ABSTRACT

Foreign investment is governed by thousands of international investment agreements (IIAs), many of which include investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS) provisions. Member states have played a prominent role in the evolution and shape of this decentralized global investment regime. The EU itself has become an actor in this regime since gaining competence in this area in 2009. This article examines the manners by which investment policies of the EU and its member states have evolved over time and their implications for the EU’s actorness. Using, first, the concept and metric of state regulatory space, we show that the EU is more enthusiastic than its member states about reforms, but that a lack of internal cohesiveness and a competitive external environment limit its actorness. Second, drawing on recent discussions on ISDS reforms, we highlight the increasing ability of the EU to speak up with one voice on global investment rules.

Introduction

International flows of investment are governed by thousands of international investment agreements (IIAs) forming a global regime through protections extended to foreign investors in host states (Bonnitcha, Skovgaard Poulsen, and Waibel Citation2017). IIAs encompass bilateral investment treaties (BITs), some multilateral investment treaties, and ‘free trade agreements’ (FTAs) including an investment chapter. Many IIAs include provisions on binding investor-state dispute settlement (ISDS), enabling foreign investors to directly sue host governments, claiming compensation for treaty violations. IIAs began appearing in the late 1950s, often between developed and developing countries. These agreements proliferated in the 1990s, resulting in a growing number of ISDS claims.

Such costly arbitrations, some with high public profiles, have created international tensions due to constraints on regulatory flexibility in areas of public policy (e.g. environment, energy, health and human rights (Cotula Citation2014)). The effectiveness of IIAs in encouraging inflows of foreign investment has also been questioned. These concerns spurred reform efforts of global investment governance, often referred to as ‘backlash’ (Waibel et al. Citation2010), through various methods – termination or renegotiation of IIAs (Haftel and Thompson Citation2018; Thompson, Broude, and Haftel Citation2019) and multilateral reforms aimed at reclaiming regulatory space and increasing transparency, efficiency and accountability.

The European Union (EU) and its member states have played a prominent role in the evolution of the global investment regime. The EU is a major source and destination of foreign direct investment (FDI). Member states are party to roughly one-third of all IIAs (approximately 1,400). The first bilateral investment treaty program was German-led, with other Western European countries quickly following; the European Commission is not bashful, though not entirely accurate, stating that ‘International investment rules were invented in Europe’ (Kidane Citation2018). Moreover, EU-based investors account for 60% of new ISDS cases (Titi Citation2015, 648), and member states have gained salience as respondent host-states. Finally, the EU itself has been a very active player in global investment governance since gaining formal competence in this area with the entry into force of the Lisbon Treaty in 2009. Given this reality, we ask two interrelated questions. First, how have the international investment policies of the EU and its member states changed and evolved with the transfer of competences from the latter to the former? And second, what do these changes mean for the EU’s position in global investment governance and its ability to reform it?

We answer with a two-pronged approach. First, we offer a systematic analysis of IIA content, based on the concept of state regulatory space (SRS), and a quantitative measure thereof. We define this concept as the extent of the ability of governments to freely legislate and implement regulations in given public policy domains (Thompson, Broude, and Haftel Citation2019). Since much of the debate over the legitimacy of the global investment regime emphasizes trade-offs between investor protection and host-states’ management of economic and social policies, SRS strikes at the heart of the issue (Cotula Citation2014; Franck Citation2005; Schill Citation2007; UNCTAD Citation2012). Comparing SRS in IIAs signed by member states, the EU, and other key actors enables inferences about their relative positions regarding global investment rules and EU ability to impact in this area. Next, we turn to a qualitative case-study analysis of ongoing discussions of ISDS reforms within the United Nation’s Commission on International Trade Law (UNCITRAL) since 2017. Drawing on written submissions and recorded minutes, we focus on ways in which the EU has utilized this multilateral forum to promote its reform agenda.

This inquiry highlights two important findings. First, both the quantitative analysis of SRS and the UNCITRAL case-study demonstrate the EU’s leadership and innovation in current efforts in IIA regime towards tilting the balance in favor of greater state regulatory flexibility and legitimation. EU competence has been contested by some member states, not all of which share its perspectives. Thus, differences among member states, and between member states and the EU, have reduced the internal cohesiveness of the EU and limited its ability to shape global investment rules. This, however, is less evident at the multilateral level, where cohesiveness has been quite strong. Second, a comparison of the EU’s approach to that of other leading powers, namely the United States, Brazil, and India, indicates that there are competing visions regarding the best way to reform global investment governance, such that the EU’s position is externally contested. This has been evident at the multilateral level. Thus, if the EU hopes to effectively influence the shape of the global investment regime, it should continue to increase efforts to speak with one voice.

This article makes two important contributions to the extant literature on the EU’s role in global governance. First, in line with other contributions in this collection, it advances our understanding of the external dimension of EU actorness. In this regard, Bretherton and Vogler (Citation2013, 378) emphasize presence, capabilities, and opportunity as key aspects of actorness, with the latter referring to the ‘the external context of ideas and events that enable or constrain action.’ However, as others have argued (Conceição-Heldt and Meunier Citation2014, 964), this is a pretty broad and vague definition that is difficult to operationalize empirically. In turn, Conceição-Heldt and Meunier (Citation2014), underscore the importance of internal cohesiveness (defined as a combination of cohesion, consistency and coherence) and external recognition for actorness, but this, too, remains rather general and underspecified We build on these studies to clarify the role of the EU in global investment governance

Second, the governance literature on the EU’s investment policy is still embryonic, with several notable blind spots. Several studies examine the circumstances that led to the transfer of competence from member states to the EU in 2009 (Meunier Citation2017; Reinisch Citation2014; Titi Citation2015) or the struggle over investment policy within the EU in the aftermath of this transfer (Basedow Citation2021), but overlook its implications for and interaction with the global investment regime. Two studies, Meunier (Citation2014) and Meunier and Morin (Citation2017), engage more directly with the notion of EU actorness and the influence of its investment policies on global rules and practices. Nevertheless, their analysis is wanting in precision and does not offer a systematic comparison of IIAs’ content of the EU, its member states, and other key actors involved in the global investment regime. By using a standardized metric to compare and analyze the degree of regulatory space in IIAs and by exploring the role of the EU in multilateral negotiations over investment rules, we shed new light on the consequences of the EU’s newly acquired competencies for the global investment regime and for its position within this increasingly important policy domain. Moreover, these studies mostly preceded the multilateral UNCITRAL process and therefore do not address it. The few studies of the UNCITRAL process (Roberts Citation2018; Roberts and St. John Citation2022) do not focus on the EU as such – but are more concerned with UNCITRAL as a global governance environment and observations on the engagement of the full range of actors with it, including the EU.

Overall, our assessment is that the EU has in recent years gained significant actorness in the field, though not without resistance, both intra- and extra-EU; these are the ‘growing pains’ of actorness.

European investment policies through the prism of state regulatory space

In this section, we inquire into the ways by which the IIA policies of member states and the EU have evolved and how they are compared with those of non-European states. Going beyond most, if not all, current analyses of European investment policies, we engage in a systematic comparison of IIA content across time and space, utilizing the concept of SRS, defined above. This allows us to draw conclusions about EU actorness and its ability to affect the global investment regime. We begin with a brief discussion of our conceptual and methodological approach to investigating variations in the content of IIAs. We then turn to member states’ IIAs before the 2000s, and demonstrate that they are heterogeneous. Next, we examine the IIA policies of the EU and member states in more recent years and compare them to those of other countries. This analysis points to greater, but far from complete, cohesiveness of European investment policies. Given a more constraining global opportunity structure, these developments increase the ability of the EU to affect global investment policies to some extent.

We conceptualize SRS as a continuum rather than a binary attribute of an investment agreement. At one extreme, states have much flexibility to pursue policies they see fit, thus insulated from external pressure. At the other extreme, governments have little room to maneuver, highly constrained by foreign investors’ ability to challenge policies under IIAs and ISDS. To measure SRS, we utilize UNCTAD’s IIA Mapping Project,Footnote1 examining the most important substantive and procedural provisions of IIAs, and coding them on inclusion or exclusion of various elements. This raw coding was transformed in selected categories into measures that indicate, in our estimation, more or less SRS, classified into 91 separate indicators subsumed under 42 categories, which in turn are grouped under eight broader dimensions of IIAs, central to SRS. We then standardized the measure such that each IIA ranges from low to high SRS, with zero indicating minimum SRS and one indicating maximum SRS (as afforded by the IIAs).

in the Appendix lists all the categories and dimensions included in our SRS measure. A detailed exposition of this measure, its logic, and components is available elsewhere (Broude, Haftel, and Thompson Citation2017; Thompson, Broude, and Haftel Citation2019). By way of illustration, most IIA preambles state that the main goals of the treaty are to promote foreign investment and protect foreign investors. Some, but not all IIAs, attempt to balance investor protection with other goals, such as the right to regulate, sustainable development and environmental investment aspects. The more these objectives are mentioned, the higher the SRS score in this dimension. Similarly, most IIAs include a most favored nation (MFN) clause, but some exclude it within the context of regional organization, taxation, or procedural rules. The more such exceptions appear, the greater the state’s SRS. Regarding ISDS provisions, if included, SRS increases with more exceptions, limitations, and conditions that restrict foreign investors' ability to utilize it (Broude, Haftel, and Thompson Citation2022).

With this measure in hand, we coded close to 2,800 IIAs from 1959 to 2016, which is about 85% of existing IIAs, most of them are BITs, but some are FTAs with investment chapters. In total, 1,118 IIAs, about 40% of the sample, involve at least one EU member state, and close to two-hundred IIAs in our sample were concluded between current member states before at least one of them joined the EU. Importantly, we coded several IIAs signed by the EU itself since 2009. Finally, we coded close to a hundred ‘Model BITs’, many of them issued by European countries. These are templates of investment agreements drafted and published by governments and are used as a going-in-position for negotiations over the actual agreements. They are important insofar as they represent a particular country’s ‘ideal point’ over the regulation of foreign investment (Brown Citation2013; Broude, Haftel, and Thompson Citation2022). Taken together, these data provide a vivid, wide-ranging and nuanced picture of the IIA regime and of Europe’s position in it.

Member states’ IIAs before 2009

IIAs proliferated in two waves. The first started with the Germany-Pakistan BIT in 1959, lasting until the end of the Cold-War, amounting to several hundred treaties over the entire period. Most of these BITs were signed between Western European and developing countries from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. While their main objective was to protect European foreign investors against political risk in host countries, many of them were designed towards substantive standards of treatment and did not contain ISDS provisions (Poulsen Citation2020). Some of those early treaties were later renegotiated to include ISDS (Haftel and Thompson Citation2018).

The second wave, lasting from the early-1990s to the mid-2000s, saw many states concluding IIAs as part of more comprehensive economic liberalization programs, associated with the ‘Washington Consensus.’ About 2,200 IIAs were signed during these years, mainly BITs, but some FTAs with investment chapters (most notably, the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA)), and the unique multilateral, sector-focused Energy Charter Treaty (ECT). Regarding this shift’s causes, observers point to competitive pressures that capital-importing countries were facing (Elkins, Guzman, and Simmons Citation2006), adherence to prevailing neoliberal policies, or overestimation of IIA benefits and underestimation of their costs (Poulsen Citation2015).

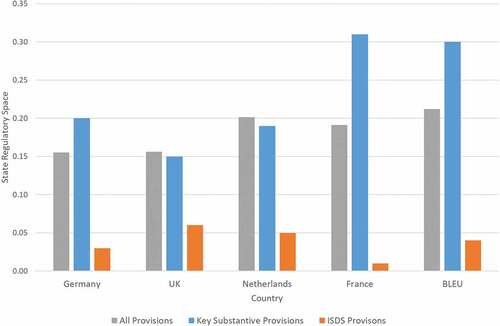

Considering the lasting impact of IIAs signed during these years, we begin the analysis of SRS here. Received wisdom was that there is little variation in the content of IIAs concluded in this ‘golden age’ of the global investment regime (Dolzer and Stevens Citation1995; Guzman Citation1998). Specifically, it is often assumed that they reflected a great deal of investor protection at the expense of the host-state’s sovereignty and regulatory space (Elkins, Guzman, and Simmons Citation2006; Guzman Citation1998). Indeed, Meunier and Morin (Citation2017, 896–897) argue that global and European IIAs have converged on a core set of rules, thereby producing a de facto multilateral investment governance. Assessing this perception, we compare the average SRS of IIAs signed in the 1990s by the five member states with the largest BIT programs: Germany, UK (pre-Brexit), France, the Netherlands, and the Belgium-Luxembourg Economic Union (BLEU). By disaggregating the composite SRS measure, we also compare them on key substantiveFootnote2 and ISDS provisions.

As shows, overall SRS (gray) appears rather similar for all five programs, ranging from 0.16 (UK) to 0.21 (BLEU). However, it is also apparent that some member states have been more interested in preserving SRS in their BITs than others, especially with respect to important substantive matters (blue): French and BLEU BITs score significantly higher on such provisions, compared to the other three states (and the UK in particular). This observation highlights the lack of uniformity of European IIAs, even during the 1990s, the heydays of seemingly ‘simple’ and uniform BITs. This finding is consistent with Titi’s observation (Citation2015, 649) that despite having an overall similar approach, ‘EU [member states’] BITs have by no means been identical among them or even largely similar.’ Along similar lines, Meunier (Citation2014, 998), who asserts that the EU gained informal competence over external investment policy through its competence over trade agreements, concludes that ‘the pre-Lisbon governance of foreign investment policy in the EU was truly cacophonic.’ We thus concur with Conceição-Heldt and Meunier (Citation2014, 972) that EU IIA policies reflected low internal cohesiveness.

Member states and EU IIA Policies since 2009

The second half of the 2000s witnessed two developments that affected member states’ investment policies and EU actorness in this issue area in important ways. First, given growing doubts about the economic benefits of IIAs (Bonnitcha, Skovgaard Poulsen, and Waibel Citation2017) and the high costs associated with ISDS (Wellhausen Citation2016), many host states and other stakeholders began to wonder whether relinquishing sovereignty and delegating power to international arbitrators is justified and called for a ‘rebalancing’ of investors’ rights and host-states’ flexibility (Waibel et al. Citation2010). Some governments responded with greater reluctance to sign IIAs, greater propensity to revise their Model BITs and renegotiate or denounce existing IIAs (Haftel and Thompson Citation2018; Poulsen and Aisbett Citation2013; Thompson, Broude, and Haftel Citation2019). Thus, the third, current, phase of the global investment regime is characterized by a more selective conclusion of IIAs, greater attention to IIA content, as well as IIA renegotiation and termination. We demonstrate that member states and the EU played a significant, though not exclusive, role in shaping current investment rules along these lines.

Second, member states transferred competence over IIAs to the EU in the 2007 Lisbon treaty, in force since 2009. As a result, the Commission started negotiating and signing investment agreements on behalf of the EU as a whole, exemplified by the conclusion of the Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (CETA) with Canada in 2016. Notably, however, the transfer of competence was by no means complete, in either effect or in substance. In effect, while the number of IIAs signed by individual member states substantially dropped, new or renegotiated such IIAs as well as new Model BITs continued to trickle. In our sample, member states signed eight IIAs in the years 2012–2016 (compared to an annual average of 50 IIAs in the 1990s and about 40 IIAs in the 2000s).

In substance, while the Lisbon Treaty aimed to consolidate the EU’s global investment policy, it did so without any prior agreement between the EU’s institutions and member states on the shape of EU-made IIAs, leaving many structural legal questions open, such as the fate of IIAs between member states (intra-EU BITs) or the more than one-thousand pre-existing member state-made extra-EU BITs. The increasing use of ISDS by investors, both within the EU and from outside, against member states, frictions between arbitration and European court systems, and the rising international critique of IIAs, resulted in a very dynamic and contentious series of developments in European IIA policies over the last decade. Many of these entailed a continuation de facto of the pre-Lisbon internal disharmony, fragmentation and uncertainty, with the involvement of a multiplicity of European actors, at EU, state and sub-state levels, and intensive negotiation, litigation and arbitration, closely followed by the international investment protection community (see an annotated timeline of the main developments between 2007 and 2021 – in the Appendix).

Thus, a treaty to abolish intra-EU IIAs was signed only in 2020, with most extra-EU IIAs remaining intact. Questions with respect to the competence (i.e. mixed vs. exclusive) of the EU to ratify IIAs, and especially ISDS provisions, are yet to be fully settled. These developments, reflecting at least a transitional weakness of internal cohesiveness between the EU and its member states, had a profound influence on the nature and trajectory of EU actorness and its impact on global investment governance (Basedow Citation2021; Meunier Citation2014). These are intricate and crucial affairs that have gained much attention, particularly among legal practitioners and academics; we illuminate them here from the vantage point of SRS, and will revisit them in our discussion of the multilateral UNCITRAL negotiations.

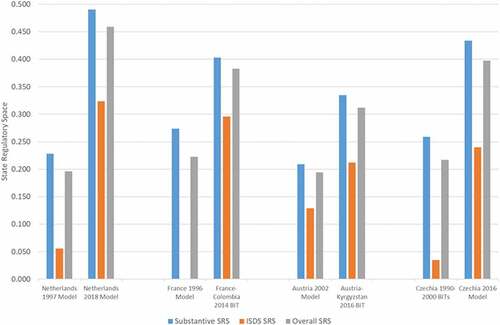

Illustrating the upsurge of SRS in European IIAs, compares Model BITs and/or IIAs of four member states – the Netherlands, France, Czechia, and Austria – in the 2010s and earlier.Footnote3 As made clear, SRS increased dramatically for the first three countries, and more moderately for Austria. This increase is especially remarkable with respect to procedural provisions. SRS related to ISDS jumped about six-fold from the 1997 to the 2018 Dutch Model BIT and from Czech BITs signed in the 1990s to its 2016 Model BIT; substantive SRS has increased about twofold for both. In France, SRS ISDS jumped from zero in its 1996 Model BIT to almost 0.30 in its 2014 IIA with Colombia. Similar to previous years, then, it is apparent that there is no convergence in SRS across these four states, even if they move in the same direction. Varying SRS levels on substantive and procedural provisions suggest that member states continue to have different ideas on the design of future IIAs. Thus, the lack of internal cohesiveness and ‘cacophony’ of investment policies (Meunier Citation2014) is still visible.

Moreover, beyond the differences between member states’ policies, attention should be paid to their shared trend towards increased SRS – but as we shall see below (), at a lower level of ambition than non-EU states, and indeed of the EU itself. Recall that these shifts in member state SRS took place during the unsettled formative post-Lisbon decade, while policy was still being formulated by the Commission and applied through new and innovative EU-made IIAs, and legal and political frictions over competence dominated the intra-EU scene. This common trend may indicate a strong interest of member states to signal to EU institutions what their IIA policy should look like for it to enjoy intra-EU legitimacy: increased SRS, but within the bounds of member state policies, for fear that the Commission would go too far in this direction, possibly at the expense of the protection of member state-based foreign investors. In other words, even as the EU was pursuing an agenda of IIA reform, member state actions on the external plane, such as new BITs and Model BITs, attempted to impose a check on the EU’s global actorness, typical of a period of transition, in which external recognition of authority and autonomy (Conceição-Heldt and Meunier Citation2014), that is by non-EU actors, could not yet be fully granted to the EU

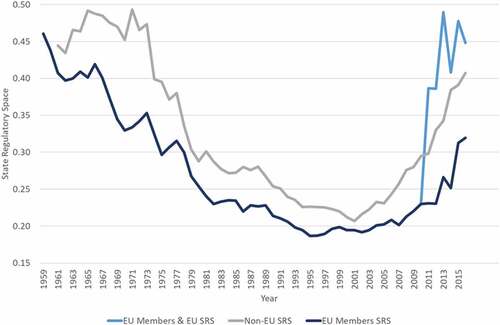

Figure 3. Annual three-year moving average of SRS in IIAs signed by member states, the EU, and the rest of the world.

Indeed, a more complete grasp of the potential impact of elevated SRS levels in European IIAs, and in turn EU actorness, must consider the external environment (Bretherton and Vogler Citation2013; Conceição-Heldt; Meunier Citation2014). Offering a glimpse into this matter, we compare temporal changes in SRS levels in European and non-European IIAs. shows the annual three-year moving average SRS for IIAs involving three groups of parties from 1959 to 2016. First (dark blue), IIAs involving at least one member state (from accession, for members that joined the EU after 1957), thus including both current intra-EU and Extra-EU IIAs. Second (light blue), IIAs that involve at least one member state as well as six IIAs signed by the EU from 2012 to 2016 with Iraq, Georgia, Moldova, Ukraine, Kazakhstan, and Canada. The third group (grey) includes all IIAs excluding any party associated with the EU.

As indicates, SRS in member states’ IIAs tracks similar trends in the global investment regime. Early on, most BITs reflected high SRS, mainly because they lacked ISDS. This changed gradually, and led to BITs with much lower SRS in the 1990s. It appears, however, that IIAs signed by member states have consistently lower SRS compared to IIAs concluded by other states. This indicates that, on balance, member states preferred IIAs with a great deal of investor-protection with lower concern for host-state’s SRS (Titi Citation2015). This makes sense, as several member states were leading capital-exporters, e.g. Germany, France, the UK, and the Netherlands, while most non-EU countries with IIAs were capital-importers, and many post-communist states continued into the 1990s having BITs with only limited ISDS.

IIA SRS by member states also tracks the global trend towards greater SRS from the late-2000s onwards. Here, it seems that they somewhat lag behind other states, more reluctant to forgo investor protection. Thus, the gap in average SRS between the two groups of IIAs increases from 0.01 in 2001 to 0.09 in 2016. The increase in SRS () is not unique to EU members and, if anything, it appears that they have been less enthusiastic about embracing investment treaty reforms, compared to the rest of the world. The upshot of this observation is that the continuing engagement of member states in shaping investment rules undermines EU ambitions to develop a coherent and consistent approach to IIAs, and in turn to shape global investment governance.

Reinforcing this conclusion, the relations between European IIAs and those concluded by the rest of the world are flipped when IIAs signed by the EU itself are included. Because these IIAs reflect much higher SRS, they pull the entire European average above the global mean in the 2010s.Footnote4 This suggests that as the EU has gained authority and autonomy, there are two necessary conditions for actorness (Conceição-Heldt and Meunier Citation2014). In relation to investment policies, it was able to develop and adopt innovative rules in this issue area and to transform into a front-runner in global investment governance reforms. Moreover, being able to advance a similar position in several EU-made IIAs, it enhanced its cohesiveness and, in turn, its actorness. This is in spite of member state attempts to constrain EU external actorness by asserting their own competence and signaling through their actions the limits of reform. Based on this analysis, the assessment that the EU’s internal cohesiveness and external effectiveness in this issue-area have increased from low to intermediate (Conceição-Heldt and Meunier Citation2014, 972) remains accurate. Given more recent developments, not captured in either this latter assessment or in measures of SRS, EU actorness may be higher still today (as will be seen in our discussion of UNCITRAL negotiations).

Caution is warranted, however – most of the EU-made agreements in our sample are not full-fledged IIAs. They tackle only a limited number of substantive matters related to foreign investors’ protection and have no ISDS provisions. They do not replace existing BITs between member states and partner countries.Footnote5 They are therefore not the most reliable reflection of the EU’s approach to global investment governance. With this in mind, we take a closer look at investment commitments in CETA and contrast them with notable non-EU IIAs or Model BITs.

A comparative assessment of SRS in current IIAs: CETA and others

Signed in 2016, CETA is a very significant agreement insofar as it is the first signed by the EU with a third-country that includes extensive investment provisions and the first to refer to an International Court System and Multilateral Investment Court (MIC) – a major element of the EU’s reform agenda that we will return to in our discussion of EU participation in UNCITRAL negotiations. As such, we submit that CETA represents the closest thing to an EU model agreement with developed countries, that is expected to gradually succeed national IIAs (though we acknowledge that Canada had an influence on the content of the agreement as well). Notably, its investment provisions have been virtually replicated in the 2019 BLEU Model BIT, only after the CJEU issued its decision in the Waloon-Belgian challenge to CETA’s Investment Court System provisions in Opinion 1/17 in 2019, finding them compatible with EU law.

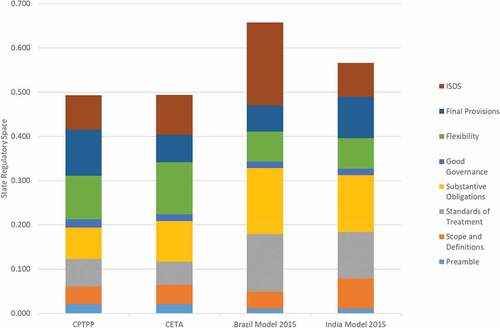

To have a better sense of how the EU’s approach stacks up against other efforts to reform global investment governance, we compare CETA to investment commitments in the 2016 Comprehensive and Progressive Agreement for Trans-Pacific Partnership (CPTPP), the 2015 Brazil Model BIT, and the 2015 India Model BIT. The CPTPP was negotiated between 12 countries and its design was heavily influenced by the United States (US). Even though the US eventually withdrew from the previous incarnation of this agreement, it still reflects its position on international investment law to an important extent (Allee and Lugg Citation2016; Broude, Haftel, and Thompson Citation2017).Footnote6 Brazil’s and India’s Model BITs reflect the perspectives of these two important large and emerging countries on the direction that IIA design should take. Together, these three non-EU texts provide a good depiction of the EU’s external environment regarding IIAs and the degree of convergence (or lack thereof) between its own and other key actors’ approaches to the balance between investor protection and SRS.

presents overall SRS in the four texts as well as the values in each of its eight dimensions. Surprisingly, perhaps, CETA and CPTPP have an almost identical score on overall SRS: 0.494 and 0.493, respectively. Notably, these are much higher values than traditional BITs, most Model BITs, and even FTAs with an investment chapter that include ISDS provisions.Footnote7 This highlights that these two agreements reflect genuine efforts of parties to respond to growing criticism of global investment rules and to reclaim SRS in several ways. It also suggests that a synthesis of the two approaches is possible, but, as we discuss next, important differences remain. As shows, however, these values are lower than India’s and Brazil’s IIA templates, showing that the latter, and Brazil in particular, prefer to tilt the balance in favor of host-state flexibility even further than the EU and the US (taking CPTPP as indicative of US preferences at the relevant time, although ultimately not a party).

These different approaches are apparent with a more fine-grained comparison of different provisions. There are several similarities between the CETA and the CPTPP, as both keep the main elements of earlier IIAs in place. Thus, they refer to the main standards of protection, Most favored Nation Treatment (MFN), National Treatment (NT and Fair and Equitable Treatment (FET), including qualified indirect expropriation, and binding ISDS. At the same time, both CETA and CPTPP emphasize the need for a balance between investor protection and other policy goals. This is apparent, for example, in preambular language, the incorporation of several references to good governance, and numerous exceptions for and limitation on the scope of substantive protections. Even so, they do not go as far as India’s and Brazil’s Model BITs. On substantive matters, the former excludes MFN and the latter excludes FET. On procedure, India’s model requires an effort to exhaust local remedies for 5 years and Brazil’s excludes it altogether.Footnote8

The relative similarity between CETA and the CPTPP might suggest that, to the extent that the EU can speak with one voice, leading OECD economies can develop an agreed-upon template that could potentially set global standards, while challenged by the approaches of large economies. One should nevertheless keep in mind several important differences between the two agreements. On substantive matters, CPTPP includes a more restricted definition of FET, but CETA contains more public policy exceptions (subsumed under ‘flexibility’ in ). In another important difference, the CPTPP does not include a survival clause, which protects foreign investors if the agreement was terminated for several more years after the termination. There are more substantial differences with respect to procedural rules. CETA includes more limitations on the scope of claims, while CPTPP goes further on rules related to interpretation and transparency. Thus, while the aggregate measures of SRS in CETA and CPTPP are almost identical, they reach the same result in different ways. Moreover, we note, that the SRS measure captures ISDS-related rules incompletely, because it does not consider the possibility of a permanent investment court, such as the MIC. This, of course, is a very significant potential innovation that was not anticipated when UNCTAD developed its ‘mapping’ guidelines. Given that such a MIC is yet to be established and become operational, if at all, its implications for SRS are currently unknown. With respect to EU actorness, it is a gap to be filled by scrutiny of the EU’s role in promoting the idea of a MIC, primarily in UNCITRAL, as we do in the next section.

Other developments should be noted here, in comparison. One is the conclusion of the US-Mexico-Canada FTA (USMCA), NAFTA’s successor, effective since 2020, which has all but done away with ISDS within the North American economic bloc and created differential ISDS relations between the three parties (Côté and Ali Citation2022). This arguably reduces comparative SRS for the EU vis-à-vis Canada under the CETA, but provides EU investors in Canada with advantages in comparison with US investors. Furthermore, alongside India and Brazil’s current Model BITs, Morocco and Nigeria signed a new BIT in 2016, which is very innovative in terms of substantive content while preserving ISDS. These efforts underscore the reality that developing countries no longer accept the position of rule-takers and strive to make their own mark on global investment governance. As a consequence, the EU’s external environment has become more complex and constraining, with several key actors jockeying for influence over the direction of investment rules’ reforms.

In summary, from our quantitative text-driven analysis, it appears that the EU, as a collective actor, is a leader in the current efforts to reform the global investment regime and to tilt the balance in favor of greater SRS. As policy-making authority within the EU in this area continues to shift from member states to the EU, this tendency should become ever more apparent. That is, with greater and more clearly defined authority and autonomy, the EU exhibits greater actorness and internal cohesiveness and its presence in global investment governance is much plainer to see (Bretherton and Vogler Citation2013; Conceição-Heldt; Meunier Citation2014). The EU is not the only actor moving in this direction, as the comparison between CETA and other notable agreements and model IIAs makes clear. Consequently, even as EU actorness in global investment policy matures, the external environment is becoming more complex and competitive, with other key countries advancing their own visions of how to reform the global investment regime, which are not necessarily compatible with the EU’s own perspective. This constrains the EU's ability to advance its preferred approach globally. If the EU and member states hope to shape global rules in relation to the protection of foreign investment and the preservation of regulatory flexibility, efforts to unify positions and speak with one voice should be increased.

Europe’s actorness on the multilateral stage: The UNCITRAL reform talks

UNCITRAL is the closest in character to a formal international organization in the global investment regime, though as noted, it is neither the forum for settling investment disputes (arbitral tribunals established ad hoc, applying UNCITRAL or other arbitration rules), nor the forum for determining substantive rules (the network of IIAs). It is, however, currently a central forum, if not the most important multilateral one, for developing the main procedural, yet crucial, rules on conducting ISDS.

UNCITRAL is a subsidiary body of the UN, established in 1966, with the mandate of promoting progressive harmonization and unification of ‘international trade law’, which in practice has been most related to private commerce and investment protection. It is thus associated with several international conventions that were designed without international investment law in mind but have had significant impacts on the investment protection universe, such as the Convention on Contracts for the International Sale of Goods, as well as other instruments (see Block-Lieb and Halliday Citation2017; Haftel and Broude Citation2022).

In July 2017, UNCITRAL Working Group III (WGIII), as a subset of the membership, was charged with a broad mandate regarding the reform of ISDS. This could be considered a major development, as it represented the first multilateral forum to discuss elements of global investment governance since the failed OECD-sponsored negotiations towards a multilateral investment agreement in the 1990s. It must be acknowledged, however, that UNCITRAL debates at the level of ‘hard law’ are only as good as the decisions and norms they produce. In any case, UNCITRAL WGIII has provided an important forum for ideas that states and other actors are pursuing and promoting with respect to ISDS, as a central component of the global investment regime (Roberts Citation2018; Roberts and Taylor Citation2022; Langford et al. Citation2020).Footnote9

WGIII was initially tasked with identifying concerns and making recommendations in three categories, divisible into sub-categories: (1) consistency, coherence, predictability and correctness of arbitral awards; (2) concerns pertaining to arbitrators and decision-makers; and (3) concerns pertaining to cost and duration of ISDS cases. Subsequently, the WG agenda was augmented with reference to the issue of third-party funding. While the EU has been very active on all these fronts, its main interest and influence in the process has been in its promotion of the initiative to establish a Multilateral Investment Court (MIC) (Roberts Citation2018, 426; Swoboda Citation2022). The MIC – the proposition that the fragmented system of ad hoc investment tribunals should be replaced by a standing international court in order to cure the legitimacy gaps of ISDS (for early analysis see Howse Citation2017) is very much of an EU initiative. Formally launched in an EU Commission ‘Concept Paper’ in 2015 (EU Citation2015), it is reflected in the inclusion of provisions for the participation in an ‘Investment Court System’ (ICS) in the first major IIAs signed by the EU (CETA (2016) EU-Singapore (2019) and EU-Vietnam (2020)). Indeed, the ICS provisions in the first two of these were significant factors in the intra-EU legal battle over competences, described above and in (see Appendix). No less importantly, it is primarily the EU’s MIC proposal in UNCITRAL that has earned the EU the descriptors of ‘innovative’ (Howse Citation2017) and a ‘Systemic reformer’ (Roberts Citation2018).

Based on our own count and assessment, the EU has made the largest number of written submissions to WGIII in comparison to all other UNCITRAL members, on a variety of topics. Moreover, it has participated vocally and intensively in the negotiations themselves, with numerous oral interventions. Most importantly, it was the EU that put the MIC on the negotiation table in a detailed submission in 2017, and from 2018 on, the EU has put its full weight into promoting its reform agenda in WGIII, especially, but not only, regarding the MIC concept. The dominance of the EU in promoting the idea of a MIC has been so high that the WGIII Chair, in 2018, had to assure members that ‘[t]he assignment in this working group is absolutely not the European Commission’s proposal. We have our own mandate, and the idea that that is what we are here to do is absolutely false’ (Roberts Citation2018).

Notably, throughout WGIII discussions, member state interventions were aligned with and supportive of EU positions. In 2019, the EU delegate clarified that the EU speaks for its 28 (at the time) member states and the German delegation noted that this would be more time-efficient than having all the member states make the same points. In 2020, the German and Spanish delegations established that their opinions are aligned with that of the EU.Footnote10

Indeed, we detect a dramatic change in the participation of the EU and member states between 2017 and the present. Whereas in the first WGIII session in 2017, the EU did not openly participate, but 9 member states did (including the UK, pre-Brexit), a mere four years later it was clear that the EU was representing the voice of all members. Thus, comments from the EU on draft provisions relating to the selection and appointment of investment adjudicators were, in 2021, submitted under the joint flag of the EU and its member states (UNCITRAL Citation2021). Formally this is anomalous, with the EU being the only observer in UNCITRAL.

We submit that the analysis of the EU and member state participation in UNCITRAL WGIII negotiations (from 2018) suggests a high level of EU actorness in several respects, above what was intimated earlier in time. Following Bretherton and Vogler (Citation2013), we find a high degree of presence, capabilities, and a strong utilization of the opportunities presented by the multilateral forum, met with a high level of external recognition. Clearly, such a recognition is not devoid of disagreement, but this is only to be expected, given the diversity of opinion in WGIII. As far as cohesiveness is concerned (Conceição-Heldt and Meunier (Citation2014)), the performance of the EU (as an observer) and its member states has at least been outwardly harmonious.

This raises the question, how and why the multilateral WGIII forum has overcome the intra-EU ‘cacophony’ apparent from the quantitative analysis above. As Howse (Citation2017) describes, the outcomes of the intra-EU legal battle over the division of competences between the EU and member states ‘offered a large incentive to the [EU] Commission to drop the ICS from its bilateral negotiations and put this innovative approach to ISDS on a purely multilateral track’. We agree; the relative clarification of boundaries between the EU and member state competences by the Court of Justice of the EU (CJEU) and subsequent agreements – mainly Opinion 2/15 (2017), Achmea (2018) and Opinion 1/17 (2019) and the treaty on termination of intra-EU BITs (2020) (see ) has brought about much greater cohesiveness, both internally and in presenting positions to the global forum.

Conclusion

The EU’s path to actorness in the area of global investment regulation has not been strewn with roses. Vested with ‘exclusive’ competence by the Lisbon Treaty in 2009, it has had to develop a strategy at the EU level, taking into account competing interests of member states with respect to SRS and foreign investment. Arguably, the EU’s actorness began coming into age from 2015 onwards. On the way, it has had to undergo many obstacles, primarily inflicted by the legal and political difficulties posed by member states pushback regarding the meaning of exclusivity. Consequently, the ability of the EU to speak with one voice was impaired, hence detracting from internal cohesiveness and external influence. In parallel, the complexity of the external environment, populated by a diversity of strong actors, developed and developing, with their own views has created challenges to the EU as a ‘new kid’ on the block, having hithertofore not been a unitary actor in this area. It has had to work hard, both internally and externally to achieve its actorness. The relative resolution of internal differences through engagement with member states in all EU institutions, not least the CJEU, greatly increased the cohesiveness of the EU and its member states. This has allowed the EU to assert its presence and capability on the global, multilateral stage, through innovative EU-led IIAs, and in the last 5 years, by seizing the opportunity posed by UNCITRAL WGIII to promote its agenda, primarily a multilateralized ISDS system through the MIC concept. Evidently, actorness is not granted, it must be gained, with many growing pains; these have not yet passed, but it appears that the EU is on the right path to consolidating its actorness in the field.

Acknowledgment

Authors’ names appear in alphabetical order and reflect equal co-authorship. For helpful comments and suggestions, we thank the members of the GLOBE consortium, the journal editors, and the anonymous referees. We thank Meori Elias for excellent research assistance. Research for this article was generously supported by the European Union’s Horizon 2020 Research & Innovation programme under Grant Agreement no. 822654.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Additional information

Funding

Notes on contributors

Tomer Broude

Tomer Broude is a Professor and the Bessie and Michal Greenblatt QC Chair in Public and International Law, Faculty of Law and Department of International Relations, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Yoram Z. Haftel

Yoram Z. Haftel is a Professor and the Giancarlo Elia Valori Chair in the Study of Peace and Regional Cooperation at the Department of International Relations, Hebrew University of Jerusalem.

Notes

1. UNCTAD Mapping of IIA Content (last visited 3 May 2022).

2. Key substantive provisions refer to those involving important standards of treatment (e.g. MFN, national treatment (NT), and fair and equitable treatment (FET)), direct/indirect expropriation, and compensation.

3. These four cases were selected because they are the only member states that have readily available Model BITs or IIAs from both time periods.

4. Adding to that is the relatively small number of IIAs signed by member states in the 2010s, as already mentioned.

5. Two additional EU IIAs that include more substantial investment rules are those with Singapore and Vietnam in 2018 and 2019.

6. The CPTPP was re-signed and entered into force in 2018.

7. But not in comparison with IIAs without ISDS. For example, the five other IIAs signed by the EU as well as recent agreements based on the 2015 Brazilian template, all lacking ISDS, score higher on SRS.

8. Instead, Brazil’s template provides for consultation and mediation through a Joint Committee and an Ombudsman.

9. UNCITRAL was previously engaged in procedural law-making regarding ISDS in the formulation of the 2013 Rules on Transparency in Treaty-based Investor-State Arbitration (Haftel and Broude Citation2022, 34).

10. These observations are based on our following of the EU and member state oral statements in WGIII, available online on the UNCITRAL website, https://uncitral.un.org/en/working_groups/3/investor-state.

References

- Allee, Todd, and Andrew Lugg. 2016. “Who Wrote the Rules for the Trans-Pacific Partnership?” Research and Politics July–September, 2016: 1–9.

- Basedow, Robert. 2021. ““The Eu’s International Investment Policy Ten Years On: The Policy-Making Implications of Unintended Competence Transfers.” Journal of Common Market Studies 59 (3): 643–660.

- Block-Lieb, Susan, and Terence C. Halliday. 2017. Global Lawmakers: International Organizations in the Crafting of World Markets. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Bonnitcha, Jonathan, Lauge N. Skovgaard Poulsen, and Michael Waibel. 2017. The Political Economy of the Investment Regime. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Bretherton, Charlotte, and John Vogler. 2013. “A Global Actor past Its Peak?” International Relations 27 (3): 375–390. doi:10.1177/0047117813497299.

- Broude, Tomer, Yoram Z. Haftel, and Alexander Thompson. 2017. “The Trans-Pacific Partnership and Regulatory Space: A Comparison of Treaty Texts.” Journal of International Economic Law 20 (2): 391–417. doi:10.1093/jiel/jgx016.

- Broude, Tomer, Yoram Z. Haftel, and Alexander Thompson. 2022. “Legitimation through Modification: Do States Seek More Regulatory Space in Their Investment Agreements?” In The Legitimacy of Investment Arbitration: Empirical Perspectives, edited by Daniel Behn and Ole Kristian Fauchald, 531–554. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Brown, Chester. 2013. “Introduction: The Development and Importance of the Model Bilateral Investment Treaty.” In Commentaries on Selected Model Investment Treaties, edited by Chester Brown. 1–13, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Côté, Charles-Emmanuel, and Hamza Ali. 2022. “The USMCA and Investment: A New North American Approach?” In NAFTA 2.0: From the First NAFTA to the United States-Mexico-Canada Agreement, edited by Gilbert Gagné and Michèle Rioux, 81–98. Cham, Switzerland: Springer Nature.

- Cotula, Lorenzo. 2014. “Do Investment Treaties Unduly Constrain Regulatory Space?” Questions of International Law 9: 19–31.

- da Conceição-Heldt, Eugénia, and Sophie Meunier. 2014. “Speaking with a Single Voice: Internal Cohesiveness and External Effectiveness of the EU in Global Governance.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (7): 961–979. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.913219.

- Dolzer, Rudolf, and Margrete Stevens. 1995. Bilateral Investment Treaties. Boston: Martinus Nijhoff.

- Elkins, Zachary, Andrew T. Guzman, and Beth A. Simmons. 2006. “Competing for Capital: The Diffusion of Bilateral Investment Treaties, 1960-2000.” International Organization 60 (4): 811–846. doi:10.1017/S0020818306060279.

- EU. 2015. “Investment in TTIP and beyond – The Path for Reform: Enhancing the Right to Regulate and Moving from Current Ad Hoc Arbitration Towards an Investment Court.” https://trade.ec.europa.eu/doclib/docs/2015/may/tradoc_153408.PDF

- Franck, Susan D. 2005. “The Legitimacy Crisis in Investment Treaty Arbitration: Privatizing Public International Law through Inconsistent Decisions.” Fordham Law Review 73 (4): 1521–1625.

- Guzman, Andrew T. 1998. “Why LDCs Sign Treaties that Hurt Them: Explaining the Popularity of Bilateral Investment Treaties.” Virginia Journal of International Law 38: 640–688.

- Haftel, Yoram Z., and Tomer Broude. 2022. “Fiddlers on the Roof? International Organizations in the International Investment Regime as Traditional Global Governance.” Working Paper, GLOBE – The European Union and the Future of Global Governance https://www.globe-project.eu/fiddlers-on-the-roof-international-organizations-in-the-international-investment-regime-as-traditional-global-governance_15291.pdf

- Haftel, Yoram Z., and Alexander Thompson. 2018. “When Do States Renegotiate Investment Agreements? the Impact of Arbitration.” Review of International Organizations 13 (1): 25–48. doi:10.1007/s11558-017-9276-1.

- Howse, Robert. 2017. “Designing a Multilateral Investment Court: Issues and Options.” European Yearbook of International Law 36: 209–236. doi:10.1093/yel/yex013.

- Kidane, Won. 2018. “Contemporary International Investment Law Trends and Africa’s Dilemmas in the Draft Pan-African Investment Code.” The George Washington International Law Review 50: 523–579.

- Langford, Malcom, Michele Potestà, Gabrielle Kaufmann-Kohler, and Daniel Behn. 2020. “: UNCITRAL and Investment Arbitration Reform: Matching Concerns and Solutions - an Introduction.” Journal of World Trade and Investment 21: 167–187. doi:10.1163/22119000-12340171.

- Meunier, Sophie. 2014. “Divide and Conquer? China and the Cacophony of Foreign Investment Rules in the EU.” Journal of European Public Policy 21 (7): 996–1016. doi:10.1080/13501763.2014.912145.

- Meunier, Sophie. 2017. “Integration by Stealth: How the European Union Gained Competence over Foreign Direct Investment.” JCMS: Journal of Common Market Studies 55 (3): 593–610.

- Meunier, Sophie, and Jean-Frédéric Morin. 2017. “The European Union and the space-time Continuum of Investment Agreements.” Journal of European Integration 39 (7): 891–907. doi:10.1080/07036337.2017.1371706.

- Poulsen, and Lauge N. Skovgaard. 2015. Bounded Rationality and Economic Diplomacy: The Politics of Investment Treaties in Developing Countries. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Poulsen, and Lauge N. Skovgaard. 2020. “Beyond Credible Commitments:(investment) Treaties as Focal Points.” International Studies Quarterly 64 (1): 26–34.

- Poulsen, Lauge N. Skovgaard, and Emma Aisbett. 2013. “When the Claim Hits: Bilateral Investment Treaties and Bounded Rational Learning.” World Politics 65 (2): 273–313. doi:10.1017/S0043887113000063.

- Reinisch, August. 2014. “The EU on the Investment Path -quo Vadis Europe? the Future of EU BITs and Other Investment Agreements.” Santa Clara Journal of International Law 12 (6): 111–157.

- Roberts, Anthea. 2018. “Incremental, Systemic, and Paradigmatic Reform of Investor-State Arbitration.” American Journal of International Law 112 (3): 410–432. doi:10.1017/ajil.2018.69.

- Roberts, Anthea, and St. John Taylor. 2022. “Complex Designers and Emergent Design: Reforming the Investment Treaty System.” American Journal of International Law 116 (1): 96–149. doi:10.1017/ajil.2021.57.

- Schill, Stephan W. 2007. “Do Investment Treaties Chill Unilateral State Regulation to Mitigate Climate Change?” Journal of International Arbitration 24 (5): 469–477. doi:10.54648/JOIA2007035.

- Swoboda, Ondřej. 2022. “UNCITRAL Working Group III and Multilateral Investment Court – Troubled Waters for EU Normative Power.” European Investment Law and Arbitration Review Online 6 (1): 104–126. doi:10.1163/24689017_0601005.

- Thompson, Alexander, Tomer Broude, and Yoram Z. Haftel. 2019. “Once Bitten, Twice Shy? Investment Disputes, State Sovereignty, and Change in Treaty Design.” International Organization 73 (4): 859–880. doi:10.1017/S0020818319000195.

- Titi, Catherine. 2015. “International Investment Law and the European Union: Towards a New Generation of International Investment Agreements.” European Journal of International Law 26 (3): 639–661. doi:10.1093/ejil/chv040.

- UNCITRAL. 2021. “Possible Reform of Investor-State Dispute Settlement (ISDS) Standing Multilateral Mechanism: Selection and Appointment of ISDS Tribunal Members and Related Matters, Note by the Secretariat.” https://uncitral.un.org/sites/uncitral.un.org/files/media-documents/uncitral/en/20211125_wp_selection_eums_comments.pdf

- UNCTAD. 2012. Investment Policy Framework for Sustainable Development. Geneva: United Nations.

- Waibel, Michael, Asha Kaushal, Kyo-Hwa Liz Chung, and Clair Balchin. 2010. The Backlash against Investment Arbitration: Perceptions and Reality. Wolters Kluwer:New York.

- Wellhausen, Rachel L. 2016. “Recent Trends in investor–state Dispute Settlement.” Journal of International Dispute Settlement 7 (1): 117–135. doi:10.1093/jnlids/idv038.

Appendix

Table A1: Coding state regulatory space in IIAs: Variables, dimensions and categories.

Table A2: Key events – EU IIA policies, 2007–2020.