ABSTRACT

Working with Children checks in Australia are regulated by legislation and designed to be used as pre-employment criminal history screening for child-related roles and organisations. Most Australian universities require prospective social work students to hold Working with Children clearance as a precondition to enrolment. Little is known about the reasoning for such application, and this Queensland study aims to contribute to resolving this question, by examining the frequency by which nonregulated jobs advertised online require a Working with Children check (a Blue Card in Queensland). Of the 400 job advertisements analysed, just over half of the nonregulated roles did not require a Blue Card. This suggests it is likely that there are field placements available to students without Working with Children clearance. If Blue Cards are not required to secure field placements for students, then applying a blanket requirement for Working with Children checks prior to enrolment in a social work course is unnecessary and may be discriminatory.

Criminal history and associated screening methods, such as Working with Children clearances, should only be used when justified, and to utilise such screening requirements when not required may be discriminatory and unfair.

This analysis of the job market suggests that requiring Working with Children checks as a precondition to studying social work is not justified on the grounds that there will be limited placement opportunities, or subsequent jobs, for ineligible students.

Some form of gatekeeping to the social work profession is required to protect vulnerable service users, but unnecessarily restricting access to education for prospective students with criminal histories has implications for service users who might benefit from access to social workers with lived experience.

IMPLICATIONS

Working with Children checks in Australia are a form of pre-employment criminal history screening conducted by government agencies (Child Family Community Australia, Citation2021). The aim of Working with Children checks is to keep children safe and protect them from harm by screening and monitoring people who work in child-related organisations or roles (Blue Card Services, Citation2020). Child-related criminal history screening was enhanced in Australia from 2000, following the NSW Wood Royal Commission’s inquiries into paedophilia (Simpson, Citation1998). Screening arrangements are now regulated by state or territory law in every Australian jurisdiction. Laws are different in each jurisdiction, but commonly involve consideration of a person’s entire criminal record and any other involvement with the criminal justice or child protection systems (Blue Card Services, Citation2020). It is important to note that it is not only child-related offences or sexual or violence offences that are taken into account in Working with Children checks. People can be denied a clearance based on, for example, drug and alcohol charges and offences, property charges and offences, public order matters, and professional disciplinary information unrelated to children, if these are deemed to make a person unsuitable (Lawright, Citation2019). The Working with Children check is designed to prohibit certain people from working or volunteering in specified child-related roles. Many of these roles are in the human services sector, such as residential care work, and child and youth counselling. While Working with Children checks regulate certain organisations and roles, both paid and voluntary, involved in providing services to children, they are not designed to be applied across the entire human services sector.

Working with Children checks operate alongside human rights laws that do not allow discrimination in employment against people based on their criminal history. Under the Australian Human Rights Commission Act 1986 (Cth) (Australian Human Rights Commission, Citationn.d.), people are protected against discrimination on the grounds of past criminal history, permitting criminal convictions to be taken into account only when they are an “inherent requirement of the job”, or if another law, such as the law governing Working with Children checks, allows for this to occur. Therefore, while it is lawful (and justifiable) to screen for criminal history in order to protect children from risk of harm, the same justification does not apply to all areas of employment, and it may be discriminatory to apply such screening beyond the scope intended by child-related employment screening legislation. As well as avoiding discrimination, there are positive reasons to not restrict employment, study, and volunteering opportunities in the human services sector for people with criminal histories, unless required for the protection of vulnerable service users. According to Barrenger et al. (Citation2019), practitioners with criminal histories can be a useful component in the recovery of clients with criminal justice involvement by demonstrating that change is possible. It has been argued that there are benefits from a social worker with lived experience of incarceration for both the worker and the client, through challenging stigma and discrimination, and managing power inequalities (Duvnjak et al., Citation2021). Further, it is important to recognise and highlight the skills, knowledge, and lived experience that workers with a criminal history may bring to social work to advocate for, and effect change to, unjust processes (Bramley et al., Citation2021).

There are some populations that are more likely to have criminal convictions than others, and these groups may be further disadvantaged by pre-employment criminal history checks. In Australia, Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people are highly over-represented in the criminal justice system—especially young people and women (Krieg et al., Citation2016)—as a result of the impacts of colonisation and related collective trauma (Menzies, Citation2019). Young people with cognitive disabilities are also likely to have more frequent contact with police and appear more often in the criminal justice system (Ellem & Richards, Citation2018). Those who have experienced high levels of trauma, family violence, and sexual abuse have also been found to be highly represented in the prison system (Australian Institute of Health & Welfare, Citation2014). These cumulative disadvantages often intersect with engagement with the criminal justice system (Vliek, Citation2018).

In addition to being a barrier to employment or volunteer work in some fields, Working with Children checks can also present barriers to tertiary study. Most Australian universities require social work students to have a current Working with Children check (or similar, depending on jurisdiction) prior to undergoing field placement, and sometimes prior to enrolment (Young et al., Citation2019). Such checks may deter prospective students from applying for social work programs due to the shame or stigma attached to a criminal history (Johnson et al., Citation2021), or because they think they may not be eligible for enrolment. This has the potential to exclude future practitioners with lived experience of contact with the criminal justice system, who may have valuable insights and understandings when working with socially excluded client or consumer groups (Fox, Citation2020). Unfairly restricting education and employment can place a personal toll on an individual. Such restrictions raise equity concerns that relate to civil liberties, the rehabilitation of offenders, and the over-representation of disadvantaged people in the criminal justice system. Therefore, applying a blanket requirement for social work students to have Working with Children clearance has potential negative implications. Universities appear to have taken on a gatekeeping role for entry into the social work profession, and possible concern about risk management may have led to policies that limit access to social work education for those with a criminal history (Duvnjak et al., Citation2021).

There may also be concerns about sourcing field placements for students with a criminal history (Curran et al., Citation2020). A study surveying 100 field directors in the United States found that the majority of respondents stated that it was more difficult to place students with a criminal history, as more than half of their placement agencies required criminal history checks (Dottin, Citation2018). Even so, as the number of students with a criminal history is likely to be a minority, if half of all field placement opportunities do not require a criminal history check, there would appear to be sufficient placements available for students with a criminal history. However, there are limited numbers of empirical studies about potential barriers encountered when finding field placement for students (Bramley et al., Citation2021).

Little is known about the reasons why Australian universities restrict access to social work degrees for people who may be ineligible for a Working with Children check. In some countries, social work registration may be subject to criminal history checks. However, this is not currently the case in Australia (Crisp & Gillingham, Citation2008). Concern about the availability of field placement opportunities for students without Working with Children clearance may be a contributing factor (Curran et al., Citation2020; Dottin, Citation2018). This study seeks to contribute to resolving whether this is a justified concern by examining the extent to which Working with Children clearances are required by prospective employers filling vacancies in nonregulated roles. The aim of the study was to explore the availability of jobs with no requirement for a Working with Children clearance, as a means of exploring whether suitable field placement options may be available to social work students. The research question guiding the study was: “To what extent are Working with Children checks required by employers advertising roles that are not regulated by Working with Children legislation?” The study was undertaken by social work researchers at a Queensland university and uses Queensland as a case study. It provides an overview of the occurrence by which nonregulated human services jobs—that is, jobs that are not within the scope of laws governing Working with Children checks—that are advertised online required applicants to hold a Working with Children check.

Method

The Queensland Context

The Working with Children check in Queensland is governed by the Working with Children (Risk Management and Screening) Act 2000 (Qld), and applies to employees, volunteers, and trainee students who are engaged in regulated employment. To work or volunteer with children in Queensland, you need to have a current Working with Children check if your work fits a category of employment under the Act. These areas of employment are listed in Box 1. Importantly, for both regulated employment and regulated businesses, the Act only relates to services provided to children, with a child being defined as an individual under 18 years of age. A person does not need a Working with Children check if they happen to have contact with a child in their work or volunteer activities.

Box 1 Working with Children (Risk Management and Screening) Act 2000. Schedule 1. Regulated Employment and Businesses for Employment Screening. Section 156

Part 1 Regulated Employment

1. Residential facility at which a child accommodation service is provided, or Commonwealth funded child accommodation

2. School boarding facility

3. School services or activities directed at children (other than by registered teachers or parents)

4. Education and care service or QEC service (e.g., long day care, outside school hours care, kindergarten, occasional care etc.)

5. Child care and similar employment (including babysitting, nanny service, adjunct care provider etc.)

6. Child directed services provided by churches, clubs, or associations

7. Health, counselling and support services to children

8. Private teaching, coaching, or tutoring a child or children

9. Education programs conducted outside of school

10. Child accommodation services including home stays

11. Religious representatives providing services directed mainly at children

12. Sport and active recreation directed mainly towards children

13. Emergency services cadet program teaching, coaching, or tutoring a child or children

14. School crossing supervisors

15. Care of children under the Child Protection Act 1999

Study Design

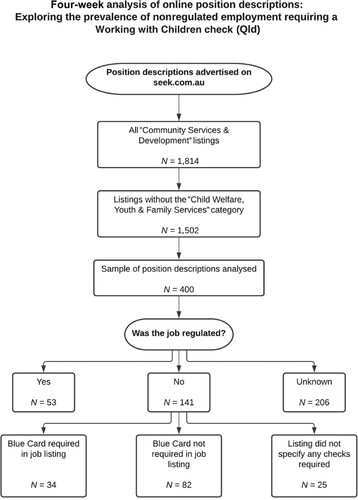

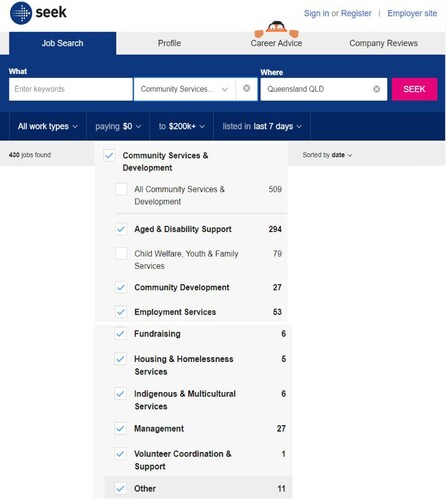

To examine the prevalence of nonregulated human services positions that were advertised with the requirement of a Working with Children check (also referred to as a “Blue Card” in Queensland), position descriptions were sourced from the seek.com.au website. On four consecutive Mondays from 12 April to 3 May 2021, position descriptions advertised within the previous seven days were accessed and analysed. When entering the search parameters in the “Job Search” section of the website, the “what” section was left blank and the “where” box was limited to positions located in Queensland. The classification selected was “Community Services & Development”, and the total number of jobs within the above parameters listed for each seven-day period was recorded. The “Child Welfare, Youth & Family Services” box was then unticked to exclude this category, and the amended number of total job listings was recorded. The reason for this was that the majority of jobs listed in this category were likely to be regulated under the legislation. As the purpose of the current study was to explore nonregulated employment requiring a Working with Children check or Blue Card, these jobs were not likely to be relevant. The remaining positions were sorted by date, with the most recent advertisement appearing first. “Featured” jobs appearing at the top of the search results were excluded, as they also appeared on the date they were posted, which would duplicate data. provides a visual representation of the search parameters used on the seek.com.au website.

Figure 1 Seek.com.au. Job search parameters

Each position description was analysed to determine whether the job was regulated under the legislation, and they were categorised as “yes”, “no” or “unknown”. In accordance with the Act, regulated roles were those that provided direct services to children under 18 years of age in a regulated area of employment. Descriptions that did not specify whether direct services to children were provided were categorised as “unknown”. The number of positions that were categorised as “yes” (regulated) and “unknown” were counted and no further analysis conducted because we were interested in whether Blue Cards were required for employment in nonregulated areas. Jobs classified as “not regulated” specified that the client group consisted of adults and did not provide services to children. The number of jobs that were not regulated were counted, and the position descriptions were further analysed to determine whether a Blue Card requirement was listed in the advertisement. Descriptions that stated the need for a police check or a disability worker check but did not list a Working with Children check were categorised as not requiring a Blue Card. The rationale for this was that if an advertiser specified one check but not another, there was a reasonable probability that the omitted check was deliberately omitted and therefore not required. In contrast, those that did not list any of the above three checks were categorised as “unknown”, as the omission of any reference to checks could suggest that some or all of these checks may be required. If required, website or PDF links provided were accessed for further information. Each Monday, positions were sorted by date, starting with the most recent listing; the first 100 position descriptions were accessed to provide a total sample size of 400 jobs over the four-week period. presents a flow chart of the process and sample size for each step.

Results

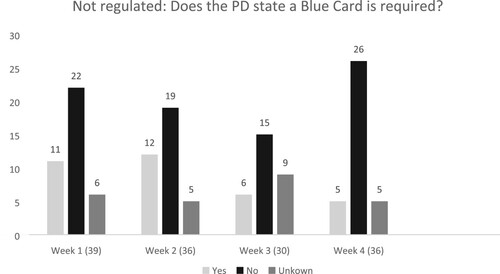

Over the four-week data collection period, 1,814 positions in the “Community Services & Development” category were advertised in Queensland. After the “Child Welfare, Youth & Family Services” (most jobs likely to be regulated) category was removed, 1,502 advertised jobs remained. Of those, 400 position descriptions were accessed and analysed to determine whether the job was regulated under the legislation. Two hundred and six descriptions did not include sufficient information to determine whether the position involved delivering direct services to children, and a further 53 jobs were classified as regulated employment. The remaining 141 position descriptions provided sufficient information to determine that they were not regulated. Examples of nonregulated positions that required Blue Cards were a disability support worker caring for an adult male, an activities officer in an aged care facility, a community mental health practitioner in an adult program, and a grants manager in a multicultural organisation. provides a weekly regulation status breakdown of the 400 position descriptions analysed. Of the 141 nonregulated jobs, 82 (58%) did not require a Blue Card. These jobs listed a requirement for a police or disability worker check, but not a Working with Children check. A further 25 did not specify the need for a criminal history, Working with Children, or disability worker check and were categorised as “unknown”. There were 34 nonregulated position descriptions that specified a Blue Card was required. Of these 34 positions, 11 jobs—almost a third—were listed by one organisation for aged care positions. Half of the 34 were for jobs in aged care, a further 11 were for administrative positions, with the final six providing direct services to adults. A weekly breakdown of the Blue Card requirement categories is set out in .

Table 1 Working with Children Regulation Status of Online Position Descriptions

Discussion

There are many human services organisations that provide services to children and are regulated by Working with Children laws; consequently, they advertise positions with Working with Children clearance requirements attached. At the same time, many human services organisations are not regulated because they provide services to adults. The purpose of the current study was to explore the prevalence of nonregulated jobs being advertised as requiring Working with Children clearance. The legislation states that a Working with Children check is only required when providing direct services to children in a regulated role or business. The findings indicate that while there are positions advertised in nonregulated areas that do require a Working with Children clearance (arguably, inappropriately), there are numerous positions advertised that do not require a Working with Children check. It can therefore be reasonably expected that there are likely to be student placements available that do not require a Working with Children clearance.

There are many reasons for a person not being able to get a positive Working with Children notice, but these people might still be suitable to work in human services, which is much broader than the regulated activities covered by Working with Children laws. Not being eligible for a Working with Children check does not necessarily mean that a person has committed offences involving children, as all criminal history is taken into account. Working with Children screening takes into account convictions, spent convictions, convictions as a juvenile, charges that have not been proven, reports to child protection, and police intelligence about a wide range of offences—it is not just about child-related offences.

It is unclear why Australian universities have imposed broad Working with Children check requirements when it is not necessarily a barrier to employment in human services. There may be a belief that agencies will not accept students who do not have Working with Children clearance or it may be a values stance that people with a certain type of criminal history are unsuitable to work in human services, that they pose an unacceptable risk to vulnerable persons, or that they lack desired personal qualities. It is important to note that policies are generally written by schools or faculties within universities. Blanket policies are widely applied to all programs within a school or faculty. This can lead to a limited capacity for social work field placement staff and educators to influence these policies. The blanket application by most Australian universities requiring all social work students to have a current Working with Children check (Young et al., Citation2019) is not in alignment with the legislation, nor does it appear to be supported by the prevailing employment market in Queensland. Aligning the use of Working with Children checks for student placements with the legislation will deliver a more inclusive and positive experience for both prospective and current students. It will also enhance consistency between social work education and social work values. Social work as a profession values inclusion, diversity, and life experience (Hughes et al., Citation2016). The Australian Association of Social Workers’ (Citation2020) ethical principles include “respect for persons”, which relates to dignity, human rights, and doing no harm; as well as “social justice”, which includes promoting policies and practices that uphold human rights, acting to reduce barriers, and advocating change to systems that are unjust. Excluding or discouraging students from studying social work or engaging in field work because of criminal history if not required under legislation contradicts what social work stands for (Apaitia-Vague et al., Citation2011).

It is important that admission processes involve ethical decision making, and risk to agencies and service users must be also considered when allowing a social worker into the profession (Cowburn & Nelson, Citation2008). Accountable practice requires clear ethical thinking to inform decisions about admitting students with a criminal history into social work education (Cowburn & Nelson, Citation2008). Admission policies and processes that are punitive and invasive can have a negative impact on potential students, whereas supportive, less intrusive policies explaining the impact a criminal history may have on the availability of field placement and employment are strengths based and rooted in self-determination (Vliek, Citation2018). Universities making Working with Children checks a requirement for a course, even when not required to do so by law or by placement agencies, may be a barrier to education that is neither necessary nor fair. Therefore, it may be deemed unnecessary and possibly unethical to use Working with Children checks as a precondition to studying at university. It is important that these checks only be used for the intended purpose—as a precondition to working in specified child-related fields.

In the role taken on by universities as gatekeepers, educators can observe students, and there are university policies such as inability to complete relevant course components and academic misconduct. Students can be interviewed and matched with appropriate placements and agencies to mitigate risk. Since many human services organisations do not require a Working with Children check for advertised positions, agency requirements is not a sufficient reason to require all social work students to have a current Working with Children check.

Any perception that the majority of human services organisations require Working with Children checks was not supported by the current study. Based on the jobs analysed for the purpose of this paper, most nonregulated positions did not require a Working with Children check. Our results were similar to that of the study mentioned earlier, surveying 100 field directors in the United States, where respondents stated that approximately half of their placement agencies required criminal history checks (Dottin, Citation2018). As many social work roles do not involve direct services to children, this finding suggests that there are likely to be sufficient potential roles available to the small number of students who are unable to obtain a Working with Children check.

Limitations

The current study provided a snapshot of jobs advertised online. Jobs that did not specify whether a police, disability worker, or Working with Children check was required were excluded from the data due to insufficient information. For numerous positions it was unclear whether service provision included children, and these were also excluded. Both of these groups were categorised as “unknown”. Support workers were the most highly represented in this category, with the majority not specifying whether the job involved services to clients under 18 years of age. A significant number of these positions did require a Working with Children check, and this could alter the data for nonregulated positions requiring a Working with Children check. Although the sample of position descriptions analysed was relatively small, the demonstrated consistency of the data across the weeks indicated a sufficient sample for analysis. The position descriptions used in the current analysis were for paid employment and may differ somewhat from roles available for social work student placements. However, as the purpose of field placement for students is employment preparation, the jobs are likely to be similar. Missing from research to date is an exact understanding of the reasoning behind why universities are applying blanket Working with Children checks for social work students. The present paper has highlighted that human services organisations do not have the same requirement of staff. Indeed, there are nonregulated jobs available to people who do not have or are not able to acquire a Working with Children check. Further research to explore why these checks have become an essential requirement for social work students in Australian universities will add valuable insight.

Conclusion

The present study has identified that although there may be challenges in finding field placement positions for students without a Working with Children check, more than half of the nonregulated “Community Services and Development” jobs listed online did not require this check. Therefore, it is reasonable to conclude that sufficient placement positions are likely to be available for a small number of students who are unable to gain Working with Children clearance. Requiring all students to have a Working with Children check is not the right strategy to screen out students or to manage risk to vulnerable service users. The policy of nearly all Australian universities that requires social work students to hold a positive Working with Children check does not align with social work principles of inclusivity or diversity, nor is it considerate of lived experience. Therefore, a challenge for social work educators is to ensure university decision-makers understand the unfair and unwarranted consequences of such requirements.

People who are not eligible for Working with Children clearance are able to operate successfully as professionals in many sectors of the human services industry. Rehabilitation from past criminal convictions need to be recognised as possible and positive, and it is important that they are facilitated by social work educators (amongst others). Many social work and human services employers do not prohibit people with a criminal record from entering or remaining in the profession, and it is not appropriate for students to face these generalised barriers when considering social work education. It is important for universities to ensure they implement ethical policies and procedures that are in alignment with relevant legislation and professional bodies. A commitment to human rights and nondiscrimination means that Working with Children checks need to be applied properly, but not extended beyond their purpose. Applying Working with Children check requirements to social work students, regardless of whether they seek a placement providing services to children, is inaccurate and may be discriminatory.

Supplemental Material

Download MS Excel (12.9 KB)Disclosure Statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

References

- Apaitia-Vague, T., Pitt, L., & Younger, D. (2011). ‘Fit and proper’ and fieldwork: A dilemma for social work educators? Aotearoa New Zealand Social Work, 23(4), 55–64. https://doi.org/10.11157/anzswj-vol23iss4id151

- Australian Association of Social Workers. (2020). Code of ethics. https://www.aasw.asn.au/document/item/1201

- Australian Human Rights Commission. (n.d.). Quick guide: Criminal record. https://humanrights.gov.au/quick-guide/12003

- Australian Institute of Health & Welfare. (2014). Prisoner health services in Australia 2012. https://www.aihw.gov.au/reports/prisoners/prisoner-health-services-in-australia-2012

- Barrenger, S. L., Hamovitch, E. K., & Rothman, M. R. (2019). Enacting lived experiences: Peer specialists with criminal justice histories. Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal, 42(1), 9–16. https://doi.org/10.1037/prj0000327

- Blue Card Services. (2020). The blue card system explained. https://www.qld.gov.au/law/laws-regulated-industries-and-accountability/queensland-laws-and-regulations/regulated-industries-and-licensing/blue-card/system/system-explained

- Bramley, S., Norrie, C., & Manthorpe, J. (2021). Current practices and the potential for individuals with criminal records to gain qualifications or employment within social work: A scoping review. Social Work Education, 40(4), 552–568. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2019.1699912

- Child Family Community Australia. (2021). Pre-employment screening: Working with children and police checks [Resource sheet]. https://aifs.gov.au/cfca/sites/default/files/publication-documents/2106_pre-employment_screening_resource_sheet.pdf

- Cowburn, M., & Nelson, P. (2008). Safe recruitment, social justice, and ethical practice: Should people who have criminal convictions be allowed to train as social workers? Social Work Education, 27(3), 293–306. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470701380394

- Crisp, B. R., & Gillingham, P. (2008). Some of my students are prisoners: Issues and dilemmas for social work educators. Social Work Education, 27(3), 307–317. https://doi.org/10.1080/02615470701380360

- Curran, L., Sanchez Mayers, R., DiMarcantonio, L., & Fulghum, F. H. (2020, October 1). MSW programs’ admissions policies regarding applicants with histories of criminal justice involvement. Journal of Social Work Education, 56(4), 721–733. https://doi.org/10.1080/10437797.2019.1661903

- Dottin, C. D. (2018). Admission of master’s degree students with criminal backgrounds: Implications for field directors. Field Educator, 8(1), 1–17.

- Duvnjak, A., Stewart, V., Young, P., & Turvey, L. (2021). How does lived experience of incarceration impact upon the helping process in social work practice?: A scoping review. The British Journal of Social Work, https://doi.org/10.1093/bjsw/bcaa242

- Ellem, K., & Richards, K. (2018). Police contact with young people with cognitive disabilities: Perceptions of procedural (in)justice. Youth Justice, 18(3), 230–247. https://doi.org/10.1177/1473225418794357

- Fox, J. (2020). Perspectives of experts-by-experience: An exploration of lived experience involvement in social work education. Social Work Education, https://doi.org/10.1080/02615479.2020.1861244

- Hughes, C., McNabb, D., Ashley, P., McKechnie, R., & Gremillion, H. (2016). Selection of social work students: A literature review of selection criteria and process effectiveness. Advances in Social Work and Welfare Education, 18(2), 94–106.

- Johnson, R. M., Alvarado, R. E., & Rosinger, K. O. (2021). What's the “problem” of considering criminal history in college admissions? A critical analysis of “ban the box” policies in Louisiana and Maryland. The Journal of Higher Education, 92(5), 704–734. https://doi.org/10.1080/00221546.2020.1870849

- Krieg, A. S., Guthrie, J. A., Levy, M. H., & Segal, L. (2016). “Good kid, mad system”: The role for health in reforming justice for vulnerable communities. Medical Journal of Australia, 204(5), 177–179. https://doi.org/10.5694/mja15.00917

- Lawright. (2019). Submission to Inquiry into the Working with Children (Risk Management and Screening) and Other Legislation Amendment Bill 2018 and the Working with Children Legislation (Indigenous Communities) Amendment Bill 2018. Queensland Parliament Education, Employment and Small Business Committee. https://documents.parliament.qld.gov.au/com/EESBC-92D1/RN121356PW-E88D/trns-16Jan2019-ph.pdf

- Menzies, K. (2019). Understanding the Australian Aboriginal experience of collective, historical and intergenerational trauma. International Social Work, 62(6), 1522–1534. https://doi.org/10.1177/0020872819870585

- Simpson, R. (1998). Initial responses to the wood royal commission report on paedophilia. NSW Parliamentary Library. https://www.parliament.nsw.gov.au/researchpapers/Documents/initial-responses-to-the-wood-royal-commission-r/08-98.pdf

- Vliek, A. S. (2018). Examining the impact of a criminal background in social work education [Doctoral dissertation]. Western Michigan University. https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/dissertations/3210

- Young, P., Tilbury, C., & Hemy, M. (2019). Child-related criminal history screening and social work education in Australia. Australian Social Work, 72(2), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1080/0312407X.2018.1555268