ABSTRACT

Higher education plays a pivotal role in preparing students for the dynamic and complex labour market. Helping students develop employability competences supports them in obtaining the necessary expertise and skills to facilitate their transition to the labour market and to address the requirements of their new jobs. Employability competences are considered to contribute to students’ wellbeing and economic prosperity. Colleges and universities offer career coaching programmes to support students in developing their employability competences. Despite the importance of employability competences, empirical studies on the impact of such coaching programmes remain scarce. The present study aims to fill that gap by exploring the relationship between career coaching and the development of employability competences. A two-study design based on a multiple-methods approach was used to gain more insight in how coaching in higher education contributed to the development of students’ employability. Data were collected at institutions of higher education in the Netherlands and Belgium via student surveys (n = 491) and interviews with coaches (n = 9). Our quantitative data showed a significant positive relationship between coaches’ autonomy support and the development of students’ employability competences. The interviews provided in-depth detailed findings on how coaches support students in their learning process. Coaching sessions became most effective by encouraging students to engage in trial and error and by stimulating (self-) reflection. Taken together, our results show that (career) coaching in higher education has the potential to support students’ development of employability competences, which will, in turn, foster their transition to the workplace.

Introduction

Graduation serves for many as a moment for celebration. However, transitioning to the workplace as a graduate from higher education can be challenging. After graduation, students exchange the relatively stable and familiar context of higher education for the largely unknown and dynamic context of the workplace. The workplace is characterized by constant change due to rapid technological innovations, such as artificial intelligence, and employees must adapt quickly and cope with the continuous pressure to develop and perform (e.g. Suarta et al. Citation2017).

In preparing students for the workplace, higher education institutions are increasingly investing in the development of students’ employability (Harvey Citation2000; Knight and Yorke Citation2003). Employability refers to individuals’ ability to obtain and maintain a job after graduation (Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert Citation2020). However, measuring employability pertains to more than solely assessing whether a graduate managed to obtain a job. Essential competences are required for finding relevant jobs geared up to students’ specific interests and capabilities and organizational demands (Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert Citation2020; van Der Heijde and Van Der Heijden Citation2006). Not only does it require necessary domain-specific expertise in terms of job competences, but also generic competence, enabling graduates to act effectively in the social context of work and to take agency of their development (Dacre Pool and Sewell Citation2007; Tuononen et al. Citation2022; Yorke Citation2006). In the social context of work, graduate employees deal with uncertainties and typically, generic competences help graduates to deal with uncertainty, understand and manage teamwork, and communicate effectively with others. Generic competences are considered as necessary enablers for graduates to continually learn and develop in the workplace (Grosemans, Coertjens, and Kyndt Citation2017; Citation2020).

Higher education offers coaching programmes to prepare students for their transition to the workplace (van der Baan et al. Citation2022). Coaching is defined as formal process in which a coach fulfils a supportive role and encourages students’ learning and reflection (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009). In this supportive role, the coach provides multiple types of support, such as autonomy support, networking support, career support, emotional support, and psychosocial support (Nuis, Segers, and Beausaert Citation2023). The present study focuses specifically on career coaching to prepare students for their education-to-work transition, referring to supporting students in setting career goals and increasing their employability (Nuis, Segers, and Beausaert Citation2023; Renn et al. Citation2014).

Previous research showed that career coaching leads to a range of positive career-related outcomes, such as job search intentions and career planning (Ogbuanya and Chukwuedo Citation2017; Renn et al. Citation2014), and that career coaching increased students’ self-perceived employability (Pitan and Atiku Citation2017). The work of Gannon and Maher (Citation2012) shows that through reflection students can increase their employability. Reflection is a component of experiential career learning, and it reinforces and operationalizes learning experiences. For example, research shows that reflecting on previous learning experiences allows students to become aware of their own capabilities and set development goals to increase their employability (for examples and a discussion of career experiential activities see van Wart et al. Citation2020).

The aim of the present study is twofold. First, the present study examines the relationship between the types of coaching support and students’ employability competences. Second, this study explores how students perceive their learning behaviour after participating in coaching sessions aimed at improving their employability competences.

The present study uses a two-study design based on a multi-method approach. In the first quantitative study, we explore the relationship between career coaching in higher education and the development of students’ employability competences. In the second qualitative study, we research students’ learning as a result of these coaching practices, which might explain the why behind the relation studied in the first study. More specifically, the following research questions are introduced:

What is the relationship between coaching and employability competences?

How does coaching for employability competences shape students’ learning process?

Theoretical framework

Employability: a competence-based approach

Employability is defined as the ability to gain and maintain employment (Forrier and Sels Citation2003). Finding employment and moving self-sufficiently in the labour market requires not only subject knowledge, but also career management competences, such as the ability to identify job opportunities and to search for jobs (Dacre Pool and Sewell Citation2007; Hillage and Pollard Citation1998). Since HEIs prepare students for a dynamic workplace that is constantly changing and innovating, generic competences that are transferable across occupations are needed, such as e-literacy skills (Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert Citation2020). Research has also pointed out that employers frequently require these transferable generic competences (e.g. Braun and Brachem Citation2015). Moreover, graduate employees need to learn how to perform their new job tasks. Self-efficacy, defined as one's belief in one's own capability to perform certain tasks (Bandura Citation1977), is strongly linked with the concept of employability (Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert Citation2020; Wujema et al. Citation2022). In the employability literature, self-efficacy refers to individuals’ capability to maintain self-confidence in challenging work situations (Jackson Citation2014).

Once at the workplace and to maintain employment, graduates need to continue working on their employability (Römgens, Scoupe, and Beausaert Citation2020). For example, graduate employees need to continually update their knowledge base in order to cope with the frequent changes and innovations at the workplace, which also requires certain skills. For example, generic competences are important for engaging in workplace learning (Grosemans, Coertjens, and Kyndt Citation2020; Heijke, Meng, and Ris Citation2003). Moreover, a certain degree of flexibility is required to cope with changes at the workplace (van Der Heijde and Van Der Heijden Citation2006). In addition, it is pivotal for employees to keep a balance between private and working life. Work-life balance refers to the ability to balance multiple, seemingly opposite responsibilities. van Der Heijde and Van Der Heijden (Citation2006) defined balance as ‘compromising between opposing employers’ interests as well as one's own opposing work, career, and private interests’ (456). Taken together, these competences allow graduates to become and remain employable.

Experiential learning: (career) coaching for employability

Experiential learning theory (Kolb, Boyatzis, and Mainemelis Citation2014) can be used to study how students develop their employability by engaging in experiential learning and reflecting on their learning experiences (Gannon and Maher Citation2012; Van Wart et al. Citation2020). When learning from experiences, distinction can be made between reflection-on-action and reflection-beyond-action (Edwards Citation2017). The term reflection-on-action was coined by Donald Schön (Citation1987), to refer to reflecting on past experiences and reconstructing what happened. These kinds of ‘after-action accounts’ do not necessarily lead to new insights or critical consideration leading to future improvements. Whilst reflection-on-action refers to looking back to past experiences, reflection-beyond-action refers to looking forward (Edwards Citation2017). When reflecting-beyond-action, students distil learning lessons from their past experiences to improve and develop. The experiential learning theory stresses the importance of interventions that encourage and guide students in reflection about what they have learned or experienced. Coaching, especially career coaching, is considered to stimulate reflection (Devine, Meyers, and Houssemand Citation2013; van der Baan et al. Citation2022).

The International Coaching Federation defines coaching as a partnership with clients in a thought-provoking and creative process (International Coaching Federation Citation2023). Whereas in higher education, coaching is defined as a formal process in which a more experienced coach provides students with various types of support to facilitate students’ career development and employability (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009; Nuis, Segers, and Beausaert Citation2023; Renn et al. Citation2014). These definitions emphasize important elements of coaching processes and its outcomes. Foremost, they put forward the importance of the process itself to achieve provision of support conditions for students.

By providing autonomy support, the coach places the student at the centre of the decision-making process and encourages the student's proactive behaviour and ownership (Spence and Oades Citation2011). It is the student who ‘takes steps towards goal attainment and takes the initiative in the coaching conversation, while the coach provides the necessary supporting conditions for the coachee to take these steps’ (van der Baan et al. Citation2022, 410).

A coach provides the student with competence support. Competence support refers to creating a feeling of competence in the student (Spence and Oades Citation2011). Therefore, the coach focusses on the student's abilities and talents, rather than their weaknesses (Grant and O’Connor Citation2010). The coach assists students in setting learning goals and making an action plan. After the student engages in specific activities to work towards goal attainment, the coach helps the student to reflect on those activities by asking open, evaluative questions (van der Baan et al. Citation2022).

In networking support, coaches provide students with opportunities to build and broaden their own network. Coaches also can provide the student with access to their own network (Fullick et al. Citation2012).

Emotional support refers to sharing personal and professional issues with the coach. The coach actively listens and alleviates stress and anxiety by providing encouragement and support (Crawford, Randolph, and Yob Citation2014; Crisp and Cruz Citation2009).

To build a safe coaching environment, the coach provides psychosocial support. Conditions for psychosocial support include trustworthiness and approachability, a respectful relationship, and identification with the coach (Nuis, Segers, and Beausaert Citation2023). Trustworthiness and approachability refers to building trust between the student and the coach, in which the coach reserves time to talk to the student and is easily approachable (Crawford, Randolph, and Yob Citation2014; Gullan et al. Citation2016). A coach builds a respectful relationship with the student by, for example, recognizing and respecting the student's feelings and being discreet and transparent (Tenenbaum, Crosby, and Gliner Citation2001; van der Baan et al. Citation2022). Identification with the coach refers to the match between the coach and the student. Ideally, the coach is someone the student can identify with (Gullan et al. Citation2016; Molyn Citation2020; Tenenbaum, Crosby, and Gliner Citation2001).

Previous research has suggested that coaching can affect students’ employability competences and, in turn, facilitate their transition to the workplace (Gannon and Maher Citation2012). For example, the relationship between coaching and career development skills was found to be mediated by students’ efficacy beliefs (Ogbuanya and Chukwuedo Citation2017; Renn et al. Citation2014). Similarly, Molyn (Citation2020) suggested that coaching can increase students’ self-efficacy and employability efforts, to ensure lifelong learning. Furthermore, coaching can provide students with opportunities to enhance their social competences, by providing students with network opportunities and role models with whom the student can identify (Molyn Citation2020).

In addition, coaching is associated with the development of generic competences (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009; Gershenfeld Citation2014; Nuis, Segers, and Beausaert Citation2022), such as communication skills. A coach can provide students with opportunities to practice these skills under realistic work conditions (Wilhelm et al. Citation2002). Coaching also increases awareness of these skills. For example, in the study by Stigt et al. (Citation2018), the authors found that individual coaching sessions had a positive impact on the communication skills of medical residents and increased their awareness of the effect of their communication skills on others.

In sum, coaching is a multifaceted construct in which coaches provide students with multiple types of support to help students developing their employability. Providing these types of support allows for a personalized approach to learning.

Study 1: quantitative

In the first, quantitative part of this study, we aim to investigate the relationship between career coaching and employability to answer our first research question. The following hypothesis is presented:

Coaching, that is, particular types of support, is significantly positively related to the employability competences of students in higher education.

Method

Procedure and sample

Self-report surveys were digitally distributed to several study programme leaders and course coordinators at four higher education institutions in the Netherlands and Belgium (one university and three universities of applied sciences). These programme leaders and course coordinators were invited to distribute the questionnaires electronically among their students, because they were involved in study programmes that included a coaching trajectory for students. These coaching trajectories were mandatory for all students enrolled in these study programmes. The study programme leaders and teachers that distributed the questionnaires among their students were not necessarily coaches themselves. To ensure students filled in the questionnaire with their coach in mind, we explicitly asked them in the questionnaire to think of their coach. Coaches in these trajectories were teachers or other staff members within higher education institutions who coached students in their professional development. According to the definition of coaching in higher education, which is defined as a formal process in which a more experienced coach provides students with various types of support to facilitate students’ career development and employability, these teachers and staff members were considered coaches, although they were not certified coaches.

Students from three cohorts filled in the surveys. The surveys were distributed in the spring of academic years 2018–2019, 2019–2020, and 2020–2021. All students were participating in coaching programmes within their respective HEI aimed at facilitating their transition to the workplace. The coaching programmes were comparable in that sense that they had the same goal, namely supporting the development of students’ employability competences. Completing the survey was voluntary and anonymous (n = 485). summarizes the sample distribution.

Table 1. Sample distribution.

Measures

Employability

Students’ employability was measured with the Student's Employability Competence Questionnaire (SECQ) developed and validated by Scoupe, Römgens, and Beausaert (Citation2022). All subscales used 5-point Likert response scales, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree).

A measurement model with a second-order latent construct for employability was built. We decided to create a second-order latent construct for employability for several reasons. First, our research question focuses on the relation with employability and does not aim to study differentiating effects between employability components. Therefore, we aimed to make our path model more parsimonious. Second, to our knowledge, when studying the role of antecedents of employability, previous research (e.g. De Vos, De Hauw, and Van der Heijden Citation2011) measured employability as generic construct (for an overview, see Fugate et al. Citation2021). The measurement model showed an acceptable fit (χ2 = 2373.84, df = 1404, χ2/df = 1.69, CFI = 0.931, RMSEA [CI 90%] = 0.038 [0.035; 0.040]; Schreiber et al. Citation2006), indicating good construct validity. In addition, all individual employability competences showed significant factor loadings on the latent employability construct. The scale measuring employability had a Cronbach's alpha of .90, indicating good internal consistency (Tavakol and Dennick Citation2011; see ).

Table 2. Sample items and Cronbach's alphas.

Coaching

The validated Mentoring Support Scale from Nuis, Segers, and Beausaert (Citation2023) was used to measure students’ coaching experiences. All subscales used 5-point Likert response scales, ranging from 1 (completely disagree) to 5 (completely agree). Cronbach's alphas for the coaching subscales were all above .8, indicating good internal consistency within these subscales (Tavakol and Dennick Citation2011; ).

Analyses

First, a measurement model was built to conduct a confirmatory factor analysis (CFA) of all the latent factors (see the Appendix). Results revealed a satisfactory model fit (χ2 = 2373.84, df = 1404, χ2/df = 1.69, CFI = 0.931, RMSEA [CI 90%] = 0.038 [0.035; 0.040]; Schreiber et al. Citation2006), confirming the factor structure proposed by the validated questionnaires used in this study. In addition, we tested for common method bias using Harman's single factor. Common method bias can pose a threat to the research findings, especially with self-report data (Podsakoff et al. Citation2003). The analysis revealed that common method bias was not a cause for concern. Second, the assumption of normality was checked before conducting further analyses. The skewness and kurtosis statistics indicated that all scales were normally distributed. Third, preliminary analyses (descriptives and correlations) were conducted on all the variables under study. IBM SPSS Version 27 software package was used to perform all preliminary analyses. Fourth, a structural path model was built. Structural equation modelling (SEM) and maximum likelihood (ML) estimation was used to test the hypothesis. The structural path model was built in SPSS Amos, version 28.

Results

First, results of our preliminary analyses are shown in . Results of the correlation analysis revealed significant positive correlations between employability and the different types of coaching support. Composite reliability (CR) of each of the factors was satisfactory. In addition, we calculated the Average Variance Extracted (AVE) and the square root of the AVE (the diagonal in ), comparing the square root of the AVE with the correlation coefficients. According to the Fornell-Larcker criterion, the discriminant validity between the variables under study was no cause for concern (Fornell and Larcker Citation1981).

Table 3. Means (M), standard deviations (SD), composite reliability (CR), average variance extracted (AVE), square root of the AVE (the diagonal, in bold), and bivariate correlations for the variables under study (off-diagonal).

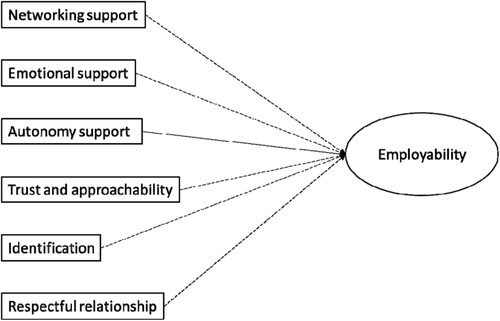

Second, a path model was built to examine the relationship between the career coaching support types and employability competences (). The structural path model demonstrated an excellent fit to our data (χ2 = 2373.84, df = 1404, χ2/df = 1.69, CFI = 0.931, RMSEA [CI 90%] = 0.038 [0.035; 0.040]; Schreiber et al. Citation2006). Results of this path model showed that only autonomy support was significantly positively related to the development of students’ employability competences, only partially confirming our hypothesis (β = .37, p < .05).

Study 2: qualitative

In the second, qualitative part of this study, we build further on our quantitative results and aim to explore how coaching stimulates the development of students’ employability and shape students’ learning processes, and answer our second research question:

How does coaching for employability competences shape students’ learning process?

Method

Procedure and sample

To explore students’ learning during coaching practices aimed at developing students’ employability competences, interviews were conducted. Coaches in higher education were invited to participate (n = 9; four from a university of applied sciences in Flanders, Belgium, five from a university in the Netherlands). Most participants had the Dutch or Belgian nationality. All coaching practices were aimed at supporting the development of students’ employability competences. Eight coaches also had teaching responsibilities in higher education while coaching students. One coach was working as student counsellor at a university. All coaches had 2–4 years of coaching experience. The interviews were conducted in Dutch or English and lasted approximately 30 minutes. The interviews were audio-recorded. Participation was voluntary. Informed consent was obtained in writing as well as verbally before the start of the recording. The interviews followed Critical Incident Technique (CIT), proposed by Flanagan (Citation1954). CIT is an exploratory method that allows the interviews to be flexible and focus on specific incidents brought up by the coaches themselves. An interview guideline with open-ended questions was developed. First, general information from our participants was asked, such as their job title and how many years they have been coaching students. Second, we asked the coaches to retrieve a critical incident and describe the situation in which they felt a student was learning in their coaching session. We asked the coaches what the student was learning and how they noticed the student was learning.

Analysis

To facilitate data analysis, the interviews were transcribed verbatim. The thematic approach proposed by Braun and Clarke (Citation2006) was used to code and analyse the interviews. The thematic approach allows sufficient flexibility and identification of themes in the data. On the one hand the interviews were deductively coded, based on our theoretical framework. On the other hand, interview segments that could not be coded based on theory were inductively assigned to a new code (see for the coding matrix). The unit of analysis, or meaningful units, consisted of sentence, multiple related sentences, or part of a sentence. Codes were categorized into two deductive themes based on our theoretical framework (1) students’ learning process and (2) coaching support. Atlas.ti version 9 was used to code the interviews. To facilitate co-occurrence analysis, multiple codes could be ascribed to quotes. For example, one quote could indicate more than one type of coaching support or more than one aspect of student learning. To check the inter-rater reliability, an independent researcher coded 10% of the interview transcripts. A satisfactory Cohen's kappa of .70 was reached.

Table 4. Coding matrix.

Results

Students’ learning process

Interviews showed that students learn in various ways, during and between coaching sessions. For example, students learn after engaging in trial-and-error (12 mentions). During trial-and-error students experiment and learn by doing. Coaches indicated that a positive experience (2 mentions) especially makes students learn.

In addition, coaches noticed students learning during their coaching session when they saw the students gain insights (12 mentions) or take notes (6 mentions) during the session itself:

I notice that a student is learning when they start writing things down and can work with them later. That, for example, indicates something like ‘ok, that is not how I looked at it before’ or ‘oh yes, that sounds so logical, but I never thought about it that way.’ With comments like this I know that a student really wants to get started with something new.

Coaches also mentioned that students engaged in three types of reflection during the coaching sessions: reflection-on-action, reflection-beyond-action, and self-reflection. During reflection-on-action (8 mentions), the student reflects on past actions and tries to learn from what happened during these actions. In reflection-beyond-action (7 mentions), the student, with help from the coach, goes further and starts to think about what to do differently in the future. During self-reflection (7 mentions) the student starts to question their own assumptions. One of the coaches commented:

You see them thinking, they are quiet for a while. And at some point, it is no longer the ready-made answers about themselves they gave in the beginning, but then it is more like ‘okay, that is also possible, I haven't seen it that way yet.’

Moreover, one coach mentioned a change in students’ body language (2 mentions) or facial expression as indicator of learning. For this coach, a change in students’ body language was the result of the student going through various emotions (4 mentions) during the coaching session, such as sadness or anger.

Coach support

During the coaching sessions, the coach provides students with different types of support, such as autonomy, networking, emotional, psychosocial, and competence support.

Frequency analysis revealed that coaches predominantly provided competence support (64 mentions) during the coaching sessions. When providing competence support, the coach ‘thinks along together with the student in terms of their learning goal’. For example, the coach assists the student with making an action plan, provides the student with tools and gives feedback, but the student themselves decide how to work towards goal attainment. With autonomy support (31 mentions), the coach focusses on the students’ needs and leaves the initiative to the student. However, as one coach mentioned, it is important to always provide the student with feedback.

Coaches also provide students with networking support (5 mentions). The coach can refer a student with a specific question to a third party or to peers. Coaches indicated that they refer students to peers because of their ‘equal status’. Students might be more comfortable sharing specific issues with peers, especially when the coach also assesses the student. Networking support also includes supporting the student in building their network and connecting the student with others.

Emotional support (24 mentions) involves giving the student affirmation that they are on the right track. However, a coach is also honest with the student:

Not always affirming. I think that sometimes we also dare to say ‘look, here it went wrong’ and discuss this as well.

A coach builds a safe coaching environment by building a respectful relationship (7 mentions) with the student by providing a listening ear, reserving time to listen to the student, and behaving transparently. Behaving transparently is especially important for coaches who have a dual role as coach and assessor:

I also always mentioned at certain moments ‘now I am your coach’ and when the coaching role stops ‘now I am your evaluator.’

Table 5. Frequency table for the codes.

On the role of coaching support for students’ learning process: a co-occurrence analysis

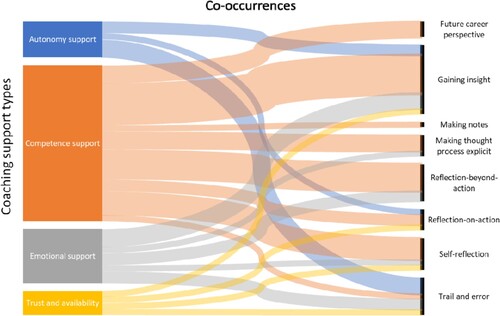

To answer the question of how coaching practice plays a role in students’ learning process, a co-occurrence analysis was performed between, on the one hand, types of coaching support, and on the other hand, aspects of students’ learning process during the coaching trajectory. Multiple codes assigned to one quote were seen as a co-occurrence. The number of co-occurrences is summarized in .

Table 6. Co-occurrence table for the types of coaching support and aspects of students’ learning process.

Competence support was most associated with students’ learning in and between the coaching sessions. When coaches said they provided competence support, they saw students reflecting during their coaching sessions in various ways: reflection-on-action and reflection-beyond-action, as well as self-reflection. When coaches said they provided competence support they saw students gaining insights, adopting a future career perspective, and making notes or making their thought process explicit.

Autonomy support was most often associated with students engaging in trial-and-error learning. In addition, coaches saw students gaining insights and engaging in reflection-on-action when they said they provided autonomy support.

Emotional support, and trust and approachability, as part of psychosocial support, were mentioned together with various aspects of students’ learning process. Providing emotional support was associated with gaining insight and making thought processes explicit. Emotional support was mentioned together with reflection-beyond-action, self-reflection, and trial-and-error learning. Trust and approachability was mentioned together with gaining insights, students’ reflection-on-action, self-reflection, and trial-and-error learning.

Results of this co-occurrence analysis are visualized in .

Discussion

The aim of the present study was to explore the role of (career) coaching practices in the development of students’ employability competences. The present study used a two-study design to answer two separate but complementary research questions. A quantitative and qualitative study were used in a sequential manner to provide more insights into how coaching contributed to students’ employability. First, a quantitative study based on a student survey was conducted to investigate the relationship between the various types of coaching support (i.e. autonomy support, personal support, emotional support, networking support, trust and approachability, respectful relationship, and identification with the coach) and students’ employability competences. Second, interviews with coaches were used to go beyond the statistics and to gain more insight into how coaching for employability competences shapes students’ learning process.

Results of our quantitative study revealed a significant positive relationship between autonomy support and students’ employability competences, partially confirming our hypothesis; the more autonomy support is offered, the higher students’ level of employability competences. This is in line with previous research suggesting that autonomy support is pivotal for engaging in learning activities (Spence and Oades Citation2011). These authors suggested that creating a feeling of autonomy will increase students’ willingness to act and make decisions, which makes them more ‘apt to learn and apply new strategies and competences’ (44).

Network support, emotional support, and the three aspects of psychosocial support (trust and availability, respectful relationship, and identification) were not related to students’ employability. Network support refers to the coach providing students with opportunities to build and broaden their own network. Networking with others is pivotal when searching for a job and may predict later career success of graduate employees (Higgins and Kram Citation2001; Renn et al. Citation2014). A large professional network gives students access to potential employers and information that can help them in their job search, but does not directly affect their employability, which refers to students’ internal resources and potential to gain and maintain employment after graduation (Batistic and Tymon, Citation2017; Fugate et al. Citation2021). Next, emotional and psychosocial support create a safe coaching environment and form the foundation for providing other support types that facilitate the development of students’ employability.

Our qualitative results showed that several of these types of coaching support types were mentioned together with students’ learning process during coaching sessions aimed at improving students’ employability competences.

Results of our qualitative study and co-occurrence analysis (see and ) showed that providing autonomy support was related to students’ trial-and-error learning. By focussing on the autonomous motivation and needs of the student, the coach provides the student with sufficient freedom and autonomy to experiment with different learning activities that relate to their learning goal (Jang, Reeve, and Deci Citation2010). In the interviews, one coach pointed out that the best feedback students can get is experiencing for themselves what works and what does not. This process of trial-and-error also shows parallels with experiential learning theory (Kolb, Boyatzis, and Mainemelis Citation2014). Experiential learning theory states that individuals learn through experiences and reflecting on those experiences. However, as one of the coaches indicated in the interviews, students do not automatically reflect on their experiences.

Results of the present study suggest that a coach can support students in their reflection by providing competence support. This result is in line with previous research which suggested that competence support from a coach is able to stimulate students’ reflection (van der Baan et al. Citation2022). More specifically, our results suggest that coaches who provide competence support especially stimulate students’ reflection-beyond-action. This result suggests that students might be capable of looking back and creating these ‘after-the-fact’ accounts themselves, but they need the support of a coach to be able to look forward and reflect on how their learning experiences helped them develop and improve (Edwards Citation2017). In addition, our results indicate that competence support from a coach helps students adopt a future perspective. Thus, it is not enough to provide students only with autonomy support for the development of their employability competences. To encourage students in their learning process, specifically their reflection, coaches also provide competence support. It is suggested that reflection is the main mechanism for developing employability competences, as reflection helps students to become and remain aware of their employability competences (Moon Citation2004).

Furthermore, emotional support and, trust and approachability were found to be related to several learning activities, such as trial and error and reflection. Emotional support provides students with a feeling of safety (Crisp and Cruz Citation2009; Nuis, Segers, and Beausaert Citation2022). Providing the student with emotional support, especially in the form of affirmation, can also increase students’ self-efficacy (van Dinther, Dochy, and Segers Citation2011). Self-efficacy, as the belief in their own capabilities, increases students’ motivation and willingness to engage in learning activities, such as trial-and-error (Bandura Citation1977). Trust and approachability refers to feelings of trust between the coach and the student. In addition, the student feels that the coach is available and approachable, and that they can fall back on the coach for guidance and advice. Emotional support and trust and approachability may provide students with a safety net for experimenting with different learning activities.

Emotional support and trust and approachability were also found to be related to students’ reflection. Reflection, and especially self-reflection in which students question their own assumptions, is not always easy. Students might shy away from self-reflection, as they ‘fear that it will destroy their mode of professional survival’ (Moon Citation2004, 12) and challenge their identity. Gelfuso and Dennis (Citation2014) suggested that reflection will not take place in the absence of support structures. Emotional support might be such a support structure. By providing emotional support, a coach creates a safe environment for students to reflect in. Trust and approachability assure the student that the coach will be available when the reflecting activities unearth unforeseen issues. Thus, trust and approachability and emotional support are not directly related to students’ employability competences, but rather provide the necessary conditions to engage in activities to develop employability competences.

Networking support, identification with the coach, and a respectful relationship did not show a relation with students’ employability competences or their learning process. However, this does not mean that these coaching dimensions are not important. For example, a coach providing networking supports refers students to third parties when students have questions outside the coach's field of expertise and connects the student with others (Nuis, Segers, and Beausaert Citation2022). It is therefore possible that networking support is not related to students’ learning process during coaching sessions. Instead, networking support might facilitate students’ learning outside the coaching sessions.

Identification with the coach and a respectful relationship were also not found to be mentioned together with the various aspects of students’ learning process. Identification with the coach and a respectful relationship, as part of psychosocial support, refer to how students perceive the coach. Because we interviewed coaches, it was not possible to establish links between these forms of psychosocial support and students’ learning process.

In conclusion, the present study shows that (career) coaching in higher education is a valuable pedagogical intervention to support students in the development of their employability competences and their learning process, and, in turn, will facilitate their transition to the workplace.

Limitations and recommendations for future research

Although the present study provides evidence for (career) coaching as a pedagogical intervention to improve students’ employability competences, along with insights into students’ learning process during these coaching sessions, several limitations can be identified.

First, quantitative data included self-reports about students’ employability competences, which could lead to more socially desirable answers. Students could, for example, rate their employability competences high because they liked the coach or were afraid of being assessed on those competences, even though data collection was anonymous.

Second, given that we wanted to associate the various coaching support types with students’ employability, we worked with a generic latent construct for employability. It is recommended that in future research, attention is directed towards the effects of (career) coaching on distinct employability competences. Moreover, to trace the effect of (career) coaching on the development of students’ employability competences, it is recommended that researchers conduct longitudinal studies.

Third, to explore students’ learning process, we conducted interviews with coaches about students’ learning process. Although the coaches might have a good understanding of when a student learned during the coaching sessions, it would be valuable to include the student perspective in future research by interviewing students who were coached or observing coaching sessions. In addition, by interviewing coaches, our insights into students’ learning process were restricted to what happens during the coaching sessions. As one of our interviewees mentioned, most learning happens outside the coaching sessions. To gain insight into students’ learning journey between coaching sessions, it is recommended that future research include longitudinal case studies.

Fourth, in the present study, there was a disconnect in the data obtained from the students and the coaches. Future research could include dyadic pairs of coach and student data to get a complete picture about how coaches support students in developing their employability.

Fifth, the match between the coach and coachee can influence the relationship and consequently the learning outcomes. The similarity between the coach and coachee is argued to be a strong predictor of the quality of the coach-coachee relationship (Nuis, Segers, and Beausaert Citation2023). However, research also suggests that learning opportunities might get lost when coach and coachee are similar because the coachee might not get exposed to different perspectives (Froehlich, Beausaert, and Segers Citation2021). Future research could study the role of matching between coach and coachee and its influence on the coachee's learning and development.

Sixth, although quantitative data were collected from multiple cohorts, most data was collected during the COVID-19 pandemic. During the pandemic, all coaching sessions were conducted online, which may have impeded students’ learning process. In addition, qualitative data were collected during the aftermath of the COVID-19 pandemic. During the interviews, we asked coaches about critical incidents. It remained unclear if coaches were describing incidents from coaching sessions that were conducted online or face-to-face coaching sessions. It is recommended that when conducting similar research in the future, online and face-to-face coaching sessions are distinguished.

Seventh, only undergraduate students were included in our sample. Future research could include graduate and professional students, doctoral and postdoctoral students in their sample to provide evidence for the generalizability of our findings.

Finally, as coaching definitions differ in different contexts and sometimes lack specificity, future research could investigate the specificity of coaching in different contexts and educational levels.

Practical implications

Results of the present study show that (career) coaching is a valuable pedagogical intervention to support students in the development of their employability competences. During the coaching sessions, students learn to develop their employability in various ways. By providing the right types of support, coaches can assist students in their learning process.

First, results show that coaches providing autonomy support can support students in increasing their employability. By providing autonomy support and putting the student at the centre of the decision-making process, the coach can stimulate students to engage in trial-and-error learning. At the same time, coaches should provide emotional support by affirming and validating students’ feelings, to let the student feel sufficiently safe to engage in different learning activities to work towards goal attainment. In addition, the coach needs to invest in building a relationship of trust with the student by reserving time for the student and being readily available.

Second, coaches can stimulate various aspects of students learning process by providing competence support. For example, coaches should ask reflective questions to encourage students to reflect. More specifically, coaches can encourage students to take a future perspective and stimulate their reflection-beyond-action.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data can be made available upon request to the corresponding author.

References

- Bandura, Albert. 1977. “Self-Efficacy: Toward a Unifying Theory of Behavioral Change.” Psychological Review 84 (2): 191–215.

- Batistic, Saša, and Alex Tymon. 2017. “Networking Behaviour, Graduate Employability: A Social Capital Perspective.” Education Training 59 (4): 374–388. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-06-2016-0100.

- Braun, Edith M. P., and Julia-Carolin Brachem. 2015. “Requirements Higher Education Graduates Meet on the Labor Market.” Peabody Journal of Education 90 (4): 574–95. https://doi.org/10.1080/0161956X.2015.1068086.

- Braun, Virginia, and Victoria Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Crawford, Linda M., Justus J. Randolph, and Iris M. Yob. 2014. “Theoretical Development, Factorial Validity, and Reliability of the Online Graduate Mentoring Scale.” Mentoring and Tutoring: Partnership in Learning 22 (1): 20–37. https://doi.org/10.1080/13611267.2014.882603.

- Crisp, Gloria, and Irene Cruz. 2009. “Mentoring College Students: A Critical Review of the Literature between 1990 and 2007.” Research in Higher Education 50 (6): 525–45. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11162-009-9130-2.

- Dacre Pool, Lorraine, and Peter Sewell. 2007. “The Key to Employability: Developing a Practical Model of Graduate Employability.” Education and Training 49 (4): 277–89. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400910710754435.

- Devine, Mary, Raymond Meyers, and Claude Houssemand. 2013. “How Can Coaching Make a Positive Impact Within Educational Settings?” Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences 93: 1382–9. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2013.10.048.

- De Vos, Ans, Sara De Hauw, and Beatrice I.J.M. Van der Heijden. 2011. “Competency Development and Career Success: The Mediating Role of Employability.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 79 (2): 438–47. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2011.05.010.

- Edwards, Sharon. 2017. “Reflecting Differently. New Dimensions: Reflection-before-Action and Reflection-beyond-Action.” International Practice Development Journal 7 (1): 1–14. https://doi.org/10.19043/ipdj.71.002.

- Flanagan, John C. 1954. “The Critical Incident Technique.” Psychological Bulletin 51 (4): 327–58. https://doi.org/10.1037/h0061470.

- Fornell, Claes, and David F. Larcker. 1981. “Evaluating Structural Equation Models with Unobservable Variables and Measurement Error.” Journal of Marketing Research 18 (1): 39–50. https://doi.org/10.1177/002224378101800104.

- Forrier, Anneleen, and Luc Sels. 2003. “The Concept Employability: A Complex Mosaic.” International Journal of Human Resources Development and Management 3: 102–24.

- Froehlich, Dominik E., Simon Beausaert, and Mien Segers. 2021. “Similarity-Attraction Theory and Feedback-Seeking Behavior at Work: How Do They Impact Employability?” Studia paedagogica 26 (2): 77–96. https://doi.org/10.5817/SP2021-2-4.

- Fugate, Mel, Beatrice Van der Heijden, Ans De Vos, Anneleen Forrier, and Nele De Cuyper. 2021. “Is What’s Past Prologue? A Review and Agenda for Contemporary Employability Research.” Academy of Management Annals 15 (1): 266–98. https://doi.org/10.5465/annals.2018.0171.

- Fullick, Julia M., Kimberly A. Smith-Jentsch, Charyl Staci Yarbrough, and Shannon A. Scielzo. 2012. “Mentor and Protégé Goal Orientations as Predictors of Newcomer Stress.” Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning 12 (1): 59–73.

- Gannon, Judie M., and Angela Maher. 2012. “Developing Tomorrow’s Talent: The Case of an Undergraduate Mentoring Programme.” Education + Training 54 (6): 440–55. https://doi.org/10.1108/00400911211254244.

- Gelfuso, Andrea, and Danielle V. Dennis. 2014. “Getting Reflection off the Page: The Challenges of Developing Support Structures for Pre-Service Teacher Reflection.” Teaching and Teacher Education 38: 1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2013.10.012.

- Gershenfeld, Susan. 2014. “A Review of Undergraduate Mentoring Programs.” Review of Educational Research 84 (3): 365–91. https://doi.org/10.3102/0034654313520512.

- Grant, Anthony M., and Sean A. O’Connor. 2010. “The Differential Effects of Solution-focused and Problem-focused Coaching Questions: A Pilot Study with Implications for Practice.” Industrial and Commercial Training 42 (2): 102–11. https://doi.org/10.1108/00197851011026090.

- Grosemans, Ilke, Liesje Coertjens, and Eva Kyndt. 2017. “Exploring Learning and Fit in the Transition from Higher Education to the Labour Market: A Systematic Review.” Educational Research Review 21: 67–84.

- Grosemans, Ilke, Liesje Coertjens, and Eva Kyndt. 2020. “Work-related Learning in the Transition from Higher Education to Work: The Role of the Development of Self-efficacy and Achievement Goals.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 90 (1): 19–42. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12258.

- Gullan, Rebecca Lakin, Kathleen Bauer, Pierre Korfiatis, Jennifer DeOliveira, Kelsey Blong, and Meagan Docherty. 2016. “Development of a Quantitative Measure of the Mentorship Experience in College Students.” Journal of College Student Development 57 (8): 1049–55.

- Harvey, Lee. 2000. “New Realities: The Relationship Between Higher Education and Employment.” Tertiary Education and Management 6: 3–17.

- Heijke, Hans, Christoph Meng, and Catherine Ris. 2003. “Fitting to the Job: The Role of Generic and Vocational Competencies in Adjustment and Performance.” Labour Economics 10 (2): 215–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0927-5371(03)00013-7.

- Higgins, Monica C., and Kathy E. Kram. 2001. “Reconceptualizing Mentoring at Work: A Developmental Network Perspective.” The Academy of Management Review 26 (2): 264–88. https://doi.org/10.2307/259122.

- Hillage, Jim, and Emma Pollard. 1998. Employability: Developing a Framework for Policy Analysis. London: DfEE.

- International Coaching Federation. 2023. Available at: https://coachingfederation.org.

- Jackson, Denise. 2014. “Testing a Model of Undergraduate Competence in Employability Skills and Its Implications for Stakeholders.” Journal of Education and Work 27 (2): 220–42.

- Jang, Hyungshim, Johnmarshall Reeve, and Edward L. Deci. 2010. “Engaging Students in Learning Activities: It Is Not Autonomy Support or Structure but Autonomy Support and Structure.” Journal of Educational Psychology 102 (3): 588–600. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0019682.

- Knight, Peter T., and Mantz Yorke. 2003. “Employability and Good Learning in Higher Education.” Teaching in Higher Education 8 (1): 3–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/1356251032000052294.

- Kolb, David A., Richard E. Boyatzis, and Charalampos Mainemelis. 2014. “Experiential Learning Theory: Previous Research and New Directions.” In Perspectives on Thinking, Learning, and Cognitive Styles, edited by Rober J. Sternberg and Li-Fang Zhang, 227–48. New York: Routledge.

- Molyn, Joanna. 2020. “The Role and Effectiveness of Coaching in Increasing Self-Efficacy and Employability Efforts of Higher Education Students.” In Proceedings of the MIT LINC 2019 Conference, edited by Claudia Urrea, 178–67. Cambridge, MA: Eric Education Science.

- Moon, Jenny. 2004. Reflection & Employability. York, UK: Learning and Teaching Support Centre.

- Nuis, Wendy, Mien S. R. Segers, and Simon Beausaert. 2022. “Conceptualizing Mentoring in Higher Education: A Systematic Literature Review.” Educational Research Review 41: 100565. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2023.100565.

- Nuis, Wendy, Mien S. R. Segers, and Simon Beausaert. 2023. “Development and Validation of an Instrument for Measuring Mentoring in Higher Education.” Higher Education, https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-023-01042-8.

- Ogbuanya, Theresa Chinyere, and Samson Onyeluka Chukwuedo. 2017. “Career-Training Mentorship Intervention via the Dreyfus Model: Implication for Career Behaviors and Practical Skills Acquisition in Vocational Electronic Technology.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 103 (August): 88–105. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2017.09.002.

- Pitan, Oluyomi Susan, and Sulaiman Olusegun Atiku. 2017. “Structural Determinants of Students’ Employability: Influence of Career Guidance Activities.” South African Journal of Education 37 (4): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v37n4a1424.

- Podsakoff, Philip M., Scott B. MacKenzie, Jeong-Yeon Lee, and Nathan P. Podsakoff. 2003. “Common Method Biases in Behavioral Research: A Critical Review of the Literature and Recommended Remedies.” Journal of Applied Psychology 88 (5): 879–903.

- Renn, Robert W., Robert Steinbauer, Robert Taylor, and Daniel Detwiler. 2014. “School-to-Work Transition: Mentor Career Support and Student Career Planning, Job Search Intentions, and Self-Defeating Job Search Behavior.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 85 (3): 422–32. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2014.09.004.

- Römgens, Inge, Rémi Scoupe, and Simon Beausaert. 2020. “Unraveling the Concept of Employability, Bringing Together Research on Employability in Higher Education and the Workplace.” Studies in Higher Education 45 (12): 2588–603. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1623770.

- Schön, Donald A. 1987. Educating the Reflective Practitioner: Toward a New Design for Teaching and Learning in the Professions. Hoboken, NJ: Jossey-Bass.

- Schreiber, James B., Amaury Nora, Frances K. Stage, Elizabeth A. Barlow, and Jamie King. 2006. “Reporting Structural Equation Modeling and Confirmatory Factor Analysis Results: A Review.” The Journal of Educational Research 99 (6): 323–38. https://doi.org/10.3200/JOER.99.6.323-338.

- Scoupe, Rémi, Inge Römgens, and Simon Beausaert. 2022. “The Development and Validation of the Student’s Employability Competences Questionnaire (SECQ).” Education + Training 88–105. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-12-2020-0379.

- Spence, Gordon B., and Lindsay G. Oades. 2011. “Coaching with Self-Determination in Mind: Using Theory to Advance Evidence-Based Coaching Practice.” International Journal of Evidence Based Coaching and Mentoring 9: 37–55.

- Stigt, Jos A., Janine H. Koele, Paul L. P. Brand, Debbie A. C. Jaarsma, and Irene A. Slootweg. 2018. “Workplace Mentoring of Residents in Generic Competencies by an Independent Coach.” Perspectives on Medical Education 7 (5): 337–41. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-018-0452-7.

- Suarta, I Made, I. Ketut Suwintana, I. G. P. Fajar Pranadi Sudhana, and Ni Kadek Dessy Hariyanti. 2017. “Employability Skills Required by the 21st Century Workplace: A Literature Review of Labor Market Demand.” In 337–42. Atlantis Press.

- Tavakol, Mohsen, and Reg Dennick. 2011. “Making Sense of Cronbach’s Alpha.” International Journal of Medical Education 2: 53–5.

- Tenenbaum, Harriet R., Faye J. Crosby, and Melissa D. Gliner. 2001. “Mentoring Relationships in Graduate School.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 59 (3): 326–41.

- Tuononen, Tarja, Heidi Hyytinen, Katri Kleemola, Telle Hailikari, Iina Männikkö, and Auli Toom. 2022. “Systematic Review of Learning Generic Skills in Higher Education—Enhancing and Impeding Factors.” Frontiers in Education 7 (May): 1–13. https://doi.org/10.3389/feduc.2022.885917.

- van der Baan, Niels, Inken Gast, Wim Gijselaers, and Simon Beausaert. 2022. “Coaching to Prepare Students for Their School-to-Work Transition: Conceptualizing Core Coaching Competences.” Education + Training 64 (3): 398–415. https://doi.org/10.1108/ET-11-2020-0341.

- van Der Heijde, Claudia M., and Beatrice I. J. M. Van Der Heijden. 2006. “A Competence-Based and Multidimensional Operationalization and Measurement of Employability.” Human Resource Management 45 (3): 449–76. https://doi.org/10.1002/hrm.20119.

- van Dinther, Mart, Filip Dochy, and Mien Segers. 2011. “Factors Affecting Students’ Self-Efficacy in Higher Education.” Educational Research Review 6 (2): 95–108. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.10.003.

- van Wart, Audra, Theresa C. O’Brien, Susi Varvayanis, Janet Alder, Jennifer Greenier, Rebekah L. Layton, C. Abigail Stayart, Inge Wefes, and Ashley E. Brady. 2020. “Applying Experiential Learning to Career Development Training for Biomedical Graduate Students and Postdocs: Perspectives on Program Development and Design.” Edited by Rebecca Price. CBE—Life Sciences Education 19 (3): es7. https://doi.org/10.1187/cbe.19-12-0270

- Wilhelm, William J., Joyce Logan, Sheila M. Smith, and Linda F. Szul. 2002. Meeting the Demand: Teaching ‘Soft’ Skills. Little Rock, AR: Delta Pi Epsilon.

- Wujema, Baba Kachalla, Roziah Mohd Rasdi, Zeinab Zaremohzzabieh, and Seyedali Ahrari. 2022. “The Role of Self-Efficacy as a Mediating Variable in CareerEDGE Employability Model: The Context of Undergraduate Employability in the North-East Region of Nigeria.” Sustainability 14 (8): 1–16. https://doi.org/10.3390/su14084660.

- Yorke, Mantz. 2006. Employability in Higher Education: What It Is-What It Is Not. Vol. 1. York: York Higher Education Academy.

Appendix: Measurement model.