ABSTRACT

The paper examines preconceptions and assumptions behind common understandings of ‘scholarship awards’ in international higher education research, and analyses how these influence the production of knowledge on scholarship programs and their effects. The paper aims to make a major theoretical contribution by proposing an alternative approach to studying these programs. First, drawing on a comprehensive review of the scholarships literature, the paper posits that prevalent theoretical approaches – often drawn from the logic of the scholarship programs themselves – limit our view of what scholarship programs do and can do. Such research constrains understandings of program design and its effects on and implications for sponsored students. Examples of underexplored ethical aspects of sponsorship arrangements are highlighted through examples and vignettes. Then, turning to contemporary discussions related to ethical internationalisation and student mobility, the paper asks which theoretical approaches could aid a focus upon and analysis of these programs in relation to ethics-related themes. Conventions theory (and specifically the orders of worth approach) is proposed as a useful theoretical lens. The paper then synthesises a novel framework using this approach to examine explicit and implicit aspects of sponsorship arrangements, explaining its suitability and potential to produce deeper insights into and more nuanced understanding of the consequences of modern scholarship program design for actors involved in sponsored international student mobility. In conclusion, the promise and significance of this framework utilizing the orders of worth approach for studying questions related to valuation processes and ethical internationalisation is recapitulated and future research is discussed.

Introduction

In a meeting room overlooking a lush hotel courtyard and swimming pool in Phnom Penh, Cambodia in early 2019, a representative from a large Swedish research university talks twenty-five prospective students through the strict application process for studies at his university and the separate government and university scholarship application processes that require roughly forty hours of diligent effort to successfully complete. As he talks, he reflects on the odds and imagines that two or three of these students might succeed at an award this year, or perhaps none. The seemingly dispassionate students pose questions – why doesn’t the Swedish embassy offer a computer room and help in applying, like other countries offering scholarship programs? They discuss the multiple applications they’ve completed and time and effort they dedicate to applying for degree studies and scholarship programs across multiple western countries, which they often do several years in a row. He begins to contemplate how many hours the average university student in Cambodia dedicates to these pursuits, and what those hours and efforts amount to for the many who never receive an award. The meeting concludes. As they trickle out into the evening, the students’ talk conveys a mix of earnest interest and palpable incredulity almost mistakeable for hope.

UN Sustainable Development Goal 4, target 4.b aimed to ‘substantially expand globally the number of scholarships available to developing countries … for enrolment in higher education’ raising the perceived importance of scholarships to new heights.Footnote1 Meanwhile, prominent universities around the world increasingly formalise their relationships with scholarship organisations (sometimes called sponsoring organisations/agencies) through memoranda of understanding (MOUs) and bilateral agreements. Sponsored students’ imputed importance for sustainable development has been met by an increase in academic literature focused on scholarship programs and sponsored students, representing an emerging sub-field in higher education (HE) research (Dassin, Marsh, and Mawer Citation2018). However this body of literature is still relatively slim. In parallel, at the intersection of university management and HE research, universities’ interest in the ‘ethics of internationalization’ or ‘ethical internationalism’ or even ‘responsible internationalization’ (Haapakoski Citation2020; Shih, Gaunt, and Östlund Citation2020; van Gaalen Citation2021; Waters and Brooks Citation2021; ‘EIHE, Publications’ Citation2013) has grown but has not focused on relationships with or practices within scholarship organisationsFootnote2 although international higher education scholars have voiced concerns around scholarship-related ethical issues (see de Wit Citation2016b). Thus, despite recent attention, our understanding of what scholarship programs entail and the impact they have is lacking in relation to important questions in today’s higher education landscape. Foremost amongst these are questions of ethics and efficacy, some of which are raised through vignettes that introduce three sections in this paper – in the vignette above, highlighting extreme valuation and in two that follow, touching on bonded return requirements, subject area restrictions, and contestations over quality of provision and the contract terms between universities and scholarship providers.

In order to explore these areas, this paper reviews recent literature on international scholarship programs for higher education, the policy aims behind these programs, their design, and their evaluation. It asks: what are the incentive structures, potential moral issues and other ethical dimensions of common scholarship program designs? And, how do scholarship programs holistically impact individual applicants and awarded scholars? It argues that the bulk of this literature takes as a given its subjects’ delineation of the phenomena being studied, and analysis is therefore circumscribed within the concepts defined by subject organisations and entities. While recent work has been helpful for broadening the discussion around scholarship program design and evaluation – both developing a base of empirical knowledge and a unique sub-field of HE research – critical questions related to ethical internationalisation remain unexplored. Therefore, the three questions guiding this paper’s contribution aim at bringing into relief the implications and effects of scholarships on sponsored students and other key actors. Two questions (above) set out a larger research agenda, while the following question guides the current paper: Which theoretical lenses can help us focus on and analyse scholarship programmes towards understanding their full effects and implications, rather than simply examining them instrumentally? So, while this paper aims to review ongoing scholarly discussions, its main contribution is to synthesise and introduce a framework better able to explore issues related to ethical internationalisation. This framework is focused on three main actors in sponsored mobility – universities, sponsored students and scholarship organisations – and analysing situations amongst them using the ‘orders of worth’ approach. This approach allows us to examine and illuminate contestations, justifications and larger valuation processes which transpire as the actors negotiate and navigate both explicit and implicit aspects of their relationships.

The above questions are important not least because existing literature tends to focus on awardees with positive outcomes, neglecting detrimental effects and negative outcomesFootnote3, typified by situations such as high-stakes study failure of sponsored students facing strict financial guarantor contracts (Perna, Orosz, and Jumakulov Citation2015); severe graduate re-integration challenges under bonded-return requirements (Teng Citation2014; Vanichakorn Citation2005); and accusations of student neglect against universities and entire HE systems (Honeywood Citation2016). Recently, Dassin, Marsh, and Mawer (Citation2018) have pointed out that much of this literature – in a mode of ‘evaluative’ analysis – is focused on a predetermined ‘beneficial arch’ or ‘idealised trajectory’ of study, improvement (either in human capital and/or in capabilities) and societal contribution. According to sponsoring organisations, this is the path that scholarship awardees follow (Dassin, Marsh, and Mawer Citation2018). Many studies highlight awardees who follow this trajectory and exclude other outcomes from examination.

Nevertheless, some studies do find evidence of problematic aspects in both process and outcome – issues such as elite capture (Dassin, Marsh, and Mawer Citation2018), reinforcement of post- or neo-colonial patterns (Chiappa and Finardi Citation2021; Ye Citation2021) negative trajectories (Mawer Citation2017) and incompatibilities between degree studied and the ability to apply knowledge and skills in the home country (Campbell Citation2018; Oketch, McCowan, and Schendel Citation2014; Pritchard Citation2011; Vanichakorn Citation2005). Yet, these areas receive relatively little attention or analysis overall. In addition, covenants, clauses that constrict awardees future choices and other contractual bonds between the scholarship organisation and awardee are mentioned in a number of studies (Campbell and Neff Citation2020; Perna, Orosz, and Jumakulov Citation2015) but are neither a focus of critical analysis nor thoroughly reflected upon in research, with some recent exceptions (Engberg et al. Citation2014; Mawer Citation2018).Footnote4 Beyond these phenomena, further issues exist such as disproportionate or extreme valuation, as highlighted in the opening vignette (which occurs when applicants see limited scholarship opportunities as so valuable that they forego other avenues / opportunities in order to seek awards) (see also Yang Citation2016) and misaligned incentivisation (when applicants forego their preferred subject area to study something within the frame of the scholarship program rules) (Teng Citation2014; Yang Citation2016). The vignette opening the ‘Ethical Approaches to ISM’ section of this paper touches on this problematic. Subject area limitations are underscored in the comprehensive 2014 survey conducted by Perna et al. which finds that ‘Very few programs (15%) permit recipients to study any academic specialty area.’ When considering programs focused on advanced knowledge acquisition, even lower percentages are found (Perna et al. Citation2014, 68). Additionally, mismatches between scholarship program aims and the provision of education at partnering universities have been documented (Grieco Citation2015; Honeywood Citation2016) and can impact scholars, their home countries, and their communities.

Those who argue that much international and comparative education research is theory-poor, too concentrated on practical matters, or tends to follow policy uncritically (see Ozga Citation2021; Tight Citation2004) may find evidence in much of the scholarship-focused literature reviewed here.

The article is structured as follows. It reviews the relevant scholarship program literature, providing an overview of the current state of the field. It then summarises the main theoretical concepts used in this body of literature, carefully considering their suitability for resolving the questions posed above. Turning to an introduction of the main threads in recent ‘ethical internationalisation’ literature, the paper draws attention to the need for a new theoretical approach that is able to consider the complex relationships between the principle actors involved in sponsored international student mobility (ISM). It then introduces a novel framework centred on these relationships and employing the ‘orders of worth’ (OW) approach, argued to represent a means for analysis of the contestations and ethical challenges in sponsored ISM. In conclusion, the significance of this approach in relation to ethical internationalisation is reiterated and future research is proposed.

Background

A literature review was conducted in three stages. First, a keyword search utilising three research database portals was undertaken using different permutations of keywords related to ISM and terms related to ‘scholarships’ ‘fellowships’ ‘bursaries’ and ‘sponsorships’. This was followed by iterative searches using previously unidentified keywords found in the initially reviewed literature, complemented by a systematic review of literature cited in these peer-reviewed articles and edited volumes. Finally, ‘grey’ literature accessed on relevant NGO and intergovernmental agencies’ websites was analysed. This review found a number of previous studies on international scholarship programs, often painstakingly and meticulously researched and yet largely descriptive (Bhandari and Mirza Citation2016; Johnson Citation2017; Perna, Orosz, and Jumakulov Citation2015) and/or referencing a narrow set of theories prescriptively employed in the very scholarship programs they study (Campbell Citation2017; Engberg et al. Citation2014; Perna et al. Citation2014).

Overarchingly, the literature shows that both justifications for and analysis of programs most frequently employ human capital theory (Cosentino et al. Citation2019; Grieco Citation2015; Perna et al. Citation2015) sometimes using broader definitions or ‘human resource development’ categorisations (Dassin, Marsh, and Mawer Citation2018; Perna et al. Citation2014). Another common justification for programs sponsored by countries in the global north is ‘soft power’ (Scott-Smith Citation2008; Trilokekar Citation2015; Wilson Citation2014),Footnote5 sometimes existing alongside or couched in human rights related language (Novotný et al. Citation2021). Soft power objectives can also exist alongside human capital aims in policy formulations. Capabilities theory (as highlighted by Campbell and Mawer Citation2019; Walker Citation2012) is another well-known theory frequently employed by NGOs and non-profit foundations to justify scholarship programs (Loerke Citation2018).

With some exceptions (Dassin, Marsh, and Mawer Citation2018; Mawer Citation2017; Scott-Smith Citation2008)Footnote6, recent studies are mainly mapping exercises or ‘evaluative’ approaches. These give scant attention to critical questions about program design, assumptions and impacts (intended and unintended) and focus mainly on examining the ‘effectiveness’ of the program vis-à-vis the internal logic employed by the program itself. One explanation for this, as Mawer points out, is that academic articles focused on scholarship programs are often produced adjacent to contracted evaluation studies which produce ‘grey’ literature (Citation2017).

In the following sub-sections, shortcomings of these program logics or theoretical justifications will be highlighted vis-à-vis this paper’s interest in rendering visible ethical aspects of scholarship program design, process and outcomes.

The impotence of human capital theory

Human capital theory (HCT) is an economic theory arising from and dependent upon a very specific set of ontological assumptions which emerged from a radically conservative political project in the USA during the latter half of the twentieth century (Blaug Citation1976; Davies Citation2015; Dellnäs Citation2002). Despite this lineage, the term ‘human capital’ has been adopted as a generic term used across many disciplines and is arguably dominant in those concerned with education and its value. In brief, the theory posits that educational investments by individualsFootnote7 reward the individual directly through higher productivity and then, on a classically conceived labour market, through commensurately higher wages. The theory collapses complex ideas about the value of education into a simple economic investment-return model which, although ideologically pure in a neoclassical economic sense, has proven to hold limited powers of explanation. Despite serious shortcomings and flaws, the widespread use of HCT across fields including public policy, journalism, and law (Fourcade-Gourinchas Citation2001) provides strong evidence of the pervasive influence of neoliberal economic reasoning as a hegemonic form of discourse in the modern era.

Many scholars argue HCT is a crude cudgel which is over/misused in analysing the effects of education. Diverse and firmly grounded arguments have been made by economists, educators, and sociologists amongst others. Some take a technical approach, examining HCT and finding cardinal flaws in its foundations and/or core assumptions – structures and premises which Simon Marginson recently argued ‘lack realism in at least four areas’ (Marginson Citation2019, 291; see also McCloskey Citation1989; Dellnäs Citation2002; Robeyns Citation2006; Tan Citation2014; Klees Citation2016). Others scrutinize the overarching philosophical and political project of the researchers who developed the theory at the University of Chicago and their ilk. They describe a political agenda distilled into a value-laden model that is essentially a misrepresentation of what education does. These authors go on to offer more nuanced and theoretically rich understandings of the economic consequences of education in relation to other societal factors (Davies Citation2015; Granovetter Citation1985; Citation1995). Other approaches highlight the lack of explanatory power that studies using HCT show vis-à-vis competing theories, or in long-term perspective (Bills Citation2003; Blaug Citation1976; Brown, Lauder, and Cheung Citation2020; Piketty and Goldhammer Citation2014).

Despite these failings, and evidence that the application of HCT has damaged HE systems (Heyneman Citation2012), its continued attractiveness stems from a promise to capture the value of education in an easily commensurable dollar figure. As explained by Will Davies, the primacy of economic commensurability is a main characteristic of neoliberalism today (Davies Citation2014) and carries both moral implications and reinforcement mechanisms, including an elitist discourse that together with other aspects of neoliberalism ‘tends to classify people who are affluent into a bounded community and to marginalise those with fewer economic resources.’ (Hall and Lamont Citation2013, 19).

HCT retains popularity in both policy and academic applications thanks to its place in neoliberal discourse, its prima facie simplicity, and a widespread lack of understanding of the unsound assumptions underlying the theory. Its reuse furthers the intellectually impoverished practise of reducing the complexities of ‘education’ into a one-dimensional investment-return model that distorts both the benefits of education and societal causes of inequality, while disregarding other established human value systems. Given its ‘collapsing’ effect,Footnote8 which ‘marginalizes the ethical dimensions of education’ (Bell Citation2020, 44), HCT is ineffectual in examining ethical aspects of scholarship program design.

Instrumentalism and ‘playing politics’

The soft power rationale found in the design of many international scholarship programs based in the global north has been common since the Cold War and was arguably present even in early international scholarship programs sponsored by the British Empire.Footnote9 Soft power comprises ‘the ability to manipulate others … through the attractiveness of culture and values rather than economic incentives or threats of force’ (Wilson Citation2014, 12). The soft power aims of the sponsoring state have a clear moral dimension which we can diagram as having at one extreme a ‘loyal servant’ ideal, similar to the aims of colonial powers and programs such as the early Rhodes scholarship (Pietsch Citation2016). The other end of the spectrum is epitomised by an independent critical thinker, able to see beyond the ontological and rhetorical baggage of their host country and its education system and choosing à la carte only knowledge useful to their own aims.Footnote10 Surveying such programs, soft power aims are often described in terms that suggest a noble political project (Nye Citation2004; Wilson Citation2014), but the colonial substructures that such arrangements harken back to are difficult to expunge.Footnote11 Given this, academics examining these programs could be expected to take a critical approach. Reviewing the literature, we instead find a dearth of critical perspectivesFootnote12, and this appears especially acute for scholars moving from policy or institutional worlds into the academy. This is evidenced in doctoral dissertations (Campbell Citation2016) and other publications in which the delineation of program logics and aims eclipse analysis (see for example see chapters in Tournès and Scott-Smith Citation2017) and we find largely descriptive language supporting or reflecting uncritically on the instrumental aims of soft-power actors. In some cases, despite making otherwise sound and insightful scholarly contributions, recommendations aim at maximising the impact of scholarship program alumni through ‘funding [which] could be concentrated in places and at specific moments when a certain country is particularly fertile for new leadership and ideas from abroad’ (Campbell Citation2016, 161). Despite the concerns such language engenders, the literature on the whole finds a notable lack of evidence for the efficacy of soft-power approaches (Åkerlund Citation2016; Scott-Smith Citation2008; Wilson Citation2014).

Capabilities approach – preferable?

Amartya Sen’s capabilities approach was developed in opposition to the human capital paradigm, which he had long opposed (Sen Citation1977). It was birthed from a critical stance against mainstream development economics’ models focused on utility and economic growth objectives. Conceived as a holistic and human-centred way of understanding the role of development in alleviating poverty, the approach takes a normative stance in relation to what it terms ‘human flourishing’ and the capability to live a full life. It aims to put this at the centre of development endeavours, in both design and evaluation. There is an instrumental aspect to the approach, but tempered by a focus on the needs of individuals and an inclusive agenda that (in theory) avoids defining these needs through a dominant theoretical lens (Robeyns Citation2006).

The popularity of Sen’s approach, its expansion (Nussbaum Citation2000) and operationalisation (Alkire Citation2002) for the international development sector have led to its widespread use, including in educational program design. Its popularity in scholarship program design is apparent in the literature where we find suggestions to add the approach to various programs that do not utilise it (For example, see Campbell and Mawer Citation2019; Novotný et al. Citation2021; Waluyo, Eng, and Wiseman Citation2019). This approach (as theorised) is less morally problematic than human capital and soft power approaches – its design ostensibly eschews using grantees as instruments of the grantor’s agenda.

The approach offers a refined and multifaceted understanding of human development and agency, but is outcome oriented rather than process oriented, and therefore is not ideal for evaluating contestations, conflicts or ethical issues present in process.Footnote13 Put differently, the capabilities approach as operationalised focuses on defining key capabilities and dimensions of poverty, intervening, and measuring change. Considerable work has been done towards methods for defining these factors (Alkire Citation2013). However, such methods cannot serve to answer this paper’s central questions around ethics and efficacy.

Ethical approaches to ISM

In a well-publicised and widely debated case in Singapore, a student completed her biomedical studies through government granted scholarships – first at Cambridge University, then Karolinska Institute in Sweden for doctoral studies. She studied fully aware that Singapore has extremely rigid rules targeted at bringing back specific categories of ‘human capital’, enshrined in the contracts that she signed. Yet, at some point during her studies, existing interests in dance and performance art eclipsed her interest in biomedicine. She finished her PhD and was bound by the terms of her scholarship either pay back the entire costs of her studies or work for the Singaporean government for six years. In 2014, after speaking out about her situation and a job ‘not aligned with her interests’ and seeking to transfer her employment into the arts sector, she came under widespread criticism from the Singaporean public and media. In a storm of criticism, she relented to the terms of her bond and employment, but decided to create her own scheme to fund young performance artists with small grants (1000 SGD) for pursuing their own works, paid from her government salary. Today, years later, she is free of her bond and a working performance artist in Germany who recently completed an MA degree in Choreography and Performance. (Er Citationn.d.; Lee Citation2015; Teng Citation2014)

A point of departure for developing this framework is found at the nexus of various ‘ethical internationalisation’ discussions currently taking place at several levels and loci of the HE sector today. Some discussions have centred on ethical aspects of university partnerships and international research collaborations.Footnote15 Others have focused on approaches to the internationalisation of HE in general and related ethical implications (de Wit Citation2016a; Haapakoski Citation2020; Pashby and Andreotti Citation2016; Stein Citation2016; Stein and Andreotti Citation2016; Waters and Brooks Citation2021; Yang Citation2016) or specific ethical practices that universities and teachers could or should adopt towards international students on their campuses – related to rethinking student services, ‘academic hospitality’, pedagogy and course design in light of postcolonial / anti-racist discourses and the exigent problems rendered visible through related research and dialogue (Andreotti Citation2011; Hayes, Lomer, and Taha Citation2022; Madge, Raghuram, and Noxolo Citation2009; Mittelmeier et al. Citation2022; Ploner Citation2018). We see recent crossover between the first two threads in Sweden, where the discussions around ‘Responsible internationalization’ (Shih, Gaunt, and Östlund Citation2020), initially focused on ethical and security issues around university partnerships, have branched into concerns about specific clauses in the contracts between funded students and their home government sponsors.Footnote16

In a recent article, Yang (Citation2020) highlighted and developed this conversation and asserted a need to look more candidly at a range of ethical issues in ISM:

Of late, an interest in the ethics and politics of ISM seems to be emerging, as more scholars begin to consider critically questions about rights, responsibility, justice, equality, and so forth that inhere in the thorny relationships between ISM stakeholders. (Yang Citation2020, 518)

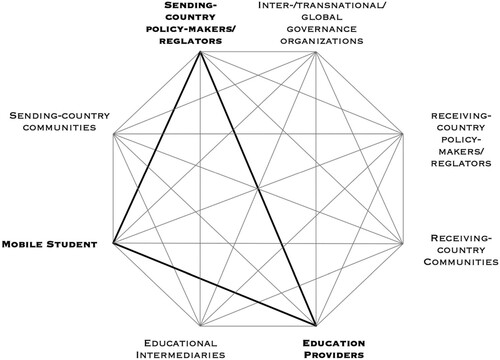

Figure 1. Key actors in ISM (adapted from Yang Citation2020).

Justifying an orders of worth approach

Inspired by these conversations and developments in the scholarships literature, this paper aims to make a contribution to the study of scholarship programs and sponsored students by employing Yang’s conceptualisation of the key actors in ISM and delineating the scholar (internationally mobile sponsored student), the Education Provider (university) and the Sending-country policy maker/Regulator (scholarship organisation) as the primary actors in focus (see ) in research on sponsored students funded by their home countries (or, receiving-country policy makers for inbound mobility programs). To allow us to examine aspects of these relationships which may otherwise remain inscrutable, a novel theoretical approach is introduced below.

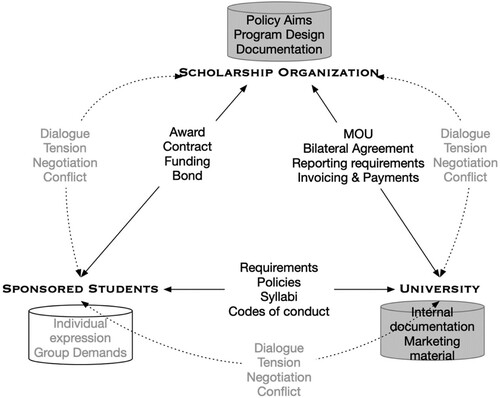

Figure 2. Key actors in sponsored ISM: explicit and implicit interactions; visible and obscured values.

Putting these three actors in sharp focus and treating scholarship awardees and scholarship-driven mobility separately from other ISM is justified due to the unique relationships these students are engaged in, with the scholarship agency representing a third actor of significant importance. As reflected in the literature, this trilateral relationship and its implicit and explicit components () contribute to the specific issues sponsored students face, ethical quandaries they deal with and distinct paths they follow (Dassin, Marsh, and Mawer Citation2018; Tournès and Scott-Smith Citation2017).

As the literature review reveals, and additional empirical examples presented through the vignettes illustrate, these relationships are not as straight-forward or neatly aligned as the official documentation from scholarship agencies (and their written agreements with scholars and universities) would suggest.

Theoretical framework

The theoretical framework introduced here takes Yang’s typology, refocuses it on the three actors in and implicit and explicit aspects of their relationships, and adds analytical tools borrowed from economic sociology, synthesising a new approach. As illustrates, many aspects of the framework’s primary relationships are explicit – policies, contracts and other official documents. These are openly articulated; acknowledged but underexamined in the scholarships literature. Other aspects are implicit – the tensions, negotiations and conflicts between actors – and generally unexamined. All aspects have relevance to our understanding of ethical internationalisation in sponsored ISM.

This new approach does not exclude the possibility of examining relationships between the full range of Yang’s actors. In future research, this approach could be fruitfully extended to relationships with sending-country communities, educational intermediaries, receiving-country communities, and inter-/transnational/global governance organisations. Here, through focusing on three main actors, we unpack the primary relationships to better understand the ethical dimensions and implications that are created through scholarship program policies and activities. Yang highlights key questions around rights, responsibilities, values, justice, and equality and the ‘intertwinement between ethics and politics’ (Citation2020, 519). To explore this intertwinement and the actors’ positionings, we are focused here on questions of value. Exploring the ways in which the education itself is valued by the actors allows us to understand how they position themselves pragmatically ‘in relationship to axiological principals’ (Heinich Citation2020, 21), i.e. to understand if their ways of valuing irreducibly differ. In , processes of valuation evidenced explicitly in texts and empirical materials are indicated by black typeface. Implicit processes and contestations involved in valuation are illustrated by light grey typeface.

As argued above, while HCT currently dominates discussions of value in HE, a more sophisticated toolset for exploring valuation processes is called for. In the literature, both Waters and Brooks (Citation2021) and Barker (Citation2022) have recently treated value as a part of their study of ISM, with Barker’s study focused on an international scholarship program funded by the Australian government. These studies draw on HCT but also utilise Bourdieusian concepts of social and cultural capital, which have proven popular in several traditions in HE research. However, these authors neglect a more recent approach which is built around a multifaceted view of value and was developed specifically to avoid the cultural determinism and overly general conceptualisation of capital forms argued to be inherent in Bourdieu’s approach (Lamont Citation2018; Thévenot and Jagd Citation2004). Such features prove especially problematic in cross-cultural examinations (Lamont Citation2018). Considering this, a significant refinement could be achieved through instead employing the orders of worth (OW) approach, situated within convention theory (CT) in the field of economic sociology.

In their work, originally published in French, and in English in 2006 as On Justification: The Economies of Worth, Luc Boltanski and Laurent Thévenot conceptualised a pragmatic model which describes both a ‘theory of justice’ and a ‘capability’ necessary for understanding social criticism, conflict and agreement processes, at the intersection of their respective disciplines, sociology and economics. They initially identified six ‘orders of worth’, each representing a world with its own coherent and unique logic for evaluating and justifying assignments of worth (Boltanski and Thévenot Citation2006). They went on to describe how situations of uncertainty are important for examining the justifications and contestations actors make around worthiness, and connected moral and ethical questions (Thévenot Citation2022; Ye Citation2021).

Although explaining a complex framework such as OW concisely poses challenges, it provides an approach for understanding how groups deliberate when their ways of valuing differ and explains how observers, through delineating the ways in which groups publicly justify their positions and make moral arguments, can analyse value structures’ relationships to one another and to the ‘greater good’.

The six initial worlds of worth that Boltanski and Thévenot identified and defined are a key to their model, with its potential to more accurately represent how humans construct value and valorise. They defined a market world (which measures worth using money) but they also defined an industrial world (which uses productivity, efficiency and skill to define worth). There is also the inspired world (where creativity and uniqueness are the measures of worth), the world of fame (popularity and recognition by large numbers of individuals), the civic world (using concepts like freedom, representation and solidarity as related to collectives) and finally a domestic world (defining worth using concepts including tradition, honour, esteem, reputation, caring and responsibility).

The worlds of worth are not exhaustive – other worlds can and have been identified by the original authors and others. For example, ‘Green’ and ‘Project’ worlds have also been identified and widely accepted (Boltanski and Chiapello Citation2018; Lafaye and Thévenot Citation2017).

Thévenot & Boltanski’s initial construction of these worlds (rigorously referenced against key philosophical texts) and the approach’s openness represent a rich, flexible framework for understanding how value is constructed. In the years since its introduction, the approach has proven useful to scholars seeking insights into processes, social relations and organisations that move beyond neoclassical theories of economic value or categorical classifications of ‘capital’ types. Here, OW has promise as a sophisticated, modern solution for the pervasive and problematic prescriptions of HCT.

Notably, in the original formulation of OW and the many empirical examples describing how these play out in society, there is relatively little focus on education as an arena. Boltanski and Thévenot discuss schools and their educational activities existing in a compromise between the domestic world and the civic world (Citation2006, 310). They further discuss higher education degrees as a form of civic-industrial compromise (p.330). However, both of these situations are drawn from a rather static description of schools’ domestic position in France, one which sees education’s role as a public good and university diplomas as a certification of skills in an uncontested setting or as ‘figures of compromise’ (Boltanski and Thévenot Citation2006). David Stark provided one early explication of how OW could be applied in higher education (Stark et al. Citation2009) but applications to HE were not a major focus of early work utilising the approach.

Suitability of the approach

The situation of higher education today is significantly more complex, penetrated and problematised than that which Boltanski and Thévenot described in their original work, and values in HE are highly contested rather than in a state of compromise (Altbach Citation2002; Bleiklie, Enders, and Lepori Citation2015; Krause-Jensen and Garsten Citation2014; Marginson Citation2006).Footnote17 Therefore, it is not surprising to find recent examples in the literature of OW frameworks applied to universities and ISM. Examples most closely related to this paper’s interests would concern the relationships diagrammed in . Rebecca Ye’s Citation2021 paper is highly relevant here as an exploratory work using OW to examine how students’ home countries and elite universities abroad justified their roles as senders/recievers in situations of uncertainty during the COVID-19 pandemic (Ye Citation2021). We also find studies examining specific aspects of universities’ interface with other outside actors (Mailhot and Langley Citation2017) as well as scrutinising the articulation of moral principles during university mergers (Kohvakka Citation2021) and academics responses to evaluative publishing metrics (Haddow and Hammarfelt Citation2019). Relationships between public universities and the governments they are dependent upon have also been explored using this framework (Eyraud Citation2022; Schneijderberg Citation2020). Many of these studies examine what Søren Jagd, in his analysis of studies using OW frameworks has classified as ‘interorganizational co-operation and competing orders of worth’ (Jagd Citation2011).

However, the approach has not been widely used to investigate students’ valuation processes. A study examining justifications for cheating amongst Russian students was published in 2021 (Dremova et al. Citation2021). More pertinently, researchers interviewed students and teachers in a master’s program delivered as commissioned education in Indonesia by Finnish universities (contracted by an Indonesian organisation) to examine quality of education from a CT / OW perspective. They found this approach helped illuminate contradictions in valuations of ‘quality’ which went far beyond a ‘market’ understanding of worth (Juusola and Räihä Citation2020). Instead, they found multiple orders of worth constructed and under contestation by students and teachers, which helped them analyse what was valuable to different actors vis-à-vis the notion of ‘quality’. Although not focused on contestation, this study, like Ye’s paper, informs the approach outlined here as it takes valuation seriously as part of a methodologically sound examination into how educational quality is perceived in a situation similar to sponsored ISM, although where staff is mobile instead of students.

Given this assortment of studies in HEFootnote18, the further development of a framework based on OW to examine the values of and relationships between scholarship agencies, universities and applicants/awardees/alumni, especially during critical moments, will help researchers interested in the ethical dimensions of sponsored ISM understand conflict and contestation via examination of actors’ valuation processes and the ways these interact. Such analysis offers the possibility of moving beyond evaluative examinations such as those derived from ‘human capital’ concepts (Davies Citation2015).

In order to effectively employ such a framework, the contestations, negotiations, and legitimisation of settlements (Reinecke, van Bommel, and Spicer Citation2017) being studied should go beyond ‘private arrangements’ (Boltanski and Thévenot Citation2006) – i.e. contestation should take place openly. Through public documents, newspaper articles and political debate, there is ample material documenting justifications and arguments that universities and scholarship organisations use. Rebecca Ye’s Citation2021 article highlights examples of this. The vignette that opens the following section offers another example.

The gap in empirics is with groups of sponsored students, as the contestations or justifications they make are not frequently documented in fully public settings (represented in ). These may be generated within student organisations, unions, and associations. Their contestations may, as Anne Campbell suggests, appear where agency and conditionality collide (Citation2018). They may be expressed via dialogue with universities and scholarship organisations in venues and via channels that are neither systematically documented nor widely publicised – for example, events bringing these actors together Footnote19 – in manifestations of what Tran and Vu (Citation2018) term ‘collective agency for contestation'.Footnote20 As Rebecca Ye highlights in her article on justifications during the COVID-19 pandemic, logistical arrangements, justifications and moral concerns on university campuses during the pandemic resulted in public statements from student groups (Ye Citation2021) in reaction to pandemic-era policies. In several cases, these statements were widely publicised.Footnote21 This exceptional example of attention to students’ circumstances in relation to university policies highlights contestations that student groups constantly engage in, but often go unnoticed.

Additionally, we see that arrangements between these main actors (see ) seek a ‘broad scope’ of legitimacy and fit the archetype of organisational arrangements that ‘need to appeal to the common good of multiple audiences’ which, according to Reinecke, van Bommel, and Spicer (Citation2017) is a qualification for situations that can be examined using an OW framework. In our case, possible audiences could be any of those that Yang highlights (see ) including our main actors as well as sending or receiving country communities, and inter-/transnational/global governance organisations (Yang Citation2020). An example of such a situation is represented by the Singaporean vignette opening this section of the paper – a highly public conflict which tested moral legitimacy and conceptions of the common good in a contentious encounter between the scholarship recipient, sponsoring government, and sending-country community.

This paper therefore argues that an empirical exploration of the positions, contestations, and justifications of groups of sponsored students using an OW framework will allow us to understand and reflect on the relationships of key actors, ethical quandaries and questions of efficacy, and importantly – to perform this examination independent of a specific scholarship program’s theoretical design or structure. The operationalisation of such a framework would represent a clear contribution to the field of HE research. By rendering visible contestation, negotiation and justification in processes of valuation, it will allow for reflection on persistent understandings and assumptions around international scholarship programs, allowing us to re-examine what is being offered and received, understand what is at stake, and perhaps gain a glimpse of future alternatives.

Discussion and conclusions

At a Australian conference on higher education internationalisation in 2016, a representative of the Saudi government shocked attendees as he presented his government’s new position on funded students. As ‘sponsored student specialists’ from leading Australian universities asked questions, a list of complaints against their higher education system rolled off the Saudi representative’s tongue, highlighting the gap in understanding between the Saudi attaché and the Australian administrators, through detailing perceived failings at Australian universities vis-à-vis the Saudi government’s sponsored students. His comments, announcing a virtual halt of sponsored mobilities to Australia, struck squarely at points of potential embarrassment for Australian educators and politicians alike. (Honeywood Citation2016)

The importance of developing a multidimensional framework is highlighted by the shortcomings of commonly employed instrumental approaches such as HCT, and the lack of insights such frameworks offer in relation to important questions and issues concerning all actors involved in sponsored ISM. The three vignettes presented in the paper underscore just a few of the issues – related to extreme valuation, bonded return requirements, subject area restrictions, and untested or misunderstood issues around quality of provision and fulfilment of contract terms that can lead to conflicts between students, high-profile organisations and other actors, including nation states. Using current approaches to understanding scholarship programs, the Cambodian case would likely go ignored or be viewed instrumentally rather than unpacked; the Singaporean case discussed only through a dominant HCT lens, and the Australian case viewed as a trade conflict, ‘loss in revenue’ or perhaps ‘soft power’ concern, ignoring significant questions around ethics by allowing a ‘market’ view on the provision of HE to persist undisturbed.

It is argued that frameworks using conventions theory and ‘orders of worth’ theorisations will allow greater discernment around these issues. As Tine Hanrieder has stated, OW ‘provide tools for moral evaluation and the justification of hierarchy’ (Hanrieder Citation2016, 390). Such tools are sorely needed in today’s higher education landscape where relationships are increasingly complex and interwoven and the stakes are high for all actors involved. Foremost amongst these actors are the students themselves. As Michelle Lamont posits, ‘With growing income inequality and the trend toward a 'winner-take-all society' (Frank Citation1995), understanding the dynamics that work in favour of, and against, the existence of multiple hierarchies of worth or systems of evaluation is more urgent than ever’ (Lamont Citation2012, 202).

Operationalising the theoretical approach synthesized above involves complexities. As discussed, instances of contestation and justification between students and other actors may occur in unnoticed and underpublicised venues; valuation processes are partly hidden. Therefore, undertaking empirical work may present challenges, but of a kind not unfamiliar to qualitative researchers.

This framework will yield important insights into ethical conundrums and valuation puzzles representing potential problem areas and incongruities in scholarship program design. Such an approach applied to single cases or comparative studies around national scholarship programs for ISM and their awardees, and research focused on other relationships – for example, focused on scholarship agencies and global governance organisations – will contribute to an emerging body of research critically exploring the role of scholarship organisations in an era of ethical internationalisation.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1 This specific target had a 2020 target date with the selected indicator for 4.b being “Volume of official development assistance flows for scholarships” which excludes private actors and developing countries’ own scholarship expenditures from internally funded programs, endowment funds, etc. (See http://uis.unesco.org/en/glossary-term/volume-official-development-assistance-flows-scholarships-sector-and-type-study and Bhandari and Mirza Citation2016).

2 And specifically, their effect on students. A recent exception is Sweden, and this is elaborated on in the section 'Ethical approaches to ISM'.

3 A phenomenon mirrored in practice.

4 Currently, such contracts are being more closely examined and discussed by some universities due to potential ethical issues they raise.

5 When political science literature discusses scholarships, this is the primary understanding used. (Nye Citation2004; Wilson Citation2015)

6 Matt Mawer’s Citation2017 paper is also a mapping exercise, but it maps the evaluative approaches themselves, and in doing so, points out some shortcomings and possible remedies. Nevertheless, the study is aimed squarely at improving evaluation rather than critically examining conventional theoretical understandings.

7 Who in this model are always rational and utility-optimising actors.

8 Whereby diverse ways of valuing education are interred by economic reasoning and only a dollar value remains visible.

9 The “softness” of such programs would seem disputable when their imputed aim was to create loyal servants of the empire.

10 Other experiences which complicate this dichotomy include alienation, failure, and the possibility of manipulating the system from within to one’s own aims (see chapter 8 in Pietsch for a discussion as well as Mukherjee Citation2011).

11 The language used in “grey” literature provides frequent examples of such a lineage.

12 However, see Scott-Smith Citation2008 as one critical example.

13 In Sen’s formulation, the approach is concerned with process (i.e., it rejects act-consequentialism) but is not dependent upon a specific process of valuation. In application, processes and methods have varied greatly. A process-focused inquiry utilizing orders of worth could perhaps be employed within the capabilities approach.

14 See Koh (Citation2012) and Ye and Nylander (Citation2023) for details of Singaporean scholarship programs’ HCT underpinnings.

15 Evidenced by updated policies around partnerships found on several European universities’ websites or those of related umbrella organisations. See, for example, Karolinska Institutet’s guidance (Gaunt Citation2022), Allea (Citation2017), and The Magna Charta Observatory (Citation2020).

16 These discussions contributed to changes in at least one Swedish university’s admissions regulations for sponsored doctoral students (Lund University, STYR 2021/2700), and reached the mainstream media in Sweden with several newspapers featuring stories on the differing policies towards scholarship-funded research students across Swedish Universities (Hjalmarsson Citation2023; Nilsson and Sadikovic Citation2023).

17 Indeed the French case today also appears significantly different from that which they describe in the 1990s when their seminal work was originally published in France (van Zanten Citation2019)

18 And works such as a recent handbook chapter on education and conventions, published at the time of writing (Imdorf and Leemann Citation2023) which further supports my approach.

19 An example of an event in this vein, held in 2016, was documented by the Indonesian Embassy in Stockholm and the Indonesian Student Association (PPI Swedia Citation2016).

20 One of four forms of “agency in mobility” they theorise around internationally mobile students.

21 See numerous articles in The Guardian such as (R. Hall and Quinn Citation2020), BBC.com, etc.

References

- Åkerlund, Andreas. 2016. Public Diplomacy and Academic Mobility in Sweden: The Swedish Institute and Scholarship Programs for Foreign Academics, 1938-2010. Lund: Nordic Academic Press.

- Alkire, Sabina. 2002. Valuing Freedoms. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Alkire, Sabina. 2013. “Choosing Dimensions: The Capability Approach and Multidimensional Poverty.” In The Many Dimensions of Poverty, edited by Nanak Kakwani, and Jacques Silber, 89–119. London: Palgrave Macmillan UK.

- Allea. 2017. “The European Code of Conduct for Research Integrity.” The European Federation of Academies of Sciences and Humanities. 2017. https://allea.org/code-of-conduct/.

- Altbach, Philip G. 2002. “Knowledge and Education as International Commodities: The Collapse of the Common Good.” International Higher Education 28: 2–5.

- Andreotti, Vanessa. 2011. Actionable Postcolonial Theory in Education. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Barker, Joanne Susan. 2022. “A Trying Endeavour: A Case Study of Value and Evaluation in an International Scholarship Program.” Doctoral Thesis - Monograph, Melbourne, RMIT.

- Bell, Leslie A. 2020. “Education Policy: Development and Enactment—The Case of Human Capital.” In Handbook of Education Policy Studies, edited by Guorui Fan, and Thomas S. Popkewitz, 31–51. Singapore: Springer Singapore.

- Bhandari, Rajika, and Zehra Mirza. 2016. “Scholarships for Students from Developing Countries: Establishing a Global Baseline.” ED/GEMR/MRT/2016/P1/11. UNESCO. https://unesdoc.unesco.org/ark:/48223/pf0000245571.

- Bills, David B. 2003. “Credentials, Signals, and Screens: Explaining the Relationship Between Schooling and Job Assignment.” Review of Educational Research 73 (4): 441–69. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543073004441.

- Blaug, Mark. 1976. “The Empirical Status of Human Capital Theory: A Slightly Jaundiced Survey.” Journal of Economic Literature 14 (3): 827–55.

- Bleiklie, Ivar, Jürgen Enders, and Benedetto Lepori. 2015. “Organizations as Penetrated Hierarchies: Environmental Pressures and Control in Professional Organizations.” Organization Studies 36 (7): 873–896. https://doi.org/10.1177/0170840615571960.

- Boltanski, Luc, and Eve Chiapello. 2018. The New Spirit of Capitalism. New updated edition, translated by Gregory Elliott. London; New York: Verso.

- Boltanski, Luc, and Laurent Thévenot. 2006. On Justification: Economies of Worth. Princeton: Princeton University Press

- Brown, Phillip, Hugh Lauder, and Sin Yi Cheung. 2020. The Death of Human Capital: Its Failed Promise and How to Renew It. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Campbell, Anne C. 2016. “International Scholarship Programs and Home Country Economic and Social Development: Comparing Georgian and Moldovan Alumni Experiences of ‘Giving Back.’” PhD Diss., USA: University of Minnesota.

- Campbell, Anne C. 2017. “How International Scholarship Recipients Perceive Their Contributions to the Development of Their Home Countries: Findings from a Comparative Study of Georgia and Moldova.” International Journal of Educational Development 55: 56–62. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2017.05.004.

- Campbell, Anne C. 2018. “Influencing Pathways to Social Change: Scholarship Program Conditionality and Individual Agency.” In International Scholarships in Higher Education, edited by Joan R. Dassin, Robin R. Marsh, and Matt Mawer, 165–186. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Campbell, Anne C., and Matt Mawer. 2019. “Clarifying Mixed Messages: International Scholarship Programmes in the Sustainable Development Agenda.” Higher Education Policy 32 (2): 167–84. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41307-017-0077-1.

- Campbell, Anne C., and Emelye Neff. 2020. “A Systematic Review of International Higher Education Scholarships for Students from the Global South.” Review of Educational Research 90 (6): 824–61. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654320947783.

- Charta Observatory, Magna. 2020. “Living Values.” Observatory Magna Charta Universitatum. 2020. https://www.magna-charta.org/activities-and-projects/living-values.

- Chiappa, Roxana, and Kyria Rebeca Finardi. 2021. “Coloniality Prints in Internationalization of Higher Education: The Case of Brazilian and Chilean International Scholarships.” Scholarship of Teaching and Learning in the South 26–45.

- Cosentino, Clemencia, Jane Fortson, Sarah Liuzzi, Anthony Harris, and Randall Blair. 2019. “Can Scholarships Provide Equitable Access to High-Quality University Education? Evidence from the Mastercard Foundation Scholars Program.” International Journal of Educational Development 71: 102089. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2019.102089.

- Dassin, Joan R., Robin R. Marsh, and Matt Mawer2018. International Scholarships in Higher Education. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Davies, William. 2014. In The Limits of Neoliberalism: Authority, Sovereignty and the Logic of Competition. London, United Kingdom: SAGE Publications Ltd.

- Davies, William. 2015. “The Return of Social Government.” European Journal of Social Theory 20: 432–450.

- Dellnäs, Ann-Christine. 2002. “Om Ekonomisk Imperialism : En Studie Av Gary S Beckers Idéer Om Humankapital, Familj Och Kriminalitet.” Doctoral Thesis - Monograph, Göteborg: University of Gothenburg. https://gupea.ub.gu.se/handle/2077/15607?show=full.

- de Wit, Hans. 2016a. “Internationalisation Should Be Ethical and for All.” University World News (Blog). July 15, 2016. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20160712085821857.

- de Wit, Hans. 2016b. “Ethical Internationalisation for All Is Not Impossible.” University World News (Blog). October 7, 2016. https://www.universityworldnews.com/post.php?story=20161007131130206.

- Dremova, Oksana, Natalia Maloshonok, Evgeniy Terentev, and Denis Federiakin. 2021. “Criticism and Justification of Undergraduate Academic Dishonesty: Development and Validation of the Domestic, Market and Industrial Orders of Worth Scales.” European Journal of Higher Education 13 (1): 44–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2021.1987287.

- “EIHE, Publications.”. 2013. Ethical Internationalism in Higher Education Research Project (Blog). May 1, 2013. http://eihe.blogspot.com/p/publications.html.

- Engberg, David, Gregg Glover, Laura E. Rumbley, and Philip G. Altbach. 2014. “The Rationale for Sponsoring Students to Undertake International Study: An Assessment of National Student Mobility Scholarship Programmes.” British Council & DAAD. https://www.britishcouncil.org/education/he-science/knowledge-centre/student-mobility/rationale-sponsoring-international-study.

- Er, Eng Kai. n.d. “About.” Personal Blog. KAIFISHFISH IS NOT A FISH. (blog). https://kaifishfish.tumblr.com/0about.

- Eyraud, Corine. 2022. “Archaeology of a Quantification Device: Quantification, Policies and Politics in French Higher Education.” In The New Politics of Numbers: Utopia, Evidence and Democracy, edited by Andrea Mennicken, and Robert Salais, 275–303. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Fourcade-Gourinchas, Marion. 2001. “Politics, Institutional Structures, and the Rise of Economics: A Comparative Study.” Theory and Society 30 (3): 397–447. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1017952519266.

- Frank, R. A. 1995. Winner-Take-All Society. New York: Free Press.

- Gaunt, Albin. 2022. “Resources for Responsible Internationalisation.” University Website. Karolinska Institutet. December 20, 2022. https://staff.ki.se/resources-for-responsible-internationalisation.

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1985. “Economic Action and Social Structure: The Problem of Embeddedness.” American Journal of Sociology 91 (3): 481–510.

- Granovetter, Mark S. 1995. Getting a Job: A Study of Contacts and Careers. 2nd ed. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

- Grieco, Julieta A. 2015. “Fostering Cross-Border Learning and Engagement Through Study Abroad Scholarships: Lessons from Brazil’s Science Without Borders Program.” Master’s Thesis, University of Toronto.

- Haapakoski, Jani. 2020. “Market Exclusions and False Inclusions. Mapping Obstacles for More Ethical Approaches in the Internationalization of Higher Education.” PhD Diss., University of Oulu.

- Haddow, Gaby, and Björn Hammarfelt. 2019. “Early Career Academics and Evaluative Metrics: Ambivalence, Resistance and Strategies.” In The Social Structures of Global Academia, edited by Fabian Cannizzo, and Nick Osbaldiston, 125–143. Oxford: Routledge.

- Hall, Peter A., and Michèle Lamont. 2013. “Introduction: Social Resilience in the Neoliberal Era.” In Social Resilience in the Neoliberal Era, edited by Michèle Lamont, and Peter A. Hall, 1–32. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Hall, Rachel, and Ben Quinn. 2020. “England Campus Lockdowns Creating ‘Perfect Storm’ for Stressed Students.” The Guardian UK, November 6, 2020. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2020/nov/06/england-campus-lockdowns-perfect-storm-students-mental-health-covid-restrictions.

- Hanrieder, Tine. 2016. “Orders of Worth and the Moral Conceptions of Health in Global Politics.” International Theory 8 (3): 390–421. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1752971916000099.

- Hayes, Aneta, Sylvie Lomer, and Sophia Hayat Taha. 2022. “Epistemological Process Towards Decolonial Praxis and Epistemic Inequality of an International Student.” Educational Review [Online Ahead of Print]: 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2022.2115463.

- Heinich, Nathalie. 2020. “A Pragmatic Redefinition of Value(s): Toward a General Model of Valuation.” Theory, Culture & Society 37 (5): 75–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276420915993.

- Heyneman, Stephen P. 2012. “When Models Become Monopolies: The Making of Education Policy at the World Bank.” In Education Strategy in the Developing World: Revising the World Bank’s Education Policy, edited by Christopher S. Collins, and Alexander W. Wiseman, 16:43–62. Leeds: International Perspectives on Education and Society. Emerald Group Publishing Limited.

- Hjalmarsson, Sanna. 2023. “Universitetet sätter stopp för kinesiska studenter.” Sydsvenskan, January 13, 2023, sec. Lund.

- Honeywood, Phil. 2016. “Lessons Abound as Two Overseas Government Outbound Mobility Programs Shudder to a Halt.” The Australian, April 13, 2016. 1780200117. Global Newsstream.

- Imdorf, Christian, and Regula Julia Leemann. 2023. “Education and Conventions.” In In Handbook of Economics and Sociology of Conventions, edited by Rainer Diaz-Bone, and Guillemette de Larquier, 1–33. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Jagd, Søren. 2011. “Pragmatic Sociology and Competing Orders of Worth in Organizations.” European Journal of Social Theory 14 (3): 343–59. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368431011412349.

- Johnson, Lonnie R. 2017. “The Fulbright Program and the Philosophy and Geography of US Exchange Programs Since World War II.” In Global Exchanges: Scholarships and Transnational Circulations in the Modern World, 1st ed, edited by Ludovic Tournès, and Giles Scott-Smith, 173–187. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Juusola, Henna, and Pekka Räihä. 2020. “Quality Conventions in the Exported Finnish Master’s Degree Programme in Teacher Education in Indonesia.” Higher Education 79 (4): 675–90. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00430-3.

- Klees, Steven J. 2016. “Human Capital and Rates of Return: Brilliant Ideas or Ideological Dead Ends?” Comparative Education Review 60 (4): 644–72. https://doi.org/10.1086/688063.

- Koh, Aaron. 2012. “Tactics of Interventions: Student Mobility and Human Capital Building in Singapore.” Higher Education Policy 25 (2): 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1057/hep.2012.5.

- Kohvakka, Mikko. 2021. “Justification Work in a University Merger: The Case of the University of Eastern Finland.” European Journal of Higher Education 11 (2): 197–215. https://doi.org/10.1080/21568235.2020.1870517.

- Krause-Jensen, Jakob, and Christina Garsten. 2014. “Neoliberal Turns in Higher Education.” Learning and Teaching 7 (3): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3167/latiss.2014.070301.

- Lafaye, Claudette, and Laurent Thévenot. 2017. “An Ecological Justification? Conflicts in the Development of Nature.” In Research in the Sociology of Organizations, edited by Charlotte Cloutier, Jean-Pascal Gond, and Bernard Leca, 52:273–300. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Lamont, Michèle. 2012. “Toward a Comparative Sociology of Valuation and Evaluation.” Annual Review of Sociology 38 (1): 201–21. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-soc-070308-120022.

- Lamont, Michèle. 2018. “The World Is Not a Field – An Interview with Michèle Lamont.” Sociologisk Forskning 56 (2): 167–179. https://www.diva-portal.org/smash/get/diva2:1330747/FULLTEXT01.pdf.

- Lee, Pearl. 2015. “A*Star Scientist Stops Accepting Applicants After Giving out ‘No Star Arts Grant’ to 5 Recipients.” The Straits Times, February 24, 2015, Web Edition edition, sec. Education. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/astar-scientist-stops-accepting-applicants-after-giving-out-no-star-arts-grant-to-5.

- Loerke, Martha. 2018. “What’s Next? Facilitating Post-Study Transitions.” In International Scholarships in Higher Education, edited by Joan R. Dassin, Robin R. Marsh, and Matt Mawer, 187–207. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Lund University, University Board. 2022. Antagningsordning för utbildning på forskarnivå vid Lunds universitet. STYR 2021/2700.

- Madge, Clare, Parvati Raghuram, and Patricia Noxolo. 2009. “Engaged Pedagogy and Responsibility: A Postcolonial Analysis of International Students.” Geoforum; Journal of Physical, Human, and Regional Geosciences 40 (1): 34–45. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.geoforum.2008.01.008.

- Mailhot, Chantale, and Ann Langley. 2017. “Commercializing Academic Knowledge in a Business School: Orders of Worth and Value Assemblages.” In Research in the Sociology of Organizations, edited by Charlotte Cloutier, Jean-Pascal Gond, and Bernard Leca, 52:241–69. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Marginson, Simon. 2006. “Dynamics of National and Global Competition in Higher Education.” Higher Education 52 (1): 1–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-7649-x.

- Marginson, Simon. 2019. “Limitations of Human Capital Theory.” Studies in Higher Education 44 (2): 287–301. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2017.1359823.

- Mawer, Matt. 2017. “Approaches to Analyzing the Outcomes of International Scholarship Programs for Higher Education.” Journal of Studies in International Education 21 (3): 230–45. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315316687009.

- Mawer, Matt. 2018. “Magnitudes of Impact: A Three-Level Review of Evidence from Scholarship Evaluation.” In International Scholarships in Higher Education: Pathways to Social Change, edited by Joan R. Dassin, Robin R. Marsh, and Matt Mawer, 257–280. Springer International Publishing.

- McCloskey, Donald N. 1989. “Why I Am No Longer a Positivist.” Review of Social Economy 47 (3): 225–38. https://doi.org/10.1080/00346768900000025.

- Mittelmeier, Jenna, Sylvie Lomer, Miguel Antonio Lim, Heather Cockayne, and Josef Ploner. 2022. “How Can Practices with International Students Be Made More Ethical.” The Post-Pandemic University (blog). January 10, 2022. https://postpandemicuniversity.net/2022/01/10/how-can-practices-with-international-students-be-made-more-ethical/.

- Mukherjee, Sumita. 2011. Nationalism, Education, and Migrant Identities: The England-Returned (Routledge Studies in South Asian History ; 4). Oxford: Routledge.

- Nilsson, Johan, and Adrian Sadikovic. 2023. “Kinas hemliga avtal med studenter i Sverige - kräver lojalitet med regimen.” Dagens Nyheter, January 13, 2023, sec. News.

- Novotný, Josef, Ondřej Horký-Hlucháň, Tereza Němečková, Marie Feřtrová, and Lucie Jungwiertová. 2021. “Why Do Theories Matter? The Czech Scholarships Programme for Students from Developing Countries Examined Through Different Theoretical Lenses.” International Journal of Educational Development 80: 102307. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2020.102307.

- Nussbaum, Martha Craven. 2000. Women and Human Development: The Capabilities Approach. Cambridge; New York: Cambridge University Press.

- Nye, Joseph S. 2004. Soft Power: The Means to Success in World Politics. 1st ed. New York: Public Affairs.

- Oketch, Moses, Tristan McCowan, and Rebecca Schendel. 2014. “The Impact of Tertiary Education on Development: A Rigorous Literature Review. Department for International Development.” DFID. http://r4d.dfid.gov.uk.

- Ozga, Jenny. 2021. “Problematising Policy: The Development of (Critical) Policy Sociology.” Critical Studies in Education 62 (3): 290–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2019.1697718.

- Pashby, Karen, and Vanessa Andreotti. 2016. “Ethical Internationalisation in Higher Education: Interfaces with International Development and Sustainability.” Environmental Education Research 22 (6): 771–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/13504622.2016.1201789.

- Perna, Laura W., Kata Orosz, Bryan Gopaul, Zakir Jumakulov, Adil Ashirbekov, and Marina Kishkentayeva. 2014. “Promoting Human Capital Development: A Typology of International Scholarship Programs in Higher Education.” Educational Researcher 43 (2): 63–73. https://doi.org/10.3102/0013189X14521863.

- Perna, Laura W., Kata Orosz, and Zakir Jumakulov. 2015. “Understanding the Human Capital Benefits of a Government-Funded International Scholarship Program: An Exploration of Kazakhstan’s Bolashak Program.” International Journal of Educational Development 40: 85–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2014.12.003.

- Perna, Laura W., Kata Orosz, Zakir Jumakulov, Marina Kishkentayeva, and Adil Ashirbekov. 2015. “Understanding the Programmatic and Contextual Forces That Influence Participation in a Government-Sponsored International Student-Mobility Program.” Higher Education 69 (2): 173–88. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-014-9767-4.

- Pietsch, Tamson. 2016. Empire of Scholars: Universities, Networks and the British Academic World, 1850-1939. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

- Piketty, Thomas, and Arthur Goldhammer. 2014. Capital in the Twenty-First Century. Cambridge, Massachusetts: The Belknap Press of Harvard University Press.

- Ploner, Josef. 2018. “International Students’ Transitions to UK Higher Education – Revisiting the Concept and Practice of Academic Hospitality.” Journal of Research in International Education 17 (2): 164–78. https://doi.org/10.1177/1475240918786690.

- PPI Swedia. 2016. “Welcome to Sweden.” Perhimpunan Pelajar Indonesia di Swedia (Blog). September 17, 2016. http://ppiswedia.se/masakini/welcome-to-sweden/.

- Pritchard, Rosalind. 2011. “Re-Entry Trauma: Asian Re-Integration After Study in the West.” Journal of Studies in International Education 15 (1): 93–111. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315310365541.

- Reinecke, Juliane, Koen van Bommel, and Andre Spicer. 2017. “When Orders of Worth Clash: Negotiating Legitimacy in Situations of Moral Multiplexity.” In Research in the Sociology of Organizations, edited by Charlotte Cloutier, Jean-Pascal Gond, and Bernard Leca, 52:33–72. Leeds: Emerald Publishing Limited.

- Robeyns, Ingrid. 2006. “Three Models of Education: Rights, Capabilities and Human Capital.” Theory and Research in Education 4 (1): 69–84. https://doi.org/10.1177/1477878506060683.

- Schneijderberg, Christian. 2020. “Technical Universities in Germany: On Justification of the Higher Education and Research Markets.” In Technical Universities: Past, Present and Future, edited by Lars Geschwind, Anders Broström, and Katarina Larsen, 103–144. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Scott-Smith, Giles. 2008. “Mapping the Undefinable: Some Thoughts on the Relevance of Exchange Programs Within International Relations Theory.” The ANNALS of the American Academy of Political and Social Science 616 (1): 173–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/0002716207311953.

- Sen, Amartya. 1977. “Rational Fools: A Critique of the Behavioral Foundations of Economic Theory.” Philosophy & Public Affairs 6 (4): 317–344.

- Shih, Tommy, Albin Gaunt, and Stefan Östlund. 2020. Responsible Internationalisation: Guidelines for Reflection on International Academic Collaboration. R 20:01. Stockholm: STINT, The Swedish Foundation for International Cooperation in Research and Higher Education.

- Stark, David, Daniel Beunza, Monique Girard, and János Lukács. 2009. “Heterarchy.” In The Sense of Dissonance: Accounts of Worth in Economic Life, 1–34. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

- Stein, Sharon. 2016. “Rethinking the Ethics of Internationalization: Five Challenges for Higher Education.” InterActions: UCLA Journal of Education and Information Studies 12 (2), https://doi.org/10.5070/D4122031205.

- Stein, Sharon, and Vanessa Andreotti. 2016. “Cash, Competition, or Charity: International Students and the Global Imaginary.” Higher Education 72 (2): 225–39. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-015-9949-8.

- Tan, Emrullah. 2014. “Human Capital Theory: A Holistic Criticism.” Review of Educational Research 84 (3): 411–45. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654314532696.

- Teng, Amelia. 2014. “Many Slam A*Star Scientist’s Protest Against Her Scholarship Bond.” The Straits Times, December 4, 2014, Web Edition edition, sec. Education. https://web.archive.org/web/20141215185208/http://www.stcommunities.sg/education/many-slam-as.

- Thévenot, Laurent. 2022. “A New Calculable Global World in the Making: Governing Through Transnational Certification Standards.” In The New Politics of Numbers, edited by Andrea Mennicken, and Robert Salais, 197–252. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Thévenot, Laurent, and Søren Jagd. 2004. “The French Convention School and the Coordination of Economic Action: Laurent Thévenot Interviewed by Søren Jagd at the EHESS Paris.” Economic Sociology: European Electronic Newsletter 8: 10–16.

- Tight, Malcolm. 2004. “Research Into Higher Education: An A-Theoretical Community of Practice?” Higher Education Research & Development 23 (4): 395–411. https://doi.org/10.1080/0729436042000276431.

- Tournès, Ludovic, and Giles Scott-Smith, eds. 2017. A World of Exchanges: Conceptualizing the History of International Scholarship Programs (Nineteenth to Twenty-First Centuries). 1st ed. New York: Berghahn Books.

- Tran, Ly Thi, and Thao Thi Phuong Vu. 2018. “‘Agency in Mobility’: Towards a Conceptualisation of International Student Agency in Transnational Mobility.” Educational Review 70 (2): 167–87. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2017.1293615.

- Trilokekar, Roopa Desai. 2015. “Federal Governments In International Education.” CSHE Research & Occasional Papers Series, Berkeley, no. CSHE.2.15: 18.

- van Gaalen, Adinda. 2021. “Mapping Undesired Consequences of Internationalization of Higher Education.” In Inequalities in Study Abroad and Student Mobility: Navigating Challenges and Future Directions. 1st ed., edited by Suzan Kommers, and Krishna Bista, 11–23. New York: Routledge.

- Vanichakorn, Neelawan. 2005. “Application of International Education: How Would Skills and Knowledge Learned Abroad Work Back Home?” The Journal of Industrial Technology 1 (2): 5.

- van Zanten, Agnès. 2019. “Neo-Liberal Influences in a ‘Conservative’ Regime: The Role of Institutions, Family Strategies, and Market Devices in Transition to Higher Education in France.” Comparative Education 55 (3): 347–66. doi:10.1080/03050068.2019.1619330.

- Walker, Melanie. 2012. “A Capital or Capabilities Education Narrative in a World of Staggering Inequalities?” International Journal of Educational Development 32 (3): 384–93. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijedudev.2011.09.003.

- Waluyo, Budi, Sothy Eng, and Alexander W Wiseman. 2019. “Examining a Model of Scholarship for Social Justice.” Research in Comparative and International Education 14 (2): 272–93. https://doi.org/10.1177/1745499919846013.

- Waters, Johanna, and Rachel Brooks. 2021. Student Migrants and Contemporary Educational Mobilities. Cham: Springer International Publishing.

- Wilson, Iain. 2014. International Education Programs and Political Influence. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Wilson, Iain. 2015. “Ends Changed, Means Retained: Scholarship Programs, Political Influence, and Drifting Goals.” The British Journal of Politics and International Relations 17 (1): 130–51. https://doi.org/10.1111/1467-856X.12012.

- Yang, Peidong. 2016. International Mobility and Educational Desire. New York: Palgrave Macmillan US.

- Yang, Peidong. 2020. “Toward a Framework for (Re)Thinking the Ethics and Politics of International Student Mobility.” Journal of Studies in International Education 24 (5): 518–34. https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315319889891.

- Ye, Rebecca. 2021. “Testing Elite Transnational Education and Contesting Orders of Worth in the Face of a Pandemic.” Educational Review 74 (3): 704–719. https://doi.org/10.1080/00131911.2021.1958755.

- Ye, Rebecca, and Erik Nylander. 2023. “The Scholars.” In Education and Power in Contemporary Southeast Asia, edited by Azmil Tayeb, Rosalie Metro, and Will Brehm, 1st ed., 171–86. London: Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781003397144-14.