?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.

?Mathematical formulae have been encoded as MathML and are displayed in this HTML version using MathJax in order to improve their display. Uncheck the box to turn MathJax off. This feature requires Javascript. Click on a formula to zoom.ABSTRACT

The health systems fail to provide quality antenatal health services to vulnerable and marginalised pregnant women regardless of their effectiveness in reducing maternal and neonatal mortality. Despite the importance of antenatal care quality during pregnancy, less is known regarding its inequality in developing countries. This paper aims to determine the inequality in antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe and the contribution of women’s empowerment. The paper used the 2010/11 and the 2015 Demographic Health Survey data and concentration index and Shapley decomposition. We found that antenatal care quality was pro-rich for blood sample tests, urine sample tests, blood pressure tests, and iron tablets except for tetanus injections, thus the affluent benefit more from better antenatal care quality than the poor. Women’s empowerment had a major contribution to inequality in antenatal care quality. Given the paramount importance of antenatal care in improving maternal, birth, and child outcomes, policymakers should consider policies that enhance the women’s empowerment and quality of antenatal care services in Zimbabwe, which in turn enhance the attainment of Sustainable Development Goals.

1 Introduction

Despite the importance of antenatal care quality during pregnancy, less is known regarding its inequality in developing countries. Prior studies have focused on the inequality in antenatal care (Hategeka et al., Citation2020; Bobo et al., Citation2021; Morón-Duarte et al., Citation2021; Obse & Ataguba, Citation2021) with few studies (Arsenault et al., Citation2018; Arroyave et al., Citation2021) focusing on the inequality in the quality of antenatal care in developing countries. This limited literature exist despite the fact that inequality in antenatal care quality has adverse effects on maternal, birth, and child health outcomes, hence compromising the realisation of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (Target 3.1, 3.2, and 3.8).Footnote1 Inequalities in child health outcomes can lead to inequalities in education and labour market outcomes, and these inequalities can be intergenerational. It is, therefore, crucial to understand the inequality in antenatal care quality and its predictors in Zimbabwe to enable informed decision-making and help alleviate the inequality that exists in care.

Globally, inequality in antenatal care services exists at a time when maternal mortality is high, with 810 women dying annually during pregnancy and childbirth (WHO, Citation2021). This is despite the SDGs aiming for, at most, 70 women dying per 100,000 live births (WHO, Citation2021). Unfortunately, these women die from preventable and treatable conditions such as complications during pregnancy, and communicable and infectious diseases. Despite an improvement in antenatal care visits, maternal mortality remains high and neonates continue to suffer from low birth weight, and high infant mortality (Sharma et al., Citation2017).

According to WHO (Citation2016), a pregnant woman should have eight antenatal care visits attended by skilled health professionals. However, there are disparities in the quality of antenatal care received along women’s socioeconomic status, distance to the facility, empowerment, and availability of the services (Arsenault et al., Citation2018; Merrell & Blackstone, Citation2020; Arroyave et al., Citation2021; Cesar et al., Citation2021; Asim et al., Citation2022; Lukwa et al., Citation2022). Women’s empowerment through education, access to information, and involvement in decisions making (Melesse, Citation2021) significantly affect antenatal care quality (Anik et al., Citation2021; Asim et al., Citation2022). According to Melesse (Citation2021), women’s empowerment does not only help to reduce economic inequality along gender lines, but also improves maternal and neonatal health outcomes. The more women are empowered, the better the antenatal care services they receive (Merrell & Blackstone, Citation2020). Thus, empowered women have more information on services they are entitled to, and are more likely to demand better quality services than less empowered women (Rani et al., Citation2008; Morón-Duarte et al., Citation2021). Women’s empowerment plays a critical role in improving access to and use of antenatal care services (Ahinkorah et al., Citation2021).

The present paper adds to the existing literature by examining the change in antenatal care quality inequality attributed to women's empowerment in Zimbabwe, a low– to middle-income country ranked among the top 40 countries with high maternal and infant mortality rates (ZSARA, Citation2015; David et al., Citation2021).

1.1. Study context

Zimbabwe, like other WHO member states, recommends pregnant women to have at least eight antenatal care visits, with the first contact in the twelfth week of pregnancy (WHO, Citation2016). To promote access to antenatal care, the Government provides free services in public primary healthcare for pregnant women (World Bank, Citation2019). Antenatal care in Zimbabwe starts with the service provider confirming pregnancy; documenting maternal social, medical, and obstetric history; assessing maternal and fetal condition; identifying and managing risks; and discussing the delivery plan during the first contact (MoHCC, Citation2018; David et al., Citation2021). The preceding seven contacts will be carried out where providers assess maternal and fetal conditions, identify and manage complications, conduct health promotion activities, and review the delivery plan in Zimbabwe (MoHCC, Citation2018).

During each antenatal visit, women receive a package of services comprising urine and blood tests, blood pressure, tetanus injections, and iron tablets (MoHCC, Citation2018; David et al., Citation2021). The most recent estimates show that only 65.3% of the women received blood pressure tests, blood sample tests and urine sample tests before delivery (ZIMSTAT & UNICEF, Citation2019). The ZIMSTAT & UNICEF (Citation2019) also reports that 96.9%, 68.2%, and 98.3% of pregnant women in Zimbabwe had their blood pressure measured, urine samples and blood samples taken, respectively. Concerning the distribution of these services by income level, 98.6% and 83.1% of the affluent women had their blood pressure measured and urine samples taken, respectively, compared to 94.4% and 54.1% of poor women (ZIMSTAT & UNICEF, Citation2019).

While Zimbabwe continues to experience high maternal anaemia, low birth weight, and maternal mortality at 27%, 10%, and 651 deaths per 100 000 live births, respectively, more than eighty percent of pregnant women had at least one antenatal care visit in 2016 (ZIMSTAT & ICF International, Citation2016a). Despite high antenatal care visits, the antenatal care quality received is low and the burden falls heavily on the poor and marginalised women (Lukwa et al., Citation2022). Geographical differences are also evident in Zimbabwe, some provinces have high antenatal care visits compared to others. As indicated in ZIMSTAT & ICF International (Citation2016a), Bulawayo, Matabeleland North and Matabeleland South have the most antenatal care visits while Manicaland, Masvingo and Mashonaland West have the least antenatal care visits.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Data

We used the 2010/11 (ZIMSTAT & ICF International, Citation2011) and the 2015 (ZIMSTAT & ICF International, Citation2016b) Zimbabwe Demographic Health Survey (DHS) data to estimate the inequality in antenatal care quality. The DHS was conducted by the Zimbabwe National Statistical Agency, the Ministry of Health and Child Care, and other non-governmental organisations. The information collected through the DHS is used to monitor international goals like SDGs by assessing child, adolescent and adult health, literacy rate, living standards and access to health care services. In Zimbabwe, there are six DHSs, done across the country’s ten provincesFootnote2 and different types of settlements to ensure national representation. The urban and rural areas within provinces were selected first as strata and households were later allocated to their respective strata using a two-stage sampling method (ZIMSTAT & ICF International, Citation2016a).

Households, men, women, children aged 5–17 and children under five questionnaires were used to collect information. For this analysis, we used a women’s questionnaire which contains information on the utilisation of antenatal care services, and child and maternal health outcomes. Although the data provides the necessary information needed for the analysis, some variables had missing information which reduced the number of observations in the analysis. These variables are antenatal care visits, tetanus injection, urine and blood sample tests, blood pressure tests, women’s empowerment, iron tablets and birth interval. Thus, the data analysis was only possible for over two thousand observations after dropping the missing observations in both years instead of 5 563 and 6 133 women in 2010/11 and 2015, respectively.

Although the latest DHS dataset was conducted in 2015, it is still relevant for this analysis given that the country is still struggling with high maternal and child mortality, low antenatal care services uptake and poor health outcomes. This information, therefore, enables the understanding of the inequalities in antenatal care quality and their contributing factors.

2.2. Variables

Antenatal care quality is defined as the contents of services received during antenatal care visits. Antenatal care services are a package which includes a urine sample test, blood sample test, blood pressure test, tetanus test and iron tablets. The services received during antenatal care are aimed at improving maternal and birth health outcomes. However, not all pregnant women receive these services hence reducing the quality of antenatal care. Following Amo-Adjei et al., (Citation2018) and Arsenault et al. (Citation2018), the paper measured antenatal care quality using the services received during antenatal care visits. These variables are binary representing whether the women received the services or not and a value one was assigned for every antenatal care service received. An antenatal care quality indicator was calculated as a simple index by summing the values of the quality indicators. The indicator ranges between zero, for women who received no antenatal care services (poor quality) and five points, for women who received all antenatal care services (better quality).

Our independent variable of interest was women’s empowerment. Empowerment is a construct including resources, achievement and the ability to engage (Melesse, Citation2021). Empowerment also involves decision-making, freedom to choose, resistance and perception of physical and verbal abuse in society. Following Arroyave et al. (Citation2021), we measured women’s empowerment using the Survey-based Women’s emPowERment (SWPER) index which is based on questions from the survey which define the empowerment of women as shown by the empowerment constructs. These questions include but are not limited to attitude towards abuse, access to information, age at marriage and first child, decision-making in the household, women’s education and the difference between women and husband’s ages (Ewerling et al., Citation2020). The SWPER indicator was observed using three domains: attitude towards violence, based on women’s perspective on husbands beating their wives in different situations; social independence including age at marriage and first birth, access to information, education attainment, and age and education between husband and wife as well as decision making based on decision making in the household and work questions (Ewerling et al., Citation2020). The SWPER index for women’s empowerment was derived through principal component analysis (PCA) with equal weighting considering that all the empowerment domains are equally important. The scores for the overall women’s empowerment index were computed using PCA (see Table C in the Appendix). In that regard, the higher the value of SWPER, the more the women are empowered.

We also controlled for parity (number of children a woman has), urban-rural differences, insurance coverage, birth interval, and distance to the facility. We merged the DHS geographical coordinates and facility coordinates to calculate the distance between the service providers and users in Zimbabwe. This was under the assumption that women in the same cluster use the same facility which is close to them. Although the DHS coordinates were displaced from their original position, it is still possible to have a robust distance calculation. We, therefore, used a 10 km buffer zone to carter for cluster displacement in the DHS data.

2.3. Estimation techniques

2.3.1. Socioeconomic inequality in antenatal care quality

Many methods have been used to estimate inequality in health economics, but concentration indices have recently emerged as the most appropriate method given that they show the distribution in antenatal care quality for different socioeconomic groups. According to O’Donnell et al. (Citation2016), concentration indices are used for econometric analysis given widely available household data. Concentration indices show the distribution of the variable of interest over socioeconomic status (O’Donnell et al., Citation2016). The concentration index was used to investigate the inequality in antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe and measure the extent to which a variable is affecting one group more than the other. The index shows the magnitude and the extent of the distribution of inequality, ranging from a negative one to a positive one (O’Donnell et al., Citation2016). The positive concentration index reflects that affluent women benefit more from antenatal care quality than the poor (pro-rich), and the concentration curve is below the 45-degree line. Moreover, a negative concentration index indicates a pro-poor distribution showing that the poor benefit more from antenatal care quality than the rich. In this case, the concentration curve lies above the 45 degree-line. In addition, the value zero or concentration curve equal to 45 degree-line represents the absence of inequality in antenatal care quality.

The standard concentration index was used to estimate inequality for overall antenatal quality whilst the Erreygers concentration index was used to estimate inequality in antenatal care services (blood pressure test, blood sample test, urine sample test, iron tablets and tetanus injection), which are binary. The Erreygers concentration index is specified as follows:

(1)

(1) where C is the standardised concentration index, μ is the mean of the healthcare variable, and a and b are the upper and lower bounds of the health variable, respectively.

The standard concentration index is specified as follows:

(2)

(2) where C is the standardised concentration index, h is the healthcare variable, and r is the ith-ranked individual in the socioeconomic distribution from the poorest to the richest.

2.3.2. Shapley decomposition

Shapley decomposition was used to estimate the contribution of women’s empowerment to inequality in antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe. As highlighted by Shorrocks (Citation2013), Shapley decomposition estimates the marginal contribution of the independent variables to the inequality in the dependent variable. The decomposition method assumes symmetric variables and the contributions are summed and interpreted as the marginal effects (Azevedo et al., Citation2012; Shorrocks, Citation2013). That is, the decomposition method is path independent unlike other decomposition methods (for example Wagstaff decomposition) used by prior literature (Azevedo et al., Citation2012; Davillas & Jones, Citation2020). A higher coefficient would indicate that women’s empowerment has a big contribution towards antenatal care quality inequality whilst a lower value shows less contribution to inequality. Shapley decomposition is as follows:

is the decomposition of the independent variables,

representing the probability of randomly selecting a subset S among different subsets with equal likelihood.

denote a set of contributory factors in the analysis (women’s empowerment, distance to the facility, health insurance, birth interval, urban-rural differences and parity).

3. Results

The results section reports the descriptive statistics first, followed by the antenatal care services received by different socioeconomic groups during pregnancy. The concentration indices are also depicted in this section as well as the Shapley decomposition results on the contribution of women’s empowerment to antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe.

summarises the descriptive statistics for 2015 and 2010/11 DHS. The table shows the averages of socio-demographic variables and antenatal care quality over the years in Zimbabwe.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics.

On average, women in the 2015 survey were older than those in 2010/11. A large proportion of women had secondary education in Zimbabwe, thus women with at least secondary education were more than those with primary education or none. The proportion of educated women increased from 2010/11–2015. The proportion of married women was also higher than those who have never married or formerly married in the survey. Most women get married around nineteen or eighteen years. Rural women represented a larger share of the population, than in urban areas. However, the proportion was decreasing over time as more and more women were residing in the urban areas. The average number of children slightly changed over time in Zimbabwe.

More women attended antenatal care and the proportion was increasing over the years. The average proportion of women receiving antenatal care services in Zimbabwe increased from 2010/11–2015. A considerable proportion of women received their blood pressure test, tetanus injection, iron tablets, and blood sample test in both 2010/11 and 2015. However, although the proportion of women with tests taken was above fifty percent, much needs to be done to improve antenatal care quality. Of all the antenatal care services received during pregnancy, fewer women received the required number of tetanus injections.

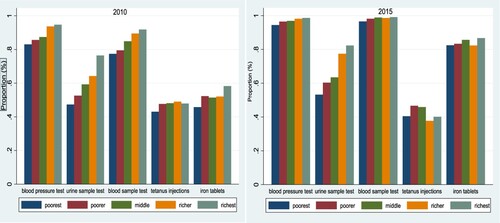

shows the proportion of women who received different antenatal care services by wealth index in Zimbabwe between 2010 and 2015. The services include blood pressure tests, urine sample tests, blood sample tests, tetanus injections and iron tablets during pregnancy. A high proportion of pregnant women received different antenatal care services in both 2010/11 and 2015. Almost all the services were positively skewed towards the affluent for 2010 and 2015 except for tetanus which does not show a distinct pattern. The affluent receive high-quality services in almost all services compared to the poor in Zimbabwe. Thus, antenatal care follows a socioeconomic gradient in the country whereby the poor receive low-quality services compared to the affluent. This shows that inequality in antenatal care quality still exists in Zimbabwe. In 2010, fewer women received tetanus injections and iron tablets. The proportion of women receiving iron tablets, therefore, increased in 2015, with a slight decrease for those receiving tetanus injections.

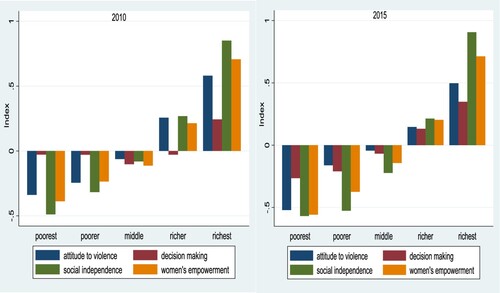

shows women’s empowerment in Zimbabwe between 2010 and 2015. This was illustrated in terms of three empowerment domains; attitude towards violence, decision making and social independence over time. Women’s empowerment was low for poor women as compared to affluent women for all the women’s empowerment domains. The more affluent the women, the more empowered they are. However, poor women are less empowered in 2015 compared to 2010 in attitude toward violence, decision making and social independence in Zimbabwe.

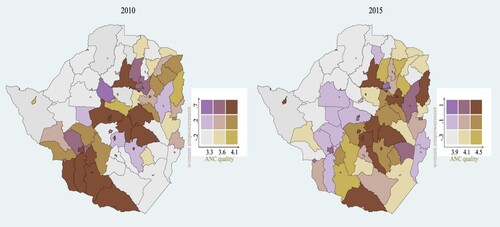

illustrates the spatial association between women’s empowerment and antenatal care quality over years. This shows that spatial inequality in antenatal care quality and women’s empowerment exists in Zimbabwe. The northern, northwest and southeast parts of the country have less antenatal care quality and empowerment whilst central and southwest have high antenatal care quality and women’s empowerment. However, some districts in the central and northeast parts of the country have low women’s empowerment regardless of the better-quality antenatal care quality over time.

shows the concentration indices for antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe between 2010/11 and 2015. The results illustrate concentration indices for separate antenatal care services, that is, blood pressure test, urine sample test, blood sample test, tetanus injection, iron tablets and the overall antenatal care quality. Positive and significant concentration index values in receiving blood pressure tests in 2010/11 and 2015 suggest that blood pressure was disproportionately concentrated among the affluent. This means that blood pressure measurement services for pregnant women was pro-rich in Zimbabwe. The results also indicated significant pro-rich urine sample tests and blood sample tests during antenatal care. Tetanus injection during pregnancy had a significant and positive value for 2010/11, and a significant negative value for 2015. This indicates that tetanus injections benefitted the affluent more than the poor in 2010/11, and more for the poor than the affluent in 2015. Iron tablets had a significant and positive concentration index in 2010.

Table 2. Concentration indices for antenatal quality in Zimbabwe.

Overall, antenatal care quality had a positive and significant value in 2010/11 and 2015, 0.041 and 0.011, respectively. Thus, the results indicated a pro-rich antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe between 2010 and 2015. This means that affluent women benefited more from better quality antenatal care compared to their poor counterparts over the period 2010/11 and 2015.

indicates the Shapley decomposition results for inequality in antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe. The results, therefore, show the contribution of women’s empowerment, parity, insurance, birth interval, location and distance to the health facility to inequality in antenatal care quality in 2010/11 and 2015. The results show that women’s empowerment contributed the most to the inequality in antenatal care quality in both 2010/11 (34.35%) and 2015 (41.42%). In 2010/11, urban areas contributed substantially (30.32%) to the inequality in antenatal care quality. This was followed by birth interval and distance to the facility (13.28% and 11.22%, respectively). In 2015, distance (17.92%) was the second largest contributor to inequality in antenatal care quality, followed by birth interval (17.22%). The contribution of insurance to antenatal care quality inequality increased from 10.05% in 2010/11 to 14.11% in 2015. Parity was the least contributor to antenatal care quality inequality in both 2010/11 (0.79%) and 2015 (3.55%).

Table 3. Shapley decomposition of inequality in antenatal care quality.

Table B under the appendices shows the results of the ordinary least square which was used to support the results on shapely decomposition. Women’s empowerment is positively associated with antenatal care quality as indicated in Table B.

4. Discussion

Antenatal care services are crucial in improving maternal and birth outcomes during and after pregnancy. Pregnant women are entitled to at least four antenatal care visits to receive different antenatal care services comprising of blood pressure tests, urine sample tests, blood sample tests, tetanus injections as well as iron tablets. Despite the increase in antenatal care visits, pregnant women still receive fewer services during these services hence poor-quality antenatal care services (Arroyave et al., Citation2021). There is a socioeconomic disparity in antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe, where the poor living in rural areas are more likely to have access to inferior quality antenatal care services as compared to the affluent living in urban areas. This might hamper Zimbabwe’s progress towards achieving her goals of Vision 2030 and attaining SDG 3. Given the paramount importance of antenatal care in improving maternal, child and birth outcomes, policymakers should, therefore, consider policies that enhance the quality of antenatal care services in Zimbabwe.

We found a pro-rich concentration index for all the antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe, except tetanus in 2015. On average, antenatal care quality was skewed towards affluent women. That is, affluent women were benefiting more from better antenatal care quality at the expense of their poor counterparts, although the poor tend to be vulnerable and require more services than the affluent do. The results are in line with Arsenault et al. (Citation2018), Amo-Adjei et al. (Citation2018) and Bobo et al. (Citation2021) findings which noted that the affluent tend to benefit from decent quality services compared to the poor. Given that the affluent groups are more likely to have more antenatal care visits than recommended (Bobo et al., Citation2021; Cesar et al., Citation2021; Obse & Ataguba, Citation2021), they are more likely to receive all or most of the antenatal care services as compared to the poor with less antenatal care visits. The affluent are more likely to be educated, have autonomy in decision-making, and they don’t tolerate violence, which are all associated with better health-seeking behaviour. Moreover, women from high socioeconomic groups reside in areas with better resources in terms of infrastructure hence they tend to have access to well-resourced facilities.

Infrastructure in resource-constrained environments tends to be rudimentary therefore interfering with the quality of care received. The geospatial distribution of antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe confirms this. The north and northwest regions of Zimbabwe are the remotest (for example Binga) (MoHCC, Citation2020) and tend to suffer the most from inferior antenatal care quality. The facilities in these areas tend to be far from the households, therefore, reducing access to the services and the antenatal care quality received during pregnancy (Osika et al., Citation2010; Dube et al., Citation2019). As indicated in ZIMSTAT & ICF International (Citation2016a), women from the northwest and the northern parts (Matabeleland North and Mashonaland West) have less decision-making on healthcare and household purchases and tolerate wife beating. In addition, these areas have a high prevalence of women married at a young age compared to other areas in the country (ZIMSTAT & ICF International, Citation2016a). Women in affluent areas tend to be educated and reside in urban areas, which implies increased use of antenatal care services compared to the poor, less-educated and rural population (Arsenault et al., Citation2018; Arroyave et al., Citation2021).

Women’s empowerment contributes significantly towards inequality in antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe. Empowered women are likely to influence the inequality in antenatal care quality as compared to the less empowered. Women’s empowerment in the form of gendered beliefs about violence, decision-making and social independence have an independent positive association with the utilisation of quality antenatal care (Anik et al., Citation2021; Asim et al., Citation2022; Merrell & Blackstone, Citation2020). Women with decision-making power have autonomy for mobility to visit the healthcare facility for antenatal care without first consulting their husbands (Anik et al., Citation2021; Asim et al., Citation2022). Moreover, socially independent women are financially capable of accessing essential healthcare services and they know the value of the services they are supposed to receive (Asim et al., Citation2022). This knowledge enables them to express themselves to the healthcare providers, hence receiving better quality services than received by socially dependent women. Women’s empowerment is important in reducing gender inequality and improving economic performance (Melesse, Citation2021). In that regard, women’s empowerment is a stepping stone to improving the utilisation of better antenatal health care services.

Other factors like parity, birth interval, distance to the closest facility, geographical location and health insurance coverage contributed to inequality in antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe. These variables contributed a considerable share of the inequality in antenatal care quality. Thus, controlling for these variables is crucial to improve the use of better-quality antenatal care services by women during pregnancy in Zimbabwe.

This study is not without limitations. The study used self-reported antenatal care services utilisation data, based on recalls, as a measure of antenatal care quality. Whilst self-reported data on antenatal care services can give a better understanding of antenatal care in Zimbabwe, we cannot rule out biased results emanating from unobserved heterogeneity. The recall bias may have resulted in underreporting or overreporting of the use of antenatal care services, which can result in over or underestimating the inequality. We also used repeated cross-sectional data which makes our results limited to specific time points analysed. The results might be affected by omitted variable bias considering that there might be other variables affecting antenatal care quality not included in the model. Further studies might use recent data to check if antenatal care quality inequality has improved or decreased in Zimbabwe. In addition, future studies can establish the impact of empowerment on antenatal care quality using longitudinal data, which was not possible using the DHS data available at the time of the study.

Although analyses of survey data that measure inequality using self-reports can rarely be spared such criticism, the strengths of the present study emanate from the size and type of data. We used more than 2 000 observations, drawn from the nationally representative data set, which provided a unique opportunity to carry out the study in a low – to medium-income country with poor maternal and child health.

5. Conclusion

Although antenatal care visits have increased in most developing countries, antenatal care quality remains compromised. This has negative effects on maternal, birth and child health outcomes hence straining the realisation of global health goals. Improving access to quality healthcare services for vulnerable groups is part of the global health goals. The paper noted that inequality in antenatal care quality exists in Zimbabwe where women in higher socioeconomic groups benefit more from better quality services than lower socioeconomic groups. Affluent women have benefited from quality services over the years in all the services. Women’s empowerment contributed to a considerable share of inequality in antenatal care quality in Zimbabwe. To address the demand side of antenatal care quality, there is a need to improve women’s empowerment (attitude to violence, decision making and social independence) through education and awareness campaigns to mention a few. There is also a need for country-specific and homegrown policies to improve the quality of care in Zimbabwe. Thus, we recommend that policymakers focus on improving antenatal care quality during pregnancy to restore/and improve trust in the formal health system. This can be done by improving maternal health education through community healthcare workers, short message services or phone calls for reminders and peer-to-peer support groups for pregnant women as well as awareness campaigns against child marriages and domestic violence. Improving maternal and child health outcomes through better antenatal care quality enhances the attainment of Vision 2030.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Data availability

The DHS data used for analysis is publicly available at https://dhsprogram.com/data/available-datasets.cfm.

Notes

1 Target 3.1 states that ‘By 2030, reduce the global maternal mortality ratio to less than 70 per 100,000 live births’; Target 3.2 notes that ‘By 2030, end preventable deaths of newborns and children under 5 years of age, with all countries aiming to reduce neonatal mortality to at least as low as 12 per 1,000 live births and under-5 mortality to at least as low as 25 per 1,000 live births’. Target 3.8 aims to ‘Achieve universal health coverage, including financial risk protection, access to quality essential health-care services and access to safe, effective, quality, and affordable essential medicines and vaccines for all’ (United Nations, Citation2022).

2 The ten provinces are Bulawayo, Harare, Manicaland, Mashonaland Central, Mashonaland East, Mashonaland West, Masvingo, Matabeleland North, Matabeleland South and Midlands.

References

- Ahinkorah, BO, Ameyaw, EK, Seidu, AA, Odusina, EK, Keetile, M & Yaya, S, 2021. Examining barriers to healthcare access and utilization of antenatal care services: Evidence from demographic health surveys in sub-Saharan Africa. BMC Health Services Research 21(1), 1–16. doi:10.1186/s12913-021-06129-5

- Amo-Adjei, J, Aduo-Adjei, K, Opoku-Nyamah, C & Izugbara, C, 2018. Analysis of socioeconomic differences in the quality of antenatal services in low and middle-income countries (LMICs). PLoS One 13(2), e0192513–12. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0192513

- Anik, AI, Islam, MR & Rahman, MS, 2021. Do women’s empowerment and socioeconomic status predict the adequacy of antenatal care? A cross-sectional study in five South Asian countries. BMJ Open 11(6), 1–8. doi:10.1136/bmjopen-2020-043940

- Arroyave, L, Saad, GE, Victora, CG & Barros, AJD, 2021. Inequalities in antenatal care coverage and quality: An analysis from 63 low and middle-income countries using the ANCq content-qualified coverage indicator. International Journal for Equity in Health 20(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/s12939-021-01440-3

- Arsenault, C, Jordan, K, Lee, D, Dinsa, G, Manzi, F, Marchant, T & Kruk, ME, 2018. Equity in antenatal care quality: An analysis of 91 national household surveys. The Lancet Global Health 6(11), e1186–e1195. doi:10.1016/S2214-109X(18)30389-9

- Asim, M, Hameed, W & Saleem, S, 2022. Do empowered women receive better quality antenatal care in Pakistan? An analysis of demographic and health survey data. PLoS One 17(1 January), 1–13. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0262323

- Azevedo, PJ, Sanfelice, V & Nguyen, CM, 2012. Shapley decomposition by components of a welfare aggregate. (85584). Available: https://mpra.ub.uni-muenchen.de/85584/1/MPRA_paper_85584.pdf.

- Bobo, FT, Asante, A, Woldie, M, Dawson, A & Hayen, A, 2021. Spatial patterns and inequalities in skilled birth attendance and caesarean delivery in sub-Saharan Africa. BMJ Global Health 6(10), 1–10. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2021-007074

- Bobo, FT, Asante, A, Woldie, M & Hayen, A, 2021. Poor coverage and quality for poor women: Inequalities in quality antenatal care in nine East African countries. Health Policy and Planning 36(5), 662–72. doi:10.1093/heapol/czaa192

- Cesar, JA, Black, RE & Buffarini, R, 2021. Antenatal care in Southern Brazil: Coverage, trends and inequalities. Preventive Medicine 145(August 2020), 106432. doi:10.1016/j.ypmed.2021.106432

- David, R, Evans, R & Fraser, HSF, 2021. Modelling prenatal care pathways at a central hospital in Zimbabwe. Health Services Insights 14, doi:10.1177/11786329211062742

- Davillas, A & Jones, AM, 2020. Ex ante inequality of opportunity in health, decomposition and distributional analysis of biomarkers. Journal of Health Economics 69, 102251. doi:10.1016/j.jhealeco.2019.102251

- Dube, B, Mberikunashe, J, Dhliwayo, P, Tangwena, A, Shambira, G, Chimusoro, A, Madinga, M & Gambinga, B, 2019. A social network analysis on immigrants and refugees access to services in the malaria elimination context. Malaria Journal 18(1), 1–10. doi:10.1186/s12936-018-2635-4

- Ewerling, F, Raj, A, Victora, CG, Coll, CVN & Barros, AJD, 2020. SWPER global : A survey-based women’s empowerment index expanded from Africa to all low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Global Health 10(2), doi:10.7189/jogh.10.020434

- Ewerling, F, Raj, A, Victora, CG, Hellwig, F, Coll, CV & Barros, AJ, 2020. SWPER Global: A survey-based women’s empowerment index expanded from Africa to all low- and middle-income countries. Journal of Global Health 10(2), doi:10.7189/JOGH.10.020434

- Hategeka, C, Arsenault, C & Kruk, ME, 2020. Temporal trends in coverage, quality and equity of maternal and child health services in Rwanda, 2000–2015. BMJ Global Health 5(11), e002768–10. doi:10.1136/bmjgh-2020-002768

- Lukwa, AT, Siya, A, Odunitan-Wayas, FA & Alaba, O, 2022. Decomposing maternal socioeconomic inequalities in Zimbabwe; leaving no woman behind. BMC Pregnancy and Childbirth 22(1), 1–17. doi:10.1186/s12884-022-04571-9

- Melesse, MB, 2021. The effect of women’s nutrition knowledge and empowerment on child nutrition outcomes in rural Ethiopia. Agricultural Economics 52(6), 883–99. doi:10.1111/agec.12668

- Merrell, LK & Blackstone, SR, 2020. Women’s empowerment as a mitigating factor for improved antenatal care quality despite impact of 2014 ebola outbreak in Guinea. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health 17(21), 8172–18. doi:10.3390/ijerph17218172

- MoHCC, 2018. Zimbabwe antenatal care protocol, Ministry of Health and Child Care, Harare, Zimbabwe. https://platform.who.int/docs/default-source/mca-documents/policy-documents/guideline/ZWE-MN-21-01-GUIDELINE-2018-eng-ANC-Protocol-Poster.pdf

- MoHCC, 2020. National malaria control and elimination strategic plan: 2021–2025. National Malaria Control Programme, Harare, Zimbabwe.

- Morón-Duarte, LS, Varela, AR, Bertoldi, AD, Domingues, MR, Wehrmeister, FC & Silveira, MF, 2021. Evidence that collaborative action between local health departments and nonprofit hospitals helps foster healthy behaviors in communities: A multilevel study. BMC Health Services Research 21(1), 1–14. doi:10.1186/s12913-020-05996-8

- Obse, AG & Ataguba, JE, 2021. Explaining socioeconomic disparities and gaps in the use of antenatal care services in 36 countries in sub-Saharan Africa. Health Policy and Planning 36(5), 651–61. doi:10.1093/heapol/czab036

- O’Donnell, O, O’Neill, S, Van Ourti, T & Walsh, B, 2016. Conindex: Estimation of concentration indices. The Stata Journal: Promoting Communications on Statistics and Stata 16(1), 112–38. doi:10.1177/1536867(1601600112

- Osika, J, Altman, D, Ekbladh, L, Katz, I, Nguyen, H, Rosenfeld, J, Williamson, T & Tapera, S, 2010. Zimbabwe health system assessment 2010. Health Systems 20/20 Project, Abt Associates Inc, Bethesda, MD.

- Rani, M, Bonu, S & Harvey, S, 2008. Differentials in the quality of antenatal care in India. International Journal for Quality in Health Care 20(1), 62–71. doi:10.1093/intqhc/mzm052

- Sharma, J, Leslie, HH, Kundu, F & Kruk, ME, 2017. Poor quality for poor women? Inequities in the quality of antenatal and delivery care in Kenya. PLoS One 12(1), 1–14. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0171236

- Shorrocks, AF, 2013. Decomposition procedures for distributional analysis: A unified framework based on the Shapley value. The Journal of Economic Inequality 11(1), 99–126. doi:10.1007/s10888-011-9214-z

- United Nations, 2022. Department of economic and social affairs: sustainable development. Available: https://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal3%0Ahttps://sdgs.un.org/goals/goal16 [2022, July 14].

- WHO, 2016. WHO recommendations on antenatal care for a positive pregnancy experience, World Health Organization, Geneva, Switzerland. https://iris.who.int/bitstream/handle/10665/250796/9789241549912-eng.pdf?sequence=1

- WHO, 2021. New global targets to prevent maternal deaths. Available: https://www.who.int/news/item/05-10-2021-new-global-targets-to-prevent-maternal-deaths [2022, February 20].

- World Bank, 2019. Improving access to maternal health for Zimbabwe’s expectant mothers. Available: https://www.worldbank.org/en/news/feature/2019/01/10/improving-access-to-maternal-health-for-zimbabwes-expectant-mothers [2024, March 30].

- Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and UNICEF, 2019. Zimbabwe multiple indicator cluster survey 2019, survey findings report, ZIMSTAT and UNICEF, Harare, Zimbabwe. https://www.unicef.org/zimbabwe/reports/zimbabwe-2019-mics-survey-findings-report

- ZIMSTAT and ICF International, 2011. Zimbabwe demographic health survey 2010/11 [dataset]. ZWKR62FL.DTA. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- ZIMSTAT and ICF International, 2016a. Zimbabwe demographic health survey 2015: Final report. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- ZIMSTAT and ICF International, 2016b. Zimbabwe demographic health survey 2015 [dataset]. ZWKR72FL.DTA. Zimbabwe National Statistics Agency (ZIMSTAT) and ICF International, Rockville, Maryland, USA.

- ZSARA, 2015. Zimbabwe service availability and readiness assessment report, Ministry of Health and Child Care, Harare, Zimbabwe. Available: http://ncuwash.org/newfour/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Zimbabwe-Service-Availability-and-Readiness-Assessment-Report.pdf%0Ahttp://ncuwash.org/newfour/wp-content/uploads/2017/08/Zimbabwe-Service-Availability-and-Readiness-Assessment-Report.pdf%0Ahttp://apps.