ABSTRACT

Placement as a form of work-integrated learning is a valued element of undergraduate education. Prior work explores how placement provides a site for developing professional values, skills and competences as well as identifying how students build awareness of professional requirements. Greater focus on how such processes of awareness are realised, negotiated and enacted is still required. This study frames student placement experiences as enabling processes of recursive negotiation between the self and the setting. The empirical contribution is to document and track this with 40 students on accounting placements, interviewed at three points in time (pre-, during, post-placement) exploring their subjective experiences. Findings evidence various trajectories of experience emerging from which a model capturing four distinct forms of fit (personal, reflected, projected, absence of fit) with professional identity is developed. This suggests student placement experiences in all their variations lead to and constitute more than merely technical or academic outcomes. Conceptually framing placement experiences as recursive negotiations between the self and the setting in the professionalisation journey uncovers how professional identity formation processes are constructed and (re)negotiated. As well as providing students with terminology to understand and articulate the multiplicity of possible placement experiences, educators, employers and professional bodies can benefit from the more nuanced possibilities for work-integrated learning that are suggested.

Introduction

Placement, a form of professional work-integrated learning (WIL) (Dean et al. Citation2020), is a planned period of learning outside the university setting. A rich stream of work is beginning to emerge which focuses on students’ experiences of placement, particularly around their ‘belonging’ or ‘becoming’ associated with placement (Oliveira Citation2015; Trede and McEwen Citation2015). Such work, often centred around employability concerns, explores students’ awareness of, and connection to, requirements for professional careers and identities acquired during placement. In highlighting the re-framing of the ‘employability problem’ as one of enhancing graduates’ personal and socio-cultural resources, which is in turn enabled and enacted in the development of occupational or professional identities, Tomlinson and Jackson (Citation2021) call for qualitative, narrative data exploring this process of identity development.

Professional identity refers to how individuals define themselves in professional roles (Ashforth and Schinoff Citation2016). Reviewing the placement literature, Trede (Citation2012) found that only 20 of 192 studies explicitly referred to development of professional identity (PI). Trede (Citation2012, 160) critiqued these 20 studies stating that they ‘implied that professional identity is formed along the way’ rather than ‘squarely focus on professional identity formation’, which she labels as a ‘significant, yet often hidden, outcome’ of placement. Similarly, Nadelson et al. (Citation2017) state that there is limited understanding of how students develop PIs. Building on such work this study makes a number of key contributions: (i) to better understand the experiences of students going into, during and coming out of placement, enriching discussions of placement outcomes beyond the technical or academic, (ii) to focus on how PI formation processes emerge, identified by prior studies as a lacuna in the existing WIL literature, (iii) to conceptually frame placement as a process of recursive negotiation between the self and the setting in the professionalisation journey. Attention is paid to the interplay between the individual and others in the placement context and the processes through which fit with PIs is constructed and (re)negotiated in and through that context. The final contribution therefore is (iv) to capture the variation in PI formation, alluded to by Trede (Citation2012) and Nadelson et al. (Citation2017), by allowing multiple trajectories to emerge as students negotiate different forms of fit during their placement experiences. A model representing trajectories of experience leading to four forms of negotiated fit is presented.

We first present a review of extant research on placement experiences, focusing particularly on PI formation. We detail the methods employed in this study and present the findings structured in terms of the four forms of fit that emerged.

Placement as a space for developing professional identity (PI)

Calls for placement and growing popularity of placement as part of degree programmes, suggest that placement is a valued element of undergraduate education for students, particularly for those preparing for entry to professions such as accounting, medicine and law, as well as areas such as social work, occupation therapy and nursing. In the specific context of accounting roles, placement has been investigated as an opportunity to develop the skills and competences required by potential employers (Paisey and Paisey Citation2010), to improve academic performance (Lucas and Tan Citation2014) and to validate career choice (Jackson Citation2017), with contributors suggesting that there is a lot more to placement than the specific outcomes they had chosen to consider and that much remains to be investigated. As identified by Jackson (Citation2017), Trede (Citation2012) and Nadelson et al. (Citation2017) more research is required to understand how placement provides a site for PI development.

A body of work by Jackson [including Jackson (Citation2017), Jackson and Collings (Citation2018) and Tomlinson and Jackson (Citation2021)] has begun to explore this. Jackson (Citation2017, 833) refers to developing PI during placement as pre-professional identity, defining pre-professional identity as:

a complex phenomenon spanning awareness of and connection with the skills, qualities, behaviours, values and standards of a student’s chosen profession, as well as one’s understanding of professional self in relation to the broader general self.

Additionally, because Jackson and colleagues consider placement in the context of graduate employability, when looking at processes of awareness, Jackson argues that students need a clear understanding of the elements of their chosen profession that enable an individual to ‘operate successfully in the workplace’ (Citation2017, 836) and Tomlinson and Jackson (Citation2021, 5) argue that students need to ‘make themselves attractive to potential employers’. While meeting the requirements of others (and being legitimised for it) is an important aspect of constructing fit with possibilities, the influence of students’ own evolving self-view is also an important element of constructing fit with possible future PIs. Tomlinson and Jackson (Citation2021, 886) present PI formation as a ‘narrative trajectory that entails a set of schematic ideas about a desired future self and how this connects more broadly to individuals’ sense of who they are in relation to work’. The formation of pre-professional identities augments the professional socialisation process that takes place following entry to the labour market (Tomlinson and Jackson Citation2021) and allows higher education students space for engagement in self-authorship (Baxter Magolda Citation1998), as well as affording potential to build social and cultural capital relevant to that identity. As identified above, the duration of placement may affect opportunities for connection to take place, in addition negotiation may be affected by the adequacy of tasks and support provided (D'abate, Youndt, and Wenzel Citation2009; Muhamad et al. Citation2009; Paisey and Paisey Citation2010). How exactly this happens, however, while posited, is not empirically evidenced in studies to date.

Identity is defined by Ashforth, Harrison, and Corley (Citation2008, 327) as ‘a self-referential description that provides contextually appropriate answers to the question “Who am I?”’ If identity is how individuals define themselves, then professional identity is how individuals define themselves in professional roles (Ashforth and Schinoff Citation2016; Ibarra Citation1999; Pratt, Rockmann, and Kaufmann Citation2006). This paper conceptualises placement as an important element in the trajectory of PI formation. Given our framing of PI formation as an ongoing trajectory, we use the term PI to encompass early stages of pre-professional identity formation, including that in placement settings. All such forms of negotiation are seen as identity work and categorising one form as pre-professional and another as professional identity formation may not be reflective of experiences. In preparing for, engaging in, and reflecting on placements students engage in recursive negotiation between the self and the setting, the contextually appropriate identity work described by Ashforth, Harrison, and Corley (Citation2008) above. Framing identity formation processes in this way allows for multiple ways of constructing fit with multiple, and even conflicting, contextual PI options.

To investigate such processes of recursive negotiation of identity in a given placement context we draw on Ashforth, Harrison, and Sluss (Citation2014, 23) who state that the following major identity questions face individuals as they engage in an organisation:

(1) what does it mean to be a shipping agent (or whatever the job may be), particularly in this organization?; (2) what does it mean, more broadly, to be a member of this organization?; (3) how do this job and broader role resonate with how I see myself and, importantly, how I want to see myself?, (4) how do I come to be—and be seen as—a legitimate exemplar of this desired self?

This negotiation between being legitimised by others and evolving self-view is common in the PI literature. Ibarra describes this negotiation as individuals engaging in trials of possible future selves in the dynamic between ‘authenticity’ (Citation1999, 778) and ‘situational factors’ (782). Identity (re)development, therefore, is a fluid process which involves continual negotiation between being legitimised by others and one’s own evolving self-view, with placement providing an ideal ‘space’/‘time’ within which to test this out or to ‘trial’ a future possible self (in the terminology of Ibarra). Pratt (Citation2000, 456–7) describes this as individuals changing how they ‘think and feel about themselves’ through membership of an organisation. Others describe evolving self-view as occurring from ‘identity work’ (Alvesson and Willmott Citation2002, 622) by the individual. Sveningsson and Alvesson (Citation2003, 1165) define identity work as:

forming, repairing, maintaining, strengthening or revising the constructions that are productive of a sense of coherence and distinctiveness.

As well as an evolving self-view, legitimisation by others may be required for enacted identities to ‘take root’ (Ashforth and Schinoff Citation2016, 125). Ashforth, Harrison, and Sluss (Citation2014, 24) state that individuals claim to an identity needs to be reinforced by ‘important audiences’ for ‘one to truly accept the claim as legitimate’. Being legitimised by others is described as social validation (Ashforth and Schinoff Citation2016), external feedback (Ibarra Citation1999) or respect from others (Rogers, Corley, and Ashforth Citation2017). Rogers, Corley, and Ashforth (Citation2017, 220) find that legitimisation by others, provided by way of respect from others, gave inmates in their study of prisoners working for a marketing services organisation, a sense of ‘worth as organisational members’ that promoted self-transformation.

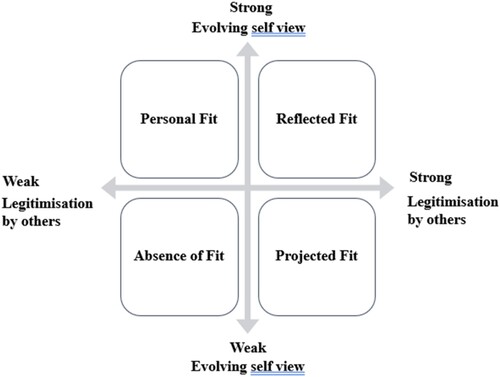

Individuals continuously interpret activities and construct identities by incorporating what is acceptable in the organisation and their own self-views (Alvesson and Willmott Citation2002; Ibarra Citation1999; Kira and Balkin Citation2014). This study conceptualises the formation of PI as a continuous recursive negotiation between fulfilling, or being seen to fulfil, organisational requirements (legitimisation by others) and individuals’ evolving self-view of who they see themselves becoming. We frame students’ experiences of placement against these two axes of ‘legitimisation by others’ and ‘evolving self-view’ and in their accounts trace how their sensemaking around self in this placement context constructs differing forms of fit with identity possibilities. Instead of having to embrace a particular PI, placement may be an opportunity for students to make sense of multiple possible PIs and imagine how they see themselves fitting with a range of possibilities. Exploration of the complex (re)negotiation between legitimation by others and evolving self-view as future professionals will therefore further our understanding of how students make sense of their experiences in association with placement.

Methodology

To gain access to the subjective worlds of higher education students, and to capture their placement experiences, 40 students from one Irish university completing placements in accounting roles were interviewed at three points in time (pre-, during and post-placement). Ethical approval was obtained for the study and permission was granted to invite students from across three different programmes in the university’s Business School to participate: Bachelor of Science (Accounting), Bachelor of Science (Finance) and Bachelor of Commerce. The main focus of the BSc (Accounting) programme is Accounting. However accounting modules constitute a significant portion of the other two programmes with the difference between programmes determined by the modules accompanying those accounting modules. The BSc (Finance) has finance and economics modules, whereas the BComm has broader business modules such as management, marketing and food business. In many instances, students are co-taught for the accounting modules. The programmes hold broadly similar levels of exemptions from professional accountancy examinations and each offers accounting placement roles to students. Placement (minimum 6 months duration) is a core component of third (penultimate) year of each programme and required to progress to fourth year and graduate with honours.

Given that two of the researchers were faculty members in the participants’ University the third researcher (not a faculty member at the research site) attended placement preparation sessions provided for students and requested volunteers for the study. Thus, ensuring voluntary consent for participation without ethical concerns about power relations for students to faculty members. Inclusion criteria were placement in an accounting role (the researchers were happy with the breadth and scope of how these roles were defined by the university’s placement officers) and interest in an accounting career. All participants therefore identified with accounting as a profession and as a possible future graduate employment destination. summarises the profile of the students interviewed, based on programme of study and placement destination.

Table 1. Profile of participants.

Semi-structured interviews were conducted in person by one of the researchers. Each interview was audio-recorded (with the interviewee’s permission) and transcribed. Broad open-ended questions allowed interviewees to lead the conversation. The first round of interviews (pre-placement; interview 1) commenced after students were offered placement positions, but before they started in the workplace. The focus of this round of interviews was on determining how students made sense of what could be expected of them and how they imagined themselves fitting those expectations. The second round of interviews (during placement; interview 2) took place approximately halfway through the placement period and focused on exploring how students’ understandings and expectations were amended or strengthened during placement. The final round of interviews (post-placement; interview 3) took place six to twelve weeks after the students had returned to university, allowing time for reflection on their experiences. These conversations were more reflective in tone, focused on determining how understandings and expectations changed during placement and continued to change after return to university.

Thematic analysis (Braun and Clarke Citation2015) of the data provided an approach to explore nuanced experiences and to examine the interplay between evolving self-views and experiences of legitimisation by others. Using chronological coding and an inductive approach, pre-placement transcripts were coded first, then during placement transcripts and finally post-placement transcripts. This facilitated the emergence of a variety of experiences among students at each stage. The transcripts were then coded student by student, which allowed for the exploration of different trajectories of PI formation.

In this study thematic analysis consisted of three distinct stages. The first stage involved identifying 34 codes from students’ descriptions of experiences of connecting with what they perceived as being required in accounting roles. These codes were then grouped under six higher-order codes, reflecting the different ways in which students described others’ assessments of their suitability to future roles as accounting professionals and their own assessments of alignment with what they perceived as being required of them as accounting professionals. The second stage involved interrogating each of the six higher-order codes to determine how they influenced students’ construction of fit with becoming accountants.

The third stage of analysis involved exploring the interaction between the influences of being legitimised by others and evolving self-view as a future accounting professional. The strength of each of the influences on constructing fit with becoming future accounting professionals was categorised as being either a ‘strong’ or a ‘weak’ influence. Being ‘legitimised by others’ was categorised as a strong influence where there were experiences of instigating fit and creating an impression of fit, and as a weak influence where there were experiences of supporting fit and not affecting those no longer seeking fit. ‘Evolving self-view as a future accounting professional’ was categorised as a strong influence where there were experiences of confirming fit and discovering fit, and as a weak influence where there were experiences of acting fit and no longer seeking fit. As a result of this analysis, new themes called personal, reflected, projected and absence of fit were created. On-going generative dialogue about coding and interpretative choices occurred iteratively between the three researchers which brought rigour to the analysis.

Findings

The findings evidence complex on-going, recursive (re)negotiation of potential future professional selves, informed by the influence of legitimisation by others and evolving self-views and the complex interaction between these two influences, before, during and after placement experiences. summarises such processes of identity formation around placement experiences as being the construction of one of four possible forms of fit.

Figure 1. Forms of fit.

Legitimisation by others in the context of this study represents the influence of being assessed by others to fit with accounting roles. Interviewees described experiences of being accepted as part of the team (for example, invited to social events or having placement contracts extended), being given more responsibilities (for example, being asked to mentor others and to complete graduate-level tasks) and receiving feedback as providing them with legitimisation by others. For those requiring reassurance of fit or evidence of having created an impression of fit, their experiences were categorised as strongly influencing the construction of fit with possibilities in accounting roles. For example:

They were really impressed by my work and they kept asking me for more and more. That was good … encouraging … I began to think to myself ‘this is something I am good at. This is something that I could do’. (John 3).

[The senior manager] was praising me in front of all the partners … all this praise was just the icing on the cake. I was happy there, I know even in the first week or two that I loved it. But it was great to hear him saying it to others as well. (Don 3).

I loved every bit of it. I got a real buzz from what I was doing. There is a lot more to it than what we learn in college. I love accounting subjects in college, but the reality of doing it was even better. (Daniel 2).

When I was in there I did a lot of IT work. I think I would be more suited to something like that. I thought numbers and accounting is what I was suited to, but it is actually more the IT side that I am better at. (Rose 3).

Personal fit

‘Personal fit’ is constructed from a strong evolving self-view as a future accounting professional, requiring little or no legitimisation by others. Students occupying this quadrant were typically those that were certain before placement that possibilities in accounting could be for them. For example, in his pre-placement interview Daniel stated that he felt he had the skills needed for his accounting role:

I can talk to anyone. I have been working on computers since secondary school so I’m comfortable with IT. My people skills and the IT skills that I have will stand to me in there. (Daniel 1).

I loved the work. It is what I want to do. I was in my element. Them giving me … not only the usual work but lots, lots, more … more than they usually would give a placement student definitely helped. But I knew accounting was for me anyway. I loved it. (Linda 3).

Reflected fit

‘Reflected fit’ is constructed when legitimisation by others is the driving force underpinning the development of a strong evolving self-view. This is akin to sense-giving where newcomers to an organisation ‘place great stock’ (Ashforth and Schinoff Citation2016, 125) in information and interpretations provided by their peers and managers, in a sense of fit being ‘mirrored’ back to students by those around them. For example, Valerie states:

If managers keep coming to you with jobs and you are the one that is facing the client and given the tougher cases than the other interns, of course you feel valued. You begin to realise you can do it. My point of view changed, and my mind-set changed. Accounting is now top of my career choice. I never thought I’d love accounting this much. (Valerie 2).

It was a real eye-opener for me. They were really impressed by my work, and they kept asking me for more and more. That was good … Encouraging … I began to think to myself ‘this is something I’m good at; this is something that I could do’. (John 3).

When I was put on a team with people from all different sections, I was the one saying ‘guys, do you want to meet up and come up with a strategy’. That would not have been me before placement. I would have just sat there and waited or just turned up. It clicked then that I was more confident in my role. I was taking responsibility. I could see myself starting to feel like a real accountant. (Jane 3).

Projected fit

‘Projected fit’ is constructed when there is a strong desire to be seen by others to fit with professional possibilities, even though these possibilities are not what students really want but represent stepping-stones to what individuals see themselves becoming. For example, Carol outlines an instrumental view of accounting:

The work is too boring to be honest. But I'll do it. I’ll do it for as long as it takes … It is not what I will be doing for the rest of my life … It is a great qualification to have. It is a stepping-stone that is all. (Carol 3).

One night I stayed until 9pm because we were signing off on the accounts … . Even though I was dying to go I stayed and made sure to look busy anyway, as if I had an interest. (Carol 3).

Legitimisation by others was a signal to these students of their success in creating an impression of fit.

I got my contract. That is a sign for me that they were impressed with the effort that I put in. That is all I wanted from placement … to get the contract. I don’t know if I’d have got that if they knew that I will be out of accounting as soon as I qualify, it’s not really what I want to do long-term. (Regina 3).

Absence of fit

‘Absence of fit’ is constructed from a lack of evolving self-view as a future accounting professional resulting in students no longer seeking fit with becoming accountants. For some, this was a new discovery, but for others it was something considered from the outset of their placement journey. Because these students were no longer seeking fit, they were unaffected by legitimisation by others. Alice opined:

I got really good feedback and I was happy with that. Of course, it is nice to hear you are doing well. But still … I don’t think accounting is for me. I would be more interested in economics. I think I will go off and do something in economics. (Alice 3).

I knew my work was important, I knew that from the feedback from investment managers every day. But in terms of a personal connection with work, I didn’t have that. I think you should go into a career you love, not just for the money. I really wanted to love the work … but I didn’t love accounting. (Hugh 3).

Discussion and implications

In line with other studies the findings of this study suggest undergraduate placement offers students more than an opportunity to achieve instrumental outcomes (for example, employability, academic grades/success), but also presents opportunities to influence students’ emerging PIs. Prior work suggested identity formation as a ‘crucial bridge’ (Tomlinson and Jackson Citation2021, 898) between higher education and future professional employment / identity development and called for additional research to explore in more depth the processes through which identity formation was constructed and (re)negotiated in association with placement. This study responds to calls (Nadelson et al. Citation2017; Trede Citation2012) for narrative data exploring the processes of PI development of higher education students. Our findings document how PIs are formed and influenced by placement experiences, thereby highlighting the importance of identity crafting prior to formal graduate entry to the labour market. Capturing the dynamic nature of this identity crafting as we conceptually frame the student experience of placement as an enabling process of recursive negotiation between the self and the setting extends our understanding of such processes.

Focusing on this dynamic, recursive process of negotiation allows us to inform the developing conversation evidenced in the work of Trede (Citation2012), Nadelson et al. (Citation2017), and a stream of work by Jackson (Citation2017), Jackson and Collings (Citation2018) and Tomlinson and Jackson (Citation2021). While Jackson’s work has very usefully begun to explore how students become aware of what could be expected of them in their chosen profession, how they use this growing awareness to construct fit with possible future selves has been under-explored. Perhaps the longitudinal nature of this study, compared to previous work, allowed for greater reflection by students on their experiences. Each individual journey is fluid; collectively they comprise four distinct trajectories of experience, none of which is inevitable, pre-ordained or immutable. Thus, constructing fit is not a binary outcome, either fitting or not with becoming, in this case, accountants. In contrast, an original model of differing forms of fit and how they occur in the negotiation between being legitimised by others and evolving self-view is presented. This model highlights trajectories to Personal fit, Reflected fit, Projected fit and Absence of fit with becoming future accounting professionals.

The research sample in our study had chosen degree programmes relevant to accounting, as well as placements in accounting roles, but the placement experiences of some led to an absence of fit with becoming an accountant. Meeting employers’ expectations (and being legitimised for it) had a strong influence on some students, either instigating the discovery of fit with becoming accountants (Reflected fit) or signalling success at having created an impression of fit (Projected fit) with possibilities. However, it only supported fit for those students confirming fit (Personal fit) and had no influence on those that were no longer seeking fit with becoming accountants (Absence of fit). The placement experiences of different students occupy different spaces in the model, but the important thing is that all these spaces are legitimate forms of fit with becoming future accounting professionals. No longer seeking fit with possible selves as future accounting professionals is just as valued an outcome as retaining, strengthening or creating new possible future selves as future accounting professionals.

This study contributes to work by Jackson (Citation2017) and Tomlinson and Jackson (Citation2021) by extending concepts of ‘awareness’ and ‘connection’ in two ways. Firstly, by exploring how connection begins to emerge and then may develop into a strong sense of alignment or personal fit with identities, but also where fit may be faked (Projected fit) or not experienced (Absence of fit). Thus awareness–connection–fit may be one trajectory experienced but there are other trajectories such as awareness–connection-projected or absence of fit. Secondly, by recognising that there may be variety in what we connect or fit to in professional contexts. Put simply that there may be multiple ways of constructing fit with multiple contextualised PI options. Tomlinson and Jackson (Citation2021) explore concepts such as ‘familiarity’ and ‘proximity’ and our findings confirm these as key influences on emerging PI, regardless of whether that emerging identity is established, reinforced, projected or rejected during placement. Even in the absence of fit and rejection of an emerging PI as accountants, students may generate ‘cultural capital’ (Tomlinson and Jackson Citation2021) to be carried forwards into future roles and professional working selves, as ongoing self-authorship of PI.

A key contribution of this study is to draw attention to the recursive negotiation between self and context that scaffolds trajectories of experience associated with placement. By doing so the findings of this study broaden discussions within the placement literature about the range of experiences and outcomes associated with placement, in particular answering calls for more in-depth work about the nature of PI development around placement and other forms of WIL. The key determinant in our research approach is the negotiation between self and context, rather than context itself. We highlight that the influence of context on PI formation is a reciprocal, recursively negotiated one. Two students in the ‘same’ work context may potentially experience different trajectories, echoing Ibarra’s (Citation1999) commentary on the dynamic between authenticity and situational factors. Each specific workplace context is likely to offer multiple PI possibilities, with two students from the same programme and working in the same organisation having different experiences. There is also the potential here to add to discussions about the employability problem (Tomlinson and Jackson Citation2021) as variation in how one can fit to work contexts is demonstrated, even ‘faking’ that fit (via Projected fit) to create an impression of employability.

Practical implications

Viewing placement experiences through the lens of forms of fit offers university faculty and professional staff, as well as employers and disciplinary-based professional bodies, a more nuanced view of placement activity and of how best to support individual students throughout that journey. In particular, it sensitises stakeholders to differing patterns of experience and PI trajectories emerging from placement. In turn, the different trajectories presented provide a useful framework for analysis and reflection on those experiences, extending the vocabulary for students, educators and wider stakeholders to understand a wider range of placement experiences and outcomes and, particularly, affording stakeholders the opportunity to consider that ‘personal fit’ is not the only valuable trajectory of experience. By highlighting the legitimacy of different trajectories of experience it allows for students to develop different senses of their own journey to employability beyond the more narrowly focused, often competency based, accounts in the dominant approaches to employability. Employability can then be seen as an ongoing negotiated process rather than a singular destination or narrow professional track. Future research could usefully explore this further, to better support work-integrated learning or placement programmes.

The findings enable educators to better devise intended learning outcomes recognising all four forms of fit as valid and valuable processes in association with placement and to be reflected in assurances of learning assessments. At a practical level, students can be prepared for differing processes of constructing fit with developing PIs. The model developed in this study gives students the terminology to understand and articulate their own progress in association with placement. Drawing on the model developed here enables professional bodies to recognise and support multiple trajectories for developing PI and acknowledges multiple influences on, and outcomes to, that process.

Concluding remarks

While accounting was the site for this study, the model developed has potential to contribute to theorising how PIs across other professions are crafted through a process of negotiation and legitimised as one of four forms of fit. The meanings negotiated within one particular social and professional context may be different to another. A useful avenue for future research in higher education is to draw on this model as a lens to explore patterns of experience and trajectories in other professions. In fact, the findings of this research conceptually have something interesting to say about constructing fit as individuals go through any period of transition, for example for graduates entering the workplace or employees being promoted to new roles within an organisation. All of these provide interesting potential future areas of research.

With many professions and employers concerned with broadening the talent pool and being more inclusive, this study offers a model to understand and support a more diverse range of higher education students across WIL experiences and into employment. As we have seen there are differing patterns of experience and multiple routes into and out of a professional trajectory. At its heart, these involve a negotiation between the self and how such evolving selves are legitimised (or not) in everyday practices, and thus are malleable and open to organisational influences. Awareness of this model and thinking creatively about how to support legitimisation across placements and indeed later induction and socialisation (through for example mentoring, feedback, and supportive supervision) may be a route to enhancing diversity and inclusion across professions.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Alvesson, M., and H. Willmott. 2002. “Identity Regulation as Organisational Control: Producing an Appropriate Individual.” Journal of Management Studies 39 (5): 619–44. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-6486.00305

- Ashforth, B. E., S. H. Harrison, and K. G. Corley. 2008. “Identification in Organizations: An Examination of Four Fundamental Questions.” Journal of Management 34 (3): 325–74. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206308316059

- Ashforth, B. E., S. H. Harrison, and D. M. Sluss. 2014. “Becoming: The Interaction of Socialization and Identity in Organizations Over Time.” In Time and Work: Volume 1: How Time Impacts Individuals, edited by A. J. Shipp, and Y. Fried, 11–39. London: Psychology Press.

- Ashforth, B. E., and B. S. Schinoff. 2016. “Identity Under Construction: How Individuals Come to Define Themselves in Organizations.” Annual Review of Organizational Psychology and Organizational Behavior 3 (1): 111–37. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-orgpsych-041015-062322

- Baxter Magolda, M. B. 1998. “Developing Self-Authorship in Young Adult Life.” Journal of College Student Development 39 (2): 143–156. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2003.0020

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2015. “Thematic Analysis.” In Qualitative Psychology: A Practical Guide to Research Methods, edited by V. Clarke, V. Braun, and N. Hayfield, 222–48. London: Sage Publication.

- Brown, A. D. 2020. “Identities in Organizations.” In The Oxford Handbook of Identities in Organizations, edited by A. D. Brown, 1–31. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Covaleski, M. A., M. W. Dirsmith, J. B. Heian, and S. Samuel. 1998. “The Calculated and the Avowed: Techniques of Discipline and Struggles Over Identity in Big Six Public Accounting Firms.” Administrative Science Quarterly, 293–327. https://doi.org/10.2307/2393854

- D'abate, C. P., M. A. Youndt, and K. E. Wenzel. 2009. “Making the Most of an Internship: An Empirical Study of Internship Satisfaction.” Academy of Management Learning & Education 8 (4): 527–39.

- Dean, B., V. Yanamandram, M. Eady, T. Moroney, and N. O’Donnell. 2020. “An Institutional Framework for Scaffolding Work-Integrated Learning Across a Degree.” Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice 17 (4): article 6.

- Ewan, C. 1988. “Becoming a Doctor.” In The Medical Teacher, edited by K. Cox, and C. Ewan, 83–87. Edinburgh: Churchill Livingstone.

- Ibarra, H. 1999. “Provisional Selves: Experimenting with Image and Identity in Professional Adaptation.” Administrative Science Quarterly 44 (4): 764–91. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667055

- Jackson, D. 2017. “Developing pre-Professional Identity in Undergraduates Through Work-Integrated Learning.” Higher Education 74 (5): 833–53. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-016-0080-2

- Jackson, D., and D. Collings. 2018. “The Influence of Work-Integrated Learning and Paid Work During Studies on Graduate Employment and Underemployment.” Higher Education 76 (3): 403–25. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-017-0216-z

- Kira, M., and D. B. Balkin. 2014. “Interactions Between Work and Identities: Thriving, Withering, or Redefining the Self?” Human Resource Management Review 24 (2): 131–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrmr.2013.10.001

- Lucas, U., and P. Tan. 2014. “Developing the Reflective Practitioner: Placement and the Ways of Knowing of Business and Accounting Undergraduates.” Teaching in Higher Education 19 (7): 787–98. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2014.901954

- Muhamad, R., Y. Yahya, S. Shahimi, and N. Mahzan. 2009. “Undergraduate Internship Attachment in Accounting: The Interns Perspective.” International Education Studies 2 (4): 49–55. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v2n4p49

- Nadelson, L., S. McGuire, K. Davis, A. Farid, K. Hardy, Y. Hsu, and S. Wang. 2017. ““Am I a STEM Professional?” Documenting STEM Student Professional Identity Development.” Studies in Higher Education 42 (4): 701–20.

- Oliveira, G. 2015. “Employability and Learning Transfer: What Do Students Experience During Their Placements?” Studia Paedagogica 20 (4): 123–38. https://doi.org/10.5817/SP2015-4-8

- Paisey, C., and N. Paisey. 2010. “Developing Skills via Work Placements in Accounting: Student and Employer Views.” Accounting Forum 34 (2): 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.accfor.2009.06.001

- Pratt, M. G. 2000. “The Good, the Bad, and the Ambivalent: Managing Identification among Amway Distributors.” Administrative Science Quarterly 45 (3): 456–93. https://doi.org/10.2307/2667106

- Pratt, M. G., K. W. Rockmann, and J. B. Kaufmann. 2006. “Constructing Professional Identity: The Role of Work and Identity Learning Cycles in the Customization of Identity among Medical Residents.” Academy of Management Journal 49 (2): 235–62. https://doi.org/10.5465/amj.2006.20786060

- Reid, E. 2015. “Embracing, Passing, Revealing, and the Ideal Worker Image: How People Navigate Expected and Experienced Professional Identities.” Organization Science 26 (4): 997–1017. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.2015.0975

- Rogers, K. M., K. G. Corley, and B. E. Ashforth. 2017. “Seeing More Than Orange: Organizational Respect and Positive Identity Transformation in a Prison Context.” Administrative Science Quarterly 62 (2): 219–69. https://doi.org/10.1177/0001839216678842

- Sveningsson, S., and M. Alvesson. 2003. “Managing Managerial Identities: Organizational Fragmentation, Discourse and Identity Struggle.” Human Relations 56 (10): 1163–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/00187267035610001

- Tomlinson, M., and D. Jackson. 2021. “Professional Identity Formation in Contemporary Higher Education Students.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (4): 885–900. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1659763

- Trede, F. 2012. “Role of Work-Integrated Learning in Developing Professionalism and Professional Identity.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Cooperative Education 13 (3): 159–67.

- Trede, F., and C. McEwen. 2015. “Early Workplace Learning Experiences: What are the Pedagogical Possibilities Beyond Retention and Employability?” Higher Education 69 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9759-4

- Vough, H. C., B. B. Caza, and S. Maitlis. 2020. “Exploring the Relationship Between Identity and Sensemaking.” In The Oxford Handbook of Identities in Organizations, edited by A. D. Brown, 244–60. Oxford: Oxford University Press.