between the degree of targeting and generosity of net student support, we rely on simple scatterplots. shows the association between the degree of targeting and generosity of net student support (as an average of our three model families) in 21 countries. There is indeed a moderate negative association between the degree of targeting and generosity (correlation coefficient of −0.58). Thus, students from low-income families tend to receive more generous support in countries that supposedly avoid an exclusive targeting of policies. No country has a negative concentration coefficient of net student support, or a perfectly equal system, not even the Nordic countries that rely heavily on universal flat-rate benefits.Footnote10

Figure 1. Degree of targeting and generosity of net student support as an average of three model families and share of direct, indirect, and repayable support in 21 OECD countries, 2010.

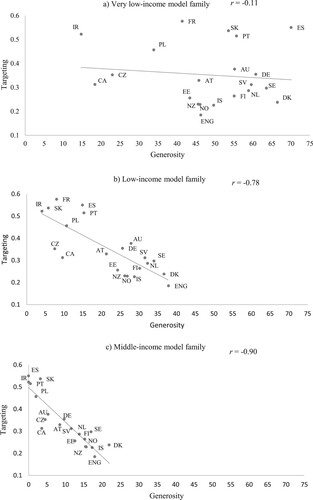

To further explore the association between targeting and generosity of net student support, (a–c) shows results for the three model families separately (very low, low, and middle income). Notably, although there is substantial difference in the variation of generosity across the model families, the negative association is observed for each model family irrespective of their different income levels. This brings further descriptive evidence to the counter-intuitive idea that an exclusive focus on low-income targeted benefits in student support may be to the disadvantage of students from poorer backgrounds. However, it is evident that a large part of the association between targeting and generosity of net student support above is driven by patterns observed among our two model families having the highest incomes (low- and middle-income model families). The correlation coefficient is −0.91 for the middle-income model family, somewhat lower for the low-income model family (−0.71), and as low as −0.11 (but still negative) for the very low-income model family.

Figure 2. (a–c) Degree of targeting and generosity of net student support for three model families in 21 OECD countries, 2010.

To better understand why countries have different levels of student support, the pie charts in above are illustrative. They show the share of direct and indirect benefits, as well as repayable loans in the student support package. First, none of the countries in the lower right corner (except Slovenia and possibly Germany) rely heavily on indirect support (tax benefits and allowances for families). Indirect support is more common among countries with less egalitarian distributive profiles. Thus, in line with the arguments put forth by Chevalier (Citation2018), countries that embrace the idea of youth citizenship by providing more direct support to students rather than benefits for their families, also tend to have a more generous system of student support.

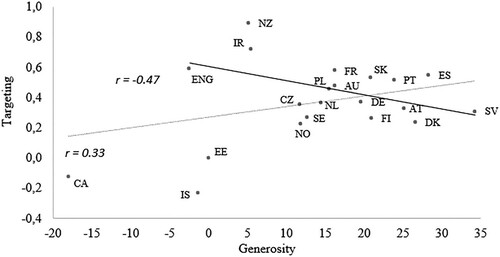

Second, countries with less degrees of targeting, and more generous net student support, rely more heavily on repayable support (with some exceptions – see Canada). It is noteworthy that almost no country achieved high levels of generosity without having a high share of student loans in the overall student support package. To further investigate this issue, shows the association between the degree of targeting and generosity of net student support after loans have been excluded from analysis. Once again we begin by analysing generosity as an average of our three model families.

Figure 3. Degree of targeting and generosity of net non-repayable student support for three model families in 21 OECD countries, 2010.

Comparative analyses of this kind are sensitive to developments in individual countries. Considering the data for all 21 OECD countries, the negative association between the degree of targeting and generosity changes to positive once repayable support is disregarded. At first sight, this finding may seem puzzling. However, it is solely the result of three very influential cases: Canada, Estonia, and Iceland.Footnote11 Once these countries are excluded from analysis, the association between targeting and generosity is in the expected negative direction (coefficient of −0.47), despite loans being excluded from analysis. Thus, heavy reliance on repayable support is not the sole driver of the negative association between targeting and generosity of net student support observed in this study.

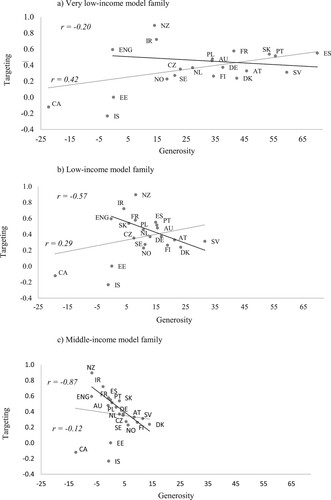

In (a–c), we once again disaggregate the analysis of net non-repayable support by model family (very low income, low income, and middle income). If we disregard our three influential cases, the results corroborate the findings above. Once again, the negative association between targeting and generosity grows stronger the further up the income distribution our model families are positioned.

Figure 4. (a–c). Degree of targeting in student finance systems and generosity of net total non-repayable student support (for a very low-income family), for 2010.

5.1. Sensitivity analyses

An alternative to conceptualize and measure the generosity of student finance is to keep the denominator constant (i.e. family income), which yields a concentration coefficient of exactly zero for countries relying exclusively on universal and flat-rate benefits. However, the overall pattern observed in our data hardly changes by this alternative measure of generosity. If anything, the correlation coefficient between the degree of targeting and generosity of net student support (as an average of our three model families) becomes somewhat stronger (c.f. −0.61). Thus, we use the measurement producing more conservative results.

We also examined how the results would change if we used an expenditure-based indicator instead of the generosity indicator. The results of this exercise are shown in . Here, we use OECD data on the share of total public higher education expenditures that were spent on student subsidies in 2009 (OECD Citation2012). Countries with a low degree of targeting typically spend a larger share of tertiary education budgets on student support. Expenditures on in-kind benefits or merit-based grants are in most countries included in OECD expenditure data. Disregarding them in the social rights analysis above does not seem to bias the results to any significant extent (neither does our focus on full-time undergraduate students).

Figure 5. Degree of targeting in net student support and public expenditure on student support as % of total public expenditure on tertiary education in 21 OECD countries.

Notably, in comparison to , some countries change positions once expenditures are in focus, largely reflecting the role of repayable loans in the overall structure of student support. It is not necessarily the case that higher public expenditures are a direct consequence of more recipients or higher benefits. In countries like Australia, New Zealand, and the United Kingdom, the level of student loans to large extent reflects the tuition fees they are supposed to cover. In these particular countries, public expenditures on student loans can be conceived as a substitution of state appropriations to higher education. Large parts of these expenditures come back to the state as loan repayments.Footnote12

6. Discussion

In this paper, we offered a new, social rights, approach to the comparative analysis of student finance. While acknowledging that our approach may not be universally superior to others, we argue that it provides an important complementary perspective to previous cross-national studies based on educational expenditures.

To demonstrate the usefulness of our approach, we performed a model family based analysis of student support in 21 OECD countries, accounting for the obligation of students to pay tuition fees. We found that students from low-income families not necessarily are financially better off in student support systems that target benefits to low-income families. Instead, there is a negative association between the degree of targeting and generosity of net student support (i.e. after tuition fees), even after excluding repayable support (i.e. student loans) from the analysis. Student support (net of fees) tends to be more generous in countries that most clearly deviate from a low-income strategy in policy-making. Thus, students from low-income families tend to benefit from a support system that includes students from middle-class families, lending some support to the political economy idea of a paradox of redistribution in social policy.

It should be noted that the negative association between the degree of targeting and generosity was quite weak when the analysis was restricted to the model family having the lowest income. Actually, at this very low level of income (half an average production worker’s wage for a four-person family), most countries provided relatively generous student support. It may be the case that the very low-income level assumed for this model family is not practically meaningful unless social assistance and other forms of policies for needy families are included in the analysis. Such inclusion of anti-poverty legislation is likely to increase the income level of model families in the lower part of the income distribution, and thus affect our measurement of student support by increasing the denominator in the measure of benefit generosity. The share of students from very poor families is also quite low in many countries (Jackson Citation2013). Providing this very small group with generous support is not only a limited burden on public budgets, but also aligns with the policy goal of equal access to higher education to which most of the countries officially subscribe (UNESCO Citation2017). To this extent, the political economy of student finance may be different from the one characterizing cash benefits more generally.

Countries with generous net student support tend to rely more extensively on student loans, which probably present the less costly option for public budgets in the long term.Footnote13 Cost-sharing arrangements that are largely based on loans may thus be both politically and economically feasible, while improving opportunities for students from low-income families to study full-time without being forced to part-time work. However, the extent to which student loans in combination with tuition fees is in agreement with equal access principles needs to be investigated and contrasted with the alternative of no fees, adding to the debate about debt aversion in student loan systems (Callender and Jackson Citation2008).Footnote14

The pervasiveness of state-subsidized loans in systems which are more generous for low-income students strengthens our conjecture about the virtuousness of more encompassing student finance arrangements that include the majority of students (usually coming from the middle-class) among the beneficiaries. It also opens up interesting avenues for further research. More detailed analyses accounting for a greater degree of model family representativeness in national student bodies is one way forward to substantiate our findings. Another alternative is to collect data for more years and countries. In this study, we are able to present only a snapshot of country differences in one particular year. Time-series data would make it possible to close in on the issue of causality, and model in more detail the extent to which the inclusion of middle-class students in support systems are to the benefit of students from less privileged backgrounds.

Given the ideological pressures and austerity policies pursued by governments in the aftermath of the global financial crisis beginning in 2007/2008, it would be interesting to analyse changes in the composition of student support, and its implications for generosity. To what extent have countries downsized non-repayable student support, and what are the consequences for the distributive profile of the overall system of student finance? Another interesting area of research is the potential impact of different student support systems on learning (e.g. cognitive abilities, grades, graduation on time), labour markets (e.g. student jobs, graduate employment), and socio-economic outcomes (e.g. inequalities of access to higher education, intergenerational mobility).

The social rights approach to the conceptualization and measurement of student finance systems provides great opportunities to shed new light on issues that for long has been debated in educational research, while opening up new important areas for research. The results presented in this study mark the first step of this research agenda to bridge analyses on educational policy and welfare systems.

Acknowledgements

A previous version of this paper has been presented at the 2018 annual conference of the Foundation for International Studies on Social Security in Sigtuna and at the 2018 annual conference of the Consortium of Higher Education Researchers in Moscow. The authors would like to thank for the useful comments and suggestions provided by colleagues participating in these conferences.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 For other classifications of different types of student support, see Heller and Callender (Citation2013) and Johnstone and Marcucci (Citation2010).

2 Student finance analyses have instead mostly been occupied with impacts on individual decisions, and therefore on outcomes such as enrolment or graduation (Dynarski and Scott-Clayton Citation2013). For extensive review of this literature, see Garritzmann (Citation2016).

3 These concerns contrast with other ideas regarding the provision and distribution of education. Sometimes education is considered a private good for which students should pay themselves, as investment in skills gives an advantage on the labour market (Paulsen Citation2001). The costs of education may also compete with other needs for public spending, introducing trade-offs in policy-making (Johnstone Citation2017). However, the remarks above should make it clear that the analysis of student finance is a long overdue addition to the social rights approach in welfare state analysis.

4 Recent studies also show that non-repayable grants can be effective in promoting access and graduation of low-income students (Castleman and Long Citation2016). Financial aid may also help increasing working class students’ integration at universities (Rubin and Wright Citation2017).

5 Since systems differ between parts of the United Kingdom, we decided to consider England.

6 The lowest maximum age of students eligible to financial support in the European countries we study is 25 in Poland and Slovakia. Regarding the amount of aid to which a student is entitled, the age typically does not matter.

7 Country differences in how other student characteristics, like disability or place of birth, are considered in the determination of eligibility and entitlements is an issue beyond the scope of the paper.

8 We chose to use an APWW as it is a readily available measure that allows us to calculate net incomes (after taxes and contributions) that in some countries determine entitlements to student support. Moreover, it corresponds to income levels of workers performing similar types of work, thus ensuring cross-country comparability of full-time working families.

9 We have not included a higher income case because it would typically not differ in entitlements from the middle-income case.

10 If we disregard that our model families have different levels of income, a universal flat-rate benefit would be perfectly equal with a concentration coefficient of zero. In terms of monetary units spent on benefits, everyone would receive exactly the same amount. However, in relation to household income, as measured here, the low-income model families receive more. This character of a universal and flat-rate benefit is observed in our data by a slight positive concentration coefficient. It indicates that the same amounts of benefit may radically improve the financial position of students from very poor families, whereas for richer students they are less significant. This relative perspective on income redistribution is consistent with the idea of a paradox of redistribution originally formulated by Korpi and Palme (Citation1998). See sensitivity analyses below for an alternative specification of generosity.

11 Iceland and Estonia rely exclusively on student loans (i.e. they have no direct or indirect support). Canada is exceptional as the repayable part of the student support package is almost fully offset by high tuition fees.

12 Repayment ratios differ across countries and parts of public outlays on loans are de facto direct non-repayable support (Ziderman Citation2013).

13 We leave aside for now the problem of debt burden, and the risks related to potential default of ex-students, as we believe that this is mainly a consequence of instability on the labour market (mainly youth un- or under-employment) and student loan designs which do not properly account for potential employment difficulties of former students.

14 It is also important to note that countries with indirect family support tend to have comparatively meagre and targeted student finance systems. This may be because they predicate the cost-sharing arrangements on the idea of the family taking the responsibility for the material well-being of young adults (cf. the notion of familialization in Chevalier [Citation2016]).

References

- Agasisti, T., and S. Murtinu. 2016. “Grants in Italian University: A Look at the Heterogeneity of Their Impact on Students’ Performances.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (6): 1106–32. doi:10.1080/03075079.2014.966670.

- Ansell, B. 2010. From the Ballot to the Blackboard: The Redistributive Political Economy of Education. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Baert, S., I. Marx, B. Neyt, E. Van Belle, and J. Van Casteren. 2018. “Student Employment and Academic Performance: An Empirical Exploration of the Primary Orientation Theory.” Applied Economics Letters 25 (8): 547–52. doi:10.1080/13504851.2017.1343443.

- Barr, N., B. Chapman, L. Dearden, and S. Dynarski. 2018. “The US College Loans System: Lessons from Australia and England.” Economics of Education Review. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2018.07.007.

- Bradshaw, J., J. Ditch, H. Holmes, and P. Whiteford. 1993. “A Comparative Study of Child Support in Fifteen Countries.” Journal of European Social Policy 3 (4): 255–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/095892879300300402

- Brady, D., and A. Bostic. 2015. “Paradoxes of Social Policy Welfare Transfers, Relative Poverty, and Redistribution Preferences.” American Sociological Review 80 (2): 268–98. doi:10.1177/0003122415573049.

- Callender, C., and J. Jackson. 2008. “Does the Fear of Debt Constrain Choice of University and Subject of Study?” Studies in Higher Education 33 (4): 405–29. doi:10.1080/03075070802211802.

- Castleman, B. L., and B. T. Long. 2016. “Looking Beyond Enrollment: The Causal Effect of Need-Based Grants on College Access, Persistence, and Graduation.” Journal of Labor Economics 34 (4): 1023–73. doi: https://doi.org/10.1086/686643

- Chevalier, T. 2016. “Varieties of Youth Welfare Citizenship: Towards a Two-Dimension Typology.” Journal of European Social Policy 26 (1): 3–19. doi:10.1177/0958928715621710.

- Chevalier, T. 2018. “Social Citizenship of Young People in Europe: A Comparative Institutional Analysis.” Journal of Comparative Policy Analysis: Research and Practice 20 (3): 304–23. doi:10.1080/13876988.2017.1320160.

- Clasen, J., and N. Siegel, eds. 2007. Investigating Welfare State Change: The ‘Dependent Variable’ Problem in Comparative Analysis. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar.

- De Deken, J., and J. Clasen. 2013. “Benefit Dependency: The Pros and Cons of Using ‘Caseload’ Data for National and International Comparisons.” International Social Security Review 66 (2): 53–78. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/issr.12009

- Dearden, L., E. Fitzsimons, and G. Wyness. 2014. “Money for Nothing: Estimating the Impact of Student Aid on Participation in Higher Education.” Economics of Education Review 43: 66–78. doi:10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.09.005.

- Dynarski, S., and J. Scott-Clayton. 2013. “Financial Aid Policy: Lessons from Research.” The Future of Children 23 (1): 67–91. doi:10.3386/w18710 doi: https://doi.org/10.1353/foc.2013.0002

- Ertl, H., and C. Dupuy. 2014. Students, Markets and Social Justice: Higher Education Fee and Student Support Policies in Western Europe and Beyond. Oxford: Symposium Books.

- Esping-Andersen, G. 1990. The Three Worlds of Welfare Capitalism. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

- Ferrarini, T., K. Nelson, W. Korpi, and J. Palme. 2013. “Social Citizenship Rights and Social Insurance Replacement Rate Validity: Pitfalls and Possibilities.” Journal of European Public Policy 20 (9): 1251–66. doi:10.1080/13501763.2013.822907.

- Garritzmann, J. L. 2016. The Political Economy of Higher Education Finance. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Garritzmann, J. L. 2017. “The Partisan Politics of Higher Education.” PS: Political Science and Politics 50 (2): 413–417. doi:10.1017/S1049096516002924.

- Hauschildt, K., Ch. Gwosć, N. Netz, and S. Mishra. 2015. Social and Economic Conditions of Student Life in Europe – Synopsis of Indicators. EUROSTUDENT 2012–2015. W. Bertelsmann Verlag, Bielefeld.

- Heller, D. E., and C. Callender, eds. 2013. Student Financing of Higher Education. A Comparative Perspective. New York: Routledge.

- Jackson, M. 2013. Determined to Succeed? Performance Versus Choice in Educational Attainment. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Johnstone, D. B. 2004. “The Economics and Politics of Cost-Sharing in Higher Education: Comparative Perspectives.” Economics of Education Review 23: 403–410. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2003.09.004

- Johnstone, D. B. 2017. “Cost-Sharing in Financing Higher Education.” In Encyclopedia of International Higher Education Systems and Institutions, edited by J. Shin and P. Teixeira. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Johnstone, D. B., and P. Marcucci. 2010. Financing Higher Education Worldwide. Who Pays? Who Should Pay? Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Johnstone, B., P. Teixeira, M. J. Rosa, and H. Vossensteyn. 2006. “Introduction.” In Cost-Sharing and Accessibility in Higher Education: A Fairer Deal?, edited by P. Teixeira, B. Johnstone, M. J. Rosa, and H. Vossensteyn, 1–18. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Kakwani, N. C. 1986. Analyzing Redistribution Policies: A Study Using Australian Data. New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Kenworthy, L. 2011. Progress for the Poor. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Korpi, W. 1989. “Power, Politics, and State Autonomy in the Development of Social Citizenship.” American Sociological Review 54 (3): 309–328. doi:10.2307/2095608.

- Korpi, W., and J. Palme. 1998. “The Paradox of Redistribution and Strategies of Equality: Welfare State Institutions, Inequality, and Poverty in the Western Countries.” American Sociological Review 63 (5): 661–87. doi:10.2307/2657333.

- Marcucci, P. 2013. “The Politics of Student Funding Policies from a Comparative Perspective.” In Student Financing of Higher Education. A Comparative Perspective, edited by D. E. Heller and C. Callender, 9–31. New York: Routledge.

- Marshall, T. H. 1950. Citizenship and Social Class and Other Essays. London: Cambridge University Press.

- Marx, I., and K. Nelson, eds. 2013. Minimum Income Protection in Flux. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Marx, I., L. Salanauskaite, and G. Verbist. 2016. “For the Poor, but Not Only the Poor: On Optimal Pro-Poorness in Redistributive Policies.” Social Forces 95 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1093/sf/sow058.

- Morel, N., B. Palier, and J. Palme. 2012. Towards a Social Investment Welfare State? Ideas, Policies and Challenges. Bristol, UK: Policy Press.

- Nelson, K., and J. Fritzell. 2014. “Welfare States and Population Health: The Role of Minimum Income Benefits for Mortality.” Social Science and Medicine 112: 63–71. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2014.04.029

- OECD. 2012. Education at a Glance. Paris: OECD.

- Orr, D., J. Wespel, and A. Usher. 2014. Do Changes in Cost-Sharing Have an Impact on the Behaviour of Students and Higher Education Institutions? Evidence from Nine Case Studies. Vol. 1. Luxembourg: Publications Office of the European Union.

- Paulsen, M. B. 2001. “The Economics of Human Capital and Investment in Higher Education.” In The Finance of Higher Education: Theory, Research, Policy and Practice, edited by M. B. Paulsen and J. C. Smart, 55–94. New York: Agathon Press.

- Pfeffer, F. T. 2015. “Equality and Quality in Education. A Comparative Study of 19 Countries.” Social Science Research 51: 350–68. doi:10.1016/j.ssresearch.2014.09.004.

- Rubin, M., and Ch. L. Wright. 2017. “Time and Money Explain Social Class Differences in Students’ Social Integration at University.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (2): 315–30. doi:10.1080/03075079.2015.1045481.

- UNESCO. 2017. Six Ways to Ensure Higher Education Leaves No One Behind. Policy Paper 30. Accessed February 19 2019. https://en.unesco.org/gem-report/six-ways-ensure-higher-education-leaves-no-one-behind.

- Van Oorschot, V. 2013. “Comparative Welfare State Analysis with Survey-Based Benefit: Recipiency Data: The ‘Dependent Variable Problem’ Revisited.” European Journal of Social Security 15 (3): 224–48. doi:10.1177/138826271301500301.

- Willemse, N., and P. de Beer. 2012. “Three Worlds of Educational Welfare States? A Comparative Study of Higher Education Systems Across Welfare States.” Journal of European Social Policy 22 (2): 105–17. doi:10.1177/0958928711433656.

- Ziderman, A. 2013. “Student Loan Schemes in Practice: A Global Perspective.” In Student Financing of Higher Education. A Comparative Perspective, edited by D. E. Heller and C. Callender, 32–60. New York: Routledge.