ABSTRACT

This scoping review examines the literature on teaching Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in Initial Teacher Education (ITE) programmes. The study explores how these programmes integrate Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into their curriculum and pedagogy to prepare teachers to work with Indigenous students and communities. The review identifies empirical studies focusing on the experiences of ITE students, faculty, and Indigenous knowledge keepers, highlighting common themes and best practices. The findings suggest that while many ITE programmes have incorporated Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into their curriculum, there is a need for greater attention to the pedagogical approaches used to teach this knowledge. There is also a need for programmes to build stronger relationships with Indigenous communities and to ensure that Indigenous knowledge is taught by teachers/educators who have received some training in consultations with the Indigenous knowledge keepers. The study highlights the importance of ongoing reflection and evaluation of ITE programmes to ensure that they are preparing the preservice teachers confident enough to embed Indigenous content in their teaching and, at the same time, meet the needs of Indigenous students and communities.

Introduction

Indigenous knowledge (IK) refers to the traditional knowledge systems, practices, and beliefs passed down from generation to generation within Indigenous communities. IK is a critical source of information that informs how Indigenous communities interact with their environment, and it plays a crucial role in promoting sustainable development and cultural diversity. There is growing recognition of the importance of incorporating Indigenous knowledge into Initial Teacher Education (ITE) programmes to address Indigenous students’ unique cultural and educational needs (Berryman et al. Citation2019; De Santolo, Fogarty, and Nakata Citation2016; Kovach Citation2010; Walter Citation2013). This paper provides a background on why Indigenous knowledge is taught in ITE, an overview and argument for the need for a systematic literature review, and an understanding of key terms and constructs such as Indigenous education and perspective and ITE.

Indigenous students face unique cultural and educational challenges that require specialised attention (Battiste, Bell, and Findlay Citation2002). Traditional Indigenous ways of learning often differ significantly from mainstream educational practices, leading to a disconnect between Indigenous students and the education system (Kovach Citation2010). Additionally, Indigenous students often suffer from the negative effects of colonisation, including cultural trauma, loss of language and identity, and social and economic disadvantage (Tuck and Yang Citation2012).

Incorporating Indigenous knowledge into ITE programmes is a way to address these issues by preparing teachers to work effectively with Indigenous students and communities. It involves integrating Indigenous perspectives and knowledge into the curriculum, creating a learning environment that respects and values Indigenous culture and ways of knowing, and providing teachers with the skills and knowledge to work collaboratively with Indigenous communities.

While there is growing recognition of the importance of incorporating Indigenous knowledge into ITE programmes, there is still a lack of understanding about how best to do this effectively. The literature on Indigenous education is vast and complex, and there is a need for a systematic review of the literature to provide a comprehensive and critical analysis of the existing research (Battiste, Bell, and Findlay Citation2002; Chilisa Citation2012; Nakata Citation2007; Smith Citation2021).

A scoping literature review is a rigorous and transparent process of reviewing and synthesising the available literature on a particular topic. It involves identifying and selecting relevant studies, assessing their quality, and synthesising the findings to provide a comprehensive and critical literature analysis. A scoping literature review on incorporating Indigenous knowledge into ITE programmes would be valuable for several reasons. Firstly, it would provide a comprehensive overview of the existing research on the topic, including the different approaches, methodologies, and findings. This would enable researchers, policymakers, and educators to better understand the issues and challenges of incorporating Indigenous knowledge into ITE programmes and identify areas for further research. Secondly, a scoping literature review would enable the identification of best practices and effective strategies for incorporating Indigenous knowledge into ITE programmes. This would be valuable for ITE providers, policymakers, and educators seeking to develop or improve their programmes to better meet the needs of Indigenous students and communities. Finally, a scoping literature review would provide a critical analysis and an understanding of the breadth and depth of available literature, identify research gaps and areas for future research, and inform the development of research questions and study designs (Levac, Colquhoun, and O’Brien Citation2010). For example, Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) argued that scoping reviews help identify key concepts and evidence gaps in the literature, while Levac et al. (Citation2010) suggested that scoping reviews can help researchers to clarify the scope of a research question and determine the need for a full systematic review. Therefore, scoping reviews can be a valuable tool for researchers who wish to identify and prioritise research questions and gaps in the literature. This would enable researchers, policymakers, and educators to identify gaps in the literature and areas for further research and to develop a more nuanced understanding of the challenges and opportunities involved in incorporating Indigenous knowledge into ITE programmes.

Position of the authors

In writing this paper, our positionality is significant. We are both PST educators in two Australian universities with substantial experience in developing and teaching IK subjects that are offered at both universities. Our scholarly exploration, rooted in our roles as university lecturers and proponents of holistic education, underscores the value of continuous self-reflection and evaluation within ITE programmes. We underscore the imperative of nurturing pre-service teachers who are not only proficient in incorporating Indigenous content within their instruction but are also equipped to address the distinct needs of Indigenous students and communities. Through this scoping review, we endeavour to contribute to the ongoing dialogue on effective teacher preparation and to advocate for pedagogical practices that foster a more inclusive and culturally adept educational landscape.

Key terms/constructs

In this paper, Indigenous education refers to education informed by Indigenous perspectives and knowledge systems. It involves creating a learning environment that respects and values Indigenous culture and ways of knowing and recognises Indigenous students’ unique cultural and educational needs (Brayboy and Maughan Citation2009). Indigenous perspective refers to the cultural, historical, and social perspectives of Indigenous communities. It involves recognising and valuing Indigenous ways of knowing, understanding, and acknowledging Indigenous people’s unique perspectives and experiences (Battiste, Bell, and Findlay Citation2002). Initial Teacher Education (ITE) refers to the formal training that individuals undertake to become teachers. ITE programmes can vary in length, content, and structure, but they typically include a combination of theoretical coursework and practical placements in schools. In this paper, individuals undertaking the ITE are referred to as pre-service teachers (PSTs).

Methods

We utilised the framework by Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005) and were guided by Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses extension for Scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR) (Tricco et al. Citation2018). Following Arksey and O’Malley (Citation2005), the following procedures were taken: (1) identifying the research question; (2) identifying relevant studies; (3) selecting the studies; (4) charting the data; and (5) collating, summarising, and reporting the results.

Identifying the research question

In this review, we attempt to provide an overview of the current research on teaching Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in initial teacher education, how it is conceptualised and taught, its effectiveness, and associated issues and challenges, and considering different geographical and cultural contexts. To achieve this, we reviewed the literature related to the topic and documented these to respond to the following research questions:

How do initial teacher education programmes help teachers develop the skills and knowledge to embed Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in their future teaching?

What is pre-service teachers’ experience learning Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in initial teacher education programmes?

How equipped are pre-service teachers to embed Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in their teaching?

Identifying relevant studies

The Participants, Concept, and Context (PCC) framework were used to inform the search strategy on pre-service teachers, the teaching of Indigenous education, and initial teacher education, respectively (University of South Australia Citation2022), and a librarian was consulted to identify the search terms (Peters et al. Citation2015). The search terms were (pre-service teacher*), AND (Indigenous knowledge* OR Indigenous perspective*) AND teacher education*.

The search was conducted across four databases: ProQuest, ERIC, Web of Science, and A+ Education. The search was also limited to peer-reviewed articles published in English from 2000 to ensure the context remained current and relevant. All searches were concluded on 20 March 2023, and 153 articles were identified for the scoping review.

Selecting the studies

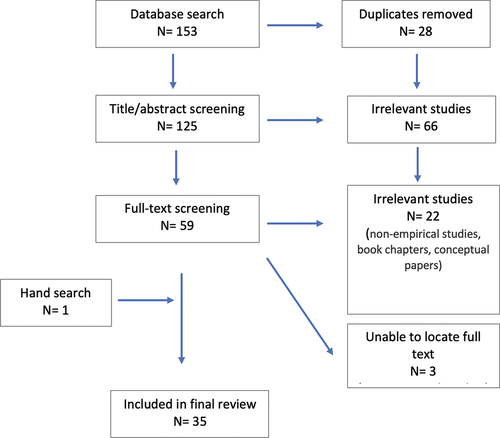

Following the removal of duplicates, the titles and abstracts of all 125 articles were screened by both authors against the inclusion and exclusion criteria () to determine their eligibility for full-text review. To qualify for inclusion in the study, the term ‘Indigenous’ must be mentioned in the title or abstract. Following title and abstract screening, 59 articles were accepted for full-text review. Based on the focus of the research question, only articles that reported empirical research and dealt explicitly with the teaching of Indigenous knowledge and perspective in initial teacher education are included. To ensure the inclusion of scholarly research, only peer-reviewed journal articles were included. Due to the researchers’ language proficiency, only articles published in English were included in this review.

Table 1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

To provide a good overview of the research in the field and to ensure that the studies were sufficiently current to reflect the topic understudy, the search was limited to papers published from 1 January 2000. At this point, 34 papers were found to meet the inclusion criteria. Most papers excluded during this stage did not include empirical research and were either book chapters or conceptual discussion papers. Upon completing the database search, a reference list search was carried out on all the relevant articles. This manual search process generated one article. The final scoping review included 31 articles. An overview of this process is provided in . A critical appraisal of the full-text articles that were included in this study was not conducted for this scoping review due to the nature of the review question, which was intended to provide an overview of studies on the teaching of Indigenous education and perspectives regardless of methodological quality or risk of bias (Tricco et al. Citation2018).

Charting the data

The articles were downloaded and added to Endnote. We charted each article by entering its details into a table (see ). These included: (1) author/s, (2) year of publication; (3) journal, (4) country where the study was conducted, (5) sample size, and (6) data collection method. An overview of the studies included in this scoping review is presented in the next section.

Table 2. Articles included in the review (in chronological order).

Overview of studies

Year of publication

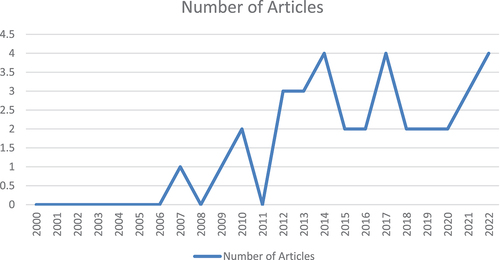

Our search for studies between 2000 and 2022 revealed that research on teaching Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in initial teacher education is limited. The earliest relevant article to be included in this review was published in 2007 (Tanaka et al. Citation2007). Since then, there has been a generally increasing trend in the number of papers published, with an average of 2.8 papers published annually in the last ten years between 2013 and 2022. The highest number was in 2014, 2017 and 2022, with four studies published each year on teaching Indigenous education and perspectives in initial teacher education. The distribution of studies across the years is shown in .

Country of studies

The 35 studies in this were distributed across seven countries. Most of these studies were conducted in Australia (n = 20) and Canada (n = 8). This is followed by New Zealand and the U.S.A. with two studies each.

Journals

The 35 articles were published in 26 journals that focused on education in general, teaching, teacher education, and Indigenous education. The Australian Journal of Indigenous Education contained the most articles (n = 8). This is followed by the Australian and International Journal of Rural Education (n = 2), Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education (n = 2), and Teaching Education (n = 2).

Participants

The studies predominantly collected data from PSTs only (n = 26). A few studies collected data from teacher educators only (n = 4), two studies collected data from both pre-service teachers and teacher educators (n = 3), and another two studies collected data from PSTs and the Aboriginal Elders and community members (n = 2).

Methodological approaches

Most of the studies employed a qualitative approach (n = 21) using data gathered from individual and focused group interviews, reflection journals and, in some cases, observation and document analysis. The others are mixed-method studies (n = 14) using a combination of data gathered from surveys, interviews, and reflection journals. The sample size in these studies varied considerably from 2 for small-scale qualitative studies to 844 participants for surveys.

Substantive findings

To ensure rigour in our analysis of PSTs’ experiences of learning Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in ITE, both authors individually analysed and coded three selected sample articles against the research questions. We then came together to compare our codes, agree on our interpretations, and arrive at a set of agreed codes. Each author then coded an equal number of remaining articles before coming together again to compare, contrast and agree on our codes and then cluster them into themes that relate to our research questions. The themes were then refined through an iterative process of elaboration, collapsing, regrouping, and clarification of their meanings (Miles, Huberman, and Saldaña Citation2020). In reviewing these studies against our research questions, we found several recurring themes that emerge that relate to the teaching of Indigenous knowledge and perspectives of initial teacher education. The next section presents the substantive findings of our research questions and the themes that emerged.

Our first research question was, ‘How do initial teacher education programmes help teachers develop the skills and knowledge to embed Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in their future teaching?’ Our review indicated that the vast majority of the universities did this through Indigenous courses or units of study within the initial education programme (McInnes Citation2017; Oskineegish and Berger Citation2021; Riley et al. Citation2022) that includes lectures, tutorials, and case studies and readings to facilitate PSTs’ reflection (Pridham et al. Citation2015; Taylor Citation2014) and develop PSTs’ cultural competence around Indigenous education. These courses are generally conceptualised as knowledge, skills, and disposition with respect to Indigenous people (McInnes Citation2017). They commonly include teaching Indigenous history, culture, perspectives, and protocols (Harrison and Murray Citation2012). A key idea in these courses is to blend Indigenous epistemology and pedagogy with Eurocentric epistemology and pedagogy to develop an innovative and ethical teaching approach (Farrell and Waatainen Citation2021). Often PSTs are guided by teacher educators to move out of their comfort zone and Western-centric way of thinking and to reconceptualise new knowledge from Indigenous perspectives (Tanaka et al. Citation2007), to question the western systems of creating, producing and valuing knowledge (Brayboy and Maughn Citation2009), and to explore educational strategies and culturally-responsive pedagogies that encourage the inculcation and an appreciation of Indigenous knowledge and culture, and to maximise learning outcomes for Indigenous and non-Indigenous learners (Pridham et al. Citation2015). These courses may also include service-learning (Lavery, Cain, and Hampton Citation2014; Peralta et al. Citation2016), field trips (Mudaly Citation2018), and placement in schools in the Indigenous community where PSTs have the opportunities to build relationships with Indigenous children, and talk to Elders and other members of the community (Bennet and Lancaster Citation2012; Bennet and Moriarty Citation2015) and engage in place-based teaching ‘on country’ (Van Gelderen Citation2017). These collaborative approaches, supported by actively modelling the processes of local Aboriginal consultation and collaboration, are said to help address students’ lack of engagement with the subject matter of Indigenous education (Morgan and Golding Citation2010). Such partnerships also encourage ‘two-way’ pedagogy whereby the pre-service teachers, their lecturers, and the local Aboriginal consultants engage in epistemological dialogue and exchange (Van Gelderen Citation2017).

Some universities have also initiated a series of dedicated Indigenous Educations workshops that extended local Aboriginal experts’ presentations in schools and teachers’ pedagogical practices to provide PSTs with skills and knowledge (Gorecki and Doyle-Jones Citation2021; Mashford-Pringle and Nardozi Citation2013; Weuffen, Cahir, and Pickford Citation2017). Yet, others have extended the approach by embedding Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in the instructional design of PSTs’ teaching subjects (Monk, Riley, and Van Issum Citation2022; Morales Citation2017; Tanaka et al. Citation2007).

Our second research question was, “What is pre-service teachers’ experience learning Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in initial teacher education programmes? Students, in general, entered the units with positive attitudes towards Indigenous peoples and knowledges and found value in their learning (Macdonald et al. Citation2022). For many PSTs who undertook the Indigenous unit of study, this is the first time they are exposed to substantive knowledge and are challenged to reflect critically on Indigenous culture and practices (Taylor Citation2014). Several PSTs reported that they found the experience confronting and challenging, mainly because it challenged and often negated their misconceived ideas of Indigenous peoples (Morgan and Golding Citation2010). They also expressed surprise and shock that they had not been taught about Aboriginal peoples, histories, and contemporary cultures in their education (Mashford-Pringle and Nardozi Citation2013), and felt naive about ‘how little they knew as educated people about these people in our country’ (Auld, Dyer, and Charles Citation2016, 172). Still, some PSTs reported experiencing cognitive dissonance and the ‘implication that education is a tool of colonialism was really hard for them to wrap their heads around’ and ‘being confronted with how little they know about the context that’s all around them’ (Oskineegish and Berger Citation2021, 129). Others are fearful that they may ‘say the wrong thing’ and inadvertently cause offence to Indigenous students in their lesson delivery (Williams and Morris Citation2022, 9).

As such, PSTs appreciated the inclusion of Indigenous voices and perspectives in the study unit, the instruction on current and historical Indigenous-related events, and the opportunity to examine their privileged positions and what it means to prepare them to embed Indigenous content into their future teaching practice (Nardozi et al. Citation2014). Most PSTs reported positive learning and experiences and the desire to include Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in their future classrooms (Macdonald et al. Citation2022; Moore and Baker Citation2019; Riley et al. Citation2022). They felt that the Indigenous study unit has helped them deepen their understanding of their own culture and develop an increased appreciation of Indigenous knowledge and the need to be reappropriated and taught formally in the school curriculum (Mudaly Citation2018). It has enhanced their capacity to include local knowledge in their teaching and promoted an appreciation of the remoteness of the school and the Indigenous community (Lavery, Cain, and Hampton Citation2018). It has also heightened their awareness about respectful Indigenous teachings, the importance of story, culture, and the traditions of Indigenous practices while acknowledging the challenges they would encounter as educators (Gorecki and Doyle-Jones Citation2021; Lavery, Cain, and Hampton Citation2014). Several PSTs also reported stronger advocacy for a focus on knowledge that addresses problems of local and develops self-reliance instead of being reliant on western knowledge (Mudaly Citation2018). Weuffen et al. (Citation2017) observed that cultural workshops for non-Indigenous PSTs studying the Indigenous education course have the potential to enhance cross-cultural relations between PSTs and the Indigenous communities through increased opportunities for cultural engagement.

The third research question for this review was, ‘How equipped are pre-service teachers to embed Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in their teaching?’ To address this question, many PSTs voiced three key points when considering embedding IK in teaching; (1) the importance of building relationships with the Indigenous communities, (2) reflecting on their experiences during ITE courses, and (3) having practical hands-on experience of enacting the curriculum during placements.

Firstly, relationship building with Indigenous communities is an essential aspect of embedding Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in teaching, according to research conducted by Auld et al. (Citation2016), Farrell and Waatainen (Citation2021) Lavery et al. (Citation2014), and Lavery et al. (Citation2018). These studies suggest that PSTs who have the opportunity to engage with Indigenous communities and educators are better equipped to integrate Indigenous perspectives into their teaching practices. Auld et al. (Citation2016) found that PSTs who participated in cultural immersion experiences with Indigenous communities in Australia developed a deeper understanding and appreciation for Indigenous cultures and histories. Similarly, Farrell and Waatainen (Citation2021) argue that PSTs who engage in meaningful relationships with Indigenous communities are more likely to develop the necessary skills and knowledge to embed Indigenous perspectives in their teaching effectively. Lavery et al. (Citation2014) and Lavery et al. (Citation2018) also highlight the importance of relationship building and emphasise the need for teacher education programmes to provide opportunities for preservice teachers to connect with Indigenous communities and educators. Engaging in cultural immersion experiences and building meaningful relationships with Indigenous communities can enhance preservice teachers’ understanding and appreciation of Indigenous cultures and histories, ultimately promoting cultural awareness, sensitivity, and understanding in the classroom.

Following protocols in Indigenous communities is another crucial aspect of embedding Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in teaching (Auld, Dyer, and Charles Citation2016, Farrell and Waatainen Citation2021; Lavery, Cain, and Hampton Citation2014, Citation2018). These studies suggest that PSTs who respect Indigenous protocols and cultural practices are better equipped to engage in culturally responsive teaching and foster positive relationships with Indigenous students and communities. Auld et al. (Citation2016) found that PSTs who participated in cultural immersion experiences with Indigenous communities in Australia were required to follow specific protocols, such as seeking permission to enter traditional lands and acknowledging the Traditional Owners of the land. Similarly, Ferrel (2020) argues that PSTs should be aware of and follow Indigenous protocols when engaging with Indigenous communities and educators. Bennet and Moriarty (Citation2015), Martin et al. (Citation2020), and Gorecki and Doyle-Jones (Citation2021) also emphasise the importance of following protocols in Indigenous communities and acknowledge that failure to do so can have negative consequences for relationships with Indigenous communities and hinder the effectiveness of Indigenous education initiatives.

Secondly, reflecting on their experiences during their ITE degrees is a crucial step for PSTs in developing the importance of embedding Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in their teaching. This process can help PSTs to understand the importance of acknowledging and respecting Indigenous knowledge and perspectives and to develop culturally responsive pedagogies that reflect the diverse needs of their students. Auld et al. (Citation2016) suggest that PSTs who engage in meaningful and respectful interactions with Indigenous communities are more likely to develop a deep understanding of the importance of embedding Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in their teaching. This understanding can help PSTs to overcome the challenges of integrating Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into their teaching, such as a lack of confidence, knowledge, and resources. Similarly, Farrell and Waatainen (Citation2021) highlights the importance of reflecting on the impact of colonialism on Indigenous peoples and their cultures as a starting point for PSTs to develop their understanding of Indigenous knowledge and perspectives. This reflection can help them recognise the ongoing effects of colonialism and develop an awareness of their biases and assumptions. Lavery et al. (Citation2014) suggest that PSTs need to engage in critical self-reflection to identify and address their own biases and assumptions about Indigenous peoples and their cultures. This process can help PSTs to challenge stereotypes and misconceptions and to develop a more nuanced understanding of Indigenous knowledge and perspectives. Building on this idea, Lavery et al. (Citation2018) argue that PSTs need to engage in ongoing, critical reflection to develop the knowledge, skills, and dispositions necessary to embed Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in their teaching. This process involves understanding Indigenous worldviews, perspectives, and values and integrating this knowledge into all aspects of teaching and learning.

Oskineegish and Berger (Citation2021) argue that PSTs must understand Indigenous peoples historical and current experiences, as well as the ongoing impacts of colonialism and systemic oppression, to challenge inequities and injustices in their teaching. PSTs should also integrate Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into other knowledge areas, taking an interdisciplinary approach. To do so, Weuffen et al. (Citation2017) and Morales (Citation2017) recommend PSTs engage with Indigenous knowledge holders and community members to develop culturally responsive pedagogies.

Finally, having practical experience in enacting the curriculum is essential in helping PSTs develop the importance of embedding Indigenous knowledge and perspectives in their teaching. Practical experience can assist PSTs in meaningfully integrating Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into the curriculum, leading to benefits for their students. Both Farrell and Waatainen (Citation2021) and Macdonald et al. (Citation2022) emphasise the importance of providing PSTs with practical experiences that allow them to see the impact of incorporating Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into the curriculum. This can include field experiences, guest speakers, and classroom activities that engage with Indigenous knowledge and perspectives. Lavery et al. (Citation2014) believe that PSTs need to have opportunities to practice incorporating Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into their teaching during their ITE degrees, for example, working collaboratively with Indigenous community members, engaging with Indigenous resources and materials, and developing culturally responsive pedagogies that reflect the diverse needs of their students. According to Lavery et al. (Citation2018), PSTs should experiment with various methods of incorporating Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into the curriculum, with feedback and support from mentors, to develop the necessary knowledge and skills for teaching.

Gorecki and Doyle-Jones (Citation2021)also highlight the importance of providing PSTs with practical experiences that allow them to engage in relational learning with Indigenous communities. This can involve learning opportunities from Indigenous knowledge holders, participating in cultural activities, and developing respectful and reciprocal relationships with Indigenous peoples and communities. During their ITE degrees, PSTs should have opportunities to put Indigenous pedagogies and methodologies into practice by integrating Indigenous ways of knowing, being, and doing into the curriculum and developing a critical understanding of the role of culture and language in teaching and learning, according to Oskineegish and Berger (Citation2021). Similarly, Dharamshi (Citation2019) recommends that PSTs experiment with various techniques for incorporating Indigenous knowledge and perspectives into different subject areas, such as maths, science, and language arts, to develop interdisciplinary and cross-curricular approaches that allow students to connect Indigenous knowledge with other domains of knowledge.

Discussion

Based on the findings, we found that Indigenous knowledge is a key feature in many ITE programmes to help PSTs develop the skills and knowledge to embed Indigenous knowledge and perspective in teaching. However, the approach to how these skills and knowledge are taught varies significantly across institutions depending on university policies and directives, the structure of the ITE programme, the coordinators and teaching team involved in conceptualising the subjects, as well as the opportunities to engage with the local Indigenous community. At the university level, Indigenous knowledge can be taught as a standalone unit of study as well as embedded in PSTs teaching subjects. The strategies deployed range from lectures, workshops, tutorials, field trips, service-learning or a combination of the strategies.

Most PSTs have found their learning experience to be positive and meaningful. While the unit of study has been confronting and challenging for some PSTs as it disrupted their previous misconceived notion about Indigenous people and culture, it has also alerted them to their knowledge deficit in this area. Many PSTs reported a heightened awareness of respectful Indigenous teachings, a greater appreciation for the Indigenous community, and in some cases, advocacy of tapping into local knowledge instead of relying on western-centric ideas.

We also found that embedding Indigenous Knowledge and perspectives in teaching requires PSTs to build meaningful relationships with Indigenous communities, reflect on their ITE experiences, and have practical hands-on experience. These key points highlight the importance of promoting reflective practices and ongoing professional development for PSTs. Furthermore, they emphasise the need for collaboration and partnership with Indigenous communities to ensure that PSTs are equipped to embed Indigenous perspectives effectively in their teaching practice.

Conclusion and recommendations

Despite the range of strategies universities have implemented to equip pre-service teachers (PSTs) with Indigenous Knowledge (IK), some appear more useful than others. While some strategies effectively prepare PSTs for integrating IK into their teaching practice, others fall short. This highlights the need for ongoing evaluation and refinement of IK programmes in Initial Teacher Education (ITE).

ITE programmes have made strides in incorporating IK, but there are still gaps in achieving the original intent of promoting reconciliation and understanding Indigenous culture and history. Clear ownership and a defined target for these courses and programmes are necessary to ensure their effectiveness. This requires collaboration and partnership with Indigenous communities and knowledge keepers to develop meaningful and respectful programmes. By addressing these gaps, ITE programmes can better equip PSTs to embed IK in their teaching practice and promote a more inclusive and culturally responsive education system.

Several actions need to be taken to improve Indigenous Knowledge (IK) programmes and better engage with Indigenous communities. Firstly, clear ownership of the programme is necessary, with a designated person or group in charge of its implementation and evaluation. This will ensure accountability and provide a point of contact for community members. Secondly, with regular reviews, clear learning outcomes and drivers should be established to ensure that the programme meets the needs of the school and community. In addition, partnerships and immersion programmes should be incorporated into the curriculum to provide students with a more hands-on experience and a better understanding of the culture and traditions of Indigenous people. Training should be provided to ensure that teachers and tutors are equipped to teach Indigenous knowledge, including awareness of IK protocols and fundamental cultural aspects. Workshops and ongoing professional development should be mandatory to ensure that educators are engaging with Indigenous knowledge in a respectful and meaningful way.

Finally, universities need to move away from superficial and tokenistic approaches to Indigenous knowledge and engage in more meaningful ways. Coordination with local knowledge holders is necessary to design effective strategies and incorporate local knowledge into the curriculum. By implementing these actions, schools and universities can better engage with Indigenous knowledge, promote cultural understanding and respect, and prepare students for a more diverse and inclusive society.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Arksey, H., and L. O’Malley. 2005. “Scoping Studies: Towards a Methodological Framework.” International Journal of Social Research Methodology 8 (1): 19–32. https://doi.org/10.1080/1364557032000119616.

- Auld, G., J. Dyer, and C. Charles. 2016. “Dangerous Practices: The Practicum Experiences of Non-Indigenous Pre-Service Teachers in Remote Communities.” Australian Journal of Teacher Education 41 (6). https://doi.org/10.14221/ajte.2016v41n6.9.

- Battiste, M., L. Bell, and L. M. Findlay. 2002. “Decolonizing Education in Canadian Universities: An Interdisciplinary, International, Indigenous Research Project.” Canadian Journal of Native Education 26 (2): 82.

- Bennet, M., and J. Lancaster. 2012. “Improving Reading in Culturally Situated Contexts.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 41 (2): 208–217. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2012.18.

- Bennet, M., and B. Moriarty. 2015. “Language, Relationships and Pedagogical Practices: Pre-Service Teachers in an Indigenous Australian Context.” International Journal of Pedagogies and Learning 10 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/22040552.2015.1084672.

- Berryman, M., S. SooHoo, A. Nevin, and T. Ford. 2019. “A Conceptual Model for Developing Indigenous Teacher candidates’ Knowledge and Skills Through Integrating Indigenous Knowledge in Teacher Education.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 23 (9): 1023–1037. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2018.1548524.

- Brayboy, B. M. J., and E. Maughan. 2009. “Indigenous Knowledges and the Story of the Bean.” Harvard Educational Review 79 (1): 1–21. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.1.l0u6435086352229.

- Chilisa, B. 2012. ”Postcolonial Indigenous Research Paradigms.” Indigenous Research Methodologies, 98–127. Sage Publications.

- Deer, F. 2013. “Integrating Aboriginal Perspectives in Education: Perceptions of Pre-Service Teachers.” Canadian Journal of Education 36 (2): 175–211.

- De Santolo, J., B. Fogarty, and M. Nakata. 2016. “Exploring Indigenous Perspectives on Integrating Indigenous Knowledges into Teacher Education.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 44 (4): 340–354. https://doi.org/10.1080/1359866X.2015.1101832.

- Dharamshi, P. 2019. ““This is Far More Complex Than I Could Have Ever Imagined.” FIRE: Forum for International Research in Education 5 (2, November): 28–46. https://doi.org/10.32865/fire201952169.

- Farrell, T., and P. Waatainen. 2021. “Face-To-Face with Place: Place-Based Education in the Fraser Canyon.” Canadian Social Studies 51 (2). https://doi.org/10.29173/css3.

- Gorecki, L., and C. Doyle-Jones. 2021. “Centering Voices: Weaving Indigenous Perspectives in Teacher Education.” The Canadian Journal of Action Research 21 (3): 115–141. https://doi.org/10.33524/cjar.v21i3.536.

- Harrison, N., and B. Murray. 2012. “Reflective Teaching Practice in a Darug Classroom: How Teachers Can Build Relationships with an Aboriginal Community Outside the School.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 41 (2): 139–145. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2012.14.

- Hart, V., S. Whatman, J. McLaughlin, and V. Sharma-Brymer. 2012. “Pre-Service teachers’ Pedagogical Relationships and Experiences of Embedding Indigenous Australian Knowledge in Teaching Practicum.” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 42 (5): 703–723. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2012.706480.

- Jorgensen, R., P. Grootenboer, R. Niesche, and S. Lerman. 2010. “Challenges for Teacher Education: The Mismatch Between Beliefs and Practice in Remote Indigenous Contexts.” Asia-Pacific Journal of Teacher Education 38 (2): 161–175. https://doi.org/10.1080/13598661003677580.

- Kovach, M. 2010. “Conversation Method in Indigenous Research.” First Peoples Child & Family Review 5 (1): 40–48. https://doi.org/10.7202/1069060ar.

- Lavery, S., G. Cain, and P. Hampton. 2014. “A Service-Learning Immersion in a Remote Aboriginal Community: Enhancing Pre-Service Teacher Education.” International Journal of Whole Schooling 10 (2): 1–16.

- Lavery, S., G. Cain, and P. Hampton. 2018. “Walk Beside Me, Learn Together: A Service-Learning Immersion to a Remote Aboriginal School and Community.” Australian and International Journal of Rural Education 28 (1). https://doi.org/10.47381/aijre.v28i1.171.

- Levac, D., H. Colquhoun, and K. K. O’Brien. 2010. “Scoping Studies: Advancing the Methodology.” Implementation Science 5 (1): 69. https://doi.org/10.1186/1748-5908-5-69.

- Lopes Cardozo, M. T. A. 2012. “Transforming Pre-Service Teacher Education in Bolivia: From Indigenous Denial to Decolonisation?” Compare: A Journal of Comparative and International Education 42 (5): 751–772. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057925.2012.696040.

- Macdonald, M., E. Gringart, S. Booth, and R. Somerville. 2022. “Pedagogy Matters: Positive Steps Towards Indigenous Cultural Competency in a Pre-Service Teacher Cohort.” The Australian Journal of Education 67 (1): 6–27. https://doi.org/10.1177/00049441221107974.

- Mackinlay, E., and K. Barney. 2014. “PEARLs, Problems and Politics: Exploring Findings from Two Teaching and Learning Projects in Indigenous Australian Studies at the University of Queensland.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 43 (1): 31–41. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2014.5.

- Martin, R., C. Astall, K.-L. Jones, and D. Breeze. 2020. “An Indigenous Approach to Self-Study of Teacher Education Practices (S-STEP) in Aotearoa New Zealand.” Studying Teacher Education 16 (2): 127–144. https://doi.org/10.1080/17425964.2020.1732911.

- Mashford-Pringle, A., and A. G. Nardozi. 2013. “Aboriginal Knowledge Infusion in Initial Teacher Education at the Ontario Institute for Studies in Education at the University of Toronto.” International Indigenous Policy Journal 4 (4): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.18584/iipj.2013.4.4.3.

- McInnes, B. D. 2017. “Preparing Teachers as Allies in Indigenous Education: Benefits of an American Indian Content and Pedagogy Course.” Teaching Education 28 (2): 145–161. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2016.1224831.

- Miles, M. B., A. M. Huberman, and J. Saldaña. 2020. Qualitative Data Analysis: A Methods Sourcebook. 4th ed. Los Angeles: SAGE.

- Monk, S., T. Riley, and H. Van Issum. 2022. “Using Arts-Based Inquiry and Affective Learning to Teach Indigenous Studies in a First-Year Preservice Teacher Education Course.” Journal of Transformative Education 21 (2): 1–19. https://doi.org/10.1177/15413446221105570.

- Moore, S. J., and W. Baker. 2019. “Indigenous Creativities, the Australian Curriculum, and Pre-Service Teachers.” The International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives 18 (3): 88–99.

- Morales, M. P. E. 2017. “Exploring Indigenous Game-Based Physics Activities in Pre-Service Physics teachers’ Conceptual Change and Transformation of Epistemic Beliefs.” Eurasia Journal of Mathematics, Science and Technology Education 13 (5): 1377. https://doi.org/10.12973/eurasia.2017.00676a.

- Morgan, S., and B. Golding. 2010. “Crossing Over: Collaborative and Cross-Cultural Teaching of Indigenous Education in a Higher Education Context.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 39 (S1): 8–14. https://doi.org/10.1375/S1326011100001083.

- Mudaly, R. 2018. “Towards Decolonising a Module in the Pre-Service Science Teacher Education Curriculum: The Role of Indigenous Knowledge Systems in Creating Spaces for Transforming the Curriculum.” Journal of Education, (74): 47–66. https://doi.org/10.17159/2520-9868/i74a04.

- Nakata, M. N. 2007. Disciplining the Savages, Savaging the Disciplines. Canberra, ACT: Aboriginal Studies Press.

- Nardozi, A., J.-P. Restoule, K. Broad, N. Steele, and U. James. 2014. “Deepening Knowledge to Inspire Action: Including Aboriginal Perspectives in Teaching Practice.” In Education 19 (3). https://doi.org/10.37119/ojs2014.v19i3.140.

- Oskineegish, M., and P. Berger. 2021. “Teacher candidates’ and Course instructors’ Perspectives of a Mandatory Indigenous Education Course in Teacher Education.” Brock Education Journal 30 (1): 117. https://doi.org/10.26522/brocked.v30i1.798.

- Peralta, L. R., D. O’Connor, W. G. Cotton, and A. Bennie. 2016. “Pre-Service Physical Education teachers’ Indigenous Knowledge, Cultural Competency and Pedagogy: A Service Learning Intervention.” Teaching Education 27 (3): 248–266. https://doi.org/10.1080/10476210.2015.1113248.

- Peters, M. D., C. M. Godfrey, H. Khalil, P. McInerney, D. Parker, and C. B. Soares. 2015. “Guidance for Conducting Systematic Scoping Reviews.” International Journal of Evidence-Based Healthcare 13 (3): 141–146. https://doi.org/10.1097/XEB.0000000000000050.

- Pridham, B., D. Martin, K. Walker, R. Rosengren, and D. Wadley. 2015. “Culturally Inclusive Curriculum in Higher Education.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 44 (1): 94–105. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2015.2.

- Riley, T., T. Meston, J. Ballangarry, B. A. McCormack, and S. Low-Choy. 2022. “From Yarning Circles to Zoom: Navigating Sensitive Issues within Indigenous Education in an Online Space.” International Journal of Inclusive Education 1–16. https://doi.org/10.1080/13603116.2022.2127501.

- Smith, L. T. 2021. Decolonizing Methodologies: Research and Indigenous Peoples. London: Bloomsbury Publishing.

- Surtees, N., L. T. T. Taleni, R. Ismail, B. Rarere-Briggs, and R. Stark. 2021. “Sailiga Tomai Ma malamalama’aga fa’a-Pasifika—seeking Pasifika Knowledge to Support Student Learning: Reflections on Cultural Values Following an Educational Journey to Samoa.” New Zealand Journal of Educational Studies 56 (2): 269–283. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40841-021-00210-7.

- Tanaka, M., L. Williams, Y. J. Benoit, R. K. Duggan, L. Moir, and J. C. Scarrow. 2007. “Transforming Pedagogies: Pre-Service Reflections on Learning and Teaching in an Indigenous World.” Teacher Development 11 (1): 99–109. https://doi.org/10.1080/13664530701194728.

- Taylor, R. 2014. “‘It’s All in the Context’: Indigenous Education for Pre-Service Teachers.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 43 (2): 134–143. https://doi.org/10.1017/jie.2014.16.

- Tricco, A. C., E. Lillie, W. Zarin, K. K. O’Brien, H. Colquhoun, D. Levac, D. Moher, et al. 2018. “PRISMA Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and Explanation.” Annals of Internal Medicine 169 (7): 467–473. https://doi.org/10.7326/M18-0850.

- Tuck, E., and K. W. Yang. 2012. “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 1–40.

- University of South Australia. 2022. Apply PCC. University of South Australia. https://guides.library.unisa.edu.au/ScopingReviews/ApplyPCC.

- Van Gelderen, B. 2017. “Growing Our Own: A ’two way’, Place-Based Approach to Indigenous Initial Teacher Education in Remote Northern Territory.” Australian and International Journal of Rural Education 27 (1): 14–28. https://doi.org/10.47381/aijre.v27i1.81.

- Walter, M. 2013. Indigenous Statistics: A Quantitative Research Methodology. United Kingdom: Left Coast Press.

- Weuffen, S. L., F. Cahir, and A. M. Pickford. 2017. “The Centrality of Aboriginal Cultural Workshops and Experiential Learning in a Pre-Service Teacher Education Course: A Regional Victorian University Case Study.” Higher Education Research and Development 36 (4): 838–851. https://doi.org/10.1080/07294360.2016.1242557.

- Williams, E., and J. Morris. 2022. “Integrating Indigenous Perspectives in the Drama Class: Pre-Service teachers’ Perceptions and Attitudes.” Australian Journal of Indigenous Education 51(1). https://doi.org/10.55146/ajie.2022.26.