Profiling tells us that Australian archaeologists are predominantly young (<45 years of age) non-Indigenous, women born in Australia (i.e. settlers). We work predominantly on Indigenous heritage, and are engaged in cultural heritage management (CHM) as our primary practice (Mate and Ulm Citation2021). We have every reason to expect these demographic trends will continue in the short-to-medium term (Monks et al. Citation2023). Yet a glance through the contents of any issue of Australian Archaeology, our flagship journal, reveals that our discourse has been shaped by the voices of people who do not resemble this profile. Reflecting here on who has made the ‘loudest noise’, I consider whose voices we may want to (continue to) include and amplify in Australian Archaeology. For the contents of our journal also record that we have sought to give a voice to diverse members of our community, especially Indigenous colleagues (see Supplementary Material (SM) for details) as part of the ethical accountability of our work (Doering et al. Citation2022; Fitzpatrick Citation2021). Aspiring to garner a more balanced and representative chorus, I offer a suggestion.

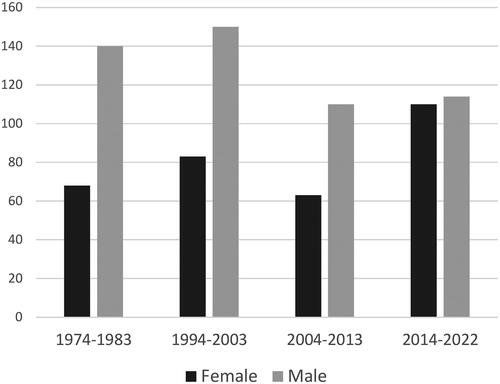

The racial and gender homogeny (male whiteness) of archaeology continues to challenge our discipline globally, with Australia mirroring trends in the USA and UK (Beck et al. Citation2021). Here too, historically, the loudest voices have belonged to men (). But this simple metric belies the central contributions of Isabel McBryde, Sharon Sullivan, Marjorie Sullivan, Helen Brayshaw, Sandra Onus, Sandra Bowdler, Eleanor Crosby, Lesley Maynard and others to the early, agenda-setting volumes of our journal. Some 50 years since their formative efforts, it seems we are approaching a watershed, nearing gender parity of lead authors in Australian Archaeology for the first time. This is remarkable, considering the impacts of the COVID-19 crisis disproportionately affected women due to their predominance in caregiver roles. In the early months of the pandemic, many journal editors reported a striking decline in submissions from female scholars (Hanscam and Witcher Citation2023:93) including Ulm and Ross (Citation2021) who noted a drop from ∼70 to 40% in female-led articles (although they noted a rebound in the last two issues of 2021). It is worth highlighting that the last timeslice in records only nine years of data. When articles from 2023 are considered, the pendulum may swing to a dominance of female-led articles for the first time.

Figure 1. Gender of sole/first authors* of articles in Australian Archaeology. Note that in six instances between 1974 and 1983, and three instances between 1994 and 2003, first names could not be identified for authors, so they were excluded from the summary. One exciting ‘first’ was recorded between 2014 and 2022 with the first Aboriginal Corporation-led article (see GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation Citation2020). *First names of the authors of articles (excluding editorials, obituaries and other such notices), either listed in the SM or determined through further research, were used as a proxy for gender. This method is comparable to bibliometric surveys in journals in the USA and UK (Beck et al. Citation2021; Hanscam and Witcher Citation2023). I recognise this perpetuates a gender binary and that I have not accounted for gender self-identification or queerness. I apologise if I have misgendered colleagues.

Most contributors to Australian Archaeology are academics (including higher degree by research candidates) mirroring bibliometric studies of similar journals (e.g. 85% of American Antiquity submissions were made by academics 2007–2017; Hanscam and Witcher Citation2023:97). The reason for this is simple—it is our job to conduct and disseminate the results of archaeological research, and to reflect on and innovate archaeological practice (technically, methodologically and through teaching and learning). Of course, academics are not the only ones making these contributions, but those of us employed by universities, museums and other such institutions have mandated KPIs around research, education/outreach, and service to our discipline. Indeed, academic career progression relies on measures of prestige and peer esteem that recognise we are meeting these targets. ‘Publish or perish’, or in contemporary parlance ‘prestige or perish’, remain driving forces (Beck et al. Citation2021).

By contrast, CHM/regulatory based research and innovation are not as easily disseminated, often requiring navigating commercial/confidentiality arrangements with CHM/regulatory sectors that are more likely to value throughput and revenue, rather than peer-reviewed publication. Prior to the Juukan George travesty, proponents engaging CHM practitioners had little to no appetite to support archaeological investigations beyond regulatory compliance contributing to pervasive expectations that consultants will engage in our discipline’s discourse by producing publications in addition to their normal workloads (i.e. gratis) (Wallis Citation2020). There is intersectionality here also. In other Western settler contexts like the USA, the largest concentration of female archaeologists is in the CHM sector, which does not incentivise publication in peer-reviewed journals (Hanscam and Witcher Citation2023:96). Likewise in Australia, much of the research and innovation conducted in the CHM sector is recorded in the non-peer-reviewed, predominantly female-authored, ‘grey literature’, sometimes presented at conferences, but rarely published, with recent profiling of student pipelines suggesting such trends will continue (Monks et al. Citation2023).

Another important driver of research and innovation is Indigenous organisations engaging at their discretion with archaeological expertise in relation to their heritage. This is ‘quiet work’ in the context of our disciplinary discourse, as the results of such projects are less often shared beyond the Indigenous custodians of the heritage examined (who are dealing with heritage management alongside more pressing issues such as community housing and healthcare). Consequently, this work is sometimes shared through conference presentations, but rarely published, and seldom makes it into the ‘grey literature’ curated by state-based regulatory institutions.

Australian Archaeology occupies a unique role at the centre of our community of practice, through the allocation of professional capital—peer recognition of quality work. Even in an age of academic social networking websites and pre-print servers, researchers remain dependent on the symbolic function of publishers to endorse their work. Decisions about where to publish are informed by the prestige hierarchies that permeate academic archaeology (Beck et al. Citation2021). However, audience still matters. Publishing in Australian Archaeology guarantees an audience with our membership (sent the journal as part of their dues). Our journal therefore remains a powerful way to speak to our community. Critically, such professional capital and reach are valuable to archaeologists regardless of their being primarily based in the academic, CHM or regulatory sectors.

As a community we are good at allocating professional capital, recognising, and celebrating high quality research, and rewarding sustained positive contributions to our discipline through the Rhys Jones Medal, Lifetime Membership of the Association and the Bruce Veitch Award; and the journal, Darrell West, Laila Haglund and conference presentation Prizes. We also work towards continued inclusion with Indigenous peoples, students and delegates with carer responsibilities provided opportunities for supported conference participation through subsidies, and student research via annual competitive stipends. But we could do more.

We should assign professional capital to the voices we want to include. We can foster inclusion in our discipline’s discourse by recognising that opportunities for the dissemination of research are not equal. With public scrutiny (including that of shareholders) motivating proponents’ concerns to demonstrate a social licence to operate, we could take the opportunity to fund a dedicated scheme through industry support. I propose we instate a publication grant that offers a dignified living wage to support colleagues who do not hold academic positions to write articles for Australian Archaeology, disseminating work resulting from Indigenous organisation-led, CHM, regulatory or other professional contexts that do not otherwise incentivise peer-reviewed publication.Footnote1

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (166.7 KB)Acknowledgements

Thanks to Bruno David for the conversation that got me thinking about the quiet work going on all around us. I am grateful to Jessica Donald and the digital management team at Routledge Taylor & Francis Australasia for providing our journal’s contents (SM). I mean no offence to the Puutu Kunti Kurrama and Pinikura people by referring to the destruction of their heritage, which was sadly a watershed for corporate accountability in Australian CHM.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Notes

1 For articles relating to Indigenous heritage, funding should include adequate remuneration for Indigenous community expertise and content oversight.

References

- Beck, J., E. Gjesfjeld and S. Chrisomalis 2021 Prestige or perish: Publishing decisions in academic archaeology. American Antiquity 86(4):669–695.

- Doering, N.N., S.S. Dudeck, C. Elverum, J.E. Fisher … E.M. Omma 2022 Improving the relationships between Indigenous rights holders and researchers in the Arctic: An invitation for change in funding and collaboration. Environmental Research Letters 17(6):065014.

- Fitzpatrick, A.L. 2021 Accountability in action: How can archaeology make amends? Bulletin of the History of Archaeology 31(1):14–16.

- GunaiKurnai Land and Waters Aboriginal Corporation, R. Mullett, J. Fresløv and B. David 2020 Disrupting what, whose Country, whose paradise? Australian Archaeology 86(3):299–301.

- Hanscam, E. and R. Witcher 2023 Women in antiquity: An analysis of gender and publishing in a global archaeology journal. Journal of Field Archaeology 48(2):87–101.

- Mate, G. and S. Ulm 2021 Working in archaeology in a changing world: Australian archaeology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic. Australian Archaeology 87(3):229–250.

- Monks, C., G.L.S. Stannard, S. Ouzman, T. Manne … S. Ulm 2023 Why do students enrol in archaeology at Australian universities? Understanding pre-enrolment experiences, motivations, and career expectations. Australian Archaeology 89(1):32–46.

- Ulm, S. and A. Ross 2021 Editorial. Australian Archaeology 87(3):227–228.

- Wallis, L.A. 2020 Disrupting paradise: Has Australian archaeology lost its way? Australian Archaeology 86(3):284–294.