ABSTRACT

Boards in higher education organizations (HEOs) play multiple roles. While they govern, boards are also expected to embed HEOs in society. Indeed, recent higher education reforms in Europe have emphasized the embedding role of HEO boards more than their governing role. But, although these reforms are widespread, we still know little about the ways in which boards are affected by ambitions of embedding HEOs. The aim of our paper is to explore how such ambitions are expressed through HEO board nominations and compositions. We address this aim by turning to Sweden, whose higher education system has, during the past three decades, undergone recurrent reforms that emphasize the embedding role of boards at public HEOs. Our study builds on a longitudinal dataset of external HEO board members’ positions, employers, and simultaneous board seats, collected for 1998, 2007, and 2016 so as to accompany Swedish reforms. We find that external board members, over time, embedded HEOs in expanding and sprawling networks of ties to organizations from the public, private, and civil society sectors. Our findings push the literature beyond its focus on private sector ties by showing how governmental reforms lead HEOs to embed among public and civil society organizations as well.

Introduction

Governing boards in higher education organizations (HEOs) play multiple roles. As the term suggests, these boards are expected to govern. Indeed, HEO boards usually comprise the highest decision-making authority. But governing boards are also expected to embed HEOs in society. Through board members, HEOs will allegedly reach, interact with, and gain insights from a broad range of constituencies. Tellingly, several recent higher education reforms in Europe emphasize the embedding role of boards more than their governing role (cf. De Boer and File Citation2009).

While such reforms are widespread, we know little about the ways in which ambitions of embedding HEOs throughout European societies impact upon the nominations to and compositions of governing boards. An important reason behind this knowledge lacuna is that the US-centered literature on HEO boards remains relatively silent when it comes to embedding. In one salient stream of literature, boards are regularly portrayed as organs that not only govern, but also buffer HEOs from political interests (Berdahl Citation1990; Pusser Citation2003). Moreover, in another prominent literature strand, HEO boards are pictured as governing bodies that additionally serve to channel business interests into HEOs (Barringer and Slaughter Citation2016; Barringer, Slaughter, and Taylor Citation2019; Mathies and Slaughter Citation2013).

We do not dispute that HEO boards function as buffers or channels. However, considering the ambitions behind recent higher education reforms across Europe, our argument is that we also need to enhance our understanding of governing boards as organs through which HEOs embed in (and not distance from) society. We push this argument with Francisco Ramirez’s (Citation2006, Citation2020) theoretical notion of the embedded university ideal because it fittingly describes pressures faced by HEOs to become integral parts and reflections of changing societies. The aim of our paper is thus to explore how ambitions of embedding HEOs are expressed through board nominations and compositions.

To explore these ambitions and their impact, we turn toward Sweden, where a series of reforms during the past three decades have reorganized Swedish HEOs into more corporate-like actors (Brunsson and Sahlin-Andersson Citation2000; Wedlin and Pallas Citation2017). Sweden’s recurrent higher education reforms follow patterns that are similar to those found in many countries across the world, where managerial governance has been strengthened at the expense of collegial governance (for international overviews, see Krücken and Meier Citation2006; Maasen and Olsen Citation2007; Musselin Citation2018). However, throughout its reforms, the Swedish government has placed particular emphasis on board nominations and compositions, motivating the associated changes with an alleged need for new influences and perspectives that should be gained by increasing and deepening the connections between HEOs and a changing society. In light of these reforms, we pose the following research questions: How do HEO governing boards embed in society? Which societal sectors do board members connect HEOs to? And what patterns of embedding emerge among HEO board interlocks to other organizations?

Our empirical study is grounded in a hand-collected dataset that contains ample information on external board members at Swedish HEOs, including these members’ employers, positions, and simultaneous board seats. We gathered data at three temporal points during the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s to accompany the unfolding of recent higher education reforms in Sweden. Building on this dataset, we follow HEO board embedding patterns in a longitudinal analysis of how and where Swedish HEOs have connected to society throughout the past three decades. We analyze these patterns against a backdrop of recurring changes to nomination and composition procedures for HEO boards that, by extensions, shows the ways in which Sweden’s government fueled this embedding. Our study, in sum, highlights the dynamics and outcomes of an additional, but hitherto largely neglected, role of governing boards as societal embedders.

The remainder of our paper is organized as follows. After this introduction, we continue with a theoretical orientation. We describe our empirical setting in the next step. Then, we move on to a methods section. We subsequently report our findings. To conclude, we discuss contributions, acknowledge limitations, and suggest future research avenues.

Theoretical orientation

Much literature has focused on HEO boards as governing bodies. Researchers have thus mapped the demographics of board members (Jones and Skolnik Citation1997; Kerr and Gade Citation1989), offered recommendations for the performance of board duties (Ewell Citation2006; Scott Citation2018), and highlighted the increasingly strengthened governing role of boards (Veiga, Magalhaes, and Amaral Citation2015). Two additional board roles are, however, proposed throughout the literature. These roles portray boards as buffers from or channels for certain interests.

Boards as political buffers or business channels

According to the ‘institutional autonomy’ stream, boards can be seen as governing organs through which HEOs attempt to buffer from political interests (Berdahl Citation1990; Pusser Citation2003). Focusing on public and private North American universities, institutional autonomy researchers picture HEO boards as bodies that handle a diverse set of pressures from governmental organizations.

In contrast, within the ‘corporate influence’ strand, boards are portrayed as organs that not only serve to govern, but also to channel business interests into HEOs (Barringer and Slaughter Citation2016; Barringer, Slaughter, and Taylor Citation2019; Mathies and Slaughter Citation2013). While they show how HEO boards may occasionally be mobilized in search of resources from private sector organizations, corporate influence scholars suggest that the most important additional role of boards is to function as meeting points for business and higher education agendas at US universities.

The corporate influence stream, arguably the most developed when it comes to boards in HEOs, builds on two theoretical underpinnings. First, corporate influence researchers rely on the notion of academic capitalism (Slaughter and Leslie Citation1997; Slaughter and Rhoades Citation2004) to picture HEO board members as ‘elites who act in their own material interests rather than following academic norms or the university community’s expectations’ (Barringer and Slaughter Citation2016, 153). Such board members, it is stressed, imply that higher education agendas are prone to be influenced by and become aligned with business interests. Second, the corporate influence strand also relies on the theoretical notion of interlocking directorates (Galaskiewicz Citation1985; Mizruchi Citation1996). Transposing this notion into HEOs, Slaughter and colleagues find that private universities and private sector organizations in North America are extensively interlocked through shared board members. Such findings are, by extension, taken as evidence for the dynamics of academic capitalism on HEO boards. As board members ‘interact with each other multiple times over the course of a year on corporate and university boards’, these members come to develop and exchange ideas about ‘how corporations can interact profitably with universities’ (Barringer and Slaughter Citation2016, 154).

Our intent is not to argue against extant literature. However, we think many findings in this literature may be driven by empirical characteristics that are rather idiosyncratic to the US higher education system, including its relatively low degree of governmental involvement and its comparatively large presence of private universities. These characteristics are perhaps most apparent in the corporate influence stream, where a decentralized system seems to be an important precondition for the entry of business interests into North American HEOs. We thus suggest that our current understanding about the roles of HEO governing boards can be advanced by resorting to alternative theoretical notions and empirical settings.

Boards as societal embedders

European higher education reforms regularly move beyond the governing role of boards, thereby also picturing them as bodies through which HEOs can be embedded in society. In these reforms, HEO boards are often seen as organs that may fulfill governmental ambitions to increase and deepen the connections between HEOs and a broad range of constituencies. To theorize this additional role of boards, we rely on Ramirez’s (Citation2006, Citation2020) notion of the embedded university ideal.

Ramirez portrays the embedded university as an HEO that is expected to reject quasi-mythical pictures of ivory-towered scholars who seek knowledge for its own sake in closed and exclusive communities. The ongoing worldwide expansion of higher education is accompanied by public calls for HEOs that provide accessibility and encourage diversity on multiple fronts, ranging from students and course curricula to academics and employment criteria (Meyer and Schofer Citation2005). As such, the embedded university is expected to provide open and inclusive knowledge communities, which embrace hopeful visions of justice and democracy by welcoming a broad range of constituencies. Ultimately, ‘the message [behind this ideal] is’, according to Ramirez (Citation2020, 131), ‘that the boundaries between university and society should be more permeable’.

Several studies show that expectations about openness and inclusiveness in higher education may alter HEOs internally. For instance, Ramirez (Citation2006) argues that the growth of identity-focused courses, such as African and women studies, has largely unfolded in parallel with the rise of visions about justice and democracy throughout the US higher education system. Moreover, Kwak, Gavrila, and Ramirez (Citation2019) posit that, along with increasing public calls for inclusiveness, diversity offices have successively become core HEO units in many systems across the world. Ramirez (Citation2020) argues that a similar logic underlies the exponential growth of technology transfer offices, which thus constitute an important expression of the openness HEOs are expected to demonstrate toward society.

Building on these studies, we posit that public calls for openness and inclusiveness in higher education may alter the nomination and composition procedures of HEO governing boards as well. While Ramirez and colleagues have examined the internal creation of courses and expansion of units, Granovetter’s (Citation1985) theoretical notion of embeddedness indicates that it is also possible to study how the embedded university ideal is expressed through the external ties of HEOs. We argue that the creation of new ties lies at the core of several higher education reforms in Europe, as governments have introduced procedures to nominate representatives from different societal sectors for external HEO board memberships (De Boer and File Citation2009). These procedures allow us to propose that the resulting compositions of boards can be approached as expressions of attempts at embedding HEOs in society.

Methods

We leverage Sweden’s higher education system as our empirical setting to explore the embedding role of HEO boards. In choosing this setting, our intent is to develop new insights by venturing beyond the US-centric literature on boards. While the North American system features a relatively low degree of governmental involvement and a comparatively large presence of private universities, the Swedish higher education system is almost entirely controlled by the government. Indeed, the great majority of HEOs in Sweden are constituted as public agencies under the government. Entering 2020, there were thus 34 public (i.e. government-operated) and three private (i.e. foundation-operated) HEOs in the Swedish system. These 34 HEOs consisted of two broad types: universities and university colleges.

Research design

Our empirical study revolves around a novel dataset that contains longitudinal information on external HEO board members’ positions, employers, and simultaneous board seats beyond the focal HEOs. To construct this dataset, we sampled all 774 external board members at all 30–35 public HEOs in Sweden during 1998, 2007, and 2016.

Two considerations guided our sampling. First, we focused on public HEOs as they constitute a great majority in the organizational landscape of Swedish higher education. These HEOs also feature boards that are comparable on important dimensions, such as total seat numbers and membership period lengths.

Second, we concentrated on 1998, 2007, and 2016 as these years are situated within three decades that encompassed recurrent reforms to boards at public HEOs in Sweden. While the Swedish government launched a broad higher education reform already in 1992, the embedding role of boards was successively shaped and concretized through further reforms during the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. These decades thus become a relevant longitudinal time span during which to study the embedding of Swedish HEOs in society.

Data collection strategy

We designated three specific data collection points (January 1, 1998; May 1, 2007; and May 1, 2016). Each of them represented the start of a board membership period at public HEOs in Sweden. For every collection point, we gathered information on all external board members’ employers, positions, and simultaneous seats. We regard this data as different instantiations of ties that connected the HEOs in focus to other organizations.

HEO annual reports constituted our main data source. Annual reports were occasionally available as digital content on websites, but predominantly as analog material in archives. We complemented this information with data from CVs, newspapers, press releases, and personal profiles. Although we have complete data on the employers and positions of external board members, our information on simultaneous seats is laden with certain limitations. For transparency reasons, all board members at public HEOs in Sweden are required to declare seats that may involve financial compensation or interest. At first sight, this requirement suggests that board seats at business firms could be overrepresented in our data. However, HEO board members may also declare simultaneous seats at any other organizations. We repeatedly observed across annual reports that external board members voluntarily declared many more seats than required. As such, even though it may not be all-covering, our data on external members’ employers, positions, and simultaneous board seats give a comprehensive picture of how and where Swedish HEOs embedded during our focal time span.

Data analysis approach

We used a mix of coding procedures and social network techniques to examine our data. To begin, we coded the employers, positions, and simultaneous seats of all external HEO board members. For each year in focus, we classified external board members’ employers as ties to public, private, or civil society organizations. In order to learn more about employments, we also coded the positions of external members utilizing the Swedish Standard Classification of Occupations (Swe. Standard för svensk yrkesklassificering) (Statistics Sweden Citation2020a). Finally, for each focal year, we coded external HEO board members’ simultaneous seats as ties to public, private, or civil society organizations.

Throughout our data, public HEOs could not be directly connected to one another because Swedish regulations prohibit external board members from simultaneously holding seats at several HEOs. Public HEOs could, however, be connected to each other indirectly. To identify patterns among these direct and indirect ties, social network techniques became particularly useful. Our approach was to produce matrices that, for each year in focus, connected all external board members and all organizations where these members simultaneously held seats. In the three resulting matrices, HEOs were connected to other organizations through one-step direct interlocks if any external HEO board members held simultaneous seats at other organizations. HEOs were, in these same matrices, also connected to one another through two-step indirect interlocks if any of the respective external HEO board members held simultaneous seats at the same organizations (cf. Galaskiewicz Citation1985; Mizruchi Citation1996). Altogether, the various direct and indirect interlocks formed intra-connected subgroups known as components (Hanneman and Riddle Citation2011).

Our social network analyses were facilitated by UCINET 6 software. We used this software to derive descriptive statistics; to transform our matrices into graphs; and to calculate density and fragmentation measures as indications of network cohesiveness generated by direct and indirect interlocks (see Borgatti, Everett, and Johnson Citation2013 for more on such cohesiveness).

Findings

We analyzed our data against a backdrop of governmental reforms to the nomination and composition procedures for HEO boards in Sweden. Thus, we begin by describing these reforms, before moving on to the longitudinal findings from our study of external board members’ employers, positions, and simultaneous seats.

Swedish higher education reforms over three decades

The embedding role of Swedish HEO boards has been constructed through recurrent changes to the Higher Education Law (SFS 1992: 1434) during the past three decades. Our starting point is 1992 because this year marked the first of several reforms aimed at increasing and deepening the connections between public HEOs and a changing society. Sweden’s government hoped that such connections would infuse new influences and perspectives into the higher education system. Subsequent reforms followed in 1997, 2007, 2011, and 2016. We note that, between 1992 and 2007, the reforms prescribed extensive changes to the overall governance and organization of HEOs. Throughout these years, changes to the nomination and composition procedures for HEO boards were thus part of broad reforms. The 2011 and 2016 reforms specifically involved revisions to board nomination procedures, however.

Boards at Swedish HEOs are, on the one hand, composed of two internal groups (student representatives and faculty-appointed members) and, on the other hand, an external group (members appointed by the government). We focus on reforms concerning external board members. In 1992, a newly elected right-wing government shifted the majority of HEO board seats from faculty-appointed internal members to government-appointed external members (prop. 1992/93:1). Further changes were launched in 1997. Up until then, vice chancellors had chaired boards. Now, chairs were also switched to government-appointed external members (prop. 1996/97: 141).

The stated rationale for these first two reforms was a significant expansion of higher education in Sweden, which had unfolded from the mid-1970s and onward, but now placed new demands on HEOs. Allegedly, as it entered the 1990s, this expansion should not only be focused on student numbers, but also on issues related to ‘equality’ (prop. 1996/97: 141, 15) and ‘cooperation with the surrounding society’ (prop. 1996/97: 141, 18). While the 1992 and 1997 reforms acknowledged that HEOs required collegial autonomy, governmental control was also needed in light of the ‘increasingly important’ (prop. 1992/93:1, 62) role played by HEO boards. External members, in general, and politicians, in particular, could contribute with ‘impulses from societal life’ that HEOs ‘cannot afford to bypass’ (prop. 1996/97: 141, 19).

Initially, these HEO board changes were met with certain criticism from the academic community, but new procedures would soon come to be acccepted in most circles. The limited criticism can be explained by the fact that the board changes were, as we hinted at before, part of broad higher education reforms. Those changes that affected boards attracted much less attention than other changes to the overall governance and organization of HEOs (HSV Citation1998).

Under another right-wing government, earlier changes to HEO boards were partly reversed through new reforms in 2007. First, in the name of institutional and collegial autonomy, HEOs were now allowed to choose whether they wanted their vice-chancellor or an external member as board chair. Second, and also in the name of autonomy, the Swedish government gave HEOs the mandate to nominate all external board members (prop. 2006/07: 43). The overarching argument for these changes was a desire to ‘depoliticize’ (prop. 2006/07: 43, 1) HEO boards. Up until then, when the government both nominated and appointed external members, there was a customary practice of placing at least two politicians on each HEO board. While connections to society clearly remained important, Sweden’s government now aimed to decrease the number of politicians on boards, thus encouraging nominations from HEOs for individuals with knowledge and experience of issues that specifically affected the higher education system. Although it was stressed that all nominations would be considered, the government retained the final decision to appoint external HEO board members (prop. 2006/07: 43). These appointments were, in practice, formal approvals of nominations.

Entering 2011, increasing criticism was being directed at the prevailing procedures through which vice chancellors reported activities and nominated external board members (including the chair) to the same HEO boards. In order to address this criticism, previous changes were slightly modified. Now, all external board members at HEOs would be nominated by government-appointed, three-person committees. These committees were set to consist of a student, the local county governor, and an individual with knowledge and experience of the HEO in question (prop. 2011/12: 133). Governors would not only provide knowledge and experience of societal issues in the environments of HEOs, but they would also ‘represent an overarching state interest’ (prop. 2011/12: 133, 19) As before, the appointed external board members were formally approved by the Swedish government (prop. 2011/12: 133).

In 2016, the nomination committees were slightly modified once again. They now encompassed an individual who would represent state interests, plus an individual with knowledge and experience of, but without a top management position at, the focal HEO. Based on suggestions from the respective HEOs, all nomination committees were appointed by the government. Moreover, after these commitees had submitted their nominations, the government also appointed all external board members (prop 2015/16: 131).

Although many changes partly reversed one another throughout Sweden’s recurrent reforms, we highlight two enduring developments. First, since 1992, external members have constituted a majority on public HEO boards. Second, as procedures were changed, the government moved the nomination of external board members closer to the focal HEOs. Our following analysis shows how the embedding ambitions stated in Swedish reforms translated into HEO board compositions and interlocks that encompassed sprawling ties to public, private, and civil society organizations.

The employers and positions of external board members

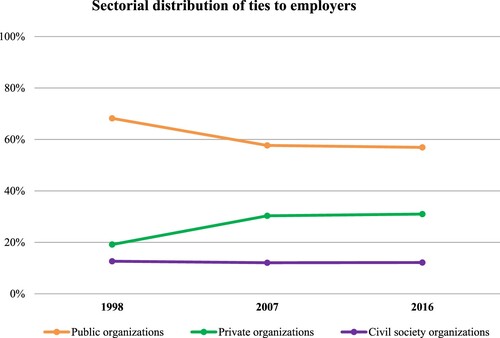

We start by examining the sectorial distribution of ties between public HEOs and external board members’ employers over time.Footnote1 displays the sectorial distribution of these members’ employers.

Figure 1. Sectorial distribution of ties to employers among external board members of Swedish public higher education organizations, 1998–2016.

Over time, a majority of external HEO board members were employed by public sector organizations, such as government agencies, county councils, and municipal departments. In 1998, organizations like these employed almost 70 percent of external board members. Although that proportion subsequently declined, nearly 60 percent of external members were employed by public organizations in 2007 and 2016. Private sector organizations employed close to 20 percent of external HEO board members in 1998. Among these private organizations, we find some of the largest Swedish multinational corporations. Regional and local firms were also represented here. The proportion of private sector organizations rose afterward, as they employed just above 30 percent of external board members in 2007 and 2016. Finally, it was evident that civil society organizations employed a minority of external members. For each focal year, approximately 15 percent of external HEO board members were employed in the civil sector. Employers from this sector included trade unions, sports confederations, and humanitarian relief organizations. When splitting our sample of public HEOs into universities and university colleges, we find that both HEO types largely followed the same longitudinal embedding patterns in terms of external board members’ employers.

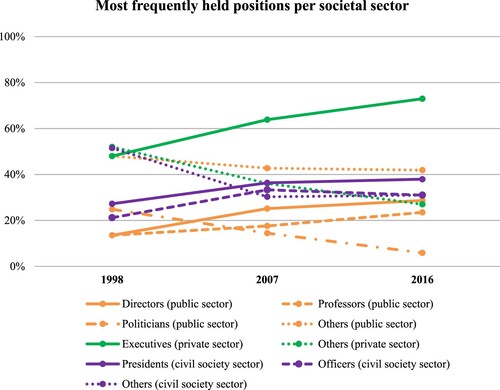

As employees in public, private, or civil society organizations, some positions were clearly more common than others among external board members. depicts the most frequently held positions for external members per societal sector over time. To identify patterns, we focus on positions that at least five percent of these members held in 1998, 2007, and 2016.

Figure 2. Most frequently held positions per societal sector among external board members of Swedish public higher education organizations, 1998–2016.

Note: Within each societal sector, the different positions add up to 100 percent every year. The three instances of ‘Others’ contain the positions that less than five percent of external board members per respective sector held in 1998, 2007, and 2016. These instances of Others include a broad range of positions, such as judges, ambassadors, and school principals for the public sector; journalists, film producers, and financial analysts for the private sector; and administrators, legal advisors, and project leaders for the civil society sector.

During our studied time span, the most common positions among external HEO board members employed in the public sector were directors at government agencies or municipal departments, university professors, and politicians. While the proportion of directors and professors increased over time, that of politicians decreased. Among external board members employed in the private sector, the most frequently held positions were undoubtedly as executives at Sweden-based multinational corporations or regional firms. Not only were executives the most common among external members employed in the private sector, but the proportion of executives also grew for each focal year. Lastly, the most frequently held positions among external HEO board members employed in the civil society sector were as union presidents and humanitarian affairs officers. While the proportion of presidents increased marginally over time, that of officers peaked in 2007. There are certain differences between universities and university colleges as seen through the most common positions among external board members. These differences primarily concern geographical reach. The extent of governmental agency directors and corporate executives that acted as board members at universities infused their embedding patterns with national and multinational dimensions. University colleges, in comparison, displayed more regional patterns. This was largely due to the frequency of municipal department directors and local firm executives on university college boards.

The simultaneous seats of external board members

External board members’ employers and positions provided us with one way of understanding the embedding patterns of Swedish public HEOs. Now, we add another angle to these patterns by probing the ties between HEOs and other organizations where external board members held simultaneous seats.

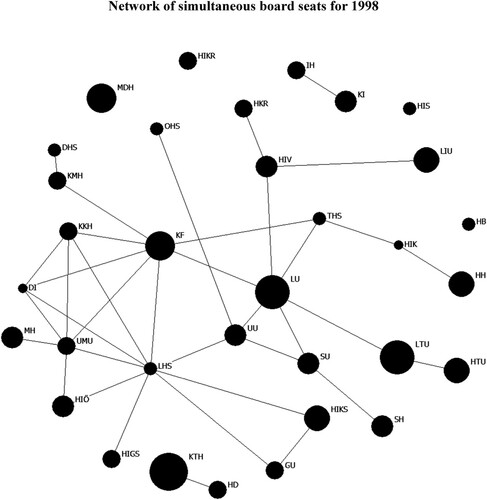

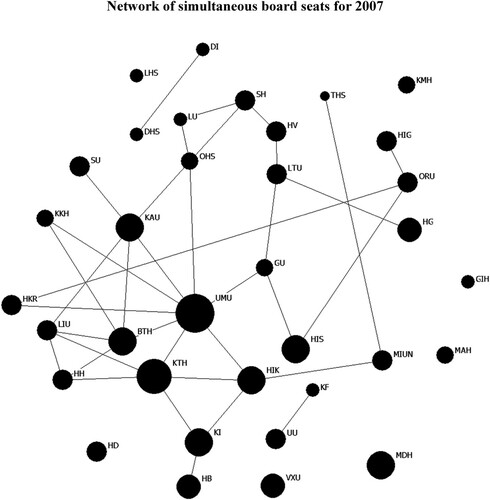

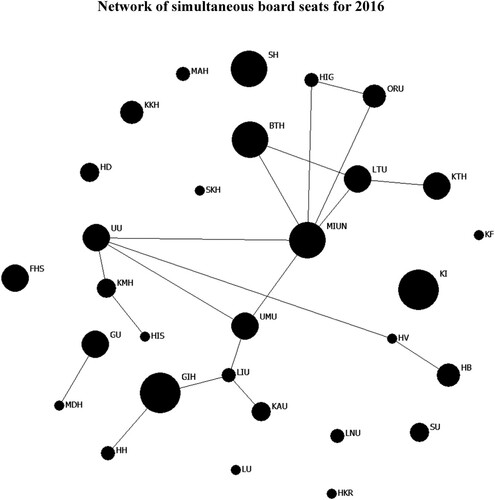

feature graphs that display the respective networks of ties for 1998, 2007, and 2016.Footnote2 Black circles represent direct interlocks between HEOs and other organizations. These circles are differently sized to denote the total number of ties for each HEO. Sizes come in intervals of 5, where the smallest circles represent 1–5 ties, while the largest circles denote 41–45 ties. That said, black lines represent indirect interlocks between HEOs.

Figure 3. Network of direct and indirect interlocks based on simultaneous seats held by external board members of Swedish public higher education organizations, 1998.

Note: A list of acronyms for , 4, and 5 is available upon request from the corresponding author.

Figure 4. Network of direct and indirect interlocks based on simultaneous seats held by external board members of Swedish public higher education organizations, 2007.

Figure 5. Network of direct and indirect interlocks based on simultaneous seats held by external board members of Swedish public higher education organizations, 2016.

We derive two sets of observations from our network graphs. First, over time, the average number of ties created by external HEO board members’ simultaneous seats grew, increasing from roughly 16 ties to approximately 21 ties throughout our focal years. Looking at the sectorial distribution of these ties, private sector organizations were evidently the most prominent. Private organizations comprised close to 40 percent of all ties in 1998. That proportion rose beyond 45 percent in 2007, eventually reaching almost 55 percent by 2016. As for public sector organizations, they constituted close to 40 percent of all ties in 1998. By 2007, that proportion fell under 35 percent, before ending just below 25 percent in 2016. Civil society organizations comprised approximately 20 percent of all ties for each year in focus.

Second, throughout our studied time span, the majority of external board members’ simultaneous seats created direct interlocks, which connected HEOs to a broad range of other organizations than HEOs. These other organizations included book publishers in the private sector, research funders in the public sector, and think tanks in the civil society sector, among others. The large number of direct interlocks situated a growing proportion of HEOs in components that solely connected these HEOs to other organizations than HEOs. That proportion shifted from approximately 10 percent to roughly 40 percent between our focal years. As an immediate consequence of these large direct interlock numbers, only a minority of external board members’ simultaneous seats created indirect interlocks that connected HEOs to other HEOs. To take a representative example, in 2007, University of Gothenburg (Swe. Göteborgs universitet [GU]) and Umeå University (Swe. Umeå universitet [UMU]) were indirectly connected to each other as external HEO board members at both GU and UMU simultaneously held seats at a Sweden-based, multinational construction equipment manufacturer. The small number of indirect interlocks situated a decreasing proportion of HEOs in components that connected these HEOs to other HEOs. That proportion shifted from roughly 90 percent to approximately 60 percent over time.

The interplay between direct and indirect interlocks is reflected in our network cohesiveness measures, which evince how density decreased and fragmentation increased sequentially across the 1998, 2007, and 2016 networks. These measures indicate that the embedding patterns of HEOs ramified over time to encompass a growing extent of organizations situated beyond the higher education system. We note that both universities and university colleges fueled this ramification, although they did so to different degrees. University colleges, on average, exhibited more direct interlocks than universities.Footnote3 This means that university colleges, vis-à-vis universities, were more connected to organizations located outside of the higher education system. As a consequence, university colleges also held more peripheral positions than universities in each of our networks.

summarizes the ties created by external HEO board members’ simultaneous seats.

Table 1. Statistics and measures for networks based on simultaneous seats held by external board members of Swedish public higher education organizations, 1998-2016.

Conclusions

In this paper, we explored the embedding role of HEO governing boards. Our reading of recurrent reforms in Sweden revealed governmental ambitions for opening up HEOs to increased and deepened connections with society. These reforms changed the nomination and composition procedures for HEO boards, introducing a majority of external members. With these procedures, boards were constructed to embed HEOs throughout Swedish society. We created a longitudinal dataset to analyze the ways that the government’s embedding ambitions subsequently played out in terms of HEO board compositions and interlocks. Below, we discuss how our findings contribute to the literature on governing boards in HEOs.

Connected with the private sector …

Our first contribution lies in confirming portions of the US-centered literature with findings from an empirical setting that differs considerably from the North American higher education system. In line with this literature, we also found extensive ties between HEOs and private sector organizations throughout the Swedish setting.

Private sector ties were notable among external HEO board members’ employers. After governmental reforms to Sweden’s higher education system in the 1990s, the proportion of external board members employed by private organizations increased. In 2007 and 2016, more than a third of all employer-mediated ties involved private sector organizations. And, during these latter years, two-thirds or more of all external members with employment in the private sector were executives at multinational corporations or regional firms.

Findings from the corporate influence strand suggest that ties between HEOs and private organizations are mainly driven by business interests. That research is based on studies of the decentralized US higher education system, characterized by a relatively low degree of governmental involvement and a comparatively large presence of private universities. We argue that the extensive presence of executives from private sector organizations on HEO boards in Sweden may have been driven by aspects beyond business interests. Our argumentation is supported by the expectations for openness and inclusiveness that are associated with Ramirez’s theoretical notion of the embedded university ideal, as well as by the contents of governmental reforms seeking to infuse impulses from society into Swedish HEOs throughout the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s. These reforms were, however, not only motivated by a search for impulses from society. As in other parts of Europe and beyond (Broucker and De Wit Citation2015), Sweden’s higher education reforms were also influenced by organization ideals from the private sector (Engwall Citation2016). We thus note a longitudinal pattern running through our findings, consisting of an increase in executives from the private sector, along with a more general increase in external HEO board members holding executive positions across all sectors, thereby including public sector directors and civil society sector presidents too.

… and governed as public agencies

Our second contribution lies in extending the US-centered literature beyond its focus on ties between HEOs and private sector organizations. We observed that Swedish HEOs not only connected to private organizations, but also to a broad range of organizations from the public and civil society sector.

HEOs in Sweden have a long tradition of governmental control. Most of them are constituted as public agencies under the government. In this respect, the clear dominance of public sector employers among external board members confirmed the identities of HEOs as public agencies. While organizations from the civil society sector were certainly found among board members’ employers, for each focal year, approximately two-thirds of all employer-mediated ties involved public organizations. These ties primarily comprised directors at governmental agencies and municipal departments. We note that politicians constituted a notable proportion of those employer-mediated ties that involved public organizations in 1998. However, the proportion of politicians on HEO boards decreased afterward, following a development that was aligned with ambitions to depoliticize boards, most clearly stated in the 2007 reform. Our findings demonstrate that this decreasing proportion of politicians largely seemed to be replaced with an increasing proportion of public sector executives, such as agency or department directors.

Although it is difficult to say anything conclusive about how the resulting employer-mediated embedding patterns reflected broader patterns in Swedish society, we gauge this question tentatively by comparing our findings with other indicators of sectorial distribution. For instance, throughout the 1990s, 2000s, and 2010s, 60–70 percent of Sweden’s workforce was employed in the private sector, while 30–40 percent was employed in the public sector. Only a small percentage of the Swedish workforce was employed in the civil society sector (Statistics Sweden Citation2020b). Seen in this light, the sectorial distribution of external HEO board members’ employers (i.e. 60–70 percent public; 20–30 percent private; and ∼15 percent civil society) did not align very well with the Swedish workforce distribution. Indeed, the respective distributions were turned upside down, as the percentage of external board members employed in the public sector was the same as the percentage of Sweden’s workforce employed in the private sector.

Expanded and fragmented networks

We could, as mentioned earlier, see growing ties between Swedish HEOs and private sector organizations in terms of external board members’ employers. These ties were, however, present to an even greater extent in our social network analyses of simultaneous board seats.

The proportion of simultaneous seats that connected HEOs to private sector organizations increased over time. Our data show that seat-mediated ties to the private sector comprised an evident majority in 2007 and 2016. In parallel with that growth, the average number of seat-mediated ties per HEO also increased. We could notice how this growing average translated into networks of simultaneous board seats that became less dense and, thus, more fragmented during our studied time span. Changes in density and fragmentation were fueled by a decreasing proportion of indirect interlocks (i.e. less HEOs were connected to other HEOs) and an increasing proportion of direct interlocks (i.e. more HEOs were only connected to other organizations than HEOs). When we juxtapose these changes against the embedding ambitions behind Sweden’s reforms to nomination and composition procedures for HEO governing boards, our data suggest that such reforms embedded HEOs in society by creating expanding and sprawling networks, which stretched far beyond the higher education system.

Limitations and future research avenues

Our paper contains limitations that must be acknowledged. We have already highlighted that our data from annual reports could be characterized by shortcomings. Here, we acknowledge further limitations, which also serve as avenues for future research on governing boards in HEOs.

First, our database only contains snapshot-like information on the employers, positions, and simultaneous seats of external HEO board members for the three focal years that we studied. As such, we could not analyze how the societal ties created through boards were influenced by, and perhaps followed from, external members’ education and career backgrounds. For instance, how many external board members at Swedish HEOs were alumni? Or, to what extent did the career trajectories of individual board members span several societal sectors? Questions like these inevitably require biographical data. Such data would complement our focus on reforms and open up for further contextualization of board-mediated ties between HEOs and society in Sweden.

Second, while we provided a general picture of Swedish public HEOs as one group, it is also important to consider that certain embedding patterns differed across HEO types. Divergences between universities and university colleges, which were noticeable in terms of external board members’ positions and simultaneous seats, created different geographical and organizational embedding patterns. We argue that there is much merit in looking further into such differences to analyze their potential implications for the governance of HEOs.

Third, throughout this paper, we explored the embedding role of HEO governing boards. Embedding is, however, not their only additional role. Previous literature suggests that boards in HEOs also function as buffers from and channels for certain interests. Qualitative methods could be used to examine the ways in which board members and constituencies perceive and navigate the interplays and trade-offs between the buffering, channeling, and embedding roles. How are these multiple roles understood and approached? Research like this holds great potential to enhance our knowledge of the dynamic relations between HEO boards and wider changes in higher education governance.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 Due to reforms, there were 261 external board members in 1998; 274 in 2007; and 239 in 2016.

2 Due to foundings and mergers, there were 33 HEOs in 1998; 35 in 2007; and 30 in 2016.

3 Indeed, for each year we studied, university colleges were overrepresented among those HEOs that only displayed direct interlocks.

References

- Barringer, S. N., and S. Slaughter. 2016. “University Trustees and the Entrepreneurial University: Inner Circles, Interlocks, and Exchanges.” In Higher Education, Stratification, and Workforce Development: Competitive Advantage in Europe, the US, and Canada, edited by Sheila Slaughter, and Barrett J. Taylor, 151–171. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Barringer, S. N., S. Slaughter, and B. J. Taylor. 2019. “Trustees in Turbulent Times: External Affiliations and Stratification Among US Research Universities, 1975–2015.” The Journal of Higher Education 90 (1): 1–26.

- Berdahl, R. O. 1990. “Public Universities and State Governments: Is the Tension Benign?” Educational Record 71 (1): 138–142.

- Borgatti, S. P., M. G. Everett, and J. C. Johnson. 2013. Analyzing Social Networks. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Broucker, B., and K. De Wit. 2015. “New Public Management in Higher Education.” In The Palgrave International Handbook of Higher Education Policy and Governance, edited by Jeroen Huisman, Harry De Boer, David D. Dill, and Manuel Souto-Otero, 57–75. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Brunsson, N., and K. Sahlin-Andersson. 2000. “Constructing Organizations: The Example of Public Sector Reforms.” Organization Studies 21 (4): 721–746.

- De Boer, H., and J. File. 2009. Higher Education Governance Reforms Across Europe. Twente: Center for Higher Education Studies.

- Engwall, L. 2016. Universitet Under Uppsikt. Stockholm: Dialogos.

- Ewell, P. T. 2006. Making the Grade. How Boards Can Ensure Academic Quality. Washington, DC: Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges.

- Galaskiewicz, J. 1985. “Interorganizational Relations.” Annual Review of Sociology 11: 281–304.

- Granovetter, M. 1985. “Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness.” American Journal of Sociology 91 (3): 481–510.

- Hanneman, R. A., and M. Riddle. 2011. “Concepts and Measures for Basic Social Network Analysis.” In The Sage Handbook of Social Network Analysis, edited by John Scott, and Peter J. Carrington, 340–369. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- HSV. 1998. Att leda universitet och högskolor. En uppföljning och analys av styrelsereformen 1998. Stockholm: Högskoleverket.

- Jones, G. A., and L. Skolnik. 1997. “Governing Boards in Canadian Universities.” The Review of Higher Education 20 (3): 277–295.

- Kerr, C., and M. L. Gade. 1989. The Guardians: Boards of Trustees of American Colleges and Universities. Washington, DC: Association of Governing Boards of Universities and Colleges.

- Krücken, G., and F. Meier. 2006. “Turning the University Into an Organizational Actor.” In Globalization and Organization. World Society and Organizational Change, edited by Gili S. Drori, John W. Meyer, and Hokyu Hwang, 241–257. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Kwak, N., S. G. Gavrila, and F. O. Ramirez. 2019. “Enacting Diversity in American Higher Education.” In Universities as Agencies: Reputation and Professionalization, edited by Tom Christensen, Åse Gornitzka, and Francisco O. Ramirez, 209–228. Basingstoke: Palgrave MacMillan.

- Maasen, P., and J. Olsen. 2007. University Dynamics and European Integration. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Mathies, C., and S. Slaughter. 2013. “University Trustees as Channels between Academe and Industry: Toward an Understanding of the Executive Science Network.” Research Policy 42 (6-7): 1286–1300.

- Meyer, J. W., and E. Schofer. 2005. “The Worldwide Expansion of Higher Education in the Twentieth Century.” American Sociological Review 70 (6): 898–920.

- Mizruchi, M. S. 1996. “What do Interlocks Do? An Analysis, Critique, and Assessment of Research on Interlocking Directorates.” Annual Review of Sociology 22: 271–98.

- Musselin, C. 2018. “New Forms of Competition in Higher Education.” Socio-Economic Review 16 (3): 657–683.

- Pusser, B. 2003. “Beyond Baldridge: Extending the Political Model of Higher Education Organization and Governance.” Educational Policy 17 (1): 121–140.

- Ramirez, F. O. 2006. “The Rationalization of Universities.” In Transnational Governance: Institutional Dynamics of Regulation, edited by Marie-Laure Djelic, and Kerstin Sahlin-Andersson, 225–244. Cambridge: Oxford University Press.

- Ramirez, F. O. 2020. “The Socially Embedded American University: Intensification and Globalization.” In Missions of Universities: Past, Present, Future, edited by Lars Engwall, 131–161. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Scott, R. A. 2018. How University Boards Work: A Guide for Trustees, Officers, and Leaders in Higher Education. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Slaughter, S., and L. L. Leslie. 1997. Academic Capitalism: Politics, Policies, and the Entrepreneurial University. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Slaughter, S., and G. Rhoades. 2004. Academic Capitalism and the New Economy: Markets, State, and Higher Education. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

- Statistics Sweden. 2020a. “Standard för svensk yrkesklassificering (SSYK)”. Accessed November 4 2020. https://www.scb.se/dokumentation/klassifikationer-och-standarder/standard-for-svensk-yrkesklassificering-ssyk/.

- Statistics Sweden. 2020b. “Statistikdatabasen”. Accessed November 3 2020. https://www.statistikdatabasen.scb.se/pxweb/sv/ssd/START__NV__NV0117

- Veiga, A., A. Magalhaes, and A. Amaral. 2015. “From Collegial Governance to Boardism: Reconfiguring Governance in Higher Education.” In The Palgrave International Handbook of Higher Education Policy and Governance, edited by Jeroen Huisman, Harry De Boer, David D. Dill, and Manuel Souto-Otero, 398–416. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Wedlin, L., and J. Pallas. 2017. “Styrning och frihet – en ohelig allians?” In Det ostyrda universitetet? Perspektiv på styrning, autonomi och reform av svenska lärosäten, edited by Linda Wedlin, and Josef Pallas, 9–37. Göteborg: Makadam.