ABSTRACT

Over the past forty years, scholars have been studying students’ choice of higher education programmes to unravel the complexity of the choice process. Recent studies have shown that students may commit to a programme, i.e. they make a choice to enrol in that programme, when they find a programme that attunes well with their interests. Students may nonetheless decide to switch from one programme to another before final enrolment and research has not yet sufficiently explained why they do that. The present study therefore focused on the mechanisms underlying students changing their minds after they had previously committed to a higher education programme. Eighteen semi-structured interviews with Dutch pre-university students in their final year at school were held just before final enrolment: students retraced their higher education programme choice process over time with the help of a timeline and a storyline. Interviews were thematically analysed. We identified two mechanisms whereby students, sometimes quite suddenly, switched in their commitment from one programme to another and two mechanisms that could hold them back from committing to another programme despite having doubts. This paper provides detailed theoretical insight into how students make higher education programme choices over time and concludes with practical recommendations on how to support students.

Introduction

Students’ choice of higher education programmes has long been the focus of research (e.g. Bergerson Citation2009; Chapman Citation1981), as this choice is considered to be the first consequential decision adolescents have to make for their future (Du Bois-Reymond Citation1998). As around a third of students may start regretting the programme choice they have made (Kucel and Vilalta-Bufí Citation2013) and may drop out of a programme (Ulriksen, Madsen, and Holmegaard Citation2010), research aims to understand the complexity of the higher education programme choice process and how students can be supported in making the best decisions (Bergerson Citation2009; Holmegaard, Ulriksen, and Madsen Citation2014).

Research has shown how students’ educational and career choice processes reflect identity work, with notable impact of social background, parental and peer attitudes, race and gender (Archer et al. Citation2010; Cabrera and La Nasa Citation2000; Lent, Brown, and Hackett Citation1994). Although research into such factors has been important in stressing the personal and social nature of choices, Bergerson (Citation2009) calls for more process-oriented research to better understand how students experience and make sense of their future, particularly the considerations and doubts they have over time when choosing a higher education programme.

Recent studies on students’ experiences in the higher education programme choice process have shown the critical role of students’ interests (e.g. Holmegaard Citation2015). Interests are any sort of activities, ideas, and objects students identify with and aim to re-engage with over time (Akkerman and Bakker Citation2019; Barron Citation2006; Dewey Citation1913). Interests are therefore inherently future-oriented and inform life choices (Nurmi Citation1991; Sharp and Coatsworth Citation2012). Students have been found to weigh and contrast their multiple interests in order to make a higher education choice, considering what interests are most important for them to pursue in an educational and career context (Hofer Citation2010; Holmegaard Citation2015; Vulperhorst et al. Citation2018). This process includes an exploration of how interests relate to available programmes, as not all interests and combinations of interests are realistic or can be pursued in more or less set study programmes (Vulperhorst, van der Rijst, and Akkerman Citation2020).

When students find a programme which attunes with their most valued interests, they may commit themselves to this study programme, meaning they aim to enrol in this specific programme in the future (Germeijs and Verschueren Citation2006; Luyckx, Goossens, and Soenens Citation2006). Both Holmegaard, Madsen, and Ulriksen (Citation2014) and Vulperhorst, van der Rijst, and Akkerman (Citation2020) have shown that, despite such intentions, students can suddenly decide to switch from one programme to another before final enrolment. These studies have not yet explained why, after finding a programme that attunes well with their interests, students change their minds and commit to another programme. This is the focus of our study: we aim to uncover the pre-enrolment mechanisms underlying switching, i.e. the explanatory processes that underly students changing their commitment from one programme to another. Uncovering these mechanisms should provide more detailed insight into the complexity of students’ higher education choice processes as they unfold over time. Moreover, such insight can help counsellors (i.e. educational professionals that aim to provide support, information, and guidance to students) in making more informed decisions on how to support and guide students in making a higher education programme choice.

An interest-based higher education programme choice

Students have multiple interests in daily life that they want to pursue in their future. These interests are always in competition, as time and energy to spend on our interests is finite (Hofer Citation2010). In everyday life, with devoted time slots for specific sorts of activities (e.g. hobby club), deciding which interest to spend time on is often intuitive. Pursuing interests then comes naturally and does not require consideration. However, when making high-stakes decisions, such as choosing a higher education programme, students are challenged to reflect on their interests more explicitly and actively, as the decision to pursue a specific interest in a programme may imply that they are not able to pursue other interests for the coming years or in their future at all (Akkerman and Bakker Citation2019; Holmegaard Citation2015; Holmegaard, Madsen, and Ulriksen Citation2014). Such reflection has been found to generate a process of revaluation of interests, also relative to one another (Vulperhorst, van der Rijst, and Akkerman Citation2020), although not necessarily in an immediate and listwise rational process reviewing the costs and benefits of pursuing specific interests in favour of others.

An interest-to-programme and programme-to-interest perspective

Considering which interests to pursue in a higher education programme, Vulperhorst, van der Rijst, and Akkerman (Citation2020) found that students not only need to make sense of the interests that are most important for them to pursue in their future (i.e. an interest-to-programme perspective), but also have to find out how future programmes might afford the pursuance of important interests (i.e. a programme-to-interest perspective). Often, the interest-to-programme and programme-to-interest perspectives do not align; how students would ideally combine and pursue interests is not directly compatible with how interests can be pursued in programmes. Students therefore need to attune and negotiate an interest-to-programme and programme-to-interest perspective over time, to make a decision on which programme to pursue.

To be more specific, the interests students consider to be most important from an interest-to-programme perspective feed forward to relevant programmes that they explore (e.g. based on my interests in Chemistry and History I will explore programmes related to these interests). The more divergent or convergent students’ interests, the more or less diverse the programmes to be explored. Considering how interests attune with specific programmes from a programme-to-interest perspective feeds back to interests: framing interests in a formal landscape of domains and disciplines, we found that students may come to label, prioritise or cluster their interests differently, coming to see either more or less divergence in their interests (e.g. based on my exploration of the Biology programme I realise I am not so interested in Biology as I thought and based on my exploration of the History programme I realise I am actually interested in Art History and Archaeology).

Committing to a programme

When students commit to a programme, this means that they aim to enrol in that specific programme (Crocetti Citation2017; Germeijs and Verschueren Citation2006; Klimstra and van Doeselaar Citation2017; Meeus Citation2011). It is a common perception that the programme choice process ends once students are committed to a programme. Once students have concluded which specific programme fits their most valued interests, there appears no reason to continue exploring and considering other programmes (Germeijs et al. Citation2012; Germeijs and Verschueren Citation2006). Nonetheless, several studies have shown that students can break their commitment to a programme and chose to enrol in another (Cleaves Citation2005; Holmegaard, Madsen, and Ulriksen Citation2014).

Literature on life transitions and narratives more generally has stressed the dynamic nature of future orientations and choices, as people’s decisions will always be reconsidered in the light of new experiences (Bruner Citation1990; Zittoun and Gillespie Citation2015; Zittoun and Valsiner Citation2016). Holmegaard, Madsen, and Ulriksen (Citation2014) and Holmegaard, Ulriksen, and Madsen (Citation2015) found how this also applies to the higher education programme choice, as students may continue to talk about their future and may encounter new information about programmes, and so may change their orientations towards a programme they have committed to accordingly. Although these studies have shown that students may switch from one programme to another, the specific mechanisms behind this process remain undefined.

The present study

The present study focused on the mechanisms that underly students switching in their commitment from one programme to another when they are choosing a higher education programme. This will theoretically contribute to understanding how students make a higher education programme choice over time. Based on this insight, practical recommendations are shared on how counsellors can support students in making a programme choice over time. Specifically, we formulated the following research question: What mechanisms underly students’ switches in their commitment from one study programme to another when they are choosing a higher education programme?

Method

Semi-structured interviews with students were held. The interviews allowed students to unfold their higher education programme choice process, including how and why their commitment to programmes changed over time.

Context

In the Dutch education system, students are placed into tracks from secondary education onwards. After 8 years in primary school, students enrol in the pre-vocational, general secondary, or pre-university track. Roughly twenty per cent of all students enrol in the pre-university track. The present study focused on pre-university students as students in this track transfer most often to higher education. At the beginning of the 4th year of secondary school, students have to choose subject clusters known as educational profiles (Culture & Society, Economics & Society, Nature & Health, or Nature & Technics). After the 6th year, students generally transition to higher education, where they choose to enrol in a specific programme at a specific institution. Often, the pre-university diploma is enough to enrol in a programme, although some programmes have additional criteria and selection procedures or require students to have graduated from school with a specific educational profile. All Dutch universities are public institutions, have roughly the same academic standing, and enrolment costs are the same for every institution..

Participants

Eighteen pre-university students in the final year of secondary school (6th year) were interviewed. Participants were selected from a larger sample of 244 pre-university students who participated in an experience-sampling study focused on students’ interest development. Students of the larger sample were recruited through eleven high schools. Twenty students were purposefully selected for maximum case variation, based on gender, geographical location (e.g. students from urban and rural schools), and educational profile. Eighteen students accepted and were able to participate: 10 girls and 8 boys between 17 and 19 years of age.

Procedure

The participants were interviewed following a semi-structured approach. It was the second time we had interviewed these students about their higher education programme choice. The first interview was solely focused on students’ interests and the programmes they were considering (see Vulperhorst, van der Rijst, and Akkerman Citation2020), without focusing on their commitment to a programme over time, which is why we only describe and analyse the second interview in this paper.

Interviews were carried out a few weeks or days before students enrolled in higher education, apart from one student, whose interview was held four days after the student enrolled in the programme. All interviews were conducted by the first author and were held in a location the participant preferred: in school, in the library, or at home. Interviews lasted between 45 minutes and 105 minutes. Consent was obtained from students to record the interview. Recordings were transcribed verbatim and subsequently analysed.

Instrument

The interview aimed to elicit all considered interests and programmes over time, paying specific attention to whether students had committed to a programme and whether this changed. To help them recall considered interests and programmes over time, and to let them narrate more freely compared to a regular and more structured interview, a timeline was created with the students (Adriansen and Madsen Citation2014; Sheridan, Chamberlain, and Dupuis Citation2011). To elicit students’ commitment to programmes, a storyline was also created with them where they had to indicate and explain how certain they were about pursuing certain programmes over time. In a storyline, students draw the development of a process where the horizontal axis typically represents time and the vertical axis a measure of growth. Storylines help students reflect on how processes develop over time and why processes might change over time (for more information see Beijaard, Van Driel, and Verloop Citation1999; Sandelowski Citation1999; Scager et al. Citation2013).

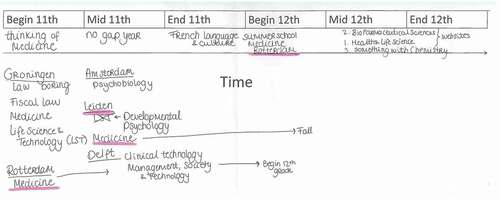

A linear timeline was given to the students on A3 paper that showed the passage of time from the 4th year to the 6th, with separate blocks for the beginning, middle, and end of each year, as students typically are considering what to study in this period (e.g. Cabrera and La Nasa Citation2000). Students could extend the timeline if they had been thinking about their future before the 4th year. They were encouraged to fill in the timeline with events they found related to their higher education programme choice process (e.g. conversations, thoughts and considerations, moments of information gathering). Narrative questions were formulated that focused on explaining, drawing and writing down these events (e.g. What did you do? What did you consider? What happened next?). An example of part of a constructed timeline can be found in .

Next, the storyline was created with the students. We gave them an A3 sheet with a vertical axis that ranged from −5 (I am very uncertain which programme I should pursue), to 0 (I am not certain/uncertain which programme I should pursue), to 5 (I am very certain this is the programme I want to pursue). For the horizontal axis we used the previously constructed timeline. We instructed the students to indicate how certain they were they wanted to pursue a specific programme at each moment in time. No further instruction was given on how to create the storyline, to allow students the freedom to create the shape and look of their own storylines. Questions were asked during and after drawing to clarify why certain points were higher or lower than previously created points or why the line/dot/graph changed direction, to elicit statements reflecting their commitment to a programme and their reasoning about why they may have switched in their commitment from one programme to another.

Analysis

Thematic analysis (see Braun and Clarke Citation2006) was applied to identify commitment switching mechanisms. We analysed both the explicit reasons students had for switching or not switching and their reasoning from an interest-to-programme and programme-to-interest perspective when their commitment to a programme changed over time. Combining both explicit reasons and students’ reasoning allowed us to identify, in a more holistic manner than when only focusing on students’ explicit reasons, what mechanisms were underlying to students students’ switches in their commitment from one programme to another.

First, to get a grip on students’ interests, programmes, and commitment over time, we read through the interview transcripts and looked at students’ timelines. We coded students’ considered interests, considered programmes, and commitment. The specific coding rules and examples of the content that was coded in this step can be found in .

Table 1. Coding rules and examples of coded data

We subsequently coded when students reasoned from an interest-to-programme perspective over time (e.g. when they considered which interests, whether interests were more convergent or divergent, and how this led to exploring specific programmes over time) or a programme-to-interest perspective over time (e.g. how considered interests attuned to programmes and how programmes could change the considered interests over time) and whether and why students indicated that they were committed to a programme over time. This resulted in a list of codes clustered per person per time point.

We used the codes and the full transcripts to create a summary of the higher education programme choice process per student over time, to get more grip on how their reasoning from an interest-to-programme and programme-to interest perspective changed, when they committed to a programme, when they broke off their commitment to a programme, and when they committed to a new one. This allowed us to identify eight students who committed to a programme before final enrolment but subsequently changed their minds. We then identified two commitment switching mechanisms based on the explicit coded reasons given by students to explain why they changed their commitment and through comparing and contrasting whether and how students’ reasoning changed from an interest-to-programme perspective (e.g. a shift in interests to pursue over time) and a programme-to-interest perspective (e.g. a shift in considered programmes).

Analysing the explicit reasons and changes in interest-to-programme and programme-to-interests reasoning, we found that students could be hesitant to switch or explicitly kept holding on to the programme they were committed to, even though switching would have led them to better attune their considered interests and programmes. We therefore decided to analyse all students that were committed to a programme before final enrolment, to identify themes that could explain why students would not break off their commitment to a programme. Again, we analysed both explicit reasons for students staying committed to a programme over time and, more holistically, whether something in their reasoning from an interest-to-programme and programme-to-interest perspective changed once they had committed to a programme. This revealed two commitment preservation mechanisms.

Quality

To ensure the quality of our instrument, we piloted the instrument with two 6th year pre-university students who were not included in the sample. We changed the wording of some questions to simplify them and we enlarged the timeline and storyline format, so students had enough space to draw and write. To ensure the quality of our analysis, we conducted an audit (Akkerman et al. Citation2008). In this summative audit, an independent researcher within our research institute with expertise on students’ higher education programme choice was asked to assess the dependability and confirmability of the data analysis (Guba Citation1981). All transcripts, timelines, storylines, codes, and summaries were made available to the auditor. The auditor agreed with the data analysis and found it transparent.

Results

Through tracing students’ reasoning from an interest-to-programme and programme-to-interest perspective and their commitment to programmes over time, we identified several mechanisms that underly students (not) switching in their commitment from one programme to another. To exemplify these mechanisms, we created three figures that each portray the choice process of a student over time (see ). The horizontal arrow at the top of the figure illustrates the passing of time. The start of each school year that students reported in their timeline is marked in each figure. Below the horizontal arrow, the divergence of their considered interests, exploration of programmes and commitment to a programme are summarised over time.

As can be seen from the figures, students’ considered interests fed forward (from an interest-to-programme perspective) to which programmes they explored, which is illustrated by regular arrows. At the same time the dotted arrows show how the explored programmes fed back to students’ interests, potentially changing which interests they considered pursuing. We highlighted at each time whether students were committed to a programme or not.

Of the eighteen students interviewed, sixteen had committed to a programme before communicating their final choice to an institution. Of these sixteen students, eight made one or more switches, all of which were made before they had to communicate their final choice to higher education institutions: in the period of four months between communicating their final choice and actual enrolment, no students switched in their commitment from one programme to another. When students broke off their commitment to a programme, they could directly commit to another programme (as in Jolene’s case, see ), or they could decide to wait a while before committing to a new programme (as in Marlon’s case, see ). Below we will illustrate the two commitment switching and commitment preservation mechanisms.

Optimisation mechanism

Students could switch once they became aware of a more optimal higher education programme, which attuned better with their current considered interests than the programme they had been committed to. We found that students continued reasoning about making a higher education programme choice, even after they were committed to a programme. They kept considering several programmes and kept weighing their interests to determine which interests they wanted to continue in which programme (see the cycles of feed forward and feed back in all figures after students’ commitment to a programme). This was also highlighted by Riley: ‘So here I thought, I am going to study Architecture, but I felt I should keep my options open’.

This continuous contrasting and weighing of interests and programmes to the interests and programme they were committed to functioned as a check and, in some cases, students realised they would rather pursue other interests in another programme. These students could make a switch in their commitment to a programme. This is illustrated by Jolene (see ) who was committed to pursuing her interests in ecology and nature in the Biology programme but also continued exploring other options:

In 5th year I visited the university for an open day for the Biology programme. At the time I was convinced about studying Biology, but I wanted to check whether it was the right choice one last time. By coincidence I saw Literature Studies, and checked whether I could fit it in my schedule on the open day. I really liked it [Literature Studies], which is why I dropped Biology and focused on Literature.

Contrasting the programmes of Literature Studies and Biology, Jolene realised she could pursue a programme with her interests in books and the library, which she preferred over her interests in ecology and nature which she could pursue in the Biology programme. Jolene had not considered pursuing her interests in books and the library academically before exploring Literature Studies. She then became aware that she would love to pursue these interests academically. Consequently, Jolene switched from being committed to Biology to committing to Literature Studies.

Discontinuation mechanism

Students could also switch in their commitment when they realised that the programme they were committed to did not attune that well anymore with their considered interests. In contrast to the previous mechanism, where students found a better programme, but often would have considered enrolling in the programme they were previously committed to, these students abandoned the idea of pursuing the programme they were committed to when they realised that their interests did not attune that well with this programme.

Students could realise through extended exploration that a programme did not attune as well as they previously thought. Lana for example remarked:

So, for the whole of the 5th year I was focused on Biomedical Sciences, until the ‘student for a day’, then I thought, no way I am going to study that … I was like triggered, do I really like studying this, well maybe not.

At this introductory activity for prospective students (‘the student for a day’), Lana realised Biomedical Sciences did not attune that well with her interests in brains and nutrition. Consequently, Lana stopped committing to Biomedical Sciences.

Students could also realise the programme they were committed to did not attune that well anymore with their interests, because the interests they aimed to pursue changed over time. Students’ interests were constantly developing in their daily lives. Based on new experiences, interests could become more or less important for students to continue in their future, which could lead to a shift in which interests they wished to pursue most.

Looking for example at Marlon (), we see that Marlon was committed to Tax Law at the end of the 5th year in the general secondary education track because of his strong interest in economics. Transitioning to the 5th year in the pre-university track, he realises his interest in economics has declined:

I wrote an essay about the depression and the subsequent economic crisis for school … and that gave me a really negative image of the world of economics … And also, from conversations with others in my family who worked in that [economic] sector, I got like an image of economics which I did not feel fitted me … So I felt, well, maybe I should consider something else.

Marlon subsequently changed his orientation: he decided not to commit to any programme while he considered pursuing multiple interests and programmes again.

Students could also make a direct switch to a new programme when they dismissed the programme they were committed to, if they had already explored a programme that attuned with the interests now considered to be more important. Edward, for example, was interested in Chemistry, Mathematics, and Physics and explored programmes related to these interests. Edward committed to a Physics programme in the 5th year, as he was most interested in Physics. He realised later:

I think at the end of the 5th year we had a chapter [for Physics] that I really did not like, and from the 5th year on I had a Mathematics teacher who was nice. It was more of a realization moment, I think … I thought, actually, I do not like Physics that much. Once the idea was there, I realized I liked Mathematics more.

Edward consequently switched in his commitment from the Physics programme to a previously explored Mathematics programme.

Self-fixation mechanism

We also found two commitment preservation mechanisms. First, we discovered how students could fixate themselves on their most valued interests and programmes. Then we noticed how students could deliberately downplay information that appeared to contradict their thoughts and orientation, disregarding the idea that another programme may attune better with their interests or that other interests may over time have become more valuable for them to pursue in their future.

Grover, for example, mentioned but downplayed information that implied that the programme he was committed to attuned to a lesser extent with his considered interests than he thought when he committed to this programme. Grover was strongly interested in computers, technology, and games. He therefore committed to Software Science at the beginning of the 5th year, as, at first glance, this aligned with all his interests. He remarked after several open days:

Yeah it is really theoretical, it is more about what Software Science is and not just doing it like practically … like a lot of theory books, and not how you do Software Science, also history about computers, so … I want something more practical.

Even though Grover voiced some doubts about the programme, as the programme went beyond his practical interests in programming and designing games, this did not prompt him to explore other programmes. Grover stayed committed to Software Science arguing that once enrolled in the programme, he would probably spend most of his time learning to programme and design games, instead of having to learn Mathematics and the history of Software Science.

This fixation with enrolling in a specific programme with specific interests, could also make students disregard strengthened interests in other domains. For instance, Carla (see ) was committed to studying Medicine, and notes the following about her interest in Chemistry:

I started liking Chemistry more in the 6th year, but that was just at the end of the year, so I did not pursue it … After I was not selected to study Medicine … my father said, why don’t you go to study Chemistry? … But I knew quite quickly that I wanted to study something in preparation for Medicine, as I want to try to get through the selection next year … If there was no Medicine, I would have probably started studying Chemistry.

Carla mentioned how only after her father explicitly mentioned the possibility of studying Chemistry, did she realise she could pursue this interest in her future. Nonetheless, as she was set on studying Medicine, she did not really consider pursuing her interest in Chemistry, although she acknowledged she may have really liked studying Chemistry.

Social confirmation mechanism

Students could also stay committed to a programme when significant others were convinced that the programme they were committed to was the best choice for them. If this was the case, students had to convince and explain to significant others why a switch would lead to an even more plausible choice for them. Without a strong rationale to pursue a different programme, students could confirm their social environment, and not make a switch in their commitment. This social confirmation mechanism is illustrated by Jolene (see ). As mentioned above, Jolene wanted to switch from Biology to Literature Studies, but making this change was at first somewhat problematic for her as her parents were not convinced about her pursuing Literature:

My father was very confused, I really had to convince him. He is himself also very interested in nature and biology and he went with me to the Biology open days and saw me very enthusiastic there. And I could not convince him in the beginning, which is why I was also doubting what I should do … I then had multiple conversations with my parents about whether Literature Studies would be a smart choice for me, but after they finally saw that I really liked Literature it was okay.

As Jolene kept talking with her parents about changing her intention from the Biology programme to the Literature Studies programme, she was eventually able to convince them that making such a switch would be the best choice for her.

Discussion

We uncovered two commitment switching mechanisms and two commitment preservation mechanisms when students are making a higher education programme choice. In accordance with recent studies focused on programme choice (Cleaves Citation2005; Holmegaard, Madsen, and Ulriksen Citation2014; Vulperhorst, van der Rijst, and Akkerman Citation2020), we found that students did indeed switched in their commitment, either directly committing to another programme or leaving the alternatives open to explore and decide later.

Theoretical implications for the higher education programme choice process

The present study contributes to higher education programme choice theory. Building on Vulperhorst, van der Rijst, and Akkerman (Citation2020), we have shown in more detail how students attune an interest-to-programme and programme-to-interest perspective over time. We have shown that this attuning of the two perspectives does not end once students have found a programme that attunes well with their considered interests, supporting the suggestion that the higher education programme choice is a process without a clear end point and continues even after students have enrolled in a programme (Holmegaard, Madsen, and Ulriksen Citation2015; Taylor and Harris-Evans Citation2018).

We found that students kept searching for a more optimal higher education programme choice by contrasting other considered interests and programmes to those they were committed to, and that sometimes students came to the conclusion that another programme would suit them better. Students often feel that the future is set in stone after they have made a higher education programme choice, as they feel they have to pursue a career in that direction and are less aware of choices they can make after enrolment (Holmegaard, Ulriksen, and Madsen Citation2014; Kucel and Vilalta-Bufí Citation2013). Students may consequently feel under pressure to make the best choice possible as they are scared of finding out they made a wrong choice in hindsight (Du Bois-Reymond Citation1998).

During their continued exploration and comparison of interests and programmes, students could experience discontinuity: they could come to realise that the programme they had committed to was not a good option for them anymore. Holmegaard, Madsen, and Ulriksen (Citation2014) found that students may reconsider their future programme based on new information, we have shown in more detail that students may learn through extended exploration that a programme does not attune with their interests as well as they thought or they may come to realise that their interests have developed and consequently may not attune that well anymore with the programme they are committed to. Our findings support the argument made by Gravett (Citation2021) and Taylor and Harris-Evans (Citation2018), that the higher education choice process is a non-linear, iterative process rooted in daily life, in which students constantly try to make sense of the upcoming transition based on their lived experiences.

We also found that students could be hesitant about making a shift in their orientation from one programme to another, even when such a shift might lead them to enrol in a programme that is better attuned to their interests. First, we found that students could fixate on the programme and interests they had committed to, creating a set narrative about why this would be the most logical choice for them. Consequently, they could downplay or try to ignore experiences that would contradict this idea. This fixation on specific narratives resonates with findings that some narratives may become dominant. Dominant narratives are resistant to change as all new experiences are assimilated in the dominant narrative; people may consequently struggle to form a different, more fitting narrative about themselves (see Zittoun et al. Citation2013). For the higher education choice process, this finding illustrates why students may sometimes seem not to take up new information or may, in the eyes of others, make unfitting higher education programme choices.

Second, we found that students confirmed ideas of significant others. Students could find it difficult to switch their commitment from one programme to another, if they had already communicated their commitment to a programme to significant others. Other studies have already highlighted that students not only have to make an appropriate choice for themselves, but are also required to make a logical programme choice in the eyes of others (Brunila et al. Citation2011; Holmegaard Citation2015). We have illustrated in more detail how these significant others can hold students back when they try to shift their commitment from one programme to another. If students are unable to convince others that switching is the most logical choice for them, they may confirm their social environment and will not make the change. The social confirmation mechanism may also explain why we found that students rarely made multiple changes, as they may have lost credibility in the eyes of significant others about making a logical higher education programme choice if they committed to multiple programmes over time.

Limitations and future research

In the present study students recalled which interests they considered, what programmes they explored and how committed they were to specific programmes over time. As others have argued, students may interpret their past experiences in the light of the present to make a more consistent narrative (Holmegaard, Ulriksen, and Madsen Citation2015). This implies that students may not recognise or recall all commitment changes they have made when reasoning from the present situation and the programme they are committed to now. Following methodological recommendations (e.g. Bagnoli Citation2009), we used timelines and storylines to help students better recall and reconstruct their prior situations. Future research should nonetheless focus on tracing the higher education programme choice process longitudinally over time, to validate and add to our results.

The present study was conducted in a Dutch educational context. Even though studies have shown that students in other educational contexts also attune their interests with possible programmes to come to a higher education programme choice (see for an example in Portuguese context Tavares and Cardoso Citation2013), one may question whether similar commitment switching and commitment preservation mechanisms would be found in other educational contexts. Future research in different educational systems may provide insight into this.

Future research could focus on whether students change programmes after enrolling in a programme, and whether similar commitment switching mechanisms can be identified in that period of students’ lives. None of the students in our study switched between programmes in the time between communicating their final choice to the institution and enrolment, suggesting that students may be less inclined to switch once enrolled in a programme. Changing programmes after enrolment would seem likely to have more consequences for students than switching their commitment to a programme before enrolment, as changing course after enrolment would require them to drop out of their programme and lose the time already invested in it (Bradley Citation2017). Nonetheless, studies focused on the future choices of students after enrolment have shown that some students may come to regret their study choice (Kucel and Vilalta-Bufí Citation2013) or consider pursuing a programme that attunes better with their interests (Malgwi, Howe, and Burnaby Citation2010), which may result in them switching after enrolment (Lykkegaard and Ulriksen Citation2019).

Practical implications

Although our aim was to theoretically understand why students (do not) switch in their commitment from one programme to another when making a higher education programme choice, we can provide some practical recommendations based on the found commitment switching and commitment preservation mechanisms. The found commitment switching mechanisms highlight that students keep evaluating their interests and programmes after they pronounce their commitment to a programme. This suggests that counsellors should keep guiding students through the process of choosing a programme even after students have pronounced their commitment to a programme. Moreover, our commitment preservation mechanisms suggest that counsellors should be aware of the possibility that students keep holding on to specific interests and the programme they have committed to, even when another programme may better attune with their current interests. It is therefore important that counsellors keep reflecting with students on their important interests and possible programmes and emphasise in these ongoing conversations that changing your orientation from one programme to another is a process that happens quite frequently when still deciding on a higher education programme. Counsellors can then potentially make students aware that switching their commitment from one programme to another may, sometimes, lead to a more suitable programme for them.

Defining commitment

Based on our findings, we can provide more insight into how students’ commitment during the higher education programme choice process should be defined. Our findings suggest that commitment is neither a stable state that functions as an end point of the programme choice process (as suggested in Germeijs and Verschueren Citation2006), nor a meaningless state that continuously changes (as one may argue based on narrative literature; e.g. Holmegaard, Ulriksen, and Madsen Citation2015). Rather, we propose to understand programme commitment as taking a temporal position as a future student. This definition suggests that commitment is rather fixed: through taking an explicit position as a future student of a programme, a student communicates that other positions as students of different programmes are less desirable; students can then be held responsible for keeping this position over time by their social environment. Moreover, from the position as a future student of a specific programme, students may ignore, disregard or change the interpretation of daily life experiences to make keeping this position the most logical choice for them. Students may nonetheless realise that a shift in position may be needed when another position has been found that is more desirable to them or when they realise that the position as a future student of a specific programme is less desirable than previously thought.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Alex Janse for conducting the summative audit.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

J. P. Vulperhorst

J. P. Vulperhorst is working for the Department of Education at Utrecht University as a PhD-candidate and university teacher. In his research Vulperhorst focuses on how students’ multiple interests develop over time and how students’ make a choice for a higher education programme based on these multiple interests.

R. M. van der Rijst

R. M. van der Rijst is an associate professor at the Leiden University Graduate School of Teaching (ICLON). His academic work focuses specifically on research based teaching and learning and teacher professional development. The majority of his projects are connected to the field of teaching and learning in higher education.

H. T. Holmegaard

H. T. Holmegaard is an associate professor at the Department of Science Education at University of Copenhagen. Her research centres around understanding students’ identity-work in science. She has published on students’ choices of and transition into higher education science, students’ drop out and first year experiences.

S. F. Akkerman

S. F. Akkerman is full professor of Educational Sciences at Utrecht University. In her research she focuses on transitions of students and collaborations between professionals across disciplinary, educational and organisational contexts and the impact of such multi-systemic participation or transition on interest and identity development.

References

- Adriansen, H. K., and L. M. Madsen. 2014. “Using Student Interviews for Becoming a Reflective Geographer.” Journal of Geography in Higher Education 38 (4): 595–605. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2014.936310.

- Akkerman, S., W. Admiraal, M. Brekelmans, and H. Oost. 2008. “Auditing Quality of Research in Social Sciences.” Quality & Quantity 42 (2): 257–274. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11135-006-9044-4.

- Akkerman, S. F., and A. Bakker. 2019. “Persons Pursuing Multiple Objects of Interest in Multiple Contexts.” European Journal of Psychology of Education 34 (1): 1–24. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10212-018-0400-2.

- Archer, L., J. DeWitt, J. Osborne, J. Dillon, B. Willis, and B. Wong. 2010. “‘Doing’ Science versus ‘Being’ a Scientist: Examining 10/11-year-old Schoolchildren’s Constructions of Science through the Lens of Identity.” Science Education 94 (4): 617–639. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.20399.

- Bagnoli, A. 2009. “Beyond the Standard Interview: The Use of Graphic Elicitation and Arts-based Methods.” Qualitative Research 9 (5): 547–570. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794109343625.

- Barron, B. 2006. “Interest and Self-Sustained Learning as Catalysts of Development: A Learning Ecology Perspective.” Human Development 49 (4): 193–224. doi:https://doi.org/10.1159/000094368.

- Beijaard, D., J. Van Driel, and N. Verloop. 1999. “Evaluation of Story-Line Methodology in Research on Teachers’ Practical Knowledge.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 25 (1): 47–62. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/S0191-491X(99)00009-7.

- Bergerson, A. A. 2009. “College Choice and Access to College: Moving Policy, Research, and Practice to the 21st Century.” ASHE Higher Education Report 35 (4): 1–141.

- Bradley, H. 2017. “‘Should I Stay or Should I Go?’: Dilemmas and Decisions among UK Undergraduates.” European Educational Research Journal 16 (1): 30–44. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1474904116669363.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Bruner, J. S. 1990. Acts of Meaning. Vol. 3. Cambridge, MA: Harvard university press.

- Brunila, K., T. Kurki, E. Lahelma, J. Lehtonen, R. Mietola, and T. Palmu. 2011. “Multiple Transitions: Educational Policies and Young People’s Post-Compulsory Choices.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 55 (3): 307–324. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2011.576880.

- Cabrera, A. F., and S. M. La Nasa. 2000. “Understanding the College-Choice Process.” New Directions for Institutional Research 2000 (107): 5–22. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/ir.10701.

- Chapman, D. W. 1981. “A Model of Student College Choice.” The Journal of Higher Education 52 (5): 490–505. doi:https://doi.org/10.2307/1981837.

- Cleaves, A. 2005. “The Formation of Science Choices in Secondary School.” International Journal of Science Education 27 (4): 471–486. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/0950069042000323746.

- Crocetti, E. 2017. “Identity Formation in Adolescence: The Dynamic of Forming and Consolidating Identity Commitments.” Child Development Perspectives 11 (2): 145–150. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/cdep.12226.

- Dewey, J. 1913. Interest and Effort in Education. Boston, MA: Riverside Press.

- Du Bois-Reymond, M. 1998. “‘I Don’t Want to Commit Myself Yet’: Young People’s Life Concepts.” Journal of Youth Studies 1 (1): 63–79. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13676261.1998.10592995.

- Germeijs, V., K. Luyckx, G. Notelaers, L. Goossens, and K. Verschueren. 2012. “Choosing a Major in Higher Education: Profiles of Students’ Decision-making Process.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 37 (3): 229–239. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cedpsych.2011.12.002.

- Germeijs, V., and K. Verschueren. 2006. “High School Students’ Career Decision-making Process: A Longitudinal Study of One Choice.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 68 (2): 189–204. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jvb.2005.08.004.

- Gravett, K. 2021. “Troubling Transitions and Celebrating Becomings: From Pathway to Rhizome.” Studies in Higher Education 46 (8): 1506–1517. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1691162.

- Guba, E. G. 1981. “Criteria for Assessing the Trustworthiness of Naturalistic Inquiries.” Ectj 29 (2): 75. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/BF02766777.

- Hofer, M. 2010. “Adolescents’ Development of Individual Interests: A Product of Multiple Goal Regulation?” Educational Psychologist 45 (3): 149–166. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.2010.493469.

- Holmegaard, H. T. 2015. “Performing A Choice-Narrative: A Qualitative Study of the Patterns in STEM Students’ Higher Education Choices.” International Journal of Science Education 37 (9): 1454–1477. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2015.1042940.

- Holmegaard, H. T., L. Ulriksen, and L. M. Madsen. 2015. “A Narrative Approach to Understand Students’ Identities and Choices.” In E. Henriksen, J. Dillon, J. Ryder (Eds.), Understanding Student Participation and Choice in Science and Technology Education, 31–42. Dordrecht: Springer.

- Holmegaard, H. T., L. M. Madsen, and L. Ulriksen. 2014. “A Journey of Negotiation and Belonging: Understanding Students’ Transitions to Science and Engineering in Higher Education.” Cultural Studies of Science Education 9 (3): 755–786. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11422-013-9542-3.

- Holmegaard, H. T., L. M. Madsen, and L. Ulriksen. 2015. “Where Is the Engineering I Applied For? A Longitudinal Study of Students’ Transition into Higher Education Engineering, and Their Considerations of Staying or Leaving.” European Journal of Engineering Education 41 (2): 154–171. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03043797.2015.1056094.

- Holmegaard, H. T., L. M. Ulriksen, and L. M. Madsen. 2014. “The Process of Choosing What to Study: A Longitudinal Study of Upper Secondary Students’ Identity Work When Choosing Higher Education.” Scandinavian Journal of Educational Research 58 (1): 21–40. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/00313831.2012.696212.

- Klimstra, T. A., and L. van Doeselaar. 2017. “Identity Formation in Adolescence and Young Adulthood.” In Personality Development across the Lifespan, 293–308. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/b978-0-12-804674-6.00018-1.

- Kucel, A., and M. Vilalta-Bufí. 2013. “Why Do Tertiary Education Graduates Regret Their Study Program? A Comparison between Spain and the Netherlands.” Higher Education 65 (5): 565–579. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9563-y.

- Lent, R. W., S. D. Brown, and G. Hackett. 1994. “Toward a Unifying Social Cognitive Theory of Career and Academic Interest, Choice, and Performance.” Journal of Vocational Behavior 45 (1): 79–122. doi:https://doi.org/10.1006/jvbe.1994.1027.

- Luyckx, K., L. Goossens, and B. Soenens. March 2006. “A Developmental Contextual Perspective on Identity Construction in Emerging Adulthood: Change Dynamics in Commitment Formation and Commitment Evaluation.” Developmental Psychology 42 (2): 366–380. doi:https://doi.org/10.1037/0012-1649.42.2.366.

- Lykkegaard, E., and L. Ulriksen. 2019. “In and Out of the STEM Pipeline – A Longitudinal Study of a Misleading Metaphor.” International Journal of Science Education 41 (12): 1600–1625. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2019.1622054.

- Malgwi, C. A., M. A. Howe, and P. A. Burnaby. 2010. “Influences on Students’ Choice of College Major.” Journal of Education for Business 80 (5): 275–282. doi:https://doi.org/10.3200/joeb.80.5.275-282.

- Meeus, W. 2011. “The Study of Adolescent Identity Formation 2000–2010: A Review of Longitudinal Research.” Journal of Research on Adolescence 21 (1): 75–94. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1532-7795.2010.00716.x.

- Nurmi, J.-E. 1991. “How Do Adolescents See Their Future? A Review of the Development of Future Orientation and Planning.” Developmental Review 11 (1): 1–59. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/0273-2297(91)90002-6.

- Sandelowski, M. 1999. “Time and Qualitative Research.” Research in Nursing & Health 22 (1): 79–87. doi:https://doi.org/10.1002/(SICI)1098-240X(199902)22:1<79::AID-NUR9>3.0.CO;2-3.

- Scager, K., S. F. Akkerman, A. Pilot, and T. Wubbels. 2013. “How to Persuade Honors Students to Go the Extra Mile: Creating a Challenging Learning Environment.” High Ability Studies 24 (2): 115–134. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/13598139.2013.841092.

- Sharp, E. H., and J. D. Coatsworth. 2012. “Adolescent Future Orientation: The Role of Identity Discovery in Self-Defining Activities and Context in Two Rural Samples.” Identity 12 (2): 129–156. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/15283488.2012.668731.

- Sheridan, J., K. Chamberlain, and A. Dupuis. 2011. “Timelining: Visualizing Experience.” Qualitative Research 11 (5): 552–569. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794111413235.

- Tavares, O., and S. Cardoso. 2013. “Enrolment Choices in Portuguese Higher Education: Do Students Behave as Rational Consumers?” Higher Education 66 (3): 297–309. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9605-5.

- Taylor, C. A., and J. Harris-Evans. 2018. “Reconceptualising Transition to Higher Education with Deleuze and Guattari.” Studies in Higher Education 43 (7): 1254–1267. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2016.1242567.

- Ulriksen, L., L. M. Madsen, and H. T. Holmegaard. 2010. “What Do We Know about Explanations for Drop Out/opt Out among Young People from STM Higher Education Programmes?” Studies in Science Education 46 (2): 209–244. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/03057267.2010.504549.

- Vulperhorst, J. P., K. R. Wessels, A. Bakker, and S. F. Akkerman. 2018. “How Do STEM-interested Students Pursue Multiple Interests in Their Higher Educational Choice?” International Journal of Science Education 40 (8): 828–846. doi:https://doi.org/10.1080/09500693.2018.1452306.

- Vulperhorst, J. P., R. M. van der Rijst, and S. F. Akkerman. 2020. “Dynamics in Higher Education Choice: Weighing One’s Multiple Interests in Light of Available Programmes.” Higher Education 79 (6): 1001–1021. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-019-00452-x.

- Zittoun, T., and A. Gillespie. 2015. Imagination in Human and Cultural Development. London: Routledge.

- Zittoun, T., and J. Valsiner. 2016. “Imagining the past and Remembering the Future: How the Unreal Defines the Real.” In T. Sato, N. Mori, J. Valsiner (Eds.), Making of the Future: The Trajectory Equifinality Approach in Cultural Psychology, 3–19. Charlotte, NC: Information Age Publishing Inc.

- Zittoun, T., J. Valsiner, M. M. Gonçalves, J. Salgado, D. Vedeler, and D. Ferring. 2013. Human Development in the Life Course: Melodies of Living. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.