ABSTRACT

Higher education’s focus is shifting to include societal impact alongside academic excellence. While community-engaged scholarship has a long history, many initiatives focus on individual researchers or institutional practices, without accounting for disciplinary and geopolitical contexts. The Community Engagement for Impact (CEFI) Framework and the Contextual Model of Community Engagement (CMCE) are based on findings of an in-depth, qualitative study of researchers’ strategies for community engagement. Results point to complex relationships between researchers, universities, and disciplines, shaped by government policy, research trends, community imperatives, and other factors. While participants fostered community relationships supporting social change, they did not receive appropriate training, support, or recognition. CEFI guides individuals and institutions to identify barriers and facilitators for engagement, across disciplines, for work involving industry organisations, community groups, governments, and other partners. When used alongside CMCE’s approach to local, national, and global factors, researchers, universities, and disciplines can better support pathways to societal impact.

Introduction

Since Boyer’s (Citation1990; Citation1996) early work to embed community engagement (CE) across academic work roles, universities have continued to call for more external engagement (e.g. Barnett Citation2015; Gunter Citation2012; Wendling Citation2020). Such engagement raises fundamental questions about the role of universities in contemporary society; if research is to generate knowledge for the public good, researchers’ roles should reflect that mission. Although most universities include CE goals in vision statements and strategies, little is known about the effectiveness of CE practices or how best to support academics in this work. There remains significant tension between institutional desire for academics to engage and formalised reward systems that prioritise grant and publication metrics. While many scholars do engage with communities, they are not always rewarded for such work (see, Macfarlane Citation2007; Wenger, Hawkins, and Seifer Citation2012). This study examines this tension, in-depth, by reporting empirical results of a qualitative study with researchers in humanities and social sciences disciplines who were engaging with communities in their academic work. The findings point to significant complications in the implementation of institutional and disciplinary support for CE work aligned to researchers’ personal values and work-related imperatives.

Studies of CE practices in higher education often use quantitative measures to gather data, focusing primarily on science disciplines and exploring institutional perspectives; little attention is paid to researchers’ own experiences (e.g. Randall Citation2010; Winter, Wiseman, and Muirhead Citation2006). This paper addresses significant gaps in the current literature by presenting the results of a qualitative study of humanities and social sciences researchers’ experience of CE. The study addresses the following research questions: (1) How do the participants’ experiences instantiate the role of the university in modern society, which positions societal impact alongside traditional measures (e.g. publishing; grants) of academic success? (2) What systemic barriers exist that may prevent academics from conducting CE activities? (3) What approaches do community-engaged academics use to carry out CE, successfully?, and (4) What changes to higher education and/or disciplinary policies and practices will better support academics’ CE activities for social impact? The analysis provides an evidence-based framework and contextual model designed to support researchers, universities, and disciplines to balance academic expectations alongside sectoral trends in higher education.

In doing so, the framework and contextual model advance our theoretical understandings of academics’ experiences of CE by providing disciplinary, institutional, and individual lenses for analysis that enable us to better understand the complexities shaping societal impact within universities. This research builds on previous theoretical work within the scholarship of engagement, providing new, theoretical insights, alongside the application of a practical lens to complement these theoretical underpinnings. The paper makes a significant contribution to the literature of CE that, to date, has focused primarily on institutional understandings, in isolation from other contextual factors. The paper provides a holistic approach to understanding academics’ experiences (see Polkinghorne and Given Citation2021), drawing on personal, institutional, and disciplinary contexts that are inextricably woven into CE practices.

Literature review

This study draws on a significant body of interdisciplinary literature, worldwide, examining societal impact policies and practices, researchers’ individual experiences in the academy, and approaches to research training in higher education. The review outlines the evolution in thinking about CE practices within universities, beginning with historical explorations of the role of the university in society, and moving towards evidence-based policies and practices that influence teaching, research, and service roles. The review is organised in three sections, reflecting the foci that have shaped these explorations since Boyer’s (Citation1990; Citation1996) landmark work.

First, we present the ‘institutional context’, as most studies focus on universities’ approaches to embedding CE as part of academic practice. Second, we examine the implications for research training, including disciplinary norms and expectations for academic work. Third, we explore recent trends toward demonstrating and rewarding research impact beyond academe, which benefits society. These three areas provide relevant background to better understand how institutions and governments have positioned academic work, over time, while also highlighting the lack of empirical evidence that positions researchers, themselves, within the broader institutional and disciplinary contexts that shape how they engage within their communities.

Institutional context

A significant amount of literature demonstrates that CE is aligned with many universities’ missions, and with teaching and research practices embedded in the community. The development of knowledge mobilisation units (e.g. Phipps, Gaetz, and Wedlock Citation2014) and the increasing focus on community-based and participatory research (e.g. Burgess Citation2014; Du and Chu Citation2022) demonstrate CE’s influence over time. However, much of the existing research is focused on institutional rather than academics’ experiences; this is a significant gap given that the bulk of engagement work is done by academics themselves. For example, several books focus on the intersection of universities and CE by addressing management and implementation from a system perspective, rather than considering individual academics’ experiences (see, Benneworth Citation2013; Dostilio Citation2017; Watson Citation2007). Also, many institutions embrace rhetoric without embedding CE practices in reward and support structures, which materially (and often, adversely) affect academics’ available time and support for engagement work. Universities can provide tangible support for CE by rewarding activities in promotion reviews, providing incentives, and acknowledging successes (see, Schimanski and Alperin Citation2018; Smith, Else, and Crookes Citation2014; Youn and Price Citation2009).

Unfortunately, even when CE rewards are feasible, research shows these are adopted inconsistently, if at all (Barreno et al. Citation2013; Carman Citation2013). Watermeyer (Citation2015) found a lack of ‘institutional interest, acknowledgement, incentivization and reward’ (334) for CE. Alperin et al.’s (Citation2019) study of annual review, promotion, and tenure documents found CE activities labelled ‘service’ while privileging traditional ‘research’ activities (i.e. publications and grants). Similarly, Mtawa, Fongwa, and Wangenge-Ouma (Citation2016) found CE policy was often related to outreach rather than research activities, and rarely was accompanied by tangible support, such as funding. Despite positive CE rhetoric, academics often receive little support for publishing in professional venues or translating research for the public (e.g. Bentley and Kyvik Citation2011; Wilkinson and Weitkamp Citation2013). As Anderson (Citation2014) notes, ‘in the place of authentic engagement, [institutions] continue to advance academic interests and sensibilities while extracting rather than adding value to communities’ (143).

As the results of this study demonstrate (as discussed in the Findings and Discussion section), the inability of institutions to reflect and support the needs of academics’ engaged in impact work with their communities, and to provide incentives and recognition for that work, will continue to hold academics back from reaching their full potential. The institutional context remains a critical driver of academics’ behaviours and, therefore, of the success of CE practices. Additional research is needed to fully understand the depth and breadth of institutional reach, as a driver of academics’ CE practices.

Researcher preparedness & disciplinary orientation

Community engagement development for researchers is not always prioritised within PhD programmes or at early career stages; and, job relocation can limit access to community partners, which can make it difficult for academics to translate their work for societal impact (Willson and Given Citation2020). Research demonstrates that academics are often ill-prepared to track and document engagement work. For example, Given, Winkler, and Willson (Citation2014) found ‘tracking and analysing [engagement] data falls outside of researchers’ everyday practices’ and noted the lack of ‘time, funding and technical supports needed to gather these data’. Other studies note the need for specialist training and skills for media engagement. Such training improves researchers’ confidence and ability to engage (Chapman et al. Citation2014; Orr Citation2010), but universities often do not provide it (Moore and Morton Citation2017). Additionally, there is a disconnect between the desire of organisations to see academics engage in activities such as public dissemination and promotion expectations. For example, Jensen et al. (Citation2008) found public dissemination activities were generally insignificant for promotion. Thus, institutional decisions about what to incentivize and reward not only materially disadvantage academics who choose to engage in CE practices, they also limit institutional offerings for professional development, PhD training, and other academic support opportunities for CE work. In turn, the lack of development and capacity-building resources may reduce CE uptake, overall, due to lack of awareness and preparedness for academics to engage effectively beyond academe.

Although CE is gaining prominence, some disciplines are less inclined to engage than others (see, Chan and Farrington Citation2018; Whiteford and Strom Citation2013). Community-based research designs are resource-intensive and often perceived (incorrectly) as lacking rigour, which adversely affects uptake (Savan et al. Citation2009). There are many studies that investigate the factors that motivate engagement activities, but the vast majority focus on STEM (science, technology, engineering, and medical) disciplines (e.g. Besley, Dudo, and Yuan Citation2018; Dudo Citation2012; Entradas and Bauer Citation2017; Ho, Looi, and Goh Citation2020; Neresini and Bucchi Citation2011; Pearson Citation2001; Poliakoff and Webb Citation2007; Trench and Miller Citation2012). In STEM, many accredited programmes integrate coursework and industry placements, providing researchers with ready access to partners and funding (e.g. Australian Postgraduate Research Intern programme, https://aprintern.org.au/).

Glass et al.’s (Citation2011) survey of 173 promotion and tenure documents, found a vast range of public engagement experiences and recommended that ‘institutions striving to support community engagement should not simply take a ‘one size fits all’ approach to faculty development’ (26). In many SSH (social sciences and humanities) disciplines, researchers rely on colleagues and informal strategies to model CE best practices (Purcell, Pearl, and Van Schyndel Citation2021). Unfortunately, little is known about SSH researchers’ training and support needs, or the facilitators and barriers to CE. This study addresses this significant gap by giving voice to SSH researchers’ lived experiences of engaging with the community while working within institutional and disciplinary contexts that may – or may not – support CE work. As discussed in the Findings and Discussion section, a lack of training opportunities during the PhD and at early career stages requires many academics to gain skills, informally, and to balance professional career development with personal value imperatives.

Societal impact imperative

Significant shifts in global research policy and practice mean that university researchers must demonstrate the impact of their work in society (see Langfeldt and Scordato Citation2015; Reale et al. Citation2017). This shift aligns with the introduction of government schemes to assess universities’ societal contributions (e.g. United Kingdom’s Research Excellence Framework; Australia’s Engagement and Impact Assessment). These schemes change the focus for accountability and funding from measures documenting academic impact (e.g. citations), exclusively, to those documenting economic, social, environmental, health, and other research benefits beyond academe. Yet, if local conditions prevent or limit academics’ ability to engage with community, the generation of impact outcomes is inevitably affected. More empirical research is needed to fully understand how academics navigate complex research systems to engage productively in CE for societal impact.

There is an emerging body of scholarship on how to approach CE work for societal benefit. For example, Aiello et al. (Citation2021) found social impact in SSH is increased when there’s a focus on impact from the start of a project, when stakeholders and end-users are meaningfully engaged, when dissemination involves beneficiaries and allows debate, and when impact is tracked throughout the project. Yet, while bibliometric studies map the development and quality of academic impact (e.g. Althouse et al. Citation2009), societal impact measures are underdeveloped, requiring significant investment (Bornmann Citation2013; Given, Kelly, and Willson Citation2015; Watermeyer Citation2014). Pedersen, Grønvad, and Hvidtfeldt (Citation2020) argue that more sophisticated approaches are needed to account for the societal value of research per discipline, especially in the arts, humanities and social sciences. They argue, ‘while the conceptual interest in research impact pervades the academic and policy literature, it is surprising that no more empirical studies (especially among academic contributions) are found’ (16). The results presented in this paper address this call for more empirical research to inform institutional, disciplinary, and individual approaches to embedding societal impact within academic work.

Overall, the literature that maps higher education’s increasing move to embrace a societal impact imperative, globally, requires new approaches to partnering and collaboration, to methodologies inclusive of stakeholder voice, and to processes that embed, track, and evaluate impact throughout and beyond research projects. To do so, researchers can apply CE knowledge and processes to their research approaches (e.g. co-design, co-production, translation); however, the disciplinary and institutional contexts that shape how academics operate must also be addressed for uptake to occur. This study explores academics’ experiences and perceptions across all three levels, to outline implications for future CE work.

Research design

This project used qualitative, constructivist grounded theory (Charmaz Citation2014) to examine SSH researchers’ perspectives on CE benefits and challenges, including institutional and disciplinary support. Semi-structured interviews with twenty-six participants (twenty academics and six administrators/professionals in support units) were conducted at twenty-four research-intensive public universities in Canada and Australia. provides an overview of academic participants’ ages, stages of career, and disciplinary focus. provides details on the key informants who participated in the study.

Table 1. Academic participants.

Table 2. Key informant participants.

Participants were recruited using maximum variation, purposive sampling, through social media, personal networks, and snowball sampling. Interviews lasted ∼60 min and were transcribed verbatim. Participants provided consent prior to data collection and were assigned pseudonyms. The interviews explored individuals’ work contexts, support needs, and their disciplinary and personal views on CE.

Findings and discussion

The following sections outline participants’ CE activities, the enabling factors supporting engagement, and institutional and disciplinary considerations. The results informed the development of a Community Engagement for Impact (CEFI) Framework and a Contextual Model of Community Engagement, which outline key issues researchers, institutions, and disciplines must address, within the context of geo-political factors influencing CE practices.

How do academics engage with the community?

Participants described various CE practices, including: lobbying government, advocacy, crowdfunding, digital storytelling, instruction, participatory action research, public presentations, and media interviews, among others. Several factors influenced how and when researchers engaged externally, including: career stage, disciplinary norms, university expectations, and personal views on societal impact. Just as disciplines reflect diverse theoretical, methodological, and pedagogical approaches, disciplinary approaches to CE are equally varied.

Although such activities may be considered ways to engage, participants did not define the concept of engagement consistently. For some, CE was integrated across all academic roles; for others, CE was limited to one-way sharing (e.g. open access publishing) or advocating for change. All participants believed engagement work, whatever its form, was important and useful. Their engagement was motivated by passion for the community and desire to inform social change.

Participants’ CE experiences reflected three main styles (see ). Doing something ‘with’ a community includes action research, where community participation is integrated throughout the research process. Doing something ‘for’ the community includes completing a commissioned study or being hired to conduct a training session. Doing something ‘to’ a community includes information-sharing, with little direct contact with community members. How researchers position themselves in relation to the community affects the design and outcomes of CE work.

Table 3. Styles of participants’ engagement with community.

Enabling factors for individuals to engage

Participants reflected on their CE journeys and factors they could control. The following sections discuss participants’ drive to engage, their passion for CE, and their varied approaches to fostering community relationships.

Academics’ innate drive to engage with community

While participants expressed different reasons for working with specific communities, they did not pursue CE simply for career advancement. Rather, they chose to situate their research in community to foster social change; CE was a core principle shaping their work and contributing to what it means to be an academic. Leon (Associate Professor, Information Science) believed those pursuing CE were internally motivated, stating ‘I think it’s all innate. If you don’t care about making the community where you live and work better, you’re not going to do research in the community. So, it’s just who you are’. Dale (Senior Lecturer, English) said, ‘my whole career is about impacting on the community … I don’t really have a great interest in pure research for its own sake. I have an interest in the application that it can make’. Sarah’s (Senior Lecturer, Education) research was designed to inform policy and organisational change; she conducted ‘commissioned research with organisations, practitioner research, or embedded research in organisations [to] make a difference’. The desire to foster positive change motivated all participants.

Participants also discussed what they gained from CE, personally. Camille (Professor, Education) considered CE a refreshing tonic from other responsibilities. She explained,

I can expend a huge amount of energy on some of these engagements, if they feed me intellectually … holistically. Then I can keep doing them … these things make me feel alive … Some activities that happen within the academy [they] take the oxygen out of the room [but when] I connect with community … [it] brings oxygen into the room.

Established/ing connections and building relationships with community

Participants described multiple, varied pathways into communities: leveraging relationships from previous projects; connecting through formal university or external contacts; mobilising personal networks; or, serendipitous meetings with future partners. As Camille (Professor, Education) described, ‘almost all of my research projects have been some form of community-engaged inquiry with community; sometimes I've initiated the partnerships, other times I've been invited by the community to do something’. Epistemologically, many CE approaches align to practice-based methodologies, such as participatory action research (e.g. Zuber-Skerritt Citation2015), which rely on community-based relationships.

Participants stressed that engagement must be done on the community’s terms. For Lillian (Lecturer, Media and Communications), this involves ‘finding out what it is that that community group wants to do, and acting on that, rather than [researchers saying] ‘we've got this programme for you, that's going to benefit you’. For her, CE involves saying ‘okay, what's your problem? How can we solve it?’ Leon made connections while away from his academic job, while serving as a faculty-member-in-residence at a public library. With the chief librarian’s support Leon set up ‘a workshop, and we had people come in and had little tables set up, to … elicit different research ideas;’ this work could not be done without the trust gained by being situated in the library and working alongside practitioners and community members. All participants highlighted the reciprocal, mutually beneficial nature of researchers’ relationships with communities. Sarah (Senior Lecturer, Education) found working directly with people and organisations increased the likelihood her research would ‘inform policy, or inform organisations [to] make a difference’. This is consistent with other research showing partner-sponsored consultancies often result in knowledge transfer (Olmos-Peñuela, Castro-Martínez, and D’Este Citation2014).

Working with intermediaries also facilitates researchers’ connections with target populations. Kelli (Assistant Professor, Political Studies) found non-government and non-profit organisations helped 'get me into communities’. Traci (Senior Lecturer, Sociology) discussed leveraging relationships ‘in the welfare-to-work space [where] I had good contacts with a lot of the social service agencies [to do] a lot of recruitment’. Ahmed et al. (Citation2016) explain ‘community organisations often have long-standing relationships built on trust with target populations’ (58), providing entry-points for researchers. University colleagues fostered participants’ links to community groups, with senior researchers facilitating connections for junior colleagues or those without direct networks. For Emily (Senior Lecturer, Information Science), a student served as a critical ‘bridge’ to an Indigenous community:

I have a masters student [who] has over ten years working experience with [an Indigenous] community … So, we collaborated … She’s my PhD student now, and she built up the trust between me and them, so … she's a great bridge.

Career strategy

Across career stages, participants highlighted the importance of approaching CE strategically, for professional growth. As many academics work 50–60-h weeks (Flaherty Citation2014; Miller Citation2019), CE may be burdensome; researchers must make difficult choices to balance teaching, research, and service. Yet, participants believed CE was in conflict with institutional priorities for publishing and grants. As Annabelle (Lecturer, Development Studies) stated, ‘[CE is] not going to get you promotion. It’s still publish or perish’. Meredith (Professor, Business and Economics) echoed this concern:

In many institutions … if you’re doing [CE] instead of publishing, then you get stopped at tenure. Hav[ing] a strong publication record is not only required for promotions, but granting agencies also look closely at an academic’s publication record.

[Universities] want all this other stuff [but] in promotion guidelines, none of that stuff counts … so the things that I actually get evaluated on, or that are going to keep me employable, are the things I’m going to focus on. So, having glossy things and websites and Conversation pieces and media spots. Nah. That’s not actually what I see most of my job being.

It’s about … making strategic choices; and some of my principles I may have to drop for a little while, until I get through probation and tenure [in] a couple years’ time, so that I can focus on meeting institutional targets.

it’s an issue in academia as a whole [as] my merit increases are directly tied to just the number of things that I produce … grants, number of publications, type of publication … Where do we make a space for these other types of activities that might have an impact but are not easily … traced by a certain type of metric? I think the university still has a lot of evolution to do in this regard.

Participants’ views align with literature examining neoliberalism’s influence on higher education, where the ‘culture of publish-or-perish continues to drive academic activities’ (Doyle Citation2018, 1372). Harré et al. (Citation2017) explain academics must be agile and respond to various challenges, including ‘the invisible or visible agendas of the university, individuals, or both’ (8). Successful academics must balance competing obligations and interests (Ball Citation2012; Bourke Citation2015). When engagement policies are in place, researchers can demonstrate alignment to institutional values and prioritise CE.

Institutional acknowledgement of CE activities

Participants’ experiences demonstrate that tangible CE support varies considerably, even when university rhetoric is strong. Participants believed they were not adequately rewarded or supported for CE and turned to institutional policies to justify this work.

Policy as leverage for CE

University policies shape researchers’ workloads and the priorities of support units (e.g. academic libraries; research offices). Yet, participants found institutional policies difficult to locate or applied inconsistently across organisational levels. Reward schemes can fuel competition and discourage collaboration (Turner et al. Citation2015), and participants noted promotion and support models reinforced individualistic achievements. Traci (Senior Lecturer, Sociology) was pleased to discover her school permitted allocation of 10% research time to CE, but concerned this was not formalised:

Unless you ask for that, it’s not stated. So, nobody actually knows about that and there is no definition of what that [allocation] is. But it’s for things like meeting with community partners, disseminating things … [But] this is just our school’s informal, loosely assembled policy.

Gayle (Associate Professor, Planning) consulted the faculty research plan and university strategy when compiling her annual report. However, she used these to demonstrate institutional alignment for completed work rather than prospective planning: ‘I wouldn’t say I look at [the strategy] and see how it shapes the work I do. I do the work that I do, and then I go back and go “how do I need … to please the [administration]”.’ Sarah (Senior Lecturer, Education) did the same, noting ‘I have a mind to what is needed, in order to get promotion and to, you know, be seen as fulfilling [the university’s] requirement … but I don’t let that drive my agenda’. For Kristine (Associate Professor, Education), the arrival of a new university president with a strategic direction centred on CE, was positive:

people can point to that [strategy] and say ‘that’s the direction we’re going in’ and use it as a rationale for decision making … [The university] can then tie budget priorities to that, and decision making to that, and use that as sort of a lens that everybody can relate to.

We wanted [our university] to be the first one to get [CE] in the promotion and tenure process and do it right … So we had roundtable meetings, and I know some of the deans came in and said ‘well, it’s a really interesting piece, let’s see if we can do it within our faculty collective agreement;’ others came in and said ‘no we can’t [make it work]’

Support needed from senior institutional leaders

Participants highlighted supports received from local (e.g. faculty; department) and university-level administrators as important CE facilitators. Participants viewed leadership as vital to expanding CE activities, which is consistent with previous research (e.g. Bernardo, Butcher, and Howard Citation2014; Goodman Citation2014; Prysor and Henley Citation2017; Welch and Plaxton-Moore Citation2017). Camille (Professor, Education) reflected on the need for this support:

You have to have some champions, and they have to be at key senior levels. So, our [Vice-President] Research actually supported … two town hall meetings – day-long events around community-based research. And that was quite a symbolic [decision and a] taskforce grew out of that.

We have a new deputy pro-vice-chancellor for research and innovation, and she promotes this community-based research very much. I think it’s a good support.

She was really great, she said, ‘let’s have a look at your workload’ and I was way overloaded; and she said, ‘there must be money for you to get tutoring done’.

Few tangible supports for CE

Overall, participants provided few examples of tangible support received from their institutions; they struggled to identify support units (e.g. academic libraries, research offices) or policies that facilitated CE (e.g. time release). Lydia (Associate Professor, Education) highlighted this gap, noting she needed ‘more support [including] recognition or support for that kind of work that happens ahead of time’, before a project begins. All participants mentioned the significant preparatory work needed for CE, including maintaining relationships. As Kristine (Associate Professor, Education) noted, universities ‘don't recognise that [it] took ten years of relationship-building in order for me to get to a point where I can pick up the phone and call somebody in the [government] ministry’.

Participants talked at length about university communications offices, as CE was often facilitated through press releases and events. Overall, they saw these units as barriers, not enablers, to external engagement. As Gloria (Professor, Media and Communications) explained, communications offices are ‘focused on undergraduate recruitment, so everyone else struggles to get a voice or a vision’. Dale (Senior Lecturer, English) struggled with promotion of a guest speaker, noting his media ‘office was just inserting their authority’ through required approvals (resulting in production delays), without helping to prepare materials. Participants also reflected on the availability and quality of media training, with Sarah (Senior Lecturer, Education) frustrated that none was available. Annabelle (Lecturer, Development Studies) and Irvin (Professor, Philosophy) described numerous workshops on offer, but with varying levels of quality.

Participants did not mention any support units engaged in CE facilitation, providing few examples of university strategies to facilitate community connections. Leon’s (Associate Professor, Information Science) university arranged for academics to meet community members through a community-of-practice group. However, he believed this was unique, noting such support requires ‘a mind shift for universities to recognise the value of community-engaged research, offering some micro-funding, offering opportunities to meet members of the community or associations who can get you there’. At Leon’s university, strategic funds were available to encourage researchers to ‘leave the campus walls and go out into the community and do different projects’.

Dale (Senior Lecturer, English) remarked on the usefulness of the academic library’s physical spaces for CE, echoing Given et al.’s (Citation2015) discussion of the potential for university libraries to support external engagement. However, Dale found the library’s policies were misaligned to community needs. As he explained, the library ‘decided they needed to shut at six … Now, for people who are office workers, that's not going to work’. Floyd (Manager, Knowledge Mobilisation) described a successful brokering model that connected community groups with academics. When the programme launched, they were inundated with non-profit organisations wanting to ‘connect with academic research and researchers [without having] to pay, and [that could] be really geared around [their] needs’. As Floyd explained, ‘the relationship-building piece at the front-end strengthens the research’, particularly by ‘bringing people together around the table who otherwise wouldn’t have gotten together’.

Disciplinary imperatives shape academics’ ability to engage

Participants’ experiences of CE were also connected to disciplinary traditions, demonstrating differences in expectations for CE. As an English scholar, Nathaniel (Assistant Professor) explained his discipline did not expect him to engage with the community; but, with the support of his line manager, Nathaniel received workload recognition for this work. Although this was a positive outcome, locally, he also understood that time spent on CE (rather than traditional outputs) could adversely affect the way his tenure application would be viewed by disciplinary colleagues. He explained,

My chair would recognise [CE] in my performance review. Where it’s probably going to be seen as a very insignificant blip is in my tenure file. When my tenure file gets evaluated by external examiners who are going to be focused on, like ‘okay what grants did he win? is his book out? [and] how many articles has he published?’

Film studies … has only itself to blame for its decline [in universities as] the strategies that were adopted to get into universities were … designed precisely to do the opposite of [CE and] to separate them from the concerns … of people who are outside of [the field].

Community engagement for impact (CEFI) framework

Societal impact is predicated on the development of strong pathways of engagement between researchers and communities. This study demonstrates alignment is needed between a researcher’s personal desire and capacity to engage, their university’s support, and disciplinary expectations. In professional disciplines (e.g. engineering, nursing, education), academics often engage with practitioners and accreditation standards may incentivise CE. However, in disciplines lacking immediate or readily apparent sites for engagement, researchers may struggle to build community connections. Disciplinary and university norms may reinforce traditional expectations for grants and publications, without incentivising societal impact. As CE is a pathway to impact, fostering alignment between researcher, university, and disciplinary contexts is critical for social change.

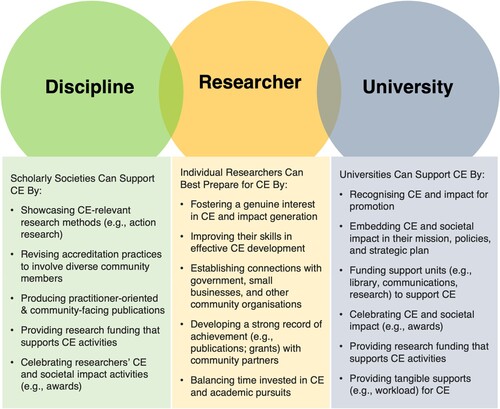

The Community Engagement for Impact (CEFI) Framework () enables interrogation of researcher readiness for engagement, while detailing university and disciplinary facilitators and barriers. By mapping individuals’ CE capacity relative to university and disciplinary expectations and rewards, CEFI supports all groups to better understand how, when, and where researchers can engage. CEFI outlines specific contextual aspects related to discipline, individuals, and universities, including methods, initiatives, and policies that can influence CE practices. The framework provides examples of the types of concrete initiatives that disciplinary groups, researchers, and university administrators can pursue to help researchers successfully engage in CE. For example, an early-career researcher in a discipline that values action research (discipline dimension), who collaborates with a colleague with community connections (researcher dimension), and who is given release time from other duties (university dimension), has more capacity for CE. By understanding how the discipline can foster CE, who an early-career researcher might approach for CE support, and how a university can reward CE, individuals working in all three dimensions can better enable CE activities.

Rather than creating a one-size-fits-all CE reward structure, universities must create incentives and rewards aligned to disciplinary contexts. A practice-based discipline with ready access to partners may more easily enable researchers to engage, while those in non-practice disciplines may require longer lead times and more institutional support. Administrators can use CEFI to assess internal aspects (e.g. promotion processes; funding schemes), while disciplinary associations can use CEFI to examine opportunities to foster engagement (e.g. conferences open to community-based delegates).

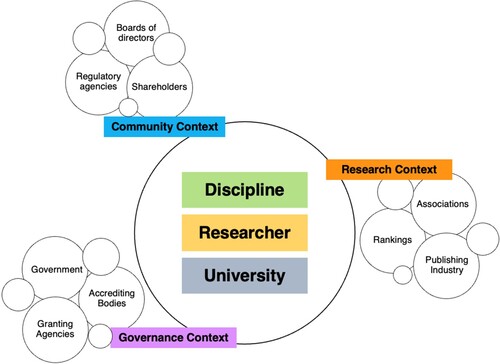

Addressing the geopolitical gap – A contextual model of community engagement

This research also identified notable gaps in participants’ awareness of sectoral trends affecting CE readiness. The Contextual Model of Community Engagement (CMCE) Framework () supports researchers, universities, and disciplines to articulate and attend to geopolitical issues affecting higher education with implications for CE. The following sections detail key geopolitical drivers that must be considered.

Community context

Participants worked with non-profit organisations, governments, refugee groups, libraries, and schools, among other community groups. Each community is unique, requiring bespoke activities and points of engagement; CE participation is affected by an organisation’s mission, staffing, funding priorities, and other factors. Where some organisations have large, well-compensated boards of directors, others rely on small groups of volunteers. The drivers influencing a community’s decision to engage, and to adopt research innovations, sit outside the researcher’s (or the university’s) locus of control.

Although CE outcomes bring value to communities, CE work can burden organisations (Clark Citation2008). Some groups face (what participant Lillian called) ‘research fatigue’ when approached multiple times. Research outcomes may also identify organisational challenges that partners are reluctant to expose or cannot address due to limited resources. Researchers must be aware of these complex issues and supported by their universities to navigate them. Considerations include:

Do the proposed CE activities align with the community’s goals?

What are the community access points and approval processes for CE?

Are community resources available to support proposed CE activities?

What are community expectations of CE outcomes (e.g. data ownership)?

Does the community have capacity to enact change arising from CE?

Governance context

State, national, and local governments, professional accrediting bodies, and other organisations shape the research enterprise, including CE. Research ethics and integrity guidelines vary across countries, requiring international teams to navigate differing processes. Funding agencies have unique reporting and financial acquittal requirements. Government election cycles can alter funding scheme priorities, with implications for CE partnerships.

Researchers must understand and manage such governance matters. For example, when conducting international collaborations, or working with community members in vulnerable situations, researchers may face additional ethics oversight, financial constraints, and privacy requirements. While universities may provide some guidance, they may be unable to advise researchers on specific governance matters beyond their local control and experience. Researchers, universities, and partners must be aware of relevant governance matters and plan for contingencies. Considerations include:

What external governance requirements may influence CE (e.g. accreditation)?

Do planned CE activities fall within grant funding guidelines?

What government incentives (e.g. tax credits) can support CE?

What local, national, and international ethics guidelines apply for CE?

Do partners have resources to develop contracts (e.g. multi-institutional agreements)?

Research context

Researchers operate globally, within established extranational disciplinary practices; they must navigate publishing systems, ranking schemes, disciplinary associations, and other cross-sectoral elements. Researchers collaborate with international colleagues, relocate for new positions, supervise cross-institutional PhD students, and engage with communities, globally. The outcomes of their work affect academic and professional communities worldwide, for which they are assessed, recognised, and rewarded throughout their careers.

Yet, academe’s global nature often conflicts with local practices. For example, multi-institutional, international agreements may take longer to negotiate due to legal differences. Publisher agreements reflect the organisation’s home country, while editors and authors live elsewhere. From the mundane (e.g. spelling conventions) to the significant (e.g. taxation laws), CE practices must account for global and local imperatives. Considerations include:

What venues will satisfy both scholarly and community-based dissemination needs?

Do disciplinary associations support CE (e.g. can community delegates attend conferences)?

How can equitable CE practices be assured across borders (e.g. differing pay scales)?

Will global initiatives towards open data sharing affect CE activities?

How can communities contribute meaningfully to projects without undue burdens?

Implications for future theoretical investigations

While Boyer's (Citation1990; Citation1996) writing on CE was influential in creating a theoretical space to explore the scholarship of engagement, a significant amount of work continues to focus, primarily, on providing commentary and theoretical exploration to shape future policy and practice directions (e.g. Crabill & Butin Citation2014; Dempsey Citation2010; Fitzgerald et al. Citation2016). While the number of empirical studies has grown, much of this work focuses on quantitative approaches (e.g. Alperin et al. Citation2019; Neresini and Bucchi Citation2011), which do not fully delineate what it means to engage. This study demonstrates the significance of incorporating both a qualitative lens, to highlight the complexity of lived experiences of community-engaged academics, and a holistic approach that speaks to the various disciplinary, institutional, and broader social imperatives that influence academics’ CE practices. Future research can contribute to further bridging this gap, by extending the range of qualitative methods used to examine academics’ experiences, and by reaching beyond the humanities and social sciences. By incorporating a broader discourse, across various arts-based, professional, and scientific disciplines, we can gain a more comprehensive understanding of the scholarship of engagement that incorporates various disciplinary norms and encompasses additional institutional practices, globally.

This research advances our understanding of academics’ experiences in CE by providing multi-dimensional lenses for analysis, encompassing disciplinary, institutional, and individual perspectives, but which is limited in scope to humanities and social science disciplines. A key area for additional investigation is better understanding the CE nexus when academics are working across disciplines, as well as a more robust understanding of how CE and societal impact align with (or complicate) traditional measures of academic success, such as publishing and securing grants. By exploring these intersections, future theoretical contributions can provide valuable insights into how universities can effectively navigate their responsibilities in addressing societal needs while maintaining scholarly rigour. This aspect of future research will be critical in shaping the discourse around the evolving role of higher education institutions in society.

The CEFI and CMCE frameworks presented in this study require additional testing and refinement in a diversity of fields, including in creative practice, and in science, technology, engineering, and mathematics, among other disciplines. Expanding this research to different contexts and disciplines will enrich the body of knowledge and promote more comprehensive approaches to CE practices. There is a need for additional scholarship that examines the academic experience within the broader context that shapes it, encompassing different institutions, countries, and disciplines. By expanding and building upon this research, future theoretical contributions can guide a more nuanced understanding of CE across academe, as a whole, as well as a better understanding of how national government policies, or the needs of local communities, affect CE-related decision-making within universities.

Implications for research practice and administration

The results of this study highlight a number of practical steps that can be taken by disciplines, by individuals, and by universities, to support uptake of CE activities by SSH researchers. At both the disciplinary and institutional levels, for example, strategic planning, funding priorities, and immediate support available to researchers can be (re)considered in light of the global impact agenda, which positions CE as a vital pathway to social change. When taken together, the CEFI and the CMCE provide concrete guidance to disciplinary leaders and to university administrators to identify ways that traditional approaches to academic work must evolve in order to better support impact-focused research activities.

Advance planning for CE requires deep interrogation of existing strategies, policies and practices from an all-of-system perspective. CMCE and CEFI provide frameworks for identifying leverage points from both a micro and a macro level to affect change. For example, a Faculty or School in a university may start this work by mapping its academic disciplines and then use the CEFI to assess the relative ‘fit’ between disciplinary norms and expectations and institutional goals. If a discipline did not provide avenues for funding CE activities, had no mechanisms in place to foster engagement with community, or did not provide publishing avenues to share research results with community members, the Faculty/School could reach out to discipline leaders to advocate for change. Similarly, a scholarly society could use these frameworks to identify CE champions who could serve on accrediting committees, showcase their work at conferences, and serve as editors of CE-focused publications. At the individual level, academics can use these frameworks to position themselves within their university and disciplinary ‘homes’ to identify how CE work is supported (or not supported) at the macro and micro levels. Building one’s awareness of how governments, communities, and other sectoral partners influence and intersect with research priorities is a critical step to understanding what can reasonably be achieved ‘on the ground’ as an individual researcher. For a researcher’s work to inform policy development, a researcher must develop links with potential adopters of research outcomes; the CEFI and CMCE can guide researchers in identifying potential supports for CE, as well as potential gaps in their own networks or skillsets. By better understanding the higher education ecosystem, researchers will be better positioned to improve their research performance, and career trajectory.

Conclusion

With increasing pressure from governments and funders to demonstrate research value to taxpayers, the societal impact imperative is increasing. CE enables translation and adoption of research outcomes by identifying and addressing stakeholders’ needs. While participants talked at length about the rhetoric of CE support at their universities, they struggled to identify tangible support to facilitate CE work. Despite the challenges, participants navigated university, disciplinary, and personal goals to foster successful community partnerships. This study demonstrates that CE requires alignment between researchers, universities, and disciplines. The CEFI Framework () outlines concrete initiatives that scholarly societies, researchers, and university administrators can take to reduce potential barriers to CE and to embed facilitators of CE. By understanding university strategy, researchers can align CE work to institutional goals. When used alongside the Contextual Model of Community Engagement (), researchers, universities, and disciplines can ensure that CE responds appropriately to community, while addressing broader contextual needs. The Framework and Model, taken together, illuminate the complex research ecosystem influencing CE work. These tools can be used in training for researchers to understand the context of their local and disciplinary circumstances, and to create strategic solutions to circumvent disciplinary, individual, and university obstacles. At the university and disciplinary levels, these tools can guide leaders and administrators and help them to attend to relevant issues for embedding CE practices as part of everyday research work. Addressing researchers’ needs at both a macro – and micro-level will ensure that disciplines, universities, and researchers are aligned in their CE pursuits and that our communities are supported and encouraged to work with researchers and institutions to foster social change.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

References

- Ahmed, S.M., C. Maurana, D. Nelson, T. Meister, S.N. Young, and P. Lucey. 2016. “Opening the Black box: Conceptualizing Community Engagement from 109 Community–Academic Partnership Programs.” Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action 10 (1): 51–61. https://doi.org/10.1353/cpr.2016.0019.

- Aiello, E., C. Donovan, E. Duque, S. Fabrizio, R. Flecha, P. Holm, S. Molina, E. Oliver, and E. Reale. 2021. “Effective Strategies That Enhance the Social Impact of Social Sciences and Humanities Research.” Evidence & Policy 17 (1): 131–46. https://doi.org/10.1332/174426420X15834126054137.

- Alperin, J.P., C. Muñoz Nieves, L.A. Schimanski, G.E. Fischman, M.T. Niles, and E.C. McKiernan. 2019. “How Significant are the Public Dimensions of Faculty Work in Review, Promotion, and Tenure Documents?” eLife 8: e42254. https://doi.org/10.7554/eLife.42254.

- Althouse, B.M., J.D. West, C.T. Bergstrom, and T. Bergstrom. 2009. “Differences in Impact Factor Across Fields and Over Time.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 60 (1): 27–34. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.20936.

- Anderson, J.A. 2014. “Engaged Learning, Engaged Scholarship: A Struggle for the Soul of Higher Education.” The Northwest Journal of Communication 42 (1): 143–66.

- Ball, S.J. 2012. “Performativity, Commodification and Commitment: An i-spy Guide to the Neoliberal University.” British Journal of Educational Studies 60 (1): 17–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/00071005.2011.650940.

- Barnett, R. 2015. Thinking and Rethinking the University: The Selected Works of Ronald Barnett. New York: Routledge.

- Barreno, L., P.W. Elliott, I. Madueke, and D. Sarny. 2013. Community Engaged Scholarship and Faculty Assessment: A Review of Canadian Practices. Regina: University of Regina. https://www.mtroyal.ca/AboutMountRoyal/TeachingLearning/CSLearning/_pdfs/adc_csl_pdf_res_revcanpract.pdf.

- Benneworth, P., ed. 2013. University Engagement with Socially Excluded Communities. Springer Netherlands. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-007-4875-0.

- Bentley, P., and S. Kyvik. 2011. “Academic Staff and Public Communication: A Survey of Popular Science Publishing Across 13 Countries.” Public Understanding of Science 20 (1): 48–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662510384461.

- Bernardo, M.A.C., J. Butcher, and P. Howard. 2014. “The Leadership of Engagement Between University and Community: Conceptualizing Leadership in Community Engagement in Higher Education.” International Journal of Leadership in Education 17 (1): 103–22. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603124.2012.761354.

- Besley, J.C., A. Dudo, and S. Yuan. 2018. “Scientists’ Views About Communication Objectives.” Public Understanding of Science 27 (6): 708–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662517728478.

- Bornmann, L. 2013. “What is Societal Impact of Research and how Can it be Assessed? A Literature Survey.” Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology 64 (2): 217–33. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.22803.

- Bourke, A. 2015. Universities, Community Engagement, and Democratic Social Science. Toronto.: York University.

- Boyer, E.L. 1990. Scholarship Reconsidered: Priorities of the Professoriate. Princeton, NJ: Carnegie Foundation for the Advancement of Teaching.

- Boyer, E.L. 1996. “The Scholarship of Engagement.” Journal of Public Service & Outreach 1 (1): 11–20.

- Burgess, M.M. 2014. “From ‘Trust us’ to Participatory Governance: Deliberative Publics and Science Policy.” Public Understanding of Science 23 (1): 48–52. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662512472160.

- Butin, D.W., and S. Seider. 2012. The Engaged Campus: Certificates, Minors, and Majors as the new Community Engagement. New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Carman, M. 2013. “Research Impact: The gap Between Commitment and Implementation Systems in National and Institutional Policy in Australia.” Australasian Journal of University-Community Engagement 8 (2): 1–14.

- Chan, Y.E., and C.J.T. Farrington. 2018. “Community-Based Research: Engaging Universities in Technology-Related Knowledge Exchanges.” Information and Organization 28 (3): 129–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.infoandorg.2018.08.001.

- Chapman, S., A. Haynes, G. Derrick, H. Sturk, W.D. Hall, and A. St. George. 2014. “Reaching “an Audience That you Would Never Dream of Speaking to”: Influential Public Health Researchers’ Views on the Role of News Media in Influencing Policy and Public Understanding.” Journal of Health Communication 19 (2): 260–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/10810730.2013.811327.

- Charmaz, K. 2014. Constructing Grounded Theory (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Clark, T. 2008. “`We’re Over-Researched Here!’: Exploring Accounts of Research Fatigue Within Qualitative Research Engagements.” Sociology 42 (5): 953–70. https://doi.org/10.1177/0038038508094573.

- Crabill, S.L., and D. Butin. 2014. Community Engagement 2.0: Dialogues on the future of the Civic in the Disrupted University. New York: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Dempsey, S.E.. 2010. “Critiquing Community Engagement.” Management Communication Quarterly 24 (3): 359–390.

- Dostilio, L.D. 2017. The Community Engagement Professional in Higher Education: A Competency Model for an Emerging Field. Boston, MA: Stylus Publishing.

- Doyle, J. 2018. “Reconceptualising Research Impact: Reflections on the Real-World Impact of Research in an Australian Context.” Higher Education Research & Development 37 (7): 1366–79. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2018.1504005.

- Du, J.T., and C.M. Chu. 2022. “Toward Community-Engaged Information Behavior Research: A Methodological Framework.” Library & Information Science Research 44 (4), 101189. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2022.101189.

- Dudo, A. 2012. “Towards a Model of Scientists’ Public Communication Activity: The Case of Biomedical Researchers.” Science Communication 35 (4): 476–501. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547012460845.

- Entradas, M., and M.M. Bauer. 2017. “Mobilisation for Public Engagement: Benchmarking the Practices of Research Institutes.” Public Understanding of Science 26 (7): 771–88. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662516633834.

- Fitzgerald, H.E., K. Bruns, S.T. Sonka, A. Furco, and L. Swanson. 2016. “The Centrality of Engagement in Higher Education.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 20 (1): 223–245.

- Flaherty, C. 2014. “So Much To Do, So Little Time.” Inside Higher Ed. April 9. https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/04/09/research-shows-professors-work-long-hours-and-spend-much-day-meetings.

- Given, L.M., W. Kelly, and R. Willson. 2015. “Bracing for Impact: The Role of Information Science in Supporting Societal Research Impact.” Proceedings of the Association for Information Science and Technology 52 (1): 1–10. https://doi.org/10.1002/pra2.2015.145052010048.

- Given, L.M., D. Winkler, and R. Willson. 2014. Qualitative Research Practice: Implications for the Design & Implementation of a Research Impact Assessment Exercise in Australia (pp. 1–31). Wagga Wagga: Research Institute for Professional Practice, Learning and Education.

- Glass, C.R., D.M. Doberneck, and J.H. Schweitzer. 2011. “Unpacking Faculty Engagement: The Types of Activities Faculty Members Report as Publicly Engaged Scholarship During Promotion and Tenure.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 15 (1): 7–30.

- Goodman, H.P. 2014. “The Tie That Binds: Leadership and Liberal Arts Institutions’ Civic Engagement Commitment in Rural Communities.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 18 (3): 119–24.

- Gunter, H.M. 2012. “Academic Work and Performance.” In Vol. 7 of Hard Labour? Academic Work and the Changing Landscape of Higher Education, edited by T. Fitzgerald, J. White, and H.M. Gunter, 65–85.

- Harré, N., B.M. Grant, K. Locke, and S. Sturm. 2017. “The University as an Infinite Game.” Australian Universities Review 59 (2): 5–13.

- Ho, S.S., J. Looi, and T.J. Goh. 2020. “Scientists as Public Communicators: Individual- and Institutional-Level Motivations and Barriers for Public Communication in Singapore.” Asian Journal of Communication 30 (2): 155–78. https://doi.org/10.1080/01292986.2020.1748072.

- Jensen, P., J.-B. Rouquier, P. Kreimer, and Y. Croissant. 2008. “Scientists who Engage with Society Perform Better Academically.” Science and Public Policy 35 (7): 527–41. https://doi.org/10.3152/030234208X329130.

- Langfeldt, L., and L. Scordato. 2015. Assessing the Broader Impacts of Research. A Review of Methods and Practices. Oslo: Nordic Institute for Studies in Innovation, Research and Education (NIFU).

- Leavy, P. 2017. Research Design: Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed Methods, Arts-Based, and Community-Based Participatory Research Approaches. New York: Guilford Press.

- Macfarlane, B. 2007. “Defining and Rewarding Academic Citizenship: The Implications for University Promotions Policy.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 29 (3): 261–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13600800701457863.

- Miller, F.Q. 2015. “Experiencing Information use for Early Career Academics’ Learning: A Knowledge Ecosystem Model.” Journal of Documentation 71 (6): 1228–49. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-04-2014-0058.

- Miller, J. 2019. “Where Does the Time go? An Academic Workload Case Study at an Australian University.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 41 (6): 633–45. https://doi.org/10.1080/1360080X.2019.1635328.

- Moore, T., and J. Morton. 2017. “The Myth of job Readiness? Written Communication, Employability, and the ‘Skills Gap’ in Higher Education.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (3): 591–609. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2015.1067602.

- Mtawa, N.N., S.N. Fongwa, and G. Wangenge-Ouma. 2016. “The Scholarship of University-Community Engagement: Interrogating Boyer’s Model.” International Journal of Educational Development 49: 126–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2016.01.007.

- Neresini, F., and M. Bucchi. 2011. “Which Indicators for the new Public Engagement Activities? An Exploratory Study of European Research Institutions.” Public Understanding of Science 20 (1): 64–79. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963662510388363.

- Olmos-Peñuela, J., E. Castro-Martínez, and P. D’Este. 2014. “Knowledge Transfer Activities in Social Sciences and Humanities: Explaining the Interactions of Research Groups with non-Academic Agents.” Research Policy 43 (4): 696–706. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.respol.2013.12.004.

- Orr, G. 2010. “Academics and the Media in Australia.” Australian Universities Review 52 (1): 23–31.

- Pearson, G. 2001. “The Participation of Scientists in Public Understanding of Science Activities: The Policy and Practice of the U.K.” Research Councils. Public Understanding of Science 10 (1): 121–37. https://doi.org/10.1088/0963-6625/10/1/309.

- Pedersen, D.B., J.F. Grønvad, and R. Hvidtfeldt. 2020. “Methods for Mapping the Impact of Social Sciences and Humanities—A Literature Review.” Research Evaluation 29 (1): 4–21. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvz033.

- Phipps, D., S. Gaetz, and J. Wedlock. 2014. “Editorial: York Symposium on the Scholarship of Engagement.” Scholarly and Research Communication 5 (3): 1–4. https://doi.org/10.22230/src.2014v5n3a169.

- Poliakoff, E., and T.L. Webb. 2007. “What Factors Predict Scientists’ Intentions to Participate in Public Engagement of Science Activities?” Science Communication 29 (2): 242–63. https://doi.org/10.1177/1075547007308009.

- Polkinghorne, S., and L.M. Given. 2021. “Holistic Information Research: From Rhetoric to Paradigm.” Journal of the Association for Information Science and Technology 72 (10): 1261–71. https://doi.org/10.1002/asi.24450.

- Prysor, D., and A. Henley. 2017. “Boundary Spanning in Higher Education Leadership: Identifying Boundaries and Practices in a British University.” Studies in Higher Education, 2210–25. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1318364.

- Purcell, Jennifer W., A. Pearl, and T. Van Schyndel. 2021. “Boundary Spanning Leadership among Community-Engaged Faculty: An Exploratory Study of Faculty Participating in Higher Education Community Engagement.” Engaged Scholar Journal: Community-Engaged Research, Teaching, and Learning 6 (2): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.15402/esj.v6i2.69398.

- Randall, J. 2010. “Community Engagement and Collective Agreements: Patterns at Canadian Universities.” In The Community Engagement and Service Mission of Universities, edited by P. Inman, and H.G. Schütze, 261–77. Leicester: National Institute of Adult Continuing Education (England and Wales): NIACE.

- Reale, E., D. Avramov, K. Canhial, C. Donovan, R. Flecha, P. Holm, … R. Van Horik. 2017. “A Review of Literature on Evaluating the Scientific, Social and Political Impact of Social Sciences and Humanities Research.” Research Evaluation 27 (4): 298–308. https://doi.org/10.1093/reseval/rvx025.

- Sandmann, L.R. 2008. “Conceptualization of the Scholarship of Engagement in Higher Education: A Strategic Review, 1996–2006.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach & Engagement 12 (1): 91–104.

- Savan, B., S. Flicker, B. Kolenda, and M. Mildenberger. 2009. “How to Facilitate (or Discourage) Community-Based Research: Recommendations Based on a Canadian Survey.” Local Environment 14 (8): 783–96. https://doi.org/10.1080/13549830903102177.

- Schimanski, L.A., and J.P. Alperin. 2018. “The Evaluation of Scholarship in Academic Promotion and Tenure Processes: Past, Present, and Future.” F1000Research 7: 1605. https://doi.org/10.12688/f1000research.16493.1.

- Smith, K.M., F. Else, and P.A. Crookes. 2014. “Engagement and Academic Promotion: A Review of the Literature.” Higher Education Research & Development 33 (4): 836–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.863849.

- Trench, B., and S. Miller. 2012. “Policies and Practices in Supporting Scientists’ Public Communication Through Training.” Science and Public Policy 39 (6): 722–31. https://doi.org/10.1093/scipol/scs090.

- Turner, V.K., K. Benessaiah, S. Warren, and D. Iwaniec. 2015. “Essential Tensions in Interdisciplinary Scholarship: Navigating Challenges in Affect, Epistemologies, and Structure in Environment–Society Research Centers.” Higher Education 70 (4): 649–65. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9859-9.

- Watermeyer, R. 2014. “Impact in the REF: Issues and Obstacles.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (2): 199–214. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.915303.

- Watermeyer, R. 2015. “Lost in the ‘Third Space’: The Impact of Public Engagement in Higher Education on Academic Identity, Research Practice and Career Progression.” European Journal of Higher Education 5 (3): 331–47. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2015.1044546.

- Watson, D. 2007. Managing Civic and Community Engagement. England: Open University Press.

- Weerts, D.J., and L.R. Sandmann. 2010. “Community Engagement and Boundary-Spanning Roles at Research Universities.” The Journal of Higher Education 81 (6): 632–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2010.11779075.

- Welch, M., and S. Plaxton-Moore. 2017. “Faculty Development for Advancing Community Engagement in Higher Education: Current Trends and Future Directions.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 21 (2): 131–66.

- Wendling, L.A. 2020. “Valuing the Engaged Work of the Professoriate: Reflections on Ernest Boyer’s Scholarship Reconsidered.” Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 20 (2), https://doi.org/10.14434/josotl.v20i2.25679.

- Wenger, L., L. Hawkins, and S.D. Seifer. 2012. “Community-engaged Scholarship: Critical Junctures in Research, Practice, and Policy.” Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement 16 (1): 171–82.

- Whiteford, L., and E. Strom. 2013. “Building Community Engagement and Public Scholarship Into the University.” Annals of Anthropological Practice 37 (1): 72–89. https://doi.org/10.1111/napa.12018.

- Wilkinson, C., and E. Weitkamp. 2013. “A Case Study in Serendipity: Environmental Researchers use of Traditional and Social Media for Dissemination.” PLoS ONE 8 (12): e84339. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0084339.

- Willson, R. 2018. “Systemic Managerial Constraints: How Universities Influence the Information Behaviour of HSS Early Career Academics.” Journal of Documentation 74 (4): 862–79. https://doi.org/10.1108/JD-07-2017-0111.

- Willson, R., and L.M. Given. 2020. “I’m in Sheer Survival Mode”: Information Behaviour and Affective Experiences of Early Career Academics.” Library and Information Science Research 42 (2), 101014. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lisr.2020.101014.

- Winter, A., J. Wiseman, and B. Muirhead. 2006. “University-community Engagement in Australia Practice, Policy and Public Good.” Education, Citizenship and Social Justice 1 (3): 211–30. https://doi.org/10.1177/1746197906064675.

- Youn, T.I.K., and T.M. Price. 2009. “Learning from the Experience of Others: The Evolution of Faculty Tenure and Promotion Rules in Comprehensive Institutions.” The Journal of Higher Education 80 (2): 204–37. https://doi.org/10.1353/jhe.0.0041.

- Zuber-Skerritt, O. 2015. “Participatory Action Learning and Action Research (PALAR) for Community Engagement: A Theoretical Framework.” Educational Research for Social Change 4 (1): 5–25.