ABSTRACT

Employability is rapidly becoming a primary aim of PhD programmes. Internships have been shown to maximise students’ chances of employment; however, there is limited evidence for how relevant this approach is to social science PhD students. This article reports on a mixed methods study, designed to utilise secondary and primary programme evaluation data collected through student (n = 18) and partner (n = 15) questionnaires, student (n = 30) case study reports and interviews with partners (n = 7) in the first five years of an internship programme running at a UK Russell Group university. The study found that the social science PhD internship programme surpassed the high expectations of both PhD students and partners. The key implication of the study is that the programme boosted student employability, demonstrating to students and employers that traditional PhD social science study provides transferable workplace skills and internships enhance these skills and illuminate a wide range of non-academic employment pathways. The study provided the evidence needed to engage future students and partners in the programme, and to improve the framework for programme evaluation. An expansion of the programme is recommended, alongside ongoing monitoring and alignment of non-academic partner, university and student needs.

Introduction

Internships are increasingly a part of educational training at all levels of academic endeavour (Hurst and Good Citation2010; Wilton Citation2011). PhD study in the UK followed that of Germany and the USA (Park Citation2005), and has traditionally been associated with developing specialist knowledge and research skills (Elarde and Chong Citation2012). However, employability beyond university is becoming increasingly important as, worldwide, under half of PhD graduates remain in academia (Sharmini and Spronken-Smith Citation2020). Employment opportunities are reaching saturation point (Jackson Citation2019), with limited routes to postdoctoral study and tenureship (Molla and Cuthbert Citation2015), leaving PhD students unsure of their futures (Hancock Citation2019). In this article we focus on the future employability of social science PhD students who have accessed the opportunity to engage with non-academic partners across a range of government, industry and third-sector settings via internships.

First, we explore the increasing importance of employability and internships to PhD study. We then describe and evaluate students’ and partners’ experiences of a social science PhD internship programme, available at one UK Russell Group university, developed alongside the Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) requirements for enhancing student skills and expertise via engagement on real-world challenges with non-academic partners. The article seeks to identify whether the programme objectives were met, demonstrate how existing programme evaluation data can best be utilised and consider a future framework for programme evaluation. We conclude by identifying the key benefits of the programme from the perspective of both students and future employers, and their practical implications.

Employability and internships

For the current generation of students, economic considerations play an increasing role in the decision to progress to higher education (Moreau and Leathwood Citation2006). The typical undergraduate student debt in the UK has reached £47,000 (Hubble and Bolton Citation2018). The price tag for a PhD is a further £100,000 (Major Citation2001). PhD study is often described as fully- or partly-funded but the long hours equate to more than a full-time job at less than the minimum wage on a basic UK Research Council stipend. Opportunities for additional income through teaching or research are often limited to short-term or zero-hour contracts (Kwok Citation2017). Given the pressures of work and financial survival, over-running the official period of study by a year or two with no additional funding is not unusual. For the 40% of social science PhD graduates who leave academia post-completion, money and therefore employability matter (Gault, Leach, and Duey Citation2010).

Employability, that is, maximising employment opportunities and being competitive in the workplace, is now a key aim for PhD students and therefore a requirement on the part of universities in terms of attracting students. A recent systematic literature review of doctoral employability (Young, Kelder, and Crawford Citation2020) called for solutions to the findings – doctoral programmes need to better promote ‘soft skills’, transferable knowledge and opportunities to inform career pathways through engagement with industry. Experiential action learning and work experience have been identified as two primary methodologies through which students can address this gap (Haasler Citation2013; Miller, Biggart, and Newton Citation2013). Undergraduate internship programmes facilitate student recruitment. Research has shown that, in some sectors, 80% of positions are filled by graduates who have undertaken an internship with the company (Briggs and Daly Citation2012), a preference for mediocre interns over non-interns, and that high-performing graduate interns are able to demand higher starting salaries (Gault, Leach, and Duey Citation2010). Attitudes and aptitudes learnt in the workplace were found to be the most important factors for employers when recruiting (CBI Citation2011). However, Minocha, Hristov, and Reynolds (Citation2017) found that only 9% of 35 UK universities demonstrated close interaction with employers through internships. Given the importance of employability to PhD students and work experience to employers, it is important that universities consider this provision.

The strong evidence that internships enhance employability is currently limited to the undergraduate experience, with little known about PhD students. A large scale study (CFE Research Citation2014) designed to track PhD students’ careers, which triangulated survey and interview data from doctoral graduates and employers, provides a helpful insight into their employability and the potential benefits of internships. The overall findings were very positive, with employers describing graduates as business critical, a ‘badge of quality’ (p. 4) and both innovators and motivators. However, some employers were concerned that they lacked the general skills needed to work in a commercial environment. And some social science graduates believed that undertaking a doctorate had impacted their earnings and career progression negatively. It found that early doctoral graduates needed the opportunity to build on their work experience whilst completing their qualification to increase their employability and access their desired career more quickly, as well as give them an insight into whether they are suited to particular careers and facilitate a better matching of employers and graduates. Our study returns to Young, Kelder and Crawford’s (Citation2020) call for workable solutions to doctoral employability and a need to align industry, university and student expectations.

Internship programme evaluation

Established in 2015, the social science PhD internship programme forms part of an ESRC Doctoral Training Partnership (DTP) hosted by the school of humanities and social sciences at a Russell Group university in the UK. The partnership sponsored 30 ESRC PhD students to complete internships in its first five years across a broad range of subjects from Archaeology to Veterinary Medicine. A collaboration strategy was created to provide students with the opportunity to engage with non-academic partners through a short period of professional experience during their study period. Internships with a range of national and international industry partners were offered once a term, but students also had the option to design their own internships. All internships were bespoke and flexible (part-time or full-time, embedded or remote) to reflect individual needs.

Continuous evaluation of the experiences of students and non-academic partners was an integral part of the programme. The objectives of internships for students were to: (1) enhance subject-specific knowledge; (2) practise skills in real-world situations; and (3) develop core workplace competencies and increase employability. For partners, they were to: (1) gain a fresh perspective; (2) access specialist strengths and skills; and (3) benefit from knowledge transfer, which can reduce costs and increase productivity. The study aimed to evaluate the benefits and challenges of the internship experience in relation to these objectives, to develop an understanding of how the programme enhanced student employability and met partners’ needs and, for the university, to identify how best to promote its students and the programme.

Methods

A mixed-methods research design was selected to attain an enhanced understanding (Bryman Citation2006) of the student and partner experience of the internship programme, utilise existing promotional and evaluation data, and address any gaps in our understanding of met objectives of the programme. The internship evaluation tools that generated the secondary data evolved over time, starting with case studies initially intended for primarily promotional purposes. As the programme expanded, questionnaires were introduced to gauge student and partner satisfaction, and further evolved to provide the programme with more sophisticated feedback on its activities.

Study methods therefore included a short, qualitative case study report of the internship experience by students, collected throughout our study period (2015–2019), and early and later versions of questionnaires for students and partners, collected from 2017 to 2019, which generated quantitative and qualitative data. All students agreed to complete a case study for promotional and evaluation purposes prior to the start of their internship period to be submitted on completion. Evaluation questionnaires were distributed to all students and partners at the end of each internship. The qualitative data generated by partner questionnaires led to the development of a primary data collection tool, a short semi-structured interview with a subset of partners. This was designed to complement the questionnaire results and corroborate or challenge initial interpretations (Greene, Caracelli, and Graham Citation1989). The student case studies provided similar complementary data to enhance our understanding of their experience.

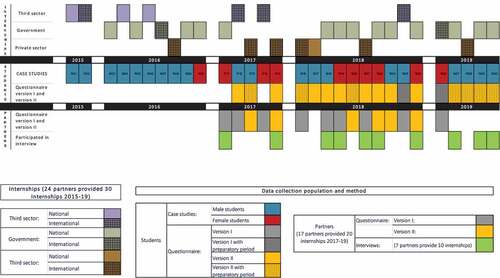

All social science PhD student interns (n = 30) involved in the first five years of the programme (2015–2019) completed a case study report. Evaluation questionnaires were only distributed from 2017, with 18 student and 15 partner completions out of 20 internships. Seven partners, providing half (10 out of 20) of the internships over this period (2017–19), agreed to be interviewed for the primary data collection phase of the study (see ). All 17 partners who were actively involved in the programme at this time were invited to interview. The ethical requirements regarding use of primary and secondary data were met as students and partners consented to case study, questionnaire and interview data being used and reported for programme evaluation purposes, and were able to opt out at the point of analysis (Boté and Térmens Citation2019). Both primary and secondary data were treated with confidentiality, only accessible to the programme evaluation team, and anonymised prior to analysis to respect individuals’ privacy but enable students, partners, and internship partner type to be distinguishable, as agreed. The research was approved by the university ethics committee.

Figure 1. Internship and data collection timeline (2015–2019) – eligible and participating population, and method of data collection.

Quantitative methods

Between 2017 and 2019, students (n = 20) and partners (n = 17) were asked to complete early or later versions of evaluation questionnaires for each internship (n = 20). The majority of students (n = 18) and partners (n = 15) returned a completed questionnaire. Gender of students was balanced and placements covered all partner types, except third sector, national partners (see , 2017–2019). The quantitative data were analysed using descriptive statistics to capture satisfaction with the internship, the intern and/or supervision provision, as well as overall programme satisfaction.

Questionnaire for students: Version I

The early student questionnaire asked students (n = 2) to rate their experience of the internship programme using a three-point Likert scale (rated agree, neutral and disagree). The questionnaire contained 17 statements: part I – the preparatory period of the internship (3 questions); part II – satisfaction with their line manager/supervisor during the internship (4 questions); and satisfaction with other aspects of the internship (10 questions) (see ).

Table 1. Evaluation questionnaire for student satisfaction: preparatory period only,1 Version I and Version II internship period results.

Questionnaire for students: Version II

The later student questionnaire evolved to provide a more nuanced evaluation of the internship and supervisory experience. It contained 13 statements for students (n = 16) to rate their experience using a five-point Likert scale (rated outstanding, good, average, below average and unsatisfactory). The statements were divided into four sub-headed areas covering skills/knowledge, management style, attitude and relationships (see ). There was some overlap with the section of the earlier questionnaire that covered satisfaction with line manager.

Finally, part I of Version I of the questionnaire, referring to the preparatory period of the internship, was reinstated in Version II questionnaires. These results are reported separately under preparatory period (see ) and indicated in .

Questionnaire for partners: Version I

The early partner evaluation questionnaire asked partners (n = 9) to rate their satisfaction with the students and the programme using a three-point Likert scale (rated agree, neutral and disagree). The questionnaire contained 19 statements (see ).

Table 2. Evaluation questionnaires for partner satisfaction: Version I and Version II results.

Questionnaire for partners: Version II

The later programme evaluation questionnaire for partners (n = 6), evolved to gather a more detailed understanding of partner satisfaction, consisted of a five-point Likert scale (rated outstanding, good, average, below average and unsatisfactory). The questionnaire contained 20 statements, covering five sub-headed areas: skills/knowledge, self-management, dependability, attitude and relationships. The statements included were similar to those in the earlier questionnaire, such as ‘demonstrates skills needed for the assigned tasks’, but the addition of sub-headings enabled them to be simplified for clarity; for example, ‘student demonstrated commitment (completion of tasks, consistency, etc.)’ was replaced by ‘dependability’ in the three areas of ‘job attendance and punctuality’, ‘completes projects by specified deadlines’ and ‘demonstrated maturity level’ (see ).

Qualitative methods

Student case study reports were collected from all internship students (n = 30) across the five-year study period. The sample contained almost twice as many male as female students and all types of partner organisation were represented (see ). This secondary qualitative data, collected to promote and evaluate the programme, was employed to gain in-depth insight into students’ expectations of and attitudes toward the internship experience. Student and partner questionnaires contained some free-text boxes to expand on quantitative responses. These are reported in the quantitative analysis section where directly related to this data, otherwise they are used to expand on the qualitative analysis. Partners made greater use of free-text boxes, indicating a need for, and informing the development of, a partner qualitative data collection tool. A semi-structured interview schedule was created, and all 17 partners engaged in the programme at this time (2019) were invited to interview. Seven partners responded and were interviewed. They represented the two largest partner types and a third of all student placements (see ).

Framework analysis was used to analyse all qualitative data, taking the a prioiri themes of the programme and study, alongside the emergent codes from the analysis of the questionnaire free-text data as the starting point. Framework analysis is a method of thematic analysis that, like similar methods, involves a process of data familiarisation, coding and searching for thematic links (Braun and Clarke Citation2006). Thereafter, it diverges in its creation of a visible analytical framework relatively early on in the process, as well as the charting of all data in its raw or summarised form to maintain the integrity of individual participant’s accounts (Green and Thorogood Citation2004) to enable between- and within-case analysis. The final phase of the process is mapping and interpreting the charted data. This approach allowed the evaluation needs of the internship programme to be directly addressed, alongside the discovery of emergent themes (Ritchie and Spencer Citation1994).

Student case study reports

The student case studies took the form of a short written report. The early reports were completed with no direction. Some students opted to set their own parameters, e.g. ‘the benefits of my internship’. Some guidelines on areas for discussion were issued in 2016, to include a summary of the collaborative activity, the aims of the activity, and to reflect on what ‘added-value’ the activity brought to the student. These were expanded on in later case study report proformas, to also consider whether the internship activity met its aims, the impact the internship had (or will have) on the student’s PhD or future career and reasons for choice of placement. The short self-reports provided rich qualitative data providing valuable insight into each student’s internship experience.

Interviews with partners

For a more in-depth understanding of partners’ experiences of hosting students, semi-structured interviews were used (Robson and McCartan Citation2016) to collect comparative information across participants (Sankar and Jones Citation2007). The interview schedule was developed, in response to the aims of the programme and the study, and the initial analysis of the free-text responses to the partner questionnaires, to explore emergent themes, identify examples and corroborate or challenge early interpretations of the partner experience. Areas for interview included partner expectations of the students, for the organisation and specific projects; the impact on, and adjustment of the student to, the workplace; the areas of academic knowledge brought to the workplace and their importance; how well the student met expectations and how they compared with other placement students; additional information needed to facilitate the placement process; and whether they would recommend the experience to others. Interviews were conducted via telephone and took 30 to 45 minutes to allow for flexibility in relation to busy work schedules and geographical dispersal. This has been shown to be an effective method of data collection in the field of education (Glogowska, Young and Lockyear Citation2011).

Results

Quantitative analysis

Questionnaire for students: I and II

Data (see ) for both versions of the student questionnaire are reported together owing to their focus on student satisfaction. Out of 20 eligible (2017–2019) students, 18 returned a completed evaluation questionnaire (I or II). Six (33%) of the 18 students rated agreed or outstanding across all statements. Collapsing the positive ratings of outstanding and good in questionnaire II with the agree rating in questionnaire I gives an overall positive rating for 15 (83%) out of 18 internshipsFootnote1 suggesting that the three objectives of the internships for students were well met.

Three students (17%) provided a small number of neutral or negative responses across both questionnaires.Footnote2 These students were located in national (n = 2) and international (n = 1) government placements. Responses were most closely related to the programme’s third student objective: development of core workplace competencies and increased employability. A single free-text response from one student recorded that employability was not applicable because she was still doing her PhD.

For those students (n = 9) rating the preparatory period of the internship, five recorded one or more neutral responses to the three questions. Free-text responses stated that one student did not recall a pre-internship workshop and another did not recall any pre-internship-related skills being taught.

Questionnaire for partners: I and II

Data (see ) for both iterations of the partner questionnaire are reported here owing to their combined focus on partner satisfaction. Out of a potential 20 questionnaires (I or II), 15 were returned over the three years (2017–2019) of quantitative data collection. Of the 15 questionnaires, 11 (73%) reported that partners ‘agreed’ in questionnaire I, or rated the student’s contribution to the workplace as ‘outstanding’ in response to questionnaire II, across all options. Collapsing the positive ratings in questionnaire II raises the overall positive rating across questionnaires to 12 (80%) out of 15 internships, suggesting that the three partner objectives of the internships were well met.

Three partner questionnaires (20%) contained six neutral and one negative response. All three sectors were represented. Neutral responses were related to students’ workplace competencies rather than the three partner objectives. The negative response related to another workplace competency: ‘student exhibited decision-making and problem-solving skills’. The free-text explanation noted that the student required support from the site mentor to identify possible solutions to problems but, once this was provided, the student was able to make good progress.

Qualitative analysis

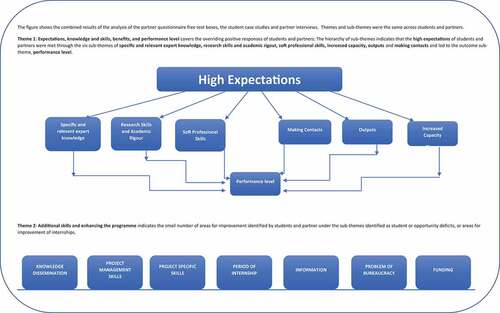

The free-text partner questionnaire and interview data, and student case study data were initially analysed separately. However, overlapping codes allow findings to be reported together here under two themes related to the benefits and challenges of the programme: ‘expectations, knowledge and skills, benefits and performance’ and ‘additional skills and programme enhancement’ (see ). Sub-themes were developed iteratively, triangulating a priori objectives of the programme with emergent themes from the student and partner expectations and experiences. The differences between student and partner perspectives, and data sources, is reported as relevant within each theme. Generic identifiers are used for the partner questionnaires – pqI and pqII, respectively. Individual identifiers are used for partner interviews (e.g. pi1) and student case studies (e.g. s16.1) to anonymously indicate the range of respondents. They are not linked to because the additional information could limit anonymity.

Figure 2. Themes from the qualitative analysis.

Expectations, knowledge and skills, benefits and performance

Student and partner qualitative responses were overridingly positive. They were captured under the hierarchy of sub-themes indicated in : High expectations were met by specific and relevant expert knowledge; research skills and academic rigour; professional soft skills; increased capacity; output; and contacts; all contributing to the overwhelmingly positive perception of performance.

High expectations of students and partners matched the programme objectives and were prevalent within the case study reports (n = 24 out of 30) and partner interviews (n = 7 out of 7). Students’ expectations were based on the reputation of the partners, ‘the prestige of working for the British Library’ (s17.1), and their research capacity, ‘they have a dedicated research team’ (s18.1). Students hoped to test or stimulate PhD ideas, ‘to identify questions for my PhD research’ (s16.4), as well as to test or gain the research and professional soft skills ‘necessary for employment’ (s18.4). They wanted to make contacts and publish, with the objective of greater employability. All hoped to gain an insight into the research–practice–policy interface to inform their next steps in academia or elsewhere. All partners expected students ‘to work to a high standard’ (pi3) and be experts – providing ‘subject-specific expertise’ (pi2) and ‘research for informing a communication strategy and evaluation for the research team’ (pi7). Their broader skill sets were to include research skills, ‘to think in depth about ideas when others don’t have the time’ (pi4), and soft professional skills, that is, being able ‘to play a role as part of the team’ (pi6), to be efficient and effective, for example the ‘ability to plan their own time’ (pi2), and to be ‘flexible’ (pi6).

Specific and relevant expert knowledge, and research skills and academic rigour

These two sub-themes refer to the expert knowledge and research skills students brought from their area of study and applied to or shared with their workplace, combining to meet the student programme objectives of enhancing subjective-specific skills and practising skills in the real world, and the partner objectives of gaining fresh perspective and accessing specialist strengths and skills. Two-thirds of students referred to expert knowledge, outlining opportunities to apply their PhD to real-world practice, ‘I was hired to provide advice as both a psycholinguist and a pragmatician’ (s17.3), or to share their PhD with others informally or formally, ‘I organised a knowledge-exchange session’ (s16.8). Just over half of students referred to applying existing research skills to designing, conducting, analysing and presenting applied, empirical research projects. Contemporary, expert knowledge was prominent in partners’ (n = 9) free-text responses and interviews. Most partners did not require project-specific knowledge, ‘it’s rare to have students studying the same topic’ (pi2); rather, it was students’ ability to stimulate, share and tailor knowledge that was important, bringing ‘fresh ideas’ (pi1), providing a ‘PhD subject-related briefing’ (pi6) or utilising their ‘area of study’ (pi5). Research skills were also key in partner (n = 9) feedback, with a focus on interns’ ‘objective perspective’ (pqI) that could be applied to ‘the delivery of complex project(s)’ (pqII). Interviewees expanded on how ‘PhD studies’ (pi1, pi2, pi3) were a ‘very good match’ (pi1) to the workplace, delivering mental agility and staff development. Adaptability was seen as a product of PhD study, both the ‘ability to mentally handle dealing with unknown topics’ (pi3) and to adapt ‘to workplace procedure methods very quickly’ (pi6).

Professional soft skills in the shape of interpersonal skills for working in a team and communicating well, and performing ascribed tasks both efficiently and effectively, overlapped with the previous two themes but were more explicitly linked to the programme student objective of core workplace competencies and increased employability. A number of projects included the output of a national or international conference where such skills were key. Both students and partners identified multidisciplinary working and communication as important to internships, where it was necessary to ‘hand over’ (pqII) work and ‘make a big impact in a short time’ (pqII, s18.6). In relation to efficiency, the attributes of being ‘adaptable’ (pqII, s18.10), ‘prompt’ (pqII), ‘focused’ (pqII), ‘proactive’ (pqII, pi2, pi4) and able to ‘multitask’ (pqII, pi7) were singled out. In terms of effectiveness, having strong ‘logistical’ skills (pqII), being ‘problem-focused’ (pqII) and ‘working well under pressure’ (pqII) were prized. These skills were attributed by partners to students as something they brought with them from their PhD training; however, students often sought to develop this increased capacity, as shown below.

Increased capacity, output and making contacts were outcome-linked sub-themes that fit all three student programme objectives, and the partner programme objectives of knowledge transfer, cost reduction and increased productivity. All students found that internships had increased their capacity in relation to their PhD and/or future career, partly as a result of new contacts (n = 20 out of 30) and outputs (n = 28 out of 30). In terms of their PhD, placements broadened perspectives and stimulated new ideas, tested and taught research skills, and provided access to participants, data and technology, otherwise unobtainable; ‘expanding my network was invaluable for my PhD research’ (s16.3, s16.5, s18.1, s19.2), both ‘elevating the quality’ (s18.1) of PhDs and enabling their completion. The two main internship outputs were event organisation and knowledge communication, through reports, blogs, presentations or publications, and, on one occasion, a brand ‘new archive’ (pi2, s17.1). These had led to funding and research opportunities: ‘presenting work led to possible future collaborations’ (s16.3).

In terms of future careers, internships provided an ‘inside view’ (s16.1) on a non-academic work environment, helping students decide ‘which career path to pursue’ (s.16.1, s16.2, s17.5, s18.10), where ‘it confirmed I prefer working within an academic environment’ (s16.3, s17.1) or allowed them to see ‘that working outside academia is an option’ (s.16.1, s16.2, s16.8, s17.2, s17.3, s18.6). They also allowed students to develop professional soft skills and to learn to value the transferability of their existing skill set: ‘I appreciate that many of the skills I possess are useful in areas outside healthcare’ (s16.3). Wider expectations were met in terms of gaining knowledge of the academic–policy–real world research interface and learning how best to communicate ideas in multiple arenas to different audiences. In terms of increased ‘employability’ (s18.5, s19.2, s19.3), ‘increased confidence’ (s17.3, s18.6, s19.1, s19.3) was regularly cited, as well as an improved CV, professional referees, new interview skills and job opportunities and, for two, gainful employment. Quite simply, the internship had ‘opened many doors which would have been closed for someone with my background’ (s17.3).

Increased capacity for partners came in the form of the expert knowledge and research skills of students, described above, and additional resources. All interviewees made it clear that PhD interns brought added value to the workplace but also, on occasion or systematically, filled a gap, ‘that they had been unable to recruit someone for’ (pi5). As one partner stated, for a more sustained model of working in government ‘the team is reliant on PhD students to help with the workload’ (pi3). They also delivered other tangible outputs, ‘a programme to put to the market’ (pi1), and staff training opportunities, to develop supervision skills and academic skills. Students also introduced partners to ‘new contacts’ (pqI) and as interns were potential ‘new recruits’ (pqII).

In feedback and interview, performance level was identified as overwhelmingly positive by almost all students (n = 27 out of 30) and all partners, meeting all six programme objectives. Students focused on the ‘life-changing experience’ (s17.3) and ‘unique opportunity’ (s16.1), with the majority concluding that ‘all my aims were met’ (s16.2, s17.1, s17.5, s18.6, s18.8, s18.9, s19.4). This outcome they in large part accredited to working with ‘inspiring’ (s18.8), ‘welcoming’ (s19.2) and ‘supportive’ (s17.1, s.17.5) people, as well as the ‘challenging’ (s19.3) and responsible nature of the work. Partners’ feedback presented equally enthusiastic comments about the students: ‘an excellent colleague setting new standards for interns and junior staff’ (pqII). A clear view was expressed that all students ‘consistently exceeded expectation’ (pqII). In interview, partners described students as ‘outstanding’ (pi1), with ‘high levels of competence’ (pi3). However, those who had experience of PhD internship programmes made it clear in interview that ‘all their PhD students are very good’ (pi3), and performance levels were ‘similar to other interns’ (pi6).

Additional skills and programme enhancement

Students and partners identified a small number of areas for improvement reported within this second theme, under the sub-themes: knowledge dissemination; project management skills; project-specific skills; period of internship; information; problems of bureaucracy; funding.

Knowledge dissemination, project management skills and project-specific skills were identified as student or opportunity deficits by a very small number of respondents and were most closely linked to the student objective of practising skills in the real world and the partner objective of knowledge transfer. In feedback, partners identified that students generally had strong communication skills, as indicated under professional soft skills; however, students experienced difficulties disseminating ‘oral’ or ‘written’ knowledge to specific audiences, for example ‘senior decision makers’ (pqI). The absence of opportunities to demonstrate project management skills was reported by one student and noted in two partner questionnaires as a student deficit, in terms of ‘the ability to achieve agreed outputs within agreed timeframes’ (pqII). Three students highlighted an absence of project-specific skills, in terms of their own ability, ‘my programming skills were not good enough’ (s17.3), or opportunities, missing out on ‘the most interesting work’ (s15.2), or access to relevant databases. One private partner identified the need for additional project-specific skills, specifically programming skills, matching with the student above; however, they did recognise that the candidate brought other expert knowledge to the placement. One interviewee noted that the ‘technical bar is lower’ for students, expecting them to need ‘employee support’ (pi1).

Period of internship, information, problems of bureaucracy and funding were briefly identified as internship-specific issues by a small number of students and partners, that is, as potential areas for programme improvement. Internships usually ran for three to six months; however, three students commented on the shortness of their experience, only ten days on one occasion, another extended from four to five weeks and a third, length unspecified, but insufficient to get the ‘finished achievement of a specific project’ (s17.3). Partner feedback similarly focused on the need for ‘longer’ and more ‘flexible’ internships to ‘benefit both the company and the intern with the range of work options’ (pqII). In interview, three partners stated that three months was the minimum term needed for students to ‘find their feet’ (pi3). The need for greater information on existing internships was highlighted, for example a ‘fact sheet or list of FAQs’ (pi5), or on how to create new internships, for example ‘through participation in events’ (pqII). Problems of bureaucracy were only identified by one student and related to the ‘elaborate application process’ (s15.2) of the partner organisation, not the programme itself. Two partners fed back on timing issues, ‘it takes too long, too much bureaucracy’, and, in contrast, there was a need for ‘more notice prior to the start date’ (pqII). Only one student raised funding difficulties in relation to the internship.

Discusssion

This study sought to develop understanding of the relatively unexplored area of PhD internships and future employability with a focus on social science students, through an evaluation of the benefits and challenges of an established social science PhD internship programme. The evaluation shows that the aims of the internship programme were well met for both students and partners across all subjects and organisations. Our first aim to enhance PhD students’ subject-specific knowledge was met for all students. Existing internship literature has largely focused on future employability and, where it has looked at the benefits of internships to academic study, the results have focused on undergraduate, final academic achievement (e.g. Binder et al. Citation2015). Our study adds to this body of literature by demonstrating the added value of internships to multiple aspects of doctoral study, including opportunities to increase capacity in academic output and contacts.

Our second aim, for PhD students to practise and enhance their skills in real-world situations, was supported by the case study reports. All students reported that this aim was surpassed. The importance of practising research skills in real-world situations has received limited attention in the internship literature. Interestingly, a small-scale Canadian study (Annan Citation2012) of graduate, research-based internship students reported that doing research outside academia unexpectedly advanced their research-based capabilities, including being able to communicate their work in non-academic settings. This finding was replicated in our study, whereby all students identified that the academic–policy–real world research interface was a key area of learning; partners, however, felt that knowledge dissemination with senior policy-makers was an area for further development. It is of note that, unlike the Canadian study, our students expected to test out and learn new research-based skills.

Our third aim for students was to develop workplace competencies and increase their employability, in line with Young, Kelder, and Crawford’s (Citation2020) call to promote soft skills, transferable knowledge and informed career choices for PhD students through engagement with industry. This aim, in relation to the development of soft professional skills, was well evidenced. Interestingly, students indicated that they not only developed new skills, similar to the findings of other studies (e.g. Anjum Citation2020; Hynie et al. Citation2011), but also increased their confidence in existing competencies. The triangulation of student and partner data indicated that students desired competencies that partners identified they often already demonstrated, suggesting that the issue was more a matter of confidence than competence. Similar to other student intern studies (e.g. McDonald et al. Citation2010; Schnoes et al. Citation2018), our study also found that the internship experience increased students’ confidence in terms of career choice. This finding adds nuance to a recent synthesis of the literature and thinking (Ismail Citation2018); that is, that internships can improve student confidence.

In terms of the partners, our aim of helping them to gain a fresh perspective appeared to be met through the expert knowledge, research skills and academic rigour our students brought to the workplace. This fits with the findings of large-scale studies (Okahana and Kinoshita Citation2018; Raddon and Sung Citation2009) on the career paths of doctoral students – that doctoral skills closely align to the workplace. Our student skill set also directly addressed our fifth aim, to help partners access specialist strengths and skills. Interestingly, these did not have to be subject-specific; rather, the breadth and depth of knowledge and skill base at this level of study were simply highly desirable to the workplace. Our final aim was for our partners to gain knowledge transfer to reduce costs and increase productivity. It was beyond the scope of the study to quantify how knowledge transfer through the use of PhD students reduced costs or increased productivity across such a range of internships. However, both students and partners reported that students were highly effective in the workplace – setting up a new archive in a public sector setting, developing a new programme to put to the market in a private sector setting and forming an integral part of some government departments. It is therefore evident that the programme brought significant added value to a variety of working environments.

Practical implications

The study found that the internship programme directly addressed recent review recommendations (Wilson Citation2012; Young, Kelder, and Crawford Citation2020) to develop student employability. More specifically, the study identified a range of key skills that were developed and/or enhanced as part of the programme, which can be incorporated into the university’s promotional material. The study, similar to the 2014 CFE finding, clearly identified that social science PhD students had the mental agility to make significant impact in the workplace. A second avenue for promotional literature, therefore, is to communicate to partners and students not only the value of internships but also the ability of social science PhD students to deliver in high-pressure work environments, challenging the skill deficit concerns of employers and student fears about the negative impact of social science PhDs on career progression (CFE Research Citation2014).

The study captured limited areas for improvement of the programme; however, some additional information on the programme may be beneficial to new partners as well as an opportunity to adjust the period of internships where both parties agree. A pre-internship workshop on effective strategies for disseminating social science research to policy-makers (Ashcraft, Quinn and Brownson Citation2020) may also be of benefit given that both students and partners recognise this as an area for further learning. Finally, in terms of the ongoing evaluation of the internship programme and future research in this area, the two themes identified in this study provide a much broader and all-encompassing list of ‘expectations, knowledge and skills, benefits and performance’ and ‘additional skills and programme enhancement’ than has previously been used to capture the student and partner experience. This list can be utilised in future programme evaluation and research.

Limitations and future research

The study made good use of existing course evaluation data, both student and partner questionnaires and student case studies, to assess the ways in which the internship programme was beneficial to all. Although the sample size was relatively small, it was representative of all internships over the period of study, capturing all student views and over two-thirds of partner views, representing almost all organisation types. However, as the evaluation materials developed the rewording the internship programme, the use of two different questionnaires for students and partners meant that analysis of the questionnaires could only be used to demonstrate levels of satisfaction across the programme. Not all questionnaires captured the preparatory part of the programme, a known point for bureaucratic problems (e.g. Cuyler and Hodges Citation2015; Hurst and Good Citation2010; Shoenfelt, Kottke, and Stone Citation2012) that warrants further investigation. The limited findings around the need for programme enhancement raised issues concerning matching expectations, ability and need in terms of project-specific and project management skills that might be further probed across this preparatory period.

Although the case studies evolved from unstructured to semi-structured, the nature of thematic framework analysis enabled them to be systematically analysed. Alternative, primary qualitative data collection through semi-structured interviews or focus groups would offer the advantage of being able to probe responses; however, the disadvantage would be that, for some, they would have taken place at a distance from the internship experience, potentially diminishing response dependability. Qualitative data collection through the free-text boxes in the earlier partner questionnaires was a useful starting point for developing the partner interviews. The sample of partners for the qualitative interviews did not represent all internship types. Future partner engagement might incorporate a request for follow-up interviews at the start of the process to improve take-up.

The mixed methods data utilised for the study could be described as representative of all students and partners taking part in the social science internship at the university over the study period and is therefore generalisable to the programme. Further research is needed to see how representative these findings are of other PhD internship programmes. An intriguing starting point is that the national, government partners reported that the students on the programme were on a par with others they worked with from different universities. A more in-depth study of the UK government programme of PhD internships would enhance our understanding of internships at this level. Equally, a study capturing the perspectives of programme administrators and student supervisors could provide a university-wide perspective on the current programme. Finally, the ongoing nature of programme evaluation allows for the expansion of the current study or the development of a more longitudinal study to capture final academic achievement and career pathways to expand understanding of social science PhD internships and employability.

Conclusion

Drawing on largely secondary course evaluation data that too often is left to gather dust, we have shown the significant range of benefits accruing from a social science PhD internship programme for both students and partners. Our results progress understanding in this relatively understudied area of PhD internships to show that, for social science students, these can have very immediate and wide-ranging benefits in relation to their studies as well as more lasting benefits in terms of confidence in their existing skill set, future employability and decision making in career choices. This confidence is passed on, equally, to partners, which offers real utility to students, partners and universities alike.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Notes

1. Excluding the preparatory period.

2. Excluding the preparatory period.

References

- Anjum, S. 2020. “Impact of Internship Programs on Professional and Personal Development of Business Students: A Case Study from Pakistan.” Future Business Journal 6 (1): 1–13. doi:10.1186/s43093-019-0006-4.

- Annan, R. 2012. Research Internships and Graduate Education: How Applied Learning Provides Valuable Professional Skills and Development for. Prepared in cooperation with the Canadian Association of Graduate Studies: Mitacs, Inc.

- Ashcroft, L. E., D. A. Quinn, and R. C. Brownson. 2020. “Strategies for Effective Dissemination of Research to United States Policymakers: A Systematic Review.” Implementation Science 15 (1): 1–17. doi:10.1186/s13012-019-0962-7.

- Binder, J. F., T. Baguley, C. Crook, and F. Miller. 2015. “The Academic Value of Internships: Benefits across Disciplines and Student Backgrounds.” Contemporary Educational Psychology 41: 73–82. doi:10.1016/j.cedpsych.2014.12.001.

- Boté, J.J., and M. Térmens. 2019. “Reusing Data: Technical and Ethical Challenges.” DESIDOC Journal of Library & Information Technology 39 (6): 329–337. doi:10.14429/djlit.39.06.14807.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Briggs, L., and R. Daly. 2012, March 21st. “Why Internships and Placements are a Popular Route to Employment.” The Independent. 21(3), 2012.

- Bryman, A. 2006. “Integrating Quantitative and Qualitative Research: How Is It Done?” Qualitative Research 6 (1): 97–113. doi:10.1177/1468794106058877.

- CBI. 2011. The CBI Education and Skills Survey. London: CBI.

- CFE Research. 2014. “The Impact of Doctoral Careers.” Final Report 130.

- Cuyler, A. C., and A. R. Hodges. 2015. “From the Student Side of the Ivory Tower: An Empirical Study of Student Expectations of Internships in Arts and Cultural Management.” International Journal of Arts Management 17 (3): 68–79.

- Elarde, J. V., and F. F. Chong 2012. “The Pedagogical Value Of” Eduployment” Information Technology Internships in Rural Areas.” In Proceedings of the 13th annual conference on Information technology education, 189–194. doi:10.1145/2380552.2380607

- Gault, J., E. Leach, and M. Duey. 2010. “Effects of Business Internships on Job Marketability: The Employers’ Perspective.” Education & Training 52 (1): 76–88. doi:10.1108/00400911011017690.

- Glogowska, M., P. Young, and L. Lockyer. 2011. “Propriety, Process and Purpose: Considerations of the Use of the Telephone Interview Method in an Educational Research Study.” Higher Education 62 (1): 17–26. doi:10.1007/s10734-010-9362-2.

- Green, J., and N. Thorogood. 2004. Qualitative Methods for Health Research. London: Sage.

- Greene, J. C., V. J. Caracelli, and W. F. Graham. 1989. “Toward a Conceptual Framework for mixed-method Evaluation Designs.” Educational Evaluation and Policy Analysis 11 (3): 255–274. doi:10.3102/01623737011003255.

- Haasler, S. R. 2013. “Employability Skills and the Notion of ‘Self’.” International Journal of Training and Development 17 (3): 233–243. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12012.

- Hancock, S. 2019. “A Future in the Knowledge Economy? Analysing the Career Strategies of Doctoral Scientists through the Principles of Game Theory.” Higher Education 78 (1): 33–49. doi:10.1007/s10734-018-0329-z.

- Hubble, S., and P. Bolton. 2018. “Higher Education Tuition.” House of Commons Library Briefing Paper, No. 8151.

- Hurst, J. L., and L. K. Good. 2010. “A 20-year Evolution of Internships: Implications for Retail Interns, Employers and Educators.” The International Review of Retail, Distribution and Consumer Research 20 (1): 175–186. doi:10.1080/09593960903498342.

- Hynie, M., K. Jensen, M. Johnny, J. Wedlock, and D. Phipps. 2011. “Student Internships Bridge Research to Real World Problems.” Education and Training 53 (1): 45–46. doi:10.1108/00400911111102351.

- Ismail, Z. 2018. “Benefits of Internships for Interns and Host Organisations.” K4D Helpdesk Report. Birmingham UK: University of Birmingham.

- Jackson, C. 2019. Data Snapshot. Australia: Universities of Australia. https://www.universitiesaustralia.edu.au/?s=data+snapshot

- Kwok, R. 2017. “Flexible Working: Science in the Gig Economy.” Nature 550 (7676): 419–421. doi:10.1038/nj7676-419a.

- Major, L.E. 2001, 6 August. “£100K Price Tag for a PhD, Study Reveals.” The Guardian.

- McDonald, J., C. Birch, A. Hitchman, P. Fox, and C. Lido. 2010. “Developing Graduate Employability through Internships: New Evidence from a UK University.” In Proceedings of the 17th EDINEB Conference: Crossing borders in education and work-based learning. Thames Valley University, London, UK, 349–358.

- Miller, L., A. Biggart, and B. Newton. 2013. “Basic and Employability Skills.” International Journal of Training and Development 3 (17): 173–175. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12007.

- Minocha, S., D. Hristov, and M. Reynolds. 2017. “From Graduate Employability to Employment: Policy and Practice in UK Higher Education.” International Journal of Training and Development 21 (3): 235–248. doi:10.1111/ijtd.12105.

- Molla, T., and D. Cuthbert. 2015. “The Issue of Research Graduate Employability in Australia: An Analysis of the Policy Framing (1999–2013).” The Australian Educational Researcher 42 (2): 237–256. doi:10.1007/s13384-015-0171-6.

- Moreau, M. P., and C. Leathwood. 2006. “Graduates’ Employment and the Discourse of Employability: A Critical Analysis.” Journal of Education and Work 19 (4): 305–324. doi:10.1080/13639080600867083.

- Okahana, H., and T. Kinoshita. 2018. “Closing gaps in our knowledge of PhD career pathways: How well did a humanities PhD prepare them?” CGS Research in Brief.

- Park, C. 2005. “New Variant PhD: The Changing Nature of the Doctorate in the UK.” Journal of Higher Education Policy and Management 27 (2): 189–207. doi:10.1080/13600800500120068.

- Raddon, A., and J. Sung. 2009. “The career choices and impact of PhD graduates in the UK: A synthesis review, Economic and Social Research Council (ESRC) and Research Councils UK (RCUK).” University of Leicester.

- Ritchie, J., and L. Spencer. 1994. “Qualitative Data Analysis for Applied Policy Research.” In Analyzing Qualitative Data, edited by A. Bryman and R. G. Burgess, 173–194. London: Routledge.

- Robson, C., and K. McCartan. 2016. Real World Research. 4th ed. Hokoben. New Jersey: Wiley.

- Sankar, P., and N. L. Jones. 2007. Semi-structured Interviews in Bioethics Research. In Advances in bioethics: Empirical methods for bioethics: A primer, ed. L. J. Siminoff and L. A. Siminoff, 11. Oxford: Elsevier

- Schnoes, A.M., A. Caliendo, J. Morand, T. Dillinger, M. Naffziger-Hirsch, B. Moses, J.C. Gibeling, et al. 2018. “Internship Experiences Contribute to Confident Career Decision Making for Doctoral Students in the Life Sciences.” CBE—Life Sciences Education 17 (1): 1–14. doi: 10.1187/cbe.17-08-0164. PMID: 29449270; PMCID: PMC6007763.

- Sharmini, S., and R. Spronken-Smith. 2020. “The PhD–is It Out of Alignment?” Higher Education Research & Development 39 (4): 821–833. doi:10.1080/07294360.2019.1693514.

- Shoenfelt, B., J. Kottke, and N. Stone. 2012. “Master’s and Undergraduate Industrial/ Organizational Internships: Data-based Recommendations for Successful Experiences.” Teaching of Psychology 39 (2): 100–106. doi:10.1177/0098628312437724.

- Wilson, T. 2012. A Review of Business–University Collaboration. London: Department for Business, Innovation and Skills.

- Wilton, N. 2011. “Do Employability Skills Really Matter in the UK Graduate Labour Market? the Case of Business and Management Graduates.” Work, Employment and Society 25 (1): 85–100. doi:10.1177/0950017010389244.

- Young, S., J. A. Kelder, and J. Crawford. 2020. “Doctoral Employability: A Systematic Literature Review and Research Agenda.” Journal of Applied Learning & Teaching 3 (1): 1–11.