ABSTRACT

Comparison is an important geographic method and a common task in geography education. Mastering comparison is a complex competency and written comparisons are challenging tasks both for students and assessors. As yet, however, there is no set test for evaluating comparison competency nor tool for enhancing it. Moreover, little is known about university students’ and prospective teachers’ comparison performances and writing strategies for comparison texts. Therefore, in this study, we present an assessment tool aiming to evaluate comparison competency and assess comparison text structures. This tool can also be used as a possible scaffold to teach comparison competency. In order to evaluate the reliability and validity of the assessment tool, we tested it on a sample of 17 future geography teachers from a German university. Results showed that students possessed low levels of comparison competency, although they performed better in content-related aspects. Students utilized only a few of the available comparative text structures. Finally, results from the two parts of the assessment were positively correlated, linking comparison competency to the quality of the text structure. This shows that higher education geography programs should include content on comparison text structures when teaching comparison competency to help future teachers develop this skill.

Introduction

Comparison is a fundamental cognitive activity (Goldstone et al., Citation2010, p. 103) that allows abstract rules to be extracted from concrete examples (Gentner & Markman, Citation1997, p. 45; Gick & Holyoak, Citation1983, p. 31) and helps classify and organize knowledge (Namy & Gentner, Citation2002, p. 12). Comparison is also a central scientific method (Piovani & Krawczyk, Citation2017, p. 822) that is widely used and discussed in geography (e.g. Robinson, Citation2006, Citation2011). In geography education, comparison is also common: comparison tasks represent a substantial proportion (9.18%) of geography textbook tasks in secondary education (Simon et al., Citation2020, p. 6). Therefore, it is an important competency for students to master (Simon & Budke, Citation2020, p. 2).

Although students at all levels often carry out comparisons in geography classes, there is no research to date on the comparison competencies of students and prospective teachers, nor do we know which strategies they use for comparison in geography classes. We do not yet dispose of a tool to assess comparison competency and writing strategies for texts presenting comparisons. This confirms the need for the development of assessment instruments for geographical literacy, as identified by Lane and Bourke (Citation2019, p. 19). This is a critical issue, not only in the broad context of secondary geography education, but also in the context of higher education and teacher training in the field of geography. Indeed, prospective teachers must master comparison competency in order to be able to teach it. Failing this, they will not be able to identify the needs and strengths of their future students and help them develop this competency themselves. Providing information about students’ comparison competencies to professionals in higher education can help them shape or rethink curricula in order to redress any gaps in students’ professional development.

Therefore, in this study, we present an assessment tool which was tested with 17 bachelor students, prospective teachers from the Institute for Geography Education at the University of Cologne in Germany. The tool was developed as practical application of our competency model for comparison in geography (Simon & Budke, Citation2020) and used to assess students’ comparison skills. The aim was to identify the students’ strengths and weaknesses when making comparisons, in order to be able to address challenges in the teacher training program on this basis. The skills were tested through a task consisting of an open question instructing students to compare different migration accounts. Students had to answer in written form, for example via an essay.

Our research questions were:

How can the comparison competencies of geography students be validly assessed on the basis of the comparison competency model (Simon & Budke, Citation2020)?

How competent are geography students when asked to write an essay to solve a comparison task?

How are the writing strategies they use related to their comparison competency?

This article begins with the theoretical background for the development of the test (2. Theoretical background). This is followed by a description of the methods we used in the development of our assessment tool and how it was tested in relation to prospective students’ competency (3. Methods). The results section presents the test results and identifies the strategies used by students to solve the task (4. Results). Then, we discuss the implications of the test for the development of further educational concepts and educational tools to enhance comparison competency (5. Discussion).

Theoretical background

Theoretical, empirical and educational debates about comparison and comparison competency

Comparison is a common geographical research strategy and an important competency, which is transmitted in geography classes in secondary education (Simon & Budke, Citation2020), and which higher education geography students involved in their initial teacher education should be able to teach and to assess. However, different theoretical, empirical and educational problems arise while considering this objective.

First, comparison is one of the established (Krehl & Weck, Citation2020, 1860) but also often discussed research methods in the humanities and social sciences. Traditionally, scientists use comparisons to be able to formulate generalities from particular cases (Durkheim, Citation1967); Lijphart, Citation1971, p. 682; Przeworski and Teune, Citation1970, p. 5; Weber, Citation1921). Geographers too compare urban or regional spaces realizing variable-oriented comparisons in a theory-oriented approach (Cox & Evenhuis, Citation2020, p. 425; Krehl & Weck, Citation2020, 1860). Some of these approaches have been strongly debated in the last twenty years. For example, scholars questioned the legitimacy of the generalization of Eurocentric concepts used to compare cities across different continents (eg. Robinson, Citation2006; Roy, Citation2009). Recent approaches call for using comparison as a tool for identifying common processes between examples whose specificity is irreducible (Robinson, Citation2022). To be able as future teachers to didactically reconstruct the comparison method, university geography students have to understand the implications and stakes of these recent theoretical debates.

Secondly, empirically, the comparison methodology itself is also subject to numerous debates. There are “not so much” comparative works (Kantor & Savitch, Citation2005, p. 135), no systematic implementation of comparison (Kantor & Savitch, Citation2005, p. 136), and what defines a “good” comparison study is not always clear (Krehl & Weck, Citation2020, 1860). For example, selecting comparison elements (comparison units and variables) has implications for the results and reflection is very much needed along the whole comparison process. Scholars from urban studies recently explored different comparative methodologies, trying to “reformat” comparison methodologies (eg. Robinson, Citation2022). Krehl and Weck (Citation2020, pp. 1867–1871) also proposed five questions that they believe should systematically underpin case study research such as to identify underlying theories and concepts (1), to reflect on the ambition to generalize (2), on the selection of cases (3), on comparison objectives (4) and on the trade-offs realized during the process (5). But, the comparison methodology remains scarcely studied which can lead to difficulties while didactically reconstructing it with students.

Thirdly, these important theoretical and empirical debates from the fields of human geography and urban studies are not to be found in current research in geography education. Comparison studied as a task and as a competency in geography education is still a young research field. Only did Wilcke and Budke (Citation2019) propose a systematic comparison method as a tool to be used in secondary education. In their model, first, students have to identify a specific question to be resolved via the comparison. Second, they have to choose comparison units (i.e. objects to be compared) and variables to compare them (i.e. aspects or criteria through which objects are compared). Then, they juxtapose comparison units and identify similarities and differences in order to provide an answer to the initial problem. They analyse this result by weighting variables, deriving explanations and/or inferring general rules. While comparing, each step of the comparison process should ideally be justified and reflected (Wilcke & Budke, Citation2019, p. 7).

University students may not be newcomers to comparison processes since comparison is part of geography curricula in secondary education, either through case studies used to infer general rules on larger scales (e.g. in France: Ministère de l’Education Nationale, Citation2019, p. 3) or as a particular task aimed at applying acquired knowledge to new situations (e.g. in Germany: Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geographie, Citation2017, p. 32). It is therefore an important school competency in secondary education (Simon & Budke, Citation2020). But, few tasks in English, German and French textbooks enhance the development of comparison competency, since they rarely allow students to autonomously select and justify the variables, units, material or questions relating to the comparison (Simon & Budke, Citation2020). Many comparison tasks concentrate on simple objectives, rarely requiring higher-order thinking (Simon et al., Citation2020). Therefore, although they might be familiar with comparison tasks, little is known of how secondary or university students are effectively competent when they compare. Moreover, there is no existing scaffolding tool to teach comparison competency while adapting to the level of students and to help them develop this skill.

Development of a tool to assess and foster comparison competency in geography education

To be able to develop and adapt university programs and initial teacher education related to the comparison method, evaluation of students’ comparison competency at the beginning of their higher education programs is needed. However, there is no valid or reliable assessment for comparison competency. As pointed by Lane and Bourke (Citation2019, p. 11), assessment in geography needs more validated instruments to evaluate students’ competencies. Such an assessment instrument for comparison competency is not only needed for competency evaluation: it can also be used formatively as a scaffold to foster competency development while adapting to each student. Scaffolding (Wood et al., Citation1976, p. 90) involves the provision of tools by a teacher to enable a student to acquire new skills or knowledge in their “zone of proximal development” (Vygotsky, Citation1978, p. 37). These tools are a support allowing students to gradually move out of their current learning zones into other zones that are less comfortable but still close to them. Adapted to each student, scaffolding tools are only temporary and teachers progressively remove them once students become more competent (Van der Stuyf, Citation2002, p. 11). Therefore, this article takes the competency model for comparison proposed by Simon and Budke (Citation2020, see ) as the theoretical basis to develop an assessment instrument which can also be used as a scaffold.

Table 1. Competency model for comparison in geography education (Simon & Budke, Citation2020, p. 5).

In this model, comparison competency is composed of four dimensions: two related to the comparison process, and two related to comparison content and objectives. Each dimension is divided in competency levels, from the lowest (level 1) to the highest level (level 4). The higher the competency, the higher the level obtained. The first dimension (planning and implementation of comparison processes, see ) allows us to ascertain if students are able to autonomously select the elements of the comparison (question, comparison units, variables, material). The second dimension (reflection and argumentative justification of comparative processes, see ) assesses students’ ability to justify their chosen comparison processes, from explaining comparison results to justifying the choice of comparison elements. The third dimension (interrelation of geographical information, see ), relates to students’ ability to manage complex comparison content, for example, the ability to deal with more than two comparison units, or to weight variables. Finally, the fourth dimension (achievement of comparison objectives, see ) relates to students’ progressive ability to understand higher-order content, such as inferring rules or identifying exemplary singularities. Although this competency model was developed for secondary education, it can be used as a basis to assess university students’ own competency at the beginning of their initial teacher education.

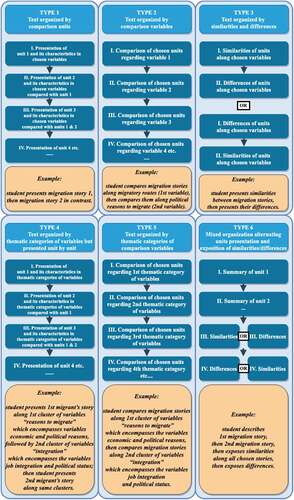

Assessing students on their comparison competency also involves evaluating written texts that use comparison. How students structure their written comparisons has been studied in discourse analysis, literacy research and language teaching. Comparison writing tasks are difficult, as the structure of the written text must lend itself to the comparative process (Englert & Hiebert, Citation1984; Spivey, Citation1991). Writing a comparison based on texts requires not only reading and selecting the information from the different texts, but also being able to reorganize it in order to carry out a comparison (Hammann & Stevens, Citation2003, p. 745). When provided with a comparison task, students may use one of five different organisational patterns to structure their essay (Spivey, Citation1991, p. 403). These patterns reflect comparison processes and structures. Students may organize the text according to comparison units (“Object format”, Spivey, Citation1991, p. 394), or present their results based on the variables they used (“Aspect format”, Spivey, Citation1991, p. 394). They can also group the results into differences and similarities (“Aspect format with Similarity-Difference Grouping”, Spivey, Citation1991, p. 397). The last two patterns are based on grouping variables or “Macro-Aspects” in order to organize results by object or by aspect (“Aspect format with Macro-Aspects” or “Object Format with Macro-Aspects”, Spivey, Citation1991, p. 397). In her study with university students, Spivey found that the “Macro-Aspect format” was the most efficient for presenting comparisons (Citation1991, p. 409).

However, there is no research on how students make comparisons in geography education and which strategies they use to structure their results. We do not know how comparison competency relates to the strategies and text structures adopted by students when writing geographical comparisons. This study seeks therefore to conduct an exploratory analysis of how university students structure their answers when provided with a comparative task in geography education and attempts to correlate texts structures with comparison competency. The test of our assessment tool can thus help to identify the best writing strategies for the development of the comparison competency and thus validate or refine the tool as a possible scaffold for the enhancement of this competency.

Methods

Test task creation

Since comparison competency implies performance in all four dimensions of the competency model (Simon & Budke, Citation2020, p. 5, see ) while requiring higher-order thinking and argumentation, designing a test to assess it is crucial. Any evaluation tool must be able to assess each of the different dimensions in order to provide a complete picture of students’ competency. It also must be based on a task that gives students the possibility to perform a complex comparison.

Since many textbook tasks are closed, reproductive and oriented towards content (Simon et al., Citation2020), they often fail to enhance comparison competency (Simon & Budke, Citation2020). For this reason, we designed an original task. We chose an open formulation of the task which allowed for diversity in possible answers and therefore diversity in levels of comparison competency.

We chose migration, a typical geographical topic, as the general subject of the comparison for our test of the assessment tool. Five different authentic migrant testimonies (respectively consisting of 213, 342, 434, 275 and 408 words) were collected and added to the test as possible material for the students to use. Recurring themes and possible comparison variables were: reasons to migrate, integration and mobility patterns. As the testimonies were provided to the students as is (although two texts were shortened to stay in proportion with other examples), the texts were not symmetrical in their structure, requiring students to select and analyse the different elements in order to be able to organize their comparison.

The task is presented as: “Perform a comparison of migration stories, based on your personal knowledge and/or one or more of the following texts.”

Students had one A4 page to provide an answer. It was expected that the answer would be given in essay form, since this format is helpful for assessing students’ skills in argumentation (Budke et al., Citation2010, p. 66; Paniagua et al., Citation2019, p. 111). Moreover, essays are a good means of capturing students’ reasoning, since comparison is a complex process requiring different steps and reflection (Wilcke & Budke, Citation2019) and the comparison results can be structured in various ways (Spivey, Citation1991, p. 403).

Test implementation and sample

To test the assessment tool, we recruited bachelor students from a university seminar at the Institute for Geography Education, University of Cologne, Germany. Seventeen students enrolled in geography teacher training courses participated, taking the test during a one-hour online class in April 2021. No prior information had been given on the purpose of the test. Of these students (3 male, 13 female, 1 undisclosed), 6 were in their first semester, 8 in their second semester, 2 in the third semester and only one student was in ninth semester: we were thus able to evaluate comparison competency chiefly at the beginning of their geographical and didactical training. Tests were anonymized for analysis.

Comparison texts’ assessment tool development

In order to evaluate the essays written by the group of prospective teachers, we built a tool consisting of two parts. In the first part we took into account every dimension of the comparison competency model (Simon & Budke, Citation2020, p. 5, see ). Each dimension was reduced to smaller evaluation items that were graded 0 if absent and 1 if present in the students’ essays. After a first round of grading with these items, we noted that students had chosen elements of the comparison process without explicitly stating their choice. Also, some students mentioned comparison elements without drawing any conclusions from the comparison. Therefore, new coding rules were formulated by the judges and new grading items were added. We added items aimed at measuring whether or not the comparison was effectively carried out, and if a conclusion was drawn. We differentiated between explicit and implicit selection of comparison elements. We also added items evaluating the pertinence of argumentation to better evaluate performance on the second dimension (reflection and argumentative justification of comparison processes, see ). Finally, items in the fourth dimension (achievement of comparison objectives, see ), which are noncumulative, were coded 0, 1, 2, 3 or 4 to better capture the increase in competency.

presents all obtained items from the first part of the assessment tool at the end of the development. In this first part, students could obtain a maximum of 28 points.

Table 2. Comparison text assessment tool (part 1): list of categories to measure comparison competency in relation to the dimensions of comparative competency (Simon & Budke, Citation2020, p. 5, see ). Own elaboration.

The second part of our assessment tool (see ) was built to assess students’ strategies for structuring their texts since this has been related to higher text quality (Kellogg, Citation1987). The first author carried out a categorization through an inductive analysis of the structuring elements observed in texts, which was then confirmed by a group of other scientists. As there is currently no common scientific method for assessing comparison texts (Hammann & Stevens, Citation2003, p. 741), we also used elements from Spivey (Citation1991, pp. 394–397), Englert and Hiebert (Citation1984, p. 65) and scoring scales from Hammann and Stevens (Citation2003, pp. 755–756), applied deductively to the written answers. With this scale, comparison texts could reach a maximum of 9 points.

Table 3. Comparison text assessment tool (part 2): list of categories to assess comparison text structures. Own elaboration.

The first categories (“General form of the answer”, see ) analysed this first criterion. Secondly, we assessed the use of basic structural elements, in the essay, such as introduction, body and conclusion (“Organization of the text”, see ). These elements were considered necessary in order to allow readers to understand the essays. In this section we also checked for structuring cue words specific to comparison text structures (Englert & Hiebert, Citation1984, p. 65).

While assessing structuring elements we also explored the variety of structures in comparison texts qualitatively. Six possible text structures for comparisons were identified. Five types were deductively identified based on Spivey’s analyses (Citation1991, p. 397) and one mixed type present in our corpus was inductively constituted as a category (see ). These text structures were analysed in an explorative way to analyse which types were used in our corpus and if a certain type of text structure tended to perform better than other types.

Table 4. Categories for the explorative analysis of comparison structures. Own elaboration.

Validity and reliability of the assessment tool

The final stage of the development of our assessment tool was to test its validity and reliability.

Validity ensures that the assessment tool really assesses the investigated concepts. Here we examined face and construct validity (Oluwatayo, Citation2012; Roid, Citation2006). Face validity was achieved because our test used a geographical subject prone to comparison analysis, that is, migration, and offered an open task allowing a wide range of possible responses. We also ensured construct validity as we developed the first part of the assessment tool on a pretested and theoretically founded comparison competency model (Simon & Budke, Citation2020, p. 5), and the second part was based on already available scales (Englert & Hiebert, Citation1984, p. 65; Hammann & Stevens, Citation2003, pp. 755–756; Spivey, Citation1991, pp. 394–397).

Reliability means both the test and assessment can be replicated. Here we ensured the reliability of the first part by having two judges grade all tests three times, each time separated by periods of two weeks, while honing the description of the categories to ensure homogenous grading. A final grading was carried out after three months. We calculated intercoder reliability on 100% of tests and obtained a final Kappa coefficient of .72, which is considered good or substantial (Landis & Koch, Citation1977, p. 165). All remaining rating differences were discussed among the two judges and a common agreement was reached. The second part of the tool was tested for reliability on 100% of tests via an intracoder analysis after two rounds of grading separated by three weeks. We obtained a Kappa coefficient of .922, which is considered as perfect (Landis & Koch, Citation1977, p. 165).

Quantitative analysis of test results through descriptive statistics and correlations

After grading all texts, we carried out different descriptive analyses to see how competent students were at comparing, using Part 1 of our assessment (see ). Each student’s performance could be assigned to different levels within our competency model. Other descriptive statistics were performed on the results from Part 2 (see ) and on the different types of text structures found in our corpus. Finally, we calculated correlations between the two parts (see ) to identify the relationship between comparison competency and the quality of comparison text structures.

Results

Overall results in comparison competency (part 1)

First, during the grading of tests students obtained results of between 7 and 14 points out of a total maximum of 28 points in Part 1 of the test. The distribution of test results showed a concentration of grades in low levels of comparison competency with a mean of 10.76 points and a median of 10 points (see ). All respondents performed a comparison (item 1). 16 students wrote essays which included a result (item 16). One student provided only a table. Only four students attained half of the possible total points (28). No correlation was found between scores and gender; nor between scores and the number of completed semesters studying geography at university.

Results in the four dimensions of comparison competency

To better understand the overall low results in comparison competency, students’ essays were classified into the different dimensions of the competency model (Simon & Budke, Citation2020, p. 5, see ). Results are presented in .

Figure 2. Students’ results in the four dimensions of comparison competency. The higher the level, the higher the comparison competency. Own elaboration.

Results in the first dimension of comparison competency (Planning and implementation of comparison processes, see ) showed a substantial level in this dimension since 70.59% of students (12 out of 17) achieved level 3. As we used a very open question to test their autonomy, students were not guided in the choice of different elements of comparison and did autonomously choose comparison units, comparison variables and material. However, many did not explicitly explain the choice of these elements in the comparison process. No student chose a question to solve. Even if 88.23% of students (15 out of 17) did explicitly mention the comparison units, only 11.76% (2 students out of 17) mentioned explicitly the comparison variables they used for their comparison. Therefore, examples reflecting on comparison variables such as the following, were rare: “One can compare [the stories] in very different ways. For example, you [can] first look at the motive of the people (…). You can look at their flight and their prospects on the country they now live in (…). You can also look at their experiences in the country of origin (…) and whether they want to go back” (Extract from Student n°9. Translated from German. Emphasis added).

Results in the second dimension of comparison competency (Reflection and argumentative justification of comparison processes, see ) showed very little use of argumentation to support the comparison process, with only 17.65% of students (3 out of 17) attaining level 1 in this dimension while using argumentation to justify their results. Students did not provide arguments to justify their choice of comparison elements. Few students cited source texts while performing their comparison, with only one referring explicitly to precise lines to prove their conclusions.

In dimension 3 of comparative competency (Acknowledgement and analysis of interrelations in geographical information, see ), results showed a moderate competency: 94.12% (16 students out of 17) obtained level 2 while using more than one variable to analyse two units or more. But, these results also confirmed that students did not reflect on the different variables and their respective weight (level 3) to explain their results. They did not reflect on the concepts via the weighting of variables (level 4). This shows that their choice of variables was arbitrary and not guided by any question to solve.

Finally, results showed that students performed better in the fourth dimension of comparison competency (Achievement of comparison objectives, see ). Although one student did not reach any level, competency was more distributed in this dimension: 58.82% (10 out of 17 students) obtained level 1, by using comparison to simply state similarities or differences. One student (5.88%) obtained level 2 and used comparison to show a process or test a rule. 29.42% (5 students out of 17) attained level 4 and performed complex comparisons, identifying specificities or building rules in an inductive way. For example, a student wrote: “One can conclude that [migrants’] plans sometimes (have to) change: migration stories are sometimes not linear” (Extract from Student n°6. Translated from German. Emphasis added).

Results in comparison text structures’ assessment (part 2)

Students’ performance in the comparison text structure analysis (Part 2) is presented in .

Results were grouped around a mean of 7.71 and a median of 8 out of a maximum of 9 points. One of the respondent’s written answers was awarded only one point, since it was given in form of a table juxtaposing variables and units without drawing any conclusion from the comparison nor providing any explanation (item 1, see ). No text obtained less than half of all possible points. All written texts obtained good results since they were all structured, with 81.2% of texts (13 out of 16 texts) including an introduction, 75% of texts (12 texts) being clearly organized, and 10 texts (62.5%) including a conclusion (items 2–6, see ).

Results in the use of comparison text types

To analyse the text structures, six categories were constituted (see Methods): five were deductively constituted from the literature review (Spivey, Citation1991) and another one constituted as an inductive category in our corpus (see and ).

Figure 4. Types of comparison text structures (inductive-deductive categorization using observed texts and Spivey (Citation1991)). Own elaboration.

Out of the six identified text structures (see and ), students used only three different strategies to write their comparison. The most common strategy was Type 1 (“Text organized through comparison units”, see ) with 7 out of 16 texts (43.75%) using this structure. These texts used cue words to compare and contrast the source material. For example, after presenting the first migrant’s story in a paragraph, a student began the following paragraph thus: “In contrast to this story [from a refugee], the woman did not have to flee because she want[ed] to leave the country voluntarily. Her circumstances [we]re not as tragic and urgent as in [the first story]” (Extract from Student n°17. Translated from German. Emphasis added).

The second most used strategy, adopted in 31.25% of texts (5 students out of 16 using a text), was variable oriented (Type 2, “Text organized through comparison variables”, see ). Finally, 4 students out of 16 (25% of texts) chose a mixed organization for their texts (Type 6, “Mixed organization alternating presenting units and explaining similarities/differences”, see ). No student chose to group variables into clusters (Types 4 “Text organized by thematic categories of variables but presented unit by unit” and 5 “Text organized by thematic categories of variables”, see ) and no text was organized solely around similarities/differences (Type 3, “Text organized by similarities and differences”, see ).

Correlations between strategies and performance

We calculated a correlation between scores from the two parts of the assessment tool (Part 1: comparison competency assessment and Part 2: comparison text structure assessment, see ) to evaluate to what extent structuring strategies could correlate to different levels in comparison competency. Total results in each part of the assessment were found to be moderately positively correlated, r (15) = .533, p = .02. The better structured the comparison was, the more competent students were while comparing. This positive relationship between both parts of the assessment may mean that the use of structured answers reflects better competency, but could also indicate that using structured answers allowed respondents to develop better comparison competency. Thus, we can not only suppose that a lack of comparison competency can lead to difficulties in structuring answers, but also, that problems with strategy and structure during a written task indicate difficulties mastering comparison processes.

We also looked at the mean results of the first assessment tool (see ) in relation to the different text structure strategies (see ). Results showed that best scores were obtained by students adopting a Type 1 structure (“Text organized through comparison units”, see ) with a mean of 10.28 points whereas texts structured around variables (Type 2 “Text organized through comparison variables”, see ) obtained a mean of 9.2 points and mixed structures (Type 6, “Mixed organization”, see ) obtained a mean of 8.5 points. Given the small sample size, we could not test the significance of these differences; but it seems that the choice of a clear writing strategy rather than a mixed organization (Types 1 or 2 against Type 6, see ) could have an influence on comparison performance.

Discussion

Comparison is an important competency in geography and a common task which is often performed by students throughout their geography education in secondary school and at universities. In this study we aimed to develop an assessment tool evaluating comparison competency and comparison text structures, to explore students’ comparison competencies and to relate them to their writing strategies. Our aim was also that the assessment instrument could be used as a scaffold to develop comparison competency.

First, we developed a valid and reliable assessment tool. Not only was the validity of the comparison competency assessment confirmed, since it was built on a previously validated comparison competency model, but our results also agreed with those of previous research (Simon & Budke, Citation2020; Simon et al., Citation2020), notably regarding students’ poor performances regarding argumentation (Budke & Kuckuck, Citation2017, p. 101; Budke et al., Citation2010, p. 68; Uhlenwinkel, Citation2015, p. 56). Therefore, this assessment tool can assess students’ comparison competency and writing strategies in comparison texts. It can be used in future research and by university programs to assess students’ comparison competency.

Secondly, we wanted to identify difficulties students face in comparison tasks and where they lack competency. Our results indicated that the prospective geography teachers from our sample showed only low levels of comparison competency. This aligns with our research analysing textbooks, which showed that textbook comparison tasks do not enhance the development of comparison competencies (Simon & Budke, Citation2020; Simon et al., Citation2020). Without meaningful textbook comparison tasks to train their comparison skills during their secondary education, our geography students tended to achieve only low levels of comparison competency. Many of them were still in the first semesters of their studies, so the influence of secondary teaching was presumably still predominant in their answers. Results from the classification of students in the first dimension of comparison competency (Planning and implementation of comparison processes, see and ) showed that many students did not explicitly select comparison elements such as units or variables. Although the open task design allowed them to autonomously select different comparison elements, they did not master the comparison method and did not perform this task consciously or reflect on their selection. This shows that designing open tasks is necessary to enhance autonomy in the comparative process, but also that the comparison process and identification of comparison elements need to be learnt and practiced to ensure students master this dimension. Results were also poor in the second and third dimensions of comparative competency (Reflection and argumentative justification of comparison processes and Acknowledgement and analysis of interrelations in geographical information, see and ). Not being familiar with the comparison method and accustomed to very closed tasks, as our textbook analysis shows (Simon & Budke, Citation2020; Simon et al., Citation2020), students did not associate comparison with argumentation and did not reflect on the comparison process. These poor results in the second dimension relative to argumentation are in line with the results of previous studies where students’ argumentation skills were found to be very low (Budke & Kuckuck, Citation2017, p. 101; Budke et al., Citation2010, p. 68; Uhlenwinkel, Citation2015, p. 55), moreover in classroom environments where argumentation is not frequent (Driver et al., Citation2000, p. 308; Kuhn & Crowell, Citation2011, p. 551). However, students’ results were better in dimension 4 (Achievement of comparison objectives, see and ). This is again in accordance with our initial analysis of textbook tasks which showed that textbook tasks performed better in the fourth dimension of comparison competency (Simon & Budke, Citation2020; Simon et al., Citation2020). Students’ improved performances in the fourth dimension may be due to the fact that they learned how to formulate rules via comparison processes during secondary education. They were presumably trained in this dimension of comparison competency.

As a consequence, a combination of open tasks and tools that help elucidate comparison process, such as comparison matrices and detailed instructions (e.g. Englert et al., Citation1991), can be of use in fostering comparison competency in students. It is also necessary to make students aware of the different steps and requirements of the comparison method: although comparing is a fundamental cognitive activity (Goldstone et al., Citation2010, p. 103), it is not an easy task to perform. Therefore, teaching a conscious approach to comparison processes seems necessary to enhance comparison competency in geography students and prospective teachers. It is also necessary for students to understand why argumentation is necessary to comparison processes and why it can help develop comparison competency and therefore scientific geographical literacy, since argumentation skills are related to scientific reasoning (e.g. Kuhn, Citation1992, p. 144; Zohar & Nemet, Citation2002, p. 58). The assessment tool presented in this study can itself be used as such a scaffold to teach students how to perform comparison processes and reflect them argumentatively.

Thirdly, our study explored how students structured their comparison texts and aimed to investigate how writing strategies were related to comparison competency. Only 3 different text structures were used by our students: Types 1 (Text organized by comparison units), 2 (Text organized by comparison variables), and 6 (Mixed organization alternating presenting units and similarities/differences, see ). This is an interesting finding, since there is no common accepted method of structuring written comparisons in geography and a variety of structures were expected (see ). Although Spivey (Citation1991) identified the “Macro-Aspect Structure” (Type 5 in our assessment, see ) as the best structure for comparison, it was not used by our students. In their study, Kirkpatrick and Klein (Citation2009, p. 318) also found that students rarely organized their texts according to specific comparison elements, such as variables or similarities and differences. Students in their study and in a study by Englert et al. (Citation1988, p. 44) also structured their texts according to units (Type 1). However, as students were not trained to structure their texts in a particular way beforehand, we can suppose that they chose presentation by units as the most convenient structure. Presenting the comparison unit by unit was certainly the easiest strategy for students, since they simply had to follow the order of units as they appeared in the source materials and did not need to develop a plan in order to write their text. However, it may not be the most efficient way to structure comparisons.

The Type 6 writing strategy (Mixed organization alternating presenting units and similarities/differences, see ) is a common strategy used in German secondary education (e.g. Becker-Mrotzek et al., Citation2015). In the AbiturFootnote1 examination, different subjects such as Geography or German are assessed through so-called “material-based writing”, in which students are supposed to write their own text based on various documents such as maps, statistical tables and texts. The answer is thus often broken down into a first section summarizing the documents, then a second section discussing the relationships between them. The Type 6 text structure identified in our corpus is an example of this structure applied to geography education (Budke et al., Citation2021, p. 156). The fact that students used this mixed structure in their answers demonstrates that they used secondary education strategies to solve the task. This strategy to structure comparison may be singular to German students. However, this shows the necessity to consider local specificities or practices in the evaluation of comparison texts.

The results of the comparison competency assessment and the comparison text structure assessment were positively correlated. Either structured texts showed better comparison competency, or a better comparison competency implied better text structuring skills. This can be explained by the fact that writing a comparison implies specific text structures pertinent to the peculiarities of comparison: students need to be aware of comparison’s fundamental structures such as comparison units, variables, similarities and differences, as Hammann and Stevens (Citation2003, p. 733) also showed. This is also in line with findings from Englert et al. (Citation1988, p. 42) which correlated students’ writing performance with students’ understanding of the utility of writing strategies.

Students using Types 1 and 2 as comparison text structures did better than students using the Type 6 mixed organization. Using the Type 6 structure may have led students to forget about comparison structuring elements such as variables, which were necessary for better performance. We can also suppose that students using the variable structure (Type 2) were more challenged by this text organization (Spivey, Citation1991) and therefore performed worse than students juxtaposing and alternating units (Type 1) which appeared to be easier for them (Englert et al., Citation1988, p. 44; Kirkpatrick & Klein, Citation2009, p. 318). Type 2 texts organized around variables are more difficult to write since they imply careful preparation and combining elements from different sources in a non-linear reading. There is, therefore, a need for didactic tools to teach specific comparison text structures around variables or clusters of variables (Types 2, 4 and 5) in geography education. University programs aiming to better train comparison competency need to include reflection on comparison text structures and writing tools as a means to enhance this competency.

Our assessment tool to measure comparison competency is not only a measurement tool: it is also a potential useful scaffold to teach comparison. Gibbons has identified different steps for scaffolding: first, scaffolding means evaluating the “demands of the particular subject content” and second, the “learning needs of the learners” (Gibbons, Citation2002, p. 218), before educators design specific and appropriate material to help learners (third step). Here educators can use the assessment tool to diagnose comparison competency and measure each student’s “zone of proximal development” (Vygotsky, Citation1978, p. 37). Then, depending on the students’ initial competency, the assessment tool can be didactically adapted to allow them achieve progressively greater competency while selecting needed items to be trained by students. When full competency is achieved, students shall be able to compare autonomously without needing the tool. It is also possible to introduce the tool so that students use it as they need it or adapt it as their own scaffold (Holton & Clarke, Citation2006, p. 136) to gain agency in their own learning processes.

Conclusion

Teaching fundamental geographical methods such as comparison in higher education implies the ability to assess students’ competency. It is also necessary to reflect on possible tools to be provided to prospective teachers who will have to teach this competency to secondary education students. In this study, we developed an assessment tool for comparison competency. We found that comparison competency in prospective teachers appears to be underdeveloped. Their lack of autonomy in comparison processes calls for increased focus on teaching geographical comparison in higher education. The comparison process should be explicitly taught so that students can compare consciously and explicitly in order to better develop their skills. Using the assessment tool presented in this study as a scaffolding tool is a way to achieve this objective since our tool allows to train comparison competency in small steps and to gain help with comparison text structures. This seems crucial in order to help future geography teachers not only to master an essential geographical method, but also to be able to teach this competency to their own future students.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Prof. Dr. Frank Schäbitz for his support and Michelle Wegener for her help in the overarching project.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1. Abitur: German examination at the end of secondary education.

References

- Becker-Mrotzek, M., Kämper van den Boogart, M., Köster, J., Stanat, P., & Gippner, G. (2015). Bildungsstandards aktuell: Deutsch in der Sekundarstufe II. Braunschweig: Diesterweg.

- Budke, A., Gebele, D., Königs, P., Schwerdtfeger, S., & Zepter, L. A. (2021). Materialgestütztes argumentierendes Schreiben im Geographieunterricht von Schüler*innen mit und ohne besonderem Förderbedarf. In A. Budke & F. Schäbitz (Eds.), Argumentieren und Vergleichen. Beiträge aus der Perspektive verschiedener Fachdidaktiken (Vol. 15, pp. 173–199). LIT.

- Budke, A., & Kuckuck, M. (2017). Argumentation mit Karten. In H. Jahnke, A. Schlottmann, & M. Dickel (Eds.), Räume visualisieren (Vol. 62, pp. 91–102). Münsterscher Verlag für Wissenschaft.

- Budke, A., Schiefele, U., & Uhlenwinkel, A. (2010). ’I think it’s stupid’is no argument: Investigating how students argue in writing. Teaching Geography, 35(2), 66–69..

- Cox, K. R., & Evenhuis, E. (2020). Theorising in urban and regional studies: Negotiating generalisation and particularity. Cambridge Journal of Regions, Economy and Society, 13(3), 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1093/cjres/rsaa036

- de l’Education Nationale, M. (2019, January 22). Programme d’histoire-géographie de seconde générale et technologique: Arrêté du 17-1-2019. Bulletin Officiel de l’Education Nationale Spécial, (1), 16.

- Deutsche Gesellschaft für Geographie. (2017). Bildungsstandards im Fach Geographie für den Mittleren Schulabschluss mit Aufgabenbeispielen. Bonn: Selbstverlag DGfG, 96.

- Driver, R., Newton, P., & Osborne, J. (2000). Establishing the norms of scientific argumentation in classrooms. Science Education, 84(3), 287–312. https://doi.org/10.1002/SICI1098-237X20000584:3287:AID-SCE13.0.CO;2-A

- Durkheim, E. (1967). Les Règles de la méthode sociologique (16th ed.). PUF.

- Englert, C. S., & Hiebert, E. H. (1984). Children’s developing awareness of text structures in expository materials. Journal of Educational Psychology, 76(1), 65–74. https://doi.org/10.1037/0022-0663.76.1.65

- Englert, C. S., Raphael, T. E., Anderson, H. M., & Anthony, L. M. (1991). Making strategies and self-talk visible: Writing instruction in regular and special education classrooms. American Educational Research Journal, 28(2), 337–372. https://doi.org/10.3102/00028312028002337

- Englert, C. S., Raphael, T. E., Fear, K. L., & Anderson, L. M. (1988). Students’ metacognitive knowledge about how to write informational texts. Learning Disability Quarterly, 11(1), 18–46. https://doi.org/10.2307/1511035

- Gentner, D., & Markman, A. B. (1997). Structure mapping in analogy and similarity. The American Psychologist, 52(1), 45–56. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.52.1.45

- Gibbons, P. (2002). Scaffolding language, scaffolding learning: teaching second language learners in the mainstream classroom. Heinemann.

- Gick, M. L., & Holyoak, K. J. (1983). Schema induction and analogical transfer. Cognitive Psychology, 15(1), 1–38. https://doi.org/10.1016/0010-0285(83)90002-6

- Goldstone, R. L., Day, S., & Son, J. Y. (2010). Comparison. In B. Glatzeder, V. Goel, & A. Müller (Eds.), Towards a theory of thinking: Building blocks for a conceptual framework (pp. 103–121). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-642-03129-8_7

- Hammann, L. A., & Stevens, R. J. (2003). Instructional approaches to improving students’ writing of compare-contrast essays: An experimental study. Journal of Literacy Research, 35(2), 731–756. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15548430jlr3502_3

- Holton, D., & Clarke, D. (2006). Scaffolding and metacognition. International Journal of Mathematical Education in Science and Technology, 37(2), 127–143. https://doi.org/10.1080/00207390500285818

- Kantor, P., & Savitch, H. V. (2005). How to study comparative urban development politics: A research note. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 29(1), 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2005.00575.x

- Kellogg, R. T. (1987). Writing performance: Effects of cognitive strategies. Written Communication, 4(3), 269–298. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088387004003003

- Kirkpatrick, L. C., & Klein, P. D. (2009). Planning text structure as a way to improve students’ writing from sources in the compare–contrast genre. Learning and Instruction, 19(4), 309–321. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.learninstruc.2008.06.001

- Krehl, A., & Weck, S. (2020). Doing comparative case study research in urban and regional studies: What can be learnt from practice? European Planning Studies, 28(9), 1858–1876. https://doi.org/10.1080/09654313.2019.1699909

- Kuhn, D. (1992). Thinking as argument. Harvard Educational Review, 62(2), 155–178. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.62.2.9r424r0113t670l1

- Kuhn, D., & Crowell, A. (2011). Dialogic argumentation as a vehicle for developing young adolescents’ thinking. Psychological science, 22(4), 545–552. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611402512

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. https://doi.org/10.2307/2529310

- Lane, R., & Bourke, T. (2019). Assessment in geography education: A systematic review. International Research in Geographical and Environmental Education, 28(1), 22–36. https://doi.org/10.1080/10382046.2017.1385348

- Lijphart, A. (1971). Comparative Politics and the Comparative Method. The American Political Science Review, 65(3), 682–693. https://doi.org/10.2307/1955513

- Namy, L. L., & Gentner, D. (2002). Making a silk purse out of two sow’s ears: Young children’s use of comparison in category learning. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 131(1), 5–15. https://doi.org/10.1037/0096-3445.131.1.5

- Oluwatayo, J. A. (2012). Validity and reliability issues in educational research. Journal of Educational and Social Research, 2(2), 391–400.

- Paniagua, M., Swygert, K., & Downing, S. (2019). Written Tests: Writing high-Quality Constructed-Response and Selected-Response Items. In R. Yudlowsky, Y. S. Park, & S. M. Downing (Eds.), Assessment in Health Professions Education (2nd ed., pp. 109–125). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781138054394

- Piovani, J. I., & Krawczyk, N. (2017). Comparative studies: Historical, epistemological and methodological notes. Educação & Realidade, 42(3), 821–840. https://doi.org/10.1590/2175-623667609

- Przeworski, A., & Teune, H. (1970). The Logic of Comparative Social Inquiry. John Wiley and Sons.

- Robinson, J. (2006). Ordinary cities: Between modernity and development. Routledge.

- Robinson, J. (2011). Cities in a world of cities: The comparative gesture. International Journal of Urban and Regional Research, 35(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-2427.2010.00982.x

- Robinson, J. (2022). Introduction: Generating concepts of ‘the urban’ through comparative practice. Urban Studies, 59(8), 1521–1535. https://doi.org/10.1177/00420980221092561

- Roid, G. H. (2006). Designing ability tests. In S. M. Downing & T. M. Haladyna (Eds.), Handbook of test development (2nd ed., pp. 527–542). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Roy, A. (2009). The 21st-Century Metropolis: New Geographies of Theory. Regional studies, 43(6), 819–830. https://doi.org/10.1080/00343400701809665

- Simon, M., & Budke, A. (2020). How geography textbook tasks promote comparison competency—An international analysis. Sustainability, 12(20), 8344. https://doi.org/10.3390/su12208344

- Simon, M., Budke, A., & Schäbitz, F. (2020). The objectives and uses of comparisons in geography textbooks: Results of an international comparative analysis. Heliyon, 6(8), 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.heliyon.2020.e04420

- Spivey, N. N. (1991). The shaping of meaning: Options in writing the comparison. Research in the Teaching of English, 25(4), 390–418.

- Uhlenwinkel, A. (2015). Geographisches Wissen und geographische Argumentation. In A. Budke, M. Kuckuck, M. Meyer, F. Schäbitz, K. Schlüter, & G. Weiss (Eds.), Fachlich argumentieren. Didaktische Forschungen zur Argumentation in den Unterrichtsfächern (Vol. 7, pp. 46–61).

- Van der Stuyf, R. R. (2002). Scaffolding as a teaching strategy. Adolescent Learning and Development, 52(3), 5–18.

- Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between learning and development. In L. S. Vygotsky & M. Cole (Eds.), Mind in society: Development of higher psychological processes (pp. 79–91). Harvard university press.

- Weber, M. (1921). Gesammelte Aufsätze zur Religionssoziologie (Vol. 3). Mohr.

- Wilcke, H., & Budke, A. (2019). Comparison as a method for geography education. Education Sciences, 9(3), 225. https://doi.org/10.3390/educsci9030225

- Wood, D., Bruner, J. S., & Ross, G. (1976). The role of tutoring in problem solving. Journal of Child Psychology, Psychiatry, & Applied Disciplines, 17, 89–100. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.1976.tb00381.x

- Zohar, A., & Nemet, F. (2002). Fostering students’ knowledge and argumentation skills through dilemmas in human genetics. Journal of Research in Science Teaching, 39(1), 35–62. https://doi.org/10.1002/tea.10008