ABSTRACT

This article discusses the specific use of deictic verbs for encoding boundary-crossing situations in descriptions of non-actual motion, i.e. dynamic depictions of static spatial configurations (e.g. The road comes from the tunnel). We analyse data elicited with visual stimuli from speakers of Finnish and Estonian to show that venitive (‘come’) and andative (‘go’) deictic verbs tend to appear in boundary-crossing contexts of entering and exiting. This pattern applies to both actual and non-actual motion descriptions produced by the same speakers, thus showing pervasiveness in the expression of both concrete and abstract meanings. We suggest that this tendency can be interpreted in terms of functional deixis: motion (actual or non-actual) encoded in relation to the speaker’s visual and interactive circle of attention. Considering the relevance of spatial boundaries for event perception, boundary-crossing situations can be expected to show specific encoding patterns not only in the verb-framed languages, in which the expression of these situations typically requires the use of Path verbs, but also in the satellite-framed languages of the Talmian typology. Extensive variation between participants in our study indicates that in Finnish and Estonian, the use of deictic verbs in boundary-crossing situations is an optional strategy instead of a constraint.

1. Introduction

In descriptions of motion, it is essential to express crossings of different spatial boundaries, such as entering or exiting a room or crossing a road. This applies to actual, physical motion (e.g., She steps into the house or He crosses a bridge) as well as to non-actual motion (Blomberg and Zlatev Citation2014), i.e., descriptions of static configurations in terms of motion (e.g., A road goes out of the tunnel or A bridge crosses a ravine). Spatial boundaries are also important for visual perception: they function as cues in event segmentation, i.e., in how we divide the continuous perceptual flow (Baker and Levin Citation2015; Zacks Citation2020; Zacks and Tversky Citation2001). A cognitively central area of experience can be expected to affect language use.

Boundary-crossing (henceforth BC) situations seem to differentiate the language types of traditional motion typology (Talmy Citation2000b) more clearly than other types of motion: verb-framed languages typically express the Path of motion in the main verb, and especially need to do so when expressing BC (e.g., Aske Citation1989; Özçaliskan Citation2015; Slobin and Hoiting Citation1994). For example, in French, the sentence Une femme entre dans la salle ‘A woman enters the hall’ expresses BC but the sentence Une femme marche dans la salle is preferably interpreted as locative, i.e., ‘A woman walks in the hall’. In satellite-framed languages that typically express the Path of motion elsewhere in the sentence, for example in adverbs or adpositions, BC can generally be expressed with all types of motion verbs, including Manner verbs (as in English: A woman walks into the hall). The latter applies to the languages of our study, Finnish and Estonian, two closely related Uralic languages included in the satellite-framed type by Talmy (Citation2000b, 60).Footnote1

The discussion of BC has mainly concentrated on the dichotomy between Path and Manner. Nevertheless, recent results suggest that deictic motion verbs (e.g., come and go) may be a central resource in BC situations in at least some satellite-framed languages (e.g., Fagard et al. Citation2016; Taremaa Citation2017). However, deixis seems to be a relatively neglected aspect in research on motion descriptions (see Sarda and Fagard Citation2022). Tuuri and Belliard (Citation2021) show that in actual motion expressions in Finnish and Estonian, stimuli representing BC in the beginning or end of Path (Zlatev, Blomberg, and David Citation2010, see here Section 2.1), especially situations of entering or exiting the visual field of the observer, are often encoded with deictic verbs. The use of deictic verbs clearly centres on descriptions of BC stimuli (Tuuri and Belliard Citation2021, 281). We have connected these findings to the discovery by Matsumoto, Akita, and Takahashi (Citation2017) that venitive (‘come’) deictic verbs are often used to encode motion in relation to the speaker’s visual and interactive circle of attention, expressing rather functional than purely spatial meaning (i.e., coming into sight vs. coming towards the viewer). We suggest that in Finnish and Estonian, functional deixis is widespread and can be detected in the use of both venitive and andative (‘go’) deictic verbs.

If the use of deictic verbs as a resource in expressions of BC transfers from the expression of concrete, actual motion to more abstract use of motion verbs, this can be seen as evidence of the pervasiveness of this pattern (e.g., Barsalou Citation2008). Accordingly, we investigate the verbal expression of spatial deixis within the phenomenon of non-actual motion (henceforth NAM, see, Blomberg and Zlatev Citation2014), also called fictive motion (see Section 2.3), i.e., dynamic depictions of static situations, such as (1).

We explore the use of deictic motion verbs in NAM descriptions produced by Finnish and Estonian speakers to discover whether the tendency of expressing functional deixis transfers from AM to NAM and to examine the means of expressing BC in attested satellite-framed languages. We focus on the Finnish verbs mennä ‘go’ and tulla ‘come’ and the Estonian verbs minema ‘go, leave’ and tulema ‘come’.Footnote3 Along with this, we observe the use of other frequent NAM verbs to make sure the patterns found are specific to deictic verbs and not to the expression of NAM in general.

The data have been collected with an elicitation tool with drawings designed to invoke NAM expressions (Blomberg Citation2014). The elicited data allow systematic comparison between and within the two languages, and accordingly, we discuss variation between individual speakers in conjunction with cross-linguistic variation. Our analysis of AM data collected from the same participants with a video tool (Ishibashi, Kopecka, and Vuillermet Citation2006) functions as a background. Previous research on NAM expressions in our target languages is somewhat scarce and has mainly relied on corpus data (Karsikas Citation2004; Huumo Citation2009, Citation2013; Taremaa Citation2013).Footnote4

The research questions are the following: Does the connection between BC situations and the use of deictic verbs (attested for Finnish and Estonian by Tuuri and Belliard (Citation2021)) transfer from AM to NAM expressions, and if so, how should the connection be interpreted with respect to the meaning of these verbs? Does the use of deictic verbs show differences in encoding strategies between individual language users? What kind of similarities and differences arise in the use of deictic verbs between NAM and AM in Finnish and Estonian?

The article is structured as follows. In Section 2, we define the concept of BC and discuss it within the theoretical framework used in our analysis (Section 2.1), discuss deictic motion verbs in the context of motion typology (Section 2.2), and introduce NAM and its expression (Section 2.3). Section 3 presents our data and method. In Section 4, we lay the ground for the analysis of NAM by reporting results on the expression of spatial deixis in our AM data. Section 5 presents our results on the expression of spatial deixis in the NAM data and the role of BC in it. Section 6 summarizes and discusses the results.

2. Theoretical prerequisites

2.1. Boundary-crossing

A boundary-crossing situation includes either an exit from or an entrance into a bounded space or crossing a line or a plane (Özçaliskan Citation2015; Slobin and Hoiting Citation1994). According to Aske (Citation1989), verb-framed languages need to use Path verbs in telic Path expressions, but Slobin and Hoiting (Citation1994, 494–497) show that it is the crossing of spatial boundaries rather than only telicity (cf. Aske Citation1989) that constrains the use of Manner verbs. This is known as the BC constraint of verb-framed languages.Footnote5

BC situations can be understood as a subtype of bounded Path in the conceptual framework Holistic Spatial Semantics (henceforth HSS) used in the current article (e.g., Zlatev et al. Citation2021).Footnote6 Example (2) expresses BC in Path:mid and Path:end and (3) in Path:beg.

Example (4), on the other hand, expresses telic Path:end with a Landmark only reached and not entered, and example (5) expresses unbounded Direction.Footnote7

This article builds on the idea that even though satellite-framed languages typically impose no constraints on the verbal expressions of BC, this cognitively central area of expression may still employ linguistic resources in specific ways. As Taremaa (Citation2017, 288) states, “the fact that something is possible does not mean that it actually occurs”. Recent results suggest that in languages otherwise favouring the use of Manner verbs in motion descriptions, deictic verbs are a frequently used resource in expressions of BC (see Fagard et al. (Citation2016) for Swedish and German; Taremaa (Citation2017) for Estonian; Tuuri and Belliard (Citation2021) for Finnish and Estonian, see here Section 4). Our specific question is whether this tendency transfers from the expression of concrete actual motion to the more abstract non-actual motion.

2.2. Deictic verbs in motion descriptions

Spatial deixis, “having to do with the linguistic expression of the speaker’s perception of his position in three-dimensional space” (Fillmore Citation1971, 235), has been an object of vast interest in traditional research on spatial relations (Anderson and Keenan Citation1985; Denny Citation1978; Fillmore Citation1971). In the context of motion, spatial deixis basically consists of the notions “toward the speaker” and “in a direction other than toward the speaker” (Talmy Citation2000b, 56), but the use of deictic verbs covers complex situational variation within languages and especially across languages (see, Fillmore Citation1971, 269–288; Larjavaara Citation1990, 254–263 on Finnish; Pajusalu Citation2004 on Estonian).

However, as Sarda and Fagard (Citation2022, 6) point out, in the immense discussion on motion events, prompted by the typological models created by Talmy (Citation2000b), the diversity of motion expressions is often reduced to a dichotomy between Path and Manner. The empirical neglect in the literature is reinforced by conceptual diversity: spatial deictic verbs have either been placed under the notion of Path or separated from it (e.g., Morita Citation2022). They have been treated at least as Path verbs (Talmy Citation2000b), neutral or generic verbs (Özçaliskan Citation2015; Slobin Citation2006), or Direction verbs (Blomberg Citation2014; Fagard et al. Citation2016).

According to Talmy (Citation2000b, 138, endnote 19): “The Deictic is thus just a special choice of Vector, Conformation, and Ground, not a semantically distinct factor, but its recurrence across languages earns it structural status”. Nevertheless, languages often employ distinct coding patterns for deixis. For example, deictic verbs are often available and widely used in languages not commonly using Path verbs, which allows the expression of deixis in the main verb and the expression of non-deictic Path in other positions (Matsumoto, Akita, and Takahashi Citation2017, 95, 119). In general, Talmy’s notion of Path has been criticized for being too wide in its scope (Zlatev, Blomberg, and David Citation2010). Thus, we separate the expression of spatial deixis from Path.

Previous research motivates discussion of deictic elements in the typology of motion encoding. For example, Morita (Citation2022) shows that in Japanese, deictic verbs are the standard option for encoding a test setting with motion towards or away from the speaker, whereas in French, the use of deictic verbs is restricted, and deixis is rather expressed in adpositional phrases, if at all. Furthermore, Naidu et al. (Citation2022, 214) report on the importance of deictic verbs in Telugu, and Verkerk (Citation2013, 178) found that in a parallel corpus of data on 20 Indo-European languages, Armenian, Persian, Hindi, Nepali, and Irish tended to use deictic verbs rather than typical satellite-framed or verb-framed constructions. We discuss the role of deictic verbs in two alleged satellite-framed languages, expanding the discussion from actual to non-actual motion.

2.3. Non-actual motion

Non-actual motion expressions describe static spatial configurations in terms of motion, as in examples (1–5) above. The phenomenon is known by various terms, such as fictive motion (Talmy Citation2000a), subjective motion (Langacker Citation1987; Matsumoto Citation1996), and abstract motion (Matlock Citation2010), but it should be noted that these terms differ in their scope (see Blomberg Citation2014, 154–155). According to Blomberg and Zlatev (Citation2014, 397), NAM (expression) is “a cover term for all sentences in which (minimally) a motion verb is used to denote a situation that lacks observed motion”.Footnote8 We use this term because it does not in itself refer to any explanation of the expression type.

Researchers have presented different hypotheses on the motivation behind NAM, but they agree on a strong cognitive basis for the phenomenon (Langacker Citation1987; Matlock Citation2010; Matsumoto Citation1996; Talmy Citation2000a). Blomberg and Zlatev (Citation2014) propose that NAM is a non-unitary phenomenon based on a combination of at least three different cognitive motivations, emphasized in different situations: (1) enactive perceptionFootnote9 related to objects affording motion (i.e., entities which can be used for travelling, such as roads), (2) visual scanning along spatially extended objects, and (3) the imagination of movement. Along with the cognitive motivations, the expression of NAM is shaped by language-specific semantic constraints, which provides a reason to explore NAM cross-linguistically (Blomberg Citation2015; Blomberg and Zlatev Citation2014; Matsumoto Citation1996; Stosic et al. Citation2015).

The verb selection used in NAM descriptions tends to be more limited than in AM descriptions. NAM is typically expressed with a small set of semantically generic verbs (Blomberg Citation2015; Matsumoto Citation1996). Matsumoto (Citation1996) formulates this restrictedness as consisting of two conditions. First, according to the path condition (Matsumoto Citation1996, 194), NAM sentences require “some property of the path of motion” (or, as in the current framework, some specification of Path or Direction) to be expressed either in the verb or elsewhere in the sentence. Second, according to the manner condition, “no property of the manner of motion can be expressed unless it is used to represent some correlated property of the path” (Matsumoto Citation1996, 194). Accordingly, the deictic verbs appear as potential verbs for NAM expressions, while we expect to find few instances of Manner verbs in the data.

To our knowledge, little attention has been paid to the encoding of spatial deixis in the context of NAM (see, however, Waliński Citation2018, 168–172). Deictic verbs can be considered somewhat generic and thus typical for the expression of NAM, but it is important to notice that their directional opposition is retained in NAM expressions. This can be illustrated with Matsumoto’s (Citation1996, 186) English examples: the acceptability of the sentences They’re on the road that comes into the farm and They’re on the road that goes into the farm depends on the locations of speaker and/or hearer. Besides verbs, other elements such as adverbs, adpositions, and case markers participate in the expression of spatial relations in NAM, as in the expression of AM, but our focus is on verbs.

3. Method and data

3.1. Elicitation tools

The NAM data were collected with the elicitation tool introduced in Blomberg’s (Citation2014, Citation2015) research on NAM in Swedish, French, and Thai. The tool consists of 24 drawn target pictures aimed at eliciting NAM constructions and testing the limits of the phenomenon. In addition, the tool includes 12 fillers and two practice pictures. The pictures include a static figure and a landmark in a natural setting. In the target pictures, the figures are spatially extended linear objects, such as bridges and roads, because NAM expression has been specifically connected to these kinds of objects (see, Talmy Citation1983, 236).

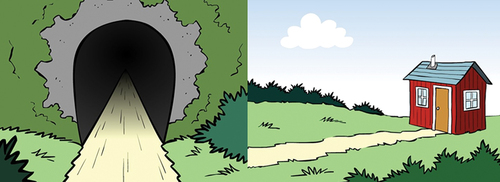

Even though static pictures cannot display actual, dynamic BCs (e.g., entrances into or exits from bounded spaces), the possibility of BC is a variable that can be examined in the NAM stimuli, and it is relevant in most of the target stimuli, as we explain in Section 5.3. These stimuli include pictures likely and less likely to evoke BC constructions in Path:beg or Path:end (e.g., the trail extending inside a tunnel vs. the trail ending by the house in ). BC can thus be used as a variable in analysing both the pictures and the descriptions.

Figure 1. Examples of the stimuli for collecting NAM expressions (Blomberg Citation2014). The example pictures vary with respect to the possibility to evoke BC expressions (yes vs. no) and the perspective (1pp vs. 3pp).

The NAM stimuli also vary systematically with respect to two variables hypothesised as influencing the probability of a NAM description, based on the motivations suggested for NAM (see Section 2.3). First, half of the stimuli are presented from a first-person perspective (henceforth 1pp, e.g., a path opening in front of the speaker), half portray the same configurations from a third-person perspective (henceforth 3pp, e.g., a path portrayed further away and from the side) (see ), thus corresponding to the experiential difference between lived and observed motion (see Blomberg Citation2014, 7–9, 174–175).Footnote10 Second, the figures differ in their affordance for motion. Half of the stimuli include figures easily imaginable as routes for translocation (e.g., roads, bridges), and the other half include figures less suitable as pathways (e.g., fences, phone wires) (Blomberg Citation2014, 174–177).

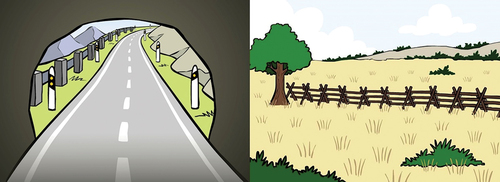

The AM data used for comparison have been collected with the elicitation tool Trajectoire (Ishibashi, Kopecka, and Vuillermet Citation2006; see also Tuuri Citation2021, Citation2023; Tuuri and Belliard Citation2021). This tool consists of 76 short videos (see ), 55 of which depict acted human translocation along different trajectories (e.g., exiting, descending) either including a BC situation or not (e.g., entering a landmark vs. moving towards a landmark), and with different manners of motion (e.g., walking, jumping) (see Vuillermet and Kopecka (Citation2019) for a detailed description). The videos have been filmed from different camera angles, portraying the moving figure either from the front or from the back (cf. 1pp in NAM) or from the side (cf. 3pp in NAM). The tool also includes 19 fillers and two practice videos.

Figure 2. Screenshots from the Trajectoire videos (Ishibashi, Kopecka, and Vuillermet Citation2006).

There are similarities in the spatial arrangements between the two elicitation tools. For example, both depict similar types of landmarks, such as caves or tunnels, roads, and bridges. At the same time, the tools differ in many respects (e.g., the number of stimuli, the media of representation), which should be kept in mind while comparing the results. The variables discussed in the article are listed in .

Table 1. The variables discussed in this article.

3.2. Data collection and participants

In the data collection sessions, the two tools were shown to the same participants, first the videos and then the picture tool.Footnote11 Three randomised orders of the stimuli were used in both tasks. Participants were asked to describe in approximately one sentence what they saw in each stimulus. In the AM task, the participants were advised to start describing after each video ended, when the screen turned blank. In the NAM task, the participants were allowed to start describing at the onset of a new picture. The transitions were manually controlled by the researchers, and instructions were given either in Finnish or in Estonian.

The data include descriptions from 50 Finnish speakers (age range 20–58, median 26, mean 29.4), and 25 Estonian speakers (age varying between ranges from 18–27 to 68–77, with most participants in the group 38–47)Footnote12 with different educational and occupational backgrounds. The participants were contacted through social media and university mailing lists. The Finnish data were collected in 2013–2015, the Estonian data in 2019–2020. The data collection sessions were mainly arranged face-to-face, but due to the travel restrictions during the COVID-19 pandemic, sessions with eight of the Estonian participants were conducted as video meetings. All participants signed an informed consent form.Footnote13

The sessions were video-recorded, transcribed (leaving out only noises and interruptions), and annotated in ELAN (Sloetjes and Wittenburg Citation2008). All the data were coded manually, but for the Estonian data, a transcription tool (Alumäe, Tilk, and Asadullah Citation2018) was also applied in the transcription phase. The data were analysed morphologically and semantically registering categories assumed by the HSS framework (Figure, Landmark, Motion, Frames of Reference, Region, Path, Direction, and Manner; along with more specific values for these). The Finnish AM data (descriptions of the 55 target videos) consist of 2,740 descriptionsFootnote14 (16,889 word tokens), and the Estonian AM data of 1,375 descriptions (11,977 word tokens). The Finnish NAM data (descriptions of the 24 target pictures) consist of 1,200 descriptions (12,569 word tokens), and the Estonian NAM data of 600 descriptions (5,767 word tokens).

4. Deictic resources in expressions of AM: a model for NAM

Based on the grounded theory of meaning (e.g., Barsalou Citation2008), the concrete AM expressions presumably function as models for the NAM expressions. Hence, as background, we report results on our AM data (Tuuri and Belliard Citation2021), concentrating on the aspects relevant for NAM. In both Finnish and Estonian, deictic verbs (mennä ‘go’ and tulla ‘come’ in Finnish; minema ‘go, leave’ and tulema ‘come’ in Estonian) were the main deictic resource in AM.Footnote15 Generally, andative (i.e., away from the deictic center) verbs tend to be less deictic than venitive (i.e., towards the deictic center) verbs, as they can be used as generic motion verbs alongside the meaning of moving away from the deictic center.Footnote16

Finnish and Estonian are closely related but differ, for example, with respect to the means of their andative verbs. In Finnish, mennä ‘go’ and lähteä ‘leave’ have remained as separate verbs: while mennä is typically connected to the expression of the goal, lähteä focuses on the starting point. In current Estonian, the two historically separate verbs have merged in a suppletive paradigm. The stems min- or mine- are found in infinitive forms (e.g., minema), participles and passive finite forms, while the stems lä(h)- or lähe- are used in active finite forms (Pällin and Kaivapalu Citation2012, 289–290; see also Pällin and Kaivapalu Citation2013). Thus, while Finnish mennä ‘go’ has the 1sg present active form mene-n, Estonian minema ‘go, leave’ has the 1sg present active form lähe-n. In our AM data, this difference in verb semantics explained some of the differences between the languages, but not all.

Overall, the Estonian participants used deictic and especially andative verbs in a wider range of contexts than the Finnish participants: 82% of the occurrences of Finnish mennä (n = 127) were in expressions of Path:end (e.g., into a cave). In comparison, only 41% of the occurrences of Estonian minema (n = 227) appeared in expressions of Path:end, and the other occurrences were scattered to different contexts, such as Path:mid and Path:beg.Footnote17 This means that minema was used rather generically, instead of clearly focusing on goal-directed Path:end expressions. In general, the Estonian participants opted for generic motion verbs with satellite-like particles specifying Path, while the Finnish participants typically included more information in the verb (Tuuri and Belliard Citation2021, 286–288). The general focus on BC (in one or more phases of Path) was, however, rather clear in the case of andative verbs: 86% of the occurrences of Finnish mennä and 78% of the occurrences of Estonian minema were in BC expressions.Footnote18 The use of the venitive verbs Finnish tulla and Estonian tulema clustered in the expression of Path:beg in both languages, but even more in Finnish (89%, n = 284) than in Estonian (74%, n = 245).Footnote19 These figures are close to the general results on BC: 94% of the occurrences of Finnish tulla and 76% of the occurrences of Estonian tulema were in BC expressions (in one or more phases of Path).

A central finding from the AM data was that in descriptions with BC in Path:beg (e.g., walk out of a cave; n = 352 in Finnish, n = 176 in Estonian), deictic verbs were the most used verbal category (as opposed to ‘Manner’, ‘Path’, ‘Direction:other’,Footnote20 ‘generic’, and ‘other’) in both Finnish and Estonian (see Tuuri and Belliard Citation2021). In Finnish, deictic (mainly venitive) verbs were used in 51% of the descriptions of Path:beg, while in Estonian, in 63% (see (6) encoding BC with the elative case).Footnote21 The number of different motion verbs used in expressions of BC in Path:beg was 21 in Finnish and 18 in Estonian.

In the descriptions of BC in Path:end (e.g., walk into a cave, n = 420 in Finnish, n = 187 in Estonian), Manner verbs were the most typical option, but the deictic verbs were the second most used verbal category (17% in Finnish, 35% in Estonian). The number of different motion verbs used in the expressions of BC in Path:end was 24 in Finnish and 17 in Estonian. In our data, the extensive use of deictic verbs is specific to the context of BC in Path:beg and Path:end. For example, in Finnish expressions of Path:mid (e.g., walk across the lawn, n = 589) and unbounded Direction (e.g., walk towards a tree, n = 419), the proportion of deictic verbs was only 1.4% and 0.5% of the descriptions, respectively (Tuuri Citation2021, 127, 136).

Considering traditional definitions of deictic motion verbs as expressing motion away from or towards the speaker, one might assume that in the AM data deictic verbs would be used for 1pp videos (filmed from behind or from in front of the moving figure, thus expressing the direction of the figure in relation to the viewer) and not so much for 3pp videos (filmed from the side). However, deictic verbs were used for both 1pp and 3pp in both languages, and in Finnish, 3pp was even more common for both tulla ‘come’ and mennä ‘go’ than 1pp. For example, for the 3pp video (028) of a boy stepping out of a cave on the beach, 38/50 of the Finnish participants used tulla (21/25 used tulema in Estonian). In contrast, the 1pp video (067) of a boy walking on the beach was not once described with the verb tulla but typically with Manner verbs accompanied with other directional expressions, such as kameraa kohti ‘towards the camera’ (2/25 used tulema in Estonian).

In both languages, there was a clear connection between BC and the use of deictic verbs. This connection is in accord with results from other languages (e.g., Fagard et al. Citation2016). The concept of functional deixis introduced by Matsumoto, Akita, and Takahashi (Citation2017) appears to explain this phenomenon: the goal in expressions built around venitiveFootnote22 verbs is often the “space for the speaker’s potential interaction with the moving person” alongside or instead of the actual location of the speaker (Matsumoto, Akita, and Takahashi Citation2017, 117). This functionally defined space can be either the concrete space occupied by the speaker or, as is the case in our test setting, a space visible to the speaker.

In the AM data, spatial deixis was expressed also with other kinds of deictic resources alongside the deictic verbs. These included mainly demonstrative adverbs and overt references to the viewer (e.g., adpositional phrases such as minua kohti ‘towards me’) (see Tuuri (Citation2023) for discussion of these elements in Finnish). Importantly, the overt viewer references appeared only in descriptions of 1pp stimuli. Matsumoto, Akita, and Takahashi (Citation2017, 117) also state that these kinds of PPs are transparently directional and thus cannot express functional deixis, which could explain why they are not used for 3pp stimuli.

In sum, the results from the AM data indicate that deictic verbs are a central resource in the expressions of BC in Path:beg and Path:end in both Finnish and Estonian. The use of these verbs is not restricted by the perspective in the stimuli as is the case for other deictic resources. The deictic verbs rather express changes in visibility, such as coming into sight or going out of sight. This tendency is manifested in both languages, but it is affected by cross-linguistic differences such as the Estonian language generally applying more analytic constructions than Finnish and thus using deictic verbs with Path particles in a wider array of contexts.

5. The use of deictic verbs in expressions of NAM

The main goal of this study is to investigate whether the connection between BC and deictic verbs is retained in NAM. As background, we discuss the role of the deictic resources in the NAM descriptions (Section 5.1) and, more specifically, report on the use of deictic verbs in expressions of different trajectory types (Section 5.2). Next, we present the results on the use of deictic verbs in descriptions of BC situations in the NAM data (Section 5.3). Finally, we observe variation between participants to see how pervasive the discovered tendencies are in the languages under study (5.4). Interestingly, the proportion of NAM constructions was almost the same in both languages: the Finnish participants used NAM constructions in 46.6% of the descriptions of the target stimuli (n = 1,200), the Estonian participants in 44.7% (n = 600).Footnote23 Similarly, the number of NAM descriptions was around 40% in Swedish, French, and Thai (Blomberg Citation2015, 685), as well as in Khasi studied with the same stimuli (Wahlang and Koshy Citation2018, 46). In contrast, Stosic et al. (Citation2015, 223) report significant variation in the mean frequency of NAM expressions in descriptions collected with the same stimuli from French, Italian, German, and Serbian speakers (from 30% in Italian to 50% in German).

5.1. Deictic resources in expressions of NAM

The verbs in the elicited NAM descriptions in Finnish and Estonian came from a limited set, as has been shown for other languages (see Blomberg Citation2015). As predicted by Matsumoto (Citation1996), the most common NAM verbs were generic motion verbs not containing information on Manner (see ). The role of deictic motion verbs was considerable: of the Finnish NAM descriptions (n = 1,200), 53.7% included either mennä, tulla, or both, while in the Estonian NAM descriptions (n = 600), 43.5% were encoded with minema, tulema, or both. The andative verbs were more commonly used in NAM descriptions than the venitive verbs and this correlates with other studies, such as Waliński’s (Citation2018, 171) corpus-based observations on English. As mentioned in Section 2.3, NAM expressions appear to avoid the use of Manner verbs and, accordingly, the use of such verbs was very restricted in our data. In Estonian, there were eight instances of the verb jooksma ‘run’, and in Finnish, four instances of the verb sukeltaa ‘dive, plunge’.

Table 2. The most common NAM verbs in the Finnish and Estonian data.Footnote24 Overall, 21 different verbs were used in Finnish NAM expressions, 17 in Estonian.

The most obvious difference between the verb selections was the central role of the verb viima ‘take, lead’ in Estonian and the notably lower frequency of the Finnish counterpart viedä ‘take, lead’. The basic AM meaning of these verbs is deictic: the Finnish verbs tuoda and viedä and the Estonian verbs tooma and viima express the same deictic opposition as the English bring and take that are described as causative variants to come and go (Fillmore Citation1971, 273; see also Pajusalu Citation2004).Footnote26 It is, however, unclear how much of the deictic meaning is retained in the use of these verbs in expressions of NAM. The setting does not allow testing of these verbs because directionality is not predetermined in static pictures. The same tunnel, for example, can be perceived as the starting point or the end point of a road (see ).

In what follows, we concentrate on deictic verbs, not other deictic elements (see Section 4). Other deictic resources were used only sporadically in the Finnish and Estonian NAM data. Overt viewer-references, such as PPs expressing ‘toward me’, were never used. This deviates from the AM data, where these PPs were a central source of individual variation and a strategy used extensively by some participants (see Tuuri Citation2023 for Finnish). The fact that the same participants did not use this strategy in the NAM task implies differences in deictic anchoring between encoding NAM and AM. It is possible that explicit reference to the viewer would foreground the viewer’s perspective unnecessarily, while deictic motion verbs are conventionally used in NAM constructions.

5.2. Deictic verbs in the NAM expression of different spatial trajectories

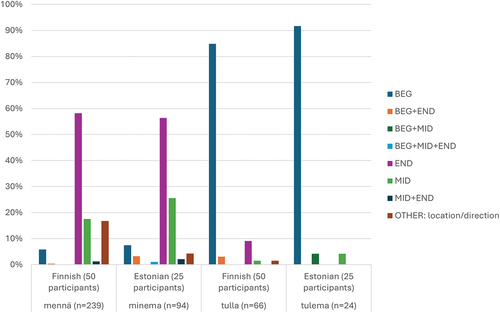

To further observe the semantics of the deictic verbs in Finnish and Estonian NAM expressions, we turn to an analysis of the use of these verbs in the expression of different spatial trajectories, followed by a brief comparison to corresponding results on the AM data (see Section 4). presents the percentages of the deictic motion verbs in Finnish and Estonian classified according to the trajectory type encoded in each clausal context: the beg(inning), mid(dle), or end of the Path, the combinations of these, or the class ‘other’ mainly consisting of unbounded Direction and locative expressions. In the case of multiclausal descriptions, only the clause including the deictic verb was included.

Figure 3. The use of Finnish and Estonian deictic motion verbs according to the spatial transitions expressed in the clause. The infrequent combinations of the two deictic verbs (n = 4 in Finnish, n = 1 in Estonian) have been excluded.

The frequencies of the two venitive verbs were low (Finnish tulla, n = 66; Estonian tulema, n = 24), but it is clear that their occurrences clustered in the expressions of Path:beg (‘out of’) or complex trajectories including Path:begFootnote27 88% of tulla and 96% of tulema appeared in these contexts (see (7)).

In the use of andative verbs, there was more variation. Sixty per cent of the occurrences of the Finnish mennä (n = 239) and 63% of the Estonian minema (n = 94) appeared in expressions including Path:end (‘into’). In the contexts of the andative verbs, two phenomena are noticeable. First, 19% of the occurrences of mennä and 29% of the occurrences of minema appeared in expressions including Path:mid (‘across’). In these descriptions, the verb was accompanied by an adpositional phrase expressing Path:mid, as in (8).

Second, in Finnish, 17% of the occurrences were marked with the code ‘other’, while in Estonian, this category was not prominent. The category consists mainly of descriptions with a locative adverbial, as in (9). Locative expressions were used by various Finnish participants and for stimuli with different figures, which is interesting considering that this expression type was limited to one occurrence in the Finnish AM data (see (10)).

Overall, the venitive verbs in the Finnish and Estonian NAM data appeared almost exclusively in expressions of Path:beg, in line with the results from the AM data. For the andative verbs in NAM expressions, Path:end was the most typical context, but they were also regularly used in expressions of other types of trajectories. This diversity of contexts is an indication of the generic nature of andative verbs in NAM expressions (see the discussion on English go as a NAM verb by Waliński (Citation2018, 172)). On the other hand, for Estonian, the use of minema was rather generic also in the AM data. In Finnish, instead, the NAM use of mennä differs from the AM use, as the latter clusters more clearly in the expression of Path:end.

5.3. BC in NAM expressions

One possible explanation for the use of deictic verbs in NAM expression is directionality in relation to the viewpoint, as would be expected considering the deictic opposition connected to andative and venitive verbs. If this was the case, 1pp stimuli (in which the orientation of the figure aligns with the direction of the speaker’s gaze) would outnumber 3pp stimuli (in which the orientation of the figure is neutral with respect to the viewpoint) in the use of deictic verbs. However, deictic verbs are used in the descriptions irrespective of perspective (see ). They are used both for 1pp stimuli and 3pp stimuli. 3pp is even more frequent in the use of the andative verbs. Next, we will discuss BC as an explanation for the use of deictic verbs.

Figure 4. Occurrences of the deictic verbs per the two different perspectives (1pp vs. 3pp). In the whole data, NAM expressions were produced for both perspectives somewhat evenly, with a slight preference for 1pp (52% in Finnish [n = 559]; 51% in Estonian [n = 269]).

![Figure 4. Occurrences of the deictic verbs per the two different perspectives (1pp vs. 3pp). In the whole data, NAM expressions were produced for both perspectives somewhat evenly, with a slight preference for 1pp (52% in Finnish [n = 559]; 51% in Estonian [n = 269]).](/cms/asset/43f6a5d4-a3c9-48e6-a9be-817323a48769/salh_a_2347760_f0004_oc.jpg)

We continue with a stimulus-based analysis on BC. As discussed in Section 3.1, some of the static configurations in the stimuli can be treated as analogous to videos with BC. Of the 24 target stimuli, eight are conceivable as Path:beg or Path:end with BC and eight as Path:beg or Path:end without BC (see and ). We do not differentiate between Path:beg and Path:end on the level of the stimuli, as the directionality is not predetermined in static pictures.Footnote28 These 16 stimuli also vary systematically with respect to perspective and affordance for motion.

Figure 5. Examples of stimuli analysed in this section. The road picture represents the variables +BC, 1pp, and +afford, and the fence picture represents the variables -BC, 3pp, and -afford.

Table 3. Schematic representation of the NAM stimuli (16/24) included in the current comparison. The presentation is adapted from Blomberg (Citation2015, 668).

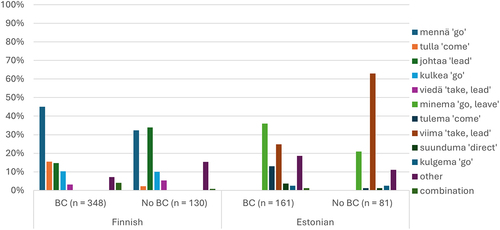

Within this set of stimuli, the deictic verbs showed a pattern of focusing on the BC situations (see ). In the Finnish NAM descriptions of the stimuli with BC (n = 348), mennä was the most common verb, used in 45% of the descriptions, while tulla was used in 16%. In descriptions of stimuli without BC (n = 130), mennä was used in 32% of the descriptions, tulla in only 2%. In Estonian, 36% of the descriptions of the BC stimuli (n = 161) were encoded with minema, 13% with tulema. In descriptions of stimuli without BC (n = 81), minema was used in 21% and tulema in 1% of the descriptions.Footnote29

The frequencies of venitive verbs are not sufficiently high for further analysis, but they do indicate the same tendency in both languages, being clearly higher in the BC condition. In the case of the more frequent andative verbs, the difference between the two conditions is notable in both languages. For stimuli with BC, mennä and minema were the most typical options, as in (11), while for stimuli without BC, the Finnish participants slightly favored the use of johtaa ‘lead’ (35%) and the Estonian participants more clearly favored the use of viima ‘take, lead’ (63%), as in (12). For stimuli with BC, these verbs were not as common, as johtaa was used in 15% of the Finnish descriptions and viima in 25% of the Estonian descriptions. It thus seems that while the andative and venitive verbs are preferred in BC expressions, other typical NAM verbs are opted for in expressions without BC. Interestingly, the verb viima ’take, lead’, although deictic in its AM meaning, does not pattern with the standard deictic verbs but rather expresses goal-directedness along with the Finnish johtaa ‘lead’:

In general, the use of deictic verbs was more frequent in the descriptions of the BC stimuli than in the descriptions of no BC stimuli.

One more factor to consider as affecting this distribution is the affordance for motion of the figures represented in the stimuli. In this connection, it is possible to present only a few observations and leave the full picture for future studies. In the general production of NAM expressions in the whole data, there was an expected preference for the +afford condition (see Blomberg and Zlatev Citation2014): 61% of NAM descriptions in Finnish (n = 559) and 64% in Estonian (n = 268) were produced for +afford stimuli. Observing the use of deictic verbs in relation to the affordance variable, we can see the andative verbs largely following the general pattern, with more occurrences for +afford stimuli, but, unexpectedly, the venitive verbs were used more frequently for -afford stimuli (in about two-thirds of the descriptions in both languages). However, a closer look shows that the figure types most frequently expressed with deictic verbs included roads and trails (+afford) but also pipes (−afford). Pipes are somewhat problematic to define with respect to affordance, as they are not only linear static entities but also objects used for transportation of flowing liquids (Blomberg Citation2014, 193). Indeed, Stosic et al. (Citation2015) suggest a reorganization of the stimuli into three figure types: figures affording human motion, figures affording non-human motion, and figures not affording motion. Acknowledging the issues related to this variable, we leave this discussion to be continued with more data from different sources (Pajunen et al. Citation2023).

5.4. Variation between participants in the use of deictic verbs

The results presented in the previous sections suggest that in the Finnish and Estonian expression of NAM, deictic verbs tend to be used especially in descriptions of BC in Path:beg and Path:end. However, the number of deictic verbs produced in the NAM task varied greatly between the participants in both languages. In this section, we present a few remarks on the individual variation in the data.

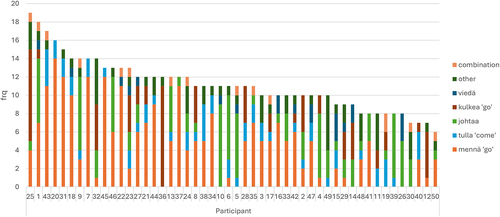

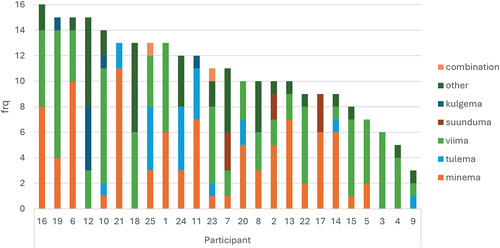

In both languages, every participant used NAM constructions to describe the stimuli, but to varying degrees. Within the group of Finnish participants, the lowest number of NAM descriptions was 6/24 and the highest 19/24 (average approx. 11/24). In Estonian, the corresponding numbers were 3/24 and 16/24 (average approx. 11/24). In addition, there was extensive variation in the verb choices made in the NAM descriptions (see ).

Figure 7. Individual variation in the number of NAM constructions produced by participant in the Finnish data. The stacked colors in the columns represent different choices of verbs, simplified into the five most common verbs, other verbs, and combinations of two or more verbs.

Figure 8. Individual variation in the number of NAM constructions and the verbs produced by participant in the Estonian data (cf. Figure 7).

As discussed in Section 5.1, in both Finnish and Estonian, the number of different NAM verbs is somewhat limited, and deictic verbs, especially mennä and minema, were used frequently. In relation to this, it is interesting that in both languages, there were participants who did not use deictic verbs at all (5/50 in Finnish and 4/25 in Estonian). On the other hand, there were participants who relied only on deictic verbs in their NAM expressions (3/50 in Finnish and in 1/25 Estonian).

The individual variation shows that in Finnish and Estonian NAM expressions, the use of deictic verbs in BC situations is an optional encoding strategy, albeit a common one. Thus, while in verb-framed languages the BC constraint largely defines the verbal expression of BC, in satellite-framed languages, there may rather exist a tendency to emphasize BC with the choice of verbs expressing functional deixis and highlighting, for example, changes in visibility.

6. Conclusions

Satellite-framed languages have not attracted a lot of attention in research on BC in motion expressions, as these languages are not affected by similar constraints in this area of expression as verb-framed languages (Aske Citation1989; Slobin and Hoiting Citation1994). Spatial boundaries are, however, central to perception, and it is to be expected that they would evoke specific encoding patterns in different types of languages. We have presented results suggesting that in Finnish and Estonian, included in the satellite-framed type by Talmy (Citation2000b), deictic motion verbs tend to occur in BC situations of Path:beg (i.e., exiting a landmark) and Path:end (i.e., entering a landmark) (see also Tuuri and Belliard Citation2021). Furthermore, we have shown that this tendency occurs not only in the expression of concrete, actual motion (AM) but also in the more abstract expression of non-actual motion (NAM), i.e., static spatial configurations described in terms of motion.

BC situations typically represent transitions in relation to the visual field or circle of attention of the speaker. Matsumoto, Akita, and Takahashi (Citation2017) connect these factors to functional deixis, which they argue to be a central component in the meaning of deictic verbs alongside purely spatial directionality. Our analysis, based on data collected with visual elicitation tools (Blomberg Citation2014; Ishibashi, Kopecka, and Vuillermet Citation2006), showed that the Finnish verbs tulla ‘come’ and mennä ‘go’ and the Estonian verbs tulema ‘come’ and minema ‘go, leave’ were more likely to be used for stimuli with BC than for stimuli with no BC. Crucially, other common NAM verbs in the data, such as Finnish johtaa ‘lead’ or Estonian viima ‘take, lead’ did not show similar patterning according to the BC variable.

The venitive (‘come’) and andative (‘go’) verbs were, somewhat surprisingly, widely used for 3pp stimuli (with motion pictured from the side in AM or with the figure not aligning with the viewer’s gaze in NAM) alongside 1pp stimuli (with motion away or towards the viewer in AM or with the figure aligning with the viewer’s gaze in NAM). Consistent results have been reported for venitive verbs in corresponding elicited AM data from Swedish and German (Fagard et al. Citation2016). Together, these results indicate that deictic directionality is not enough to account for the use of these verbs. Instead, the deictic verbs can be used as a strategy to emphasize the aspect of the Figure moving between closed and open spaces, entering a Landmark and thus moving out of sight, or exiting a Landmark and thus moving into sight. In NAM, there is no actual, physical translocation, but, for example, a road is not visible to the viewer in its entirety as it extends far inside a tunnel. For these situations analogous to BC, the use of deictic verbs was found to be more common than for other types of stimuli.

Despite the general tendencies, there was extensive variation between participants in the use of deictic verbs in both Finnish and Estonian. This indicates that the use of deictic verbs in BC situations in these languages is indeed a tendency or an optional encoding strategy rather than a strict constraint.

With our analysis of two Uralic languages, we also wish to contribute research on spatial deixis within the typology of motion encoding (Sarda and Fagard Citation2022). One such contribution is the evidence provided in support of the conceptual separation of deixis from the non-deictic Path, as the expression of deixis clearly shows specific patterns (see, e.g., Matsumoto, Akita, and Takahashi Citation2017). Our results were also in line with the generally acknowledged tendency that venitive verbs such as come are more deictic in nature than andative verbs such as go. In the NAM data, venitive verbs were used less frequently and in more limited contexts. Andative verbs were used for a more varying set of stimuli, which seems to support the idea of mennä and minema appearing as somewhat generic motion verbs in NAM contexts.

This study also offers new insights for the cross-linguistic research on NAM (see Blomberg Citation2015). The overall use of NAM expressions was on the same level in Finnish and Estonian, but the use of andative and venitive verbs was more frequent in Finnish. In contrast, in the AM data provided by the same speakers, the same verbs played a more central role in Estonian and were used in a wider range of different situations than in Finnish. One explanation for this difference was the frequent use of the verb viima ‘take, lead’ in Estonian NAM descriptions. This can be seen as an example of individual, frequent lexical units creating unexpected cross-linguistic differences. Overall, the verbal expression of NAM calls for wider research.

The elicitation method is effective in targeting phenomena that are beyond the limits of intuition and laborious to extract from corpora. The most obvious benefit of the method is the possibility of systematic comparisons on different levels of variation. Yet, because of the unnaturalness of the elicitation situation, future studies should investigate whether deictic verbs cluster in expressions of BC also in other types of data and collect larger datasets allowing statistical analysis. Additionally, a potential challenge linked to the elicitation method is syntactic priming. In our data, the tendency to repeat the same structures varies strongly between participants. Consequently, the relatively large number of participants for the task type, especially in Finnish, may alleviate the significance of the priming effect.

Concerning deixis, the test setting of describing stimuli on a screen creates an extra dimension requiring attention in the future. One modification to consider would be adding more interaction. In our study, the participants encoded the stimuli with the awareness that the researcher was seeing the same material. If the setting included another person to whom the stimuli would have to be explained, then more elaboration on deictic directionality might be encountered.

Acknowledgments

We wish to thank all the participants in the study. We would also like to thank the participants of the Langnet seminar of the Grammar, Semantics and Typology group at Åbo Akademi University in August 2023 for valuable comments on parts of this paper. We thank the two anonymous reviewers and the editor Peter Juul Nielsen for insightful suggestions that have considerably improved the article.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes

1 It is a debated question whether languages relying on cases in their expression of Path should be included in the satellite-framed type (see, e.g., Ibarretxe-Antuñano Citation2017, 19). As this discussion is beyond the scope of this article, we will use the traditional classification of Finnish and Estonian as satellite-framed languages.

2 References to data include the following information: elicitation tool (fm = Fictive motion; tr = Trajectoire; see Section 3.1), language (Fi = Finnish, Ee = Estonian), participant number, and stimulus number. Abbreviations in the interlinear glosses follow the Leipzig Glossing Rules (https://www.eva.mpg.de/lingua/resources/glossing-rules.php), complemented with ade = adessive, ine = inessive, and ter = terminative.

3 In Finnish and Estonian grammar writing traditions, different infinitive forms are used as the basic form: in Finnish the A-infinitive, in Estonian the MA-infinitive.

4 Taremaa (Citation2013) searched data from a corpus, first using nouns suitable for NAM expressions (e.g., tee ‘path, road’) and then using verbs found in these constructions. For each verb, 1000 sentences were analysed, and among the minema sentences, minema was used only once for expressing NAM. However, this does not seem to demonstrate the non-suitability of minema in NAM expressions, but rather to be the polysemous nature of minema that reduces the probability of finding NAM uses in a 1000-sentence sample.

5 There are, however, certain exceptions to the constraint, such as very rapid or instantaneous BC situations allowing Manner verbs in Turkish (Özçaliskan, Citation2015, 9).

6 HSS (see, Zlatev, Blomberg, and David Citation2010, Blomberg Citation2014, Zlatev et al. Citation2021, Naidu et al. Citation2022) separates the concepts of Path and Direction. The category of Path is reserved for bounded, telic motion situations (AM or NAM) and schematised as three different phases in the state-transition of the Figure: beg(inning) (e.g., from the house, out of the house), mid(dle) (e.g., across the street, through the field) and end (e.g., to the house, into the house). Direction is the category covering unbounded, atelic motion situations (e.g., upwards, this way).

7 Note that läheb in (5) is a form of minema ‘go, leave’. The suppletive paradigm of the verb is explained in Section 4.

8 From the subtypes of fictive motion defined by Talmy (Citation2000a, 138–139), the instances discussed in this article represent the coextension path.

9 The concept of enactive perception emphasizes that our perception of the physical world is affected by our own ability to move (see Blomberg and Zlatev Citation2014).

10 The spatial configurations also vary systematically on the horizontal axis (figures in either left or right in 3pp pictures) and on the frontal axis (figures proximal or distal with respect to viewpoint in 1pp pictures) (Blomberg Citation2015, 666–667).

11 This order may lead to some priming for use of motion verbs in the second task. This does not affect the comparison between Finnish and Estonian, as the setting was the same for both languages.

12 For data protection according to the GDPR that came to existence between the two data collections, the age information of the Estonian participants was collected as age ranges.

13 The data collection in Estonia received ethics approval from Research Ethics Committee of the University of Tartu (approval no. 302/M-2). The Finnish legislation does not require ethics approval for this type of data collection.

14 The participants were asked to describe the stimuli in about one sentence, but this was not a strict demand. The approximate numbers of finite clauses per stimulus per participant were the following: Finnish AM 1.26, NAM 1.33; Estonian AM 1.60, NAM 1.58. Of the Finnish AM descriptions, 10 are missing due to a technical error.

15 Deictic motion verbs tend to be highly polysemous. In this study, the use of visual stimuli ensures the collection of sentences expressing either AM or NAM. The data were also checked manually to make sure no other usages were included.

16 Wilkins and Hill (Citation1995) show that an inherently deictic go verb is not a linguistic universal, but they also state that the polysemous go verbs often gain a strong deictic implication through systemic opposition to inherently deictic come verbs.

17 These figures include the use of deictic verbs in expressions of Path:end and in more complex combinations of different trajectory types including Path:end. We have manually checked that the deictic verbs appear in expressions of Path:end in these descriptions.

18 Overall, there was a slight bias towards BC in the AM stimuli, which led to 57% of the Finnish descriptions and 60% of the Estonian descriptions including a BC expression. Even considering this, the role of BC in the use of deictic verbs is notable.

19 The percentages concerning Path:beg have been obtained through a procedure corresponding the one explained in footnote 17.

20 This class consists mostly of vertical direction verbs such as Finnish nousta ‘ascend’.

21 In Finnish and Estonian, the six spatial cases are the main expression of Path. They also specify Region, with a topological difference between internal cases (inessive ‘inside’, elative ‘out of’, illative ‘into’) and the external cases (adessive ‘by, at, on’, ablative ‘from’, allative ‘to’). The Estonian system also includes the terminative case ‘up to, as far as’, which is, interestingly, only used once in our AM data but somewhat often in the NAM data (see (12)).

22 Matsumoto, Akita, and Takahashi (Citation2017, 118) concentrate on venitive verbs but are open for the possibility that the same effect could be found in the use of andative verbs.

23 It should be repeated that one of the goals of the task was to explore constraints on the use of NAM expressions, meaning that some of the stimuli were expected to be less likely to evoke NAM descriptions than others.

24 These results can be compared to Blomberg’s (Citation2015, 686) results acquired with the same stimuli: In Swedish, the andative gå ‘go, walk’ was used in 39.4% of the NAM descriptions, and the venitive komma ‘come’ in 8.8%. In this respect, Swedish appears to be situated between Finnish and Estonian. French, however, deviated from this pattern. The verb aller ‘go’ covered 9.5% of the NAM descriptions, while venir ‘come’ was not among the most used NAM verbs.

25 Both mennä and kulkea are translated as go, but kulkea is non-deictic. Additionally, kulkea more often refers to moving on foot (KS 2020, sv. kulkea).

26 Interestingly, tooma ‘bring’ is used as a NAM verb in one description in Estonian: Korralik tee toob kohe treppi [fmEe#9-14] ‘A proper road brings right to the stairs’. In Finnish, corresponding use of tuoda ‘bring’ seems unnatural.

27 The somewhat infrequent combinations of different trajectory types are presented separately in but included in the calculations presented in the text for the sake of comparability with the AM results (Section 4).:

28 We exclude stimuli with BC in Path:mid because focusing on Path:beg and Path:end allows comparison to our AM results. Furthermore, the line between Path:mid and unbounded trajectories is often open to interpretation in the stimuli: for example, a bridge over a ravine is easily conceived as BC with respect to a linear boundary, but a row of stones in a river may be interpreted as a path crossing the water or an unbounded trajectory.

29 These figures do not include the deictic verbs that appear in descriptions with two or more verbs. These were included in the category ‘combination’.

References

- Alumäe, Tanel, Ottokar Tilk, and Asadullah. 2018. “Advanced Rich Transcription System for Estonian Speech.” In Human language technologies – The Baltic perspective: Proceedings of the Eighth International Conference Baltic HLT 2018, edited by Kadri Muischnek and Kaili Müürisep, 1–8. Amsterdam: IOS Press.

- Anderson, Stephen R., and Edward Keenan. 1985. “Deixis.” In Language Typology and Syntactic description, Volume 3: Grammatical Categories and the Lexicon, edited by Timothy Shopen, 259–308. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Aske, Jon. 1989. “Path Predicates in English and Spanish: A Closer Look.” In Proceedings of the Fifteenth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, edited by Kira Hall, Michael Meacham, and Richard Shapiro, 1–14. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

- Baker, Lewis J., and Daniel T. Levin. 2015. “The Role of Relational Triggers in Event Perception.” Cognition 136: 14–29. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2014.11.030.

- Barsalou, Lawrence W. 2008. “Grounded Cognition.” Annual Review of Psychology 71 (1): 230–244.

- Blomberg, Johan. 2014. “Motion in Language and Experience: Actual and Non-Actual Motion in Swedish, French and Thai.” PhD diss., Lund University.

- Blomberg, Johan. 2015. “The Expression of Non-Actual Motion in Swedish, French and Thai.” Cognitive Linguistics 26 (4): 657–696. https://doi.org/10.1515/cog-2015-0025.

- Blomberg, Johan, and Jordan Zlatev. 2014. “Actual and Non-Actual Motion: Why Experientialist Semantics Needs Phenomenology (And Vice Versa).” Phenomenology and the Cognitive Sciences 13 (3): 395–418. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11097-013-9299-x.

- Denny, J. Peter. 1978. “Locating the Universals in Lexical Systems for Spatial Deixis.” In Papers from the Parasessions of the Lexicon, edited by Donka Farkas, M. Jacobsen Wesley, and W. Todrys Karol, 71–84. Chicago: Chicago Linguistic Society.

- Fagard, Benjamin, Jordan Zlatev, Anetta Kopecka, Massimo Cerruti, and Johan Blomberg. 2016. “The Expression of Motion Events: A Quantitative Study of Six Typologically Varied Languages.” In Proceedings of the Thirty-Ninth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society, edited by Matthew Faytak, Matthew Goss, Nicholas Baier, John Merrill, Kelsey Neely, Erin Donnelly, and Jevon Heath, 364–379. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

- Fillmore, Charles J. 1971. Santa Cruz Lectures on Deixis 1971. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Linguistics Club.

- Huumo, Tuomas. 2009. “Fictive Dynamicity, Nominal Aspect, and the Finnish Copulative Construction.” Cognitive Linguistics 20 (1): 43–70. https://doi.org/10.1515/COGL.2009.003.

- Huumo, Tuomas. 2013. “Many Ways of Moving Along a Path: What Distinguishes Prepositional and Postpositional Uses of Finnish Path Adpositions?” Lingua 133: 319–335. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.lingua.2013.05.006.

- Ibarretxe-Antuñano, Iraide. 2017. “Introduction. Motion and Semantic Typology: Cognitive Foundations of Language Structure and Use.” In Motion and Space Across Languages, edited by Iraide Ibarretxe-Antuñano, 13–36. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Ishibashi, Miyuki, Anetta Kopecka, and Marine Vuillermet. 2006. Trajectoire: Matériel visuel pour élicitation des données linguistiques. Laboratoire Dynamique du Langage, CRNS, Université Lyon 2. Fédération de Recherche en Typologie et Universaux Linguistiques. http://tulquest.huma-num.fr/fr/node/132.

- Karsikas, Elina. 2004. ““Tuli huikean avara suo, ja sen kainalosta hyppäsi taivaille karmea vuori. Spatiaalisen sijainnin ilmaiseminen fiktiivisenä liikkeenä” [Tuli huikean avara suo, ja sen kainalosta hyppäsi taivaille karmea vuori. Spatial location depicted in the terms of fictive motion].” Sananjalka 46 (1): 7–39.

- KS = Kielitoimiston sanakirja [Dictionary of Contemporary Finnish]. 2020. Helsinki: Institute for the Languages of Finland. https://www.kielitoimistonsanakirja.fi/.

- Langacker, Ronald W. 1987. “Foundations of Cognitive Grammar: Theoretical Prerequisites.” Vol. 1. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- Larjavaara, Matti. 1990. Suomen deiksis [Finnish deixis]. Helsinki: Finnish Literature Society.

- Matlock, Teenie. 2010. “Abstract Motion Is No Longer Abstract.” Language and Cognition 2 (2): 243–260. https://doi.org/10.1515/langcog.2010.010.

- Matsumoto, Yo. 1996. “Subjective Motion and English and Japanese Verbs.” Cognitive Linguistics 7 (2): 183–226. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.1996.7.2.183.

- Matsumoto, Yo, Kimi Akita, and Kiyoko Takahashi. 2017. “The Functional Nature of Deictic Verbs and the Coding Patterns of Deixis: An Experimental Study in English, Japanese, and Thai.” In Motion and Space Across Languages, edited by Iraide Ibarretxe-Antuñano, 95–122. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Morita, Takahiro. 2022. “What Does Deixis Tell Us About Motion Typology? Linguistic or Cultural Variations of speakers’ ‘Here’ Space Vis-à-Vis Perceived Physical Events.” In Neglected Aspects of Motion-Event Description: Deixis, Asymmetries, Constructions, edited by Laure Sarda and Benjamin Fagard, 25–41. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Naidu, Viswanatha, Jordan Zlatev, and Joost Van De Weijer. 2022. “Typological Features of Telugu: Defining the Parameters of Post-Talmian Motion Event Typology.” Acta Linguistica Hafniensia 54 (2): 205–234. https://doi.org/10.1080/03740463.2022.2132563.

- Özçaliskan, Şeyda. 2015. “Ways of Crossing a Spatial Boundary in Typologically Distinct Languages.” Applied Psycholinguistics 36 (2): 485–508. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0142716413000325.

- Pajunen, Anneli, Emilia Tuuri, and Esa Itkonen. 2023. “Concerning the Expression of Non-Actual (= fictive) Motion in Finnish: A Multi-Method Analysis.” Manuscript in preparation [last modified 12/2023].

- Pajusalu, Renate. 2004. “Tuumverbid ja deiksis” [Core verbs and deixis]. In Tuumsõnade semantikat ja pragmaatikat [On the semantics and pragmatics of core verbs], edited by Renate Pajusalu, Ilona Tragel, Ann Veismann, and Maigi Vija, 53–61. Tartu: University of Tartu Library.

- Pällin, Kristi, and Annekatrin Kaivapalu. 2012. “Suomen mennä ja lähteä vertailussa: Lähtökohtana vironkielinen suomenoppija” [Finnish verbs mennä ’go’ and lähteä ’leave’ as the challenge for Estonian learners of Finnish]. Lähivõrdlusi. Lähivertailuja 22: 287–323. https://doi.org/10.5128/LV22.10.

- Pällin, Kristi, and Annekatrin Kaivapalu. 2013. “One-To-Many Mapping Between Closely Related Languages and Its Influence on Second Language Acquisition.” Paper presented at Learner Corpus Research Conference, Bergen, Norway, September 2013. Accessed March 28, 2024. https://view.officeapps.live.com/op/view.aspx?src=https%3A%2F%2Flcr2013.w.uib.no%2Ffiles%2F2013%2F10%2FLCRBergen2013_P%25C3%25A4llinKaivapalu_27.9._kommentaarideta.pptx&wdOrigin=BROWSELINK.

- Sarda, Laure, and Benjamin Fagard. 2022. “Introduction: The Description of Motion Events. On Deixis, Asymmetries and Constructions.” In Neglected Aspects of Motion-Event Description: Deixis, Asymmetries, Constructions, edited by Laure Sarda and Benjamin Fagard, 1–24. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Slobin, Dan I. 2006. “What Makes Manner of Motion Salient? Explorations in Linguistic Typology, Discourse, and Cognition.” In Space in Languages: Linguistic Systems and Cognitive Categories, edited by Maya Hickmann and Stéphane Robert, 59–81. Amsterdam: John Benjamins.

- Slobin, Dan I., and Nini Hoiting. 1994. “Reference to Movement in Spoken and Signed Languages: Typological Considerations.” In Proceedings of the Twentieth Annual Meeting of the Berkeley Linguistics Society: General session dedicated to the contributions of Charles J. Fillmore, edited by Susanne Gahl, Andy Dolbey, and Christopher Johnson, 487–505. Berkeley: Berkeley Linguistics Society.

- Sloetjes, Han, and Peter Wittenburg. 2008. “Annotation by Category – ELAN and ISO DCR.” In Proceedings of the 6th International Conference on Language Resources and Evaluation, edited by Nicoletta Calzolari, Khalid Choukri, Bente Maegaard, Joseph Mariani, Jan Odijk, Stelios Piperidis, and Daniel Tapias, 816–820. Luxembourg: European Language Resources Association (ELRA).

- Stosic, Dejan, Benjamin Fagard, Laure Sarda, and Camille Colin. 2015. “Does the Road Go Up the Mountain? Fictive Motion Between Linguistic Conventions and Cognitive Motivations.” Cognitive Processing 16 (Suppl 1): 221–225. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10339-015-0723-8.

- Talmy, Leonard. 1983. “How Language Structures Space.” In Spatial Orientation: Theory, Research and Application, edited by Herbert L. Pick and Linda Acredolo, 225–282. New York: Plenum Press.

- Talmy, Leonard. 2000a. Toward a Cognitive Semantics, Vol. 1: Concept Structuring Systems. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Talmy, Leonard. 2000b. Toward a Cognitive Semantics. Vol. 2: Typology and Process in Concept Structuring. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

- Taremaa, Piia. 2013. “Fictive and Actual Motion in Estonian: Encoding Space.” SKY Journal of Linguistics 26 (1): 151–183.

- Taremaa, Piia. 2017. Attention Meets Language: A Corpus Study on the Expression of Motion in Estonian. PhD diss., University of Tartu.

- Tuuri, Emilia. 2021. ““Liiketilanteen väylän ja suunnan kielentäminen suomessa” [Expressing path and direction of motion situation in Finnish].” In Suomen kielen hallinta ja sen kehitys: Peruskoululaiset ja nuoret aikuiset [Later language development in Finnish: School-age children and young adults], edited by Anneli Pajunen and Mari Honko, 108–154. Helsinki: SKS.

- Tuuri, Emilia. 2023. “Concerning Variation in Encoding Spatial Motion: Evidence from Finnish.” Nordic Journal of Linguistics 46 (1): 83–104. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0332586521000202.

- Tuuri, Emilia, and Maija Belliard. 2021. “Liikkeen kielentämisen variaatio lähisukukielissä: Väylän alun ja lopun ilmaisu suomessa ja virossa” [Variation in encoding motion in closely related languages: expressing beginning and end of Path in Finnish and Estonian].” Finnish Journal of Linguistics 34 (1): 257–299.

- Verkerk, Annemarie. 2013. “Scramble, Scurry and Dash: The Correlation Between Motion Event Encoding and Manner Verb Lexicon Size in Indo-European.” Language Dynamics and Change 3 (2): 169–217. https://doi.org/10.1163/22105832-13030202.

- Vuillermet, Marine, and Anetta Kopecka. 2019. “Trajectoire: A Methodological Tool for Eliciting Path of Motion.” In Methodological Tools for Linguistic Description and Typology, Language Documentation & Conservation Special Publication No. 16, edited by Aimée Lahaussois and Marine Vuillermet, 97–124. Honolulu: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Wahlang, Maranatha Grace T., and Anish Koshy. 2018. “Descriptions of Co-Extension Paths in Khasi.” Journal of the Southeast Asian Linguistics Society 11 (2): 42–66.

- Waliński, Jacek. 2018. Verbs in Fictive Motion. Łódź: Łódź University Press.

- Wilkins, David P., and Deborah Hill. 1995. “When ‘Go’ Means ‘Come’: Questions on the Basicness of Basic Motion Verbs.” Cognitive Linguistics 6 (2–3): 209–259. https://doi.org/10.1515/cogl.1995.6.2-3.209.

- Zacks, Jeffrey M. 2020. “Event Perception and Memory.” Annual Review of Psychology 71 (1): 165–191. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010419-051101.

- Zacks, Jeffrey M., and Barbara Tversky. 2001. “Event Structure in Perception and Conception.” Psychological Bulletin 127 (1): 3–21. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-2909.127.1.3.

- Zlatev, Jordan, Johan Blomberg, Simon Devylder, Viswanatha Naidu, and Joost van de Weijer. 2021. “Motion Event Descriptions in Swedish, French, Thai and Telugu: A Study in Post-Talmian Motion Event Typology.” Acta Linguistica Hafniensia 53 (1): 58–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/03740463.2020.1865692.

- Zlatev, Jordan, Johan Blomberg, and Caroline David. 2010. “Translocation, Language and the Categorization of Experience.” In Language, Cognition and Space. The State of the Art and New Directions, edited by Vyvyan Evans and Paul Chilton, 389–418. Sheffield: Equinox.