?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Communication skills are highly sought after by employers, as industry reports repeatedly show. At the same time, those reports also reveal that many employers are dissatisfied with their newly hired graduates’ communication skills. In addition, increasing globalisation has led to the call for ‘global graduates’ who can function well in culturally diverse contexts. Considering both aspects, it is important, to explore which factors help foster students’ global communication skills. This paper investigates this issue, testing the impact of potential factors identified from previous literature. Data was collected from 2359 students in seven different institutions located in five different countries. A linear regression model was tested to identify those factors which most contribute to global communication skills development. Results show that motivation to improve communication skills and the experience of social and academic integration into the campus community made the most significant contribution to participants’ higher levels of global communication skills development. Besides, students who were presented with relevant opportunities and support from their respective institution and those engaged with foreign languages also demonstrated higher levels of global communication skills development. The paper concludes that for students to acquire the communication skills needed for working successfully in diverse contexts, and hence to become ‘global graduates’, it is essential that they venture out of their comfort zones and engage with the diverse campus community. At the same time, this engagement requires universities’ guidance and support to help maximise the learning gains from such intercultural encounters.

Introduction

Over the past ten years, a large number of industry reports and academic papers have repeatedly reported that communication skills and skills related to them (e.g. working in diverse teams) are highly sought after by employers (e.g. Andrews and Higson Citation2008; British Council Citation2018; CBI/Pearson Citation2017; Diamond et al. Citation2011; Economist Intelligence Unit Citation2012; Financial Times Citation2018; Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS) Citation2019). At the same time, there are also reports that graduates are not always meeting employers’ expectations in this regard (CBI/Pearson Citation2017; QS Intelligence Unit Citation2018; QS Intelligence Unit Citation2018). Employers have started prioritising employability skills over academic performance when hiring new graduates (Financial Times Citation2016), so universities are under pressure to prepare students for their postgraduate careers.

Several governments and organisations have pointed to the role of education providers in fostering ‘global graduates’. For instance, the UK’s International Education Strategy (Department for Education and Department for International Trade Citation2019) states that universities should help foster ‘a generation of citizens who can succeed in an increasingly globalised world’ (p.24). Similarly, one of the objectives in the Swedish government’s strategy (Statens Offentliga Utredningar (SOU) Citation2018) is that ‘All students who earn university degrees have developed their international understanding or intercultural competence’ (p.42). They acknowledge that since not everyone can have international mobility experiences, this needs to be acquired at home. At university level, some strategies (e.g. University of Nottingham Citationn.d.; University of Sheffield Citationn.d) refer to this, mentioning the development of a ‘global mindset’ or ‘global citizenship’ within students and staff. Others, however, (e.g. University of Edinburgh Citationn.d.; University of Warwick Citationn.d.) do not mention this aspect explicitly but instead refer to the recruitment of staff and student talent from around the world and the promotion of international partnerships. Few, if any, make any specific mention of communication skills. Some (e.g. Durham University Citationn.d.) refer to the internationalisation of the curriculum, which may (or may not) include communication skills.

These insights raise a fundamental question: what kinds of educational contexts can help foster the communication skills that are particularly needed for culturally diverse contexts, such that graduates are better prepared for a globalised world of work and that employers become more satisfied with the skills that their recruits bring? We call such communication skills ‘global communication skills’. This paper addresses the question of how their development may be fostered using data from a large-scale international study.

Literature review

What are global communication skills?

Global communication skills (sometimes known as intercultural communication skills or competence) are the skills needed to communicate effectively in culturally diverse or unfamiliar contexts. Many of these skills are identical to those needed for communicating in any context, but as we explain below, they also have some particular features.

Foreign language skills and global communication skills are not synonymous. Foreign language skills refer to proficiency in one or more foreign languages to communicate ‘correctly’ with others, i.e. knowledge of the vocabulary and grammar. Fluency in a language does not automatically imply having a high level of global communication skills. This is because meaning is not coded and decoded mechanistically but requires the application of background knowledge (Kecskes Citation2014). Meaning is jointly constructed between the participants, and to achieve this successfully, shared background knowledge is essential. Differences in socialisation history and background can affect the perceived clarity of communication and require adjustments in communication patterns to build common ground, i.e. demonstrate global communication skills. This is especially true when there are differences in preference regarding how explicitly to convey information (e.g. Žegarac Citation2008).

Early research into second language acquisition identified several ways in which fluent speakers could promote mutual understanding (e.g. see Ellis Citation1994 for a clear summary). These include:

Manner of delivery (e.g. slower speed, longer pauses, clearer articulation)

Grammatical complexity (e.g. shorter sentences, simpler syntax)

Lexical complexity (e.g. use of higher frequency lexical items)

Discourse management (e.g. amount and type of information conveyed)

Discourse repair (e.g. requests for clarification and confirmation, repetitions)

Intercultural theorists have built on this and similar work to identify the skills needed for effective communication in culturally diverse contexts. For instance, Spencer-Oatey and Franklin (Citation2009, 83) list various facets such as ‘message attuning’, ‘active listening’, ‘building of shared knowledge’ and ‘linguistic accommodation’. As we explain below, we drew on this research in designing the items to probe the construct ‘global communication skills’.

Why are global communication skills essential?

Many recent reports on employer perspectives (e.g. British Council Citation2013; British Council Citation2018; CBI/Pearson Citation2017; Citation2019; Diamond et al. Citation2011; Economist Intelligence Unit Citation2012; QS Intelligence Unit Citation2018) have identified communication as one of the top skills employers are looking for. One of the most recent studies on global skills for employment (QS Intelligence Unit Citation2018) reports communication as the third most important skill for employers but reports a gap of 24% between that importance and employers’ satisfaction with their graduate recruits’ skills. However, it is not always clear just what kind of ‘communication skills’ are being referred to. Whether it refers primarily to the kinds of soft skills considered by Spencer-Oatey and Franklin (Citation2009) or to facets such as grammatical accuracy in writing and breadth of vocabulary. We return to this towards the end of the article. Nevertheless, facility in communication is clearly a vital graduate attribute that universities need to pay more attention to. This brings us to the next question: how can such skills be developed?

How can global communication skills be fostered?

One of the elements of successful learning of all kinds is motivation, and we suggest that this is equally true for developing global communication skills. For instance, Gudykunst (Citation2004) included it as a key element for developing effective intergroup communication. Others like Leung, Ang, and Tan (Citation2014) state that motivation is a primary driver for individuals to ‘learn about cultural differences and to understand culturally different others accurately’ (495). Similarly, the European INCA (Intercultural Competence and Assessment) project (Prechtl and Lund Citation2009) identified it as a foundational facet of their intercultural competence model. Moreover, ‘curiosity and discovery’ have been identified as essential components for achieving intercultural competence (Deardorff Citation2006; Bennett Citation2009). Since global communication skills are often subsumed under intercultural competence, we hypothesise:

H1: Students who attach more importance to the development of global communication skills will report higher levels of global communication skills development.

This explanation draws attention to two key features: the importance of interaction for language and communication development and the close interconnection between language and culture. Both are particularly relevant for internationalisation at home, where a diverse community of students (and staff) exists. It means that students of all backgrounds need to interact with each other if they are to enhance their language and global communication skills. Through participating in this way, students will be able to gain competence in managing interactions between themselves and others from culturally different backgrounds (see also Spitzberg and Chagnon Citation2009). Regarding global communication skills, we hypothesise:

H2: Students who engage more with the diverse campus community will report higher levels of global communication skills development.

H3: Students who perceive their universities as providing good opportunities and support for acquiring intercultural competence will report higher levels of global communication skills development.

H4: Students who engage more in developing their foreign language skills will report higher levels of global communication skills development.

Methodology

To test our hypotheses, a quantitative research methodology was used, with data collected through a questionnaire. The questionnaire was designed to provide insights into students’ study experiences across multiple universities on a larger scale. The sampling strategy, measures used to evaluate study experiences, and reliability measures will be discussed.

Sample

We collected data from 2359 students in seven different institutions located in five different countries (Belgium, Germany, Ireland, UK, and Uruguay). To achieve access to students in different universities, researchers had to liaise with each institution independently. The participating institutions chose which student cohorts we were permitted to link to our questionnaire to avoid survey fatigue among students. Thus, the collected data is not random in nature.

48% (1126) of students were female, and 50% (1183) were male. 2% (50) of students did not wish to disclose their gender. The sample consists of 70% undergraduate and 25% postgraduate students. Participants were from 98 different countries representing 55% domestic and 35% international students (10% did not wish to disclose this information).

Measures

The Global Education Profiler (GEP) was used to investigate our hypotheses and measures the five variables covered in our hypotheses. The GEP is a diagnostic tool that enables universities to evaluate the extent to which they provide students with an internationalised university experience and the level of engagement that students have with the various facets of internationalisation (Spencer-Oatey and Dauber Citation2019a). It measures four essential facets of student experiences, which our hypotheses reflect: (1) Global Communication Skills (CS), (2) Social and Academic Integration (IG), (3) Global Opportunities and Support (GOS) and (4) Foreign Language Skills (FLS).

The GEP measures each of these constructs twice: Once to capture how important these aspects of university life are to students and, second, the extent to which students experience them within their institutions. Both scales (importance and experience) use a 6-point Likert scale, with ‘1’ representing low importance/experience and ‘6’ representing high importance/experience. A Likert-scale without a neutral point was chosen because interpreting such a ‘middle option’ is often difficult and can have multiple reasons (for a comprehensive list, see Chyung et al. Citation2017). Studies on this topic tend to be somewhat inconclusive (e.g. Garland Citation1991). While some studies reveal no particular differences regarding the internal structure of the data (e.g. Leung Citation2011), other studies seem to show concerns (e.g. Weems and Onwuegbuzie Citation2001). Given the cross-cultural nature of this study, it is noteworthy that some studies demonstrated that there are cultural differences in how often participants pick the midpoint (e.g. Lee et al. Citation2002). As this would have likely affected our analysis negatively, we abstained from offering such an option and forced participants to choose. Thus, participants only could skip a question or randomly pick what was closest to their perceived accurate score.

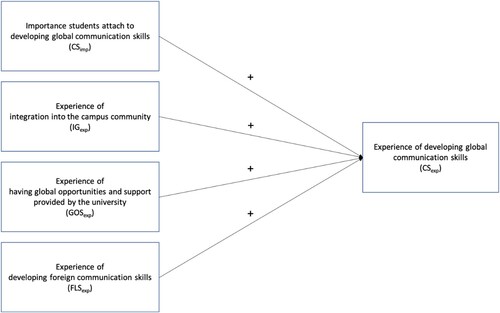

In this study, we will focus on five constructs in particular, as hypothesised above:

The perceived experience of developing global communication skills (CSexp)

The importance students attach to developing global communication skills (CSimp)

The experience of integration into the campus community (IGexp)

The experience of having global opportunities and support provided by the university (GOSexp), and

The experience of developing foreign communication skills (FLSexp).

Below we briefly outline the relevant measures.

Global communication skills (CSexp and CSimp)

Global Communication Skills focuses on the skills needed to communicate effectively in global contexts. It applies to fluent and less fluent speakers alike because an effective communicator needs to be able to adjust his/her language to the requirements of the contextual situation, including the level of fluency of other speakers. Items which probe this construct cover different elements of flexibility in communication, such as ways of conveying meaning clearly, checking with others for clarification, and varying communication style. Participants who score high on Global Communication Skills are excellent in both understanding others and conveying their own messages clearly. Eight items were used to measure this construct. Sample items include ‘I am getting better at explaining my ideas clearly to others’ and ‘If I don’t understand what someone else says, I find ways of clarifying what they mean’.

Integration (IGexp)

The notion of integration can be interpreted from many different angles (see also Spencer-Oatey and Dauber Citation2019b). In this paper, integration refers to the mixing and interaction of students from diverse backgrounds. It covers social and academic integration, such as participating in events that bring together people from different cultural backgrounds, having a diverse range of friends, discussing academic topics with people who have different background experiences, and working in multicultural groups. Students who score high on this construct attach importance to interacting with a wide range of people and take steps to ensure they make the most of their opportunities. Thirteen items were used to measure this construct. Sample items include ‘I spend time socialising with people from different cultural backgrounds’ and ‘I have good opportunities to carry out group projects with people from many different cultural backgrounds’.

Global opportunities and support (GOSexp)

Global Opportunities and Support probes the different ‘stretch’ opportunities offered to students that will help take them out of their comfort zone and engage with difference. It also probes the support they receive to gain the most from these opportunities. Students who score high on this construct have access to a wide range of diverse experiences and receive support to make the most of them. Global Opportunities and Support consists of ten items. Sample items include ‘The university offers many different types of opportunities for developing my intercultural skills’ and ‘The university’s career services help me in developing the intercultural skills I need to work in a global context’.

Foreign language skills (FLSexp)

Foreign Language Skills covers several facets of foreign language learning, including opportunities to develop foreign language skills, steps taken to improve foreign language skills, and actual use of a foreign language. Participants who score high on this construct exhibit great interest in speaking other languages and usually devote time to studying a language of choice s as well as proactively seeking opportunities to use it. Foreign Language Skills was measured using ten items. Sample items include ‘The university provides good opportunities for me to learn the foreign language of my choice’ and ‘I regularly spend time with fluent speakers of the foreign language I am learning’.

summarises the measures and the expected relationships with our dependent variable, i.e. CSexp.

Psychometric properties of measures

Reliability was established for the five constructs used in our hypotheses, with Cronbach's alpha ranging from 0.89–0.92 (see ). A confirmatory factor analysis was also conducted to confirm the fit of the items on each latent variable, and results showed a good fit as indicated by high values for Comparative Fit Index (CFI), Standardised Root Error of Approximation (RMSEA) and Standardised Root Mean Square Residual (SRMR) (see ). This suggests a consistent understanding of the GEP items across participants.

Table 1. Cronbach’s α for GEP constructs used in this study.

Table 2. Confirmatory factor analysis of all GEP constructs.

Results

The data were computed in R (V3.5.3) using relevant R packages such as’ leaps’ (Lumley & Miller Citation2020),’ MASS’ (Venables and Ripley Citation2002) and ‘caret’ (Kuhn Citation2020). While the GEP offers broader insights across all of its constructs, the following analysis will focus on the variables related to the abovementioned hypotheses.

Descriptive results

provides the main descriptive statistics for the GEP constructs used for the subsequent regression. The importance of global communication skills is rated high, with an average score of 4.59 and 88% of students rating it as important or very important. However, the experience of developing these skills is lower, with a statistically significant difference between importance and experience scores (t = 26.936, df = 2358, p < 0.001), but with only moderate effect size (Cohen's d = 0.555). While 70% of students reported experiencing development in these skills, 30% did not.

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of GEP constructs.

By far, the lowest scores are reported for GOSexp (mean = 3.45) and FLSexp (mean = 3.33), indicating that these two aspects are less experienced by students than other constructs. The mean scores fall slightly below the scale mean, i.e. below 3.5, and more than 50% of the respondents report not experiencing them. A third construct (IGexp) had a mean score (3.66) barely above the scale mean and with 44% of respondents reporting low levels of integration.

These results indicate that while experiences with integration, foreign language skills development and global opportunities and support are not extremely poor, they are also not good and offer much room for improvement. This finding also links to our hypotheses and rationale for the study, i.e. that the weak (global) communication skills of graduates often reported by employers may be due to the lack of relevant university experiences to foster such skills.

Given these findings, we then investigated our hypotheses on the factors that nurture the global communication skills of future graduates so that they can function effectively in culturally diverse workplaces.

Correlation results

The correlations between the independent variables and the experience scores of global communication skills were moderate (see ). To ensure that all independent variables contribute to explaining the variance in CSexp, a partial correlation was performed (see ). The relationship between independent variables dropped substantially, causing less concern for multicollinearity (see ). There is also a sharp decline in the correlation of CSexp with IGexp and GSexp. Despite this drop in correlation coefficients, they remained statistically significant. Therefore we kept both variables in our regression model to test our theoretical model and hypotheses.

Table 4. Correlation of variables (p < 0.001 for all r).

Table 5. Partial correlation of variables (p < 0.001 for all r).

Regression results

Before computing the regression, we tested whether any outliers existed in the data, which could affect the fit of a model to the overall data set. Since we were using more than one independent variable in this model, we used Cook’s distance measure to identify outliers (i.e. respondents) which had to be removed to avoid compromising the model’s ability to predict all cases. As a result, 121 (5%) cases were removed before the regression.

Results from a multiple regression with forced entry (see ) suggests that all independent variables significantly help to explain the variance in CSexp. However, CSimp and IGexp are particularly good predictors. Thus, the importance students attach to global communication skills (H1) and their sense of integration into the campus community (H2) mainly explain how much they believe they have developed their global communication skills. The extent to which students receive support in developing intercultural communication skills (H3) and their opportunities to learn and develop their foreign language abilities (H4) also contributed to their development of global communication skills, but to a lesser extent. We explore the implications of these insights in greater detail in the discussion section below.

Table 6. Results from multiple regression.

The results were validated through a Durbin-Watson test, which showed independence of errors (autocorrelation = 0.027, DW statistics = 1.947, p = 0.232). There were also no issues with multicollinearity (see ).

Table 7. Multicollinearity diagnostics.

In a final step, we included age and gender as control variables to see whether this would further improve our model. Both, age (β = 0.006, t = 2.166, p = 0.030) and gender (β = 0.0421, t = 1.762, p = 0.078) did not contribute to the explanatory power of the model and, therefore, have no impact on students’ higher education experiences regarding their development of communication skills.

Discussion

This section considers the outcome of each hypothesis in turn and reflects on how the results enhance our understanding of prior research. We also provide recommendations for future investigations in this area.

Motivation matters

If students consider global communication skills unimportant, they will not invest time and effort to develop them. This study has shown that most students’ attitudes are already very high toward developing global communication skills. This can likely be attributed to the growing awareness of ‘intercultural’ communication as an essential skill in many degree programmes and research fields, e.g. Information Systems (Mitchell and Benyon Citation2018), Engineering (Riemer Citation2007), Management (Jameson Citation1993), and others.

The regression results (H1) support previous research highlighting the significance of intercultural skills/intelligence in developing global communication skills (e.g. Chirkov et al. Citation2007; Chirkov et al. Citation2008). Our study shows that the importance students attach to developing global communication skills has the most substantial impact on developing such skills (β = 0.38615). This highlights the need to encourage students to value these skills and motivate them to work on them. Previous research has shown that motivation plays a crucial role in developing competencies and skills and is linked to positive behavioural and well-being outcomes in culturally diverse contexts (e.g. Chirkov et al. Citation2007; Chirkov et al. Citation2008). This study provides new insights into the development of global communication skills and emphasises the crucial role of students’ motivation in this process.

Most degree programmes aim to socialise students into the communication genres required for their discipline. However, it is unclear to what extent they actively foster the development of global communication skills. The assumption that discipline-based communication skills are sufficient may not hold true, as evidenced by industry reports at the beginning of this paper. A diverse classroom provides a valuable opportunity to foster these skills (Reissner-Roubicek and Spencer-Oatey Citation2021). Raising awareness of the benefits of the classroom and ways to maximise them could enhance the development of global communication skills. Further research in this area is essential and necessary.

Integration aids the development of students’ global communication skills

The development of global communication skills has long been considered a primary outcome of studying abroad (e.g. Chieffo and Griffiths Citation2004; Williams Citation2005; Pedersen Citation2010). However, research highlights that the quality of these experiences matters (Schartner Citation2016). With the increase in inbound international student mobility, universities can leverage their diverse student body to promote global communication skills development without the need to study abroad. This is possible through ‘internationalisation at home’ initiatives, which aim to enable students to engage effectively with cultural others and develop global communication skills. While a diverse student body can provide benefits, it is crucial that students feel integrated (e.g. Song Citation2013; Spencer-Oatey and Dauber, Citation2019b; Hernandez Citation2019).

Integration is an essential component of every community and can be analysed on three different levels regarding higher education institutions: individual, community and institutional (Spencer-Oatey and Dauber Citation2019b). Especially the individual and community levels have crucial personal benefits for students, such as well-being, satisfaction and positive engagement with others. Rienties et al. (Citation2012) showed in an extensive study of 958 students that academic integration also significantly improves students’ academic achievements.

Integration in the academic and social sphere plays a crucial role in developing global communication skills, as found in this study (H2). Cross-language socialisation in the form of integration is an important aspect of internationalised campus communities and contributes to developing these skills. Encouraging students to move outside of their comfort zones, against their natural tendency of homophily (McPherson, Smith-Lovin, and Cook Citation2001), and appreciating the benefits of unfamiliar experiences is essential for fostering these skills.

As Spencer-Oatey and Dauber (Citation2019b) emphasise, integration is a process which involves all members of an institution. While the responsibility for making contact with other students outside the classroom resides mostly with students themselves, it should be a consideration for lecturers to revisit curricula designs and classroom management to incorporate elements that may require students to move out of their comfort zone not only in classroom settings but also outside of it. While elaborating on such options would reach beyond the scope and purpose of this study, we deem it a promising and necessary area for future research and development.

Providing opportunities and support for global communication skills development

Universities must support students in developing global communication skills, as it is not just an individual effort. Opportunities for development are important, but without support, students may experience negative emotions and psychological stress (e.g. Furnham and Bochner Citation1986; Ward, Bochner, and Furnham Citation2001; Chapdelaine and Alexitch Citation2004). This can impact their task self-efficacy beliefs and limit their engagement in similar experiences. To help students make sense of their experiences, universities must provide pedagogical guidance (e.g. Schartner Citation2016; Pedersen Citation2010).

While there are some good resources available to guide institutions in their support of students’ global communication skills development (e.g. Reissner-Roubicek and Spencer-Oatey Citation2021; World Council on Intercultural and Global Competence Citation2022; UK Council for International Student Affairs Citation2022) the amount of information and resources available to educators and universities appears to be small or not publicly accessible.

The study shows that university support is key to developing global communication skills. Students who use these resources are more likely to engage in interactions that improve their skills (H3). Universities should provide students with guidance, assistance, and feedback to reinforce their motivation and understanding of the importance of these skills. However, it's important to monitor and assess the effectiveness of these measures in the long term. Further research is needed to determine the effectiveness of current ‘best practices’ for supporting students in developing their global communication skills, especially if their experiences have a negative impact on their well-being.

Learning a foreign language helps in cross-cultural communication

Hypothesis H4 explored the relationship between foreign language learning and the development of global communication skills. The findings indicate a moderate yet significant connection between the two. This supports previous research that showed language acquisition could improve intercultural sensitivity (Wu Citation2016) and enhance communication skills (Sarwari and Abdul Wahab Citation2017).

Theoretical implications and future directions

The study identified significant factors affecting students’ development of global communication skills, including individual and contextual factors moving beyond curricula and training offerings. Future studies could focus on fostering global communication skills through lectures and seminars, where students spend most of their time. Comparing students with high and low scores for the importance and experiences of global communication skills could offer further and deeper insights into their skills development.

The effects of the COVID-19 pandemic have resulted in a shift towards online learning, but its long-term impact is uncertain. Previous research found low student engagement in online lectures (Mayende, Prinz, and Isabwe Citation2017) and graduates lacking in online collaboration competencies, including communication skills (Kolm et al. Citation2022). As universities gradually resume in-person teaching, graduates may still need to work remotely after transitioning into a workplace, making it crucial for universities to equip them with the necessary communication skills for virtual settings. Further research on this topic is necessary.

Limitations

The results of this study apply only to the specific institutions studied and should not be assumed to be generalisable to other universities within our outside of Europe. However, considering these factors may help universities and students identify areas for improvement.

The study investigates the impact of non-curricular contexts on students’ perceived development of global communication skills. It's essential to note that the results are based on self-perception measures and may not accurately reflect students’ actual communication skills. Also, students rated their experiences as moderate, with 50% scoring CSexp 4.12. Further exploration of students who were and who were not exposed to more growth-enhancing contexts and their future workplace performance is needed to understand the impact of non-classroom-related social interactions on their global communication skills development.

The study focused on students’ perspectives, but staff members play a crucial role in developing their global communication skills. Future studies should include a complementary staff perspective to provide a more comprehensive understanding of how study experiences can be improved.

It is important to note that the results of this study are limited to trends and generalisations based on a quantitative approach. Further investigation into students’ study experiences using qualitative methods can offer more detailed insights into contexts of growth, e.g. by examining university mission statements, programme and course materials, etc. Incorporating qualitative research elements would also provide a deeper understanding of this study's main findings and further unpack the relationships between variables.

Conclusion

This study provides large-scale empirical evidence on the factors that foster global communication skills, which are highly valued by employers. Four key factors were identified: the importance placed on skill development, integration into the community, engagement with foreign language learning, and institutional support. While curricula design remains important, the results suggest that a flourishing, productive, and socially shared learning environment is crucial.

Future research should examine growth opportunities outside of the regularly taught component of students’ study life. The results suggest that (1) students need to be made aware that even though they may find it frustrating or discouraging to interact with people from different (language) backgrounds, those experiences can foster essential skills within them that will be helpful to their future careers. Also, (2) university support is essential in helping students identify, explore and leverage such learning opportunities.

Availability of data and material

Due to research ethics regulations, we are not allowed to share data with third parties. This is what participants consented to when completing the questionnaire.

Research ethics

Ethical approval for this research was granted by the HSSREC of the University of Warwick. Participants had to provide consent prior to completing the online questionnaire.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Andrews, Jane, and Helen Higson. 2008. “Graduate Employability, ‘Soft Skills’ Versus ‘Hard’ Business Knowledge: A European Study.” Higher Education in Europe 33 (4): 411–22. doi:10.1080/03797720802522627

- Bennett, J. M. 2009. “Cultivating Intercultural Competence: A Process Perspective.” In The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, edited by Darla K. Deardorff, 121–40. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- British Council. 2013. Culture at Work. The Value of Intercultural Skills in the Workplace. London: British Council. April 2019. https://www.britishcouncil.org/organisation/policy-insight-research/research/culture-work-intercultural-skills-workplace.

- British Council. 2018. “Employability in Focus. Exploring Employer Perspectives of Overseas Graduates returning to China.” February 2019, https://www.agcas.org.uk/write/MediaUploads/Resources/ITG/British_Council_Employability_in_Focus_China.pdf.

- Carroll, J., and J. Appleton. 2007. “Support and Guidance for Learning from an International Perspective.” In Internationalising Higher Education, edited by Elspeth Jones, and Sally Brown, 72–85. London: Routledge.

- CBI/Pearson. 2017. “Helping the UK thrive. CBI/Pearson Education and Skills Survey.” April 2019. https://www.cbi.org.uk/media/1341/helping-the-uk-to-thrive-tess-2017.pdf.

- CBI/Pearson. 2019. “Education and Learning for the Modern World. CBI/Pearson Education and Skills Survey.” 20 April 2019. https://www.cbi.org.uk/media/3841/12546_tess_2019.pdf.

- Chapdelaine, R. F., and L. R. Alexitch. 2004. “Social Skills Difficulty: Model of Culture Shock for International Graduate Students.” Journal of College Student Development 45 (2): 167–84. doi:10.1353/csd.2004.0021

- Chieffo, L., and L. Griffiths. 2004. “Large-scale Assessment of Student Attitudes After a Short-Term Study Abroad Program.” Frontiers: The Interdisciplinary Journal of Study Abroad 10 (1): 165–77. doi:10.36366/frontiers.v10i1.140

- Chirkov, V. I., S. Safdar, D. J. de Guzman, and K. Playford. 2008. “Further Examining the Role Motivation to Study Abroad Plays in the Adaptation of International Students in Canada.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 32 (5): 427–40. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2007.12.001

- Chirkov, V., M. Vansteenkiste, R. Tao, and M. Lynch. 2007. “The Role of Self-Determined Motivation and Goals for Study Abroad in the Adaptation of International Students.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 31 (2): 199–222. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2006.03.002

- Chyung, S. Y., K. Roberts, I. Swanson, and A. Hankinson. 2017. “Evidence-Based Survey Design: The Use of a Midpoint on the Likert Scale.” Performance Improvement 56 (10): 15–23. doi:10.1002/pfi.21727

- Deardorff, D. K. 2006. “Identification and Assessment of Intercultural Competence as a Student Outcome of Internationalization.” Journal of Studies in International Education 10 (3): 241–66. doi:10.1177/1028315306287002

- De Bot, K., and C. Jaensch. 2015. “What is Special About L3 Processing?” Bilingualism: Language and Cognition 18 (2): 130–44. doi:10.1017/S1366728913000448

- Department for Education, & Department for International Trade. 2019. “International Education Strategy. Global potential, global growth.” London, UK. January 2020. www.gov.uk/education or www.gov.uk/dit.

- Diamond, A., L. Walkley, P. Forbes, T. Hughes, and J. Sheen. 2011. Global graduates. Global graduates into global leaders. Association of Graduate Recruiters (AGR), the Council for Industry and Higher Education (now NCUB) and CFE Research and Consulting. April 2017. http://www.ncub.co.uk/reports/global-graduates-into-global-leaders.html.

- Dufon, M. A. 2008. “Language Socialisation Theory and the Acquisition of Pragmatics in the Foreign Language Classroom.” In Investigating Pragmatics in Foreign Language Learning, Teaching and Testing, edited by Eva Alcón, and Alicia Martínez-Flor, 25–44. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Durham University. n.d. Global Durham. February 2020 https://www.dur.ac.uk/strategy2027/global.

- Economist Intelligence Unit. 2012. “Competing across Borders. How cultural and communication barriers affect business”. March 2020. https://www.cfoinnovation.com/competing-across-borders-how-cultural-and-communication-barriers-affect-business.

- Ellis, R. 1994. The Study of Second Language Acquisition. Oxford: OUP.

- Financial Times. 2016. “‘Big four’ look beyond academics.” March 2020. https://www.ft.com/content/b8c66e50-beda-11e5-9fdb-87b8d15baec2.

- Financial Times. 2018. “What top employers want from MBA graduates.” March 2020.https://www.ft.com/content/64b19e8e-aaa5-11e8-89a1-e5de165fa619.

- Furnham, A., and S. Bochner. 1986. Culture Shock. New York: Methuen & Co.

- Garland, R. 1991. “The Mid-Point on a Rating Scale: Is it Desirable.” Marketing Bulletin 2 (1): 66–70.

- Grant-Vallone, E., K. Reid, C. Umali, and E. Pohlert. 2003. “An Analysis of the Effects of Self-Esteem, Social Support, and Participation in Student Support Services on Students’ Adjustment and Commitment to College.” Journal of College Student Retention: Research, Theory & Practice 5 (3): 255–74. doi:10.2190/C0T7-YX50-F71V-00CW

- Grosjean, F. 2012. Bilingual: Life and Reality. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

- Gudykunst, W. B. 2004. Bridging Differences. Effective Intergroup Communication. 4th ed. London: Sage.

- Hernandez, M. R. 2019. “Living Abroad: Irish Erasmus Students Experiences’ of Integration in Spain.” In Education Applications & Developments IV, edited by M. Carmo, 63–72. SciencePress.

- Jameson, D. A. 1993. “Using a Simulation to Teach Intercultural Communication in Business Communication Courses.” The Bulletin of the Association for Business Communication 56 (1): 3–8. doi:10.1177/108056999305600102

- Kecskes, I. 2014. Intercultural Pragmatics. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Killick, D. 2018. Developing Intercultural Practice. Academic Development in a Multicultural and Globalizing World. London: Routledge.

- Kolm, A., J. de Nooijer, K. Vanherle, A. Werkman, D. Wewerka-Kreimel, S. Rachman-Elbaum, and J. J. G. van Merriënboer. 2022b. “International Online Collaboration Competencies in Higher Education Students: A Systematic Review.” Journal of Studies in International Education 26 (2): 183–201. doi:10.1177/10283153211016272

- Kuhn, M. 2020. “caret: Classification and Regression Training. R package version 6.0-86”. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package = caret.

- Lee, J. W., P. S. Jones, Y. Mineyama, X. E. Zhang, and X. E. 2002. “Cultural Differences in Responses to a Likert Scale.” Research in Nursing & Health 25 (4): 295–306. doi:10.1002/nur.10041

- Leung, S. O. 2011. “A Comparison of Psychometric Properties and Normality in 4-, 5-, 6-, and 11-Point Likert Scales.” Journal of Social Service Research 37 (4): 412–21. doi:10.1080/01488376.2011.580697

- Leung, K., S. Ang, and M. L. Tan. 2014. “Intercultural Competence.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 1 (1): 489–519. doi:10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-031413-091229

- Longman, J. 2008. “Language Socialization.” In Encyclopedia of Bilingual Education, edited by Josué M. González, 489–92. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

- Lumle, T., and Miller A. 2020. Leaps: Regression Subset Selection. R package version 3.1. https://CRAN.R-project.org/package = leaps

- Mayende, G., A. Prinz, and G. M. N. Isabwe. 2017. “Improving Communication in Online Learning Systems.” Proceedings of the 9th international conference on computer supported education, 1, 300-307.

- McPherson, M., L. Smith-Lovin, and J. M. Cook. 2001. “Birds of a Feather: Homophily in Social Networks.” Annual Review of Sociology 27: 415–44. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.27.1.415

- Mitchell, A., and R. Benyon. 2018. “Teaching Tip: Adding Intercultural Communication to an IS Curriculum.” Journal of Information Systems Education 29 (1): 1–10.

- Napoli, A. R., and P. M. Wortman. 1998. “Psychosocial Factors Related to Retention and Early Departure of Two-Year Community College Students.” Research in Higher Education 39 (4): 419–55. doi:10.1023/A:1018789320129

- Pedersen, P. J. 2010. “Assessing Intercultural Effectiveness Outcomes in a Year-Long Study Abroad Program.” International Journal of Intercultural Relations 34 (1): 70–80. doi:10.1016/j.ijintrel.2009.09.003

- Prechtl, E., and A. Davidson Lund. 2009. “Intercultural Competence and Assessment: Perspectives from the INCA Project.” In Handbook of Intercultural Communication, edited by Helga Kotthoff, and Helen Spencer-Oatey, 467–90. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

- QS Intelligence Unit. 2018. The Global Skills Gap in the 21st Century. Accessed 13 January 2019. https://www.qs.com/the-global-graduate-skills-gaps/.

- Reissner-Roubicek, S., and H. Spencer-Oatey. 2021. “Positive Interaction in Intercultural Group Work: Developmental Strategies for Success.” In International Student Education in Tertiary Settings: Interrogating Programmes and Processes in Diverse Contexts, edited by Z. Zhang, T. Grimshaw, and X. Shi, 82–104. Abingdon, Oxon, UK: Routledge.

- Riemer, M. J. 2007. “Communication Skills for the 21st-Century Engineer.” Global Journal of Engineering Education 11 (1): 89–100.

- Rienties, B., S. Beausaert, T. Grohnert, S. Niemantsverdriet, and P. Kommers. 2012. “Understanding Academic Performance of International Students: The Role of Ethnicity, Academic and Social Integration.” Higher Education 63 (6): 685–700. doi:10.1007/s10734-011-9468-1

- Sarwari, A. Q., and M. N. Abdul Wahab. 2017. “Study of the Relationship between Intercultural Sensitivity and Intercultural Communication Competence among International Postgraduate Students: A Case Study at University Malaysia Pahang.” Cogent Social Sciences 3 (1): 1–11. doi:10.1080/23311886.2017.1310479

- Schartner, A. 2016. “The Effect of Study Abroad on Intercultural Competence: A Longitudinal Case Study of International Postgraduate Students at a British University.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 37 (4): 402–18. doi:10.1080/01434632.2015.1073737

- Song, G. 2013. “Academic and Social Integration of Chinese International Students in Italy.” Asia Pacific Journal of Educational Development (APJED) 2 (1): 13–25.

- Spencer-Oatey, H., and D. Dauber. 2019a. “Internationalisation and Student Diversity: Opportunities for Personal Growth or Numbers-Only Targets?” Higher Education 78: 1035–58. doi:10.1007/s10734-019-00386-4.

- Spencer-Oatey, H., and D. Dauber. 2019b. “What Is Integration and Why Is It Important for Internationalization? A Multidisciplinary Review.” Journal of Studies in International Education 23 (5): 515–34. doi:10.1177/1028315319842346.

- Spencer-Oatey, H., and P. Franklin. 2009. Intercultural Interaction. A Multidisciplinary Approach to Intercultural Communication. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Spitzberg, B. H., and G. Chagnon. 2009. “Conceptualizing Intercultural Competence.” In The SAGE Handbook of Intercultural Competence, edited by D. K. Deardorff, 2–52. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE.

- Statens Offentliga Utredningar (SOU). 2018. “En strategisk agenda för internationalisering [A strategic agenda for internationalisation]”. Stockholm. Accessed January 2019. https://www.regeringen.se/490aa7/contentassets/2522e5c3f8424df4aec78d2e48507e4f/en-strategisk-agenda-for-internationalisering.pdf.

- UK Council for International Student Affairs. 2022. November 2022. https://www.ukcisa.org.uk/Research–Policy/Resource-bank.

- Universities and Colleges Admissions Service (UCAS). 2019. What skills are employers looking for and why are they important? February 2020. https://www.ucas.com/careers/getting-job/what-are-employers-looking.

- University of Edinburgh. n.d. “Our global engagement plan. A map to deliver our strategic goals 2017-2020.” 2020. https://global.ed.ac.uk/sites/default/files/atoms/files/Our%20Global%20Engagement%20Plan.pdf.

- University of Nottingham. n.d. “Strategy.” February 2020. https://www.nottingham.ac.uk/strategy/documents/university-strategy.pdf.

- University of Sheffield. n.d. “Our internationalisation strategy.” February 2020. https://www.sheffield.ac.uk/polopoly_fs/1.749757!/file/IS2.pdf.

- University of Warwick. n.d. Excellence with a purpose - Strategy. International February 2020. https://warwick.ac.uk/about/strategy/international.

- Venables, W. N., and B. D. Ripley. 2002. Modern Applied Statistics with S. Fourth Edition. New York: Springer. ISBN 0-387-95457-0.

- Ward, C. A., S. Bochner, and A. Furnham. 2001. The Psychology of Culture Shock. London: Psychology Press.

- Weems, G. H., and A. J. Onwuegbuzie. 2001. “The Impact of Midpoint Responses and Reverse Coding on Survey Data.” Measurement and Evaluation in Counseling and Development 34 (3): 166–76. doi:10.1080/07481756.2002.12069033

- Williams, T. R. 2005. “Exploring the Impact of Study Abroad on Students’ Intercultural Communication Skills: Adaptability and Sensitivity.” Journal of Studies in International Education 9 (4): 356–71. doi:10.1177/1028315305277681.

- World Council on Intercultural and Global Competence. 2022. November 2022, https://iccglobal.org/resources/resources.

- Wu, J.-F. 2016. “Impact of Foreign Language Proficiency and English Uses on Intercultural Sensitivity.” International Journal of Modern Education and Computer Science 8: 28–35. doi:10.5815/ijmecs.2016.08.04.

- Žegarac, V. 2008. “Culture and Communication.” In Culturally Speaking. Culture, Communication and Politeness Theory, edited by Helen Spencer-Oatey, 47–70. London: Continuum.