ABSTRACT

The importance of creativity for survival in modern society is well recognised. However, the development of creative thinking skills through formal education still needs more attention, and the assessment of creative thinking skills using valid models in higher education is under-researched. Our paper presents the deficits and improvements in first-year business and economics undergraduates’ creative thinking skills using an authentic assessment task (product). We assessed creativity under three broad themes: creative expression, knowledge creation and creative problem solving, as presented in the OECD Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA). These themes were chosen to reflect students’ domain-specific expertise, motivations and creative thinking skills. Our analysis finds areas where students have deficits in creative thinking skills and how they have improved those skills through the assessment task. These findings imply the importance of providing students with opportunities to enhance creative thinking, mainly through the application of their learning. Our study provides insights into pedagogical strategies and assessment practices to enhance the creativity required from graduates in any field.

1. Introduction

Creativity is necessary for survival in a constantly changing modern world (Alencar, Fleith, and Pereira Citation2016; Csikszentmihalyi Citation2007; Florida Citation2004; Karpova, Marcketti, and Barker Citation2011). It is a forerunner of innovation, which is essential for the development of human society; therefore, creative labour is crucial (Shalley, Gilson, and Blum Citation2009). The elevated importance of creativity and innovation has economic, social, and cultural significance (Sawyer Citation2012; Smith-Bingham Citation2006): for example, creativity is an engine of economic and technical development (Sternberg and Lubart Citation1999), essential for developing new ideas, increasing efficiency, and devising solutions to complex problems (Plucker, Beghetto, and Dow Citation2004). Creative thinking helps professionals to succeed in complex problem-solving and decision-making processes and successfully adapt to the demands of daily life (AACSB Citation2010; Jackson Citation2006; Lindberg et al. Citation2017; Morris and König Citation2020; Smith-Bingham Citation2006; Verzat, O’Shea, and Jore Citation2017).

The importance of creative thinking has been intensified and made prominent by rapid globalisation, increasing competition, technological enhancements (Alencar, Fleith, and Pereira Citation2016), and uncertainties and complexities imposed by global phenomena such as the Covid-19 pandemic. Creativity not only leads to societal progress through inventions and discoveries; it also helps society to progress by changing the way people relate to the world, to others, and to themselves, making them more flexible and open to changes (Glaveanu et al. Citation2020). Creativity is also associated with other cognitive activities, such as leadership, critical thinking, decision-making, metacognition, and motivational and behavioural factors (Feldhusen and Goh Citation1995; Zacher and Johnson Citation2015; Zhang et al. Citation2018). It can be improved over time by enhancing domain-specific skills and knowledge, and a stimulating environment for individuals’ cognitive processes and personality factors, including motivations (AACSB Citation2010; Karpova, Marcketti, and Barker Citation2011). Therefore, higher education institutions need to actively facilitate a supportive environment, resources, and opportunities that enhance creativity; so that it becomes an explicit part of students’ higher education experience (Hannon, McBride, and Burns Citation2004; OECD Citation2016; Ungaretti et al. Citation2009; Vincent-Lancrin et al. Citation2019; World Economic Forum Citation2020).

Creativity is paramount for the business sector; it promotes innovation, boosts productivity, helps flexibility and adaptability, and fosters growth. Therefore, business and economics professionals must be equipped with creative thinking skills, among other skills and competencies (which may also be closely associated with creative thinking). An innovative, interdisciplinary model that enhances creativity (as a part of broad skills and competency development approach) is required to improve business education and to prepare business students to work effectively to address the complex, undefined, wide-impact challenges of real-world business problems (Ungaretti et al. Citation2009). For these reasons, the business sector has heavily invested in creativity education (Plucker, Beghetto, and Dow Citation2004). Although the importance of creativity and higher education institutions’ role in enhancing creativity is widely recognised, not all higher education institutions devote significant attention to fostering creativity through their curriculum (Fekula Citation2011; Kerr and Lloyd Citation2008; Schmidt-Wilk Citation2011; Weick Citation2003). Research also suggests that teachers need to be trained and supported to provide students with strategies, approaches, resources, and the environment to promote creativity (Vincent-Lancrin et al. Citation2019). Our study is important to creativity research in two ways. First, it provides an empirical assessment of creativity using an assessment task designed to improve the creative thinking skills of a cohort of first-year undergraduate students in the field of business and economics. Our assessment, therefore, is based on a product created by students; it includes assessing both domain-specific and domain-general aspects of creative thinking, which is rare in creativity literature (Baer Citation2016). Secondly, our study used a comprehensive model of creative thinking, which is developed using various key aspects of creativity discussed by many scholars in the literature (for example, Amabile Citation1983; Citation1996). Such studies are limited in creative thinking literature focusing on higher education. Therefore, our paper fills excessive gaps in the existing creativity literature.

Assessment of creative thinking in higher education is hampered by the lack of good measures of creativity (Baer Citation2016; Kaufman and Beghetto Citation2009). Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking, the widely used tests in assessments of creative thinking, have been questioned lately for their focus on assessing domain-general creativity and its relevance for the twenty-first century (Baer Citation2016). We applied the creative thinking framework designed for the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA) to the higher education context of our study. We selected this framework for its close representation of the componential theory, Consensual Assessment Technique (CAT), in which the creative product is independently assessed by experts in the domain and the nature of the task we used to assess creative thinking in this study. Using this framework, we assess deficits and improvements in various aspects of creative thinking demonstrated in a two-stage assessment task before and after a feedback process. We also evaluate the association between the feedback process and improvements in creative thinking using quantitative and qualitative methods. The PISA framework comprehensively covers all aspects of creative thinking related to business and economics. The framework also highly relates to our student cohort and the nature of the assessment task used in this study. Our student cohort mostly has 19-year-olds in the first semester of their bachelor’s degree. The assessment task required students to write a report (a narrative) after analysing a set of data given to them. Our contribution to the creative thinking literature is novel as it uses a comprehensive framework to assess creativity in business students in a higher education setting. Assessment of both students’ deficits and improvements, along with an understanding of various educational and demographic characteristics associated with those aspects, provide valuable pedagogical underpinning on improving a highly essential employability skill for business and economics students. Importantly, gaining this understanding at an early stage of students’ degree programmes is critical, as this permits early intervention in finding and minding gaps. Though our study uses a cohort of business students, the creative thinking framework we used in the research and our findings can be applied to other fields. Our study provides important insights into pedagogical strategies and assessment practices that facilitate the development of creative thinking and other skills and competencies.

Our study aims to address the following research questions:

RQ1: Which specific dimensions of creative thinking do students perform well and find challenging?

RQ2: What are the characteristics of students performing well in different domains of creative thinking?

RQ3: What conclusions can be drawn from the differences in creative thinking scores between the draft and the final reports, including the usefulness of feedback?

RQ4: What can business instructors do to enhance creative thinking abilities among business students?

1.1. Creative thinking: theoretical underpinning

According to Sternberg and Lubart (Citation1999), creativity is the ability to produce work that is both novel and appropriate, which is useful and adaptive for the task constraints. Plucker, Beghetto, and Dow (Citation2004, 90) define creativity as ‘the interaction among aptitude, process, and environment by which an individual or group produces a perceptible product that is novel and useful as defined within a social context’. The concept of aptitude relates creativity as a skill set (rather than a static trait). Aptitudes such as flexibility in thinking, perseverance and task motivation can be influenced through experience, learning, and training. The creative process refers to how people approach problems and solutions and their capacity to combine existing ideas in new combinations (Amabile Citation1996). Such a process requires domain-specific expertise and skills linked closely with critical thinking and problem-solving skills.

Most of the recent research is established on earlier creative thinking research, including the componential model of creativity proposed by Amabile (Citation1983, Citation1996). This model identifies three within-individual components that affect creativity: domain-specific skills, creativity-relevant processes, and task motivation. Domain-specific skills include knowledge, expertise, technical skills, intelligence, or talent related to the problem. Creativity-relevant processes are individuals’ cognitive skills in generating new ideas. Individuals’ cognitive styles and personality characteristics may influence their independence, risk-taking, and openness to new perspectives on problems. Task motivation refers to an individual’s intrinsic motivation to complete a task. Individuals are more creative when motivated primarily by the interest, enjoyment, satisfaction, or the challenge the work brings, compared to extrinsic motivating factors such as surveillance or competition (Amabile Citation1996). This model is supported by a considerable body of data (Plucker, Beghetto, and Dow Citation2004).

In assessing creative thinking, Rhodes (Citation1961) offers four components (the 4Ps): person, process, product, and press. Person refers to what makes people creative: curiosity, resilience, and willingness to take risks. The creative process involves skills and strategies the person uses to develop the product. Product is the result of creative activities, and the press is the environment in which the person operates to create the product.

Creative thinking is a tangible competence grounded in knowledge and practice and supports individuals in achieving better outcomes, often in constrained and challenging environments (OECD Citation2022). The thinking process associated with creativity improves other skills and competencies, including metacognitive capacities, problem-solving skills, academic achievement, future career success, and social engagement (Barbot and Heuser Citation2017; Gajda, Beghetto, and Karwowski Citation2017; Long and Plucker Citation2015; Plucker, Beghetto, and Dow Citation2004). Researchers also establish the connection between creative and critical thinking as distinct, yet related higher-order cognitive skills (Vincent-Lancrin et al. Citation2019).

Traditional education systems primarily focus on conceptual knowledge development and do not provide mechanisms for enhancing creativity (Lindberg et al. Citation2017; Verzat, O’Shea, and Jore Citation2017), particularly in societies where conditions are rapidly changing (Morris Citation2022). The componential theory (Amabile Citation1996), a comprehensive model of the social and psychological components necessary for an individual to produce creative work, provides the scope for improving creativity through both skills and motivation within the individual and the external environment in which the individual engages in the creative process. In higher education, this can be related to providing students with the best opportunities for mastering domain-specific skills (including content knowledge and related skills, such as communication), stimulating creativity through various techniques, such as brainstorming activities, self-directed learning pedagogies, and providing an encouraging environment for creativity, such as enhancing intrinsic motivation (Lindberg et al. Citation2017; Morris Citation2022; Verzat, O’Shea, and Jore Citation2017).

In a more recent study, the Australian Council for Educational Research (ACER) defines creative thinking as ‘the capacity to generate many different kinds of ideas, manipulate ideas in unusual ways and make unconventional connections in order to outline novel possibilities that have the potential to meet a given purpose elegantly’ (Ramalingam et al. Citation2020, 5). Underlining this definition, creative thinking is a skill that can be learnt, and contains both domain-specific and domain-general aspects. In the definition, ‘generating many kinds of ideas’ refers to the quantity and the originality of ideas and their usefulness and relevance. The PISA framework developed by OECD defines creative thinking as ‘the competence to engage productively in the generation, evaluation, and improvement of ideas that can result in original and effective solutions, advances in knowledge, and impactful expressions of imagination’ (OECD Citation2022, 11). This definition focuses on the cognitive processes and outcomes associated with creativity.

Given the significance of creativity, proper assessment of creative thinking is extremely useful; however, assessment of creativity has been mostly a failure rooted in the assumption of domain-generality: that the creative thinking in one domain can be applied to any other domain (Baer Citation2016). Domain-specific creative thinking refers to the creative application in a particular domain that requires domain-specific knowledge. Torrance Tests of Creative Thinking (TTCT), which dominated creativity assessment for over half a century, mainly assumes domain generality. However, creativity is a development construct that exhibits domain-general and domain-specific characteristics (Baer Citation2016; Plucker, Beghetto, and Dow Citation2004). Research-based frameworks developed to assess education-based creative thinking are scarce and mostly limited to primary and secondary school settings. Among the three such models published, the most recent ones are ACER’s creative thinking skill development framework (Ramalingam et al. Citation2020) and PISA’s Creative thinking framework (OECD Citation2022). The ACER framework includes three strands that encompass creative thinking: generating ideas (number and range), experimenting with ideas (shifting and manipulating), and generating quality ideas (fitness for purpose, novelty, and elaboration). The assessment of creative thinking in the PISA framework (OECD Citation2022) covers both domain-general and domain-specific aspects of creative thinking. This framework closely follows the componential theory suggested by Amabile (Citation1983, Citation1996). It covers three broad thematic content areas: (1) creative expression, (2) knowledge creation, and (3) creative problem-solving. Creative expression refers to one’s ability to communicate thoughts to others through written and visual expression. Knowledge creation refers to advancing knowledge and understanding, emphasising making progress, for example, by improving ideas. Creative problem-solving is a distinct class of problem-solving characterised by novelty, unconventionality, and persistence. These broad themes link to the formal definitions of creative thinking, including interactions between domain-specific expertise, the cognitive process needed for creative thinking, and task motivations. Further, the PISA framework is closely related to the Consensual Assessment Technique, in which experts in a domain independently assess the creative product and arrive at mean ratings. Our assessment of creative thinking also uses an educational product (data analysis report), and our method of assessing that product, as described in the methods section, is closely related to this technique.

2. The current study

2.1. Study context, student cohort, and the assessment

Our study uses a random sample of group reports submitted by a cohort of first-year business statistics students enrolled in a Bachelor of Commerce program (BCom) at a large research-intensive university in Australia (n = 104; 17.2% of total group assignments) in 2021. Students completed this report as part of an assessment in business statistics (B-Stat), a first-year core subject in the BCom program. This subject provides a foundation for the quantitative decision analysis skills required by business professionals in accounting, economics, finance, management, and marketing. The topics covered include graphical methods, descriptive statistics, probability, and statistical inference; Microsoft Excel is used for data presentation and analysis. compares some of the available characteristics of the student cohort with the simple random sample we selected for this study. The student cohort in B-Stat is demographically highly diverse; it has about 49.4% international students from 46 different countries, of which 70% are Chinese nationals. Our sample has a slightly higher percentage of international students (53.3%), but this does not have a distortionary effect on results, given that both domestic and international students are sufficiently represented. The subject also receives a small group (around 10%) of Bachelor of Arts (BA) students who will major in economics within the BA program. The skills and competencies related to creative thinking aspects we assess in this study can differ and depend on these students’ cultural, academic, and socioeconomic backgrounds. For example, the quality and the nature of primary and secondary education, and the opportunities students have had to develop creative thinking skills in their home countries, can significantly impact how students perform in the creative thinking domains.

Table 1. The composition of the sample.

The assessment B-stat students completed provides an excellent base for assessing all domains of creative thinking skills used in the PISA framework. The assessment required students to write a data analysis report using discipline-specific, real-world data and submit the report in two stages: a draft and the final version. The task expected students to describe, visualise and summarise data using graphical and descriptive techniques, analyse data using descriptive and inferential methods, and write a narrative in a report format discussing their findings to a non-technical audience. A rubric that specifies the expectations was given with the task. Each group first submitted the draft version of the report in week 6 (which contributed 30% of the total available marks for the assessment task); then, they received personalised written feedback from the markers during the feedback period. The feedback students received closely links with the creative thinking aspects, as students’ work predominantly targets generating and presenting various ideas creatively in visual and written formats, scientifically analysing and evaluating ideas, and relating their work with various social phenomena. Students were asked to resubmit a final version of the report in week 12, where they were expected to incorporate the feedback they received when working on the final submission. This assessment was a pedagogical intervention introduced to enhance deeper learning of the statistical concepts and knowledge transfer by using the theory in practice and developing employability skills.

In the semester this study was conducted, students received data on Gross Domestic Product (GDP) and obesity rates measuring economic and health conditions, and Covid-19 Case Fatality Rates (CFR) for 123 countries. Students wrote the report summarising interesting features of distributions of prosperity, obesity, and Covid-19 mortality rates in different countries and regions, describing relationships between these socioeconomic variables, and comparing the variations at the country and regional levels. Students completed the project in groups of up to four students.

2.2. The framework for assessing creative thinking

In the absence of a framework for assessing creative thinking in higher education, we settled with the PISA framework to assess the creative thinking skills of our first-semester undergraduate students (primarily 19-year-olds). We chose an authentic assessment task that involved activities reflecting creative thinking skills for the evaluation. The components of the PISA creative thinking framework provide coverage of the creative thinking themes as suggested by Amabile (Citation1996), Sternberg and Lubart (Citation1999), and Plucker, Beghetto, and Dow (Citation2004), including domain-specific knowledge, cognitive skills, motivations, and openness for novel ideas. The elements in this framework also assess components essential for business professionals, and directly relate to the activities our students completed for their assessment. The PISA framework assesses students’ creativity nearing the end of compulsory schooling; our study assesses students who have just entered higher education. For these reasons, we adopted the PISA framework for our study.

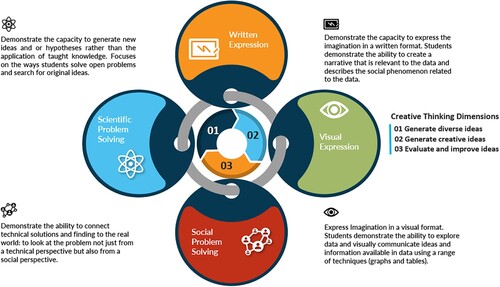

The PISA creative thinking domains reflect the realistic display of creative thinking of young adults; it covers three broad themes: (i) creative expression, (ii) knowledge creation, and (iii) creative problem-solving. This process involves generating ideas, reflecting upon them by valuing their relevance and novelty, and iterating upon them until a satisfactory outcome is achieved. These themes are organised into three specific facets for measurement purposes: generate diverse ideas, generate creative ideas, and evaluate and improve ideas. As reflected in , these facets are at the core of our framework for assessing creativity. In our framework, generating diverse ideas refers to students’ capacity to think flexibly by generating multiple ideas distinct from each other (number of ideas). Generating creative ideas focuses on students’ capacity to generate relevant, useful, and novel ideas. Evaluating and improving ideas refers to students’ capacity to evaluate limitations in ideas and improve them. The evaluation of ideas in our context relates to students improving their ideas (both number and quality) through self-assessment and using the feedback given to them.

Each facet in this core links to four domains that assess students’ creative thinking. These four domains: written expression, visual expression, scientific problem solving, and social problem solving, assess the primary learning outcomes of the assessment task students completed: students’ ability to use statistical tools to create a data analysis report analysing and presenting characteristics in domain-specific, real-world data to a non-expert audience. Generating and evaluating ideas through this cognitive process requires students to select appropriate statistical methods to visualise and analyse data, correctly use them to obtain results, and create a narrative in written form. Creative engagement in knowledge creation and creative problem-solving involves more functional employment of creative thinking related to investigating open questions or problems that do not have a single solution (OECD Citation2022). This thematic area includes scientific problem-solving and social problem-solving domains. Creative thinking in the social problem-solving context involves looking at the problem from both a technical and a social perspective. These two domains are characterised by generating original, innovative, effective, and efficient solutions. Knowledge creation and creative problem-solving directly apply to the assessment we use in this study. Both handling real-world data through exploration and analysis using statistical tools and relating technical findings to real-world scenarios require creative thinking processes around problem-solving and knowledge creation. The assessment task students complete is an open task with no unique solution; students can use their creative thinking to assess the data and find various characteristics related to economic and social phenomena. Scientific problem-solving in this assessment relates to students’ ability to probe multiple research questions and hypotheses that can be gauged from the data, and test those hypotheses using the techniques they learned in the subject. Therefore, this assessment focuses on generating new ideas from the information available in data (such as characteristics of data, relationships, and differences between economic variables) rather than just applying the taught knowledge (techniques) to solve problems.

further illustrates the key activities and outcomes from the assessment, which demonstrate creative thinking under each of the four domains. Firstly, the task facilitates students to generate diverse and creative ideas by analysing (scientific problem-solving) and presenting data (visual and written expression). Through the process, students not only find and present various interesting characteristics and relationships in the data but also make their relevance to practical economic and business phenomena (social problem-solving). This idea generation is a crucial component of creative thinking (Clapham Citation1997; McAdam and McClelland Citation2002; Milgram Citation1990), and it facilitates increased possibilities for developing preferred solutions to problems (Clapham Citation1997). Secondly, the task’s collaborative nature and dual submission process encourage students to evaluate their ideas both individually and collaboratively with the assistance of feedback, and improve on the report (product).

Table 2. Linking creative thinking framework with the data analysis report.

3. Method

We selected a random sample of 104 groups involving 240 students from a population of 605 groups (1180 students) who submitted the assessment task. The random sample contains 17.2% of groups and 20.3% of students. We downloaded each group’s submitted draft report, the feedback markers provided, and the final report. Then, using the creative thinking framework described in Section 2.3, we assessed each group’s performance in all aspects of creative thinking, first presented in the draft report (before feedback) and then in the final report (after feedback). Some characteristics of the student cohort involved in the study are described and compared in . Besides the slight oversampling of the international student cohort, our sample represents the student population well. Given the large sample size, we do not expect any significant bias in our results due to this slight oversampling of international students.

We recruited two markers (who were also tutors in this subject) to remark group reports against the three dimensions (each containing four domains) described in the creative thinking framework. The markers equally shared the marking load, and their marking across a sample of 10 assignments was compared for consistency before moving to mark their share of the reports. This process enabled a reliability check of the creative thinking scores (interrater validity check) across the two markers.

Markers were provided with a template consisting of creative thinking domains under each dimension and the expected activities and outcomes under each of them. For each criterion, they recorded a score between 0 and 4 (0 = no attempt, 1 = novice, 2 = reasonable, 3 = competent, 4 = excellent). They also provided specific textual feedback on each criterion, describing the level at which they performed or met the expectations. Each tutor marked the draft and final versions of the assignments against the same 12 categories (four domains under three dimensions). They also analysed the feedback provided for the group’s draft assignment by their original marker using a 0–4 scale (0 = no feedback given; 1 = very little feedback; 2 = some feedback; 3 = mostly relevant; 4 = excellent). They marked each of the drafts, tutor feedback and the final for each group before moving to the next set of assignments. This process allowed tutors to evaluate each of the critical thinking aspects presented in the draft report, understand if the feedback was targeted to the area of creative thinking that students could improve on, and gauge if the group had responded to the feedback in the final version. They provided a spreadsheet detailing their ratings and specific text-based comments (i.e. the data), which we later analysed.

We add scores under each dimension and the domains under them separately to get the dimension-specific and domain-specific total scores. How each of these scores is calculated is further illustrated in . Accordingly, each dimension has 16 marks available; and each domain adds up to 8 points. We use the differences in the rankings between the draft and the final reports as the quantitative measure of students’ ability to evaluate and improve ideas (creative thinking dimension 3).

Table 3. Measuring creative thinking using rubric scores.

This paper also uses marks available for the other assessment tasks of the subject, feedback tutors have given for the draft version of the data analysis report, responses from a tutor survey, and demographic data collected from the central administration system (age, gender, and international and local status of the students). The study received ethics approval to use these marks, demographic data, de-identified assignments, and feedback given to students to assess creative thinking skills and evaluate the tutors’ feedback.

We use quantitative and qualitative methods to analyse the data collected through the abovementioned process. The quantitative methods include a graphical and descriptive analysis of creative thinking scores provided by markers under each dimension and domain. We further use hypothesis tests to compare and contrast differences in students’ performances in various creative thinking aspects and regression analysis to estimate correlations between group characteristics and creative thinking scores. We also use these methods to find improvement in creative thinking scores across the two submissions and the role that feedback plays in improving those scores. The qualitative techniques include a thematic analysis of text responses provided by markers to identify key themes expressed in the draft reports, the feedback given, and the final reports. This analysis includes labelling and coding the markers’ feedback into the pre-identified themes according to the framework, and analysing those themes based on identified patterns.

4. Results

We present below our results based on the first three research questions presented in section 3.1 (the fourth research question is addressed in the discussion section).

4.1. Assessment of creativity by dimensions: performance and improvements (RQ1 & RQ3)

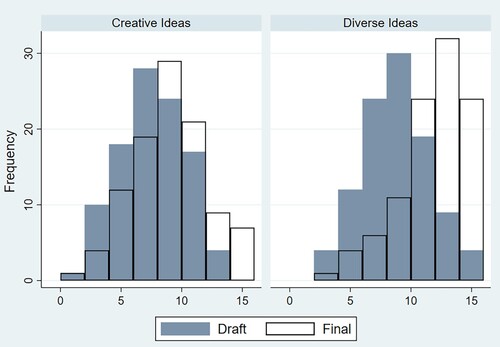

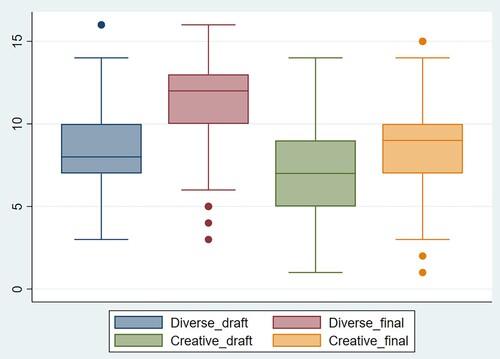

This section summarises our findings for research questions 1 and 2; students’ group performance in generating (diverse and creative), evaluating, and improving ideas. For this analysis, we use summary statistics of creative thinking scores (by dimension) provided in Panel A in , and . Our results show that students’ initial performance in generating ideas is moderate. For example, on average, students only scored just above 50% (8.36/16) and below 50% (7.11/16) for generating diverse and creative ideas for the draft report, respectively. The lower quartile (bottom 25% of the students) only scored 7 or less (for diverse ideas) and 5 or less (for creative ideas) for these two dimensions. The difference in the middle of the score distribution (measured by the inter-quartile range: Q3–Q1 = 9–5 = 4) is exceptionally high for creative idea generation.

Figure 2. Distribution of Scores for the creative ideas and diverse ideas dimensions. Note: Each of the four histograms represents the distribution of creative thinking scores out of 16 (the horizontal axis represents scores, and the vertical axis represents the number of students). The histograms with grey bars show the distribution of scores for the draft report and those with white bars are for the final reports. The rightward shift in white bars across the axis for both dimensions indicates the improvement in creativity scores.

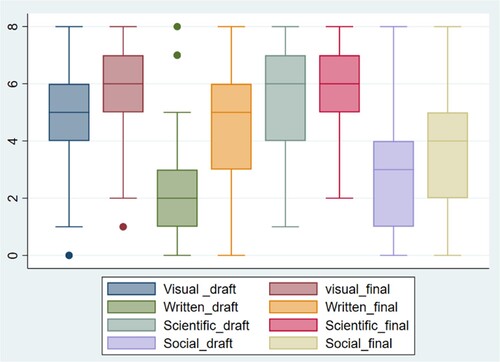

Figure 3. Distribution of Scores for the Creative Ideas and Diverse Ideas Dimensions. Note: Vertical axis presents creative thinking scores out of 16 for each dimension. For each whisker, the bottom and top lines are the minimum and the maximum score respectively. The bottom, middle and top lines in boxes reflect the 25th, 50th (median) and 75th percentiles for the scores. The dots show the outliers. The upward shifts in each statistic between the draft and the final versions indicate improvements in scores.

Table 4. Summary statistics for performance in creative thinking skills.

Students improved on generating both diverse and creative ideas across the two submissions. The last column in Panel A of presents these scores’ average and percentage change. As shown here, the average differences in scores between the draft and the final reports (3 for generating diverse ideas and 1.5 for generating creative ideas) are statistically significant at a 1% significance level. Such improvement in scores can also be seen at each level of the score distribution, as presented in the quartiles (for example, scores for the first quartile increased from 7 to 10 for generating diverse ideas) and graphically, both from the rightward shift in the histograms (from blue bars to white bars) presented in and the upward shift in the boxplots and whiskers from the draft to the final shown in .

Our analysis reveals that students are better at, and improved more on, generating diverse ideas (number of ideas) compared to generating creative ideas (quality and originality). This is reflected in the higher average (8.36 vs 7.11 – this difference is statistically significant at a 1% significance level) and percentiles for generating ideas compared to generating creative ideas. These differences are also visually reflected in the grey box and whiskers in , which sit higher than the green box and the whiskers and the two histograms with blue bars in . For example, histograms reveal that the proportion of groups who scored more than half of the available points (i.e. 8 or more) for generating diverse ideas (62%) is much higher than the corresponding proportion for developing creative ideas (45%).

Improvement in generating diverse ideas is much more significant than improvement in generating creative ideas (percentage improvement in diverse idea generation is 18.6% compared to 9.4% for creative ideas). This makes sense from a practical point of view, as giving students feedback on generating diverse ideas was much easier than generating creative ideas.

Our analysis also suggests a strong positive relationship between students’ ability to generate diverse and creative ideas (correlation coefficient of 0.80 and 0.81 for the draft and final reports, respectively). This means, on average, students who can identify various characteristics in data as ideas can creatively express them well. This interdimensional relationship in creative thinking reveals an important point from a pedagogical perspective. When students are provided with opportunities to improve on one dimension of creative thinking, that primarily supports improvements in the other dimensions.

While our research design does not provide ground to make causal statements, based on markers’ ranking of the feedback for the individual report and students’ responses to the survey question on the usefulness of feedback, at least part of this improvement can be credited to the feedback students received for the draft report.

4.2. Domain-specific creative thinking abilities: performances and improvements (RQ2 and RQ3)

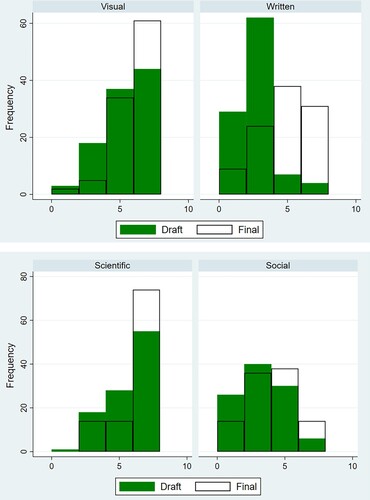

This section summarises our results for domain-specific creative thinking. illustrates key features in Panel B of (the distribution of these scores by domain is also presented in ). Of the four domains of creative thinking we investigated, students initially performed better in the visual expression of ideas and scientific problem-solving. This is reflected in the higher average score and percentile scores for each percentile. For example, the average score for scientific problem-solving is 5.38 compared to 2.36 and 2.84 for written expression and social problem-solving, respectively. These statistics are illustrated in , Panel B, along with the boxplots in . This difference in the scores is acceptable for the draft report since students are taught to use statistical tests and graphical methods to analyse and present data, in contrast to presenting findings in written format or relating statistical findings to social phenomena. Expressing original ideas and statistical results in written form is a new skill for many students, particularly challenging for the international student cohorts whose first language may be something other than English. This finding also aligns with the lecturers’ general conception and experiences in these courses. Even when students are good at ‘numbers crunching’ (performing statistical tests, for example), they still struggle to interpret their findings and specifically relate those findings to real-world scenarios.

Figure 4. Presentation of summary statistics for creative thinking domains. Note: Vertical axis presents creative thinking scores out of 8 for each domain.

Our data reveal a moderate positive relationship between students’ ability to scientifically express ideas with visual and social expression domains (correlation coefficients are 0.50 and 0.57, respectively) and between written expression of ideas and social problem solving (the correlation coefficient is 0.60).

Students demonstrated significant improvements in creative thinking across all four domains. Histograms in illustrate these improvements (from green to white bars); average and percentage changes are presented in the last column in , Panel B. As evident, the most improved domains are the written (26%) and visual (11.6%) expression of ideas, while scientific and social problem-solving domains improved by around 9%. The notable improvement in the written expression domain is significant, as it was one of the least-performing domains of creative thinking in the draft report. However, the slightly increased standard deviation (from 1.4 to 1.9) and interquartile range (3–1.4 = 1.6 to 6–3 = 3) both indicate an increase in the spread of marks, meaning that not all students equally improved on this skill ().

Table 5. Regression results: correlations between creative thinking and group characteristics.

Social problem-solving (students’ ability to relate statistical findings to social phenomena and problems), which is the least performed and improved domain, remains an area of concern. The relatively poor performance in this criterion confirms that students are generally good at remembering theory and performing calculations but are challenged when asked to apply theory to practice. It demonstrates the importance of giving special attention and support in enhancing transferable knowledge – the ability to use theory to solve real-world problems and scenarios. This also highlights the importance of training markers to provide feedback targeting this area of creative thinking or, in general, the importance of providing feedback to students on how to interpret statistical results and connect them to real-world scenarios.

describes the key performance improvements in generating diverse and creative ideas under each domain between the draft and the final reports and the role the feedback played in the improvements explicitly. A significant number of students showed their mastery of knowledge using statistical techniques to analyse data; they came up with various ideas and tested them using descriptive (mainly in the draft report) and inferential (in the final report) statistical techniques. Students improved on generating ideas related to all dimensions, yet the most improved was their ability to generate ideas visually by identifying characteristics in data and relationships between variables. However, there was room for improvement, as some students needed to improve on generating or presenting ideas creatively in either one or many dimensions.

Table 6. Performance differences between the draft and final reports: generating diverse and creative ideas.

Finally, analysing the feedback provided by markers reveals that an overwhelming majority of groups receive good feedback. Tutors placed emphasis on providing feedback that asked questions about specific parts of the reports, queried students’ use of statistics, and noted particular explanations of economic phenomena that could be improved in the final reports. The feedback given by the tutors was mainly clear and descriptive and included examples of how to improve a task. summarises how students evaluated and improved ideas using the feedback given to them.

Table 7. Summary of students’ performances in the evaluation and improving ideas.

4.3. Groups characteristics correlated with creative thinking skills and the role of feedback

provides insight into the group characteristics correlated with students’ creative thinking scores. As Equation 1 denotes, the average age and the ratio of international students in a group are negatively correlated with creative thinking scores for the draft report. For example, the coefficient on the ‘International Student Ratio’ reveals that having one more international student in the group, on average, would be associated with an 8% decrease in creative thinking scores. Conversely, the number of members in a group and the students’ average mark in the first mid-semester test positively correlate with the initial creative thinking scores.

The significance of the group size on scores fades away in the final report in which the feedback has a significant association with score improvements (Equation 2). Our results (coefficient of 6.91 on the ‘Read Feedback’) suggest that, on average, reading feedback is associated with a 21.6% ((6.91/32) *100) increase in their creative thinking scores, compared to the groups that tutors noted have not read feedback. Although our results cannot be used to infer a causal relationship between feedback and scores, this positive correlation is encouraging, as it provides evidence that, at least partially, feedback contributed to improving students’ overall creative thinking.

Our regressions also provide an essential revelation of the international students’ performance and improvement in creative thinking. Both regressions indicate that groups with more international students perform lower on creating thinking fates than groups with more local students. The magnitude of the coefficient is smaller in Equation 2, which denotes some improvement in the final task.

Although further research is needed to verify this reduction, our results send a strong signal to educators, highlighting the need to provide special attention to international student groups from so many different countries worldwide to improve creativity.

5. Discussion

This study investigated students’ performance and improvement in various aspects of creative thinking. Our findings are encouraging in many ways; they identify unique features of undergraduate creative thinking performance, group characteristics of those who performed well or poorly on creative thinking, and, most importantly, the significant improvement in group creative thinking scores across all dimensions and domains. According to our findings, formative feedback is essential in improving students’ creative thinking. The improvement in creative thinking, as measured by the draft and the final submissions, reveals how instructors can facilitate students’ development of valuable employability skills. This finding corresponds with the theoretical aspects of improving creative thinking, including the componential theory. The design of the task, the collaborative nature of the work, and the feedback process have provided an encouraging environment and opportunities to enhance subject-specific skills and knowledge, therefore, have facilitated students to improve creative thinking skills. This also directly answers our RQ4: authentic assessment tasks with effective feedback processes (data analysis report in our context) can enhance students’ creative thinking skills.

We concur with Miller et al. (Citation2021) that enhancing creative thinking skills in business may need domain-specific teaching and learning. Awareness of the specific domains and dimensions of creativity can provide a starting point in re-arranging or identifying the best possible teaching and learning strategies. This also includes redesigning teaching and learning activities targeted to creativity, such as collaborative activities and research projects (Wongpinunwatana Jantadej, and Jantachoto Citation2017). Several factors can influence students’ complete optimisation of creative thinking, such as motivation, prior skills, and dispositions. ‘Stickiness’ – difficulty retaining knowledge and effectively using it when needed – can also be an issue (de Villiers, Margarietha, and Maree Citation2015). Scaltsas (Citation2016) argues that transforming and redefining a problem is a key to creativity and innovation as that allows not only finding solutions to a problem but also reflecting on the applicability of conventional or past solutions. This provides an essential link to the task our students completed, as they were allowed to create a product (the report), transforming data into a narrative.

Employers continue to seek graduates skilled in creative thinking (Miller, Cruz, and Kelley Citation2021; Zhao and Zhao Citation2022). Creativity has significantly impacted enterprise growth and success (Li, Li, and Lu Citation2022). Even the linkages between the design and creative arts professions and business environments have strengthened due to their positive impact on improving business performance (Homayoun and Henriksen Citation2018; Penaluna and Penaluna Citation2009). Unsurprisingly, design thinking is increasingly becoming a feature of business education (Matthews and Wrigley Citation2017). It is argued that rewarding students for their creativity and teaching them diverse ways of thinking and risk-taking can create creative classroom environments (Driver Citation2001). Such an environment helps students develop their creative identities, mindset, and self-efficacy (Homayoun and Henriksen Citation2018).

Models and approaches have come in handy to better incorporate creative thinking skills development in business education (e.g. Sosa and Kayrouz Citation2020) in various contexts. In communication, for example, changes have been made in classroom activities and assignments to allow for more creative outputs, particularly in reflecting on the creative process and generating ideas (Golen et al. Citation1983). They have also been embedded in case method teaching, where students create cases themselves (Riordan, Sullivan, and Fink Citation2003). Providing students with a business-professional-like experience, being exposed to several issues surrounding a particular case. From this multi-faceted experience, instructors can then assess the range of creative outputs. In economics education, problem-based learning was also used to improve critical and creative thinking skills using cases (Kardoyo, Nurkhi, and Pramusinto Citation2020).

The assessment design does not permit us to find causal relationships between students’ academic and socioeconomic characteristics and the feedback process on creative thinking. For fairness reasons, the entire cohort of students was involved in writing the data analysis report, and the feedback they received was fairly consistent. This prevented us from having a control group to compare the impact of feedback and other characteristics on improvements in creative thinking. Our study does not warrant any suggestions on how individual students’ creative thinking has changed due to this exercise (or feedback), as we used a group assignment in the study. There are ample areas in the creative thinking context where further research is needed.

6. Conclusion

Creativity is paramount to the survival of any field and everyday life; it has particular importance for business and economics professions. In this paper, we assessed how undergraduate students demonstrated creativity through an exercise involving data analyses and presentations. We assessed students’ ability to generate and present multiple creative ideas using data, test their ideas using statistical methods, relate their findings to socioeconomic characteristics or problems, and their ability to evaluate their ideas and improve them. We adopted a framework to analyse creative thinking hoping for a more nuanced assessment of where these deficiencies lie. We recognised some areas for improvement in creative thinking and ongoing challenges facing business educators in helping students develop these skills. While, based on our sample, we understand that some of those deficiencies have been addressed by giving students early feedback on their work, thus improving their final submissions, we also recognise that there are persistent challenges in developing students’ creative thinking skills to acceptable levels.

We have tinkered with several ways to improve creative thinking, but a more strategic approach would be better than simple curriculum-related fixes. Instructors have attempted to address this issue by offering specific courses or programmes designed to teach creative thinking or embedding opportunities to teach learning and assessment activities, such as redesigning assessments to allow students to display their creativity or by providing more collaborative learning tasks to explore classroom tasks in innovative ways. While we expect students to be creative and therefore develop creative thinking to meet future work requirements, it is also essential to create opportunities where these skills are displayed in the curriculum. The combination of learning design, using technology, active learning strategies, authentic assessments, and experiential learning can play a crucial role in allowing opportunities for students to learn and further develop their skills. Our finding highlights the importance of giving helpful feedback on student performance, which facilitates students to generate diverse and creative ideas. While much work still needs to be done, academics may begin by reflecting on their enquiry and creative thinking processes and challenging their assumptions and preconceptions. This reflection can be followed by identifying their successes in idea generation and sharing these processes as exemplars for students to use, replicate or challenge. Creating group activities and challenges may also benefit teams more than individuals, as it allows brainstorming practices, which is considered one of the best ways to generate ideas (Coates, Cook, and Robinson Citation1997; McAdam and McClelland Citation2002).

Our study added value to the limited empirical research on creativity in the higher education context, particularly in business education. The final takeaways of this paper are that designing resources, learning activities, assessment practices, and feedback processes to provide business students with both learning experiences and opportunities to develop creative thinking skills are essential. Creative thinking should be included as one of the critical employability skills business graduates should have, along with other skills such as critical thinking, critical problem-solving, collaborative work and communication skills. Therefore, preparing academics to facilitate creativity skill development in classrooms should be prioritised in higher education.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Alencar, Eunice M. L. S. E., Danise Fleith, and Nielsen Pereira. 2016. “Creativity in Higher Education: Challenges and Facilitating Factors.” Trends in Psychology 25 (2): 553–61. https://doi.org/10.9788/TP2017.2-09.

- Amabile, T. M. 1983. “The Social Psychology of Creativity: A Componential Conceptualization.” Journal of Personality and Social Psychology 45 (2): 357–76. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-3514.45.2.357.

- Amabile, T. M. 1996. “Assessing the Work Environment for Creativity.” Academy of Management Journal 39 (5): 1154–84. https://doi.org/10.2307/256995.

- Association to Advance Collegiate Schools of Business. 2010. “Business Schools on an Innovation Mission.” AACSB. Accessed September 5, 2022. http://www.aacsb.edu/resources/innovation/business-schools-on-an-innovation-mission.pdf.

- Baer, John. 2016. Domain Specificity of Creativity. Academic Press. https://discovery.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=cb3e3641-fcbb-30e7-b30b-8c604a9b648f.

- Barbot, Baptiste, and Bernadette Heuser. 2017. “Creativity and Identity Formation in Adolescence: A Developmental Perspective.” In The Creative Self, edited by Maciej Karwowski, and James C. Kaufman, 87–98. Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-809790-8.00005-4.

- Clapham, Maria M. 1997. “Ideational Skills Training: A Key Element in Creativity Training Programs.” Creativity Research Journal 10 (1): 33. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj1001_4.

- Coates, Nigel F., Iain Cook, and Harry Robinson. 1997. “Idea Generation Techniques in an Industrial Market.” Journal of Marketing Practice: Applied Marketing Science 3 (2): 107–18. https://doi.org/10.1108/EUM0000000004336.

- Csikszentmihalyi, Mihaly. 2007. “Developing Creativity.” In Developing Creativity in Higher Education, edited by Norman Jackson, Martin Oliver, Malcolm Shaw, and James Wisdom, xviii–xx. London: Routledge.

- de Villiers, Scheepers, J. Margarietha, and L. Maree. 2015. “Fostering Team Creativity in Higher Education Settings.” e-Journal of Business Education and Scholarship of Teaching 9 (1): 70–86.

- Driver, Michaela. 2001. “Fostering Creativity in Business Education: Developing Creative Classroom Environments to Provide Students with Critical Workplace Competencies.” Journal of Education for Business 77 (1): 28. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832320109599667.

- Fekula, Michael J. 2011. “Managerial Creativity, Critical Thinking, and Emotional Intelligence: Convergence in Course Design.” Business Education Innovation Journal 3 (2): 92–102.

- Feldhusen, John F., and Ban Eng Goh. 1995. “Assessing and Accessing Creativity: An Integrative Review of Theory, Research, and Development.” Creativity Research Journal 8 (3): 231. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326934crj0803_3.

- Florida, Richard. 2004. “America’s Looming Creativity Crisis.” Harvard Business Review 82 (10). https://discovery.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=f0577190-6f48-31da-96bd-956816e739c2.

- Gajda, A., R. A. Beghetto, and M. Karwowski. 2017. “Exploring Creative Learning in the Classroom: A Multimethod Approach.” Thinking Skills and Creativity 24: 250–67. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tsc.2017.04.002.

- Glaveanu, Vlad Petre, Michael Hanchett Hanson, John Baer, Baptiste Barbot, Edward P. Clapp, Giovanni Emanuele Corazza, Beth Hennessey, et al. 2020. “Advancing Creativity Theory and Research: A Socio-Cultural Manifesto.” The Journal of Creative Behavior 54 (3): 741. https://doi.org/10.1002/jocb.395.

- Golen, Steven, Jack D. Eure, M. Agnes Titkemeyer, Celeste Powers, and Norman Boyer. 1983. “How to Teach Students to Improve Their Creativity in a Basic Business Communication Class.” Journal of Business Communication 20 (3): 47–57. https://doi.org/10.1177/002194368302000304.

- Hannon, S., H. McBride, and B. Burns. 2004. “Developing Creative and Critical Thinking Abilities in Business Graduates: The Value of Experiential Learning Techniques.” Industry and Higher Education 18 (2): 95–100. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000004323051868.

- Homayoun, Sogol, and Danah Henriksen. 2018. “Creativity in Business Education: A Review of Creative Self-Belief Theories and Arts-Based Methods.” Journal of Open Innovation: Technology, Market, and Complexity 4 (4), https://doi.org/10.3390/joitmc4040055.

- Jackson, Norman. 2006. “Imagining a Different World.” In Developing Creativity in Higher Education: An Imaginative Curriculum, edited by Norman Jackson, Martin Oliver, Malcolm Shaw, and James Wisdom, 1–9. Routledge.

- Kardoyo, Ahmad, Muhsin Nurkhi, and Hengky Pramusinto. 2020. “Problem-Based Learning Strategy: Its Impact on Students’ Critical and Creative Thinking Skills.” European Journal of Educational Research 9 (3): 1141–50. https://doi.org/10.12973/eu-jer.9.3.1141.

- Karpova, E., S. B. Marcketti, and J. Barker. 2011. “The Efficacy of Teaching Creativity: Assessment of Student Creative Thinking Before and After Exercises.” Clothing and Textiles Research Journal 29 (1): 52–66. https://doi.org/10.1177/0887302X11400065.

- Kaufman, James C., and Ronald A. Beghetto. 2009. “Beyond Big and Little: The Four C Model of Creativity.” Review of General Psychology 13 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0013688.

- Kerr, C., and C. Lloyd. 2008. “Pedagogical Learnings for Management Education: Developing Creativity and Innovation.” Journal of Management & Organization 14: 486–503. https://doi.org/10.5172/jmo.837.14.5.486.

- Li, Y., B. Li, and T. Lu. 2022. “Founders’ Creativity, Business Model Innovation, and Business Growth.” Frontiers in Psychology 13. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.892716.

- Lindberg, Erik, Håkan Bohman, Peter Hulten, and Timothy Wilson. 2017. “Enhancing Students’ Entrepreneurial Mindset: A Swedish Experience.” Education + Training 59 (7/8): 768–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-09-2016-0140.

- Long, Haiying, and Jonathan A. Plucker. 2015. “Assessing Creative Thinking: Practical Applications.” In The Routledge International Handbook of Research on Teaching Thinking, edited by Rupert Wegerif, Li Li, and James C. Kaufman, 315–29. London: Routledge.

- Matthews, Judy, and Cara Wrigley. 2017. “Design and Design Thinking in Business and Management Higher Education.” Journal of Learning Design 10 (1): 41–54. https://doi.org/10.5204/jld.v9i3.294.

- Mcadam, R., and J. Mcclelland. 2002. “Individual and Team-Based Idea Generation within Innovation Management: Organisational and Research Agendas.” European Journal of Innovation Management 5 (2): 86–97. https://doi.org/10.1108/14601060210428186.

- Milgram, Roberta M. 1990. “Creativity: An Idea Whose Time Has Come and Gone?” In Theories of Creativity, edited by Mark A. Runco, and Robert S. Albert, 215–33. Newbury Park, CA: Sage.

- Miller, Christine, Laura Cruz, and Jacob Kelley. 2021. “Outside the Box: Promoting Creative Problem-Solving from the Classroom to the Boardroom.” Journal of Effective Teaching in Higher Education 4 (1): 76–93. https://doi.org/10.36021/jethe.v4i1.204.

- Morris, Thomas Howard. 2022. “How Creativity Is Oppressed through Traditional Education.” On the Horizon: The International Journal of Learning Futures 30 (3): 133–40. https://doi.org/10.1108/OTH-09-2022-124.

- Morris, Thomas Howard, and Pascal D. König. 2020. “Self-Directed Experiential Learning to Meet Ever-Changing Entrepreneurship Demands.” Education + Training 63 (1): 23–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-09-2019-0209.

- OECD. 2016. “Education 2030: Key Competencies for the Future.” Accessed February 16, 2023. https://www.oecd.org/education/2030/E2030-CONCEPTUAL-FRAMEWORK-KEY-COMPETENCIES-FOR-2030.pdf.

- OECD. 2022. “PISA 2021 Creative Thinking Framework.” Accessed February 16, 2023. https://www.oecd.org/pisa/publications/PISA-2021-Creative-Thinking-Framework.pdf.

- Penaluna, A., and K. Penaluna. 2009. “Creativity in Business/Business in Creativity: Transdisciplinary Curricula as an Enabling Strategy in Enterprise Education.” Industry and Higher Education 23 (3): 209–19. https://doi.org/10.5367/000000009788640314.

- Plucker, Jonathan A., Ronald A. Beghetto, and Gayle T. Dow. 2004. “Why Isn’t Creativity More Important to Educational Psychologists? Potentials, Pitfalls, and Future Directions in Creativity Research.” Educational Psychologist 39 (2): 83–96. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3902_1.

- Ramalingam, D., Prue Anderson, Daniel Duckworth, Claire Scoular, and Jonathan Heard. 2020. “Creative Thinking: Definition and Structure.” Australian Council for Educational Research. Accessed January 24, 2023. https://research.acer.edu.au/ar_misc/43.

- Rhodes, Mel. 1961. “An Analysis of Creativity.” The Phi Delta Kappan 42 (7): 305–310. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20342603.

- Riordan, D. A., M. C. Sullivan, and D. Fink. 2003. “Promoting Creativity in International Business Education.” Journal of Teaching in International Business 15 (1): 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1300/J066v15n01_03.

- Sawyer, Keith. 2012. Explaining Creativity: The Science of Human Innovation. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Scaltsas, Theodore. 2016. “A Cognitive Trick for Solving Problems Creatively.” Harvard Business Review Digital Articles, May, 2–5. https://discovery.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=58569da8-e824-3150-a3b4-950cccc0d1c9.

- Schmidt-Wilk, J. 2011. “Fostering Management Students’ Creativity.” Journal of Management Education 35 (6): 775–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562911427126.

- Shalley, Christina E., Lucy L. Gilson, and Terry C. Blum. 2009. “Interactive Effects of Growth Need Strength, Work Context, and Job Complexity on Self-Reported Creative Performance.” Academy of Management Journal 52 (3): 489–505. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2009.41330806.

- Smith-Bingham, R. 2006. “Public Policy, Innovation and the Need for Creativity.” In Developing Creativity in Higher Education an Imaginative Curriculum, edited by N. Jackson, M. Oliver, M. Shaw, and J. Wisdom, 10–18. Routledge.

- Sosa, Ricardo, and David Kayrouz. 2020. “Creativity in Graduate Business Education: Constitutive Dimensions and Connections.” Innovations in Education and Teaching International 57 (4): 484–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/14703297.2019.1628799.

- Sternberg, Robert, and Todd Lubart. 1999. “The Concept of Creativity: Prospects and Paradigms.” In Handbook of Creativity, edited by Robert J. Sternberg, 3–15. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Ungaretti, Toni, Peter Chomowicz, Bernard J. Canniffe, Blair Johnson, Edward Weiss, Kaitlin Dunn, and Claire Cropper. 2009. “Business + Design: Exploring a Competitive Edge for Business Thinking.” SAM Advanced Management Journal (07497075) 74 (3): 4–43. https://discovery.ebsco.com/linkprocessor/plink?id=f2ad64ea-8ec7-3ca1-99d7-a7b3d3568ede.

- Verzat, Caroline, Noreen O’Shea, and Maxime Jore. 2017. “Teaching Proactivity in the Entrepreneurial Classroom.” Entrepreneurship & Regional Development 29 (9/10): 975–1013. https://doi.org/10.1080/08985626.2017.1376515.

- Vincent-Lancrin, Stéphan, Carlos González-Sancho, Mathias Bouckaert, Federico de Luca, Meritxell Fernández-Barrerra, Gwénaël Jacotin, Joaquin Urgel, and Quentin Vidal. 2019. Fostering Students’ Creativity and Critical Thinking: What It Means in School. Paris: OCDE Publishing.

- Weick, C. W. 2003. “Out of Context: Using Metaphor to Encourage Creative Thinking in Strategic Management Courses.” Journal of Management Education 27 (3): 323–43. https://doi.org/10.1177/1052562903027003004.

- Wongpinunwatana, Nitaya, Kunlaya Jantadej, and Jamnong Jantachoto. 2017. “Enhancing Creative Thinking in Business Research Classes: Classroom Action Research.” Journal of Higher Education Theory & Practice 17 (8): 43–57.

- World Economic Forum. 2020. “These Are the Top 10 Job Skills of Tomorrow.” Accessed April 7, 2023. https://www.weforum.org/agenda/2020/10/top-10-work-skills-of-tomorrow-how-long-it-takes-to-learnthem/.

- Zacher, H., and E. Johnson. 2015. “Leadership and Creativity in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 40 (7): 1210–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.881340.

- Zhang, X., Y. Zhang, Y. Sun, M. Lytras, P. Ordonez de Pablos, and W. He. 2018. “Exploring the Effect of Transformational Leadership on Individual Creativity in E-Learning: A Perspective of Social Exchange Theory.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (11): 1964–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1296824.

- Zhao, J. J., and S. Y. Zhao. 2022. “Creativity and Innovation Programs Offered by AACSB-Accredited U.S. Colleges of Business: A Web Mining Study.” Journal of Education for Business 97 (5): 285–94. https://doi.org/10.1080/08832323.2021.1934373.