ABSTRACT

Previous research emphasizes the importance of well-being in old age and its association with positive mental and physical health at earlier stages of aging during midlife. Acceptance and Commitment Therapy has the potential to support positive aging processes. This study examines the feasibility and acceptability of a new unguided eHealth ACT module in a population from 40 years onwards. Data were collected at two measurement points in time (before and after completion of the ACT module). In total, 313 participants (range = 40–75 years; mean(SD) = 54 years (8.3); 76% female) had 8 weeks access to the ACT module and responded to the feasibility questionnaire, upon completion of the module. Logged data (time spent online per session and in total, number of attended sessions) was also analyzed. Of the respondents, 76% reported a completion rate of 75%–100%. On average, 3.5 h (SD = 6.4) per week were spent on the module and practicing the ACT skills. The mean evaluation of the module was 7.4 (SD = 1.2, range = 1–10). Approximately 80% of the participants rated each session as (very) good. Absence of guidance was marked as a limitation. The results indicate good feasibility and acceptance of this unguided eHealth module. This is a promising result as this is, to our knowledge, the first study applying an eHealth ACT module to the general population in the context of positive aging. The effectiveness results will be addressed in a future paper.

As the composition of the world population changes toward an aging population and a longer lifespan, more attention to the aging process and factors affecting the well-being of older adults is needed (Bar-Tur, Citation2021). The aging process has long been dominated by a biomedical viewpoint, seeing aging as inevitable decline on a physical and cognitive level (Bowling & Dieppe, Citation2005). In recent decades positive aging models have been introduced that view aging from a life course perspective, as a continuous process over the life cycle (Elder et al., Citation2003). Aging can be seen as a multidimensional process that is influenced by different contextual factors (Hughes & Touron, Citation2021). Several terms are used such as Successful aging (Baltes & Baltes, Citation1990), Healthy Aging (Bryant et al., Citation2001; World Health Assembly, Citation2020) and Positive Aging (Hill, Citation2011). All refer to aging as possibly experiencing functional decline but directing attention to maintaining functioning on different levels and maintaining well-being (Urtamo et al., Citation2019). Aging is therefore considered as (a) an interaction of biological, lifestyle and environmental factors that produce positive outcomes (Strawbridge et al., Citation2002) and (b) focused on maximizing gains and minimizing losses through the processes of selection, optimization and compensation (Baltes & Baltes, Citation1990). Positive aging includes maintaining a good level of well-being, despite the challenges and changes that occur in later life (Hill & Smith, Citation2015). According to Hill (Citation2011), positive aging forms an overarching framework of strategies to maintain well-being in old age. People who age in a positive manner can activate their coping strategies, are flexible in their thinking and behavior, make decisions that safeguard their well-being and have a positive outlook on their future even with the cognitive and physical declines associated with aging. An intervention model that is in line with the concepts of positive aging is Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT).

The core elements of Acceptance and Commitment Therapy (ACT, Hayes et al., Citation2006), a third wave cognitive behavioral therapy, show similarities with the strategies in Hill’s (Citation2011) resources model. Both suggest skills – such as flexibility of thoughts and behavior – that can mediate negative elements (of aging) and improve well-being. ACT aims to increase psychological flexibility, which can be described as the capacity to adapt to different situations in order to live a meaningful life according to one’s own values (Hayes et al., Citation2006). To establish psychological flexibility six core processes are addressed, namely: acceptance, defusion, self as context, contact with the present moment, values, and committed action (Hayes et al., Citation2006). ACT-based interventions pay more attention to the context of events and help individuals to be more flexible and accepting of experiences (Kishita et al., Citation2017). Given the age-related challenges, this may be particularly useful for middle-aged and older adults.

ACT can help with the acceptance of changes in health, life conditions (Dindo et al., Citation2017) and the experience of losses (Speedlin et al., Citation2016). Research shows that older adults are more prone to isolation as a result of bereavement, retirement, and losses of contact (Blazer, Citation2020) and prevalence of mental health problems is substantial (Benbow, Citation2009; Byers et al., Citation2010; World Health Organization, Citation2017). Certain life events can lead to loss of contact with one’s own core values (Hayes et al., Citation2012). ACT can contribute to the reconnection with personal values and focus on the remaining potential (Petkus & Whetherell, Citation2013). Furthermore, acceptance does not appear to rely on cognitive functions that decline with age (Shallcross et al., Citation2013).

Research on the effectiveness of ACT has seen immense growth in the last decade. For example, a recent review of meta-analyses including adults of all ages showed that ACT is effective for anxiety, depression, substance use, chronic pain, and transdiagnostic combinations of conditions (Gloster et al., Citation2020). Gradually, more attention is also being paid to older age groups (Plys et al., Citation2022). For instance, ACT has proven to be effective for chronic pain (Alonso-Fernandez et al., Citation2016), depressive symptoms (Kishita et al., Citation2017) and generalized anxiety disorder (Gould et al., Citation2021) in the older populations. However, there are few studies that combine the middle-aged and older age groups. Karlin et al. (Citation2013) found that ACT for depression was as effective for older veterans as for younger ones. Plys et al. (Citation2022) found an age difference in psychological flexibility with higher values in the older age group. Both their findings support the use of ACT to improve acceptance of aging and its inherent challenges.

In the context of aging, it is worthwhile to include the middle-aged. Midlife holds a central position in the life course and has many challenges and transitions (Lachman et al., Citation2015). When midlife is entered, around the age of 40, signs of physical and cognitive aging become more prominent. Perceived health and well-being in midlife often have a determining influence on the later years of life (Lachman et al., Citation2010; Sabia et al., Citation2012). Attention to well-being and aging processes in this period can therefore have a positive impact later on (Infurna, Citation2021).

Considering the potential of ACT to support positive aging processes, it seems worthwhile to explore ways to make techniques offered by ACT accessible to middle-aged and older populations.

eHealth ACT

In addition to regular ACT interventions, several online modules (eHealth) have been developed. In their transdiagnostic meta-analysis, Thompson et al. (Citation2021) found small significant and long-term effects of online ACT on anxiety, depression, quality of life and psychological flexibility. The effects were similar across populations with psychological symptoms, somatic conditions, and a non-clinical population. However, research on eHealth ACT interventions with middle-aged and older adults is very limited (Witlox et al., Citation2021). To the best of our knowledge there are no large-scale studies that have evaluated the effectiveness of, especially unguided, eHealth ACT interventions for middle-aged and older adults. In most studies, blended ACT interventions are used. For example, the study by Lappalainen et al. (Citation2021) of a supported online ACT intervention for family caregivers who are 60 years or older showed a significant reduction of depressive symptoms, a decrease of avoidant coping strategies and an increase of acceptance strategies and skills. Consequently, the psychological well-being of the participants was positively affected. Stenhoff et al. (Citation2020) concluded that online ACT interventions can promote well-being in clinical and non-clinical populations. However, research in non-clinical populations is mostly limited to students. This leaves a large, and growing, population of middle-aged and older adults unexplored. It is in this population that an online intervention can have added value. With the changing population structure, the number of people experiencing the challenges of aging and wanting to promote their well-being is growing (Gillanders & Laidlaw, Citation2014). Offering an online intervention can reduce pressure on regular help, improve access (Andersson & Titov, Citation2014) and give people ownership of their well-being, a basic notion of positive aging (Bar-Tur, Citation2021). Although the current generation of older adults is increasingly using technology and the internet in their daily activities, there are still barriers to optimal technology adoption (Czaja, Citation2019; Wilson et al., Citation2021). These include lack of knowledge and experience of use, absence of support, lack of trust in the provider and a design that does not take into account the distinctive characteristics of older people (Wilson et al., Citation2021). In addition, there are contextual factors, such as low income that may also have an impact (Czaja, Citation2019; Wilson et al., Citation2021). Consequently, online interventions may not reach those most in need (Tennant et al., Citation2015). In developing this online module, efforts were made to take these barriers into account, to the extent possible in an unguided intervention. The eHealth module was designed by one of the members of the research team, with a profession as clinical psychologist and ACT expert, and piloted by another research team member with expertise in developing interventions for middle-aged and older adults. The module is built as a stand-alone module aimed at a broad target group with the advantages of being easily accessible and flexible in use. The module is designed as a preventive ACT intervention by offering the opportunity to learn about the core processes of ACT and practice by applying various exercises in everyday life. An unguided intervention was chosen because of its low cost and broad applicability. The designers are aware that this may have an impact on the adherence, feasibility, and acceptability.

The research question of this study is: how feasible and acceptable is an unguided eHealth ACT module promoting psychological flexibility and well-being in the general population aged between 40 and 75 years. We expect that the feasibility and acceptability of our eHealth module will be scored as sufficient by the majority of the participants.

Method

Study design

This feasibility study is part of a larger longitudinal effectiveness study with a controlled design consisting of two groups (experimental and control) and three measurement points. The current study used the data collected from the experimental group at the first measurement (T1, after registration) and second measurement (T2, after having access to the eHealth ACT module for 8 weeks). The data collected at T1 was used for demographics and drop-out characteristics and data collected at T2 was used for the feasibility results.

Participants

Participants between 40 and 75 years old were recruited from the general population of the Netherlands between December 2018 and May 2021. Inclusion criteria were having access to either a computer, tablet, or smartphone and sufficient knowledge of the Dutch language. Anyone who received psychological treatment at the time of recruitment was excluded from participation.

Procedure

The study was approved by the ethics committee of Open Universiteit in July 2018 (U2018/02076/HVM) and followed the American Psychological Association Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct (American Psychological Association, Citation2010). Informed consent, of all participants included in the study, was obtained. Graduate students of Open Universiteit recruited participants from the general Dutch population through personal contact and social media using the snowball sampling method. Interested parties could request participation information by e-mail. Registration for the study was done by e-mail with indication of date of birth and telephone number. Personal data was stored on a secured server of Open Universiteit, separate from the collected data. For the data collection online surveys were used (Limesurvey, version 2.06, Citation2016).

eHealth ACT module

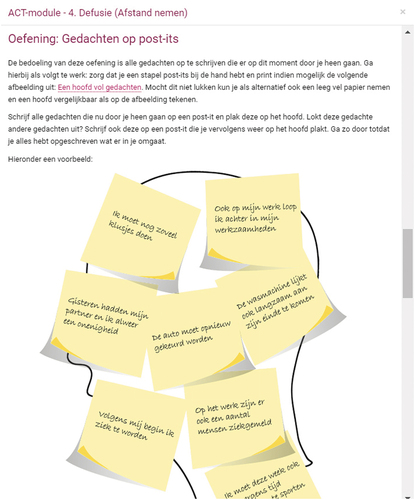

The eHealth ACT module was developed as a stand-alone module providing the basic ACT principles to the general population. The eHealth ACT module consisted of nine sessions to which participants had access during a period of 8 weeks. Each session began with an introductory video, by the ACT expert, explaining the ACT core process covered in that session. In addition, metaphors and different kinds of exercises were alternated to help participants gain knowledge about and experience with ACT. In the Appendix, five screenshots are included which show an example of an introductory video, illustrated metaphor, guided exercise, fill in exercise and practical exercise. Participants were advised to go through one session each week (with the exception of sessions one and two, which were covered in the same week) and to practice and repeat the content during that week. gives an overview of the sessions and their content. No therapeutic support, guidance, or feedback was provided. The module could be accessed through a website by using a laptop, tablet, or smartphone. The eHealth ACT module was made available by eHealth provider Embloom which is a software company specialized in eHealth applications. Embloom, one of the most used eHealth platforms in the Netherlands, collaborates with healthcare providers, patients, and universities.

Table 1. Overview of the nine sessions in the ACT module.

Measures

Demographic data

Demographic information, which was collected by means of self reports at T1, included gender, age, marital status, educational level, and professional situation.

Feasibility and acceptability data

The following self-reported measures were used to assess feasibility of the ACT module at T2: (a) indication of completion rate with four categories: between 0–25%, between 25–50%, between 50–75% and between 75–100%, (b) device used to access the eHealth ACT module (pc/laptop/tablet/smartphone) (c) experienced technical problems regarding the eHealth ACT module (open-ended question) and (d) describing a number of strengths and limitations of the eHealth ACT module (open-ended question).

Acceptability of the ACT module was measured in multiple ways, namely: (1) a self-report question addressing time per week dedicated to the online sessions and homework practice; (2) number of measures recorded by the eHealth provider, namely: (a) number of attended sessions. (b) time spent online per session; (c) time spent online on complete module; (3) satisfaction and evaluation through, respectively, an average grade for the module as a whole (range 0–10) and an optional grade for each session, ranging from very bad to very good; and (4) eight statements to evaluate the course content and their personal experience with the module, which needed to be answered on a 5-point Likert scale ranging from (1) ‘totally disagree’ to (5) ‘totally agree.’ The response to each statement separately was examined as indication for acceptability. gives an overview of the eight statements.

Table 2. Statements about the course content and self-evaluation.

Statistical analyses

Feasibility and acceptability measures were analyzed by using descriptive statistics. The variable time spent per session was recorded by the eHealth provider. As there were recorded login times for a very short amount of time and we wanted to calculate time spent actively engaging in a session, we decided to set a minimum criteria of 5 min per session and 45 min for the whole module. Therefore, login times of less than 5 min per session, and less than 45 min for the entire module, were not included in the analyses. Open-ended questions were analyzed by summing similar responses and ranking them from frequently mentioned to less frequently mentioned. Independent samples t tests were used to investigate differences between men and women and education level on the average grade, the completion rate, number of attended sessions, time spent online and the evaluation statements. Pearson’s correlation coefficients were calculated to investigate potential associations between age and the average grade, the completion rate, number of attended sessions, time spent online, and evaluation statements. For the completer – drop out comparisons, Chi-square tests were used for education level, marital status, and professional situation and (as the assumption for using the Chi-square test was violated) Cramer’s V was used for gender. Age was examined with an analysis of variance. All analyses were carried out with IBM SPSS statistics software, version 24 (IBM Corp, Citation2016). The significance level was set at α = .05.

Results

Participants characteristics

A total of 570 participants completed the first questionnaire and had access to the eHealth module. From these, 377 also completed the feasibility questionnaire at T2, but 64 of them stated that they had not opened the module. This corresponds with a drop-out rate of 45.1%. Therefore, the final sample for analyses consisted of 313 participants that both completed the baseline questionnaire at T1 and the feasibility questionnaire after having had access to the eHealth module for 8 weeks (T2). gives an overview of the demographic characteristics of the participants at baseline.

Table 3. Demographic characteristics of the participants at baseline.

Completion-dropout comparison

The results of the comparison between the completers (T1, T2, and module completed), semi-completers (T1 and T2 completed, module not completed) and dropouts (T2 and module not completed) are found in . There were no significant differences found between the groups for demographics at baseline.

Table 4. Comparison of demographics at baseline between completers, semi-completers, and dropouts.

Feasibility data

Of the final sample for analyses (n = 313), five respondents (2%) reported completing between 0% and 25% of the module, 16 (5%) between 25% and 50%, 53 (16.9%) between 50% and 75% and 238 (76%) stated that they completed 75% to 100% of the module. One respondent failed to report the completion rate of the module. Of all the participants 204 (65.2%) used a pc or laptop, 46 (14.7%) a tablet and 29 (9.3%) a smartphone. No technical problems were reported by 273 (87.2%) of the participants. Ten (3.2%) participants experienced problems with logging in, 10 (3.2%) other participants had problems playing audio or video. Four participants (1.3%) reported a technical problem, but did not specify it.

Participants were asked to report a number of strengths and limitations of the eHealth ACT module. See for an overview.

Table 5. Strengths and limitations of the eHealth ACT module.

Acceptability data

Participants reported spending on average 3.5 h (SD = 6.4; range time 0–50 h) per week working through the module and practicing the ACT skills in their daily life. Logged data from the platform provider was available for n = 281 participants. Of this group, 191 (68%) of the participants attended all nine sessions, 32 (11%) attended eight sessions and 25 (9%) attended five or less sessions. The average time online per session and the average total time online as recorded by the platform provider is shown in .

Table 6. Means and standard deviations time spent online on each session and in total (hh:mm:ss).

Satisfaction and evaluation

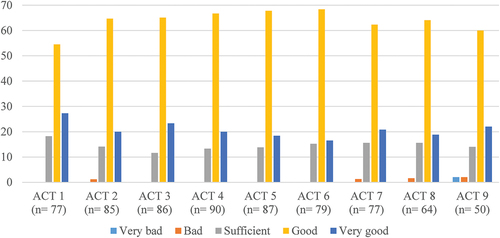

The module was graded with a mean evaluation of 7.4 (SD = 1.2) on a 10-point rating scale. Each session could also be rated separately, optionally, on the online platform. shows that the majority of the participants rated each session as good. A very small percentage of the participants rated sessions two (1.2%), seven (1.3%), eight (1.6%), and nine (2%) as bad. Session nine was the only session, which was rated very bad by 2% of the participants.

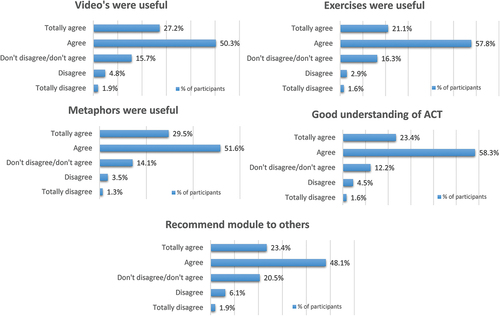

The vast majority of participants agreed with the eight statements about the usefulness of the content and self-evaluation. The results of each content statement can be found in The majority of participants found the videos (77.5%), exercises (78.9%), and metaphors (81.1%) useful. 81.7% of the respondents reported having a good understanding of what ACT is and 71.5% would recommend the module to others.

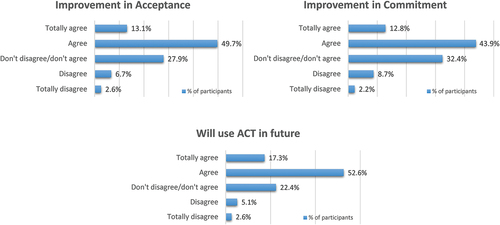

shows the results of the self-evaluation statements. Of the participants 62.8% found the course helpful in dealing with their thoughts and feelings and consequently experienced an improvement in their ability to accept their thoughts and feelings and 9.3% disagreed. For 56.7% of the participants the course was found to be helpful to invest more in things they find important and 10.9% disagreed. A total of 69.9% respondents indicated that they would continue to practice what they have learned and 7.7% disagreed.

Participants characteristics in relation to evaluations

Independent samples t tests showed no significant differences between men and women in the extent to which the course was completed and the evaluation of the module. There were also no significant differences between men and women with regard to the self-reported time spent in a week on the module and practicing the skills, nor did the number of attended sessions differ significantly between men and women. There were no significant differences between high and low educated participants in the percentage of completed lessons, time spent, evaluation grade, and number of attended sessions.

The results of the t tests on the logged time per lesson and the total time with gender and education level showed a significant difference between high- and low-educated participants in the online time spent on the third session (t (99.43) = −2.17, p < .05). On average, higher educated participants (M = 0:32:40; SD = 0:23:47) spent more time online completing the third session than lower educated participants (M = 0:27:02; SD = 0:12:59). Results related to the time spent on the other sessions showed no significant differences regarding gender and education. The results of the independent samples t tests showed no significant differences between men and women in the optional assessment of the lessons.

Regarding the statements on the content of the module and the self-evaluation a significant difference between men and women was observed in the intention to use ACT in the future (t (309)= −2.29, p < .02). On average, women (M = 3.84; SD =.86) reported a significant higher intention to use ACT in the future than men (M = 3.57; SD =.95). The results of the t tests showed no significant differences between high and low education level on the statements and self-evaluation.

No significant correlations were found between age and, respectively, the time that was spent on the module and the evaluation of the module. There was, however, a significant positive association between age and the self-reported percentage of completing the course (r = .18, p < .05). The correlation between age and the number of attended sessions was also significantly positive (r = .13, p < .05). No significant correlation was observed between age and the self-reported statements on content and self-evaluation. Positive significant correlations were found between age and the logged time for sessions two (r = .12, p ≤ .05), four (r = .20, p < .05), six (r = .18, p < .05), seven (r = .17, p < .05) and in total (r = .18, p < .05). Two significant negative associations were also found between age and the assessments of lessons eight (r = −.28, p < .05) and nine (r = −.31, p < .05).

Discussion and conclusion

The main objective of this study was to evaluate the feasibility and acceptability of a new eHealth ACT module to promote psychological flexibility and well-being in the general population between 40 and 75 years of age. With the increasing focus on a positive outlook toward aging and the role of well-being in this process, there is a growing need for interventions that can support aging processes from an early stage. Although middle-aged people face different challenges (e.g., combining multiple roles, caregiving) (Lachman et al., Citation2015) than older adults (e.g., functional decline, declining social network) (Blazer, Citation2020), an intervention for both of these groups is meaningful. After all, attention to well-being during middle age affects later life where maintaining well-being in turn is central (Infurna, Citation2021; Lachman et al., Citation2010; Sabia et al., Citation2012).

Principal findings

Feasibility

This study faced a drop-out rate of 45.1% between T1 and T2, which is not uncommon in eHealth studies (Melville et al., Citation2010). According to Eysenbach (Citation2005), high drop-out rates pose a fundamental difficulty in evaluating eHealth applications. Even though his paper was published a considerable time ago, the causal factors of drop-out he identified are still valid today and applicable to the current study. For example, the ease of enrollment by signing up by mail, the ease of discontinuing participation, and the lack of personal contact. Therefore, addressing these factors in follow-up research may result in lower drop-out rates.

Of the respondents, 76% reported 75% to 100% completion of the module. This completion rate gives an indication of the adherence to the intervention and is in line with the results of the meta-analysis by Thompson et al. (Citation2021). They found a range of completion rates in their meta-analysis of guided and unguided internet-based ACT interventions between 53.3% and 97.3%, with 75.8% as mean rate. In contrast, Kelders et al. (Citation2012) found an average of only 50% adherence to guided web interventions. Given that no guidance was provided for this intervention, adherence is considered to be good. It should be noted, however, that there is no standard measure of adherence, so comparisons with other studies should be made with some caution.

The majority of the participants used a PC or laptop to complete the module. The reported technical problems were limited. The login problems of some participants were solved by resetting their password or referring them to the user manual. The problems with playing the audio or video fragments were solved by switching to a different browser. No participants terminated their engagement due to technical problems. Thus, it can be concluded that the module was used as intended.

Regarding strengths and limitations, participants were most positive about the clear explanations of ACT processes, the acquisition of personal insights and the use of metaphors, exercises, and videos in the module. Also, the flexibility in using the module was often cited as a positive item. As limitations, participants reported the lack of personal guidance, feedback and interaction with a therapist and other participants as constraints, as well as the absence of reminders, the limited accessibility and no availability of a hardcopy. In order to optimize the module, these points should be considered to be adjusted in the future. In this study, an unguided online intervention was chosen because of its low cost and broad applicability. As mentioned in the introduction, older adults might experience some barriers to optimal technology adoption and absence of support is one of these barriers (Czaja, Citation2019; Wilson et al., Citation2021). Giving some form of guidance is thus an adjustment that can have added value. Other studies have shown that a guided online intervention leads to a higher compliance rate (Musiat et al., Citation2021), more user benefits (Andersson & Titov, Citation2014) and can potentially reduce dropout (Karyotaki et al., Citation2015). Other data suggest that guidance can positively influence the outcomes of ACT self-help interventions (French et al., Citation2017). However, there are many forms of guidance varying greatly in terms of intensity, degree of human involvement and the extent of automated processes (Musiat et al., Citation2021). Research has shown that even minimal guidance by e-mail can be effective in an online intervention (Fledderus et al., Citation2012). Some studies propose that the effect of guidance could be attributed to nonspecific factors that emerge in the interaction with users (Musiat et al., Citation2021). Therefore, the possibility of adding minimal guidance to the intervention may be interesting to explore.

The addition of more persuasive technology elements, for example tunneling, personalization and social support (Kelders et al., Citation2012) can also address the cited limitations and barriers. It may be worthwhile to investigate which methods fit within the intervention and contribute to the intended goal.

Taken into account all feasibility data, the findings indicate that the investigated eHealth ACT module can be considered a feasible eHealth intervention, corresponding with previous research suggesting that it is indeed feasible to offer an ACT intervention in an online format for the general population (Rickardsson et al., Citation2020).

Acceptability

User evaluations also showed good acceptability of the intervention. On average, participants reported working 3.5 h a week, both online and offline, on a session. The average time online, which was objectively recorded, fluctuated between 20 and 30 min per session. The combination of both data indicates that participants spend on average 3 h per week on practicing ACT skills in their daily lives, which demonstrates good acceptability. However, it should be noted that the estimate of self-reported time spent on an intervention is not necessarily accurate and is often overestimated (Wahbeh & Oken, Citation2012).

Participants rated the module with an average grade of 7.4. This is in line with the ratings of the individual sessions, which were all qualified as good by the majority of participants. The majority of the participants agreed with the positive statements on content evaluation. The videos, metaphors, and exercises were well received. Participants also claimed to have a better understanding of ACT. In addition, a large proportion of the participants would recommend the module to others. The results of the self-assessment statements also indicate good acceptability. The majority of participants reported an improvement in dealing with thoughts and feelings (Acceptance) and investing in the things that are important (Commitment). About 70% claimed to continue to practice ACT in the future, which suggests that what was learned was perceived as positive and useful.

The evaluation of the module in relation to the participant characteristics revealed that women had a higher intention of practicing ACT in the future than men. Studies on (online) self-help interventions often have a large proportion of highly educated women among their participants (Fledderus et al., Citation2012). Research has shown that women are more likely than men to seek help for mental health problems (Liddon et al., Citation2017). In addition, significant differences have been found between men and women in terms of the characteristics of the therapies they prefer. For example, men prefer group support and find it more difficult to engage in individual therapy (Liddon et al., Citation2017). It is therefore possible that women appear to be more willing to participate in self-help interventions and are more prepared to continue using what they have learned. Although some differences were found between lower and higher educated participants in time spent on one module, the conclusion can be drawn that the module was perceived equally acceptable.

The data indicated, however, the relevance of age. Older participants had a higher completion rate, opened more sessions, and spend more time online. Research has shown that younger adults tend to complete fewer sessions of a group intervention (Wetherell et al., Citation2016) and are faster than older adults in using web-based services (Rantakangas & Halonen, Citation2020). This may also be applicable to online interventions. It might be that older adults have a different attitude toward the intervention. They may have more time available and use this time to go through the sessions more thoroughly. Differences in computer skills between the age groups can also be a contributing factor (Gatto & Tak, Citation2008). The risk of physical illness is also higher in older age, eyesight of older participants may be impaired and motoric ability may be decreased (Rantakangas & Halonen, Citation2020). This can make it difficult to perform certain actions, such as handling a computer mouse. At the same time, older participants may face cognitive consequences of aging, such as reduced working memory capacity and attention span (Wildenbos et al., Citation2018).

It must be noted that the last two sessions were more negatively evaluated by older participants. These final sessions represent the culmination of the ACT process. Participants actively look at how they will invest, both in the short and long term, in the values that are important to them. A possible explanation for these negative evaluations can be found in the two-dimensional future time perspective. In their research, Strough et al. (Citation2016) found that middle-aged people focus on future opportunities rather than on the limited time that is left in life. Around the age of 60, however, this focus shifts and the emphasis comes to lie on the limited time perspective. If this perspective prevails among older participants, it is likely more difficult to address future actions related to their values. In addition, these sessions also require a decision-making strategy that appeals to fluid cognitive abilities, such as perceptual reasoning, that decrease with age (Opitz et al., Citation2014).

Critical remarks

Several critical comments can be made regarding this study. The data collection was mainly through self-reporting. This can lead to socially desirable answers (Paulhus, Citation1991) and overestimation of one’s own time investment (Wahbeh & Oken, Citation2012). In addition, there was an overrepresentation of women and highly educated people in our sample, raising problems in generalizing the results. Future research should include more male respondents and lower-educated individuals. However, as mentioned earlier, these interventions tend to attract more women than men, which is also an interesting fact to further explore in order to identify elements making the online ACT module more attractive or valuable to men. Furthermore, the age range of our sample was rather large, including participants in different stages of their lives. Research has shown that the outlook on life (Strough et al., Citation2016) or cognitive (Wildenbos et al., Citation2018) and physical functioning (Rantakangas & Halonen, Citation2020) of a 40-year old can be quite different from that of an older adult of 70 years, also depending on contextual factors like environment (Hughes & Touron, Citation2021). To maximize the use of an eHealth intervention, it should be tailored to the characteristics and abilities of the intended end user (Broens et al., Citation2007). With such a large and diverse target group, this is difficult to achieve. Lastly, because of the design of this study, using an eHealth module, only internet users with the availability of a computer, tablet, or smartphone could participate which limits the generalization of the results to solely internet users. Especially with increasing age, the percentage of non-internet users will increase. It is shown that in the age range of 45 to 65 only 1% of the Dutch people does not have access to the internet at home. In the age range of 65 to 75 this percentage is 6% of which the majority are low-educated (CBS, Citation2020). The inclusion of low educated individuals is therefore, one of the main challenges for future eHealth intervention studies.

Another important point to address is that the inclusion period of this study overlaps with the COVID-19 pandemic, which might had some impact on the participant involved in this study. Participants might have experienced higher levels of distress or lower well-being as research, done in the general Dutch population, showed that perceived stress levels increased during the pandemic (Slurink et al., Citation2022). A study performed in the UK showed an increase in levels of distress and also a positive association between psychological flexibility and well-being (Dawson & Golijani-Moghaddam, Citation2020) indicating that psychological flexibility might be an adaptive response style during challenging times as the pandemic.

Implications

The eHealth intervention investigated in this study was designed as a stand-alone module without any guidance. Our results show that the intervention is feasible and acceptable in a general population sample of adults aged between 40 and 75 years old who had access to the internet. Implicating that the intervention could be made available to middle-aged and older adults in other regions and countries, hereby taking into account that cultural background was not specifically addressed in this study. A stand-alone module has the advantages of being easily accessible, applicable to a broad group at very low costs and flexible in use. Besides this, the results on user characteristics like age and gender suggested that tailoring the intervention according to these characteristics might have some added value and make the intervention more personal and attractive. The user characteristics may also influence the need for guidance and support. Through tailoring, this can also be adjusted according to personal needs.

Conclusion

This study presented evidence that it is feasible to offer an unguided eHealth ACT module for middle-aged and older adults of the general population. In addition, the user evaluations showed a good acceptability of the studied eHealth ACT module, but also indicated that taking account of user characteristics can help to improve the attractiveness and value of these online modules for different target groups. The effectiveness of the intervention is comprehensively investigated in the longitudinal study, with an extra time point and will be reported in a future paper.

Acknowledgment

We are very grateful to Eduard de Vries, Saskia Monna, Caroline van Genk, Astrid Lippolt, Josien Metske, and Jasper Tilburg for contributing to the data collection for this study. We are also grateful to eHealth provider Embloom to make the eHealth ACT module available for research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

References

- Alonso-Fernandez, M., Lopez-Lopez, A., Losada, A., Gonzalez, J. L., & Loebach Wetherell, J. (2016). Acceptance and commitment therapy and selective optimization with compensation for institutionalized older people with chronic pain. Pain Medicine, 17, 264–277. https://doi.org/10.1111/pme.12885

- American Psychological Association. (2010, March). Ethical principles of psychologists and code of conduct. http://www.apa.org/ethics/code/index.aspx

- Andersson, G., & Titov, N. (2014). Advantages and limitations of internet-based interventions for common mental disorders. World Psychiatry, 13, 4–11. https://doi.org/10.1002/wps.20083

- Baltes, P. B., & Baltes, M. M. (1990). Psychological perspectives on successful aging: The model of selective optimization with compensation. In P. B. Baltes & M. M. Baltes (Eds.), Successful aging: Perspectives from the behavioral sciences (pp. 1–34). Cambridge University Press.

- Bar-Tur, L. (2021). Fostering well-being in the elderly: Translating theories on positive aging to practical approaches. Frontiers in Medicine, 8, 517226. https://doi.org/10.3389/fmed.2021.517226

- Benbow, S. M. (2009). Older people, mental health and learning. International Psychogeriatrics, 21(5), 799–804. https://doi.org/10.1017/S1041610209009053

- Blazer, D. (2020). Social isolation and loneliness in older adults: A mental health/public health challenge. JAMA Psychiatry, 77(10), 990–991. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1054

- Bowling, A., & Dieppe, P. (2005). What is successful ageing and who should define it? British Medical Journal, 331(7531), 1548–1551. https://doi.org/10.1136/bmj.331.7531.1548

- Broens, T. H. F., Huis in’t Veld, R. M. H. A., Vollenbroek-Hutten, M. M. R., Hermens, H. J., van Halteren, A. T., & Nieuwenhuis, L. J. M. (2007). Determinants of successful telemedicine implementations: A literature study. Journal of Telemedicine and Telecare, 13(6), 303–309. https://doi.org/10.1258/135763307781644951

- Bryant, L. L., Corbett, K. K., & Kutner, J. S. (2001). In their own words: A model of healthy aging. Social Science & Medical, 53(7), 927–941. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0277-9536(00)00392-0

- Byers, A. L., Yaffe, K., Covinsky, K. E., Friedman, M. B., & Bruce, M. L. (2010). High occurrence of mood and anxiety disorders among older adults: The national comorbidity survey replication. Archives of General Psychiatry, 67(5), 489–496. https://doi.org/10.1001/archgenpsychiatry.2010.35

- CBS. (2020, April 1). 453 duizend Nederlanders hadden in 2019 thuis geen internet [453 thousand Dutch people did not have internet at home in 2019]. https://www.cbs.nl/nl-nl/nieuws/2020/14/453-duizend-nederlanders-hadden-in-2019-thuis-geen-internet

- Czaja, S. J. (2019). Usability of technology for older adults: Where are we and where do we need to be. Journal of Usability Studies, 14(2), 61–64.

- Dawson, D. L., & Golijani-Moghaddam, N. (2020). COVID-19: Psychological flexibility, coping, mental health, and wellbeing in the UK during the pandemic. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 17, 126–134. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.07.010

- Dindo, L., Van Liew, J. R., & Arch, J. J. (2017). Acceptance and commitment Therapy: A transdiagnostic behavioral intervention for mental health and medical conditions. Neurotherapeutics, 14(3), 546–553. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-017-0521-3

- Elder, G. H., Jr., Johnson, M. K., & Crosnoe, R. (2003). The emergence and development of life course theory. In J. T. Mortimer & M. J. Shanahan (Eds.), Handbook of the life course (pp. 3–19). Kluwer Academic.

- Eysenbach, G. (2005). The law of attrition. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 7(1), e11. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.7.1.e11

- Fledderus, M., Bohlmeijer, E. T., Pieterse, M. E., & Schreurs, K. M. G. (2012). Acceptance and commitment therapy as guided self-help for psychological distress and positive mental health: A randomized controlled trial. Psychological Medicine, 42(3), 485–495. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291711001206

- French, K., Golijani-Moghaddam, N., & Schröder, T. (2017). What is the evidence for the efficacy of self-help acceptance and commitment therapy? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 6(4), 360–374. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2017.08.002

- Gatto, S. L., & Tak, S. H. (2008). Computer, internet, and e-mail use among older adults: Benefits and barriers. Educational Gerontology, 34(9), 800–811. https://doi.org/10.1080/03601270802243697

- Gillanders, D., & Laidlaw, K. (2014). ACT and CBT in older age: Towards a wise synthesis. In N. Pachana & K. Laidlaw (Eds.), The Oxford handbook of clinical geropsychology (pp. 637–657). Oxford University Press .

- Gloster, A. T., Walder, N., Levin, M., Twohig, M., & Karekla, M. (2020). The empirical status of acceptance and commitment therapy: A review of meta-analyses. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 181–192. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.09.009

- Gould, R. L., Wetherell, J.L, Kimona, K., Serfaty, M. A., Jones, R., Graham, C. D., Lawrence, V., Livingston, G., Wilkinson, P., Walters, K. and Le Novere, M. (2021). Acceptance and commitment therapy for late-life treatment-resistant generalised anxiety disorder: A feasibility study. Age and Ageing, 50(5), 1751–1761. https://doi.org/10.1093/ageing/afab059

- Hayes, S. C., Luoma, J. B., Bond, F. W., Masuda, A., & Lillis, J. (2006). Acceptance and commitment therapy: Model, processes and outcomes. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 44, 1–25. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.brat.2005.06.006

- Hayes, S. C., Strosahl, K. D., & Wilson, K. G. (2012). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy: The process and practice of mindful change (2nd ed.). Guilford Press.

- Hill, R. D. (2011). A positive aging framework for guiding geropsychology interventions. Behavior Therapy, 42, 66–77. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2010.04.006

- Hill, R. D., & Smith, D. J. (2015). Positive aging: At the crossroads of positive psychology and geriatric medicine. In P. A. Lichtenberg, B. T.Mast, B. D. Carpenter & J. Loebach Wetherell (Eds.), APA handbook of clinical geropsychology, vol. 1: History and status of the field and perspectives on aging (pp. 301–329). American Psychological Association.

- Hughes, M. L., & Touron, D. R. (2021). Aging in Context: Incorporating everyday experiences into the study of subjective age. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 12, 633234. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyt.2021.633234

- IBM Corp. (2016). IBM SPSS statistics for windows (Version 24.0) [Computer software].

- Infurna, F. J. (2021). Utilizing principles of life-span developmental psychology to study the complexities of resilience across the adult life span. The Gerontologist, 61(6), 807–818. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/gnab086

- Karlin, B. E., Walser, R. D., Yesavage, J., Zhang, A., Trockel, M., & Barr Taylor, C. (2013). Effectiveness of acceptance and commitment therapy for depression: Comparison among older and younger veterans. Aging & Mental Health, 17(5), 555–563. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2013.789002

- Karyotaki, E., Kleiboer, A., Smit, F., Turner, D. T., Pastor, A. M., Andersson, G., Berger, T., Botella, C., Breton, J. M., Carlbring, P., and Christensen, H. (2015). Predictors of treatment dropout in self-guided web-based interventions for depression: An ‘individual patient data’ meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 45(13), 2717–2726. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291715000665

- Kelders, S. M., Kok, R. N., Ossebaard, H. C., & Van Gemert-Pijnen, J. E. W. C. (2012). Persuasive system design does matter: A systematic review of adherence to web-based interventions. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 14(6), e152. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.2104

- Kishita, N., Takei, Y., & Stewart, I. (2017). A meta-analysis of third wave mindfulness-based cognitive behavioral therapies for older people. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 32(12), 1352–1361. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4621

- Lachman, M. E., Agrigoroaei, S., & Baune, B. T. (2010). Promoting functional health in midlife and old age: Long-term protective effects of control beliefs, social support, and physical exercise. PLoS One, 5(10), e13297. https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0013297

- Lachman, M. E., Teshale, S., & Agoroaei, S. (2015). Midlife as a pivotal period in the life course: Balancing growth and decline at the crossroads of youth and old age. International Journal of Behavioral Development, 39(1), 20–31. https://doi.org/10.1177/0165025414533223

- Lappalainen, P., Pakkala, I., Lappalainen, R., & Nikander, R. (2021). Supported web-based acceptance and commitment therapy for older family caregivers (CareACT) compared to usual care. Clinical gerontologist, 45(4), 939–955. Advance online publication. https://doi.org/10.1080/07317115.2021.1912239

- Liddon, L., Kingerlee, R., & Barry, J. A. (2017). Gender differences in preferences for psychological treatment, coping strategies, and triggers to help-seeking. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 57(1), 1–17. https://doi.org/10.1111/bjc.12147

- Limesurvey. (2016). Limesurvey (Version 2.06) [Computer software]. https://www.limesurvey.org/

- Melville, K. M., Casey, L. M., & Kavanagh, D. J. (2010). Dropout from internet-based treatment for psychological disorders. British Journal of Clinical Psychology, 49(4), 455–471. https://doi.org/10.1348/014466509X472138

- Musiat, P., Johnson, C., Atkinson, M., Wilksch, S., & Wade, T. (2021). Impact of guidance on intervention adherence in computerised interventions for mental health problems: A meta-analysis. Psychological Medicine, 52(2), 229–240. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0033291721004621

- Opitz, P. C., Lee, I. A., Gross, J. J., & Urry, H. L. (2014). Fluid cognitive ability is a resource for successful emotion regulation in older and younger adults. Frontiers in Psychology, 5, Article 609. https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2014.00609

- Paulhus, D. (1991). Measurement and control of response bias. In J. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (Eds.), Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (Vol. 1, pp. 17–59). Academic Press.

- Petkus, A. J., & Whetherell, J. L. (2013). Acceptance and Commitment Therapy with older adults: Rationale and considerations. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 20(1), 47–56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cbpra.2011.07.004

- Plys, E., Jacobs, M. L., Allen, R. S., & Arche, J. J. (2022). Psychological flexibility in older adulthood: A scoping review. Aging & Mental Health, 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1080/13607863.2022.2036948

- Rantakangas, K., Halonen, R. (2020). Special Needs of Elderly in Using Web-Based Services. In M. Cacace (Eds.), Communications in Computer and Information Science book series (Vol. 1270, pp. 50–60). Springer. https://org.ezproxy.elib.ub.unimaas.nl/10.1007/978-3-030-57847-3_3

- Rickardsson, J., Zetterqvist, V., Gentili, C., Andersson, E., Holmström, L., Lekander, M., Persson, M., Persson, J., Ljótsson, B., & Wicksell, R. K. (2020). Internet-delivered acceptance and commitment therapy (iACT) for chronic pain—feasibility and preliminary effects in clinical and self-referred patients. mHealth, 6, 27. https://doi.org/10.21037/mhealth.2020.02.02

- Sabia, S., Singh-Manoux, A., Hagger-Johnson, G., Cambois, E., Brunner, E. J., & Kivimaki, M. (2012). Influence of individual and combined healthy behaviours on successful aging. Canadian Medical Association Journal, 184(18), 1985–1992. https://doi.org/10.1503/cmaj.121080

- Shallcross, A. J., Ford, B. Q., Floerke, V. A., & Mauss, I. B. (2013). Getting better with age: The relationship between age, acceptance, and negative affect. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 104(4), 734–749. https://doi.org/10.1037/a0031180

- Slurink, I. A. L., Smaardijk, V. R., Kop, W. J., Kupper, N., Mols, F., Schoormans, D., & Soedamah-Muthu, S. S. (2022). Changes in perceived stress and lifestyle behaviors in response to the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands: An online survey study. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 19(7), 4375. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph19074375

- Speedlin, S., Milligan, K., Haberstroh, S., & Duffey, T. (2016). Using acceptance and commitment therapy to negotiate losses and life transitions. American Counseling Association. https://www.counseling.org/knowledge-center/vistas/by-year2/vistas-2016/docs/default-source/vistas/article_121cc024f16116603abcacff0000bee5e7

- Stenhoff, A., Steadman, L., Nevitt, S., Benson, L., & White, R. G. (2020). Acceptance and commitment therapy and subjective well-being: A systematic review and meta-analyses of randomised controlled trials in adults. Journal of Contextual Behavioral Science, 18, 256–272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jcbs.2020.08.008

- Strawbridge, W. J., Wallhagen, M. I., & Cohen, R. D. (2002). Successful aging and well-being: Self-rated compared with Rowe and Kahn. The Gerontologist, 42(6), 727–733. https://doi.org/10.1093/geront/42.6.727

- Strough, J., Bruine de Bruin, W., Parker, A. M., Lemaster, P., Pichayayothin, N., & Delaney, R. (2016). Hour glass half-full or half-empty? Future time perspective and preoccupation with negative events across the life span. Psychology of Aging, 31(6), 558–573. https://doi.org/10.1037/pag0000097

- Tennant, B., Stellefson, M., Dodd, V., Chaney, B., Chaney, D., Paige, S., & Alber, J. (2015). eHealth literacy and web 2.0 health information seeking behaviors among baby boomers and older adults. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(3), e70. https://doi.org/10.2196/jmir.3992

- Thompson, E. M., Destree, L., Albertella, L., & Fontenell, L. F. (2021). Internet-based acceptance and commitment Therapy: A transdiagnostic systematic review and meta-analysis for mental health outcomes. Behavior Therapy, 52(2), 492–507. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.beth.2020.07.002

- Urtamo, A., Jyväkorpi, S. K., & Strandberg, T. E. (2019). Definitions of successful ageing: A brief review of a multidimensional concept. Acta bio-medica : Atenei Parmensis, 90(N. 2), 359–363. https://doi.org/10.23750/abm.v90i2.8376

- Wahbeh, H., & Oken, B. (2012, May 15-18). Objective and subjective adherence in mindfulness meditation trials [Poster presentation]. International Research Congress on Integrative Medicine and Health, Portland, USA.

- Wetherell, J. L., Petkus, A. J., Alonso-Fernandez, M., Bower, E. S., Steiner, A. R. W., & Afari, N. (2016). Age moderates response to acceptance and commitment therapy vs. cognitive behavioral therapy for chronic pain. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 31(3), 302–308. https://doi.org/10.1002/gps.4330

- Wildenbos, G. A., Peute, L., & Jaspers, M. (2018). Aging barriers influencing mobile health usability for older adults: A literature based framework (MOLD-US). International Journal of Medical Informatics, 114, 66–75. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijmedinf.2018.03.012

- Wilson, J., Heinsch, M., Betts, D., Booth, D., & Kay Lambkin, F. (2021). Barriers and facilitators to the use of eHealth by older adults: A scoping review. BMC Public Health, 21(1), 1556. https://doi.org/10.1186/s12889-021-11623-w

- Witlox, M., Garnefski, N., Kraaij, V., de Waal, M. W. M., Smit, F., Bohlmeijer, E., & Spinhoven, P. (2021). Blended acceptance and commitment therapy versus face-to-face cognitive behavioral therapy for older adults with anxiety symptoms in primary care: Pragmatic single-blind cluster randomized trial. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 23(3), e24366. https://doi.org/10.2196/24366

- World Health Assembly. (2020). Decade of healthy ageing: The global strategy and action plan on ageing and health 2016-2020: Towards a world in which everyone can live a long and healthy life: Report by the Director-General. World Health Organization.

- World Health Organization. (2017, December12). Mental health of older adults. World Health Organization. https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/mental-health-of-older-adults