ABSTRACT

Twenty-first century graduates need to have the aptitude to be critical thinkers and capacity to make balanced judgements. The undergraduate dissertation (capstone/independent research project) is normally undertaken at the end of the degree programme enabling students to demonstrate their ability to apply, analysis, synthesis and evaluate their knowledge. Despite the pedagogical importance of the dissertation and the implication of them for the undergraduate student experience, much of the literature on dissertations focuses on: design, structure and implementation; teaching and learning strategies; assessment criteria and marking standards; and, students’ development of subject-specific skills, personal attributes and transferable skills. However, the question remains how best to support and motivate undergraduate students in the final stages of the dissertation “write-up” process. This paper investigates and assesses the use of “writing retreats” within the final stages of the undergraduate dissertation process. Despite the benefits of writing retreats, they have to date typically only been offered to academic and research staff and postgraduate research students but not undergraduate students. This paper demonstrates that writing retreats are a feasible intervention tool that facilitates attitudinal changes, such as enhanced motivation, increased confidence and a more positive outlook on the final writing process of their independent research projects.

Introduction

“Dissertations have had a long history in geographical higher education, being widely regarded as the pinnacle of an individual’s undergraduate studies and the prime source of autonomous learning”

Boud (Citation1981), cited in Gold et al. (Citation1991, Chapter 8)

It has been recognised that there is a need for graduates in the twenty-first century to have the aptitude to be critical thinkers and make balanced judgements about the information that they find and use (Harvey et al., Citation1997; Stefani et al., Citation2000; Hager & Holland, Citation2006; Solem et al., Citation2008; Spronken-Smith, Citation2013; Spronken-Smith et al., Citation2016). The undergraduate dissertation,Footnote1 also known as a capstone project, is an independent research project that is undertaken at the end of the degree programme that enables students to demonstrate their ability to apply, analyse, synthesis and evaluate their knowledge i.e. “students as producers of knowledge” (Boud, Citation1981; Healey et al., Citation2013), promoting lifelong learning through the construction of a range of graduate attributes (Whalley et al., Citation2011; Blanford et al., Citation2020; Thomas et al., Citation2014; Mossa, Citation2014; Hovorka & Wolf, Citation2019). Graduate attributes have been defined as “the qualities, skills and understandings a university community agrees its students would desirably develop during their time at the institution and, consequently, shape the contribution they are able to make to their profession and as a citizen” (Bowden et al. Citation2000, as cited in Bridgstock, Citation2009, p. 32) i.e. graduates are seen as “global citizens”.

Degree programmes in the UK are subject to “benchmarking standards”. These standards are set out by the Quality Assurance Agency for Higher Education (QAA). Within the QAA standards the dissertation is often seen as a hallmark of undergraduate degree programmes. For Geography degree programmes, the QAA (2019, p. 10) notes:

“Within most Honours degree courses in Geography, it is anticipated that some form of independent research work is a required element. Students experience the entire research process, from framing enquiry to communicating findings. Independent research is often communicated in the form of a dissertation in the later stages of the course.”

Whilst the emphasis here is on the Geography dissertation, undergraduate independent research projects are seen as an important part of many degree programmes across many countries, as Scott (2002, pp.13 – as cited in (Walkington et al., Citation2011, p. 316)) notes, “in a ‘knowledge society’ all students – certainly all graduates – have to be researchers.” Dissertation practices however differ (in terms of length, timing and the number of module credits) from discipline to discipline, institution to institution and country to country (Hill et al., Citation2011). For example, in the US, The Boyer Commission, founded in 1995, produced a blueprint document for US higher education institutions on the structure of undergraduate programmes in research led-institutions and recommended that all undergraduate degree programmes should culminate in a capstone project (Boyer Commission, Citation1998). In Europe, similar studies have also documented the strengths of students being engaged in research (Committee on Higher Education, Citation1963; Elsen et al., Citation2009; Healey, Citation2005a, Citation2005b; Healey & Jenkins, Citation2006, p. Citation2009; Jenkins et al., Citation2007), with the integration of teaching and research – interconnected through the “teaching research nexus” – seen as fundamental to current higher education programmes and represented as “research-based curricula” (Hattie & Marsh, Citation1996; Healey & Jenkins, Citation2009; Speake, Citation2015). Both at the national and international level, independent research projects are seen as a critical component of many undergraduate (and postgraduate) degree programmes and can represent a significant component of the final degree assessment (Hill et al., Citation2011). Furthermore, dissertations are seen as a successful tool that can be used to promote the connection between teaching and research, empowering the learner (i.e. the student) and “talent spotting” (i.e. identification of potential postgraduate research students thus increasing the retention of students in research) (Marshall, Citation2009; Brew & Mantai, Citation2017). In addition, the discussion in the literature of the use of dissertations as a means for “talent spotting” so-called “strong” students for postgraduate degree programmes has also considered the process of dissertations in terms of encouraging more students in general, not just those that are considered to be “strong” students, to consider continuing in research, as the dissertation experience can increase the links between staff research, staff teaching and student learning and enhance the students’ engagement in the research culture of the institution (Haigh et al., Citation2015).

UK undergraduate dissertations are typically between 8,000–12,000 words in length and are often the first time students undertake a fully independent project, from designing, implementing and producing a piece of research, that enables students to explore their own subject-specific interests and consolidate their own academic disciplinary identities (Harrison & Whalley, Citation2008; Hill et al., Citation2011). The design and production of the dissertation is a time-consuming process. In the U.k. undergraduate dissertations are typically undertaken across the second and third years of study (Gatrell, Citation1991); the summer of the second year enables data collection to be undertaken and initial analysis of findings. Each institution has its own specific guidelines and regulations about the completion and final submission of the dissertation, most permit a minimum of 12 months to complete the dissertation and hand-in, some a maximum of up to 18 months (Parsons & Knight, Citation2015). The central position long held by the dissertation in many institutions’ undergraduate degree programmes and the time afforded to it reflects the importance it is seen to have as a tool for student learning, assessment and lifelong learning (Harrison & Whalley, Citation2008). One of the major challenges in the undergraduate dissertation is the balance in the provision of sufficient and continuous support to students for the design, implementation and production of their independent projects due to the autonomous element of the dissertation i.e. the dissertation being an example of “student-centred learning”. For the student, despite a lengthy period of supervision (~ 12–18 months) and the requirement of twenty-first century graduates to be independent and confident self-directed learners, students can still struggle to feel confident and motivated in the final editing, formatting, and write-up stages of their undergraduate dissertation. Despite the pedagogical importance of the dissertation and the implication of them for the undergraduate student experience, much of the literature on dissertations focuses on: the design and implementation of (subject-specific) dissertations (e.g. Parsons & Knight, Citation2015; Peters, Citation2017), the teaching and learning strategies used in dissertation modules (e.g. Harrison & Whalley, Citation2008; Todd et al., Citation2006), the assessment criteria and marking standards of dissertations i.e. quality assurance (e.g. Nicholson et al., Citation2010; Pathirage et al., Citation2007; Pepper et al., Citation2001; Webster et al., Citation2000), the structure, style and format of dissertations (e.g. traditional dissertations vs. forward-facing dissertations, such as the use of portfolios and undertaking work-based projects) (e.g. Harrison & Whalley, Citation2008; Healey et al., Citation2013; Hill et al., Citation2011), and the students’ development of subject-specific skills, personal attributes and transferable skills. However, the question remains as to how best to support and motivate undergraduate students in the final stages of the dissertation write-up process.

The research undertaken in this paper is focused on addressing the gap in the literature on the facilitation of students’ confidence and motivation in the final stages of the dissertation write-up process. This paper investigates and assesses the use of writing retreats within the final stages of the undergraduate dissertation process, it describes the format and the structure of the retreat and presents the methodological approach taken, before presenting its main findings and recommendations. More specifically, the objectives of this paper are:

to assess if the use of writing retreats for undergraduate students can facilitate a safe and supportive environment through the construction of protected time and space that is intended to afford dedication to the final editing, formatting, and write-up stages of the dissertation; and,

to examine if the introduction of writing retreats can foster attitudinal changes such as increased confidence, enhanced motivation and a more pleasurable final write-up stage for undergraduate dissertation students through the potential removal of feelings of isolation through the construction of communities of practice.

The use of writing retreats

Academic writing retreats

Fundamental to all academic careers is communication, in particular written communication, this comes in a number of different formats, from the initial doctoral thesis through to the construction of conference papers, journal papers and books (Cameron et al., Citation2009). However, one major challenge facing many academic scholars is finding the time and space to write. Murray (Citation2014, p. 57) defines a writing retreat as being “an obvious way to make time and space for writing. It provides dedicated writing time”. Furthermore, retreats are designed to create more than just protected time and space to write (i.e. uninterrupted time), they are also designed to create an atmosphere of trust and empowerment (Grant & Knowles, Citation2000), increased motivation (Moore, Citation2003; Petrova & Coughlin, Citation2012), build a community of support (Murray, Citation2014) and have the potential for transformational learning – e.g. the process of deep, constructive and meaningful learning that can change an individuals’ beliefs, attitudes and feelings – for all those that attend. Since the use of writing retreats for academic and research staff and postgraduate research students have been documented in detail in the literature (see for example, Aitchison & Guerin, Citation2014; Kornhaber et al., Citation2016; Tremblay-Wragg et al., Citation2020; Wittman et al., Citation2008) and as it is not the purpose of this paper to repeat these listings, the range of common benefits for those that attend the retreats in the Higher Education sector are discussed in brief. The literature suggests that the main focus of an academic writing retreat is ‘writing’, however, the so-called academic writing retreat model (including structured, semi-structured and unstructured retreats) has also proven to be successful for a myriad of organisational (e.g. allocation of resources and follow-up support), personal (e.g. increased motivation, confidence, engagement and pleasure in writing and reduced writing-related anxiety) and professional (e.g. increased writing skills, teamwork and the development of a community of writers) outcomes (Kornhaber et al., Citation2016). Furthermore, Grant and Knowles (Citation2000) have stated that instead of the practice of academic writing being seen as an autonomous and isolated act that is undertaken at home or in an office, it should be reframed to be seen as more of a community-based, collaborative and social experience. The formation of a community “creates a social space in which participants can discover and further a learning partnership related to a common domain” (Wenger et al., Citation2011, p. 10), therefore becoming a resource for those that attend the retreats in the future in the form of a shared practice i.e. a process for collaborative and cooperative learning.

The implementation of academic writing retreats has been revealed to be a useful and helpful strategy in order to manage productive writing time as well as to increase confidence in the process of writing itself (i.e. through identification as a “writer”) and collegiality; all retreats regardless of their structure (e.g. structured, semi-structured and unstructured retreats), include three fundamental inter-connected features: a shared writing space, a shared writing time and peer discussion. Despite the benefits of writing retreats, they are typically only offered to academic and research staff (Cameron et al., Citation2009; Kornhaber et al., Citation2016; Moore, Citation2003) and postgraduate research students (Ciampa & Wolfe, Citation2019), but to date NOT undergraduate students, however, communication remains a core undergraduate transferable research skill and forms part of many of the desired graduate attributes. Furthermore, recent studies of using writing retreats for academic and research staff and postgraduate research students have demonstrated the many positive benefits of running such retreats, therefore, providing a solid basis in order to investigate the use and success of writing retreats for undergraduate students.

Undergraduate student writing retreats

Many undergraduate students face dissertation writing feeling unprepared (Todd et al., Citation2004), after all it has been stated that students are not explicitly trained to be professional writers (Delyser, Citation2003), therefore the transition from student to independent researcher/scholar can be a challenging process for some students. Furthermore, many students feel isolated while writing their dissertation, this is often also combined with a lack of confidence in the writing and editing process and feeling unsupported, despite the structured lengthy supervision support students receive (~ 12–18 months). The self-directed independent learning element of the dissertation project can lead to a difference in expectations between the student and supervisor, this can have an impact on the students’ satisfaction of the supervisory role and ultimately their own work (Del Río et al., Citation2018); as Brew and Mantai (Citation2017, p. 554) commented “the relationship between supervisor and student are essential factors in a positive research experience.” Writing retreats help address some of the challenges presented within the undergraduate writing process, as Delyser (Citation2003, p. 170) states:

“We treat writing as if it were an innate talent, something we are simply able to do well – or not. Luckily that is not the case, for writing like carpentry, gymnastics and drawing, is only partially talent-determined. Like the other three, writing is also a skill and a craft. It can be learned and practiced, honed and sharpened, practiced some more and perhaps even nearly perfected.”

Retreats can act as scaffolding and help offset the feeling of isolation in the final write-up stage of the dissertation. Students attending a retreat have a shared common goal, in this example to complete their dissertation, this can create a collaborative, collegial and supportive community in which students become aware that the challenges and struggles of the final write-up stage of the dissertation are also shared by their peers’ (Moore, Citation2003). This has the potential to increase confidence and motivation, reducing the feeling of isolation and the perception of being “cast adrift” (Shadforth & Harvey, Citation2004). Although writing retreats are not a new concept, as aforementioned there have been numerous studies on the use and structure of retreats for academic and research staff and postgraduate research students generating a vast literature enabling the benefits and challenges of such retreats to be explored and brought into focus, however, there appears to have been little investigation or empirical research on the potential benefits and the use of writing retreats for undergraduate students.

Institutional setting

The University of Liverpool (UK), where the research took place, is a large teaching and research-based institution. The Geography (BA and BSc) and Environmental Science (BSc) degree programme intakes are typically around 250 and 35 students per year and are accredited by the Royal Geographical Society and Institution of Environmental Sciences respectively, both of which have clear expectations that programmes should clearly contain “individual research projects” as part of the programme structure (RGS, Citation2017, p. 9). The dissertation projects are undertaken by students in their final years of study and address many of the specific graduate attributes identified within The University of Liverpool’s Institutional Education Strategy 2026 and Curriculum 2021 Framework (University of Liverpool, Citation2016a, Citation2016b), in particular, the Liverpool Hallmarks focused on “research-connected teaching” and “active learning” and the Liverpool Graduate (subject-specific) attributes focused on “confidence” and “digital fluency”.

In the Department of Geography and Planning, School of Environmental Sciences, at The University of Liverpool, the deadline for Geography undergraduate dissertation submission is in the third week of the second semester in the third year. In 2018/19, The University of Liverpool made an institutional decision to make an alteration to the main “exam” period, shifting from a designated two-week period to a three-week period. This institutional shift in the “exam” assessment period resulted in the submission deadlines of both continuous, and other forms of assessment, not being permitted in this time period, for strong pedagogic reasons, therefore the deadline for Geography undergraduate dissertation submission moved from the thirteenth week of the first semester (~ early January) in the third year to, the third week of the second semester in the third year (~ early February). This change to the deadline for Geography undergraduate dissertation submission has resulted in a “gap” between the end of the 18 month dissertation supervision period at the end of the first semester in the third year and the final submission hand-in deadline (~eight weeks) where students do not receive supervision. In order to address this “gap” a dissertation writing retreat has been designed and established in the third year undergraduate students timetable during this “gap” period. Those students that had chosen to undertake module ENVS321 (Geography Dissertation) – a compulsory module for Geography (BA and BSc) and Environmental Science (BSc) students and an optional module for Geography and Planning (BA) and Combined Honours (BA and BSc) students – were informed of this new and novel dissertation writing retreat in early November so that they could build it into their dissertation write-up plan, though it was explicitly explained to the students that the retreat was not an opportunity to receive additional supervisory support, rather a chance to “polish” their dissertation drafts through structured dedicated writing time in a safe and supportive environment, facilitated by members of staff, and address formatting and technical questions.

Research methods

The optional dissertation writing retreat for third year Geography (BA and BSc) and Environmental Science (BSc) undergraduate students was held on-campus at The University of Liverpool in the Department of Geography and Planning building. All students registered on the dissertation module (n = 292) were invited to attend the retreat. In total ~100 students (>30% of the 2019/20 module cohort) attended the retreat across the two days; more students attended on day two (~60% of the retreat participants), however no formal list or register was taken as the retreat had intentionally been designed to be both open and informal in structure to encourage student participation (Massingham & Herrington, Citation2006). Some students attended on either day one or two, however a large group of students attended on both days.

The writing retreat was structured with the following ethos in mind and influenced by the Communities of Practice (CoP) learning theory (Lave & Wenger, Citation1991; Wenger, Citation1998) and Containment Theory (Murray, Citation2014): to create a safe atmosphere for productive writing; to help create an environment of peer support and build a community of support (i.e. foster collegial relationships) both during the retreat and beyond to increase individual confidence and motivation; to explore behavioural and attitudinal changes that result in transformational learning; and, to produce a more positive and enjoyable experience of the final write-up stage of the dissertation. The introductory session at the beginning of each day encouraged students to actively engage and contribute to the retreat on an individual – and peer-level. Following this, the remaining parts of the two days were structured around discrete periods of set activities including question sessions where students could discuss dissertation formatting and technical issues with members of staff and also interact, share ideas and have discussions with their peers attending the retreat. There were so-called “silent” focused writing time – this took up a large proportion of each day – and scheduled breaks for refreshments and a chance for a change of scene. The retreat adopted a “typing pool” model (Murray & Newton, Citation2009) e.g. all students wrote together in the same room for the duration of the retreat (co-located writing) and the retreat included a series of fixed time-periods for writing and question sessions, as aforementioned. Furthermore, the retreat included the use of “expert facilitators” present for the duration of the retreat in the form of a range of academic members of staff from each of the different broad research areas (e.g. Environmental Change; Planning, Environmental Assessment and Management; Geographic Data Science; and, Power, Space and Cultural Change) representing a range of career stages in the Department of Geography and Planning.

The use of the writing retreat in supporting Geography (BA and BSc) and Environmental Science (BSc) undergraduate independent research projects has been assessed using questionnaires, completed by the third year undergraduate students after the attendance of the retreat. Students attending the dissertation writing retreat were provided with a paper copy of the questionnaire on their arrival, or as soon as possible thereafter, by the author or by colleagues in attendance of the retreat, and asked to return their completed questionnaires into a post-box based in the room at any stage during the day; this enabled students to be free to choose where and when they filled-in their questionnaire. The self-completion questionnaire, reproduced as , contained a range of “open” and “closed” questions. The use of “open” question enables the respondent (i.e. in this example the student) to control the length of their answer and the type of information that is included, the question tends to be short and the answers tend to be longer (Denscombe, Citation2014). In contrast, the use of “closed” structured questions enables the researcher to collect standardised data from a range of identical questions in order to compare participant responses (Denscombe, Citation2014). The success of research questionnaires depends on three inter-connected factors:

the response rate

(i.e. how many are returned to the researcher);

(2) the completion rate

(i.e. how many are returned fully completed to the researcher); and,

(3) the reliability of responses

(i.e. how many of those returned to the researcher are truthful and accurate responses).

Table 1. Questionnaire completed by third year undergraduate students after the attendance of the dissertation “writing retreat”.

In recent times there has been much discussion around the increasing non-response rates of student questionnaires and surveys in the Higher Education sector. There are a number of factors that may have an impact on response rates of student questionnaires, such as: the length of the questionnaire, the timing of the questionnaire, the mode of the questionnaire (e.g. paper-based or digital), engagement of students and the treatment of responses (e.g. confidentiality) (Coates, Citation2006; Dillman et al., Citation2014; Dommeyer et al., Citation2004; Nair et al., Citation2008; Porter et al., Citation2004). Furthermore, another factor that has an impact on student response rates in the Higher Education sector is so-called “questionnaire fatigue”, the over-surveying of students (Porter et al., Citation2004; Sharp & Frankel, Citation1983); this issue has been raised by undergraduate Geography (BA and BSc) and Environmental Science (BSc) students at The University of Liverpool during the internal Staff-Student Liaison Committees (SSLC), held twice each semester. In order to reduce the potential issue of “questionnaire fatigue” and increase the response rate, the design of the self-completion questionnaire remained simple in order to make the answering of the questions as straightforward and easy as possible, whilst maintaining a high-level of detail collected (Denscombe, Citation2014). The self-completion questionnaire included seven questions in total; three “open” questions (including a free comments section) to collect students’ opinions on the concept of the dissertation writing retreat, the individual preparation undertaken before attending the retreat and how they felt the dissertation writing retreat could be amended for subsequent years i.e. forward facing feedback; and, four “closed” questions based on a five-point Likert scale, that attempted to collect information on the success of the dissertation writing retreat in fostering a more positive writing experience. Before completing the questionnaire, all participants received an information sheet that contained details on the research being undertaken (i.e. the purpose of the questionnaire), how the information would be used, reassurance that that information that they provided would remain anonymous and that all responses were voluntary (i.e. they were under no obligation to answer the questions). The research undertaken in this paper received ethical approval from The University of Liverpool.

The analysis of the questionnaire responses explored the four “closed” questions through a statistical analysis of the strength of the response, with percentages for each Likert class calculated. Responses to the three “open” questions were assessed using a thematic analysis of the responses based on broad thematic themes identified from the literature.

Results and discussion

In total, 75 completed questionnaires were returned across the two days of the writing retreat (including no duplications), with the break-down of the declared degree programmes of the attendees including: 41 Geography (BA) students, 24 Geography (BSc) students, 2 Geography and Planning (BA) students, 1 Environmental Science (BSc) student and, 1 Combined Honours (BA or BSc) student. This split of the attendee’s degree programme registrations crudely reflects the proportional number of students undertaking each of those specific degree programmes (Geography (BA and BSc), Environmental Science (BSc), Geography and Planning (BA) and Combined Honours (BA and BSc).

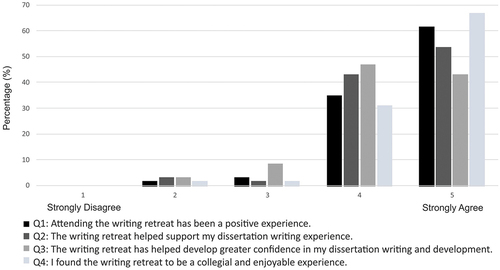

The first four “closed” questions of the questionnaire based on the five-point Likert scale (5 – strongly agree, 1 – strongly disagree), all indicate that the majority of students (>85%) after attending the retreat felt it had been a beneficial experience (see ). The first question (Q1) attempted to assess if students found the retreat a positive experience and resulted in 96% stating that they Strongly Agree or Agree that the retreat had been. In total, 96% of the students responded Strongly Agree or Agree to question two (Q2) – “The writing retreat helped support my dissertation writing experience”. Question three (Q3) in the questionnaire had a response of Strongly Agree or Agree from 89% of respondents that the retreat had been helpful in increasing their confidence in the final write-up and editing stages of the dissertation process and, question four (Q4) – “I found the retreat to be a collegial and enjoyable experience” – had a response of Strongly Agree or Agree from 97% of the participants. The meaning of these responses can be further explored and assessed in detail in terms of the three “open” questions included on the questionnaire (including a free comments section) that collected information on the students’ opinions on the general concept of holding a writing retreat to support the final write-up and editing stages of the dissertation process, the preparation undertaken before attending the retreat and how the retreat could be improved for subsequent years.

Figure 1. The student questionnaire responses to the “closed” research questions one to four (Q1-4) for the undergraduate dissertation writing retreat.

Protected and dedicated environments for “goal setting” and “writing”

The first of the “open” questions, question five (Q5), “What preparation did you undertake before attending the writing retreat (e.g. full draft completed) and what are you intending to do as a consequence of participating?” gathered some interesting responses. There is much detailed literature on the use and strengths of “goal setting” in successful completion of academic outputs, be that academic journal papers, undergraduate essays, or undergraduate and postgraduate dissertations (Grant & Knowles, Citation2000; Zimmerman, Citation2000; Moore, Citation2003; Grant, Citation2006; Murray & Newton, Citation2009; Moore et al., Citation2010; Swaggerty et al., Citation2011; Van Dinther et al., Citation2011; Girardeau et al., Citation2014). The setting of goals can range from larger-scale goals, such as completing the project (i.e. the final hand-in date, in this example of the dissertation) or smaller-scale goals, such as individual tasks that lead to the completion of the overall goal. The use of retreats can help in the setting of smaller (more specific)-scale goals thereby having the potential to reduce some of the feelings of anxiety linked to completing larger projects, such as dissertations, leading to increased motivation in the process, as one participant stated: “I relaxed a lot more over Christmas knowing that this was coming up”. Of those students that attended the dissertation writing retreat, 95% responded to Q5, and the main common theme that emerged in those responses centred around the notion of “goal setting”. In total, 63% of participants responses included statements indicating that they had prepared full or partial drafts of their dissertation before attending the retreat. For example, participants stated that they had “full draft[s] almost done”, “had fully completed drafts”, “majority of dissertation … written” and had focused on “specific parts” of their dissertation before attending. In addition, 19% of students commented that they had been through their dissertation and complied lists of questions on the format and structure of their dissertation ready to ask the retreat “expert” facilitators, for example: “[I] wrote down questions”, “Had … questions prepared”, “I came with a list of questions”.

The preparation undertaken by students before attending the retreat, such as compiling lists, can enable the identification of potential barriers or issues being faced and therefore increase self-awareness and motivation and foster attitudinal and behavioural changes through the realisation of those barriers and issues faced and enabling students to be open to the possibilities for making steps to amend them (Moore et al., Citation2010). In addition to the preparation undertaken by students beforehand, 18% of participants responses included statements indicating that they had attended the retreat for formatting support as comments included: “the retreat helped me with details and formatting of the dissertation” and “after [the retreat] I was able to know how to format my work”. One participant commented on the inter-related “knock-on” effect of the retreat and in particular the help on the formatting of the dissertation – “[the retreat was] very useful in making the format look professional and clear which builds on confidence in the run up to the deadline”.

The notion of “goal setting”, be that before or after a retreat, is a fundamental feature of implementing meaningful and productive writing time and feelings of accomplishment (Rosser et al., Citation2001), hence the importance of the design (e.g. timing, structure and format) of a writing retreat. In one sense the final structure of the dissertation writing retreat is determined by those students that attended the retreat (i.e. it is highly self-directed) in terms of the goals that they set beforehand and their desired outcomes from the retreat (Hamerton & Fraser, Citation2011). In addition, factors such as the length of time set aside for set “activities” (e.g. question sessions) and/or “contained” writing time (e.g. “silent writing”) combined with the physical space used for the retreat all contribute to the overall atmosphere and environment of the retreat. One participant indicated that the use of the Department of Geography and Planning building for the retreat was preferred over other areas for writing, such as the library, as they stated “I used [the retreat] as a comfortable focused environment – better than the library!” and another participant stated that the “GIC [the room in the Department of Geography and Planning building used for the retreat] was nice and quiet”.

A small number of students commented on the additional factors that had helped to create a safe and productive writing environment, such as the availability of refreshments (e.g. tea, coffee, soft-drinks and biscuits). This was not one of the questions on the self-completion questionnaire, however, four of the 75 respondents (5%) mentioned refreshments being an appreciated factor of the retreat, for example, one participant commented that they “loved the snacks” and another stated that the “tea/coffee/biscuits [had been] a good idea”. The use of structured, or “contained” time periods for focusing on the editing, structuring, and writing of the dissertation in the retreat alongside the use of regular scheduled breaks can lead to increased feelings of confidence in the students’ own competencies and foster a more positive attitude to the final write-up stage, as reflected in the responses to Q’s 1 and 2, through more productive behaviour i.e. having planned opportunities for breaks after “contained” time periods of writing can increase motivation to write in those more “structured” writing times (Kempenaar & Murray, Citation2016; Kern et al., Citation2014; Murray, Citation2014; Petrova & Coughlin, Citation2012; Silvia, Citation2007). In addition, the planned breaks can also lead to greater feelings of collegiality, as reflected in the response to Q4, through increased social interaction, collegiate connection and support also being a feature commented upon in the other two “open” questions.

Communities of practice

The second and third of the “open” questions – question six (Q6), “This is the first year we have tried running a dissertation writing retreat, would you suggest any changes for next year?”, and question seven (Q7), “Any further comments?” – had response rates of 73% and 20%, respectively. In response to Q6, 31% of participants of the retreat stated that they had no suggestions for improvements, and many commented on the success of the retreat:

(Q6) – “This is the first year we have tried running a dissertation writing retreat, would you suggest any changes for next year?”

“No, [it] was a good experience with lecturers around to help.”

“No, I think this is really helpful. I am really glad it has been introduced.”

“No, [it] was a great relaxed atmosphere where the balance between help and independent work was right.”

“No, everything worked well, staff were attentive and helpful … ”

“It has been so helpful … ”

The comments on the atmosphere created and the design of the retreat (balance between the question sessions and the “silent writing” sessions) from the quotations above correspond to the responses seen in Q’s 1, 2, 4 and 5. It has been stated that the skilled facilitation of the structured sessions ensures a smooth running of the retreat and enables sufficient support for participants (Hamerton & Fraser, Citation2011) and as demonstrated in the quotations for Q6, having access to “expert” facilitators – in the form of a range of academic members of staff – is one of the main strengths of the retreat held. However, some participants (16% of those that responded to Q6) did comment it would be beneficial to have more academic or postgraduate research students present for the duration of the retreat to increase contact time in the question sessions.

In considering the atmosphere created in the retreat one participant stated in their response to Q5 that the “ … retreat [had] allowed me to see how other people are getting on and pushing me to do more”. Retreats can create a sense of community between those that attend (Casey et al., Citation2013; Kent et al., Citation2017; Murray, Citation2014). This is because the members of the retreat are joined together by a shared-goal, in this example to complete their dissertation, and through the retreat the participants follow the same approach in doing so. This sense of community, built from the promotion of peer interactions and from the knowledge and understanding that others are experiencing similar challenges, can lead to increased confidence and motivation and help break the feeling of isolation in the final write-up stages of the dissertation through the creation of communities of practice (i.e. community of writers), and as reflected in the responses to Q’s 1 to 4. In addition, this can increase student satisfaction in the dissertation process.

The remaining responses to Q6 centred around the structure, scheduling and timetabling of the dissertation writing retreat. It has been aforementioned that the design of the retreat is important to its success and having a firm structure can contribute to ensuring a productive and support environment is established. Students attending the dissertation writing retreat had been informed prior to the retreat the start and end times but, the decision had been made not to include the complete structure beforehand; however one participant commented that it would be beneficial to communicate the full-structure of the retreat beforehand in particular “when staff are around”. This decision not to release the full-structure beforehand had been made to encourage students to attend the retreat for the range of sessions rather than for the just the staff-led question sessions for logistical reasons, thereby increasing the feasibility of running the retreat for a large cohort (~300 students). In addition, another participant suggested having some more additional focused activities throughout the retreat rather than just question and “silent writing” sessions, such as having “different seating [areas] with presentations [for] quantitative and qualitative [students by staff members]”. The structure of the retreat across the two days was the same, however, based on initial feedback from students at the end of day one that it would be helpful to see copies of past dissertations again (these are available throughout the semester for students to view, and it should be noted that for reasons of data protection no comments or marks are included on the copies), a minor amendment was made ahead of day two; this included setting up a “reading desk” for students to view copies of a range of past dissertations – an example of action on reflection. Furthermore, one participant commented at the end of the retreat that “it was useful to see past dissertations”.

In addition to the structuring comments and in considering the scheduling and timetabling of the retreat, 18% of the responses to Q6 suggested running additional retreats earlier in the semester and/or later in the semester, closer to the submission deadline, with a handful of responses (<5%) commenting on not holding them in the designated three week assessment period, and perhaps splitting them across a number of days rather than two consecutive days. Much of the literature on the design and planning of writing retreats considers the optimum duration of a retreat to be from two to five days (Kornhaber et al., Citation2016). If the retreat is shorter than two days or longer than five the benefits of such retreats for the participant can be impacted and the feasibility of the retreat can be affected through not just the availability of “expert” facilitators (i.e. restricted by timetabling and scheduling of other research, teaching and administrative duties), but also their willingness to attend for a pro-longed period of time (i.e. multiple days). It is intended in subsequent years that the dissertation writing retreat would not be held in the designated three week assessment period. Instead the retreat would be held after the exam period at the beginning of the second semester. The timetabling of the first retreat had been constrained by existing timetable activities; in the future timetabling of the retreat is planned to take place alongside the central institutional timetabling for the third year modules of the Geography (BA and BSc), Environmental Science (BSc), Geography and Planning (BA) and Combined Honours (BA and BSc) degree programmes.

The final “open” question on the questionnaire, Q7, as aforementioned, had a response rate of 20%. Most of these response (>87%) commented on the success of the retreat being included into the dissertation module, for example: “Good idea”, “Very useful”, “Thank you for the staff for taking the time out of [their] day to help us” and “Many thanks to all staff who gave up their time. It was brilliant and highly informative”. The remaining >10% of participant responses for Q7 centred back around the potential modifications that could be made for future years, in particular one student suggested the inclusion of “a suggestion box with questions answered in a group email/session after”. The idea of a “follow-up” session be that face-to-face or online is a useful consideration as this can help sustain the collegiate connection formed in the retreat and continue to foster increased confidence and motivation in the final write-up stages of the dissertation and enable students’ time to reflect on their experience (Petrova & Coughlin, Citation2012).

The benefits and recommendations of using writing retreats for undergraduate students

The results and findings of the questionnaires, completed by the third year undergraduate students after the attendance of the dissertation writing retreat that have been presented here have shown that participants found the retreat to be a productive experience, that enabled the construction of protected time and space for the final editing, formatting, and write-up stages of the dissertation in a trusted, safe and collegial environment that increased confidence, enhanced motivation through increased peer interaction and made it a more pleasurable final write-up stage of the dissertation. The creation of a friendly and relaxed atmosphere was appreciated by the students, at what can be a stressful time of the academic year – an element reflected in both formal and informal feedback from those that attended the retreat. Furthermore, a number of students identified that the retreat helped them focus their “writing” (e.g. preparation undertaken before attending the retreat) and enhanced their confidence and motivation in the final editing, formatting, and write-up stages of the dissertation. Despite the dissertation module handbook and documentation including detailed information on these elements, students seemed to appreciate the one-to-one reassurance of the formatting and structuring criteria i.e. increasing assessment literacy (Greenbank & Penketh, Citation2009). The students that attended the retreat also beneffitted from having increased contact-time in the newly esablished “gap” period where students do not normally receive supervision. In addition, in our role as lecturers or so-called “teachers”, it is often one of our main desires to create an inspiring environment for students in order to encourage deep “meaningful” active learning to take place and help in building a community of learners that “buzz” (Maguire & Edmondson, Citation2001), a feature that is both important for academic members of staff and students. There are also clear benefits to the academic members of staff holding these retreats not just the students, as the retreats offer an efficient and focused mechanism for addressing student concerns in relation to the dissertation and also act as a referral point for student questions that arise during the scheduled three week break and assessment period. Despite the numerous benefits of holding writing retreats that have been identified, there are some challenges and retreats do not remove all problems faced by third year undergraduate students completing their dissertation. In fact, a two-day retreat is a short-time to enable students to complete their final editing and writing, therefore it is important that the retreats help to develop techniques that can be used post-retreat to implement a structure to support students.

Recommendations for further research of the use of writing retreats in supporting Geography (BA and BSc) and Environmental Science (BSc) undergraduate students in the final write-up stages of the dissertation process include the continued assessment and reflection of the teaching and learning strategies used in undergraduate dissertation modules and the role that dissertation writing retreats can have in this as a permanent embedded part of the module structure. It should be noted here that due to the success of the retreat, it has been decided that in the Department of Geography and Planning, School of Environmental Sciences, Geography dissertation module (ENVS321) at The University of Liverpool, the retreat is going to be recognised as a permanent addition to the module structure and teaching and learning strategies used (it should be noted that due to the global COVID-19 pandemic it has not been possible to hold these in 2021). In addition, the relationship between success factors (such as the final dissertation mark attained) and the student attendance of the dissertation writing retreat could be an interesting consideration, however, this could impact on those students that choose to attend the retreat if a formal list of participants is taken to capture attendance records, as attendance of the retreat may appear as mandatory rather than optional. Furthermore, monitoring the sessions that are better attended (e.g. question sessions or “silent writing” sessions), might offer insights into the needs of the students that can then be embedded as part of the students’ own self-reflection.

It is important to also consider that the retreat received little criticism from those that attended and although the self-completion questionnaire contained a range of “open” and “closed” questions that created a richness of data, the research could benefit from additional data from focus groups of students that have the chance to reflect upon their own experience of attending the retreat, therefore increasing the use of the “student voice” (Slinger-Friedman & Patterson, Citation2012); though responses from the 2019/20 student module evaluation survey (EVASYS) for ENVS321 completed after the final “hand-in” deadline of the dissertation, and therefore after a period of reflection, had an additional 17 comments specifically mentioning the use and success of the retreats, for example: “[the] dissertation retreat was really good – I would suggest having maybe two retreats, one during exams and one after exams, a little more time before the deadline”, “The refining workshop was incredible – a massive thank you … calming input and support” and “[the] dissertation writing retreat was great and it was good to be able to speak to a variety of academics”. These comments reiterate the responses collected from the questionnaires, though have a greater degree of reflection in them.

Conclusion

In this paper it has been demonstrated from the insights gained from both holding the dissertation writing retreat and the responses from the questionnaires the central role that the use of writing retreats have in:

creating a safe and supportive collegial environment, for what is often a rather isolating and autonomous process;

facilitating student editing, formatting and writing through formal and informal feedback mechanisms; and,

fostering increased confidence and enhanced motivation, leading to potential behavioural and attitudinal changes that produce a more positive and enjoyable experience of the final write-up stage of the dissertation for third year undergraduate students.

Although the dissertation process described within this paper relates to Geography (BA and BSc) and Environmental Science (BSc) dissertations at The University of Liverpool, many degree programmes offer capstone projects that may benefit from the use of dissertation writing retreats, with the potential to be adopted across both the social and physical sciences, offering a valuable tool in dissertation support across a range of disciplines. The use of writing retreats are a feasible intervention tool for other disciplines (and the wider University as a whole) to consider using in order to facilitate attitudinal changes, such as enhanced motivation, increased confidence and a more positive outlook on the writing process of final-year undergraduate students in the completion of their independent research projects.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to acknowledge the support of their colleagues Drs Andrew Hacket-Pain (Dissertation Module Co-ordinator), Andrew Davies, Mark Riley, Paul Williamson and Professors Neil Macdonald and Andrew Plater, who all kindly agreed to attend the dissertation ‘writing retreats’ and by doing so all contributed to making it a success. The author would also like to thank the students of ENVS321 that attended the writing retreat and provided the feedback used within this study. Furthermore, the author would like to acknowledge the support of the Postgraduate Certificate in Academic Practice (PGCAP) team at The University of Liverpool for their invaluable support in the design, implementation and completion of the research in this paper and thank the two anonymous reviewers for providing detailed and thoughtful comments on the manuscript.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. The term dissertation is used throughout this paper, however, it is recognised by the author that there are a range of different terms used to describe the major independent research projects/reports undertaken by undergraduate students, such as capstone projects, honours projects and final-year projects.

References

- Aitchison, C., & Guerin, C. (2014). Writing groups for doctoral education and beyond innovations in practice and theory. Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group.

- Blanford, J., Kennelly, P., King, B., Miller, D., Bracken, T. (2020). Merits of capstone projects in an online graduate program for working professionals. Journal of Geography in Higher Education,44(1), 45–69. doi10.1080/03098265.2019.1694874

- Boud, D. (1981). Developing student autonomy in learning. Kogan Page.

- Bowden, J., Hart, G., King, B., Trigwell, K., & Watts, O. (2000). Generic capabilities of ATN university graduates. Canberra: Australian Government Department of Education, Training and Youth Affairs. http:html://www.clt.uts.edu.au/atn.grad.cap.project.index.

- Boyer Commission. (1998). Reinventing undergraduate education: A blueprint for america’s research universities. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED424840.pdf

- Brew, A., & Mantai, L. (2017). Academics’ perceptions of the challenges and barriers to implementing research-based experiences for undergraduates. Teaching in Higher Education, 22(5), 551–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2016.1273216

- Bridgstock, R. (2009). The graduate attributes we’ve overlooked: enhancing graduate employability through career management skills. Higher Education Research & Development,28(1), 31–44. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360802444347

- Cameron, J., Nairn, K., & Higgins, J. (2009). Demystifying academic writing: Reflections on emotions, know-how and academic identity. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 33(2), 269–284. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260902734943

- Casey, B., Barron, C. M., & Gordon, E. (2013). Reflections on an in-house academic writing retreat. AISHE-J - the All Ireland Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 5(1), 1041–10414. https://ojs.aishe.org/index.php/aishe-j/article/view/104

- Ciampa, K., & Wolfe, Z. (2019). Preparing for dissertation writing: Doctoral education students’ perceptions. Studies in Graduate and Postdoctoral Education, 10(2), 86–108. https://doi.org/10.1108/SGPE-03-2019-0039

- Coates, H. (2006). Student engagement in campus-based and online education: University connections. Routledge Taylor & Francis Group. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203969465

- Committee on Higher Education. (1963). Higher education: Report of the Committee appointed by the Prime Minister under the Chairmanship of Lord Robbins 1961-63. Her Majesty’s Stationary Office. http://www.educationengland.org.uk/documents/robbins/robbins1963.html

- Del Río, M. L., Díaz-Vázquez, R., & Maside Sanfiz, J. M. (2018). Satisfaction with the supervision of undergraduate dissertations. Active Learning in Higher Education, 19(2), 159–172. https://doi.org/10.1177/1469787417721365

- Delyser, D. (2003). Teaching graduate students to write: A seminar for thesis and dissertation writers. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 27(2), 169–181. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260305676

- Denscombe, M. (2014). The good research guide: For small-scale research projects (Fifth). McGraw Hill Education. https://eds-b-ebscohost-com.liverpool.idm.oclc.org/eds/ebookviewer/ebook/ZTAwMHR3d19fOTM3OTQ3X19BTg2?sid=1fd91afd-4e5b-413a-96ec-dfbe6bee7155@pdc-v-sessmgr03&vid=0&format=EB

- Dillman, D. A., Smyth, J., & Christian, L. M. (2014). Internet, mail, mixed-mode suvreys the tailored design method. Wiley.

- Dommeyer, C. J., Baum, P., Hanna, R. W., & Chapman, K. S. (2004). Gathering faculty teaching evaluations by in-class and online surveys: Their effects on response rates and evaluations. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 29(5), 611–623. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930410001689171

- Elsen, M., Visser-Wijnveen, G. J., van der Rijst, R. M., & van Driel, J. H. (2009). How to strengthen the connection between research and teaching in undergraduate university education. Higher Education Quarterly, 63(1), 64–85. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2273.2008.00411.x

- Gatrell, A. C. (1991). Teaching students to select topics for undergraduate dissertations in geography. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 15(1), 15–23. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098269108709125

- Girardeau, L., Rud, A., & Trevisan, M. (2014). Jumpstarting junior faculty motivation and perform- ance with focused writing retreats Journal of Faculty Development, 28(1), 33–40.

- Gold, J. R., Jenkins, A., Lee, R., Monk, J., Riley, J., Shepherd, I., & Unwin, D. (1991). Teaching geography in higher education. Chapter 8. Basil Blackwell, Oxford. https://gdn.glos.ac.uk/gold/ch8.htm

- Grant, B., & Knowles, S. (2000). Flights of imagination: Academic women be(com)ing writers. International Journal for Academic Development, 5(1), 6–19. https://doi.org/10.1080/136014400410060

- Grant, B. M. (2006). Writing in the company of other women: Exceeding the boundaries. Studies in Higher Education, 31(4), 483–495. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075070600800624

- Greenbank, P., Penketh, C. (2009). Student autonomy and reflections on researching and writing the undergraduate dissertation. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 33(4), 463–472. doi:10.1080/03098770903272537

- Hager, P., Holland, S. (Eds.) (2006). Graduate attributes, learning and employability. Springer

- Haigh, M., Cotton, D., & Hall, T. (2015). Pedagogic research in geography higher education. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 39(3), 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2015.1066317

- Hamerton, H., & Fraser, C. (2011). Writing Retreats to Improve Skills and Success in Higher Qualifications and Publishing Author Writing retreats: An overview, 1–11. Good Practice Publication Grant. www.akoaotearoa.ac.nz/gppg-ebook

- Harrison, M. E., & Whalley, W. B. (2008). Undertaking a dissertation from start to finish: The process and product. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 32(3), 401–418. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260701731173

- Harvey, L., Moon, S., Geall, V., Bower, R. (1997). Graduates’ work : organisational change and students’ attributes. University of Birmingham: Centre for Research into Quality (CRQ) and Association of Graduate Recruiters, Birmingham.

- Hattie, J., & Marsh, H. W. (1996). The relationship between research and teaching: A meta-analysis. source: Review of educational research (Vol. 66). Winter.

- Healey, M. (2005a). Linking research and teaching exploring disciplinary spaces and the role of inquiry-based learning. In R. Barnett (Ed.), Reshaping the university: New relationships between research, scholarship and teaching (pp. 67–78). McGraw-Hill Education.

- Healey, M. (2005b). Linking research and teaching to benefit student learning. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 29(2), 183–201. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260500130387

- Healey, M., & Jenkins, A. (2006). Strengthening the teaching‐research linkage in undergraduate courses and programs. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 2006(107), 45–53. https://doi.org/10.1002/tl.244

- Healey, M., & Jenkins, A. (2009). Developing undergraduate research and inquiry.:http://www.heacademy.ac.uk/assets/York/documents/resources/publications/DevelopingUndergraduate_Final.pdf

- Healey, M., Lannin, L., Stibbe, A., & Derounian, J. (2013). Developing and enhancing undergraduate final-year projects and dissertations: A National Teaching Fellowship Scheme project publication. The Higher Education Academy, 1–94.

- Hill, J., Kneale, P., Nicholson, D., Waddington, S., & Ray, W. (2011). Re-framing the geography dissertation: A consideration of alternative, innovative and creative approaches. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 35(3), 331–349. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2011.563381

- Hovorka, A., & Wolf, P. (2019). Capstones in geography. In H. Walkington, J. Hill, & S. Dyer (Eds.), Handbook for teaching and learning in geography (pp. 386–398). Edward Elgar Publishing. https://doi.org/10.4337/9781788116497.00038

- Jenkins, A., Healey, M., & Zetter, R. (2007). Linking teaching and research in disciplines and departments. The Higher Education Academy, 1–100. :https://www.advance-he.ac.uk/knowledge-hub/linking-teaching-and-research-disciplines-and-departments.

- Kempenaar, L. E., & Murray, R. (2016). Higher education research & development writing by academics: A transactional and systems approach to academic writing behaviours. Higher Education Research & Development, 35(5), 940-950. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1139553

- Kent, A., Berry, D. M., Budds, K., Skipper, Y., & Williams, H. L. (2017). Promoting writing amongst peers: Establishing a community of writing practice for early career academics. Higher Education Research & Development,36(6), 1194–1207. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2017.1300141

- Kern, L., Hawkins, R., Al-Hindi, K. F., & Moss, P. (2014). A collective biography of joy in academic practice. Social and Cultural Geography, 15(7), 834–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/14649365.2014.929729

- Kornhaber, R., Cross, M., Betihavas, V., & Bridgman, H. (2016). The benefits and challenges of academic writing retreats: An integrative review. Higher Education Research and Development, 35(6), 1210–1227. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1144572

- Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

- Maguire, S., Edmondson, S. (2001). Student Evaluation and Assessment of Group Projects. Journal of Geography in Higher Education,25(2), 209–217. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260120067664

- Marshall, S. (2009). Supervising projects and dissertations. In Fry, H., Ketteridge, S. and Marshall, S. (Eds.) Handbook for teaching and learning in higher education (pp.150–165). Routledge.

- Massingham, P., & Herrington, T. (2006). Does attendance matter? An examination of student attitudes, participation, performance and attendance. Journal of University Teaching & Learning Practice, 3 (2), 20–42. https://doi.org/10.53761/1.3.2.3.

- Moore, S., Murphy, M., & Murray, R. (2010). Increasing academic output and supporting equality of career opportunity in universities: Can writers’ retreats play a role? The Journal of Faculty Development, 24(3), 21–30.

- Moore, S. A. (2003). Writers’ retreats for academics: Exploring and increasing the motivation to write. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 27(3), 333–342. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877032000098734

- Mossa, J. (2014). Capstone portfolios and geography student learning outcomes. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 38(4), 571–581. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2014.958659

- Murray, R., & Newton, M. (2009). Writing retreat as structured intervention: Margin or mainstream? Higher Education Research and Development, 28(5), 541–553. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360903154126

- Murray, R. (2014). Writing in social spaces: A social processes approach to academic writing. Routledge: Taylor and Francis Group.

- Nair, C. S., Adams, P., & Mertova, P. (2008). Student engagement: The key to improving survey response rates. Quality in Higher Education, 14(3), 225–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/13538320802507505

- Nicholson, D. T., Harrison, M. E., & Whalley, W. B. (2010). Assessment criteria and standards of the Geography Dissertation in the UK. Planet, 23(1), 18–24. https://doi.org/10.11120/plan.2010.00230018

- Parsons, T., & Knight, P. G. (2015). How to do your dissertation in geography and related disciplines. How to do your dissertation in geography and related disciplines. Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315849218

- Pathirage, C., Haigh, R., Amaratunga, D., & Baldry, D. (2007). Enhancing the quality and consistency of undergraduate dissertation assessment: A case study. Quality Assurance in Education, 15(3), 271–286. https://doi.org/10.1108/09684880710773165

- Pepper, D., Webster, F., & Jenkins, A. (2001). Benchmaking in Geography: Some implications for assessing dissertations in the undergraduate curriculum. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 25(1), 23–35. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098260125099

- Peters, K. (2017). Your Human Geography Dissertation: Designing, Doing, Delivering. SAGE Publications.

- Petrova, P., & Coughlin, A. (2012). Using structured writing retreats to support novice researchers. International Journal for Researcher Development, 3(1), 79–88. https://doi.org/10.1108/17597511211278661

- Porter, S. R., Whitcomb, M. E., & Weitzer, W. H. (2004). Multiple surveys of students and survey fatigue. In S. R. Porter (Ed.), Overcoming survey research problems (pp. 63–73). Wiley. https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.101

- RGS. (2017). Geography programme accreditation handbook. https://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvhhhght.4

- Rosser, B. R. S., Rugg, D. L., & Ross, M. W. (2001). HEALTH PROMOTION PRACTICE/career development increasing research and evaluation productivity: Tips for successful writing retreats. Health Promotion Practice, 2(1), 9–13. https://doi.org/10.1177/152483990100200103

- Shadforth, T., & Harvey, B. (2004). The undergraduate dissertation: Subject-centred or student-centred? Electronic Journal of Business Research Methods, 2(2), 145–152. http://www.ejbrm.com/issue/download.html?idArticle=143

- Sharp, L., & Frankel, J. (1983). Respondent burden: A test of some common assumptions. Public Opinion Quarterly, 47(1), 36–53. https://doi.org/10.1086/268765

- Silvia, P. (2007). How to write a lot: A practical guide to productive academic writing. American Psychological Association.

- Slinger-Friedman, V., & Patterson, L. M. (2012). Writing in Geography: Student attitudes and assessment. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 36(2), 179–195. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2011.599369

- Solem, M., Cheung, I., & Schlemper, M. B. (2008). Skills in professional geography: An assessment of workforce needs and expectations. Professional Geographer, 60(3), 356–373. https://doi.org/10.1080/00330120802013620

- Speake, J. (2015). Navigating our way through the research-teaching nexus. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 39(1), 131–142. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2014.1002080

- Spronken-Smith, R. (2013). Toward securing a future for geography graduates. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 37(3), 315–326. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2013.794334

- Spronken-Smith, R., McLean, A., Smith, N., Bond, C., Jenkins, M., Marshall, S., & Frielick, S. (2016). A toolkit to implement graduate attributes in geography curricula. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 40(2), 254–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2016.1140129

- Stefani, L. A. J., Clarke, J., & Littlejohn, A. H. (2000). Developing a student-centred approach to re ective learning. Innovations in Education and Training International, 37(2), 163–172. https://doi.org/10.1080/13558000050034529

- Swaggerty, E., Atkinson, T., Faulconer, J., & Griffith, R. (2011). Academic writing retreat: A time for rejuvenated and focused writing. The Journal of Faculty Development, 25(1), 5–11.

- Thomas, K., Wong, K. C., & Li, Y. C. (2014). The capstone experience: Student and academic perspectives. Higher Education Research and Development, 33(3), 580–594. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2013.841646

- Todd, M., Bannister, P., & Clegg, S. (2004). Independent inquiry and the undergraduate dissertation: Perceptions and experiences of final-year social science students. Assessment and Evaluation in Higher Education, 29(3), 335–355. https://doi.org/10.1080/0260293042000188285

- Todd, M. J., Smith, K., & Bannister, P. (2006). Supervising a social science undergraduate dissertation: Staff experiences and perceptions. Teaching in Higher Education, 11(2), 161–173. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562510500527693

- Tremblay-Wragg, É., Mathieu Chartier, S., Labonté-Lemoyne, É., Déri, C., & Gadbois, M. E. (2020). Writing more, better, together: How writing retreats support graduate students through their journey. Journal of Further and Higher Education, 45(1), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/0309877X.2020.1736272

- University of Liverpool. (2016a). Curriculum 2021: A curriculum framework and design model for programme teams at the at the University of Liverpool.

- University of Liverpool. (2016b). Our strategy 2026.

- Van Dinther, M., Dochy, F., & Segers, M. (2011, January 1). Factors affecting students’ self-efficacy in higher education. Educational Research Review, 6(2), 95–108. Elsevier. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.edurev.2010.10.003

- Walkington, H., Griffin, A. L., Keys-Mathews, L., Metoyer, S. K., Miller, W. E., Baker, R., & France, D. (2011). Embedding research-based learning early in the undergraduate geography curriculum. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 35(3), 315–330. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2011.563377

- Webster, F., Pepper, D., & Jenkins, A. (2000). Assessing the undergraduate dissertation. Assessment & Evaluation in Higher Education, 25(1), 71–80. https://doi.org/10.1080/02602930050025042

- Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

- Wenger, E., Trayner, B., & de Laat, M. (2011). Promoting and assessing value creation in communities and networks: A conceptual framework (April). Ruud de Moor Centrum, 18 (August), 1–60. http://www.open.ou.nl/rslmlt/Wenger_Trayner_DeLaat_Value_creation.pdf

- Whalley, W. B., Saunders, A., Lewis, R. A., Buenemann, M., & Sutton, P. C. (2011). Curriculum development: Producing geographers for the 21st century. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 35(3), 379–393. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2011.589827

- Wittman, P., Velde, P. B., Carawan, L., Pokorny, M., & Knight, S. (2008). A writer’s retreat as a facilitator for transformative learning. Journal of Transformative Education, 6(3), 201–211. https://doi.org/10.1177/1541344608323234

- Zimmerman, B. (2000). Attaining self-regulation: A social cognitive perspective. In M. Boekaerts, P. Pintrich, & M. Zeidner (Eds.), Handbook of self-regulation (pp. 13–35). Academic Press.