ABSTRACT

Based on Young’s notion of powerful knowledge, acquiring disciplinary knowledge emerging from an economic epistemic community is expected to make an important difference for people when dealing with economic issues in their daily lives. In this regard, this article’s author asked Swedish scholars of economics at higher education institutions what they considered to be the most important economic concepts that people would need to acquire and understand. The article provides knowledge about the case of Sweden as a contribution to existing research. Although the article does not suggest a list of key concepts, the results clearly bear close similarities to the economic concepts proposed within the framework of threshold concepts. These concepts is one important resource to be considered when deciding on what economic content students should have access to in school enabling them to face economic issues in their private and public lives.

Introduction

People need economic knowledge to make well-informed decisions when facing economic questions in their private and public lives (Stigler Citation1983; Steiner Citation2001; VanFossen Citation2005; Miller and VanFossen Citation2008; Jappelli Citation2010). However, research from different parts of the world has shown that adults, students and youngsters alike often lack economic knowledge (Walstad and Allgood Citation1999; Davies et al. Citation2002; Hansen, Salemi, and Siegfried Citation2002; Lusardi and Mitchell Citation2011; Wobker et al. Citation2014; Erner, Goedde-Menke, and Oberste Citation2016). It is a cause of concern that economic illiteracy seems widespread, as it can limit people’s ability to perceive the economic dimensions of the complex problems they encounter in their everyday lives. Economic illiteracy might also have negative effects on individuals and on society as a whole.

According to research, the lack of economic knowledge is even pervasive amongst social studies teachers, who are responsible for providing basic economic education (McKenzie Citation1971; Garman Citation1979; McKinney et al. Citation1990; Sosin, Dick, and Reiser Citation1997; Scahill and Melican Citation2005; Maier and Nelson Citation2007; Miller and VanFossen Citation2008; Bernmark-Ottosson Citation2009; Grimes, Millea, and Thomas Citation2010; Asano, Yamaoka, and Abe Citation2013; Löfström and van den Berg Citation2013; Akhan Citation2014; Kristiansson Citation2014; Anthony, Smith, and Miller Citation2015; Ayers Citation2016; Modig Citation2017). This issue is a cause of concern because schools are important arenas for acquiring knowledge, which also means that the current lack of economic knowledge risks becoming more prevalent, thereby raising questions on the kind of economic knowledge that people need to master and the specific areas of economics that ought to be taught in schools and in teacher preparation programmes.

The Voluntary National Content Standards in Economics for American students from kindergarten to the twelfth grade (K–12) and the economic framework developed within the theory of threshold concepts (e.g. Reimann and Jackson Citation2006; Shanahan, Foster, and Meyer Citation2006; Davies and Mangan Citation2007; O’Donnell Citation2009; Löw Beer Citation2016; Shanahan Citation2016) are (together with leading economics textbooks) possible sources for identifying important economic knowledge. According to Young’s (Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2013a) discussion about powerful knowledge, disciplinary knowledge derived from epistemic communities is one relevant source for identifying important economic knowledge. However, this knowledge does not appear to be systematically mapped. Therefore, in this present study, the author sent online questionnaires to 419 scholars of economics at universities in Sweden, asking them what economic concepts they found most important for people to know and master as individuals and citizens so that they would become economically well-informed. Even though a consensus amongst all experts most likely does not exist, the Swedish scholars can contribute with an overview of the concepts that they think are important to master. This knowledge constitutes the case of Swedish scholars and can be added to existing research.

Important economic knowledge, identified from educational standards and the theory of threshold concepts, for example, seems conventional in many cases. However, an ongoing discussion, both inside and outside the discipline, argues about whether this kind of economics actually provides humans with adequate tools to understand and manage issues in a changing society, such as global inequality, environmental degradation and climate change. Therefore, it has been suggested that economic education needs more pluralistic perspectives to educate students to become intellectually independent persons with critical judgemental skills and new ways of economic thinking that better incorporate humanitarian and ecological values into the economic system (Denis Citation2009; Garnett and Reardon Citation2012; Brant Citation2015; Raworth Citation2017). Such pluralistic perspectives can of course be mapped by asking other groups besides economists. However, to be able to question existing systems on rational grounds, people need knowledge of what they are questioning. Krugman (Citation1999) writes:

Anyone who has ever made the effort to understand a really useful economic model (like simple models on which economists base their argument for free trade) learns something important: The model is often smarter than you are. What I mean by that is that the act of putting your thoughts together into a coherent model often forces you into conclusions you never intended, forces you to give up fondly held beliefs. The result is that people who have understood even the simplest, most trivial-sounding economic models are often far more sophisticated than people who know thousands of facts and hundreds of anecdotes, who can use plenty of big words, but have no coherent framework to organize their thoughts (Krugman Citation1999, 113).

Earlier research

What is important economic knowledge?

There is an ongoing discussion about the economic content that is important for making progress when learning economics, such as within the theory of threshold concepts, introduced by Meyer and Land (Citation2003). The basic idea is that specific concepts within each discipline need to be understood and mastered in order to make progress. In the efforts to identify potential threshold concepts in economics, Davies and Mangan (Citation2007) suggest a web of concepts consisting of opportunity cost, economic modelling, margin, welfare and efficiency, comparative advantage, partial equilibrium, interactions between markets, elasticity and cumulative causation. Other researchers have also suggested opportunity cost as a potential economic threshold concept (e.g. Reimann and Jackson Citation2006; Shanahan, Foster, and Meyer Citation2006; Shanahan Citation2016). Reimann and Jackson (Citation2006) suggest elasticity as a potential threshold concept, and Löw Beer (Citation2016) indicates that market failure and externalities could be added to web threshold concepts. Shanahan (Citation2016) argues that opportunity cost can be very useful as a threshold concept that helps students enhance their understanding of economics, as this concept underpins production possibility frontiers and serves as the foundation of other economic concepts, such as consumers’ choice, demand schedules, the decision to supply, perfect competition, efficiency, comparative advantage, incentives, price signals and markets. The threshold concepts suggested by Davies and Mangan (Citation2007) have also been used in Karunaratne, Breyer, and Wood’s (Citation2016) research when they redesigned an entry-level economics course at a university in Australia.

Significant work regarding the aims and the content of economics education has likewise been undertaken in the US. Guides on the economics content to be taught at the pre-college level have been published for about 60 years, whose purpose is to direct school districts, curriculum developers, developers of educational materials and teachers on the economic content that ought to be taught, the reason for it and when to do so. The present version of the Voluntary National Content Standards in Economics for American students from kindergarten to the twelfth grade (K–12) contains 20 essential principles of economics that every student should know, as well as include the most important and enduring ideas, concepts and issues in economics based on a neoclassical economic model. The standards are produced by a broad coalition of academic economists, economic educators and representatives of several universities and organisations (Siegfried and Meszaros Citation1998; VanFossen Citation1999; Siegfried and Krueger Citation2010; Walstad and Watts Citation2015).

Of course, important economic knowledge can also be derived from leading textbooks, such as Samuelson’s Economics in 1948, which is currently available in its 19th edition (Samuelson and Nordhaus Citation2010). It can still be considered the gold standard in teaching economics and has significantly influenced other textbooks in this field (Skousen Citation1997; Gottesman, Ramrattan, and Szenberg Citation2005; Green Citation2012). These textbooks affect pedagogical and epistemological processes, as they introduce students to the dominant orthodox narrative in economics, with the result that students ‘retell the received “stories” of economics’ (Richardson Citation2004, 518). When studying the theory of threshold concepts, the US standards and the classical textbooks in economics (e.g. Samuelson’s Economics), the picture emerging is that the neoclassical paradigm dominates in the sense that the same concepts, ideas and principles are emphasized. Nonetheless, how do educators and policymakers know that this is important economic knowledge for the twenty-first century? In the following excerpt, Raworth (Citation2017) raises questions on the commonly taught economic content:

Humanity’s journey through the twenty-first century will be led by the policymakers, entrepreneurs, teachers, journalists, community organizers, activists and voters who are being educated today. But these citizens of 2050 are being taught an economic mindset that is rooted in textbooks of 1950, which in turn are rooted in the theories of 1850 (Raworth Citation2017, 7).

Undoubtedly, the world is facing new challenges that require new and more pluralistic perspectives on economics. Having some knowledge about the economic framework enables people to discuss and question existing systems; therefore, it is relevant to ask scholars of economics what they consider important economic knowledge.

Why is economic knowledge important?

Having economic knowledge is important because economic issues affect people in their many different roles, for instance, as citizens, consumers, workers and producers. Many decisions on public and private concerns involve economic perspectives, and it is important that people can apply economic reasoning to different issues (Steiner Citation2001; Miller and VanFossen Citation2008; Jappelli Citation2010). Furthermore, Rata (Citation2018) writes that a connection exists between the rational knowledge provided by schools and democratic socialisation and that rationally structured knowledge can function as a tool for thinking and as a means of communication. Different kinds of knowledge – in this case, economic knowledge – can therefore serve as tools for effective citizenship and as means of preserving democratic values.

However, research shows that people generally know little about economics. This seems to be the case in the US (Walstad and Allgood Citation1999; Hansen, Salemi, and Siegfried Citation2002), and the situation appears similar in European countries, Japan and New Zealand (Davies et al. Citation2002; Lusardi and Mitchell Citation2011; Wobker et al. Citation2014; Erner, Goedde-Menke, and Oberste Citation2016). The lack of education likely explains the described situation. Schools are important arenas for acquiring different kinds of knowledge. Perhaps a contributory reason for people’s seeming lack of economic knowledge is that even in-service and pre-service social studies teachers, who are or will be responsible for providing basic economic education, show a low level of economic understanding, which negatively affects their ability to teach economics (McKenzie Citation1971; Garman Citation1979; McKinney et al. Citation1990; Sosin, Dick, and Reiser Citation1997; Grimes, Millea, and Thomas Citation2010; Asano, Yamaoka, and Abe Citation2013; Anthony, Smith, and Miller Citation2015). Research likewise suggests that high school social studies teachers in the US seem to have minimal training in economics and that social studies pre-service teachers have less formal training in economics than those in many other social studies disciplines (Maier and Nelson Citation2007; Miller and VanFossen Citation2008; Ayers Citation2016; Henning and Lucey Citation2017). Research from Sweden indicates that pre-service social studies teachers have insufficient economic knowledge and find it difficult to teach economics (Bernmark-Ottosson Citation2009; Kristiansson Citation2014; Modig Citation2017), whereas Finnish research finds that social studies teachers need additional economics training (Löfström and van den Berg Citation2013). Research conducted in Turkey likewise demonstrates that social studies teacher candidates misunderstand economic concepts and that students have limited economic knowledge (Akhan Citation2014).

Given that economic knowledge has a major impact on individuals and on society and that economic illiteracy is widespread, it is relevant to clarify the economic concepts that are important for people to know and master. The ideas and principles suggested in the theory of threshold concepts, the standards developed in the US and the content of economic textbooks are some important sources. However, Raworth (Citation2017) and otheŕs discussion about alternative economics perspective should not be neglected. Nevertheless, there is a lack of research that performs more systematic procedures on mapping what can be considered important economic knowledge in everyday life, according to the viewpoint of scholars of economics. This article presents the results of a survey involving economic scholars, who were asked about what they regarded as important economic concepts that would be worth knowing when coping with private and public issues in everyday life.

Theoretical outset: threshold concepts and powerful knowledge as principles for curriculum development

The set of threshold concepts can be viewed as a doorway to completely new ways of understanding and thinking about something. Meyer and Land (Citation2003) propose five characteristics of a threshold concept. When a concept fundamentally and permanently changes a person’s way of understanding something, for example, a discipline, and even one’s way of perceiving the world, the concept can be claimed as transformative. Once this new and deepened way of understanding something is achieved, it is unlikely to be forgotten; in other words, it is irreversible. A threshold concept also integrates with other concepts within a discipline and makes it possible to discover previously hidden connections between concepts within the discipline. At the same time, it tends to mark a boundary of a way of thinking within a certain discipline and distinguishes it from other disciplines (Meyer and Land Citation2003; Davies Citation2012). Altogether, this means that learning threshold concepts is often troublesome for students, as doing so entails a reconstruction of prior learning. Threshold concepts operate deeply within a discipline, are often taken for granted by practitioners and are therefore rarely explicated (Davies Citation2006, Citation2012). The theory of threshold concepts has been criticised (e.g. O’Donnell Citation2009, Citation2010; Quinlan et al. Citation2013), as researchers have not reached a consensus on how such concepts can be identified or distinguished from other concepts that can be troublesome. However, the discussion on this issue is ongoing (e.g. Basgier and Simpson Citation2019; Hill Citation2019).

Young’s (Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2013a, Citation2013b, Citation2014) notion of powerful knowledge can be related to the theory of threshold concepts, as it highlights the relation between everyday knowledge and discipline-based, subject-specific knowledge. Young (Citation2008, Citation2009) distinguishes between everyday knowledge and specialist knowledge and argues that the purpose of education is to prepare learners to understand and navigate in the world in which they live. When people study, their everyday knowledge meets discipline-based, subject-specific knowledge, and education provides access to specialised knowledge in different subjects. The starting point is that discipline-based, subject-specific knowledge can open up new perspectives beyond everyday experiences so that the world and solutions to problems in the world can be understood in alternative and more qualified ways, and people can therefore develop the skills required to function effectively and wisely in society.

Powerful knowledge occurs in all disciplines, and there are at least two ways of understanding it. Lambert (Citation2014) summarises the first type of powerful knowledge as evidence based, abstract, theoretical, part of a system of thought, dynamic, evolving and changing but reliable, testable and open to challenge, sometimes counter-intuitive, discipline based and existing outside the direct experience of the teacher and the learner. Maude (Citation2016) summarises the second type of powerful knowledge, which enables people to discover new ways of thinking, better explain and understand the natural and the social worlds, think about alternative futures and what they could do to influence these potential outcomes, wield some power over their own knowledge, engage in current debates of significance and exceed the limits of their personal experience. Maude (Citation2016) argues that the two ways of understanding powerful knowledge are interrelated, as the outcomes are likely to be derived from the first type of powerful knowledge.

Threshold concepts and powerful knowledge as analytical tools

If we accept that subject-specific knowledge based on certain concepts, ideas and perspectives, is more powerful than other types of knowledge and could be derived from essential and disciplinary knowledge, this most likely must be the case in economics, too. However, we need to know the object of such powerful knowledge and to clarify its purpose. Nordgren (Citation2017) and Deng (Citation2015) argue that if powerful knowledge is used as a means of disciplinary knowledge it becomes a resource for the development of students’ intellectual and moral powers or capacities. It means that acquiring in-depth economic knowledge provides people with powerful economic knowledge, enabling them to better act in, understand, discuss and question the prevailing system.

Threshold concepts and powerful knowledge are used here as parts of a theoretical framework that discusses the relation between discipline-based, subject-specific knowledge and everyday knowledge.

Methods

Survey design and data collection

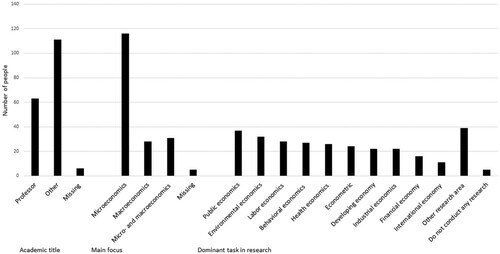

The results are drawn from an online questionnaire (see Appendix 1) sent to all identified (419) economists in all 48 higher education institutions in Sweden, except nine economists at the author’s own university. Of the 327 (78%) males and 92 (22%) females in the total target population, 180 answered the questionnaire, of whom 138 (76.7%) were males and 42 (23.3%) were females. In the total population, 155 (37%) were professors, and 264 (63%) were other economists with an academic degree lower than that of a professor. Out of the 180 respondents, 63 (35%) were professors, 111 (61.7%) were other economists, and 6 (3.3%) did not provide information about their academic title. Thus, the sample was similar to the total population in terms of gender breakdown and academic title. Almost all questions were answered by all participants, except the third question about their academic title (174 answers) and the fourth question about their main focus (175 answers).

The questionnaire was developed in October 2017, and the data were collected from November 13–28, 2017.

Empirical approach

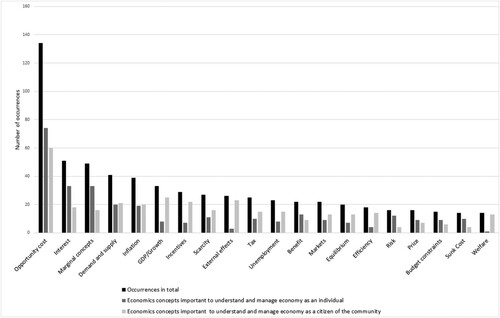

Two items (questions 10 and 11) in the questionnaire are of particular importance, focussing on what the economists consider to be the most important concepts in economics for people to acquire and understand. Both questions were open ended, making it possible to list an unlimited number of concepts for each question. The concepts were summarised based on frequency and then sorted into broader categories; for example, all concepts about gross domestic product (GDP) and growth were merged into one category, and so were all concepts about margin and interest. A second round of review by an economist at the author’s own university was conducted to ensure that the categories were reasonable. lists the 20 categories in a chart to obtain an overall picture of the total frequency of each category. However, categories in the seventh place have fewer than 30 occurrences in the overall list and are therefore excluded from further analysis.

Figure 3. Economic concepts that are important to acquire and understand from the citizen perspective.

The data on the demographic variables (birth decade, gender, academic title and main focus) were also collected. The relations between the demographic variables and the top six categories listed in are presented in a and b.

Analytical steps

The results were analysed in three steps. First, the material was examined through a descriptive analysis, focussing on frequencies and percentages ( and a and b). Second, correlation and cross-tabulation analysis were conducted regarding the concepts suggested from the individual and the citizen perspectives ( and ). Third, the material was analysed in relation to Young’s (Citation2008, Citation2009, Citation2013a, Citation2013b, Citation2014) notion of powerful knowledge and to the theory of threshold concepts (Meyer and Land Citation2003) to clarify if any economic concepts could be considered particularly important for people to know and master (see for the assay protocol regarding step three).

Figure 1. Respondents’ academic titles, main research foci and dominant research tasks. Note that the sum of the proportions would be higher than 180 respondents (100%) regarding the dominant research task because it was possible to respond to more than one alternative.

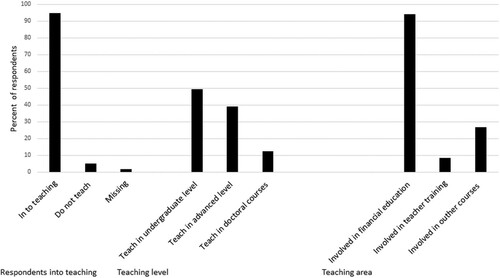

Figure 2. Respondents in the field of teaching, their teaching levels and teaching areas. Note that the sum of the proportions would be higher than 100% regarding the teaching level and the teaching area because it was possible to respond to more than one alternative.

Table 1. Assay protocol.

Results and analysis

About half (50.6%) of the responding economists were born in 1940–1969, whereas 49.4% were born in 1970–1999. The respondents are mainly focussed on research in microeconomics (66.3%, 116). The dominant task is research, and the most common research area is public economics (20.6%, 37), followed by environmental economics (17.8%, 32), labour economics (15.6%, 28), behavioural economics (15%, 27), health economics (14.4%, 26), econometrics (13.3%, 24), development economics (12.2%, 22) and industrial economics (12.2%, 22) ().

Almost everyone (94.9%, 168 out of 177 respondents, three respondents were missing) teaches. Out of the 168 who teach, 49.4% (83) handle undergraduate-level courses, followed by advanced-level (39.2%, 66) and PhD courses (12.5%, 21). Most of those who teach are in the field of financial education (94%, 158), whereas 8.3% (14) teach in the field of teacher training education ().

As shown in , opportunity cost is the largest category when the individual (74) and the citizen perspectives (60) are merged, with a total of 134 occurrences, followed by interest, with 51 occurrences (33 from the individual perspective and 18 from the citizen perspective), and marginal concepts, with 49 occurrences (33 from the individual perspective and 16 from the citizen perspective).

A comparison shows that 10 categories (opportunity cost, interest, marginal concepts, demand and supply, inflation, scarcity, tax, market, GDP/growth and unemployment) are amongst the top 15 in each perspective. Five categories (benefit, risk, sunk cost, budget constraints and price) amongst the top 15 in the individual perspective do not qualify for the top 15 when both perspectives are merged. Five categories (external effects, incentives, efficiency, equilibrium and welfare) are amongst the top 15 in the citizen perspective but not when both perspectives are merged. presents the 20 categories from both perspectives, although some categories do not make it to the top 15 when the perspectives are merged. An example is the welfare concept in 14th place in the citizen perspective, but it falls to the bottom in the individual perspective, with only one occurrence.

shows a rather strong positive correlation (.535***) between opportunity cost from the individual and the citizen perspectives. Likewise, a strong positive correlation (.569***) exists regarding inflation. The situation is similar regarding interest and demand and supply. A positive correlation also exists between GDP and inflation from the individual perspective (.365***) and from the citizen perspective (.420***) and between the individual and the citizen perspectives (.333***). However, a negative correlation is found between opportunity cost and interest from the individual perspective (−.192**) and between opportunity cost and inflation from the citizen perspective (−.213**). shows that a concept that is considered important from the individual perspective also seems important from the citizen perspective, which is most clearly the case regarding opportunity cost, inflation, and demand and supply. Out of the 74 respondents who find opportunity cost important from the individual perspective, 47 (63.5%) also regard opportunity cost as important from the citizen perspective. Moreover, 19 respondents find inflation important from the individual perspective, and out of them, 12 (63.2%) also consider inflation important from the citizen perspective. Of the 20 respondents who find demand and supply important from the individual perspective, 10 (50%) also perceive it as important from the citizen perspective.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics and correlation matrix for important economic concepts according to Swedish scholars of economics.

Table 3. The combinations of concepts suggested in the individual perspective and citizen perspective, percent (n).

presents the responses to the question of whether (and if so, in what ways) demographic variables affect how Swedish economists propose important economic concepts from the individual perspective. presents the responses to the same two questions, this time from the citizen perspective. In general, small variations are found in the demographic variables. However, one pattern is that microeconomists tend to find opportunity cost and marginal concepts more important than macroeconomists do, whereas macroeconomists tend to view interest as more important than microeconomists do. It also seems that younger economists perceive interest as more important than their older counterparts do. Regarding marginal concepts, younger economists, women and microeconomists tend to find them more important than older economists, men and macroeconomists do. Professors tend to regard demand and supply as more important than other economists do, whereas other economists and macroeconomists seem to consider inflation more important than professors and microeconomists do.

Table 4a. Percentages and frequencies regarding biographical variables and concepts suggested in the individual perspective.

Table 4b. Percentages and frequencies regarding biographical variables and concepts suggested in the citizen perspective

The analysis of how the top 20 categories listed in can be related to the 20 standards in the Voluntary National Content Standards in Economics clearly shows the categories’ several connections to the standards. Furthermore, the comparison of the concepts suggested by the Swedish economists with the potential web of economic threshold concepts suggested by Davies and Mangan (Citation2007) indicates the similarities between such concepts. For example, opportunity cost and margin are important concepts amongst Swedish economists and are also part of the suggested web of economic threshold concepts. The concepts likewise occur in the Voluntary National Content Standards in Economics. Together with the results of the correlation and cross-tabulation analysis, these findings make it relevant to discuss these concepts and ideas, especially the top six concepts, as constituting important economic knowledge that can function as powerful economic knowledge.

Conclusion and suggestions for further discussion

Although this article only provides knowledge in the case of Sweden (based on a survey questionnaire answered by 180 out of 419 Swedish scholars of economics) as a contribution to existing research, the results give an idea of the concepts and the principles that can be considered important economic knowledge from a disciplinary perspective. Opportunity cost, interest, marginal concepts, demand and supply, inflation and GDP/growth are concepts regarded as important, and amongst them, opportunity cost seems to be a key concept. Due to the clear points of contact between the concepts proposed by the Swedish economists, those put forward within the framework of threshold concepts and those set by US standards, it is reasonable to assume that these three perspectives could together constitute important powerful economic knowledge from a disciplinary perspective. This premise might be explained by the fact that almost every economic principle is based on long-time agreed assumptions. However, further systematic studies need to be carried out in other countries to examine whether the results can be replicated before it is possible to make more solid generalisations. To obtain a more systematic and complete picture of the concepts and the principles that can be considered important economic knowledge from the perspective of economic epistemic communities, it is suggested that surveys, such as the one conducted in this study, be undertaken in other countries. In further research, it would also be interesting to pose similar questions to other groups (e.g. entrepreneurs, technology scientists, policymakers, ordinary people, etc.) to obtain views of the concepts and the factors that might be considered important economic knowledge from other perspectives. Such studies could help provide an understanding of what kind of economic knowledge the educational system delivers today and the concepts and the principles that might be perceived as important economic knowledge for the future.

Economic knowledge has mainly been discussed in this article from a disciplinary perspective in an attempt to determine the kind of economic knowledge needed by people to cope with everyday life in a more qualified way and therefore ought to be taught in schools. If we want to discuss and challenge what important economic knowledge for the twenty-first century might be, we must do so based on solid information; we must know something about what we are questioning. This key issue makes it relevant to discuss the proposed economic concepts and principles as powerful economic knowledge because they are specialised, have been developed by economic experts within an epistemic community and enable people to think and talk about issues in a new and more well-informed way. However, powerful economic knowledge should be considered a means that can help people deal with economic questions, rather than an end that simply constitutes determined and persistent knowledge. Powerful economic knowledge thereby becomes a resource that helps people develop better and more qualified ways of handling everyday situations. Therefore, the curriculum principle that specialised knowledge emerges from within epistemic communities and constitutes one important piece of the economic puzzle (amongst others) should be considered when deciding on the subject-matter content to teach in schools as important economic knowledge.

Acknowledgements

The author would like to thank the many economists in Sweden for participating in the survey. Associate Professor Niklas Jakobsson, Dr Martin Kristiansson, Associate Professor Katarina Katz, Dr Johan Kaluza and Dr Daniel Bergh provided valuable feedback on the drafts of this article, for which the author is grateful.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

References

- Akhan, N.E. 2014. “Economic Literacy Levels of Social Studies Teacher Candidates.” World Journal of Education 5 (1): 25–39. doi:10.5430/wje.v5n1p25.

- Anthony, K.V., R.C. Smith, and N.C. Miller. 2015. “Preservice Elementary Teachers’ Economic Literacy: Closing Gates to Full Implementation of the Social Studies Curriculum.” Journal of Social Studies Research 39 (1): 29–37. doi:10.1016/j.jssr.2014.04.001.

- Asano, T., M. Yamaoka, and S. Abe. 2013. “The Quality and Attitude of High School Teachers of Economics in Japan: An Explanation of Sample Data.” Journal of Social Science Education 12 (2): 69–78. doi.org/10.4119/jsse-648.

- Ayers, C.A. 2016. “Developing Preservice and Inservice Teachers’ Pedagogical Content Knowledge in Economics.” Social Studies Research and Practice 11 (1): 73–92.

- Basgier, C., and A. Simpson. 2019. “Trouble and Transformation in Higher Education: Identifying Threshold Concepts Through Faculty Narratives About Teaching Writing.” Studies in Higher Education, doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1598967.

- Bernmark-Ottosson, A. 2009. “Samhällskunskapslärare.” In Ämnesdidaktiska Insikter och Strategier, Studier i de Samhällsvetenskapliga ämnenas Didaktik nr. 1, edited by Bengt Schüllerqvist, and Christina Osbeck, 33–82. Karlstad: Karlstads Universitet.

- Brant, J.W. 2015. “What’s Wrong with Secondary School Economics and How Teachers Can Make it Right – Methodological Critique and Pedagogical Possibilities.” Journal of Social Science Education 14 (4): 7–17. doi:0.2390/jsse-v14-i4-1391.

- Davies, P. 2006. “Educating Citizens for Changing Economies.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 38 (1): 15–30. doi:10.1080/00220270500185122.

- Davies, P. 2012. “Threshold Concepts in Economics Education.” In International Handbook on Teaching and Learning Economics, edited by Gail M. Hoyt, and KimMarie McGoldrick, 250–256. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Davies, P., H. Howie, J. Mangan, and S. Telhaj. 2002. “Economic Aspects of Citizenship Education: An Investigation of Students’ Understanding.” The Curriculum Journal 13 (2): 201–223. doi:10.1080/09585170210136859.

- Davies, P., and J. Mangan. 2007. “Threshold Concepts and the Integration of Understanding in Economics.” Studies in Higher Education 32 (6): 711–726. doi:10.1080/03075070701685148.

- Deng, Z. 2015. “Content, Joseph Schwab and German Didaktik.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 47 (6): 773–786. doi:10.1080/00220272.2015.1090628.

- Denis, A. 2009. “Editorial: Pluralism in Economics Education.” International Review of Economics Education 8 (2): 6–22. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1477-3880(15)30071-2

- Erner, C., M. Goedde-Menke, and M. Oberste. 2016. “Financial Literacy of High School Students: Evidence From Germany.” Journal of Economic Education 47 (2): 95–105. doi:10.1080/00220485.2016.1146102.

- Garman, T. 1979. “The Cognitive Consumer Education Knowledge of Prospective Teachers: A National Assessment.” Journal of Consumer Affairs 13 (1): 54–63. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1745-6606.1979.tb00127.x

- Garnett, R.F., and J. Reardon. 2012. “Pluralism in Economics Education.” In International Handbook on Teaching and Learning Economics, edited by Gail M. Hoyt, and KimMarie McGoldrick, 242–249. Cheltenham: Edward Elgar Publishing Limited.

- Gottesman, A.A., L. Ramrattan, and M. Szenberg. 2005. “Samuelson’s Economics: The Continuing Legacy.” Quarterly Journal of Austrian Economics 8 (2): 95–104. doi:10.1007/s12113-005-1024-3.

- Green, T.L. 2012. “Introductory Economics Textbooks: What Do They Teach About Sustainability?” International Journal of Pluralism and Economics Education 3 (2): 189–223. doi: https://doi.org/10.1504/IJPEE.2012.049198

- Grimes, P.W., M. Millea, and K. Thomas. 2010. “Testing the Economic Literacy of K–12 Teachers: A State-Wide Baseline Analysis.” American Secondary Education 38 (3): 4–20.

- Hansen, W.L., M.K. Salemi, and J.J. Siegfried. 2002. “Promoting Economic Literacy in the Introductory Economics Course, Use It or Lose It: Teaching Literacy in the Economics Principles Course.” American Economic Association Papers and Proceedings 92 (2): 463–472. doi: https://doi.org/10.1257/000282802320191813

- Henning, M.B., and T.A. Lucey. 2017. “Elementary Preservice Teachers’ and Teacher Educators’ Perceptions of Financial Literacy Education.” The Social Studies 108 (4): 163–173. doi:10.1080/00377996.2017.1343792.

- Hill, S. 2019. “The Difference Between Troublesome Knowledge and Threshold Concepts.” Studies in Higher Education, doi:10.1080/03075079.2019.1619679.

- Jappelli, T. 2010. “Economic Literacy: An International Comparison.” The Economic Journal 120 (548): F429–F451. doi:10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02397 doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0297.2010.02397.x

- Karunaratne, P.S.M., Y.A. Breyer, and L.N. Wood. 2016. “Transforming the Economics Curriculum by Integrating Threshold Concepts.” Education + Training 58 (5): 492–509. doi:10.1108/ET-02-2016-0041.

- Kristiansson, M. 2014. “Samhällskunskapsämnet och Dess ämnesmarkörer på Svensk Mellanstadium: Ett Osynligt ämne som Bistår Andra ämnen.” Nordidactica 2014 (1): 212–233.

- Krugman, P. 1999. The Accidental Theorist: And Other Dispatches From the Dismal Science. New York: W. W. Norton Company.

- Lambert, D. 2014. “Curriculum Thinking Capabilities and the Place of Geographical Knowledge in Schools.” Syakaika Kenkyu 81: 1–11.

- Löfström, J., and M. van den Berg. 2013. “Making Sense of the Financial Crisis in Economic Education: An Analysis of the Upper Secondary School Social Studies Teaching in Finland in the 2010s.” Journal of Social Science Education 12 (2): 53–68. doi:10.4119/UNIBI/jsse-v12-i2-111.

- Löw Beer, D. 2016. “How Should Prices Be Adjusted to Reflect the Environmental Harm of Products? Teacher Trainees’ Understanding of an Eco-Economic Phenomenon.” Zeitschrift für ökonomische Bildung 5 (1): 50–71.

- Lusardi, A., and O.S. Mitchell. 2011. “Financial Literacy Around the World: An Overview.” Journal of Pension Economics & Finance 10 (4): 497–508. doi:10.1017/S1474747211000448.

- Maier, H.M., and J. Nelson. 2007. Introducing Economics: A Critical Guide for Teaching. New York: Routledge.

- Maude, A. 2016. “What Might Powerful Geographical Knowledge Look Like?” Geography (Sheffield, England) 101 (2): 71–72.

- McKenzie, R.B. 1971. “An Exploratory Study of the Economic Understanding of Elementary School Teachers.” Journal of Economic Education 3 (1): 26–31. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.1971.10845337

- McKinney, C.W., K.C. McKinney, A.G. Larkins, A.C. Gilmore, and M.J. Ford. 1990. “Preservice Elementary Education Major’s Knowledge of Economics.” Journal of Social Studies Research 14 (2): 26–38.

- Meyer, J., and R. Land. 2003. “Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge: Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practicing Within the Disciplines.” In Improving Student Learning – Ten Years On, edited by Chris Rust, 412–424. Oxford: Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development.

- Miller, S.L., and P.J. VanFossen. 2008. “Recent Research on the Teaching and Learning of Pre-Collegiate Economics.” In Handbook of Research in Social Studies Education, edited by Linda Levstick, and Cynthia Tyson, 283–304. New York: Routledge.

- Modig, N. 2017. “Lärarstudenters Ekonomididaktiska Kunskapsutveckling i Samhällskunskap.” Nordidactica 2017 (3): 23–45.

- Nordgren, K. 2017. “Powerful Knowledge, Intercultural Learning and History Education.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 49 (5): 663–682. doi:10.1080/00220272.2017.1320430.

- O’Donnell, R.M. 2009. “Threshold Concepts and Their Relevance to Economics.” Paper presented at the 14th Annual Australasian Teaching Economics Conference, Queensland School of Economics and Finance, Queensland University of Technology, Brisbane.

- O’Donnell, R.M. 2010. A Critique of the Threshold Concept Hypothesis and an Application in Economics (No. 164). Sydney: Finance Discipline Group, UTS Business School, University of Technology.

- Quinlan, K.M., S. Male, C. Baillie, A. Stamboulis, J. Fill, and Z. Jaffer. 2013. “Methodological Challenges in Researching Threshold Concepts: A Comparative Analysis of Three Projects.” Higher Education 66 (5): 585–601. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-013-9623-y

- Rata, E. 2018. “Connecting Knowledge to Democracy.” In Knowledge, Curriculum and Equity: Social Realist Perspectives, edited by Brian Barrett, Ursula Hoadley, and John Morgan, 19–32. London and New York: Routledge.

- Raworth, K. 2017. Doughnut Economics. Seven Ways to Think Like a 21st-Century Economist. London: Random House.

- Reimann, N., and I. Jackson. 2006. “Threshold Concepts in Economics: A Case Study.” In Overcoming Barriers to Student Learning: Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge, edited by Janhf Meyer, and Ray Land, 115–133. London and New York: Routledge.

- Richardson, P.W. 2004. “Reading and Writing From Textbooks in Higher Education: A Case Study From Economics.” Studies in Higher Education 29 (4): 505–521. doi:10.1080/0307507042000236399.

- Samuelson, P., and W. Nordhaus. 2010. Economics, 19th (International) Edition. Boston: Irwin/McGraw-Hill.

- Scahill, E.M., and C. Melican. 2005. “The Preparation and Experience of Advanced Placement in Economics Instructors.” Journal of Economic Education 36 (1): 93–98. doi:10.3200/JECE.36.1.93-98.

- Shanahan, M. 2016. “Threshold Concepts in Economics.” Education + Training 58 (5): 510–520. doi:10.1108/ET-01-2016-0002.

- Shanahan, M.P., G. Foster, and J.F. Meyer. 2006. “Operationalizing a Threshold Concept in Economics: A Pilot Study Using Multiple Choice Questions on Opportunity Cost.” International Review of Economics 5 (2): 29–57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S1477-3880(15)30119-5

- Siegfried, J., and A. Krueger. 2010. Voluntary National Content Standards in Economics. 2nd ed. National Council for Economic Education. New York: United States of America. http://www.councilforeconed.org/wp/wpcontent/uploads/2012/03/voluntary-national-contentstandards-2010.pdf.

- Siegfried, J.J., and B.T. Meszaros. 1998. “Voluntary Economics Content Standards for American Schools: Rationale and Development.” Journal of Economic Education 29 (2): 139–149. doi:10.1080/00220489809597947.

- Skousen, M. 1997. “The Perseverance of Paul Samuelson’s Economics.” Journal of Economic Perspectives 11 (2): 137–152. doi:10.1257/jep.11.2.137.

- Sosin, K., J. Dick, and M.. Reiser. 1997. “Determinants of Achievement of Economic Concepts by Elementary School Students.” Journal of Economic Education 28 (2): 100–121. doi:10.1080/00220489709595912.

- Steiner, P. 2001. “The Sociology of Economic Knowledge.” European Journal of Social Theory 4 (4): 443–458. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/13684310122225253

- Stigler, G.J. 1983. “The Case, If Any, for Economic Literacy.” Journal of Economic Education 14 (3): 60–66. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/00220485.1983.10845027

- VanFossen, P.J. 1999. “The National Voluntary Content Standards in Economics.” ERIC Digest. Accessed 28 March 2019. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED428031.pdf.

- VanFossen, P.J. 2005. “Economic Concepts at the Core of Civic Education.” International Journal of Social Education 20 (2): 35–66.

- Walstad, W.B., and S. Allgood. 1999. “What Do College Seniors Know About Economics?” American Economic Review 89 (2): 350–354. doi: https://doi.org/10.1257/aer.89.2.350

- Walstad, W.B., and M. Watts. 2015. “Perspectives on Economics in the School Curriculum: Coursework, Content, and Research.” Journal of Economic Education 46 (3): 324–339. doi:10.1080/00220485.2015.1040185.

- Wobker, I., P. Kenning, M. Lehmann-Waffenschmidt, and G. Gigerenzer. 2014. “What do Consumers Know About the Economy? A Test of Minimal Economic Knowledge in Germany.” Journal für Verbraucherschutz und Lebensmittelsicherheit 9 (3): 231–242. doi:10.1007/s00003-014-0869-9.

- Young, M. 2008. “From Constructivism to Realism in the Sociology of the Curriculum.” Review of Research in Education 32 (1): 1–28. doi: https://doi.org/10.3102/0091732X07308969

- Young, M. 2009. “What are Schools for?” In Knowledge, Values and Educational Policy: A Critical Perspective, edited by Harry Daniels, Hugh Lauder, and Jill Porter, 10–18. New York: Routledge.

- Young, M. 2013a. “Overcoming the Crisis in Curriculum Theory: A Knowledge-Based Approach.” Journal of Curriculum Studies 45 (2): 101–118. doi:10.1080/00220272.2013.764505.

- Young, M. 2013b. “Powerful Knowledge: An Analytically Useful Concept or Just a Sexy Sounding Term? A Response to John Beck’s Powerful Knowledge, Esoteric Knowledge, Curriculum Knowledge.” Cambridge Journal of Education 43 (2): 195–198. doi.org/10.1080/0305764X.2013.776356.

- Young, M. 2014. “Powerful Knowledge as a Curriculum Principle.” In Knowledge and the Future School: Curriculum and Social Justice, edited by Michael Young, David Lambert, Carolyn Roberts, and Martin Roberts, 65–88. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Appendix 1

Survey about concepts in economics

In primary and upper secondary schools, students experience their first encounter with scientific economics vis-à-vis their everyday understanding of economics. However, according to economics experts, what scientific economic knowledge has the greatest significance for students’ ability to understand and solve economic problems in everyday life? Are there scientific economic concepts that are of higher importance than others and thus help people understand and manage economics better in their daily lives as individuals and citizens?

With this survey, we want to investigate whether there are concepts that are considered particularly important to master according to economics experts.

Contacts:

Niclas Modig, lecturer educational work, Karlstad University

[email protected], Tel: (+46) (0)54-700 25 39, (0)73-072 39 23

Niklas Jakobsson, associate professor in economics, Karlstad University

[email protected], Tel: (+46) (0)70-393 90 09

Martin Kristiansson, senior lecturer in educational science, Karlstad University

[email protected], Tel: (+46) (0)54-700 14 05

1. In what decade were you born?

2. Sex

3. What is your highest academic title / title of service?

4. What is your main focus in economics?

5. What are your main research areas?

6. What are your main areas of teaching?

7. How much of your work time, on average, has been devoted to teaching over the last five years? Answer in percentage.

8. At what level have you mainly taught over the past five years?

9. Which courses have you mainly taught over the last five years?

10. What do you consider the most important concepts for an individual to understand and manage economics?

11. What do you consider the most important concepts for a citizen to understand and manage economics?

12. Below, you can comment freely on the above questions and / or other matters relating to the survey.

Thank you for your participation.