Abstract

Financial transactions data are increasingly considered valuable in the context of security threats, yet they are particularly privacy sensitive. At present, 166 Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) worldwide are able to share financial intelligence via the Egmont Group, their joint platform. This paper analyses the politics and practices of transnational financial intelligence sharing, with a particular emphasis on the Egmont Group. We draw on literatures at the intersection between political economy and financial security to analyse how FIU practitioners rely on what we call ‘circuits of trust’ that enable them to engage in a politics of data-sharing. Drawing on semi-structured interviews and participant observation, we examine three practices: the role of trust in navigating the ‘legal grey zone’ in which FIU data are shared; the way in which trust circuits make intelligence sharing possible; and the implicit notions of (un)trustworthiness at work when FIUs share intelligence, leading to inclusion and exclusion. We aim to push forward the conversation about economic trust practices by observing how the circuit of trust operates in everyday practice, making the sharing of financial intelligence (im)possible.

Introduction: The Egmont Group

Trust is an essential component of the Egmont Group. The Egmont Group builds trust among its members by promoting and holding firm on FIUs’ integrity, transparency and accountability. Any abuse of FIU powers compromises trust and is detrimental to the credibility of our global network. (Chair of the Egmont Group, Egmont Group, Citation2021b)

In March 2021, the Chair of the Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs) released a statement addressing ‘allegations of FIUs misusing their powers to combat ML [money laundering] and TF [terrorist financing]’ (Egmont Group, Citation2021b). The statement acknowledges that certain FIUs misuse their institutional powers by ‘coercing civil society actors for [their] critiques of current governments in their jurisdictions’ (Egmont Group, Citation2021b). FIUs are relatively new security actors that analyse financial transactions in the context of suspected money laundering or terrorist financing. Banks, but also other financial intermediaries such as money transmitters, are obliged by law to report unusual financial behaviour of their customers to the national FIU. The FIU analyses these reports, conducts additional research, and can share the intelligence with the police authorities, investigative services or the prosecution. The Egmont Group provides a global platform for FIUs to cooperate, share expertise and intelligence.

In the Egmont Group statement, it is acknowledged that the considerable powers that FIUs have gained as security actors, can be used to suppress nongovernmental organizations (NGOs) and/or government-critical groups. As such, it was a rare public acknowledgement of the politics of financial intelligence sharing, and a demonstration that these considerable intelligence-sharing powers can be abused. This paper takes as a starting point that the politics of financial intelligence sharing are at play not merely in the ‘misuse’ of FIU powers, but more widely in the ways that FIUs gather, analyse and share financial intelligence across borders. Despite the existence of some international agreements, financial intelligence sharing takes place largely on the basis of mutual trust and personal connections. It is important to draw out more clearly the politics and powers of FIUs and their international cooperation, especially because financial intelligence includes information about individuals who have not been officially charged or formally named suspects in a crime. Crucially, FIUs possess and share extensive personal financial data on citizen subjects who are unaware that their data are being gathered and circulated. This raises legal, ethical and privacy concerns.

This paper maps and analyses the politics of making financial intelligence shareable, with particular emphasis on the practices and circuits of trust. As demonstrated by Amicelle and Chaudieu (Citation2018), FIUs increasingly share financial intelligence with counterparts around the globe, pushing the legal and practical boundaries of international data sharing for security purposes. This paper examines the political stakes that arise in practices of sharing intelligence through the Egmont Group. Egmont Group members include countries with questionable reputations concerning human rights, such as Syria, Saudi Arabia, Venezuela, Egypt and Belarus.Footnote1 As is increasingly recognized in the academic literature, data do not simply ‘flow’ across institutions and jurisdictions; rather, it takes hard work and complex technical and juridical processes to render data and (personal) information mobile across boundaries (Bellanova & de Goede, Citation2022; Gitelman & Jackson, Citation2013). This paper asks: What are the practical means and networks through which FIU intelligence and data are made sharable?Footnote2 How are investigative files and personal data rendered mobile across jurisdictions, and what are the political challenges and obstacles? What role do informal practices and circuits of trust play in making sensitive financial data and transactions internationally shareable?

This paper builds on literature in the broad realms of political economy and financial security, to enquire into the practices of transnational financial intelligence sharing, which is an overlooked but particularly important type of data sharing. Literatures in financial surveillance and security indicate that financial transactions data are increasingly inscribed with the potential to identify suspicious behaviours in the context of crime and terrorism financing (Amicelle, Citation2011; Amoore & de Goede, Citation2008; Westermeier, Citation2020). FIUs are key in this regard and operate as brokers that receive, analyse and disseminate financial data within a wider ‘chain of security’ (de Goede, Citation2018). In this chain, transaction reports are shared between commercial actors such as banks (Bosma, Citation2019; Iafolla, Citation2018) and the FIU (Lagerwaard, Citation2022), to eventually – sometimes – be used as evidence in a court of law (Anwar, Citation2020). With some important exceptions, including Amicelle and Chaudieu’s (Citation2018, p. 650) study of the ‘devices’ and ‘channels’ that FIUs use for transnational cooperation (see also Amicelle & Faravel-Garrigues, Citation2012), there is a lack of academic study of this type of financial surveillance and of FIU cooperation in particular.

This paper focuses on what we call ‘circuits of trust’, and the role these play in FIU intelligence-sharing practices. Results from fieldwork suggest that transnational financial intelligence sharing does not depend only on technical platforms and structures, but that transnational professional networks and relations of trust are important. This paper draws on the work of Zelizer (Citation2006) who has challenged the notion of financial markets as impersonal, and has shown that ‘social circuits’ play a crucial role in the functioning of modern money and credit forms. According to Zelizer (Citation2004, p. 124), ‘careful observers of [economic] institutions always report the presence, and often the wild profusion, of intimate ties in their midst’. Building on the work of Zelizer, this paper develops the notion of ‘circuits of trust’ to analyse how trust renders the transnational circulation of financial intelligence possible. Financial intelligence sharing depends on social practices and informal trust relations, and involves mundane political decisions about understandings of which counterparts are ‘trustworthy’ and ‘untrustworthy’.

The paper is structured as follows. The first two sections discuss literatures on political economy and financial security and provide more context on the Egmont Group and the challenges of transnational financial data sharing. Subsequently, the paper analyses three practices of sharing intelligence: first, how trust enables FIUs to navigate the legal grey zones of financial intelligence sharing; second, how circuits of trust materialize and are vital in making intelligence shareable; and third, how processes of inclusion and exclusion in trust circuits connect to political deliberations on the ‘trustworthiness’ and ‘untrustworthiness’ of counterparts. The conclusion of the paper draws out questions of accountability that need to be the subject of future research.

Trust practices in financial security

In order to examine the role of trust in transnational financial intelligence sharing through the Egmont Group, this section discusses literatures in the broad realms of financial security and political economy. Literatures on ‘financial security’ demonstrate that financial practices and (state) security are historically and ontologically intertwined (Boy et al., Citation2017; Boy & Gabor, Citation2019; de Goede, Citation2010; Langenohl, Citation2017; Langley, Citation2017). This literature pays attention to the use of finance as a geopolitical tool and ‘weapon of war’ (Gilbert, Citation2015). Within this literature, the study of laws and practices of anti-money laundering (AML) and counterterrorism financing (CFT) has become a special focus, because these are clearly practices where security politics interact with financial interests in complex ways (Amicelle, Citation2017; de Goede, Citation2012). This literature has analysed CFT as a ground for new types of public–private data sharing at the limits of law (Bures & Carrapico, Citation2018; Wesseling, Citation2013). In particular, the financial security literature has focused on the everyday, routine practices through which professional groups, like lawyers and bankers, enact regulation and share financial transaction data across public and private spheres (Amicelle & Jacobsen, Citation2016; de Goede, Citation2018; Helgesson & Mörth, Citation2019).

The financial security literature has focused primarily on ‘high-tech’ modes of data sharing and algorithmic transactions analysis, paying less attention to seemingly ‘low-tech’ methods, such as personal connections and communications (Bonelli & Ragazzi, Citation2014). However, as Baird (Citation2017, p. 199) concludes based on immersive studies of security fairs, physical encounters of security practitioners are crucial sites where security knowledge is ‘produced, conveyed, circulated [and] consumed’ (see also Hoijtink, Citation2019). Similarly, in transnational financial intelligence sharing, ‘low-tech’ practices, like informal acquaintances, mutual trust, personal meetings and phone calls, seem to be crucial when FIUs cooperate.

Literatures focusing on transnational AML/CFT governance have focused on the increasing prominence of private actors (Liss & Sharman, Citation2015) and the power of the ‘soft law’ of transnational organizations, such as the Financial Action Task Force (FATF) (Heng & McDonagh, Citation2008; Sharman, Citation2009), but only sparsely on the role of trust. We suggest that understanding the role of trust in the seemingly high-tech worlds of transnational financial intelligence sharing is important, and can be analysed through what we call ‘circuits of trust’. The cultural political economy literature has theorized on the role of trust in financial practices, demonstrating that seemingly global and footloose financial markets depend on interpersonal relations and shared cultural practices (Ho, Citation2009; Pryke, Citation2010; Siu, Citation2010). For example, Leyshon and Thrift (Citation1997) have theorized the cultivation of trust in the City of London that is maintained through informal circuits and ways of dress, and ‘backed up by abstract expert systems’ (p. 56). Trust has become more important – not less so – as financial trading has grown more abstract, technology-dependent and complex (Balázs, Citation2020; Ho, Citation2009).

These insights into financial market practices build on a larger sociological literature on trust/distrust in disembedded and abstract economic markets (Cook et al., Citation2005; Searle et al., Citation2018; Sitkin & Bijlsma-Frankema, Citation2018). Trust is understood as a ‘device’ that allows humans to deal with ‘indeterminacy and interdependence’ (Olsen, Citation2008, p. 2190). Trust has been characterized as a dynamic reciprocal process, a ‘bidirectional phenomenon wherein each party is mutually influenced by the other’s cooperation and trust’ (Sitkin & Bijlsma-Frankema, Citation2018, p. 73). De Wilde (Citation2020, p. 2) shows that trust is especially important when economic markets are opaque and economic goods are ‘multidimensional’ and ‘incommensurable’. Trust is a ‘socio-technical’ arrangement, for de Wilde (Citation2020, p. 564), that is never stable but requires ‘shared and local work of arranging, modulating and mending relationships’. In opaque or uncertain market conditions, ‘reliance on others’ becomes of key importance as economic participants search for ‘judgement devices’ on what to buy or how to invest (see also Hoffman, Citation2002; Koole, Citation2020; Versloot, Citation2022). Taken together, this literature confirms that trust becomes more important as markets and economic processes become more complex, risky and abstract (MacKenzie, Citation2001).

We suggest that the politics of financial intelligence sharing can be analysed through the lens of what we call ‘circuits of trust’. This approach draws on Zelizer (Citation2004, pp. 124–125), who offered the term ‘circuits of commerce’ to theorize the social relations of ‘conversation, interchange, … and mutual shaping’ that play a key role in practices of commerce and credit. Zelizer (Citation2004, p. 125) theorizes circuits of commerce as ‘dynamic, meaningful, incessantly negotiated interactions’ between intimate sites such as the household, and formal economic practices and institutions. According to Zelizer (Citation2004, p. 124), ‘each distinctive social circuit incorporates somewhat different understandings, practices, information, obligations, rights, symbols, and media of exchange’ (see also Zelizer, Citation2006). In other words, a circuit is understood as a bounded social realm with shared practices of meaning-making concerning obligations, worthiness, rights and symbols, and with its own media.

Circuits of trust is a useful term to capture the transnational network of FIUs, as organized through the Egmont Group. The Egmont Group facilitates socio-technical data-sharing practices as well as series of formal and informal meetings at which personal contacts are fostered and maintained. AML/CFT circuits are typified by a large measure of uncertainty concerning trends and methods on terrorism financing and money laundering, which means that participants rely on others to make sense of a complex and uncertain environment. Reliable and shared knowledge concerning suspect profiles and suspicious patterns is often lacking, and there are little to no harmonized reliable indicators (Aradau, Citation2017; Lagerwaard, Citation2020). In the face of deep uncertainties over the merits and effectiveness of AML/CFT practices and procedures, participants look to each other to make sense of trends and technologies and to receive and disseminate financial intelligence. This is underscored by the Egmont Group itself calling trust an ‘essential component’ of its operations, the loss of which would be ‘detrimental to the credibility of the global network’ (Egmont Group, Citation2021b).

Transnational financial intelligence sharing

This section further introduces the Egmont Group and situates its role in transnational financial intelligence sharing. As a growing literature shows, the ways in which data are made intelligible and rendered sharable across jurisdictions are never neutral but entail complex political choices (Amoore, Citation2013). Data never simply ‘flow’ but have to be made mobile across jurisdictions and technical systems and legal regimes (Bellanova & de Goede, Citation2022). A substantial literature has analysed systems and practices of ‘data-led’ security, based on commercial data including airline passenger name records and wire transfers (SWIFT) (Amoore, Citation2013; Bellanova, Citation2017; Fahey & Curtin, Citation2014). This literature has analysed the systems and scale by which commercial airline and financial data are captured and mined by security authorities, raising questions concerning the legal protections and privacy implications of such transnational data sharing (Mitsilegas, Citation2014). Yet, according to Ferrari (Citation2020, p. 522), financial data are particularly privacy-sensitive because they reveal ‘information about individuals’ activities, purchases and geographical movements’, which can be used to derive ‘sexual orientation, health status, religious and political beliefs’.

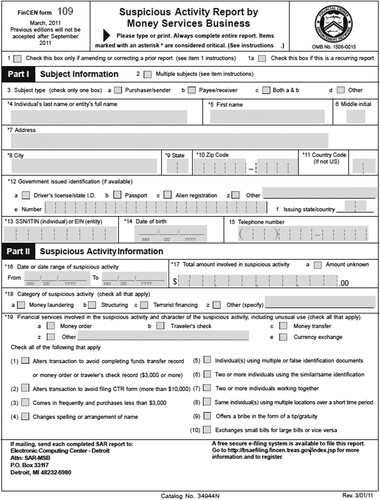

FIU intelligence sharing differs from existing data-led transnational security programmes in that it is less systematic, less ‘high tech’, and arguably, less visible to date. The reports that commercial financial actors submit to FIUs entail sensitive personal data and narrative descriptions of suspicions. By way of example, shows the first page of a suspicious activity report (SAR) used by FinCEN, the FIU of the United States. Part I, ‘subject information’, includes personal data such as first and last names, address, date of birth, telephone number and proof of identification (e.g. driving license number). Part II is the suspicious activity information, which includes narrative details on the nature of the suspicion, documentation of the alleged unusual character of the transaction and details about the movement of the transaction.Footnote3

Figure 1 FinCEN SAR example

Source: https://www.templateroller.com/template/525333/fincen-form-109-suspicious-activity-report-by-money-services-business.html (retrieved 31 May 2022).

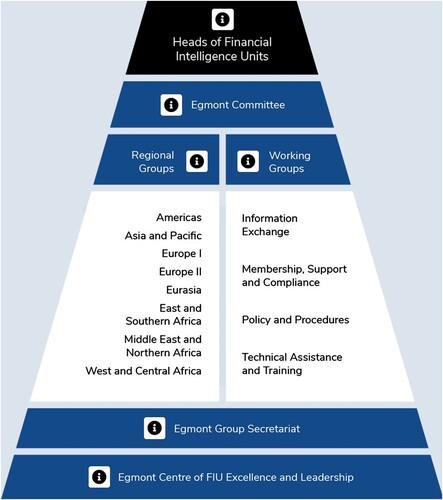

The Egmont Group network allows a SAR, such as shown in , to be shared internationally. The Egmont Group is an informal international platform divided into eight regional groupings that align with the regional bodies of the FATF, which is the intergovernmental organization that sets the standards of global financial surveillance (Nance, Citation2018). The Egmont Group has a largely decentralized structure (see ). Its sharing of information, expertise and intelligence is not codified in legal treaties but works through best practice guidance, technical assistance and circuits of trust. It was formed in 1995, receiving its name from the location where the 24 founding FIUs had gathered: the Egmont Palace in Brussels, Belgium. The platform has grown to 166 members at the time of writing, with a secretariat based in Ontario, Canada. The organization is funded by annual member contributions (calculated on the basis of GDP and GDP per capita), alongside additional voluntary contributions from members and observers (Egmont, Citation2019, pp. 27–28). Its highest body is the Heads of FIUs (HoFIUs), composed of the directors of the national FIUs. Below it is the Egmont Committee, which includes a chair and vice-chair position, which are filled on a rotational basis by the HoFIUs and includes representatives of the eight regional bodies. In addition, the Egmont Group has a learning centre, called ECOFEL, which assists FIUs by sharing expertise and best practices.

Figure 2 The Egmont Group’s composition

Source: Egmont (Citation2022a)

According to the Egmont Group, ‘[the] sharing of financial intelligence is of paramount importance and has become the cornerstone of the international efforts to counter Money Laundering [and] Terrorism Financing’ (Egmont Group, Citation2022b). Egmont Group members commit to sharing intelligence as freely as possible, both ‘spontaneously’, and through cooperation when a foreign FIU makes an information request (Egmont, Citation2013). The Egmont Secure Web (ESW) is the technology that enables practitioners to engage in everyday communications and to share intelligence via encrypted e-mails. While the secretariat is based in Ontario, the ESW is hosted by FinCEN, the FIU of the United States, and is based in the suburbs of Washington, DC. In 2017–2018, the ESW recorded 22,532 intelligence exchanges between FIU members; in 2019, this number rose to 25,301 exchanges (Egmont Group, Citation2018, Citation2021a). Each exchange can entail hundreds of actual reports.

The Egmont Group encourages members to ‘check the ESW daily, especially to ensure urgent requests are suitably addressed’ (Egmont Group, Citation2017, p. 4). By keeping the ESW relatively low-tech, the threshold for different types of FIUs to join and share financial intelligence is low. According to some practitioners, the ESW is a very simple system of exchange and can be considered a ‘glorified email system’ (FIU employee, 26 December 2017). Some FIUs make use of highly advanced technologies to gather and analyse data, while others continue to rely mainly on manual processing of (paper) transaction reports, and hardly work with digital reporting. Among these latter are particularly FIUs that operate in cash economies and have few digital transactions available to analyse. By remaining relatively low tech, the ESW allows the diversity of FIUs to connect on an everyday basis.

Financial intelligence sharing: Three practices

This paper asks about the everyday practices and politics of rendering financial intelligence sharing possible, addressing the question of how FIUs maintain relationships of trust with counterpart FIUs, even if each must adhere to different regulatory and legal frameworks and have conflicting political stakes and interests. In the following three empirical sections three practices are examined that were inductively identified through fieldwork. First, we discuss the international legal agreements and relations that enable FIU data sharing. These are shown to create ‘a legal grey zone’ in which circuits of trust play a key role. Second, we examine how circuits of trust materialize and how they foster informal relations that enable the sharing of sensitive financial data. The focus here is the international conferences and platforms where financial intelligence professionals meet and where interpersonal connections are fostered. Third, we discuss practices of inclusion and exclusion in circuits of trust that operate on implicit notions of counterparts’ ‘trustworthiness’ or ‘untrustworthiness’. Circuits of trust are not a stable given but involve a politics of (dis)trust that might fail or break down.

Our inductive analysis draws on methods of participant observation in the circuit of semi-scientific gatherings on counterterrorist financing and anti-money laundering as panelist, observer and moderator.Footnote4 It also draws on extensive document analysis of publicly available documents from transnational organizations, including the Egmont Group and national FIUs, which publish annual reports with the numbers of suspicious transactions they receive, analyse and disseminate. In addition, interviews were conducted in the field of financial intelligence broadly defined, with subjects ranging from bankers to lawyers and regulators, at different institutional levels. Among these, the most important data were derived from 13 interviews with FIU employees.Footnote5 Due to the often-sensitive nature of the discussions, comments made by the respondents were anonymized and measures were taken to prevent even indirect recognition.

Trust to navigate the legal grey zone

FIUs are encouraged to ensure that national legal standards do not inhibit the exchange of information between or among FIUs. (Egmont Group, Citation2017, p. 3)

This section examines the international landscape of legal agreements and relations that form the basis of FIU data sharing. It demonstrates that in intelligence sharing, FIUs operate in a legal grey zone, which makes the role of circuits of trust particularly important. The Egmont Group quote above states that individual FIUs are encouraged to operate at the limits of national law when sharing intelligence with other Egmont Group members. Yet, the Egmont Group’s 166 member FIUs abide by different national and regional legal frameworks, regarding for instance privacy, data handling and banking regulations (Mouzakiti, Citation2020). Importantly, because FIUs operate under such different regimes, intelligence might travel from a region with strict privacy or banking regulations, to another region without such regulation, raising the question of which laws and standards then apply to any intelligence that is shared.

Consequently, FIU practitioners face a significant juridical and operational puzzle when sharing intelligence, that derives from a plurality of regulations, guidelines and laws in effect in different places. On the global stage, the FATF is the most authoritative intergovernmental body. However, the FATF lacks the power to enforce its recommendations nationally. Instead, it relies on regional bodies and a system of mutual evaluations (Nance, Citation2018). This results in countries interpreting and translating the FATF recommendations differently. For instance, the EU has translated the FATF recommendations into its Anti-Money Laundering Directive, which has been adjusted multiple times since its first implementation in 1991 and is currently in its sixth version. An EU directive is binding in its goal, yet countries are allowed to decide how the goal is to be translated into national legislation and accomplished. Countries around the world translate global and regional frameworks into legislation that might differ in terms of banking regulations, privacy, data sharing and even issues of human rights. In sum, countries implement loosely defined ‘recommendations’ (FATF, Citation2022) or ‘principles’ (Egmont Group, Citation2017), which are not legally binding in their own jurisdictions. Transnational cooperation to counterterrorist financing and money laundering is therefore marked by informal global governance arrangements.

FIUs navigate this sensitive legal grey zone by relying on circuits of trust, and loosely structured informal relations. The importance of trust is officially drafted as part of the Egmont Group Charter, which prescribes that ‘effective international cooperation between and among FIUs must be based on a foundation of mutual trust’ (Egmont Group, Citation2019, p. 4; see also the Egmont Group, Citation2013, p. 3). As discussed, the international governance of the Egmont Group is in the hands of the HoFIUs group:

The Heads of FIU (HoFIU) are the Egmont Group’s main governing body. The HoFIU make consensus-driven decisions on matters affecting membership, structure, budget and key principles. The HoFIU communicate regularly through the Egmont Secure Web and meet at least once a year during the Annual Egmont Group Plenary meeting. (Egmont Group, Citation2022a)

The international relations connecting HoFIUs and the governance of the Egmont Group are partly encoded in official documents, yet there are no binding regulations that obligate HoFIUs to participate in the Egmont Group, let alone to share their intelligence. The fundament of international cooperation is personal acquaintanceship – and consensus – among the HoFIUs.

Circuits of trust are fostered through the personal connections between HoFIUs and their closely connected personnel working on foreign affairs. The actual sharing of intelligence, too, takes place on the basis of informal agreements rather than legal procedures. Instead of formal mutual legal assistance (MLA) requests, often FIUs first shared their intelligence informally, requesting formal permission for its use only afterwards, if the data appeared to be valuable. An example is provided by the comment below, made by a former HoFIU in response to a question on the importance of trust:

[Trust is important b]ecause of the informal nature of contacts between FIUs. So it’s an intelligence based [system]. It’s not, it doesn’t involve the mutual legal system … [For] FIUs, the rules are … more lax, I would say. It’s for intelligence purposes only. So if there’s a real investigation afterwards, then there will be MLA [mutual legal assistance] anyway, so everything will be checked. But for now, just queries like ‘do you know this person’ and ‘is there information about this person’. So, sometimes it’s exchanging STRs or sensitive information, and sometimes it’s just assisting with even open-source information. (Former HoFIU, 6 September 2018)

This suggests that in the case of FIUs, the process of using foreign intelligence legally for domestic investigations or in a court of law is reversed. First, the intelligence is shared on the basis of trust and in the confidence that it will be used ‘for intelligence purposes only’, thus remaining behind closed FIU doors. If it proves to be important, for instance as key evidence in a criminal investigation, then the official legal permission is requested from the counterpart FIU (FIU employee, 17 January 2019).

Like the FATF, the Egmont Group lacks the ‘hard’ power to oblige (Ho)FIUs to share intelligence, meaning that in practice national FIUs remain in full possession of their own data, including their SARs. This leaves space for FIUs to independently navigate and decide when, how and what kind of financial intelligence they share with foreign counterparts. It is precisely in the context of the legal grey zone, that the circuits of trust are built, maintained and mobilized, so as to navigate the plurality of possibly conflicting legal frameworks. Trust in the counterpart provides some form of informal, unofficial safeguard against misuse, that is not always warranted, as we will observe below. Moreover, the significant role of trust in navigating the legal grey zone and bringing about global sharing of financial intelligence is widely acknowledged by the practitioners themselves. As the Head of the Egmont Group stated in response to the allegation that FIUs had misused their powers:

these deeply concerning allegations pertain to FIUs limiting or coercing civil society actors for their work and critiques of current governments in their jurisdictions … Any abuse of FIU powers compromises trust and is detrimental to the credibility of our global network. (quoted in Vedrenne, Citation2021)

Making intelligence shareable through trust

The previous section argued that FIUs operate in a legal grey zone, which leaves space to independently decide what kind of intelligence to share with counterparts. This section explores how the circuit of trust materializes in practice via various types of events. Following de Wilde (Citation2020), we understand trust not just as a social bond but as a ‘socio-technical’ arrangement that requires practical work and material platforms. With regard to terrorism financing and money laundering, there is a fast-growing circuit of events, conferences, workshops, seminars, webinars and symposia at which financial professionals and security practitioners meet and interact. These events range from the annual Egmont Group Plenary to private events, such as the Association of Certified Anti-Money Laundering Specialists (ACAMS) and academic events, such as the Cambridge International Symposium on Economic Crime. Workshops and webinars have titles such as ‘Illicit financial flows: Assessing the need for new approaches’ and ‘Unexplained wealth: Whose business?’ Participating in these events is costly. The ACAMS Annual conference cost $1,085 (public sector rate) and the Cambridge Symposium on Economic Crime cost £2,400, to which expenditures for accommodation and dinners must be added. To some extent then, the events themselves generate the circuit in a material infrastructural sense; they provide a sense of exclusiveness of the circuit, as well as a shared ‘ingroup’ feeling.

The Cambridge Symposium is an example of a large event where trust is fostered across a wide spectrum of financial intelligence actors. The conference is organized by the University of Cambridge and attended by more than 2,000 participants from over 100 countries.Footnote6 Over the course of eight days it provides 120 sessions – mainly workshops and individual speakers – and gathers more than 650 experts from the financial intelligence field. Beyond FIU employees, participants include bankers, law enforcement officials, law firms, representatives of NGOs, consulting firms, public prosecution services, politicians, secret services and (global) governance agencies, such as the FATF. Trust is not an official part of the programme, but in practice, speakers and the workshops recurrently signal the importance of trusting fellow practitioners. Trust building was put into practice during networking opportunities, including cocktail parties and dinners, at which attendees exchanged business cards and reconnect with acquaintances.

The importance of such, often physical, gatherings in generating trust among practitioners is widely acknowledged. Consider, for instance, the following conversation with a former HoFIU, offering an apt illustration of the significance of the Egmont Plenary:

Well the Egmont Group is fantastic. It’s the best cocktail party in town.

Interviewer: At the moment or before?

Respondent: It always has been, it always will be. Because they meet in the most exotic places. … And for many years there wasn’t much coming out of Egmont. I think now it is quite a bit more substance. But even assuming there’s no substance it’s just a good cocktail party. It has a lot of value because you meet people, shake hands, you look people in the eye, and then, trust is gained. (Former HoFIU, 6 September 2018)

You go to other countries, for me to go to the Netherlands,Footnote7 I don’t know how to go to the company registry of Netherlands. It’s a different language. You call the FIU, ‘Can you help me?’. ‘Yes, sure’, … ‘by the way we also have two [SARs], and we have some information’. So this very informal way actually turns out to be very, very useful . … Egmont Group can be criticized for being a cocktail party, not doing much, but even as such, I claim, many cases I can remember, … I could call … and I can say ‘Hey, George, how are you doing? Remember, we had fun together last week? Can you help me on this case? It’s really important’. ‘Sure, I can look into it’. (Former HoFIU, 6 September 2018)

The relationships of trust that are generated at these types of conferences, often develop on the basis of reciprocity. According to Cook et al. (Citation2005, p. 2), ‘a trust relation emerges out of mutual interdependence and the knowledge developed over time of reciprocal trustworthiness’. Given that FIUs have contradictory interests – being simultaneously dependent on the intelligence of others while seeking to protect their own sensitive data – reciprocity becomes an important concept around which delicate political decisions are made. The Egmont Charter, for instance, reads that ‘[a]ll members foster the widest possible co-operation and exchange of information with other Egmont Group FIUs on the basis of reciprocity or mutual agreement’ (Egmont Group, Citation2019, p. 8).

How reciprocity plays out in practice is demonstrated by the following response of another HoFIU when asked whether they exchanged data differently with FIUs outside of the EU:

Yes, yes, of course we make, well, of course we do not carry out extensive analysis [of the other FIUs] because the membership to the Egmont Group somehow provides reassurance. But we have conditions in our law, for example, about confidentiality and reciprocity, which are very common conditions worldwide. So we can only provide information to FIUs that are, you know, that commit to keep that information confidential and abide by the conditions that we might indicate. (FIU employee, 6 February 2020)

This interviewee considered membership of the Egmont Group as providing reassurance, and also mentioned that reciprocity between FIUs does not necessarily refer to an equal exchange of data – a balanced or equal ‘weight’ or ‘worth’ of the intelligence exchange – but rather to the extent that the FIUs trust each other to share sensitive data. Practices of trust and reciprocity provide reassurance that in the absence of a shared legal framework the intelligence will be handled with care and confidentiality. Overton (Citation1999, p. 40) also observes that reciprocity does not necessarily mean an equal relationship of trust; it may involve unequal relationships in which some parties have more influence than others.

FIUs in countries with questionable reputations concerning human rights are members of the Egmont Group and can become part of the circuit of trust, as we will analyse in the next section. Indeed, these FIUs are considered important because they have access to valuable intelligence from their respective jurisdictions, which otherwise would be difficult or impossible to acquire. From an intelligence perspective, it is beneficial to have as many FIUs as possible as part of the circuit, as this expands the global pool of accessible intelligence. Take for instance the following quote from an FIU employee:

[W]e used to say in Egmont … it is better to have bad FIUs on board, than have them outside the system. For example, if I may refer to some FIUs, some offshore FIUs, sometimes they might provide valuable information … which we are investigating and which may have accounts for companies offshore … [A]lthough this may be a little sketchy, still it is very important, for example, for us and for prosecutors in [country] to understand if there is an account in, say, the Cayman Islands. (FIU employee, 6 February 2020)

Being part of the transnational circuit of trust is therefore key for an individual FIU to gain access to and tap into a wealth of data from around the globe. However, to achieve this, the FIU must become part of the circuit of trust and join the growing circuit of events, workshops and other, often physical, gatherings and relations. Practitioners such as HoFIUs need to be part of the transnational circuit. They need to be present to look other practitioners ‘in the eye’, and engage in reciprocal relations of data sharing. This includes FIUs that ‘may be a little sketchy’ (FIU employee, 6 February 2020).

Inclusion and exclusion: The politics of (dis)trust

The previous section analysed how trust materializes in practice as a fundamental component of the global operations of the Egmont Group. This section shows that this also involves a delicate politics of (dis)trust, especially because FIUs have considerable autonomy to independently decide with whom (not) to share financial intelligence. We argue that this political dimension of transnational financial intelligence sharing involves a process of inclusion and exclusion. Following Zelizer (Citation2004, p. 125), economic circuits ‘imply the presence of an institutional structure that reinforces credit, trust, and reciprocity’. This means that a circuit of trust requires work to operate and maintain. Informal circuits are not stable and static, but are prone to blockages and delays, and may even break down (see also Bellanova & de Goede, Citation2022). This section focuses on the politics of sharing financial intelligence through circuits of trust, and the concomitant importance of trustworthiness/untrustworthiness.

The autonomous nature of FIUs grants them considerable power to independently decide with whom to share information, without governmental interference. In fact, FIUs are granted this autonomy in order to safeguard against governmental interference and the potential misuse of financial intelligence by, for instance, autocratic regimes. For instance, the 28th FATF recommendation reads as follows:

The FIU should be able to obtain and deploy the resources needed to carry out its functions, on an individual or routine basis, free from any undue political, government or industry influence or interference, which might compromise its operational independence. (FATF, Citation2020a, p. 103)

On the one hand, this independence functions as a safeguard when FIUs share intelligence with ‘sketchy’ counterparts because FIUs from ‘questionable’ countries are expected to be separated from government and therefore protected against external interference. It is for this reason that FIUs are often viewed by the wider financial security field as peculiar organizations, in that they tend to be more loyal to each other than to their respective governments (Think tank practitioner, 16 October 2020). On the other hand, this principle of operational independence and autonomy vests considerable political power and responsibility in the hands of the FIUs, that is not always warranted.

As mentioned in the introduction, the Egmont Group recently issued a warning about potential abuses of FIU power (Egmont Group, Citation2021b). This warning referred to recent cases in which FIUs allegedly abused their powers. Two of these cases are relatively well documented. The first case concerns the FIU of Uganda, the Financial Intelligence Authority (FIA). In December 2020, a few months before the country’s elections, the FIA ordered the freezing of four bank accounts belonging to civil society actors that were ‘involved in good governance and election observation in the country’ (Draku, Citation2020). The FIA has the authority to freeze bank accounts – a power not shared by all FIUs. It froze, among others, the accounts of the National NGO Forum, which is an umbrella organization including more than 650 organizations (Issa, Citation2021). Following a political controversy in which the FIA was accused of misusing the money laundering and counterterrorist financing regulations for the political purposes of the ruling party, and following pressure by the United States and European Union (The Independent, Citation2021), the FIA reversed its decision and released the accounts. However, this occurred only in February 2021, after the elections (Kazibwe, Citation2021). This example demonstrates that an FIU, despite its (desired) autonomy and independence, can be mobilized by governments for coercion of civil society in political struggles.

A second example concerns the FIU of Serbia, called the Administration for the Prevention of Money Laundering (APML). In this case, intelligence was shared by the FIU for questionable purposes. Specifically, in July 2020, APML requested commercial banks to provide detailed information on Serbian civil society and media subjects, basing the request on Serbia’s Law on the Prevention of Money Laundering and the Financing of Terrorism. In response, 270 civil society actors and media representatives issued a joint statement proclaiming that they would ‘not give up the fight for a democratic and free Serbia’.Footnote8 The UN Human Rights Office warned that ‘Serbia’s anti-terrorism laws [are] being used to target and curb work of NGOs’. Even the FATF responded, stating that it ‘shares the concerns regarding the allegations that Serbia misused its Law … with the aim to restrict or coerce civil society actors for their work and criticism of the government’ (FATF, Citation2020b). In this case, furthermore, the Serbian government explicitly acknowledged that the APML was actively gathering information from foreign FIUs on national subjects. It stated that ‘in the course of its work, APML has collected information on the cases which involved government officials, including ministers currently in office, using its powers to obtain information from foreign FIUs’ (Permanent Mission of the Republic of Serbia to the United Nations, Citation2020). Information that is shared between FIUs, this example shows, can be put to use for purposes that do not adhere to the standards of the FIU that initially provided the information, possibly conflicting with privacy standards but also, potentially, human rights.

Both examples demonstrate that individual FIUs make delicate political decisions about with whom to engage in reciprocal relations and data sharing because these data might become ‘complicit’ in domestic political decisions and the undermining of civil society. One FIU employee noted that if they determined that another FIU had been deployed for domestic political purposes, they would stop sharing data with the FIU: it would be excluded on the basis of distrust. Such a breakdown of trust was described as follows.

There have been cases of leaks of information, of very confidential information, provided on suspicious cases and on individuals which were leaked in foreign countries for political purposes, for example, because the guy which was being analyzed or investigated was the former prime minister or the current prime minister. Therefore, the FIU was actually used as a conduit to, you know, in the context of political struggles there. You provided information, and then the day after you saw in the newspaper that the information had been leaked to the press. So [it] is … very unfortunate to have the trust compromised. I mean, of course, next time you won’t accept to, you know, share information with that FIU. So that is why trust is essential. (FIU employee, 6 February 2020)

If trust breaks down because an FIU has used the shared information for domestic political purposes, then the exchange of financial intelligence can come to a halt. This has less to do with technicalities, legal regulations or whether the Egmont Charter has or has not been signed, and more to do with the everyday practice and politics of sharing financial intelligence through circuits of trust. As the quote above shows, the politics of trust or distrust do not necessarily relate to whether an FIU is located in a county where human rights abuses take place but relate to the question of whether an FIU is considered ‘a bad apple’ and whether it has taken adequate care of the sensitive financial information it has been given access to.

The uneasy inclusion of the Syrian FIU under the Assad regime in the transnational circuit of trust presents a final interesting example of how delicate this politics of (dis)trust and inclusion/exclusion is. Syria has been an Egmont Group member since 2007, and has remained included, to different degrees, in the FIU circuit of trust during the civil war.Footnote9 While the regime’s use of chemical weapons on its population led to the severance of diplomatic relations between European countries and the Assad regime, the Syrian FIU remained a member of the Egmont Group. Initially, the Syrian FIU was suspended from participating in the circuit of events and, for instance, was not welcome to participate in the annual Egmont Plenary. However, after nine years of suspension, a delegation of the Syrian FIU was again invited to the Egmont Plenary in 2019 in The Hague, the Netherlands (Rasha, Citation2019).

Furthermore, during the Syrian civil war and despite the known human rights abuses by the Assad government, Syria continued working with the FATF to address and repair its FATF ‘non-compliant’ rating, stemming from the 2006 mutual evaluation. This means that the international community encouraged and compelled the Syrian government to adopt or strengthen laws that criminalize terrorism financing and money laundering, to expand the list of predicate offences to money laundering and terrorism financing, to enhance customer surveillance of banking clients and to strengthen customer identification requirements – while Assad’s atrocities against his own population were ongoing. In 2016, for instance, the Syrian FIU placed 12 requests to Egmont Group FIUs asking for assistance, and received in turn 22 requests via the Egmont Group (Lababidi, Citation2020, p. 165). The 2018 FATF follow-up evaluation report approvingly notes that prosecutions for terrorism financing in Syria increased from 21 in 2013 to 174 in 2016. This is worrying, especially considering the potential for abuse of these laws for civil society control. The 2018 FATF report on Syria concludes:

At the level of international cooperation, the amended laws of the Customs Department and the Commission allows exchange of information with foreign counterparts in regards to cross-border monies according to the laws, regulations, agreements and memorandums of understanding that are in place or in accordance with the principle of reciprocity. (MENA FATF, Citation2018, p. 46)

This evaluation of the FATF in 2018 is striking because the civil war continues up to the time of this writing. Even so, the FATF notes that the Syrian FIU was operating in accordance with the ‘principle of reciprocity’. While it remains unclear which FIUs exactly exchanged intelligence with Syria in 2016, as observed above this exchange occurs mainly behind closed doors, it is possible that EU FIUs shared intelligence with the Syrian FIU in the context of monitoring ‘foreign fighters’ wanting to join IS.

Importantly, this politics revolves not only around whether to share intelligence with a counterpart FIU – a yes or no – but also around what types of intelligence to share. As observed earlier, FIU intelligence encapsulates a range of open and closed information sources, the sharing of which may be more or less sensitive. Open-source information, for example, from the media, are considered less sensitive to share than, for example, credit card information, addresses and police records.Footnote10 Consider the following reply of a HoFIU to a question about sharing information with ‘questionable’ countries:

Of course … when we are speaking about countries that are questionable, both internationally and by the Egmont, then of course we do not exchange data in the same way … If I give information to [an EU country] I give everything, bank account number, bank, whatever information they want. But if I give information to [a questionable country] I will only say that it is a bank transaction and give an indication of the total amount transferred. (HoFIU, 13 August 2019)

The politics of sharing intelligence in the circuit of trust, thus, involves continuous, delicate decision-making processes, which vest considerable responsibility and authority in the hands of an FIU regarding whether, and what types of intelligence, to share with a particular, perhaps ‘sketchy’, counterpart. The sharing of financial intelligence takes place in a multifaceted political playing field in which individual FIUs autonomously and independently engage in relationships of reciprocity, deliberating on the basis of self-interest and assessments of (un)trustworthiness, and guided by their own assessments of a counterpart’s measures of confidentiality and vulnerability to political influence. This vesting of political power and decision-making authority in the hands of these relatively new security actors’ points to the importance of analyzing how they cooperate transnationally in the absence of public oversight.

Conclusion

This paper analysed how circuits of trust make sensitive financial data and transactions internationally shareable. Given the substantial geographical reach of financial intelligence and the expansive nature of monitoring transaction behaviour, a better understanding of how citizens’ financial data are shared with foreign institutions is important. This paper has stared from the premise that data do not easily ‘flow’ across jurisdictions; rather, it takes hard work and practices of building and maintaining trust to render data transnationally mobile. The analysis demonstrates that transnational financial surveillance relies on more than just the infrastructural availability of technologies that enable communication and intelligence sharing (Amicelle & Chaudieu, Citation2018). These technical platforms and systems also operate through practices and circuits of trust which lie at the core of an FIU’s decision to share intelligence.

FIUs were found to work with their own understandings of counterparts’ ‘trustworthiness’ or ‘untrustworthiness’. Transnational financial intelligence sharing was demonstrated as taking place in a legal grey zone, and in a context with a high degree of uncertainty and lack of knowledge concerning modi operandi of criminals, as well as obscurity regarding the precise application of legal and data protection frameworks (Mouzakiti, Citation2020). The qualitative fieldwork demonstrated that personal relations, mutual trust and informal acquaintance play key roles in processes of financial intelligence sharing. Circuits of trust are crucial, as these allow practitioners to meet, look each other ‘in the eye’, and nurture a basis for the sharing and circulation of financial intelligence. The nascent Egmont Group sensitivity shows that awareness of potential misuse of FIU data is increasing, yet little is known about whether and how potential human rights abuses or privacy are taken into account when FIUs decide to share financial intelligence transnationally.

Furthermore, this paper advanced the literature on economic trust practices by introducing the notion of ‘circuits of trust’, and drawing out the ways in which trust mediates data sharing. Trust was presented as a ‘socio-technical’ arrangement (de Wilde, Citation2020, p. 564), that is unstable and needs to be constructed and maintained in the materiality of practice, through workshops, conferences and other gatherings at which practitioners meet and engage. This paper contributes to Zelizer’s (Citation2004) notion of ‘circuits of commerce’ by its analysis of the trust practices that permeate seemingly impersonal institutions at the intersection between finance and security. Our analysis of ‘circuits of trust’ shows how intelligence sharing between FIUs is made possible but also reveals the fragility of this process, as it is beset with blockages, delays and legal challenges, that might lead to its breakdown.

Paradoxically, FIUs are often assumed to be, and portrayed as, apolitical organizations because they are assumed to act independently of the domestic political circumstances in which they operate. According to the Egmont Group (Citation2019, p. 31), ‘the FIU should be operationally independent and autonomous, meaning that the FIU should have the authority and capacity to carry out its functions freely’. However, this autonomy does not exclude politics from financial intelligence sharing but instead vests considerable decision-making authority and political power in the hands of individual FIUs, because they must decide independently which financial intelligence to share with counterparts on the basis of their trustworthiness. This also entails that in some cases, FIUs might elect not to share certain information with particular counterparts, due to a perception of their untrustworthiness.

In conclusion, the politics of (dis)trust and data sharing raise questions regarding accountability that need to be subjected to future research. At the time of this writing, it is difficult if not impossible to hold an FIU accountable for its practices. For instance, it remains unknown what happens to shared intelligence after it has been shared, how securely it is stored and how long a foreign counterpart may own the information. What happens to intelligence that ultimately appears to be insignificant? Perhaps most important, who is accountable when certain FIUs misuse their powers employing shared intelligence? Will an FIU inform national subjects that its sensitive data have been used for these purposes? What independent governmental organizations should monitor the decisions made by FIUs and safeguard against mistakes and illicit practices? The result of the FIU’s independence is that the politics of making intelligence shareable remains unchecked and the operations of FIUs are ultimately not subjected to democratic control.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the entire FOLLOW team for their feedback on this paper during one of our ‘corona sessions’. In particular, we would like to thank Rocco Bellanova for his additional thorough reading and feedback. The paper greatly benefited from the comments of the four anonymous reviewers and the editor of Economy and Society, whom we would like to thank for their close reading and constructive feedback. Finally, we would like to thank our interviewees, for their time and willingness to explain to us the challenges and dilemmas of sharing intelligence.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Pieter Lagerwaard

Pieter Lagerwaard is a lecturer at the University of Amsterdam (UvA), at the PPLE (Politics, Psychology, Law and Economics). Using participatory methods, he studies the use of financial transaction data for security purposes by Financial Intelligence Units (FIUs). His work has been published in the Journal of Cultural Economy, Critical Studies on Security and the Journal of Money Laundering Control.

Marieke de Goede

Marieke de Goede is Professor of the Politics of Security Cultures at the University of Amsterdam and Dean of the Faculty of Humanities. She has published widely on counterterrorism and security practices in Europe, with a specific attention to the role of financial data. De Goede is the author of Speculative security: The politics of pursuing terrorist monies and co-editor of Secrecy and methods in security research. De Goede is an Honorary Professor at Durham University (United Kingdom).

Notes

1 For all Egmont Group members, see https://egmontgroup.org/members-by-region/ (retrieved 1 December 2022).

2 By ‘data’ we understand personal information, including names, addresses, bank account numbers, credit card numbers, IP addresses, social security numbers and so forth. By ‘intelligence’ we refer to configured information, such as investigative files, dossiers, SARs and threat analysis. This separation is not clear-cut but it helps to distinguish between the information that translates and is inscribed by the FIU and the arguably more ‘raw’ information they intermediate.

3 The full SAR can be assessed at https://www.templateroller.com/template/525333/fincen-form-109-suspicious-activity-report-by-money-services-business.html#docpage-3 (retrieved 16 December 2022).

4 Events attended included the Thirty-Sixth International Symposium on Economic Crime, ‘Unexplained Wealth – Whose Business?’, 2–9 September 2018; the Chatham House, ‘Illicit Financial Flows’, 19 November 2018; and the ACAMS, ‘Fourteenth Annual Anti-Money Laundering and Financial Crime Conference to Address Global Financial Crime Threats’, 31 May to 1 June 2018.

5 The data were coded and analyzed using Atlas.ti and securely stored with VeraCrypt. See also Chapter 2.

6 See https://www.crimesymposium.org/ (retrieved 16 July 2021).

7 This respondent used the Netherlands as a fictional example because the interviewer was from that country.

8 See, for the statement, https://www.gradjanske.org/en/civil-society-and-media-will-not-give-up-the-fight-for-a-democratic-and-free-serbia/ (retrieved 17 July 2021).

9 See https://egmontgroup.org/members-by-region/ (retrieved 4 August 2022).

10 The Egmont Group expects that ‘[c]ounterparts should be able to provide financial, administrative and law enforcement information and make use of the powers available for domestic analysis in order to obtain the requested information’ (Egmont Group, Citation2017, p. 8).

References

- Amicelle, A. (2011). Towards a ‘new’ political anatomy of financial surveillance. Security Dialogue, 42(2), 161–178.

- Amicelle, A. (2017). When finance met security: Back to the war on drugs and the problem of dirty money. Finance and Society, 3(2), 106–123.

- Amicelle, A. (2018). Policing through misunderstanding: Insights from the configuration of financial policing. Crime, Law and Social Change, 69(2), 207–222.

- Amicelle, A. & Faravel-Garrigues, G. (2012). Financial surveillance: Who cares? Journal of Cultural Economy, 5(1), 105–214.

- Amicelle, A. & Jacobsen, E. (2016). The cross-colonization of finance and security through lists: Banking policing in the UK and India. Environment & Planning D: Society and Space, 34(1), 89–106.

- Amicelle, A. & Chaudieu, K. (2018). In search of transnational financial intelligence: Questioning cooperation between Financial Intelligence Units. In C. King, C. Walker & J. Gurule (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of criminal and terrorism financing law (pp. 649–675). Springer International Publishing.

- Amoore, L. (2013). The politics of possibility. Duke University Press.

- Amoore, L. & de Goede, M. (2008). Transactions after 9/11: The banal face of the preemptive strike. Transactions of the Institute of British Geographers, 33(2), 173–185.

- Anwar, T. (2020). Unfolding the past, proving the present: Social media evidence in terrorism finance court cases. International Political Sociology, 14(4), 382–398.

- Aradau, C. (2017). Assembling (non)knowledge: Security, law and surveillance in a digital world. International Political Sociology, 11(4), 327–342.

- Baird, T. (2017). Knowledge of practice: A multi-sited event ethnography of border security fairs in Europe and North America. Security Dialogue, 48(3), 187–205.

- Balázs, B. (2020). Mediated trust: A theoretical framework to address the trustworthiness of technological trust mediators. New Media & Society, 23(9), 2668–2690.

- Bellanova, R. (2017). Digital, politics, and algorithms: Governing digital data through the lens of data protection. European Journal of Social Theory, 20(3), 329–347.

- Bellanova, R. & de Goede, M. (2022). The algorithmic regulation of security: An infrastructural perspective. Regulation & Governance, 16(1), 102–118.

- Bonelli, L. & Ragazzi, F. (2014). Low-tech security: Files, notes, and memos as technologies of anticipation. Security Dialogue, 45(5), 476–493.

- Bosma, E. (2019). Multi-sited ethnography of digital security technologies. In M. de Goede, E. Bosma & P. Pallister-Wilkins (Eds.), Secrecy and methods in security research: A guide to qualitative fieldwork (pp. 193–212). Routledge.

- Boy, N. & Gabor, D. (2019). Collateral times. Economy and Society, 48(3), 295–314.

- Boy, N., Morris, J. & Santos, M. (Eds.) (2017). Special issue: Finance and security. Finance & Society, 3(2), 102–105.

- Bures, O. & Carrapico, H. (2018). Security privatization: How non-security-related private businesses shape security governance. Springer International Publishing.

- Cook, K. S., Hardin, R. & Levi, M. (2005). Cooperation without trust. Russell Sage Foundation.

- de Goede, M. (2010). Financial security. In J. P. Burgess (Ed.), The Routledge handbook of new security studies (Chapter 11) (pp. 100–109). Routledge.

- de Goede, M. (2012). Speculative security: The politics of pursuing terrorist monies. University of Minnesota Press.

- de Goede, M. (2018). The chain of security. Review of International Studies, 44(1), 24–42.

- de Wilde, M. (2020). A care-infused market tale: On (not) maintaining relationships of trust in energy retrofit products. Journal of Cultural Economy, 13(5), 561–578.

- Draku, F. (2020). The HoFIUs communi- cate on a daily basis through the Egmont Secure Web and meet once a year in the Egmont Group Annual Plenary. Monitor. Retrieved from https://www.monitor.co.ug/uganda/special-reports/elections/govt-freezes-accounts-of-4-ngos-doing-poll-work-3216360

- Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units. (2013). Principles for information exchange between FIUs. The Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units.

- Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units. (2017). Operational guidance for FIU activities and the exchange of information. The Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units.

- Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units. (2018). Annual report 2017/2018. The Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units.

- Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units. (2019). Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units charter. The Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units.

- Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units. (2021a). Annual report 2019/2020. The Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units.

- Egmont Group. (2021b). Egmont Group chair’s statement on allegations of FIUs misusing their powers to combat ML and TF. Retrieved from https://egmontgroup.org/en/content/egmont-group-chair%E2%80%99s-statement.

- Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units. (2022a). Organisation and structure. Egmont Group. Retrieved from https://egmontgroup.org/about/organization-and-structure/.

- Egmont Group of Financial Intelligence Units. (2022b). About the Egmont Group. Egmont Group. Retrieved from https://egmontgroup.org/about/.

- Fahey, E. & Curtin, D. (2014). A transatlantic community of law: Legal perspectives on the relationship between the EU and US legal orders. Cambridge University Press.

- FATF. (2020a). International standards on combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism & proliferation. FATF.

- FATF. (2020b). Letter to the UN Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights. Retrieved from https://fatfplatform.org/assets/2020-12-18-FATF-re-UN-APML-Serb.pdf.

- FATF. (2022). International standards on combating money laundering and the financing of terrorism & proliferation. FATF.

- Ferrari, V. (2020). Crosshatching privacy: Financial intermediaries’ data practices between law enforcement and data economy. European Data Protection Law Review, 6(4), 522–535.

- Gilbert, E. (2015). Money as a ‘weapons system’ and the entrepreneurial way of war. Critical Military Studies, 1(3), 202–219.

- Gitelman, L. & Jackson, V. (2013). Introduction. In L. Gitelman (Ed.), Raw data’ is an oxymoron (pp. 1–14). MIT Press.

- Helgesson, K. S. & Mörth, U. (2019). Instruments of securitization and resisting subjects: For-profit professionals in the finance–security nexus. Security Dialogue, 50(3), 257–274.

- Heng, Y. & McDonagh, K. (2008). The other war on terror revealed: Global governmentality and the Financial Action Task Force’s campaign against terrorist financing. Review of International Studies, 34(3), 553–573.

- Ho, K. (2009). Liquidated: An ethnography of Wall Street. Duke University Press.

- Hoffman, A. M. (2002). A conceptualization of trust in international relations. European Journal of International Relations, 8(3), 375–401.

- Hoijtink, M. (2019). Gender, ethics and critique in researching security and secrecy. In M. de Goede, E. Bosma & P. Pallister-Wilkins (Eds.), Secrecy and methods in security research: A guide to qualitative fieldwork (pp. 143–157). Routledge.

- Iafolla, V. (2018). The production of suspicion in retail banking: An examination of unusual transaction reporting. In C. King, C. Walker & J. Gurule (Eds.), The Palgrave handbook of criminal and terrorism financing law (pp. 81–107). Springer International Publishing.

- Issa, H. (2021). NGOs plead with government over frozen bank accounts. URN. Retrieved from https://ugandaradionetwork.net/story/ngos-plead-with-government-over-frozen-bank-accounts.

- Kazibwe, K. (2021). Govt unfreezes accounts of NGOs accused of terrorism funding. NilePost. Retrieved from https://nilepost.co.ug/2021/02/27/govt-unfreezes-accounts-of-ngos-accused-of-terrorism-funding/.

- Koole, B. (2020). Trusting to learn and learning to trust: A framework for analyzing the interactions of trust and learning in arrangements dedicated to instigating social change. Technological Forecasting & Social Change, 161, 120260.

- Lababidi, E. M. R. (2020). State and institutional capacity in combating money laundering and terrorism financing in armed conflict the Central Bank of Syria. Journal of Money Laundering, 23(1), 155–172.

- Lagerwaard, P. (2020). Flattening the international: Producing financial intelligence through a platform. Critical Studies on Security, 8(2), 160–174.

- Lagerwaard, P. (2022). Financiële surveillance en de rol van de Financial Intelligence Unit (FIU) in Nederland. Beleid en Maatschappij, 2(49), 128–153.

- Langenohl, A. (2017). Securities markets and political securitization: The case of the sovereign debt crisis in the eurozone. Security Dialogue, 48(2), 131–148.

- Langley, P. (2017). Finance/Security/Life. Finance and Society, 3(2), 173–179.

- Leyshon, A. & Thrift, N. (1997). Money/space: Geographies of monetary transformation. Routledge.

- Liss, C. & Sharman, J. (2015). Global corporate crime-fighters: Private transnational responses to piracy and money laundering. Review of International Political Economy: RIPE, 22(4), 693–718.

- MacKenzie, D. (2001). Mechanizing proof: Computing, risk, and trust. MIT Press.

- MENA FATF. (2018). Mutual evaluation report: 13th follow-up report for Syria. MENA FATF. Retrieved from http://www.menafatf.org/mutual-evaluations-follow/follow-up-reports.

- Mitsilegas, V. (2014). Transatlantic counterterrorism cooperation and European values: The elusive quest for coherence. In E. Fahey & D. Curtin (Eds.), A transatlantic community of law: Legal perspectives on the relationship between the EU and US legal orders (pp. 289–315). Cambridge University Press.

- Mouzakiti, F. (2020). Cooperation between Financial Intelligence Units in the European Union: Stuck in the middle between the General Data Protection Regulation and the Police Data Protection Directive. New Journal of European Criminal Law, 11(3), 351–374.

- Nance, M. T. (2018). The regime that FATF built: An introduction to the Financial Action Task Force. Crime, Law, and Social Change, 69(2), 109–129.

- Olsen, R. A. (2008). Trust as risk and the foundation of investment value. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 37(6), 2189–2200.

- Overton, J. (1999). Worlds apart: Reflections on trust, colonialism and decolonization. Hume Papers on Public Policy, 7, 33–41.

- Permanent Mission of the Republic of Serbia to the United Nations. (2020). Responses of the Republic of Serbia. Retrieved from https://spcommreports.ohchr.org/TMResultsBase/DownLoadFile?gId=35826.

- Pryke, M. (2010). Money’s eyes: The visual preparation of financial markets. Economy and Society, 39(4), 427–459.

- Rasha, M. (2019). Syria participates in Egmont Group for combating money laundering and terrorism funding in Hague. SANA. Retrieved from https://www.sana.sy/en/?p=169229.

- Searle, R. H., Nienaber, A.-M. I. & Sitkin, S. B. (Eds.) (2018). The Routledge companion to trust. Routledge.

- Sharman, J. C. (2009). The bark is the bite: International organizations and blacklisting. Review of International Political Economy: RIPE, 16(4), 573–596.

- Sitkin, S. B. & Bijlsma-Frankema, K. M. (2018). Distrust. In R. H. Searle, A.-M. I. Nienaber & S. B. Sitkin (Eds.), The Routledge companion to trust (pp. 128–150). Routledge.

- Siu, L. L. S. (2010). Gangs in the markets: Network-based cognition in China’s futures industry. International Journal of China Studies, 1(2), 21.

- The Independent. (2021). EU, US envoys urge gov’t to unfreeze CSO bank accounts. Retrieved from https://www.independent.co.ug/eu-us-envoys-urge-govt-to-unfreeze-cso-bank-accounts/.

- Vedrenne, G. (2021). Exclusive: Egmont flags government abuse of financial intelligence. ACAMS moneylaundering.com. Retrieved from https://www.moneylaundering.com/news/exclusive-egmont-flags-government-abuse-of-financial-intelligence/.

- Versloot, L. (2022). The vitality of trusting relations in multilateral diplomacy: An account of the European Union. International Affairs, 98(2), 509–528.

- Wesseling, M. (2013). The European fight against terrorism financing: Professional fields and new governing practices. PhD dissertation. University of Amsterdam.

- Westermeier, C. (2020). Money is data: The platformization of financial transactions. Information, Communication & Society, 23(14), 2047–2063.

- Zelizer, V. A. (2006). Circuits in economic life. Economic Sociology, 8(1), 30–35.

- Zelizer, V. A. (2004). Circuits of commerce. In J. C. Alexander, G. T. Marx & C. L. Williams (Eds.), Self, social structure, and beliefs (pp. 122–144). University of California Press.