?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

Despite recent evidence linking top management power with firm performance, our understanding about the interaction effect between power and personal characteristics of the top manager is still very limited. Building on and extending the Upper Echelons and Power literature, we address the empirical question: How, i.e. UK Vice-Chancellors’ (VC) power influences the efficiency of UK universities? We use panel data from 126 UK universities from 2016 to 2020 to test our hypotheses. Our findings demonstrate that VC power, and its constituents affect efficiency. VCs with more power tend to improve the efficiency of the universities they run respectively. Specifically, VC in receipt of higher compensation and honour medals tend to improve the efficiency of the university they run. In contrast, if they are Oxbridge graduate and have long tenure, the efficiency will decline. More importantly, the interaction results show that a high-power VC who is not from Asian or minority background is shown to improve efficiency but a high-power VC who is a female will drive up efficiency. Our analyses reveal that a VC’s power and the constituents to VC power play a crucial role in determining the efficiency level of the university. Furthermore, origin and gender of a VC will moderate the VC’s power in influencing the efficiency level.

Introduction

Society often attributes firm success to CEOs due to their unique role in top management (Cannella, Finkelstein, and Hambrick Citation2008; Hambrick Citation2007). In higher education, under New Public Management (NPM) policies, university Vice-Chancellors (VCs) are increasingly seen as akin to CEOs. Like CEOs, VCs garner public attention mainly for their pay, which mirrors private sector CEOs but is often deemed inappropriate for quasi-public entities and compared to other academic salaries (Lyons and Hil Citation2018).

This paper explores how VC power affects university efficiency. Occupying the top executive role, VCs concentrate decision-making authority and use their power to set strategic direction, structure, and resource allocation to fulfil the university's mission. Specifically, they optimise performance by balancing inputs and outputs through effective resource allocation. Following Upper Echelons Theory (UET), we develop a research model linking VC power to efficiency.

In the higher education context, appropriate VC power can lead to positive firm performance. However, excessive VC power can result in exaggerated self-opinion and actions against shareholders’ interests (Finkelstein and D’aveni Citation1994). This is because centralised power (Pitcher and Smith Citation2001) may discourage diverse ideas (Dewett Citation2004). Such power plays can lead to uninformed, risky decisions (Gupta et al. Citation2016), negatively affecting firm performance and value.

VC characteristics can yield varying managerial power levels affecting university performance. High-power VCs can effectively marshal resources to meet strategic goals. However, overpowered VCs may launch flawed initiatives causing institutional failure. For instance, recent growth in VC power, coupled with inadequate governance by university councils, has escalated operational risks in UK universities (Kakabadse et al. Citation2020).

The study offers multiple contributions. Firstly, while existing literature focuses on university performance affecting CEO pay (Johnes and Virmani Citation2020), ours is the first to explore the relationship between CEO’s power and university’s efficiency. Secondly, we develop the VC power concept through four established measures in CEO power studies: compensation, education, tenure, and status. While executive compensation is widely discussed as impacting firm performance, it is an imprecise and limited indicator of VC’s role. Hence, we include a wider set of VC attributes to quantify power. Thirdly, we opt for efficiency over financial performance metrics, given the complexity of Higher Education Institutions (HEIs) and their quasi-governmental nature. Some measures suit private and public firms but not HEIs. Additionally, financial metrics focus on output, neglecting input factors that are also crucial in a university context. Thus, incorporating both HEI inputs and outputs via efficiency metrics provides a fuller performance picture. Fourthly, our findings yield valuable policy insights for HEI governance. For instance, we examine the optimal VC tenure relative to HEI efficiency. Success or failure often hinges on senior management, with VCs being the decision-making focal point. Lastly, we explore the impact of VC’s origin or gender on HEI efficiency, a subject attracting significant media and academic interest.

Literature review

Overview of HEI performance in the context of the NPM policy discourse

Universities mainly produce three outputs: (1) knowledge and skills transfer through teaching; (2) research for new knowledge and innovation; and (3) broader social and economic impact (Melo, Sarrico, and Radnor Citation2010). Performance measurement for these activities is widely debated. Currently, HEIs performance is often framed in terms of efficiency (Boden and Rowlands Citation2022). Johnes, Portela, and Thanassoulis (Citation2017) define HE efficiency as ‘ … when outputs from education (such as test results or value added) are produced at the lowest level of resource (be that financial or, for example, the innate ability of students)’. This reflects HE's role as a public good and the accountability needed from HEIs due to diverse economic, policy, and demographic factors. These factors include ongoing public spending scrutiny, quality management adoption, and a surge in student numbers in both undergraduate and postgraduate courses. Also, With the advent of student loans and the focus on ‘student-centred metrics’, the notions of ‘value-for-money’ and ‘student as customer’ emerged (Witte and López-Torres Citation2017).

These changes are often linked to New Public Management (NPM) reforms, which have drastically altered university governance and management in the UK and beyond in recent decades. NPM focuses on public sector reforms that adopt private sector methods to boost efficiency, competition, and performance metrics, aiming to cut inefficiencies (Hood Citation1991; Citation1995; Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017). The widespread NPM discourse has validated university management's adoption of corporate practices, focusing more on performance metrics, competitiveness, and revenue (Deem, Hillyard, and Reed Citation2007; Marginson Citation2004). Under the NPM model, Vice-Chancellors gain more control over resources and strategy but face pressure to show institutional performance and efficiency (Pollitt and Bouckaert Citation2017).

NPM reforms are associated with marketisation, as universities act like businesses, vying for students, research funds, and brand recognition via rankings (Hazelkorn Citation2007). Broader criticism holds that such marketisation commercialises universities, eroding their public service role and affecting academic leadership focus (Molesworth, Scullion, and Nixon Citation2010; Tomlinson Citation2017). However, research from a less critical view identifies various positive impacts of NPM reforms on higher education. For instance, it led to clear accountability systems, performance-driven resource allocation, increased productivity, and better organisational responsiveness (Deem and Brehony Citation2005; Parry and Thompson Citation2002). Recent studies indicate a shift to a ‘post-NPM’ model, which retains NPM elements but addresses prior criticisms (Clarke and Newman Citation2017).

The role of VC and HEI performance

As stated, NPM reforms grant university leaders greater managerial freedom but also heightened accountability. Analysing VCs’ traits and leadership offers insights into their responses to NPM demands in higher education. VCs decisions can significantly impact their university's performance and competitiveness. The VC role has evolved beyond academic leadership to encompass value-for-money, efficiency, financial stability, organic growth, and internationalisation (Liu et al. Citation2020). This results from ongoing policy and market shifts in higher education, commonly linked to neoliberalism, with studies highlighting the ‘marketisation’ of universities, notably in the UK, USA, and Australia (Boden and Rowlands Citation2022; Scullion, Molesworth, and Nixon Citation2011).

Marketisation involves universities adopting corporate principles across operations, influenced by policymakers’ market-focused discourse (Molesworth, Scullion, and Nixon Citation2010). Reduced public funding and increased accountability pressure have turned universities into corporate-like entities (Brown and Carasso Citation2013; Naidoo and Williams Citation2015). The ‘massification’ of higher education has sped up marketisation by compelling universities to be more competitive in attracting students (Giannakis and Bullivant Citation2016; Mok and Neubauer Citation2016).

Amid the adoption of corporate practices in universities, the role of Vice-Chancellors has corporatised with a significant pay rise. This positions VCs as managers paid for owning major performance gains and strategy, although studies show no link between their pay and performance (Boden and Rowlands Citation2022). Previous research shows varied results on VC pay and university performance. Dolton et al. (Citation2003) and Newton et al. (Citation2019) find a positive link, particularly for highly compensated VCs and those with awards or knighthoods. Conversely, some studies report a weak or non-existent relationship (Lucey, Urquhart, and Zhang Citation2022; Tarbert, Tee, and Watson Citation2008). Other research examines the link between HEIs’ short- or long-term goals and VC pay. Elmagrhi and Ntim (Citation2022) show a positive link between high VC pay and short-term financial goals, and lower VC pay with a focus on long-term social performance.

Most existing studies focus on VC compensation's link to university performance, not efficiency (Johnes and Virmani Citation2020). Fewer studies look at broader VC traits affecting university efficiency. For instance, Khoo et al. (Citation2022) claim that highly narcissistic VCs worsen university reach and research. There is a literature gap on how VC traits broadly relate to university efficiency.

Upper Echelons Theory: senior management characteristics and efficiency

Extensive literature explores senior managers, mainly CEOs, in corporate performance. UET explains how their backgrounds and traits shape organisational decision-making. These traits include demographics and ‘Observable Technical Characteristics’ like age and tenure, which impact CEO decision-making and efficiency (Hambrick and Mason Citation1984; Shahab et al. Citation2020). UET suggests that executives’ personal perspectives affect strategic decision-making. Greater managerial discretion boosts UET’s predictive power. CEO workload also moderates UET effectiveness. Heavy workloads lead to less comprehensive decision-making, affecting UET’s predictive ability (Hambrick Citation2007). UET faces criticism for its conceptual gaps, including limited focus on cognitive processes affecting CEO decisions (Menz Citation2012; Neely et al. Citation2020) and relationship dynamics within management teams (Helfat and Martin Citation2015). Questions also arise about its measures and replicability (Hodgkinson and Sparrow Citation2002).

Senior management power

Senior managers’ influence on strategy, structure, processes, and resource allocation is termed CEO power (Amedu and Dulewicz Citation2018). This complex concept has been gauged through various metrics: organisational position, tenure, directorship (Tien, Chen, and Chuang Citation2013); decision influence (Adams, Almeida, and Ferreira Citation2005); and education (Finkelstein Citation1992). CEO power reflects their concentrated decision-making authority (Finkelstein Citation1992; Gupta et al. Citation2016). It is widely accepted that CEOs use this power to act quickly (Cannella and Monroe Citation1997), bypass middle management (Harris and Helfat Citation1998; Pfeffer Citation1997), enact clear decisions (Donaldson and Davis Citation1991). No research exists on VC power.

Studies show varied links between CEO power and firm performance. Longer CEO tenure correlates with reduced performance (Luo, Kanuri, and Andrews Citation2014), attributed to leader life cycle theory. Early-stage CEOs learn fast and take risks, while tenured CEOs become complacent and risk averse, affecting performance negatively (Wulf et al. Citation2010). High CEO power links to decision autonomy, benefiting distressed firms. However, it can negatively affect governance in stable organisations by fostering unilateral, uninformed CEO actions. CEO power's impact on performance is influenced by external factors and market conditions. In competitive settings, high-power CEOs correlate with poor performance (Han, Nanda, and Silveri Citation2016). Firm life cycle stage affects CEO power impact on performance. Early-stage firms benefit from authoritative CEOs for quick responses. In later stages, they're less useful due to the need for governance and participatory decisions (Harjoto and Jo Citation2009).

Upper Echelons Theory, VC power, and HEI efficiency

Literature shows varied impact of senior management power on performance (Tien, Chen, and Chuang Citation2013). Using UET, prior research indicates senior manager traits affect both managerial power and performance via strategic planning (Amedu and Dulewicz Citation2018; Harjoto and Jo Citation2009; Manner Citation2010). Also, research has shown CEO traits like education (Shahab et al. Citation2020), tenure (Harjoto and Jo Citation2009; Luo, Kanuri, and Andrews Citation2014), prior experience (Saidu Citation2019), and skills (Kaplan et al. Citation2012) affect organisational performance. Our study investigates VC power in university strategy formulation and aims to link VC power to university efficiency. Furthermore, we examine VC traits in the higher education context, focusing on VC characteristics like education, experience, socioeconomic factors (e.g. Gender, Oxbridge, Knighthood) and tenure impacting university efficiency. The importance of VC power and traits on university efficiency led to the following two hypotheses:

Hypothesis 1: The power of VC has an impact on the university efficiency.

Hypothesis 2: The educational background, prior experiences, socioeconomic characteristics, and tenure of the VC have an impact on the university efficiency.

Methodology

Data

We retrieve inputs and outputs of efficiency scores from the Higher Education Statistics Agency (HESA)Footnote1 and ScopusFootnote2 over the period 2016-2020. Only 126 universities have the necessary information to generate efficiency scores.Footnote3 We obtain information about VC salary (and compensation) from the university's financial reports and university accounting from the HESA. VC characteristics are collected from who’s whoFootnote4, university’s profiles, LinkedIn, and through Freedom of Information Act (FOI) requests.

Data envelopment analysis (DEA)

Measuring the efficiency of the university system has recently become a topic of much interest of policy makers, scholars, and researchers. This paper was initially motivated by a real-world application to the evaluation of educational performance of UK universities (Abramo et al. Citation2011; Agasisti, Barra, and Zotti Citation2016; Berbegal-Mirabent, Lafuente, and Solé Citation2013; Johnes Citation2006; Laureti, Secondi, and Biggeri Citation2014; Lee and Worthington Citation2016; Ruiz, Segura, and Sirvent Citation2015; Yaisawarng and Ng Citation2014). Universities in developed countries – including Australia, the UK, the US, various European countries, and China – have been the focus of efficiency studies. Most of these studies use the DEA method (Fizel and D’Itri Citation1997), which is a non-parametric approach that is utilised to assess the relative effectiveness of various decision-making units operating within a multi-input, multi-output environment. The DEA approach has been used extensively in education efficiency related studies (Berbegal-Mirabent, Lafuente, and Solé Citation2013; Johnes Citation2006).Footnote5 Consider the ith university with outputs and inputs yi, xi (that are all positive) the output-oriented DEA efficiency score is determined by the solution of the problem below.

(1)

(1) University’s characteristics are fixed, and efficiency is maximised by maximising outputs subject to its given level of inputs. A measure of

indicates that the university is technically efficient, and inefficient if

. The DEA efficiency score given by Equation (1) assumes variable return to scale or TE, but we can impose constant return to scale or OE by removing the constraint

. The OE evaluates efficiency and recognise the inefficiency's source and level. The OE may prove unsuitable for a group of universities with a large scale of operations. On the other hand, TE estimates the technical efficiency based on the scale of operation in the university as a decision-making unit (DMU) required to render services to beneficiaries at the time of measurement. TE encompasses the data more closely than OE and estimates technical efficiency scores greater than or equal to OE. The TE approach is more appropriate than OE when the sample consists of a small to large DMU. In , we present our estimated efficiency scores including scores based upon OE and TE efficiency scores. The average initial efficiency score for the whole system is 0.77 following OE and 0.84 assuming TE. In 2019, the efficiency scores for the whole system were the lowest being 0.70 (OE) and 0.80 (TE).

Table 1. Overall and technical efficiency scores of the whole UK education sector from 2016 to 2020.

Baseline DEA Model

The efficiency scores, , of unit i obtained are regressed on explanatory variables as follows.

(2)

(2) where

is university i’s efficiency score in period t, which is measured as: OE and TE scores;

are the explanatory variables which are grouped into VC powers

and other variables

. shows definitions of variables.

Table 2. Definitions of variables.

We used Principal Component Analysis (PCA) to form the Power component variable.Footnote6 A ranking exercise is created once the Power variable was constructed. Supplemental material shows the ranking where 1 being the highest ranked university according to the VC Power. Edge Hill University has been identified as the highest ranked university and the University of Chichester as the lowest ranked university amongst all considered universities in the UK.

Generalised method of moments in panel data

The Hausman test statistics showed that some of the variables in the model are endogenously determined. We employ the system of Generalised Method of Moment (GMM) suggested by Arellano and Bond (Citation1991) and Blundell and Bond (Citation1998) in dealing with these sources of endogeneity. Lagged values of the dependent variables are used as instruments to control endogenous relationship. We limited the lag length up to t−4 in the instrument set to reduce the instrument count (Roodman Citation2009). Since, the J-statistic (Sargan statistic) implied that the test of overidentifying restrictions cannot reject its null hypothesis we could retain the validity of the instruments in this study.

Descriptive statistics and multicollinearity check

reports the descriptive statistics while presents Pearson correlation for multicollinearity check. Interestingly, 24% of the VCs in the UK HEIs have obtained their educational qualifications either from Oxford or Cambridge Universities. 88% of the VCs are British citizens and most of them are males (72%). However, the VCs from the black, Asian, and ethnic minority background (BAME) stays at a significantly low level (5%). Only a 17% of them have been internally appointed while 17% have had experience in other HEIs. In , the range for our explanatory variables in the regression model is from −0.192 to 0.183, hence below the threshold to confirm the absence of multicollinearity and included all variables in our regression model. Footnote7

Table 3. Descriptive statistics.

Table 4. Pearson correlations.

Results and findings

details the coefficients of both the main effect and the interaction effect models in this research. Model 1 tests the main effect of the key independent variables (OE and TE) and power, including all other control variables (hypothesis 1). The results support the predicted relationship between VC overall efficiency (OE) and Power (β = 0.0365) and VC technical efficiency (TE) and Power (β = 0.0311). That is, when the VC has more power, the efficiency level is improved. Model 2 includes all the explanatory and control variables (hypothesis 2). OE shows positive significant relationships with Compensation and Awards, and negative significant relationships with Tenure and Education. Regarding TE, Compensation and Awards are positive and significant while Tenure is negatively significant, which is consistent with the results from OE except for Education.

Table 5. The effect of Power on efficiency and other variables (including VC Compensation).

In Model 3, OE is positively significant with Compensation and Awards but negatively significant with Education. On the other hand, TE is positively significant with Compensation and negatively significant with Tenure. Although Model 2 shows a negative relationship between Efficiency (OE and TE) with Tenure, the quadratic term of Tenure (Model 3) presents that OE and TE have a turning point of 13 years and 9 months and 9 years, respectively. The results imply that OE and TE initially decline but after the turning points, both efficiency scores turn around and start to increase positively with Tenure. The findings are similar with the interaction effects (Model 4), which predicts that the efficiency vary according to the Origin and Gender, as there are significant effects on the interaction terms. For both OE and TE, there are negative relationships with Origin and Gender.

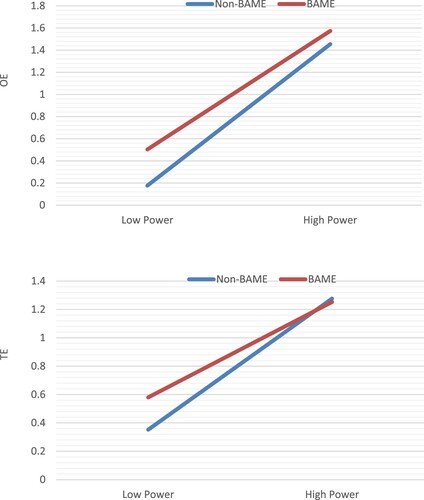

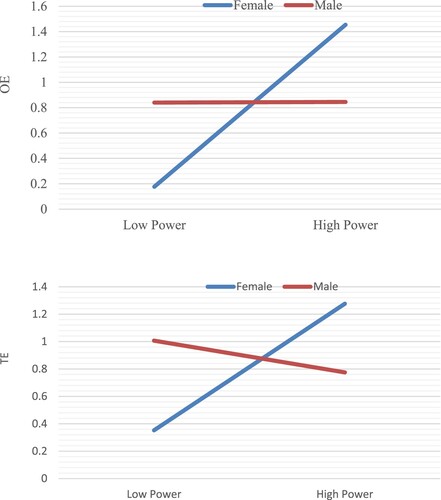

As a robustness test, we also ran the models considering the VC Salary, yielding comparable results for Models 1 and 2 (Appendix A). To illustrate the patterns of the significant moderating effects that supported the hypothesis 2, we plotted the interaction graphs as shown below. Both interactions of VC Power with Origin (BAME and Non-BAME) and Gender have a negative significant relationship with OE.

shows the interactions of origin with VC Power and OE (TE). We observed that high Power and non-BAME interaction leads to high OE (TE) whereas, low Power and non-BAME interaction leads to low OE (TE). When BAME interacts with low Power it leads to high OE (TE). Similarly, high Power and BAME would result in low OE (TE) as well.

depicts the interactions of Gender with VC Power and OE (TE). Interestingly, the low Power-Male interaction leads to high OE (TE) and low Power-Female interaction leads to low OE (TE). Vice versa, high Power-Male interaction leads to low OE (TE) whereas high Power-Female interaction would bring high OE (TE).

We observe that the interaction effects for Origin and Gender with the relationships between Power and OE (TE) are consistent and with no substantial difference as well. The instrumental variables include England, Wales, Scotland, Origin, BritCitz, INTER, KNI, Gender, VCOHE, and the lagged of Tenure, Compensation, Leverage, ROA, TA. Since, the J-statistic (Sargan statistic) implied that the test of overidentifying restrictions cannot reject its null hypothesis we could retain the validity of the instruments in this study where the model as estimated is not mis-specified (p = .7921 and 0.7282, Model 1; p = .0069 and .3162, Model 2; p = .9583 and .3888, Model 3, p = .4821 and .4907, Model 4 in ).

Further, we also implement the DEA bootstrap approach (Simar and Wilson Citation1998; Citation2002) on efficiency (Appendices B and C). The true efficiency score is not observed directly, rather it is empirically estimated. We presume that the original data was generated by a data-generating process, and that we can replicate this process by creating a new (pseudo) data set based on the original data set. The DEA model is then re-estimated using new data. The results show that the effect of Power on bootstrapped efficiency and other variables including VC Compensation and VC Salary are consistent with the original efficiency.Footnote8

Discussion

Under current discourse shaped by marketisation and massification (Molesworth, Scullion, and Nixon Citation2010), higher education is seen as a service, and VCs are spotlighted like CEOs of public firms (Hutaibat et al. Citation2021). In a NPM context, VCs face pressure and are accountable for their universities’ successes or failures (Pilonato and Monfardini Citation2020). Increasing pressure on VCs from stakeholders resembles CEO pressures and stems from the belief that VCs can shape strategy and mobilise resources to meet university goals (Bugeja et al. Citation2021; Hackman Citation1985). Our discussion focuses on the interplay between VC power and university efficiency and outlines four key take-aways.

First, our hypothesis 1 shows a positive link between VC Power and university efficiency. A high-power VC improves efficiency in core university functions like teaching and research. This aligns with UET research linking senior manager power to organisational efficiency (Harjoto and Jo Citation2009). However, literature suggests that powerful managers’ autonomous actions can affect organisational efficiency variably (Han, Nanda, and Silveri Citation2016). Thus, the VC's impact on university efficiency must be contextualised, considering potential drawbacks from autonomous decision-making.

Second, our results link Power constituents – Compensation, Education, Tenure – to university efficiency. Existing studies confirm the link between VC pay and university performance but mainly focus on justifying VC pay (Boden and Rowlands Citation2022; Johnes and Virmani Citation2020; Newton et al. Citation2019). Our study finds a positive link between VC Compensation and university efficiency. Prior CEO research (Tien, Chen, and Chuang Citation2013) suggest VCs are rightly rewarded for performance. This supports the idea that VC actions guide universities toward their goals which incentivizes VCs to implement strategies, boosting efficiency and performance. Next, the VC's educational background significantly impacts the efficiency of the university they lead. VCs graduated from Cambridge or Oxford show lower OE, potentially due to narcissistic traits that can harm university performance (Khoo et al. Citation2022). Conversely, VCs with an OBE are associated with enhanced efficiency, corroborating previous research linking such honours to positive university outcomes (Newton et al. Citation2019). Furthermore, our research shows that longer VC tenure is negatively correlated with university efficiency, aligning with studies that find a similar inverse relationship between CEO tenure and firm performance (Harjoto and Jo Citation2009; Wulf et al. Citation2010). Extended tenure can lead senior managers to accumulate more power, becoming complacent and risk-averse, thereby stifling innovative ideas that could boost organisational efficiency.

Third, what is the time frame for a new VC to improve efficiency? The findings show VCs usually succeed a less efficient predecessor. Hence, the new VC aims to reverse efficiency declines. Our data indicates nearly 14 years for OE and 9 years for TE efficiency improvements. This aligns with literature indicating 10+ years for organisational efficiency improvements post-CEO appointment (Miller and Shamsie Citation2001). Efficiency gains in universities with a new VC will take time to materialise. In the UK, the average VC tenure is 5 years, while departing VCs average around 8 years (Hillman Citation2022). Our data imply that VCs with tenures under 9 years may oversee declines in both overall and technical efficiencies. Early years of a VC's term could pose efficiency challenges. Between 9 and nearly 14 years, although TE may improve, OE could still decline, posing governance implications for VC recruitment and removal. After nearly 14 years, both OE and TE start to improve. This suggests that universities may benefit from VCs with tenures exceeding this period. Governing bodies should weigh these findings when determining VC tenure lengths. Shorter tenures may offer fresh perspectives but risk efficiency declines, while longer ones could offer stability and efficiency gains post the identified turning points.

Fourth, we find that the interplay between a VC's power, origin, and gender notably influences university efficiency. High-power VCs from BAME backgrounds are linked to decreased overall and technical efficiency. Regarding gender, high-power male VCs correlate with efficiency reductions, whereas high-power female VCs are associated with improved technical efficiency. These results highlight the complexity of VC influence, showing it is not isolated but intertwined with racial, ethnic, and gender factors. These findings should not be seen as advocating for recruitment biases towards specific genders or ethnicities. Rather, they emphasise the need to consider diverse factors in VC appointments. While previous research has centred on strategic and firm-level factors (Baysinger and Hoskisson Citation1989), our study adds by showing that a VC's race, ethnicity, and gender can significantly impact university efficiency. This calls for a more holistic understanding of efficiency-driving factors.

Conclusion

The role of university VCs has evolved to mirror that of corporate CEOs, influenced by marketisation and NPM in higher education (Deem Citation2001; Erickson, Hanna, and Walker Citation2021). VCs now face heightened expectations for efficiency and have greater control over strategy and resources (Hutaibat et al. Citation2021). Yet, the link between VC power, characteristics, and efficiency is not well-understood. Utilising UET, our study enriches understanding of university efficiency determinants and provides valuable governance insights for VC recruitment, evaluation, and tenure.

We use DEA to calculate university efficiency scores, presenting results in both overall efficiency (OE) and technical efficiency (TE) terms. When sample sizes vary, TE is preferable to OE. We find positive correlations between VC power and both OE and TE. VC compensation, education, tenure, and honours also significantly impact efficiency, although tenure negatively affects it. Education is negatively tied only to OE. VC power interacts with race, ethnicity, and gender, affecting efficiency. High-power VCs from BAME backgrounds and male VCs are generally linked to efficiency declines, whereas high-power female VCs tend to improve technical efficiency.

Our findings suggest several action points for university governing bodies. First, newly appointed VCs will need at least 9 years to realise substantial efficiency gains, making frequent replacements potentially counterproductive. Second, technical, and overall efficiencies are expected to decline until the 9- and 14-year marks, after which they should improve. This timeframe should guide evaluations for leadership changes. Third, high-power BAME and low-power female VCs show efficiency declines, suggesting a need for governance efforts to enable these leaders to fully capitalise on their roles. Governing bodies should promote inclusivity and address barriers that could hinder the efficacy of BAME or female VCs.

The Executive Management Team (EMT) plays a crucial part in the institution's strategic leadership, with important decisions involving input from these individuals. Despite the Chancellor's seemingly ceremonial role, they hold soft power that can influence the VC. Factors like the composition of the EMT, including gender, age, and prestige, can impact the VC's authority. A more diverse EMT can lead to better decision-making. Our study highlights the need to consider a VC's prior experience, especially in competitive universities, when assessing their leadership capabilities.

Future research should explore the impact of the Chancellor and EMT on VC power and university efficiency, emphasising the importance of looking beyond VC tenure to understand leadership dynamics. Additionally, the impact of political ideology on decision-making processes within public organisations has been acknowledged as significant (Rabovsky and Rutherford Citation2016). However, the existing models of university efficiency have not considered the potential role of political ties and ideology in influencing VCs power. Hence, the examination of VCs’ political ties and their influence on university performance emerges as a crucial area for future research, contingent upon the acquisition of appropriate data.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Notes

3 The inputs include: (i) staff, measured by the total number of full-time academic staff; (ii) students are total number of full-time equivalent students including undergraduates and postgraduates; and (iii) total expenditure, which are described as total expenditure of the higher education institution. The outputs consist of: (i) graduates, which are total number of graduates including undergraduates and postgraduates; (ii) publication, measured by all publications in the academic year; and (iii) total income, defined as total income of the higher education institution.

5 Previous studies (Laureti, Secondi, and Biggeri Citation2014; Ruiz, Segura, and Sirvent Citation2015; Lee and Worthington Citation2016) integrated full-time equivalent (FTE) staff and students into their analyses. Consistent with the approach advocated by Johnes (Citation2006) and Berbegal-Mirabent, Lafuente, and Solé (Citation2013), our study utilizes the total number of full-time academic staff and full-time equivalent students.

6 PCA is a well-known statistical tool used for the analysis of numerical set of data concerning several objects with respect to several variables as it aims to synthesize the data set in terms of components, i.e., unobserved variable ‘Power’ expressed as a linear combination of the observed variables namely, Compensation, Tenure, Awards and Education.

7 According to Gujarati (Citation2003), multicollinearity exists when the two correlation coefficients between two regressors are usually more than 0.8.

8 Two variables (Education and Awards) are not significant (NS) in the model considering VC Compensation when bootstrapped technical efficiency score (TE) is the dependent variable (Appendix B).

References

- Abramo, Giovanni, Tindaro Cicero, Ciriaco Andrea, and D. Angelo. 2011. “A Field-Standardized Application of DEA to National-Scale Research Assessment of Universities.” Journal of Informetrics 5 (4): 618–28. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.joi.2011.06.001.

- Adams, Renée B., Heitor Almeida, and Daniel Ferreira. 2005. “Powerful CEOs and Their Impact on Corporate Performance.” Review of Financial Studies 18 (4): 1403–32. https://doi.org/10.1093/rfs/hhi030.

- Agasisti, Tommaso, Cristian Barra, and Roberto Zotti. 2016. “Evaluating the Efficiency of Italian Public Universities (2008–2011) in Presence of (Unobserved) Heterogeneity.” Socio-Economic Planning Sciences 55 (C): 47–58. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.seps.2016.06.002.

- Amedu, Samson, and Victor Dulewicz. 2018. “The Relationship Between CEO Personal Power, CEO Competencies, and Company Performance.” Journal of General Management 43 (4): 188–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/0306307018762699.

- Arellano, Manuel, and Stephen Bond. 1991. “Some Tests of Specification for Panel Data: Monte Carlo Evidence and an Application to Employment Equations.” The Review of Economic Studies 58 (2): 277–97. https://doi.org/10.2307/2297968.

- Baysinger, Barry, and Robert E. Hoskisson. 1989. “Diversification Strategy and R&D Intensity in Multiproduct Firms.” Academy of Management Journal 32 (2): 310–32. https://doi.org/10.2307/256364.

- Berbegal-Mirabent, Jasmina, Esteban Lafuente, and Francesc Solé. 2013. “The Pursuit of Knowledge Transfer Activities: An Efficiency Analysis of Spanish Universities.” Journal of Business Research 66 (10): 2051–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2013.02.031.

- Blundell, Richard, and Stephen Bond. 1998. “Initial Conditions and Moment Restrictions in Dynamic Panel Data Models.” Journal of Econometrics 87 (1): 115–43. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0304-4076(98)00009-8.

- Boden, Rebecca, and Julie Rowlands. 2022. “Paying the Piper: The Governance of Vice-Chancellors’ Remuneration in Australian and UK Universities.” Higher Education Research & Development 41 (2): 254–68. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2020.1841741.

- Brown, Roger, and Helen Carasso. 2013. Everything for Sale? The Marketisation of UK Higher Education. London/New York: Routledge.

- Bugeja, Martin, Brett Govendir, Zoltan Matolcsy, and Greg Pazmandy. 2021. “Is There an Association Between Vice-Chancellors’ Compensation and External Performance Measures?” Accounting & Finance 61 (1): 689–726. https://doi.org/10.1111/acfi.12590.

- Cannella, Bert, Sydney Finkelstein, and Donald C. Hambrick. 2008. Strategic Leadership: Theory and Research on Executives, Top Management Teams, and Boards. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Cannella, Albert A., and Martin J. Monroe. 1997. “Contrasting Perspectives on Strategic Leaders: Toward a More Realistic View of Top Managers.” Journal of Management 23 (3): 213–37. https://doi.org/10.1177/014920639702300302.

- Clarke, John, and Janet Newman. 2017. “‘People in This Country Have Had Enough of Experts’: Brexit and the Paradoxes of Populism.” Critical Policy Studies 11 (1): 101–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/19460171.2017.1282376.

- Deem, Rosemary. 2001. “Globalisation, New Managerialism, Academic Capitalism and Entrepreneurialism in Universities: Is the Local Dimension Still Important?” Comparative Education 37 (1): 7–20. https://doi.org/10.1080/03050060020020408.

- Deem, Rosemary, and Kevin J. Brehony. 2005. “Management as Ideology: The Case of ‘New Managerialism’ in Higher Education.” Oxford Review of Education 31 (2): 217–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054980500117827.

- Deem, Rosemary, Sam Hillyard, and Michael Reed. 2007. Knowledge, Higher Education, and the New Managerialism: The Changing Management of UK Universities. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dewett, Todd. 2004. “Creativity and Strategic Management.” Journal of Managerial Psychology 19 (2): 156–69. https://doi.org/10.1108/02683940410526118.

- Dolton, Peter, Ada Ma, James Wright, Andrew Hamnett, Ron Cooke, Colin Campbell, and Geoff Whitty. 2003. “CEO Pay in the Public Sector: The Case of Vice-Chancellors in UK Universities.” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/228686409_CEO_pay_in_the_public_sector_The_case_of_vice_chancellors_in_UK_universities.

- Donaldson, Lex, and James H. Davis. 1991. “Stewardship Theory or Agency Theory: CEO Governance and Shareholder Returns.” Australian Journal of Management 16 (1): 49–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/031289629101600103.

- Elmagrhi, Mohamed H., and Collins G. Ntim. 2022. “Vice-Chancellor Pay and Performance: The Moderating Effect of Vice-Chancellor Characteristics.” Work, Employment and Society 095001702211113. https://doi.org/10.1177/09500170221111366.

- Erickson, Mark, Paul Hanna, and Carl Walker. 2021. “The UK Higher Education Senior Management Survey: A Statactivist Response to Managerialist Governance.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (11): 2134–51. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1712693.

- Finkelstein, Sydney. 1992. “Power in Top Management Teams: Dimensions, Measurement, and Validation.” Academy of Management Journal 35 (3): 505–38. https://doi.org/10.2307/256485.

- Finkelstein, Sydney, and Richard A. D’aveni. 1994. “CEO Duality as a Double-Edged Sword: How Boards of Directors Balance Entrenchment Avoidance and Unity of Command.” Academy of Management Journal 37 (5): 1079–108. https://doi.org/10.2307/256667.

- Fizel, John L., and Michael P. D’Itri. 1997. “Managerial Efficiency, Managerial Succession and Organizational Performance.” Managerial and Decision Economics 18 (4): 295–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1099-1468(199706)18:4%3C295::AID-MDE828%3E3.0.CO;2-W.

- Giannakis, Mihalis, and Nicola Bullivant. 2016. “The Massification of Higher Education in the UK: Aspects of Service Quality.” Journal of Further and Higher Education 40 (5): 630–48. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2014.1000280.

- Gujarati, Damodar N. 2003. Basic Econometrics. London/New York: McGraw-Hill.

- Gupta, Vishal K., Seonghee Han, Vikram Nanda, and Sabatino (Dino) Silveri. 2016. “When Crisis Knocks, Call a Powerful CEO (or Not): Investigating the Contingent Link Between CEO Power and Firm Performance During Industry Turmoil.” Group & Organization Management 43 (6): 971–98. https://doi.org/10.1177/1059601116671603.

- Hackman, Judith Dozier. 1985. “Power and Centrality in the Allocation of Resources in Colleges and Universities.” Administrative Science Quarterly 30 (1): 61. https://doi.org/10.2307/2392812.

- Hambrick, Donald C. 2007. “Upper Echelons Theory: An Update.” Academy of Management Review 32 (2): 334–43. https://doi.org/10.5465/amr.2007.24345254

- Hambrick, Donald C., and Phyllis A. Mason. 1984. “Upper Echelons: The Organization as a Reflection of Its Top Managers.” The Academy of Management Review 9 (2): 193–206. https://doi.org/10.2307/258434

- Han, Seonghee, Vikram K. Nanda, and Sabatino Dino Silveri. 2016. “CEO Power and Firm Performance Under Pressure.” Financial Management 45 (2): 369–400. https://doi.org/10.1111/fima.12127.

- Harjoto, Maretno A., and Hoje Jo. 2009. “CEO Power and Firm Performance: A Test of the Life-Cycle Theory*.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Financial Studies 38 (1): 35–66. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2041-6156.2009.tb00007.x.

- Harris, Dawn, and Constance E. Helfat. 1998. “CEO Duality, Succession, Capabilities and Agency Theory: Commentary and Research Agenda.” Strategic Management Journal 19 (9): 901–4. https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1097-0266(199809)19:9%3C901::AID-SMJ2%3E3.0.CO;2-V.

- Hazelkorn, Ellen. 2007. “The Impact of League Tables and Ranking Systems on Higher Education Decision Making.” Higher Education Management and Policy 19 (2): 1–24. https://doi.org/10.1787/hemp-v19-art12-en.

- Helfat, Constance E., and Jeffrey A. Martin. 2015. “Dynamic Managerial Capabilities.” Journal of Management 41 (5): 1281–312. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206314561301.

- Hillman, Nick. 2022. Digging In? The Changing Tenure of UK Vice-Chancellors. HEPI Policy Note 34. Oxford: ERIC.

- Hodgkinson, Gerard P, and Paul Sparrow. 2002. The Competent Organization: A Psychological Analysis of the Strategic Management Process. Buckingham: Open University Press.

- Hood, Christopher. 1991. “A Public Management for All Seasons.” Public Administration 69 (1): 3–19. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-9299.1991.tb00779.x.

- Hood, Christopher. 1995. “The “New Public Management” in the 1980s: Variations on a Theme” Accounting, Organizations and Society 20 (2-3): 93–109. https://doi.org/10.1016/0361-3682(93)E0001-W.

- Hutaibat, Khaled, Zaidoon Alhatabat, Larissa von Alberti-Alhtaybat, and Khaldoon Al-Htaybat. 2021. “Performance Habitus: Performance Management and Measurement in UK Higher Education.” Measuring Business Excellence 25 (2): 171–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/MBE-08-2019-0084.

- Johnes, Jill. 2006. “Data Envelopment Analysis and Its Application to the Measurement of Efficiency in Higher Education.” Economics of Education Review 25 (3): 273–88. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2005.02.005.

- Johnes, Jill, Maria Portela, and Emmanuel Thanassoulis. 2017. “Efficiency in Education.” Journal of the Operational Research Society 68 (4): 331–8. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41274-016-0109-z.

- Johnes, Jill, and Swati Virmani. 2020. “Chief Executive Pay in UK Higher Education: The Role of University Performance.” Annals of Operations Research 288 (2): 547–76. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10479-019-03275-2.

- Kakabadse, Andrew, F. Morais, A. Myers, and G. Brown. 2020. Universities Governance: A Risk of Imminent Collapse. Reading: Henley Business School.

- Kaplan, Steven N., Mark M. Klebanov, and Morten Sorensen. 2012. “Which CEO Characteristics and Abilities Matter?” The Journal of Finance 67 (3): 973–1007. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-6261.2012.01739.x.

- Khoo, Shee-Yee, Pietro Perotti, Thanos Verousis, and Richard Watermeyer. 2022. “Vice-Chancellor Narcissism and University Performance.” SSRN Electronic Journal. https://doi.org/10.2139/ssrn.4220887.

- Laureti, Tiziana, Luca Secondi, and Luigi Biggeri. 2014. “Measuring the Efficiency of Teaching Activities in Italian Universities: An Information Theoretic Approach.” Economics of Education Review 42 (October): 147–64. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.econedurev.2014.07.001.

- Lee, Boon L., and Andrew C. Worthington. 2016. “A Network DEA Quantity and Quality-Orientated Production Model: An Application to Australian University Research Services.” Omega 60 (April): 26–33. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.omega.2015.05.014.

- Liu, Lu, Xi Hong, Wen Wen, Zheping Xie, and Hamish Coates. 2020. “Global University President Leadership Characteristics and Dynamics.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (10): 2036–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2020.1823639.

- Lucey, Brian, Andrew Urquhart, and Hanxiong Zhang. 2022. “UK Vice-Chancellor Compensation: Do They Get What They Deserve?” The British Accounting Review 54 (4): 101108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2022.101108.

- Luo, Xueming, Vamsi K. Kanuri, and Michelle Andrews. 2014. “How Does CEO Tenure Matter? The Mediating Role of Firm-Employee and Firm-Customer Relationships.” Strategic Management Journal 35 (4): 492–511. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.2112.

- Lyons, Kristen, and Richard Hil. 2018. “Vice-Chancellors’ Salaries Are Just a Symptom of What’s Wrong with Universities.” The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/vice-chancellors-salaries-are-just-a-symptom-of-whats-wrong-with-universities-90999.

- Manner, Mikko H. 2010. “The Impact of CEO Characteristics on Corporate Social Performance.” Journal of Business Ethics 93 (S1): 53–72. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10551-010-0626-7.

- Marginson, Simon. 2004. “Competition and Markets in Higher Education: A ‘Glonacal’ Analysis.” Policy Futures in Education 2 (2): 175–244. https://doi.org/10.2304/pfie.2004.2.2.2.

- Melo, Ana Isabel, Cláudia S. Sarrico, and Zoe Radnor. 2010. “The Influence of Performance Management Systems on Key Actors in Universities.” Public Management Review 12 (2): 233–54. https://doi.org/10.1080/14719031003616479.

- Menz, Markus. 2012. “Functional Top Management Team Members.” Journal of Management 38 (1): 45–80. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206311421830.

- Miller, Danny, and Jamal Shamsie. 2001. “Learning Across the Life Cycle: Experimentation and Performance among the Hollywood Studio Heads.” Strategic Management Journal 22 (8): 725–45. https://doi.org/10.1002/smj.171.

- Mok, Ka Ho, and Deane Neubauer. 2016. “Higher Education Governance in Crisis: A Critical Reflection on the Massification of Higher Education, Graduate Employment and Social Mobility.” Journal of Education and Work 29 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/13639080.2015.1049023.

- Molesworth, Mike, Richard Scullion, and Elizabeth Nixon. 2010. The Marketisation of Higher Education. New York: Routledge.

- Naidoo, Rajani, and Joanna Williams. 2015. “The Neoliberal Regime in English Higher Education: Charters, Consumers and the Erosion of the Public Good.” Critical Studies in Education 56 (2): 208–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/17508487.2014.939098.

- Neely, Brett H., Jeffrey B. Lovelace, Amanda P. Cowen, and Nathan J. Hiller. 2020. “Metacritiques of Upper Echelons Theory: Verdicts and Recommendations for Future Research.” Journal of Management 46 (6): 1029. https://doi.org/10.1177/0149206320908640.

- Newton, David, Dimitrios Gounopoulos, Georgios Loukopoulos, and Victoria Patsika. 2019. “Chief Academic Officers’ Compensation and Universities’ Performance.” https://www.researchgate.net/publication/331572087_Chief_Academic_Officers'_Compensation_and_Universities'_Performance.

- Parry, Gareth, and Anne Thompson. 2002. Closer by Degrees: The Past, Present and Future of Higher Education in Further Education Colleges. London: Learning and Skills Development Agency.

- Pfeffer, Jeffrey. 1997. New Directions for Organization Theory: Problems and Prospects. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Pilonato, Silvia, and Patrizio Monfardini. 2020. “Performance Measurement Systems in Higher Education: How Levers of Control Reveal the Ambiguities of Reforms.” The British Accounting Review 52 (3): 100908. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bar.2020.100908.

- Pitcher, Patricia, and Anne D. Smith. 2001. “Top Management Team Heterogeneity: Personality, Power, and Proxies.” Organization Science 12 (1): 1–18. https://doi.org/10.1287/orsc.12.1.1.10120.

- Pollitt, Christopher, and Geert Bouckaert. 2017. Public Management Reform: A Comparative Analysis-Into the Age of Austerity. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Rabovsky, Thomas, and Amanda Rutherford. 2016. “The Politics of Higher Education: University President Ideology and External Networking.” Public Administration Review 76 (5): 764–77. https://doi.org/10.1111/puar.12529.

- Roodman, David. 2009. “A Note on the Theme of Too Many Instruments.” Oxford Bulletin of Economics and Statistics 71 (1): 135–58. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0084.2008.00542.x.

- Ruiz, José Rafael, José L. Segura, and Inmaculada Sirvent. 2015. “Benchmarking and Target Setting with Expert Preferences: An Application to the Evaluation of Educational Performance of Spanish Universities.” European Journal of Operational Research 242 (2): 594–605. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ejor.2014.10.014.

- Saidu, Sani. 2019. “CEO Characteristics and Firm Performance: Focus on Origin, Education and Ownership.” Journal of Global Entrepreneurship Research 9 (1). https://doi.org/10.1186/s40497-019-0153-7.

- Scullion, R., M. Molesworth, and E. Nixon. 2011. The Marketisation of Higher Education and the Student as Consumer. Abingdon: Routledge.

- Shahab, Yasir, Collins G. Ntim, Yugang Chen, Farid Ullah, Hai-Xia Li, and Zhiwei Ye. 2020. “Chief Executive Officer Attributes, Sustainable Performance, Environmental Performance, and Environmental Reporting: New Insights from Upper Echelons Perspective.” Business Strategy and the Environment 29 (1): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1002/bse.2345.

- Simar, Léopold, and Paul W. Wilson. 1998. “Sensitivity Analysis of Efficiency Scores: How to Bootstrap in Nonparametric Frontier Models.” Management Science 44 (1): 49–61. https://doi.org/10.1287/mnsc.44.1.49.

- Simar, Léopold, and Paul A Wilson. 2002. “Non-Parametric Tests of Returns to Scale.” European Journal of Operational Research 139 (1): 115–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0377-2217(01)00167-9.

- Tarbert, Heather, Kaihong Tee, and Robert Watson. 2008. “The Legitimacy of Pay and Performance Comparisons: An Analysis of UK University Vice Chancellors Pay Awards” British Journal of Industrial Relations 46 (4): 771–805. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8543.2008.00689.x.

- Tien, Chengli, Chien-Nan Chen, and Cheng-Min Chuang. 2013. “A Study of CEO Power, Pay Structure, and Firm Performance.” Journal of Management & Organization 19 (4): 424–53. https://doi.org/10.1017/jmo.2013.30.

- Tomlinson, Michael. 2017. “Student Perceptions of Themselves as ‘Consumers’ of Higher Education.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 38 (4): 450–67. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425692.2015.1113856.

- Witte, Kristof De, and Laura López-Torres. 2017. “Efficiency in Education: A Review of Literature and a Way Forward.” Journal of the Operational Research Society 68 (4): 339–63. https://doi.org/10.1057/jors.2015.92.

- Wulf, Torsten, Stubner Stephan, Miksche Jutta, and Roleder Kati. 2010. Performance Over the CEO Lifecycle. Leipzig: Leipzig Graduate School of Management.

- Yaisawarng, Suthathip, and Ying Chu Ng. 2014. “The Impact of Higher Education Reform on Research Performance of Chinese Universities.” China Economic Review 31: 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chieco.2014.08.006.

Appendices

Appendix A. The effect of power on efficiency and other variables (including VC Salary)

Appendix B. The effect of Power on bootstrapped efficiency and other variables (including VC Compensation).

Appendix C. The effect of Power on bootstrapped efficiency and other variables (including VC Salary).