ABSTRACT

The aim of this article is to offer an approach that can be used to develop Decolonial Critical Awareness (CDA) and Decolonial Critical Reflection (CDR) in student language teachers at post-Primary level as part of their Initial Teacher Education (ITE). The article contextualises the rationale for such provision in ITE programmes in the wider debates related to the decolonisation of curricula, especially language curricula, in Higher Education. It also offers a view of language education policy in the Irish context when viewed through a decolonising lens arguing that CDA and CDR help develop skills, knowledge and values in student teachers to develop their identities as agents of change. The views of the student teachers who engaged with the approach show that while effective in fostering decolonial awareness, wider systemic barriers prevent them from feeling like they can instigate real change. The article concludes by emphasising the importance of this newly emerging area of research at post-Primary level and the need for further similar contributions in the Irish context.

1. Introduction: decolonising education?

Since 2015, as reported in Shain (Citation2021, 747–751), the resurgence in student activism globally, influenced by wider socio-political movements such as Black Lives Matter, have bought to bear the legacies of colonialism and coloniality in educational institutions. Some educational institutions have adopted a decolonisation agenda in response to these student-led campaigns, asking for instance, ‘Why isn’t my Professor Black?’ and ‘Why is my Curriculum White?’ (Peters Citation2015). In its widest sense, decolonisation is a process of deconstruction that seeks to bring about the ‘repatriation of Indigenous land and life’ (Tuck and Yang Citation2012), to show how colonialism, empire and racism shape the contemporary world and to reimagine the ways in which these forces are viewed (Bhambra, Delia Gebrial, and Nisancioglu Citation2018, 2). The sphere of education – especially in liberal, meritocratic societies – in the contemporary world is one area that has garnered much interest from scholars who seek to uncover the inequalities that exist between advantaged and disadvantaged groups (Shain Citation2021, 731): particularly between those affected by colonisation and coloniality (see Freire Citation2000; Emejulu Citation2018; Williams, Clark, and Sevenzo Citation2018; Lushaba Citation2018).

According to Stein and Andreotti (Citation2017, 4), the decolonisation of education encompasses several core processes such as the redistribution of resources within universities to empower oppressed students and staff; the dismantling of institutional structures so that they can be rebuilt to be more democratic; and, greater representation of those from Indigenous, racialised and low-income backgrounds in educational institutions. A further feature of decolonisation also includes the decolonisation of curricula and pedagogical practices. The latter seeks to deconstruct knowledge (what is taught and learnt) and processes of knowledge production (how learners learn). To achieve this, the hierarchical structures of race, gender heteropatriarchy and class, that codify the nation (Peters, Citation2014 , 643), must be recognised and undone (Mignolo and Walsh Citation2018, 2) to make marginalised peoples, their knowledge, and ways of life more visible to others as well as to themselves (Ford and Santos Citation2022).

Needless to say, this process is one that should be unsettling for all those involved (Tuck and Yang Citation2012, 9), as it requires us to not only reflect on the societies and systems that exist but to engage in inward self-reflection to recognise how hierarchical structures are perpetuated by those in power. However, over the course of the last decade, decolonisation has instead become a buzzword employed by educational institutions to show that they are listening to the student demands (Ibrahim, Citation2010, 495). One area of focus for institutions has been curriculum diversification. Student protests in Bristol by secondary school students in 2020 are a clear example of this type of pressure, which let to a commitment from school leaders to decolonise the English Literature and History schemes of learning (see Grubb Citation2020). This case exemplifies what Shaine (Citation2021, 751) describes as ‘draw[ing] attention to the Eurocentrism that lies at the heart of Western education systems’. However, based on the definition cited above from Tuck and Yang (Citation2012), the decentring of Eurocentric curricula, as in the Bristol case, is perhaps not a true example of decolonisation.

The (over-)focus on curricula from educational institutions, particularly at Third-level, has led to some dissension from decolonisation scholars who have been highly critical of the way in which the term has been appropriated by institutions as a marker of their newly found inclusivity. Tuck and Yang (Citation2012, 1), for instance, see the current moves to decolonise educational institutions as a metaphor for ‘social justice, critical methodologies or approaches that decentre settler perspectives’, which, in turn, attempt to reconcile the guilt and complicity of the colonial settler rather than being about challenging and dismantling power structures. Similarly, Dr Nayantara Sheoran Appleton (Citation2019), a Senior Lecturer at the Victoria University of Wellington, Aotearoa New Zealand, labels such attempts to decolonise as ‘hollow’, ‘opportunistic’, and ‘sloppy’, which ultimately do ‘a disservice to the amazing indigenous scholarship and activist work that is targeting power structures’. Instead, she suggests that rather than talking about wholesale decolonisation at the level of the institution, educators should focus more on diversifying curricula, digressing from the cannon, decentring knowledge and knowledge production, devaluing hierarchies and diminishing some voices while magnifying others (emphasis offered by Sheoran Appleton). This allows for anti-colonial, post-colonial and de-colonial work to take place while also remaining honest about what can be achieved.

For this author, the development of attitudes and mindsets that can support such work, as advocated by Buka, Matiwane-Mcengwa, and Molepo (Citation2017, 99) should begin during the formative years of Initial Teacher Education (ITE), during which time educators should be given the space to grow and expand their their knowledge and skills to enable them to critically reflect on the diversification and decentring of curricula and associated pedagogical practices. To respond to this need, this article describes an approach that can be employed by all those involved in ITE to develop such skills and knowledge; specifically in this case, student teachers enrolled in the Postgraduate Masters in Education (PME) at a third-level institution in Ireland and their ITE facilitators. The model seeks to cultivate Critical Decolonial Awareness (CDA), a model which aims to empower, in this case, student language teachers to be informed, critically reflective agents of change.

2. Recent curricular reform in languages education in Ireland: a decolonial critique

Research interest in decolonisation scholarship related to the field of language education is growing as attested by the sharp rise in related research outputs since 2017Footnote1. Ford and Santos (Citation2022) suggest that growth in this area is due to the unique position in which language teachers and academics find themselves ‘to unpick how knowledge is selected or disregarded, disseminated and re-inscribed at the intersections of multiple languages and linguistic varieties’. Such a position also allows language educator to design culturally sensitive curricula and pedagogies that act as a counter-narrative, mediating the histories and intersectional social identities of peoples from the Global South (Foulis Citation2022). In the Irish context, critically reflecting on recent developments in languages education through a decolonisation lens demonstrates the importance of growing and developing these skills in student language teachers so that they can critically engage in an informed way with national curriculum policy. Two features of language education policy that are worth of discussion in this arena and could be potential areas of discussion with student language teachers relate to the nomenclature used to refer to linguistic varieties and communities as well as what the decentring of pedagogical practices might look like in the languages classroom.

2.1 Nomenclature

The language naming/labelling practices that exist to describe linguistic communities and cultures are problematic when viewed through a decolonial lens, especially in relation to the naming of ‘subjects’ or disciplines. García (Citation2019, 157) shows how language education in schools has historically adopted a nomenclature that reinforces historical colonial norms such as the link between named languages, nation-states, and particular social groups, i.e. Spanish is spoken in Spain by Spaniards.

Putting aside the issues associated with the term ‘language’ itself (for a summary of the issues, see Schilling-Estes Citation2006, 311–341), the use of the adjective ‘modern’ that often prefaces ‘language’ to describe a distinct area of the school curriculum is problematic: for example, Modern Foreign Languages or MFL. What distinguishes a language that is ‘modern’ from one that is not? From a postcolonial perspective, the label reinforces what Quijano and Ennis (Citation2020, 540) refer to as the coloniality of knowledge and power. Here, ‘modernity’, characterised as the hegemonic colonial languages and epistemologies of Europe, clandestinely perpetuates the legacy of colonialism. In fact, the label ‘modern’ creates a stark, pejorative contrast between Eurocentric knowledge and production (i.e. the modern) and that of the Other (i.e. the ‘non-modern’). In educational systems like Ireland that seek to promote equity within diversity, the use of such systemic inequalities and hierarchies whether in the form of knowledge (i.e. curricula) or practices (i.e. teaching, learning and assessment) must be systematically challenged and critiqued not only by policymakers but also by educators in the classroom.

A second critique of the term MFL, especially in the Irish context, relates to the use of ‘foreign’. Foreign language, full-course qualifications under the banner of the Established Leaving Certificate at Senior Cycle (ages 16-18) have not always accounted for first or heritage language speakers. A heritage language is defined as a minority immigrant or indigenous language(s) acquired in the home or that speakers have some cultural connection to, and which is learnt prior to or alongside the acquisition of a majority language (van Deusen-Scholl Citation2003). Hitherto, for these students to develop and/or maintain their heritage language skills, they are left with no option but to take a qualification designed for non-mother-tongue speakers. Admittedly, the provision for heritage languages has improved significantly in Ireland since 2017, particularly for speakers of Polish, Lithuanian and Portuguese (see below), who make up a large proportion of the population (see CSO Citation2018); nonetheless, more needs to be done for Lithuanian, Romanian and Latvian speakers which are individually higher in number than those that speak PortugueseFootnote2.

A final example relates to the use of the term ‘target language community’ in the Senior Cycle foreign languages syllabi. The use of the singular rather than the plural ‘communities’ reinforces the colonial notion that there is ‘one’ single community that speak the language under study: typically, the community in continental Europe. While some discretion in this case given that these syllabi are over 20 years old and currently being updated under general Senior Cycle reform (see NCCA Citation2022), similar naming practices continue to be seen in the newer Junior Cycle MFL specifications, which were introduced in 2017. The learning outcomes explicitly promote the development of sociocultural knowledge related to cultures and countries (in the plural) whereas the rest of the document refers to ‘target language’ (in the singular). The use of the singular in this case suggests that each language variety studied is homogenous. Moreover, the use of ‘country/ies’ rather than perhaps ‘communities’ also reinforces the colonial notion of one nation, one language and perhaps fails to recognise indigenous, diasporic, displaced or migrant communities and subsequent generations of migrants (e.g. Latinx communities in the United States).

Nonetheless, there seems to be a growing awareness amongst policymakers of the issues related to such naming practices in terms of the way in which they hierarchise certain linguistic varieties above others. For example, the main curricular languages or Modern Foreign Languages (MFL – French, Spanish, German and Italian) have long existed in stark contrast to Non-curricular Languages (e.g. languages of the European Union for native speakers) and Lesser-taught Languages (e.g. Japanese, Chinese, Russian).Footnote3 However, in contrast, the Teaching Council of Ireland’s recent reform of teacher registration requirements in language-based subjects attests a departure from differentiating languages in this way by registering all language teachers under the same banner (Teaching Council of Ireland Citation2022, 14). It should also be noted that the inclusion of Russian, Japanese, Chinese and Arabic recognises planned future developments to rationalise, streamline and reform language curricula in Ireland. This reform is also particularly important for those that teach heritage languages. For the first time, the qualifications of heritage language teachers, often immigrants themselves, are recognised as equivalent to those of French, Spanish, German, and Italian teachers. Consequently, they are afforded the same professional and employment rights, remuneration and access to professional development as their counterparts if they satisfy Teaching Council requirements. Whilst there are still prohibitive hurdles for such teachers (including the costs and administrative burdens associated with registration), it does represent a positive step forward.

2.2 Decentred practices

As discussed previously, the decentring of curricula as part of the wider work of decolonising education must not be a ‘domesticating’ process where references to postcolonial languages, peoples, cultures and societies are included simply to satisfy Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) initiatives (Tuck and Yang Citation2012, 3). In truth, such ‘EDI-washing’ (Ford and Santos Citation2022) does very little to alter the structures that perpetuate marginalisation. In relation to language education, Kramsch (Citation2019, 50) like Shain (Citation2021), sees the decentring process as one in which the past histories of nations and colonies associated with the languages under instruction (usually those from Western Europe) are decoupled from their Eurocentric focus and where learners engage more directly with members of postcolonial communities (69). In practice, this could involve greater engagement with other language varieties (for example, the Spanish of Central or Latin America, the Caribbean or West Africa) on a phonological or lexical level (e.g. common patterns of pronunciation, common lexical equivalents for nouns or adjectives) or involvement in activities such as eTwinning but with areas in the Global South.Footnote4

Further diversification of language teaching practices and pedagogies that seek to democratise language classrooms can also play an important role in decentring student learning. One way in which this can be achieved is through the reconceptualisation of the classroom as a plurilingual space; one that fosters translanguaging practices and rejects the monolith of monolingualism (Panagiotopoulou, Rosen, and Strykala Citation2020, 166). In such spaces, language encounters between speakers/learners are centred around the individuals involved in the interaction. Through the deconstruction of the notion of ‘one foreign language-one classroom’, students’ entire linguistic repertoires are recognised, valued, and employed to support the teaching and learning of languages leading to a greater sense of student-centredness and acceptance.

The recent publication of the Language and Languages in the Primary School: Some Guidelines for Teachers (Little and Kirwan Citation2021) represents further efforts to demonstrate to primary schools in very practical ways how the linguistic landscapes (and practices) (Gorter Citation2006, 6) of their individual institutions can be democratised using pluricultural pedagogy. Indeed, by providing affordances to the pluricultural dimension of primary school, and by teaching languages in an integrated way, the teaching and learning of English, Irish and other languages can be mutually supported. While it is unlikely that the intention of this resource is to decolonise the curriculum, it does promote some of the decolonising processes cited by Sheoran Appleton (Citation2019) and Criser and Knott (Citation2019, 156) such as magnifying minority or marginalised voices and devaluing monolingual ideology. These practices subsequently support the deconstruction of hierarchies between the language of instruction, the languages being learnt and heritage languages present in the classroom, as well as supporting, to some degree, the diversification of the curriculum. What Little and Kirwan are promoting here is not simply a tokenistic nod to interculturalism, but rather a systematic shift in the way that languages are used and taught across the school and curriculum, as exemplified by the case study of Kirwan’s former primary school that forms the basis of the document.

For some practising teachers, the development of broader cultural, social, and linguistic competencies and knowledges, as well as the culturally sensitive pedagogies and approaches that aid the decentring of curricula, might seem like a challenging and unending task for a busy professional. However, it is important to remind ourselves that it is a process through which competencies are situationally developed in a responsive way rather than acquired to be able to demonstrate knowledge mastery. This form of professional development should be seen, therefore, as ‘a commitment and active engagement in a lifelong process that individuals enter into on an ongoing basis with […] communities, colleagues and with themselves’ (Tervalon and Murray-García Citation1998, 118). Foulis (Citation2022) sees this process as a development of ‘cultural humility’ rather than the acquisition of ‘cultural competence’, a personal-professional disposition that shows commitment to lifelong learning, to listening to different experiences attentively, to acknowledging power imbalances and asymmetries in classrooms and beyond and to examining one’s own biases. This author would also argue that ‘cultural humility’ is not only a disposition that educators should develop but one that all those present in classrooms should engage with meaningfully.

Recent developments in the Irish post-Primary curriculum landscape that support the development of cultural humility are very promising in this regard. Whilst not explicitly mentioning decolonisation, Statement of Learning 16 of the Junior Cycle curriculum states that ‘the student appreciates and respects how diverse values, beliefs and traditions have contributed to the communities and culture in which she/he lives’ (NCCA Citation2017, 6). Furthermore, a subset of the learning outcomes (Strand 3) contained within the MFL specification refers to the development of socio-cultural knowledge and intercultural awareness, which deals with learning about people, places, history (although not ‘histories’), traditions, customs, and behaviours which can also be achieved through careful reflective comparisons with their own culture (NCCA Citation2017, 17). Also, it should be acknowledged that the recent development of full Senior Cycle specifications aimed at heritage language speakers of Polish, Lithuanian and Portuguese (qualifications which are equivalent to existing ‘foreign’ language qualifications) are based on a more plurilingual approach in recognition of the plurilingual language repertoires and languaging practices of younger speakers who live in communities in Ireland but also have connections to other communities abroad (NCCA Citation2020, 11)Footnote5.

This brief analysis of linguistic nomenclature and the decentring of practice, principally from monolingual and monocultural ideology, demonstrates the value that informed critical reflection can have in supporting teachers to understand how educational policy, at least in the language education context, perpetuate the legacies of colonial ideology. It is clear that new language curriculum policy and widely publicised pedagogical approaches in Ireland seek to promote, to a degree, greater inclusivity, to value diversity, and to magnify the voices of marginalised peoples and comunities. These steps could be interpreted as the first towards decentring knowledge (curriculum) and knowledge production (pedagogy); however, such steps are small and slow given the current pace of curriculum change. Therefore, to combat this, particularly at a policy level, one way in which education systems in the Global North can take their first steps towards decolonising their curricula and practices, is by providing teachers with the skills and knowledge that allow them to challenge these issues in their own classrooms. The remainder of this article will present an approach that was employed to support language teachers in achieving this objective during their ITE.

3. Developing critical decolonial awareness in student teachers of language

Tiffin (Citation1987, 17) describes decolonisation as a ‘process, not arrival’ wherein hegemonic systems are subverted and dismantled by peripheral ontologies and epistemologies. The agents responsible for this subversion are situated in a Third Space, a position that Tiffin describes as being ‘privileged’, where shifting and opposing ideologies are neither unified nor fixed (Bhabha Citation1984). As previously mentioned, the space in which language educators exist between different linguistic varieties, cultures and communities is unique and, consequently, allows them to offer ‘counter-discursive rather than homologous practices and knowledge’ inherent to the Eurocentric narrative (Tiffin Citation1987, 18). The two-stage approach proposed here is designed to be facilitated during ITE and is based on the tenets of ‘inquiry-orientated teacher education’ through which student teachers develop the ‘skill to analyse what they are doing in terms of its effect upon children, schools and society’ (Zeichner Citation1983, 6). Furthermore, in line with the principles of cultural humility highlighted above, teacher educators who choose to use the framework with their student teachers, must also envision themselves as a participant in the process and reflect critically on their own agency, biases and position as an ITE facilitator thus breaking down the traditional hierarchies that exist between teacher trainer and student teacher.

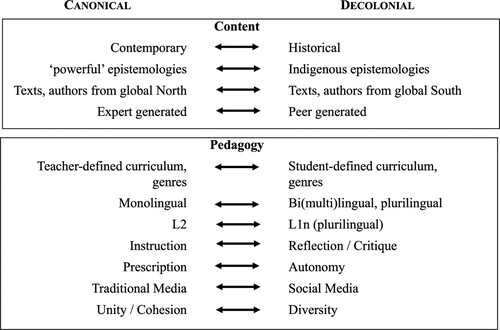

The first stage of the model focuses on the development of Critical Decolonial Awareness (CDA). CDA was initially developed by Hornberger (Citation1989) as a theorisation of biliteracy development and reimagined by Carstens (Citation2014) within the context of decolonised languages education. Carstens’ model is divided into the themes of ‘Content’ and ‘Pedagogy’ under which canonical and decolonial features of each theme are placed in dichotomous opposition along individual continua (see ).

Figure 1. Canonical and decolonial features of content and pedagogy (based on Carstens, Citation2014).

Several of the features of decolonial pedagogy are already interwoven into the specifications of school programmes such as the reduction in prescriptive curriculum content in the new Junior Cycle specifications to allow teachers to design curricula centred around the students in their individual professional contexts. However, others such as the monolingual-multilingual continuum, reflecting the multilingual nature of our classrooms, may not be as equally widespread in practice. This starting point is useful for initiating critical discussions with student language teachers, especially outside of language-based subjects such as Mathematics or Science. The first stage of CDA, therefore, centres on raising awareness of these dichotomies to encourage discussions about the ‘content’ that is delivered, how it reflects and responds to the learning needs of the Self (i.e. students that represent the majority), the Other (i.e. those on the margins), and the ‘pedagogies’ that employed to deliver it. Even in supposed homogenous classrooms where ethnic or linguistic diversity is less present or apparent, reflecting on the opportunities and challenges confronted by learners who exist on the margins of society is key to the general development of cultural humility in both students and teachers.

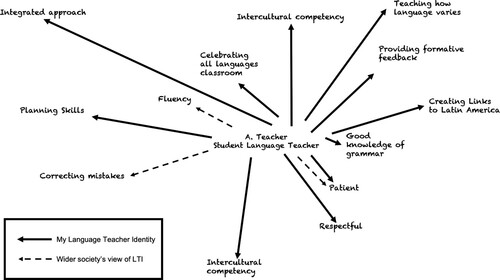

During the second stage of CDA development, student language teachers and facilitators develop an auto-ethnographical understanding of their own identities as language teachers as well as that of their colleagues and other professionals with whom they interact. Language Teacher Identities (LTIs) are highly complex and can be viewed from multiple perspectives: cognitive, social, emotional, ideological, and historical (see Barkhuizen Citation2017, 4). In a tutorial-type environment, reflection opportunities focused on LTIs can be structured using the method of graphical Identity Charts (see Facing History and ourselves Citation2022). This flexible approach invites participants to write down words or short phrases that they would personally use to describe their LTIs as well as those that exist in discourse across society. Words appearing towards the centre part of the diagram are those that they feel are more central to their LTIs (for example, see ). Participants then compare their Identity Charts with peers and can either add new descriptions that they had not previously recorded as well as discuss/critique others, particularly those imposed by society.

The advantage of this methodological approach is that it reveals how LTIs (as with any Bordieuan understanding of identity and habitus) evolve because of social interactions with other professionals, including the ITE facilitator (i.e. teacher educator). Similarly, when discussed in the context of Carstens’ model and CDA, it helps participants to develop an understanding of the broad nature of their LTIs through a decolonial lens. Therefore, in developing CDA, participants are encouraged to critique and reimagine not only their preconceived idea of LTIs based on their own teaching experiences but also to challenge and question the identities placed on them by wider society, including by other teachers. In this sense, they come to see how they inhabit a Third Space wherein LTIs are not fixed or complete entities but fragmented spaces (re)negotiating further fragmentation. Furthermore, it demonstrates to less-experienced teachers how they can continually deconstruct and renegotiate aspects of their own LTIs on their own terms, such as recognising their agency as professionals who can critique and interrogate teaching, learning and curricula.

The final stage of CDA development focuses on demonstrating to participants how as language educators they can also act as agents of change; in this case, by decentring their own teaching and learning content and practices. In this case, the theoretical framework of Transformative Action, based on the research of Jemal and Bussey (Citation2018), is particularly useful. Transformative Action was initially developed to support community-based practitioners in social work to understand and combat systemic inequality. It is based on the premise that community actors operate on a cline on which their actions are either ‘destructive’ (i.e. perpetuate inequality), ‘avoidant’ (i.e. inactive in relation to inequality) or ‘critical’ (e.g. they take assertive action that addresses inequity). When applied to the development of CDA, ‘inequality’ can be reinterpreted as perpetuating a canonical, monolingual, monocultural narrative in terms of the content delivered in the classroom and adopting similarly ‘unequal’ pedagogies that prescribe and instruct. Developing student language teachers’ and facilitators’ critical awareness in this sense supports their transition to becoming transformative actors, whose role is to harness, teach, critique, and embrace the ‘whole’ multilingual/plurilingual/multicultural/pluricultural truth of the language classroom as a representation of the realities of wider society. Transformative action, therefore, should be viewed as a ‘bottom-up’ approach operating within the classroom or school context, undertaken by teachers and local curriculum leaders, to counter the canonical narratives perpetuated through the education system.

To conclude this section, the overarching aim this proposal is to support the development of the critical skills that student language teachers can employ to interrogate their practice, classroom space, institutional contexts, and the wider educational system. Simultaneously, it also aims to demonstrate how their own LTIs, as well as those of their peers and colleagues, are complex, multifaceted and ever-evolving due to ongoing interactions within the professional contexts/networks that they inhabit. As such, they occupy a continually deconstructed and (re)negotiated Third Space within which they can be agentive in shaping and renegotiating their identities. Consequently, this demonstrates to them how have the potential to be agents of change who can instigate transformative actions in their classrooms to foster greater equity, diversity, acceptance, and inclusion. The development of CDA is only the initial stage in this process; the second requires critical reflection of their own practice to demonstrate the possibilities of transformative action.

4. CDA leading to critical decolonial reflection (CDR)

Over the last decade, the Teaching Council has placed significant emphasis on the importance of professional reflection for teacher development. This is seen particularly in three key policy frameworks that support career-long teacher education; namely, Céim: Standards for Initial Teacher Education (TCI Citation2020), Droichead: The Integrated Professional Induction Framework (TCI Citation2017) and Cosán: Framework for Teachers’ Learning (TCI Citation2016). Consequently, to ensure that the development of CDA has an effective impact on learning and teaching, reflective practice must form part of this process. Critical Decolonial Reflection (CDR) is envisaged as a core practice in the process of decolonisation and, particularly, in decolonised language education (Varghese et al. Citation2016). It should be stressed that a core tenet of CDR is that it is a participant-centred approach that invites us ‘to critically engage with issues that arise and find solutions through a process of exploration and critical reflection’. Indeed, this is a core tenet of Carstens’ decolonising model for the classroom. CDR, much like cultural humility, is also developmental in the sense that should take place regularly throughout our professional careers.

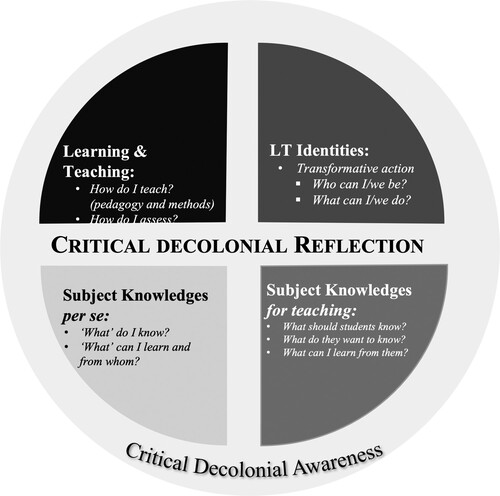

To support the development of CDR in student language teachers at this early stage of their professional careers, the following approach was developed (see ), focusing primarily on LTIs and transformative action, subject knowledge (both per se and for teaching) and learning and teaching. Before describing how the approach was enacted during ITE, some discussion will be dedicated to each of the quadrants in that constitute CDR.

The first quadrant in this model requires participants to reflect on their LTIs. Participants reflect both personally and collectively in terms of who they are and what they do but also who they can be and what they can do. In more tangible terms, this process asks student teachers to think about their role as transformative actors and whether they are perpetuating canonical ideas and practices or already adopting some elements of a decolonial approach. For example, a student teacher of Spanish might reflect on the teaching of greetings to first-year students and question whether teaching them only ‘Hola’ [Hello] and ‘Buenos días’ [Good Day] is a true reflection of the linguistic diversity of Hispanic peoples and other indigenous groups in the Hispanic world. By teaching other greetings from other parts of the Hispanic world participants not only make diversity visible but also open the door to allowing other multilingual students in their classrooms to share their own greetings in other languages to affirm their own minoritised identities. It is also envisaged that this process is solution-orientated; in this scenario, participants support each other by forming a community of practice, sharing ways in which they can begin the work of decolonisation to make them more inclusive, including sharing subject knowledge and lived experiences in the spirit of continuing professional learning.

The second quadrant of the CDR model encourages participants to reflect critically on their pedagogy, methods, and assessment practices from a decolonial perspective. Carstens’ model is particularly useful in this regard in helping participants to understand how to promote, for example, student autonomy and diversity, particularly in relation to the ways in which students might represent their learning. In this case, Universal Design for Learning (AHEAD Citation2021) and its associated framework is particularly fruitful to support the decolonisation of the classroom. From a linguistic perspective, this quadrant of the CDR encourages participants to think of different ways in which they can encourage their students to show their learning. For example, when describing their daily routine, pupils could be invited to write a narrative description or create a cartoon strip or a flow chart depending on which way they would prefer to demonstrate their learning. Indeed, when teaching daily routines, teachers should question whether the models of routines that they use in the target language to teach the vocabulary and structures should always be centred on Eurocentric traditions. It is these types of questions that participants could ask themselves when reflecting critically on their pedagogical approaches.

The final two quadrants relate to teacher subject knowledges. As termed by Herold (Citation2019, 488), the ‘what?’ of teacher subject knowledge (as opposed to the ‘how?’ it is acquired) is traditionally viewed as the sum of two interrelated parts: that is, subject knowledge per se and subject knowledge for teaching. A teacher then subsequently goes through a process of pedagogical transformation which involves, in simple terms, ‘taking what he or she understands and making it ready for effective instruction’ (Shulman Citation1987, 14). From a decolonial perspective, there are two important reflective processes that are required here. Firstly, student language teachers must reflect on their own existing subject knowledges. The plural is intentionally used here to reinforce the notion that there is not one definitive ‘knowledge’, but a multitude of different knowledges emanating from a multitude of varied experiences that are shaped through further professional interactions. Broadly speaking, within a language learning context, discussions might focus on the areas of communicative competence, sociocultural knowledge, and linguistic knowledge. Additionally, at this stage, participants should be invited to reflect on whether their own subject knowledges include the very peripheral epistemologies that any decolonial approach seeks to include and present as equal to epicentral knowledges from the Global North. As highlighted above, the new junior cycle Specifications for MFL and heritage languages illustrate that there is a need for teachers to incorporate this into their teaching so that they, in turn, can challenge pupils’ perceived knowledges of language and culture. Indeed, pupils themselves can also be valuable sources of knowledge, especially in multilingually diverse settings.

In relation to its implementation, there are several ways in which CDR can take place but, fundamentally, it should be dialogic process between all those who participate. On this occasion, participants (student teachers and facilitator) were split equally into four groups to focus on one of the quadrants outlined in . Each group reflected on the questions outlined in each quadrant as starting points and a scribe was elected to record key points from their discussions. After 10 min of discussion, the students were split into four further groups so that one participant from each of the initial groupings was present in the second grouping. Participants then relayed their discussions to the rest of their group. Approaching the discussion in this way allowed participants to reflect in greater depth on a single aspect of their practice.

The entire CDR process of questioning one’s own knowledge (and subsequently your own identity as a language educator) can be challenging, but it is important that it remains solution-orientated. By ensuring that CDR is undertaken in a socio-constructive setting participants will or can be encouraged to share ideas to overcome gaps in their knowledges. However, it is important to stress here that subject ‘mastery’ must not be the pursuit of these discussions. Indeed, ‘mastery’ as a term is analogous to decolonisation debates; that is, how can ‘full’ knowledges of languages and cultures ever being fully acquired, especially when they are constantly evolving through individual social interactions? Nonetheless, one of the dispositions fostered during discussions around CDR should be centred on the issue of questioning whether what educators know (and teach) is a true representation of the linguistic and cultural realities of different types of communities across the globe.

The second part of the CDR model relates to subject knowledge for teaching and invites student language teachers to consider what should be taught, how it should be taught and what knowledges students already possess from which everyone can learn. Indeed, at the post-Primary level, students range from pre-A1 to B1 level according to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages or CEFR (Council of Europe Citation2001), so their levels of communicative competency are intermediate at best by the age of 18-19. However, it should be stressed, that this measure of communicative competency is an average measure, as even the plurilingual principals underpinning the CEFR recognise that communicative competency is ‘uneven’ and different for every individual (Council of Europe Citation2017). Despite their lower competency levels, decolonising approaches such as decentring the curriculum are not impossible. Raising awareness of the realities of target languages and cultures through contact with other communities such as eTwinning (see above), school exchange or social media can provide insights into the lives of speakers from around the world. Also, interaction with age and stage-appropriate materials from the places where the language of instruction is spoken, including from communities in the Global South as well as other diasporic, dispersed or indigenous peoples, can also facilitate the development of this awareness. Pearson, a UK-based educational publisher, and the Association for Language Learning Decolonise Secondary MFL Special Interest Group in the UK have recently produced several age-appropriate materials under the project ‘Permission to Speak: Amplifying Marginalised Voices Through Languages’ for French, Spanish and German classrooms that illustrate how this can be achieved at post-Primary level (Pearson Citation2022). From a linguistic perspective, exposing students to different varieties of language, even if it is simply from a phonological perspective to allow students to perceive differences in pronunciation, is important in this regard. For example, some of the resources being created by the National Centre for Excellence for Language Pedagogy at the University of York incorporate speakers of other linguistic varieties of the language of instruction when teaching phonics to raise awareness of variation.

5. Reception of the model

During the academic year 2020-21, the CDA-CDR model was introduced to a group of 7 student language teachers at University College Cork enrolled in the Professional Masters in Education (PME) during their School Placement (SP) tutorial sessions. The group was chosen initially due to their interest in decolonising approaches that had emerged from earlier discussions in the year related to the lack of diversity in the Leaving Certificate Examination papers and the textbooks available. The development of CDA was undertaken over a 2-week period (including two 1-hour face-to-face tutorials) and then, subsequently, CDR formed part of our tutorial sessions for the remaining 3 weeks. After the 3-weeks had elapsed, an anonymous electronic feedback form was circulated to the group via Microsoft Forms, which invited them to reflect on the effect that discussing decolonial issues had had on their practice, if at all. Students were all provided with an information sheet and informed consent form prior to taking the survey in line with ethical procedures (Social Research Ethics Committee, University College Cork, Log No. 2022-203). Secondly, the survey sought to gather their personal views related to the advantages and challenges of adopting decolonial approaches in a post-Primary classroom in Ireland. All survey items required open-ended responses and no quantitative data was collected given the very small sample size, as it was felt that this would produce richer insights into the impact of the model. 25 min was set aside to complete the survey. Each respondent drew a non-identifiable pseudonym (i.e. Student 1) at random and responses were analysed thematically using computer-assisted qualitative analysis software (NVivo) by this author.

In response to the first question which simply asked students whether the 3 weeks focusing on the theme of decolonisation had impacted their practice, all 7 student teachers confirmed that they had become more self-aware of potential areas for development in their subject knowledge. For example:

Our discussions in tutorial suddenly reminded me of modules that I took during my second and fourth years on latin and central america [sic]. I should definitely bring some of that stuff into my teaching. Besides, it’s really interesting and I think my classes would like it. [Student 4]

I know very little about other Spanish-speaking countries. I didn’t even know about ecuatorial guinea [sic] was a previous Spanish colony, which makes me wonder what other gaps I have. [Student 2]

Last week, with my first-year Spanish class, we were talking about items in the classroom in a school. I printed off pictures of different classrooms from 6 different Spanish-speaking countries and got students to describe them using hay [there is/are, my italics] and no hay [there isn’t, my italics]. It was great because they then wanted to talk about the differences in English afterwards and showed how curious they are. [Student 2]

I used the materials recommended to us on teaching ‘c’ and ‘z’ sounds in Spanish as ‘th’ or ‘s’. I then played 4 or 5 weather forecasts from different Spanish-speaking countries and areas in Spain (we’d just covered weather again) and the class had to work out where they could be from. This worked really well because it developed their sociocultural knowledge and listening skills at the same time.

In responses to the second question in the survey, which asked how discussions in tutorial enhanced their CDR skills, 5 of the 7 students explicitly mentioned that they valued the opportunity to talk about their own subject knowledge, to learn and share with each other:

Some of our tutorial group, specially [sic] those that had visited or lived in Latin and Central America, knew so much more than me but and were very generous with it. They gave us lots of simple ideas of how we could make our teaching more diverse. [Student 7]

Before COVID, I had been to Peru and visited Machu Pichu. I had a picture on my phone of a sign at the train station in Spanish and Aymara. Another person in the group was doing travel with their TY class and thought it would be a great one to use for that. [Student 5]

Finally, one student explicitly mentioned in response to this question how the discussions around subject knowledge afforded greater meaning to the sociocultural learning outcomes in the Junior Cycle specification, moving the narrative beyond the traditional Eurocentric bias:

When it talks about communities and cultures in the plural, I often find this hard to apply because I know very little about the Spanish-speaking world. But, I did a project about Romani Gypsies in Spain on my Erasmus and I suppose that they are a more invisible community in Spain who are on the margins of society who should be included in what we do. So, when it talks about cultures, we can talk about cultures within cultures.

The third and fourth questions in the survey focused on the opportunities and challenges/barriers in adopting decolonial approaches in the classroom that they felt they faced. All students were invited to offer solutions to the challenges. Reflective responses to question 3 centred on 3 main themes. Firstly, decolonising approaches help to make language learning more ‘diverse’ [Student 3] and ‘more representative of the peoples and cultures that speak the language of the classroom’[Student 2]. Secondly, including decolonising elements ‘makes the content of lessons more engaging for students […] because they feel that they are learning something new’ [Student 6]. Finally, despite not having mentioned plurilingual or pluricultural approaches in their planning at any point, two students felt that considering planning through a decolonial lens, supported ‘our attempts to be more inclusive’ [Student 1] and ‘to promote more inclusion’ [Student 7].

Regarding the challenges of adopting decolonising approaches in their lesson, 5 of the students sometimes felt uncomfortable as agents of change or that logistically they were not able to instigate such change. For instance:

You have to remember that we are not permanent members of staff on placement. Our role is to ensure that we follow the plans (normally the textbook) so that if the class teacher comes back to take over then they can. [Student 3]

My co-operating teacher takes one of the four classes per week because it takes place on the day we’re in college. If I go off course too much then students won’t be prepared fully for the Christmas and Summer tests. [Student 4]

A second observation made by 6 of the participants was that the inclusion of decolonising approaches added to their workload, particularly from the point of view of their subject knowledge per se and subject knowledge for teaching. Student 3, for example, questioned: ‘how can I be “decolonial” if the length and breadth of my subject knowledge ais based on the culture and language of France?’. Student 5 also said ‘When I tried to use more inclusive language or culture in my lessons, I found that I was spending double the amount of time planning.’ As alluded to above, the process of decolonisation is not necessarily easy and, in fact, perhaps trying to take shortcuts runs the risk of paying lip service to decolonising approaches rather than initiating actual systemic change. Interestingly, one way that may help teachers with planning and preparation issues associated with this process and the concern to ensure that change is ‘real’ is through teacher-publisher collaboration. Students 1, 2 and 7 all mentioned how the textbooks that they use in class paint an unrealistic linguistic and cultural reality of the target language cultures with which they are engaging. One student, for instance, said: ‘Information about the Global South is just missing from the textbooks and resources we use’. The work of the publisher Pearson in the UK shows that there is an opportunity here for the same work to happen in Ireland. Additionally, perhaps teacher guides that accompany textbooks could also include more ideas on how to exploit plurilinguistic and pluricultural aspects of the content as and when they are used.

6. Conclusion and next steps

The aim of this article has been to present a two-stage approach that can be employed to develop Critical Decolonial Awareness (CDA) and Critical Decolonial Reflection (CDR) in student language teachers and ITE facilitators. The article also summarises some of the key points drawn from a short survey given to 7 student language teachers who engaged with the model over a 3-week period. The article also dedicated some discussion to issues related to the nomenclature and decentring practices in the Irish language learning policy that exemplify some of the discussions that might emerge through the development of CDA and CDR in the Irish context.

From the perspective of language curricula, planning and policy there have been positive changes, particularly in the new Junior Cycle. The equal status afforded to languages emerging from recent curricular reforms in this arena is worthy of note. Moreover, the equal status that the Teaching Council now places on curricular language teachers (i.e. French, Spanish, German and Italian) and the ‘new’ languages is also a very positive step forward, especially for heritage language pupils and teachers who exist on the periphery of society. To support these steps forward, through the development of CDA, student language teachers during their ITE should be encouraged to critique established learning outcomes through a decolonial lens to deconstruct and uncover what is meant by terms such as ‘cultures’, ‘communities’, ‘languages’ employed in the learning outcomes. This author has no specific evidence of how this is undertaken in other ITE programmes across Ireland but there is a need for further research, discussion and sharing of practice in this domain.

From the perspective of the impact of the approach, the feedback from the student language teachers involved in the study was valuable. Overall, the feedback illustrates that the model supported the development of the students’ decolonial practice, particularly from the perspective of awareness and early developing practice. They also show that dialogic interactions with their peers against the backdrop of CDA and CDR, particularly in relation to subject knowledges per se and for teaching, were valuable. However, much of their reflective contributions centred on the diversification of sociocultural and linguistic content and little comment was made about the decolonised pedagogical approaches cited in Carstens’ model. This is understandable given that ‘content’ is much more tangible than approaches / methodologies that often need to be observed or experienced for their pedagogical impact to be fully understood.

Some of the challenges that the student language teacher respondents cited when implementing decolonial approaches related to their unease at being potential agents of change because of a lack of agency in their SP contexts. Some respondents also cited workload as an issue and how the added focus on decolonising approaches contributed to this. It is difficult to mitigate these issues in the context of their ITE given the inherent nature of their status as students and the accompanying workload that this entails. However, as research undertaken by Heinz, Keane, and Foley (Citation2017, 19) shows, student teachers in Ireland indicate a strong personal commitment to teaching and are eager to engage intellectual and creatively with their expert subjects (24). Consequently, although they may not feel that they are in a position to engage fully in CDA and CDR at this stage, their awareness of decolonisation in the sphere of language education may be an area of future professional develop that they wish to revisit. Indeed, if student protest continues to oblige educational institutions to make changes to their practices and curriculum content, revisiting CDA and CDR might become a more pressing professional learning need in the short – to medium-term.

The approach proposed here only makes a small contribution to the wider debates related to the decolonisation of language education. With the reforms to Senior Cycle on the horizon, it seems as though the time is opportune for teaching and learning to be critically reviewed through various lenses including a decolonial one. Nonetheless, more research is still required into understanding how we envision and enact decolonisation in language teaching and learning at post-Primary level. Simultaneously, perhaps greater engagement between academia and publishers, like the case discussed here in the UK, is worth pursuing to help support teachers to decentre their teaching and learning. Most importantly, the voices of students, parents and a wider variety of teachers need to enter this discussion to inform our policy-making processes. Additionally, more collaboration and cooperation between ITE providers and government agencies (such as Post-Primary Languages Ireland) would help to raise awareness around the important role that such approaches could have in the development of pluricultural competence, sociocultural knowledge and, most importantly, cultural humility to foster greater acceptance of the Other across society. In truth, being able to affect such social change for the benefit of their pupils development and wider society appears to be a key desire for those entering the profession (Heinz, Keane, and Foley Citation2017, 24). ITE, in particular, must do more to support pre-service teachers to achieve this goal, particularly through the development of culturally responsive knowledge, skills and values (Hannigan, Faas, and Darmody Citation2022). The approach proposed in this article, although designed for student language teachers, is an example of how this challenge could be addressed in ITE in Ireland.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Craig Neville

Craig Neville is lecturer in education, PME tutor and early career researcher at University College Cork. He lectures in the areas of language teaching pedagogy and EAL provision predominantly in the post-Primary setting. Before embarking on a career in Initial Teacher Education, Craig was a teacher and senior leader of modern languages in London and the Southeast of England for 11 years and in Ireland worked as an Education Officer for Post-Primary Languages Ireland (Department of Education). His research interests currently include the decolonisation of approaches to the teaching and learning of language varieties, Content and Language Integrated Learning, plurilingualism, translanguaing and EAL in post-Primary settings.

Notes

1 A search on the Scopus database for the keywords ‘decolonization/decolonisation’ and ‘language education’ attests to a growing interest in this area of research, growing from 3 articles in 2010 to 32 in 2022. Leading countries/territories engaged in decolonisation research and languages education include South Africa (32), USA (27), Canada (21) Australia (11) and New Zealand (6) with the United Kingdom occupying fourth place (11). Interestingly, of the 132 articles cited in the database related to this area of research, 132 are written in English with the other 6 written in Spanish (3), French (2) and Portuguese (1) respectively. These finds perhaps indicate a need for greater decentring of research publication practices to support those who do not use English professional or as a lingua franca or, indeed, encourage others to learn new languages to access this research.

2 According to data compiled by the CSO in 2018, Polish was the highest non-Irish nationality (122,515) in the state, followed by Lithuanian (36,552), Romanian (29,186), Latvian (19,933) and Brazilian (13,640) (CSO Citation2018).

3 It is important to note that Irish, although not a ‘foreign’ language, was often separated from this group despite the obvious pedagogical synergies that exist between the teaching of Irish in English-medium educational institutions and other languages in the curriculum.

4 eTwinning is an approach originally developed by European Union under Erasmus+ to facilitate international collaboration between teachers and students using ICT and communication platforms as means to communicate across long distances (see European Commission Citation2022).

5 The Portuguese specification goes one stage further and explicitly recognises how the specification is designed ‘with all standard variations of the Portuguese language in mind […] including, but not limited to, those from Angolan, Brazilian, Mozambican, Portuguese and other Portuguese-speaking heritage backgrounds’ (9). Unfortunately, the rest of the specification only refers to the ‘target language’ rather than ‘languages’ or ‘linguistic varieties’.

References

- AHEAD. 2021. Universal Design for Learning” AHEAD, Accessed 3 November, 2021. https://www.ahead.ie/udl.

- Barkhuizen, G. 2017. Reflections on Language Teacher Identity Research. New York: Routledge.

- Bhabha, Homi. 1984. “Of Mimicry and man: The Ambivalence of Colonial Discourse.” In Part 8.6 in Deconstruction: A Reader, edited by Martin McQuillan, 414–424. New York: Routledge. doi:10.4324/9781315095066.

- Bhambra, Gurminder, K. Delia Gebrial, and Kerem Nisancioglu, eds. 2018. Decolonizing the University. London: Pluto Press.

- Buka, Andrea Mqondiso, Nomzi Florida Matiwane-Mcengwa, and Maisha Molepo. 2017. “Sustaining Good Management Practices in Public Schools: Decolonising Principals’ Minds for Effective Schools.” Perspectives in Education 35 (2): 99–111. doi:10.18820/2519593X/pie.v35i2.8.

- Carstens, Adelia. 2014. “Language and Decolonisation. The Language Question in Higher Education: Transformations in Our Doing, Talking and Thinking”. Paper Presented at CPUT Language Indaba, August 15, University of Pretoria.

- Central Statistics Office (CSO). 2018, Sept 18. “Census 2016 -Non-Irish Nationalities Living in Ireland [Infographic].” Accessed 16 December, 2022. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cpnin/cpnin/.

- Council of Europe 2001. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press

- Council of Europe 2017. Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching, Assessment. Strasbourg: Language Policy Division.

- Criser, Regine, and Suzuko Knott. 2019. “Decolonizing the Curriculum “.” Die Unterrichtspraxis 52 (2): 151–60. doi:10.1111/tger.12098.

- Emejulu, Akwugo. 2018. “Decolonising SOAS: Another University is Possible’. Chapter 17 in Rosanne Chantiluke.” In Rhodes Must Fall: The Struggle to Decolonise the Racist Heart of Empire, edited by Brian Kwoba, and Athinangamso Nkopo, 168–174. London: Zed Books Ltd.

- European Commission. 2022. “Overview”. European School Education Platform Beta. 2022, August. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://school-education.ec.europa.eu/en/etwinning.

- Facing History and Ourselves. 2022. “Identity Charts”. 23 August, 2022. https://www.facinghistory.org/resource-library/teaching-strategies/identity-charts.

- Ford, Jospeh, and Emanuelle Santos. 2022. “Decolonising Languages: Ways Forward for UK HE and Beyond”. Languages, Society and Policy. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.lspjournal.com/post/decolonising-languages.

- Foulis, Elena. 2022, October 10. “Culturally Responsive Pedagogy: A Path Towards Inclusive Excellence in Heritage Language Education [Paper Presentation].” George Mason University Spanish heritage Language Education. Online Lecture Series. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v = O6Hp7fK2tJM.

- Freire, Paulo. 2000. Pedagogy of the Oppressed, 30th Anniversary Edition. New York: Continuum Publishing.

- García, Ofelia. 2019. “Decolonizing Foreign, Second, Heritage, and First Languages. Implications for Education.” In Decolonizing Foreign Language Education. The Misteaching of English and Other Colonial Languages, edited by Donaldo Macedo, 152–68. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Gorter, D. 2006. “Introduction: The Study of the Linguistic Landscape as a New Approach to Multilingualism.” International Journal of Multilingualism 3 (1): 1–6. doi:10.21832/9781853599170-001.

- Grubb, Sophie. 2020. “Education Schools ‘Decolonising’ their Curriculum.” The Post, 10. Bristol (UK).

- Hannigan, Alannah, Daniel Faas, and Merike. Darmody. 2022. “Ethno-cultural Diversity in Initial Teacher Education Courses: The Case of Ireland.” Irish Educational Studies, 1–16. doi:10.1080/03323315.2022.2061559.

- Heinz, Manuela, Elaine Keane and Connor Foley. 2017. “Career Motivations of Student Teachers in the Republic of Ireland: Continuity and Change During Educational Reform and ‘Boom to Bust’ Economic Times.” In Helen M. G. Watt, Paul W. Richardson, Karl Smith (eds.). 2017. Global Perspectives of Teacher Motivation. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press: 1–21. doi:10.4324/9781315095066.

- Herold, Frank. 2019. “Shulman, or Shulman and Shulman? How Communities and Contexts Affect the Development of pre-Service Teachers’ Subject Knowledge.” Teacher Development 23 (4): 488–505. doi:10.1080/13664530.2019.1637773.

- Hornberger, Nancy H. 1989. “Continua of Biliteracy.” Review of Educational Research 59 (3): 271–96. doi:10.3102/00346543059003271.

- Ibrahim, Yousaf. 2010. “Between Revolution and Defeat: Student Protest Cycles and Networks.” Sociology Compass 4 (7): 495–504. doi:10.1111/j.1751-9020.2010.00289.x.

- Jemal, Alex, and Sarah Bussey. 2018. “Transformative Action: A Theoretical Framework for Breaking New Ground.” Ejournal of Public Affairs 7 (2): 37–65.

- Kramsch, C. 2019. “Between Globalization and Decolonization. Foreign Languages in the Cross-Fire.” In Decolonizing Foreign Language Education. The Misteaching of English and Other Colonial Languages, edited by D. Macedo, 50–72. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Little, David, and D. Kirwan. 2021. “Language and Languages in the Primary School. Some Guidelines for Teachers”, edited by Post-Primary Languages Ireland. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://ppli.ie/language-assistant-information/.

- Lushaba, Lwazi. 2018. “Decolonising Pedagogy: An Open Letter to the Coloniser. Chapter 28 in Rosanne Chantiluke.” In Rhodes Must Fall: The Struggle to Decolonise the Racist Heart of Empire, edited by Brian Kwoba, and Athinangamso Nkopo, 168–174. London: Zed Books Ltd.

- Mignolo, Walter D., and Catherine E. Walsh. 2018. On Decoloniality: Concepts, Analytics, Praxis. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. doi:10.2307/j.ctv11g9616.

- NCCA. 2017. “Junior Cycle: Modern Foreign Languages.” Accessed November 9, 2022. https://curriculumonline.ie/Junior-Cycle/Junior-Cycle-Subjects/Modern-Foreign-Languages/.

- NCCA. 2020. “Leaving Certificate. Portuguese Specification.” Accessed November 9, 2022. https://curriculumonline.ie/Senior-Cycle/Senior-Cycle-Subjects/Portuguese/.

- NCCA. 2022. “Senior Cycle Review". Advisory Report. Accessed November 9, 2022.

- Panagiotopoulou, Julie A., Lisa Rosen, and Jenna Strykala. 2020. “Inclusion, Education and Translanguaging.” In How to Promote Social Justice in (Teacher), 1–10. Education? Köln: Springer.

- Pearson. 2022. “Permission to Speak: Amplifying Marginalised Voices Through Languages.” 2022, September. https://www.pearson.com/uk/educators/schools/subject-area/modern-languages/why-languages-matter/diversity-and-inclusion.html.

- Peters, Michael A. 2014. “Why is My Curriculum White?.” Educational Philosophy and Theory 47 (7): 641–646. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00131857.2015.1037227.

- Peters, Michael A. 2015. Why is my Curriculum White?: Taylor & Francis.

- Quijano, Anibal, and Michael Ennis. 2020. “Coloniality of Power, Eurocentrism, and Latin America.” Nepantla: Views from South 1 (3): 533–580. https://muse.jhu.edu/article/23906.

- Schilling-Estes, Natalies. 2006. “Dialect Variation.” In An Introduction to Language and Linguistics, edited by Ralph Fasold, and Jeffery Connor-Linton, 311–341. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Shain, Farzana. 2021. “Educating.” In Chapter 14 in Being Sociological, edited by Steve Matthewman, Bruce Curtis, and David Mayeda, 219–236. London: Red Globe Press (Macmillian).

- Shain, Farzana, Ümit Kemal Yıldız, Veronica Poku, and Bulent Gokay. 2021. “From silence to ‘strategic advancement’: institutional responses to ‘decolonising’ in higher education in England.” Teaching in Higher Education 26 (7-8): 920–936. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2021.1976749.

- Sheoran Appleton, Nayantara. 2019, February 4. ‘Do Not ‘Decolonize' … If You Are Not Decolonizing: Progressive Language and Planning Beyond a Hollow Academic Rebranding’. Critical Ethnic Studies. Minnesota: University of Minnesota Press. . Accessed November, 9, 2022. http://www.criticalethnicstudiesjournal.org/blog/2019/1/21/do-not-decolonize-if-you-are-not-decolonizing-alternate-language-to-navigate-desires-for-progressive-academia-6y5sg.

- Shulman, Lee. 1987. “Knowledge and Teaching: Foundations of the New Reform.” Harvard Educational Review 57 (1): 1–22.

- Stein, Sharon, and Vanessa Andreotti. 2017. “Higher Education and the Modern/Colonial Global Imaginary.” Cultural Studies ↔ Critical Methodologies 17 (3): 173–181. doi:10.1177/1532708616672673.

- Stein, Sharon, and Vanessa Andreotti. 2018. “Decolonization in Higher Education.” In In Encyclopaedia of Educational Philosophy and Theory, edited by Michael Peters, 370–375. Singapore: Springer.

- TCI. 2016. Cosán: Framework for Teachers’ Learning.” Edited by Teaching Council of Ireland. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/website/en/teacher-education/teachers-learning-cpd-/cosan/.

- TCI. 2017. “Droichead: The Integrated Professional Induction Framework.” Edited by Teaching Council of Ireland. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/teacher-education/droichead/.

- TCI. 2020. “Céim: Standards for Initial Teacher Education.” Edited by Teaching Council of Ireland. Accessed November 9, 2022. https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/teacher-education/initial-teacher-education/ceim-standards-for-initial-teacher-education/.

- TCI. 2022. Teaching Council Registration. Curricular Subject Requirements (Post-Primary). Maynooth: The Teaching Council. https://www.teachingcouncil.ie/en/news-events/latest-news/curricular-subject-requirements.pdf.

- Tervalon, Melanie, and Jann Murray-García. 1998. “Cultural Humility Versus Cultural Competence: A Critical Distinction in Defining Physician Ichardson, Karl Smith Outcomes in Multicultural Education.” Journal of Health Care for the Poor and Underserved 9 (2): 117–125. doi:10.1353/hpu.2010.0233.

- Tiffin, Helen. 1987. “Post-colonial Literatures and Counter-Discourse.” Kunapipi 9 (3): 17–34. https://ro.uow.edu.au/kunapipi/vol9/iss3/4.

- Tuck, Eve, and K.Wayne Yang. 2012. “Decolonization is Not a Metaphor.” Decolonization: Indigeneity, Education & Society 1 (1): 1–40. https://jps.library.utoronto.ca/index.php/des/article/view/18630.

- van Deusen-Scholl, Nelleke. 2003. “Toward a Definition of Heritage Language: Sociopolitical and Pedagogical Considerations.” Journal of Language, Identity & Education 2 (3): 211–230. doi:10.1207/S15327701JLIE0203_4.

- Varghese, Manka, Suhanthie Motha, Gloria Park, Jenelle Reeves, and John Trent. 2016. “Language Teacher Identity in (Multi)Lingual Educational Contexts [Special Issue].” TESOL Quarterly 50 (3): 545–571. doi:10.1002/tesq.333.

- Williams, Lavie, Isabelle Clark, and Savannah Sevenzo. 2018. “Student Voices from Decolonise Suffolk’. Chapter 19 in Rosanne Chantiluke.” In Rhodes Must Fall: The Struggle to Decolonise the Racist Heart of Empire, edited by Brian Kwoba, and Athinangamso Nkopo, 179–185. London: Zed Books.

- Zeichner, Kenneth. 1983. “Alternative Paradigms of Teacher Education.” Journal of Teacher Education 34 (3): 3–9. doi:10.1177/002248718303400302.