?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

To ensure students receive the best possible education, many education systems worldwide have implemented school inspections. These inspections serve as a powerful tool to assess and improve educational standards, and to hold schools accountable for their performance. Despite the prevalence of school inspection, there is a dearth of quantitative evidence from high accountability inspection systems pertaining to teachers’ perspectives on the relative occurrence of school improvement-related consequences of inspections versus inspection consequences for teachers’ emotional wellbeing, and the factors that influence these outcomes. Therefore, the current exploratory study sought to address this gap by investigating these issues in Northern Ireland – a high accountability context. Responses to an online survey of post-primary teachers indicated the perceived emotional fallout from school inspections outweighed their perceived school improvement-related benefits, and that the perceived emotional impact was greater for female than male teachers. Based on the evidence uncovered in the study, suggestions are proffered for potential changes to high accountability school inspection protocols which would optimise the potential for school improvement, while simultaneously minimising the harmful, emotional side-effects of inspections.

1. Introduction

In the realm of education, the call for quality and accountability resonates louder than ever. To ensure that students receive the best possible education, many education systems around the world have implemented school inspections to serve as a powerful tool to assess and improve educational standards, and to hold schools accountable for their performance. However, amidst the ongoing debates and controversies surrounding school inspections, the effectiveness and true impact of these evaluations remain shrouded in ambiguity. Specifically, some international evidence casts doubt on the extent to which contemporary school inspections, in their current form, can significantly influence school improvement (Gaertner, Wurster, and Pant Citation2014; Hofer, Holzberger, and Reiss Citation2020). Although Gaertner, Wurster, and Pant (Citation2014) dispute the extent to which inspections place teachers under emotional strain, there is a proliferation of evidence to the contrary (e.g. Gray and Gardner Citation1999; Penninckx et al. Citation2016a; Penninckx and Vanhoof Citation2015). However, it is notable that most studies in this area have employed qualitative rather than quantitative methodologies.

In England, the recent suicide of a head teacher, Ruth Perry, following a school inspection, has led to a great deal of public debate about the emotional turmoil precipitated by school inspections, and mechanisms for alleviating it. Ms Perry’s family attributed her death to the stress and anxiety associated with an inspection of her school (Jeffreys, Almroth-Wright, and Stafford Citation2023), and there were widespread calls for reform of the inspection system (Johnson Citation2023; Matthews Citation2023). Nevertheless, the body responsible for inspections in the jurisdiction (the Office for Standards in Education [Ofsted]) defended their important role in monitoring and raising educational standards (ITV News Citation2023). Although the overwhelming response to Ms Perry’s suicide was critical of Ofsted’s approach to school inspections, Finkelstein (Citation2023) contended that, in isolation, Ms Perry’s death does not represent a convincing case for the reform of inspections. However, it is important to note that at least eight other teacher deaths have been linked to the emotional fallout from Ofsted inspections (Waters and McKee Citation2023), which suggests that the impact of inspections on teachers’ emotional wellbeing cannot be overlooked in the manner implied by Finkelstein (Citation2023). Furthermore, it has been suggested that school inspections may exacerbate the teacher recruitment and retention crisis in England and other international contexts (Bousted Citation2022; Perryman Citation2022). Accordingly, the magnitude of the emotional impact of inspections in relation to their school improvement-related consequences is placed under scrutiny in the current article since this aspect of school inspection research has received limited attention in existing quantitative research involving surveys of teachers, particularly in high accountability inspection contexts such as the United Kingdom.

By exploring post-primary teachers’ perspectives on the consequences of school inspections in another jurisdiction within the United Kingdom, Northern Ireland, the current exploratory study was designed to use a mainly quantitative approach to investigate the benefits, challenges, and potential areas for improvement of school inspections within the province. There is a dearth of quantitative evidence from high accountability inspection systems pertaining to teachers’ perspectives on the relative occurrence of school improvement-related consequences of inspections versus the inspection consequences for teachers’ emotional wellbeing, and the factors that influence these outcomes. Therefore, the current study sought to address this gap by investigating these issues in the Northern Ireland context.

The Northern Ireland education system is complex, with a relatively large number of bodies involved in the management and administration of schools (Perry Citation2016). The school system reflects broader societal divisions, as Catholics and Protestants typically attend separate schools with those of the same religion. However, there is a small integrated sector which enrols around 8% of students (DENI Citation2023; Perry Citation2016). Northern Ireland also has an academically selective post-primary education system, whereby some students are selected on the basis of ability to attend academically oriented selective schools, while the remainder are educated in non-selective post-primary schools. Academic selection for post-primary education is, however, a highly contentious issue in the jurisdiction, where it has persisted despite its potential negative consequences. Although academic selection is purported to promote social mobility, there is evidence to suggest that it effectively leads to the segregation of students by social class at post-primary level, with the majority of those attending selective schools coming from more socially privileged backgrounds (Brown et al. Citation2021).

Based on the evidence uncovered in the study, the article proffers suggestions for potential changes to high accountability school inspection protocols which would optimise the potential for school improvement, while simultaneously minimising the harmful, emotional side-effects of inspections.

2. Literature review

2.1. Purpose of school inspections

School inspections have gained greater prominence since the beginning of the twenty-first century because of an increasing tendency to give schools greater autonomy in relation to their provision, coupled with more emphasis on holding them accountable for their actions (OECD Citation2013). Penninckx and Vanhoof (Citation2015, 478) define school inspection as:

… an evaluation of the quality of a school, including (minimally) a site visit, leading to a summative judgement on whether the quality of the school is meeting the expected standards, by persons with specific expertise who are neither directly nor indirectly involved in the school.

The school improvement dimension of inspections can be conceptualised in different ways. For example, school improvement could be characterised as a vehicle for enhancing a school’s policies and practices, or as a means of improving teachers’ professionalism (Penninckx and Vanhoof Citation2015). Whilst these may be important facets of school improvement, a more pertinent aspect of it relates to enhancing the educational outcomes of all students, while simultaneously reducing attainment gaps between high and low-performing schools (Faubert Citation2009). The accountability function of inspections, on the other hand, is concerned with furnishing information to policymakers, and the public at large, about the quality of a school’s educational provision, its compliance with relevant policies, and the overall value for money provided by the school (OECD Citation2013). The global influence of neoliberalism has led to the transition from bureaucratic accountability to market-driven accountability as parents are afforded greater choice in their children’s education (Faubert Citation2009). Some countries, such as the United Kingdom, have attempted to create a competitive market for school places as a means of improving the standard of educational provision within schools. In school systems such as these, which support parental choice, inspection reports are purported to play an important role in ensuring parents have access to robust information to support their decision-making. However, recent research has shown that parents do not find school inspection reports in England to be particularly useful for informing school choice decisions (Bokhove, Jerrim, and Sims Citation2023a). In a recent survey of parents’ feelings about school inspections conducted by Ofsted, just 25% of parents agreed that inspection reports assist them in identifying the strengths and weaknesses of a school, while a mere 13% of parents believed that inspection reports accurately assess school performance (Parentkind Citation2023).

Different inspection systems may place varying levels of emphasis on the accountability and school improvement dimensions of school evaluation. For example, some systems may attach a high level of importance to the accountability function of inspections, while others place greater emphasis on the school improvement function. Such inspection regimes can be described as high accountability and low accountability systems, respectively. High accountability systems, such as those in England and Northern Ireland, embrace public reporting of inspection results, which can have a substantial impact on the public image of a school and its competitiveness (Ehren Citation2016a). In low accountability inspection systems, on the other hand, inspection outcomes have limited consequences for schools, and the insights gleaned from the inspection are valued because of their potential to guide school improvement. However, since many inspection systems are expected to achieve both the accountability and school improvement functions of inspection (Gaertner, Wurster, and Pant Citation2014), this can lead to tensions between the two functions (De Grauwe Citation2007). In some jurisdictions, including England and Northern Ireland, there has been a move towards self-evaluation as a possible means of resolving the conflict between the two purposes of inspection (De Grauwe Citation2007). Self-evaluation requires school staff to reflect on their professional practice and to identify potential actions to stimulate school improvement, for example through the creation of a school development plan and associated action plans.

2.2. Improving schools or generating negative emotions? – The consequences of school inspection

2.2.1. School improvement-related consequences

The ‘instrumental effects’ of inspections refer to the school improvement-related actions taken based on inspection feedback (Ehren Citation2016b). Although some research suggests inspections have limited instrumental effects (Penninckx et al. Citation2014), most research in this area tends to argue that inspection has positive effects on school improvement, such as improvements to lesson monitoring and changes to teaching strategies (e.g. Gray and Gardner Citation1999; Lee-Corbin Citation2005). Crucially, however, instrumental effects tend to vary according to the overall verdict of the inspection, with greater effects for negative inspection verdicts (Matthews and Sammons Citation2005; Penninckx et al. Citation2016b).

The extant empirical research also shows a lack of consensus regarding the impact of inspections on students’ learning outcomes. For example, some studies have demonstrated a link between negative inspection judgements and subsequent improvements in students’ academic attainment (e.g. Allen and Burgess Citation2012; Hussain Citation2012). On the other hand, Rosenthal (Citation2004) reported an adverse impact on students’ achievement levels in the year of the inspection. This performance dip could be attributed to teaching staff focusing more on achieving a positive result in terms of inspection requirements pertaining to standards and benchmarking rather than student success. Indeed, Jones et al. (Citation2017) found that the performance pressures associated with inspections could lead to the narrowing of school curricula and pedagogical approaches.

2.2.2. Emotional consequences

A substantial body of empirical research has investigated the emotional consequences of inspections for teaching staff, with many studies reporting that inspections have a negative impact on teachers’ personal lives. For example, Woods and Jeffrey (Citation1998, 561) found that inspections effectively led to the ‘colonization of life’ for teachers because of the gravity of inspection impact on both their professional and personal lives. This colonization caused considerable stress and physical manifestations of stress, with some teachers reporting they had been ‘put through hell’ (Woods and Jeffrey Citation1998, 562) because of inspections. Indeed, Perryman (Citation2007) concluded that the emotional fallout from inspections extends beyond the commonly reported issues relating to stress and anxiety (Chapman Citation2001; Gray and Gardner Citation1999) and can entail teachers perceiving they are constantly under an oppressive regime, thus leading to feelings of fear and disaffection. These views are supported by the findings of Penninckx et al. (Citation2016a), who reported that teachers participating in a study of the relatively low accountability Flemish inspection system experienced moderate to severe stress and anxiety either before, during or after an inspection. As Perryman (Citation2007, 188) noted, ‘this perhaps calls into question the whole issue of seeking school improvement by way of a system which creates such a negative emotional impact’.

2.2.3. Factors influencing inspection consequences

Several factors have been shown to influence the occurrence of both positive and negative consequences of school inspections. For example, the inspection outcome has been found to be correlated with both school improvement-related and emotional effects of inspections (Penninckx Citation2017). Less favourable inspection outcomes have been linked to both greater impacts on school improvement (Penninckx et al. Citation2016b) and higher post-inspection stress and anxiety levels for school staff (Penninckx et al. Citation2016a). However, it is worrying that Bokhove, Jerrim, and Sims (Citation2023b) found some inconsistencies in inspection judgements between different inspectors in their study of over 30,000 inspections conducted in England from 2011 to 2019. Therefore, personal characteristics of inspectors, such as their gender, can have a bearing on the ultimate inspection outcome, which suggests there may be variation in the outcome that a given school receives depending upon who conducts the inspection. The perceived quality of an inspection, i.e. the perceived professionalism, transparency and accuracy associated with the inspection process, has been similarly linked to inspection consequences. Penninckx et al. (Citation2016b) suggested that greater instrumental effects occur for inspections judged to be of high quality, while adverse emotional consequences are more likely for inspections that are perceived to be of low quality. The position that a staff member holds within a school has been shown to influence their perceptions of inspection consequences, with members of senior leadership teams more likely to report greater instrumental effects than ordinary classroom teachers (Brimblecombe, Shaw, and Ormston Citation1996). Significantly though, female teachers, regardless of position, reported ‘feeling more worried and less confident than their male counterparts’ in response to inspection (Brimblecombe, Ormston, and Shaw Citation1996, 34). Whilst school type also potentially plays a role in the response to inspections, a systematic review suggests the need for further research (Hofer, Holzberger, and Reiss Citation2020). Finally, the supportiveness of a school’s senior leadership team in helping staff to prepare for an inspection, and to deal with its consequences, have been shown to have a bearing on the effects and side-effects of the inspection (Penninckx Citation2017).

2.3. School inspections in Northern Ireland

School inspections in Northern Ireland can be traced to the inspectorate that was established in 1832 by The Commissioners of National Education in Ireland. However, the current school inspection system is managed by the Education and Training Inspectorate (ETI), which was inaugurated in 1989 under the auspices of the Department of Education in Northern Ireland to provide inspection services for schools and other related youth and training organisations. According to ETI (Citation2017a, 2), the purpose of inspection is ‘to promote the highest possible standards of learning, teaching and achievement throughout the education, training and youth sectors.’ Prior to the establishment of the Northern Ireland Assembly in 1999, ETI inspections were largely modelled on the English system for school inspections employed by Ofsted. However, since devolution, inspection policy in Northern Ireland has diverged from English policy in the sense that considerable emphasis has been placed on the potential of inspections to drive the school improvement agenda (McGuinness Citation2012). Nevertheless, ETI inspections still entail a strong focus on accountability and the public reporting of inspection findings, thus warranting the description of them as high stakes.

The inspection process has evolved over time, but it currently entails on-site visits to evaluate school effectiveness, in addition to an assessment of the extent to which self-evaluation is used effectively to inform school development planning as a means of bringing about improvement. The current framework utilised by ETI, known as the Inspection and Self Evaluation Framework, was introduced in 2017, and seeks to evaluate a school’s work in the following domains: outcomes for learners; quality of provision; leadership and management; ensuring school governance, care and support, and safeguarding/child protection (ETI Citation2017b). Evaluations of the school’s work in these domains (on a six-level scale from ‘outstanding’ to ‘requires urgent improvement’) contribute to an assessment of its overall effectiveness based on one of the following four descriptors:

The organisation has a high level of capacity for sustained improvement in the interest of all the learners.

The organisation demonstrates the capacity to identify and bring about improvement in the interest of all the learners.

The organisation needs to address (an) important area(s) for improvement in the interest of all the learners.

The organisation needs to address urgently the significant areas for improvement identified in the interest of all the learners.

Various forms of follow-up occur depending upon the outcome of an inspection. These range from a ‘sustaining improvement inspection’, conducted around three years after a full inspection, for those schools that are assessed as having either a high capacity or a capacity to effect improvement, to a ‘follow-up inspection’, within 12–24 months of the initial inspection, for those schools identified as needing to address areas for improvement. All inspection reports are published on the ETI website (ETI Citation2019). However, for a period following the introduction of the current inspection framework in 2017, inspections were impacted by teachers’ industrial action in most Northern Ireland schools. This meant that, although ETI visits took place, evaluations of school effectiveness could not proceed as normal, thus preventing normal reporting of inspection outcomes (Munoz-Chereau and Ehren Citation2021).

3. Aim of current study, research questions, and conceptual framework

There is currently limited quantitative evidence from high accountability inspection systems relating to teachers’ perspectives on the balance between school improvement-related and personal/emotional consequences of inspections. Therefore, the aim of the current study was to investigate, in the high accountability Northern Ireland context, the relative occurrence of school improvement-related consequences of inspections versus the impact of inspections on teachers’ personal/emotional wellbeing, and the factors that influence these outcomes.

The specific research questions that guided the study were:

What are teachers’ perspectives on the impact of school inspections on school improvement-related activities?

What are teachers’ perspectives on the personal/emotional consequences of school inspections?

What factors influence teachers’ perspectives on the consequences of school inspections?

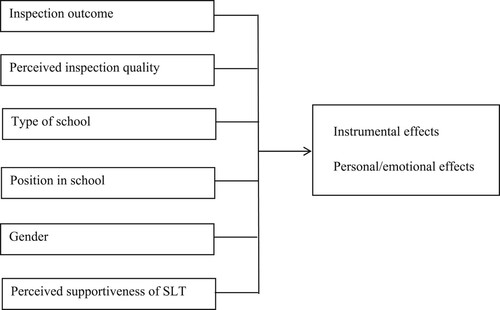

To facilitate analysis of the empirical data from the research, a conceptual framework was constructed based on the above review of pertinent literature on the consequences of inspections, and the factors influencing them. The framework overlaps significantly with that proposed by Penninckx (Citation2017) in terms of explanatory characteristics (the six factors on the left side of ) and the effects of inspection (on the right side of ). The study sought to investigate teachers’ perspectives on the following consequences of school inspections:

Instrumental effects, i.e. the decisions made because of inspection, and the actions for improvement taken based on those decisions

Personal/emotional effects.

The influence of the following factors on these effects was investigated in the study:

Inspection outcome – the nature of the overall inspection judgement

Perceived inspection quality – the perceived professionalism, transparency and accuracy associated with the inspection process

Type of school – Selective or non-selective

Position in school – Senior Leadership Team (SLT) member versus non-SLT member

Gender – Male or female

Perceived supportiveness of the SLT in helping staff to prepare for inspection, and to deal with its consequences.

4. Methodology

4.1. The study

The current study entailed an online survey of all post-primary teachers in Northern Ireland, which was conducted in early 2019. The questionnaire used in the survey was designed to garner demographic information relating to the participants in addition to data pertaining to the potential explanatory characteristics for the consequences of inspections. Furthermore, the questionnaire also included scales to measure both the instrumental and personal/emotional effects of inspections. These measurement scales were based on the scales used by Penninckx et al. (Citation2016a) but amended to suit the Northern Ireland context of the study. The research was conducted in line with the research governance regulations of Queen’s University Belfast, and the study was approved by the research ethics committee of the University’s School of Social Sciences, Education and Social Work.

4.2. Participants and sampling

The survey was completed by a sample of 102 Northern Irish post-primary teachers, from a population of approximately 9,607 post-primary teachers (DENI Citation2019) at all levels of the school hierarchy. The participation rate (1.1%) was negatively impacted by the industrial action that was ongoing at the time when the questionnaire was distributed, as teachers had been instructed by their unions to only perform core duties associated with their contracts of employment. Nevertheless, the sample of 102 was deemed to be large enough for meaningful statistical analysis and to facilitate the drawing of valid inferences from the survey data (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007). The sample included both male and female teachers, although males were slightly over-represented in the sample, as indicated in the results section of the paper. Reflecting the nature of post-primary provision in Northern Ireland, where academic selection has been retained, teachers from both the selective and non-selective sectors featured in the sample, but the selective sector was over-represented (see results section).

4.3. Data collection

Several variables were collected by the online questionnaire. These included demographic variables such as gender, school type, subject(s) taught, and position held within the school. Possible factors influencing inspection consequences were also garnered by the questionnaire, including the inspection outcome of the last inspection experienced by the respondent that was fully reported on, the perceived quality of the inspection, and the perceived supportiveness of the school’s senior leadership team. Finally, a range of variables pertaining to the instrumental effects and emotional consequences of the last relevant inspection experienced by the respondent were collected. Further details about the variables collected in the survey are included in Appendix 1.

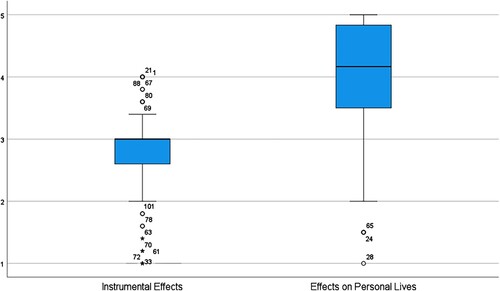

4.4. Data analysis

Cronbach’s alpha was calculated to assess the reliability of the multi-item scales used to measure both instrumental effects and effects on personal lives. The calculated values of 0.88 and 0.92 for instrumental effects and effects on personal lives, respectively, confirmed that both scales were highly reliable (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007). For each scale, the median, lower and upper quartiles, and interquartile range of participants’ scores were calculated, and associated boxplots were generated to summarise the relevant distributions. This approach was adopted rather than calculating means and standard deviations since the distributions of scores for both scales were skewed. In addition, the percentages of participants who either agreed, or strongly agreed, with each statement within the multi-item scales were calculated.

To further investigate the impact of inspections on teachers’ emotional wellbeing, an analysis was undertaken of the stress and anxiety-related variables garnered by the questionnaire. For both stress and anxiety, the percentages of respondents who indicated they experienced no; minor; some; considerable; or major emotional impact, were calculated at four time points: a normal school day, without inspection; two weeks before inspection; during inspection; and two weeks after inspection. Given the ordinal nature of the data, non-parametric Wilcoxon signed-rank tests were used to test for differences between the respondents’ assessments of their emotional state two weeks before, during, and two weeks after the inspection, relative to their emotional state on a normal school day (Connolly Citation2007). In addition to performing the Wilcoxon tests, effect sizes were calculated to yield a standardised way of quantifying any difference between the emotional states at the three chosen time points (two weeks before, during, and two weeks after inspection) and corresponding emotional states on a normal school day. For each Wilcoxon test, the values of Z, p, and effect size, r, are reported in respect of the three time points of interest, where effect sizes were calculated using the formula , with n = number of cases, as recommended by Connolly (Citation2007). Effect sizes are considered to be small if

, medium if

, and large if

.

Finally, multiple linear regression analyses were performed to investigate the influence of the following variables on both instrumental effects (InstrumEffect) and effects on personal lives (PersLifeEffect): type of school (SchoolType), gender (Gender), position in school (PositionSchool), inspection outcome (InspOutcome), perceived inspection quality (InspQual), perceived supportiveness of principal/SLT (SLTSupport).

All statistical calculations were performed using SPSS version 27.

5. Results

5.1. Demographic and other explanatory variables

Of the 102 respondents who completed the online survey, 59.8% (69.5%) were female and 40.2% (30.5%) were male, where the figures in brackets represent the percentages of each gender in the population. In addition, 65.7% (41.9%) of the sample were teaching in the selective sector at the time of the inspection, while 34.3% (58.1%) of respondents were teaching in non-selective post-primary schools (DENI Citation2019). Participants represented a wide gamut of subject disciplines, including Biology, Business Studies, Drama, English, Geography, History, ICT, Mathematics, and Religious Studies. Furthermore, 21.6% of respondents were members of the school SLT, while 78.4% were non-SLT members at the time of the inspection. summarises the percentages of respondents who indicated each possible response to the questions relating to inspection outcome, perceived inspection quality, and perceived SLT supportiveness. It is apparent from that each of these questions attracted a range of responses.

Table 1. Percentages of participants giving each response to questions relating to inspection outcome, perceived inspection quality, and perceived SLT supportiveness.

5.2. Teachers’ perspectives on the impact of school inspections on school improvement-related activities versus personal/emotional consequences

The median (Q2), lower and upper quartiles (Q1 and Q3, respectively), and interquartile range (IQR) of participants’ scores on the instrumental effects and effects on personal lives scales are presented in . This table also includes the percentages of participants who either agreed, or strongly agreed, with each statement within the two multi-item scales. The distributions of the participants’ scores for the two measurement scales are summarised in the boxplots presented in . Outliers, i.e. cases where the value of the scale variable is more than one and a half times the interquartile range below the lower quartile or above the upper quartile, are represented by circles in the boxplots. However, extreme outliers, i.e. cases where the scale variable is greater than three times the interquartile range below the lower quartile or above the upper quartile, are marked with asterisks.

Figure 2. Boxplot showing distributions of scores for ‘instrumental effects’ and ‘effects on personal lives’.

Table 2. Summary statistics for ‘instrumental effects’ and ‘effects on personal lives’ scales.

The results in and demonstrate that the median value of the perceived effects on personal lives scale is considerably higher than the median of the perceived instrumental effects scale, but that there was greater variability in the perceived effects on personal lives than the perceived instrumental effects, as demonstrated by the interquartile ranges. Furthermore, the percentages of participants who either agreed, or strongly agreed, with each statement within the multi-item scales were substantially greater for perceived effects on personal lives than for perceived instrumental effects. Therefore, this suggests that the teachers who completed the questionnaire believed the detrimental impact of inspections on their personal lives outweighed any school improvement-related effects of inspections. Participants were further invited to articulate their perspectives on the effects of inspections on school improvement. In open questions, participants were invited to explain whether they considered inspection to have improved the school and, echoing earlier findings (see McNamara and O’Hara Citation2006), teachers were largely unconvinced of the link. The comments below capture the overriding sense of scepticism that resonated through the responses:

I believe the inspection had no impact on the learning of pupils nor on their performance. (female, non-SLT member)

Pupils continued to experience the quality teaching they had prior to the ETI visit, outcomes were satisfactory and stayed the same. (female, SLT member)

Improvements made to pupil performance were more in spite of, rather than because of, the ETI inspection. (male, non-SLT member)

Table 3. Impact of inspection on stress levels.

summarises the numbers and percentages of respondents who indicated they experienced no, minor, some, considerable, or major levels of anxiety at four different time points: normal school day (without inspection), two weeks before, during, and two weeks after the inspection. It also summarises the results of the Wilcoxon tests on levels of anxiety at the three time points of interest (two weeks before, during, and two weeks after inspection) relative to anxiety levels on a normal school day. The results indicate that, in the absence of inspection, on a normal school day, only 2.0% of respondents experienced considerable or major levels of anxiety. However, this increased to 50% two weeks before the inspection, 78.5% during the inspection, before dropping to 28.4% two weeks after the inspection. The Wilcoxon tests at all three time points (two weeks before, during, and two weeks after inspection) were statistically significant at the 1% level (p < 0.01), thus indicating that respondents experienced greater levels of anxiety at all three time points relative to what they experienced on a normal school day. The increase in anxiety levels relative to a normal school day was particularly large two weeks before and during the inspection, as indicated by the effect sizes of 0.763 and 0.829, respectively. Nevertheless, relative to a normal school day, participants still experienced high anxiety levels two weeks post-inspection, as shown by the effect size of 0.552.

Table 4. Impact of inspection on anxiety levels.

In line with many existing studies (e.g. Gray and Gardner Citation1999; Penninckx et al. Citation2016a; Penninckx and Vanhoof Citation2015), responses to the open-ended question on personal life/emotional effects indicated a consensus view that inspections led to considerable stress and anxiety for teachers at all levels of responsibility:

I found the process emotionally and physically draining, the impact of which was felt beyond my professional life and negatively influenced by personal life. (female, SLT member)

I found it to be a thoroughly divisive and stressful period of my career. (male, non-SLT member)

5.3. Factors influencing teachers’ perspectives on the consequences of school inspections

and summarise the results of the multiple linear regression analyses that were performed to investigate the influence of the following variables on both instrumental effects (InstrumEffect) and effects on personal lives (PersLifeEffect), respectively: type of school (SchoolType), gender (Gender), position in school (PositionSchool), inspection outcome (InspOutcome), perceived inspection quality (InspQual), perceived supportiveness of principal/SLT (SLTSupport). The multiple linear regression model did not significantly predict instrumental effects at the 5% level, F(6,95) = 1.191, p = 0.318, adj. R2 = 0.011. None of the six independent variables added significantly to the prediction at the 5% level. However, the multiple linear regression model did significantly predict effects on personal lives at the 0.1% level, F(6,95) = 4.615, p = 0.000, adj. R2 = 0.177. Nevertheless, just two variables, gender, and the perceived supportiveness of the principal/SLT, added statistically significantly to the prediction at the 1% and 5% levels, respectively. The positive value of the gender regression coefficient, 0.574, indicates that female teachers perceived inspections to have greater adverse effects on their personal lives than their male counterparts. However, the negative value of the perceived supportiveness of the principal/SLT coefficient, −0.187, suggests that more supportive principals/SLTs reduced the detrimental impact of inspections on teachers’ personal lives.

Table 5. Multiple linear regression results for instrumental effects.

Table 6. Multiple linear regression results for effects on personal lives.

6. Discussion and conclusions

6.1. Discussion of research questions

6.1.1. What are teachers’ perspectives on the impact of school inspections on school improvement-related activities?

The results of our analysis demonstrated that teachers generally held neutral or negative views regarding the impact of inspections on school improvement-related activities, and there was a reasonable degree of consistency in their perspectives. However, it is important to note that a small number of teachers held extremely negative views regarding the potential of inspections to lead to positive actions for school improvement, as demonstrated by both their responses to the items contributing to the ‘instrumental effects’ scale and their qualitative comments. For example, 30.4% of teachers either disagreed or strongly disagreed that inspections led to actions that were beneficial for students. These findings tend to support the contention of Penninckx et al. (Citation2014) that, in some contexts, inspections lead to minimal benefits in relation to school improvement. Nevertheless, it is important to note that some teachers did highlight inspection-related benefits in their responses to the relevant open-ended question, as illustrated by the male head of department who claimed that the inspection ‘probably helped us to improve upon the ways in which we used data, thereby helping to inform students better in relation to tracking/setting targets’.

6.1.2. What are teachers’ perspectives on the personal/emotional consequences of school inspections?

Participants in the study generally indicated that inspections had considerable deleterious consequences for teachers’ personal and emotional wellbeing, although there was greater variability in their perspectives than for school improvement-related inspection effects. It is noteworthy that, for most of the items in the ‘effects on personal lives’ scale, over 75% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that inspection had a negative impact on their personal lives. By contrast, for most of the items in the ‘instrumental effects’ scale, less than 10% of respondents either agreed or strongly agreed that inspection led to positive actions for school improvement. Therefore, participants in this study generally believed that the negative impact of inspections on their personal lives outweighed any school improvement-related benefits. The analysis of teachers’ perceived stress and anxiety levels immediately before, during, and immediately after inspections suggested that the process tends to take a considerable emotional toll on teachers, with lingering adverse consequences for their emotional wellbeing post-inspection. These findings resonate with the large body of literature pertaining to the adverse impact of inspections on teachers’ emotional wellbeing (e.g. Chapman Citation2001; Gray and Gardner Citation1999; Penninckx et al. Citation2016a; Perryman Citation2007; Woods and Jeffrey Citation1998). Again, it is important to observe that, although the consensus was that inspections had negative emotional consequences for teachers, a very small minority of participants indicated an alternative, more positive perspective.

6.1.3. What factors influence teachers’ perspectives on the consequences of school inspections?

In the current study, there was no apparent relationship between teachers’ perspectives on the school improvement-related consequences of inspections and the six factors that feature in the conceptual framework: type of school, gender, position in school, inspection outcome, perceived inspection quality, and perceived supportiveness of principal/SLT. However, both gender and the perceived supportiveness of SLT were found to have a bearing on the impact of inspections on teachers’ personal lives. Female teachers reported greater adverse consequences for their personal wellbeing than male teachers, and more supportive SLTs were associated with reduced perceived negative impacts on teachers’ personal wellbeing. No link was established between inspection outcome, perceived inspection quality, school type or position held in school, and consequent perceived inspection impact on teachers’ personal lives. A key finding, particularly in the light of current United Kingdom debates about the negative effects of inspection on head teachers, is that the inspection process induces particularly negative effects for the wellbeing of female teachers. It has already been recognised that males and females differ in their perception and reaction to stressful events in the workplace (Kreuzfeld and Seibt Citation2022), but a mechanism of evaluation and inspection which intensifies feelings of stress and anxiety for female teachers in a female-dominated profession requires further consideration.

6.2. Limitations of study and future research directions

It is important to acknowledge some limitations which impacted on this exploratory study. The most significant of these was ongoing industrial action by teachers at the time the research was conducted, which prohibited involvement in activities beyond the remit of their contracts, and consequently this meant that many teachers did not respond to the survey (Munoz-Chereau and Ehren Citation2021). Whilst the number of respondents (102) exceeds the minimum recommended sample size for meaningful statistical analysis (Cohen, Manion, and Morrison Citation2007), it is also clear that a higher return rate would have strengthened the statistical power of the analysis.

Furthermore, the fact that participants were asked to use self-rating scales to indicate their perceptions of an inspection that could have occurred some years previously may have compromised the validity and reliability of the survey findings. In addition, there are well-documented difficulties pertaining to the accuracy of teachers’ perceptions of their professional efficacy (e.g. Faddar, Vanhoof, and De Maeyer Citation2018; Wisniewski, Röhl, and Fauth Citation2022), which may lead to a belief that their professional practice is being unfairly criticised by inspectors. However, it is important to note that teachers’ perceptions of the consequences of inspections, whether they are accurate and/or warranted, are likely to have an important bearing on their emotional response to inspections. Given the number of teacher suicides that have been linked to the emotional fallout from school inspections within the high accountability inspection regime in England (Waters and McKee Citation2023), it would be prudent to take teachers’ perceptions seriously.

Future research concerning teachers’ perspectives on the consequences of school inspections in high accountability systems should focus on attempting to recruit larger samples of participants. In addition, it would be beneficial to conduct longitudinal studies to garner both quantitative and qualitative evidence relating to the short-term, medium-term, and long-term effects of inspections in high accountability inspection systems. Moreover, future research efforts should focus on using participatory methods to involve teachers in the co-design of inspection protocols which maximise the benefits of inspections and minimise their adverse personal and emotional consequences. Promising work has already commenced in this area within the Northern Ireland context, as illustrated by the consultation that was undertaken with relevant stakeholders in 2022 and 2023 on the future development of ETI inspections (ETI Citation2023).

7. Conclusions

As alluded to above, co-design of inspection protocols with representative members of the teaching profession would be an appropriate response to the alarming findings uncovered by the current research. It is also suggested that, since self-evaluation is a vehicle for potentially resolving the conflict between the accountability and school improvement-related functions of inspections, the self-evaluation process is in urgent need of reform. For example, it is suggested that school inspectorates such as the ETI should work more collegially with schools to train and support relevant staff in the self-evaluation process, so that schools’ work in this area is robust and objective. In adopting a collegial approach, the inspectorate could also establish mentoring links between relevant staff in high-performing schools and those that are radically underperforming. Formal inspections by the inspectorate could then become much more light touch since they would amount to validating the findings reported in school self-evaluations, and only become more extensive in the event of serious concerns about the objectivity of a school’s self-evaluation. Finally, formally published inspection reports should refrain from using single word or phrase overall judgements about schools since the quality of educational provision is far too complex to be summarised in this manner. Indeed, there has been extensive discussion concerning this point in the media (e.g. Rawlinson Citation2023). A report card format that contains a range of descriptors in the wide gamut of areas that constitute a school’s provision would be preferable.

The study’s findings have important implications for educators, policymakers, and stakeholders, both in Northern Ireland and in other international contexts with high accountability inspection systems, in relation to understanding teachers’ perspectives on the power that school inspections hold in driving the school improvement agenda. Moreover, they also shed light on the negative impact of high accountability school inspections on teachers’ emotional wellbeing, which has been brought to the foreground of public debate by Ruth Perry’s death in England. Our study has shown that, from teachers’ perspectives, the emotional fallout from school inspections outweighs their school improvement-related benefits. It is also noteworthy that our findings suggest female teachers perceive the negative emotional consequences of inspections to be greater than their male colleagues report. Although further research is required, this finding is particularly noteworthy given current media debates about the effects of inspection on head teachers following the death of Ruth Perry in the aftermath of an Ofsted inspection. Accordingly, it is important for policymakers to urgently reflect on contemporary approaches to school inspections, and to give serious consideration to our suggested reforms. Against the backdrop of recent public debate in England, human life is too precious to do otherwise.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability statement

Data is available from the corresponding author upon request.

Additional information

Notes on contributors

Kathryn McClurg

Kathryn McClurg completed her Doctorate in Education at Queen’s University Belfast and holds a PQH (NI). She is a Vice Principal of a post-primary school in Northern Ireland where her primary responsibility is that of being the Pastoral lead.

Ian Cantley

Ian Cantley is a Senior Lecturer in Education at Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland. His current research interests are in mathematics education and the mathematical and philosophical foundations of educational measurement models. He has published numerous articles on both the philosophy of education and mathematics education. His work is particularly concerned with the theoretical assumptions that underpin contemporary approaches to educational assessment, methods for improving students’ mathematical learning experiences at school, and gender equity issues in mathematics.

Caitlin Donnelly

Caitlin Donnelly is a Senior Lecturer in Education at Queen’s University Belfast, Northern Ireland. Her research interests include education policy, school governance and intergroup relations in schools. She has published a range of articles and attracted funding to examine these issues and is currently examining the nature of school-based contact initiatives in schools.

References

- Allen, R., and S. Burgess. 2012. “How Should we Treat Under-Performing Schools? A Regression Discontinuity Analysis of School Inspections in England.” Working Paper No. 12/287. Centre for Market and Public Organisation, Bristol Institute of Public Affairs, University of Bristol, Bristol, UK. https://www.bristol.ac.uk/media-library/sites/cmpo/migrated/documents/wp287.pdf.

- Bokhove, C., J. Jerrim, and S. Sims. 2023a. “How Useful are Ofsted Inspection Judgements for Informing Secondary School Choice?” Journal of School Choice 17 (1): 35–61. https://doi.org/10.1080/15582159.2023.2169813.

- Bokhove, C., J. Jerrim, and S. Sims. 2023b. Are Some School Inspectors More Lenient Than Others? University of Southampton. https://eprints.soton.ac.uk/473908/1/WP_Inspector_Effects_FINAL_020223.pdf.

- Bousted, M. 2022. Support not Surveillance: How to Solve the Teacher Retention Crisis. Woodbridge, UK: John Catt Educational Ltd.

- Brimblecombe, N., M. Ormston, and M. Shaw. 1996. “Gender Differences in Teacher Response to School Inspection.” Educational Studies 22 (1): 27–40. https://doi.org/10.1080/0305569960220103.

- Brimblecombe, N., M. Shaw, and M. Ormston. 1996. “Teachers’ Intention to Change Practice as a Result of Ofsted School Inspections.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 24 (4): 339–354. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263211×9602400401.

- Brown, M., C. Donnelly, P. Shevlin, C. Skerritt, G. McNamara, and J. O'Hara. 2021. “The Rise and Fall and Rise of Academic Selection: The Case OfNorthern Ireland” Irish Studies in International Affairs 32 (2): 477–498. https://doi.org/10.1353/isia.2021.0060.

- Chapman, C. 2001. “Changing Classrooms Through Inspection.” School Leadership & Management 21 (1): 59–73. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632430120033045.

- Cohen, L., L. Manion, and K. Morrison. 2007. Research Methods in Education, 6th ed. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Connolly, P. 2007. Quantitative Data Analysis in Education: A Critical Introduction Using SPSS. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- De Grauwe, A. 2007. “Transforming School Supervision Into a Tool for Quality Improvement.” International Review of Education 53 (5-6): 709–714. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11159-007-9057-9.

- DENI. 2019. Teacher Workforce Statistics in Grant-Aided Schools in Northern Ireland, 2018/19 (Statistical Bulletin 5/2019). Bangor, NI: Department of Education. https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/education/Teacher%20Numbers%20and%20PTR%202018.19%20Statistical%20Bulletin%20-%20REVISED.pdf.

- DENI. 2023. Overview of key Education Statistics for 2022/23. Bangor, NI: Department of Education. https://www.education-ni.gov.uk/sites/default/files/publications/education/School%20Census%20Key%20Statistics%202022.23.pdf.

- Ehren, M. C. M. 2016a. “Introducing School Inspections.” In Methods and Modalities of Effective School Inspections, edited by M. C. M. Ehren, 1–16. New York, NY: Springer.

- Ehren, M. C. M. 2016b. “School Inspections and School Improvement; the Current Evidence Base.” In Methods and Modalities of Effective School Inspections, edited by M. C. M. Ehren, 69–85. New York, NY: Springer.

- Ehren, M. C. M., H. Altrichter, G. McNamara, and J. O’Hara. 2013. “Impact of School Inspections on Improvement of Schools—Describing Assumptions on Causal Mechanisms in six European Countries.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 25 (1): 3–43. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-012-9156-4.

- Ehren, M. C. M., and A. J. Visscher. 2006. “Towards a Theory on the Impact of School Inspections.” British Journal of Educational Studies 54 (1): 51–72. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-8527.2006.00333.x.

- ETI. 2017a. A Charter for Inspection. Bangor, NI: Education and Training Inspectorate. https://www.etini.gov.uk/sites/etini.gov.uk/files/publications/a-charter-for-inspection.pdf.

- ETI. 2017b. Inspection and Self-Evaluation Framework: Effective Practice and Self-Evaluation Questions for Post-Primary. Bangor, NI: Education and Training Inspectorate. https://www.etini.gov.uk/sites/etini.gov.uk/files/publications/the-inspection-and-self-evaluation-framework-isef-effective-practice-and-self-evaluation-questions-for-post-primary_1.pdf.

- ETI. 2019. What Happens After an Inspection: Pre-School, Nursery Schools, Primary, Post-Primary and Special Education. Bangor, NI: Education and Training Inspectorate. https://www.etini.gov.uk/sites/etini.gov.uk/files/publications/what-happens-after-inspection-nursery-schools-primary-post-primary-special-2019.pdf.

- ETI. 2023. Analysis of the Responses to the Education and Training Inspectorate's Consultation on the Development of Inspection: Working Draft (August 2023). Bangor, NI: Education and Training Inspectorate. https://www.etini.gov.uk/sites/etini.gov.uk/files/publications/analysis-of-the-responses-to-the-education-and-training-inspectorates-consultation-on-the-development-of-inspection_3.pdf.

- Faddar, J., J. Vanhoof, and S. De Maeyer. 2018. “School Self-Evaluation: Self-Perception or Self-Deception? The Impact of Motivation and Socially Desirable Responding on Self-Evaluation Results.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 29 (4): 660–678. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2018.1504802.

- Faubert, V. 2009. “School Evaluation: Current Practices in OECD Countries and a Literature Review.” OECD Education Working Papers No. 42. OECD Publishing, Paris. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED529650.pdf.

- Finkelstein, D. 2023. “We Can’t Blame Ofsted for Ruth Perry’s Death.” The Times, May 2, 2023. https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/we-cant-blame-ofsted-for-ruth-perrys-death-r6twcm8js.

- Gaertner, H., S. Wurster, and H. A. Pant. 2014. “The Effect of School Inspections on School Improvement.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 25 (4): 489–508. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2013.811089.

- Gray, C., and J. Gardner. 1999. “The Impact of School Inspections.” Oxford Review of Education 25 (4): 455–468. https://doi.org/10.1080/030549899103928.

- Hofer, S. I., D. Holzberger, and K. Reiss. 2020. “Evaluating School Inspection Effectiveness: A Systematic Research Synthesis on 30 Years of International Research.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 65: 100864. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2020.100864.

- Hussain, I. 2012. Subjective Performance Evaluation in the Public Sector: Evidence from School Inspections (CEE DP 135). London, UK: Centre for the Economics of Education, London School of Economics. https://cep.lse.ac.uk/pubs/download/CEE/ceedp135.pdf.

- ITV News. 2023. “Ofsted Says School Inspections Won't Stop After Death of Reading Headteacher Ruth Perry.” ITV News, March 24, 2023. https://www.itv.com/news/meridian/2023-03-24/school-inspections-wont-stop-after-headteachers-death-says-ofsted.

- Jeffreys, B., I. Almroth-Wright, and S. Stafford. 2023. “Ofsted: Head Teacher’s Family Blames Death on School Inspection Pressure.” BBC News, March 21, 2023. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-england-berkshire-65021154.

- Johnson, B. 2023. “‘Some Change Needs to Come of This’: Call for new School Inspection System After Headteacher’s Suicide.” Sky News, March 25, 2023. https://news.sky.com/story/some-change-needs-to-come-of-this-call-for-new-school-inspection-system-after-headteachers-suicide-12841996.

- Jones, K. L., P. Tymms, D. Kemethofer, J. O’Hara, G. McNamara, S. Huber, E. Myrberg, G. Skedsmo, and D. Greger. 2017. “The Unintended Consequences of School Inspection: The Prevalence of Inspection Side-Effects in Austria, the Czech Republic, England, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland, England, Ireland, the Netherlands, Sweden, and Switzerland.” Oxford Review of Education 43 (6): 805–822. https://doi.org/10.1080/03054985.2017.1352499.

- Kreuzfeld, S., and R. Seibt. 2022. “Gender-specific Aspects of Teachers Regarding Working Behavior and Early Retirement.” Frontiers in Psychology 13:829333. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2022.829333.

- Lee-Corbin, H. 2005. “Under the Microscope: A Study of Schools in Special Measures and a Comparison with General Characteristics of Primary School Improvement.” Education 3-13 33 (2): 51–57. https://doi.org/10.1080/03004270585200231.

- Matthews, C. 2023. “Pressure on Ofsted Mounts as Union Demands Full Inquiry Into Role Inspection Played in Suicide.” Daily Mail Online, March 22, 2023. https://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-11889409/Pressure-Ofsted-mounts-union-demands-inquiry-role-inspection-played-suicide.html.

- Matthews, P., and P. Sammons. 2005. “Survival of the Weakest: The Differential Improvement of Schools Causing Concern in England.” London Review of Education 3 (2): 159–176. https://doi.org/10.1080/14748460500163989.

- McGuinness, S. J. 2012. “Education Policy in Northern Ireland: A Review.” Italian Journal of Sociology of Education 4 (1): 205–237. https://ijse.padovauniversitypress.it/system/files/papers/2012_1_9_0.pdf.

- McNamara, G., and J. O’Hara. 2006. “Workable Compromise or Pointless Exercise?” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 34 (4): 564–582. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143206068218.

- Munoz-Chereau, B., and M. Ehren. 2021. Inspection Across the UK: How the Four Nations Intend to Contribute to School Improvement. London, UK: Edge Foundation. https://www.edge.co.uk/documents/139/Inspectionacross-the-UK-report-FINAL.pdf.

- OECD. 2013. Synergies for Better Learning: An International Perspective on Evaluation and Assessment. Paris: OECD Publishing. https://www.oecd.org/education/school/Evaluation_and_Assessment_Synthesis_Report.pdf.

- Parentkind. 2023. School Inspections Parent Poll – July 2023. London, UK: Parentkind. https://www.parentkind.org.uk/research-and-policy/parent-research/research-library/exams-and-assessment/school-inspections-parent-poll-july-2023.

- Penninckx, M. 2017. “Effects and Side Effects of School Inspections: A General Framework.” Studies in Educational Evaluation 52:1–11. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.stueduc.2016.06.006.

- Penninckx, M., and J. Vanhoof. 2015. “Insights Gained by Schools and Emotional Consequences of School Inspections. A Review of Evidence.” School Leadership & Management 35 (5): 477–501. https://doi.org/10.1080/13632434.2015.1107036.

- Penninckx, M., J. Vanhoof, S. De Maeyer, and P. Van Petegem. 2014. “Exploring and Explaining the Effects of Being Inspected.” Educational Studies 40 (4): 456–472. https://doi.org/10.1080/03055698.2014.930343.

- Penninckx, M., J. Vanhoof, S. De Maeyer, and P. Van Petegem. 2016a. “Effects and Side Effects of Flemish School Inspection.” Educational Management Administration & Leadership 44 (5): 728–744. https://doi.org/10.1177/1741143215570305.

- Penninckx, M., J. Vanhoof, S. De Maeyer, and P. Van Petegem. 2016b. “Explaining Effects and Side Effects of School Inspections: A Path Analysis.” School Effectiveness and School Improvement 27 (3): 333–347. https://doi.org/10.1080/09243453.2015.1085421.

- Perry, C. 2016. Research and Information Service Briefing Paper: Education System in Northern Ireland. Belfast, UK: Northern Ireland Assembly. http://www.niassembly.gov.uk/globalassets/documents/raise/publications/2016-2021/2016/education/4416.pdf.

- Perryman, J. 2007. “Inspection and Emotion.” Cambridge Journal of Education 37 (2): 173–190. https://doi.org/10.1080/03057640701372418.

- Perryman, J. 2022. Teacher Retention in an age of Performative Accountability: Target Culture and the Discourse of Disappointment. Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

- Quintelier, A., J. Vanhoof, and S. De Maeyer. 2018. “Understanding the Influence of Teachers’ Cognitive and Affective Responses upon School Inspection Feedback Acceptance.” Educational Assessment, Evaluation and Accountability 30 (4): 399–431. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11092-018-9286-4.

- Rawlinson, K. 2023. “Scrapping one-Word Gradings Won’t Solve Heads’ ‘Discomfort’, Says Ofsted Chief.” The Guardian, June 12, 2023. https://www.theguardian.com/education/2023/jun/12/scrapping-one-word-gradings-wont-solve-heads-discomfort-says-ofsted-chief.

- Rosenthal, L. 2004. “Do School Inspections Improve School Quality? Ofsted Inspections and School Examination Results in the UK.” Economics of Education Review 23 (2): 143–151. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0272-7757(03)00081-5.

- Waters, S., and M. McKee. 2023. “Ofsted: A Case of Official Negligence?” BMJ. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.p1147.

- Wisniewski, B., S. Röhl, and B. Fauth. 2022. “The Perception Problem: A Comparison of Teachers’ Self-Perceptions and Students’ Perceptions of Instructional Quality.” Learning Environments Research 25 (3): 775–802. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10984-021-09397-4.

- Woods, P., and B. Jeffrey. 1998. “Choosing Positions: Living the Contradictions of Ofsted.” British Journal of Sociology of Education 19 (4): 547–570. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569980190406.

APPENDIX 1

The following variables were collected in the questionnaire pertaining to the last inspection participants had experienced which was not impacted by teachers’ industrial action.

Gender. Female (1) or male (0).

Type of school (SchoolType). Selective school (1) or non-selective school (0).

SubjectsTaught. Main subjects taught (free response).

Position in school (PositionSchool). SLT member (1) or non-SLT member (0).

Inspection outcome of last inspection that was fully reported on (InspOutcome). Very negative (1), negative (2), neutral (3), positive (4), very positive (5).

Response to statement ‘The inspection was conducted in a highly professional, transparent manner and the outcome accurately reflected the school’s performance’ (PerceivedQual). Strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neither agree nor disagree (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5).

Response to statement ‘The principal and senior leadership team were supportive in helping to prepare staff for the inspection and to deal with its consequences’ (SLTSupport). Strongly disagree (1), disagree (2), neither agree nor disagree (3), agree (4), strongly agree (5).

Instrumental effects (InstrumEffect). These were measured as the mean score from a scale consisting of the following five items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree):

As a result of the inspection, the school changed aspects of its policies

As a result of the inspection, members of the school staff were motivated to change aspects of their professional practice

As a result of the inspection, certain issues were dealt with differently

The inspection resulted in concrete actions (or ideas for actions)

The inspection resulted in actions that were beneficial for pupils.

Effects on personal life (PersLifeEffect). These were measured as the mean score from a scale consisting of the following six items, rated on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = strongly disagree, 2 = disagree, 3 = neither agree nor disagree, 4 = agree, 5 = strongly agree):

At home, I worried about the inspection

The inspection negatively impacted my relationship with my family

Because of the inspection, I devoted less time to my hobbies

I postponed personal plans because of the inspection

I experienced sleepless nights because of the inspection

People outside the school told me I was more irritable during the inspection than I normally was.

Stress on a normal school day, i.e. without inspection (StressNorm). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale: None (1), minor (2), some (3), considerable (4), major (5).

Stress two weeks before inspection (StressBefore). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale: None (1), minor (2), some (3), considerable (4), major (5).

Stress during inspection (StressDuring). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale: None (1), minor (2), some (3), considerable (4), major (5).

Stress two weeks after inspection (StressAfter). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale: None (1), minor (2), some (3), considerable (4), major (5).

Anxiety on a normal school day, i.e. without inspection (AnxietyNorm). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale: None (1), minor (2), some (3), considerable (4), major (5).

Anxiety two weeks before inspection (AnxietyBefore). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale: None (1), minor (2), some (3), considerable (4), major (5).

Anxiety during inspection (AnxietyDuring). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale: None (1), minor (2), some (3), considerable (4), major (5).

Anxiety two weeks after inspection (AnxietyAfter). Rated on a 5-point Likert scale: None (1), minor (2), some (3), considerable (4), major (5).

There were no missing values for any of the above variables relating to any of the 102 respondents. However, the questionnaire also invited respondents to elaborate upon their perspectives on the effects of inspections on school improvement and their personal/emotional lives, and comments were captured in the following variables for those who responded to the relevant questions:

Perspectives on school improvement effects (PerspSchImp). Free response.

Perspectives on personal life/emotional effects (PerspPersEmot). Free response.