ABSTRACT

This paper argues that the combination of (i) creative language pedagogy informed by sociocultural theory (SCT), and (ii) a participatory, democratic approach to language learning inclusive of learner voice, supports language (re-) engagement for Irish language learners and educators in English-medium education, and in society at large. Firstly, existing challenges for Irish language learning and teaching at the primary level in English-medium education (EME) are explored within the broader context of Irish language engagement. In response, a school-based participatory action research (PAR) study which piloted SCT-informed pedagogical approaches of peer-tutoring, student-parent tutoring, and technology-mediated language learning is then presented. Focusing on overarching outcomes, the findings of this small-scale study are outlined which indicate an increase in both Irish language use and self-assessed proficiency, and overall motivation level consolidation amongst learners. In addition, the potential of a PAR approach in supporting engagement and partnership in Irish language learning is considered. In conclusion, recommendations for policy, practice, and research are suggested to further Irish language engagement in EME.

1. Introduction

Ongoing concern in relation to Irish language attainment and engagement at the English-medium primary level poses questions for educators, learners, and policymakers alike. In recent decades, a notable decline in learners’ Irish language attainment in English-medium education (EME), coupled with limited opportunity for learners to experience Irish as a living language, arguably contributes to an apparent lack of engagement with the language.

This paper first outlines the Irish language context in Ireland, prior to the exploration of existing challenges for Irish language teaching and learning at the English-medium primary level. In response, the author proposes a sociocultural theory (SCT)-informed pedagogical approach with reference to the research context, design, and implementation, and a supporting participatory action research methodology as a response to the challenges and imperatives facing both learners and educators of Irish alike on the learning journey.

This school-based research informs both practitioners and policymakers of the potential impact of creative pedagogies and participatory approaches within an endangered language context with specific reference to the teaching and learning of the Irish language in English-medium education. This is achieved by outlining learner outcomes in relation to Irish language usage, self-assessed proficiency, and attitudes and motivation towards Irish language learning. This study also outlines the potential of participatory action research (PAR) as a key approach in actualising a democratic and empowering approach to learner engagement in an endangered language learning context. Finally, recommendations for practice and policy at the school and national level are suggested in order to actively support the teaching and learning of Irish as a living language at English-medium primary schools in Ireland.

1.1. Irish language context in Ireland

The native Irish language has been the official first language of the Republic of Ireland since the founding of the state in 1922. English is deemed the second official language while being the predominant spoken language of the country. Irish is also considered an endangered language (UNESCO Citation2019) which represents quite a unique dual status (Romaine Citation2008). Fishman (Citation1991) maintains that intergenerational transmission is the most salient yardstick by which to evaluate the vitality of a language. On that premise, the Irish language is designated as definitely endangered (UNESCO Citation2019). The weakening trends in relation to intergenerational transmission and trends in relation to peer and community usage of Irish means that the Irish language relies heavily on education as the principal mode of transmission, in addition to the connection between the home and other domains (Ó Murchadha and Migge Citation2017).

Speakers of Irish as a first language represent a dispersed minority in Ireland, and thus the majority of speakers and learners of Irish engage with the language as an additional language in the English-medium education sector. The language is negotiating a veritable flux whereby its status as the predominant language in native Irish-speaking parts of the country (known as the Gaeltacht) is under threat, representing a destabilising trend for Irish language vitality (MacGearailt, Mac Ruairc, and Murray Citation2023). Census figures indicate that 40% of the population (1.87 million people) attest to have the ability to speak Irish and approximately one-third of whom (623,961 people) speak Irish on a daily basis daily within and outside of the education system (Central Statistics Office [CSO] Citation2023). However, only 71,968 reported speaking Irish daily outside of the education system, and less than a third (20,261) of these speakers reside in the Gaeltacht (CSO Citation2023). Conversely, there is evidence of the growth of Irish-speaking networks outside of the Gaeltacht, in addition to documented growth and success in the Irish-medium education sector (McCárthaigh Citation2021; Ó Duibhir Citation2018). A further area of growth is reflected in the multinational and linguistically diverse makeup of Ireland's residents who account for 12% of the total population (631,785), and whereby a further 3% of the population are of dual Irish nationality. The increase in linguistic and cultural diversity presents both challenges and opportunities for the Irish language (Devitt et al. Citation2018); multilingualism as a default in Irish society recontextualises Irish for all speakers including the very youngest school-going learners and speakers (Cronin Citation2005).

Against the backdrop of native and daily speakers of Irish in a multicultural and multilingual Ireland, the progress of learners and speakers of Irish as an additional language both in English-medium education and in society at large presents as a separate, less defined, and less purposive language community. Notwithstanding the decline in intergenerational transmission of Irish, other indicators of Irish language vitality such as (i) Irish language engagement and attainment in the IME sector, (ii) growth of Irish-speaking networks around the country, (iii) developments in lexicography and (iv) advances in official and legislative status – notably at European level (Government of Ireland Citation2021; European Commission Citation2021; Ó Caollaí Citation2022) – all contribute to an overall rounded view that the Irish language is in a ‘relatively good place’ (Walsh Citation2022, 320). It is questionable whether the areas of progression for the Irish language somewhat mask the ongoing challenges in EME with a veritable band-aid, as opposed to bolster language revitalisation efforts in EME in any tangible way.

2. Existing challenges for the Irish language in EME

The challenges facing educators and learners of Irish as an additional language in Ireland presented in this section relate to Irish language learners’ language use and attitudes towards the language at a societal level, and more specifically at EME primary level. Other pertinent issues in relation to Irish language teaching and learning at EME such as (i) teachers’ Irish language proficiency (Department of Education & Science Citation2007; Dunne Citation2020; Harris et al. Citation2006; NCCA Citation2008) and (ii) teachers’ disposition and attitudes towards the Irish language and teaching the language (Dunne Citation2015, Citation2019; Harris and Murtagh Citation1999) are not explored in this paper given the focus on primary school students as learners of Irish.

2.1. Positive attitudes & cultural value vs. General passivity

It is long established that learners and speakers of Irish as an additional language in Ireland (the majority of whom are second-language learners) have a complicated relationship with the language. Broadly speaking, the population has a relatively positive attitude towards the language and places a relatively high cultural value on the Irish language (Darmody and Daly Citation2015; MacGréil and Rhatigan Citation2009; Ó Riagáin Citation1997, Citation2008) whereby 67% of Irish adults in the Republic of Ireland are positively disposed towards the Irish language (Darmody and Daly Citation2015). Largely positive attitudes are also discernible towards the future of the Irish (Darmody and Daly Citation2015; MacGréil and Rhatigan Citation2009; Ó Riagáin Citation1997, Citation2008) coupled with strong support for the provision of Irish as a school subject (Darmody and Daly Citation2015). While it is observed that there is a generally positive attitude towards the Irish language and the prospect of learning Irish, such positive indicators do not necessarily equate to Irish language use (Dolowy-Rybińska and Hornsby Citation2021). Therein lies the challenge for learners, educators, and school-goers involved in teaching and learning Irish in English medium education: How can learners and educators – school-based, new, and reconnecting – who may have positive yet passive disposition towards a language be encouraged to (re-)connect with the language?

2.2. A closer look at challenges in Irish teaching and learning in EME

The most recent InspectorateFootnote1 Report (Inspectorate Citation2022) provides a timely insight into the teaching and learning of Irish in English-medium schools today. While concerns had been raised with regard to the teaching and learning of Irish in EME setting in previous reports (Inspectorate Citation2013, Citation2018), the seriousness of the concern in the 2022 report is reflected in its inclusion as one of four key messages for the primary sector. It was identified that ‘pupils’ learning outcomes, motivation and engagement in Irish needs to be improved’ (Inspectorate Citation2022, 103). It was documented that there is scope to improve the quality of pupils’ learning in approximately one-third of lessons observed (2016–2020) (Inspectorate Citation2022). An overarching necessity to foster more engaging and enjoyable Irish language learning experiences for children and recommendations to avoid direct translation during teaching and learning were also key references (Inspectorate Citation2022). The findings mirrored outcomes from the previous two Inspectorate reports (Inspectorate Citation2018, Citation2013). The current prognosis for Irish language teaching and learning arguably aligns with previous studies (Harris Citation2008a, Citation2008b; Harris and Murtagh Citation1999; Harris et al. Citation2006) which indicated a downward spiral in terms of learner Irish language proficiency between the years of 1985 and 2002 (Harris et al. Citation2006), as well as negative reviews by students in relation to the nature of Irish lesson content and materials (Harris Citation2008b; Harris and Murtagh Citation1999). Teaching and learning Irish, an endangered language, thus presents as a challenging aspect of primary school teaching in terms of supporting both learners and teachers.

It is argued that over the years, continued dependence on Irish language textbooks has had an adverse effect on students’ learning experience (Department of Education & Science Citation2007; Harris et al. Citation2006; Hickey and Stenson Citation2016; Inspectorate Citation2013, Citation2022) both in terms of lesson enjoyment and the development of literacy skills. It is noted that the communicative approach of the Irish language curriculum introduced in 1999, notwithstanding its benefits, resulted in predominantly oral language focus, particularly in relation to junior primary (Devitt et al. Citation2018); carrying the caveat that an over-emphasis on oral skills may have the unintended consequence of diminishing Irish literacy (Hickey and Stenson Citation2016) and the integration of other core language skills such as writing and listening. While the new Primary Language Curriculum (2019) supports the integration of language skills across languages informed by principles of cross-linguistic transfer and common underlying language proficiency (Ó Duibhir and Cummins Citation2012), its impact on learning outcomes is yet to be substantially evaluated. Its implementation in senior primary coincided with the Covid-19 pandemic which was not ideal in terms of optimum conditions for teacher engagement. Thus moving from an overdependence of textbook use, and navigating curriculum change and implementation present as challenging opportunities for Irish language teaching and learning.

Similar to Irish language use amongst the general population, the relatively positive attitudes towards the Irish language amongst primary-going children do not automatically translate into Irish language use outside the classroom or school (Devitt et al. Citation2018; Ó Duibhir and Ní Thuairisg Citation2019). Currently, the establishment and maintenance of a functional context of use to speak Irish outside of school is not attainable for children attending English-medium primary schools (Fleming and Debski Citation2007; Harris and Murtagh Citation1999) and Irish-immersion primary schools (Ó Duibhir and Ní Thuairisg Citation2019) constitutes a further challenge for Irish language learners and teachers. Students attending English-medium schools may require ongoing guidance, modelling, and encouragement which demonstrates that Irish can be spoken as a modern language of communication, and should be encouraged to progress from tokenistic to frequent and meaningful use of Irish (Fleming and Debski Citation2007). The absence of a functional context for most learners of Irish, not only limits their opportunities for contact with the naturalistic use of the language but also could impact adversely on integrative and instrumental motivation (Murtagh Citation2007).

Finally, negotiating the place and space of the Irish language at English-medium primary level in terms of its curricular status and real-life actualisation as a language presents an ongoing challenge. Falling standards in Irish attainment in EME primary has been partly attributed to the reduction of assigned curricular time to Irish (Harris Citation2008a). The recently launched Primary Curriculum Framework (NCCA Citation2023) proposes a further reduction of ascribed Irish lesson time (NCCA Citation2023) which has prompted concern (Ó Duibhir Citation2023). Time allocations aside, the proposed introduction of Modern Foreign Languages to senior primary classes may present an opportunity for the Irish language to be taught and learned within a more plurilingual approach which can further enable the transfer of skills across languages.

3. Presenting a creative and participatory approach

Having identified a number of the existing challenges for Irish language teaching and learning at English-medium primary level both in terms of sociolinguistic and curricular developments, this section will concentrate on providing further insight into how a creative and participatory approach to Irish language learning can be realised in partnership with English-medium primary school goers and their families. Firstly, the research context of the research study is outlined. Secondly, the study's methodology of participatory action research is introduced. The overarching conceptual framework of sociocultural theory which informed the pedagogical approach is subsequently examined. This leads to a brief overview of the design and implementation of the specific sociocultural theory (SCT)-informed approaches of tutoring (peer tutoring and student-parent tutoring) and technology-mediated language learning. Finally, the data collection relevant to this paper is presented.

3.1. Research context

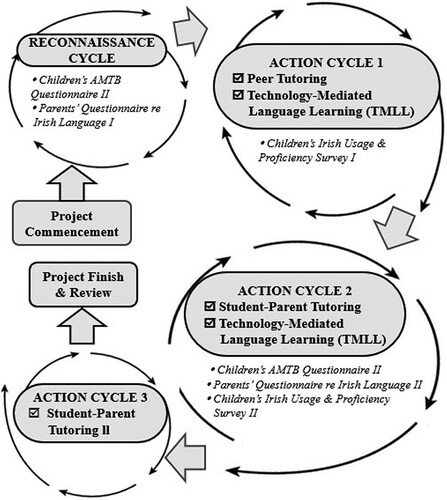

The school-based study was carried out with a class (n = 20) of fourth-class pupils (aged 10 or 11) and their parents (n = 20) in English-medium primary school in Dublin. The teacher-researcher assumed the dual role of being a class teacher of one of the fourth classes, and lead researcher in the school-based study, which consisted of a reconnaissance cycle, and three action cycles over the course of an academic school year. Ethics approval was received from the Trinity College School of Education Ethics Committee prior to the commencement of the study, and on two further junctures as the study progressed and developed. Informed participant consent was invited and established in writing at the outset of the study, and participants were free to withdraw from the study at any stage The class comprised ten boys and ten girls. Eight of the children in the class spoke English as their second language. The other twelve spoke English as their first language, four of which had one parent who spoke English as a second language. Over half of the parents involved in the project were learning the Irish language for the first time. Two other fourth-level classes also engaged with the evaluation of attitude and motivation towards the Irish language at the beginning of Action Cycle 1, and again at the end of Action Cycle 2 as reference classes (n = 40) in the study. The parents of the other two fourth classes (n = 40) also completed an initial parents’ questionnaire in relation to the Irish language and their child. The comparatively reduced level of involvement with the two neighbouring classes was indicative of the teaching context.

3.2. Methodology

A participatory action research (PAR) methodology was chosen for this study on the basis that the study was centred on addressing a concern in relation to learner engagement with the Irish in the context of Irish language teaching and learning in EME primary school context, and how to approach this concern in an optimum way in terms of pedagogical interventions. Thus, there are two elements at play – addressing a concern and doing something about it. Action research can be defined as ‘the study of a social situation with a view to improving the quality of action within it’ (Elliot Citation1991, 69). Participatory action research (PAR) is built on democratic processes between participants (Elliot Citation1991). This is echoed by Coghlan and Brannick who identify ‘egalitarian participation’ as a key component of PAR (Citation2014, 15). These values of PAR were central to facilitating student and parent engagement in the project, design, language learning, and evaluation. A participatory and consultative approach to involving learners is recommended in endangered language contexts (Bodó et al. Citation2022; Flores Farfán and Olko Citation2021) and language learning contexts generally (Ahmadian and Tavaskoli Citation2011; Banegas Citation2019). In the Irish language context, a participatory and advisory approach was utilised with adult learners of Irish in the workplace which prioritised the identified needs and input of learners in relation to their Irish language learning journey (Ní Loingsigh and Mozzon-McPherson Citation2020).

3.3. Conceptual framework (sociocultural theory)

This study was underpinned by a sociocultural theory-informed conceptual framework which informs the piloted Irish language pedagogies at the class and school community level. The central tenet of sociocultural theory, as developed by Vygotsky, rests on the premise that the human mind is mediated (Lantolf Citation2000a, Citation2000b). Sociocultural theory (SCT) recognises the interdependence of social and individual processes (John-Steiner and Mahn Citation1996) in the co-construction of knowledge. More specifically in the context of linguistics, SCT-informed (second) language theory contends that language development and language learning are mediated, relational, and social processes (Lantolf Citation2002) given that ‘the human mind is always and everywhere mediated primarily by linguistically based communication’ (Lantolf Citation2002, 104). SCT contends that language acquisition is situated in people engaged in the activity, as opposed to concentrating primarily on processes representative of certain interactionist approaches to SLA for example. An SCT approach to language learning foregrounds the learners in the study – in real-world settings, while also recognising the importance of and synergistic relationship between both the cognitive and social aspects of learning a language.

The framing of second (or additional) language acquisition as a mediated process encompasses specific while interrelated SCT concepts which include mediation between expert and novice, the more knowledgeable other (MKO), peer tutoring (PT), and the zone of proximal development (ZPD), and more broadly technology-mediated language learning (TMLL). Language learning mediation between an expert and novice is a well-established language learning concept which inherently explores mediated language in the zone of proximal development (ZPD) whereby the more knowledgeable other (MKO) stretches the learning capacity of the novice in order to facilitate new learning. The exercise of contingent support on the part of the MKO whereby explicit mediation is gradually replaced by a more implicit or modified form of assistance or scaffolding (Hughes Citation2015; Lantolf Citation2000b; Mermelshtine Citation2017). Conversations among language learners can be as effective as instructional dialogue between teachers and learners (Lantolf Citation2000a, Citation2002, Citation2012; Swain Citation1995). The conception that knowledge is constructed through dialogue is central to peers learning from, and with, each other.

3.4. Piloted SCT-informed pedagogical approaches & action cycles

The SCT-informed pedagogical approaches piloted in this study Peer Tutoring, Student-Parent Tutoring and Technology-Mediated Language Learning. As illustrates, Peer Tutoring during Irish class was the first piloted Irish language learning activity. Peer Tutoring lessons took place twice every week over the course of 12 weeks during Action Cycle 1. A three-phase communicative approach was realised for each lesson which supported the reciprocal peer-mediated activities during the communicative phase whereby pairs of children rotated the role of tutor and tutee in each lesson. Children engaged in a written evaluation of each lesson which detailed their learning as well as how they believed their partner assisted them. As well as activity-specific language input, the teacher studied video footage of the peer-mediated phase of the lesson periodically to inform teaching input with regard to the pupils’ required Irish language input and learning to talk around as Gaeilge [in Irish] the specific tasks in which they engaged. Student-Parent Tutoring was piloted in Action Cycle 2 and 3. During a seven-week term, children brought home one Irish lesson per week to share with a parent. The lessons were co-designed by the teacher-research and children and trialled in class. At home, the children assumed the role of tutor or More Knowledgeable Other. Both parent and child completed a short evaluation of the lesson reflecting on learning, and the role of the tutor/tutee respectively. Technology-Mediated Language Learning (TMLL) consisted of two blended learning initiatives: engagement with a teacher-facilitated Irish language Class Online Learning Zone and a Class Twitter Account of Irish language use curated by the teacher-research on behalf of the class. Both TMLL activities were launched halfway through Action Cycle 1 once Peer Tutoring was established and were secondary to the tutoring activities.

3.5. Data collection

Given the focus of this paper to explore creative and participatory approaches to Irish language teaching and learning in order to encourage potential learners (re-)

engagement with the Irish language, the summary findings presented relate directly to outcomes for the student and parent participants in the study in relation to (i) Irish language use and self-assessed proficiency and (ii) motivation towards the Irish language. While the study also explored learner experience and specific dynamics tutoring in relation to mediation and the role of the more knowledgeable other, specific dynamics of tutor and tutee in both it is envisaged to detail these findings in future research. The overarching impact of learners’ engagement with SCT-informed pedagogies with reference to pre- and post-intervention analysis is presented. details the specific PRE and POST data sources examined in this paper: (i) Children's AMTB Questionnaires, (ii) Children's Irish Language Usage & Self-Assessed Ability Survey and (ii) Parents’ Irish Language Questionnaire.

The Children's Attitude and Motivational Test Battery (AMTB) Questionnaire for Irish (Harris and Murtagh Citation1999) consisted of 77 statements addressed by five-point Likert response option, comprising 11 specific motivational scales therein. The AMTB was slightly adapted and updated in terms of cultural references. Adapted and shortened from that of Murtagh (Citation2007) the Children's Irish Language Usage & Self-Assessed Ability Survey consisted of 6 questions in comparison. Finally, the Parents’ Irish Language Questionnaire, similar to the children's AMTB, was also drawn from Harris and Murtagh's Twenty Classes Study (Citation1999) and underwent minor changes and reordering to the 32 questions to ensure suitability for the parent cohort.

4. Results

4.1. Irish language engagement

Following participation in two action cycles of the study, results indicate a higher level of engagement with the Irish language on the part of children in particular, and to a lesser extent on the part of parents. Firstly in the case of the student cohort, children (n = 20) reported a clear increase in the use of Irish in their homes compared to the outset of the study. Over one-third of students (7/20) progressed to one of the top three categories of frequency of Irish language use (Occasionally, Often & Very Often) and conversely the numbers of homes where Irish had never been spoken decreased by over a third (7/20 children).

In addition, children reflected on the level of opportunity they had experienced to speak Irish outside of school both prior to and after two action cycles. A similar trajectory of increased opportunity was reported whereby a sizeable decrease in the None at all and Not very much categories (−10 children collectively) of use engenders an upward trajectory in the categories of more frequent use (+9 children collectively)

Interrogating more specifically the domains of use in which children engaged with the Irish language, children identified strongly with At home with parents and siblings (+12 children) and Using a computer or tablet (+10 children), and Use of a computer or tablet and Use of a mobile phone or smart phone combined (+14 children), reflecting the domains directly associated with two pedagogical approaches of the project. Furthermore, the increased opportunity to use Irish was reflected in a number of additional domains, such as Occasional words with friends (+6), So people don't understand what I’m saying (+5). Interestingly there was a decrease in children reporting watching Irish language TV (−5). Children were also invited to elaborate upon other domains of use where children had experienced the opportunity to speak Irish outside the school in addition to those presented to the children. References to the tutoring at the home programme (with their parents or a sibling), speaking Irish with a parent or sibling at home, and engaging with the Class Online Learning Zone were prominent.

Examination of the Use of Irish at Home scale of the children's attitude and motivation questionnaire also corroborates an upward trajectory of Irish language engagement in children's homes. Results indicated a small but measurable increase in Irish language usage while the reference classes reported a decrease of twice the same proportion for the same period. Looking more closely at Use of Irish at Home scale items, interestingly an increase of fathers’ engagement with Irish at home progressing from an absence of fatherly engagement with Irish at the outset to the involvement of five fathers in speaking Irish at home at the end of Action Cycle 2.

Parents’ responses also illustrated an increase of Irish in the home whereby the absence of Irish use in the home reported by eight parents decreased to five parents, which in turn had a positive effect on other categories of more frequent use. Parents’ increased engagement with the language was visible not only through direct participation in student-parent tutoring but also in increased awareness and knowledge of their child's learning of Irish at school, how Irish is taught and learned, as well as increased support of the teaching of another subject through Irish.

4.2. Self-assessed Irish language ability

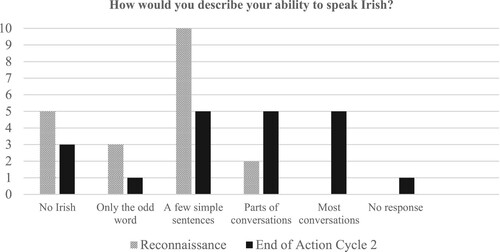

Children reported an increase in self-assessed Irish language ability over the course of the two Action Cycles. As detailed in there was a decrease in the more modest categories of Irish ability including no Irish, culminating in an increase in self-assessed ability to participate in parts of conversations and most conversations (+ 8 children collectively).

Relatedly, the children's attitude and motivation questionnaire Irish Ability Self-Concept scale indicated a negligible decrease in the mean scale item score, which on comparison with a small decrease on the part of the reference fourth classes reflected overall relative consolidation. Closer examination of the six scale items for the participating students reflected overall slight decreases (4/6 scale items) compared to slight increases (2/6 scale items) for students. Interestingly, the two-scale items (Item 66: I am better than most pupils in my class at speaking Irish; Item 77: I am better at speaking Irish than I am at doing Maths) which presented with an increased POST scale item mean score specifically referenced Irish speaking which suggests the interactive nature of tutoring may have positively influenced children's self-concept in relation to speaking Irish.

The majority of parents attested to self-assessed ability of having either only the odd word or a few simple sentences. While levels of parental engagement with tutoring at home were encouraging, most parents remained of the opinion that they were not in a position to give the school any practical support as far as the teaching of Irish is concerned. The majority of parents reaffirmed that the reason they did not help their child with Irish homework was not being very good at Irish themselves. Nevertheless, there was evidence of an increase in parents’ support of Irish homework, with an increase from 4 to 10 parents assisting with Irish spelling.

4.3. Attitudes and motivation towards the Irish language

The children's PRE and POST attitude and motivation questionnaire analysis demonstrated an overall consolidation of attitude and motivation levels compared with a decrease in the corresponding score of the reference classes. However, at the outset, PRE score disparities between the participating classes (n = 20) and reference classes (n = 40) in terms of differing linguistic experiences growing up and in current home life questioned the applicability of direct comparisons between the two groups. Rather than attributing undue prominence to the overarching Index scores, examination of the individual 11 attitude and motivation questionnaire scales afforded insight to specific areas of attitude and motivation-related language learning concepts. For example, decreases in both the Instrumental Orientation to Irish and Irish Lesson Anxiety mean scale scores illumination subtle developments in relation to specific motivational orientations not discernible at the overarching Index level.

Parents' general attitude towards the Irish language remained stable whereby any positive change was closely correlated to their child's engagement with the language and the teaching of Irish to their child. The Parents' Irish Language Questionnaire findings were supported by parents’ perspectives shared at PRAG meetings which further indicated their awareness of their child's engagement and motivation towards the language project.

5. Discussion

5.1. Irish language use and self-assessed ability

While overall levels of Irish language use and self-assessed ability of the participant class at the outset of the study broadly align with other school-based studies (Fleming and Debski Citation2007; Harris and Murtagh Citation1999; Murtagh Citation2007), children's levels of use of Irish outside of the classroom were nonetheless relatively low compared with national norms (Darmody and Daly Citation2015). This is arguably indicative of the ‘perennial challenge’ (Ó Duibhir and Ní Thuairisg Citation2019, 127) of actualising the transfer of in-school Irish language engagement to the home – a challenge which is arguably pronounced in English-medium (Fleming and Debski Citation2007; Harris Citation2008a).

The findings of increased language engagement and use of the Irish language across domains in this study suggest that specifically planned language interventions demonstrated encouraging results in relation to Irish language use (Merrins-Gallagher, Kazmierczak-Murray, and Perkins Citation2019; Moriarty Citation2015, Citation2017; Ní Chróinín, Ní Mhurchú, and Ó Ceallaigh Citation2016). The defining feature of this study's SCT-informed pedagogy lies in the incremental development of the child as learner or tutee and as the more knowledgeable other (MKO) or tutor, over the course of peer tutoring engagement in the classroom, which empowered the students to develop their teaching and learning skills prior to leading Irish lessons in the home with parents. Children were instrumental in igniting interest and engagement with each other during peer tutoring and subsequently evolved as a veritable catalyst for Irish (re-)engagement in the home. The language lessons for parents were relevant to both child and parent learning and parental feedback indicates that parents engaged primarily to support and observe their child's own learning.

From a curriculum perspective, an outcome of increased use of the language responds to the Primary Languages Curriculum (PLC) which references the importance of opportunities for L2 learners of Irish to engage with the Irish language outside of the Irish lesson and encourages the provision of a ‘wide range of meaningful a wide range of relevant and meaningful linguistic and communicative experiences with peers and adults’ (NCCA Citation2019, 26). Given the aforementioned proposed reduction in discrete Irish language teaching time as part of a revised curriculum framework (NCCA Citation2023; Ó Duibhir Citation2023), the provision of such opportunities will be increasingly vital in order to support progress in children's engagement with the Irish language into the future.

An increase in children's self-assessed ability may suggest that increased opportunities to engage with the Irish language contributed to a growing confidence in their use of the language. A language conundrum exists for children who are positively disposed towards the language but who have little or no opportunity to speak the language at home (Dunne Citation2020; Fleming and Debski Citation2007; Harris and Murtagh Citation1999). While it is argued that positive attitudes towards the Irish language have not historically resulted in increasing the vitality of the language (Dolowy-Rybińska and Hornsby Citation2021; Ó Duibhir and Ní Thuairisg Citation2019), it would be useful to explore if increasing opportunities to use the language, coupled with growing self-assessed ability and confidence in the language, might produce a different dynamic. While the increase in Irish ability is self-reported and could potentially overstate (or understate) a given level, it is nonetheless an encouraging outcome in light of the many hours of Irish lessons experienced by schoolgoers in EME which, generally speaking, have not yielded the proficiency levels nor engagement that one might expect (Barry Citation2021; Batardière et al. Citation2023; Ó Laoire Citation2007).

5.2. Attitudes and motivation

The maintenance of a positive attitude towards the Irish language as children in English-medium primary schools progress through senior primary classes is not a new challenge by any means (Owens Citation1992). The participating children's engagement with the study may have influenced the retention of consistent motivation levels of an otherwise potential downward trajectory reported in the reference classes. Given that Irish can tend to not be particularly favoured amongst the choice of primary school subjects (Devine et al. Citation2020) and that primary school-going children tend to have a higher level of disengagement with Irish in comparison with English and literacy (Devitt et al. Citation2018) the fact that the motivation scores held steady is encouraging.

A decrease in Instrumental Orientation to Irish on the part of the class may indicate that children's engagement in peer tutoring in class and tutoring in the home, coupled with active and purposeful involvement in the design and review of the study, may have engendered a shift in children's perception of Irish as a school subject, or utilitarian task, to a language that has relevance in other domains, and relevance within the project realisation itself. The ‘sealed-off nature’ (Harris Citation2008a, 63) of the Irish language in primary schools can inhibit learners’ perception and/or experience of Irish as a living language. The decrease in instrumental motivation may also suggest the emergence of more intrinsic and integrative motivation on the part of the children to engage with the language, having been supported by the SCT-informed learning approach and participatory and democratic methodology during the study.

The Irish Lesson Anxiety scale indicated a notable decrease in nervousness to speak Irish amongst children and an increase in relation to inhibition to speak Irish in class. This trajectory is encouraging, given that Harris and Murtagh identified Irish Lesson Anxiety rates in their 1999 study as being at a high level, which was reflective of the Irish Lesson Anxiety levels of the participating class at the outset of the current study. The Irish Ability Self-Concept scale scores also support this finding, indicating an increase in the self-perception of Irish speaking ability. This suggests that children's decrease in Irish lesson anxiety levels and growth in confidence to speak Irish was potentially due to an increase in (in-class and out-of-class) Irish language engagement opportunities (Murtagh Citation2007; Murtagh and Van der Silk Citation2004).

5.3. Power of partnership and voice

The realisation of participatory practices also merits reflection. The invitational nature of the Reconnaissance Cycle not only serves to inform the manner in which language learning pedagogy can be devised and piloted; it also represents a commitment to address specific concerns communicated through the voice of participants. Such a PAR approach actively seeks genuine engagement from the outset, conceives schools as potential focal point for community-wide projects, and drives a ‘broader mandate for collaborative social change by involving those with a stake in the changes’ (Brydon-Miller and Maguire Citation2009, 88). A partnership approach which focusses on assets of learning communities rather than a deficit perspective may support the improvement of learning and experience for pupils and empower parents to become involved in Irish language learning across school contexts. For example, the overuse of textbooks in Irish language was readily identified by students themselves during the reconnaissance cycle reflective of practice at large (Department of Education & Science Citation2007; Harris et al. Citation2006; Hickey and Stenson Citation2016; Inspectorate Citation2018; Moriarty Citation2017). The interactive and agentic nature of peer tutoring and student-parent tutoring offered students an alternative to a textbook-led programme, and in addition, involved students in the co-creation and co-design of both lesson and learning resources The study reinforced the importance of student voice and consultation in the creation of Irish language approaches and programmes (Dalton and Devitt Citation2016; Harris Citation2008a; Moriarty Citation2017) in order to ensure students come on board and become included and invested in the Irish language learning process.

6. Conclusion

This small-scale study suggests that increasing children’s engagement with the Irish language in the EME setting is possible whereby innovative pedagogy is informed by sociocultural theory, and also supported by a participatory approach of ongoing dialogue and collaboration between participants and facilitators throughout the process. This dual approach places value on the language learning experiences of all learners (new and re-engaging), and repositions Irish as a tangible living language as opposed to a mere school subject. This study responds directly to the challenges of teaching and learning of Irish in English-medium primary schools in Ireland, and to the broader challenges of the language teaching and learning in an endangered language context.

Dependence on the education system to support the transmission of the Irish language is well documented (Batardière et al. Citation2023; Edwards Citation2017; Harris Citation2008a; Ó Murchadha and Migge Citation2017). To what extent can such a participatory Irish language study (whether involving tutoring, a guided reading programme, precision teaching, phonological awareness, and/or technology-mediated language learning), both extend its duration in addition to develop to a scaled-up initiative with community partnership? Progression from a stand-alone teacher-led project, to potentially a language initiative at a specific year level in a given school, or across a cluster of schools with dedicated support from designated Irish language bodies with community outreach may provide a trajectory for the small-scale positive impact on language engagement in this instance to evolve and endure. By encouraging parental involvement whereby the child is a catalyst for home learning, and encouraged in the role of More Knowledgeable Other (MKO). and developing community and school programmes which are interlinked, valued, and implemented sustainably, children can be empowered as learners of Irish to share their language proficiency in the home as well as in the community. The current study, while small-scale, could be piloted in other English-medium schools in order to investigate further its potential to engage learners who wish to progress to using and speaking Irish both inside and outside of the school context. Such projects, if piloted properly and sustainably, could contribute at the local level to the national objective of increasing the number of speakers who speak Irish on a daily basis outside the education system (Government of Ireland Citation2010).

In closing, the findings of the study serve to inform practice and policy in relation to the teaching and learning of Irish in English-medium primary schools. To ensure school-based studies do not play out to be isolated one-off projects, but rather a building block towards what can be achieved on a larger scale and over a more sustained period, and on a larger scale, the following recommendations are suggested:

Create mechanisms whereby the state can channel and support the potential of micro-agents or ‘bottom-up’ approaches led by educators and/or language activists in Irish language learning communities around the country.

Enact and support national initiatives visibly and meaningfully as set out in the policy (Government of Ireland Citation2010) to increase the number of active Irish speakers by funding and connecting Irish language-focused family learning initiatives in partnership with schools and the broader community to realise Irish language learning objectives in an authentic domain of use.

Ensure the provision of funding, dedicated learner-centred Irish language learning and pedagogy courses and opportunities for teachers of Irish as an Additional Language (IAL) which could compliment the current continuing professional development (CPD) models. Funded or subsided language programmes for teachers are essential (as evidenced in Wales and the Basque Country [Van Dongera, Van der Meer, and Sterk Citation2017]), especially at the primary level where teachers in the English-medium sector are not necessarily Irish language subject specialists.

A consultative and purposeful Irish language education policy which actively supports both educators and learners of Irish (wherein the majority of both cohorts are learners of Irish) is essential in order to stimulate Irish language engagement in EME. Irish language policy formation and real-life actualisation which actively supports grassroots school and community language learning projects and values participatory and democratic outreach – while continuously cognisant of evidence-based practice from other endangered language jurisdictions – may stimulate engagement and foster creativity amongst partners involved in learning and teaching the Irish language in the EME sector.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author.

Correction Statement

This article has been corrected with minor changes. These changes do not impact the academic content of the article.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Jane O’Toole

Jane O’Toole holds a PhD in Language Education (2023) from Trinity College Dublin. A primary school teacher, part-time researcher and third-level tutor, Jane is also a Coordinating Group Member of the Collaborative Action Research Network (CARN). Her research interests include language education and policy, school leadership and action research.

Notes

1 The Inspectorate is a division of the Department of Education which oversees the evaluation of primary and secondary schools and education centres.

References

- Ahmadian, M. J., and M. Tavaskoli. 2011. “Exploring the Utility of Action Research to Investigate Second-Language Classrooms as Complex Systems.” Educational Action Research 19 (2): 121–136. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650792.2011.569160.

- Banegas, D. L. 2019. “Language Curriculum Transformation and Motivation through Action Research.” The Curriculum Journal 30 (4): 422–440. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585176.2019.1646145.

- Barry, S. 2021. “Irish Language Self-Efficacy Beliefs: Mediators of Performance and Resources.” Australian Journal of Applied Linguistics 4 (3): 103–118. https://doi.org/10.29140/ajal.v4n3.526.

- Batardière, M. T., S. Berthaud, B. Ćatibušić, and C. J. Flynn. 2023. “Language Teaching and Learning in Ireland: 2012–2021.” Language Teaching 56 (1): 41–72. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444822000374.

- Bodó, C., B. Barabás, N. Fazakas, J. Gáspár, B. Jani-Demetriou, P. Laihonen, V. Lajos, and G. Szabó. 2022. “Participation in Sociolinguistic Research.” Language and Linguistics Compass 16 (4) e12451. https://doi.org/10.1111/lnc3.12451.

- Brydon-Miller, M., and P. Maguire. 2009. “Participatory Action Research: Contributions to the Development of Practitioner Inquiry in Education.” Educational Action Research 17 (1): 79–93. https://doi.org/10.1080/09650790802667469.

- Coghlan, D., and T. Brannick. 2014. Doing Action Research in Your Own Organization. London: Sage Publications.

- Cronin, M. 2005. Irish in the New Century/ An Ghaeilge San Aois Nua. Dublin: Cois Life Teoranta.

- CSO (Central Statistics Office). 2023. Census of Population 2022: Summary Results. https://www.cso.ie/en/releasesandpublications/ep/p-cpsr/censusofpopulation2022-summaryresults/educationandirishlanguage/.

- Dalton, G., and A. Devitt. 2016. “Irish in a 3D World: Engaging Primary School Children.” Language Learning & Technology 20 (1): 21–33. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/44440.

- Darmody, M., and T. Daly. 2015. Attitudes towards the Irish Language on the Island of Ireland. Dublin: ESRI & Foras na Gaeilge. https://www.esri.ie/publications/attitudes-towards-the-irish-language-on-the-island-of-ireland.

- DES (Department of Education & Science). 2007. Irish in the Primary School: Promoting the Quality of Learning. Dublin: DES Inspectorate Evaluation Studies.

- Devine, D., J. Symonds, S. Sloan, A. Cahoon, M. Crean, E. Farrell, A. Davies, T. Blue, and J. Hogan. 2020. Children’s School Lives: An Introduction. Report No.1 ed. Dublin: University College Dublin.

- Devitt, A., J. Condon, G. Dalton, J. O’Connell, and M. Ní Dhuinn. 2018. “An Maith Leat an Ghaeilge? An Analysis of Variation in Primary Pupil Attitudes to Irish in the Growing Up in Ireland Study.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 21 (1): 105–117. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2016.1142498.

- Dolowy-Rybińska, N., and M. Hornsby. 2021. “Why Revitalise?” In Revitalising Endangered Languages: A Practical Guide, edited by J. Olko and J. Sallabank, 104–116. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Dunne, C. 2015. “Becoming a Teacher of Irish: The Evolution of Beliefs, Attitudes and Role Perceptions.” Unpublished doctoral diss., Trinity College Dublin, Dublin, Ireland.

- Dunne, C. 2019. “Primary Teachers’ Experiences in Preparing to Teach Irish: Views on Language Proficiency and Promoting the Language.” Studies in Self-Access Learning Journal 10 (1): 21–43. https://doi.org/10.37237/100103

- Dunne, C. 2020. Learning and Teaching Irish in English-Medium Schools Part 2: 1971–Present. Dublin: Marino Institute of Education. https://ncca.ie/media/4797/learning-and-teaching-irish-in-english-medium-schools-1971-present-part-2.pdf.

- Edwards, J. 2017. “Celtic Languages and Sociolinguistics: A Very Brief Overview of Pertinent Issues.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 30 (1): 13–31. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2016.1230618.

- Elliot, J. 1991. Action Research for Educational Change. Milton Keynes and Philadelphia: Open University Press.

- European Commission. 2021. Report from the Commission to the Council on Whether the Union Institutions Have Sufficient Available Capacity for the Irish Language, Relative to the Other official EU Languages, to Apply Regulation No 1 without a Derogation as of 1 January 2022 COM/2021/315. https://ec.europa.eu/info/news/irish-now-same-level-other-official-eu-languages-2022-jan-03_de.

- Fishman, J. A. 1991. Reversing Language Shift: Theoretical and Empirical Foundations of Assistance to Threatened Languages. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Fleming, A., and R. Debski. 2007. “The Use of Irish in Networked Communications: A Study of Schoolchildren in Different Language Settings.” Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development 28 (2): 85–101. https://doi.org/10.2167/jmmd455.1.

- Flores Farfán, J. A., and J. Olko. 2021. “Types of Communities and Speakers in Language Revitalisation.” In Revitalising Endangered Languages: A Practical Guide, edited by J. Olko and J. Sallabank, 85–103. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Government of Ireland. 2010. 20 Year Strategy for Irish 2010-2030. Dublin: Government of Ireland. Accessed September 20, 2016. http://www.ahg.gov.ie.elib.tcd.ie/ie/Straiteis20BliaindonGhaeilge2010-2030/Foilseachain/Strait%C3%A9is%2020%20Bliain%20-%20Leagan%20Gaeilge.pdf.

- Government of Ireland. 2021. The Irish Language Gains Full Official and Working Status in the European Union [Press release]. Accessed December 2, 2022. https://www.gov.ie/en/press-release/e3150-the-irish-language-gains-full-official-and-working-status-in-the-european-union/.

- Harris, J. 2008a. “The Declining Role of Primary Schools in the Revitalisation of Irish.” AILA Review 21 (1): 49–68. https://doi.org/10.1075/aila.21.05har.

- Harris, J. 2008b. “Irish in the Education System.” In A New View of the Irish Language, edited by C. Nic Pháidín and S. Ó Cearnaigh, 178–190. Dublin: Cois Life Teoranta.

- Harris, J., P. Forde, P. Archer, S. Nic Fhearaile, and M. O’Gorman. 2006. Irish in Primary Schools: Long-Term National Trends in Achievement. Dublin: Stationery Office.

- Harris, J., and L. Murtagh. 1999. Teaching and Learning Irish in Primary School: A Review of Research and Development. Dublin: Institiúd Teangeolaíochta Éireann.

- Hickey, T. M., and N. Stenson. 2016. “One Step Forward and Two Steps Back in Teaching an Endangered Language? Revisiting L2 Reading in Irish.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 29 (3): 302–318. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2016.1231200.

- Hughes, C. 2015. “The Transition to School.” Psychologist 28 (9): 714–717.

- Inspectorate. 2013. Chief Inspector’s Report [2010-12]. Dublin, Ireland: The Stationery Office. http://www.education.ie/en/Publications/Inspection-Reports-Publications/Evaluation-Reports-Guidelines/Chief-Inspector%E2%80%99s-Report-2010-2012-Main-Report.pdf.

- Inspectorate. 2018. Chief Inspector’s Report [Evaluatory Report]. Dublin, Ireland: The Stationery Office. https://assets.gov.ie/25245/9c5fb2e84a714d1fb6d7ec7ed0a099f1.pdf.

- Inspectorate. 2022. Chief Inspector’s Report [2016-20]. Dublin, Ireland: The Stationery Office. https://www.gov.ie/en/publication/611873-chief-inspector-reports/.

- John-Steiner, V., and H. Mahn. 1996. “Sociocultural Approaches to Learning and Development: A Vygotskian Framework.” Educational Psychologist 31 (3-4): 191–206. https://doi.org/10.1080/00461520.1996.9653266.

- Lantolf, J. P. 2000a. “Introducing Sociocultural Theory.” In Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Learning, edited by J. P. Lantolf, 1–26. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Lantolf, J. P. 2000b. “Second Language Learning as a Mediated Process.” Language Teaching 33 (2): 79–96. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444800015329.

- Lantolf, J. P. 2002. “Sociocultural Theory and Second Language Acquisition.” In The Oxford Handbook of Applied Linguistics, edited by R. B. Kaplan, 104–114. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Lantolf, J. P. 2012. “Sociocultural Theory: A Dialectical Approach to L2 Research.” In The Routledge Handbook of Second Language Acquisition, edited by M. Gass and A. Mackey, 57–72. London, UK: Routledge.

- MacGearailt, B., G. Mac Ruairc, and C. Murray. 2023. “Actualising Content and Language Integrated Learning (CLIL) in Irish-Medium Education; why, How and Why Now?” Irish Educational Studies 42 (1): 39–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/03323315.2021.1910971.

- MacGréil, M., and F. Rhatigan. 2009. The Irish Language and the Irish People: Report on the Attitudes towards Competence in and Use of the Irish Language in the Republic of Ireland in 2007-08. Maynooth, Ireland: National University of Ireland, Maynooth, Faculty of Philosophy. https://www.coimisineir.ie/userfiles/files/PDFFile%2C15645%2Cen.pdf.

- McCárthaigh, S. 2021. “Number of Primary School Pupils Taught Through Irish at Record Level.” The Irish Times, September 2. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/education/number-of-primary-school-pupils-taught-through-irish-at-record-level-1.4011570.

- Mermelshtine, R. 2017. “Parent–Child Learning Interactions: A Review of the Literature on Scaffolding.” British Journal of Educational Psychology 87 (2): 241–254. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjep.12147.

- Merrins-Gallagher, A., S. Kazmierczak-Murray, and R. Perkins. 2019. “Using Collaborative Teaching and Storybooks in Linguistically Diverse Junior Infant Classrooms to Increase Pupils’ Contributions to Story-Time Discussions.” INTO Teacher’s Journal 7 (1): 91–112.

- Moriarty, M. 2015. Globalizing Language Policy and Planning: An Irish Language Perspective. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Moriarty, M. 2017. “Developing Resources for Translanguaging in Minority Language Contexts: A Case Study of Rapping in an Irish Primary School.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 30 (1): 76–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2016.1230623.

- Murtagh, L. 2007. “Out-of-School Use of Irish, Motivation and Proficiency in Immersion and Subject-Only Post-Primary Programmes.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10 (4): 428–453. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb453.0.

- Murtagh, L., and F. Van der Silk. 2004. “Retention of Irish Skills: A Longitudinal Study of a School-Acquired Second Language.” International Journal of Bilingualism 8 (3): 279–302. https://doi.org/10.1177/13670069040080030701

- NCCA (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment). 2008. National Curriculum Review, Phase 2 – Research Report No. 7. http://www.ncca.ie/en/Publications/Reports/Primary_Curriculum_Review,_Phase_2_Final_report_with_recommendations.pdf.

- NCCA (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment). 2019. The Primary Languages Curriculum / Curaclam Teanga na Bunscoile. Dublin: NCCA. https://curriculumonline.ie/getmedia/2a6e5f79-6f29-4d68-b850-379510805656/PLC-Document_English.pdf.

- NCCA (National Council for Curriculum and Assessment). 2023. Primary Curriculum Framework: For Primary and Special Schools. https://www.curriculumonline.ie/getmedia/84747851-0581-431b-b4d7-dc6ee850883e/2023-Primary-Framework-ENG-screen.pdf.

- Ní Chróinín, D., S. Ní Mhurchú, and T. J. Ó Ceallaigh. 2016. “Off-Balance: The Integration of Physical Education Content Learning and Irish Language Learning in English-Medium Primary Schools in Ireland.” Education 3-13 44 (5): 566–576. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004279.2016.1170404.

- Ní Loingsigh, D., and M. Mozzon-McPherson. 2020. “Advising in Language Learning in a New Speaker Context: Facilitating Linguistic Shifts.” System 95: 102363–102364. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2020.102363.

- Ó Caollaí, É. 2022. “Irish Gains Full Official and Working Status in the EU.” Irish Times, January 1. https://www.irishtimes.com/news/ireland/irish-news/irish-gains-full-official-and-working-status-in-the-eu-1.4767303.

- Ó Duibhir, P. 2018. Immersion Education: Lessons from a Minority Context. Bristol: Multilingual Matters.

- Ó Duibhir, P. 2023. “Claims That Cutting Irish Teaching Hours Will Aid Language Defies Logic.” Irish Times, May 17. https://www.irishtimes.com/ireland/education/2023/05/17/claim-that-cutting-irish-teaching-hours-will-aid-language-acquisition-defies-logic/.

- Ó Duibhir, P., and J. Cummins. 2012. Towards an Integrated Language Curriculum in Early Childhood and Primary Education (3-12 Years). Dublin: NCCA.

- Ó Duibhir, P., and L. Ní Thuairisg. 2019. “Young Immersion Learners’ Language Use Outside the Classroom in a Minority Language Context.” AILA Review 32 (1): 112–137. https://doi.org/10.1075/aila.00023.dui.

- Ó Laoire, M. 2007. “An Approach to Developing Language Awareness in the Irish Language Classroom: A Case Study.” International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism 10 (4): 454–470. https://doi.org/10.2167/beb454.0.

- Ó Murchadha, N., and B. Migge. 2017. “Support, Transmission, Education and Target Varieties in the Celtic Languages: An Overview.” Language, Culture and Curriculum 30 (1): 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2016.1230621.

- Ó Riagáin, P. 1997. Language Policy and Social Reproduction: Ireland 1893–1993. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Ó Riagáin, P. 2008. “Irish-language Policy 1922-2007: Balancing Maintenance and Revival.” In A New View of the Irish Language, edited by C. Nic Pháidín and S. Ó Cearnaigh, 55–65. Dublin: Cois Life.

- Owens, M. 1992. The Acquisition of Irish: A Case Study. Bristol, UK: Multilingual Matters.

- Romaine, S. 2008. “Irish in the Global Context.” In A New View of the Irish Language, edited by C. Nic Pháidín and S. Ó Cearnaigh, 11–25. Dublin: Cois Life.

- Swain, M. 1995. “Three Functions of Output in Second Language Learning.” In Principle & Practice in Applied Linguistics: Studies in Honour of H. G. Widdowson, edited by G. Cook and B. Seidlhofer, 125–144. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- UNESCO. 2019. UNESCO Interactive Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger: Irish. Accessed December 15, 2019. https://www.unesco.org/languages-atlas/index.php.

- Van Dongera, R., C. Van der Meer, and R. Sterk. 2017. Minority Languages and Education: Best Practices and Pitfalls. Brussels: European Parliament, Policy Department for Structural and Cohesion Policies. Accessed September 4, 2018. https://www.europarl.europa.eu/RegData/etudes/STUD/2017/585915/IPOL_STU(2017)585915_EN.pdf.

- Walsh, J. 2022. One Hundred YYears of Irish Language Policy 1922-2022. Oxford, UK: Peter Lang.