ABSTRACT

The concept of ‘professional boundaries’ – widely used in sectors where professional relationships between adults are regulated – has not commonly been drawn on in higher education (HE) to understand and denote appropriate relationships between faculty or staff and students. Nevertheless, in recent years the question of how to regulate sexual and romantic relationships between faculty/staff and students has been a developing policy concern within HE institutions internationally. In order to contribute to empirically-informed policy development in this area, this article explores students’ levels of comfort with different sexualised and non-sexualised behaviours from staff/faculty, drawing on data from 1492 students from a national survey carried out in the United Kingdom, initially published in the National Union of Students’ report Power in the Academy (2018). New analysis on this data is introduced, outlining scales of ‘personal’ and ‘sexualised’ interactions, which reveal the patterns of comfort and discomfort across different demographic groups of students, most notably women, LGBTQ+ students, and Black and Asian students. The analysis identifies areas of interaction with staff/faculty that are of concern to different groups of students, calling into question existing policy frameworks such as conflict of interest policies and varying levels of regulation for undergraduate and postgraduate students. In the light of these findings, the article makes two recommendations: first, that training on professional boundaries should be included in higher education teaching qualifications, and second, for the development of shared norms around professional boundaries within academic departments and professional societies.

Introduction

The concept of ‘professional boundaries’ denotes appropriate standards of behaviour by professionals in working with adult clients or patients in occupations such as healthcare, therapy, or social work (Cooper Citation2012). In higher education (HE), despite the existence of similar professional relationships between staff/facultyFootnote1 and students, the concept has rarely been used. Nevertheless, even while a clear conceptualisation of professional boundaries in HE remains lacking, in recent years within the context of heightened attention to sexual harassment in higher education, the question of how to regulate sexual and romantic relationships between faculty/staff and students has been a developing policy concern within HE institutions internationally, for example in the US, UK, Australia and Nigeria (see for example National Academies Citation2019). In addition to such concerns, recent changes in HE following the COVID-19 pandemic raise the question of where appropriate boundaries between staff and students lie in digital space (Page Citation2021); as Schwartz (Citation2012) has argued, an overwhelming focus on sexual and romantic relationships has obscured the more subtle, everyday boundary work that takes place in teaching and learning relationships in HE.

And yet, policy and research into preventing and responding to sexual misconduct has rarely been joined up with discussions of professional boundaries. An exception is a ‘strategic guide’ on tackling staff-student sexual misconduct in higher education published in 2022 by Universities UK, an advocacy organisation for universities in the United Kingdom, which recommends establishing clear professional boundaries between staff and students as one aspect of addressing this issue (Universities Citation2022, 14–15). However, outside of the US there exist few studies empirically exploring students’ attitudes in this area. This is important because even if staff and faculty were to argue for the right to have consensual sexual access to students, this is immaterial if students themselves are uncomfortable with such relationships. Therefore, it is necessary to understand students’ attitudes towards professional boundaries within teaching and learning relationships in HE in order to understand the learning conditions that students feel comfortable with.

This article argues for a clearer conceptualisation of professional boundaries to be applied within higher education settings. It introduces new analysis of data on students’ attitudes to professional boundaries with staff, initially published in Power in the Academy, a 2018 report from the National Union of Students Women’s Campaign in England and research and campaign organisation The 1752 Group. It outlines two new scales within this data that focus on ‘personal interactions’ and ‘sexualised interactions’ and explores patterns of comfort and discomfort with these types of interactions across different groups of students. Finally, it critically discusses how the concept of ‘professional boundaries’ can be helpful in implementing policy change in higher education institutions.

Professional boundaries within higher education

While research ethics within UK academia are under frequent discussion (House of Commons Citation2018; Universities Citation2012), the ethics of teaching and learning relationships are less often discussed. Concomitantly, there appears to be a lack of clarity around where boundaries lie in teaching and learning relationships in HE (Gerda and Volet Citation2014; Schwartz Citation2012). One exception is within higher education training for professions where boundaries are required between professional and client, such as psychology (Rosenberg and Heimberg Citation2009) and medicine (Dekker, Snoek, and Schönrock-Adema et al. Citation2013; Plaut and Baker Citation2011; Recupero, Cooney, and Rayner et al. Citation2005). This greater emphasis on professional boundaries in such disciplines appears to be due to, as Dekker et al. describe, ‘teachers play[ing] a key role in teaching professional behaviour, as they are important role models for trainee young doctors‘ (Dekker, Snoek, and Schönrock-Adema et al. Citation2013, 245), and such studies tend to cover a wider set of boundary issues than just sexualised behaviours, including exploitation, favouritism, or socialising. Such studies suggest that there is no consensus, either between staff and students, or even among students, as to where professional boundaries should, or do, lie (see for example, Dekker, Snoek, and Schönrock-Adema et al. Citation2013).

A further exception to the lack of research in this area are survey-based studies of mainly undergraduate populations in the US, where a body of literature from the 1990s and early 2000s examined faculty-student ‘dual’ or ‘multiple’ relationships in higher education. This theorisation states that the professional relationship may be at risk if the professional ‘assumes a second role with a client, becoming social worker and friend, employer, teacher, business associate, family member or sex partner’ (Kagle and Giebelhausen Citation1994, 213). These studies consistently report that students find sexual interactions with faculty inappropriate, with female students more likely to consider sexual interactions with staff inappropriate than male students (Ei and Bowen Citation2002; Holmes, Rupert, and Ross et al. Citation1999), while in another study, ‘Anglo-American’ students saw non-sexual boundary-crossing interactions as more inappropriate than Mexican American students (Owen and Zwahr-Castro Citation2007).

Qualitative studies have found ‘considerable differences’ between faculty and students, as well as between students themselves, in how participants perceived ‘dual relationships’ in academia (Kolbert, Morgan, and Brendel Citation2002, 202). There is evidence that students’ perceptions of their own relationships with staff/faculty change over time, with students perceiving sexual contact with faculty as fully consensual at the time it occurs but their perspectives on consent changing after the relationship ended, and the further they were away from the relationship (Bellas and Gossett Citation2001; Glaser and Thorpe Citation1986). More widely, small-scale qualitative and theoretical studies of doctoral supervision have explored the concept of boundaries between supervisor and student (Benmore Citation2016; Hemer, Citation2012; Hockey, Citation1994; Lee Citation1998; Manathunga, Citation2007). While Manathunga (Citation2007) argues that supervisors need to be more aware of power in the supervision relationship, the only one of these authors who links the concept of boundaries to sexual misconduct and gendered power is Lee (Citation1998), whose accounts of sexual harassment by academic supervisors bear strong similarities to a similar, more recent, study (Bull and Rye Citation2018).

Similarly, Bull and Page (Citation2021) shows the importance of gendered power within faculty/staff-student relationships, among other axes of inequality, in creating conditions where ‘grooming’ and ‘boundary-blurring’ behaviours can take place unnoticed (see also Laird and Pronin Citation2019). Blurred boundaries in the form of sexualised relationships have been argued by Srinivasan (Citation2020) to constitute a pedagogic failure even more than an ethical one. These studies suggest that the ‘conflict of interest’ policies used in many faculty-/staff–student relationship policies are insufficient because they lack any theorisation of power imbalances within the teaching and learning relationship.

Despite this relatively small body of research, there remains little work on approaches for building an ethically engaged workforce and for staff/faculty to learn how to exercise ethical decision-making around professional boundaries, as has been suggested in other sectors such as social work (Doel et al. (Citation2012). An exception is Schwartz’s edited volume on faculty perspectives on ‘boundary decisions’, which ‘aims to move beyond the attention-grabbing topic of teachers dating students’ and ‘explore the more common boundary questions that faculty confront daily: matters of availability, positionality, shared space, and self-disclosure’ (Schwartz Citation2012, 2). Similarly to Doel et al., Schwartz argues that more emphasis should be placed on staff/faculty developing a reflexive awareness around boundary/power issues and argues for broadening discussions of professional boundaries to encompass everyday actions and spaces (Schwartz Citation2012), a discussion that has become more urgent since the start of the COVID-19 pandemic.

As well as shifting between different groups of students, understandings of boundaries may also change according to the types of spaces in which teaching and learning is taking place, including online/offline. However, similarly to research on face-to-face interactions, evidence in the online context suggests a lack of consensus of where boundaries lie (Malesky and Peters Citation2011). While different to online teaching, Sugimoto, Hank, Bowman, & Pomerantz note that standards relating to social media use by faculty and staff ‘have not fully developed around the institutionalization of [new] expectations [around the public presentation of faculty members in the online space] and are being developed reactively to situations’ (Sugimoto, Hank, and Bowman et al. Citation2015, sec. 6, para 2). Similarly, in the UK context, in a pre-COVID-19 context Phippen and Bond argue that ‘many universities are unaware of, or fail to acknowledge the role of digital technologies and social media in students’ everyday lives, and there is a lack of understanding of rights, legislation and social behaviours that can place students at risk of harassment’ (Phippen and Bond Citation2019, 2). Indeed, our research on staff sexual misconduct in higher education has shown that both university email accounts and online media platforms (such as Instagram or Twitter direct messaging) can be routes for staff to groom or harass students (Bull and Rye Citation2018). It is clear that more discussion and clear policy frameworks for appropriate behaviours, interactions, and ethical principles on both online teaching platforms and social media are needed (Page Citation2021; Phippen and Bond Citation2019, 7).

However, despite these arguments, policy implementation in HE across all of these areas – online and offline – is patchy. Where policies exist, they focus on consensual sexual relationships and conflicts of interest rather than discussing professional boundaries within the context of professional ethics more widely. As Richards et al. argue in a study of consensual relationships policies in US institutions, the ambiguity of most universities positions on faculty student consensual relationships ‘fosters a sense of confusion’ (Richards, Crittenden, and Garland et al. Citation2014, 346). Similarly in the UK, a recent study of 61 policies across 25 UK higher education institutions found few or weak policies (Bull and Rye Citation2018). There is evidence more recently of HEIs moving towards stricter policies in this area (Cornell University Citation2018; University College London Citation2020). However, different standards apply for different groups of staff on campus; for some groups of non-academic faculty such as counselling staff there already exist professional codes of conduct with clearly regulated boundaries.

Therefore, having outlined above the ways in which professional boundaries are currently being understood and implemented within and outside higher education, we now introduce new analysis of data on students’ levels of comfort with different types of interaction with faculty and staff in higher education.

Methods

Participants

Data comes from the National Union of Students (NUS) study ‘Power in the academy: staff sexual misconduct in UK higher education’ (National Union of Students Citation2018). This was a partnership between the NUS Women’s campaign and The 1752 Group. The National Union of Students is an association of around 600 students’ unions, representing more than seven million students; around 95% of all students’ unions in the UK are affiliated to NUS (National Union of Students Citation2021). The survey instrument was shared with peer academic experts for comment and review, and a favourable ethical opinion was obtained from the University of Portsmouth’s Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences ethics committee. Participants were recruited primarily between November 2017 and January 2018 via email to holders of the ‘NUS Extra’ card, a widely-used discount card that is available to all members of students’ unions that are members of the NUS or via links to the survey posted on social media. Respondents were offered the chance to win one of five lots of £100. 1837 participants completed the online survey. While former students were eligible to fill out the survey, the analysis of group differences reported below draws only on data from current students (i.e. students enrolled during the academic year 2017–18). After removing former students and those who no long wished their data to be analysed there was a final sample of 1492 of which the majority were women (61%), those who had a gender that matches their gender assigned at birth (97%), were between the ages of 18–24 (61%), are heterosexual (76%), white (75%), home students (73%), studying at undergraduate level (54%) (For more demographic detail see online resource 1).

Measures

This article analyses data from one section of the survey, which comprised 11 questions on professional boundaries in higher education. This survey instrument was devised specifically for this study, drawing on Auweele et al.’s (Citation2008) study of unwanted sexual experiences among Flemish female student‐athletes. Coach–athlete relationships are a helpful model for HE in that they comprise an example of relationships between adults in a position of power with young people who may be over 18 but are in a relationship of dependence on the coach. While Auweele et al. use Likert scales asking about ‘acceptable’ or ‘unacceptable’ behaviours, we changed this wording to asking about behaviours that students were comfortable or uncomfortable with from higher education staff (see footnote for full wording of questionsFootnote2). This is because we wanted students to reflect on their own personal feelings and views, including incidents they had experienced in relation to staff/faculty. This is different to reflecting on what behaviours might be more generally acceptable for others; the term ‘acceptable’ invites a judgment of what is generally appropriate within their social setting or institution. In the survey, respondents were directed to interpret ‘staff’ broadly to include academic staff (lecturer, tutor, supervisor or other staff member involved in academic teaching or research) and non-academic staff (library staff, sports coach, residential staff, security staff, IT support staff, or others), and to reflect on behaviour that took place on as well as off campus, including at conferences, on university trips, or on fieldwork.

The key demographic variables of interest were gender (across four levels: man, woman, non-binary and prefer not to say), sexual orientation (six levels: heterosexual/straight, gay/lesbian, bisexual/bi, queer, prefer not to say, in another way), ethnicity (White, Black, Asian, Mixed, other and prefer not to say), ‘home’ (i.e. UK-domiciled) or international student (three levels: home, international and prefer not to say) and level of study (four levels: undergraduate, postgraduate taught, post graduate research and other). Trans students, identified via a question on whether their gender matches the gender assigned at birth, could not be included in the analysis below due to issues with missing data although preliminary analyses suggested that trans identity was not predictive in relation to either comfort levels with either personal or sexualised interactions.

Design and procedure

A cross-sectional online survey was used to explore students’ levels of comfort with professional boundaries. Upon clicking on the survey link, students were asked to read an online information sheet and consent form before continuing with the study. Participants then completed the survey questions at their own pace. On the final page of the survey, following best practice of surveys exploring sexual misconduct, participants were given the option of withdrawing their data from the study. Upon completion of the survey participants were invited to take part in focus groups (see National Union of Students (Citation2018) for more details of those findings).

Results

The analysis comes in two parts. First, we used exploratory factor analysis (EFA) to explore the underlying factors within the professional boundaries questionnaire and second, we used a negative binomial and multiple regression to explore demographic differences across the two factors. All analyses were conducted using R (3.5.0) and R Studio version 1.1.453.

Professional boundaries questionnaire

An initial unrotated principal axis factor analysis was run on the 11 items of the professional boundaries scale to determine the number of factors to extract. Eigen values showed that two factors had values greater than one and explained 65% of the variance, whilst the scree plot showed a clear inflexion after two factors. Velicer MAP achieves a minimum with two factors at 0.06 and the very simple structure criterion also points to a two-factor solution with a complexity score of .96. On balance, the majority of methods to determine factors indicate a two-factor solution is appropriate.

The Kaiser-Meyer-Olkin measure of sampling adequacy was .88 with each individual item greater than .82 indicating that all items have an adequate sample to be included in the factor analysis. Bartlet’s test of sphericity (χ2 (55) = 12,621, p < .001) was significant indicating the correlation matrix is not an identity matrix.

The correlation between the two factors was .55 indicating that an oblique rotation would be suitable to account for the correlation between the factors, specifically a Promax rotation was applied. In , we can see that five items appear to load on to factor one with all the items having pattern co-efficient greater than .77 and cross loadings smaller than .03. These items seem to reflect a more intimate and physical relationship (i.e. comfort engage in romantic relationship, or member of staff commenting on a students body) hence this factor is named comfort with sexualised interactions. Cronbach alpha for this factor is .94 suggesting high internal consistency across the items(Tavakol & Dennick, Citation2011). On factor two all items had pattern loadings greater than .44 and cross loadings smaller than .17 with the items reflecting more personal and social interactions (i.e. staff adding student on Facebook or meeting outside of the academic timetable) hence this factor is named as comfort with personal interactions. Internal reliability is reasonable with Cronbach alpha of .78. Communalities, the amount of variance in the item explained by the retained factors, across seven of the nine items was greater than .60 with only two items having communalities of .29 and .32. Sum scores of each of the factor were created for the demographic analysis. We choose sum scores as they preserve the underlying variation within the data and are easier to interpret than factor scores (DiStefano, Zhu, and Mîndrilǎ Citation2009).

Table 1. Comfort with staff actions: Principal axis factor analysis with Oblique (promax) rotation.

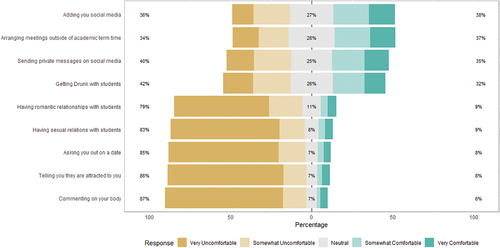

In , numbers on the left-hand column represent the percentage of respondents to the item who stated that they were either very uncomfortable or somewhat uncomfortable with the behaviour described in the statement. Numbers in the centre of the graph in grey represent the percentage of respondents who were neutral in response to this statement, and numbers on the right represent the percentage of responses who were somewhat or very comfortable with the statement. This figure shows that the top four items relating to comfort levels with personalised interaction have high levels of variability in positive and negative responses, with typically around a third of students feeling comfortable and uncomfortable in these interactions with staff. For example, 37% were either comfortable or very comfortable with meetings outside the academic timetable whilst 34% were very uncomfortable or uncomfortable. The bottom five items on all represent more sexualised interactions where the majority of respondents (>78%) tended to be either comfortable or uncomfortable with these types of relationships with university staff. Similarly for each item on this factor less than 10% of the students felt comfortable or very comfortable with staff behaviours such as commenting on a student’s body.

Analysis of group differences

There was a small number of missing responses across demographic items (as can be seen from Online resource 1). Therefore to identify the type of missing data we performed Little’s test of missing completely at random (MCAR) for each factor and the demographic predictors (gender, sexual orientation, ethnicity, home/international and level of study). Both tests were insignificant suggesting the data was missing completely at random (Comfort with sexualised interaction χ2 (29) = 26.8, p = .581; Comfort with Personalised interaction χ2 (29) = 36.1, p = .172). Both Baraldi and Enders (Citation2010) and Nassiri, Lovik, and Molenberghs et al. (Citation2018) suggest that small percentages of missing data that is MCAR can be dealt with using case-wise deletion therefore we removed 44 cases (2.94%) resulting in a final sample of 1448.

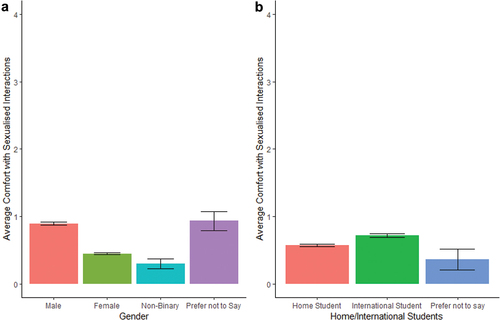

To explore how demographics impacted students’ levels of comfort with sexualised interactions towards staff we conducted a negative binomial regression (See ). The negative binomial was a substantially better fit for the data than the Poisson model (χ2 (1) = 4620.8, p < .0001) indicating that the conditional variance is greater than the conditional mean. Overall, the model had significant main effects for gender (χ2 (3) = 57.03, p < .001), and home/international students (χ2 (2) = 10.3, p < .01). The main effect of gender seemed to be driven by two significant comparisons with women being substantially more likely to report greater discomfort with sexualised interactions than men (Incident rate ratio (IRR) = 0.48, SE = 0.10, p < .001) and with non-binary students (IRR = 0.41, SE = 0.42, p < .05) also tending to feel more uncomfortable than men with sexualised interactions (see ). The main effect of home/international students can be explained by international students being more likely to give higher scores than home student indicating less discomfort towards sexualised interactions (IRR = 1.39, SE = 0.11, p < .01). There were no significant main effects for sexual orientation (χ2 (5) = 2.40, p = .792), ethnicity (χ2 (5) = 3.35, p = .647) and level of study (χ2 (3) = 4.84, p = .18).

Table 2. Negative binomial regression exploring students’ perceptions towards sexualised interactions with staff.

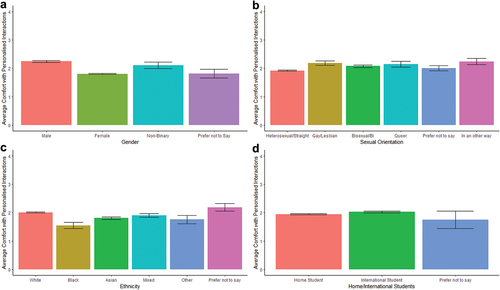

To explore how demographic group affected students’ comfort or discomfort levels, for the second underlying factor – personalised interactions with staff – a multiple regression model was conducted (See ). The multiple regression was a substantially better fit than the empty model (F (18, 1429) = 5.96, p < .001). The model accounted for 6.98% of the variability in scores with personalised interactions (R2 = .0698). The model has main effects for gender (F (3) = 22.78, p < .001), sexual orientation (F (5) = 2.75, p < .05), ethnicity (F (5) = 2.66, p < . 05) and home/international student (F (2) = 4.12, p < . 05). Women (ß = −0.23, SE = 0.22, p < .001) and those who selected ‘prefer not to say’ in relation to their gender (ß = −0.07, SE = 0.97, p < .05) were more likely to give lower scores indicating a more discomfort with personalised interactions than men (see ). Bisexual students (ß = 0.07, SE = 0.33, p < .01) had significantly higher scores than heterosexuals, indicating less discomfort with personalised interactions. International students (ß = 0.07, SE = 0.25, p < .05) compared to home students also reported less discomfort. Both Black (ß = −0.06, SE = 0.60, p < .05) and Asian (ß = −0.07, SE = 0.33, p < .01) students reported less comfort with personalised interaction than white students.

Figure 3. Average scores across each of the main effects on personalised interactions (error bars = SE).

Table 3. Multiple regression exploring the effects of demographics on students’ comfort with personalised interactions with staff.

Discussion

Overall, the analysis above shows that respondents were much less comfortable with items on the sexualised interactions scale than those on the personal intersections scale. There were significant differences in levels of comfort in relation to gender, race, sexuality, and home/international students, while perhaps surprisingly there was no difference in relation to the respondent’s level of study (i.e. postgraduate or undergraduate). Gender appeared as a main effect across both personalised and sexualised interaction with women on the whole feeling more uncomfortable than men. Non-binary respondents also felt particularly uncomfortable with sexualised interactions. While we used the term ‘uncomfortable’ rather than ‘inappropriate’, these findings seem to bear similarities to research findings from the US that students consistently find sexual interactions with faculty inappropriate, and women students more so than men students (Ei and Bowen Citation2002; Holmes, Rupert, and Ross et al. Citation1999).

It is important to highlight, therefore, that despite the differences in comfort levels across the two scales, women respondents were more uncomfortable than men with both scales, rather than only the sexualised interactions scale. This could be explained in part by findings from Bull and Page (Citation2021) who explore how staff/faculty can use boundary-blurring behaviours, such as those in the ‘personal interactions’ scale, to groom students for sexualised interactions. They describe ‘boundary-blurring’ as ‘behaviours that transgress (often tacit) professional boundaries’, and ‘grooming’ as ‘a pattern of these behaviours over time between people in positions of unequal power’ (Bull and Page Citation2021, 1). The behaviours in the personal interactions scale such as private messaging on social media or arranging meetings outside the academic timetable could therefore be interpreted by women as contributing to such boundary-blurring.

More generally, as Vera-Gray outlines (Vera-Gray Citation2016), women are socialised to be alert to higher levels of ‘intrusion’ from men. Vera-Gray focuses on stranger intrusions in public spaces, ranging from ordinary interruptions such as exhortations to smile, to being stared at, to insults and threats, describing how these ‘intrusions’ did not necessarily constitute the definition of sexual harassment but still had affected women’s sense of bodily autonomy and agency in public spaces. Similarly, the lower levels of comfort with the ‘personal interactions’ scale that women report in this study may reflect a lifetime’s experience of being alert to the threat of ‘intrusions’, as well as a much higher likelihood of having been victimised (Ministry of Justice, Home Office, & Office for National Statistics Citation2013). As our study finds, these points are also relevant to queer and non-binary people.

As well as gendered patterns, differences across racialised groups were also statistically significant in relation to comfort with personal interactions. Both Black and Asian students reported feeling more uncomfortable with personalised interactions than white students. While there are also likely to be differences within each of these racialised groups that this study does not reveal, these findings need to be contextualised within wider research on the racial discrimination and inequalities faced by Black and minority ethnic academic students and staff in UK HE, as well as elsewhere (Bhopal Citation2015; Rollock Citation2019).

Sexuality also produced significant differences in levels of comfort across groups. Most notably, heterosexual participants were less comfortable with personal interactions than bisexual participants. This is perhaps surprising as it is contrasts with findings from this sample that non-heterosexual participants were much more likely to be subject to sexual misconduct (National Union of Students Citation2018, 21), a result that is consistent across other studies (Cantor, Fisher, and Chibnall et al. Citation2019: iv; Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2017, 40), amidst ongoing exclusion of sexual and gender-diverse students (Ferfolja, Asquith, and Hanckel et al. Citation2020). Overall, being more likely to be subjected to sexual misconduct does not correlate, for this group, with less comfort around boundary-blurring behaviours in the form of personal interactions. This point deserves further investigation. Furthermore, policies that aim for greater transparency and clearer boundaries around sexualised relationshipsfor example, consensual relationship policies that require staff/faculty and students to disclose sexual and romantic relationships, may be of concern to non-heterosexual participants who fear being ‘outed’ if they disclose such relationships (even if confidentially). These findings, therefore, point towards consultation being needed with LGBTQ+ people around devising and implementing professional boundaries.

By contrast with these patterns around gender, race, and sexuality, it is notable that there are no differences in levels of comfort across either scale between postgraduate and undergraduate students. Indeed, levels of comfort with sexualised interactions are identical across the two groups, despite the fact that postgraduate students are more likely to be subject to staff sexual misconduct (Australian Human Rights Commission Citation2017; Cantor, Fisher, and Chibnall et al. Citation2019; National Union of Students Citation2018). This is also notable as this survey purposively recruited a large sample of current postgraduate students (n = 636) compared to undergraduate students (n = 832). This point has important policy implications, suggesting that having different levels of regulation for sexual/romantic relationships according to level of study, whereby sexual and romantic relationships with staff are prohibited for undergraduates but not for postgraduate students (see for example Cornell University Citation2018) is not justified by student attitudes.

Conclusion

The analysis in this article suggests that it is possible to conceptualise professional boundaries between staff/faculty and students across two scales: personal interactions and sexualised interactions. We suggest that these two scales can be used as a starting point for understanding and clarifying professional boundaries in higher education. The data shows that students in this sample were much less comfortable with sexualised interactions than personal interactions. However, despite students being on the whole neither comfortable nor uncomfortable with personal interactions, this does not mean that HEIs should not pay attention to boundaries around personal interactions. While many of these ‘personal interactions’ – in particular relating to boundaries on social media – found students evenly divided or neutral in their levels of comfort, these patterns are gendered and racialised with more women and racialised minorities finding such interactions uncomfortable. From the data in this study, it is not possible to tell why these differences exist, but they suggest that clarifying boundaries around personal interactions might be helpful in building trust and make ‘boundary-blurring behaviours’ (Bull and Page Citation2021) more visible where they occur. Our findings, therefore, show that in order to create an inclusive teaching and learning environment, ‘personal’ as well as ‘sexualised interactions’ need to be clearly boundaried.

Overall, these findings also show the importance of examining professional boundaries beyond sexualised interactions (Schwartz Citation2012), and the necessity for understanding how these ‘personal’ interactions shape students’ interactions with academic staff. The gendered and racialised patterns in this study and similar studies suggest that the issue of professional boundaries between staff/faculty and students has implications for the provision of equal access to education for racialised minorities, women, and queer/non-binary students, as enshrined in equality law such as the UK’s Equality Act. Clarifying professional boundaries between staff and students can be one facet of creating conditions in which all students feel comfortable and safe to learn.

There are some limitations to the study methods. Firstly, while the survey respondents captured responses from different demographic groups of UK students, it is not a representative study. Secondly, we did not distinguish between academic and non-academic staff, an issue that should be addressed in future studies. Finally, the data were gathered in late 2017-early 2018 and therefore does not capture changes that may have occurred since then, for example in relation to changes to teaching and learning in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, or ongoing changes following the MeToo movement. Nevertheless, we suggest that the findings are robust enough to warrant further investigation by institutions of their own student populations in relation to the issues raised.

Indeed, given the importance of shared norms around professional boundaries within organisations as a mechanism for preventing sexual harassment and violence (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Citation2018), it is surprising that more systematic research and policy attention has not been paid to this issue. The absence of shared professional standards can go some way to explaining the high levels of sexual misconduct in HEIs, as well as bullying and harassment in academia more generally (UK Research & Innovation Citation2019), although clearly wider conditions, including ongoing marketisation and the entrenched gendered and racialised power disparities in HE are also crucial factors (National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine Citation2018, 135; UK Research & Innovation Citation2019, 16).

In relation to policy and practice, we suggest that HEIs move away from using a ‘conflict of interest’ rationale, which draws on a ‘dual relationships’ theorisation towards understanding ‘professional boundaries’ as part of a wider set of professional ethics which lays the responsibility and the power with the professional to uphold such boundaries. It might seem contradictory to suggest both that more robust professional boundaries are needed, but also that more emphasis should be placed on staff/faculty developing a reflexive awareness around boundary/power issues (Schwartz Citation2012). This reflexive awareness, similarly to Doel et al.’s recommendation of building an ethically sensitive workforce in social work (2012), suggests that it is not possible to make determinations in appropriate boundaries for every possible instance in advance. Indeed, it may be difficult to hold such a balance in practice. Nevertheless, if staff/faculty learn to ask themselves, ‘does this serve the student’s learning?’ when making boundary decisions, and can make this reasoning clear to students, then this goes some way to overcoming this contradiction. We are also aware, of course, that some perpetrators of sexual misconduct or other abuses of power will find ways to use any such system to their advantage, and that implementing clearer professional boundaries is only one aspect of a robust prevention and response mechanism for addressing sexual misconduct.

In summary, then, we suggest two recommendations that stem from this study. First, reflexive understanding of professional boundaries should be included in training for staff teaching in higher education. For example, in the UK such training should be included as part of Postgraduate Certificate in HE courses. As noted above in relation to social work, rather than ‘ever-increasing bullet points of advice and prescription’, training can ‘advance a notion of ethical engagement in which professionals exercise their ethical senses through regular discussion of professional boundary dilemmas’ (Doel, Allmark, and Conway et al. Citation2010, 1867). Second, such training needs to take place in conjunction with wider development of shared norms within academic institutions/departments and professional societies. Within departments or subject areas, facilitated discussions should be held to formulate shared boundaries that are appropriate to their environment. The findings reported in this article could be a starting point for such discussions. In initial stages, holding such discussions separately for staff and student groups would allow for points of consensus and difference to emerge. While some areas of professional boundary ‘dilemmas’ may be uncomfortable for staff to discuss with peers, there exist less sensitive examples that can help develop ‘ethical engagement’ such as sharing mobile phone numbers with students; having academic meetings off campus or in the staff member’s home; or going to the pub with students.

This work also needs to happen internationally, within professional societies, so that shared norms within disciplines can be formulated to create consistency for students and staff. To this end, professional societies could consider convening facilitated discussions on professional boundaries at conferences. Within HEIs and professional societies, once such discussions and surveys have taken place, agreed statements on boundaries need to be publicised at induction, lectures, seminars and via posters and mission statements, and community ownership of them needs to be established, for example via bystander training. These shared understandings of norms can then be embedded within pedagogy and pastoral relationships from induction to graduation. Such shared understandings will go some way towards preventing sexual misconduct and other abuses of power being perpetrated by staff and will facilitate routes for students and staff/faculty to challenge unacceptable or inappropriate behaviours. Most importantly, such changes will then allow all students to benefit equally from the teaching and learning that is available at their institution.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Notes

1. In the US the term ‘faculty’ is used to refer to those employed in academic roles in higher education, and ‘staff’ refers to those in professional services or student support roles. By contrast, in the UK, the term ‘staff’ is used to refer to both groups, which are then distinguished by reference to ‘academic staff’ or ‘professional staff’. In this article, we use the term ‘faculty/staff’ to indicate that we are talking about both groups.

2. The survey questions were worded as follows: On a scale of 1–5, with 1 being ‘very comfortable’, and 5 being ‘very uncomfortable’, please indicate how comfortable you are with a member of staff doing each of the following.

1. Getting drunk with you or other students

2. Inviting you for dinner on your own

3. Adding you on Facebook

4. Communicating with you via private messages on Facebook or Whatsapp

5. Asking you out on a date

6. Telling you they are attracted to you

7. Commenting on your body

8. Arranging meetings with you at times that are outside the academic timetable

9. Arranging supervision/tutorial meetings at their house

10. Having sexual relations with students

11. Having romantic relationships with students

Our thanks to Vanita Sundaram for suggesting this edit from ‘(un)acceptable’ to (un)comfortable’.

References

- Australian Human Rights Commission. 2017. “Change the Course: National Report on Sexual Assault and Sexual Harassment at Australian Universities.” Australian Human Rights Commission. https://www.humanrights.gov.au/our-work/sex-discrimination/publications/change-course-national-report-sexual-assault-and-sexual

- Auweele, Y. V., J. Opdenacker, T. Vertommen, F. Boen, L. Van Niekerk, K. De Martelaer, and B. De Cuyper. 2008. “Unwanted Sexual Experiences in Sport: Perceptions and Reported Prevalence among Flemish Female Student‐athletes.” International Journal of Sport and Exercise Psychology 6 (4): 354–365. https://doi.org/10.1080/1612197X.2008.9671879

- Baraldi, A. N., and C. K. Enders. 2010. “An Introduction to Modern Missing Data Analyses.” Journal of School Psychology 48 (1): 5–37. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jsp.2009.10.001

- Bellas, M. L., and J. L. Gossett. 2001. “Love or the ‘Lecherous Professor’: Consensual Sexual Relationships between Professors and Students.” The Sociological Quarterly 42 (4): 529–558. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1533-8525.2001.tb01779.x

- Benmore, A. 2016. “Boundary Management in Doctoral Supervision: How Supervisors Negotiate Roles and Role Transitions Throughout the Supervisory Journey.” Studies in Higher Education 41 (7): 1251–1264. https://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2014.967203

- Bhopal, K. 2015. The Experiences of Black and Minority Ethnic Academics: A Comparative Study of the Unequal Academy. London: Routledge.

- Bull, Anna, and Tiffany Page. 2021. “Students’ Accounts of Grooming and Boundary-Blurring Behaviours by Academic Staff in UK Higher Education.” Gender and Education, February. 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540253.2021.1884199

- Bull, Anna, and Rachel Rye. 2018. “‘Silencing Students: Institutional Responses to Staff Sexual Misconduct in Higher Education’. The 1752 Group/University of Portsmouth.” https://1752group.files.wordpress.com/2018/09/silencing-students_the-1752-group.pdf

- Cantor, D., B. Fisher, S. Chibnall, S. Harps, R. Townsend, G. Thomas, H. Lee, V. Kranz, R. Herbison, and K. Madden 2019. “Report on the AAU Campus Climate Survey on Sexual Assault and Misconduct.” Association of American Universities. https://www.aau.edu/sites/default/files/AAU-Files/Key-Issues/Campus-Safety/FULL_2019_Campus_Climate_Survey.pdf

- Cooper, F. 2012. Professional Boundaries in Social Work and Social Care: A Practical Guide to Understanding, Maintaining and Managing Your Professional Boundaries. London: Jessica Kingsley Publishers.

- Cornell University. 2018. “Consensual Relationships Policy Committee.” September 3. http://theuniversityfaculty.cornell.edu/dean/report-archive/consensual-relationships-policy-committee/

- Dekker, H., J. W. Snoek, J. Schönrock-Adema, T. van der Molen, and J. Cohen-Schotanus. 2013. “Medical Students’ and Teachers’ Perceptions of Sexual Misconduct in the Student–Teacher Relationship.” Perspectives on Medical Education 2 (5–6): 276–289. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40037-013-0091-y

- DiStefano, C., M. Zhu, and D. Mîndrilǎ. 2009. “Understanding and Using Factor Scores: Considerations for the Applied Researcher.” Practical Assessment, Research and Evaluation 14 (20): 1–11.

- Doel, M. 2012. Professional Boundaries Research Report. Centre for Health and Social Care Research, Sheffield Hallam University. http://shura.shu.ac.uk/1759/

- Doel, M., P. Allmark, P. Conway, M. Cowburn, M. Flynn, P. Nelson, and A. Tod. 2010. “Professional Boundaries: Crossing a Line or Entering the Shadows?” The British Journal of Social Work 40 (6): 1866. https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcp106

- Ei, S., and A. Bowen. 2002. “College Students’ Perceptions of Student-Instructor Relationships.” Ethics & Behavior 12 (2): 177–190. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327019EB1202_5

- Ferfolja, T., N. Asquith, B. Hanckel, and B. Brady. 2020. “In/visibility on Campus? Gender and Sexuality Diversity in Tertiary Institutions.” Higher Education 80 (5): 933–947. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-020-00526-1

- Gerda, Hagenauer, and Simone E. Volet. 2014. “Teacher–Student Relationship at University: An Important yet under-Researched Field.” Oxford Review of Education 40 (3): 370–388. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2014.921613

- Glaser, R. D., and J. S. Thorpe. 1986. “Unethical Intimacy: A Survey of Sexual Contact and Advances between Psychology Educators and Female Graduate Students.” American Psychologist 41 (1): 43–51. https://doi.org/10.1037/0003-066X.41.1.43

- Hemer, S. R. 2012. “Informality, Power and Relationships in Postgraduate Supervision: Supervising PhD Candidates Over Coffee.” Higher Education Research & Development 31 (6): 827–839. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2012.674011

- Hockey, J. 1994. “Establishing Boundaries: Problems and Solutions in Managing the PhD Supervisor’s Role.” Cambridge Journal of Education 24 (2): 293–305. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305764940240211

- Holmes, D. L., P. A. Rupert, S. A. Ross, and W. E. Shapera. 1999. “Student Perceptions of Dual Relationships between Faculty and Students.” Ethics & Behavior 9 (2): 79–106. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15327019eb0902_1

- House of Commons. 2018. “Report on Research Integrity.” Science and Technology Committee.

- Kagle, J., and P. N. Giebelhausen. 1994. “Dual Relationships and Professional Boundaries.” Social Work 39 (2): 213–220.

- Kolbert, J. B., B. Morgan, and J. M. Brendel. 2002. “Faculty and Student Perceptions of Dual Relationships within Counselor Education: A Qualitative Analysis.” Counselor Education and Supervision 41 (3): 193–206. https://doi.org/10.1002/j.1556-6978.2002.tb01283.x

- Laird, A. A., and E. Pronin. 2019.“Professors’ Romantic Advances Undermine Students’ Academic Interest, Confidence, and Identification.” Sex Roles, January. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-019-01093-1

- Lee, D. 1998. “Sexual Harassment in PhD Supervision.” Gender and Education 10 (3): 299–312. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540259820916

- Malesky, L. A., and C. Peters. 2011. “Defining Appropriate Professional Behavior for Faculty and University Students on Social Networking Websites.” Higher Education 63 (1): 135–151. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-011-9451-x

- Manathunga, C. 2007. “Supervision as Mentoring: The Role of Power and Boundary Crossing.” Studies in Continuing Education 29 (2): 207–221. https://doi.org/10.1080/01580370701424650

- Ministry of Justice, Home Office, & Office for National Statistics. 2013. “An Overview of Sexual Offending in England & Wales.” http://www.ons.gov.uk/ons/rel/crime-stats/an-overview-of-sexual-offending-in-england—wales/december-2012/index.html

- Nassiri, V., A. Lovik, G. Molenberghs, and G. Verbeke. 2018. “On Using Multiple Imputation for Exploratory Factor Analysis.” Behavior Research Methods 50 (2): 501–517. https://doi.org/10.3758/s13428-017-1013-4

- National Academies. 2019. “Action Collaborative on Preventing Sexual Harassment in Higher Education—2019 Public Summit.” https://www.nationalacademies.org/event/11-19-2019/action-collaborative-on-preventing-sexual-harassment-in-higher-education-2019-public-summit

- National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine. 2018. Sexual Harassment of Women: Climate, Culture, and Consequences in Academic Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. Washington: National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. https://doi.org/10.17226/24994

- National Union of Students. 2018. “Power in the Academy: Staff Sexual Misconduct in UK Higher Education.” April 4. https://1752group.files.wordpress.com/2021/09/4f9f6-nus_staff-student_misconduct_report.pdf

- National Union of Students, 2021. “Membership of NUS.” https://www.nusconnect.org.uk/nus-uk/who-we-are/membership-of-nus

- Owen, P. R., and J. Zwahr-Castro. 2007. “Boundary Issues in Academia: Student Perceptions of Faculty—Student Boundary Crossings.” Ethics & Behavior 17 (2): 117–129. https://doi.org/10.1080/10508420701378065

- Page, Tiffany. 2021. “Harassment at Home.” Research Professional News (blog). 21 March. https://www.researchprofessionalnews.com/rr-he-views-2021-3-harassment-at-home/

- Phippen, A., and E. Bond. 2019. Higher Education Online Safeguarding Self-Review Tool. Ipswich: University of Suffolk. https://www.uos.ac.uk/sites/www.uos.ac.uk/files/Higher-Education-Online-Safeguarding-Self-Review-Tool%202019.pdf

- Plaut, S. M., and D. Baker. 2011. “Teacher-Student Relationships in Medical Education: Boundary Considerations.” Medical Teacher 33 (10): 828–833. https://doi.org/10.3109/0142159X.2010.541536

- Recupero, P. R., M. C. Cooney, C. Rayner, A. M. Heru, and M. Price. 2005. “Supervisor-trainee Relationship Boundaries in Medical Education.” Medical Teacher 27 (6): 484–488. https://doi.org/10.1080/01421590500129167

- Richards, T. N., C. Crittenden, T. S. Garland, and K. McGuffee. 2014. “An Exploration of Policies Governing Faculty-to-Student Consensual Sexual Relationships on University Campuses: Current Strategies and Future Directions.” Journal of College Student Development 55 (4): 337–352. https://doi.org/10.1353/csd.2014.0043

- Rollock, N. 2019. Staying Power: The Career Experiences and Strategies of UK Black Female Professors. London: Universities and Colleges Union. https://www.ucu.org.uk/media/10075/Staying-Power/pdf/UCU_Rollock_February_2019.pdf

- Rosenberg, A., and R. G. Heimberg. 2009. “Ethical Issues in Mentoring Doctoral Students in Clinical Psychology.” Cognitive and Behavioral Practice 16 (January): 181–190. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.09.008

- Schwartz, H. L. 2012. Interpersonal Boundaries in Teaching and Learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning 131. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons.

- Srinivasan, A. 2020. “Sex as a Pedagogical Failure.” Yale Law Journal 129 (4): 924–1275.

- Sugimoto, C., C. Hank, T. Bowman, and J. Pomerantz. 2015. “Friend or Faculty: Social Networking Sites, Dual Relationships, and Context Collapse in Higher Education.” First Monday. 20(3). http://firstmonday.org/ojs/index.php/fm/article/view/5387

- Tavakol, M., and R. Dennick. 2011. “Making Sense of Cronbach's Alpha.” International Journal of Medical Education 2: 53–55. http://doi.org/10.5116/ijme.4dfb.8dfd

- UK Research & Innovation. 2019. “Bullying and Harassment in Research and Innovation Environments: An Evidence Review.” https://www.ukri.org/files/about/policy/edi/ukri-bullying-and-harassment-evidence-review-pdf/

- Universities, UK. 2012. “The Concordat to Support Research Integrity.” http://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/policy-and-analysis/reports/Documents/2012/the-concordat-to-support-research-integrity.pdf

- Universities, UK. 2022. “Changing the Culture: Tackling staff-to-student Sexual Misconduct. Strategic Guide for Universities.” https://www.universitiesuk.ac.uk/sites/default/files/field/downloads/2022-02/staff-to-student-misconduct-strategic-guide-28-02-22_1.pdf

- University College London. 2020. Personal Relationships Policy. London: University College London Human Resources. https://www.ucl.ac.uk/human-resources/personal-relationships-policy

- Vera-Gray, F. 2016. Men’s Intrusion, Women’s Embodiment: A Critical Analysis of Street Harassment. London: Routledge.