ABSTRACT

Internships are widely recognized within higher education as a useful work-based learning (WBL) approach to enhance student employability. However, there remains a need to understand whether internships provide a developmental experience that includes higher-level (soft) skills such as self-responsibility, flexibility and innovation. Our study inductively analyses 154 undergraduate student-interns’ reflective diaries over a 3-year period to explore the relationship between internship experience and the development of higher-level skills, or protean ‘meta-competencies’. In the research, we find the interns’ developed three meta-competencies that can broadly be categorized as self-regulation, self-awareness and self-direction. Our findings also highlight the role of socio-political dynamics of internship work in shaping students’ experiences as an indicator of the changing world of work. The study has implications for higher education institutions (HEIs) and host organisations in adopting a WBL approach that supports interns with reflexive engagement with situated organizational practices and accessing (in)formal learning opportunities in the workplace. Our research, therefore, offers insights into a learner-centred WBL approach that contributes towards a more holistic internship/WBL experience that facilitates student interns in developing protean meta-competencies and graduate employability.

Introduction

Employability is a key reason why many students seek higher education (Kim, Kim, and Tzokas Citation2022; Perusso and Wagenaar Citation2022), and there is a growing expectation of higher education institutions (HEIs) to produce skilled, employable graduates (Arranz et al. Citation2022; Bradley, Priego-Hernández, and Quigley Citation2022). Subsequently, many HEIs now embed work-based learning (WBL) in the form of internships, or work placements, within their curriculum to support graduate employability (Jackson and Rowe Citation2023; Lester and Costley Citation2010; Raelin Citation1997). This may involve undertaking ‘short-term practical work experience’, eligible for credit as students receive ‘training and gain experience in a specific field or career area of their interest’ (Zopiatis Citation2007, 65).

With changing work conditions and labour market structures (Scott Citation2015), there are calls for graduates to engage in lifelong learning, diagnosing their own learning needs, and building ‘portmanteau’ or ‘portfolio’ careers (Eberhard et al. Citation2017). Given that career paths are no longer linear, HEIs need to support students in developing higher-level (soft) employability skills as graduates may well be spending periods in different work arrangements, such as established organizations or start-ups, self-employment, consultancy or even a combination of several roles (see Ryder and Downs Citation2022; Santos Citation2020).

Despite the usefulness of WBL as a work-readiness pedagogy, it has been critiqued for its siloed approach (Wall et al. Citation2017), due to its focus on prescribing generic skills and knowledge to students (Felstead and Unwin Citation2016). This approach is deemed less helpful for supporting students to develop portfolio careers (Eberhard et al. Citation2017) and dealing with the complexities of the modern-day workplace. Employers are also becoming concerned about graduates’ lack of relevant skills, or the ‘skills-gap’, as they enter the labour market (Arranz et al. Citation2022; Perusso and Wagenaar Citation2022). Scholarship in career development argues that individuals with protean meta-competencies are better poised to engage with contemporary work environments and career paths (c.f. Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2017; Sargent and Domberger Citation2007). While internships linked with WBL certainly contribute towards students’ university-to-work transition (Bradley, Priego-Hernández, and Quigley Citation2022; Kim, Kim, and Tzokas Citation2022), there is little research exploring whether they adequately prepare students to develop meta-competencies such as self-responsibility, adaptability, flexibility, inter-personal communication and empathy (Hall Citation1996; Citation2004).

This study, therefore, sets out to explore the possibilities of developing protean meta-competencies within the context of (paid) internships as part of a WBL programme in an HEI. We contribute to scholarship on WBL (Boud and Garrick Citation1999; Boud and Solomon Citation2001; Lester and Costley Citation2010; Raelin Citation1997; Citation2008), by offering insights into how individualized WBL curricula and its corresponding internship design with host organisations can be used to support students in developing protean meta-competencies (Hall Citation1996, Citation2004; Lester and Costley Citation2010). We define individualized learner-centred WBL curriculum as one that encourages individuals to engage in reflexive practices and develop an understanding about ‘self-in-relation-to-others’ within the context of situated organizational work practices (Vince Citation1998; Citation2002).

Our study draws on 154 student-interns’ monthly reflective logs submitted as part of a redesigned WBL curricula, to shed light on the challenges linked with socio-political work dynamics that students experienced during their internship. In this paper, we argue that informal and often serendipitous work situations provide opportunities for student interns to develop protean meta-competencies as a way to negotiate workplace challenges. We identify the protean meta-competencies as self-regulation, self-awareness and self-direction. While our study offers implications for HEIs and host organisations with a focus on individualized WBL curricula, we also call for further research to focus on WBL pedagogies that support student interns in developing protean meta-competencies (Kim, Kim, and Tzokas Citation2022).

Theorizing protean meta-competencies and undergraduate internships

The literature considers protean meta-competencies as those that facilitate individuals to achieve self-fulfilment as well as developmental career progression (Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2017; Sargent and Domberger Citation2007). Protean meta-competencies help individuals develop psychological durability to apply a diverse range of skills and identify personal learning needs throughout one's (portmanteau) career by accessing informal and formal learning opportunities (Hall Citation1996; Citation2004; Hall and Mirvis Citation1995). According to the pioneer of protean career theory, Douglas T. Hall (Citation1996), continuous learning and self-responsibility are core elements in developing the two protean meta-competencies his work identified: identity (akin to self-awareness) and adaptability. The notion of protean careers has emerged in response to the changing work and career structures where distinct boundaries surrounding job functions and professions have blurred, as individuals take up multiple work roles as careers become boundaryless with multiple pathways being the norm (Briscoe and Hall Citation2006). This boundarylessness and flexibility, as described by Hall (Citation1996), shows a greater need for developing protean meta-competencies to cope with the changing world of work.

From a WBL perspective, encouraging the development of protean meta-competencies as part of students’ university-to-work transition will be important to support them in usefully engaging with complex work dynamics and sustaining pressures of the labour market (Kim, Kim, and Tzokas Citation2022). Traditionally, undergraduate students engage in a variety of work-related experiences during their internships with the aim to improve their employability skills (Bradley, Priego-Hernández, and Quigley Citation2022). Some HEIs, however, make little effort to explicitly link internship experience to learning on degree programmes, and as such internship may take place in isolation (Gateways to the Professions Collaborative Forum Citation2013). One approach to linking internships with a degree programme is for student interns to undertake projects related to the HEI curriculum, often underpinning a final-year dissertation (Parker Citation2018). Other approaches include creating a portfolio of professional practice and/or writing reflective essays towards the end of the internship experience (Lang and McNaught Citation2013; Scholtz Citation2020).

Existing WBL pedagogical approaches, however, remain centred around the power of the validating institution, their definitions of learning, and criteria for evidencing that learning has taken place (Felstead and Unwin Citation2016). Research indicates that HEIs, engrossed in the process of formalizing WBL, tend to be less successful in supporting students to meaningfully engage and learn from complex situated organizational realities and even influence micro-level changes within work situations (Hinnings and Greenwood Citation2002; Illeris Citation2012). For example, scholars argue that existing WBL approaches tend to be institution-led and are siloed and/or bolted-on, and therefore become either too rigid or generic to acknowledge learner-specific needs at work (Felstead and Unwin Citation2016; Wall et al. Citation2017). This further contributes to the criticism of the graduate ‘skills gaps’ (Arranz et al. Citation2022).

More recently, literature has raised concerns about assumptions around the supposedly linear pathways of graduate careers, and that little attention has been given to student-interns’ struggles in developing employability skills amid workplace complexities and challenges (e.g. precarious or meaningless work) (Arranz et al. Citation2022; Kapareliotis, Voutsina, and Patsiotis Citation2019). Research also suggests that protean competencies can be difficult to plan for through predetermined learning activities in the workplace (Van de Werfhorst Citation2014). Our theorization of internships in higher education contributes to calls for reconceptualizing WBL to support students in coping better with complex organisational phenomena and the changing demands of the labour market (Donald, Baruch, and Ashleigh Citation2017; Sargent and Domberger Citation2007).

Building on the work of scholars such as Basit et al. (Citation2015), we contend that adjusting traditional institution-led WBL approaches towards a more learner-centred internship experience could offer student interns more fruitful opportunities for developing protean meta-competencies. This is important as literature suggests that those who are at the periphery of organizations (e.g. temporary workers, interns) tend to find limited access to opportunities of learning (e.g. Sides and Mrvica Citation2007), which can impact students’ university-to-work transition (Bradley, Priego-Hernández, and Quigley Citation2022; Okolie, Nwosu, and Mlanga Citation2019; Perusso and Wagenaar Citation2022). Along with other scholars, we argue for WBL pedagogies to move beyond the scope of prescribed curricula, to one that encourages students’ holistic thinking and reflexive evaluation of their experience and engender new ways of conceptualizing and problematizing work practice (Svanström, Lozano-García, and Rowe Citation2008). For example, being able to reflexively evaluate the social, cultural, political and historical dimensions of the workplace is particularly useful in the context of interns as learning in workplace is often ‘ … realised through the expertise and understanding [of experts]’ (Koskinen, Pihlanto, and Vanharanta Citation2003, 281).

Methodology

This study draws on the experiences of 154 student-interns enrolled in a WBL module across three cohorts at a UK business school. As part of this module, the students were required to undertake a year-long paid internship with a host organisation. The majority of students were aged in their early 20s and studying in the third year of an undergraduate degree programme. The students were placed at over 80 different organizations (or ‘hosts’) after taking part in competitive recruitment rounds. These host organizations were of varying sizes, and situated locally, nationally and globally, the internships lasting between 9 and 12 months.

The WBL module adopted a learner-centred individualized curricula that required each student to create their internship learning objectives and plan (i.e. a learning agreement), in partnership with their employer and HEI – a tripartite approach. The learning plan focused on identifying key (usually soft) skills and set out a range of learning opportunities for skills development. The next stage was for the three partners to agree how learning would be evidenced with assessment criteria focussing on the need for framing evidence to highlight employability skills. The students could adopt different formats for presenting evidence of employability skills development rather than the HEI setting out specific formats for submitting a report or a grading criterion.

As part of the module, students had to submit monthly reflective logs throughout their internship, capturing work-based learning incidents (usually informal learning) and developing action plans. These monthly logs were unassessed pieces and were included to facilitate students in developing a reflective essay at the end of their year-long internship. Before starting their internship, students were introduced to the notion of reflective practice and associated learning theories through lectures, readings and workshops spread over three weeks. They were encouraged to select a model of reflection (although this was not obligatory) where models used included Schön (Citation1983), Kolb (Citation1984), Gibbs (Citation1988) and Johns ( Citation1995).

After securing data-access approval from the relevant business school’s research ethics committee, the students were informed of the study’s focus and intended use of their monthly reflective logs as data source. We also communicated to the students that any information that may reveal identity of students, staff and/or employing organisations will be removed from the data before it is released for the study. As an additional measure, we agreed that the data will be used in any research output only after the students had completed their internships, the associated module, and graduated from the university. Also, using non-assessed pieces of student writing for the research helped mitigate concerns around forceful or superficial production of data.

A total of 1232 monthly reflective logs were compiled and used for analysis. The average length of each log was around 460 words, producing a dataset of 566,887 words (see ).

Table 1. Overview of the dataset.

For data analysis, we adopted a reflexive thematic approach in categorizing the patterns in the data (e.g. Braun and Clarke Citation2006; Citation2019). The data analysis unfolded in three iterative phases, during which the individual researchers developed a series of codes built from their reflections on the meaning of the data, exploring the intersections between theoretical interpretation and empirical data to make sense of how student-interns experienced work-related learning and negotiated workplace complexities as part of their internships (see ).

Table 2. Analytical framework.

The co-authors engaged in reflective discussions and collaborative mind-mapping that allowed not only mitigating individual researcher’s bias and assumptions but also considering different interpretations in developing an understanding of the inter-related themes within the data (Byrne Citation2022). The approach meant initial codes were diverse, reflecting the different engagements with the material (Braun and Clarke Citation2019; Byrne Citation2022). The resulting codes were discussed, compared and reworked amongst the co-authors for consistency purposes as well as to identify the main narrative. This process led to generation of 924 labels for coding data (see ).

Table 3. Sample codes.

The second phase was concerned with the student-interns’ experience and their ability to negotiate different situations during their internships, that is, the attributions of themselves, others and their work. The reflective text was recoded with particular attention to metaphors or analogies used to describe events, actions or feelings unfolding in their narratives. For example, we used analytical reasoning by questioning ourselves: ‘To whom is the intern referring?’, ‘What does this mean for their experience?’ and ‘Does this have an impact on how they view themselves, others or their work?’ This phase eventually concluded by collapsing codes into categories (see ).

Table 4. Sample code categorization.

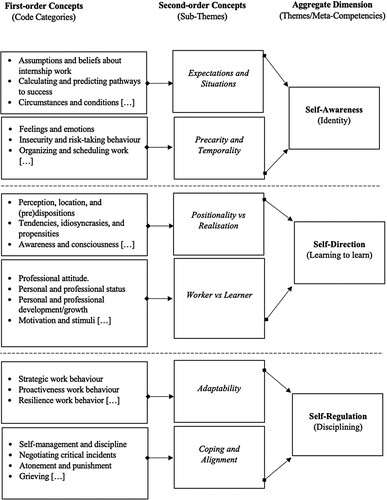

The third phase focused on aggregating categories into higher-order concepts through the identification of associations and continuous dialogue among authors to theorize reflective text. This led to associating textual narratives with code categories describing student-interns’ experience about working, learning and internships as they were produced and maintained within the internship context. Bunching codes into categories about theory led to six sub-themes (expectations and situations; precarity and temporality; positionality vs realisation; worker vs learner; adaptability; coping and alignment). Familiarity with the data encouraged the identification of patterns of significance allowing the team to identify three distinct themes (self-awareness, self-direction and self-regulation). These themes (or meta-competencies) consequently emerged as a result of cycling between data and theory over the three analytical phases (Braun and Clarke Citation2019).

Findings

Findings of this study are presented under aggregate dimensions which shed light on the meta-competencies that student-interns allude to in their experiences as they negotiate the complexities of the workplace (see ).

Self-awareness

Self-awareness, akin to a sense of self or identity (c.f. Hall Citation1996; Citation2004) in the workplace, requires an understanding of how individuals and their work roles are interconnected as they do not perform their work in isolation rather, they respond to expectations and situations. For example, when actions are incongruent with self-beliefs or others’ expectations, they are likely to create tensions between individuals, others and their role in the workplace. Several students highlighted that such discrepancies are likely to arise when expectations mismatch with the performative dimension of the internship role. One intern reflected that the way she was predisposed to behaving in the workplace was entirely different to what her line manager expected her to do. She wrote that the implicit expectation of an intern was to sit quietly in a meeting whereas she considered herself as knowledgeable coming from a business school.

[…] members often asked me for clarifications and to me this was reassuring that I was acting the right way and that they saw me as a source of knowledge. [Upon reflection] I got to know, I should’ve acted differently by being quieter and not participating in the meetings […] Thinking back to the time, I interpreted the event in a manner that was consistent with my emotions and expectations at that time. Had I known my boss’ expectations, I would have acted differently [c14-s31].

Being on placement means that it is imperative to work in a flexible manner and always expect the unexpected, but it is also important to be honest and transparent to colleagues about the reality of meeting their expectations. In doing so, I anxiously decided to send out my 360 surveys again to see whether people’s perception of me has changed [c15-s23].

I feel a bit frustrated because of the lack of work and learning opportunities. I feel that this is only because I am a temporary trainee [c15-s41].

My manager has been lenient to me regarding this, it’s probably because of my trainee level and temporary employee status [c15-s34].

The reason why I am not given much responsibility is because I am only a temporary employee. As a result, my line manager might not see much return on investment in training me for more complicated and demanding skills, since I will leave the firm anyway [c14-s19].

Self-direction

Findings indicate that self-direction is important as it can instill responsibility-taking behaviour. In negotiating role and relational dynamics, intern accounts reflect their struggles as being socially situated as either workers or learners. One intern placed in a car rental firm suggested that despite his efforts to develop stronger relationships with his teammates he was still treated as an ‘outsider’.

I could’ve done more socializing to get a bit more personal with my colleagues, but I couldn't, partly because of my introversion, age difference and also background [c15-s42].

This was not how I'd imagined writing my April log, but it's about an important aspect that truly interferes with my working life […] I am quite dependent on other people, emotionally speaking as well as in the form of outsourcing my life. I had to deal with difficult things, admin stuff on my own. This has impacted significantly on my placement year especially as I’ve been often seen as childish and not yet a proper adult, ready to take on full responsibilities [c14-s29].

I made sure that even though I don't have the best relationship with my boss, I mimicked my PR manager’s style of constant communication with my boss even if I felt nervous to talk to her [c14-s11].

[Line-Manager] replied that she would take care of this, but I was very offended! Although I was prepared for the challenging attitude by others, I wasn’t prepared for negative feedback neither regarding my ways of communicating in general nor my personal approach […] What went well in this situation was that although I was feeling personally offended but I managed to behave professionally [c15-s37].

Self-regulation

Findings show self-regulation as a key competency of protean careers in two parts, that is, through instances ‘adapting’ to and ‘coping’ with internship role demands. Gotsi et al. (Citation2010) argue that regulation and control strategies are organisational mechanisms deployed by managers to influence individuals in performing their work roles more efficiently and as desired. For example, an intern indicated that working in a pharmaceutical company was challenging because she couldn’t fully experience the learning curve in her internship role. The reason behind this was her line-manager’s expectations, seeing her as a worker rather than a learner:

This month has been one of great change to say the least. Although, I have learnt a lot but not least about office politics. When to say and not say things has become increasingly prominent but I realise that I need to make sure that I use my position as an intern to learn from this situation […] despite the MD of the company stating that I was everything she looked for in a member of staff [c14-s7].

I decided to be open and flexible to any roles however I emphasised that [role x] is not my preference. This caused conflict with my [ABC] team and was escalated to the team-lead who told me sternly to be more positive and proactive in the future [c16-s31].

Meanwhile, some other interns referred to various tactics deployed by their colleagues and managers to pressurize them in taking up roles or responsibilities that other permanent employees could perform. For example, one intern recalled how their manager ‘over-dramatize[d] situations’ making him feel worse if he wouldn’t consider performing a particular task, which affected his morale at work. In contrast, some interns reported that they weren’t provided with the opportunity to ‘raise their voice’ by managers and felt ‘forced’ to perform certain tasks.

I felt as though because I was the intern in the team, I was forced into helping others too much when I had an equally high if not higher level of workload […] and had no time free. This made me feel annoyed because my team members did not appreciate that I was also working hard and that saying no […] was actually a fair decision [c14-s2].

I have learnt for the future that sometimes even less impactful roles or less prestigious assignments are worth taking as they can provide a valuable experience. It all depends on a person's attitudes, and I am happy that I managed to be proactive about that. With that mindset, I can build a great network and expertise during my current [project], which would be very helpful for the rest of my industrial placement as well as future career [c15-s36].

I started doubting myself, whether I would be able to cope with the knowledge barrier throughout this [placement] year? What can I do to maximise my outcome from this year? From this experience, I noticed that I had to take initiative in order to overcome my weaknesses, I need to be more proactive. It is essential to understand what the company offerings are […] as they can be rare [c15-s44].

Discussion and conclusion

Traditional WBL pedagogy, based on an acquisition model for skill development, is said to be limited in its focus to support students in developing higher-level (soft) skills needed in today’s changing labour market conditions and complex work environments (Hinnings and Greenwood Citation2002; Illeris Citation2012; Perusso and Wagenaar Citation2022). Our study adds to the literature on WBL in higher education as we highlight the relationship of internships, individualized curriculum and reflexive evaluation of barriers embedded within work practices for student interns in accessing (in)formal learning opportunities and developing protean meta-competencies (Boud and Garrick Citation1999; Boud and Solomon Citation2001; Lester and Costley Citation2010; Raelin Citation1997; Citation2008).

Through our findings, we argue for reconceptualizing WBL as a pedagogy (Arranz et al. Citation2022; Bradley, Priego-Hernández, and Quigley Citation2022; Jackson and Rowe Citation2023; Kim, Kim, and Tzokas Citation2022) to go beyond surface level notions of incidental or experiential learning (Vince Citation1998; Citation2002), or as prescribed by generic curricula (Felstead and Unwin Citation2016; Wall et al. Citation2017). Our reconceptualization of WBL acknowledges the situatedness of student-interns within their social, cultural, political and historical circumstances (e.g. Lave and Wenger Citation1991) and the need for interns to engage in reflexive practice for developing protean meta-competencies as they negotiate workplace complexities. This is, as Hall, Yip, and Doiron (Citation2018) highlight, the importance of self-direction and personal values in developing protean meta-competencies, but unless students are highly self-aware of the significance of these underpinning characteristics, they may not be identified.

Our holistic, yet learner-centred WBL approach recognises workplace dynamics as a negotiated process and attempts to tackle the asymmetrical positioning of the student-intern, HEI and host organizations in a tripartite stakeholder framework. One pedagogical practice in our WBL approach with such intended objective, was of negotiated learning agreement (including learning outcomes and assessment strategies) between host organisations, student-interns and HEIs. It also included student-interns writing non-assessed reflective logs on work-based incidents, with a particular focus on socio-political dynamics at play within host organizations. Our findings suggest that such WBL pedagogical approach appears to offer student-interns’ further opportunities in developing richer understanding ‘self-in-relation-to-others’, and this is said to foster ‘empirically supported protean processes – identity awareness, adaptability and agency’ (Hall, Yip, and Doiron Citation2018, 2).

Active engagement of student-interns with host organisations in setting learning objectives and assessment strategies as part of our WBL, is likely to encourage a dialogue about the workplace as a site for learning, and enables the creation of individualised learning programmes, including opportunities for shared reflection (Santos Citation2020). However, this will expect HEIs to move away from institution-centric and skills-based forms of assessment to adopting an individualized WBL curriculum that focuses on empowering learners to assume greater responsibility and control of their learning (Jackson and Rowe Citation2023; Lester and Costley Citation2010; Perusso and Wagenaar Citation2022; Raelin Citation1997). This can be integrated with developing more creative forms of assessment, in partnership with educators and host organisations. One example of such an assessment is the creation of a portfolio of professional practice that evidences the specific student learning outcomes to suit the needs of the student intern and host organisation, as agreed in the learning agreement in consultation with educators at the HEI. This could involve using a variety of media such as websites, booklets, podcasts, blogs, etc. to create portfolios. We recognise these pedagogical actions alone may not resolve power differentials within the tripartite relationship inherent within an internship module. However, we opine that adopting pedagogical steps (e.g. negotiated learning agreement) could enable open discussions about varying influence within the tripartite relationship and offer further opportunities for student-interns assume control of their learning as well as develop protean meta-competencies (Hall Citation1996; Raelin Citation1997).

To conclude, we argue that HEIs ought to adopt assessment designs and practices that encourage student interns to reflexively process their internship experiences and make sense of work-related events, norms, practices and socio-political dynamics (Lester and Costley Citation2010). This, however, would imply HEIs having to forego some of their influence over the tripartite relationship in a WBL approach and facilitating co-creation of learning outcomes and supporting integrating reflective practice (Hinnings and Greenwood Citation2002; Illeris Citation2012). Host organisations will also need to recognise student interns as individuals with abilities to contribute towards organisational goals, and to accordingly support them in being able to engage better with work dynamics and practices (Lester and Costley Citation2010). This, we contend, will contribute towards generating opportunities for student-interns developing protean meta-competencies, and addressing issues linked to the perceived graduate ‘skills gap’ (Arranz et al. Citation2022; Kim, Kim, and Tzokas Citation2022; Perusso and Wagenaar Citation2022).

A limitation of our study, however, is that it is based on data from student-interns’ reflective logs, meaning themes were chosen by the individual students rather than the study design. Future research could adopt a multi-perspectival approach by collecting data from multiple HEIs as well as gathering data from other stakeholders involved in the tripartite relationship. Also, studies exploring interactional mechanisms of university and host organizations in supporting the creation of individualized WBL curriculum could offer useful insights. Finally, research that examines the development of protean meta-competencies and reflexive engagement with work dynamics in the case of graduates in their first full-time employment but with no prior internship experience, will also make an important contribution to the literature.

Ethics statement

Ethical clearance was given by the Lancaster University ethics approval system, project information sheets were given to all participants and consent forms were signed. All participants had a right to withdraw up to four weeks after their data was collected.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvesson, M., and H. Willmott. 2002. “Identity Regulation as Organizational Control: Producing the Appropriate Individual.” Journal of Management Studies 39 (5): 619–644. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00305

- Arranz, N., M. F. Arroyabe, V. Sena, C. F. Arranz, and J. C. Fernandez de Arroyabe. 2022. “University-enterprise Cooperation for the Employability of Higher Education Graduates: A Social Capital Approach.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (5): 990–999. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2055323

- Basit, T. N., A. Eardley, R. Borup, H. Shah, K. Slack, and A. Hughes. 2015. “Higher Education Institutions and Work-Based Learning in the UK: Employer Engagement Within a Tripartite Relationship.” Higher Education 70 (6): 1003–1015. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9877-7

- Boud, D., and J. Garrick, eds. 1999. Understanding Learning at Work. London and New York: Taylor & Francis.

- Boud, D., and N. Solomon. 2001. Work-based Learning: A New Higher Education? Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Bradley, A., J. Priego-Hernández, and M. Quigley. 2022. “Evaluating the Efficacy of Embedding Employability into a Second-Year Undergraduate Module.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (11): 2161–2173. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.2020748

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2019. “Reflecting on Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Qualitative Research in Sport, Exercise and Health 11 (4): 589–597. https://doi.org/10.1080/2159676X.2019.1628806

- Briscoe, J. P., and D. T. Hall. 2006. “The Interplay of Boundaryless and Protean Careers: Combinations and Implications.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 69 (1): 4–18. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.09.002

- Byrne, D. 2022. “A Worked Example of Braun and Clarke’s Approach to Reflexive Thematic Analysis.” Quality & Quantity 56 (3): 1391–1412. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-021-01182-y

- Donald, W., Y. Baruch, and M. Ashleigh. 2017. “Boundaryless and Protean Career Orientation: A Multitude of Pathways to Graduate Employability.” In Graduate Employability in Context: Theory, Research and Debate, edited by M. Tomlinson, and Leonard Holmes, 129–150. London: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Eberhard, B., M. Podio, A. P. Alonso, E. Radovica, L. Avotina, L. Peiseniece, M. C. Sendon, A. G. Lozano, and J. Solé-Pla. 2017. “Smart Work: The Transformation of the Labour Market due to the Fourth Industrial Revolution (I4. 0).” International Journal of Business & Economic Sciences Applied Research 10 (3): 47–66.

- Felstead, A., and L. Unwin. 2016. “Learning Outside the Formal System – What Learning Happens in the Workplace, and How Is It Recognised? Future of Skills & Lifelong Learning: Evidence Review.” Foresight, UK Government Office for Science. https://www.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/590493/skills-lifelong-learning-workplace.pdf.

- Garsten, C. 1999. “Betwixt and Between: Temporary Employees as Liminal Subjects in Flexible Organizations.” Organization Studies 20 (4): 601–617. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840699204004

- Gateways to the Professions Collaborative Forum. 2013. Common Best Practice Code for High Quality Internships. https://assets.publishing.service.gov.uk/government/uploads/system/uploads/attachment_data/file/251483/bis-13-1085-best-practice-code-high-quality-internships.pdf.

- Gibbs, Graham. 1988. Learning by Doing: A Guide to Teaching and Learning Methods. Oxford: Further Education Unit, Oxford Polytechnic.

- Gotsi, M., C. Andriopoulos, M. W. Lewis, and A. E. Ingram. 2010. “Managing Creatives: Paradoxical Approaches to Identity Regulation.” Human Relations 63 (6): 781–805. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726709342929

- Hall, D. T. 1996. “Protean Careers of the 21st Century.” Academy of Management Perspectives 10 (4): 8–16. https://doi.org/10.5465/ame.1996.3145315

- Hall, D. T. 2004. “The Protean Career: A Quarter-Century Journey.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 65 (1): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2003.10.006

- Hall, D. T., and P. H. Mirvis. 1995. “The New Career Contract: Developing the Whole Person at Midlife and Beyond.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 47 (3): 269–289. https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1995.0004

- Hall, D. T., J. Yip, and K. Doiron. 2018. “Protean Careers at Work: Self-Direction and Values Orientation in Psychological Success.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 5 (1): 129–156. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-032117-104631

- Hinnings, C. R., and R. Greenwood. 2002. “ASQ Forum: Disconnects and Consequences in Organization Theory?” Administrative Science Quarterly 47 (3): 411–421. https://doi.org/10.2307/3094844

- Illeris, K. 2012. “Learning and Cognition.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Learning, edited by P. Jarvis, and M. Watts, 18–27. London: Routledge.

- Jackson, D., and A. Rowe. 2023. “Impact of Work-Integrated Learning and co-Curricular Activities on Graduate Labour Force Outcomes.” Studies in Higher Education 48 (3): 490–506. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2145465

- Johns, Christopher. 1995. “Framing Learning Through Reflection within Carper's Fundamental Ways of Knowing in Nursing.” Journal of Advanced Nursing 22 (3): 226–234.

- Kapareliotis, I., K. Voutsina, and A. Patsiotis. 2019. “Internship and Employability Prospects: Assessing Student’s Work Readiness.” Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 9 (4): 538–549. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-08-2018-0086

- Kim, Y. A., K. A. Kim, and N. Tzokas. 2022. “Entrepreneurial Universities and the Effect of the Types of Vocational Education and Internships on Graduates’ Employability.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (5): 1000–1009. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2022.2055324

- Kolb, David. 1984. Experiential Learning: Experience as the Source of Learning and Development. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

- Koskinen, K. U., P. Pihlanto, and H. Vanharanta. 2003. “Tacit Knowledge Acquisition and Sharing in a Project Work Context.” International Journal of Project Management 21 (4): 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0263-7863(02)00030-3

- Lang, R., and K. McNaught. 2013. “Reflective Practice in a Capstone Business Internship Subject.” Journal of International Education in Business 6 (1): 7–21. https://doi.org/10.1108/18363261311314926

- Lave, J., and E. Wenger. 1991. Situated Learning: Legitimate Peripheral Participation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Lester, S., and C. Costley. 2010. “Work-Based Learning at Higher Education Level: Value, Practice and Critique.” Studies in Higher Education 35 (5): 561–575. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070903216635

- Okolie, U. C., H. E. Nwosu, and S. Mlanga. 2019. “Graduate Employability: How the Higher Education Institutions Can Meet the Demand of the Labour Market.” Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 9 (4): 620–636. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-09-2018-0089

- Parker, J. 2018. “Undergraduate Research, Learning Gain and Equity: The Impact of Final Year Research Projects.” Higher Education Pedagogies 3 (1): 145–157. https://doi.org/10.1080/23752696.2018.1425097

- Perusso, A., and R. Wagenaar. 2022. “The State of Work-Based Learning Development in EU Higher Education: Learnings from the WEXHE Project.” Studies in Higher Education 47 (7): 1423–1439. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2021.1904233

- Raelin, J. A. 1997. “A Model of Work-Based Learning.” Organization Science 8 (6): 563–578. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.8.6.563

- Raelin, J. A. 2008. Work-based Learning: Bridging Knowledge and Action in the Workplace. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

- Ryder, M., and C. Downs. 2022. “Rethinking Reflective Practice: John Boyd’s OODA Loop as an Alternative to Kolb.” The International Journal of Management Education 20 (3): 100703. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijme.2022.100703

- Santos, G. G. 2020. “Career Boundaries and Employability Perceptions: An Exploratory Study with Graduates.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (3): 538–556. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1620720

- Sargent, L. D., and S. R. Domberger. 2007. “Exploring the Development of a Protean Career Orientation: Values and Image Violations.” Career Development International 12 (6): 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1108/13620430710822010

- Scholtz, D. 2020. “Assessing Workplace-Based Learning.” International Journal of Work-Integrated Learning 21 (1): 25–35.

- Schön, Donald. 1983. The Reflective Practitioner: How Professionals Think in Action. New York: Basic Books.

- Scott, C. L. 2015. The Futures of Learning 2: What Kind of Learning for the Twenty-First Century. Paris: UNESCO Education Research and Foresight.

- Sides, C., and A. Mrvica. 2007. Internships: Theory and Practice. New York: Routledge.

- Svanström, M., F. J. Lozano-García, and D. Rowe. 2008. “Learning Outcomes for Sustainable Development in Higher Education.” International Journal of Sustainability in Higher Education 9 (3): 339–351. https://doi.org/10.1108/14676370810885925

- Van de Werfhorst, H. G. 2014. “Changing Societies and Four Tasks of Schooling: Challenges for Strongly Differentiated Educational Systems.” International Review of Education 60 (1): 123–144. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-014-9410-8

- Vince, R. 1998. “Behind and Beyond Kolb's Learning Cycle.” Journal of Management Education 22 (3): 304–319.

- Vince, R. 2002. “Organizing Reflection.” Management Learning 33 (1): 63–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1350507602331003

- Wall, T., A. Hindley, T. Hunt, J. Peach, M. Preston, C. Hartley, and A. Fairbank. 2017. “Work-Based Learning as a Catalyst for Sustainability: A Review and Prospects.” Higher Education, Skills and Work-Based Learning 7 (2): 211–224. https://doi.org/10.1108/HESWBL-02-2017-0014

- Watson, T. J. 2009. “Narrative, Life Story and Manager Identity: A Case Study in Autobiographical Identity Work.” Human Relations 62 (3): 425–452. https://doi.org/10.1177/0018726708101044

- Zopiatis, A. 2007. “Hospitality Internships in Cyprus: A Genuine Academic Experience or a Continuing Frustration?” International Journal of Contemporary Hospitality Management 19 (1): 65–77. https://doi.org/10.1108/09596110710724170