ABSTRACT

This article reports on data generated from focus groups held with primary and secondary school students in which they were asked about experiences of grammar teaching and testing in the context of post-2010 reforms in England. Data from these focus groups were triangulated with a bricolage of other data, including fieldnotes, teacher surveys, pedagogical materials and government-produced policy documents. Our findings show that, in spite of differences within primary-secondary policy, students’ perceptions of their experiences had significant elements of commonality. Students’ conceptualisations of grammar were focused on word and clause-level notions, generally rejecting the idea that grammar was associated with meaning, creativity and choice. Students emphasised experiences of decontextualised grammar teaching, despite evidence from their teachers which espoused contextualised grammar. Finally, the state-issued primary school grammar tests were found to be working as a powerful de facto language policy, warping and distorting students’ memories and experiences of grammar.

Introduction and aims

This article traces the ways that experiences of grammar teaching and testing get perceived and recalled by primary and secondary school students in England. It uses data from focus groups generated from the final year of primary education (Year 6; 10–11 year olds) and the first year of secondary education (Year 7; 11–12 year olds). Our focus is on grammar because it was one of the major changes made in post-2010 curriculum and assessment reforms, as well as attracting significant academic interest (e.g. Bell Citation2015; Cushing Citation2019; Harris & Helks Citation2018; Safford Citation2016). Previous research has shown how grammar policy across primary–secondary school is incongruous (Cushing Citation2019), with schools being presented with an inconsistent message about grammar ideologies, pedagogies and assessments. In brief, grammar policy at primary school is geared towards decontextualised grammar pedagogies, whilst at secondary school, policy is geared towards contextualised pedagogies. Decontextualised grammar is typically associated with labelling grammatical constructions at word/clause-level, “accuracy” of usage in writing and identifying “rules” in artificial examples, whereas contextualised grammar is orientated towards “choices”, drawing links between grammar, discourse and meaning through examples, authentic texts and classroom discussion (e.g. Myhill Citation2018).

Given that pedagogies are informed and influenced by policies, this article explores students’ experiences of these pedagogies, drawing primarily on data gleaned from student focus groups to explore what we will call the “policy-pedagogy trajectory” – i.e. the ways in which policy mechanisms come to be transformed into pedagogies. We use “experience” to denote the ways that humans represent their subjective, social experiences and how this shapes memories, perceptions, knowledge and feelings. Our focus group data are triangulated with a bricolage of additional data, including government policy documents, Ofsted reports, school-produced literacy policies, pedagogical materials, conversations with teachers and our own fieldnotes. Our research was motivated by the absence of students’ voices in the existing literature on grammar in England’s schools (e.g. Bell Citation2016; Safford Citation2016) and indeed, in language education research more broadly (e.g. Rudduck Citation1999; Carter Citation1990). The research questions we set out to answer are:

1. What are primary and secondary school students’ experiences of grammar teaching and testing?

2. To what extent do these experiences reflect the way that grammar is conceptualised within primary and secondary education policy discourse and in the local context of the school?

In exploring these, we look to draw contact points between language policy and pedagogy and perceptions, whilst highlighting students’ voices and ideas. Although we reject the notion that the policy-pedagogy trajectory is a linear one, we also suggest that in an educational context characterised by power imbalances, top-down surveillance and mandated “standards”, teachers and students are almost always positioned as less-powerful actors in the policy process. At the very “end” of this trajectory is the student in the classroom who experiences pedagogies, and typically has very little agency in terms of how policy gets transformed into material actions. In reference to current grammar policy in English education, work on students’ experiences is under-developed, with previous work tending to focus on the perceptions made by teachers. We attend to this gap in knowledge, answering calls by Bell (Citation2016, 161), for example, in addressing the “ways in which children themselves perceive this element of their education”. We also consider the trajectory metaphor to be an important way of examining different educational spaces, such as the differences between primary and secondary school, and the transition between these. In the context of this study, the pedagogies teachers choose to enact are of particular importance: although our teachers were working within the constraints of a national curriculum, they nevertheless made their own classroom decisions in terms of approaches and espoused beliefs about grammar teaching.

Grammar policy mechanisms in England’s schools

One characteristic of post-2010 education reforms in England is the (re)emphasis on grammar, both within the national curricula for primary and secondary, and in national assessments at the end of Key Stage 1 (6–7 years old), Key Stage 2 (10–11 years old) and Key Stage 4 (15–16 years old). As has long been the case in c/Conservative education policy, grammar teaching and testing was used by government as one key driver of this ideology, with ministers declaring the need for students to use language “properly”, part of which included a push for decontextualised grammar teaching and testing (Gove Citation2013a). These language ideologies were transformed into policies through concrete mechanisms such as the KS2 Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling (GPS) tests (STA Citation2015); the new National Curriculum for primary and secondary (DfE Citation2013a, Citation2013b) with an appendix of grammatical concepts to be introduced year-by-year (DfE Citation2013a, 64–69), an extensive grammar glossary (DfE Citation2013a: 70–88, Citation2013b, 14), and the Teachers’ Standards (DfE Citation2013c). Cushing (Citation2021) outlines how this cluster of mechanisms work to construct schools as places of “standard language cultures” (Milroy Citation2001), where the perpetuation of the “correct/incorrect” myth gets further entrenched and (re)produced. An important policy mechanism that sits across primary–secondary is the grammar glossary (DfE Citation2013a, 80–98), framed not as a body of knowledge for students to learn but as a “guide” for teachers. At primary level, teachers are presented with glossary terms in the form of a year-by-year “statutory requirement” which prescribes the grammatical concepts to be introduced each year (DfE Citation2013a, 75–79). There is no such detailed “guidance” for secondary school teachers.

A further notable mechanism is the GPS assessments, part of an assemblage of Standardised Assessment Tests (SATs). The GPS tests are characterised by decontextualised grammar, with questions requiring students to “identify”, “correct”, “match” or “explain” linguistic terminology and grammatical constructions. Questions place an exclusive emphasis on word/clause-level grammar and knowledge of standardised English, leaving no opportunity to explore the social dimension of language (e.g. Cushing Citation2020a; Safford Citation2016). Rather than providing another critique of the tests themselves, our focus here is on the consequences of testing in terms of students’ experiences of primary education. Tests are a powerful influencer in determining what content is taught in school, how it is taught, who teaches it, and what kind of messages about language are perpetuated. For example, Braun and Maguire (Citation2018), Moss (Citation2009) and Carter (Citation2020) all explore how the assessment agenda in England can be seen as a tool for policy compliance and accountability, looking in particular at policy moves such as the National Literacy Strategy and the phonics screening check. The GPS tests are de facto language policies, working as policy mechanisms that have the potential to warp and distort pedagogies and curricula (see Cushing Citation2020a). However, absent from the existing literature on current grammar policy mechanisms in schools is the student voice and their experiences of these mechanisms, which this article attends to.

Methodology and data

Our methods were driven by the motivation to generate data which highlighted students’ voices and perspectives, in seeking to understanding their experiences in terms of grammar teaching and testing. To do this, we ran focus groups in four co-educational, state-maintained schools: two primary (Year 6) and two secondary (Year 7), in two English cities. There were 5–8 students in each group, taken from a mixture of classes with a range of attainment levels. Students in the secondary group had all been to different primary schools, and so we were confident that the participants represented a diverse experience of grammar teaching at primary, but a shared experience at secondary. Together, our sample of participants represent the first cohort to have experienced the whole of the GPS agenda since its introduction in 2013–14. Contact teachers at each school were responsible for organising the groups, and they sat in on the focus groups, which lasted around 60 minutes. Informal conversations with each contact teacher post-focus group enabled us to reflect on the students’ views. We also collected language policy artefacts from each school (such as literacy policies and curriculum overviews for English), Ofsted reports for each school, and a survey completed by each of the contact teachers about their own pedagogical approach/policies for the teaching of grammar. This was important in eliciting information about the pedagogical culture of each school and helped to ensure that our analysis was contextualised and situated within their local context (see Braun et al. Citation2011). Ethical approval was granted by Cushing’s institution and all students signed consent forms.

Focus groups were chosen rather than individual interviews to mitigate against issues of power imbalance, such as students potentially feeling shy, anxious and uncomfortable in speaking to people they were unfamiliar with. We tried hard to create a space where their own perceptions, realities, memories and reflections were foregrounded (Vasquez Citation2014) and felt this was particularly important given the high-stakes nature of some aspects of grammar (most notably the GPS tests), and the pressures these are known to inflict upon young people (e.g. Putwain et al. Citation2012). We asked for specific accounts, memories and moments in order to understand the “social life” of grammar teaching and testing. We also used an initial card sorting activity whereby students were presented with individual cards each with a different linguistic term printed on. These were spelling, punctuation, adjective, creativity, subordinate clause, rules, meaning, adverbial, noun and choice. Students used these cards to explore initial questions, such as by discussing which terms they felt were particularly dis/associated with “grammar” and which concepts they felt were particularly prevalent/absent in their lessons.

Focus groups were audio recorded and then professionally transcribed. We closely read the transcripts in order to immerse ourselves in the data, and independently drew up some emerging themes before collaboratively developing a coding framework over a number of months. To help make sense of the data, we used Braun and Clarke’s (Citation2006) six-stage approach to thematic analysis: familiarising; initial code generation; searching for themes; reviewing themes; defining and naming themes; and reporting. The analysis that follows is organised around three of the most prominent codes that came out of this exercise across both Y6 and Y7 data: conceptualisations of grammar; perceptions of grammar pedagogies, and lasting effects of assessments.

Conceptualisations of grammar

This section examines the ways that students talked about grammar, and how this reflected language discourses found within national policy and the local context of their schools. Data revealed that students in both Y6 and Y7 generally held word and clause-level schemata for grammar, primarily driven by word classes, phrases, clauses and their associated grammatical metalanguage. This is perhaps to be expected, given that students’ experiences of grammar had been shaped by a government grammar policy which itself is fairly restricted to word and clause-level work. For example, in discussing how they would define “grammar” and the kinds of activities they would normally do in grammar lessons, Y6 students responded with “clauses and phrases” and how they learn about “different types of words when you’re doing grammar” such as using “this type of subordinate clause or this type of conjunction”. Y7 students suggested that grammar was “the rules to structure a sentence properly”, “adverbs and adjectives and verbs”, and “different types of terminology that you might not know”. Indeed, the amount of grammatical terminology that students felt they “had to know” was clearly something that formed a large part of their own schemata for grammar. Unsurprisingly, the kind of grammatical terminology that students referenced was directly from the National Curriculum (DfE Citation2013a, Citation2013b) and the grammar glossary (e.g. DfE Citation2013a, 70–88). This body of terminology aligns with traditional, prescriptive grammar, reflecting what the writer of the glossary describes as a “rather conservative position” and a preference for “traditional distinction” (Hudson Citation2016; see Cushing Citation2020b for a critique of Hudson’s position).

Conversely, there was clear resistance to the idea that linguistic concepts at what might be called “discourse-level” – such as “meaning”, “creativity” and “choice” – were part of grammar. This was evident in the card sorting activity where the notion of “meaning” and grammar was related to, as one Y6 student said, “making sentences makes sense”. Standard language ideologies of “rules” and “correctness” were wrapped up in these discussions – one Y7 student, for example, talked about grammar as about “speaking properly and using language like properly […] you know using good grammar […] you have to use correct grammar”. This ideology could be traced back to the student’s school curriculum overview, which stated that a central aim was for students to “use correct grammar and Standard English at all times in the school”, something which had been praised by Ofsted in their most recent report of the school, in how staff were “consistently correcting” students’ spoken language.

Focus groups also revealed a lack of association between “creativity” and grammar. We were interested in this relationship given its importance within the principles of contextualised grammar pedagogies (e.g. Myhill Citation2018) and the fact that the word “create” (or any of its derivatives) appears just twice in the main text of the primary curriculum and not a single time in the secondary curriculum. One of the uses of “creativity” is found in the preamble to the grammar glossary (DfE Citation2013a, 5), where the teaching of grammar, punctuation and spelling is framed as something which is “not intended to constrain or restrict teachers’ creativity, but simply to provide the structure on which they can construct exciting lessons”. Despite evidence from the teachers we worked with that they were indeed attempting to teach “exciting lessons”, some of the focus group data were in opposition to this. For example:

In my opinion grammar and creativity are opposites. Grammar is quite boring; creativity is just everything makes it a lot more interesting. Grammar is basic. Grammar isn’t anything to with creativity. It’s not being creative when we’re doing grammar because how can it be? It’s all about rules. Getting language right is not being creative.

This was supported by other students from across the four focus groups. Even when “adjectives” and “adverbs” were presented by some Y7 students as patterns that might enhance creative writing, they were seen as having an additive function (see Barrs Citation2019), to be crudely “inserted” in order to “make writing better”. We return to this “writing by numbers” discourse later.

For the Year 6 students, the concept of “choice” in grammar was almost entirely associated with “multiple choice in tests”, this being the predominant question type within the GPS tests. “Choice” here was about constraints as opposed to opportunities – for instance: “you don’t always have your choice in some questions, you have to follow what it says to do”. Although choice in grammar was not framed so exclusively by the tests by students in Y7, the notion of restricted choice was still evident. For example:

‘Choice’ is like, grammar is either sometimes you get it right or you get it wrong; there’s no choice. You can’t choose another word like you can’t choose like not to add a noun, you can’t choose to not add punctuation. It’s like you have to do it in order for it to be an actual sentence.

However, within national policy documents, the relationship between “choice” and “grammar” appears to be more aligned with the principles of contextualised grammar – for instance in “understanding how such choices can change and enhance meaning” (DfE Citation2013a, 37) and using grammatical knowledge to allow for “more conscious control and choice in our language” (DfE Citation2013a: 64, our emphases; see also Myhill et al. Citation2013). Despite this, students’ perceptions aligned more closely with the traditional framing of grammar found within the glossary and GPS tests, suggesting that these materials are afforded greater prominence as part of actual classroom practice. Indeed, many students conflated “grammar” with punctuation and spelling, mirroring the packaging together of these concepts within the GPS tests. Students’ reported lack of association between grammar, meaning, choice and creativity was particularly concerning as all four teachers in our study expressed a clear understanding and strong commitment to teaching grammar in contextualised ways. For instance, one Y6 teacher stated that she provides “opportunities to focus on grammatical structures in context within sessions and explore the meaning of language through understanding of the text”. A further discussion of this is provided in the following section.

Perceptions of pedagogies

This section explores students’ reporting of their own experiences of grammar teaching. In general, these reflected a higher degree of decontextualised grammar than contextualised grammar, with an emphasis on discrete grammar lessons which were “separate” from other aspects of English, characterised in part by activities such as “identifying” grammatical features and terminology, often in the context of test preparation. Whilst this was not the exclusive experience of students, it was certainly the more dominant discourse – for instance, in calling up their own experiences of grammar in the classroom, students said that grammar is “like revision for our tests”, “putting in all the subordinate clauses”, using a “checklist” and whether punctuation was “needed or not needed”.

This is especially significant when considered alongside the data generated from our Y6 teachers, which suggested that both teachers were wholly committed to teaching grammar contextually. For example:

Grammar is taught contextually as part of a ‘reading into writing process’. We use key texts as the basis for our literacy teaching, primarily drawing on the Power of Reading approach. In the build up to extended pieces of writing, we teach aspects of grammar, language and vocabulary which are relevant to the writing genre and draw from the authentic examples in the key text.

These principles were illustrated with an example of a grammar lesson that the second Y6 teacher provided, where students were asked to explore an author’s grammatical choices in the class text and then engage in textual transformation work where subtle alterations resulted in new meanings and effects. Although there was a clear acknowledgement of some “discrete teaching in addition to this approach and in preparation for the SATs”, this was not seen as something divorced from the other contextualised practices of the classroom. As one Y6 teacher said:

There are times when I support children in being able to face a grammar test with greater confidence. This may be through discussing technique towards sitting the paper itself, or could be focused intervention on specific areas of grammar. However, I would also argue that this is done by referencing the ‘deeper’, or at least contextualised, learning that has gone before it.

On the whole, Y7 students revealed a greater presence of contextualised grammar pedagogies at secondary school, especially when contrasted against their experiences of primary school, with one student saying that:

It’s really different. We look at techniques more so persuasive techniques we’ve been learning about in our lessons. It’s way different to Year 6, in Year 6 it was more like the basics of grammar, recapping it from the Year 5 and Year 4. And SATs. Now as we said, in Year 7 it’s more looking deeper into books and the techniques that the author uses to show what’s happening instead of telling us and so on.

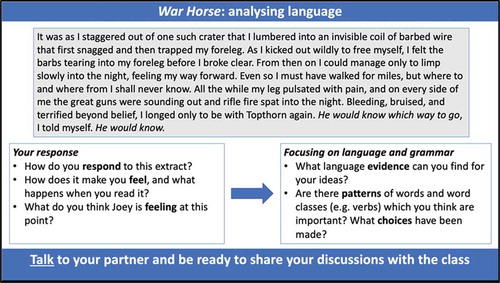

is an example resource provided by this students’ teacher, as something she felt was particularly illustrative of her own approach to teaching grammar.

shows textual traces of this school’s approach to contextualised grammar teaching, and how a set of pedagogical values get translated to classroom materials. Here, Morpurgo’s War Horse is used as an authentic text, with the activities positioning students as “readers” whose own responses and experiences are legitimated. Through key verbs (e.g. “respond”, “feel”, “talk”), readers here are invited to share and co-construct a reading experience (e.g. Maine Citation2013). These responses are then used as an entry point to explore the grammatical patterns of the text, with notions of the writer’s “choice” foregrounded. Classroom talk is the medium through which these ideas are shared, proposed and negotiated. Although only a single example, this nevertheless indicates the kind of contextualised grammar that this Y7 teacher felt she was enacting.

Whilst greater attention was given to contextualised approaches in Y7, the presence of decontextualised feature spotting and insertion was still evident, framed as sets of “right and wrong answers”. As touched upon earlier, some students’ responses across all groups suggested that they had been exposed to “additive” writing pedagogies, where writing is driven by formulaic templates and structures which require students to insert arbitrary grammatical features for point scoring. Adjectives were a common word class that were seen by students as being something that “improved” writing:

You have to put them [adjectives] in. You get better marks if it includes adjectives.

They have to be in writing. You have to put them in to write well.

Like if you’re doing something like creativity writing, you have to choose a lot of adjectives to like, to make sure you’re writing better.

Barrs (Citation2019) discusses how current policy and commercial assessment schemes can coerce teachers into enacting “bad writing” pedagogies, where writing quality is measured by the presence and absence of certain grammatical features with an overt focus on so-called “mastery” and technical “accuracy” over genuine creativity. This, argues Barrs, works as a “confining cage” and an “exercise in meeting the criteria”, which fails to assist in developing “good” writing (Citation2019, 25).

The effects of the GPS tests

All students talked about how the GPS tests had shaped their experience of English teaching at primary school. There was abundant evidence of grammar pedagogies being driven by the nature of the GPS tests, not just in the kind of test questions, but in the general system of accountability, compliance, performativity and pressure. For example, one Y6 student said that grammar classes were “revision for our tests” and “we have little booklets that we have to do every week”. Y6 students were unanimous in their beliefs that the things they had done at primary school would be useful in terms of the grammar work they imagined going on to do in secondary school, yet data from teachers have shown how secondary school teachers view the tests as damaging (e.g. Harris & Helks Citation2018).

On reflecting on their experiences, the Y7 students talked about how they “had to do grammar every day for SATs”, that “all we did was prepare for the tests”, that “Year 6 was all about doing practice papers”, and that “all our lessons in English were about grammar and SPAGFootnote1”. These comments are perhaps a little hyperbolic but are nonetheless reflective of the dominance that the GPS tests had on the experience and lasting memories of primary school students. Y7 students talked about how their work for the GPS tests “put a lot of pressure” on them, and that “we kind of overdid it”. One student said:

They made it sound like it was so bad when we actually did the test. It was just like any normal test that you’ve done. They put so much pressure, it stressed everyone out. They’re going oh my god I’m going to fail but then you actually do it, it’s not that bad.

SATs also “lived” outside the classroom: Y6 students talked about a “SATs breakfast club” and Y7 students talked about doing “grammar revision at lunchtimes”, but also “a creative writing club” where “if you were very good at English”, you could “just write” – something which didn’t happen “too much in normal English lessons”. There was some evidence that creativity was constrained by the tests: although the students talked about the value and enjoyment of creativity (particularly within the context of “creative writing”), this was often contrasted with the closed, multiple choice style questions of the GPS tests.

Despite some of the negativity around the GPS tests, there was some agreement that grammar was “useful” going forward into Year 7, to “help us make our sentences better”. However, one of the dominant themes was that grammar knowledge was about preparing for SATs: about “ticking boxes” and “completing revision papers”, with the tests working as a powerful de facto policy mechanism which have the potential to change school curricula and classroom practices (e.g. Menken Citation2008). Indeed, Bell (Citation2015, 150) argues that schools “may use the SPaG test as the closest thing there is to a guide to teaching the content” (see also Cushing Citation2020a), and so teaching and testing become difficult to disentangle. Again, we frame these criticisms not towards teachers, but towards a system of accountability where assessments can have a coercive hold over the kind of pedagogies that teachers enact. Conversations with the teachers at each school revealed a sense of tension here: the need to prepare students for SATs alongside the desire to engage in grammar pedagogies that were creative and contextualised. Similar feelings were expressed by students: they clearly knew that SATs were “important”, and enjoyed learning about aspects of grammar, but struggled to reconcile these two things. At the end of one focus group, one Y7 student perhaps put it most succinctly when she paused for a moment and then said: “grammar makes me think of going to a funeral. You’re sad but you know you have to be there”.

Conclusions

This research was motivated by existing critiques of current grammar policy in England, especially the incongruent ideas about grammar across the primary–secondary transition (e.g. Cushing Citation2019) and a lack of student voice across these critiques. To the best of our knowledge, this work offers the first attempt to explore students’ affective recollections of grammar teaching and testing within the contexts of post-2010 educational reforms in England.

There are three main findings that emerge from this work. Firstly, students’ conceptualisations of “grammar” were anchored towards word/clause-level notions, which were often conflated with “spelling” and “punctuation”. In calling up their ideas about grammar, students focused on narrow definitions based on small units of language such as morphemes, words, clauses and their associated metalanguage. In this way, students’ ideas were reflective of the way that grammar is framed within current policy, especially at primary level. Even at secondary level, there was often some resistance to concepts such as “meaning” and “choice” being associated with grammar, despite this being an overt aspect of secondary policy (e.g. Myhill Citation2018). Secondly, students’ reporting of their experiences of grammar were associated with notions of decontextualised grammar, feature spotting and the arbitrary insertion of grammatical features into their writing. However, data from our teachers revealed that this was in stark opposition to the kind of pedagogies teachers reported to be enacting, which were geared around the principles of contextualised grammar. Thirdly, across all year groups, the GPS tests work as a powerful de facto language policy (see Cushing Citation2020a), which was warping and distorting students’ experiences as well as their teachers’ pedagogies. The tests were seen as an “endpoint” for Y6 students, and “lived on” in the minds of Y7 students, being a major feature of the memories of primary school, despite this being in contrast to how teachers spoke about the tests and the kinds of experience that they were attempting to provide for their students.

Our criticisms in this article are directed towards a structure rather than towards individual schools and, teachers, and given the findings we have reported, we centre these criticisms towards the GPS testing regime and its ability to work as a de facto language policy, in shaping students’ experiences of grammar teaching. Even in classrooms that are reported by teachers to be spaces where contextualised grammar is enacted, the GPS tests remain as a powerful policy mechanism. Their future remains to be decided given the impact Covid-19 has had on education and the re-shaping of assessment mechanisms in England. We acknowledge the limitations of the study in the relatively small sample size, and posit that additional classroom observations of grammar teaching and “policy in action” would certainly be a useful avenue for future work, in threading together these attitudes and tensions in relation to grammar. Finally, we argue that this work has implications for policy makers in addressing incongruencies in terms of what is meant by “grammar” across primary–secondary, in further questioning the validity of the GPS tests, and making the case for an expanded, critical view of grammar which reflects how language is used in everyday life.

Acknowledgments

This work was generously supported by a research grant from the UK Literacy Association and we extend our thanks to them for funding this project. We also thank the students and teachers who took part in the research.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the authors.

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Ian Cushing

Ian Cushing is a Lecturer in Education at Brunel University London, with interests in critical language policy and language inequalities in education.

Marie Helks

Marie Helks is a Lecturer in Education at Sheffield Hallam University, with interests in teaching and learning grammar, specifically grammatical terminology.

Notes

1. Spelling, Punctuation and Grammar.

References

- Barrs, M. 2019. “Teaching Bad Writing.” English in Education 53 (1): 18–31. doi:10.1080/04250494.2018.1557858.

- Bell, H. 2015. “The Dead Butler Revisited: Grammatical Accuracy and Clarity in the English Primary Curriculum 2013–2014.” Language and Education 29 (2): 140–152. doi:10.1080/09500782.2014.988717.

- Bell, H. 2016. “Teacher Knowledge and Beliefs about Grammar: A Case Study of an English Primary School.” English in Education 50 (2): 148–163. doi:10.1111/eie.12100.

- Braun, A., and M. Maguire. 2018. “Doing without Believing – Enacting Policy in the English Primary School.” Critical Studies in Education 61 (4): 433–447.

- Braun, A., S. Ball, M. Maguire, and K. Hoskins. 2011. “Taking Context Seriously: Towards Explaining Policy Enactments in the Secondary School.” Discourse: Studies in the Cultural Politics of Education 32 (4): 585–596.

- Braun, V., and V. Clarke. 2006. “Using Thematic Analysis in Psychology.” Qualitative Research in Psychology 3 (2): 77–101. doi:10.1191/1478088706qp063oa.

- Carter, J. 2020. “The Assessment Has Become the Curriculum: Teachers’ Views on the Phonics Screening Check in England.” British Educational Research Journal 46 (3): 593–609. doi:10.1002/berj.3598.

- Carter, R., ed. 1990. Knowledge about Language and the Curriculum: The LINC Reader. London: Hodder.

- Cushing, I. 2019. Grammar policy and pedagogy from primary to secondary school. Literacy 53(3): 170–179.

- Cushing, I. 2020a. Grammar tests, de facto policy and pedagogical coercion in England's primary schools. Language Policy. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10993-020-09571–z

- Cushing, I. 2020b. Power, policing, and language policy mechanisms in schools: A response to Hudson. Language in Society 49(3): 461–475.

- Cushing, I. 2021. Policy mechanisms of the standard language ideology in England’s education system. Journal of Language, Identity and Education. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2021

- DfE. 2013a. The National Curriculum in England: Key Stages 1 and 2 Framework Document. London: DfE.

- DfE. 2013b. The National Curriculum in England: Key Stages 3 and 4 Framework Document. London: DfE.

- DfE. 2013c. Teachers’ Standards. London: DfE.

- Gove, M. 2013a. “Michael Gove Speaks about the Importance of Teaching.” DfE.

- Harris, A., & Helks, M. 2018. What, why and how - the policy, purpose and practice of grammatical terminology. English in Education 52 (3): 169–185.

- Hudson, R. 2016. “SPaG – A Brief History of the Teaching of Spelling, Punctuation & Grammar and the SATs Tests.” [Web log post], May 5. http://educationmediacentre.org/blog/spag-a-brief-history-of-the-teaching-of-spelling-punctuation-grammar-the-sats-tests/

- Maine, F. 2013. “How Children Talk Together to Make Meaning from Texts: A Dialogic Perspective on Reading Comprehension.” Literacy 47 (3): 150–156. doi:10.1111/lit.12010.

- Menken, K. 2008. English Learners Left Behind: Standardised Testing as Language Policy. Clevedon: Multilingual Matters.

- Milroy, J. 2001. “Language Ideologies and the Consequences of Standardization.” Journal of Sociolinguistics 5 (4): 530–555. doi:10.1111/1467-9481.00163.

- Moss, G. 2009. “The Politics of Literacy in the Context of Large-scale Education Reform.” Research Papers in Education 24 (2): 155–174. doi:10.1080/02671520902867093.

- Myhill, D. 2018. “Grammar as a Meaning-making Resource for Improving Writing.” L1 – Educational Studies in Language and Literature 18: 1–21.

- Myhill, D., S. Jones, A. Watson, and H. Lines. 2013. “Playful Explicitness with Grammar: A Pedagogy for Writing.” Literacy 47 (2): 103–111. doi:10.1111/j.1741-4369.2012.00674.x.

- Putwain, D., L. Connors, K. Woods, and L. Nicholson. 2012. “Stress and Anxiety Surrounding Forthcoming Standard Assessment Tests in English Schoolchildren.” Pastoral Care in Education 30 (4): 289–302. doi:10.1080/02643944.2012.688063.

- Rudduck, J. 1999. Education for all', 'achievement for all' and pupils who are 'too good to drift' (the second Harold Dent memorial lecture). Education Today 49(2): 3.

- Safford, K. 2016. “Teaching Grammar and Testing Grammar in the English Primary School: The Impact on Teachers and Their Teaching of the Grammar Element of the Statutory Test in Spelling, Punctuation and Grammar (Spag).” Changing English 23 (1): 3–21. doi:10.1080/1358684X.2015.1133766.

- STA. 2015. English Grammar, Punctuation and Spelling Test Framework. London: STA.

- Vasquez, V. M. 2014. Negotiating Critical Literacies with Young Children. London: Routledge.