Abstract

In the Reclus-Perron cartographical collection held in the Public Library of Geneva, a recently discovered map by the explorer Henri Coudreau seems to have been essential, together with other published and unpublished cartographic materials, in deciding the 1900 Swiss arbitration of the Franco-Brazilian border dispute. These materials provide an opportunity not only to analyse the political power of maps, but also to explore a different European way of conceiving maps and geography, that of anarchist geographers, which diverged from the uncritical hagiographies of colonialism and geographical discoveries that were typical in European science during the Age of Empire (1875‒1914).

Une nouvelle carte du conflit frontalier franco-brésilien (1900)

Dans la collection cartographique Reclus-Perron conservée à la Bibliothèque publique de Genève, une carte de l’explorateur Henri Coudreau récemment découverte semble avoir joué un rôle essentiel, en même temps que d’autres matériaux cartographiques (publiés ou non), dans l’arbitrage rendu en 1900 par la Suisse dans le conflit frontalier franco-brésilien. Ces matériaux offrent l’opportunité non seulement d’analyser le pouvoir politique des cartes, mais aussi d’explorer une façon différente de concevoir les cartes et la géographie en Europe, celle des géographes anarchistes qui se démarquèrent de l’hagiographie peu critique du colonialisme et des découvertes géographiques, qui était typique de la science européenne à l’âge des Empires (1875‒1914).

Eine neue Karte des Grenzstreits zwischen Frankreich und Brasilien (1900)

In der Reclus-Perron Kartensammlung in der Bibliothek von Genf befindet sich eine Karte des Forschungsreisenden Henri Coudreau, die zusammen mit anderen publizierten und unveröffentlichten Karten, eine wesentliche Rolle bei der Entscheidung der schweizerischen Schlichtungsinitiative im französisch-brasilianischen Grenzstreit gespielt haben dürfte. Diese Materialien bieten nicht nur die Möglichkeit, die politische Relevanz von Karten zu untersuchen, sondern zeigen auch einen unkonventionellen europäischen Weg der Kartographie und Geographie: den anarchistischer Geographen, die sich von den unkritischen Hagiographien des Kolonialismus und der geographischen Entdeckungen absetzten, wie sie für das Europa des imperialistischen Zeitalters (1875‒1914) typisch waren.

Un Nuevo mapa de la disputa fronteriza franco-brasileña de 1900

Un mapa recientemente descubierto del explorador Henri Coudreau en la colección cartográfica Reclus-Perron, alojada en la Biblioteca Pública de Ginebra, parece haber sido esencial, junto con otros materiales cartográficos publicados e inéditos, para decidir el arbitraje suizo de la disputa fronteriza franco-brasileña. Estos materiales proporcionan una oportunidad, no solo de analizar el poder político de los mapas, sino también de explorar un diferente modo europeo de concebir los mapas y la geografía: el de los geógrafos anarquistas, que divergió de la acrítica hagiografía del colonialismo y de los descubrimientos geográficos que eran típicos de la ciencia europea durante la Edad del Imperio (1875‒1914).

A rich literature draws on maps, including historical ones, as powerful tools in decision making and problem solving. This paper deals with a specific case of the utilization of a map to resolve a diplomatic issue, namely the 1897‒1900 Franco-Brazilian border dispute on the southern frontier of French Guiana, finally settled in 1900 through arbitration by the Swiss government (, and ). For this task, the Swiss referees made use of a number of maps to try to identify the course of the Japoc River. This was the first river to have been given a name by the Spanish sailor Vicente Pinzón (Pinçon in Portuguese) in 1500. The Japoc was recognized by the 1713 Utrecht agreement as the legal border between French and Portuguese territories, but by 1890 it was no longer known which river course actually corresponded to this definition.

Fig. 1. Location of area shown in Henri Coudreau’s map of the contested Franco–Brazil frontier. (Drawn by D. Bove.)

Fig. 2. Carte générale de la Guyane représentant les prétentions des deux parties et dressée principalement d’après les cartes annexées aux documents français et brésiliens (1900). 41 × 32 cm. Scale 1:4,000,000. The map shows the rival claims. Brazil wanted the border to run along the river Oyapoc [Oyapock] and thence across French Guinea [Guyane française] to the Tumuc Humac mountains, which border Dutch Guiana (see detail in ). France claimed all the land between that line, extended west to the Rio Branco, and a second line running from the Branco to the Rio Araguay and the Atlantic Ocean. The map was published as Plate 1 in the official proceedings of the Swiss arbitration, Sentence du Conseil fédéral suisse dans la question des frontières de la Guyane française et du Brésil du 1er décembre 1900 (Bern, Imprimerie Staempfli, 1900), Annexes. Bibliothèque de Genève, Département de Cartes et Plans, tiroir Amérique latine—cartes partielles. (Reproduced with permission from the Bibliothèque de Genève, Switzerland.)

![Fig. 2. Carte générale de la Guyane représentant les prétentions des deux parties et dressée principalement d’après les cartes annexées aux documents français et brésiliens (1900). 41 × 32 cm. Scale 1:4,000,000. The map shows the rival claims. Brazil wanted the border to run along the river Oyapoc [Oyapock] and thence across French Guinea [Guyane française] to the Tumuc Humac mountains, which border Dutch Guiana (see detail in Figure 3). France claimed all the land between that line, extended west to the Rio Branco, and a second line running from the Branco to the Rio Araguay and the Atlantic Ocean. The map was published as Plate 1 in the official proceedings of the Swiss arbitration, Sentence du Conseil fédéral suisse dans la question des frontières de la Guyane française et du Brésil du 1er décembre 1900 (Bern, Imprimerie Staempfli, 1900), Annexes. Bibliothèque de Genève, Département de Cartes et Plans, tiroir Amérique latine—cartes partielles. (Reproduced with permission from the Bibliothèque de Genève, Switzerland.)](/cms/asset/48261430-b260-4d0d-84f1-00eedaa20178/rimu_a_1027554_f0002_b.gif)

Fig. 3. Detail from the Carte générale de la Guyane (see ). The single-headed arrow points to Brazil’s claim, eventually favoured, for a boundary along the Oyapock River and thence along the watershed of the Amazon basin to the border with Dutch Guiana. The double-headed arrow indicates part of the area wanted by France. From Sentence du Conseil fédéral suisse dans la question des frontières de la Guyane française et du Brésil du 1er décembre 1900 (Bern, Imprimerie Staempfli, 1900), Annexes, Plate 1. Bibliothèque de Genève, Département de Cartes et Plans, tiroir Amérique latine—cartes partielles. (Reproduced with permission from the Bibliothèque de Genève, Switzerland.)

The focus in this article is on a manuscript map, drawn by the explorer Henri Coudreau (1859‒1899) and given by him to the geographer Élisée Reclus (1830‒1905) in 1893, that has been recently discovered in the Public Library in Geneva among Reclus’s maps.Footnote1 This particular map was early recognized to have played a role in directing the decisions reached by the Swiss scholars who had been asked by their government to study the problem. It is not surprising that Coudreau’s map has lain among Reclus’s paper all this time unnoticed. The archive contains, among various source materials, preparatory drawings, proof copies and notes, some 10,000 maps amassed by Reclus and Charles Perron (1837‒1909), geographer and cartographer respectively, during their work for the encyclopaedic Nouvelle Géographie universelle.Footnote2

In the course of consulting the minutes of the Geneva City Council, my attention was caught by an entry for 8 January 1904 recording the city councillors’ decision to finance a cartographical exhibition based on the material that Reclus had left in Switzerland in 1891. The councillors remarked on the political importance of some of the maps and referred to one map in particular, noting that ‘It is one of these unpublished pieces (a manuscript map by the explorer Coudreau) that allowed Professor [William] Rosier to resolve many uncertain points in the course of the Federal Council’s arbitration of the line of the Franco-Brazilian frontier’.Footnote3

That statement led me to examine the documents from the deliberations of the Swiss Federal Council that were published in Bern in 1900. There I noticed that nowhere, in a volume of 850 pages and eight attached folded maps containing the Council’s discussions and documents relating to the Brazil–French Guiana border, were the names of any of the scientific advisors consulted by the Swiss referees given.Footnote4 Reclus was quoted twelve times and Coudreau eighteen as the most recent and authoritative geographical sources for the region. It is clear that the diplomats’ arbitration had depended on the contributions of specialist historians and geographers, an aspect confirmed by contemporary newspapers, one of which stated that ‘the preliminaries of this deliberation gave rise to long and difficult studies in the fields of history and geography, which the Federal Council entrusted to a number of Swiss scholars’.Footnote5

One of these Swiss scholars was William Rosier (1856‒1924), a geographer from Geneva, a liberal politician, an admirer of Reclus and a friend of Perron. Manuscript notes in volume 6 (the Atlas containing the historical maps made available to the Swiss referees) of the Geneva Public Library’s copy of the Brazilian multi-volume memoir (written in French and printed in Paris) were supplied by Rosier.Footnote6 Between 1895 and 1901 Rosier had been a member of the Geneva State Parliament, a government minister, a member of a federal commission for public education in Bern, and by the start of the twentieth century, he was considered one of the most authoritative geographers in Switzerland.Footnote7 In short, there is nothing surprising either in the Federal Council’s asking Rosier’s advice in the affair or in the Council’s advisors relying on the cartographic collection of Geneva, the richest in Switzerland, for information.

Henri Coudreau’s Map of Brazil

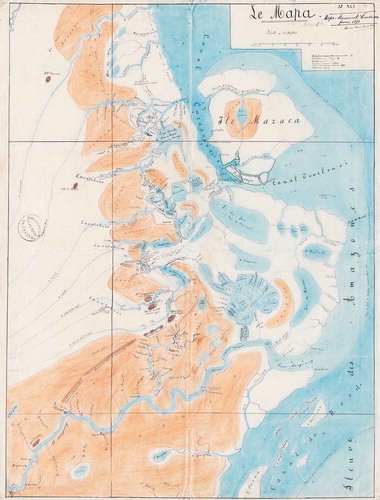

Coudreau had compiled his manuscript map in 1893 and sent it to Reclus for the South American volume of the Nouvelle Géographie universelle, in which Perron had used it for two of the black-and-white maps published in volume nineteen.Footnote8 Coudreau’s map, entitled simply Le Mapa, shows in some detail the geography of the Atlantic coast of South America from the northern channel of the Amazon River north to the Carsevenne River, an area corresponding to the southern part of the territory claimed by France ( and ).

Fig. 4. Henri Coudreau’s manuscript map of Guiana, of 1893 (see Plate 9). Manuscript. 85 × 60 cm. Scale 1:312,500. The key lists the signs for settlements, paths and vegetation, but most of the written notes on the map concern aspects of the region’s hydrography. At issue in the dispute over the Franco-Brazilian frontier was the Carapaporis channel between Maraca Island and the mainland, which the French alleged had been created only recently and thus marked the frontier as this had been established in the Utrecht agreement of 1713, before the island was cut off. Bibliothèque de Genève, Département de Cartes et Plans, tiroir Amérique latine—cartes partielles. (Reproduced with permission from the Bibliothèque de Genève, Switzerland.)

Plate 9. Le Mapa, Henri Coudreau’s unpublished map of Guiana given to Élisée Reclus in 1893 for the Nouvelle Géographie universelle (vol. 19, Hachette, 1894). 85 × 60 cm. Scale 1: 312,500. North is at the top. The map contains a wealth of detail about the physical geography of the part of the coast of Brazil from the Amazon’s northern channel to the Carsevenne River that was being claimed by France. Bibliothèque de Genève, Département de Cartes et Plans, tiroir Amérique latine—cartes partielles. (Reproduced with permission from the Bibliothèque de Genève.) See p. 232.

The map measures 85 by 60 centimetres. It is in ink on a rather thin paper and tinted in bright watercolours. The scale is given as 1:312,500. There is also a scale bar in kilometres. Rivers, the numerous coastal lakes and lagoons, and the sea are blue, darker where the water is deeper and navigable for European ships; a fine pecked line labelled Ligne de fond de 4 mètres aux plus basses mers [Depth line of 4 metres at low tide] demarcates the shallowest water. Coastal lowland is uncoloured. The unvisited, or unsurveyed, interior, across which several rivers (all named) are indicated schematically with pecked lines, is uncoloured. The occasional upland is marked with hachures and coloured dark brown. Lighter brown land, labelled in many places Savane (Savannah), is widespread between the coastal region and the interior.

A key in the upper-right corner contains the date and author’s signature and identifies five features: Habitation; Village (house; village), represented respectively by a point and a circle; Sentier (path), represented by a pecked line; Prairies, Savane (meadows, savannah), tinted in brown watercolour; Régions marécageuses ou inondées (marshes or inundated regions), shaded with roughly-drawn horizontal lines overwashed in blue; and Ancien lac (former lake), represented by an uncoloured area outlined by short hachures. Considerable attention has been paid to potential anchorages and navigable water; ports are indicated by an anchor sign, and detailed information is provided for the passage of different kinds of ships by numbers giving bathymetrical measurements. The depth of the Carapaporis channel, between Maraca Island and the continental coast, is obvious—a feature that in due course attracted the attention of the scholars researching the border dispute. It pointed to the unlikeliness of the hypothesis that this island was, until recent times, part of the continent.

Coudreau’s emphasis on accessibility is also reflected in the name of the creek that crosses Maraca Island, Crique Calebasse or, in Portuguese Igarapé do Inferno [Hell Creek], specified as accessible seulement aux petits bateaux [accessible to small boats only]. Unstable or seasonal rivers and lagoons are represented by pecked lines, and information is provided on the geomorphological evolution of these features, with references to silted channels, ancient lagoons and their former French, Portuguese or indigenous toponyms. A former tributary of the Araguary, near that river’s estuary, is labelled R. Amacary—Barrancas, ou bouche du R. Moro (ancien Rio Tapado), obstrué [River Amacary—Barrancas River, or estuary of the Moro River (ancient Tapado River), obstructed]. Every stream, inlet, lake and lagoon is named this way, with detailed notes giving modern and past toponymy. On a number of rivers, lines across the channel indicate a channel blocked in some way. On the Tartarugal River a waterfall is labelled Chute [fall]. Sporadically, an arrow gives the direction of water flow.

Settlements are marked with abstract signs in black ink. Circles with a dot indicate the two major villages—Mapa and Colonia Militar dom Pedro II—which were the centres of Brazilian settlement in the contested area. Habitations or smaller settlements such as farms or isolated houses are represented by small points and are labelled with the Brazilian toponym or with the owner’s name. Sometimes we find information like ‘house belonging to a Paraguayan’.Footnote9 Crosses and stippling represent cemeteries and missions. All the settlements are Brazilian, sometimes with toponyms of indigenous origin. A few paths between them are represented, but the chief form of communication, according to the map, seems to have been the waterways. In the interior, labels such as Caoutchouc (rubber) indicate the potential economic value of this region.

What the map communicates at a glance is indeed the complexity of the morphology and hydrography of a highly unstable physical environment. The only rivers that appear to be well-known and well-defined are in the southern part of the territory, where the Amazon’s northernmost channel (Canal du Nord) is highlighted as deep water where it enters the sea, as is the Araguary River north of it.

Approaching the Problem

The main task that the 1897 Franco-Brazilian conference entrusted to the Swiss government was to locate the Japoc River. A decisive role was played by maps and literature relating to the early exploration of the region. As D. Graham Burnett found in the case of Venezuela’s dispute with British Guiana in the 1840s over its northern border, and here too in Brazil’s dispute with France, ‘Colonial territory came into being as a result of the passage of certain individuals—explorers and surveyors—who made distant land possessable by means of a set of powerful linked texts. Diplomats explored those texts, not jungles, to see who had a right to what’.Footnote10

The Swiss geographers appointed to inform the Swiss referees approached their task from three directions, systematically analysing all the sources they could find for the region’s history, physical geography, and human and political geography. They reconstructed its history through historical maps and travel narratives. They investigated the morphological and hydrographical coastal dynamics. And they analysed all available data about the local inhabitants and, in particular, the results of French and Brazilian attempts to establish coastal and inland villages.

Their armchair geography was encyclopaedic, as befitted the political situation of Switzerland at the time: a European state with neither sea nor colonies that nonetheless saw a role for itself in international relations.Footnote11 As I have argued elsewhere, the very concepts of Reclus’s Nouvelle Géographie universelle and the authority of local geography can also be seen as the products of ‘International Switzerland’, a place of exiles and refugees in which Reclus and his collaborators created their great encyclopaedia during their exile in the Helvetic Confederation.Footnote12

Inevitably, the armchair geographers could not avoid the epistemological discourse surrounding them. Their eventual judgment, which contradicted official French accounts that claimed the Japoc River corresponded to the Araguary, reflected their decision that Reclus and his mapmaker Coudreau were the most authoritative and their evidence the most weighty.Footnote13 The adjudicators appear, by starting with Reclus’s criticism of cartographic documents as if ‘objective’ sources, to have agreed with the theoretical foundation of his geography, further developing the point by quoting Alexander von Humboldt’s argument that

geographical maps reflect the opinions and knowledge, more or less limited, of those who construct them; but they do not recount the status of their findings. That which we find drawn on maps (and this is especially the case with those of the XIVth, XVth and XVIth centuries) is a mixture of confirmed facts and conjectures presented as facts.Footnote14

Reclus himself had steered clear of the debate because he was not interested in questions of a ‘diplomatic character’, commenting that with questions such as ‘Which is this river Yapok or Vicente Pinzon that the Utrecht diplomats, unfamiliar with American things, wanted to mark on their rudimentary maps? … One could fill libraries with the reports and diplomatic documents published on this insoluble question’.Footnote15

Locating the Border

In his own work, Reclus’s aim was to build a geography independent of political power. In working for the arbitration over the Franco-Brazilian border, however, the political question had to be addressed. The Swiss geographers, relying on Coudreau’s first-hand observations, found they could interpret the complex dynamics of the coastline to give the Swiss referees reasons for questioning the older cartographic documents, which were more ideological and less grounded in direct observation. According to the referees, the physical geography portrayed on maps like Coudreau’s demonstrated that it was not possible for the Japoc, as described by Vicente Pinzón, to have been one of the Amazon’s channels. In particular, they refuted a central point in the official French record, the claim that the contemporary Carapaporis channel represented an ancient north-flowing course of the Araguary, whereby the island of Maraca would have still been connected to the continent as recently as the sixteenth century (). This could be the only reason Pinzón omitted to mention this island.

Fig. 5. Detail from Coudreau’s map as redrawn by Charles Perron for the Nouvelle Géographie universelle, volume 19, 1894, 87, showing the deep-water Carapaporis channel and Maraca Island. The stippling represents marshy zones. (Reproduced with permission from the Bibliothèque de Genève, Switzerland.)

After analysing the morphological history of the coast and citing Reclus, Coudreau and the other geographers, the Swiss referees concluded by arguing that the Maraca Island and the Carapaporis channel were geologically much older. According to them, this proved that the cartographers quoted by the Utrecht diplomats had not been as familiar with the region as they pretended, saying dismissively that, ‘Consequently, it is unnecessary, in any case, to look for the Vincent Pinçon of the old cartographers either in the Channel or in the Carapaporis River’.Footnote16 According to the referees, the northern arm of the Araguary ‘does not exist, and has never existed’.Footnote17

A look at Coudreau’s manuscript map, which Rosier would have consulted, allows us to suppose that it was above all the map’s bathymetric record that directed Rosier and his colleagues to their conclusion. As already noted, Coudreau had paid particular attention to the depth of water in the coastal districts and immediately offshore, noting his observations meticulously. His map shows no geomorphological evidence, such as abandoned channels and fluvial ridges, to support the French argument that the Carapaporis channel marks a former course of the Araguary River and that the separation of Maraca Island from the mainland was recent. Rosier, studying Coudreau’s map, accordingly argued that it was unlikely that such a radical transformation could have been accomplished in no more than two or three centuries. Whatever river Pinzón had seen, it could not have been the Araguary.

In addition to examining the physical features in the disputed area, the Swiss referees also considered the history of the territory and its inhabitants. Apart from some French enclaves along the coast, this part of South America was almost completely occupied by Brazilians and indigenous peoples. Again, Reclus and Coudreau were cited as the principal sources and in contradiction of the French claims. One argument was that the peoples of the hinterland—for example, in the Rio Branco Valley—recognized Brazil as their nation. Lest the geographers’ impartiality was open to question, the fact that both were French nationals was cleverly inserted into the Swiss referees’ report:

Brazil’s sovereignty, especially in the Rio Branco valley, was recognized by its population. In his work La France équinoxiale, Coudreau said: ‘We can no longer today sustain our claims as far as the Rio Branco; the Rio Branco cannot not be disputed, since Brazilians exploited and populated it’. Élisée Reclus has confirmed this statement in the following passage: ‘However the debate does not have real importance except for the contest over the coast, between the Oyapock and the Araguary. To the west, all the Rio Branco valley has become uncontestably Brazilian by language, custom, and political and commercial relations’.Footnote18

Reclus’s statement had already worried the French Minister Stephen Pichon in correspondence going back to 1896.Footnote19 At the same time, the Brazilians had relied on the work of other Frenchmen, such as Jules Crevaux as well as Coudreau, to develop their own arguments.Footnote20

Colonialism, Nationalism and Anarchism

In the end, the border between French Guiana and Brazil was established along the river that is now known as the Oyapock [Portuguese Oiapoque], a decision that satisfied Brazil’s territorial claims (see ). But we have to ask, why did the Swiss referees accord such importance to Coudreau’s and Reclus’s maps and to the latter’s writings? The key may lie in the personal philosophy of the two French geographers, who were independent of the interests of their nation. Neither supported the idea of colonialism. Rather, they claimed that they stood for scientific independence. In the case of Reclus, this attitude owed much to his political identity as an anarchist and to his experience as a veteran of the 1871 Paris Commune, for which he was exiled from France for the greater part of his life. He explicitly criticized the idea of patriotism, preferring the idea of cosmopolitanism, and contested the notion of borders, protesting he was ‘against all these boundaries, symbols of monopolization and hatred! We are eager finally to be able to embrace all men and call ourselves their brothers!’Footnote21

Coudreau apparently shared Reclus’s endorsement of the independence of science. During the making of the map, he remained true to his empirical observations. Although his draft map was sent to Reclus in 1893, it was not published, which might suggest that Reclus was the only French geographer prepared to disseminate information that risked damaging his homeland. Coudreau had started his career as a ‘colonialist’ sent out to Guiana by the French government, but he abandoned his formal appointment to live as an ‘irregular’, staying with indigenous people. Coudreau was considered in France to be a ‘maverick’ explorer, and ‘a little anarchist.’Footnote22 In the last years of his life, he was branded a traitor for taking an appointment in the Brazilian government.Footnote23 Early in 1896, Coudreau wrote from Brazil to his friend Reclus complaining that he was being marginalized and comparing himself to the defeated fighters of the Paris Commune.Footnote24 Letters written by Reclus after Coudreau’s death in Brazil in 1899 reveal that he tried to help Coudreau’s widow financially.Footnote25

In fact, Reclus owed much to Coudreau. Coudreau had been one of Reclus’s most important sources for the chapters on Brazil and Guiana, as Reclus acknowledged at the end of his work, noting that: ‘My friend Henri Coudreau has kindly read the proofs of the chapter on Guiana’.Footnote26 Reclus had also quoted several times from the ‘manuscript notes’ that Coudreau had sent him.Footnote27 The importance of Coudreau’s role is still upheld; the Brazilian historian Nelson Sanjad has concluded that the pages Reclus wrote on the Contested Territory are ‘a great summary of Coudreau’s ideas ’.Footnote28

The Franco-Brazilian dispute reinforces my earlier suggestion that Reclus and the other anarchist geographers were precocious and radical adversaries of colonialism, systematically denouncing European colonial crimes committed the world over.Footnote29 The case of France and Guiana was no exception. Reclus fumed at the brutality of the République in these latitudes, and at the antisocial function of the Cayenne penal colony, writing that

Of all the overseas possessions that France has arrogated to itself, none prospers less than its part of the Guianas: one cannot relate this history without shame. The example of French Guiana is the one usually chosen to show the incompetence of the French in matters of colonization.Footnote30

He denounced the thousands of deaths brought about by clumsy attempts to acclimatize Indian workers to French plantations, protesting that this was ‘without method and without humanity’ and that out of ‘8,372 workers hired in the prime of life, 4,522 had died in the 22 years between 1856 and 1878’.Footnote31 As regards the indigenous inhabitants, he remarked that ‘more than the half of the peoples cited by the early authors have disappeared’.Footnote32 This was not the first time Reclus had expressed his anti-colonial ideas. Some years previously he had been the only well-known French scientist of his day explicitly to claim independence for Algeria, writing that Algerians must be given all their rights, ‘including that of getting rid of us’.Footnote33

The gap between Reclus and contemporary French geographers is highlighted when his statements are compared with those expressed by Paul Vidal de la Blache after the Swiss judgment on the Franco–Brazilian frontier. Vidal de la Blache asserted that ‘although the end of any long dispute is always a positive fact’, he nonetheless regretted that ‘the case is turning out to our detriment’.Footnote34 With other French geographers, Vidal de la Blache had been directly engaged in preparing documents to be supplied to the adjudicators of the border dispute, and whereas his evaluation of the final judgment was relatively moderate, geographers like Augustin Bernard severely criticized the Swiss referees and the scientific basis of their decision.Footnote35

The Swiss judgment also upset the more conservative elements of the French press, namely Le Figaro and Le Temps, whose writers fumed over the decision. They questioned the impartiality of Switzerland, which they accused of having reached its decision in the light of its own commercial interests in Brazil. The Swiss press promptly responded with statistical data showing that ‘if Switzerland has vital and essential interests with one of the parties in question, it is not with Brazil, but truly with France’.Footnote36

Reclus and Coudreau’s Legacy in Brazil

The Franco–Brazil frontier dispute left its mark in Brazil, notably as regards the reception there of Reclus’s works. Reclus was already well-known in the country from his visit in 1893 to the Geographical Society in Rio de Janeiro and to the Historical and Geographical Brazilian Institute.Footnote37 Reclus had been corresponding with the Brazilian, Baron Rio Branco, helping him to obtain maps for the 1893‒1895 border dispute between Brazil and Argentina, resolved in favour of Brazil.Footnote38 Rio Branco was also a protagonist for Brazil over the disputed frontier between France and Brazil, resolved in 1900.

Accordingly, when, in 1903, Brazil found itself with a new frontier dispute, this time with British Guiana, the idea arose within the scientific network, which included politicians and diplomats, to ask Élisée Reclus for help. The eminent Brazilian writer José Pereira de Graça Aranha, diplomat and Reclus admirer, contacted the by-then elderly Reclus, now living in Brussels, to ask him for maps that would assist Brazil in the new dispute.Footnote39 According to M. H. Castro Azevedo,

Reclus accepted the task in order to oppose the interests of the British in the passage to the Amazon River, where they intended to build a railway; he was also personally very interested in this region, as he wanted America for Americans.Footnote40

The point of the story in the context of the present article is not to suggest that European anarchists in general preferred Brazilian imperialism to that of the British or French. Rather, the message is that, in the second half of the nineteenth century, many of the anarchists expressed their solidarity with the struggle for national independence among the colonized nations as well as in Eastern Europe. They hoped that those struggles would herald the development of social revolutions, a process that Benedict Anderson has described as ‘anti-colonial imagination’.Footnote41

It was easy for Reclus’s Nouvelle Géographie universelle to be warmly embraced in South America, where relevant chapters, with the original maps by Perron, were translated into Spanish and Portuguese to become the main national geographical monographs of the respective countries.Footnote42 This was the case not only in Brazil, where Reclus’s text was published in B. F. Ramiz Galvão’s translation in 1900 with a preface by Rio Branco, but also in Colombia with Francisco Javier Vergara y Velasco translations of 1893.Footnote43 In Brazil, Reclus’s work went further, inspiring Euclides de Cunha to write his masterpiece, Os Sertões, the classic ‘national novel’.Footnote44

The settling of the Franco-Brazilian frontier and the work of Reclus, Coudreau and Perron show how the ‘power’ of maps can lead to some rather unintended results. Whereas Harley noted that ‘Maps were key documents in both a practical and an ideological sense in shaping European nationalism and imperialism’, the originality of the specific case examined here is not so much to support the notion that maps have a power of their own as to demonstrate the heterogeneity of that idea and to point to the sometimes unanticipated ideological directions that cartographic representation can take.Footnote45 According to Harley, maps are the language of power, never that of contestation: their ‘ideological arrows have tended to fly largely in one direction, from the powerful to the weaker in society’.Footnote46 Research, though, shows that maps acted not only for the European empires, but also against them. Such was the case, in 1900, of a map built by the ‘maverick’ explorer and cartographer Henri Coudreau, sponsored in the scientific world by a heterodox geographer Élisée Reclus.

A final observation is worth making. Coudreau’s map had two roles; the first editorial, as a contribution to the Nouvelle Géographie universelle, the second as a diplomatic tool in the hands of William Rosier. The interlinking of these two uses underlines the importance of taking account of the place and material condition of each map. It might be expected that an accurate topographical map made by a military-cartographical service deserves its role in imperial strategy, whereas, as Henri Coudreau’s map testifies, an individual map made by an irregular explorer may sometimes have a more complex pattern of use.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Swiss National Fund for Scientific Research (SNF) within the project Écrire le monde autrement: géographes, ethnographes et orientalistes en Suisse Romande (1864–1920), des discours heterodoxes [grant number: 140274]. My thanks are due to all the colleagues from several countries with whom I have discussed the Franco-Brazilian dispute, especially for their help in pointing me to the documentary sources: Nelson Sanjad, Jean-Yves Puyo, Carlo Romani, Patricia Aranha, Breno Viotto Pedrosa, Guilherme Ribeiro, Sergio Nunes Pereira, Manoel Fernandes and Michael Heffernan. Especial thanks go to David Ramirez Palacios and Luciene Carris Cardoso for supplying the correspondence between Reclus and Rio Branco. I also wish to thank the staff of the Geneva Public Library for opening up their archives to me, and especially to Marianne Tsioli and Alexandre Vanautgaerden.

Notes

1. Le Mapa, manuscript map by Henri Coudreau, Bibliothèque de Genève, Département de Cartes et Plans, tiroir Amérique latine—cartes partielles. In 1893 the collection was given to the City of Geneva. For a description of the Perron-Reclus collection see Federico Ferretti, ‘Cartographie et éducation populaire: Le Musée Cartographique d’Élisée Reclus et Charles Perron à Genève (1907‒1922), Terra Brasilis, Revista da Rede Brasileira de História da Geografia e Geografia Histórica 1 (2012): http://terrabrasilis.revues.org/178; Federico Ferretti, ‘Pioneers in the history of cartography: the Geneva map collection of Élisée Reclus and Charles Perron’, Journal of Historical Geography, 43 (2014): 85‒95. For a first description of the Coudreau map see Federico Ferretti, ‘O fundo Reclus-Perron e o contestado franco-brasileiro de 1900: um mapa inedito que decidiu as fronteiras do Brasil’, Terra Brasilis 2 (2013): http://terrabrasilis.revues.org/744. See also Federico Ferretti, ‘The correspondence between Élisée Reclus and Pëtr Kropotkin as a source for the history of geography’, Journal of Historical Geography 37 (2011): 216‒22.

2. Élisée Reclus, Nouvelle Géographie universelle, vol. 19: L’Amazonie et la Plata (Paris, Hachette, 1894).

3. Archives de la ville de Genève, Mémorial des séances du Conseil Municipal de la Ville De Genève, Séance du 8 janvier 1904, 622‒23. ‘C’est une de ces pièces inédites (manuscrit de l’explorateur Coudreau) qui permit à M. le professeur Rosier de résoudre de nombreux points douteux lors de l’arbitrage soumis au Conseil fédéral pour la délimitation de la frontière franco-brésilienne’. All quotations from texts in French or Portuguese have been translated by the author.

4. Sentence du Conseil fédéral suisse dans la question des frontières de la Guyane française et du Brésil du 1er décembre 1900 (Bern, Imprimerie Staempfli, 1900).

5. ‘Le contesté franco-brésilien’, Gazette de Lausanne, 4 December 1900: 2. ‘Les préliminaires de cette sentence ont donné lieu, dans les domaines de l’histoire et de la géographie, à des études longues et difficiles dont le Conseil fédéral a confié le soin à un certain nombre de savants suisses’.

6. Geneva Public Library, Frontières entre le Brésil et la Guyane française. Second mémoire présenté par les États unis du Brésil au gouvernement de la Confédération suisse, arbitre choisi selon les stipulations du traité conclu à Rio-de-Janeiro, le 10 avril 1897 entre le Brésil et la France. Tome VI: Atlas (Paris, Lahure, 1899). The Geneva Library also contains the other volumes of the Brazilian evidence, as well as a complete set of the French material. When Perron opened the Musée cartographique in Geneva in 1907, which ran until 1922, he included several of the maps. Charles Perron, Catalogue descriptif du Musée cartographique—Dépôt des cartes de la Ville de Genève (Geneva, Imprimerie Romet, 1907); Charles Perron, Une étude cartographique: les mappemondes (Paris, Éditions de la Revue des Idées, 1907).

7. Bibliothèque de Genève, Département des Manuscrits, Biographies genevoises, ad nomen; Bern, Archives Fédérales, Séances du Conseil Fédéral, Département de l’Intérieur, 1899; Claire Fischer, Claude Mercier and Claude Raffestin, ‘Entre la politique et la science, un géographe genevois: William Rosier’, Le Globe 143 (2003): 13‒25.

8. Reclus, Nouvelle Géographie universelle (see note 2), 19: 25, 87.

9. ‘M[aison] d’un Paraguayen’.

10. D. Graham Burnett, Masters of All They Surveyed: Exploration, Geography and a British El Dorado (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 2000), 2.

11. Switzerland stood out, according to some historians, for its ‘oblique colonialism’. See Yves Froidevaux, ‘Nature et artifice: village Suisse et village nègre à l’exposition nationale de Genève—1896’, Revue Historique neuchâteloise (2002): 17‒33; Patrick Minder, La Suisse coloniale? Les représentations de l’Afrique et des Africains en Suisse au temps des colonies (1880‒1939) (Neuchâtel, Université de Neuchâtel, 2009); Roland Ruffieux, ‘La Suisse des Libéraux’, in Nouvelle Histoire de la Suisse et des Suisses (Lausanne, Payot, 1984), 599‒666.

12. Federico Ferretti, Élisée Reclus, pour une géographie nouvelle (Paris, CTHS, 2014), 211‒68.

13. The outcome was published in Mémoire contenant l’exposé des droits de la France dans la question des frontières de la Guyane française et du Brésil, soumise à l’arbitrage du gouvernement de la Confédération suisse (Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 1891); Réponse du gouvernement de la République française au Mémoire des États-Unis du Brésil sur la question de frontière, soumise à l’arbitrage du gouvernement de la Confédération suisse (Paris, Imprimerie Nationale, 1899).

14. Sentence du Conseil fédéral suisse (see note 4), 463. ‘Les cartes géographiques expriment les opinions et les connaissances, plus ou moins limitées, de celui qui les a construites; mais elles ne retracent pas l’état des découvertes. Ce que l’on trouve figuré sur les cartes (et c’est surtout le cas de celles des XIVe, XVe et XVIe siècles), est un mélange de faits avérés et de conjectures présentées comme des faits’.

15. Reclus, Nouvelle Géographie universelle (see note 2) 86. ‘Quel est ce fleuve Yapok ou Vincent Pinzon que les diplomates d’Utrecht, ignorants des choses d’Amérique, voulurent indiquer sur leurs cartes rudimentaires? … On emplirait les bibliothèques de mémoires et documents diplomatiques publiés sur cette insoluble question’.

16. Sentence du Conseil fédéral suisse (see note 4), 713. ‘Par conséquent, il ne faut en tout cas chercher le Vincent Pinçon des anciens cartographes ni dans le Canal, ni dans la rivière de Carapaporis’.

17. Ibid., 720. ‘N’existe pas, et il n’a jamais existé’.

18. Ibid., 820. ‘La souveraineté du Brésil, notamment dans la vallée du Rio Branco, est reconnue par la population. Dans son ouvrage La France équinoxiale, Coudreau dit à ce sujet: “Nous ne pouvons plus aujourd’hui faire valoir nos prétentions jusqu’au rio Branco; le rio Branco ne saurait être contesté, car les Brésiliens l’exploitent et le peuplent”. Élisée Reclus confirme cette déclaration dans le passage suivant: “Toutefois le débat n’a d’importance réelle que pour le contesté de la côte, entre l’Oyapock et l’Araguary. À l’ouest, toute la vallée du rio Branco est devenue incontestablement brésilienne par la langue, les mœurs, les relations politiques et commerciales”’.

19. Archives diplomatiques de Nantes, Deputations Archives, Rio de Janeiro, Dossier 105, Franco-Brazilian Border Dispute, Correspondence of the Minister, Mr. Pichon, fol. 26, 23 August 1896.

20. Carlo Romani, ‘Algumas geografias sobre a fronteira franco-brasileira’, Ateliê Geográfico, 2:1 (2008): 43‒64 (http://www.revistas.ufg.br/index.php/atelie/article/view/3896/3580).

21. Élisée Reclus, Écrits Sociaux (Geneva, Héros-limite, 2012), 243. ‘Contre toutes ces bornes, symboles d’accaparement et de haine ! Nous avons hâte de pouvoir enfin embrasser tous les hommes et nous dire leurs frères!’

22. Sébastien Benoit, Henri Coudreau (1859‒1899) (Paris, L’Harmattan, 2000), 123.

23. Carlo Romani, Aqui começa o Brasil, história das gentes e dos poderes na fronteira do Oiapoque (Rio de Janeiro, Multifoco, 2013), 99‒100.

24. Bibliothèque nationale de France, NAF 22914, H. Coudreau to E. Reclus, [Pará] 18 February 1896, fol. 65.

25. Bibliothèque publique et Universitaire de Neuchâtel, Département des Manuscrits, MS 1991/10, E. Reclus, to Ch. Schiffer, Brussels, 30 April 1903.

26. Reclus, Nouvelle Géographie universelle (see note 2), 19: 797.

27. Ibid., 19: 1, 2, 15, 25, 47. Coudreau is quoted 59 times in this volume.

28. Nelson Sanjad, A coruja de Minerva: o Museu Paraense entre o Império e a República (1866‒1907) (Rio de Janeiro, Fiocruz, 2010), 307. ‘Um grande resumo das ideias de Coudreau’.

29. Federico Ferretti, ‘“They have the right to throw us out”: Élisée Reclus’ New Universal Geography’, Antipode, A Radical Journal of Geography, 45:5 (2013): 1337‒55.

30. Reclus, Nouvelle Géographie universelle (see note 2), 19: 72. ‘De toutes les possessions d’outre-mer que la France s’attribue, nulle ne prospère moins que sa part des Guyanes: on ne peut en raconter l’histoire sans humiliation. L’exemple de la Guyane est celui qu’on choisit d’ordinaire pour démontrer l’incapacité des Français en fait de colonisation’.

31. Ibid., 19: 73. ‘Sans méthode et sans humanité …]De 8 372 [travailleurs] engagés dans la force de l’âge, 4 522 sont morts en 22 années de 1856 à 1878‘.

32. Ibid., 19: 47. ‘Plus de la moitié des peuplades citées par les anciens auteurs a disparu’. David Lowenthal has also observed that, of the three Guianas, it was French Guiana that remained the most sparsely populated not only because of the environmental obstacles but also because of the political choices, namely the establishment of the penal colony (David Lowenthal, ‘Population contrasts in the Guianas’, Geographical Review 50:1 (1960): 41‒58).

33. Bibliothèque nationale de France, NAF, 16798, fol. 80, E. Reclus to P. Pelet, Clarens, 7 December 1884. ‘Y compris celui de nous mettre à la porte’.

34. Paul Vidal de La Blache, ‘Le contesté franco-brésilien’, Annales de Géographie 10:49 (1901): 68. ‘Le procès se dénoue à notre détriment’.

35. Guy Mercier, ‘La géographie de Paul Vidal de la Blache face au litige Guyanais: la science à l’épreuve de la justice, Annales de Géographie 667:3 (2009): 294‒317; Augustin Bernard, ‘Le contesté Franco-Brésilien’, Questions diplomatiques et coloniales, revue de politique extérieure 1 (1901): 31‒37.

36. ‘Arbitrage Franco-brésilien’, Journal de Genève, 7 December 1900: 1. ‘Si la Suisse a des intérêts vitaux et essentiels avec l’une des parties en cause, ce n’est pas avec le Brésil, mais bien avec la France’.

37. Luciene Carris Cardoso, ‘A visita de Élisée Reclus à sociedade de Geografia do Rio de Janeiro’, Revista da Sociedade Brasileira de Geografia 1 (2006), http://www.socbrasileiradegeografia.com.br/revista_sbg/luciene%20p%20c%20cardoso.html; Milton Lopes, ‘Élisée Reclus e o Brasil’, GEOgraphia 11:21 (2009): 160‒75 (http://www.uff.br/geographia/ojs/index.php/geographia/issue/view/23); Marcelo Augusto Miyahiro, ‘O Brasil de Élisée Reclus: territorio e sociedade em fins do século XIX’ (unpublished Master of Arts dissertation, São Paulo University, 2011).

38. José Maria da Silva Paranhos Júnior (1845‒1912), Baron Rio Branco, was one of the most famous Brazilian politicians and diplomats in the first years of the Brazilian Republic. His skill in resolving diplomatic matters in favour of Brazil, such as the frontier disputes with France, Great Britain and Argentina, earned him a reputation as ‘the Brazilian Bismarck’. The correspondence with Reclus is in Rio De Janeiro at the Arquivo Histórico de Itamaraty, Correspondence Rio Branco, Baron Rio Branco to E. Reclus, Paris, 19 June 1893.

39. José Pereira de Graça Aranha (1868‒1931) was a member of the progressive Brazilian bourgeoisie during the first years of the Brazilian Republic (proclaimed in 1889). He never forgot his youthful sympathy with anarchism, and continued to read and admire the anarchist geographers Pyotr Kropotkin and Reclus.

40. Maria Helena Castro Azevedo, Um senhor modernista: biografia de Graça Aranha (Rio de Janeiro, Academia Brasileira de Letras, 2002), 75‒77. ‘Reclus aceita o encargo, no intuito de opor-se aos interesses dos ingleses para aquela passagem para o Amazonas, onde pretendiam fazer um camino de ferro; também a ele a ele a região interessava muito pessoalmente, na medida em que deseja a América para os americanos’.

41. Benedict Anderson, Under Three Flags: Anarchism and the Anti-Colonial Imagination (London, Verso, 2007). The place of geographical and cartographical issues in such struggles seems to me to merit further exploration.

42. For a similar treatment of Vidal the la Blache’s Tableau de la Géographie de la France (1903), see Marie-Claire Robic, ed., Le Tableau de la géographie de la France de Paul Vidal de la Blache: dans le labyrinthe des formes (Paris, CTHS, 2000).

43. See David Alejandro Ramirez Palacios, ‘Élisée Reclus e a geografia da Colômbia: cartografia de uma interseção’ (unpublished Master of Arts dissertation, São Paulo University, 2010), http://www.teses.usp.br/teses/disponiveis/8/8136/tde-06102010-093308/pt-br.php; Élisée Reclus and Francisco Javier Vergara y Velasco, Colombia, traducida y anotada per F. J. Vergara y Velasco (Bogota, Matiz, 1893); Élisée Reclus,Estados Unidos do Brazil, geographia, ethnographia, estatistica, por Élisée Reclus. Traducção e breves notas de B. F. Ramiz Galvão, e annotações sobre o territorio contestado pelo barão do Rio Branco (Rio de Janeiro, Garnier, 1900).

44. Euclides de Cunha, Os Sertões (Rio de Janeiro, 1902). See Luciana Murari, Brasil, ficção geográfica: ciência e nacionalidade no país dos Sertões (São Paulo, Annablume, 2007); Denis Rolland, ‘Comprendre les enjeux d’un conflit et de ses représentations’, in Le Brésil face à son passé: la guerre de Canudos, ed. Isabelle Muzart-Fonseca dos Santos and Denis Rolland (Paris, L’Harmattan, 2005): 8.

45. Brian Harley, ‘The map and the development of the history of cartography’, in The History of Cartography, vol. 1: Cartography in Prehistoric, Ancient, and Medieval Europe and the Mediterranean, ed. J. B. Harley and David Woodward (Chicago, University of Chicago Press, 1987), 14.

46. Brian Harley, The New Nature of Maps (Baltimore, The Johns Hopkins University Press, 2001), 79.