ABSTRACT

Academics’ conceptions of teaching (ACTs) and academics’ teaching approaches (ATAs) are essential factors in informing academics’ teaching behaviors. However, empirical evidence from longitudinal research exploring the causal link between ACTs and ATAs is lacking. In the current study, we employed a cross-lagged panel model approach in three waves to assess four hypotheses (i.e. stability, causal, reversed, and reciprocal models) concerning the causal association between ACTs and ATAs. For the data collection from 115 academics (60.9% female), we used the Conceptions of Teaching and Learning and the Revised Approaches to Teaching Inventory. Our findings indicated that ATAs were a causal predictor of ACTs, not vice-versa, regardless of participants’ gender and teaching responsibilities. Specific ATAs (i.e. student-centered or teacher-centered) predicted complementary ACTs in time. Our results reveal that conceptual changes in academics can be possible after observing the positive effects of a specific teaching method on student learning. Therefore, academic developers should help academics (especially novice teachers) accurately distinguish student-centered from teacher-centered teaching behaviors and learn how to apply specific student-centered teaching methods in conjunction with self-reflective techniques. More empirical longitudinal studies with sound designs are needed to understand better the multi-directional nature and influence between ACTs and ATAs over time.

Introduction

Nowadays, academics are expected not only to produce high-quality research outputs but also to successfully transition towards student-centered teaching (Kaasila et al. Citation2021). Even though plenty of evidence supports the effectiveness of student-centered teaching, student-centered instruction is not easy to achieve (Entwistle Citation2009; Trigwell and Prosser Citation1996). To understand how academics can adopt a student-centered teaching behavior, the research on academics’ teaching approaches (ATAs) and academics’ conceptions of teaching (ACTs) is paramount (Kember and Kwan Citation2000; Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2008). In this context, ACTs and ATAs were found to correlate around 89% (Kember and Kwan Citation2000). Also, ATAs significantly impact students’ learning approaches (Entwistle et al. Citation2000; Prosser and Trigwell Citation2014). Specifically, student-centered teaching approaches can impact students’ deep learning, leading to higher student achievements (Entwistle Citation2009; Uiboleht, Karm, and Postareff Citation2018). When academics approach their teaching in a student-centered manner, the probability that their students will adopt reflective study practices and be more engaged in understanding the subject matter and its utility increases (i.e. deep learning approach) (Asikainen and Gijbels Citation2017). Contrariwise, when academics embrace a teacher-centered teaching approach, it is more probable that their students will adopt unreflective studying practices such as memorizing and focusing on reproducing the learning material (i.e. surface learning approach) (Ho, Watkins, and Kelly Citation2001; Uiboleht, Karm, and Postareff Citation2018). Hence, one of the primary purposes of many instructional development programs (IDPs) has been to support academics make the transition from teacher-centered toward student-centered teaching (Saroyan and Trigwell Citation2015).

Several IDPs successfully helped academics transition toward student-centered teaching (e.g. Emery, Maher, and Ebert-May Citation2020; Gibbs and Coffey Citation2004). However, a recent meta-analysis on controlled studies (Ilie et al. Citation2020) indicated a small practical effect (d Cohen = 0.315) of IDPs on academics’ outcomes. The most common explanation for why academics avoid employing student-centered teaching forms relies on their underlying teaching conceptions (Entwistle and Walker Citation2000; Kember Citation2009). Most studies reported that significant changes in academics’ teaching approaches are improbable to exist without transformations in their teaching conceptions (Åkerlind Citation2004; Ho, Watkins, and Kelly Citation2001). Nonetheless, this relation must be treated cautiously because some studies do not support it (Peeraer et al. Citation2011) or reached the opposite conclusion (i.e. transformations in academics’ instructional approaches precede changes in their teaching conceptions) (Guskey Citation1986, Citation2002; Pedrosa-de-Jesus and Lopes Citation2011).

To deliver adequate pedagogical training to academics, it is essential to understand how academics develop as teachers and the influences acting upon this development. Achieving this purpose demands an in-depth understanding of the causal processes affecting the interaction between academics’ thinking and teaching behavior (Samuelowicz and Bain Citation1992). For this aim, the multi-directional nature and influence between ACTs and ATAs (Eley Citation2006; Sadler Citation2012) and longitudinal research designs must be considered (Taris and Kompier Citation2014). Longitudinal study designs can give us details concerning the temporal ordering of the circumstances underlying the relationships between ACTs and ATAs (i.e. it can indicate how the supposed ‘outcomes” have modified over time and whether the modification can be explained by changes in the supposed ‘independent” variables). Therefore, longitudinal investigations with the same set of participants and the exact variables being measured at least twice across time are needed to acquire more robust knowledge about the causal associations between ACTs and ATAs (Taris and Kompier Citation2014). Despite the importance of the relationship between ATAs and ACTs in informing teaching behaviors, only a few studies have investigated them jointly. The existing investigations highlighted a strong association between ATAs and ACTs but failed to bring empirical evidence regarding the dynamic of their relationship (Kember and Kwan Citation2000). As far as we know, with the notable exception of Pedrosa-de-Jesus and Lopes (Citation2011), based on two data waves, no investigations approached the longitudinal association between ACTs and ATAs. The existing investigations mainly employed a quantitative (Norton et al. Citation2005; Peeraer et al. Citation2011) or qualitative cross-sectional design (Eley Citation2006; Kember and Kwan Citation2000). Hence, existing studies only inform us about the static relationship between ATAs and ACTs. Elucidating the direction of the influences between ACTs and ATAs over time could be essential in developing teaching quality in higher education (Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2008). For example, suppose evidence would sustain the idea that ATAs are a consequence of ACTs. Such a finding could be an indicator to deliver instructional activities aiming to change academics’ conceptions of teaching as first sequences of IDPs before engaging academics in instructional activities aspiring to develop their teaching skills.

The current research aimed to determine the directional effects of the relationship between ACTs and ATAs. We used a 3-wave longitudinal design and the cross-lagged panel analysis on responses to the Conceptions of Teaching and Learning (COLT, Jacobs et al. Citation2012) and the Revised Approaches to Teaching Inventory (R-ATI, Trigwell, Prosser, and Ginns Citation2005) inventories to achieve this aim. We started by defining the academics’ teaching conceptions, teaching approaches, their relationship, and the cross-lagged analysis. Next, we presented the methodology and the results and discussed the findings. We also advanced recommendations for future developments in instructional development practice dedicated to academics and research on the subject. Complementary, we presented the adaptation process of the COLT inventory (Jacobs et al. Citation2012) in the Romanian context.

Academics’ conceptions of teaching (ACTs) and academics’ teaching approaches (ATAs)

Given the importance of ATAs and ACTs in informing academics’ instruction behaviors, many efforts have been invested in understanding these two concepts. ACTs represent how academics think about and view teaching and learning (Pratt Citation1992). Researchers agree on several consensuses regarding academics’ conceptions of teaching, mostly proved through phenomenographic procedures or other qualitative analyzes (Sadler Citation2012). For example, academics’ have personal teaching conceptions because of their educational path (Norton et al. Citation2005), or teaching conceptions are developed from each one's long experience in the classroom, first as a student and later as a teacher (Prosser, Trigwell, and Taylor Citation1994; Pratt Citation1992). Likewise, ACTs guide how academics approach their teaching (Kember and Kwan Citation2000). Also, there seems to be a general agreement about ACTs which could range from teacher-centered to student-centered conceptions of teaching (Kember Citation1997; Samuelowicz and Bain Citation2001; Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2008). ATAs are ‘a combination between one's intention of teaching and teaching strategy” (Trigwell and Prosser Citation1996, 78). Teaching intentions vary from the transmission of disciplines’ content (i.e. teacher-centered) to supporting change in students’ conceptions of the subject matter (i.e. student-centered) (Trigwell, Prosser, and Taylor Citation1994; Prosser and Trigwell Citation2014). Accordingly, when one considers teaching a process of knowledge transmission, its main teaching strategies aim to present the subject matter (Prosser and Trigwell Citation2014). Also, when one considers teaching as a process that contributes to the students’ building their own knowledge about the subject matter, the main teaching strategies encourage students’ engagement in the learning process and critical thinking (Prosser and Trigwell Citation2014; Postareff and Lindblom-Ylänne Citation2008). Thus, student-centered teaching conceptions and approaches are preferable to the detriment of teacher-centered conceptions and approaches because they are more sophisticated and focused on students’ learning and growth (Kember Citation1997; Entwistle et al. Citation2000; Prosser and Trigwell Citation2014). However, some studies pointed out that academics may adopt elements from both ATAs in their practice (e.g. Postareff et al. Citation2008; Stes and Van Petegem Citation2014; Uiboleht, Karm, and Postareff Citation2018). Expressly, academics can embrace either a ‘consonant’ (i.e. they adopt exclusively student- or teacher-centered elements) or a ‘dissonant’ teaching approach (i.e. they adopt elements from both ATAs) (Postareff et al. Citation2008).

Even though existing evidence indicates a strong static association (r2 = 89%) between ATAs and ACTs (Kember and Kwan Citation2000), there is a lack of empirical evidence concerning the causal relationship between ATAs and ACTs. Thus, the issue of the direction of the temporal order between the two variables is one of the most heated debates in the literature concerning ACTs and ATAs. In this respect, there are different perspectives. First, ACTs represent the foundation of academics’ teaching practices (Trigwell and Prosser Citation1996; Samuelowicz and Bain Citation2001). Thus, if one has a particular teaching conception, then he/she is inclined to have specific intentions, leading to the choice of complimentary teaching strategies (Kember and Kwan Citation2000; Trigwell and Prosser Citation1996). For example, a recent study that used network analysis (Mladenovici et al. Citation2022) concluded that when it comes to academics’ decisions about their teaching approaches, their conceptions about the subject matter are paramount. On the other hand, there is also evidence that change in instructional practices forewent transformations in teaching conceptions (Guskey Citation1986, Citation2002; Pedrosa-de-Jesus and Lopes Citation2011). According to those studies, it is easier to modify specific teaching practices than teaching conceptions. The change process of ACTs starts after modifications in their teaching approaches. For example, Pedrosa-de-Jesus and Lopes (Citation2011) concluded that academics’ that learned to use questioning as a specific instruction method after realizing the impact on student learning also modified their teaching conceptions. Finally, some previous studies mentioned a multi-directional nature and reciprocal influences between ACTs and ATAs (e.g. Eley Citation2006; Sadler Citation2012). For example, Sadler (Citation2012) used a longitudinal research design with three semi-structured interviews and found that reciprocal influences between ATAs and ATCs are possible. In the first period, academics with teacher-focused conceptions used similar teaching approaches in their daily teaching practice. However, after a critical moment when they used instructional strategies based on more interaction with students, the same academics evolved their conceptions to more student-focused ones.

Several previous studies highlighted that ACTs and ATAs could also be influenced by different contextual or personal variables such as teaching context, teachers’ teaching experiences or gender, etc. (e.g. McMinn, Dickson, and Areepattamannil Citation2022; Postareff and Nevgi Citation2015; Vilppu et al. Citation2019). For example, McMinn, Dickson, and Areepattamannil (Citation2022) found that female academics are more willing to adopt a student-centered teaching approach than male academics. Also, Vilppu et al. (Citation2019) highlighted that is more difficult to determine experienced academics to change their conceptions of teaching than novice teachers who are more open to negotiating their conceptions. Thus, such variables also may play a role in determining the nature of the relationship between ATAs and ACTs and, consequently, should be taken into consideration when this relation is investigated.

The cross-lagged panel analysis

The research on ACTs and ATAs was almost exclusively conducted on cross-sectional data, mainly analyzed through phenomenographic procedures or other qualitative analyzes (Sadler Citation2012). Studies with a longitudinal design are needed to examine the direction of the mutual influences between ACTs and ATAs over time. In conjunction with a longitudinal design, one must use an appropriate statistical technique such as cross-lagged panel analysis, co-occurrence analysis, network analysis, generalized moments, etc. Out of those perspectives, we chose the cross-lagged analysis as the most suitable approach for the current study (Kearney Citation2017). Cross-lagged panel analysis (i.e. founded upon the premise that consistently, one event happens with priority before the happening of another event) can successfully test causal claims in non-experimental research designs (Huck, Cormier, and Bounds Citation1974; Kearney Citation2017). This analysis allows us to unravel the relative possibility and strength of simultaneous causal variations among two variables measured at different time points (Huck, Cormier, and Bounds Citation1974). Thus, by collecting multiple data waves and using cross-lagged analysis, one can indicate the causal direction between the ACTs and ATAs.

In higher educational settings, cross-lagged panel analysis was used consistently in the past few years (e.g. Paloș, Maricuţoiu, and Costea Citation2019; Schiering, Sorge, and Neumann Citation2021). For example, Paloș, Maricuţoiu, and Costea (Citation2019) used cross-lagged analysis to assess the temporal order of the relationships between student well-being and students’ academic performance. They found students’ grades to be antecedents of their academic well-being. Also, Paloș, Maricuţoiu, and Costea (Citation2019) found that students’ well-being cannot be considered an antecedent of their academic performance. In our case, the information provided by the cross-lagged analysis could bring relevant input on the dynamic relationship between ACTs and ATAs. Specifically, it can inform us on whether there is any causal relationship between conceptions and approaches, whether the conceptions are an antecedent of teaching approaches or vice-versa, or if there is a reciprocal longitudinal causal relationship between them.

The present study

We employed a cross-lagged panel model approach in three waves to assess the following four hypotheses about the causal association between ACTs and ATAs. Complementary, we also checked if the model is influenced by participants’ gender or their teaching responsibilities.

(H1) ACTs and ATAs do not directly influence each other (stability model).

(H2) ACTs have direct and longitudinal effects on ATAs (causal model).

(H3) ATAs have direct and longitudinal effects on ACTs (reversed causal model).

(H4) ACTs and ATAs demonstrate reciprocal and longitudinal effects (reciprocal model).

Method

Participants and procedure

All the academics from one Romanian university who attended an IDP (details of this IDP are presented in the First Supplemental Material) for debutants (PhD student or Assistant lecturer with less than six years of teaching experience) in the academic years of 2020–2021 (N = 92) and 2021–2022 (N = 74) were invited to participate in the current research voluntarily. The current investigation was based on three waves of data collected online using the QuestionPro platform. Time1 (T1) was conducted before the beginning of the program. Five weeks later, just after the end of the first module, Time2 (T2) took place. After another five weeks, just after the second module of the program, Time3 (T3) was conducted. This procedure of data collection has been applied similarly to both cohorts. As presented in the First Supplemental Material, the IDP had four other modules. However, because during the third module of the IDP, the second semester of the academic year debuted and some of our participants could change their teaching responsibilities, we decided not to collect other data for the present study. Thus, all the participants in our study kept their teaching responsibilities status across the three data waves.

In each collecting data moment, we asked participants to refer to their approaches to teaching at one subject they teach at that time or (if they were not currently involved in teaching activities) they will teach the next semester or would like to teach soon. Before the questionnaire completion, participants were informed by a researcher that their participation in the assessment process was voluntary and could withdraw anytime. Also, all the participants gave their informed consent and were informed about the data anonymity. Considering the minimal risk nature of the study (under the World Medical Association Helsinki declaration), no ethical board approval was required.

Out of 166 enrolled participants in the IDP in the two academic years, 154 responded at least once to the questionnaire. Across the three data waves, the answers of 115 debutant academics were successfully matched for the current study. Of those 115 answers, 79 (i.e. 68.70%) were with complete data, while the other 36 academics had one of the data collection time-points missing at random. Thus, as described in , our sample consisted of 115 debutant academics (60.9% female, mean age = 30.59).

Table 1. Sample characteristics (N = 115).

We checked for possible sampling bias due to participant loss by comparing the data in T1 of academics who participated in all three time-points (i.e. N = 79) and those that answered only in the T1 (i.e. N = 129). For this aim, several contextual and demographic characteristics (i.e. academics’ gender and age, class size, teaching responsibilities, teaching experience, and academic status) and all the study variables (i.e. CCSF, ITTF, TC, AAL, and OPP) were used to perform independent t-tests and chi-square analysis. As the results revealed no statistically significant differences, we concluded that there was no significant sampling bias due to the decrease in sample size. The details regarding the sampling bias analysis are presented in the Second Supplemental Material.

Instruments

ATAs were evaluated using the 2-factor R-ATI (i.e. ‘conceptual change/student-focused” - CCSF and ‘information transmission/teacher-focused” - ITTF) made by Trigwell, Prosser, and Ginns (Citation2005). Mladenovici et al. (Citation2022) provided evidence regarding the adaptation of this instrument in the Romanian academic context. Respondents were asked to evaluate each item using a 5-points Likert scale where 1 = never/only rarely true of me and 5 = almost always/always true of me. For the current investigation, the R-ATI demonstrated suitable psychometric properties at each time point (). Also, for both the ITTF and CCSF scales, the mean of inter-item correlation coefficients was above .25.

Table 2. Cronbach’s alpha coefficients of R-ATI and COLT in the three time-point (N = 115).

ACTs were measured with the 3-factor COLT inventory created by Jacobs et al. (Citation2012). COLT contains 18 items divided into three factors: “Teacher centeredness” - TC, “Appreciation of active learning” - AAL, and “Orientation to professional practice” - OPP. Academics were asked to evaluate each item on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree and 5 = strongly agree). As presented in , except for two Cronbach's α at T1 (i.e. α AAL = .60 and α OPP = .62), the COLT displayed good internal consistency in all three-time points. As the COLT inventory was used for the first time in the Romanian academic context, details regarding the adaptation of COLT to the Romanian academic population are presented in the Third Supplemental Material.

Data analysis

Several R packages were employed. First, for the internal validity of the instruments and confirmatory factor analysis of COLT, Rosseel’s (Citation2012) Lavaan package was utilized. Next, to investigate the cross-lagged longitudinal models, structural equation modeling (SEM) with the Lavaan software package was utilized (Rosseel Citation2012). Absolute and relative indices were used to evaluate the goodness-of-fit of the tested models. We presented all the details of the analyzes performed in the Second Supplemental Material.

Results

The descriptive statistics in all the three time points for the R-ATI and COLT inventories are presented in . The pattern of longitudinal and cross-sectional correlations between the measured variables was as stated in the literature (Jacobs et al. Citation2012; Kember and Kwan Citation2000; Trigwell, Prosser, and Ginns Citation2005). Specifically, academics’ student-centered teaching approaches negatively correlated with academics’ teacher-focused approaches and teacher-centered conceptions about teaching. Also, academics’ student-centered teaching approaches were positively related to academics’ student-centered conceptions about teaching both synchronously and longitudinally.

Table 3. Means (M) standard deviations (SD) and zero-order correlations between study variables (for R-ATI and COLT instruments) (N = 115).

Cross-lagged analysis

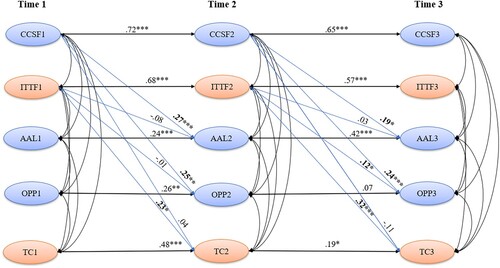

The results for all the four hypothesized structural models are presented in . One by one, the four specified models (i.e. M1 = independent model; M2 = causal model; M3 = reversed causal model; M4 = reciprocal model) were compared. Firstly, M1 was compared to M2. There were no significant improvements in M2 (Δx2 = 14.12, Δdf = 12, p > .05). Secondly, M1 was compared to M3. The results showed that M3 had a more suitable data fit than M1 (Δx2 = 56.17, Δdf = 12, p < .0001). Thirdly, when compared to M1 and M4, M4 provided a better fit for the data. Nevertheless, as compared to M3, the M4 did not significantly enhance the model fit of the data (Δx2 = 11.94, Δdf = 12, p > .05). Hence, the M3 resulted as the most suitable fitting model in terms of parsimony. Thus, our data supported the hypothesis that ATAs influence ACTs.

Table 4. Model fit indexes of both measurement and structural models for R-ATI and COLT (N = 115).

displays the path coefficients of the M3 (i.e. the reversed causal model). Specifically, at Time 2, student-centered teaching approaches (CCSF1) had a longitudinal and positive cross-lagged effect on academics’ student-centered conceptions of teaching (i.e. Appreciation of active learning, AAL2, β = .27, p < .001 and Orientation to professional practice, OPP2, β = .27, p < .01). At Time 3, student-centered teaching approaches (CCSF2) also had a longitudinal positive cross-lagged effect on academics’ student-centered teaching conceptions (i.e. Appreciation of active learning, AAL3, β = .19, p < .001 and Orientation to professional practice, OPP3, β = .24, p < .001). On the other hand, teacher-centered teaching approaches (ITTF) had a positive longitudinal cross-lagged effect on academics’ teacher-centered conceptions (TC) at both Time 2 (β = .23, p < .01) and Time 3 (β = .32, p < .001). Furthermore, at Time 3, teacher-centered approaches of teaching (ITTF2) had a positive longitudinal cross-lagged effect on academics’ student-centered conceptions regarding their orientation to professional practice (OPP3, β = .28, p < .01).

Figure 1. M3. Reversed causal model of cross-lagged relationships between academics’ teaching approaches (Conceptual change / student focused ITTF = Information transmission / teacher focused) and academics’ teaching conceptions (AAL = Appreciation of active learning OPP = Orientation to professional practice and TC = Teacher centeredness) as measured by R-ATI and COLT (N = 115). ***. Correlation is significant at the 0.001 level; **. Correlation is significant at the 0.01 level; *. Correlation is significant at the 0.05 level.

In the case of contextual variables that were relatively proportionally distributed in the dataset, more precisely, the teaching responsibilities (0 = not teaching and 1 = teaching at bachelor level) and academics’ gender variables (1 = female, 2 = male), we performed measurement invariance analysis. With regards to the invariance (i.e. equivalence) of the relationships of the reversed causal model, we found no statistically significant differences between the two versions/models (female vs. male and teaching at bachelor level vs. not teaching) being compared. Specifically, by comparing the fit indices of the metric to the configural invariance model, both in the case of teaching responsibilities (Δx2 [22] = 20.586, p = .55) and academics’ gender (Δx2 [22] = 19.7, p = .60) we found that the final cross-panel model (i.e. ACTs are influenced by ATAs) is invariant. Thus, when it comes to those two variables, with the cautions due to the relatively small sample, we may conclude that weak invariance is supported in our dataset (i.e. there are equal regression coefficients).

Discussion

The current endeavor investigated the longitudinal causal relationship between ACTs and ATAs. As existing evidence did not provide a consistent answer about the direction of the temporal order between ACTs and ATAs, we tested all the possible relations: no causal relationship, ATAs are influenced by ACTs, ACTs are influenced by ATAs, and the reciprocal longitudinal causal relationship between ACTs and ATAs.

The results sustained that both student- and teacher-centered ATAs at an earlier time (e.g. T1 or T2) have had a positive longitudinal cross-lagged effect on student- and teacher-centered ACTs (e.g. T2 or T3). Therefore, ACTs are shaped, in time, by ATAs. Our findings align with a few earlier pieces of research that stressed some cues in this direction (i.e. Guskey Citation1986, Citation2002; Pedrosa-de-Jesus and Lopes Citation2011). At the same time, the present findings oppose most of the literature in the domain, which concluded that meaningful teaching approaches are unlikely to happen without substantial transformations in ACTs (Åkerlind Citation2004; Ho, Watkins, and Kelly Citation2001; Mladenovici et al. Citation2022; Trigwell and Prosser Citation1996). Our study is conducted on debutant academics with limited teaching experience or no teaching experience at all. In contrast, previous studies were mainly conducted on experienced academics. This methodological aspect could explain the divergences between our results and that of the previous studies, as prior research highlighted that academics’ teaching experiences influence ATAs and ACTs (e.g. Postareff, Lindblom-Ylänne, and Nevgi Citation2007; Vilppu et al. Citation2019).

Our results showed that student-centered ATAs at a previous time shape complementary student-centered ACTs. This complementarity is also valid for teacher-centered conceptions and approaches. These results seem to reinforce the findings of previous studies (Kember and Kwan Citation2000) that showed a strong positive correlation (r2 = 89%) between ATAs and ACTs. Besides, from the second to third measurement moment, we found that teacher-centered approaches to teaching (ITTF2) positively predicted a specific type of academics’ student-centered conceptions as measured by the COLT inventory (i.e. orientation to professional practice, OPP3). This relation did not exist at T1 but was only significant in the evolution from T2 to T3. Such a finding could be interpreted as a cue of the evolution of academics’ teacher-centered teaching approaches into dissonant ATAs as an effect of the followed IDP. Postareff and her collaborators (Citation2008) explained the dissonant ATAs as forms of teaching that combine the two main approaches (student-centered and teacher-centered). For example, one may use the transmission of information as the only instructional strategy to help students develop their conceptions of the subject matter. Also, Stes and Van Petegem (Citation2014) presented evidence that the evolution of ATAs from teacher-centered toward student-centered could occur through intermediary steps defined as dissonant ATAs.

Implications for academic development practice

From a practical perspective, our findings could advance suggestions for improving the instructional development practice dedicated to academics. First, the fact that ACTs are influenced by ATAs could suggest that changes in ACTs are possible after the academics observed the positive effects of a teaching method on student learning. For example, in a study presented by Pedrosa-de-Jesus and Lopes Citation2011, academics changed their teaching conceptions after observing the positive effect of using questioning as an instruction method. Hence, academic developers should help university teachers (especially novice teachers) learn specific student-centered teaching methods in conjunction with self-reflective methods. Several good practice models, such as the Strategic alertness model (Entwistle and Walker Citation2000), Reflect upon, name and reframe of conceptions model (Young Citation2008), and Self-awareness process model (Ho, Watkins, and Kelly Citation2001) could be considered.

Second, our results highlighted that the causal relationship between ATAs and ACTs is manifested between similar (student-centered or teacher-centered) but not between different (student-centered and teacher-centered) approaches and conceptions. This finding could explain why several IDPs that aimed to help academics employ student-centered teaching approaches succeeded in stimulating student-centered approaches but did not significantly decrease teacher-centered approaches or vice-versa (Postareff, Lindblom-Ylänne, and Nevgi Citation2008; Stes, Coertjens, and Van Petegem Citation2010). Also, previous studies concluded that it is more difficult to change the teacher-centered approach than the student-centered approach (Prosser and Trigwell Citation1999; Gibbs and Coffey Citation2004; Lindblom-Ylänne et al. Citation2006). Thus, to improve the pedagogical training practices dedicated to university teachers, academic developers should tailor specific instructional activities to address both main objectives separately (i.e. increasing student-centered and decreasing teacher-centered approaches). Also, academic developers should consider the design of specific learning tasks that help academics distinguish between the two main approaches and conceptions more effectively. Cassidy and Ahmad (Citation2021) also advanced a similar suggestion in a recent paper.

Limitations and implications for future research

Some limitations of this study emphasize the necessity to take the results with caution and thus should be discussed. First, previous research highlighted that changes in ACTs and ATAs could differ depending on the academics’ teaching experiences (e.g. Postareff, Lindblom-Ylänne, and Nevgi Citation2007; Postareff et al. Citation2008; Vilppu et al. Citation2019). For example, changes in debutant ACTs might be more manageable as they do not have highly developed expertise in their fields (Vilppu et al. Citation2019), while modifying conceptions among more experienced academics may be a significant challenge (Postareff and Nevgi Citation2015; Vilppu et al. Citation2019). Therefore, the findings of the present study should be interpreted concerning only a sample of debutant academics. Thus, future studies should design, implement, and measure the dynamic relationship between ACTs and ATAs, targeting more experienced academics. Second, we should be aware that data were collected during the period the responders followed an IDP. Thus, replicating the current research in a natural teaching context, not in a training context, would be of great importance. Third, conducting randomized controlled trials or at least quasi-experimental studies is paramount to interpreting the relationship between ATAs and ACTs in a more causal key. Fourth, given that we have collected self-reported data, we should be aware that academics may have undertaken ‘socially desirable’ behaviors while filling in the questionnaires. Therefore, more eclectic data gathering techniques, more participants and time points for data collection would be worthwhile.

Fifth, to assess ACTs and ATAs, we used two inventories with limited variability (3-factor COLT, Jacobs et al. Citation2012, and 2-factor R-ATI, Trigwell, Prosser, and Ginns Citation2005). However, some previous studies presented that there may be more variability in the ATAs and ACTs. For example, Trigwell, Prosser, and Taylor (Citation1994) and Postareff et al. (Citation2008) identified five teaching approaches and Kember (Citation1997) defined five categories of teaching conceptions. Hence, future studies must ensure greater variability when having the intention to measure the academics’ conceptions and approaches to teaching. Thus, one can use different instruments to assess ATAs (e.g. the 5-factor R-ATI as validated by Stes, De Maeyer, and Van Petegem Citation2010 and/or the Higher Education Teachers’ Approaches to Teaching - HEAT, Parpala and Postareff Citation2022) and ACTs (e.g. Questionnaire of Conceptions about Teaching – QCAT, Perez-Villalobos et al. Citation2019).

Finally, a significant limitation of the longitudinal designs is the impossibility of excluding specific associations due to variables that were not measured in the study design (Taris and Kompier Citation2014). We found that the relationships of the reversed causal model (i.e. ATAs have a cross-lagged longitudinal effect on ACTs) are consistent regardless of whether having taught a subject (or not) and gender. However, there may be other influencing aspects such as contextual and work environment characteristics, personal goals, psychological resources, etc. Also, we must be aware of the relatively small statistical power of the present study. Furthermore, our choice of time lags between the waves (i.e. five weeks) could have affected the results because the anticipated effect may need more time to emerge (Taris and Kompier Citation2014). As there is limited longitudinal evidence on the relationship between ACTs and ATAs, future studies could gather data by considering long time lags (e.g. nine or twelve weeks). However, caution must be paid as the predicted effect may decrease or disappear when the time lags are too lengthy (Taris and Kompier Citation2014). We hope that future studies will use different time lags and thus offer us the possibility to reveal the optimal time lag to evaluate the dynamic of ACTs and ATAs (i.e. by comparing findings from studies with different time lags between waves).

Conclusion

The current research is the first to address the dynamic relation between ACTs and ATAs, using a three-wave cross-lagged panel model approach. The results supported the longitudinal causal model in which ATAs had a cross-lagged longitudinal effect on ACTs in the case of debutant academics. Also, there is a consistent complementarity between student-centered and teacher-centered teaching approaches and conceptions. The results could be used to develop pedagogical initiatives dedicated at least to academics at the beginning of their career.

Supplemental Material

Download Zip (1.1 MB)Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Åkerlind G. S. 2004. “A new Dimension to Understanding University Teaching.” Teaching in Higher Education 9 (3): 363–75. doi:10.1080/1356251042000216679.

- Asikainen H. and D. Gijbels. 2017. “Do Students Develop Towards More Deep Approaches to Learning During Studies? A Systematic Review on the Development of Students’ Deep and Surface Approaches to Learning in Higher Education.” Educational Psychology Review 29 (2): 205–34. doi:10.1007/s10648-017-9406-6.

- Becher T. 1989. Academic Tribes and Territories: Intellectual Enquiry and the Cultures of Disciplines. Bristol PA: The Society for Research into Higher Education and Open University Press.

- Cassidy R. and A. Ahmad. 2021. “Evidence for Conceptual Change in Approaches to Teaching.” Teaching in Higher Education 26 (5): 742–58. doi:10.1080/13562517.2019.1680537.

- Eley M. G. 2006. “Teachers’ Conceptions of Teaching and the Making of Specific Decisions in Planning to Teach.” Higher Education 51 (2): 191–214. doi:10.1007/s10734-004-6382-9.

- Emery N. C. J. M. Maher and D. Ebert-May. 2020. “Early-career Faculty Practice Learner-Centered Teaching up to 9 Years After Postdoctoral Professional Development.” Science Advances 6 (6): 1–10. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aba2091.

- Entwistle N. 2009. Teaching for Understanding at University. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Entwistle N. D. Skinner D. Entwistle and S. Orr. 2000. “Conceptions and Beliefs About “Good Teaching”: An Integration of Contrasting Research Areas.” Higher Education Research & Development 19 (1): 5–26. doi:10.1080/07294360050020444.

- Entwistle N. and P. Walker. 2000. “Strategic Awareness within Sophisticated Conceptions of Teaching.” Instructional Science 28: 335–61. doi:10.1023/A:1026579005505.

- Gibbs G. and M. Coffey. 2004. “The Impact of Training of University Teachers on Their Teaching Skills Their Approach to Teaching and the Approach to Learning of Their Students.” Active Learning in Higher Education 5 (1): 87–100. doi:10.1177/1469787404040463.

- Guskey T. R. 1986. “Staff Development and the Process of Teacher Change.” Educational Researcher 15 (5): 5–12. doi:10.3102/0013189X015005005.

- Guskey T. R. 2002. “Professional Development and Teacher Change.” Teachers and Teaching 8 (3): 381–91. doi:10.1080/135406002100000512.

- Ho A. D. Watkins and M. Kelly. 2001. “The Conceptual Change Approach to Improving Teaching and Learning: An Evaluation of a Hong Kong Staff Development Programme.” Higher Education 42 (2): 143–69. doi:10.1023/A:1017546216800.

- Huck S. W. W. H. Cormier and W. G. Bounds. 1974. Reading Statistics and Research. New York: Harper and Row.

- Ilie M. D. L. P. Maricuțoiu D. E. Iancu I. G. Smarandache V. Mladenovici D. C. M. Stoia and S. A. Toth. 2020. “Reviewing the Research on Instructional Development Programs for Academics. Trying to Tell a Different Story: A Meta-Analysis.” Educational Research Review 30: 100331. doi:10.1016/j.edurev.2020.100331.

- Jacobs J. C. S. J. Van Luijk H. Van Berkel C. P. Van der Vleuten G. Croiset and F. Scheele. 2012. “Development of an Instrument (The COLT) to Measure Conceptions on Learning and Teaching of Teachers in Student-Centred Medical Education.” Medical Teacher 34 (7): e483–e491. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2012.668630.

- Kaasila R. S. Lutovac J. Komulainen and M. Maikkola. 2021. “From Fragmented Toward Relational Academic Teacher Identity: The Role of Research-Teaching Nexus.” Higher Education 82 (3): 583–98. doi:10.1007/s10734-020-00670-8.

- Kearney M. W.. 2017. “Cross Lagged Panel Analysis.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Communication Research Methods, edited by Mike Allen, 312–14. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Kember D. 1997. “A Reconceptualisation of the Research into University Academics’ Conceptions of Teaching.” Learning and Instruction 7 (3): 255–75. doi:10.1016/S0959-4752(96)00028-X.

- Kember D. 2009. “Promoting Student-Centred Forms of Learning Across an Entire University.” Higher Education 58 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1007/s10734-008-9177-6.

- Kember D. and K. P. Kwan. 2000. “Lecturers’ Approaches to Teaching and Their Relationship to Conceptions of Good Teaching.” Instructional Science 28 (5): 469–90. doi:10.1023/A:1026569608656.

- Lindblom-Ylänne S. K. Trigwell A. Nevgi and P. Ashwin. 2006. “How Approaches to Teaching are Affected by Discipline and Teaching Context.” Studies in Higher Education 31 (3): 285–98. doi:10.1080/03075070600680539.

- McMinn M. M. Dickson and S. Areepattamannil. 2022. “Reported Pedagogical Practices of Faculty in Higher Education in the UAE.” Higher Education 83: 395–410. doi:10.1007/s10734-020-00663-7.

- Mladenovici V. M. D. Ilie L. P. Maricuțoiu and D. E. Iancu. 2022. “Approaches to Teaching in Higher Education: The Perspective of Network Analysis Using the Revised Approaches to Teaching Inventory.” Higher Education 84: 255–77. doi:10.1007/s10734-021-00766-9.

- Norton L. T. E. Richardson J. Hartley S. Newstead and J. Mayes. 2005. “Teachers’ Beliefs and Intentions Concerning Teaching in Higher Education.” Higher Education 50 (4): 537–71. doi:10.1007/s10734-004-6363-z.

- Paloș R. L. P. Maricuţoiu and I. Costea. 2019. “Relations Between Academic Performance Student Engagement and Student Burnout: A Cross-Lagged Analysis of a two-Wave Study.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 60: 199–204. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2019.01.005.

- Parpala A. and L. Postareff. 2022. “Supporting High-Quality Teaching in Higher Education Through the HowUTeach Self-Reflection Tool.” Ammattikasvatuksen Aikakauskirja 23 (4): 61–67. doi:10.54329/akakk.113327.

- Pedrosa-de-Jesus M. H. and B. S. Lopes. 2011. “The Relationship Between Teaching and Learning Conceptions Preferred Teaching Approaches and Questioning Practices.” Research Papers in Education 26 (2): 223–43. doi:10.1080/02671522.2011.561980.

- Peeraer G. V. Donche B. Y. De Winter A. M. M. Muijtjens R. Remmen P. Van Petegem L. Bossaert et al. 2011. “Teaching Conceptions and Approaches to Teaching of Medical School Faculty: The Difference Between how Medical School Teachers Think About Teaching and how they say That They Do Teach.” Medical Teacher 33 (7): e382–e387. doi:10.3109/0142159X.2011.579199.

- Perez-Villalobos C. E. N. Bastias-Vega G. K. Vaccarezza-Garrido R. Glaria-Lopez C. Aguilar-Aguilar and P. Lagos-Rebolledo. 2019. “Questionnaire on Conceptions about Teaching: Factorial Structure and Reliability in Academics of Health Careers in Chile.” JPMA. The Journal of the Pakistan Medical Association 69: 355–60.

- Postareff L. N. Katajavuori S. Lindblom-Ylänne and K. Trigwell. 2008a. “Consonance and Dissonance in Descriptions of Teaching of University Teachers.” Studies in Higher Education 33 (1): 49–61. doi:10.1080/03075070701794809.

- Postareff L. and S. Lindblom-Ylänne. 2008. “Variation in Teachers’ Descriptions of Teaching: Broadening the Understanding of Teaching in Higher Education.” Learning and Instruction 18 (2): 109–20. doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2007.01.008.

- Postareff L. S. Lindblom-Ylänne and A. Nevgi. 2007. “The Effect of Pedagogical Training on Teaching in Higher Education.” Teaching and Teacher Education 23 (5): 557–71. doi:10.1016/j.tate.2006.11.013.

- Postareff L. S. Lindblom-Ylänne and A. Nevgi. 2008b. “A Follow-up Study of the Effect of Pedagogical Training on Teaching in Higher Education.” Higher Education 56 (1): 29–43. doi:10.1007/s10734-007-9087-z.

- Postareff L. and A. Nevgi. 2015. “Development Paths of University Teachers During a Pedagogical Development Course.” Educar 51 (1): 37–52. http://hdl.handle.net/11162/113818.

- Pratt D. D. 1992. “Conceptions of Teaching.” Adult Education Quarterly 42 (4): 203–20. doi:10.1177/074171369204200401.

- Prosser M. and K. Trigwell. 1999. “Relational Perspectives on Higher Education Teaching and Learning in the Sciences.” Studies in Science Education 33 (1): 31–60. doi:10.1080/03057269908560135.

- Prosser M. and K. Trigwell. 2014. “Qualitative Variation in Approaches to University Teaching and Learning in Large First-Year Classes.” Higher Education 67 (6): 783–95. doi:10.1007/s10734-013-9690-0.

- Prosser M. K. Trigwell and P. Taylor. 1994. “A Phenomenographic Study of Academics’ Conceptions of Science Learning and Teaching.” Learning and Instruction 4 (3): 217–31. doi:10.1016/0959-4752(94)90024-8.

- Rosseel Y. 2012. “Lavaan: An R Package for Structural Equation Modeling.” Journal of Statistical Software 48 (2): 1–36. doi:10.18637/jss.v048.i02.

- Sadler I. 2012. “The Challenges for new Academics in Adopting Student-Centred Approaches to Teaching.” Studies in Higher Education 37 (6): 731–45. doi:10.1080/03075079.2010.543968.

- Samuelowicz K. and J. D. Bain. 1992. “Conceptions of Teaching Held by Academic Teachers.” Higher Education 24 (1): 93–111. doi:10.1007/BF00138620.

- Samuelowicz K. and J. D. Bain. 2001. “Revisiting Academics’ Beliefs About Teaching and Learning.” Higher Education 41 (3): 299–325. doi:10.1023/A:1004130031247.

- Saroyan A. and K. Trigwell. 2015. “Higher Education Teachers’ Professional Learning: Process and Outcome.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 46: 92–101. doi:10.1016/j.stueduc.2015.03.008.

- Schiering D. S. Sorge and K. Neumann. 2021. “Promoting Progression in Higher Education Teacher Training: How Does Cognitive Support Enhance Student Physics Teachers’ Content Knowledge Development?” Studies in Higher Education 46 (10): 2022–34. doi:10.1080/03075079.2021.1953337.

- Stes A. L. Coertjens and P. Van Petegem. 2010a. “Instructional Development for Teachers in Higher Education: Impact on Teaching Approach.” Higher Education 60 (2): 187–204. doi:10.1007/s10734-009-9294-x.

- Stes A. S. De Maeyer and P. Van Petegem. 2010b. “Approaches to Teaching in Higher Education: Validation of a Dutch Version of the Approaches to Teaching Inventory.” Learning Environments Research 13 (1): 59–73. doi:10.1007/s10984-009-9066-7.

- Stes A. and P. Van Petegem. 2014. “Profiling Approaches to Teaching in Higher Education: A Cluster-Analytic Study.” Studies in Higher Education 39 (4): 644–58. doi:10.1080/03075079.2012.729032.

- Taris T. W. and M. A. J. Kompier. 2014. “Cause and Effect: Optimizing the Designs of Longitudinal Studies in Occupational Health Psychology.” Work & Stress 28 (1): 1–8. doi:10.1080/02678373.2014.878494.

- Trigwell K. and M. Prosser. 1996. “Congruence Between Intention and Strategy in University Science Teachers’ Approaches to Teaching.” Higher Education 32 (1): 77–87. doi:10.1007/BF00139219.

- Trigwell K. M. Prosser and P. Ginns. 2005. “Phenomenographic Pedagogy and a Revised Approaches to Teaching Inventory.” Higher Education Research & Development 24 (4): 349–60. doi:10.1080/07294360500284730.

- Trigwell K. M. Prosser and P. Taylor. 1994. “Qualitative Differences in Approaches to Teaching First Year University Science.” Higher Education 27 (1): 75–84. doi:10.1007/BF01383761.

- Uiboleht K. M. Karm and L. Postareff. 2018. “The Interplay Between Teachers’ Approaches to Teaching Students’ Approaches to Learning and Learning Outcomes: A Qualitative Multi-Case Study.” Learning Environments Research 21 (3): 321–47. doi:10.1007/s10984-018-9257-1.

- Vilppu H. I. Södervik L. Postareff and M. Murtonen. 2019. “The Effect of Short Online Pedagogical Training on University Teachers’ Interpretations of Teaching–Learning Situations.” Instructional Science 47 (6): 679–709. doi:10.1007/s11251-019-09496-z.

- Young S. F. 2008. “Theoretical Frameworks and Models of Learning: Tools for Developing Conceptions of Teaching and Learning.” International Journal for Academic Development 13 (1): 41–49. doi:10.1080/13601440701860243.