ABSTRACT

This article examines the predictors of gender-specific literature production in the field of social sciences and humanities (SSH). The research used bibliometric information on 1132 gender-related articles by authors with Romanian affiliations. Binary logistic regression shows the individual and institutional factors of a paper’s likelihood of including gender-related words in its title. Weak institutionalisation of Gender Studies marks this national context, reflected in the marginal and discontinuous integration in the curriculum of higher-education institutions. Our findings suggest that the female gender of the first or a single author, as well as the authors’ affiliation with Romanian universities running master’s programmes in Gender Studies, are positively associated with the outcome variable. Likewise, single-author articles have greater odds than co-authored articles of including a reference to gender in their titles. Conversely, articles published in journals in the JIF third quartile of the JCR hierarchy have less chance of having a title that conveys an orientation towards gender-specific research. The implications of our findings suggest that the decision-makers at the level of faculties and research institutes in SSH must focus on creating a facilitating environment for scholarly interest in feminist research. We propose tackling the negative stereotypes regarding feminism’s ideological underpinnings and its ostensible lack of epistemological foundation. Romania is a country still facing significant domestic violence and poor gender equality, so these findings have further implications at the societal level.

Introduction

The worldwide academic literature dealing with gender and feminist issues has grown steadily during the past three decades, despite the uneven distribution of its growth across countries and regions. A simple search in the Web of Science (WOS) core collection, using ‘gender’ as a keyword in the ‘topic’ field, showed that the United States accounted for more than one-third of the 744,622 documents containing gender in their title, abstract or keywords. More prolific European countries in this respect are England (8% of the total), Germany (5%) and southern European countries, such as Spain (3.9%) and Italy (3.4%). Central and Eastern European (CEE) countries lag behind in the contribution of published gender-related research indexed in WOS. Poland (1%) and the Czech Republic (0.5%) are the best performers in the region; Romania barely reaches 0.4% of the global literature on this topic. Social practices sustaining specific power structures embedded in each research field (Bourdieu Citation1983) both shape and constitute the production of scientific literature. By scrutinising ideological underpinnings, scientists play an important role in shaping societies’ understanding and challenging some established categories of knowledge. Gender research in medicine and researchers’ growing concern for the gender-specific body reflect the lay public’s demands for research-based evidence confirming cultural stereotypes about men’s and women’s distinct characteristics and their different medical healthcare needs. Such evidence would also fit into neoliberal pursuits of market solutions to growing gender-specific needs in healthcare services and pharmaceutics (Annandale and Hammarström Citation2011). Therefore, the production of knowledge in a research field requires thorough investigation to understand which individual, institutional and structural factors shape scientists’ research interests. Researchers are actors simultaneously embedded in various power relations operating within the academic field and, thus, nested within broader social, political, economic and cultural structures. Such embedment has consequences for scientists’ decisions in selecting research topics and their approach to studying them. Scientific fields are marked by inequalities and hierarchies of various forms of capital that become institutionalised through historical reproduction of relations between actors activating in those fields, while struggles to transform the structure of scientific fields are sometimes contributing to institutional changes (Kloot Citation2009; Rowlands Citation2013). Research evidence from various national contexts reports academics’ struggles and their ‘ambivalent optimism’ regarding recognising the value of feminist research and the implementation of gender mainstreaming in degree and study programme syllabi. This is attributable to corporate managers’ criticism of enterprise-like higher education and research institutions, mass media’s bad press, politicians’ attacks and the backlash on gender mainstreaming. (Baird Citation2010; Kitta and Cardona-Moltó Citation2022; Millar Citation2021). Such adverse attitudes are common in the Romanian context as well, while some efforts to counteract their impact are currently well represented by the initiatives of the Coalition for Gender Equality consisting of 15 civic organisations active in awareness-raising campaigns for gender equality. Building on collaboration with representatives of national authorities, academics and other stakeholders, this coalition has recently started a campaign coined ‘Feminism for all’ in schools, in order to debunk myths about feminism, and proposed a manual for gender equality whose aim is to support teachers in properly addressing gender inequalities in schools. Although these initiatives sometimes face opposition, they remain a crucial factor for changing mindsets and paving the way for more inclusive study programmes across higher education. As Millar (Citation2021) rightly argues, the value of Gender Studies programmes is both epistemological and moral. Students’ exposure to such content endows them with critical thinking they need to deconstruct the power inequalities that cause different forms of oppression. In addition, it raises students’ awareness of the importance of collectively engaging in eradicating discrimination against gender, sexual, ethnic and other minorities.

The production of scientific articles on gender-related issues in SSH may be a rude indicator of the degree of Gender Studies institutionalisation. It taps into the academics’ preoccupation with answering specific research questions arising from the reflexive work that those in various institutional contexts have undertaken, favouring the exchange of ideas related to feminism. The growing body of gender-specific scholarly literature by Romanian academics in SSH can appear as an indication of the achievement of more mature stages of feminist thought inside and outside of academia. They occur in a national context of disruptive changes accompanying political transformations during the communist regime and the unsteady academic reforms after communism’s fall in 1989. This article reports on a logistic regression run on bibliometric data from 1132 SSH articles by Romanian academics indexed in WOS. We aim to shed light on the likelihood that the article’s title including gender-specific words relates to individual and institutional factors, such as the gender of the first author, single versus multiple authorship, the presence of masters-level Gender Studies in affiliated institutions, and the journal’s position within the Journal Citation Report (JCR) ranking in Journal Impact Factor (JIF) quartiles. Thus, this article seeks to answer the following research questions: (1) What are the main drivers of the production of gender-specific papers by Romanian scholars? (2) What could stimulate the production of valuable feminist research in SSH in the context of weak institutionalisation of Gender Studies? (3) What policy implications does the present study produce with respect to the mainstreaming of gender in Romanian higher education and its societal spillover? Such findings are helpful in understanding the contribution of the research to the debate on gender equality in Romania, whose developments regarding women’s rights instantiate a situation of contradictory achievements (Juhálsz and Pap Citation2018).

The article proceeds as follows. An overview of the post-socialist developments in the institutionalisation of Gender Studies in Romanian higher education acknowledges the domestic and international structural forces shaping this process. Then, we present data, methods and the description of the main findings of the regression analysis. The article discusses these findings by drawing on research evidence from feminist literature. Structural and contextual aspects facilitating or opposing feminist developments in the recent decades across different European countries, including Romania, also frame the interpretation of the regression findings. Finally, the article provides concluding remarks and outlines the limitations of this study, then formulates suggestions for future studies that document the production of gender-specific publications in post-communist settings with low institutionalisation of Gender Studies in higher education.

Context-specific factors framing the institutionalisation of Gender Studies in Romanian higher education

Several scholars during the last three decades have addressed the precarious institutionalisation of Gender Studies in Romania and in other post-communist countries of Central and Eastern Europe (CEE) (Băluță Citation2020; Cîrstocea Citation2010; Văcărescu Citation2011; Zimmermann Citation2008). The circumstances that led to such a fragile and uneven inclusion of Gender Studies in research and in the academic curriculum of both private and public higher-education institutions in Romania relate to the broader social, economic and political changes and educational reforms that took place during the post-socialist period. Prior to 1990, this field of study and research had been relegated to the irrelevant or, at best, considered a subordinate topic among the class issues under the dominant ideological worldview of Marxist socialism. Thereafter, under the influence of incremental institutional changes, gender gradually became a legitimate category of inquiry. Zimmermann (Citation2008) identified three chronological sequences in the process of including Gender Studies in academic research across the CEE countries and post-Soviet states. The first started outside academia, initiated by such renowned academics as professors Mihaela Miroiu (National School of Political and Administrative Science) and Laura Grünberg (University of Bucharest), who founded a nongovernmental organisation they named AnA in 1992. Its goal was to advance feminist issues on the political agenda when they were absent from the public space and Romania’s political discourse (Hașdeu Citation2004).

The second stage in the institutionalisation of Gender Studies in Romania built on the parallel developments. On the one hand, private higher-education institutions launched independent university programmes in Gender Studies through the international support that American and Anglo-Saxon donors, such as the Open Society Institute and the MacArthur Foundation, provided. On the other hand, public higher-education institutions introduced modules, classes and postgraduate programmes in main university centres in Bucharest, Cluj-Napoca and Timișoara (Văcărescu Citation2011; Zimmermann Citation2008). The enabling circumstances for the fulfilment of this second stage of the institutionalisation of Gender Studies in the academic realm consisted not only of the financial support and outreach activities that international NGOs organised but also facilitation by the liberal turn of education policy reforms in Romania, resulting in more flexibility and autonomy for higher-education institutions. As a result of this increased autonomy, universities acquired the freedom to add gender-specific courses and introduce Gender Studies programmes not subject to ministerial control. In this context, some dedicated postgraduate programmes launched in 1998, with the introduction of the master’s programme in Gender Studies by the National School of Political and Administrative Science (NSPAS) in Bucharest. Similar programmes followed, run by Babeș-Bolyai University from Cluj-Napoca, the West University in Timişoara and the University of Bucharest. The introduction of such programmes greatly benefitted from international academic recognition and the influential managerial positions of their initiators (Văcărescu Citation2011). This overreliance on the personal capacities and professional ties of some individual academics, who paved the way for the institutionalisation of Gender Studies in Romania, represented both a strength and a weakness, according to Mihaela Miroiu, former Dean of the Faculty of Political Science of the NSPAS. In her view, this heavy influence of entrusted gender scholars enjoying temporary political support from the elected decision-makers of higher-education institutions sometimes facilitated the quick introduction of gender courses and dedicated study programmes in those universities. However, it also threatened the legitimacy of Gender Studies in the long run. In the absence of a solid epistemic community comprising national professional networks and more impersonal rules governing the mainstreaming of Gender Studies in the Romanian academic realm, the introduction and maintenance of such study programmes was contingent on personal affinities and changing local managerial landscapes.

Finally, another influence ‘from above’ that came along with the EU-isation process, marking a shift from the American hegemonic influence of the prior stages that Zimmermann (Citation2008) had described, drove the third stage of the institutionalisation of Gender Studies. This EU-isation that started at the turn of the millennium consisted of two interrelated developments. On the one hand, the Bologna declaration (1999) led to increased standardisation of higher education across Europe, aiming to facilitate the mobility of students and the formal recognition of their studies abroad. On the other hand, the EU requirements to meet the conditions of democracy and human rights, including gender equality so CEE countries could gain EU membership, triggered EU-isation. As a result, Zimmermann (Citation2008, 151) stated:

As the accession process and then membership in the EU became a fact, a mixture of indifferent tolerance and persistent ignorance towards women’s and Gender Studies became the norm in higher education. Open dismissal of Gender Studies per se as ‘foreign’, ‘liberal’, or ‘western’ is now in most countries to be found only among the ranks of right wing and occasionally left wing populism.

Since 2010, a manifest hostility toward gender equality and gender studies has been apparent, while reports have spread of sustained antigender attacks in Romania and other CEE countries, and beyond (Antić and Radačić Citation2020; Brodeală and Epure Citation2022; Juhálsz and Pap Citation2018; Kuhar and Paternotte Citation2017; Norocel Citation2018). Both state policies and public education systems have echoed this backlash against gender equality and mainstreaming. For instance, in Romania, in the summer of 2020, a legislative proposal intended to introduce a ban on organisations providing education and/or professional training, including those entities providing extracurricular education undertaking activities with gender-theory content. Upon the request for a constitutional review by Romanian President Klaus Iohannis, the ban on the use of the gender lens in education and research was eventually declared unconstitutional (Brodeală and Epure Citation2022). These contradictory trends over the past three decades, regarding the institutionalisation of Gender Studies in Romanian higher education, indicate volatile achievements that require approaching cautiously:

Some progress has been made on the formal recognition of Gender Studies and professional expertise in this field. The number of publications and teachers with expertise in or using concepts in the field of Gender Studies has increased. However, there are no definite indicators for a sustainable institutionalization, and the example of master's programs is symptomatic. Too often, the introduction of these courses and the creation of study programs / centres is linked to one person. In the absence of a solid institutionalization leading to the formation of didactical and research teams and open access to stable material resources, these opportunities may disappear, and the programs may close down, as it happened in the case of the two masters in Gender Studies in Cluj-Napoca and Timișoara. (Băluță Citation2020, 37)

Data, method and hypotheses

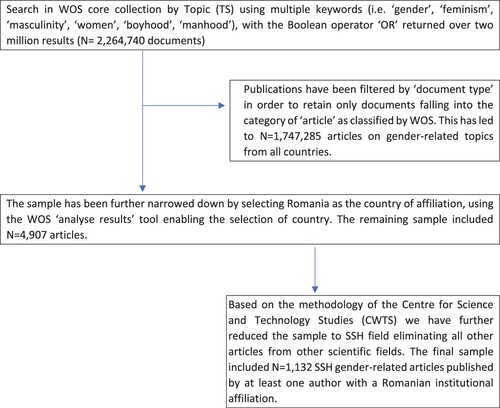

The data used for the present analysis are retrieved from WOS core collection, the largest database compiling bibliometric information on more than 70,000,000 documents covering 254 subject categories from about 150 research areas. Although researchers from SSH have traditionally published in journals indexed in other platforms, WOS core collection has gradually indexed some of these journals, while a number of relevant publications are still not included in this journal database. In spite of this limitation, WOS core collection still remains one of the most comprehensive and reliable source of information for conducting bibliometric studies on various scientific fields, including SSH (Donthu et al. Citation2021; Vlase and Lähdesmäki Citation2023). The WOS search using multiple keywords (i.e. ‘gender’, ‘feminism’, ‘masculinity’, ‘women’, ‘boyhood’, ‘manhood’), with the Boolean operator ‘OR’ linking the Topic fields, returned over two million results. Of those, we selected only those classified as ‘article’, filtering out all other document types using the available WOS options. This led to n = 1,747,285 articles on gender-related topics from all countries. Subsequently, we narrowed the search results by selecting Romania as the country of affiliation, using the WOS ‘analyse results’ tool and producing 4907 articles. Finally, following the Centre for Science and Technology Studies (CWTS) methodologyFootnote2 enabled assigning each publication to one of five main scientific fields (i.e. Biomedical and health sciences, Life and earth sciences, Mathematics and computer science, Physical sciences and engineering, SSH), based on the journal’s subject category. We retained for the present study only the articles that journals belonging to SSH published. The selection procedure described above is visually represented in . No criterion has been applied regarding the articles’ language, but the majority of them are in English (96%), followed by French (1.6%), Spanish (0.6%) German (0.5%) and some additional others, such as Italian, Portuguese and Russian, which are very marginally represented in the sample. Regarding the contribution of scholars by institutions of affiliation, the most productive Romanian universities with respect to the number of gender-related articles are Babeș-Bolyai University from Cluj-Napoca (24.2% of the total number of articles) Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, from Iași, (11.4%) and University of Bucharest (11%) while among those contributing the least we can mention Petre Andrei University from Iași and the National Scientific Research Institute for Labour and Social Protection based in Bucharest, each with only one published gender-related article. Concerning the collaboration patterns, 407 articles (about 36% of the total sample) contain at least one foreign institutional affiliation mainly from the U.S. (12% of the total sample), followed by Italy (7.3%), Germany (7.1%) and England (6.8%). Collaborations between scholars with institutional affiliations based in Romania are also common. Most productive institutions such as Babeș-Bolyai University from Cluj-Napoca collaborate with researchers from 26 different Romanian institutions, including The Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Lucian Blaga University of Sibiu, and The Romanian Academy of Sciences, among others, while Alexandru Ioan Cuza University, from Iași, has collaborative ties of co-authorship with 21 other Romanian institutions (e.g. The Bucharest University of Economic Studies, Ștefan cel Mare University of Suceava, The Romanian Academy of Sciences and The West University in Timişoara).

Figure 1. Steps of the selection procedure of gender-related articles from WoS database. Note: Authors’ selection procedure using WOS ‘analyze results’ tools combined with CWTS methods of collapsing 4159 micro-level fields into five main scientific fields.

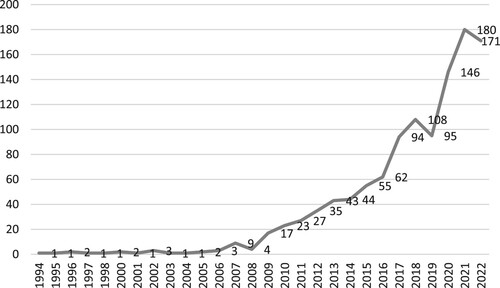

Therefore, the final dataset contained full bibliographic information on 1132 WOS-indexed articles dealing with the topic ‘gender’ and published by at least one author with a Romanian institutional affiliation. We saved these data in the marked lists of the WOS platform, then downloaded them into Excel and also exported them to the Incites Benchmarking & Analytics. Using SPSS 22 software, we ran a logistic regression analysis to determine the factors associated with the presence of explicit references to gender or feminism in the title of the article, our dependent variable. Arguably, the use of such words as ‘gender’, ‘sex’, ‘men’, ‘women’, ‘boys’, ‘girls’, ‘feminism’, ‘queer’ and derivatives of some of those words (e.g. sexism, intersexual, transsexual, homosexual, masculinity, emasculated, women or femininity) is a salient marker of authors’ engagement with gender and feminist studies, as opposed to loose references to gender in abstracts or keywords. To provide insights into the organisational (i.e. institutionalisation of Gender Studies in Romanian organisations of higher education) and author-related characteristics, our independent variables included female gender of the first or single author as a dummy variable (1 = yes, 0 = no) and single-authored article (1 = yes, 0 = no); a categorical variable based on the impact of the journal that its JIF quartile reflected (i.e. a 5-point scale measuring sampled articles’ quartile assignment), using 1 = first quartile (Q1), 2 = second quartile (Q2), 3 = third quartile (Q3), 4 = fourth quartile (Q4), 5 = not applicable. We added this information based on the data that Incites Benchmarking & Analytics reported, using the WOS imported list of bibliometric information related to our sample of articles. In addition, our regression model uses a continuous measure of the number of years since the article has been published, taking values from 0 (articles published in 2022 and indexed in WOS by 19 November 2022, the date of data retrieval) to 28, since the earliest article identified in the dataset was published in 1994. provides a visual representation of the growth of these publications’ volume between 1994 and 2022. However, the bulk of the sample (i.e. 61.8% of the total) had been published in the last five years. Finally, we created one more dummy variable to indicate whether the paper had at least one author affiliated with one of the four higher-education institutions in Romania with a higher degree of institutionalisation of Gender Studies in their current or past master’s degree programme in Gender Studies (i.e. 1 = affiliation to one of the following: University of Bucharest, NSPAS, University of Babes-Bolyai, West University in Timişoara; and 0 = otherwise).

Figure 2. Number of gender-related articles by publication year (1994–2022). Source: Authors based on Web of Science selection of articles published in WOS journals from SSH domain. Data retrieved on 19 November 2022. N = 1132 articles.

presents the descriptive statistics of the indicators we included in the logistic regression to find which predictors explained papers’ explicit engagement with the gender issues, evident in the binary measure of the presence or absence of gender-related words in the title. Article titles usually condense the discussion of the papers’ results, the key concepts and the theoretical approaches. As such, they represent the most important aspect of enticing audience engagement with the paper (Tullu Citation2019). Articles using a gender lens or feminism as a central approach or those that find significant gender differences in their analysis are reasonably likely to include references to these concepts not only in their abstracts or keywords but also in the title. Of the 1132 articles from SSH that we retained for this analysis, only 316 (28%) papers do have a title containing gender-related words.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics of the variables included in the regression

Guided by the rational actor theory, we expect that academics seek publication outlets that increase their opportunities for upward mobility, namely high-impact journals (i.e. JIF first and second quartiles) assessed as valuable for career promotion in the current national system of research and higher education. Likewise, high-impact journals ostensibly provide researchers with opportunities to connect with a wider audience and, therefore, could become a means of raising one’s visibility in an increasingly networked science. This may eventually transform the sceptical attitude towards the field of Gender Studies, in a country that political and cultural conservatism characterises. This leads to formulating our hypotheses:

(H1) Papers published in journals that JCR classification situates in top quartiles are more likely to use gender-related words in their title.

(H2) The more recent the paper, the greater is the likelihood that the paper’s title contains ‘gender’ or similar words.

One peculiar aspect of the SSH field is that unlike other scientific fields, scholars tend to publish individually or in small groups. This could narrow the scope of idea exchanges and cross-fertilisation of research topics, due to limited national or international collaboration. Such collaboration is consequential for the transformation of the micropolitics governing researchers’ propensity to adopt feminist epistemologies and deeply engage with gender in their research. We posit:

(H3) Single-authored articles have less chance than co-authored articles of including in their title ‘gender’ or gender-related words.

(H4) If a paper’s first or single author is a woman, the paper is more likely than other authorship patterns to explicitly mention gender or feminism in its title.

(H5) A paper with at least one author affiliated with one of the four Romanian universities having institutionalised Gender Studies has a greater chance of its title explicitly addressing gender.

Findings

We studied the production of gender-specific scholarly literature by measuring explicit references to gender, sex, women, feminism and other similar words in the title of the paper. Our regression analysis seeks to unpack the effects of institutional and individual factors on the propensity of articles by Romanian-affiliated scholars on gender topics to meaningfully engage with this research. shows the unstandardised coefficients and odds ratios for the dependent variable of the binary logistic regression model, namely, the presence in the paper’s title of explicit terms relating to gender. Slightly more than a quarter of the sample of 1132 SSH articles from the WOS database, which we extracted with a search for gender topics in articles by Romanian SSH scholars, contained ‘gender’ or similar words in the title.

Table 2. Gender-related words explicitly mentioned in the title of the paper (unstandardised coefficients and odds ratio).

The findings indicate that contrary to our first expectation, papers published in journals that JCR classified in JIF top quartiles according to their impact factors have lower odds of containing gender or similar words in their titles than published articles in journals that JCR had not classified in this respect. While the effect is similar across the four JIF quartiles, the association is statistically significant only for the third quartile. Thus, we have statistical grounds for affirming that articles published in journals ranked in the third quartile have odds less than half those of articles in unclassified JIF journals of the title containing gender-related words. Regarding the effect of the publication year, since we found no association between the number of years since the article’s publication and its title, our findings do not support the second hypothesis. We found a significant association between the single-authored articles and the dependent variable. However, the sign of the coefficient is different than expected. Thus, contrary to our expectation, single-authored articles are more likely to include gender-related words in the title than articles co-authored by multiple scholars. In addition, in line with our expectations, the findings suggest that articles showing women as the first author or single author are 1.5 times more likely to include gender or similar words in the title than articles by men as first or single author. Likewise, author affiliation with one of the four Romanian universities with a relatively higher degree of institutionalisation of Gender Studies has a positive effect on the dependent variable, the presence of gender-related words in the title. This provides empirical support for our fifth hypothesis (H5) postulating a positive association between our dependent variable and the authors’ embedment in an institutional context where a specialised master’s degree does or did exist in the field’s curriculum.

Discussion

Our analysis occurs at the paper level and takes account of bibliometric information. It includes authors’ characteristics and institutional factors that explain the variation in the use of gender-related words in the titles. This is one way to assess the level of engagement with feminist epistemology in the Romanian post-socialist academic environment. Papers’ titles usually provide more concise and direct information about their content, while journals usually draw authors’ attention to the importance of selecting those words that best describe the analysis. Along with a paper’s title, abstract and keywords, researchers’ names constitute the most significant criteria on the basis of which potential readers can decide to continue to read or discontinue their reading of the papers. The established authority of one researcher in a specific domain could provide incentives for the audience to engage as readers. We ran our regression on bibliometric data for 1132 articles published between 1994 and 2022 in the SSH domain, by scholars with affiliations in Romania. It indicates that papers’ titles have greater chances of including gender-related words when at least one of their authors is affiliated with Romanian higher-education institutions offering master’s programmes in Gender Studies. As we expected, this finding suggests that institutional logics, within which the research is anchored, permeate individual scholars’ research interests. Therefore, in those institutions that formally acknowledge Gender Studies as an accredited academic field, scholars may consider their preoccupation with Gender Studies as worthy of research interest and, therefore, not refrain from using suggestive words in the article titles. Conversely, researchers who work in academic institutions where Gender Studies are less institutionalised or absent would be less inclined to explicitly use gender-related titles, even if their analyses report on gender differences. These authors may be wary of their fellows’ disparaging attitude towards their choosing to entitle papers with gender-related words that can functionally label these authors as feminists. This aligns with McKnight’s (Citation2018, 228) results on teachers’ reluctance to explicitly use such terms when they perceive them to collectively operate as ‘dirty’ and typecast those who engage with them as ‘trouble maker, the dangerous political animal who is a threat to stability, who must be silenced’. As Negra (Citation2014) argues, feminist academics are well aware of and sensitive to the misrepresentation of their intellectual efforts in a postfeminist context, marked by the antifeminist stance prevalent nowadays in many national contexts. Notwithstanding this concern, institutional settings that more transparently include Gender Studies as a legitimate field of research can insulate academics from such negative perceptions. In turn, that could explain academics’ greater propensity to select gender-related words for the titles of their articles, unlike institutions that insert gender-related topics not at all or poorly within the disciplines of other study programmes that only deal with them in a subsidiary fashion.

Regarding the effect of the publication’s position in the JCR quartiles on the likelihood of the paper’s title containing gender or gender-related terms, we observed that papers published in journals that JCR ranks according to their impact (i.e. JIF quartile) are less likely to have such words in their title than papers that WOS indexes, but JCR does not classify. Research evidence on the inequalities in academic knowledge production has already documented the exclusionary practices of highly ranked journals whose nondiscursive requirements disfavour scholars from less developed countries. These authors usually fail to meet publication standards that are not democratic in their ways of reviewing or selecting manuscripts by authors affiliated with institutions on the world’s periphery. Such authors may not have mastered English sufficiently and or possess the academic writing skills and style that the hegemonic publishing pedagogies of dominant academic institutions teach (Arnado Citation2021; Suresh Canagarajah Citation1996; Wellmon and Piper Citation2017). Our tentative explanation for the negative association between the position of publications in the JCR quartile hierarchy and the paper’s title inclusion of gender-related words rests on author affiliation with Romanian institutions that deal with gender or feminist research. Those authors may not have benefitted from adequate training during their graduate and postgraduate studies that would have enabled them to acquire a solid foundation and reach epistemic authority within the feminist field (Anderson Citation1995; Grasswick Citation2018). Unlike their Western counterparts, more thoroughly and thoughtfully taught the feminist epistemologies, Romanian scholars might lack the conceptual apparatus to properly address pressing gender issues that prestigious journals define. Therefore, research papers by Romanian feminist scholars may not fully reflect contemporary debates nor fit the publishing politics of highly reputable journals if insufficient institutionalisation of Gender Studies hindered their acquisition of corresponding epistemic skills.

We initially expected that a gradual institutionalisation of Gender Studies would be conducive to greater likelihood of recent publications more directly expressing their engagement with topics related to gender issues by introducing gender-related words in their title. We did not find such a statistical association. Also contrary to our expectations is the positive association we found between single-authored articles and the occurrence of gender or similar words in the article’s title. Unlike articles by multiple co-authors, those of single authors have greater odds of gender-related words occurring in their title. Articles in the SSH domain are less likely than those from other scientific domains to have a large number of authors. In our dataset, 59% of the 1132 sampled articles had three authors at most, while 25% had a single author. One possible explanation for our findings is that a large number of authors of SSH papers could result in rather heterogeneous interests from the perspective of authors’ specialisation. Consequently, such diversity of preoccupations can create more difficulty in finding convergence on gender-specific titles among a large body of co-authors, diluting gender in wider research. The prevalence of the negative public view of feminism in postcommunist Romania (Ilie Citation2013) can discourage Romanian scholars from self-identifying as feminists and lead them to avoid any academic focus that could indicate such an orientation.

Our next finding shows that the female gender of the first or single author has a positive effect on the title’s likelihood of alluding to a gender-related topic. This is the most important in size compared to other predictors in the regression analysis. Why would men as first or single authors be less prone than their female counterparts to select gender-related words in titling their articles? One tentative answer is that feminism prevalently appears as a threat to masculinity. Its pursuits may clash with those ideas, fantasies and aspirations regarding men’s proper conduct and the traits they embody in emulating the socially acceptable and culturally validated masculine identity as formal organisations, such as universities, disseminate them (Breen and Karpinski Citation2008; Connell and Messerschmidt Citation2005). Male scholars may avoid using gender-related words in the titles of their papers because they fear both a loss of masculine status and an attitude among their academic peers that devalues them, inasmuch as a gender-related research topic is taken less seriously than other topics. In some national contexts, men have found opportunities to actively support feminist activism (Baily Citation2015; Coulter Citation2003). However, in Romania, feminism is still portrayed as a women’s struggle (Ana Citation2017), echoed in academia where men researching feminism remain invisible.

Finally, our findings point to the significance of an author’s affiliation with Romanian higher-education institutions providing master’s programmes in Gender Studies, and the enhanced chances of the titles of articles by these authors explicitly including gender-related words. This finding supports our final hypothesis, namely, that universities delivering such programmes institutionalise Gender Studies to a greater degree. We consider their academics more familiar with and more willing to integrate a gender perspective in their research. Some authors of gender-specific papers are academics responsible for the provision of courses in Gender Studies, while others are colleagues working in the same or related departments. Accordingly, they have greater exposure to gender issues and feminist research approaches than academics in organisational settings lacking Gender Studies programmes. Other contexts have documented this effect of academic exposure to an organisational culture open to gender mainstreaming (Bystydzienski et al. Citation2017).

Based on these insights, we seek to answer the question of how to stimulate the production of valuable feminist research in SSH, in the context of poorly institutionalised Gender Studies. The pervasive audit culture within higher education institutions results in the implementation of quality standards that urge striving for excellence in both teaching and research (Geven and Maricut Citation2015). As rational actors, scholars will seek opportunities to publish in journals indexed in databases that provide them with their institution’s highest rewards, in terms of access to opportunities for career advancement and other material and symbolic benefits. According to current evaluation standards and procedures for research, the basis for an important share of funding allocated to universities, articles in journals with the highest impact factors (JIF), situated in the first and second quartiles, receive better rewards than those in other databases. The author’s citation index (Hirsch index) is another criterion for universities’ evaluation of excellence in research. These incentivise Romanian authors to publish in journals that ensure greater exposure of their research, which triggers a rising number of citations in journals situated in the top JIF quartiles. The first policy implications of our findings suggest that the decision-makers at the level of faculties and research institutes in the SSH domain must focus on creating a facilitating environment for scholars interested in feminist research. This can occur by tackling the negative stereotypes with regard to feminism’s ideological underpinnings and its ostensible lack of epistemological foundation. Second, academic institutions could foster more exchanges with those universities running master’s programmes in Gender Studies. Thus, they could enable the proliferation of professional networks among academics, carving out a space for the development of academic debates and the production of original ideas on gender, to serve in formulating new research questions. Third, institutions can support the research on gender issues through their own funding mechanisms, leading to the creation of mixed research teams in which both men and women scientists co-produce research outputs, reflecting on gender-related topics using feminist approaches. The publication of joint scientific articles in prestigious journals can improve the perceived value of both men’s and women’s work and result in men’s openness to adopting a gender lens in their independent research. Although our findings suggest that men are less likely to publish gender-specific papers as a single or a first author, they can certainly make a valuable contribution to feminist research if academic institutions help scientists overcome the negative stereotypes regarding the loss of masculine status by men engaging with feminist research. Echoing findings from the literature describing the improved perceived occupational prestige and remuneration following men’s entering female-dominated occupations (Acker Citation2006; Arndt and Bigelow Citation2005; Mcdowell Citation2015), we have reasons to believe that male scientists’ higher production of gender-specific articles could buttress the perceived scientific value of this research field. Finally, we consider of crucial importance the rapid institutionalisation of Gender Studies in Romanian higher education, not only at the master’s level but also at the bachelor and doctoral levels. Such a measure is necessary not only from the perspective of Romania's alignment to some minimal standards of European developments in this regard. It also responds to some real and urgent needs of Romanian society. Above all, it is worth remembering that in recent years, Romania has consistently occupied one of the last positions in the European Union with respect to the Gender Equality Index and domestic violence. Without being a miraculous solution to such complicated societal problems, stimulating the production of gender-specific scholarly studies and the institutionalisation of Gender Studies in higher education would undoubtedly represent a necessary step in raising awareness of the problems. The fact that four Romanian higher-education institutions introduced dedicated master’s programmes that are difficult to sustain amidst the weak institutionalisation of the field shows that at the societal level, they respond to real emergencies that transcend institutional frameworks. Continuing efforts to implement and maintain Gender Studies in Romanian higher education best demonstrate their value through the growth of Romanian scientific production in this field. In addition, this has occurred despite the authors earning a weak academic recognition, in the absence of adequate institutional rewards. All these represent strong arguments for the reform of higher education in Romania with respect to the introduction of gender-specific courses and dedicated study programmes in all degrees and various SSH fields. Such transformation of scientific fields can however more easily occur when a gender-sensitive pedagogy (e.g. manuals of gender equality for teachers) is taught earlier in schools and high schools since they reach out to a larger population than students and academics.

Concluding remarks

This article examined the predictors for producing gender-specific literature against the backdrop of the precarious institutionalisation of Gender Studies in Romanian higher education. It also acknowledged the broader movements outside academia, such as the rising antigender campaign at global and domestic levels. Academics do not engage with research topics in a cultural and political vacuum. On the contrary, their research interests are spurred by or collide with and resist cultural and political agendas in which their academic institutions are embedded. Our study contributes to the knowledge of individual and institutional factors predicting the production of gender-specific research by scholars affiliated with Romanian academic institutions. The study occurred in the context of poorly institutionalised Gender Studies, characterised as fragile three decades after communism’s fall in Romania (Băluță Citation2020). We have used binary logistic regression on bibliometric information related to 1132 papers from the WOS database, to tap into the individual and institutional factors associated with the production of gender-specific literature in Romania. The findings suggest that this national context is marked by weak institutionalisation of Gender Studies and pervasive stereotypes regarding the incongruence between masculine identity and men’s appropriation of gender as a research topic. The female gender of the first author, as well as affiliation with a Romanian university running a master’s Gender Studies programme, positively correlate with the paper’s likelihood of including gender-related words in its title. Likewise, single-authored articles have greater odds than co-authored articles of including a reference to gender in their titles. On the contrary, the position of the journals in the JCR hierarchy with respect to their JIF quartile negatively impacts the chance of a paper’s title conveying an orientation towards gender-specific research.

The importance of this study lies in its examination of both individual and institutional factors affecting the production of gender-specific knowledge. The bibliometric data from which its findings emerged are available on one of the most valued scientific databases, namely, the WOS Core collection platform, the common reference in the standard evaluation of excellence in research by Romanian academic institutions. Romanian scholars receive financial and career-based incentives to publish in journals indexed in WOS and, therefore, they may orient their research predominantly in that direction. However, one must be cautious about sweeping generalisations. SSH researchers have traditionally published in journals indexed in other databases. Therefore, our dataset provides a partial explanation of the knowledge production of gender-specific research. We call for further documentation of the dynamics and predictors of such research using similar datasets from different databases. One must bear in mind that WOS currently has overriding importance among other databases in Romanian higher education. Academics are aware that publishing in WOS is more rewarding for SSH scientists pushed to seek new outlets for their research outcomes. Another limitation of the current study resides in the number of predictors we used for the analysis and the rather poor effect size of the regression model, as suggested by the low value of Nagelkerke’s R2 reported in . Future research may therefore examine the role of other relevant factors such as the presence of national and international collaborations, the number of references, the acknowledgement of grant support, the use of tables and figures, and the methodological approach. Likewise, new research could propose cross-national comparisons of gender-specific knowledge by including other CEE countries where the institutionalisation of Gender Studies followed a similar pattern, to assess the contribution of other contextual factors, such as education reforms and models of academic governance (Dobbins Citation2017). Finally, bibliometric studies using science-mapping techniques can enable meaningful visualisations of thematic clusters, based on the co-occurrence of keywords, and cross-country collaborative ties in the development of gender-specific scholarly research in CEE countries.

Acknowledgements

This work is supported by the Ministry of Research, Innovation and Digitisation through Programme 1, Development of the national research-development system; Subprogramme 1.2, Institutional performance, Projects for financing excellence in RDI, contract no. 28PFE/30.12.2021 and by the European Union’s Horizon Europe research and innovation programme under Grant 101079282 (ELABCHROM). Views and opinions expressed are however those of the author(s) only and do not necessarily reflect those of the European Union or granting authority. Neither the European Union nor the granting authority can be held responsible for them.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 See the standards avalable as of 28 July 2022 at: https://www.aracis.ro/wp-content/uploads/2022/08/4.-Standarde-ARACIS_Comisia-4_Stiinte-sociale-politice-si-ale-comunicarii_28.07.2022.pdf (for Social Sciences) and https://www.aracis.ro/wp-content/uploads/2019/07/2._Standarde_ARACIS-Comisia_2._Stiinte_umaniste_si_teologie_-_2017.pdf (for Humanities).

2 See details about CWTS methods of collapsing 4,159 micro-level fields into five main scientific fields here https://www.leidenranking.com/information/fields#algorithmically-defined-main-fields

References

- Acker, Joan. 2006. “Inequality Regimes: Gender, Class, and Race in Organizations.” Gender & Society 20 (4): 441–64. doi:10.1177/0891243206289499.

- Ana, Alexandra. 2017. “The Role of the Feminist Movement Participation During the Winter 2012 Mobilisations in Romania.” Europe-Asia Studies 69 (9): 1473–98. doi:10.1080/09668136.2017.1395810.

- Anderson, Elizabeth. 1995. “Feminist Epistemology: An Interpretation and a Defense.” Hypatia 10 (3): 50–84. doi:10.1111/j.1527-2001.1995.tb00737.x.

- Annandale, Ellen, and Anne Hammarström. 2011. “Constructing the ‘Gender-Specific Body’: A Critical Discourse Analysis of Publications in the Field of Gender-Specific Medicine.” Health: An Interdisciplinary Journal for the Social Study of Health, Illness and Medicine 15 (6): 571–87. doi:10.1177/1363459310364157.

- Antić, Marija, and Ivana Radačić. 2020. “The Evolving Understanding of Gender in International Law and ‘Gender Ideology’ Pushback 25 Years Since the Beijing Conference on Women.” Women’s Studies International Forum 83 (February): 1–7. doi:10.1016/j.wsif.2020.102421.

- Arnado, Janet M. 2021. “Structured Inequalities and Authors’ Positionalities in Academic Publishing: The Case of Philippine International Migration Scholarship.” Current Sociology 71: 356–78. doi:10.1177/00113921211034900

- Arndt, Margarete, and Barbara Bigelow. 2005. “Professionalizing and Masculinizing a Female Occupation: The Reconceptualization of Hospital Administration in the Early 1900s.” Administrative Science Quarterly 50 (2): 233–61. doi:10.2189/asqu.2005.50.2.233

- Baily, Jessica. 2015. “Contemporary British Feminism: Opening the Door to Men?” Social Movement Studies 14 (4): 443–58. doi:10.1080/14742837.2014.947251.

- Baird, Barbara. 2010. “Ambivalent Optimism: Women’s and Gender Studies in Australian Universities.” Feminist Review 95: 111–26. doi:10.1057/fr.2009.58

- Băluță, Ionela. 2020. “Studiile de Gen: Un Turnesol Al Democrației Românești [Gender Studies: A Litmus Test of Romanian Democracy].” Transilvania 11–12: 34–41. doi:10.51391/trva.2020.12.04.

- Bourdieu, Pierre. 1983. “The Field of Cultural Production, or: The Economic World Reversed.” Poetics 12 (4–5): 311–56. doi:10.1016/0304-422X(83)90012-8.

- Breen, Amanda B., and Andrew Karpinski. 2008. “What’s in a Name? Two Approaches to Evaluating the Label Feminist.” Sex Roles 58 (5–6): 299–310. doi:10.1007/s11199-007-9317-y.

- Brodeală, Elena, and Georgiana Epure. 2022. “Nature versus Nurture: ‘Sex’ and ‘Gender’ before the Romanian Constitutional Court. A Critical Analysis of Decision 907/2020 on the Unconstitutionality of Banning Gender Perspectives in Education and Research.” European Constitutional Law Review 17: 724–52. doi:10.1017/S1574019622000013.

- Bystydzienski, Jill, Nicole Thomas, Samantha Howe, and Anand Desai. 2017. “The Leadership Role of College Deans and Department Chairs in Academic Culture Change.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (12): 2301–15. doi:10.1080/03075079.2016.1152464.

- Cîrstocea, Ioana. 2010. “Eléments Pour Une Sociologie Des Études Féministes En Europe Centrale et Orientale.” International Review of Sociology 20 (2): 321–46. doi:10.1080/03906701.2010.487674.

- Connell, R. W., and James W. Messerschmidt. 2005. “Hegemonic Masculinity Rethinking the Concept.” Gender & Society 19 (6): 829–59. doi:10.1177/0891243205278639.

- Coulter, Rebecca Priegert. 2003. “Boys Doing Good: Young Men and Gender Equity.” Educational Review 55 (2): 135–45. doi:10.1080/0013191032000072182.

- Dobbins, Michael. 2017. “Exploring Higher Education Governance in Poland and Romania: Re-Convergence after Divergence?” European Educational Research Journal 16 (5): 684–704. doi:10.1177/1474904116684138.

- Donthu, Naveen, Satish Kumar, Debmalya Mukherjee, Nitesh Pandey, and Weng Marc Lim. 2021. “How to Conduct a Bibliometric Analysis: An Overview and Guidelines.” Journal of Business Research 133 (September): 285–96. doi:10.1016/j.jbusres.2021.04.070.

- Geven, Koen, and Adina Maricut. 2015. “Forms in Search of Substance: Quality and Evaluation in Romanian Universities.” European Educational Research Journal 14 (1): 113–25. doi:10.1177/1474904114565151.

- Grasswick, Heidi. 2018. “Feminist Social Epistemology.” In The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. https://plato.stanford.edu/archives/fall2018/entries/feminist-social-epistemology/epistemology/.

- Hașdeu, Iulia. 2004. “En Roumanie, Le Féminisme Académique a Un Ascendant Sur Le Féminisme Militant.” Nouvelles Questions Féministes 23 (2): 88. doi:10.3917/nqf.232.0088.

- Ilie, Magdalena Ioana. 2013. “The Evolution of the Romanian Feminism in the 20th Century.” Procedia – Social and Behavioral Sciences 81: 454–58. doi:10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.06.459.

- Juhálsz, Borbála, and Enikő Pap. 2018. “Backlash in Gender Equality and Women’s and Girls’ Rights.” PE 604.955. Brussels. http://www.europarl.europa.eu/supporting-analyses%0ADISCLAIMER.

- Kitta, Ioanna, and María Cristina Cardona-Moltó. 2022. “Students’ Perceptions of Gender Mainstreaming Implementation in University Teaching in Greece.” Journal of Gender Studies 31 (4): 457–77. doi:10.1080/09589236.2021.2023006.

- Kloot, Bruce. 2009. “Exploring the Value of Bourdieu’s Framework in the Context of Institutional Change.” Studies in Higher Education 34 (4): 469–81. doi:10.1080/03075070902772034.

- Kuhar, Roman, and David Paternotte. 2017. Anti-Gender Campaigns in Europe. Mobilizing Against Equality. Edited by Roman Kuhar and David Paternotte. London, New York: Rowman & Littlefield International Ltd.

- Mcdowell, Joanne. 2015. “Masculinity and Non-Traditional Occupations: Men’s Talk in Women’s Work.” Gender, Work & Organization 22 (3): 273–91. doi:10.1111/gwao.12078.

- McKnight, Lucinda. 2018. “A Bit of a Dirty Word: ‘Feminism’ and Female Teachers Identifying as Feminist.” Journal of Gender Studies 27 (2): 220–30. doi:10.1080/09589236.2016.1202816.

- Millar, Krystina. 2021. “Rewards and Resistance: The Importance of Teaching Women’s and Gender Studies at a Southern, Comprehensive, Liberal Arts University.” Gender and Education 33 (4): 403–19. doi:10.1080/09540253.2020.1722069.

- Negra, Diane. 2014. “Claiming Feminism: Commentary, Autobiography and Advice Literature for Women in the Recession.” Journal of Gender Studies 23 (3): 275–86. doi:10.1080/09589236.2014.913977.

- Norocel, Ov Cristian. 2018. “Antifeminist and “Truly Liberated”: Conservative Performances of Gender by Women Politicians in Hungary and Romania.” Politics and Governance 6 (3): 43–54. doi:10.17645/pag.v6i3.1417.

- Rowlands, Julie. 2013. “Academic Boards: Less Intellectual and More Academic Capital in Higher Education Governance?” Studies in Higher Education 38 (9): 1274–89. doi:10.1080/03075079.2011.619655.

- Suresh Canagarajah, A. 1996. “‘Nondiscursive’ Requirements in Academic Publishing, Material Resources of Periphery Scholars, and the Politics of Knowledge Production.” Written Communication 13 (4): 435–72. doi:10.1177/0741088396013004001.

- Tullu, Milind. 2019. “Writing the Title and Abstract for a Research Paper: Being Concise, Precise, and Meticulous Is the Key.” Saudi Journal of Anaesthesia 13 (5): S12–17. doi:10.4103/sja.SJA_685_18.

- Văcărescu, Theodora-Eliza. 2011. “Uneven Curriculum Inclusion: Gender Studies and Gender IN Studies at the University of Bucharest.” In From Gender Studies to Gender IN Studies: Case Studies on Gender-Inclusive Curriculum in Higher Education, edited by Laura Grünberg, 147–84. European Center for Higher Education, Bucharest: UNESCO.

- Vlase, Ionela, and Tuuli Lähdesmäki. 2023. “One Country with Two Systems: The Characteristics and Development of Higher Education in the Guangdong–Hong Kong–Macau Greater Bay Area.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10 (1): 1–14. doi:10.1057/s41599-022-01483-z.

- Wellmon, Chad, and Andrew Piper. 2017. “Publication, Power, and Patronage: On Inequality and Academic Publishing.” Critical Inquiry, 1–20.

- Zimmermann, Susan. 2008. “The Institutionalization of Women’s and Gender Studies in Higher Education in Central and Eastern Europe and the Former Soviet Union: Asymmetric Politics and the Regional-Transnational Configuration.” East Central Europe 34 (1): 131–60. doi:10.1163/187633007789886009.