Abstract

This article opens with a critical review of a selection of transactional analysis (TA) theory on leadership to illustrate the richness of what is available. It then presents some views and experiences from a sample of senior leaders in order to explore any links between the two. Consideration is given to what constitutes leadership and how our understanding of it has shifted over time to engage those who are less familiar with the topic. The article concludes that Berne’s original thinking, embellished by later TA practitioners, is a valuable resource for leaders today. The goal of the article is to provoke curiosity across the TA community about how to raise awareness of TA more broadly in organizations.

Keywords:

There is a wealth of material on leadership written from both within and outside the transactional analysis (TA) community, the vast majority of which was produced by academics, educators, and consultants. This prompted me to undertake a case study based on interviews with a sample of senior leaders to ascertain their perspectives on leadership.

Leadership has a crucial impact on the day-to-day experiences of people within an organization as well as on how effectively, or not, an organization performs, operates, and interacts with the external environment. My interest lies in the extent to which TA theory and concepts are relevant to the issues that preoccupy leaders and to the challenges they face. TA appears to offer a valuable leadership tool kit. For one thing, it is a systemic approach, which means that it accounts for the whole organization, including the external context, as well as the dynamic interplay between key elements. Also, it can throw light onto what sits below the surface in organizational life. For example, it can enable a deeper understanding of human behavior, often by helping us see what we are observing in a different way.

The purpose of this article is to give a voice to the views and experiences of a sample of leaders to establish whether their preoccupations are mirrored in the TA field. It draws on several key theories of TA authors, starting with Berne and extending to Fanita English, Alan Jacobs, Rosa Krausz, Sari van Poelje, and Madeleine Laugeri.

A Critical Review of Leadership With Reference to TA

I understand leadership as a social process and a dynamic interaction between people directed toward achieving outcomes that one person cannot achieve alone. To do this optimally requires providing suitable organizational conditions and adapting appropriately to customer needs and the external environment. The ultimate leadership goal is to safeguard the survival of the organization. This social process is shaped by the intrapersonal world of the leader along with many external factors, such as aspects of the task, the organization’s structure, culture, and the external environment.

In his book, Leadership: A Critical Text, Simon Western (Citation2008) commented that “when asking what is leadership, the answer depends on what one is looking for, and from where one is looking” (p. 39). In other words, our understanding of leadership is influenced by our personal history, our experiences, and the prevailing wider society or culture. Western is an academic, consultant, author, and fellow in leadership, and he pointed to a historical shift in how leadership is understood and how this is shaped by significant events. For example, during the 19th and early 20th centuries, industrialization increased across much of the Western world, and, arguably, as a consequence, leadership was primarily understood as the engineer of efficient production. In this frame, leaders were the fount of all solutions, and little, if any, consideration was given to the social dynamic between leaders and followers. However, from the mid-20th century, in response to the rise of psychological theories following World War II (TA being one of them), leadership was seen to include providing psychological support and motivation. With this came the recognition of a link between performance and how people are treated in the workplace, which gave more power to the workforce.

A subsequent shift was triggered by the increasing complexity of the world we live in as evidenced by technological transformation, an increasing pace of change, an upswell in the number of international businesses, and the rise of globalization. By the early 2000s, the anachronism VUCA (Volatile, Uncertain, Complex, Ambiguity) became common to refer to the growing complexity of world dynamics. VUCA originated from the military during the Cold War. Complex systems interact in unexpected ways, thereby making leadership more challenging. This posed a challenge to the myth that leaders can, or even should, provide all the answers. This shift in thinking was perhaps stunted in the aftermath of the global financial crises of 2008–2009 as many organizations focused heavily on their numbers and cash flow in order to survive.

More recently, the COVID-19 pandemic catalyzed a further shift that is sometimes referred to by the anachronism BANI (Brittle, Anxious, Nonlinear, Incomprehensible). While VUCA emphasizes the need for adaptability and flexibility, BANI emphasizes the need for innovation and awareness of emerging trends. BANI, coined by Jamais Cascio, a US anthropologist and Fellow of the Institute for the Future, points to a leadership context in which organizations are vulnerable to catastrophe and pressurized by a sense of urgency triggered by anxiety; detailed, long-term planning no longer makes sense; and control is an illusion.

Alongside these shifts has been a growing appreciation of leadership as a social process or intersubjective experience and a recognition of the role of followership as an essential component of leadership. These recent shifts are reflected in contemporary TA literature. For example, the relational perspective is reflected in a definition given by Krausz (Citation1986): “Leadership is not an entity, but a way of relating to others” (p. 86) and as “the process of channeling energy toward results” (p. 87). Another example comes from van Poelje (Citation2023), who highlighted that the world is moving from an individual focus to a more systemic focus and that organizational transformation is becoming increasingly important.

Leadership has been a preoccupation in TA since Berne (Citation1963). For the most part, his thinking on leadership was woven around a description of the structure and dynamics of groups and organizations. Berne described three kinds of leadership (p. 105):

The responsible leader is the person who holds a role of leader in the organizational structure.

The effective leader makes key decisions and gets things done but may not hold the role formally.

The psychological leader is the most powerful in the “hearts and minds” of the members of the group.

In addition to theory on leadership per se, Berne (Citation1963) wrote about the components of an organization. He defined an organization as a social aggregation that has at least two classes of people, leadership and membership, as well as:

A major external boundary, which separates what sits outside the organization from what is inside, including separating members from nonmembers

A major internal boundary, which separates leaders from those who are not

At least four minor internal boundaries that separate different categories of members

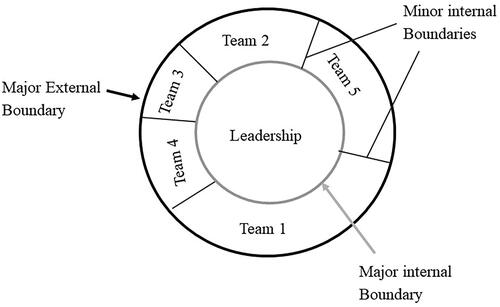

One implication of these criteria is that neither groups nor organizations exist without a leader. Berne defined an organization as having four or more internal boundaries, whereas groups have fewer (see , adapted from Berne, Citation1963, p. 58).

Figure 1. Organization Structure (adapted from Berne, Citation1963, p. 58).

Berne pinpointed where leaders need to pay particular attention by highlighting the significance of the external and internal boundaries. He explained that these elements, if managed too harshly, obtusely, or leniently, can have a significant impact on an organization. This concept translates well into our current, more complex environment. A case in point would be a newly formed business, in which the founders harden the external boundary by turning their back on the market and their customer base to focus on managing the detail and operational issues rather than delegate responsibility. In time, the market moves on, the product/service loses its appeal, money runs out, and key people leave because they have no freedom to act.

Berne (Citation1963) mapped the component parts of an organization using a lexicon and images that can facilitate dialogue and shared understanding. Further, by drawing on a systemic frame of reference, he described how organizations operate dynamically and noted that the interrelated components impact one another, which includes the people in the system. This insight seems highly relevant to leadership in a VUCA and/or a BANI world.

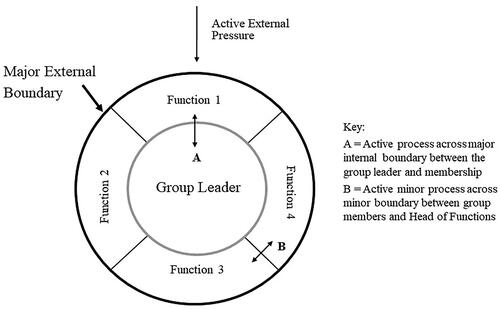

Post Berne, a number of transactional analysts from different fields and approaches have contributed to the body of theory on leadership. Some have reinvigorated TA’s psychoanalytic roots (such as Laugeri, Citation2006, Citation2020; van Beekum, Citation2006; and Korpiun, Citation2020, to name but a few). Other contributors have expanded Berne’s concepts, arguably making them more relevant to the current context. For example, in her article “Three Levels of Leadership,” van Poelje (Citation2022) described the task of leadership at the organizational, individual, and psychodynamic levels of an organization and highlighted the importance of the leadership role at the major and minor boundaries. Van Poelje also drew links with Berne’s (Citation1963) concept of the three kinds of leadership outlined earlier.

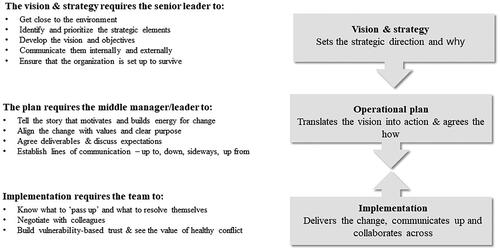

In “Emerging Change: A New Transactional Analysis Frame for Effective Dialogue at Work,” Laugeri (Citation2020) opened the possibility for more Adult-to-Adult dialogue (see ) as follows:

Figure 2. A Frame for Effective Dialogue at Work (adapted from Laugeri, Citation2006, p. 148).

The vision contract sits at the major external boundary to address external pressure by scanning and translating the needs of the environment into a strategy that is then “socialized” both internally and externally.

The mission contract, at the major internal boundary, addresses upward pressure through empowering members to come forward with their contribution and needs in a script-free way. When fit for purpose, only relevant information reaches the leader, and the task is performed well.

The cooperation contract, at the minor internal boundary, aims to address individual level frictions through encouraging relationship building and the growth of trust and confidence.

Laugeri (Citation2020) focused on contracting because it refers “not only to social interactions but also to the corresponding underlying unconscious processes” (p. 145). By contracting, leaders can invite involvement, autonomy, shared responsibility, collaboration, and power sharing. This frame is a systemic tool and a human process. It aligns an organization’s strategic activity with the strategic elements of its environment. This can result in structural cohesion that enables the organization to rapidly and efficiently meet external demands. It also creates the potential for meeting a range of human needs, for example, for rituals, structure, stimulus, and recognition. There are echoes of this framework in the leadership interviews conducted in my research described later in this article.

Kohlrieser, who has dedicated much of his life’s work to understanding what it means to be a hostage, contended that “across the spectrum of organizational life … people feel taken hostage by their work environments” (cited by Cornell, Citation2006, p. 3). He claimed that the role of leadership is to create security and cohesion by being a secure base for others so as to reduce fear, increase trust, and help employees bond or rebond to the organization. He contended that “high performance is built and maintained through bonding and building relationships” (p. 3). Kohlrieser suggested this requires skills in dialogue, empathy, and conflict management but, most significantly, self-awareness, because this enables leaders to bond with others and through this to provide a secure base.

An exploration of leadership is not complete without considering issues relating to power. This theme features in leadership literature and in the leadership conversations conducted for his article. For example, Western (Citation2008) commented that leadership “is everywhere, and understanding leadership in relation to power and authority is paramount” (p. 56). Kohlrieser (Citation2007) suggested that to use power effectively is to lead from within rather than lead from above and that this occurs where the quality of relationships enables leaders to exercise informal authority. He also pointed out that individuals do not need to feel powerless; “bonding is the antidote to the hostage dilemma” (p. 14).

In “Power and Leadership in Organizations,” Krausz (Citation1986) commented that “defining leadership in terms of power use expresses the intimate connection between the two concepts, which are different aspects of the same phenomenon” (p. 86). She observed that leaders influence the process of transforming inputs into outputs by means of four leadership styles, which differ depending on the source, nature, and force of the power used. The four styles are:

Coercive leadership, which relies on coercion and positional power

Controlling leadership, which relies on coercion, position, and reward

Coaching leadership, which is rooted in position, reward, knowledge, and support

Participative leadership, which makes use of reward, support, acknowledgment, and interpersonal competence

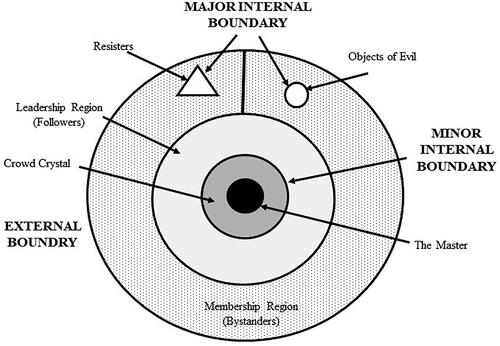

Although power is expressed and used by leaders in countless ways, many of them being positive, we know from history that some leaders veer toward a dark side of power. This is also explored in the TA literature, originating with Berne, who wrote a chapter entitled “Man as a Political Animal” in his Citation1947 book The Mind in Action. He described how leadership can be a negative force and how evil leaders build a followership by appealing to those who are “selfish and largely useless to society” (p. 297) and by turning the followers’ vulnerabilities to their own advantage. He commented that “life is complicated, and the evil leader holds his followers by making it simple” (p. 297). A review of Berne’s life suggests these ideas may have been borne out of events in Nazi Germany and being the subject of an investigation by the US Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI).

Some years later, Fanita English (Citation1979) addressed the destructive use of power in leadership in the talk she gave on receiving the Eric Berne Memorial Scientific Award for the concept of rackets as substitute feelings. She spoke in the wake of the Jonestown Tragedy during which over 900 people living in a community in Guyana took their lives by suicide. They were led by a temple leader whom they had followed from Indiana in the United States. The tragedy touched many people across the world. English’s talk appeared to draw on “Man as a Political Animal” as she described the abuse of power as a cocreation between leadership and followership. English suggested this occurs as a consequence of a human predisposition for people to fall into one of two types:

Type I, the “slave,” or those who adopt the “I’m not OK, You’re OK” position and who seek strokes from people who impress them

Type II, the “tyrant,” who takes the “I’m OK, You’re not OK” defensive position and who, in not trusting others, seeks to ensure their own security and comfort by imposing their reality on followers who will fall in line with this

Around 10 years later, Alan Jacobs (Citation1987) wrote on this subject in an article entitled “Autocratic Power,” in which he summarized the essence of English’s theory as follows:

English’s investigation focuses on this relationship between the person who leads and the ones who join and follow. Together they create a structure, a movement, which has as its major aim making the world over in its own image, primarily through accumulating power and, if necessary, using varying degrees of force. (p. 61)

Figure 3. Master-Follower Crowd Crystal System (adapted from Jacobs, Citation1991, p. 200).

Figure 4. A Dynamics Diagram (adapted from Berne, Citation1966, p. 152).

The theories on leadership touched on here span a period of over 40 years, which begs the question as to the extent to which these concepts are relevant to the experiences and perspectives of current leaders. I sought to test this out by gaining insight into what today’s leaders are actually paying attention to and how they are responding. My findings are described in the following sections.

The Gathering of Qualitative Data From Interviews

My research was inspired by the work of Popoola (Citation2021), which drew on conversations with a sample of men about their perspectives on the value women bring to the workplace. Popoola is a thought leader and facilitator working with individuals, teams, organizations, and leaders to develop a world in which human value is optimized.

Drawing inspiration from Popoola’s qualitative investigative approach, I undertook a group case study to gather the views of practicing leaders using a semi-structured interview approach. I learned this method many years ago while partnering with a marketing department to obtain customer insight to inform a rebranding and organizational transformation initiative. It resonates with my philosophical orientation by emphasizing the resources within the client or client system and allowing for the existence of multiple realities as well as acknowledging the inevitability of some degree of impact by the observer (or researcher) on what is being observed.

A consideration of what I set out to examine (i.e., ontology) alongside my preferred research methodology indicated a leaning toward constructivism and pragmatism, for which qualitative research methods are a suitable avenue of inquiry. To seek to prove, or disprove, a hypothesis using quantitative research would not have aligned with my philosophy, professional practice, or the research objective.

In practice, the semi-structured interviews fostered rapport and trust between me and the participants, thereby enabling them to share their personal experiences and perspectives more candidly. The use of open-ended questions produced in-depth and nuanced insights. This loose interview framework allowed me to adapt my questioning in line with their responses, thereby ensuring I explored unexpected avenues and obtained rich, context-specific data. Moreover, this methodology encouraged participants to express their thoughts, emotions, and narratives in their own words. Ultimately, the semi-structured interview methodology was instrumental in uncovering the depth and complexity of the subject matter in my study.

The dialogue was prompted by a set of questions that were used flexibly in response to the interest and energy of the interviewee, as just explained. The seven questions were:

How is leadership theorized and practiced in your organization?

What value does leadership bring to an organization?

How would you describe your leadership role?

How would you describe your leadership style?

What was the most useful piece of learning you have had about how to be a leader?

Do you foresee your leadership needing to change in the future?

Is there anything else you think is important to mention here?

Over 20 leaders were approached via an email entitled “A Series of Conversations on Leadership,” which outlined the purpose of the study, what was involved, what individuals would get from participating, and what to do next if they wanted to participate. Of the 20 people approached, 16 were willing to participate, keen to hear the findings, and able to give their time. All of the 16 interviewed held senior and challenging roles, ranging from chief operating officer (COO) to chief executive officer (CEO) and chair of a board of directors. The main criteria for selection were based on achieving as much diversity as possible within a small sample through differences in sector, organization size, and structure as well as geographical location. Some interviewees held leadership roles in the transactional analysis community, other sectors included the UK National Health Service (NHS), the UK Ministry of Defence (MOD), the arts, “Big Four” consultancy, food manufacturing, social housing, recruitment, healthcare solutions, and business education. The types of organization included charities, not-for-profit, and private and public sector and included regional, national, international, and globally based organizations. The furthest afield from my base in the UK was located in Australia. The size of organization ranged from around 100 employees to 1.4 million.

Some of the individuals interviewed gave evidence of their impact during the conversation. For example, the metrics of an organization led by one CEO interviewed included:

The first in the sector to be awarded the highest standard as an Investors in People (IIP), which is Platinum, and also the IIP Platinum UK employer of the year across all sectors in 2021. Their survey was based on a 90% response rate from staff and showed that 98% trusted the leadership and 98% felt trusted to do the job that they do.

The top customer service score in the institute of customer services index comprising 50,000 associations

Doubling of net profit in the last 10 years

The hospital led by an interviewee from the NHS was recognized in the following ways:

The best acute hospital in the country in the Dr. Foster Hospital Guide 2 years running

The health service journal’s best acute trust in the country

In the NHS continuing healthcare’s top 40 hospitals for 15 years

The best score in the country for Improving Working Lives (a Department of Health initiative)

Regarded as a flagship for change in innovation

Clinical teams won Royal College awards

The interviews took place between mid-January and late April 2023 and lasted around an hour. They began with contracting, particularly around confidentiality, anonymity, and an opportunity to refuse consent for their comments to be featured in this article before publication. The conversations were recorded and converted into transcripts. Each contained between 29 and 42 KB of data and averaged six pages of single-lined text. This was analyzed to identify the themes emerging from the interview, four of which were common across the sample: how leadership is understood and practiced, a commitment to learning and personal development, how power is understood and used, and what kind of leadership will be required in the future.

The Four Themes That Emerged Across the 16 Interviews

How Leadership Is Understood and Practiced

The strongest common theme across the interviews was the priority given to creating the conditions in which people can give their best, believing that this is the most effective driver of performance. References to this were frequent and various. Those with knowledge of TA expressed this accordingly: “I’m always trying to invite people into Adult and trying to create the space for them to allow their autonomy to really come forward.”

A leader from the social housing sector said, “I gave them resources and they have responded really well to that. We have a completely different feel in the team; people are now energized.” Another example was a leader from the NHS who said, “You’ve got to make it a fantastic place to work.”

Curiously, many of the examples interviewees gave of how they optimized the working environment were activities that attended to group process at either the major external, major internal, or minor internal boundaries (Berne Citation1963). In Principles of Group Treatment, Berne (Citation1966) accounted for why this is an important leadership function given that any energy invested in group process at these boundaries—for example, in conflict with the group leader or heads of other functions—is energy that is not invested in the group task. Examples included managing relationships with the board or external governance agencies, which sit at the major external boundary, and using questioning, empathy, and listening to surface issues at the major and minor internal boundaries (see ). One leader commented, “So part of the role of a senior leader in a public organization is to provide the heat shield to protect people from what goes on at the government level.”

All those interviewed referred to structural components of the organization, which suggested that these factors are on their radar. Some acknowledged that structure impacts performance. One CEO commented, “I reinstated values into our way of working, established direct lines of accountability between me and the senior clinicians, and the 13 of us sat round the management table. I believe in flat structures and devolution to enable people to get on with the job. For 2 years running we were Dr Foster’s best acute hospital in the country.” A leader from social housing commented, “The world is complex and you have no control over the external world, but I try to keep the organization strong by having guiding principles that allow people to do what they need to do without being fettered by policy.” Also mentioned were vision, mission, purpose, decision-making apparatus, values, roles and responsibilities, and communication structures.

All the leaders considered strategy formation as a key responsibility. One commented, “Strategy is my passion. I don’t think the senior team would deny that I am probably the main strategic person in the organization because I am out there. I gather information and I am curious.”

Communication was another recurring theme. Two leaders described how they used a systemic approach to communication. Both approaches mirrored some of the features presented by Laugeri (Citation2020). For example, a CEO from the public sector had a structure for communicating down the organization “to inspire extraordinary performance and give people hope in a challenging context.” Initiated at the top, the message was how the organization was moving forward in a compelling way. This was passed down and across the organization as each manager translated the story into a narrative for their team.

Another respondent, a CEO from social housing, described how their organization builds strategy “bottom up” with the involvement of staff and customers. This approach shared many features in common with the “Frame for Effective Dialogue” (Laugeri, Citation2020). This leader used “Open Space” methodology to facilitate dialogue and contracting at key junctures and to give everyone involved an opportunity to vote on the final draft. Open Space is a technique for running meetings for between 5 and 1000 people that enables participants to gain ownership of an issue and come up with solutions. The power of this approach was evidenced by a 99% “yes,” which gave the leaders a clear contract and mandate to proceed.

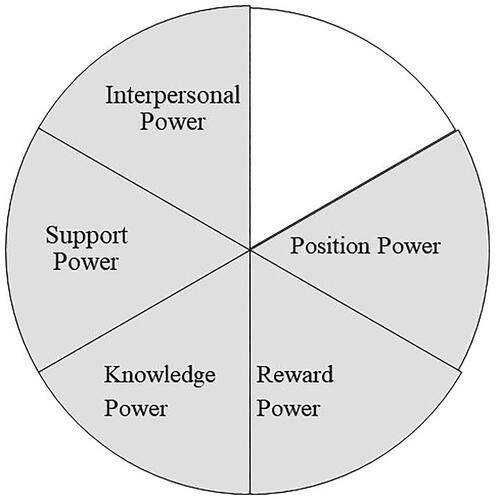

All those interviewed mentioned their commitment to meeting targets and customer expectations. Yet they spoke more of how they enabled others to deliver than of the actual targets. Their accounts of this seemed to suggest that the prevailing leadership style among those interviewed most closely aligned with a participative leadership style (Krausz, Citation1986) (see ). It also became apparent that by focusing on creating conditions in which others can deliver, effective leadership (Berne, Citation1963) flowed among the leader’s direct reports. One leader described this as establishing a contract between people who are trying to give their best and what the organization needed. Another leader described their role as a conductor orchestrating performance. These comments resonate with Laugeri (Citation2020), who suggested that contracting across organizational boundaries forms the basis of an OK-OK partnership. Kohlrieser might refer to this as providing coherence and a secure base.

Figure 5. Power Profile of a Participative Leadership Style (adapted from Krausz, Citation1986, p. 89).

Some of the comments made about leadership style suggest an awareness of psychological leadership (Berne, Citation1963), although many would not refer to it as such. References to this included seeking to create safety for people to think and behave as they wish, acting as a role model, leading from the front, being authentic, and working to clear and consistent values and ethics. One leader told of an experience they had had years earlier during the 2005 London bombings: “I remember a junior member of staff, a 21-year-old university student, saying to me, ‘I watched you walk across the office floor and you looked confident and fine and so I knew I was gonna be fine.’ I wasn’t confident. I wasn’t fine. I didn’t know how to deal with it, but the fact that that youngster had taken that away from the basics of body language gave her comfort in that moment of need.”

How Power Is Understood and Used

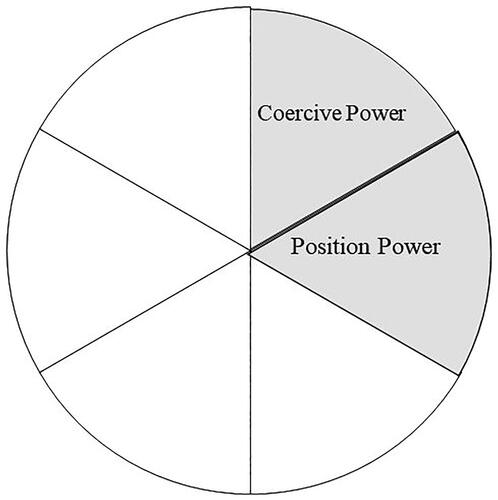

None of the leaders interviewed spoke of power in connection with positive leadership, and yet the majority spoke of the potential for harm resulting from a misuse of power, for example, being on the receiving end of power used negatively by a line manager earlier in their career. Ineffective leadership was associated with a top-down, hierarchical, or autocratic approach and particularly with a lack of listening, empathy, and integrity. This description resonates with a coercive style of leadership (see ).

Figure 6. Power Profile of a Coercive Leadership Style (adapted from Krausz, Citation1986, p. 89).

One leader commented, “I’ve inherited a couple of businesses where the previous management team led with that kind of command and control stance, and it created fear and insecurity; I think it is horribly toxic.” Another referred to the consequences of this style as “carnage”: “Carnage is when you’ve got high turnover, people out on stress leave, people who are very quiet, not participating, and are not keen to get involved because they don’t have the energy or they’re losing interest. While they are standing back, clients are complaining, and crappy work is being done.”

One participant related an incident featuring the abuse of power that echoes with the TA theory described earlier. Six months into a new managing director (MD) role, a supervisor informed her that their head of function (HOF) was abusive to staff. This HOF was a member of the site management team and had been in post for many years. The resulting investigation highlighted the use of power-wielding behaviors that included offensive language, name calling, and transmitting threats and violent images via email. This scenario resonates with aspects of Jacobs’s (Citation1987) theory in that the HOF led a campaign of fear and operated a crowd crystal around her focused on the MD (and the previous MD before her) as the “object of evil.” The MD described how the HOF perpetuated this scenario: “She had a small close circle of allies of vulnerable people, people who would be easily persuaded to follow a leader even if they knew that it wasn’t right because that would be more comfortable for them rather than setting their head up above the parapet. She was able to quite easily pick her allies, and so she felt protected.” The MD described how the HOF established followers: “Effectively she was their friend, and then she knew everything about them, and she had something on them, whether it was something work related or something domestically related, and she manipulated her power on that basis.” The HOF also manipulated power by misusing the group apparatus (Berne, Citation1963), for example, through rewards such as overtime and by dismissing staff without due regard to procedures.

The MD and I reflected on this case using TA to explore how this extreme behavior continued over a number of years, and, unsurprisingly, we concluded that the organization played a part. Some key factors were:

The organization operated in a price sensitive, highly competitive business-to-business sector delivering a product to a few players who had a near monopoly in the market.

The business was owned by private equity investors, and their influence led senior leaders to feel under extreme pressure to deliver “the numbers.” As a consequence, some senior leaders turned a blind eye to how the numbers were achieved.

Organizationally there was a pattern of not getting to the bottom of issues.

The HOF was not equipped for the role, which may have prompted a hunger for power to mask painful feelings of incompetence (English, Citation1979).

A Commitment to Continuous Learning and Development

All the leaders interviewed demonstrated a commitment to learning and personal development. Only one leader referred to programmatic leadership development per se, that is, group development that is typically designed and delivered by an external provider. A high value was placed on personal, even intrapersonal, development that is sourced individually. This resonates with the emphasis placed on intrapersonal leadership development by Kohlrieser (Citation2007) in his book Hostage at the Table.

One leader valued an internal 360 review process he had experienced earlier in his career. A 360 is a type of performance review that gathers feedback from those who report to, manage, and work alongside an individual and can include suppliers and customers. The goal is to measure an employee’s performance, highlight strengths, and earmark areas for development. Other respondents spoke appreciatively of one-to-one development accessed through coaching, psychotherapy, or supervision. Another commented: “The challenge that I have that is ongoing and lifelong is to unlearn a lot of what I learnt about leadership earlier in my career, such as the leader needs to have all the answers, the leader needs to be right, to trust more, and to see myself as a facilitator to compliment the fact that I don’t have all the answers.”

Many regarded their development as transformational, and high value was placed on the resulting ability to lead in their preferred style. One CEO commented, I had to learn about myself and how to work with power and how power lives with within me. High levels of trust inevitably lead to questions around power, so I had to examine my relationship to power.” Another took up a coaching course having recognized that a habit of offering solutions invited codependence, which resulted in her being overwhelmed. Other benefits mentioned included the potential of being able to “read what is going on” and “to spot patterns of behavior.” Such insights were experienced as a breakthrough in their leadership journey.

The Leadership Required in the Future

The majority of those interviewed expected the leadership context to become more complex. Reasons mentioned for this include changes in social, economic, and environmental factors. Several anticipated challenges arising from changing social expectations, the construction of hybrid work patterns, skill shortages, staff retention, AI (artificial intelligence), and meeting the needs of Generation Z.

The majority commented that a command and control leadership style would become even less relevant in the future. Some anticipated a need for increasing collaboration, both internally and externally, which requires more fluid organizational boundaries. One leader described it this way: “Where I see there needs to be more of an emphasis with leadership is an openness to working differently, an openness to collaboration, even with those who may have been viewed before as competitors.” This will require trusting teams more, because for some businesses remote working is only going to get bigger as well as skills around empathy, understanding, and listening, being able to work with different perspectives, and being open to learning.

A few pointed to future leadership having a wider reach, for example: “It’s not just about the business anymore. It’s about the business and our place on this planet, our place, our workforce, and our clients. And going forward, I think leaders who are successful are going to embrace more of that space rather than simply looking at people process and profit; they have to think differently.”

Conclusion

This article set out to consider the relevance of TA to those in leadership positions by means of a case study. Sixteen leaders were interviewed using a semi-structured approach to give them space to focus on what is important to them. Key themes were considered alongside some of Berne’s theories and more recent TA.

The findings suggest that leaders are focused on creating conditions that enable people to perform to their full potential as a means of enhancing organizational performance. It highlighted that enabling organizational performance in this way requires self-knowledge, strategic communication skills, systems understanding, and the ability to use power positively on the part of the leader. The findings from this article also indicate that individually inspired and sourced development resonates most strongly with leaders. TA has much to offer in these respects being a source of relevant theory and concepts, on the one hand, and a range of approaches to self-development, on the other. Further, it is envisaged that the relevance of TA will only increase as leadership gains broader acceptance as a relational and social phenomenon and as the leadership context increases in complexity.

Sixty years ago, more than 5 million copies of Games People Play (Berne, Citation1964) were sold, thereby making TA a worldwide phenomenon. To be so popular, it must have struck a chord with a broad spectrum of people at that time. However, many years later, this case study highlights that largely only leaders within the TA community recognize TA as a useful resource for the work they do. This mirrors my experience more generally. Therein lies a challenge that inspired this article, which is how can I raise awareness of what TA has to offer leaders so that they can draw on TA in relation to the challenges they face? I suspect that reestablishing widespread popularity for TA among those who do not have a clinical frame of reference will require a collaborative effort within the TA community and perhaps even a change in approach so that those in organizational roles can see the relevance more immediately. Leaders assimilate new theory and concepts most readily when the learning process begins with their experience and the content is relevant to their day-to-day experience. Therefore, I am curious to discover what it would take to enable more leaders to see the relevance of TA to the issues they face.

Disclosure Statement

The author declared no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship, and/or publication of this article.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Vanessa Williams

Vanessa Williams is a Certified Transactional Analyst (CTA) and Provisional Teaching and Supervising Transactional Analyst (PTSTA) in the organizational field with over 20 years of experience in consulting with groups and organizations. She teaches organizational TA at the Connexus Institute in Hove, United Kingdom, and offers supervision alongside working as a freelance consultant and associate consultant with Henley Business School and Roffey Park. Her areas of expertise include organization development (OD), leadership development, and practitioner development in the areas of OD, consultancy, facilitation, and coaching as well as soft skills training. Past roles include People Director and Head of OD. Vanessa can be reached at Hedges, Doomsday Gardens, Horsham, West Sussex, RH13 6LB, United Kingdom; email [email protected].

References

- Berne, E. (1947). The mind in action. Simon and Schuster.

- Berne, E. (1963). The structure and dynamics of organizations and groups: A transactional analysis handbook. Grove Press.

- Berne, E. (1964). Games people play: The psychology of human relationships. Grove Press.

- Berne, E. (1966). Principles of group treatment. Oxford University Press.

- Canetti, E. (1962). Crowds and power. Viking Press.

- Cornell, B. (2006). Facing conflict, finding common ground: Script editor Bill Cornell interviews former ITAA president George Kohlrieser. The Script, 36(4), 1–3.

- English, F. (1979). Talk by Fanita English on receiving the Eric Berne memorial scientific award for the concept of rackets as substitute feelings. Transactional Analysis Journal, 9(2), 90–97. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215377900900201

- Jacobs, A. (1987). Autocratic power. Transactional Analysis Journal, 17(3), 59–71. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215378701700303

- Jacobs, A. (1991). Autocracy: Groups, organizations, nations, and players. Transactional Analysis Journal, 21(4), 199–206. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215379102100402

- Kohlrieser, G. (2007). Hostage at the table: How leaders can overcome conflict, influence others, and raise performance. Jossey-Bass.

- Korpiun, M. (2020). Relational organizational development. Transactional Analysis Journal, 50(3), 207–220. https://doi.org/10.1080/03621537.2020.1771030

- Krausz, R. R. (1986). Power and leadership in organizations. Transactional Analysis Journal, 16(2), 85–94. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215378601600202

- Laugeri, M. (2006). Transactional analysis and the emerging change: The keys to hierarchical dialogue. In G. Mohr & T. Steinert (Eds.), Growth and change for organizations: Transactional analysis new developments 1995–2006 (pp. 37–395). International Transactional Analysis Association.

- Laugeri, M. (2020). Emerging change: A new transactional analysis frame for effective dialogue at work. Transactional Analysis Journal, 50(2), 143–159. https://doi.org/10.1080/03621537.2020.1726660

- Popoola, S. (2021). Male perspectives on the value of women at work. Mosaic Gold.

- van Beekum, S. (2006). The relational consultant. Transactional Analysis Journal, 36(4), 318–329. https://doi.org/10.1177/036215370603600406

- van Poelje, S. (2022). Three levels of leadership. In S. van Poelje & A. de Graaf (Eds.), New theory and practice of transactional analysis in organizations: On the edge (pp. 6–15). Routledge.

- van Poelje, S. (2023). Redefining the organizational field: The complexity of working with a quadruple focus. The Script, 53(6), 12.

- Western, S. (2008). Leadership: A critical text. Sage.